On February 1, 2012, all redevelopment agencies in California were dissolved and the process for unwinding their financial affairs began. Given the scope of these agencies' funds, assets, and financial obligations, the unwinding process will take time. Prior to their dissolution, redevelopment agencies (RDAs) received over $5 billion in property tax revenues annually and had tens of billions of dollars of outstanding bonds, contracts, and loans.

This report reviews the history of RDAs, the events that led to their dissolution, and the process communities are using to resolve their financial obligations. Over time, as these obligations are paid off, schools and other local agencies will receive the property tax revenues formerly distributed to RDAs.

The report discusses these major findings:

- Although ending redevelopment was not the Legislature's objective, the state had few practical alternatives.

- Ending redevelopment changes the distribution of property tax revenues among local agencies, but not the amount of tax revenues raised.

- Decisions about redevelopment replacement programs merit careful review.

- The decentralized process for unwinding redevelopment promotes a needed local debate over the use of the property tax.

- Key state and local choices will drive the state fiscal effect.

The report recommends the Legislature amend the redevelopment dissolution legislation to address timing issues, clarify the treatment of pass–through payments, and address key concerns of redevelopment bond investors.

Californians pay over $45 billion in property taxes annually. County auditors distribute these revenues to local agencies—schools, community colleges, counties, cities, and special districts—pursuant to state law. Property tax revenues typically represent the largest source of local general purpose revenues for these local agencies.

In 1945, the Legislature authorized local agencies to create RDAs. Several years later, as shown in Figure 1, voters approved a redevelopment financing program referred to as "tax increment financing." Under this process, a city or county could declare an area to be blighted and in need of urban renewal. After this declaration, most of the growth in property tax revenue from the "project area" was distributed to the city or county's RDA as "tax increment revenues" instead of being distributed as general purpose revenues to other local agencies serving the area. Under law, tax increment revenues could be used only to address urban blight in the community that established the RDA.

During Its Early Years, Redevelopment Was a Small Program

During the 1950s and 1960s, few communities established redevelopment project areas and most project areas were small—typically 10 acres (about six square city blocks) to 100 acres (an area about one–fifth of a square mile). The small size of the early project areas reflected, in part, competing community interests in property tax revenues, particularly from school and community college districts that otherwise would receive about half of any growth in property tax revenues. (Under the state school financing system of the time, the state did not backfill K–14 districts if some of their property tax revenues were redirected to RDAs.) Community interest in education and other local programs, therefore, served as a fiscal check on redevelopment expansion.

The limited size of redevelopment project areas during this period also reflected the fiscal authority local governments had to raise funds from other sources to pay for local priorities. During this era, for example, the State Constitution allowed local governments to raise property and other tax rates upon a vote of their governing body and without local voter approval. Cities and counties also had wide authority to impose fees and assessments.

Use of Redevelopment Expanded After SB 90 and Proposition 13

After its modest beginnings, use of redevelopment expanded significantly in the 1970s and 1980s due to two major state policy changes. First, passage of Chapter 1406, Statutes of 1972 (SB 90, Dills) created a system of school "revenue limits," whereby the state guarantees each school district an overall level of funding from local property taxes and state resources combined. Thus, if a district's local property tax revenues do not grow—due to redevelopment or for other reasons—the state provides additional state funds to ensure that the district has sufficient funds to meet its revenue limit. Second, Proposition 13 in 1978 (and later Proposition 218 in 1996) significantly constrained local authority over the property tax and most other local revenues sources. These measures did not, however, reduce local authority over redevelopment.

With fewer fiscal checks and less revenue authority, cities (joined by a small number of counties) no longer limited their project areas to small sections of communities, but often adopted projects spanning hundreds or thousands of acres and frequently including large tracts of vacant land. Some jurisdictions placed farmland under redevelopment. At least two cities placed all privately owned land in the city under redevelopment.

Legislature Took Steps to Constrain Redevelopment

Over time, the expanded use of redevelopment led to these agencies receiving an increasing share of property taxes collected under the 1 percent rate. This, in turn, spawned concern that redevelopment—a program established as a tool to address defined pockets of urban blight—was decreasing funds needed for other local programs and increasing state costs to support K–14 education.

Beginning in the 1980s and increasingly through 2011, state lawmakers took actions to constrain local governments' use of redevelopment, including tightening the definition of blight, imposing timelines on project areas, and prohibiting new projects on bare land. Concerned that RDAs were not using their authority to develop affordable housing, the Legislature enacted laws strengthening the statutory requirement that RDAs spend 20 percent of their tax increment revenues developing housing for low and moderate income households. The Legislature also began restricting the amount of "pass–through" payments RDAs provided other local agencies in the hope that these other local agencies might provide more active oversight. (Two nearby boxes provide information on a major reform measure enacted in 1993 and pass–through payments.)

Redevelopment Reform: AB 1290

Sponsored by the statewide redevelopment association, Chapter 942, Statutes of 1993 (AB 1290, Isenberg), sought to address long–standing concerns about the misuse of redevelopment and to refocus the program on eradicating urban blight.

This measure:

- Defined a "blighted" area as one that is predominately urbanized and where certain problems are so substantial that they constitute a serious physical and economic burden to a community that cannot be reversed by private or government actions, absent redevelopment.

- Replaced the process whereby local agencies and redevelopment agencies (RDAs) negotiated the amount of pass–through revenues on a case–by–case basis with a statutory formula for sharing tax increment revenues.

- Limited RDA ability to provide subsidies and assistance to auto dealerships, large volume retailers, and other sales tax generators.

One year after AB 1290 took effect, this office reviewed the new project areas adopted pursuant to the law. We found no evidence that redevelopment projects established in 1994 were smaller in size or more focused on eliminating urban blight than project areas adopted in earlier years. (See Redevelopment After Reform: A Preliminary Look on our website.)

Because most of these new statutory restrictions applied only to new redevelopment project areas and existing projects could last for over 50 years, many redevelopment projects were not affected substantially by the changes. The RDAs also continued to find ways of establishing large new project areas despite the increasingly narrow statutory definitions of blight and developed land.

By 2009–10, RDAs were receiving over $5 billion in property taxes annually—a redirection of 12 percent of property tax revenues from general purpose local government use for redevelopment purposes. The state's costs to backfill K–14 districts for the property taxes redirected to redevelopment exceeded $2 billion annually.

Pass–Through Payments

Many redevelopment agencies (RDAs) made "pass–through payments" to local agencies to partly offset these agencies' property tax losses associated with redevelopment. State laws regulating these payments changed over the years.

Pre–1994 Law Allowed Amount of Payments to Be Negotiated. Before 1994, the terms of pass–through payments were negotiated between the RDA and a local agency. Most negotiations occurred between a city RDA and the county and special districts. (The K–14 districts typically were not active in these negotiations—in part because, after 1972, the state backfilled them for any property tax losses.) Pass–through agreements sometimes were negotiated as part of a settlement of a dispute over the legality of a proposed project area. Occasionally, RDAs agreed to provide 100 percent pass–through payments to the county and special districts, meaning that these agencies received their entire share of the property tax in pass–through payments. In these cases, the only property tax revenue that the RDA retained was the K–14 districts' and city's share.

Assembly Bill 1290 Replaced Negotiated Agreements With a Schedule of Payments. Seeking to encourage greater local oversight of RDA activities while still requiring RDAs to mitigate their fiscal effects on other local agencies, Chapter 942, Statutes of 1993 (AB 1290, Isenberg) eliminated RDA authority to negotiate pass–through payments and established a statutory formula for pass–through payment amounts. In contrast to the earlier negotiated agreements, post–1993 pass–through payments are distributed to all local agencies and the amount each agency receives is based on its proportionate share of the 1 percent property tax rate in the project area.

