In 2011, the state enacted several bills to "realign" to county governments the responsibility for certain low–level offenders, parolees, and parole violators. These changes will result in significant reductions in the inmate and parole populations managed by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). These reductions will have various implications for how CDCR manages its prison and parole system.

Three–Judge Panel. The 2011 realignment was undertaken, in part, to comply with a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in the state's 33 prisons to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity by June 2013. Based on CDCR's current population projections, it appears that it will eventually reach the court–imposed population limit, though not by the June 2013 deadline. Thus, we recommend that the state request more time from the court. If additional reductions to the state prison population are needed, the Legislature has several options it could consider, including expanded use of contracted beds and various alternatives to prison.

Inmate Housing. As a result of realignment, CDCR is projected to have a shortfall in high–security housing and a surplus in its other housing types. To address this, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to maximize the use of its existing facilities to house high–security inmates—for example, by converting reception centers to high–security facilities. We also recommend that the department identify various options to address any continuing shortfall in high–security housing that would remain. Based on these revised plans, the Legislature may want to significantly reduce the size of the Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900, Solorio) prison construction bond and could consider closing some existing prisons.

Fire Camps. Because realignment will reduce the population of low–level offenders, it will likely result in a significant decline in the number of inmates eligible to work in fire camps. This is problematic because failing to house offenders in these camps hurts the state's ability to comply with the above federal court order, increases prison costs, and increases the state's cost to fight fires. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to review the eligibility criteria for fire camps and look for other options to increase the number of state inmates in the program.

Inmate Medical Care. Realignment will make it easier to deliver adequate care to inmates requiring chronic outpatient medical care and alter the need for health care facility upgrades at existing prisons. As such, we recommend the Legislature approve the Governor's plan to cancel the additional outpatient housing facilities proposed at Dewitt and Estrella and review any future proposals for health facility upgrades to ensure that they account for the impacts of realignment. We find that the construction of a new prison hospital in Stockton will meet most of the department's ongoing need for inpatient hospital beds. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature not approve the construction of any additional inpatient hospital beds at this time.

Inmate Mental Health Care. Realignment will significantly reduce the number of mentally ill inmates in the state's prisons. As a result, we are projecting that the department may have excess treatment and housing space for certain types of mentally ill inmates that it could repurpose for other uses (such as providing treatment to other types of mentally ill inmates for whom there is a shortage of capacity). We recommend the Legislature direct CDCR to report at budget hearings regarding its mental health facility plans, including how it plans to utilize the projected surplus of capacity following the full implementation of realignment.

CDCR Rehabilitation Programs. The department is not currently delivering rehabilitation programs for inmates and parolees as effectively as possible, and there appears to be a substantial mismatch between the types of programs offered by CDCR and the needs of inmates and parolees. Realignment will likely change the mix of programs needed by the remaining population of inmates and parolees. We recommend that the Legislature not approve the Governor's proposed restoration of the current–year, one–time reduction of $101 million to rehabilitation programs until the department has presented a plan for how it will modify its programs to account for the impacts of realignment and conform to principles of effective programming.

In 2011, the state enacted several bills to realign to county governments the responsibility for managing and supervising certain felon offenders who previously had been eligible for state prison and parole. Over the next few years, these changes will result in significant reductions in the inmate and parole populations managed by CDCR. The purpose of this report, which is the second of a two–part series examining the impacts of the 2011 realignment on California's criminal justice system, is to identify the impacts of the realignment of adult offenders on CDCR's operations and facility needs.

Specifically, this report discusses whether realignment will enable the state to meet the prison population limit required by the federal court, and how the state should proceed if it appears that these limits will be missed in the time line specified by the court. In addition, the report discusses how the change in the makeup of CDCR's inmate population following realignment will affect its housing, mental health, and medical facility needs, and provides recommendations on how to better match CDCR facilities with the remaining inmate population. We also discuss how realignment will impact the state's fire camp program and how the state can ensure that this program continues to yield its full benefit following realignment. Finally, we describe how realignment will affect the need for rehabilitation programs and how to better match these programs to the needs of the remaining inmates and parolees.

Several times over the last 20 years, the state has sought significant policy improvements by reviewing state and local government programs and realigning responsibilities to a level of government more likely to achieve good outcomes. As part of the 2011–12 budget package, the state enacted such a reform by realigning to counties responsibility for adult offenders and parolees, court security, various public safety grants, mental health services, substance abuse treatment, child welfare programs, adult protective services, and California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids. To finance the new responsibilities shifted to local governments, the 2011 realignment plan reallocated state sales tax and state and local vehicle license fee revenues to counties. (Please see our recent report,

The 2012–13 Budget: The 2011 Realignment of Adult Offenders—An Update, for a more detailed description of the overall 2011 realignment plan.)

The most significant policy change created by the 2011 realignment is the shift of responsibility for adult offenders and parolees from the state to the counties. As we discuss later in this report, this realignment was adopted in part due to a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in California's prison system. The shift in responsibilities can be divided into three distinct parts: the shift of lower–level offenders, the shift of parolees, and the shift of parole violators. We discuss each in detail below.

- Lower–Level Offenders. The 2011 realignment limited which felons can be sent to state prison, thereby requiring that more felons be managed by counties. Specifically, sentences to state prison are now limited to registered sex offenders, individuals with a current or prior serious or violent offense, and individuals that commit certain other specified offenses. Thus, counties are now responsible for housing and supervising all felons that do not meet that criteria. The shift was done on a prospective basis effective October 1, 2011, meaning that no inmates under state jurisdiction prior to that date were transferred to the counties. Only lower–level offenders convicted after that date came under county jurisdiction.

- Parolees. Before realignment, individuals released from state prison were supervised in the community by state parole agents. Following realignment, however, state parole agents only supervise individuals released from prison whose current offense is serious or violent, as well as certain other individuals including those who have been assessed to be Mentally Disordered Offenders or High Risk Sex Offenders. The remaining individuals—those whose current offense is nonserious and nonviolent, and who otherwise are not required to be on state parole—are released from prison to community supervision under county jurisdiction. This shift was also done on a prospective basis, so that only individuals released from state prison after October 1, 2011 became a county responsibility. County supervision of offenders released from state prison is referred to as Post–Release Community Supervision and will generally be conducted by county probation departments.

- Parole Violators. Prior to realignment, individuals released from prison could be returned to state prison for violating a term of their supervision. Following realignment, however, those offenders released from prison—whether supervised by the state or counties—must generally serve their revocation term in county jail. (The exception to this requirement is that individuals released from prison after serving an indeterminate life sentence may still be returned to prison for a parole violation.) In addition, individuals realigned to county supervision will not appear before the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) for revocation hearings, and will instead have these proceedings in a trial court. Before July 1, 2013, individuals supervised by state parole agents will continue to appear before BPH for revocation hearings. After that date, however, the trial courts will also assume responsibility for conducting revocation hearings for state parolees. These changes were also made effective on a prospective basis, effective October 1, 2011.

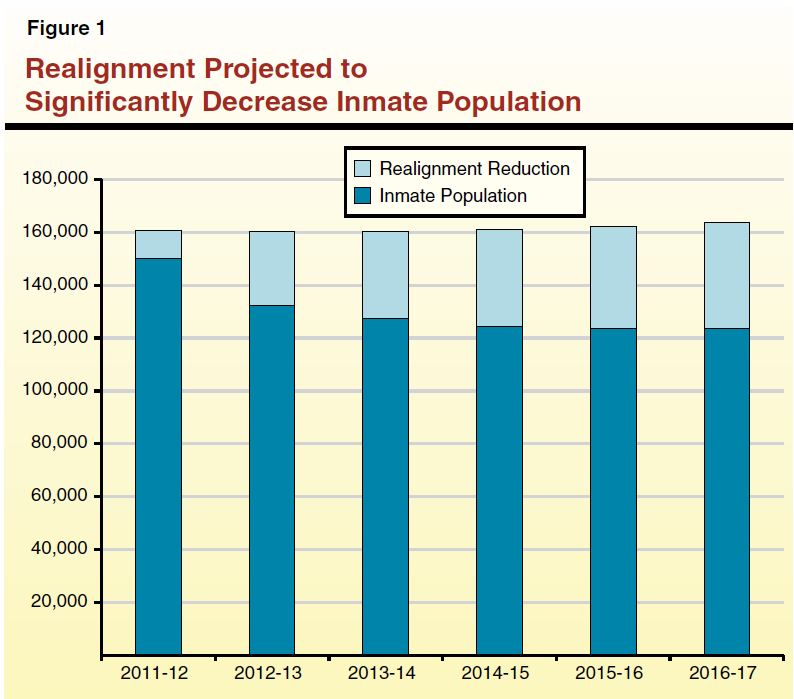

40,000 Fewer Inmates by 2017. As shown in Figure 1, CDCR projects that the average daily prison population will be nearly 11,000 inmates, or 7 percent, lower in 2011–12 than it would have been in the absence of realignment. By 2016–17, the department estimates that the prison population will be lower by nearly 40,000 inmates, or 24 percent, than it otherwise would have been absent the 2011 realignment. By the end of this projection period, the state's prison system is expected to have about 124,000 inmates. These estimates are consistent with the administration's original projections regarding the impact of the 2011 realignment on the state prison population.

