December 23, 2009

Pursuant to Elections Code Section 9005, we have reviewed

the proposed constitutional and statutory initiative related to local government

revenue raising and the use of various state and local resources (A.G. File No.

09‑0071, Amdt. #1-S).

Background

Sales Tax

Currently, local governments (cities and counties)

receive a portion of the existing 8.25 percent sales and use tax revenues. (Of

this rate, 1 percent is temporary and will expire at the end of 2010-11.) In

addition, local agencies may impose a higher sales tax rate in their

communities, subject to the approval of their local voters. The Constitution's

voter approval threshold depends on how the tax proceeds would be used.

Specifically, if the local government would use the tax proceeds for:

-

Special or designated purposes, the tax requires

approval by two-thirds of local voters.

-

General purposes, the tax requires approval by a

majority of local voters.

The Constitution allows cities and counties to share

sales tax revenues with other cities and counties if the sharing agreement is

approved by a majority of local voters or two-thirds of the affected governing

bodies.

Property Tax

The Constitution establishes a 1 percent maximum base

property tax rate on real property and directs counties to collect these tax

revenues and allocate them to local governments (cities, counties, special

districts, redevelopment agencies, schools, and community colleges) according to

law. While the Legislature may modify property tax allocation laws, the

Legislature generally may not do so if it would decrease the total countywide

share of property taxes allocated to cities, counties, and special districts. An

exception to this provision is known as a "Proposition 1A (2004) suspension,"

after the measure that established this procedure.

Proposition 1A

(2004) Suspension. No more

than twice in ten years, during a severe state fiscal hardship, the Legislature

may reduce city, county, and special district property taxes—and increase school

property taxes. Within three years, the Legislature must repay city, county, and

special districts for their reduced property tax revenues.

In 2009, the Legislature enacted a

Proposition 1A suspension, shifting 8 percent of every city, county, and special

district's 2008-09 property taxes to educational agencies—for a total of

$1.9 billion in shifted revenue. The state must repay each local government by

June 30, 2013.

Tax Increment

City and county redevelopment agencies may create

"project areas" in blighted, urban areas. After a redevelopment agency creates a

project area, it receives all the growth in property tax revenues (called the

"tax increment") generated in the area. Other local agencies serving the project

area continue to receive the amount of property taxes they received before the

agency created the project area.

To partially mitigate the fiscal effect of redevelopment

on other local agencies, state law requires most redevelopment agencies to "pass

through" a portion of their tax increment to other agencies serving the project

area. In addition to these ongoing pass-through obligations, the state

periodically has required redevelopment agencies to make payments to schools.

Current law, for example, requires redevelopment agencies to contribute to

schools $1.7 billion in 2009-10 and $350 million in 2010-11.

Transportation Funding

The state currently charges a sales tax on the purchase

of gasoline. These sales tax revenues are required to be used for specified

transportation purposes, including local street and road improvements, projects

that expand capacity on the state's highway and transit systems, and transit and

rail operations. A portion of these revenues is deposited into the Public

Transportation Account, with the rest of the revenues going to the General Fund.

The Constitution requires that the gasoline sales tax

revenues deposited into the General Fund be transferred to the Transportation

Investment Fund (TIF). Over the past five years, this transfer has averaged

roughly $1.4 billion per year. Of these revenues, 20 percent are dedicated to

mass transportation purposes, and 40 percent are allocated to the state's

transportation capital improvement program. The other 40 percent are given to

cities and counties for local street and road maintenance and improvement. Under

certain conditions, the Constitution allows this transfer to be suspended up to

two times over a ten-year period. Suspended amounts, however, must be repaid

with interest within three years.

Proposition 98

Adopted by the voters in 1988 and amended in 1990,

Proposition 98 establishes a set of formulas that are used to annually calculate

a minimum funding level for K-12 school districts and the community colleges.

This funding level is met using state General Fund dollars and local property

tax revenues.

Proposal

This measure amends the Constitution to (1) authorize

county voters to approve—by a majority vote—new sales taxes under certain

conditions and (2) constrain the state's authority to redirect certain state and

local resources. We discuss these changes below.

Majority Approval of Sales Tax Measures

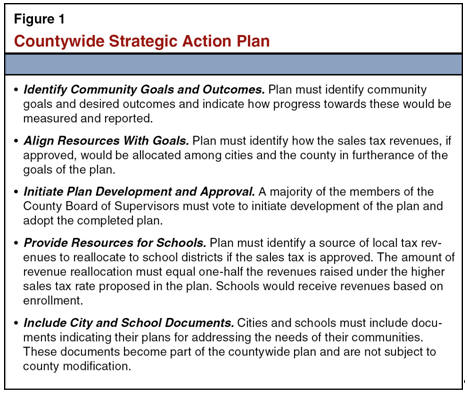

Under the measure, a majority of county voters could

impose a higher local sales tax rate of up to one cent, based on a

county-approved "countywide strategic action plan" as defined by the measure.

