2009-10 Budget Analysis Series: Higher Education

Two of the most important determinants of higher education affordability are the level of fees charged to students and the availability of financial aid. Ideally, the state’s policies on fees and financial aid work together to maximize affordability for both students and the state.

Proposals Do Not Work Together to Maximize Access to Higher Education. Affordability and access depend on the interplay of fees and financial aid. For example, fee increases can provide revenue to maintain capacity at colleges and universities, while targeted aid increases can offset fee increases for needy students. The administration proposes significant fee increases at the universities for the third consecutive year, and financial aid reductions that fall disproportionately on university students. At the same time, the administration preserves the broad fee waiver program that covers fees for about 40 percent of community college enrollments, but misses an opportunity to maintain capacity at the colleges through increased fee revenues. In addition, the Governor proposes to reduce grants to students at private colleges at a time when public universities are planning to enroll fewer students. Moreover, the administration’s proposal would eliminate grants for nontraditional students (mostly working or unemployed adults) at a time of high unemployment. Finally, rather than increasing aid for lower–income students to keep pace with fee increases, the Governor proposes several cuts to core financial aid programs. We discuss the specific proposals below.

Fee Increases at the Public Universities

Governor’s Budget Recommends Fee Increases. For UC, the Governor’s budget assumes an increase of 9.3 percent in systemwide fees and increases ranging from 5 percent to 24 percent in fees for specified professional school programs. These increases are projected to generate $166 million in new fee revenue for UC. At CSU, the Governor’s budget reflects a 10 percent increase in fees for all students, generating an increase of $130 million in fee revenues.

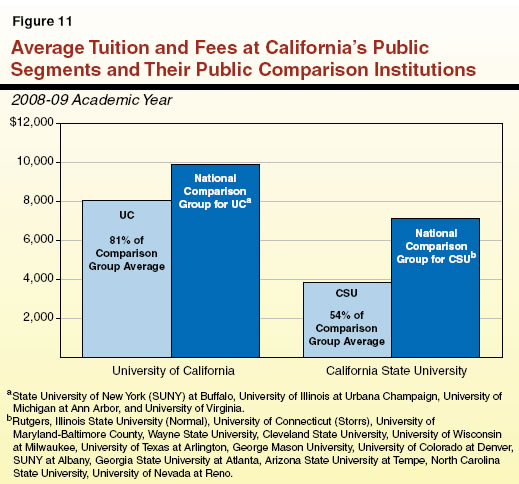

Current Fees Are Relatively Low. Current fee levels are relatively low at California’s public universities (and extremely low at the community colleges) by almost any state comparison measure. Figure 11 shows fees at UC and CSU compared with their national peer groups. Likewise, the share of educational costs paid by students in California, while growing in recent years, is still very low compared with other states.

Fees Are an Important Source of Support for Higher Education. Fee revenue works interchangeably with General Fund support to fund the core instructional mission of the public segments. A lower share of cost for students, as we have in California, necessitates higher costs for the state. The state’s portion (in the form of a general subsidy to the institutions) is paid for all students, not only lower–income students. A fee increase has the effect of increasing nonneedy students’ share of their college costs, thus reducing the state’s share. This can free up state resources that could be used to support higher education programs, including helping financially needy students, or to help balance the state budget.

Governor’s Budget Does Not Address New Revenues. While the Governor proposes increased fees at the universities, he does not account for the new fee revenues in spending or savings proposals. Instead, he leaves it up to the institutions to determine how the new resources are to be used. In contrast, we recommend the Legislature take these new revenues into consideration as part of total funding for higher education.

Approve Fee Increases, and Use a Portion of New Revenues to Maintain Financial Aid Programs. We recommend the Legislature combine fee increases with targeted aid for lower–income students. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature accept the Governor’s proposed fee increases at the universities, and reject the proposed reductions in Cal Grant programs (discussed below). The fee increases would generate about $300 million in new revenue. This would be more than enough to supplement institutional financial aid programs and maintain Cal Grant programs intact.