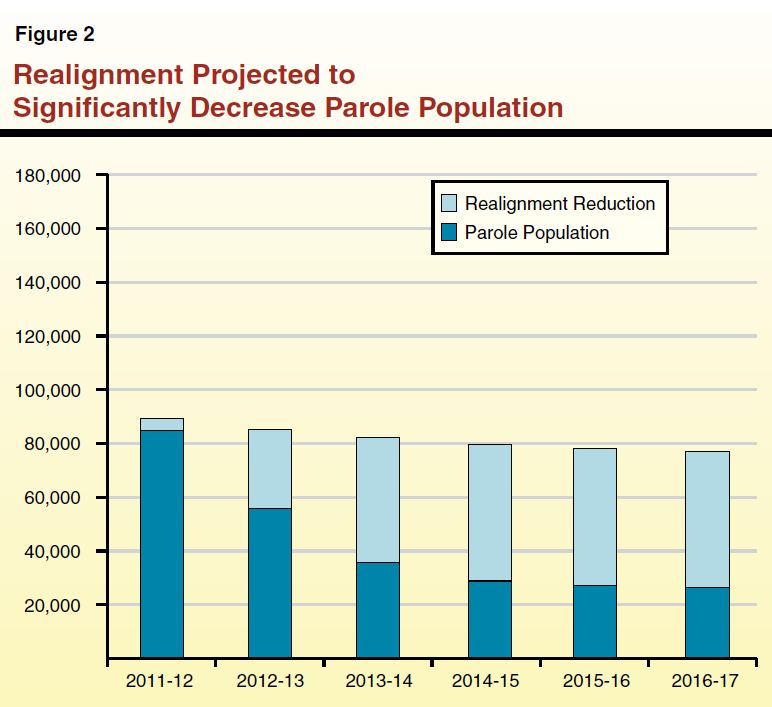

51,000 Fewer Parolees by 2017. The 2011 realignment is projected to result in an even greater reduction in the number of parolees supervised by the state. As shown in Figure 2, CDCR projects that the average daily parole population will be nearly 4,300 parolees, or 5 percent lower, in 2011–12 than it would have been in the absence of realignment. By 2016–17, the department estimates that the parole population will be nearly 51,000 parolees, or 66 percent lower, than it otherwise would have been absent the 2011 realignment. By the end of this projection period, the state parole system is expected to have about 26,000 parolees.

At the time the 2011 realignment was enacted, the administration estimated that the above decline in the inmate and parole populations would reduce spending on CDCR operations by $453 million in 2011–12 and by about $1.5 billion in 2014–15. Based on updated information from the Department of Finance (DOF), the administration now projects that the 2011 realignment will save significantly more than initially estimated. Specifically, DOF estimates that the total reduction in spending on CDCR will reach about $1.7 billion in 2014–15—$200 million, about 14 percent, higher than the original estimate. The higher–than–expected savings are attributable to a much larger planned reduction in costs for CDCR's adult institutions and administrative functions. Most of the savings created by realignment are related to reductions in prison spending (about 65 percent), with lesser amounts attributable to parole reductions (about 20 percent), and administrative savings (about 15 percent).

As previously mentioned, the realignment of certain lower–level offenders and parole violators was partly intended to help comply with a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in California prisons. Below, we discuss the court's order and whether the state is on track to meet it in the time line specified.

Federal Three–Judge Panel Ordered State to Reduce Prison Overcrowding. In November 2006, plaintiffs in two ongoing class action lawsuits—Plata v. Brown (involving inmate medical care) and Coleman v. Brown (involving inmate mental health care)—filed motions for the courts to convene a three–judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act. The plaintiffs argued that persistent overcrowding in the state's prison system was preventing CDCR from delivering constitutionally adequate health care to inmates. In August 2009, the three–judge panel declared that overcrowding in the state's prison system was the primary reason that CDCR was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care. Specifically, the court ruled that in order for CDCR to provide such care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity in the state's 33 prisons within two years. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell in its 33 prisons, and did not use temporary beds, such as housing inmates in gyms. Inmates housed in contract facilities or fire camps are not counted toward the overcrowding limit.) The court required the state to reduce overcrowding to specific design capacity limits at six–month intervals leading up to the two–year deadline.

Three–Judge Panel Decision Upheld by Supreme Court. Following an appeal of the decision by the state, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the three–judge panel's ruling, declaring that "without a reduction in overcrowding, there will be no efficacious remedy for the unconstitutional care of the sick and mentally ill" inmates in California's prisons. Figure 3 shows, for each six–month interval, the design capacity limit ordered by the federal courts, the corresponding number of inmates that the state could house in its prisons, and the incremental inmate population reductions necessary to meet the court's population limit.

Figure 3

Estimated Inmate Population Reductions To Meet Federal Court Ruling

|

Court–Imposed Deadline

|

Design

Capacity Limit

|

Population

Limit

|

Population

Reductiona

|

|

December 27, 2011

|

167.0%

|

133,000

|

11,000

|

|

June 27, 2012

|

155.0

|

123,000

|

10,000

|

|

December 27, 2012

|

147.0

|

117,000

|

6,000

|

|

June 27, 2013

|

137.5

|

110,000

|

7,000

|

|

Two–Year Total

|

|

|

34,000

|

While the state has undergone various changes to reduce overcrowding prior to the passage of the realignment legislation—including transferring inmates to out–of–state contract facilities, construction of new facilities, and various statutory changes to reduce the prison population—the realignment of adult offenders is the most significant change undertaken to reduce overcrowding.

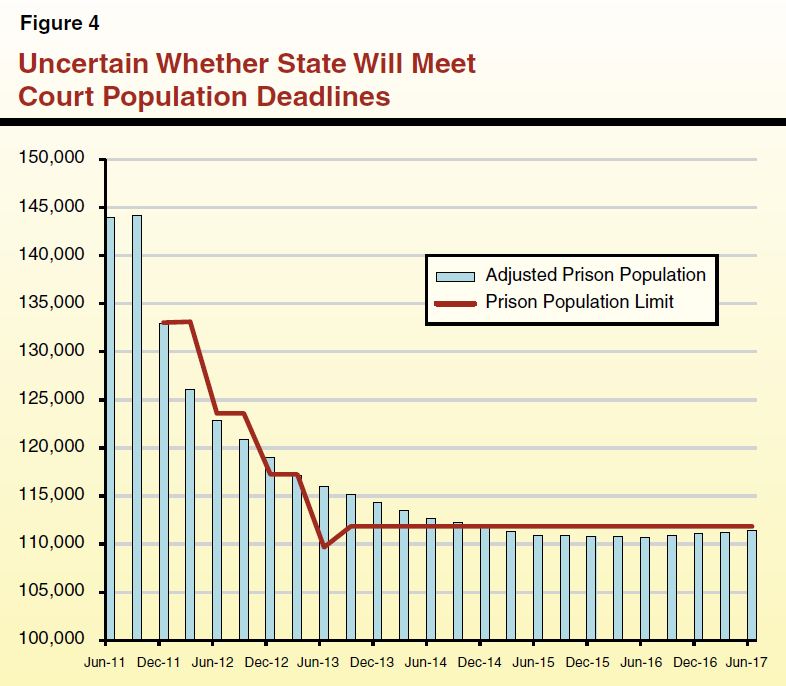

Current Projections Show Population Reductions Met in Out Years . . . Based on CDCR's current population projections, it appears that the state may not meet the future population limits set by the federal court. In particular, the projections show the state missing the final population limit of no more than 110,000 inmates housed in state prisons by June 2013. Specifically, the projections show the state exceeding this limit by about 6,000 inmates. However, the projections indicate that the state will meet the court–imposed limit by the end of 2014. Figure 4 compares the projected inmate population and the three–judge panel population limits. (We note that the increase in the population limit in September 2013 reflects the completion of the California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton, which will provide the state with additional housing capacity.)

. . . But Other Factors Could Change Actual Outcome in Either Direction. While the department's current projections indicate that the state would miss the court's upcoming deadlines, there is uncertainty as to whether the state will, in fact, miss those deadlines as they approach. This is because CDCR's population projections could be either higher or lower than what actually materializes. For example, over the past several months, the inmate population has actually been lower than what the department projected in the fall 2011. Moreover, the accuracy of the department's projections historically are reduced the further into the projection period one looks. In the current situation—post–realignment—where a major change in policy has just been enacted, it is exceedingly difficult for the department to forecast how the prison population will be affected a few years from now. Again, CDCR's longer–term projections could be either high or low depending on a variety of future factors, such as how successful counties are in managing their existing and realigned offender populations and whether there are any significant changes in judicial and prosecutorial practices that affect the number of offenders sentenced to state prison.

