The Governor’s budget proposes to ask for voter approval of $48 billion in general obligation bonds. In this piece, we provide an update on the implementation of the bond package approved in 2006, describe the Governor’s new bond–related proposals, and analyze how the proposed additional bonds would affect the state’s debt–service payments for infrastructure.

In November 2006, California voters approved five propositions which authorized $42.7 billion in general obligation bonds. The bonds cover a range of purposes, including transportation, education, resources, and housing. Including principal and interest payments, the long–term costs of the bond package will be about $84 billion. As such, the bond package represented a major commitment by the Legislature, Governor, and the voters to improve the state’s infrastructure. As shown in Figure 1, the Legislature has authorized $12.5 billion of the bonds to be spent by the end of 2007–08. The Governor proposes to spend another $10.7 billion in 2008–09. In other words, under the Governor’s plan, 55 percent of the bond package total would be committed by the end of the budget year.

|

|

|

Figure 1

November 2006 Bond

Package Spending Plan |

|

(In Millions) |

|

|

|

|

Spending |

|

|

|

Total

Authorized |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

2008‑09 |

Future Years |

|

Proposition 1B—Transportation |

$19,925 |

— |

$4,163 |

$4,675 |

$11,087 |

|

Proposition 1C—Housing |

2,850 |

$160 |

973 |

771 |

946 |

|

Proposition 1D—Education |

10,416 |

2,041 |

3,609 |

3,605 |

1,161 |

|

Proposition 1E—Flood Control |

4,090 |

— |

444 |

461 |

3,185 |

|

Proposition 84—Resources |

5,388 |

60 |

1,058 |

1,216 |

3,054 |

|

Totals |

$42,669 |

$2,261 |

$10,247 |

$10,728 |

$19,433 |

|

|

Below, we describe the components of the Governor’s infrastructure bond proposals—a $48 billion new bond package, increased public–private infrastructure partnerships, and a new government commission.

The Governor proposes $48.1 billion in additional general obligation bond funding by 2010 to support a variety of infrastructure projects (see Figure 2). Of this amount, $38.3 billion would be placed on the November 2008 ballot, with the remaining $9.8 billion placed on the November 2010 ballot. Of the total, $23.9 billion would be for education purposes, such as the construction and modernization of K–12 and higher education facilities. The remaining bond funds would be allocated to water development and flood projects ($11.9 billion), high speed rail ($10 billion), court facilities ($2 billion), and state seismic projects ($0.3 billion). We describe the Governor’s bond proposals in each program area below. (We discuss several of the proposals in more detail in the programmatic chapters of this publication.)

|

|

|

Figure 2

Governor's Proposed

General Obligation Bond Package |

|

(In Billions) |

|

|

2008

Ballot |

2010

Ballot |

Totals |

|

K-12 education |

$6.4 |

$5.2 |

$11.6 |

|

Higher education |

7.7 |

4.6 |

12.3 |

|

Flood control/water supply |

11.9 |

— |

11.9 |

|

High speed rail |

10.0 |

— |

10.0 |

|

Courts |

2.0 |

— |

2.0 |

|

Seismic |

0.3 |

— |

0.3 |

|

Totals |

$38.3 |

$9.8 |

$48.1 |

|

|

K–12 Education. Regarding K–12 facilities funding, the Governor proposes $6.4 billion in general obligation bonds in 2008 and $5.2 billion in 2010. The proposed bonds would fund new construction projects, career technical education facilities, and charter school construction and rehabilitation in 2008. In addition to these programs, the 2010 ballot would include funding for modernization projects.

Higher Education. The Governor’s proposal for a 2008 higher education bond would provide $7.7 billion in funding over five years for capital projects at the three public higher education segments. The bond funds would be used to construct new buildings and related infrastructure, alter existing buildings, and purchase major equipment for use in these buildings. The proposed bond would provide approximately $4.6 billion more to the three segments than the Proposition 1D education bond in 2006, but it is intended to fund five years of construction rather than two years.

The proposed bond would authorize approximately $2 billion each in capital outlay funds for both the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU), and allocate almost $3.8 billion to the California Community Colleges. In addition to its normal capital needs associated with growth, modernizations, and seismic repairs, UC plans to direct some funds toward expanding its health sciences facilities, and CSU expects that some bond proceeds would be needed for off–site mitigation costs. A portion of the proposed 2008 bond would be used to complete UC and CSU projects already under way because the remaining balances of currently authorized bonds for those segments are not sufficient to cover the total costs of those projects.