Budget Acts Shifted Funds From Redevelopment

Beginning in the 1990s, the state began taking actions in its annual state budget to require RDAs to shift some of their revenues to schools to offset the state's increased costs associated with redevelopment. The shifted funds typically were deposited into countywide accounts referred to as ERAF (Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund) or SERAF (Supplemental Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund). These state budgetary actions occurred nine times between 1992 and 2011.

Concerned about the magnitude and frequency of these budget shifts, redevelopment advocates (along with groups interested in transportation and other elements of local finance) sponsored Proposition 22. Among other things, this initiative measure (approved by the state's voters in November 2010), limits the Legislature's authority over redevelopment and prohibits the state from enacting new laws that require RDAs to shift funds to schools or other agencies.

Governor's Budget Proposed Ending Redevelopment

Citing a need to preserve public resources that support core government programs, the Governor's 2011–12 budget proposed dissolving RDAs. Under the Governor's plan, property taxes that otherwise would have been allocated to RDAs in 2011–12 would be used to (1) pay existing redevelopment debts (such as bonds an agency sold to finance a retail or housing development), (2) make pass–through payments to other local governments, and (3) offset $1.7 billion of state General Funds costs. Any remaining redevelopment funds would be allocated to the other local agencies that serve the former project area, with the allocations based largely on each agency's share of property tax revenues in the project area.

In subsequent years under the Governor's plan, all remaining redevelopment funds (after payment of redevelopment debts and pass–throughs) would be allocated to local agencies based on their property tax shares, except that some funds were redirected from special districts to counties. The Governor's plan further specified that, beginning in 2012–13, the additional K–14 property tax revenues would be provided to schools to supplement any funds they would have received under the state's Proposition 98 guarantee.

Legislature Rejected Governor's Proposal

The administration's 2011 proposal—SB 77 (Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) and AB 101 (J. Pérez)—launched a major debate within the Legislature regarding the role of redevelopment and the importance and costs of the program. Because the Governor's proposal distributed redevelopment property tax revenues in a manner that differed somewhat from existing property tax allocation laws (that is, it paid pass–through payments and shifted some special district property taxes to counties), the measures to implement it required approval by a two–thirds vote of the Legislature pursuant to the provisions of Proposition 1A (2004).

In March, SB 77 failed by one vote in the Assembly to secure the two–thirds vote it required to pass. Assembly Bill 101 was not taken up on the floor of the Senate. After March, legislative debate regarding redevelopment focused on proposals that (1) allowed RDAs to continue, albeit with modifications and with ongoing funding provided to schools, and (2) followed the existing statutory formulas related to property tax allocations, thereby avoiding Proposition 1A's two–thirds vote requirement.

Measures Enacted to Reform or End Redevelopment

In June 2011, the Legislature approved and the Governor signed two pieces of legislation:

- Chapter 5, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 26, Blumenfield), imposed an immediate freeze on RDA authority to engage in most of their previous functions, including incurring new debt, making loans or grants, entering into new contracts or amending existing contracts, acquiring or disposing of assets, or altering redevelopment plans. The bill also dissolved RDAs, effective October 1, 2011 and created a process for winding down redevelopment financial affairs and distributing any net funds from assets or property taxes to other local taxing agencies.

- Chapter 6, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 27, Blumenfield) allowed RDAs to opt into a voluntary alternative program to avoid the dissolution included in ABX1 26. The program included annual payments to K–12 districts ($1.7 billion in 2011–12 and about $400 million in future years) to offset the fiscal effect of redevelopment.

Recognizing the considerable legal uncertainties pertaining to both measures, the Legislature specified its policy preferences in the legislation. Specifically, if any major element of ABX1 27 (such as the required payments to schools) was determined to be unconstitutional, ABX1 27 specified that all of its provisions would be null and void. In addition, ABX1 26 specified that if ABX1 27 were rendered inoperative, this would have no effect on the provisions of ABX1 26. Thus, if the redevelopment reform measure were overturned, all RDAs would be subject to the dissolution provisions in ABX1 26.

One–Time State Fiscal Relief; Long–Term Funding for Schools

The budget assumed that the increased school funding from these two bills would raise $1.7 billion in 2011–12 (with most of the funds related to payments made by RDAs opting into the ABX1 27 program and a smaller amount resulting from increased school property taxes resulting from ABX1 26). Legislation adopted in March 2011 related to education directed the Department of Finance (DOF) to adjust the Proposition 98 calculations so that these increased funds would offset 2011–12 state General Fund spending obligations for schools. In 2012–13 and future years, ABX1 26 and ABX1 27 were estimated to generate a lower sum for K–12 school districts, potentially about $400 million initially. The March 2011 education bill directed DOF not to adjust the Proposition 98 calculations to reflect these increased funds in 2012–13 and later. As a result, going forward, any funds that K–12 districts received from ABX1 26 and ABX1 27 would be in addition to amounts required under Proposition 98.

RDAs Expedited Activities

During the legislative debate over redevelopment, many RDAs took actions to transfer or encumber assets and future tax increment revenues in case the Governor's proposal, or something similar, was enacted.

Rush to Issue Debt. Tax allocation bonds, which pledge future tax increment revenues to make principal and interest payments, are RDAs' primary borrowing mechanism. In the first six months of 2011, RDAs issued about $1.5 billion in tax allocation bonds, a level of debt issuance greater than during all 12 months of 2010 ($1.3 billion). The increase in bond issuance from 2010 to 2011 was even more notable because it occurred despite RDAs being required to pay higher borrowing costs. Specifically, about two–thirds of the bond issuances in 2011 had interest rates greater than 7 percent—compared with less than one–quarter of bond issuances in 2010. In fact, RDAs issued more tax allocation bonds with interest rates exceeding 8 percent during the first six months of 2011 than they had in the previous ten years.

Rush to Transfer Assets. Many RDAs also took actions to transfer redevelopment assets—land, buildings, parking facilities—to other local agencies, typically the city or county that created the RDA. One common approach was for the RDA and city council to hold a joint hearing in which the RDA transferred (and the city accepted) ownership of all RDA property and interests. After one city council called a special meeting in March to approve such a transfer, the mayor was reported in newspapers as saying, "We have no funds now in our redevelopment coffers that can be taken." In addition to transferring existing assets, many RDAs entered into "cooperation agreements" with their city, county, or another local agency. Under these agreements, the city, county, or other local agency would carry out existing and future redevelopment projects. Local agency staff and officials assumed that—if the Governor's proposal were enacted—the cooperation agreements would be an enforceable contract, requiring the allocation of future tax increment revenues as payment for performing the agreement. For example, the RDA of the City of San Bernardino entered into a project funding agreement that pledged $525 million in future tax increment revenue to a local non–profit corporation. The corporation—controlled by local elected officials including the mayor and two city council members—was given the responsibility of carrying out a list of projects from the RDA's capital improvement plan. Local cooperation agreements typically were not arm's length transactions, but rather, were between closely related governmental bodies with no third party involved.

Court Found Redevelopment Reform Measure Unconstitutional

Within three weeks of the Governor signing the redevelopment legislation, the California Redevelopment Association (CRA) and the League of California Cities filed petitions with the California Supreme Court challenging ABX1 26 and ABX1 27 on constitutional grounds. The CRA/League's argument focused on sections of the Constitution (1) establishing a special fund for tax increment revenues (Article XVI, Section 16, added by Proposition 18 of 1952) and (2) restricting the Legislature's authority to shift funds from RDAs (Article XIII, Section 25.5, added by Proposition 22).

On December 29, 2011, the court upheld ABX1 26, saying that the Legislature had authority to dissolve entities that it created and that neither Article XVI, Section 16 (the tax increment financing provision), nor Article XIII, Section 25.5 (Proposition 22) limited the Legislature's power to dissolve RDAs.

