February 17, 2012

The 2012-13 Budget: Integrating Care for Seniors and Persons With Disabilities

About 1.9 million seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs) are enrolled in California's Medicaid program (known as Medi–Cal), the state–federal program providing medical and long–term care services to low–income persons. The majority of SPDs are also eligible for Medicare, the federal program that provides medical services to qualifying persons over age 65 and certain persons with disabilities. The SPDs who are eligible for both Medi–Cal and Medicare are known as "dual eligibles" and receive services paid for by both programs.

Service Delivery System Is Fragmented. The current financial and program structure for delivering medical and social services to SPDs is fragmented. Medi–Cal pays for most long–term supports and services (LTSS), such as nursing home stays, while Medicare pays for most acute medical services, such as physician and hospital care. In addition, many SPDs receive a portion of their services through Medi–Cal managed care and other services through fee–for–service (FFS). Generally, no single entity has the capacity and financial incentive to coordinate the full range of services SPDs need. This fragmentation often results in poor care coordination, reduced accountability, and increased costs.

Governor Proposes Care Coordination Initiative. To address these issues, the Governor proposes as part of the 2012–13 budget the Care Coordination Initiative to integrate all services, including medical care and LTSS, into managed care for all SPDs (including dual eligibles) statewide beginning in January 2013. At the center of this proposal, the Governor proposes to expand a recently authorized demonstration project (scheduled to begin in January 2013) that will test this new model of integrated care in up to four counties.

Proposal Has Merit, but Raises Significant Implementation Issues. In concept, the Care Coordination Initiative has merit because it attempts to address many of the problems with the currently fragmented system of delivering medical care and LTSS to SPDs. However, for this initiative to be successful, there are several difficult implementation issues that must first be addressed, such as ensuring proper oversight and rate development for managed care plans, maintaining continuity of care for beneficiaries, and determining the level of program control granted to plans. These issues must be addressed in order to ensure the integrated managed care model results in improved health outcomes for SPDs and reduces state costs.

Findings and Recommendations. We find that it is premature to expand the demonstration statewide and make LTSS managed care benefits since the demonstration has not yet been implemented—much less evaluated—and many key implementation details remain to be determined. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor's proposal to expand the demonstration statewide before the results from the demonstration have been properly evaluated, but proceed instead with the four–county demonstration. We make additional recommendations intended to help the state move toward a more integrated system of care delivery for SPDs.

Currently, California's system for providing health and social services to low–income SPDs receiving Medicare and/or Medi–Cal is not coordinated. No single entity is responsible for funding and coordinating services for beneficiaries of these services. This lack of care coordination may lead to SPDs being unnecessarily placed in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs, also referred to as nursing homes) rather than remaining in their own homes—resulting in poor outcomes for recipients and higher costs for the federal and state governments. As part of the 2012–13 budget, the Governor proposes to coordinate care for SPDs through the use of managed care plans. Under the Governor's proposal, these changes would be implemented statewide over a three–year period. The Governor assumes this care coordination would result in savings of $679 million in the budget year, and about $1 billion in future years. In this report, we evaluate the Governor's proposal, describe its potential merits, and list our key implementation concerns. Finally, we make recommendations that encourage the Legislature to analyze the effectiveness of this model of care coordination through a currently authorized demonstration project before implementing it statewide.

This is our initial evaluation of the Governor's proposal. At the time this report was prepared, the administration was still providing information to clarify various aspects of its proposal. Our analysis reflects our understanding of the most up–to–date information made available by the administration. We will revise it as needed to reflect any new information from the administration.

Who Are the Dual Eligibles?

About 1.9 million SPDs are enrolled in California's Medicaid program (known as Medi–Cal), the state–federal program to provide health care services to low–income persons. Of the SPDs enrolled in Medi–Cal, about 1.2 million are also enrolled in Medicare, the federal program that provides healthcare services to qualifying persons aged 65 and over and persons with disabilities. The SPDs who are enrolled in both Medi–Cal and Medicare are known as dual eligibles. The SPDs who are not enrolled in Medicare, also known as Medi–Cal–only SPDs, typically have not met the 24–month disability waiting period or the minimum work requirements necessary to qualify for Medicare.

National studies have found that dual eligibles are more likely than other Medicare beneficiaries in their age group to suffer cognitive impairment from conditions such as Alzheimer's disease or dementia. They are also more likely to require assistance with activities of daily living, such as moving, bathing, dressing, eating, and toileting. They may be unable to fully care for themselves, and may require LTSS in institutional (typically, nursing home) or home and community–based settings.

Dual eligibles often suffer from multiple chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, pulmonary disease, and hypertension at higher rates than Medi–Cal–only beneficiaries. While dual eligibles represent only 15 percent of all Medi–Cal beneficiaries, they account for 27 percent ($2.4 billion) of annual Medi–Cal General Fund spending on medical and LTSS provided outside of managed care. (The vast majority of dual eligibles receive these services outside of managed care.)

Dual Eligibles Are an Expensive Population to Serve. Medi–Cal pays for LTSS for dual eligibles in both institutional and community settings. Nursing home care is by far the greatest cost driver for the dual eligible population. In 2007–08, dual eligibles accounted for nearly 80 percent of $2.1 billion in Medi–Cal General Fund spending on nursing home care. Dual eligibles also make up the majority of spending on home and community–based LTSS. For example, they represent about 85 percent of beneficiaries using the In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, which is administered at the state level by the Department of Social Services (DSS). They may also use case management services administered by the state Department of Aging and many behavioral health services provided by the counties.

The Medi–Cal and Medicare Programs. As we describe in more detail below, Medicare pays for most physician, hospital, and prescription drug (pharmacy) benefits for dual eligibles, with Medi–Cal covering a smaller portion of these costs. However, Medi–Cal pays for some benefits that Medicare does not cover. The two programs provide health care through two main systems: FFS and managed care. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment for each medical service provided. In a managed care system, managed care plans receive a capitated rate in exchange for providing health care coverage to enrollees. Below, we provide an overview of Medicare and Medi–Cal and how the two programs interact.

Medicare is a federal health insurance program overseen by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that provides coverage to eligible beneficiaries at federal expense through FFS and managed care arrangements. Enrollment in Medicare managed care is voluntary.

Most individuals 65 and over are eligible for Medicare. Citizens and permanent residents of the United States are generally eligible if they worked for at least ten years in Medicare–covered employment. People under 65 who have a disability generally are eligible for Medicare after a two–year waiting period. People in need of dialysis or kidney transplants may also be eligible for Medicare. Medicare beneficiaries pay for their benefits through cost–sharing requirements—premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments—which are defined in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Health Insurance Terms—Definitions

|

Premium

|

An amount paid, often in installments, to purchase an insurance policy.

|

|

Deductible

|

An initial specified amount that an enrollee has to pay before the insurer begins to contribute towards medical costs.

|

|

Coinsurance

|

A set percentage of medical costs that enrollees must pay towards the cost of their medical care.

|

|

Copayment

|

A fixed fee that enrollees of a medical insurance plan must pay for their use of specific medical services provided by the plan.

|

Medicare consists of four parts, each with a different set of cost–sharing requirements:

- Part A. This is the hospital insurance program that covers inpatient hospital care, limited care in a SNF, hospice care, and home health care. About 90 percent of beneficiaries do not pay any premium for Part A because they have worked for at least 40 quarters (ten years) in Social Security and/or Medicare–covered employment. Beneficiaries pay a deductible for each hospital visit that lasts up to 60 days. If a hospital visit lasts for more than 60 days, the beneficiary must pay a daily copayment that increases after 90 days in the hospital. Part A coverage for hospital care ends after 150 days. Part A pays for up to 20 days of nursing home care following hospitalization, after which beneficiaries must pay a daily copayment. Part A coverage for nursing home care ends after 100 days.

