November 13, 2013

Pursuant to Elections Code 9005, we have reviewed the proposed

statutory initiative

(A.G. File No. 13‑0021) relating to school payments.

Background

State Law Sets Forth “5‑5‑9” Payment Schedule.

School districts, county offices of education, and charter

schools (hereafter collectively referred to as “schools”) receive

general purpose funding from a combination of state General Fund and

local property tax revenues. Schools with lower local property tax

revenues generally receive higher state General Fund payments. State law

sets forth that General Fund payments to schools are to be made using a

5‑5‑9 schedule, with 5 percent of annual payments made in July and

August and 9 percent of total payments made each month thereafter.

(State law establishes a somewhat different payment schedule for small

districts that rely more heavily on local property tax revenues.)

Despite state law’s 5‑5‑9 provisions, schools have not received funding

according to this schedule due to payment deferrals adopted in recent

years.

State Has Used Intra-Year Deferrals to Help Manage Cash

Flow. The fiscal year of the state and most public

entities begins on July 1. Because the state generally disburses the

majority of General Fund dollars in the first half of the fiscal year

but collects the majority of General Fund receipts in the second half of

the fiscal year, the state routinely runs monthly cash flow deficits

through the first half of the fiscal year. To address this regular

imbalance of receipts and disbursements, the state’s General Fund

routinely borrows from other state funds, as well as bond market

investors. Such “cash-flow loans” typically are paid back with interest

during the latter half of the state’s fiscal year. The state’s cash flow

problems became particularly problematic from 2008‑09 through 2011‑12,

when the state’s budgetary problems created larger cash flow deficits in

certain months. In these years, the Legislature provided the executive

branch with more flexibility to delay up to $6 billion in payments to

schools, universities, and local governments from the beginning of the

fiscal year to the end of the fiscal year. In recent years, as the

state’s cash situation has improved, the state has not implemented

intra-year deferrals.

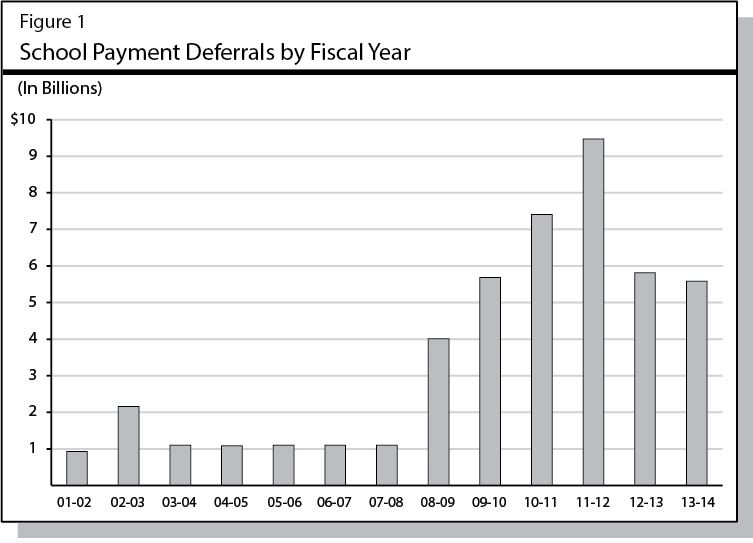

State Has Used Inter-Year School Deferrals for One-Time

Budgetary Savings. In addition to using intra-year

deferrals for short-term cash flow, the state has used inter-year

deferrals for budgetary savings. As with intra-year deferrals, the state

relied heavily on inter-year deferrals during the recent recession. As

shown in Figure 1, over this period the state delayed an increasing

amount of school payments into the subsequent fiscal year. In 2008‑09,

for example, the state deferred $2 billion from February 2009 (the

2008‑09 fiscal year) until July 2009 (the 2009‑10 fiscal year). This

decreased 2008‑09 General Fund costs by $2 billion, resulting in

one-time budgetary savings (and a short-term cash flow problem for

districts). Because the state made the late payment in 2009‑10, it

realized no ongoing savings. To avoid incurring additional one-time

costs in 2009‑10, the state continued deferring the February-to-July

deferral in future years. School deferrals continued to be a principal

tool for addressing the state’s budgetary problems such that, by

2011‑12, $9.5 billion in school payments were made late. The state began

to pay down its existing school deferrals in 2012‑13, when state

revenues increased significantly. For example, the state eliminated the

February-to-July deferral and returned the payment to its original

schedule, incurring $2 billion in one-time costs. As of the 2013‑14

budget plan, $5.6 billion in inter-year school deferrals remain

outstanding.

Proposal

Eliminates All Existing School Payment Deferrals.

Beginning in 2015‑16, the measure requires the state to use the

5‑5‑9 schedule for making monthly General Fund payments to schools,

thereby eliminating all existing payment deferrals. Moving forward,

school payments could be delayed by no more than 30 days and could not

extend across the fiscal year. The measure allows the state to implement

longer school payment deferrals only through a

voter-approved initiative or legislation that receives three-fourths

approval from both houses of the Legislature. The initiative would

eliminate the schedule for payments in the 2014-15 fiscal year after

November 2014. It is unclear how payments for the remainder of the

2014-15 fiscal year would occur.

Fiscal Effects

Effects on State Government

One-Time State Costs to Eliminate Deferrals.

Eliminating all existing school payment deferrals would create

one-time state costs of up to $5.6 billion in 2015‑16. (The exact cost

would depend on the amount of deferrals outstanding at the end of

2014‑15.) This additional cost would require the state to spend less on

other education programs, spend less in other areas of the budget,

implement budgetary deferrals for other programs, use budget reserves,

and/or raise additional revenues to accommodate the additional spending.

Reduced State Flexibility to Respond to Future Cash or

Budgetary Problems. The measure also restricts the state’s

flexibility to respond to future budgetary crises. To the extent that

future crises created state cash flow problems, the state would have to

take other actions such as delaying payments to nonschool programs or

increasing the size of its external borrowing. Increasing cash-flow

loans likely would increase the state’s interest costs related to that

borrowing. To achieve budgetary savings, the state would need to rely

more heavily on spending reductions in other areas of the budget,

budgetary deferrals for other state programs, use of budget reserves, or

additional revenues rather than deferring school payments.

Effects on School Districts

One-Time Funds Will Improve School District Cash Flow.

As discussed above, the measure would require the state to

make one-time payments in to schools to eliminate existing payment

deferrals. These funds likely would reduce school borrowing costs and

improve cash flow, but likely would have little effect on ongoing school

spending.

More Predictable Cash Flow for School Districts in Future

Years. Due to the higher threshold required for delaying

state payments, school districts would have greater certainty regarding

their payment schedule in subsequent years. This likely would reduce

school district cash flow problems in future years and could help reduce

school districts’ interest costs related to their own cash-flow (and

infrastructure) borrowing.

Future State Budget Problem Could Result in Deeper Cuts

to School Programs. Because the measure limits the state’s

ability to implement school payment deferrals, the state likely would

rely more heavily on spending reductions to address future budgetary

problems. If the state responds to future budget crises by making

reductions to state programs, the measure could result in programmatic

reductions for schools.

Summary of Fiscal Effects

We estimate the measure would have the following fiscal effects on

state and local governments:

- One-time state costs in 2015‑16 of up to $5.6 billion to

eliminate all existing school payment deferrals.

- Beginning in 2015‑16, more predictable cash flow for schools and

lower school borrowing costs.

- In future years, reduced state flexibility to respond to cash or

budgetary problems.

Return to Initiatives

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page