Fee Revenue Helps Colleges. Community colleges receive three main sources of general purpose funding: General Fund, local property taxes, and student fee revenue. In 2008–09, student fees are covering about $300 million of CCC costs. If General Fund support for CCC were to be reduced (as we recommend in order to help close the state budget gap), the effect of General Fund reductions on CCC programs could be softened by increasing fee revenue. For the budget year, however, the Governor proposes no change to the current student fee level of $20 per unit. As we describe below, various state and federal financial aid programs would minimize the impact of any fee increases on affordability and access.

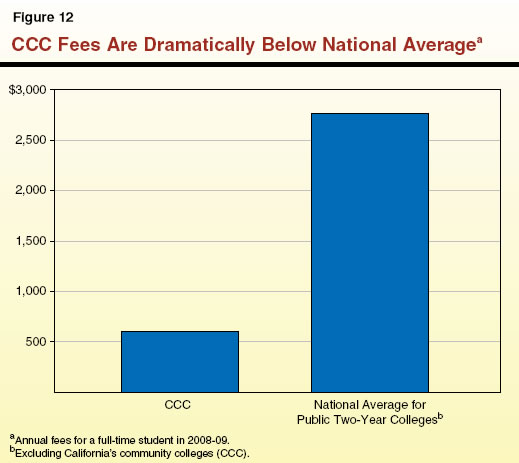

CCC Fees Are Low by National Standards. Over the past decade, community college fee levels for credit courses have fluctuated between $11 and $26 per unit. (There continues to be no charge for noncredit courses.) The state currently has no official policy for setting CCC fees. Often, fees have been increased during fiscally challenging periods, and reduced when budget situations improve. Despite this fluctuation, fees have consistently been the lowest in the country. Most recently, fees were reduced from $26 to $20 per unit in January 2007. As a result, a full–time student taking 30 units per academic year now pays $600 a year. This is about one–half that of New Mexico ($1,220, or about $40 per unit), which has the next lowest fees among public two–year colleges in the country. Figure 12 shows that the average for all other public two–year colleges ($2,760) is over four times the amount charged by CCC.

Fee Increase Would Not Affect Needy Students Since They Do Not Pay Fees. In considering any fee increase, the Legislature should consider how potential negative effects (primarily a reduction in affordability) could be mitigated or eliminated. For CCC students, affordability is preserved through the Board of Governors (BOG) fee waiver program. The program, which functions as an entitlement, requires students to demonstrate only $1 of need to receive full fee coverage. The program has relatively high income cut–offs. For example, a community college student living at home, with a younger sibling and married parents, could have a family income up to approximately $65,000 and still qualify for a fee waiver. The family’s income cut–off would increase to roughly $80,000 if this same student lived away from home. An older, independent student living alone could have an income up to roughly $45,000 and a student with one child could have an income up to roughly $80,000 and still qualify for fee waivers. Currently, about 30 percent of CCC students receive fee waivers, accounting for over 40 percent of all units taken.

Federal Government Will Reimburse Most Fee–Paying Students. Most of the students who do not qualify for BOG waivers are still eligible for federal financial assistance that covers all or a portion of their fees. Figure 13 provides basic information about the federal Hope tax credit, Lifetime Learning tax credit, and tuition and fee tax deduction. As the figure indicates, the Hope tax credit is designed for middle–income students during their first two years of college. Income requirements to qualify for the credit are relatively high. For example, students (or their parents) with a family income of up to $96,000 in 2008 are eligible for a federal tax credit equal to their entire fee payment—up to $1,200 per year—for their first two years of college. (The amount of the tax credit is gradually reduced between $96,000 and $116,000 for joint returns; $48,000 and $58,000 for single filers.) Therefore, while students have to pay their fees initially, they would be reimbursed for this cost as a federal income tax offset (so long as they have sufficient tax liability, which virtually all taxpayers at this income level do).