In reviewing ABX1 27, in contrast, the court found the measure unconstitutional because it required RDAs to make payments to schools as a condition of these agencies' continuation. The court found this violated Proposition 22's prohibition against the state "directly or indirectly" requiring an RDA to transfer funds to schools or to any other agency. Finally, in order to address the delays associated with litigation and an earlier court stay, the court extended a variety of dates and deadlines in ABX1 26 by four months, including the date RDAs were required to shut down.

The Supreme Court's ruling meant all RDAs were subject to ABX1 26 and set in motion the process laid out in ABX1 26 for shutting down and disbursing their assets. The process focuses on two goals: (1) ensuring existing financial obligations are honored and paid and (2) minimizing any additional RDA obligations so that more funds are available to transfer for other governmental purposes.

The dissolution process contains four key elements:

- Local Management and Oversight. In most cases, the city or county that created the agency is managing its dissolution as its successor agency. An oversight board, with representatives from the affected local taxing agencies—K–14 districts, the county, the city, and special districts—supervises the successor agency's work. (We describe the work of the successor agency and oversight board further below.) All financial transactions associated with redevelopment dissolution are handled by the successor agency and the county auditor–controller.

- List of Future Redevelopment Expenditures. Various local parties are tasked with developing and reviewing lists of redevelopment "enforceable obligations." This term includes payments for redevelopment bonds and loans with required repayment terms, but typically excludes payments for projects not currently under contract. Only those financial obligations included on these lists may be paid with revenues of the former RDA. The first list of redevelopment obligations is called the Enforceable Obligation Payment Schedule (EOPS); later versions of this list are called the Recognized Obligation Payment Schedule (ROPS). Each ROPS is forward looking for six months. Most local agency cooperation agreements may be included on the EOPS, but not the ROPS.

- Local Distribution of Funds. Funds that formerly would have been distributed to the RDA as tax increment are deposited into a redevelopment trust fund and used to pay obligations listed on the EOPS/ROPS. Any remaining funds in the trust fund—plus any unencumbered redevelopment cash and funds from asset sales—are distributed to the local agencies in the project area.

- State Review. Actions of local oversight boards are subject to review by DOF. Actions by the county auditor–controller are subject to review by the State Controller's Office (SCO). The SCO also reviews redevelopment asset transfers completed during the first half of 2011 to determine whether any of them were improper and should be reversed.

Below, we provide more information about the responsibilities of the state and local entities that play a role in winding down redevelopment.

Final Actions of the RDA and Its City or County

Before its dissolution, a key responsibility of an RDA was preparing an EOPS delineating the payments it must make through December 31, 2011. Assembly Bill X1 26 required the agency to post the EOPS to its website and to transmit copies to DOF, SCO, and its county auditor–controller by late August 2011. Under ABX1 26, payments or actions of an RDA pursuant to its EOPS do not take effect for three business days. During this time, DOF is authorized to request a review of the RDA action and DOF has ten days to approve the action or return it to the RDA for reconsideration.

In part due to confusion regarding a partial stay of ABX1 26 while the State Supreme Court reviewed this legislation, this initial oversight function was not implemented fully. The DOF advises us that many EOPS were delayed and that about two dozen of the state's approximately 400 agencies still have not provided an EOPS. Very few of these payment schedules were reviewed in detail by DOF and, in those cases in which it raised concerns, the department is uncertain whether local agencies corrected their EOPS.

Successor Agency

Unless it voted not to, each city or county that created an RDA became its successor agency on February 1, 2012. The successor agency manages redevelopment projects currently underway, makes payments identified on the EOPS (and later, the ROPS), and disposes of redevelopment assets and properties as directed by the oversight board. A separate agency (discussed later in the report) manages the RDA's housing assets. The work of the successor agency is funded from the former tax increment revenues. (A nearby box discusses the limitations on the agency's administrative spending.) The agency's liability for any legal claims is limited to the funds and assets it receives to perform its functions.

Successor Agency Administration Costs

Subject to the approval of the oversight board, Chapter 5, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 26, Blumenfield) specifies that successor agencies may spend $250,000 or up to 5 percent of the former tax increment revenues for administrative expenses in 2011–12 and $250,000 or up to 3 percent in future years. The county auditor–controller may reduce these amounts, however, if there are insufficient funds to pay enforceable obligations and the administrative costs of the county auditor–controller and State Controller. Funds for successor agency administration may be supplemented with money from other revenue sources, such as funds reserved for project administration.

Decision Whether to Serve as Successor Agency. Based on information available at this time, it appears that all cities and counties with RDAs became successor agencies with the exception of the Cities of Bishop, Los Angeles, Los Banos, Merced, Pismo Beach, Riverbank, and Santa Paula. In hearings to discuss this matter, local elected representatives and staff typically indicated that they thought that serving as a successor agency would put their community in a better position to advocate for continuing their projects and maintaining redevelopment properties. Cities electing not to serve as successor agencies, however, voiced offsetting concerns related to (1) the limitation on funds to pay successor agency administration expenses and (2) potential liabilities associated with terminated projects.

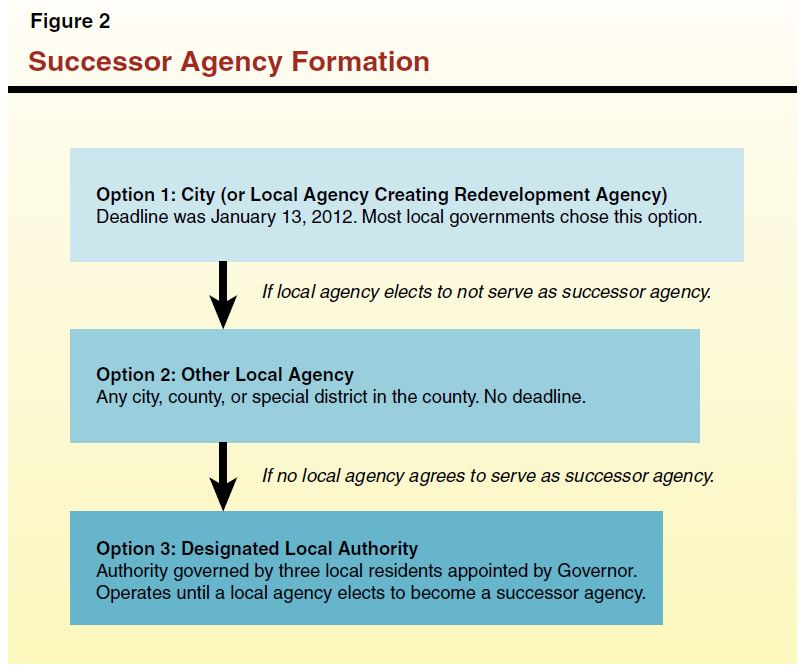

When a City or County Elects Not to Serve as a Successor Agency. Figure 2 summarizes how a successor agency is designated in cases when a local agency that created an RDA declines the role. In the case of the City of Los Angeles and the cities in Merced, Ventura, and Stanislaus Counties, no other local agency in the county agreed to serve as their successor agency and the Governor appointed county residents to serve on three–member governing boards of the "designated local authorities." Each authority will serve as the successor agency until a local agency elects to serve in this capacity.

Develops Key Document: ROPS. The successor agency is responsible for drafting a ROPS delineating the enforceable obligations payable through June 30, 2012 and their source of payment, and then additional ROPS every six months thereafter. There are two major differences between the ROPS and the earlier EOPS. First, ROPS are subject to the approval of an oversight board (see next page) and certification by the county auditor–controller. Second, most debts owed to a city or county that created the RDA are no longer considered to be enforceable obligations and thus may not be listed on the ROPS. This includes most of the cooperation agreements established in 2011 and many other types of financial obligations between an RDA and the government that created it.