Direct Administration to Request More Time to Comply. Given the uncertainty about whether, and in what timeframe, CDCR will be able to meet the federal court's population limits, we recommend that the Legislature closely monitor the department's progress over the coming year. However, if the department's updated population projections—which will be provided as part of the Governor's May Revision—continue to project that the state will miss the population limits in the short run, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to request that the three–judge panel modify its compliance deadlines in order to provide the state with additional time to meet the required population limits. The U.S. Supreme Court suggested in its recent court ruling that such a request for more time to the federal three–judge panel would be reasonable. Moreover, given that the recently enacted policy changes are projected to bring the state into compliance on an ongoing basis, we believe the state has a strong case to make to the court for additional time. Making the request sooner rather than later is also important, as it will give the state ample time to plan how it will comply with the deadline if the federal court rejects the request.

Consider Other Options if Additional Reductions Are Needed. Absent an extension, the Legislature may have to consider additional policy changes that would further reduce the inmate population. While there are some options that the Legislature could choose from, these options are much more limited than in past years because so many of the lowest–level offenders have been realigned to the counties. Some of the available population reduction strategies include expanding the use of contract facilities and fire camps, expanding alternative custody or work furlough programs, increasing the amount of credits inmates earn, and changing sentencing laws.

Inmate Classification and Housing. In general, inmates are initially housed in reception centers (usually in cells) upon their admission to CDCR. After which, the department assigns inmates to different types of housing based on several factors including offense, length of prison sentence, and behavior during current and prior incarcerations. Inmates considered low security (classified as Levels I and II) are generally housed in dorms, while high–security inmates (classified as Levels III and IV) are generally housed in cells. Female inmates—regardless of classification—are often placed in the same housing units. (Currently, the state operates only three female facilities.) However, as we discuss below, overcrowding in the state's prisons have made it difficult to effectively meet the particular housing needs of certain inmates.

Current Plan to Construct Additional Prison Beds. In 2007, the Legislature passed AB 900, in order to relieve the significant prison overcrowding problem. Specifically, AB 900 authorized a total of $7.7 billion—$7.4 billion in lease–revenue bonds and $300 million in General Fund support—for a broad package of state prison and local jail construction and rehabilitation initiatives, as follows:

- $2.4 billion to construct infill beds intended to replace so–called "temporary" housing in gymnasiums, day rooms, and other public spaces in prisons. (Infill beds are housing units constructed on the grounds of existing facilities.) Assembly Bill 900 did not specify the mix of high– and low–security infill beds to be constructed.

- $2.6 billion to construct "reentry facilities" primarily for inmates within one year of being released from custody.

- $1.1 billion to construct inmate health care facilities.

- $1.2 billion to help counties construct local jail facilities.

- $300 million to make various infrastructure improvements at existing prisons.

At this time, over $5 billion authorized in AB 900 has not been spent. However, CDCR has developed an AB 900 Integrated Strategy Plan that lists the projects it plans to complete in the next few years with these funds, as well as the number and type of housing beds (such as lower security or higher security) that will be built. In addition to the funds authorized in AB 900, the Legislature has also provided CDCR with $135 million for other prison construction and renovation projects. At this time, however, the department has not provided a revised statewide prison construction plan for both of the above funding sources that reflects the recent realignment of lower–level offenders to counties. The administration indicates that it is currently in the process of reevaluating its plans.

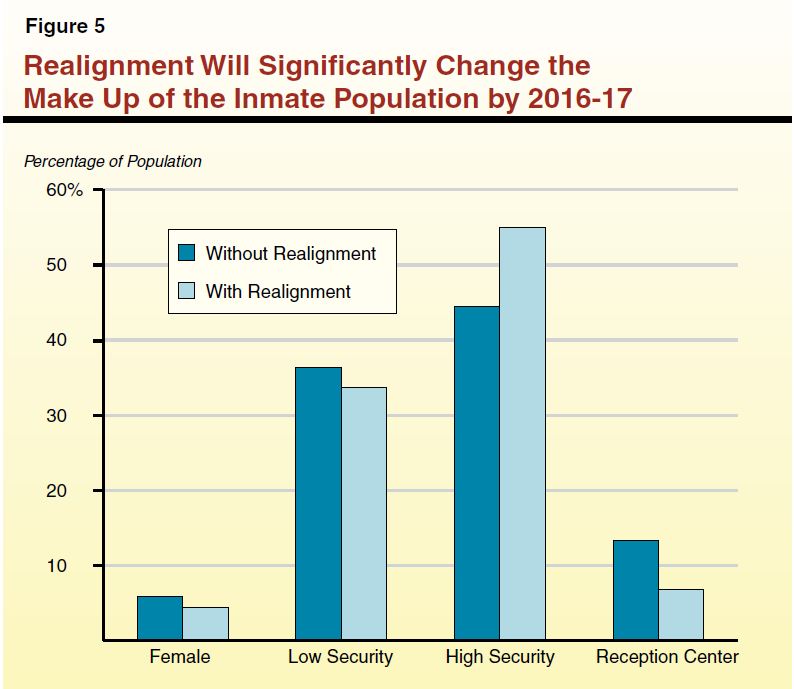

Realignment will disproportionately reduce the number of inmates in certain housing classifications. Specifically, realignment will significantly reduce the number of inmates in low security, female, and reception center facilities. While the number of high–security inmates will also decrease under realignment, they will make up a smaller share of the total reduction in the inmate population because of their more serious criminal histories. Consequently, high–security inmates will make up a much larger share of the inmate population that will remain in CDCR following the full implementation of realignment, as shown in Figure 5.

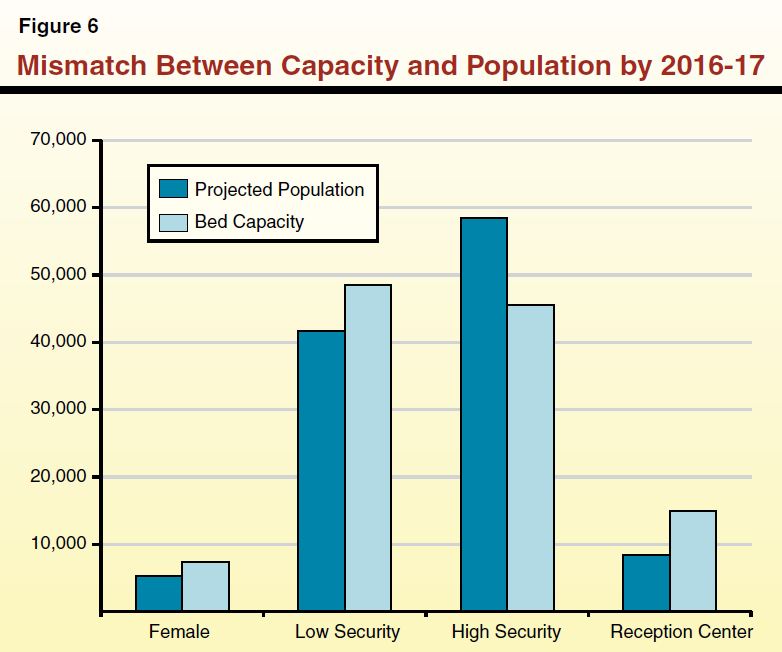

Long–Term Mismatch Between Population and Bed Capacity. Because the realignment is projected to significantly affect the make–up of the inmate population, it is important to examine whether the current prison capacity will provide the right mix of prison beds for the types of inmates that will be in prison after realignment is fully implemented. Our analysis indicates that there will likely be a mismatch between bed capacity and actual bed needs in the long run, absent any changes to CDCR's current infrastructure plan. Such a mismatch can be problematic for several reasons. For example, if left unaddressed, the state could continue to have significant overcrowding in high–security prisons, making them less safe and more difficult to operate. In addition, operating low–security and reception center facilities with large amounts of unused space would unnecessarily increase state costs.

As shown in Figure 6, CDCR's current estimates of the long–term inmate population indicate that, by 2016–17, the state will have excess low–security and reception center beds and insufficient high–security beds. (Our calculations assume that CDCR houses inmates at 137.5 percent of design capacity in existing prisons, full capacity in the state's fire camps, continued use of contracted facilities, and completion of capital outlay projects already underway.) Specifically, there will be excess capacity of 6,400 beds in reception centers, 6,800 beds in low–security prisons, and about 2,100 excess female prison beds. Conversely, we estimate that there will be a shortage of 12,900 high–security beds. On net, we estimate that, upon full implementation of realignment, the state will have excess capacity capable of housing about 2,400 inmates spread across the different types of housing used by CDCR.

Governor Proposes Some Changes to Prison Construction Plan. In light of the significant reduction in the inmate population resulting from realignment, the administration has expressed its intent to modify certain aspects of CDCR's current infrastructure plan. The administration indicates that CDCR is in the process of revising its plan, including its plans for AB 900 projects. At this time, it is unclear when a revised plan will be available for legislative review. Specifically, the Governor plans to:

- Convert Reception Centers. The administration intends to convert an unspecified number of reception center beds into beds for other classifications of inmates.

- Convert Valley State Prison. The administration plans to convert Valley State Prison for Women in Chowchilla—a female facility with a design capacity for about 2,700 inmates—into a low–security male facility by July 2013.