Figure 13

Federal Tax Benefits Applied Toward Higher Education Fees |

2008 |

Hope Credit |

Lifetime Learning Credit |

Tuition and Fee Deduction |

Directly reduces tax bill for up to two tax years. |

Directly reduces tax bill for unlimited number of years. |

• Reduces taxable income. |

Covers 100 percent of first $1,200 in fee payments. Covers 50 percent of second $1,200

(for maximum tax credit of $1,800). |

Covers 20 percent of first $10,000 in fee payments (up to $2,000 per tax year). |

Deducts between $2,000 and $4,000 in fee payments (depending on income level). |

Designed for middle-income students who:

—Are in first or second year of college.

—Attend at least half time.

—Are attempting to transfer or acquire a

certificate or degree. |

Designed for middle-income students who:

—Are beyond first two years of college.

—Carry any unit load.

—Seek to transfer or obtain a

degree/certificate—or simply upgrade job skills. |

Designed for any upper middle-income student not qualifying for a tax credit. |

Provides full benefits at adjusted income of up to $96,000 for married filers ($48,000 for single filers) and provides partial benefit at adjusted income of up to $116,000 ($58,000 for single

filers). |

Provides full benefits at adjusted income of up to $96,000 for married filers ($48,000 for single filers) and provides partial benefit at adjusted income of up to $116,000 ($58,000 for single filers). |

Capped at adjusted income of $80,000 for single filers and $160,000 for married filers. |

Students who do not meet the Hope tax credit’s academic requirements (such as those who already hold a degree or are only taking one course per term) can qualify for the Lifetime Learning tax credit. This program, which has the same income limits as the Hope credit, provides a tax credit equal to 20 percent of fees and is available for an unlimited number of years. Finally, those not claiming the credits may be eligible for a tax deduction of up to $4,000 of the costs of tuition. Based on 2007 data from CSAC, we estimate that more than 90 percent of CCC students would qualify for either a fee waiver or a full or partial federal tax offset to their fees.

Recommend Raising Fees to Maximize Federal Aid. Maintaining very low fees is an inefficient strategy for preserving affordability. While needy students are already shielding from fees through the BOG waiver program, low fees deliver high state subsidies to middle–income and wealthy students—most of whom would receive substantial, if not full, fee refunds from the federal government. California, which charges only $600 for a full–time student, is one of the only states that does not take full advantage of these federal funds. In effect, the state is paying for costs that the federal government would otherwise pay and does pay for all other states. Thus, a low fee policy actually works to the disadvantage of the state.

For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature increase CCC fees as part of its budget solution. An increase to $30 per unit (from $20 per unit) would mean that a full–time student taking 30 units per academic year would pay $900. The annual cost to the same student at $40 per unit would be $1,200. Either way, students taking advantage of the Hope tax credit would qualify for a full fee refund. Higher fees, to be charged only to middle–income and wealthy students, would generate roughly $120 million in additional revenue for CCC at $30 per unit, and $225 million in additional revenue at $40 per unit. (Even at this higher amount, CCC fees would still be the lowest in the country.) The federal government, in turn, would fully or partially reimburse fee–paying students. These additional fee revenues would effectively backfill a reduction in General Fund support for CCC, which would help mitigate the impact on student service levels.

We recognize that some students (probably less than 10 percent of total CCC students) do not qualify for any state or federal financial assistance due to their high–income level, and thus would have to pay the full fee. It is possible that some students who would have enrolled in community college courses at $20 per unit will not enroll when the fee is raised. Because these students by definition are not financially needy, their decision not to enroll should not be considered a denial of access, but rather a choice they make about the benefit they will receive from community college classes. Consequently, affordability and access for CCC students is preserved even with a fee increase.

Funding to Educate Students About Federal Aid Opportunities. In 2003–04 and 2004–05, in conjunction with enacted CCC fee increases, the state provided CCC with significant new outreach funding to help educate students about federal and state financial aid. The Governor’s 2009–10 budget proposal maintains this outreach funding at its current–year level of $37 million. These funds are to be used explicitly for individual financial aid counseling and a statewide media campaign that makes students aware of financial aid opportunities available to them. Despite this funding, relatively few students take advantage of the federal tax credit/deduction programs. For example, according to the CSAC, only about 10 percent of CCC students in the 2006 tax year claimed the Hope or Lifetime Learning tax credits. The primary reasons given by students who did not take the credit is that they were not aware of the credit or did not know if they qualified. Recognizing that students need to be more aware of federal tax opportunities, and may require additional assistance in determining their eligibility for them, the Legislature may want to consider setting aside a small portion of funding generated by any fee increases (such as $10 million) for purposes of outreach and technical assistance to students.