- Part B. This is optional supplementary medical insurance that covers physician and outpatient hospital care, laboratory tests, medical supplies, and home health care. Part B involves a premium that is deducted from most beneficiaries' Social Security checks. Beneficiaries also pay an annual deductible and 20 percent coinsurance for services covered by Part B. About 95 percent of Part A recipients voluntarily enroll in Part B.

- Part C. These are managed care plans (referred to as Medicare Advantage) that contract with Medicare to provide both Part A and Part B benefits. Enrollment in these plans is voluntary, and members still have to pay the Part B premium. Most plans charge members an additional monthly premium and have other cost–sharing requirements. Some plans also provide Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits (discussed below).

- Part D. This is the outpatient prescription drug benefit that is administered by some Medicare Advantage plans and stand–alone prescription drug plans. Part D is available to everyone enrolled in Part A or Part B. Enrollment in Part D is voluntary for most beneficiaries. A Part D beneficiary pays a monthly premium, an annual deductible, and 25 percent coinsurance until total spending reaches an annual limit. Above this limit, the beneficiary must spend thousands of dollars out of pocket before coverage resumes. This gap in coverage is known as the Part D "donut hole."

About 90 percent of Medicare beneficiaries have supplemental insurance to help pay for their cost–sharing obligations and services not covered by Medicare. This supplemental insurance is known as "Medigap" or "wraparound coverage." As we discuss later in this report, Medi–Cal also provides wraparound coverage for many dual eligibles in California.

In 1965, Title XIX of the federal Social Security Act established Medicaid as a voluntary state health care program. As a joint federal–state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for low–income families with children, seniors, and persons with disabilities. California receives a 50 percent Federal Medical Assistance Percentage—meaning the federal government pays for one–half of most Medi–Cal costs. Most Medi–Cal benefits are administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), although some benefits are administered by other state departments such as DSS.

Medi–Cal provides a wide range of health–related services. Federal law establishes some minimum requirements for state Medicaid programs regarding the types of services offered and who is eligible to receive them. Required services include hospital inpatient and outpatient care, nursing home stays, and doctor visits. California also offers an array of medical services considered optional under federal law, such as coverage of prescription drugs and durable medical equipment. Most beneficiaries have little or no cost sharing for services provided through the Medi–Cal Program.

Medi–Cal Delivery System

There are two main Medi–Cal systems administered by DHCS for the delivery of medical care: FFS and managed care. As of July 2010, approximately 4 million (54 percent) Medi–Cal beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care plans and the remaining 3.4 million (46 percent) were in FFS.

Fee–for–Service. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal payments. This model exists in all counties in California and does not typically provide for the coordination of care for beneficiaries who have several medical providers. The FFS providers are reimbursed for each service after it is delivered.

Managed Care. Under this system, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries residing in certain counties. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the health plan, also known as a plan's "provider network." The health plans are reimbursed on a "capitated" basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Unlike FFS providers, the health plans assume financial risk, in that it may cost them more or less money than the capitated amount paid to them to deliver the necessary care.

Medi–Cal Managed Care Beneficiaries Receive Coordinated Care. Managed care plans typically contract with health care providers, such as physicians and hospitals, to provide services to enrollees. Medi–Cal beneficiaries enrolled in a managed care plan select a primary care physician who provides their health care services on a regular basis. Managed care plans provide assistance to enrollees by coordinating care through referrals to specialists, telephone advice nurses, and customer service centers.

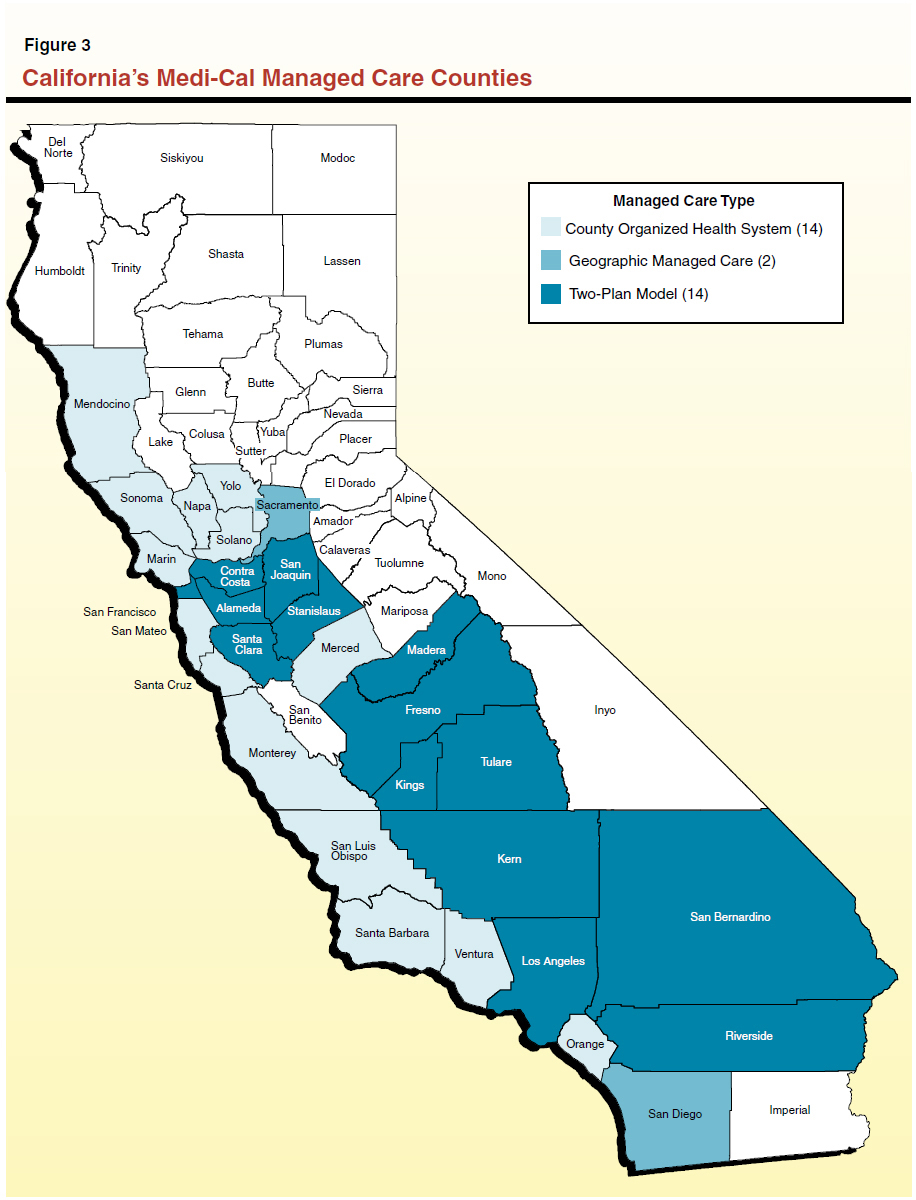

Three Different Models of Medi–Cal Managed Care. Figure 2 identifies the three types of Medi–Cal managed care systems that operate in California. Figure 3 shows that 30 of the state's 58 counties—generally those counties with greater populations—have operating Medi–Cal managed care systems. Currently, Medi–Cal managed care is not available in 28 mostly rural counties, where beneficiaries exclusively receive their medical care from FFS providers.

Figure 2

Three Major Types of Medi–Cal Managed Care Models

- County Organized Health System (COHS). Under this model, there is one health plan run by a public agency and governed by an independent board that includes local representatives.

|

- Geographic Managed Care (GMC). The GMC system allows Medi–Cal beneficiaries to choose to enroll in one of many commercial Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) operating in a county.

|

- Two–Plan Model. The Two–Plan Model consists of counties where the Department of Health Care Services contracts with only two managed care plans. One plan generally must be locally developed and operated. The second plan is a commercial HMO, selected through a competitive bidding process.

|

Managed Care Has Expanded to Include More SPDs. Most beneficiaries enrolled in Medi–Cal managed care are families with children. Until recently, relatively few SPDs were mandatorily enrolled in Medi–Cal managed care (where it was available)—the exception was County Organized Health System (COHS) counties, where nearly all Medi–Cal beneficiaries were mandatorily enrolled, including SPDs. The SPDs in Two–Plan and Geographic Managed Care counties generally had the option of participating in either the FFS or managed care system.