- Cancel Certain AB 900 Projects. The administration is also planning to cancel three specific projects planned under AB 900. The administration will not be requesting funds for the DeWitt Nelson infill project and the Northern California Reentry Facility project. In addition, as part of the proposed 2012–13 budget, the administration is proposing to remove funding previously approved for the activation of the Estrella infill project.

- Reconsider Infrastructure Projects. The administration has stated its intent to reconsider various infrastructure projects currently planned at sites around the state, including infrastructure improvements scheduled to be funded with $125 million of the remaining balance of the $300 million General Fund appropriation contained in AB 900.

In addition, the Governor is proposing budget trailer legislation to expand the Alternative Custody for Women program, which was established by Chapter 644, Statutes of 2010 (SB 1266, Liu). This program currently allows female offenders who meet several qualifications—including having no prior or current convictions for serious or violent offenses—to serve their sentence in the community. The Governor is proposing to expand the program to include women who have had current or prior serious or violent convictions, in order to allow CDCR to place these offenders in the community, further decreasing the need for female facilities.

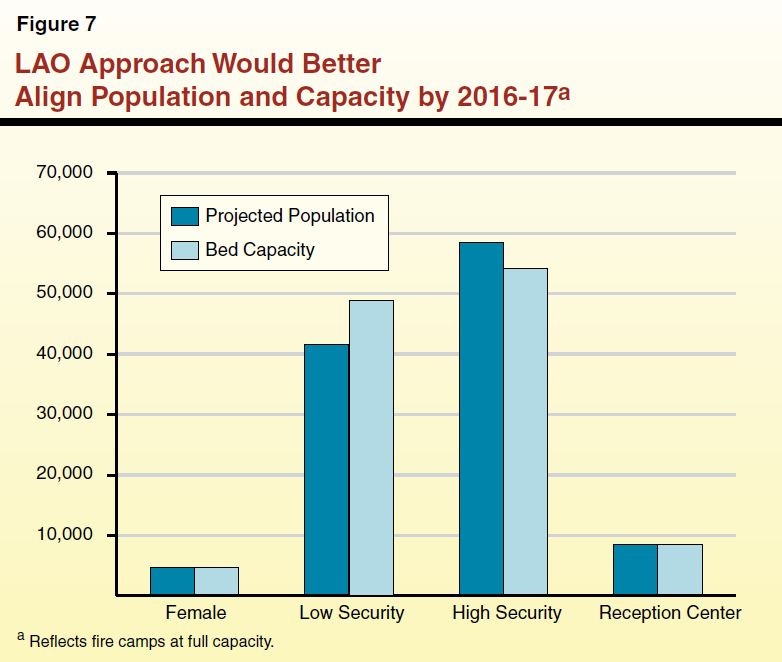

We find that most of the Governor's proposals discussed above would help CDCR better match its long–term capacity with its projected inmate population. For example, the Governor's proposal to convert reception center beds to higher–security beds would reduce the projected oversupply of reception center beds and undersupply of high–security beds. Despite the proposed changes, however, we estimate there will still be a significant mismatch of beds and inmates. Most significantly, we still estimate a shortfall of at least 6,500 high–security beds.

Thus, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to (1) maximize the use of existing facilities for high–security inmates, (2) revise its long–term plans to address remaining shortfalls as needed, (3) reconsider the size of AB 900, and (4) identify facilities for possible closures. We discuss each of these recommendations in more detail below.

Maximize Use of Existing Facilities for High–Security Inmates. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to make maximum use of its existing capacity, particularly for high–security inmates where possible. This would help reduce the amount of high–security capacity that may need to be built in the future, as well as help the state comply with the federal court order to reduce prison overcrowding. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature:

- Ensure Reception Center Beds Are Converted to High–Security Beds. We concur with the Governor's plan to convert surplus reception center beds to beds for high–security inmates. As mentioned above, reception centers generally have celled housing that is largely similar to high–security housing units. Thus, the proposed conversions would likely be inexpensive compared to building new facilities and take a relatively short amount of time to complete. We estimate that approximately 6,400 reception center beds could be converted to high–security facilities, offsetting the projected shortfall in high–security beds by about half.

- Direct CDCR to Review Existing Low–Security Facilities. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to include in its long–term facility plans an assessment of the extent to which certain low–security facilities can be used to house high–security inmates. We note that this is already occurring to some extent due to the current shortage of high–security beds. For example, both Folsom State Prison and the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, which are best suited for low–security inmates, have been successfully used in recent years to house high–security inmates.

- House Some High–Security Males at a Converted Valley State Prison. Given the projected reduction in the female inmate population, we find that the Governor's plan to convert Valley State Prison to a men's facility has merit. However, rather than covert it to a low–security facility, as proposed by the Governor, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to house as many high–security inmates as possible at the prison. We note that Valley State Prison currently includes cells capable of housing about 260 high–security inmates.

- Approve Alternative Incarceration for Women Expansion. We also recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor's proposal to expand the Alternative Custody for Women program, as this could help address a small shortfall in female beds that is projected to occur as a result of converting Valley State Prison for Women to a male facility. This would also help the state comply with the federal court order to reduce prison overcrowding.

- Direct CDCR to Report on Classification Study. We have been informed that CDCR recently completed a review of its security classification procedures to determine whether they need to be modified. Possible changes in the classification criteria could significantly affect CDCR's overall need for various types of facilities. At the time of this report, CDCR's classification study was not publicly available. Thus, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report on whether the results of the security classification study warrant modifications in its classifications procedures and on the extent to which such modifications could impact the long–term need for high–security capacity.

Figure 7 depicts our estimate of how the state's facility needs would change if the approaches outlined earlier were adopted, as well as our recommendations later in this report related to maximizing the use of fire camps. Based on these assumptions, we project that the current shortfall in high–security beds would be reduced by about two–thirds—leaving the need for 4,200 high–security beds. We also estimate that female and reception center bed capacity would roughly match the projected populations for those beds. However, we estimate that there would be a surplus of about 7,300 low–security beds. In total, the state would have a net surplus of about 3,100 beds.

Revise Plans to Address Additional Shortfalls as Needed. As mentioned previously, there is some uncertainty with respect to CDCR's long–term population projections. As such, we believe it is important that CDCR carefully monitor its population changes and reassess its long–term facility plan frequently in the coming years. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to annually update its long–term facility plan. We further recommend that the Legislature withhold funding for future capital outlay requests unless an updated facility plan demonstrates that the project is consistent with CDCR's latest population projections.

In addition, the department should identify specific proposals to address any remaining shortfall in high–security housing identified in its revised plans. For example, the department could address a shortfall by (1) expanding the use of contract facilities, (2) making any downward adjustments in inmate security classifications warranted by the classification study, and (3) allowing individual high–security facilities to remain slightly overcrowded. (The federal court ordered population limit applies to the prison system as a whole, and not to each individual prison.)

Reconsider Size of AB 900. While some of the remaining AB 900 funds may be necessary to convert existing facilities to high–security housing, this will only account for a fraction of the remaining $3.1 billion in AB 900 funds earmarked for infill and reentry beds. Based on the department's revised infrastructure plan, the Legislature may want to reduce the size of the AB 900 bond, potentially by billions of dollars. This would save the state substantial debt service payments over the long term. For example, if only $1 billion of the remaining funds are found to be necessary for reconfiguring existing facilities, the state could save more than $200 million in annual debt service payments.

Identify Facilities for Possible Closure. Given that the state is projected to have thousands of excess low–security beds, the state may be in a position to close one or more prisons in future years. Closing a prison could result in tens of millions of dollars of savings annually for the state. In addition, prison closures could result in positive fiscal benefits to the state from avoiding facility maintenance costs, as well as generating one–time revenue from the sale of closed facilities. As such, the Legislature should direct CDCR to include in its capital outlay plans a review of possible prison facilities that could be closed in the near future. In determining which facilities to close, we believe that consideration should be given to the following criteria.

- Security Level of Existing Inmate Population. Facilities that are largely or exclusively being used to house low–security inmates are good candidates for closure, given the projected oversupply of these beds systemwide. However, there may be particular reasons why a low–security facility should remain open, such as whether it could be used to house higher–security inmates and whether it currently operates to meet a critical need (such as a health care facility or fire camp).

- Cost to Operate. For various reasons, including the prison's design (which can drive staffing needs), certain prisons are more expensive to operate than others. For example, the California Institution for Men (CIM) in Chino houses inmates similar to those housed at the Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) in Tracy. Despite this similarity, CIM had an average per inmate cost of $55,000 per year in 2010–11, while DVI had an average per inmate cost of $44,000. In order to maximize state savings, priority for closure could be given to the state's more expensive prisons.

- Older Prisons. Many CDCR prisons are more than 30–years old. While still operational, many of these prisons require much greater levels of maintenance, and some will require significant renovations. Long–term maintenance and renovation costs should be taken into consideration when identifying possible prisons to close.

- High Vacancy Rate. For various reasons, certain facilities have difficulty recruiting and retaining staff. This can result in greater overtime costs and make it difficult for the facility to provide the same level of service as facilities with lower vacancy rates. Facilities with high vacancy rates therefore may make better candidates for closure.

