The Governor proposes to reduce funding for the CalWORKs program and state–subsidized child care programs. Under his budget plan, these programs would be reduced a total of $1.4 billion or about 20 percent in 2012–13 compared to what current law otherwise would require. These savings would be achieved by imposing stricter limits on which families are eligible to receive which types of services, as well as lowering state payments for CalWORKs recipients and child care providers. Additionally, the Governor's proposal would make major changes to the way the state administers both welfare–to–work and child care services.

In this report, we describe and analyze the Governor's proposals related to the CalWORKs program and then turn to a similar discussion of the proposed changes to child care programs. We conclude by providing the Legislature with illustrative packages of ways to achieve savings in these two areas using different approaches than the Governor.

The Governor's budget proposes a major redesign of the CalWORKs program that results in significant General Fund reductions. These reductions are achieved primarily through reduced cash grants and shortened time limits for welfare–to–work services. In this section of the report, we provide background on the CalWORKs program, describe and analyze the Governor's CalWORKs proposals, and discuss alternative options the Legislature may wish to consider for achieving CalWORKs savings.

In 1996, federal welfare reform legislation established the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. In response, California created the CalWORKs program. CalWORKs provides cash grants and welfare–to–work services for families whose income is inadequate to meet their basic needs. Although the CalWORKs program is authorized in state law and funded through the Department of Social Services (DSS), the program is primarily administered by CWDs. The current CalWORKs program is expected to serve about 586,000 cases in 2012–13.

Income Eligibility Requirements and Program Benefits. To be financially eligible to enter the CalWORKs program, a family's monthly income must be below a specified level, known as the Minimum Basic Standard of Adequate Care. This income cap varies by family size. For a family of three, the monthly income cap is $1,168. Maximum monthly cash grants—known as the maximum aid payment (MAP)—vary by family size and place of residence. The current MAP for a family of three living in a high–cost county is $638 per month. Once on cash aid, a family may remain eligible for aid despite having additional earnings, as a portion of earned income (the first $112 dollars plus 50 percent of additional income) is not counted when determining a family's cash grant. This amount of disregarded income is known as the "earned income disregard." A family's aid is discontinued when its earned income (minus the disregard) exceeds its cash grant. In addition to cash assistance, CalWORKs families receive CalFresh (Food Stamps) benefits. Many CalWORKs families also are eligible for welfare–to–work services, including job search assistance, training, barrier removal (such as adult basic education and mental health, substance abuse, and domestic abuse services), and subsidized child care.

Three Sources of Funding Support the CalWORKs Program. The CalWORKs program is funded by a combination of federal, state, and local funds. Federal funding is provided through an annual $3.7 billion TANF block grant. While a majority of the TANF block grant is used to fund the CalWORKs program, TANF funds can be used for any activities that meet the broad purposes of the TANF program (see Figure 1). To receive the full TANF block grant, California must contribute at least $2.9 billion from various nonfederal sources to meet a maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirement. Although the MOE requirement is primarily met through state and county spending on CalWORKs, some state expenditures in other programs (such as subsidized child care) also count toward satisfying the requirement. County costs to administer the CalWORKs program, as well as provide employment services and child care to CalWORKs recipients, are funded through an annual block grant (known as the single allocation) provided by the state. In addition, as a result of the 2011–12 realignment, $1.1 billion in local funds were redirected to cover a portion of CalWORKs cash grant costs.

Figure 1

The Four Purposes of TANF

|

|

- Provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives.

|

- End the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage.

|

- Prevent and reduce the incidence of out–of–wedlock pregnancies and establish annual numerical goals for preventing and reducing the incidence of these pregnancies.

|

- Encourage the formation and maintenance of two–parent families.

|

Federal Law Requires State to Meet Work Participation Rate (WPR). Federal law generally requires states to ensure that at least 50 percent of able–bodied TANF recipients participate in certain categories of work activities for a specified number of hours. Federal law also provides states with credits (known as caseload reduction credits) that reduce this obligation if they reduce their welfare caseloads. California currently does not receive any caseload reduction credits. Failure to meet the federal WPR may result in substantial penalties on the state (starting at up to 5 percent reduction to its TANF block grant and increasing 2 percent each year). California has failed to meet its WPR since 2007 and has been notified that it will be assessed penalties of $47 million and $113 million, for 2008 and 2009 respectively. However, the state is appealing these penalties and, to date, no reduction in TANF funding has been enforced. For the foreseeable future, it is estimated that California's WPR will be in the range of 25 percent to 30 percent—substantially below the federal 50 percent WPR.

Federal and State Work Requirements Differ in Two Notable Ways. As shown in Figure 2, California's statutory work requirements differ in two notable ways from federal work requirements.

- Allowable Activities. Federal and state law designate specific activities as "core" and "noncore." Although federal and state core activities generally are the same, some state noncore activities are less restrictive than the federally allowable activities. Unlike federal law, state law also allows some noncore activities to count as core activities in special cases. One area in which state law is less restrictive relates to allowable education activities. Under state law, an allowable activity is any type of higher education (not limited to vocational education) typically up to 24 months. By comparison, federal law allows recipients to count only 12 months of vocational education toward meeting program requirements. Another notable difference is that current state law has a less restrictive time line for mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence treatment than federal law.

- Required Hours. California requires all single parents to participate in work activities for 32 hours a week whereas federal law requires 20 hours for single parents with children under six and 30 hours for single parents with older children. For two–parent families, federal law requires 30 hours of core work activities whereas state law requires only 20 hours.

Figure 2

Comparison of Federal and State Work Requirements

|

Number of Hours Required Per Week

|

|

Family Type

|

|

Federal

|

|

State

|

|

|

Total Hours

|

Core Hours

|

Total Hours

|

Core Hours

|

|

Single–parent with child under six

|

|

20

|

20

|

|

32

|

20

|

|

Single–parent with older children

|

|

30

|

20

|

|

32

|

20

|

|

Two–parenta

|

|

35

|

30

|

|

35

|

20

|

|

Allowable Activities

|

|

Core

|

|

Non–Core

|

|

Federal and State

|

|

Federal

|

|

State

|

- Unsubsidized employment.

- Subsidized employment.

- Work experience.

- Community service.

- Vocational education (up to 12 months).

- On–the–job training.

- Job search and job readiness training (six weeks per year, can include mental health and substance abuse treatment).

- Providing child care to a community service program participant.

|

|

- Job skills training directly related to employment.

- Education directly related to employment.

- Satisfactory attendance at a secondary school or course leading to a certificate of GED.

|

|

- All activities listed under federal.b

- Mental health, substance abuse, and domestic abuse services beyond six weeks.

- Any higher education (typically up to 24 months).b

- Other activities necessary to assist in obtaining employment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Program Has Sanctions and Time Limits. If a family fails to meet its work requirement, it may be subject to a sanction. The sanction reduces the amount of the family's cash grant by the amount attributable to the adult (usually about $120 a month). Generally, able–bodied (also known as work–eligible) adults are limited to four years of cash assistance, while children are not subject to time limits. If an adult reaches the four–year time limit, the family's grant is reduced by the amount attributable to the adult and the children continue to receive aid in a program known informally as the "safety net." Families in which only the children are aided because the parent is not work eligible (such as individuals who are undocumented or receiving Supplemental Security Income [SSI]) are known as "child–only" cases. There are currently about 232,000 child–only cases and 72,000 safety–net cases in the CalWORKs program.

Recent Reductions to the CalWORKs Program. During the past three years, the state has made significant reductions to the CalWORKs program, including: lowering cash grants for families (total of a 12 percent reduction), reducing employment services and child care funding, shortening the adult time limit for assistance from 60 months to 48 months, reducing the earned income disregard, suspending intensive case management for pregnant and parenting teens, and reducing funding for substance abuse and mental health treatment. In the absence of these changes, which resulted in ongoing CalWORKs reductions of around $780 million, expenditures in the CalWORKs program would have grown significantly due to increasing caseload levels. However, as a result of these reductions, total CalWORKs expenditures remained relatively flat between 2008–09 ($5.3 billion) and 2011–12 ($5.4 billion).