California recently expanded mandatory managed care enrollment for medical services to the majority of Medi–Cal–only SPDs in all Medi–Cal managed care counties as a way to better coordinate their care and to help contain program costs. The year–long transition from FFS to managed care began in June 2011, and approximately 20,000 SPDs are transitioning each month through May 2012. The remaining SPDs, consisting primarily of dual eligibles, continue to receive all Medi–Cal services from the FFS system.

Disproportionate Share of Spending Is FFS. As shown in Figure 4, despite the majority of Medi–Cal beneficiaries (54 percent) being enrolled in managed care in 2010, a disproportionate share of Medi–Cal expenditures (70 percent) is in the FFS system. This is mainly because SPDs, who historically have not been enrolled in managed care, typically have more intensive needs for expensive medical services such as prescription drugs, inpatient hospital care, and long–term care.

The ongoing mandatory enrollment of SPDs into managed care will shift many expenditures from the FFS system to managed care. However, even with this expansion of managed care to include SPDs, a disproportionate share of Medi–Cal spending will likely remain in the FFS system because some of the more costly services are not provided under the managed care system. Instead they are "carved out" of managed care and provided under FFS. We review these services later in this report.

State Oversight of Medi–Cal Managed Care

The DHCS and the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) share oversight responsibilities for most Medi–Cal managed care plans. The DHCS contracts with Medi–Cal managed care plans and oversees compliance with Medi–Cal requirements. Most Medi–Cal managed care plans—except COHS plans—are also required to be licensed by the DMHC. The DMHC oversees the operations and financial condition of managed care plans in California, including most public and private plans, to ensure they comply with the state's Knox–Keene Health Care Service Plan Act ("Knox–Keene"). Some of the major oversight activities performed by the two departments include: (1) resolving beneficiary complaints and grievances, (2) performing quality reviews, (3) ensuring enrollees have access to providers, and (4) monitoring plans for financial solvency. For more information on oversight activities performed by the two departments, see

the box below.

State Oversight of Managed Care Plans

The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) provide oversight of managed care plans.

Mechanisms to Resolve Beneficiary Complaints and Grievances. The DHCS operates the Medi–Cal Managed Care Office of the Ombudsman, which helps resolve beneficiary problems and ensure plans provide all medically necessary covered services. Some of the activities of the Office of the Ombudsman include investigating member complaints about managed care plans, helping with enrollment issues, and educating enrollees on how to navigate the Medi–Cal managed care system.

The DMHC is responsible for enforcing a variety of requirements that generally prohibit managed care plans from denying patients necessary medical care that is a part of coverage. For example, the DMHC operates a Help Center that assists consumers in resolving complaints and problems with health plans. In addition, it operates an Independent Medical Review program that settles disputes between plans and consumers.

Managed Care Plans Undergo Quality Reviews. The DHCS, as part of its oversight of Medi–Cal managed care plans, conducts quality reviews annually to measure health plan performance in regard to the quality of services provided to Medi–Cal beneficiaries. These studies include the collection and annual public reporting of data measuring their performance according to the nationally recognized Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality indicators. The DHCS establishes minimum performance levels for HEDIS indicators. If a health plan's performance falls below an indicator's minimum performance level, it generally submits an improvement plan describing the steps it will take to improve its performance. The DHCS also contracts with private companies to conduct a Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey of patients to obtain information about Medi–Cal members' experiences with their health plans.

Both DMHC and DHCS conduct periodic medical audits of health plans that attempt to evaluate the overall performance of the health plan in providing care to enrollees, part of which includes on–site facility reviews. These audits are meant to review the quality of health care services, the effectiveness of the peer review, procedures for regulating utilization and assuring quality of care, and the overall performance in providing care and meeting the needs of the beneficiaries. Any problems identified through these audits can result in the requirement for a corrective action plan.

Ensuring Enrollees Have Access to Providers. Managed care plans licensed by DMHC are required to comply with various state standards to ensure timely patient access to care. Under this standard, a plan must ensure that its provider network has adequate capacity to offer medical appointments within an appropriate timeframe. For example, plans must ensure enrollees do not wait more than 48 hours for certain urgent care appointments, 10 days for non–urgent primary care appointments, and 15 days for non–urgent appointments with specialists.

Federal and state law further require that Medicaid managed care plans take specific steps to help potential enrollees in Medicaid to understand their health care benefits. For example, health plans must make available free interpretation services for enrollees who are not fluent in English and to publish health plan information in the prevalent non–English language in the area.

Departments Monitor Financial Solvency. A financially unstable health plan may be unable to provide quality and timely care to beneficiaries. Therefore, one of the primary oversight responsibilities for both DHCS and DMHC is to ensure health plans are financially solvent. Both departments perform financial oversight, including reviewing financial statements and monitoring financial solvency. The DHCS is responsible for overseeing Medi–Cal contract requirements that plans meet and maintain financial viability standards. The DMHC also analyzes financial information submitted by managed care plans to ensure plans are financially viable and in compliance with state requirements for managed care plans.

Medi–Cal Provides LTSS

In addition to preventative and acute medical goods and services, Medi–Cal provides a variety of LTSS for SPDs. The LTSS are commonly categorized into two types: (1) institutional care, such as SNFs, and (2) home and community based services (HCBS) aimed at preventing unnecessary hospitalizations and SNF stays and maintaining people in the community. Below, we describe some of the main LTSS that are part of the Medi–Cal Program.

- IHSS. The IHSS program provides in–home care for persons who cannot safely remain in their own homes without such assistance. In order to qualify for IHSS, a recipient must be aged, blind, or disabled and in most cases have income below the level necessary to qualify for the Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program. County social workers perform an assessment to determine the number of hours and types of services to authorize a recipient to receive each month.

- Multi–Purpose Senior Services Program. The Multi–Purpose Senior Services Program (MSSP) provides both social and health care management services for Medi–Cal recipients aged 65 or older who meet the eligibility criteria for a SNF. In addition to the care management service, each MSSP site has funds reserved for the purchase of services necessary to maintain a person in the community after all other private or public programs options have been exhausted.

- Community–Based Adult Services. The Community–Based Adult Services (CBAS) program is an outpatient, facility–based service program that delivers skilled nursing care, social services, therapies, personal care, family and caregiver training and support, meals, and transportation. This program is replacing the Adult Day Health Care program, which is scheduled to be eliminated as a Medi–Cal benefit in March 2012.

- Other Community–Based Waiver Programs. There are several home and community–based programs operating under a waiver of federal requirements that provide various services to recipients who generally meet the level of care required for placement in a SNF. Specifically, these programs include the In–Home Operations, Assisted Living, and Nursing Facility/Acute Hospital waivers. These programs provide assistance with such things as personal care services, nursing assistance, and case management services. In the case of the Assisted Living program, services are provided in a residential care facility for the elderly or in publicly subsidized housing.

- SNFs. The SNFs provide nursing, rehabilitative, and medical care to facility residents. Generally, SNF residents receive their medical care and social services at the facility.

Beneficiaries Often Access Multiple Long–Term Care Programs. Medi–Cal beneficiaries will often access multiple LTSS programs to fully meet their needs. The overlap with IHSS is by far the most significant because it is the largest community–based LTSS program. Figure 5 illustrates some of this participation overlap by program. For example, 1,570 beneficiaries receive both IHSS and Nursing Facility/Acute Hospital waiver services. Although not shown in the figure, we note some beneficiaries may access more than two programs at once. For example, it is possible for an individual to be enrolled in the MSSP program and also have IHSS and CBAS benefits.