- Revenue From Sale. In identifying facilities for closure, CDCR should also consider whether the facility could be sold and the amount of one–time revenue such a sale would generate for the state. For example, it has been suggested that the sale of San Quentin could generate a significant amount of one–time revenue for the state.

We note that, even though a facility may meet several of these criteria, further analysis may demonstrate that it is not a good candidate for closure. For example, a prison may have a specialized mission (such as the delivery of inmate health care services or substance abuse treatment) that may be difficult to fulfill at another prison. Moreover, CDCR may identify other key criteria that merit consideration.

The CDCR currently operates 42 adult fire camps, which can accommodate about 4,500 low–level inmates. Inmates assigned to fire camps carry out fire suppression work and respond to other emergencies, such as floods and earthquakes. In addition, fire crews work on conservation projects on public lands and provide labor on local community services projects. In order to be eligible for a fire camp, inmates must meet a series of requirements. For example, inmates that have committed certain crimes (such as arson) are ineligible. In addition, inmates must be eligible for low–security housing. These screening criteria make many inmates ineligible for fire camps. Figure 8 summarizes the screening criteria.

Figure 8

Fire Camp Screening Criteria

|

Criteria

|

Description

|

|

Offense history

|

Inmates with current or prior convictions for certain offenses (including murder, rape, and arson) are automatically ineligible. Certain other offenses, such as involuntary manslaughter, require case–by–case review.

|

|

Security classification

|

Inmates with security levels III and IV are excluded. (Inmates must be eligible for minimum custody.)

|

|

Time to serve

|

Inmates must have at least 60 days (if they have prior camp experience) and no more than 15 years left to serve.

|

|

Disciplinary history

|

Inmates must not have a pattern of excessive misconduct or have disrupted the orderly operations of their institution. Inmates with prior disciplinary problems may be eligible for a case–by–case review if they have remained disciplinary free for a sufficient length of time.

|

|

Gang affiliation

|

Inmates must have no validated active or inactive prison gang membership or association.

|

|

Health profile

|

Inmates must be specifically cleared by medical for camp placement. Inmates with medical, psychiatric, or dental concerns may be excluded.

|

|

Public interest cases

|

Inmates that are determined to be public interest cases that require exceptional placements due to their notoriety are excluded.

|

Inmates that participate in fire camps receive additional benefits compared to other prison inmates. Fire camp inmates get more "good time" credits towards their release date. In addition, fire camp inmates earn higher pay than inmates working other prison jobs, such as in the kitchen or laundry.

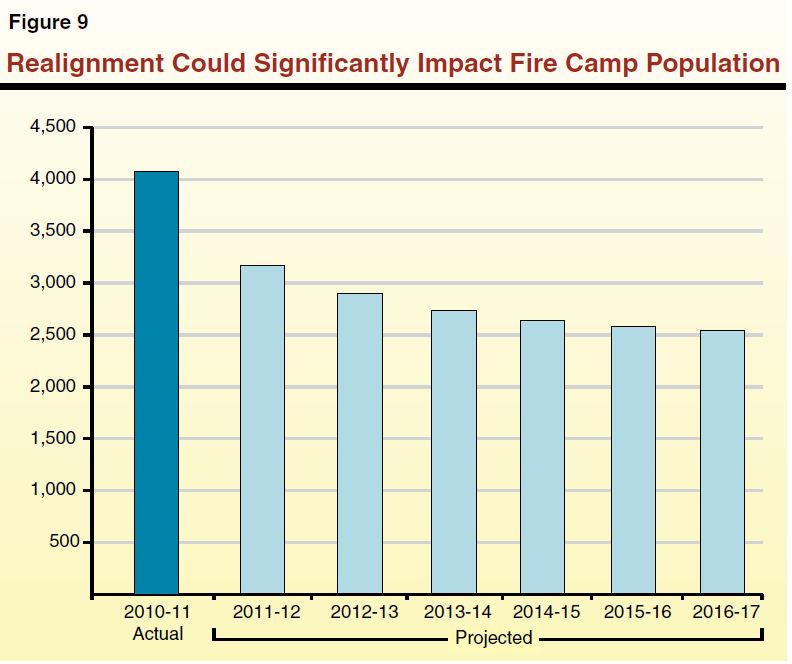

Many Remaining Inmates Likely Ineligible for Fire Camps. Because realignment will result in certain lower–level offenders no longer being admitted to CDCR, the remaining offenders will be more likely to have offense histories and security classifications that make them ineligible to participate in the camps. As a result, it is estimated that the population of inmates in the fire camps will decrease significantly in future years, as shown in Figure 9. Specifically, based on information provided by CDCR, we estimated that the fire camp population could drop to about 2,500 inmates by 2016–17, representing a 38 percent decline from 2010–11.

In part to address the above decline, the realignment legislation authorizes counties to contract for space in fire camps for offenders currently housed in jails. Currently, CDCR is working on implementing such contracts with counties and is proposing to charge $46 per day per offender. This amount is roughly equivalent to CDCR's current cost to house a fire camp inmate, but significantly less than the amount most counties pay to house an offender in jail, which on average is about $100 per day. Currently, it is unclear how many, if any, counties will choose to contract with the state to send local inmates to fire camps. (For a more detailed discussion of the cost of fire camps relative to other placement options available to counties, please see the nearby box.)

Unintended Consequences of the Underutilization of Fire Camps. If the state cannot make full use of its fire camp capacity, there could be several different consequences. Specifically, underutilization of the fire camps would:

- Make it Harder to Meet Federal Court Order. As discussed earlier in this report, capacity in the fire camps is not subject to the three–judge panel order regarding prison overcrowding. Therefore, compliance with the court's population limits is made more difficult to the extent that CDCR is not able to maximize the number of inmates it is able to place in fire camps, rather than in its prisons.

- Increase Prison Costs. Given that the $46 per day average cost for the fire camps is far below the $152 per day DOF currently estimates prison inmates will cost in 2012–13, the state would incur significant costs by not fully utilizing the camps. For example, if the state fails to make use of the nearly 2,000 beds that are projected to be vacant in the fire camps due to realignment, the state could be incurring about $32 million annually in additional prison costs. Further, by not fully using the capacity in the camps, the state would have less ability to close prisons while still complying with the three–judge panel order, and could therefore be unable to achieve the significant savings created by prison closures.

- Make Firefighting More Costly. If the number of fire camp inmates drops significantly, the state may need to rely on contracts with federal or county fire agencies for some fire protection work previously carried out by inmates. According to CalFire, the cost of inmate fire crews is $144 per hour of fire suppression service, while the equivalent numbers for federal and local government crews is $356—more than double the cost. During the 2011 fire season, inmate fire crews provided around 95,000 hours of service, saving the state about $20 million compared to the amount paid if those hours had been contracted to federal or local governments. We also note that federal and local agencies have competing workload that may make them unavailable to assist CalFire, even in cases where the state is willing to pay for their services.

To ensure that the state fully utilizes its fire camp capacity, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to (1) review its fire camp eligibility criteria and (2) identify incentives to encourage inmates to volunteer for fire camps.

Review Eligibility Criteria for Modification. Modification of the eligibility criteria could increase the number of state inmates eligible for the program. For example, the eligibility criteria could be modified to allow high–security inmates that are relatively similar to low–security inmates to serve in fire camps. Specifically, inmates with classification scores of 28 or more are high–security and ineligible for fire camps, while inmates with a classification score of 27 or less are low security and eligible for the fire camps. Yet, it is likely that there is very little difference between inmates with such similar scores. In addition, the current criteria exclude individuals who have more than 15 years of their sentence left to serve. By relaxing this criterion by several years, additional inmates—who can potentially provide a significant number of years of service to the fire camp program—could be made eligible. The Legislature could further direct that CDCR review the criteria used by other states that maintain similar inmate fire camps (such as Arizona, Nevada, Oregon and Washington), to assess how restrictive and effective their criteria have been.

Increase Incentives for Inmate Participation. Even after realignment, the department projects there will be over 30,000 low–security inmates in CDCR. One could reasonably expect that the department could continue to fill 4,500 fire camp beds from that population despite the somewhat restrictive eligibility criteria. It may be that providing additional incentives for inmates to volunteer for fire camps would increase the likelihood that the department could keep the fire camps full with state inmates. This could be accomplished in several ways. For example, the Legislature could increase the amount of pay or credits inmates earn in the fire camps, create an employment transition program to assist fire camp inmates in obtaining jobs before they are released, allow inmates to request assignment to specific fire camps, or institute furlough programs for inmates in the fire camps. It is likely that any costs incurred in developing these incentives would be far outweighed by the state prison and fire protection savings that would accrue.

Inmate Medical Care Services. The state currently provides a variety of medical services to inmates. The services vary according to each inmate's medical needs and are broadly categorized as follows:

- Outpatient Services. Each of the state's 33 prisons has a medical clinic where physicians deliver basic primary care to inmates on an outpatient basis. Inmates receiving care at these clinics range from those who are relatively healthy to those classified as Specialized General Population (SGP), who have chronic medical needs such as regular injections and frequent nursing assessment.

