The Governor’s budget solutions in higher education include unallocated General Fund reductions of $500 million for the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU). As we discuss in our recent publication,

The 2011–12 Budget: Higher Education Budget in Context, while these reductions are large, in our view they do not appear unreasonable given the size of the state’s budget problem, and considering that the current–year budget imposed no program reductions on the universities. Despite some new revenue from tuition increases, the universities would have to implement a range of service reductions affecting students, faculty, and staff to absorb these reductions. This brief provides our recommendations for mitigating the impact of the reductions on UC’s and CSU’s educational missions.

The universities received a double–digit General Fund augmentation in the current year, followed by the Governor’s even larger proposed reduction for 2011–12. The large current–year augmentation creates a “cliff effect”—amplifying the reduction needed to achieve the proposed 2011–12 funding level. We recommend shifting a portion of the proposed reduction to the current year. This would reduce the magnitude of funding changes in both years, while still achieving needed General Fund savings. This approach would have several benefits:

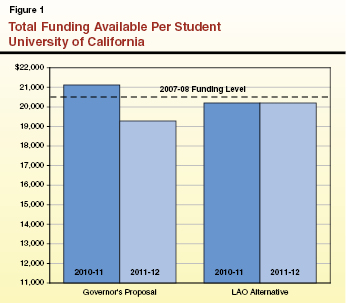

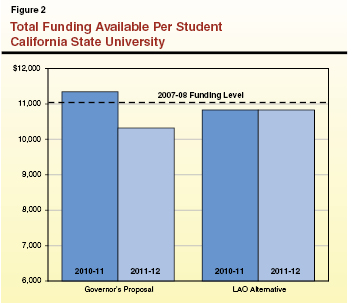

- Avoids Steep Drop in Funding. By spreading out the proposed reductions, this approach would avoid the Governor’s proposed steep drop in total funding from one year to the next. The Legislature could provide current–year funding that is substantially higher than in the prior year (albeit lower than in the enacted budget) and hold that level steady into the budget year, while achieving the same overall level of General Fund savings as that proposed by the Governor. This distribution of the reductions is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. (We adjust for changes in enrollment and tuition levels since the 2007–08 base year by showing total programmatic funding per student.)

- Buys Time to Adjust Base Budget. A stepwise reduction would preserve more funding for the segments in the budget year, and potentially in their ongoing base budgets. This would allow additional time for the state to seek alternative savings for the future, or for the segments to align their future costs with projected funding levels.

- Realigns Expectations. In practice, the campuses would have to begin implementing reductions in the current year in order to meet the $1 billion savings target. Formalizing reductions in the current year promotes early implementation of savings strategies, and helps prevent the illusion of plentiful funding in the current year that may delay necessary actions.

- Improves Transparency. Showing the reduction over two years would also provide a clearer picture of the resources available for each year, which is helpful to policy makers in analyzing trends and making future funding decisions.

Even if the budget is enacted by March 2011, no more than four months would remain in the fiscal year for the universities to achieve savings. It can be difficult to make necessary changes in such a short period of time, with the spring term well underway. However, there are reasons to expect the universities to have savings in the current year.

- Late Budget With Large Augmentations. The 2010–11 budget was not enacted until October 2010, several months into the academic year. The universities made the majority of their enrollment decisions for the current year before they knew they would receive large augmentations. In CSU’s case, campuses based fall admissions on an enrollment target nearly 30,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students lower than the funded enrollment level due to cautious budget expectations. The campuses will enroll additional students in the spring term but will be unlikely to meet their new enrollment targets. As a result, it will be difficult for them to spend all their budgeted resources.

- Prudent Caution Regarding 2010–11 Increases. Some university officials were skeptical about the state’s ability to fund the university augmentations proposed by the previous Governor in his May Revision. When the augmentations were included in the enacted budget, it was understood that these amounts might be reduced in a special legislative session or the next regular budget cycle. Under these circumstances, the segments needed to hold down spending in the event the augmentations were reduced. Informal discussions with some campus officials suggest the segments have exhibited such caution.

As noted above, the magnitude of funding reductions in 2011–12 would be smaller under LAO’s alternative distribution than the Governor’s proposed budget. However, total university support in the current year and the budget year would still be about $368 million less each year than the 2010–11 budget presumed. This is an annual reduction of about 4.5 percent in total programmatic funding. We recommend the Legislature provide some parameters regarding how the segments accommodate these reductions.

Continue to Implement Academic and Administrative Cost Reductions. In response to funding reductions in recent years, both segments have begun to implement a number of actions to reduce costs for instruction, student support, and administrative services. For example, administrative initiatives include bulk service, supply and energy procurement; joint information technology support; and restrictions on travel and other discretionary spending. Academic cost reductions have been achieved through increased class sizes, higher teaching loads, consolidated student support services, and academic program consolidation or elimination, as well as efforts to reduce students’ time to degree. In addition, cross–cutting personnel actions have included postponing merit increases; imposing employee furloughs and layoffs; reducing salaries for senior management; and increasing employee contributions to retirement plans and other employment benefits. We recommend the Legislature direct the segments to continue pursuing these types of reductions as they develop plans to accommodate budget cuts.

Recognize Lower Enrollment Level for CSU. Given the late passage of the 2010–11 budget, it is unlikely CSU will meet its budgetary enrollment target. The CSU campuses admitted students for the fall semester based on an enrollment target that was about 30,000 FTE students lower than the level ultimately funded in the 2010–11 budget. Recognizing the enrollment reductions that have already taken place for CSU and basing the 2011–12 targets on a realistic estimate of current–year enrollment would lessen the need to further “reduce” enrollment in the budget year.

