January 31, 2014

As required by Section 9005 of the Elections Code, this letter

analyzes the proposal

(A.G. File No. 13‑0063) to end the existing State of California and

replace it with six new states, subject to approval of the United States

government. The text of the proposal states that it is an initiative

measure, which would amend the California Constitution and the state’s

Government Code.

Background

California’s Existing Boundaries

History of Current Borders. The current

borders of California are specified in the California Constitution and a

few other state laws. These borders resulted from: (1) an 1848 treaty

with Mexico that ceded California to the United States and (2) the

decision of delegates at California’s 1849 constitutional convention to

set the state’s eastern boundary near the crest of the Sierra Nevada

Mountains and along the Colorado River. Congress and President Fillmore

agreed to admit California to the union as a “free state” as part of the

Compromise of 1850. Proposals to split California into two separate

states were not approved at that time.

Efforts to Split California Since Statehood.

Discussions of splitting California into two or more states

continued after statehood and have emerged periodically ever since. In

1859, the Legislature passed a measure consenting to the separation of

areas south of the Tehachapi Mountains (including Los Angeles County and

San Diego County, among others) into a separate territory or state. The

measure conditioned California’s approval for this split on two-thirds

of Southern California voters agreeing to it. In an election, three out

of four of those voters approved separation. Congress, however, never

acted on the separation plan, so it was never implemented.

Since the early 1940s, some residents of far northern California have

suggested that their counties—along with a few counties in southern

Oregon—separate from the two states to create a new state called

Jefferson. Recently, Boards of Supervisors in Glenn, Modoc and Siskiyou

Counties approved measures supporting separation from California.

Relationship Between Existing State and Local Governments

This measure also contains provisions concerning the relationship

between the existing State of California and its local governments. This

section provides background on those issues.

State Reimbursements for Mandates Imposed on Local

Governments. When the state government mandates that a

local government provide a new program or higher level of service, the

California Constitution generally requires the state to reimburse the

local government. If a new law is determined to be a reimbursable

mandate, the Legislature must fund local government costs for the

mandate, suspend the mandate, or repeal the mandate. Suspending or

repealing the mandate does not eliminate the state’s obligation to

reimburse local governments for any costs incurred in prior years during

which the mandate was active, although doing so allows the state to

defer payments to future years.

Cities and Counties May Adopt Charters.

State law generally defines the roles and responsibilities of cities and

counties. The California Constitution, however, allows cities and

counties to adopt or amend charters—subject to approval by local

voters—that supersede state law on certain issues. Of California’s 58

counties, 14 currently are charter counties, including some of the

largest ones, such as Los Angeles County, San Diego County, and Orange

County. Charter cities generally have authority over their “municipal

affairs.” Although the Constitution does not define municipal affairs,

case law suggests that they include municipal elections, land use and

zoning, contracting, and budgeting. Despite this authority of charter

cities, state laws concerning city municipal affairs may be controlling

if necessary to further a significant statewide interest.