- Low–Acuity Hospital Beds. Low–acuity hospital beds provide inpatient care to inmates who have complex medical problems that require daily nursing care. Low–acuity beds are sub–categorized as either short term—for inmates who will ultimately be returned to the general population—and long term—for inmates who are likely to require care for the rest of their lives.

- High–Acuity Hospital Beds. High–acuity hospital beds are the highest level of inpatient care available within CDCR prisons. These beds are for inmates who require nursing care 24 hours a day and extensive assistance with daily activities such as bathing and eating. Like low–acuity beds, high–acuity beds are also sub–categorized as short or long term.

As mentioned earlier, the three–judge panel convened by the Plata and Coleman courts found that prison overcrowding was the primary cause of the state's failure to deliver adequate medical and mental health care. The three–judge panel identified numerous examples of how overcrowding presents operational challenges for the medical program. Examples of how overcrowding impacts medical care delivery include:

- Makes Prisons Less Secure. Overcrowding forces CDCR to house inmates in gymnasiums and dayrooms that are not designed to house inmates. These nontraditional housing arrangements are less secure and thus security staff impose frequent and persistent lockdowns to maintain control. During lockdowns inmates are generally restricted from leaving their cells without security escorts, which makes it difficult for them to go to medical appointments and receive their daily medications.

- Makes Staffing Difficult. As the inmate population increases, the department has trouble hiring additional medical staff because qualified applicants are often unwilling to work in the stressful environment of an overcrowded prison. This problem is compounded by the fact that many California prisons are located in more rural parts of the state with smaller medical communities from which to hire.

- Increases Evaluation Costs. Overcrowding presents particular challenges at reception center prisons because each new inmate arriving at a reception center must receive a medical evaluation. Historically, the department has struggled to provide these evaluations in a timely manner and, thus, has been forced to divert staff time and resources that could have been used for other purposes to complete evaluations.

- Increases Inmate Medical Needs. Overcrowding also tends to increase the medical needs of prisoners. For example, overcrowding contributes to the spread of infectious diseases.

Current Plan to Construct Additional Medical Care Facilities. As mentioned earlier, AB 900 appropriated $1.1 billion for construction or renovation of medical, mental health, and dental care facilities. In addition, about $900 million of the $2.4 billion appropriated for infill beds is being used to construct CHCF, a new prison hospital in Stockton. Construction of the CHCF has already begun. The facility, which is scheduled to be fully occupied by December 31, 2013, will have a capacity of 1,722 beds—including over 1,000 long–term high– and low–acuity hospital beds. In addition, the federal Receiver intends to use about $750 million authorized in AB 900 to make medical facility upgrades to the state's 33 prisons in order to improve their capacity to deliver medical services to inmates (such as by expanding existing medical clinics).

Additional Outpatient Housing Appears Not Needed. As realignment will significantly reduce prison overcrowding, it will also alleviate many of the operational challenges to the inmate medical care program discussed above. This will make it easier for the department to deliver adequate care to inmates who are currently receiving outpatient care at existing prisons—including SGP inmates—and eliminate the need for the construction of new outpatient housing. For example, lockdowns should decline as a result of realignment, which will make it easier for inmates to get to their health care appointments and receive medication. In addition, reduced overcrowding should make it easier for CDCR to hire needed medical care staff.

Moreover, realignment will reduce the number of new inmates arriving at reception centers from about 9,000 per month to about 2,400 per month, freeing up resources that would otherwise be used on inmate evaluations. Reduced overcrowding will also decrease the spread of infectious diseases, as well as increase the department's flexibility to consolidate SGP inmates at existing prisons designated as "medical hubs." Medical hub prisons generally possess medical clinic space, are in proximity to community hospitals, and have the ability to recruit and retain qualified medical staff.

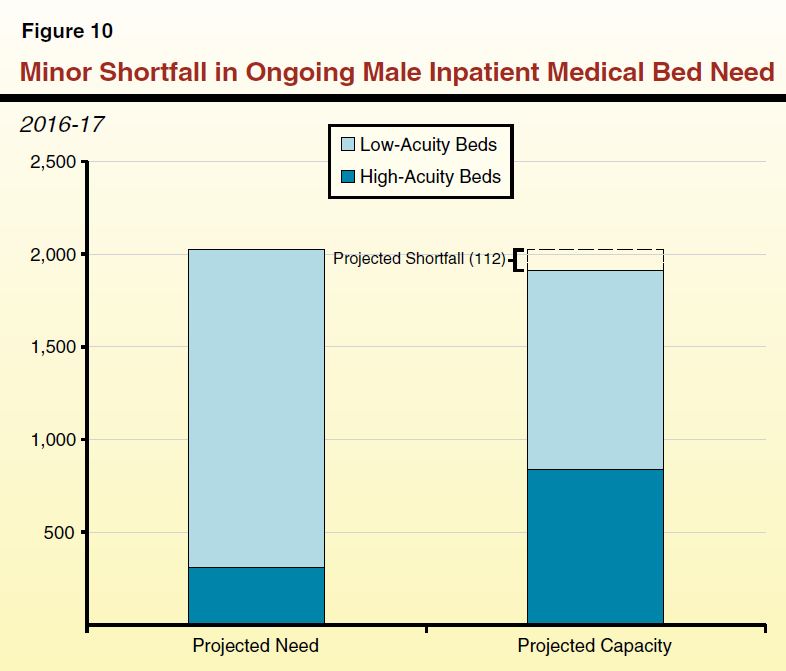

Construction of CHCF Will Largely Meet Inpatient Hospital Bed Needs. Current projections indicate that there could continue to be a small shortage of high– and low–acuity hospital beds for male inmates even after the construction of CHCF and full implementation of realignment. According to data provided by the Receiver, realignment will only reduce the need for high– and low–acuity hospital beds by 9 percent. This is because the inmates needing these particular beds tend to be elderly inmates who are serving sentences for violent and serious crimes and, thus, would not be impacted by realignment. We are projecting that the department will have a surplus of 526 high–acuity beds and a deficit of 638 low–acuity beds upon full implementation of realignment in 2016–17. We note that, according to the Receiver, high–acuity beds can often be converted to low–acuity beds through staffing adjustments should more low–acuity beds be needed. Thus, as shown in Figure 10, our projections indicate that there may be a net shortfall of 112 inpatient beds.

There are, however, several variables that make our projections subject to significant uncertainty. For example, it is very difficult to predict the department's future need for short–term prison hospital beds. Because of a lack of long–term care beds, the department has historically used short–term care beds to provide treatment to inmates in need of long–term care. The CHCF will provide long–term care bed capacity, which should allow the department to begin using short–term care beds for their designated purpose. We expect this will allow the department to develop a more accurate estimate of their actual need for short–term care beds. In addition, there are currently about 250 short–term medical care beds that have been temporarily converted to treat mentally ill inmates and could be converted back to medical uses when various mental health projects are completed, as we discuss later in this report. Our estimate of the overall shortfall in medical beds assumes that all of these beds will be repurposed for medical use when they are no longer needed for mental health treatment, but the actual number could be lower depending on the future mental health needs of the inmate population. Finally, our projection does account for the impact of medical parole, which we estimate will decrease the total need for hospital beds by about 40 beds upon full implementation, but could be higher or lower depending on how the new policy is implemented by the department and Receiver. (Medical parole involves the release of inmates who are medically incapacitated and are found by the department to pose no threat to public safety.) Based on these uncertainties, the actual number of inpatient medical beds needed could be higher or lower by several hundred beds.

Overall Need for Health Care Facility Upgrades Is Uncertain. The administration has not yet submitted a detailed plan for what health care facility upgrades it intends to make in existing prisons with the funds provided in AB 900. A conceptual plan submitted to the Legislature in August 2010 includes renovations at all 33 prisons costing a total of roughly $750 million. Given the poor condition of many CDCR health care facilities, it is likely that some amount of renovation and improvement will be warranted. However, we expect that significant changes will be needed to the plan to account for the impacts of realignment. For example, as we discussed earlier, realignment may make it possible to close some prisons in the future. Thus, it would be unwise to make significant infrastructure investments at such facilities at this time. Furthermore, some reception center prisons will be receiving far fewer inmates after realignment and, thus, may have a reduced need for additional medical facilities. The department may also decide to change the underlying medical mission of some prisons, which would affect what health care facility renovations were needed. For example, the department could choose to consolidate medically complex inmates (such as SGP inmates) at designated medical hubs which may require more facility upgrades at those prisons than others.

Take Wait–and–See Approach Before Approving Additional Hospital Beds. We recommend that the Legislature wait for additional information before approving any additional funds related to the construction of additional high– or low–acuity beds. Our estimates suggest the possibility of a shortfall in these types of beds compared to the estimated need. Given the uncertainties surrounding our estimates, however, we think it makes sense to reevaluate the need over the coming years as realignment is fully implemented and other medical and mental health construction projects are completed. To the extent that additional information demonstrates the need for these types of beds, a portion of the $750 million designated for facility improvements could be used to add the necessary beds. We note that the Receiver does not currently have a proposal for additional medical beds, instead relying on the construction of CHCF to provide this type of medical capacity.