Frequently, RDA–city or RDA–county financial agreements were established for the purpose of reducing the sponsoring government's costs or increasing its revenues. For example, many RDAs paid a significant share of their sponsoring local government's administrative costs (such as part of the salaries for the city council and city manager). Doing so freed up city or county funds so that they could be used for other purposes. Some RDAs also lent money to their city or county without charging interest on the loans, allowing the city or county to invest the funds and keep the earnings. Other sponsoring governments charged their RDAs above market interest rates for loans, thereby allowing the city or county to benefit from unusually high interest earnings. Under ABX1 26, many of these obligations would not be eligible to be placed on the ROPS.

Oversight Board

Each successor agency has an oversight board that supervises it. The oversight board is comprised of representatives of the local agencies that serve the redevelopment project area: the city, county, special districts, and K–14 educational agencies. Oversight board members have a fiduciary responsibility to holders of enforceable obligations, as well as to the local agencies that would benefit from property tax distributions from the former redevelopment project area. As discussed in a nearby box, the seven–member board is designed so that no local agency has dominant control.

Oversight Board Will Make Major Decisions. Assembly Bill X1 26 gives the oversight board considerable authority over the former RDA's financial affairs. In addition to approving the successor agency's administrative budget, the oversight board adopts the ROPS—the central document that identifies the financial obligations of the former RDA that the successor agency may pay over the next six months.

The oversight board may determine that a contract between the dissolved RDA and others should be terminated or renegotiated to increase property tax revenues to the affected local agencies. For example, the oversight board may cancel subsequent stages of a project if it finds that early termination would be in the best interest of the local agencies. Similarly, it may (1) direct the successor agency to dispose of assets and properties of the former RDA or transfer them to a local government and (2) terminate existing agreements that do not qualify as enforceable obligations.

Actions of an oversight board do not go into effect for three business days. During this time, DOF may request a review of the oversight board's action. The DOF, in turn, has ten days to approve the oversight board's action or return it to the oversight board for reconsideration.

Successor Housing Agency

Under ABX1 26, the former RDA's housing functions and most of its housing assets are transferred to a successor housing agency. Housing assets that transfer to the successor housing agency include property, rental payments, bond proceeds, lines of credit, certain loan repayments, and other small revenue sources. The unencumbered balance in the former RDA's Low and Moderate Income Housing Fund, however, does not transfer to the successor housing agency. Assembly Bill X1 26 directs the county auditor–controller to distribute the unencumbered balance in the housing fund as property tax proceeds to the affected local taxing entities. (The box below this one provides more information on the Low and Moderate Income Housing Fund.)

Local Agencies Select Oversight Board Members

Most oversight boards are made up of the following:

- Two members appointed by the county board of supervisors, including one member representing the public.

- Two members appointed by the mayor, including one member representing the recognized employee organization with the largest number of former redevelopment agency (RDA) employees.

- One member appointed by the largest special district, by property tax share, within the boundaries of the dissolved RDA.

- One member appointed by the county superintendent of education or county board of education.

- One member appointed by the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges.

The Governor may appoint a representative for any position that has not been filled as of May 15, 2012. The oversight board may begin working as soon as it has a four–member quorum.

Board Member Compensation. Oversight board members do not receive compensation or reimbursement for expenses. No oversight board member may serve on more than five oversight boards simultaneously.

Open Government Requirement. The oversight board is a local entity for purposes of the Ralph M. Brown Act, the California Public Records Act, and the Political Reform Act of 1974. Members are responsible for giving the public access to its hearings and deliberations, disclosing any private economic interests, and disqualifying themselves from participating in decisions in which they have a financial interest.

Future Consolidation of Oversight Boards. All oversight boards within a county are consolidated by July 1, 2016. The membership on the consolidated oversight board is similar to the membership of the initial oversight board, except that the city and special district members are appointed by countywide selection committees.

The Low and Moderate Income Housing Fund

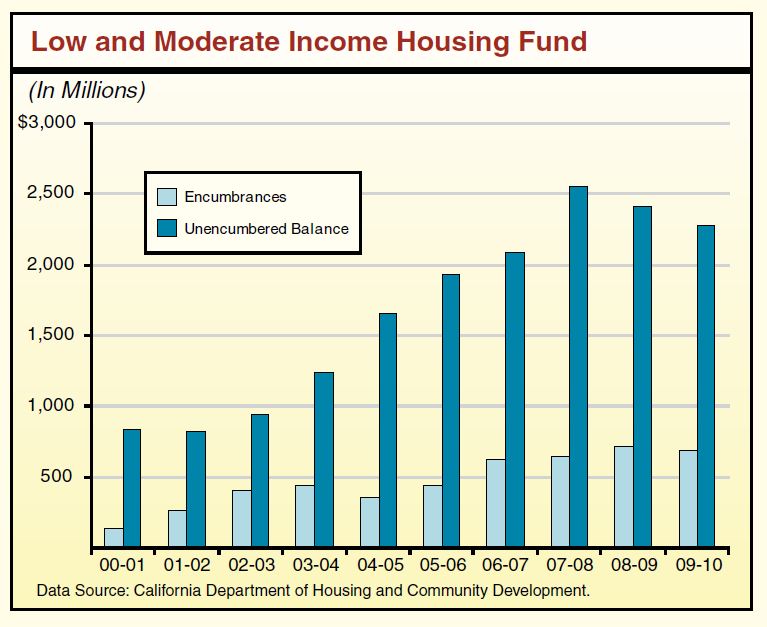

Prior to their dissolution, state law required redevelopment agencies (RDAs) to deposit 20 percent of their annual tax increment revenues into the Low and Moderate Income Housing Fund to provide affordable housing. These housing funds were intended to maintain and increase affordable housing by acquiring property, rehabilitating or constructing buildings, providing subsidies for low– and moderate–income households, or preserving public subsidized housing units at risk of conversion to market rates.

For a variety of reasons, some RDAs retained large balances in their housing fund. As shown in the figure, RDAs' annual reports to the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) show that the unencumbered balances have grown over time to $2.2 billion in 2009–10. We would note, however, that there is some uncertainty about this figure. Redevelopment agencies provide a separate annual report to the State Controller's Office (SCO) that showed an unencumbered balance in the housing fund of about $1.3 billion. This difference occurs because HCD and SCO have separate criteria for distinguishing between encumbered and unencumbered funds. Also, the reports reflect balances for the 2009–10 fiscal year, balances that likely have changed. Some agencies may have accumulated additional balances, while others made large expenditures or transfers for affordable housing purposes or to shield assets from the proposed dissolution process.

Under Chapter 5, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 26, Blumenfield), the unencumbered balance is distributed as local property tax revenue. (The Legislature recently considered legislation that would require unencumbered balances in the housing fund to remain with the successor housing agency for affordable housing activities.) Based on the HCD and SCO reports, the unencumbered balance available for distribution likely is between $1 billion and $2 billon, but the actual balance will depend upon the spending of former RDAs since 2009–10 as well as how successor agencies and oversight boards distinguish between encumbered and unencumbered balances.

As shown in Figure 3, the sponsoring city or county may elect to become the successor housing entity. If the sponsoring community declines this role, then the former redevelopment agency's housing functions and assets are transferred to the local housing authority, or to the state Department of Housing and Community Development if no local housing authority exists. Although ABX1 26 does not specify when sponsoring communities must elect to serve as the successor housing agency, it appears that most cities and counties elected to serve as the successor housing agency at the same time they considered becoming the successor agency. Unlike the successor agency, the successor housing agency's actions related to transferred redevelopment assets are not subject to the review of the oversight board or DOF.