In 2011–12, the CalWORKs program received $5.4 billion in total funding (see Figure 3). Absent policy changes proposed by the Governor, expenditures in CalWORKs would increase to $5.8 billion in 2012–13, primarily as a result of the restoration of a one–time $377 million cut to county single allocation funding. The Governor proposes various changes to avoid this year–over–year increase in CalWORKs expenditures, as well as make additional reductions totaling $583 million, for total General Fund savings of $985 million. The reductions proposed by the Governor would come primarily through a substantial reduction in cash grants for the majority of recipients and restricted eligibility for welfare–to–work services. These policy changes are encompassed in a redesign of the CalWORKs program administrative structure.

Figure 3

CalWORKs Budget Summary

All Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13 Proposed

|

Change From 2011–12

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Cash grants

|

$3,576

|

$3,278

|

$2,749

|

–$529

|

–16%

|

|

Employment services

|

1,074

|

946

|

938

|

–8

|

–1

|

|

Stage 1 child care

|

488

|

435

|

483

|

48

|

11

|

|

Administration

|

585

|

631

|

495

|

–136

|

–22

|

|

Other

|

620

|

97

|

139

|

42

|

43

|

|

Totals

|

$6,343

|

$5,387

|

$4,804

|

–$583

|

–11%

|

CalWORKs Redesign

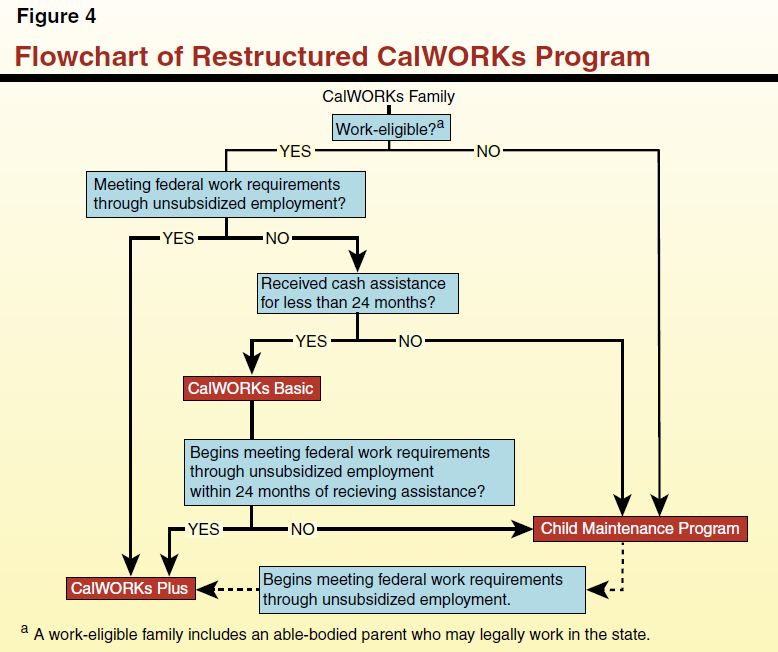

The Governor's proposal would replace the current CalWORKs program with a three–part system, consisting of two CalWORKs subprograms—CalWORKs Basic and CalWORKs Plus—and a Child Maintenance program. Figure 4 shows the process for determining which families qualify for each of these three programs. As the Governor's CalWORKs proposal would involve significant programmatic changes, CWDs would need sufficient time to make automation and staffing changes, as well as notify recipients of changes to grant and service levels. The Governor requests that the Legislature enact his CalWORKs proposal by March 1 to provide sufficient implementation time for counties. (We believe enactment could be delayed as late as April 1 without eroding savings.) The Governor proposes to begin implementing these changes in October 2012, with full implementation in April 2013. Over this six–month period, families that would otherwise be removed by the Governor's proposal to shorten time limits would continue to receive services.

Divides CalWORKs Into Two Subprograms. The CalWORKs Basic program would effectively continue the current CalWORKs program (including maintaining current cash assistance levels and employment services) for work–eligible adults for up to 24 months. The CalWORKs Plus program would serve families that are working sufficient hours in unsubsidized employment to meet federal work participation requirements. These families would receive 48 months (or an additional 24 months if they were transitioning from the CalWORKs Basic program) of eligibility for cash assistance, employment services, and child care. Families that exceed the 48–month limit would be eligible to continue receiving cash assistance (less the portion attributable to the parent) and services for as long as they continue to meet work requirements. Additionally, the earned income disregard for families in the CalWORKs Plus program would be somewhat more generous, excluding the first $200 (as opposed to $112) of all income and 50 percent of remaining income from cash grant calculations. Time limits in both CalWORKs Basic (24 months) and CalWORKs Plus (48 months) would be applied retroactively to all current CalWORKs recipients, including those previously exempted from work requirements or in sanction status.

Creates a Child Maintenance Program. This program would provide continued assistance for families that are no longer eligible for CalWORKs under the redesign. The Child Maintenance caseload would be comprised of families that: (1) have received 24 months of CalWORKs Basic assistance and are not working sufficient hours in unsubsidized employment, (2) have been in sanction status for three months, or (3) do not have a parent who is work–eligible. Cash assistance levels for families in the Child Maintenance program would be reduced in two ways: (1) MAP levels would be reduced by 27 percent as compared to what a family would receive in the current CalWORKs program, and (2) the earned income disregard would be reduced by $112. Additionally, Child Maintenance families would not be eligible for ongoing employment services or subsidized child care. (Families that are work–eligible and have not exceeded 48 months on aid may be provided one month of child care every six months to allow for job search.) The frequency of required income reporting would be reduced from quarterly (scheduled to change to semiannually in 2013) to annually for Child Maintenance families.

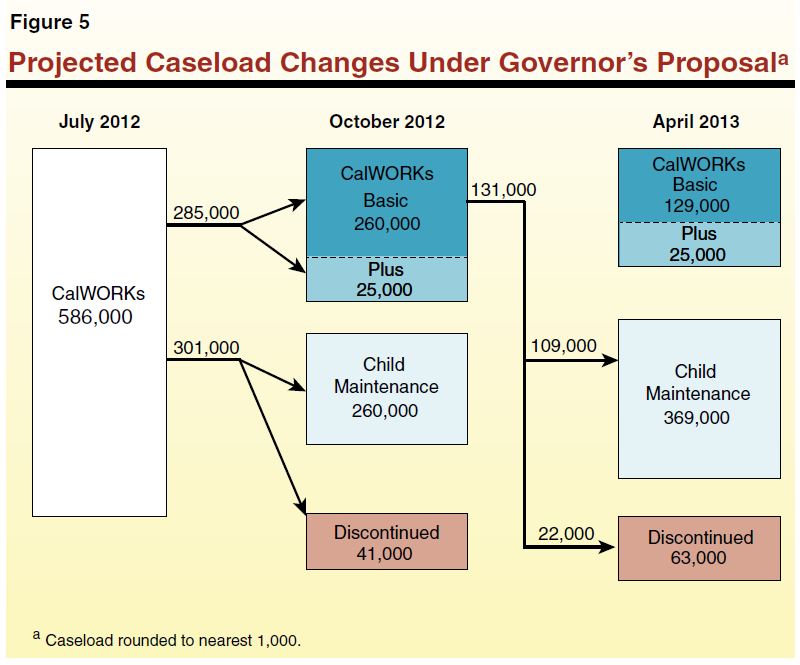

Impact of the Governor's Proposal on Caseload. Figure 5 shows the impact of the Governor's redesign on the existing CalWORKs caseload (586,000). As the figure shows, in October 2012, a total of 301,000 cases would be removed from the CalWORKs program. These cases would be comprised of existing child–only, safety–net, and chronically sanctioned (sanctioned three or more months in a 12–month period) cases. Of these cases, about 260,000 cases would transition to the Child Maintenance program while about 41,000 cases would be discontinued due to lower income eligibility thresholds resulting from the change in the earned income disregard and grant reductions. In April 2013, about 131,000 cases would be removed from CalWORKs Basic due to shortened time limits for eligibility. The majority of these cases (109,000) would be placed in the Child Maintenance program, while the remainder (22,000) would be discontinued (for the reasons indicated above). Altogether, about 432,000 existing cases (74 percent) would be adversely impacted by the Governor's proposal either due to reduced cash assistance by being placed in the Child Maintenance program or having their cases discontinued.