Financial Aid Program Reductions

As Figure 14 shows, the Governor’s budget includes four reduction proposals for Cal Grant programs. In total, these proposals provide an estimated $87.5 million in savings, which would fully offset projected cost increases. Below, we describe each proposal and recommend the Legislature reject all of them.

Figure 14

Governor’s 2009-10 Financial Aid Proposals |

(In Millions) |

|

|

2008-09 Adjusted Base, All Financial Aid Programs |

$948.3 |

Routine program cost increasesa |

$87.5 |

Eliminate new competitive awards |

-52.9 |

Decouple grants from fee increases |

-16.6 |

Reduce awards for private college students |

-11.0 |

Freeze income eligibility ceilings |

-7.0 |

2009‑10 Proposed Costs, All Financial Aid Programs |

$948.3 |

|

a Growth in number and size of awards. |

Decoupling Cal Grants From Fees

Proposal Would Sever Link Between Fees and Cal Grants. The Governor’s budget proposes to end the statutory requirement to raise Cal Grant awards to fully offset the cost of UC and CSU fee increases for grant recipients. This change would save $16.6 million in 2009–10. Among the Governor’s financial aid proposals, decoupling Cal Grants from fee increases would have the greatest potential long–term effect on affordability. Chapter 403, Statutes of 2000 (SB 1644, Ortiz), restructured the Cal Grant programs into an entitlement for recent high school graduates and community college transfers, and established a competitive grant program for other needy students. For both programs, the statute sets the award amount for students attending UC and CSU equal to their systemwide fees (plus a subsistence award for Cal Grant B recipients).

Governor’s Proposal Fails to Protect Needy Students From Fee Increases. Holding Cal Grant recipients harmless from the effects of fee increases in this way has been a key part of the state’s affordability strategy in recent years. The Governor’s budget proposal breaks this link between Cal Grants and fees at UC and CSU. Proposed provisional language in the 2009–10 Budget Bill overrides the statutory fee levels, replacing them with specified award amounts that cover about 60 percent of proposed fee increases at UC and CSU. This modification would require Cal Grant recipients, who by definition are financially needy, to absorb a portion of fee increases (or find other aid). Over time, this could make the universities financially inaccessible to a number of qualified students.

Reject Proposal to Disconnect Cal Grants From Fees. We recommend, therefore, that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed savings of $16.6 million in Cal Grants. Preserving the linkage of Cal Grants with fees will help to ensure that the fee increases do not limit access to higher education.

Eliminating Competitive Cal Grant Program

Governor Proposes to Eliminate Awards for Nontraditional Students. The Governor proposes to eliminate new competitive Cal Grant awards for a savings of $52.9 million. The Legislature created the competitive award program in 2000 with the passage of Chapter 403, recognizing that not all needy students would be eligible for the Cal Grant entitlement. About 22,500 new grants are awarded annually under this program. Students served by the competitive program are older (generally several years past high school), and are more likely to attend a community college. Many have experienced challenges that make it more difficult for them to pursue education beyond high school. Award criteria include parents’ education levels, household status, and characteristics of the high school attended. Beyond that, competitive award recipients share many similarities with entitlement recipients. Both programs serve very low–income, financially needy students. Both serve academically successful students—in fact, competitive program recipients have higher average grades than those in the entitlement program (see Figure 15).

Figure 15

Cal Grant Recipient Characteristics |

2007‑08 Award Cycle |

Averages |

Entitlement

Programa |

Competitive

Program |

Age |

18 |

30 |

Income |

$28,771 |

$14,895 |

GPA |

3.10 |

3.27 |

Family size |

4.1 |

3.0 |

|

a High school component only. |

Source: California Student Aid Commission. |

Maintain Competitive Awards. The Governor’s budget does not offer a programmatic rationale for eliminating the competitive program while maintaining the entitlement program. The competitive Cal Grant program serves a distinct population of college–going students not specifically served by other state financial aid programs, and is an important part of the state’s financial aid system. We recommend, therefore, that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed reduction of $53 million in the competitive Cal Grant program.