County Auditor–Controller

The county auditor–controller administers each former RDA's Redevelopment Property Tax Trust Fund ("trust fund"). Revenues equal to the amounts that would have been allocated as tax increment are placed into the trust fund for servicing the former RDA's debt obligations, making pass–through payments, and paying certain administrative costs. The auditor then distributes any trust funds not needed for these purposes—as well as any remaining redevelopment cash balances and the proceeds of asset sales—to the local governments in the area as property taxes.

The auditor also is responsible for certifying the successor agency's draft ROPS and auditing each dissolved RDA's assets and liabilities. Assembly Bill X1 26 authorizes county auditor–controllers to recoup their administrative costs associated with these requirements from the trust fund.

State Controller

Assembly Bill X1 26 assigns the SCO responsibility for recouping redevelopment assets inappropriately transferred during the first half of 2011. Specifically, SCO is directed to determine whether the RDA transferred an asset to the city or county that created it (or to another public agency). If the asset has not been contractually committed to a third party, "the Controller shall order the available asset to be returned" to the successor agency. Under this authority, for example, the Controller could order the return of land or buildings transferred from RDA ownership to city ownership during the first half of 2011. For example, many RDAs during 2011 transferred all of their buildings and land to the city. The SCO could order the city to return these assets.

The SCO also plays an oversight role with regard to activities of the county auditor–controller that is similar to the role DOF plays in regard to the oversight board. Specifically, actions of a county auditor–controller do not take effect for three business days. During this time, the SCO may request a review of the county auditor–controller's action. The SCO has ten days to approve the county auditor–controller's action or return it to the auditor–controller for reconsideration.

Assembly Bill X1 26 specifies that SCO may recoup its costs related to these activities from tax increment revenues that previously would have been allocated to the RDA.

Over time, the dissolution of RDAs will increase the amount of general purpose property tax revenues that schools, community colleges, cities, counties, and special districts receive by more than $5 billion annually. In the near term, however, there is uncertainty regarding the amount of property tax revenues that will be available, which local governments will receive the revenues, and the extent to which these increased funds will offset state General Fund education expenses.

This section begins with an example showing—for one fictional RDA—how the county auditor–controller would (1) determine the amount of redevelopment trust funds to distribute to affected taxing agencies and (2) how much additional property taxes each agency would receive. The section then examines these questions from a statewide perspective.

Example: Determining the Amount of Funds to Be Distributed

As shown in Figure 4, the county auditor–controller determined that the former RDA would have received $5 million in tax increment. The RDA had an agreement to pay other local governments $1 million in pass–through payments. The ROPS—prepared by the successor agency and approved by the oversight board—indicates that the former RDA had $20 million in bonded indebtedness and other enforceable obligations, $700,000 of which is due and payable from tax increment.

Figure 4

Example: Funds to Distribute

(In Thousands)

|

Trust Fund

|

|

|

Property taxes formerly called tax increment

|

$5,000

|

|

Pass–through payments

|

–1,000

|

|

Enforceable obligations payable that year

|

–700

|

|

Successor agency administration

|

–250

|

|

County auditor–controller and State Controller administration

|

–50

|

|

Trust Funds to Distribute

|

$3,000

|

|

Cash and Assets

|

|

|

Unencumbered agency cash

|

$200

|

|

Total Funds to Distribute

|

$3,200

|

The successor agency's administrative costs total $250,000 and its cost for reimbursing the county auditor–controller and SCO for their work related to ABX1 26 totals $50,000. The successor agency reports that the dissolved RDA had assets of $200,000 in unencumbered cash (available for distribution immediately) and some land holdings (that will be sold over time).

In the example, the county auditor–controller would have a net of $3 million of residual trust funds and $200,000 in cash to distribute to the local agencies serving the redevelopment project area. This process for calculating the trust fund amount would continue every six months as long as the former RDA has enforceable obligations. After all of the enforceable obligations are paid, the project area will be closed and the property taxes formerly considered tax increment will be distributed to local agencies. These agencies also will receive funds from the liquidation of assets of the former RDA.

What if Trust Fund Costs Are Greater Than Revenues? In the example, there is $3 million to distribute because revenues deposited into the trust fund are greater than its expenses. What would happen if expenses exceeded revenues? In general, this should not be the case because ABX1 26 eliminates a major redevelopment expense—the requirement to set aside 20 percent of tax increment revenues for affordable housing. In addition, the maximum allowable expenditure for successor agency administration is lower than the amount most RDAs spent from tax increment on administration in previous years.

Given these two cost reductions, most trust funds likely will have ample resources to pay their enforceable obligations and administrative costs for the county auditor–controller and SCO. Should the trust fund's resources be insufficient, however, ABX1 26 directs the county auditor–controller to reduce the successor agency's funding for administration and, if necessary, reduce funding for some pass–through payments. (Some pass–through payments—those that must be paid before debt obligations—would not be reduced.) Assembly Bill X1 26 also specifies that the county treasurer may loan funds from the county treasury to ensure prompt payment of enforceable obligations.

Example: Allocating Redevelopment Residual Funds

In our example, $3.2 million is available for distribution to the other local agencies. Assembly Bill X1 26 directs the county auditor–controller to allocate the $200,000 to local agencies proportionately based on each agency's tax shares in the project area. In our fictional example, K–14 districts receive 50 percent of the property tax, counties receive 25 percent, cities receive 15 percent, and special districts receive 10 percent. Figure 5 displays how the $200,000 in cash would be distributed among local agencies.

Figure 5

Example: Distribution of Funds From Cash and Assets

(In Thousands)

|

|

Tax Share

|

Cash and Assets

|

|

K–14 districts

|

50%

|

$100

|

|

County

|

25

|

50

|

|

City

|

15

|

30

|

|

Special districts

|

10

|

20

|

|

Totals

|

100%

|

$200

|

Assembly Bill X1 26 is less clear, however, about the distribution of the $3 million of residual trust funds. The administration and some counties interpret the measure's provisions as requiring these funds to be distributed the same way that cash and funds from redevelopment asset sales are distributed: by tax shares.

In our view, however, the stronger interpretation is that these funds are distributed in a way that takes into account the payments each local agency received from pass–through payments (which, in our example, total $1 million). That is, the $3 million is distributed in a way that ensures that no agency receives more from the trust fund and pass–through payments combined than it would have if funds from both sources ($4 million) were distributed based on tax shares.

Our understanding is that this unusual section of the legislation was drafted in an effort to avoid reallocating property taxes and thus requiring approval by two–thirds of the Legislature under Proposition 1A. While technical in nature, this matter has significant implications for the distribution of revenues—particularly for schools and cities (which receive fairly low pass–through payments) and counties and special districts (which receive comparatively high pass–through payments).

Figure 6 illustrates the fiscal effect of "netting out" pass–through payments. In our example, the county and special districts received pass–through payments of $750,000 and $250,000, respectively. If these payments are excluded from the calculation of distribution from the trust fund, counties and special districts receive $750,000 and $300,000, respectively, from the trust fund. Conversely, if these payments are included in the distribution of the $3 million of trust funds, the county and special district's distribution falls to $250,000 and $150,000, respectively, and the school's and city's distribution increases. In certain cases, it is possible that the county or special district might receive lower total funds under ABX1 26 than it did previously. This would be the case in our fictional RDA, for example, if there were only $1 million of trust funds to distribute. In that case, the county would get 25 percent (its property tax share) of $2 million ($1 million of trust fund revenues and $1 million of pass–through revenues), or $500,000. Using the same approach, the special district would receive 10 percent of $2 million, or $200,000. In effect, some of the funds that otherwise would have been distributed as pass–through payments to the county and special districts are instead distributed to other local agencies. Over time, however, as the enforceable obligations are paid off, trust fund distributions will increase for all local governments.

A nearby box provides additional information about this provision of ABX1 26.