Ensure Health Care Facility Upgrade Plan Accounts for Realignment. The Legislature should review whatever health care facility upgrade plans are eventually submitted to ensure that they account for the impacts of realignment. For example, as we noted earlier, realignment may enable the department to close some facilities in the future. As such, the Legislature should carefully review any medical renovation projects to ensure that they are not occurring at existing facilities that may be candidates for eventual closure.

Inmate Mental Health Classifications. The state provides a variety of mental health services to inmates. The services received by inmates vary according to the severity of their mental illness. There are six levels of service that require inmates to be placed in special housing accommodations.

- Enhanced Outpatient Program (EOP). Inmates classified as EOP receive treatment on an outpatient basis but are so mentally ill that they cannot function in the general population and require specially designed housing units that include readily accessible treatment space.

- EOP/Administrative Segregation Unit (ASU). Inmates classified as EOP/ASU are a subset of the EOP population who have to be temporarily isolated from other inmates because they are a danger to themselves, other inmates, or staff.

- Psychiatric Services Unit (PSU). Inmates classified as PSU are a subset of the EOP population who need to be isolated from other inmates in a maximum security setting for prolonged periods because they are either gang members or have committed a serious offense (such as assaulting a staff member).

- MHCBs. The MHCBs provide short–term (up to ten days) emergency services to inmates who are experiencing mental health crises and require inpatient treatment and 24 hour a day supervision.

- Acute Care. Acute care beds are for inmates requiring a longer duration (generally up to 45 days) of inpatient treatment with 24 hour a day supervision.

- Intermediate Care Facility (ICF). The ICF beds are for inmates requiring inpatient treatment with 24 hour a day supervision for long durations (generally five to nine months). These beds are subcategorized as either high or low security depending on the security risk of the inmates they serve.

Current Plans to Construct Additional Mental Health Care Facilities. As mentioned earlier, AB 900 appropriated $1.1 billion for construction or renovation of medical, mental health, and dental care facilities. Of this amount, the department has allocated about $200 million for the construction of additional mental health treatment and housing capacity at different prisons. This includes eight projects that will provide additional capacity to deliver mental health treatment to a variety of classifications of mentally ill male inmates. In addition, the CHCF will provide roughly 600 additional inpatient mental health beds.

Based on data provided by CDCR, we are projecting that realignment will significantly reduce the number of male inmates in certain mental health classifications. For example, we expect the number of male inmates classified as EOP to decline by about 21 percent—from 4,173 inmates in 2011–12 to 3,303 inmates in 2016–17. As shown in Figure 11, we are projecting that in 2016–17, CDCR will be at or above the capacity needed to deliver treatment to most classifications of mentally ill male inmates—even without the Estrella and Dewitt Nelson projects, which were proposed to include a total of 600 EOP beds. For example, we project that the department's capacity to deliver treatment to EOP male inmates will exceed their EOP population by 427 inmates by 2016–17. In addition, the department is adding capacity in several areas—EOP, EOP/ASU, MHCB, and ICF (low security)—where there already appears to be sufficient capacity to meet the projected need in 2016–17. On the other hand, it appears that the department might have a slight shortfall in capacity in two areas—acute and ICF (high security).

Figure 11

Mental Health Treatment Capacity for Male Inmates Will Meet or Exceed Need in Most Areas

2016–17

|

Level of Care

|

Projected

Capacity

|

Projected

Need

|

Excess/Shortage(–)

|

|

Enhanced outpatient

|

3,730

|

3,303

|

427

|

|

Enhanced outpatient administrative segregation unit

|

519

|

424

|

95

|

|

Psychiatric services unit

|

536

|

482

|

54

|

|

Mental health crisis bed

|

428

|

279

|

149

|

|

Acute care

|

173

|

223

|

–50

|

|

Intermediate care (low security)

|

390

|

266

|

124

|

|

Intermediate care (high security)

|

606

|

698

|

–92

|

|

Totals

|

6,382

|

5,675

|

707

|

Identify Alternative Uses for Projected Surplus of Mental Health Capacity. As discussed above, it appears that the department will have surplus treatment capacity in several areas after the completion of the eight infrastructure improvement projects that are currently underway. Since all of these projects have already broken ground, it is probably not cost effective to stop them now. Instead, to the extent that these facilities are not needed for delivering the type of mental health treatment for which they are designed, the department should consider repurposing them for other uses. For example, the department should consider repurposing certain types of treatment space for which there will be surplus capacity (such as for MHCBs) to deliver other types of treatment in areas where there is a projected shortfall (such as acute and high–security ICF). Alternatively, to the extent the excess capacity is no longer needed for mental health treatment, the department should consider repurposing the space to provide medical treatment or rehabilitation programs. In view of the above, we recommend the Legislature direct CDCR to report at budget hearings regarding its mental health facility plans, including how it plans to utilize the projected surplus of capacity following the full implementation of realignment.

CDCR Provides a Variety of Programs to Inmates and Parolees.

The CDCR currently provides a variety of rehabilitation programs

to inmates, including academic and vocational education and

substance abuse treatment. In addition, the department provides

substance abuse treatment and employment–related programs for

parolees. The enacted 2011–12 budget included about $460 million

for rehabilitation programs. Figure 12 summarizes the department's current funded treatment capacity in each of its major program areas for 2011–12. We note, however, that program capacity may increase in 2012–13. This is because the Governor's budget for 2012–13 proposes to backfill a one–time $101 million reduction to inmate and parolee rehabilitation programs that was included in the 2011–12 budget. At the time of this report, the department had not presented a plan for how it will adjust the amount and type of programs as a result of the $101 million restoration. Consequently, the Governor's budget assumes that the programs will be funded in 2012–13 at their levels before the $101 million reduction.

Figure 12

Funded Rehabilitation Program Capacity

2011–12

|

|

|

|

In–Prison Programs

|

|

Academic education

|

32,388

|

|

Vocational education

|

4,779

|

|

Substance abuse treatment

|

3,500

|

|

Parole Programs

|

|

Substance abuse treatment

|

21,193

|

|

Education

|

3,758

|

|

Employment

|

2,536

|

In recent years, CDCR has started using assessment tools in order to identify the likelihood that inmates and parolees will reoffend, as well as to determine what types of programs these offenders would most benefit from in order to reduce their likelihood of reoffending. Based on these assessments, state prison officials and parole agents should be able to make more informed decisions about the most appropriate programs for offenders, as well as make determinations about how best to prioritize limited program space among all of the inmates and parolees. Inmates and parolees are categorized as having a low, moderate, or high need for programming in five areas. According to CDCR, parole agents are supposed to use this information along with other criteria (such as a parolee's history of substance abuse) to assign parolees to programs. Inmates are further categorized as having either a low, moderate, or high risk of reoffending based on an assessment of factors such as their criminal history. The department's policy is that inmates who are assessed as having a moderate to high need to for programming and as having a moderate to high risk of reoffending are given priority for placement in programs. Among those inmates who are both moderate to high risk and moderate to high need, priority for placement is given to inmates who are nearing the end of their prison term.

Research Indicates Many Programs Can Reduce Recidivism. Although most of the programs offered by CDCR have not been regularly evaluated for outcomes, research throughout the country suggests that many programs can significantly reduce recidivism. For example, one study by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy found that programs such as substance abuse treatment, cognitive behavioral treatment, and vocational and academic education reduce recidivism rates by an average of between 5 percent and 9 percent. To put this in perspective, if CDCR was able to reduce the recidivism rates of program participants by 9 percent, the percentage of inmates returning to prison would decline from the current average of 65 percent to 59 percent. Research also suggests that programs are more successful at reducing recidivism when they follow certain principles, which include the following:

- Program Model. Programs should be modeled on widely accepted principles of effective treatment and, ideally, research demonstrating that the approach is effective at achieving specific goals.

- Risk Principle. Treatment should be targeted towards inmates identified as most likely to reoffend based on their risk factors—for example, those inmates who display high levels of antisocial or criminal thinking or severe mental illness. Focusing treatment resources on these inmates will achieve greater net benefits compared to inmates who are low risk to reoffend even in the absence of treatment programs, thereby generating greater "bang for the buck."

- Needs Principle. Programs should be specifically designed to address those offender needs which are directly linked to their criminal behavior, such as antisocial attitudes, substance abuse, and illiteracy. Programs that attempt to address multiple areas of need tend to be more effective at reducing recidivism rates than those programs that target only one area of need.

- Responsivity Principle. Treatment approaches should be matched to the characteristics of the target population. For example, research has shown that male and female inmates respond differently to some types of treatment programs. Important characteristics to consider include gender, motivation to change, and learning styles.

- Dosage. The amount of intervention should be sufficient to achieve the intended goals of the program, considering the duration, frequency, and intensity of treatment services. Generally, higher–dosage programs are more effective than low–dosage interventions.

- Trained Staff. Staff should have proper qualifications, experience, and training to provide the treatment services effectively.