Figure 5

Medi–Cal Home and Community–Based Services Caseload Overlapa

|

Program

|

Caseload

|

NF/AH

|

IHO

|

ALW

|

MSSP

|

ADHC

|

IHSS

|

|

IHSS

|

441,699

|

1,570

|

124

|

54

|

9,125

|

22,006

|

|

|

ADHC

|

36,750

|

4

|

—

|

1

|

914

|

|

22,006

|

|

MSSP

|

9,498

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

914

|

9,125

|

|

ALW

|

1,453

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

1

|

54

|

|

IHO

|

143

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

—

|

124

|

|

NF/AH

|

1,995

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

—

|

1,570

|

LTSS Programs Are Carved Out of Managed Care. Several services for SPDs are carved out of Medi–Cal managed care. Funds to provide these services are not included in the capitated rates paid to managed care plans. For example, LTSS are largely provided through FFS, including long–term nursing home stays and HCBS. One exception to this is the newly created CBAS program, which will become a managed care benefit in July 2012.

Many behavioral health services, such as mental health services and substance abuse prevention and treatment, are also carved out of Medi–Cal managed care and provided by the counties.

How Medi–Cal Wraps Around Medicare for Dual Eligibles

Under federal law, Medi–Cal is the payer of last resort for health care. This means that all other third party sources of health coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries, including Medicare, must be exhausted prior to any Medi–Cal reimbursement for health care. When dual eligibles use hospital and physician services, Medicare is the primary payer and Medi–Cal is the secondary payer, providing wraparound coverage for Medicare Part A and Part B cost sharing. For example, when a dual eligible receives a Part B medical service from a physician, the physician first bills Medicare and then sends a crossover claim for the coinsurance amount to Medi–Cal.

Medi–Cal Pays Premiums for Medicare Part A and Part B. Medi–Cal pays Medicare Part B premiums for all dual eligibles and pays Medicare Part A premiums for dual eligibles who do not have enough qualifying quarters of employment to be eligible for premium–free Part A. This arrangement allows the state to pass along a significant portion of dual eligibles' health care expenses to Medicare, which would otherwise have to be paid by Medi–Cal.

Medi–Cal Does Not Pay for Part C. Medi–Cal does not pay Medicare Part C premiums for dual eligibles enrolled in Medicare Advantage managed care plans. However, Medi–Cal pays any deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments that these dual eligibles may be responsible for under their plans.

State Reimburses Medicare for Part D Through "Clawback" Payments. Enrollment in Medicare Part D is mandatory for dual eligibles. Dual eligibles do not face premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, or a donut hole for their Part D coverage. Rather, they pay only $2 or $5 in copayments for covered prescriptions. Medi–Cal does not provide direct wraparound coverage for Part D. However, every month the state pays the federal government 80 percent of the state's savings in Medi–Cal pharmacy from the mandatory enrollment of dual eligibles in Part D. This monthly payment is known as the clawback.

Medi–Cal Pays for Services Not Covered by Medicare. Figure 6 summarizes the division of services covered by Medicare and Medi–Cal for SPDs—a subset of which are dual eligibles. Medicare is the primary payer for hospital, physician, and pharmacy services; Medi–Cal is the secondary payer that often provides wraparound coverage for dual eligibles' cost–sharing requirements. Medi–Cal is the primary payer for most nursing facility care and HCBS.

For SNF Costs, Medi–Cal Picks Up Where Medicare Leaves Off. If a dual eligible requires "post–acute" or "skilled nursing care" for therapy or rehabilitation following hospitalization, then Medicare Part A pays for the first 20 days of the beneficiary's stay in a nursing home. Medi–Cal pays the beneficiary's copayments for the next 80 days. After 100 days in the SNF, the beneficiary's Part A benefit expires, and Medi–Cal begins to cover the cost for the remainder of the stay.

Medicare does not cover nursing home stays that involve "custodial" or "respite care." These are services for beneficiaries who are not undergoing active therapy or rehabilitation programs, but instead need to reside in nursing homes for medical reasons. Medi–Cal pays for dual eligibles in this category, and these services make up the majority of SNF costs for SPDs.

The current financial and program structure for delivering medical and LTSS to SPDs is fragmented. Generally, no single entity has the capacity and financial incentive to coordinate the full range of services SPDs need. This fragmentation often results in poor care coordination, reduced accountability, and increased costs. We note that the problems associated with the fragmented system are widely recognized at the state and federal levels.

Fragmented System Results in Uncoordinated Care

The SPD beneficiaries generally do not have a single entity that coordinates the medical services and LTSS needed to maintain or improve their health status. Many of these beneficiaries must act as their own care coordinator, or attempt to find someone who can assist them in making medical appointments, determining when they need to see a specialist, and identifying HCBS that may help them avoid unnecessary nursing home stays. This arrangement generally does not result in most optimal coordination, thereby contributing to poor health outcomes and increased costs because beneficiaries are less likely to receive preventative medical care and specialized LTSS services.

Fragmented System Encourages Cost Shifting

Medi–Cal and Medicare Differences Encourages Cost Shifting for Dual Eligibles. Medi–Cal and Medicare differ in many ways, including different services, program rules, reimbursement levels, and provider networks. This fragmented structure contributes to a lack of coordination of services for dual eligibles and an incentive for each program to "cost shift." Cost shifting is when one entity or program makes decisions with limited consideration for how those decisions might increase costs for other entities or programs. For example, FFS Medi–Cal pays for the majority of LTSS costs for dual eligibles, but a relatively small portion of the acute medical care costs, such as hospitalizations. Therefore, the state has limited financial incentive to provide additional LTSS that would potentially reduce acute care utilization for dual eligibles, since the savings that would result from avoided hospitalizations would largely accrue to the federal government. This financial misalignment is one of the major barriers to making meaningful improvements in the quality and cost of care being provided to dual eligibles, including the design of alternative delivery systems such as managed care. In our 2004–05 Budget: Perspectives and Issues analysis, "Better Care Reduces Health Care Costs for Aged and Disabled Persons," we cautioned against the mandatory enrollment of dual eligibles in managed care, as long as Medi–Cal and Medicare operate as two separate silos that finance and administer services with little to no coordination between them. Here we make the same observation. Since Medi–Cal managed care plans contract with DHCS while Medicare Advantage plans contract with CMS, enrolling dual eligibles in one or both systems does little to address the lack of coordination between acute and long–term care and the incentives for payers to shift costs. Without a change in the current fiscal incentives, it is unlikely that the benefits from enrollment in managed care would be sufficient to offset the administrative costs and disruptions to care for dual eligibles that could occur when they shift from FFS.

Medi–Cal Managed Care Plans Lack Financial Incentives to Reduce Nursing Home Costs. In Medi–Cal, most medical services provided to managed care enrollees are paid for by the managed care plan, while most LTSS are carved out and are offered almost entirely in the FFS system. Medi–Cal managed care plans have limited financial incentive to prevent an enrollee from entering a nursing home because they are not at financial risk for much of the nursing facility costs. In the Two–Plan and the GMC models, the managed care plan must pay for up to two months of nursing home costs. After the first two months, the beneficiary is disenrolled from managed care and moved into FFS. This allows plans in the Two–Plan and GMC counties to shift costs to FFS, thereby decreasing their fiscal incentive to identify less costly alternatives. Even in COHS counties, where plans must pay for long–term nursing facility stays, they have limited financial incentive to keep a beneficiary out of a nursing home because they receive a higher capitation payment when a beneficiary enters a nursing home rather than stays in the community.