Figure 6

Example: Alternative Calculations for Distributing Redevelopment Trust Fund

(In Thousands)

|

|

Treatment of Pass–Through Payments

|

|

Excluded

|

|

Included

|

|

Pass–Through

|

Trust Fund

|

Totals

|

Pass–Through

|

Trust Fund

|

Totals

|

|

K–14 districts

|

—

|

$1,500

|

$1,500

|

|

—

|

$2,000

|

$2,000

|

|

County

|

$750

|

750

|

1,500

|

|

$750

|

250

|

1,000

|

|

City

|

—

|

450

|

450

|

|

—

|

600

|

600

|

|

Special districts

|

250

|

300

|

550

|

|

250

|

150

|

400

|

|

Totals

|

$1,000

|

$3,000

|

$4,000

|

$1,000

|

$3,000

|

$4,000

|

The Pass–Through Netting Out Provision

What Is the Purpose? Chapter 5, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 26, Blumenfield), allocates the property tax revenues of former redevelopment agencies (RDAs) to K–14 districts, cities, counties, and special districts. Proposition 1A (2004) requires a two–thirds vote of the Legislature whenever it passes a law that alters the share of property tax revenues that cities, counties, and special districts receive.

Our understanding is that ABX1 26, a measure approved by a majority vote of the Legislature, took the approach of allocating all former tax increment funds (except funds pledged to enforceable obligations or required for administration) in a manner that was consistent with the state's existing property tax allocation laws. Under this approach, therefore, agencies that received a higher share of pass–through agreement funds would receive lower allocations from the trust fund.

Why Does Netting Out Affect Some Local Agencies More Than Others? Nearly two–thirds of all pass–through payments stem from pre–1994 negotiations between RDAs and local agencies. For various reasons, counties and special districts were particularly active in this negotiation process. As a result, counties and special districts receive about two–thirds of all pass–through payments. This share of pass–through payments is almost double the share that counties and special districts would receive if pass–through payments were distributed based on tax shares.

Because counties and special districts get a disproportionately large share of pass–through payments, they would get less money from trust fund distributions if these pass–through payments were included in the trust fund calculations. The K–14 districts and cities, in contrast, would get a higher share of redevelopment trust fund distributions.

Statewide Redevelopment Funds Available for Redistribution

Statewide, the amount of residual trust funds available to distribute to local governments will depend on the outcome of calculations—similar to Figure 4—undertaken for each former RDA in the state. These calculations will reflect the unique financial obligations, revenues, and assets of each RDA.

As shown in Figure 7, the administration estimates that $1.8 billion of trust funds will be distributed to local governments annually in 2011–12 and 2012–13. While this estimate is subject to considerable uncertainty, it may be high because the administration understates some significant costs.

Figure 7

Governor's Estimate of Funds Available for Distribution

(In Billions)

|

Trust Fund

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

|

Property taxes formerly called tax increment

|

$5.4

|

$5.4

|

|

Pass–through payments

|

–1.2

|

–1.2

|

|

Enforceable obligations payable during year

|

–2.4

|

–2.4

|

|

Successor agency administration

|

—

|

—

|

|

County auditor–controller and State Controller administration

|

—

|

—

|

|

Trust Funds to Distribute

|

$1.8

|

$1.8

|

|

Cash and Assets

|

|

|

|

Unencumbered agency cash

|

—

|

—

|

|

Total Funds to Distribute

|

$1.8

|

$1.8

|

- Understates Costs to Pay Enforceable Obligations. The administration's estimate assumes enforceable obligations will be paid over 20 years at a 4.6 percent interest rate. Our review of enforceable obligations indicates that some are short–term contracts and loans and others are bonds issued years ago. Amortizing all these obligations over 20 years understates their costs in the near term. We also note that the average interest rate on redevelopment bonds is higher than 4.6 percent. If we adjust the estimate to assume that these debts are paid over 15 years at a 5.6 percent interest rate (the average rate for bonds issued between 2006 and 2010), annual debt costs would increase by $600 million and local governments' distributions would fall by the same amount.

- Assumes a Full Year of Implementation in Current Year. The administration's estimate of 2011–12 savings assumes that RDAs reduced their spending in the first half of the fiscal year. While ABX1 26 prohibited RDAs from paying during this time any obligation not listed on their EOPS, the EOPS that we reviewed appeared to authorize spending that was the same—or higher—than RDA spending in previous years. In addition, county auditor–controllers transferred half of total annual tax increment to RDAs in December or early January and did not reserve funds for deposit to the redevelopment trust fund. Due to these factors, the full fiscal effect of ABX1 26 may not begin until 2012–13. If we adjust the administration's estimate to reflect the half–year implementation of ABX1 26 in the current year, local governments' distributions would fall by at least several hundred millions of dollars.

- Overlooks Administrative Costs. Three parties may fund their dissolution–related administrative costs from property tax revenues that previously were tax increment: the successor agency, the county auditor–controller, and the SCO. While not known, these costs could be in the range of $200 million to $300 million in 2011–12 and 2012–13 and would reduce the funding distributions to local governments.

- Assumes Cooperation Agreements Are Not Paid. The administration's debt cost estimate implicitly assumes that the adopted ROPS will not include cooperation agreements and other non–arm's length transactions between an RDA and its city or county government. Many successor agencies, however, are listing these agreements on their draft ROPS and the statewide redevelopment association is encouraging them to do so to safeguard their right to "challenge the invalidation of these agreements." Under ABX1 26, the oversight boards can remove these costs from a ROPS before adopting it. In addition, DOF has authority over oversight board actions. We note, however, that (1) the court–revised schedule provides little time for the oversight board or DOF to complete the analyses needed to determine whether debts are appropriate for the ROPS and (2) DOF has limited staff working on dissolution matters and oversight boards have no independent staff. Given these factors, it is possible that some adopted ROPS will show higher costs than the administration estimates, reducing the amount of trust fund revenues that will be distributed to local governments in 2011–12 by potentially hundreds of millions of dollars. (This problem could be corrected going forward by removing inappropriate debts from the next adopted ROPS.)

Other elements of the administration's estimate, however, could result in gains that could more than offset the costs identified above. Specifically:

- The administration's estimate does not account for distributions of unencumbered cash transferred from the successor agency. This is notable because many RDAs were planning to participate in the revised redevelopment program authorized by ABX1 27 and reserved significant funds to make the required payments ($1.7 billion) to schools.

- The administration's estimate also does not account for distributions of other redevelopment assets, including the assets that were transferred during the first half of 2011 that the SCO may order returned to the successor agency and the up to $2 billion of unencumbered funds in the affordable housing account. (As mentioned earlier, however, legislation to eliminate the distribution of housing funds is pending in the Legislature.)

- Finally, the administration's estimate does not adjust the distribution of trust funds to account for netting out pass–through payments. While this factor does not affect the administration's estimate of total funds to be distributed, it would provide more funds for K–14 districts and cities and, conversely, less to counties and special districts.

On balance, we think the administration's estimate of the amount of funds to be distributed to local governments in 2011–12 and 2012–13 could be low, possibly by hundreds of millions of dollars. We note, however, that this assessment assumes that the unencumbered RDA cash and assets are available for distribution and that successor agencies reduce their spending to comply with ABX1 26's provision. If some or all of the assets are not distributed or successor agencies do not reduce their spending, the administration's estimate might be overstated by several hundred million to over $2 billion. We expect to have a more refined estimate late this spring after the oversight boards begin their work and we get initial reports from county auditor–controllers.

K–14 District Share of Distribution. Under the administration's interpretation of the funding distribution process, slightly more than half of all net trust funds (about $1 billion of the $1.8 billion) would be distributed to K–14 districts. Under our interpretation, the schools receive more funds, because the trust fund distribution would reflect each agency's property tax share and its pass–through payments. If we modify the administration's estimate to reflect the netting out of pass–through payments, the schools would receive about 80 percent of the distributed funds. This percentage would decline over time (as more funds are distributed outside of the pass–through process) and eventually the K–14 district share would be in the range of 45 percent to 60 percent (the K–14 district share of property taxes in most parts of the state).