(Figure 1 summarizes the required elements of this plan.) The new sales tax

revenues would be allocated to cities and the county pursuant to the plan.

Cities and the county, in turn, would be required to shift to school districts

an amount of revenues equal to one-half of the revenues they receive under the

new sales tax. Cities and counties could shift any tax revenues to schools to

meet this obligation—sales, property, or other local tax. The additional school

revenues would be allocated to districts within the county based on enrollment

and would not count for purposes of calculating the state's minimum funding

requirement under Proposition 98.

Under the measure, the sales tax would end in ten years,

unless (1) a majority of county voters approved a continuation of the tax or (2)

a majority of the county governing board agreed to dissolve or amend the

countywide strategic action plan earlier.

Limitations on State Authority to Redirect Resources

Property Tax. The measure eliminates the

state's authority to shift property taxes from cities, counties, and special

districts to schools during a severe state fiscal hardship. Under the measure,

the state would maintain responsibility for repaying local governments for the

2009 Proposition 1A (2004) suspension, but could not borrow local funds by

shifting property tax revenues to schools in the future.

Prohibits Borrowing or Redirection of Gasoline Sales Tax Revenues.

The measure prohibits suspending the transfer of gasoline sales tax revenues

from the General Fund to the TIF. This eliminates the state's ability to borrow

these funds for non-transportation purposes.

Other Local Revenues. Under the measure,

the Legislature could not enact new laws that require redevelopment agencies to

use tax increment funds to make payments to schools or other agencies. The

measure also specifies that the Legislature may not reallocate, borrow, or use

revenues from any locally imposed tax.

Fiscal Effects

Under this measure, (1) cities, counties, and schools

would have higher and more stable revenues and (2) state revenues would be lower

in some years than otherwise would be the case. We discuss these fiscal effects

below.

Higher and More Stable Resources for Local Governments

This measure would make it easier for voters to approve

some countywide sales taxes to support city, county, and school programs,

compared to the existing two-thirds vote requirement for special taxes.

As a result, counties probably would propose

more of these measures and voters probably would approve more of them.

California's 2004 election illustrates the potential

effect of setting a majority vote threshold for new sales taxes. During that

year, local governments proposed 48 sales tax increases for special purposes.

Voters approved one-third of them. If the voter approval threshold for these

taxes had been 50 percent, over half of these taxes would have been approved.

While some of the failed tax measures that earned more than 50 percent approval

involved small sums, some were large. For example, the Los Angeles County

half-cent sales tax failed because it was approved by only 60 percent of local

voters. Had the measure passed, it would have raised about $600 million

annually.

The fiscal effect of this measure's

provisions—authorizing majority vote approval for sales taxes to implement

specific countywide plans—would depend on future local government and voter

decisions. If voters in every county approved the maximum sales tax increase,

local government revenues would increase by over $5 billion—including over

$2.5 billion for schools. Alternatively, if the state's ten most populous

counties each approved a one-quarter cent increase, local government revenues

would increase by about $1 billion—including $500 million for schools.

Given (1) the wide

range of services provided by cities, counties, and schools and (2) recent

election experience in which taxes were not imposed because they did not receive

approval by two-thirds of the voters, we expect this measure would result in

major increases in local taxes and spending over time, probably exceeding

$1 billion annually.

More Stable Local Revenues. Given the

number and magnitude of past state actions affecting local tax revenues and

resources, this measure's restrictions on state authority to enact such measures

in the future would have potentially major beneficial fiscal effects on

noneducation local governments. For example, the state could not enact measures

that require redevelopment agencies to pass through more revenues to schools.

Similarly, the state could not borrow or

redirect gasoline sales tax revenues as part of a state budget solution.

In these cases, this measure would result in noneducation local government

resources being more stable—and higher—than otherwise would be the case. The

magnitude of increased local resources associated with these provisions is

unknown and would depend on future actions by the state. Given past actions by

the state, however, this increase in local resources could be billions of

dollars in some years. These increased local resources could result in higher

spending on local programs or decreased local fees or taxes.

Lower Resources for State Programs

Under the measure, the state could not: (1) use

redevelopment or other local funds to support education or (2) borrow

or redirect property tax or gasoline sales

tax revenues as part of a state budget solution. As a result, the state

would need to take alternative actions to balance the state budget in some

years—such as increasing taxes or decreasing spending on state programs. Given

current and previous actions by the state, we estimate that this decrease in

state fiscal authority could reduce state resources by billions of dollars in

some future years.

Summary of Fiscal Effects

The measure would have the following major fiscal

effects:

-

Major increases—probably over $1 billion—in annual

city, county, and school revenues and spending, depending on local voter

approval of future tax proposals.

-

Significant constraints on state authority over city,

county, special district, and redevelopment agency funds. As a result,

higher and more stable local government resources, potentially affecting

billions of dollars in some years. Commensurate reductions in state

resources, resulting in major decreases in state spending and/or increases

in state revenues.

Return to Propositions

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page