In contrast, UC enrolled more students than budgeted in the current year. To better align enrollment with available resources, the university is likely to adjust its enrollment toward the budgeted level.

Do Not Rule Out Limited Tuition Increase. In

The 2011–12 Budget: Higher Education Budget in Context, we note that while resident undergraduate tuition at UC is at the median for its comparison group, tuition at CSU remains lowest among its comparison group of 16 state universities. The result is that, compared with other states, California is more broadly subsidizing all state university students, including those with the ability to pay more. Given substantial protections in place for financially–needy students—Cal Grants and campus financial aid cover full tuition for about half of UC and CSU students—we suggest the Legislature consider the possibility of some additional tuition increases.

Although the administration says that the unallocated reductions are “intended to minimize fee and enrollment impacts on students by targeting actions that lower the cost of instruction,” it is not clear how the administration plans to achieve this goal. Proposed budget bill language simply requires the segments to “develop an appropriate enrollment target” in consultation with the administration and the Legislature. We recommend the Legislature amend the budget package to specify how the segments accommodate General Fund reductions. For example, it could specify enrollment targets and maximum tuition levels, thus influencing the extent to which the segments balance enrollment and tuition changes with other strategies as discussed above. To ensure compliance, General Fund appropriations could be tied to the meeting of these expectations.

While immediate steps are necessary to accommodate reductions, funding constraints are projected to persist for the foreseeable future. As a result, we believe the state needs a longer–term strategy to make the higher education system more efficient and productive. (See nearby box about the growing consensus on the need for structural reform in higher education.) Many of the policy changes the Legislature may wish to make will require time to develop and fully implement. There are steps, however, the Legislature and the universities could take now to begin this process.

- Prioritize. In the context of state priorities for higher education, we recommend the Legislature reexamine the balance of functions it expects higher education to focus on—including research, graduate education, and undergraduate education.

- Direct Universities to Prioritize. Likewise, the universities should identify priorities within their programs and services. We recommend the Legislature direct the universities to streamline offerings by eliminating, merging, or markedly improving the cost–effectiveness of low–enrollment, high–cost, underperforming, or unnecessarily duplicative programs.

- Transform Delivery of Instruction. Despite the integration of some online learning and other technologies, most instruction is still delivered largely the same way it has been delivered for decades, and in some cases centuries. The standard lecture course format with an instructor presenting content to students is often expensive, outdated, and fails to take advantage of improved understanding of how students learn and related advances in instructional design and technology. We recommend the Legislature develop incentives for campuses to adopt updated instructional methods that have been shown to improve outcomes and reduce costs.

- Measure What Matters. As the state considers goals and priorities for higher education, it will need to identify desired outcomes for both instructional and support programs. For example, several states have identified key outcomes such as program completion, licensure and certification, job placement rates for students, and value–added student learning outcomes. We recommend the state establish goals and desired outcomes for higher education, set corresponding outcome targets, and measure the outcomes and associated costs for each university system.

- Reconsider Roles. The Master Plan’s clear differentiation of the eligibility pools, missions, and functions for each of the public higher education segments has become blurred over time. For example, changes in UC’s eligibility criteria have increased the overlap in eligibility pools for UC and CSU. Increasing selectivity at some CSU campuses has weakened the local admission guarantee for CSU–eligible students. The Legislature has authorized CSU to offer three professional doctoral degrees, as exceptions to the Master Plan’s assigned functions which gave UC sole authority to award the doctoral degree. In light of the state’s resource constraints, we recommend the Legislature reconsider the roles of each segment, and campuses within the segments, with an eye toward the overall efficiency of the state’s higher education system.

|

There has been growing nationwide consensus that public colleges and universities must find ways to markedly improve student outcomes—such as degree and credential attainment—within available resources. States have begun to make fundamental changes in their higher education systems to this end. For example, Washington, Ohio, and Indiana have recently implemented new funding strategies tied to student outcomes, and several other states are close behind them. Indiana has partnered with a low–cost online university to boost educational attainment for adults in the state. Several other states are developing ways to take advantage of capacity in private colleges and universities. Tennessee has revised its approach to remedial education. Maryland and Ohio have implemented comprehensive efficiency programs for their higher education systems.

In California, this notion of a systematic review of programs characterized the work of UC’s Commission on the Future, the Community College League of California’s similarly named commission, and the recent legislative Joint Committee to Review the Master Plan. In addition, both UC and CSU have launched systemwide initiatives to improve efficiency, degree completion, and other positive outcomes. With the notable exception of recent transfer legislation (Chapter 428, Statutes of 2010 [SB 1440, Padilla]), however, there has been little statewide policy action to improve the productivity of public higher education as a system. |

Profound changes will be required to align higher education outcomes and costs with the state’s needs and realities. Although many of these reforms involve longer–term transformation, each could be started by legislative or institutional policy actions in the current year.

This brief provides our preliminary recommendations for responding to the proposed reductions in UC’s and CSU’s General Fund budgets. In the coming weeks, we will provide additional guidance on these proposals and other features of the Governor’s budget.

Contact Information

Steve Boilard,

Director, Higher Education, 319–8331

Paul Steenhausen,

California Community Colleges, 319–8324

Judith Heiman,

California State University, Financial Aid, 319–8358