Interaction With State K–14 Education Funding

As the local agencies that receive the largest share of revenues raised from the 1 percent property tax rate, K–14 districts will receive the largest share of property tax revenues from the dissolution of RDAs. These funds will grow over time as enforceable obligations are retired and property tax revenues increase. Whether these additional property tax revenues provide additional resources to K–14 education, however, depends on their interaction with the state's education finance system. As noted earlier in the report, K–14 education funding is a shared state–local responsibility. Proposition 98 establishes a guaranteed funding level through a combination of state General Fund appropriations and local property tax revenues. The extent to which the dissolution of redevelopment provides additional resources to K–14 districts or offsets state General Fund costs is uncertain and will depend on three key issues.

- How Much Redevelopment Trust Funds Will Be Distributed and When? As discussed above, the administration's estimate that a total of $1.8 billion will be available to distribute to local governments in 2011–12 and 2012–13 could be off by hundreds of millions to billions of dollars. It is also possible that the administration's estimate will be correct, but that more funds will be distributed in 2011–12 and less in the following year—or the other way around. (This could be the case, for example, if county auditor–controllers need to delay trust fund distributions to local agencies because decisions regarding the payment of some redevelopment obligations are still outstanding at the end of the fiscal year—or if all of the agency's unencumbered cash reserves are distributed in 2011–12 and no cash reserves remain available for distribution in 2012–13.) Finally, the decision regarding whether to take pass–through payments into account in the distribution of redevelopment trust proceeds will affect the share of total trust proceeds that are provided to K–14 districts.

- How Much of These Funds Will Be Distributed to Basic Aid Districts? In a few districts, local property tax revenues exceed these districts' general fund amounts provided through Proposition 98. These districts, commonly referred to as "basic aid" districts, keep the excess local revenue and use it for educational programs and services at their discretion. Any trust funds distributed to these basic aid districts therefore would give them additional revenues to use for educational purposes, but would not offset state General Fund education costs. At this point, we are not able to estimate the amount of trust funds that could be allocated to basic aid districts, but—based on the distribution of tax increment revenues across the state and other factors—do not expect that they would receive more than about 10 percent of the total trust fund revenues provided to K–14 districts.

- Will Proposition 98 Be Rebenched to Reflect These Additional Funds? The state has taken action many times to "rebench" the Proposition 98 guarantee when it made policy changes that shifted local property tax revenues to or away from schools. The net effect of these actions is that the amount of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is not affected by the shifts in local property taxes. The 2011–12 budget assumed that the state would rebench Proposition 98 so that the funds shifted from redevelopment would, in turn, reduce the state's education costs under Proposition 98. Going forward, however, Chapter 7, Statutes of 2011 (SB 70, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) directed the state not to rebench Proposition 98. As a result, the property taxes shifted from redevelopment would not reduce state education funding going forward. The 2012–13 budget plan, however, proposes to change this policy and rebench the minimum guarantee to account for the redevelopment revenues on an ongoing basis. If the Legislature adopts this proposal, therefore, the state would realize education cost savings from the amount of trust funds and assets provided to K–14 districts.

Over the coming months, the Legislature and administration will need to make many decisions regarding implementing redevelopment dissolution. Figure 8 summarizes our major findings and near–term recommendations.

Figure 8

Summary of Major Findings and Near–Term Recommendations

|

— Although ending redevelopment was not the Legislature's goal, the state had few practical alternatives.

|

|

— Ending redevelopment changes the distribution of property tax revenues, not the amount collected.

|

|

— Design of replacement program merits careful consideration.

|

|

— The redevelopment agency unwinding process could yield important civic benefits.

|

- Hold hearings to promote local review over use of the property tax.

|

- Provide funding to train K–14 oversight board members.

|

|

— Alternative use of redevelopment assets raises difficult policy and fiscal issues.

|

|

— Key state and local choices will drive state fiscal effect.

|

|

— Clarifying amendments would help implementation of ABX1 26 (Blumenfield).

|

- Clarify treatment of pass–through payments.

|

|

|

- Clarify authority to take actions to ensure that funds are available to pay bonded indebtedness.

|

Few Practical Alternatives to Ending Redevelopment

Redevelopment in 2011 bore little resemblance to the small, locally financed program the Legislature authorized in 1945. Statewide, the RDAs received more property taxes in 2011 than all of the state's fire, parks, and other special districts combined and, in some areas of the state, more property taxes than the city or county received. Redevelopment also imposed considerable costs on the state's General Fund because the state backfilled K–14 districts for property tax revenues distributed to RDAs. Overall, redevelopment cost the state's General Fund about as much as the University of California or California State University systems, but did not appear to yield commensurate statewide benefits.

The last two decades were marked by considerable tension between RDAs and the state, with the state frequently requiring RDAs to shift money to schools and RDAs challenging these fund shifts in court. For a while, RDAs assumed that Proposition 1A (2004)—a measure that reduced the state's authority over the property tax—would insulate them from future funding shifts. After the courts found that Proposition 1A did not safeguard them from a $1.7 billion 2009 shift and a $350 million 2010 shift, however, RDA advocates (along with other parties) sponsored Proposition 22 to eliminate all state authority over property tax increment.

From the state's standpoint, Proposition 22's restrictions on the state's ability to control redevelopment costs and the ongoing nature of its fiscal difficulties left it with few options. The Governor proposed eliminating redevelopment. The Legislature attempted to offer RDAs an alternative: continue redevelopment, but with significant changes to reduce its state costs. A lawsuit filed by redevelopment program advocates overturned the Legislature's alternative, however, setting in motion dissolution of the redevelopment program statewide.

Over the coming months, the magnitude of administrative, policy, and legal issues associated with unwinding redevelopment inevitably will prompt proposals to slow down or stop the redevelopment dissolution process. Notwithstanding the considerable difficulties associated with ending redevelopment, the state has few practical alternatives. Simply put, the state does not have the ongoing resources to support redevelopment's continuation and the Constitution's many complex provisions prohibit the Legislature from taking actions that could revamp the program into something that the state could afford. For these reasons, we recommend that the Legislature not take actions that slow or stop the dissolution process.

Ending Redevelopment Does Not Change Total State–Local Resources

Redevelopment dissolution does not change the amount of taxes property owners pay or the amount of funds local governments receive from this source. Contrary to some reports, ending redevelopment does not "lose" any funds. Instead, the key fiscal effects of redevelopment dissolution are that:

- More property tax revenues will be distributed to K–14 districts, counties, cities, and special districts—and less to agencies for redevelopment activities. This shift in property tax distributions will be modest in 2011–12, but will increase significantly over time. Within about 20 years, most redevelopment enforceable obligations will be paid and property tax revenues for K–14 districts, counties, cities, and special districts will be about 10 percent to 15 percent higher than they otherwise would have been. These property tax revenues may be used for any local program or local priority.

- The increased K–14 district property taxes will offset state costs for education. Under California law, education is a shared state–local funding responsibility. The increased property taxes for K–14 districts, therefore, will decrease the amount of state resources needed to pay for education.

- There is no requirement that the increased property tax revenues be used for economic development and affordable housing. Under prior law, RDAs annually reserved over $3 billion of tax increment revenues for economic development programs and over $1 billion for affordable housing. (The RDAs spent their remaining funds providing pass–through payments to other local governments.) Although the manner in which some RDAs spent these funds was controversial, economic development and affordable housing programs had a major, dedicated revenue source. Assembly Bill X1 26 does not impose requirements on how local governments spend property taxes that they receive. As a result, it is very likely that the amount of future spending on economic development and affordable housing will be lower than it was previously.