Governor's Budget Likely Underfunds County Responsibilities

The Governor's budget calculates county single allocation funding for child care for current CalWORKs recipients and county administration of the CalWORKs program based on unit costs that are lower than actual costs in past years. While proposed administrative efficiencies (such as reducing the frequency of income reporting requirements for Child Maintenance cases) could lead to somewhat lower administrative costs, the Governor likely is underestimating the actual costs counties will face. To accommodate insufficient funding for child care and county administration, counties could either redirect funds from employment services or request a midyear augmentation from the state (resulting in reduced budgetary savings).

To achieve the bulk of his savings ($890 million of the $985 million), the Governor proposes three significant changes to the CalWORKs program: (1) reducing cash grants, (2) shortening the adult time limit for the receipt of benefits, and (3) modifying work requirements. These policy changes would be accompanied by proposed changes to the administrative structure of the CalWORKs program. We believe that the Governor's proposed policy changes could be adopted and associated savings achieved without changing the administrative structure of the program. Moreover, the proposed administrative changes do not yield any apparent programmatic benefits in terms of efficiencies or effectiveness. Thus, we recommend the Legislature focus its evaluation on the major policy changes inherent in the Governor's proposal and reject the Governor's proposed administrative changes. Below, we describe, assess, and offer modifications to the Governor's proposed policy changes. We also offer rough estimates of the full–year savings (if changes took effect July 1, 2012) associated with enacting these changes within the context of the current CalWORKs administrative structure. (These estimates consider each policy change in isolation and do not account for possible interactive effects.)

Reduced Cash Grants

Governor's Proposal Reduces Cash Grants for the Majority of Cases. The Governor proposes to reduce cash grants by 27 percent for current child–only, safety–net, and chronically sanctioned (sanctioned three or more months in a 12–month period) families. Upon full implementation of the Governor's proposal, about 74 percent of the current CalWORKs caseload would face reduced cash assistance. Figure 6 provides a breakdown of cash grants and CalFresh benefits that would be received by a family of three living in a high–cost county in each of the CalWORKs Basic, CalWORKs Plus, and the Child Maintenance programs. As shown in the figure, a family currently receiving a child–only grant would face a reduction of 27 percent if shifted to the proposed Child Maintenance program. (Due to interaction with the Governor's proposal to reduce the adult time limit, some families currently receiving a full cash grant—including an adult portion—would face a more substantial reduction of 41 percent if shifted to the Child Maintenance program.) The combination of a Child Maintenance cash grant and CalFresh benefits (for families with an eligible adult) would provide an average family of three resources equal to 56 percent of the federal poverty level. The full–year savings of a 27 percent cash grant reduction for child–only, safety–net, and chronically sanctioned cases would be approximately $610 million. If the Legislature were to reduce the magnitude of the Governor's proposed cash grant reduction, savings would be reduced by roughly $100 million for each 5 percent increment below 27 percent. For example, the state would receive full–year savings of around $510 million if it reduced these cash grants by 22 percent.

Figure 6

Comparison of Maximum Monthly Cash Assistance Levelsa

|

|

Current Law

|

Governor's Proposal

|

Change

|

Percent Change

|

|

CalWORKs Basic

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cash grant

|

$638

|

$638

|

—

|

—

|

|

CalFresh benefits

|

478

|

478

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$1,116

|

$1,116

|

—

|

—

|

|

Percent of FPL

|

72%

|

72%

|

—

|

—

|

|

CalWORKs Plus

|

|

|

|

|

|

Earningsb

|

$1,040

|

$1,040

|

—

|

—

|

|

Cash grant

|

174

|

218

|

$44

|

25.3%

|

|

CalFresh benefits

|

372

|

353

|

–19

|

–5.1

|

|

Totals

|

$1,586

|

$1,611

|

$25

|

1.6%

|

|

Percent of FPL

|

103%

|

104%

|

1%

|

—

|

|

Child Maintenance

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cash grant

|

$516

|

$375

|

–$141

|

–27.3%

|

|

CalFresh benefits

|

487

|

487

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$1,003

|

$862

|

–$141

|

–14.1%

|

|

Percent of FPL

|

65%

|

56%

|

–9%

|

—

|

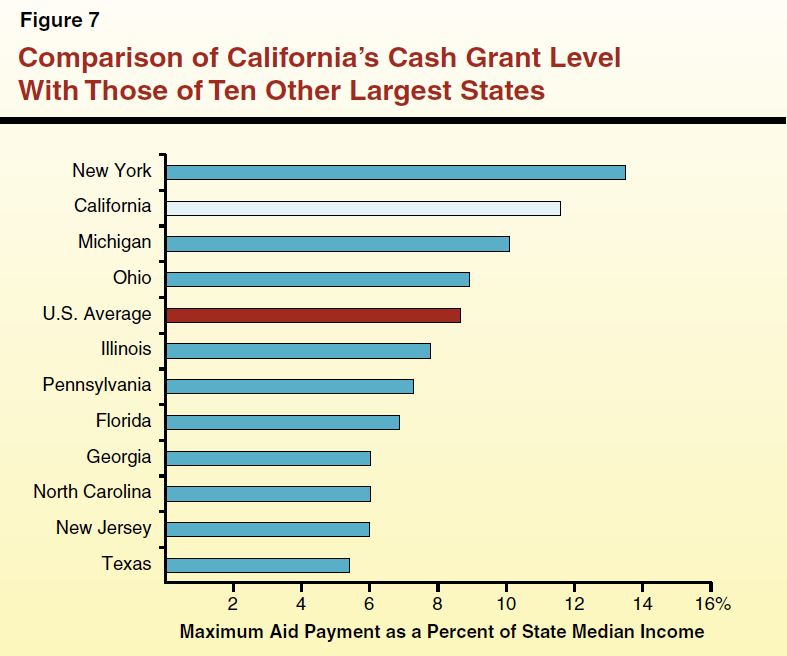

California Provides Higher Monthly Cash Assistance Than Other States. Figure 7 compares the MAP available for a family of three as a percentage of state median income in California and the ten other largest states. (Displaying the MAP as a percentage of state median income adjusts for varying income levels across states.) The figure shows a CalWORKs cash grant currently is equal to 11.6 percent of California median income for a family of three. This cash grant level ranks fourth highest among all states and second highest among large states. This cash grant level is 3 percentage points higher than the national average and almost 4 percentage points higher than the average of the ten largest states excluding California.

Proposed Cash Grant Reductions May Increase the Incentive for Recipients to Work. The Governor's reduction in cash grants for the proposed Child Maintenance cases could increase the incentive for these families to work by increasing the difference in cash assistance for families that are and are not working. Figure 8 demonstrates the effect of increasing the difference in cash assistance available to working and non–working families. As this figure shows, if the parent of a family of three currently in sanction status with no earned income were to obtain a part–time job earning $1,040 monthly, the family's overall monthly resources would increase by $839 under the Governor's proposal (after adjusting for a reduced CalWORKs cash grant), as compared to $698 under current law. (Incorporating the Governor's proposed increased earned income disregard, the family's monthly resources would increase by $883.) However, the proposed Child Maintenance caseload is likely to face more barriers to self–sufficiency than other families, possibly dampening the impact of these increased work incentives.