Reducing Private College Cal Grant Awards

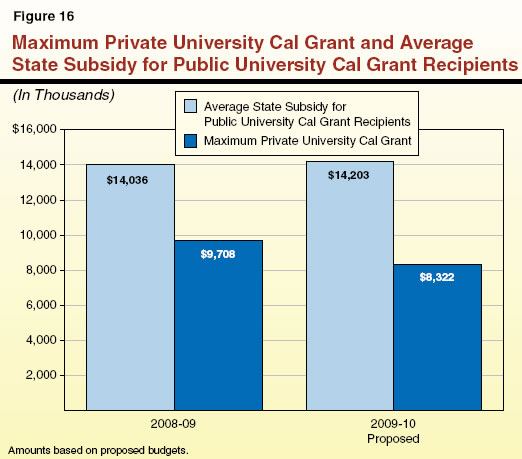

The administration’s proposal includes a reduction of about 14 percent (from $9,708 to $8,322) in the maximum Cal Grant amount for students attending private colleges and universities in California. This reduction would save about $18 million.

Private University Cal Grants Increase Student Choice and Access. Private institutions in California—including independent nonprofit universities such as Stanford and the University of Southern California, as well as for–profit educational institutions such as the University of Phoenix—are an important part of the overall capacity of the state to ensure access to higher education. The State Constitution prohibits direct support to private entities. However, the state has long provided grant support to students who attend private universities—promoting student choice and redirecting some enrollment demand away from the public segments. In fact, the original Cal Grants created in 1955 to accommodate students on the G.I. Bill were only for private college students—because there were no enrollment fees at the public universities.

Private Grants Cost State Less Than Public University Student Subsidies. Prior to 2001–02, the state had a longstanding statutory policy that linked the maximum Cal Grant for financially needy students attending private institutions to the average General Fund cost of educating a financially needy student at UC and CSU. When the Cal Grant entitlement was created in 2000, this policy was replaced with a new provision linking the maximum private–student award to whatever amount was specified in the annual budget act. Since then, the maximum award was maintained at its 2000 level ($9,708) for three years, reduced to $8,322 in 2004, and restored to $9,708 in 2006.

In 2008–09, the maximum Cal Grant awarded to students attending private institutions is about 30 percent lower than the average subsidy the state provides to needy students attending public universities. As shown in Figure 16, the reduced level proposed by the Governor would be about 40 percent below the average public–student subsidy. Yet, independent colleges, which serve most of the students with private college Cal Grants, serve students from relatively low–income families, and have relatively high degree completion rates, compared with UC and CSU.

Proposal Would Shift Enrollment Demand to Public Universities. Further reduction of support for students at private institutions is likely to result in more students seeking admission to the public universities. This would cause additional enrollment pressure on UC and CSU, even as the administration’s budget proposal assumes a year–to–year decline in enrollment at the public universities.

Maintain Private University Cal Grants at Current Level. For the above reasons, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed reduction of the maximum Cal Grant for students at private institutions.

Freezing Income Eligibility Level For Cal Grants

Governor Proposes to Freeze Income Ceilings for Cal Grant Eligibility. The Governor’s budget proposes to keep income eligibility limits for Cal Grants in 2009–10 at the current levels. This measure would save about $7 million.

Income and asset ceilings for Cal Grant programs were established in Chapter 403, with a requirement that CSAC annually adjust them for the change in the state’s per capita personal income. This permits income ceilings to keep pace with the earnings of Californians, so that roughly the same proportion of students and families will meet the eligibility requirements from year to year. The current income ceiling for a family of four is $76,400 for Cal Grant A, which provides fee coverage, and $40,200 for Cal Grant B, which includes fee coverage and a subsistence award. The 2009–10 ceilings for a family of four would increase by 4.3 percent (to $79,700 and $41,900, respectively) with the statutory adjustment. Freezing income ceilings at current levels would reduce the number of grants awarded by about 2,000, or 4 percent, compared with the number the commission would award under adjusted limits.