Flood Control/Water Supply. The Governor proposes an $11.9 billion water management bond to be submitted to voters in 2008. This would fund: $3.5 billion for the “state’s cost share” of the design, acquisition, and construction of specified water storage projects; $3.1 billion to supplement existing bond authority for integrated regional water management

proposals; $2.4 billion to implement a strategic plan under development for sustainable management of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta; $1.1 billion for various restoration projects; $1.1 billion for water quality improvement projects; and $700 million for projects related to water recycling and restoration.

High Speed Rail. Chapter 697, Statutes of 2002 (SB 1856, Costa), authorizes the sale of $9.95 billion in general obligation bonds upon voter approval to fund the planning and construction of a high–speed train system linking California’s major metropolitan areas. The bond would provide $9 billion for a high–speed rail segment connecting San Francisco and Los Angeles. The other $950 million would be for projects that provide connectivity between the high–speed rail system and other modes of transportation. The bond measure is scheduled for the November 2008 ballot. The Governor’s budget summary indicates that proposed modifications to the bond measure may be forthcoming at a future date.

Courthouses. The $2 billion general obligation bond for the courts would provide immediate funding for the acquisition, design, construction, or renovation of court facilities. The Trial Court Facilities Act of 2002 (Chapter 1082, Statutes of 2002 [SB 1732, Escutia]) provided legal authority to transfer local court facilities to the state. The state will eventually have a substantial inventory of assets including 451 court facilities, 11 appellate court facilities, and 3 supreme court facilities. In its five–year infrastructure plan, the courts estimated that $9.7 billion would eventually be needed to bring all the courts up to secure and safe standards and accommodate growth. The $2 billion bond would fund the replacement of 12 courthouses ranked in the court’s highest project priority group and fund several (yet to be determined) upcoming projects. Many of the projects funded by this bond are scheduled for completion by 2013 or before.

Seismic. The remaining $300 million in general obligation bonds are proposed for the seismic renovation of 29 state facilities. Of this amount, the 2008–09 Budget Bill appropriates $68 million for 12 of these facilities. Specifically, the budget proposes to fund five California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation facilities, five Department of Mental Health facilities, and two Department of Developmental Services facilities.

The Governor’s budget includes a proposal on performance based infrastructure (PBI). While the term is not defined, it seems to involve a greater reliance on the private sector in the delivery of state capital outlay projects. The Governor’s Budget Summary refers to PBI as “partnering with the private sector” in the building of infrastructure and, in some cases, the maintenance and management of those assets.

The state has always relied predominately on the private sector to deliver its infrastructure. Private firms do the vast majority of the design work for projects and virtually all the construction of the state’s infrastructure. As such, it is unclear what specifically the administration is proposing to change. It may be, for instance, that the Governor wants to expand the use of design–build, a procurement process that the state has used more often in recent years. Or, it may be that the Governor wishes to increase the number or projects that are both built and operated by the private sector—such as toll roads. Alternatively, the administration may be asking the Legislature to authorize new forms of contracting and procurement to address the state’s future infrastructure needs.

Apparently, the administration will be proposing legislation regarding its PBI proposal. We will review these provisions when they become available, and provide comments and recommendations to the Legislature as appropriate.

The administration cites a number of infrastructure challenges that require additional coordination among governmental entities. Specifically, the administration seeks to better coordinate local government land use decisions and the state’s bond funding for local assistance grants and state projects. To this end, the administration proposes to create a Strategic Growth Council to coordinate state department activities, assist local government with its planning, and make recommendations to encourage greater sustainable development. The administration proposes to create the council through policy legislation. At the time this analysis was prepared, however, specific statutory language was not available to review. At this point, it is unknown what the proposed membership of the council would be, any powers the council would have, or its cost.

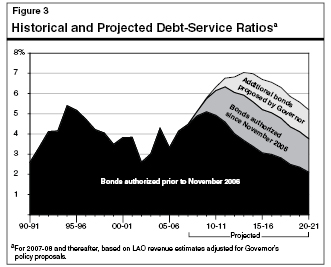

Below, we provide an update on the debt–service payments for infrastructure bonds that have already been authorized by the state and how the Governor’s proposed bonds would increase those payments.