- Positive Reinforcement. Behavioral research has found that the use of positive reinforcements—such as increased privileges and verbal encouragement—can significantly increase the effectiveness of treatment, particularly when provided at a higher ratio than negative reinforcements or punishments.

- Post–Treatment Services. Some services should continue after completion of intervention to reduce the likelihood of relapse and reoffending. Continuing services is particularly important for inmates transitioning to parole.

- Evaluation. Program outcomes and staff performance should be regularly evaluated to ensure the effectiveness of the intervention and identify areas for improvement.

CDCR Is Not Adhering to Certain Principles of Effective Programming. The department is not currently adhering to some of the above principles of effective programming as well as it could be. For example, the Bureau of State Audits (BSA) recently found that CDCR is not always using needs assessments to assign inmates to programs. Although the department assesses the programming needs of prisoners, it does not often use the results of the assessments to determine where inmates will be assigned. This often means that inmates are assigned to prisons where the programs they need are not offered. In addition, the department does not always use the results of the needs assessment when assigning inmates to programs. For example, despite the department's policy of prioritizing placements based on an inmate's assessed level of need, BSA found that many inmates with low needs or with no needs assessment at all were being placed in programs ahead of inmates with moderate or high needs. The bureau also found that parole agents were not consistently using needs assessments to place parolees in programs. According to BSA, the department's failure to properly use the needs assessment was largely attributable to a lack of training for staff using the tool. In addition, we find that the department has historically not provided multiple types of programs to inmates that have multiple areas of need—despite research suggesting that this is a best practice because so many inmates have multiple areas of need that contribute to their criminal behavior. Instead, inmates in CDCR have historically been assigned to only one program even if they are assessed as having multiple needs.

Based on data provided by CDCR, it also appears that the department is not always following its policy of placing inmates in programs based on their assessed risk to reoffend. Enrollment data for education programs indicate that almost 40 percent of the enrolled inmates are assessed as having a low risk to reoffend compared to about 30 percent each for those assessed as having moderate and high risk to reoffend. Finally, there is currently a lack of evaluation of CDCR's rehabilitation programs. This makes it difficult to determine whether the department's programs are actually successful at reducing recidivism.

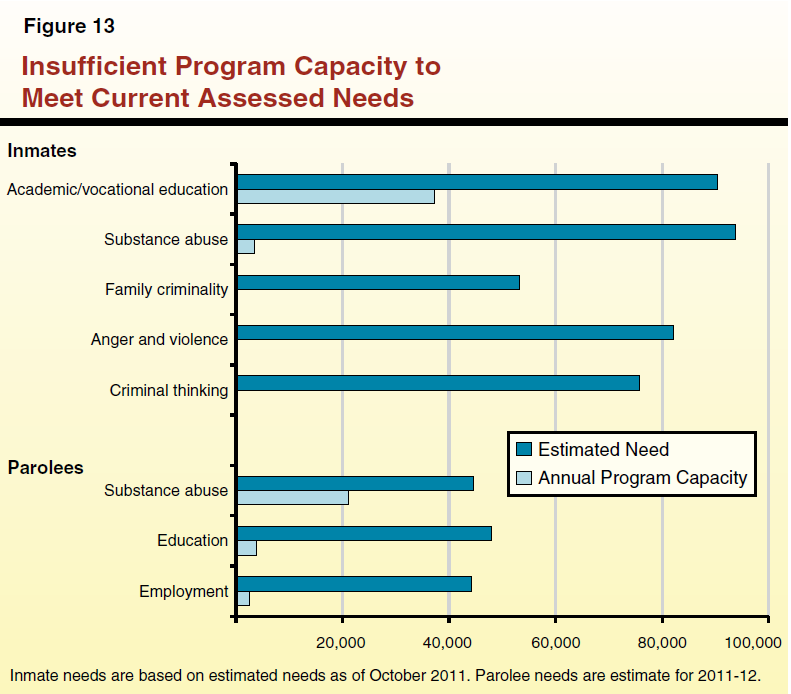

CDCR Lacks Sufficient Program Capacity to Meet Identified Need. As shown in Figure 13, there is currently a substantial mismatch between the needs of inmates and parolees and the programs that are available to them. While CDCR assesses inmates for needs in five different areas—(1) substance abuse, (2) academic and vocational education, (3) criminal thinking, (4) anger and violence, and (5) family criminality—it only currently offers programming in two of them, substance abuse and education. The department assesses parolees for needs in three areas—substance abuse, education, and employment—but lacks sufficient capacity to meet the needs of parolees in all three areas.

Realignment is projected to reduce the parolee population by about 72 percent upon full implementation, and the inmate population by about 24 percent over the coming few years. The decrease in population will be concentrated in certain types of offenders—specifically, parole violators and those who are nonserious, nonsex, and nonviolent offenders. As such, the rehabilitative needs of the remaining inmate and parole population will differ from the needs of the pre–realignment population.

While the department has not provided us with an estimate of what the post–realignment inmate and parolee needs will be, based on the limited data provided by CDCR it appears there may be a couple of significant changes in the risk and needs profile of the remaining population. Most notably, it appears that the post–realignment inmate and parolee population will have a relatively higher proportion of inmates who have a lower risk to reoffend, as well as a relatively lower proportion of inmates who have a high risk to reoffend. This is likely because the inmates and parolees remaining after realignment will be relatively older because they are serving longer sentences because of their current or prior violent and serious crimes. Research indicates that the risk of reoffending decreases significantly with age. Alternatively, the inmates and parolees being realigned tend to be repeat offenders who regularly cycle in and out of prison and thus have a higher risk to reoffend on average. In addition, it appears the post–realignment inmate and parole population will have a relatively smaller proportion of offenders in need of substance abuse treatment.

Given that the parole population is projected to decrease more than the prison population, there may be an overabundance of resources in parole programs relative to in–prison programs after realignment. Finally, the population remaining in prison and on parole after realignment will consist of offenders with more prior serious, violent, and sex offenses who are serving longer sentences. This means that at any point in time there will be fewer inmates within four years of release—a segment of the prison population that, according to the department, is currently given the highest priority for placement in programming.

Reprioritize Programs Based on Principles of Effective Programs. Realignment presents an opportunity for the department to redesign its programs so that they more closely adhere to the assessed needs of the inmate and parolee populations, as well as the principles of effective programming. The reduction in the number of inmates and parolees may reduce the need to spend funding on certain programs, allowing reinvestment in other programs to better address the needs of the remaining population. For example, the much larger reduction in the parole population might free up some resources that could be utilized for in–prison programs.

Whatever changes could be made, however, cannot be done thoughtfully without CDCR first completing an evaluation of what the risk and needs of its future population are likely to be. Based on these findings, the state could prioritize program funding to deliver those programs most suited to the needs of the remaining population. For example, the department could develop in–prison programs in areas where inmates currently have needs that are not being met (such as criminal thinking, anger and violence, and family criminality). In addition, because there will be fewer inmates within four years of release, the department could expand the group of inmates who are given higher priority for program placement to include those with more time remaining on their sentences. Alternatively, the department could continue to prioritize inmates within four years of release but provide them with more types of programming in order to address multiple areas of need simultaneously. Finally, a small amount of resources could also be reprioritized to evaluate CDCR programs to determine which ones are most effective at reducing recidivism, particularly for the more serious and violent offenders that are going to remain in CDCR post–realignment. Evaluations would then allow the department to direct greater resources to those programs in the future.

Withhold Funding Until More Information Is Provided. We recommend that the Legislature not approve the Governor's proposed restoration of the current–year, one–time reduction of $101 million to rehabilitation programs until the department has presented a plan for how it will use the funding proposed by the Governor to modify its programs to account for the impacts of realignment and conform to principles of effective programming. It is our understanding that the department is currently developing a plan to modify its programs that will be completed this spring. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to present its plan during budget subcommittee hearings this spring. In developing the plan, the department should (1) provide projections of the programming needs and risks of inmates and parolees following realignment, (2) identify steps it is taking to modify the type and amount of programs it will offer to address the needs of the remaining inmate and parole population, and (3) specify how it will address areas where it is not adhering to the principles of effective programming as well as it could be (such as assigning inmates to programs based on risk and need and regularly evaluating programs). If satisfied with the department's plan, the Legislature could approve funding in an amount and allocation consistent with the plan. In future years, the Legislature can monitor CDCR's implementation of its plan and hold the department accountable for any failures to make substantial improvements.

The 2011 realignment of certain adult offenders, which was prompted in part by the federal court order to reduce overcrowding, will fundamentally change CDCR. In particular, realignment will result in a significant decline in the inmate and parole populations, resulting in a much different mix of offenders left in the state's correctional system. Consequently, we offer a number of recommendations designed to ensure compliance with the federal court, as well as better align CDCR's facilities, health care system, and rehabilitation programs with the state inmate and parole populations that will be left in CDCR in the future. Figure 14 summarizes our recommendations.

Figure 14

Summary of Recommendations

|

|

- Request more time for compliance with federal court order to reduce overcrowding.

|

- Match facilities to remaining population by using existing facilities for high–security inmates, using various strategies to address any remaining shortfall, reducing the size of Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900, Solorio), and identifying facilities for possible closure.

|