No Fiscal Incentives for Providers to Reduce Hospitalizations and Nursing Home Placements

Many LTSS providers do not receive a fiscal benefit from reducing SNF and hospital costs. For example, the providers of HCBS do not receive any financial benefit if the services they provide decrease nursing home and hospital utilization. This is because to the extent savings are achieved in SNFs and hospitals, they are realized by the state and federal government, not by the program providers. This lack of a fiscal incentive likely leads to an overutilization of SNF care, which increases costs for the state and adversely impacts beneficiaries who prefer to stay in the community.

Further highlighting this issue is the current county share of cost in the IHSS program. Counties fund about 18 percent of IHSS program costs, and are responsible for authorizing the number of hours and type of service recipients receive each month. If those services contribute to the reduction of hospitalizations and nursing home utilization for IHSS recipients, the counties do not fiscally benefit from this. In fact, if nursing home placements decrease due to increases in the number of hours authorized for SPDs receiving IHSS, this results in an increase in county IHSS costs. This is because counties have a share of cost in providing IHSS services, but they do not have a share of cost in the hospitalizations or SNFs. Under this scenario, when hospitalizations and nursing home utilization decreases, the state and federal government save, but counties do not.

Fragmented System Reduces Accountability

In the current structure, the fragmented programs and delivery systems make it difficult to hold a single entity accountable for the quality of care provided to an SPD. For example, it is often unclear which program—Medicare or Medi–Cal—is ultimately responsible for a beneficiary's health outcomes. It is also unclear who is responsible for coordinating care between a primary care physician, a specialist, and an IHSS provider. Although there is fragmentation in the delivery of services to dual eligibles in general, the state has some experience with managed care programs that specialize in coordinating care for a small subset of dual eligibles. For more information on two of these programs, see the nearby box.

Existing Models of Coordinated Care for Dual Eligibles

Program of All Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). This program provides integrated health and social services care for the elderly. To qualify for PACE, a recipient must (1) be over the age of 55, (2) meet the level of care necessary for placement in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or intermediate care facility, (3) live in an area where PACE is available, and (4) be able to safely remain in the community if PACE is provided. The PACE program receives a capitated rate to coordinate and provide long–term social and medical care for recipients, the majority of whom are dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. Generally, this capitated rate is less than what it would cost if the recipient enters a nursing home. This creates the incentive for the PACE plans to provide services in the community rather than in an institutional setting. The PACE site is fully responsible for the cost of all medical and social services each participant requires. Statewide, there are roughly 2,800 PACE participants.

Each PACE site employs an interdisciplinary team that is responsible for conducting assessments, delivering services, and coordinating care. Examples of members of this team are doctors, nurses, social workers, transportation operators, and nutritionists. If not in a SNF or hospital, most PACE recipients receive medical and social services at the PACE site. It is this reliance on a "brick and mortar" site for the delivery of services that could make it challenging to implement the PACE program model for the 1.2 million dual beneficiaries throughout the state. Additionally, not all dual eligibles would meet the eligibility requirements for participation in PACE.

Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D–SNPs). In 2003, the Medicare Modernization Act established Special Needs Plans. These are Medicare Advantage plans aimed at providing coordinated care to certain vulnerable groups of Medicare beneficiaries, and include D–SNPs. As with all Medicare Advantage plans, participation in D–SNPs is voluntary, although some plans are allowed to passively enroll their members.

There are currently 32 D–SNPs in California that enroll nearly 160,000 dual eligibles. These D–SNPs are administered by both local health initiatives and private health systems. The D–SNPs are required to have interdisciplinary care teams that coordinate Medicare services for their members. Despite their focus on dual eligibles, D–SNPs do not administer Medi–Cal benefits such as long–term supports and services. Health systems that operate both Medi–Cal managed care plans and D–SNPs keep these lines of businesses separate, even if they cover the same set of the same beneficiaries.

Federal law requires that new D–SNPs or D–SNPs that are expanding into new service areas contract with state Medicaid agencies. However, these contracts only require that Medi–Cal make wraparound payments for Medicare benefits (allowing D–SNPs to waive nearly all cost–sharing requirements for members) and engage in limited data–sharing with D–SNPs. In their current form, D–SNPs do not truly integrate Medi–Cal and Medicare funding and services for dual eligibles.

As we have described above, the current financial and program structure for providing medical and LTSS to dual eligibles is fragmented. This fragmentation results in a lack of care coordination for the beneficiary, encourages cost shifting, fails to incentivize reducing institutional services, and reduces accountability. To begin to address these issues, there have been recent statutory changes at the federal and state levels. Below, we describe this legislation.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) established two new offices within the CMS—the Federal Coordinated Health Care Office (Duals Office) and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). The goal of the Duals Office is to ensure dual eligibles have full access to seamless, high quality health care, while making the system as cost–effective as possible.

While the Duals Office is more narrowly focused on the population of dual eligibles, the role of the CMMI is more broadly aimed at improving Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children's Health Insurance Program for all Americans. Specifically, the CMMI identifies, tests, and spreads innovative models of payment and service delivery to lower costs and improve the quality of health care for all Americans.

California Receives Federal Grant to Integrate Care for Dual Eligibles. In cooperation with the Duals Office, the CMMI awarded 15 states, including California, with design contracts of up to $1 million to develop new ways to meet the needs of dual eligibles. These states are expected to develop strategies for implementing models of care that fully coordinate primary, acute, behavioral, and LTSS for dual eligibles. This integration of Medicare and Medicaid funding and services is expected to result in savings for the state and federal government. States are expected to work with beneficiaries, their families, and other stakeholders to develop their demonstration proposals. After a federal review of the proposals, CMS will work with states to implement the plans that they decide have the most promise.

Among other things, Chapter 714, Statutes of 2010 (SB 208, Steinberg), authorized the state to implement a coordinated care pilot project for dual eligibles (the "demonstration") in up to four counties. The legislation requires that the demonstration include at least one county that provides Medicaid under a COHS, and at least one county that provides Medicaid services through a Two–Plan model. Specifically, the stated goals of the legislation are as follows:

- Coordinating Medi–Cal benefits, Medicare benefits, or both, across health care settings and improving continuity of acute care, long–term care, and HCBS for dual eligibles.

- Coordinating access to acute and long–term care services for dual eligibles.

- Maximizing the ability of dual eligibles to remain in their own homes and communities with appropriate services and supports in lieu of institutional care.

- Increasing the availability of and access to home and community–based alternatives for dual eligibles.

In selecting the sites for the demonstration, the legislation requires that DHCS consider (1) local support for integrating medical care, long–term care, and HCBS networks and (2) a local stakeholder process that includes health plans, providers, community programs, consumers, and other interested stakeholders in the development, implementation, and continued operation of the demonstration.

The Duals Demonstration Project in California. In order to select the potential sites for the demonstration, the DHCS released a document, known as the request for solutions (RFS), that details the requirements for participating in the demonstration. The final RFS was released on January 27, 2012. Sites interested in participating in the demonstration are asked to respond to the RFS by February 24, 2012. The final RFS was released after several months of public meetings and stakeholder input. The announcement of the selected sites is expected in mid to late March. Once the sites are selected, DHCS will release a draft of the demonstration proposal. After a period of public comment, the proposal will be submitted to the CMS for approval (likely sometime in late April or early May). The demonstration is scheduled to begin in January 2013.

Key Components of the Dual Eligibles Demonstration Project RFS

The purpose of the RFS is to identify the counties best positioned to participate in the demonstration. Although the final RFS is complete, the details of the actual demonstration are pending stakeholder review and federal approval. As noted above, the proposal for the demonstration will be released by DHCS for public comment and federal approval after the sites are selected. The proposal will outline specific programmatic elements and technical requirements of the final demonstration.

Summary of Demonstration Goals. At a high level, the RFS indicates that the purpose of this three–year demonstration is to test how aligning financial incentives around dual eligible beneficiaries can drive streamlined, beneficiary–centered care delivery. The theory is that this type of financial and care coordination can rebalance the current health care system away from avoidable institutionalized services and toward the enhanced provision of HCBS.