Faced with ongoing structural budget shortfalls, as well as the administration’s proposals for additional borrowing, it would be prudent for the Legislature to consider how infrastructure borrowing fits into the state’s overall budget plan. The cost of the Governor’s proposed bond package in the next few years—and its impact on the state’s budget condition—will depend primarily on the volume and timing of bond sales, bond maturity structures, and the bonds’ interest rates. In turn, the overall affordability of the package will depend on how its costs affect the state’s future debt–service expenses—including costs for bonds that have already been sold, yet–to–be–sold bonds authorized both before and after the November 2006 election, and any future bond authorizations. For example, the state currently has about $43 billion of general obligation bonds outstanding on which it is making principal and interest payments, and another $72 billion in unsold bonds that have already been approved by the voters or authorized by the Legislature for various purposes.

Key Assumptions. Our cost projections are generally based on the administration’s assumptions about the timing of bond sales. These assumptions suggest annual bond sales from all authorizations totaling over $12 billion in 2007–08, rising to a peak of $18 billion in 2009–10. Our projections also assume:

- Maximum maturity lengths for general obligation and lease–revenue bonds of 30 years and 25 years, respectively.

- General obligation bond interest rates of 4.75 percent currently, declining slightly in the near term before trending up over time to 5.8 percent, with lease–revenue bond interest rates slightly higher.

Debt–Service Amounts. We currently estimate that the state’s annual debt–service costs for infrastructure–related debt authorized prior to November 2006 amounted to $4 billion in 2006–07, and will be $4.5 billion in 2007–08 and $5 billion in 2008–09. These costs will peak at $5.7 billion in 2010–11 as additional already–authorized bonds are marketed, and then decline slowly thereafter as the bonds are paid off over their lifetime. When the bonds approved since November 2006 are included (primarily the 2006 bond package and 2007 AB 900 [Solorio] prison facility lease–revenue bonds), total annual debt service is projected to rise from $4.5 billion in 2007–08 to a peak of $8.3 billion in 2017–18. Finally, when the additional general obligation and lease–revenue bonds proposed by the administration are included, debt service would peak at $11 billion in 2024–25.

The ratio of annual debt–service costs to yearly revenues is often used as a general indicator of a state’s debt burden. The DSR helps to look at debt from the perspective of affordability, as it takes into account the amount of revenues the state has available or is projected to have available relative to the programs it wishes to fund (including required debt–service payments). The higher the DSR, the smaller is the share of state revenues left to fund nonbond programs.

Although concerns have sometimes been voiced in the past about DSRs in excess of 5 percent or 6 percent, there is no “right” level for the DSR. Rather, this depends on such things as a state’s preferences for infrastructure versus other priorities, and its overall budgetary condition. Some states, for example, have comparatively high DSRs but still experience favorable bond ratings. Examples include Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.

From an affordability perspective, however, each additional dollar of debt service out of a given amount of revenues comes at the expense of a dollar that could be allocated to some other program area. Thus, the “affordability” of more bonds has to be considered not just in terms of their marketability and the DSR, but also whether their dollar amount of debt service can be accommodated on both a near– and long–term basis within the state budget. (As a rule of thumb, each $1 billion of new bonds sold at 5 percent interest adds close to $65 million annually in state debt–service costs for as long as 30 years.)

LAO Debt–Service Projections. Figure 3 shows California’s DSR in recent years and its projected value for the future. The DSR was well under 2 percent during most of the post–World War II period, increased in the early 1990s when it peaked at somewhat over 5 percent, and then fell below 3 percent in the early 2000s. It has since risen as new bond authorizations have been sold and revenues have slowed, and would peak at 6.3 percent in 2011–12 when considering all authorized bonds. Finally, including the new general obligation and lease–revenue bonds proposed in the Governor’s budget, the DSR would peak at 7 percent in 2013–14. On top of these amounts are the debt–service payments the state is making on the deficit–financing bonds (Proposition 57) that were issued to help address the state’s ongoing budget problems. Under the Governor’s budget proposals, these bonds would be paid off during 2012–13.

Return to Infrastructure Table of Contents,

2008-09 Budget Analysis

Return to Full Table of Contents,

2008-09 Budget Analysis