Design of Replacement Program Merits Careful Consideration

As described in this report, the redevelopment program of the 1950s and 1960s changed over the years. During its final decades, in addition to its use for "bricks and mortar" projects, redevelopment funds were used for projects more tangentially related to economic development (such as improving flood control for the region) and to free up local general fund revenues (for example, by paying part of the city manager's salary and other administrative costs). Redevelopment also was a major funding source for affordable housing, often providing money to start a project and additional resources to make it pencil out. Finally, redevelopment helped pay for many other local priorities, including subsidies for sport stadiums, businesses, and the arts.

The end of the redevelopment has prompted interest in developing a replacement program. This interest, in turn, prompts the question: Which elements of the redevelopment program should be replaced? If, for example, the goal is for local governments to have a focused tool for economic development and affordable housing, then five approaches (summarized below) merit consideration. In reviewing the three approaches that provide local financing tools, we note that none has all of the elements that made redevelopment so attractive and valuable to California cities and counties. Specifically, redevelopment provided the sponsoring government with considerable resources and did so without: requiring the approval of local voters or business owners, directly imposing increased costs on local residents or business owners, or requiring additional voter approval prior to issuing debt. As a result, many communities may not be able to raise funds using these tools that are comparable in magnitude to the funds that they raised using redevelopment.

Business Improvement Districts (BIDs). Local governments could rely more extensively on existing law authorizing BID assessments. State law allows local governments to use these assessments for many targeted economic development projects and activities, such as rehabilitating existing structures, providing street improvements and lighting, building parking facilities, marketing, and sponsoring public events. The BID assessments do not require local voter approval, but may not be imposed if a majority of the affected business owners object.

Infrastructure Financing Districts (IFDs). Current law allows cities and counties to form IFDs to receive tax increment financing, provided that (1) every local agency that contributes property tax increment revenue to the IFD consents and (2) two–thirds of local voters approve their formation and any future bond issuances. In recent years, the Legislature has considered measures that would make it easier for local agencies to form these districts and issue debt. In reviewing proposals to revise IFD law, we would urge the Legislature to preserve one key component—the prohibition against redirecting another local agency's property tax revenues without their consent. Maintaining this provision reduces the likelihood that IFD funds are used for projects that do not benefit the broad local community.

Property Tax Debt Override. The Constitution limits property taxes to 1 percent of the value of property. Property taxes may exceed or "override" this limit only to pay for (1) local government debts approved by the voters prior to July 1, 1978 or (2) bonds to buy or improve real property that receive voter approval after July 1, 1978. The Constitution establishes a two–thirds voter approval requirement for local government bonds, but provides a lower voter–approval threshold (55 percent) for local school facility bonds that meet certain conditions. The Legislature could propose an amendment to the Constitution to extend the lower vote threshold to local property tax overrides for economic development and affordable housing purposes. Alternatively, the authority to propose overrides using the lower voter–approval threshold could be limited to local governments that satisfy certain affordable housing objectives.

Regulatory Changes. Local governments interested in promoting economic development and affordable housing could explore regulatory approaches to achieving their goals. For example, local government actions to relax on–sight parking requirements or modify zoning policies can significantly reduce the cost of constructing housing in urban areas. Similarly streamlining project approvals can help promote economic development by reducing developer uncertainty and the costs associated with time delays.

State Housing Assistance. The state administers a variety of programs aimed at reducing the cost that low– and moderate–income individuals and families pay to live in safe and adequate housing. Most notably, (1) the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee administers the federal and state Low–Income Housing Tax Credit Programs that provide hundreds of millions of dollars of tax credits to developers annually to encourage private investment in affordable rental housing, (2) the Department of Housing and Community Development administers state general obligation bond financed programs that provide grants and low interest loans to developers of affordable housing, and (3) the California Housing Finance Agency assists first–time homebuyers and developers of affordable housing by offering them low interest loans financed through the sale of tax–exempt bonds. In considering new housing programs to replace redevelopment, the Legislature may wish to consider whether relying on the state's traditional approach (subsidizing development to increase the supply of affordable housing) or trying a different approach—such as providing housing vouchers to low–income households—might be more effective in providing aid to needy households.

The Unwinding Process Could Yield Important Civic Benefits

While criticized by some as complicated and lacking statewide uniformity, the decentralized oversight board process created by ABX1 26 could be a significant learning experience for everyone in the state. Currently, California's local governments and their residents do not have a forum to discuss and make decisions regarding the use of the local property tax by different local agencies. Instead, property taxes are allocated to each local government pursuant to a statewide formula.

Members of oversight boards will have significant authority and responsibility to compare the merits of continuing a specific redevelopment project against alternative uses for its resources by other local agencies. Oversight board members might decide that a redevelopment project meets local community priorities and continue it, or that the project's funds could be put to better use by the other local agencies in the area and terminate the contract. In many ways, the oversight board process allows local communities to have the first local debate regarding the use of property tax revenues that California has had in decades.

Given the importance of the oversight board, the amount of funds it controls, and its highly expedited schedule, we recommend the Legislature monitor its development and progress closely. Beginning in March, we recommend the Legislature hold hearings regarding the role and operations of oversight boards with the goal of promoting best practices, encouraging information sharing across boards, highlighting public accountability, and learning about unforeseen problems.

One area where we recommend that the Legislature pay particular attention is K–14 districts' participation on oversight boards. While representatives from the County Superintendents of Schools and the community colleges indicate that they plan to participate actively on the oversight boards, we note that the K–14 district representatives may have somewhat less familiarity with the types of projects and financial matters to be discussed. Moreover, absent action by the oversight board to retain separate staff, members of the oversight board will be reliant upon the staff support provided by the successor agency.

Given the significant financial link between the actions of the oversight board and state K–14 education costs, it would be beneficial for the state to offer some training for K–14 oversight board members. The Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT) has significant experience helping California's local educational agencies fulfill their financial and management responsibilities and has previously assisted K–14 districts on redevelopment matters. Given their expertise and relationship with K–14 districts, we recommend the Legislature appropriate funding of up to $1 million to FCMAT to develop this training for interested K–14 oversight board members.

Alternative Use of Assets Raises Difficult Policy and Fiscal Issues

Prior to their dissolution, many RDAs owned considerable assets: land, buildings, and cash reserves. Some RDAs also had large unencumbered balances in their affordable housing funds. Under ABX1 26, successor agencies transfer all RDA assets used for a governmental purpose (such as a park or library) to the local government that provides the service. All other assets (except housing assets) are to be sold on the open market or to a local government "expeditiously and in a manner aimed at maximizing value." Proceeds from asset sales, along with all of the unencumbered cash, are to be distributed to the local agencies as property taxes.

Shortly after passage of ABX1 26, proposals began to surface to separate some of redevelopment assets for use for statewide objectives, such as affordable housing, economic development, and environmental programs. These proposals in turn, raise difficult policy and fiscal questions for the Legislature to consider. Specifically, which level of government should make the decisions over these assets? Should it be a local decision (because RDAs were local agencies) or partly a state decision (because the state indirectly helped pay for these assets through its backfill of K–14 district property taxes)? Should the housing funds remain with agencies that failed to spend them in previous years?

The proposals pose equally difficult fiscal issues. Specifically, ending redevelopment shifts some funds that formerly would have been allocated to RDAs to other local agencies. Many cities relied on RDA funds to pay city expenses and now are experiencing fiscal stress due to the redirection of these resources. Under ABX1 26, some of this fiscal stress would be offset by the city receiving its share of the distributed cash and assets. Reserving some of this cash and assets for statewide objectives, in contrast, would reduce the funds the city would receive from the dissolution of redevelopment.