Enrollment Process. The RFS states that the dual eligibles in counties selected for the pilot will be passively enrolled in the managed care plans. Passive enrollment means that, unless the beneficiary makes a choice to opt out of the managed care plan, they will be automatically enrolled. Once beneficiaries are enrolled in a plan, pending federal approval, they will be locked in to that plan for a period of six months. After the six months, the beneficiary would be allowed to switch plans or return to FFS. Enrollment of beneficiaries will be phased in. The details of how this phase–in will work will be determined by DHCS after consulting with health plans, stakeholders, beneficiaries, and the federal government.

Benefits Included in the Plan. Sites participating in the demonstration are required to provide access to the full range of health and social services benefits. These include all health benefits, IHSS, CBAS, SNFs, MSSP, and other community–based waiver programs (subject to federal approval). Additionally, plans are required to begin to develop relationships and contracts with local behavioral health providers to work towards full integration of behavioral health benefits, such as mental health and substance abuse programs, by 2015. We note that certain populations, such as certain developmentally disabled recipients and those in the AIDS Healthcare Foundation program, will not be part of the demonstration.

Treatment of the IHSS Benefit. We note that, for the first year, plans will have limited ability to make changes to the IHSS program. During this year, sites will contract with the county to deliver IHSS services. Additionally, sites are directed to work with county social services agencies to develop methods to share information about the care needs of IHSS recipients with the managed care plans. In subsequent years, the RFS asks demonstration applicants to describe how they would suggest expanding their role in the IHSS program. The DHCS will be providing information and guidance on this issue at some point in the future.

Plans Will Receive a Capitated Rate for Services. The federal government gave states two options for integrated financing for this demonstration: the capitated financial alignment model and the managed FFS model. The administration has decided that the demonstration will test the capitated financial alignment model. This means that the sites will receive a capitated rate that combines Medi–Cal and Medicare funds and reflects the integrated delivery of all of the benefits covered under the plan. This rate will be based on baseline spending in the relevant programs after accounting for savings that may result from care coordination. Under the managed FFS model, which will be tested in other states, the states make an up front investment in care coordination and are eligible for a retrospective payment for a share of the resulting Medicare savings.

Demonstration Site Requirements. The RFS describes numerous requirements that sites must meet to be considered for the demonstration. The plans must meet Medicare network adequacy standards for medical services and prescription drugs; LTSS network adequacy standards will be developed by DHCS in consultation with stakeholders. Plans must also have or be working towards having a dual eligible special needs plan, as well as capacity to cover all dual eligibles in each demonstration county and offer some level of care coordination. Other requirements include monitoring and evaluation, recipient notification procedures, and ongoing stakeholder involvement.

Similar to the recent legislation at the federal and state levels, the Governor's budget includes the Care Coordination Initiative, which makes two significant changes to the way health and social services are funded and coordinated for the SPD population (both dual eligibles and Medi–Cal–only SPDs). Specifically, the Care Coordination Initiative proposes to (1) increase the number of SPDs who receive services through managed care by enrolling dual eligibles in managed care plans that integrate Medi–Cal and Medicare services and (2) increase the types of services covered by managed care by making Medi–Cal LTSS managed care benefits. The Governor also proposes a payment deferral to cover the up front costs of this initiative and create budget–year savings. The administration estimates that these proposals will save about $679 million in the budget year and about $1 billion ongoing. The majority of the budget–year savings are related to the payment deferral. The ongoing savings are attributable to: (1) a combination of a reduction in SNF and hospital utilization and (2) an estimate of the savings in Medicare that the federal government would share with the state. Below, we describe our understanding of the main components of the Governor's proposal.

Integrate Medi–Cal and Medicare Services For Dual Eligibles in Managed Care and Make LTSS Managed Care Benefits

Integrate Services for Dual Eligibles in Managed Care. Under the Governor's plan, in three years nearly all of the 1.2 million dual eligibles in California will be enrolled in managed care for both their Medi–Cal and Medicare services. Beginning January 1, 2013, the Governor proposes to expand the number of counties participating in the demonstration authorized under Chapter 714 from up to four counties to up to ten counties. Additionally, after January 1, 2014, the Governor's plan is to further expand the number of counties in the demonstration until it is ultimately active in all 58 counties by 2016. The Governor has a separate proposal to expand managed care to all counties.

Include LTSS in Managed Care. The Governor's budget proposes to include LTSS as managed care plan benefits for all recipients (dual eligibles and Medi–Cal–only SPDs) in all counties where managed care currently exists. It these counties, nearly all LTSS will only be available through managed care by the end of 2013. The LTSS that will be included in managed care are the following:

- IHSS.

- MSSP.

- SNF.

- CBAS.

- Assisted Living Waiver Program.

- In–Home Operations Waiver and Nursing Facility Acute Hospital Waiver.

Payment Deferral Proposed as Part of Care Coordination Initiative. The Governor proposes to defer payments to managed care plans and FFS providers by a week or two to offset some of the up front costs associated with the Care Coordination Initiative. The Governor also proposes statutory language that would not allow DHCS to defer these payments unless the Governor's Care Coordination Initiative proposal is enacted.

Proposal May Change Some Conditions of the Demonstration. Along with increasing the number of sites participating in the demonstration and making LTSS managed care benefits, the Governor proposes other statutory changes related to consumer notification requirements, stakeholder processes, and managed care plan requirements. At the time this analysis was prepared, the administration had stated that there was additional proposed legislation yet to come related to the implementation of this proposal.

Estimated Implementation Time Line. Based on our understanding of the Governor's proposal, the Care Coordination Initiative will integrate two sets of benefits into managed care: (1) LTSS for all SPDs and (2) Medicare benefits for dual eligibles. As these benefits are integrated into managed care, beneficiaries will be mandatorily enrolled for their Medi–Cal LTSS benefits and passively enrolled for their Medicare benefits. The LTSS and Medicare benefits will not be integrated into managed care in all 58 counties at the same time. Moreover, once integration begins in a county, integration of LTSS and Medicare could begin at different times in 48 counties. It is also important to note that, as discussed above, Medi–Cal managed care currently exists in 30 counties, while the remaining 28 counties are FFS. Below we provide a simplified implementation time line for three separate groups of counties.

- Ten Managed Care Counties Selected to Integrate All Benefits in Year 1. Ten counties that currently have managed care will be selected by DHCS to integrate LTSS and Medicare benefits into managed care beginning January 1, 2013. In Year 1, LTSS will become managed care benefits for SPDs (dual eligibles and Medi–Cal–onlys) in these ten counties. In the same year, dual eligibles in these counties will have their Medicare benefits integrated into managed care.

- 20 Remaining Managed Care Counties to Integrate All Benefits in Two Phases. In the remaining 20 managed care counties, LTSS will become managed care benefits for all SPDs in Year 1 just like the other ten counties. Unlike the other ten counties where Medicare benefits are also integrated in Year 1, in the remaining 20 managed care counties Medicare benefits for dual eligibles will not be integrated into managed care until Years 2 and 3.

- 28 Counties Become Managed Care Counties and Integrate Benefits. Beginning June 2013, the Governor separately proposes to expand managed care into 28 counties that currently only provide services through the FFS system. In these counties, LTSS will become managed care benefits for SPDs and dual eligibles will have their Medicare benefits integrated into managed care by January 2016. The specific time line for enrolling beneficiaries and phasing benefits into managed care in these counties is uncertain because the administration has not yet begun its proposed expansion of managed care into these counties.

We note that, passively enrolled dual eligibles will have the ability to opt out of managed care for their Medicare benefits. The time line suggests that by January 2016, SPDs statewide will be mandatorily enrolled in managed care for LTSS. Additionally, all dual eligibles statewide who do not opt out will be enrolled in managed care for their Medicare benefits.