Figure 8

Comparing Work Incentives

|

|

Current Law

|

Governor's Proposal

|

|

Nonworking Familya

|

|

|

|

Earnings

|

—

|

—

|

|

Cash grant

|

$516

|

$375

|

|

Totals

|

$516

|

$375

|

|

Working Familyb

|

|

|

|

Earnings

|

$1,040

|

$1,040

|

|

Cash grant

|

174

|

174

|

|

Totals

|

$1,214

|

$1,214

|

|

Benefit of Working

|

|

|

|

Earnings

|

$1,040

|

$1,040

|

|

Change in cash grant

|

–342

|

–201

|

|

Net Benefit

|

$698

|

$839

|

Proposed Child Maintenance Cases May Face More Barriers to Self–Sufficiency Than Other Cases. Review of caseload characteristics and relevant research suggests that Child Maintenance cases may face more barriers to self–sufficiency than the average CalWORKs family. Figure 9 provides a breakdown of the caseload of the Governor's proposed Child Maintenance program. The largest segment of this population is cases with an undocumented parent (44 percent), followed by safety–net cases (16 percent). Overall, only 19 percent of these families are headed by a parent with a high school diploma or General Education Development credential, as compared to 53 percent of all other CalWORKs families. Additionally, only 50 percent of these families speak English as a first language, as compared to 86 percent of all other CalWORKs families. Our review of relevant research indicates that the second largest segment of the child–only population—safety–net and chronically sanctioned cases—are more likely to face one or more barriers to self–sufficiency, such as limited education or work experience, physical or mental health problems, or issues with transportation. Altogether, this evidence suggests that the target population of the Governor's proposed CalWORKs cash grant reductions faces more barriers to self–sufficiency than the CalWORKs caseload as a whole. This therefore dampens the potential for the Governor's proposed cash reductions to serve as a work incentive.

Figure 9

Breakdown of the Child–Maintenancea Caseload

|

Type

|

Cases

|

Percent of Child–Only

|

|

Undocumented parents

|

133,083

|

44.2%

|

|

Safety–netb

|

46,884

|

15.6

|

|

Non–needy caretaker relative

|

39,198

|

13.0

|

|

Supplemental Security Income parents

|

38,239

|

12.7

|

|

Chronically sanctioned (more than three months)

|

22,328

|

7.4

|

|

Other

|

16,160

|

5.4

|

|

Drug and fleeing felon parents

|

5,108

|

1.7

|

|

Totals

|

300,999

|

100.0%

|

Cash Grant Reductions Could Instead Be Applied to All CalWORKs Families. If the Legislature wishes to avoid concentrating the impact of cash grant reductions on a population of recipients that may, in some cases, have more difficulty securing employment, it could consider making an across–the–board cash grant reduction. To generate an equivalent amount of savings as the Governor through an across–the–board grant reduction, we estimate that cash grant levels would need to be reduced by 17 percent—10 percentage points less than the Governor's targeted cash grant reduction. In general, savings of around $190 million (with some additional savings associated with larger reductions due to a greater number of discontinued cases) could be achieved for every 5 percent reduction in cash grants for all cases.

Phasing in Cash Grant Reductions Could Lessen Immediate Impact on Recipients. The Legislature also may wish to consider mitigating the impact of any cash grant reduction that it might choose to make. A potential option would be to phase in any reduction over several months. A phase–in period could provide families time to adjust to changes in available resources and help to mitigate problems associated with a sudden decrease in benefits. Implementing a 27 percent cash grant reduction for child–only, safety–net, and chronically sanctioned cases over a six–month phase–in period (for example, three months of no reduction followed by three months of partial reduction) would result in savings of about $390 million in 2012–13 (a loss of $70 million in savings relative to the Governor).

Shortened Time Limit for Assistance

Governor's Proposal Significantly Shortens Time Limit for Access to Full Array of CalWORKs Services. The Governor's proposal to divide CalWORKs into two subprograms is generally equivalent to reducing the adult time limit for the current CalWORKs program to 24 months, while continuing to maintain a 48–month time limit for adults that are working sufficient hours in unsubsidized employment. The Governor proposes to implement this change retroactively and to count prior months in which families were exempt from welfare–to–work or sanctioned for noncompliance towards the new time limit. An estimated 131,050 adults that have received aid for more the 24 months would lose cash assistance and services under the Governor's proposal. We estimate that the full–year savings of implementing this proposal under the current program structure would be around $380 million.

Shortened Time Limits Could Increase Imperative for Recipients to Move Toward Self–Sufficiency. Decreasing the amount of time nonworking CalWORKs adults can receive cash assistance could encourage CalWORKs recipients to more aggressively pursue work. Though little research exists on the impact of shortening time limits, the evidence that they serve to induce increased work among welfare recipients is mixed. Several older studies have found time limits generally can produce an "anticipation effect" that increases employment among recipients prior to reaching time limits. While the majority of these studies examined time limits that result in full grant elimination, there is some evidence that partial grant elimination—as is the case in California—can have a positive but less pronounced effect on employment. More recent work by the Public Policy Institute of California, however, does not find evidence that time limits resulting in partial grant elimination have a significant impact on employment among low–income single mothers. Based on this available evidence, the Governor's time limit proposal likely would have a positive, but limited, effect on employment of CalWORKs recipients.

Counting Prior Months in Exemption Toward Time Limit Is Inconsistent With Prior Policy. Under current law, adults are granted exemptions from participating in welfare–to–work activities under various circumstances, such as when the adult is disabled, of advanced age, or caring for a very young or ill child. Under current law, months during which an adult is exempt from work requirements do not count against the adult's 48–month time limit. More recently, in connection with budget reductions, exemptions have been expanded to include parents caring for one child under the age of two or multiple children under the age of six. (Exemptions generate savings for the state because employment and child care services generally are no longer provided.) Generally, exemptions give recipients the option to defer welfare–to–work activities with the understanding that they will be able to resume those activities at some point in the future without reducing their duration of eligibility. There are currently a total of about 105,000 cases that have received exemptions. The Governor's proposal would retroactively count months in exemption towards an adult's time limit, thereby significantly reducing the availability of future services. By doing so, the proposal would be inconsistent with prior policy under which recipients may have elected not to volunteer for welfare–to–work with the understanding that these services would be available in the future. To mitigate this issue, the Governor proposes to provide a six–month transition period for all current work–eligible CalWORKs families.

In Considering Time Limit Reductions, Recommend Legislature Not Count Prior Months in Exemption. Given the adverse effect on certain families, we recommend the Legislature not count prior months in exemption towards an adult's time limit. Our full–year savings estimate of implementing the Governor's time–limit proposal would be reduced by approximately $90 million if the prior months in exemption were not counted.

Legislature Could Consider Aligning Time Limit With Average Time on Aid. If the Legislature believes the Governor's shortened time limit is too severe, it could consider making a less dramatic change to the time limit. One option would be to align the adult time limit with the historical average time on aid among CalWORKs recipients (about three years). Reducing the adult time limit to 36 months without counting prior months in exemption would result in annual savings of roughly $140 million.

Changes to Work Requirements

Governor's Proposal Aligns State and Federal Work Requirements. As part of his redesign of the CalWORKs program, the Governor proposes to align the current CalWORKs work requirements with federal TANF requirements. Aligning to the federal requirements would reduce the required number of hours of participation for single parents (a majority of the caseload) but restrict the scope and time line for higher education activities and mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence treatment. Altogether, about 35,000 cases (about 30 percent of those participating in work activities) are currently participating in activities that could be affected by the Governor's proposal. The Governor's budget does not directly attribute any fiscal effect to this proposal. We find that the net savings of aligning state and federal work requirements are difficult to predict due to uncertain behavioral responses among CalWORKs recipients. However, such a policy change would somewhat reduce the risk of future TANF losses due to federal WPR–related penalties.