Reject Proposed Change to Income Limits. Earlier, we discussed how the state’s policies on fees and financial aid can work together to maximize affordability for both students and the state. This can be accomplished by maintaining existing financial aid programs to offset fee increases for needy students. The Governor’s proposal to reduce eligibility for grants while increasing fees, in contrast, would harm affordability for needy students. We recommend, therefore, that the Legislature reject the administration’s proposal to freeze income ceilings.

Other Options for Cost Savings

Options to Control Financial Aid Costs Are Limited. The primary Cal Grant program is an entitlement program, for which the state cannot specifically limit the number of available awards to reduce costs. Instead, it can reduce the award amount, as the administration proposes by decoupling awards from fees; or it can make it harder to qualify for awards by altering financial and academic eligibility criteria, as the administration proposes by freezing income ceilings. The criteria can be adjusted to strike a balance between ensuring that awards go to students with financial need and academic merit, while keeping the cost of awards in line with available funding.

Adjusting Academic Eligibility. In a list of budget savings options our office released in November, we included adjusting academic eligibility criteria for Cal Grants. We estimated that raising the minimum grade point average (GPA) requirement for Cal Grant B from 2.0 to 2.5 would save approximately $11 million. The effect on college degree production would be minimal, because students with GPAs below 2.5 have markedly lower program completion rates. For example, of CSU students admitted to the university in 2001, less than one quarter of those with GPAs of 2.25 or less have graduated, compared to nearly one third with GPAs of 2.5, and over 70 percent of students with GPAs of 3.25 or higher.

Financial Needs Assessment. Other changes to eligibility criteria could better target aid to those with the greatest financial need. For example, a needs analysis process, such as the one used for federal aid programs, would account for factors other than income, such as the number of children in college, to determine financial need.

Savings Versus Reduced Affordability. Any combination of changes to eligibility criteria designed to generate savings will, by definition, reduce affordability for some students. There are trade–offs associated with different changes to the criteria. For example, the Governor’s proposed income restriction would affect a limited number of students and families at the highest income levels of Cal Grant recipients, but would deny grants to some students with high academic merit. Likewise, our GPA restriction option may preserve aid to those most likely to remain in college and complete programs, but could disproportionately affect low–income or underrepresented minority students. Replacing income criteria with needs analysis could result in better targeting to needy students, but may be more difficult for families to understand.

Maintaining Affordability

Students Face Increased Barriers to Higher Education. Students applying for college in 2009–10 face considerable uncertainty about access and affordability. Because of enrollment management strategies discussed elsewhere in this report, students are less likely than in recent years to be admitted to the campus of their choice. Affordability is a growing concern as fees continue to increase while ability to pay has diminished for many families. The value of home equity and college savings plans has declined due to a steep downturn in housing and financial markets. Federal education loans remain available, but the market for private loans, which many students use to supplement or replace federal loans, is extremely tight. The proposed changes to Cal Grant amounts and eligibility add to the uncertainty. Many students will have to make their college decisions before the budget and related legislation are enacted, without knowing whether they will qualify for state financial aid programs.

State Should Maintain Affordability Strategy. It is especially important to preserve the structure of the state’s financial aid system when many other factors that affect access and affordability are uncertain. If the Legislature decides to seek a greater contribution from higher education programs to balance the state’s budget, we suggest that additional fee increases, combined with targeted financial aid increases, would best meet the objective of maintaining college affordability for students and the state. If the Legislature decides to reduce support for financial aid, we suggest that more targeted reductions, such as changes to eligibility criteria, are preferable to broad reductions, such as decoupling Cal Grant amounts from fees, or eliminating entire programs. Furthermore, we suggest that the Legislature consider adjustments other than income ceiling changes. Raising the GPA requirement and using a direct measure of financial need are two options that would link eligibility directly to state objectives—helping students with academic merit and financial need—and better target the state’s investment.

Return to Higher Education Table of Contents, 2009-10 Budget Analysis SeriesReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2009-10 Budget Analysis Series