Proposal Has Managed Care Tax Implications. The Governor separately proposes to eliminate the sunset date for the tax on Medi–Cal managed care organizations (MCO tax). The MCO tax extends the state's Gross Premiums Tax to Medi–Cal managed care plans. The revenue from the MCO tax is used to leverage additional federal monies and offset General Fund costs in the Healthy Families Program. The administration estimates that the Care Coordination Initiative would increase revenue for Medi–Cal managed care plans by about $13 billion annually within the first couple of years and thereby significantly increase revenues generated through the MCO tax.

Administration Assumes Savings From Implementation

The administration has presented the Care Coordination Initiative as a proposal with two distinct yet closely related components. For 2012–13, the Governor's budget assumes General Fund savings of $42 million from implementing the first component to integrate Medicare and Medi–Cal benefits for dual eligibles under managed care. The administration projects that this component of the proposal will also achieve out–year savings of $400 million to $650 million annually.

The second component of the Care Coordination Initiative is to make Medi–Cal LTSS available only under managed care. According to the administration's analysis, this would achieve out–year savings of $400 million to $550 million annually. However, during the start of the LTSS transition from FFS to managed care in January 2013, Medi–Cal would have to make retroactive payments for LTSS provided to SPDs under FFS. At the same time, Medi–Cal would also make up front capitated payments to managed care plans to begin providing LTSS for their SPD members. The administration estimates that these overlapping payments create a budget–year cost of $166 million, and proposes to cover this cost by making the aforementioned payment deferral. For 2012–13, the Governor's budget assumes General Fund savings of $580 million from LTSS integration, by subtracting the $166 million cost of overlapping FFS payments from payment deferral savings of $746 million. In other words, if not for the payment deferral, LTSS integration would otherwise result in a budget–year cost, not savings.

The administration projects ongoing savings of about $1 billion combined from implementing both components of the Care Coordination Initiative. Below, we summarize the administration's assumptions behind how each of these components would generate savings.

Integrate Medi–Cal and Medicare Benefits of Dual Eligibles in Managed Care. Under this component of the Governor's proposal, DHCS and CMS will enter into a three–way contract with managed care plans to enroll dual eligibles in each county. Both Medicare and Medi–Cal will contribute toward a blended capitated payment to each plan, in exchange for that plan administering and paying for all necessary Medicare and Medi–Cal services for its dual eligible members. The blended rates will assume that dual eligibles use less hospital inpatient and skilled nursing care under managed care than under FFS. The rates will also assume that dual eligibles use more physician services and prescription drugs under managed care. This assumption reflects improvements in preventative care and disease management that help dual eligibles avoid hospital and nursing home admissions. Both assumptions are based on rate development methods for managed care plans enrolling Medi–Cal–only SPDs. The final blended rate to plans enrolling dual eligibles will be lower than the total amount that Medicare and Medi–Cal would expect to pay under FFS.

The Governor's budget assumes that the state will receive 50 percent of any savings from implementing the proposal that would otherwise accrue to Medicare. It is our current understanding that the state's share of Medicare savings will be prospectively built into the blended capitated rate.

Include LTSS in Managed Care. Under this component of the Governor's proposal, DHCS will make capitated payments to Medi–Cal managed care plans for providing LTSS to all SPD beneficiaries in each county. The rates will include the current cost of the IHSS program, and assume that plans will prevent and substitute nursing home stays for their members with IHSS and other HCBS. Rates will also assume that SPDs use fewer hospital inpatient services once LTSS are incorporated into managed care. These assumptions are based on other states' experiences with moving their Medicaid SPD populations from FFS to managed care.

The Governor's budget proposes significant reform to the delivery and financing of services to a high–cost, high–need segment of the Medi–Cal population. While we have a variety of concerns about the Governor's proposal, we support the general concept of aligning incentives and coordinating services to improve health outcomes, reduce program costs, and increase accountability. As mentioned above, a relatively small portion of the Medi–Cal population represents a disproportionate share of overall costs—much of which occur through hospitalizations and nursing home stays.

Below, we discuss some of the conceptual merits, implementation issues, and key concerns associated with the Governor's approach in more detail. We note that many of the conceptual merits and implementation issues are also relevant to the implementation of the demonstration authorized in Chapter 714.

Managed Care Has Potential to Improve Outcomes and Reduce Costs

The Governor proposes to expand the existing Medi–Cal managed care structure as the state's long–term strategy for delivery system reform. Currently, the fragmented system results in various entities lacking either the capacity or financial incentive to deliver and coordinate services in a way that prevents systemwide inefficiencies and avoidable costs. Under the proposal, managed care plans would have financial risk for the delivery of nearly all services to Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Once the managed care plans have this additional financial risk, the plans could use a variety of tools to contain costs—many of which could simultaneously result in improved health outcomes through better coordination of care and a focus on prevention.

Managed Care Plans May Be Able to Better Coordinate Services. Managed care plans have significant experience coordinating medical services for enrollees. However, as discussed earlier, SPDs, including dual eligibles, require a wide range of services and supports from both medical and social service systems. The integration of LTSS, such as IHSS, into managed care has the potential to improve the level of information sharing and coordination between complementary medical and social services.

Managed Care Plans Would Have Greater Incentive to Reduce Unnecessary Institutional Costs. Managed care plans would have greater financial incentive to prevent unnecessary utilization of high–cost services. For example, managed care plans may be able to identify and coordinate the services a beneficiary needs—both medical services and social services—to avoid unnecessary nursing home stays. Part of this strategy for reducing expensive nursing home stays could be to identify ways to augment, coordinate, or improve HCBS in a way that prevents an individual from entering a nursing home. Another strategy could be to coordinate supports available to the beneficiary when being discharged from a hospital.

Medi–Cal and Medicare Would Have Less Incentive to Shift Costs. Funding for Medi–Cal and Medicare would be blended into a single capitation rate to the managed care plans and the state would receive an up front share of the Medicare savings. This arrangement would likely result in fewer opportunities for the two programs to shift costs to each other. Instead, managed care plans would have the financial incentive to provide services in the most cost–effective manner.

Could Lead to Greater Accountability for Outcomes

Integrating LTSS into Medi–Cal managed care offers opportunities for improved accountability. Currently, it is often difficult to determine who is accountable for coordinating care and ensuring positive health outcomes for SPDs. The Governor's proposal establishes the state as the level of government ultimately responsible for ensuring high–quality services are available to dual eligibles. In addition, by moving nearly all Medi–Cal services into the managed care delivery system, managed care plans become the primary entities responsible for coordinating services for all Medi–Cal beneficiaries. The state would be able to focus its oversight and monitoring efforts on managed care plans to ensure beneficiaries are receiving the services they need. For example, the state could hold a plan accountable if its enrollees are not receiving the services they need to stay out of a nursing home.

Takes Advantage of Opportunity for Shared Medicare Savings

While the details of discussions between DHCS and the federal CMS are unknown, any indication that the federal government is willing to share a portion of its savings is an important step toward system reform. The state would have a strong fiscal incentive to identify more efficient models of care for dual eligibles.

Aligns State With Federal Policy

As we described earlier, the ACA created offices at the federal level that are focused on improving care coordination for dual eligibles. In this regard, the goals of the demonstration and the Governor's budget proposal are both in line with these federal priorities. Since the federal government is sending the message that care coordination for the dual eligibles is a policy goal it would like to pursue, it makes sense for California to begin moving in the direction of developing a system of coordinated care for the dual eligible population.

Although we have noted several aspects of the Governor's proposal that have merit in concept, there are numerous details crucial to a successful implementation. Below, we describe some of the key implementation issues that the Legislature should consider when evaluating the Governor's proposal.

Strong Oversight of Health Plans Is Essential

Despite the potential benefits of expanding Medi–Cal managed care to include new populations and services, if effective oversight and monitoring systems are not in place, managed care may not improve access, quality, and coordination of care. For example, in an attempt to reduce costs, a managed care plan could inappropriately restrict access to services. There are many challenges to ensuring effective oversight under the Governor's proposal.