Aligning to Federal Work Requirements Would Likely Increase the State's WPR. Under current law, a CalWORKs recipient could be in compliance with state work requirements, while failing to meet federal requirements and, therefore, not contribute to the state's WPR. This occurs primarily because the work activities allowed by state law are more permissive than those allowed by federal law. If state and federal requirements were aligned, CalWORKs recipients no longer would be permitted to participate in activities that do not contribute to the state meeting its WPR. This likely would redirect recipients to participate in federally allowable activities, thus increasing the state's WPR. Increasing the state's WPR would reduce the risk of future federal penalties.

Changes in Work Requirements Likely Would Have a Mixed Impact on Welfare–to–Work Sanctions. Aligning to federal work requirements could potentially have offsetting effects on the number of CalWORKs families subject to sanctions for noncompliance. On the one hand, reducing the required hours likely would make meeting work requirements easier, thus reducing the likelihood of sanction. (For single mothers with a child under six—a majority of the work–eligible caseload—required hours would drop by 38 percent.) Conversely, restricting the list of allowable work activities could make meeting work requirements more difficult, thus increasing the likelihood of sanctions. Although specific behavioral responses are difficult to predict, aligning state and federal work requirements would likely, on balance, reduce the number of cases subject to sanctions. A reduction in the number of sanctioned cases would likely result in increased CalWORKs cash grant costs.

Requiring Breaks in Treatment for CalWORKs Purposes Problematic. Under current law, generally no limit exists on the amount of time mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence treatments can count towards a CalWORKs recipient's required hours of participation. The Governor's proposal would limit these activities for CalWORKs purposes to: (1) a total of 180 hours per year (360 hours during periods of growth in the state's unemployment rate or CalFresh caseloads) and (2) no more than four consecutive weeks. Due to these proposed changes, a CalWORKs recipient in a treatment program might, in some circumstances, be required to interrupt treatment every four weeks. (In some circumstances counties could use administrative workarounds to allow continued treatment.) Individual treatment time in these programs is likely to vary significantly. Thus, determining how many recipients would be affected by the Governor's proposal is difficult. However, due to variation in individual treatment times, establishing a single time limit for all recipients is problematic, as some recipients likely would be moved into other work activities before adequate treatment has been provided.

Recommend Making Allowances for These Treatments. Aligning state and federal work requirements generally merits consideration as it would help to improve the state's WPR and reduce the risk of associated federal penalties. However, we believe that the Governor's proposed limitations for mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence treatments are impractical and detrimental to the successful implementation of these treatments. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposal and not adopt the federal limitations relating to these treatments.

Cal–Learn

Eliminates the Case Management Portion of the Cal–Learn Program. The Cal–Learn program provides intensive case management to about 12,000 CalWORKs teen parents who remain in school. Depending on a student's academic performance, the teens may earn bonuses or be subject to sanctions (a decrease in the CalWORKs cash grant). The 2011–12 Budget Act suspended the case management portion of the Cal–Learn program (the bulk of the program's expenditures) but maintained funding for the performance bonuses. The Governor proposes to permanently eliminate the case management portion of the Cal–Learn program (avoiding $35 million in otherwise higher costs in 2012–13).

In Light of Budget Constraints, Proposed Elimination Has Merit. Under the Governor's proposal, counties would be allowed to continue funding Cal–Learn using the employment services allotment of their single allocation funding. Thus, counties would be allowed to prioritize limited employment services resources between Cal–Learn recipients and the general CalWORKs population based on local needs. In light of budgetary constraints in the CalWORKs program, we believe this proposal merits serious consideration by the Legislature.

Cash Grants for Work–Exempt Families

Eliminates Higher Grants for "Work–Exempt" Families. Under current law, a CalWORKs family may qualify for a higher cash grant (about 10 percent greater) if the adult in the family is either a caretaker relative or a parent who is receiving: (1) SSI, (2) In–home Supportive Services, (3) State Disability Insurance, or (4) workers' compensation temporary disability payments. These families are referred to as work–exempt. Currently, about 18 percent of CalWORKs families are classified as work–exempt. Higher cash grants for work–exempt families were originally established to compensate for the inability of many of these cases to augment their cash grant through employment, unlike families with able–bodied adults. The Governor proposes to eliminate these higher cash grants, reducing the grant for these families by about $54 per month, on average, for total associated savings of $50 million.

Eliminating Higher Grants for Some Work–Exempt Families Merits Consideration. Although most work–exempt families have limited or no ability to obtain earned income, the majority are receiving disability–related income. For this reason, we think eliminating the higher cash grants warrants legislative consideration. The merit of eliminating higher cash grant levels for caretaker relatives is less clear, as this could discourage relatives from assuming care of children, resulting in potentially increased costs in child welfare services.

Using TANF Funds for Cal Grant Costs

Uses Freed–Up TANF Funds for Cal Grant Costs. Because of federal MOE requirements, the Governor cannot reduce state spending for the CalWORKs budget. Thus, to realize General Fund savings from his CalWORKs changes, he proposes to use TANF funds freed up from the CalWORKs reductions for Cal Grant costs and, in turn, achieve General Fund savings in that program. Specifically, the Governor proposes to transfer $736 million in TANF funds to the Student Aid Commission to fund Cal Grants, resulting in General Fund savings of a like amount. According to the administration, the use of TANF funds for Cal Grants is allowable under the third and fourth purposes of TANF. This proposal is simply a change in fund source and would not have a programmatic effect on the Cal Grant program.

Transfer of TANF to Student Aid Commission Is Needed to Realize General Fund Savings. The Governor's proposal to use TANF funds for a portion of Cal Grants is needed to realize maximum General Fund savings from making reductions in the CalWORKs program while continuing to meet MOE requirements. Once the Legislature decides upon a level of CalWORKs savings, we recommend using the Governor's TANF transfer/Cal Grants approach as the mechanism to achieve General Fund savings.

Expansion of Work Incentive Nutritional Supplement (WINS) Program

Expands Supplemental Work Bonus Program Scheduled to Begin in 2013–14. As part of the 2008–09 budget package, the Legislature established the WINS program, which is intended to provide $40 in additional monthly benefits to CalFresh families who are meeting federal TANF work requirements but are not in the CalWORKs program. Subsequent budget actions in 2009 and 2011, however, postponed implementation of the program until October 2013. A primary purpose of this program is to increase the state's WPR, thereby helping the state meet federal requirements. The Governor proposes to implement the program as scheduled, as well as increase the monthly benefit from $40 to $50. Additionally, the Governor would create a new WINS Plus program that would provide a $50 monthly benefit to families receiving subsidized child care who are meeting federal TANF work requirements but are not in the CalWORKs program. This change also is intended to help the state meet the federal WPR requirement. The Governor's proposed expansion would not result in costs in 2012–13 but would increase ongoing annual costs for WINS by about $53 million (increasing total program costs from $72 million to $126 million) following implementation in 2013–14.

Proposal Reduces the Risk of Future Federal Penalties . . . Absent corrective action, the state is likely to fall short of its federal WPR by as much as 20 percentage points to 25 percentage points for the foreseeable future. The WINS program, as designed under current law, would help to increase the state's WPR by an anticipated 10 percentage points beginning in 2013–14. The Governor's proposed expansion of the WINS program would likely further increase the state's WPR. While these increases alone would not allow the state to meet its WPR, it would bring the state considerably closer to its goal and reduce the risk of future federal penalties.

. . . But Legislature Could Modify the Proposal to Reduce Costs. Under the Governor's proposed expansion of WINS, ongoing costs are $126 million. The following modifications could be made to the Governor's proposal to reduce ongoing costs by as much as $100 million, while still receiving all or most of the WPR benefit: (1) require that all new CalFresh and subsidized child care applicants also apply for WINS or WINS Plus at time of application, (2) require application for WINS and WINS Plus as a condition of ongoing eligibility for current CalFresh and subsidized child care recipients, and (3) reduce the monthly benefit from $50 to $10. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor's proposal to expand the WINS program, with the modifications described above. (If the Legislature does not adopt the Governor's income and work–related child care eligibility proposals, the administrative complexity and potential costs of WINS Plus likely would be somewhat greater.)