Additional Risk Requires Strong Financial Solvency Protections. Transferring significant financial risk to managed care plans in a relatively short time period has the potential to result in adverse consequences. A recent report by the State Auditor highlighted some problems associated with the existing oversight of some Medi–Cal managed care plans, including failure to conduct prompt financial reviews. Under the Governor's proposal, managed care plans would cover a costly new population and set of services. The costs for this population and the services they receive can vary widely—dramatically increasing the degree of financial risk assumed by many managed care plans. For example, the annual FFS cost of an individual in a SNF is over $65,000 while the annual cost for someone with an average number of IHSS hours is closer to $13,000. A managed care plan must have adequate financial reserves to absorb fluctuations in utilization of services for SPDs. If they do not, beneficiaries are at risk of not receiving the care that they need because plans do not have enough money to pay for the services. Before it transfers such high levels of financial risk, the state must ensure financial solvency is adequately monitored in a timely, coordinated matter.

Quality Oversight and Monitoring Need Further Development. We are also concerned that state monitoring of quality of care being provided by managed care plans needs further development. For example, the recent report from the State Auditor also raised concerns about the time lines of medical audits performed by DHCS and DMHC. The report recommended that DHCS take additional steps to ensure it performs annual medical audits of managed care plans.

In addition, the state is in the early stages of implementing a system for monitoring care provided to Medi–Cal–only SPDs recently transitioned into managed care. The DHCS currently contracts with outside entities to review the quality of medical services provided to managed care enrollees, who are primarily families with children. However, these measures are largely geared toward primary care and preventative services. In September 2011, DHCS released the measurements that will be used to monitor quality of care for SPDs in 2012. Once implemented, it will take time to evaluate the effectiveness of the new quality monitoring for this group.

Finally, reliable standards for measuring the quality of LTSS provided through managed care are not available. While there has been a significant level of activity at both the federal and state level related to quality measurement, most of the activity has been around medical care, not LTSS. Few LTSS quality measurements have been tested on a large scale and few, if any, national quality standards exist.

Network Adequacy Measures Are Not Well Developed. A managed care plan's ability to offer an adequate network of providers is a significant concern associated with the Governor's proposal. In the absence of a robust provider network, this very fragile population may not receive the specialized services they need in a timely manner. The number and types of providers needed to care for this population is much different than those needed for relatively healthy children and nondisabled adults. In recognition of this issue, the department entered into an interagency agreement with DMHC to monitor provider networks during the transition of Medi–Cal–only SPDs, but the effectiveness of this monitoring effort is unknown. The RFS indicates that federal Medicare Advantage standards will be used to monitor network adequacy for dual eligibles, but it is unclear who will be responsible for monitoring and enforcing these standards.

Furthermore, the administration has not clarified how it will monitor network adequacy for LTSS. Neither DMHC nor DHCS uses standards to monitor network adequacy for many LTSS. These standards still need to be developed and implemented.

Beneficiary Education and Protections Must Be Sufficient. There should be adequate resources available to help SPDs resolve grievances and assist them in navigating an unfamiliar managed care system. The existing state managed care oversight structure provides Medi–Cal managed care enrollees with a variety of tools to help them obtain the covered medical services that they need, including the DMHC Help Center, the Independent Medical Review process, and the DHCS Office of the Ombudsman. However, the Governor's proposal would increase the number of enrollees and types of services covered through managed care, thereby creating additional workload for state oversight entities. For example under the Governor's proposal, many of the new managed care enrollees may have questions because they have limited experience obtaining services through managed care plans. In addition, beneficiaries may have grievances related to services that are not currently provided through managed care, such as nursing home stays and IHSS.

Effective Rate Development Is Critical to Success

A sound managed care rate–setting system is essential for a successful expansion of managed care. Inappropriate rates could result in quality and access problems for enrollees or additional state costs. Rates paid to managed care plans should generally reflect the costs of providing care to their enrollees—enough to ensure plans can deliver quality services to beneficiaries, while ensuring the state is not overpaying. Some of our concerns about managed care rates under the Governor's proposal are described in more detail below.

Reliable, Complete Data Needed to Develop Rates. A sound rate depends on reliable data that can be used to assess the overall financial risk to plans and set the rates in an actuarially sound manner. The DHCS may need to collect several key pieces of data that are not used in the existing managed care rate–setting process. For example, the data collected by Medicare and various LTSS, such as IHSS, are not frequently shared with the DHCS or managed care plans.

Rates May Need to Account for a Wide Range of Beneficiary Needs. Both Medi–Cal and Medicare adjust managed care payments by medical diagnoses, which are used to estimate the health characteristics of the population. These may be a reasonable predictor of acute health care costs, but they likely do not accurately reflect a person's full–service needs, including LTSS. The need for LTSS is closely related to the functional status of a beneficiary, which is often measured by his or her ability to complete daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, and eating. A couple of recent reports have suggested that a risk adjustment for this population should utilize medical diagnoses data and information on functional status to ensure a rate–setting process that adequately accounts for all enrollee needs, including both social and medical services. The process of incorporating data on functional status into rates is not established and access to data may be problematic.

Reducing Managed Care Rates to Achieve Short–Term Savings Has Risks. As discussed in more detail below, the administration proposes to establish rates that rely on data from other states where managed care reduced hospital inpatient and nursing home utilization. At this point, we are unsure whether it is reasonable to assume the results from these states would be applicable to California. If the situations are not comparable, then the rates may not adequately reflect California costs. Rates that are too high would result in the loss of potential state savings. On the other hand, inadequate rates increase the risk that plans become financially insolvent. In that event, plans might not be able to pay for necessary services for beneficiaries.

Different Financial Models Share Risk. Plans have varying levels of experience with high–cost populations and expensive LTSS. We note that there are options to implement different risk–sharing models such as "risk corridors" that reduce the potential for adverse consequences. Under a risk corridor arrangement, the managed care plan would have financial risk for all the same services and enrollees, but the state would share in a portion of any unanticipated savings or costs. As managed care plans get more experience working with some of the LTSS programs and get to know the specific needs of the dual eligible population, the state could adjust the rate setting methodology to give health plans a greater share of financial risk for the population.

It Will Take Time for Managed Care Plans to Understand LTSS

As previously described, managed care plans currently have experience managing and administering medical services for beneficiaries. However, because they generally do not currently cover LTSS, managed care plans have limited knowledge of how social services programs such as IHSS and MSSP operate. Not only are plans unfamiliar with the management of community–based social services, they receive limited information related to the utilization of these services by their members. It will take time for managed care plans to develop relationships with local providers of these programs, and to understand how these programs can be best utilized to reduce hospital and nursing home costs. If plans are not familiar with the potential benefits of these programs, they may not understand how they could use these services to reduce nursing home and hospital costs. Even once plans begin to understand these services, it will take time to establish relationships with LTSS providers.

It is important to note that some managed care plans have been interested for many years in the integration of LTSS into their plans. As a result, they have made some formal and informal arrangements with managed care plans for the provision of LTSS. In these cases, the plans may be better positioned to cover these benefits more quickly.

Consider the Level of Program Utilization and Control Granted to Plans

One major implementation issue that has not been clarified by the administration is the level to which managed care plans will have the ability to control LTSS utilization, administration, and scope of benefits. While managed care plans would like to have flexibility to change programs in ways that they believe will maximize their ability to manage their risk and provide for beneficiaries, depending on the level of flexibility granted to the plans, key components of the programs could change. Prior to the integration of LTSS within managed care, it must first be decided which parts of the programs are fundamental and necessary to preserve, and which components the managed care plans should have the ability to control. These decisions will likely be different depending upon which programs are being considered, but should be determined before implementation.