The Legislature may wish to modify the Governor's proposals or pursue alternative options for achieving CalWORKs savings. Figure 10 provides a "menu of options" that summarizes the reductions proposed by the Governor, ways the Legislature could modify those proposals, as well as four additional approaches to consider. We discuss the four additional options below.

Figure 10

Options for Generating CalWORKs Savings

|

Maximum Aid Payment Levels

|

|

Current Law: A family of three with an eligible adult receives a monthly cash grant of $638. A family of three without an eligible adult (child–only, safety–net, and sanctioned cases) receives a monthly cash grant of $516.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: Reduce cash grants for child–only, safety–net, and chronically sanctioned (three sanctions in prior 12 months) by 27 percent (family of three receives a monthly cash grant of $375). Full–year savings would be around $610 million.

|

|

Option: Implement a lesser reduction. Savings are reduced by about $100 million for each 5 percent increment below the Governor's proposed 27 percent reduction.

|

|

Option: Implement cash grant reduction on all CalWORKs cases. For each 5 percent reduction, savings are approximately $190 million. A reduction of 17 percent would generate roughly equivalent full–year savings to the Governor's proposal.

|

|

Option: Phasing in a 27 percent cash grant reduction for child–only, safety–net, and chronically sanctioned cases over six months would save about $390 million in 2012–13.

|

|

Adult Time Limit

|

|

Current Law: Able–bodied adults are eligible for up to 48 months of cash assistance, employment services, and subsidized child care.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: Reduce the adult time limit to 24 months for adults not meeting federal work participation requirements through unsubsidized employment. Prior months in which families were exempt from welfare–to–work would be counted toward the limit. Around $150 million in 2012–13 savings and $380 million in full–year savings.

|

|

Option: Do not count prior months in exemption toward 24–month time limit, resulting in forgone full–year savings of about $90 million.

|

|

Option: Shorten time limit to 36 months, resulting in savings of approximately $140 million.

|

|

Cal–Learn

|

|

Current Law: The Cal–Learn program provides supplementary intensive case management for CalWORKs teen parents who remain in school. This case management was suspended in 2011–12.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: Eliminate most of the Cal–Learn program, resulting in savings of $35 million.

|

|

Higher Cash Grants for Work–Exempt Families

|

|

Current Law: Work–exempt families (such as recipients of disability income and non–parent relative caretakers) receive a cash grant which is about 10 percent higher than other families.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: Eliminate higher cash grants for work–exempt families, saving about $50 million.

|

|

County Single Allocation

|

|

Current Law: A reduction to county single allocation funding and associated expanded welfare–to–work exemptions will expire at the end of 2011–12, resulting in increased CalWORKs expenditures of $377 million.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: None.

|

|

Option: Continue the current–year single allocation reduction, resulting in savings of $377 million.

|

|

Earned Income Disregard

|

|

Current Law: A portion of a family's earned income (the first $112 and 50 percent of the remainder) is disregarded in cash grant calculations.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: Decrease the earned income disregard by $112 for proposed Child Maintenance cases and increase earned income disregard to $200 and 50 percent for families meeting work participation requirements through unsubsidized employment.

|

|

Option: Modify earned income disregard for all families to $225 and 25 percent resulting in savings of about $70 million.

|

|

Sanctions

|

|

Current Law: Families with an eligible adult who is not compliant with work requirements for three or more months are assessed a sanction equal to the adult portion of the cash grant.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: None.

|

|

Option: Reducing cash grants for these families by 50 percent would result in savings of about $40 million.

|

|

Time Limits for Long–Term Cases

|

|

Current Law: Regardless of adult time limits, a family may receive aid on behalf of a child until the child turns 18–years old.

|

|

Governor's Proposal: None.

|

|

Option: Reduce cash grants for families after an extended period on aid. Each 10 percent reduction in cash grants for families on aid for eight years or longer results in about $50 million in savings (ten years or longer results in about $30 million in savings).

|

Continue the Current–Year Single Allocation Reduction. The Legislature could consider continuing recent unallocated reductions to county block grants. In each of the last three years, the state has reduced county single allocation funding for employment services and child care as a means of achieving budgetary savings. In 2011–12, single allocation funding was reduced by $377 million. These reductions have been accompanied by expanded exemptions from work requirements, which allowed counties to manage the single allocation reduction by reducing employment services and child care caseloads. (With the exemptions, the number of sanctions for failure to meet work requirements has also declined accordingly.)

To generate savings in 2012–13, the Legislature could extend the current–year single allocation reduction and associated exemptions and continue to save $377 million. One specific advantage of this option would be that these reductions have already been in place for three years, therefore continuing them would likely not result in a new reduction of service levels. However, the current single allocation reduction and exemptions come with a trade–off, as they weaken the work component of the CalWORKs program. That is, since the implementation of the expanded welfare–to–work exemptions, the percentage of adults participating in some work activities has decreased by 11 percent. Although some of this reduced participation could be attributable to other factors, such as the recent economic downturn, maintaining the current–year policies would likely have some negative effect on the state's WPR, increasing the risk of federal penalties.

Reduce the Earned Income Disregard. The Legislature could consider altering existing earned income disregard policies. In general, an earned income disregard has two primary effects: (1) to increase the incentive for families to begin working by reducing the amount of cash assistance lost from earnings and (2) to increase the earned income threshold at which families "income out" of CalWORKs. Reducing the earned income disregard generates savings primarily by decreasing benefits for families with relatively more resources. Such a change would also be likely to reduce incentives for CalWORKs recipients to pursue employment. However, it is possible to mitigate this effect by structuring the earned income disregard in a way that allows families to benefit considerably from initial earnings, while decreasing the amount of earned income disregarded at higher levels of earnings. For example, changing the earned income disregard to exclude the first $225 and 25 percent of all remaining earned income (current law excludes the first $112 and 50 percent of the remainder) would maintain about the same disregard for low levels of earnings, while reducing cash grants for families with the highest levels of earned income. Such a change would result in annual savings of roughly $70 million.

Increase Sanctions Imposed for Noncompliance With Work Requirements. The Legislature could impose stricter sanctions on CalWORKs participants who fail to meet welfare–to–work requirements. Under current law, if a CalWORKs family with an able–bodied adult is not complying with work requirements, the family may be subject to a sanction, which reduces the family's grant by the amount attributable to the adult. The severity of California's sanction policy is less than most other states, many of which discontinue aid for an entire family due to continued noncompliance with work requirements. Research on the impact of sanctions suggests that the effects on welfare recipients are disparate. The segment of cases that respond to more severe sanctions with increased work participation generally experience increased economic well–being, while those that do not respond experience a state of increased poverty. In this regard, more severe sanction policies involve a difficult trade–off of likely increases in work participation with equally likely increases in poverty among some families. One possible option for increasing the severity of sanctions would be to reduce a family's grant by 50 percent upon three months of noncompliance with work requirements. This option recognizes the trade–offs discussed above by not fully eliminating benefits for any family. This option would result in annual savings of around $40 million.

Impose Time Limits After Long Periods of Aid. The Legislature also could consider reducing benefits for families that have received aid for an extended period of time. Currently, slightly more than 100,000 cases in the CalWORKs program have received aid for eight or more years. Of these cases, around 65,000 have received aid for ten or more years. The largest segments of this caseload are safety–net families and families with undocumented parents. While many long–term cases are likely to face significant barriers to self–sufficiency, the needs of families that have already received extended assistance could be weighed against the needs of other CalWORKs families—especially newer cases that have received comparatively less assistance. Reducing cash grants for families that have received aid for ten or more years by 10 percent would result in savings of around $30 million. Similarly, reducing cash grants for families that have received aid for eight or more years by 10 percent would result in savings of around $50 million. (In both cases, savings would be roughly equivalent for each additional 10 percent reduction.)

As with CalWORKs, the Governor has major proposals related to the state's subsidized child care and development (CCD) programs, including several policy proposals designed to achieve budgetary savings, as well as a proposal to restructure the CCD system. Below, we provide background on California's CCD programs and a high–level overview of the Governor's CCD budget package. We next describe and assess the Governor's major savings proposals and identify other savings options the Legislature could consider were it to reject some or all of the Governor's proposals. We then describe, assess, and offer modifications to the Governor's restructuring plan.

Subsidized Child Care Provided Through a Variety of Programs. Figure 11 provides a description, as well as participation levels, for each of the state's CCD programs. All programs currently are administered by the California Department of Education (CDE), with the exception of CalWORKs Stage 1, which is overseen by DSS. California traditionally has guaranteed subsidized child care for families that currently are participating or have participated in the CalWORKs program. However, budget reductions in 2010–11 and 2011–12 resulted in some eligible families not being served in the Stage 1 and Stage 3 programs. The state also funds subsidized child care slots for low–income working families that have not participated in CalWORKs. Because demand typically exceeds funded slots in these programs, waiting lists are used to prioritize access to non–CalWORKs care. As noted in the figure, about one–third of children attending the California State Preschool Program (CSPP) are supported by funding redirected from the General Child Care (GCC) budget.

Figure 11

Overview of State's Child Care and Development Programsa

2011–12

|

Program

|

Description

|

Estimated Number of Slots

|

|

CalWORKs Child Care

|

|

|

|

Stage 1

|

Stage 1 begins when a participant enters the CalWORKs grant program.

|

45,000

|

|

Stage 2

|

CalWORKs families are transferred into Stage 2 when the family is deemed stable. Participation in Stage 1 and/or Stage 2 is limited to two years after an adult transitions off cash aid.

|

65,000

|

|

Stage 3

|

A family may enter Stage 3 when it has exhausted its limit in Stage 2, and remain as long as it is otherwise eligible for child care.

|

25,000

|

|

Non–CalWORKs Child Care

|

|

|

California State Preschool Program

|

Part–day and full–day early childhood education programs for three– and four–year old children from low–income families. (Family does not need to be working to be eligible for part–day program.)

|

145,000b

|

|

General Child Care

|

One type of care for low–income working families not affiliated with CalWORKs program.

|

33,000

|

|

Alternative Payment

|

Another type of care for low–income working families not affiliated with CalWORKs program.

|

33,000

|

|

Migrant and Severely Handicapped

|

Programs targeted for specific populations of children.

|

6,600

|

|

Total

|

|

352,600

|

Families Currently Qualify for Subsidized Child Care for a Variety of Reasons. Under current law, families generally must meet two criteria to be eligible for subsidized child care. They must display "need" for care and earn less than 70 percent of state median income (SMI). (The part–day state preschool program is an exception in that need is not an eligibility requirement and up to 10 percent of families can exceed the SMI cap.) As long as families meet these requirements, their children can continue to receive services until they turn 13 years of age. Most families—over 90 percent of current child care cases—need care because parents are engaged in work, vocational training, or pursuing an education. Parents who are employed may receive child care benefits for the hours they are working, with no set hourly requirements or time limits. Parents engaged in vocational training or attending school can receive benefits for up to six years, provided they pass at least half of their courses or maintain a 2.0 grade point average. (Parents whose children attend a publicly funded child care center located on a college or university campus, however, are not subject to the six–year limit.) Additionally, about 6 percent of parents currently receive subsidized child care benefits because they are medically incapacitated, seeking a job, or seeking permanent housing. (In each of these latter two categories, a parent may receive child care benefits for up to 60 days per year.) The remaining caseload is made up of children under the care of child protective services (CPS) or at risk of abuse or neglect. These children qualify for care regardless of family income.

State Has Two Child Care Systems. As described in Figure 12, the state essentially has two distinct child care systems. One system consists of the three stages of CalWORKs child care and the Alternative Payment (AP) program—programs for which parents are offered vouchers to purchase care from licensed or license–exempt caretakers. The CalWORKs Stage 1 program is funded by DSS and locally administered by CWDs. The remaining voucher programs are funded by CDE and locally administered by 82 AP agencies across the state. The CDE distributes funding to AP agencies, and they in turn issue payments to child care providers and monitor parents' eligibility to receive services. (In 30 counties, CWDs have subcontracted with AP agencies also to run the Stage 1 program.) In contrast, under the second system, providers for the GCC, CSPP, Migrant, and Severely Handicapped child care programs contract with and receive payments directly from CDE. These mostly center–based programs also include additional programmatic components not required for providers paid through the voucher system. Because these additional program requirements (including developmental assessments for children, rating scales for classroom environments, and professional development for staff) are contained in Title 5 of the California Code of Regulations, these direct contractors often are referred to as "Title 5 centers." Voucher payments are based on regional market rates (RMR) and therefore vary across different areas of the state, whereas Title 5 providers all receive the same Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR).

Figure 12

State Has Two Subsidized Child Care Systems

|

|

Voucher–Based System

|

Direct Contractor System

|

|

Description

|

The California Department of Education (CDE) allocates funding to local Alternative Payment (AP) agencies.a The AP agencies issue vouchers to families, who in turn choose their own child care providers.

|

The CDE contracts directly with child care providers for a certain number of slots. Eligible families enroll in these subsidized slots.

|

|

Programs

|

- CalWORKs Stages 1, 2, and 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Migrant child care program

|

|

|

- Severely Handicapped Program

|

|

Types of Providers

|

- Licensed centers and family child care homes (FCCHs)

|

- Licensed centers and FCCHs

|

- Relatives or friends providing child care without a license ("license–exempt").

|

|

Standards

|

Licensed providers must meet basic health and safety standards and adhere Title 22 regulations.

|

Must meet health and safety standards and adhere to more rigorous Title 5 regulations.

|

|

Payment Rates

|

- Maximum voucher amounts are based on Regional Market Rates (RMR) and differ by county and age of child, with higher rates for infant/toddler care.

|

- Contractors are paid at a daily Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR) for each eligible child they serve.

|

- Current maximum rates for licensed providers are set at the 85th percentile of RMR, based on 2005 data. License–exempt providers can earn up to 60 percent of the region's licensed rate.

|

- The SRR is the same in all regions of the state, with additional funds provided to centers that care for infants/toddlers and children with special needs.

|

- Maximum monthly voucher rates for a preschool–age child in full–time licensed care range across counties from about $650 to about $1,110.

|

- The monthly rate for a preschool–age child in full–time care is about $715.

|

Recent Reductions to Child Care Programs. In recent years, the state has made significant reductions to CCD programs and operations. Since 2008–09, overall funding for the CCD system has dropped by about one–quarter. In the past three years, the state has: eliminated funding for approximately 20 percent of slots, reduced payment rates for license–exempt providers, lowered income eligibility thresholds, eliminated the "Latchkey" after school program, reduced administrative allowances for AP agencies and reserve balances for Title 5 centers, eliminated the state's Centralized Eligibility List, and reduced or eliminated several of the state's quality improvement projects.

Reduces Support for Subsidized Child Care Programs by 19 Percent. As shown in the top part of Figure 13, the Governor proposes to spend a total of $1.6 billion for child care programs in 2012–13—a reduction of $391 million, or 19 percent, compared to the current year. Total state funding would decrease by $468 million, offset by a $77 million increase in federal funds. Because the 2011–12 Budget Act shifted state support for all CCD programs other than the part–day preschool program from Proposition 98 to non–Proposition 98 General Fund monies, we display funding levels for part–day preschool separately at the bottom of the figure.

Figure 13

Child Care and Development Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12 Reviseda

|

2012–13 Proposed

|

Change From 2011–12

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Child Care

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expenditures

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CalWORKs child care

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 1

|

$486

|

$429

|

$482

|

$54

|

13%

|

|

Stage 2

|

458

|

442

|

292b

|

–151

|

–34

|

|

Stage 3

|

288

|

152

|

121b

|

–30

|

–20

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,232)

|

($1,023)

|

($895)

|

(–$127)

|

(–12%)

|

|

Non–CalWORKs child care

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Child Carec

|

$785

|

$675

|

$470

|

–$205

|

–30%

|

|

Alternative Payment

|

271

|

213

|

158b

|

–55

|

–26

|

|

Other child care

|

28

|

30

|

26

|

–4

|

–13

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,083)

|

($918)

|

($654)

|

(–$264)

|

(–29%)

|

|

Support programs

|

$100

|

$76

|

$76

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$2,415

|

$2,017

|

$1,626

|

–$391

|

–19%

|

|

Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

State General Fund

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Proposition 98

|

$856

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Non–Proposition 98

|

29

|

$1,069

|

$609

|

–$460

|

–43%

|

|

Other state funds

|

350

|

8

|

—

|

–8

|

—

|

|

Federal funds

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CCDF

|

602

|

533

|

548

|

15

|

3

|

|

TANF

|

467

|

406

|

468

|

62

|

15

|

|

ARRA

|

110

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Part–Day State Preschool

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expendituresd

|

$397

|

$368

|

$310

|

–$58

|

–16%

|

Governor's Proposal Generates Savings From Three Major Changes. Figure 14 provides additional detail on the Governor's specific changes to the child care budget. The Governor has three major savings proposals: (1) increasing parental work requirements, (2) lowering family income eligibility thresholds, and (3) reducing reimbursement rates for two categories of child care providers (displayed separately in the table). These proposals would lead to a combined $391 million in savings and over 63,000 fewer slots. About 75 percent of the savings results from the stricter work eligibility requirements. Below, we discuss each of the major proposed reductions, as well as offer some alternative options for the Legislature to consider if it were to reject some or all of the Governor's proposals and decide to make different policy changes and/or achieve a different level of overall CCD savings. (The figure also shows a $35 million augmentation for CWDs to ramp up their activities in anticipation of the proposed restructuring.)

Figure 14

Governor's Proposed Reductions to Child Care Programs

(In Millions)

|

|

Funding

|

|

County "ramp–up" for child care restructuring

|

$35

|

|

Limit eligibility to families meeting new work requirements

|

–294

|

|

Reduce reimbursement rates for centers that contract with CDEa

|

–68

|

|

Reduce income eligibility ceiling to 200 percent of federal poverty levela

|

–44

|

|

Reduce maximum reimbursement rates for child care vouchers

|

–17

|

|

Technical/caseload/adjustments

|

–4

|

|

Total

|

–$391

|

Work Requirements

Governor Reduces Child Care Eligibility by Applying Stricter Work Participation Requirements. The Governor proposes to institute minimum hourly work requirements and restrict the kinds of activities that qualify parents for subsidized care, generally consistent with the changes proposed for CalWORKs. Specifically, single–parent families with older children would have to work at least 30 hours of subsidized or unsubsidized employment each week. This requirement would be higher for two–parent households (35 hours) and lower for single parents with young children (20 hours). These new eligibility standards would apply to both CalWORKs participants and other low–income families receiving subsidized child care. The administration estimates these changes would eliminate eligibility for about 46,000 children from families whose parents are engaged in other activities—which is about one–fifth of the state's current child care caseload—and yield savings of $294 million.

New Eligibility Criteria Would Not Provide Subsidized Child Care on the Basis of Education and Training Activities. The Governor's proposal would have the most notable effect on the roughly 31,000 children currently receiving subsidized child care while their parents are engaged in training or attending educational programs at adult schools, community colleges, four–year universities, and graduate schools. Under the Governor's proposal, these families would have to make other child care arrangements (and assume any associated costs) or elect to stop going to school/training and instead find a job in order to maintain child care eligibility. Families working fewer than the required number of hours also would be affected by the proposed changes, though the administration estimates that most currently employed parents already are meeting the new minimum work requirement.

Administration's Estimates Likely Overstate Savings by Roughly $50 Million. We believe the administration has overestimated the number of children who would lose eligibility based on the proposed changes. As a result, we believe his savings estimate is overstated. Specifically, since the administration has clarified that the roughly 7,000 children under the care of CPS or living with an incapacitated caretaker would retain current eligibility, no savings should be scored associated with these populations. Accordingly, we estimate the Governor's proposed changes would only eliminate about 39,000 slots and yield about $250 million in savings.

Legislature Could Consider Modified Version of Governor's Proposal. If the Legislature wishes to continue supporting low–income families furthering their education, it could consider adopting a modified version of the Governor's proposal. The state could continue to provide child care to low–income parents engaged in training or education, but for a more limited period of time. Instead of the current six years (or indefinitely for parents using campus–based Title 5 child care centers), the state could limit child care eligibility based on educational activities to two years. This would allow parents a limited–term opportunity to pursue nonwork activities that might make them more employable in the long run, while at the same time prioritizing limited resources for those who currently are working. Because the state does not currently collect precise information on length of time in care, however, estimating how many families this would affect or the associated savings is difficult. Based on available data, we estimate the change could yield roughly $50 million in savings. To implement this change, the state would have to start keeping track of each family's duration of and reason for care.

Income Eligibility

Governor Reduces Income Eligibility Ceilings to 200 Percent of FPL. Currently, families eligible for the state's CCD programs can earn up to 70 percent of the SMI. (The income ceiling was reduced from 75 percent to 70 percent of SMI in 2011–12.) The Governor proposes to lower this income eligibility threshold to 200 percent of the FPL, or about 62 percent of SMI. For a family of three, this would drop the maximum eligible monthly income from $3,518 to $3,090. (This change is linked to the Governor's attempt to improve the state's WPR through bringing non–CalWORKs families receiving subsidized child care into his proposed WINS Plus program. Under federal law, 200 percent of FPL is the maximum amount a family can earn to receive TANF–funded services.) After accounting for the reduced caseload from the stricter work participation requirements, the Governor estimates that changing income ceilings would terminate child care eligibility for about 8,400 children currently being served. The Governor would eliminate the funding associated with these slots, saving $44 million. (The Governor also would apply this change to Proposition 98–funded part–day preschool, saving an additional $24 million and eliminating an additional 7,300 slots.)

Because It Prioritizes Service for Lowest Income Families, Governor's Proposal Merits Consideration. While the Governor's proposed change would reduce the number of families eligible to receive child care, as well as the overall number of available child care slots, it also would prioritize remaining slots for the state's lowest income families. Moreover, our review of other states' eligibility standards for subsidized child care indicates the Governor's proposed level would be more comparable to policies in other states. Our review suggests that only ten other states set maximum income eligibility for child care at or above 70 percent of their respective SMIs. In contrast, over half of all states set income ceilings at or below 62 percent of their SMIs and almost two–thirds of states set them at or below 200 percent of FPL. To achieve greater savings, the Legislature also could consider reducing income ceilings (and associated slots) even lower, to 50 percent of SMI (or 163 percent of FPL). We estimate about 15 states set child care eligibility at or below that threshold.

Provider Payments

Governor Reduces Maximum Reimbursement Rates for Most Child Care Providers. The Governor proposes to reduce the maximum amount the state will pay for licensed providers under both the voucher–based and direct contractor systems but maintain existing payments for caretakers who are not licensed by the state.

- Lowers RMR for Licensed Providers Paid Through Voucher System. Currently, the maximum voucher amounts the state will pay for licensed providers are set at the 85th percentile of RMR based on a 2005 survey of regional child care markets. The Governor proposes to reduce rates to the 50th percentile of RMR using 2009 survey data. Due to the updated data, the effective reduction to rates would be between 12 percent and 14 percent, on average. In Los Angeles county, for example, the proposal would drop the maximum daily voucher for a preschool–age child in full–time care from $43.27 to $37.79.

- Lowers SRR for Title 5 Direct Contractors. The Governor also would reduce the SRR by 10 percent, dropping the Title 5 per–child rate for full–day services from $34.38 to $30.94 and the part–day preschool rate from $21.22 to $19.10.