Proposal

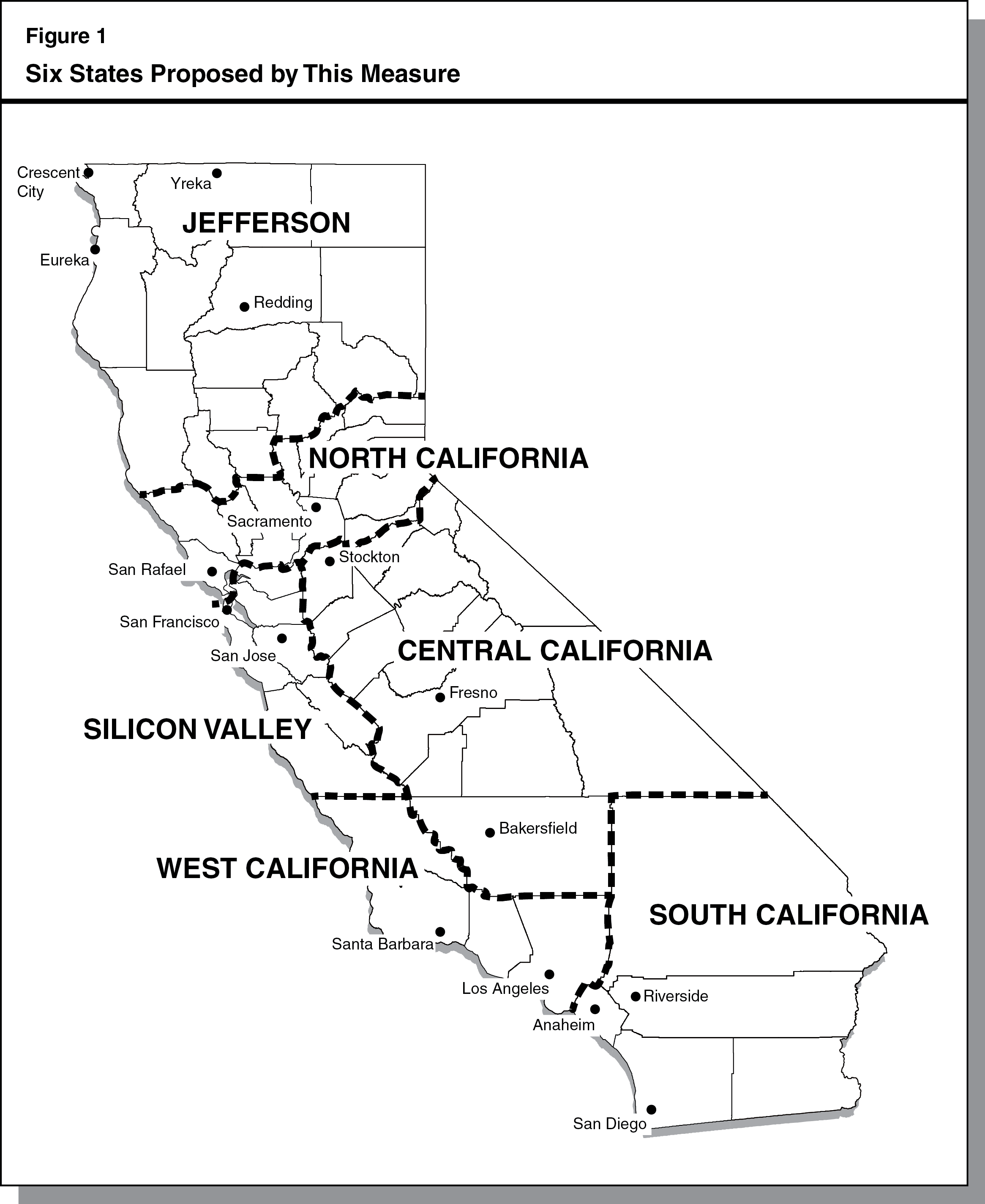

Establishes Process to Split California Into Six New

States. This measure amends the State Constitution to

allow a statute to consent to the splitting of California into two or

more new states. The measure also amends state statutes to provide

California’s legislative consent—pursuant to the relevant section of the

U.S. Constitution—for the creation of six new states within the current

boundaries of California. The measure keeps intact existing county

boundaries and assigns each county to one of the six new states shown in

Figure 1. The measure specifies that the names of the six new states

will be Jefferson, North California, Central California, Silicon Valley,

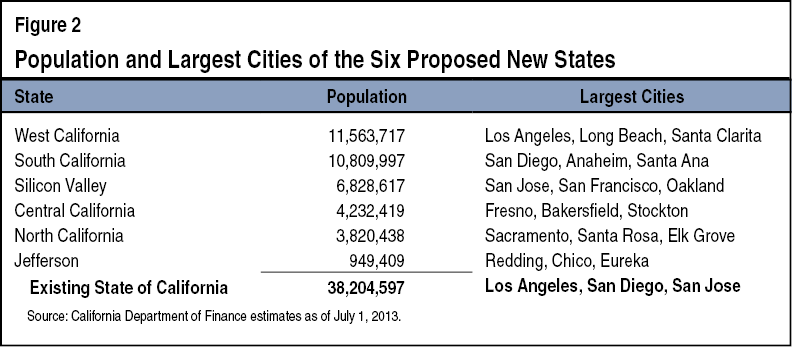

West California, and South California. As shown in Figure 2 (see page

4), West California—including Los Angeles—would be the most populous of

the six states, with a population similar to that of Ohio. West

California’s population would be less than one-third of today’s

California. Jefferson—including the northernmost counties—would be the

least populous of the six states with 1 out of every 40 residents of

today’s California and a total population somewhat smaller than

Montana’s.

Power of Counties Over Municipal Affairs.

Effective immediately upon voter approval of this measure, the

California Constitution would be amended to allow more authority for

charter counties over municipal affairs that now may be controlled by

city governments. In cases where existing county charters do not address

such municipal affairs, voter approval of amendments to those charters

would be required. For example, a county charter could be amended under

this measure to delegate authority over municipal affairs to a regional

association consisting of several counties. In addition, the measure may

be interpreted as prohibiting the state from delaying payment of

reimbursements to counties for state mandates concerning municipal

affairs. These provisions relating to county governments would remain in

effect so long as the State of California continued to exist. If

Congress never approves the proposed plan to split California, these

provisions relating to county governments would remain in place in the

California Constitution.

Process to Implement Proposal

Procedures Specified in the Measure

Under the measure, California’s existing state government would

continue until each new state is organized and established—presumably

including congressional approval—and has its own state constitution in

place. The measure specifies a number of steps that would be undertaken

by local and state officials after approval of the measure.

Creates Board of Commissioners to Guide State Separation

Process. The measure states that a Board of Commissioners

to provide for California’s division would be created “upon enactment of

this section” (which would occur the day after the measure is approved

by voters). The measure provides for 24 commissioners: (1) 12

commissioners to be appointed by the Legislature (six by the State

Assembly and six by the State Senate) and (2) two commissioners chosen

by all of the members of county Boards of Supervisors in each of the six

new states. Each of the 24 commissioners would serve for a “term not to

exceed” two years. (While the measure requires the Legislature’s 12

commissioners to be chosen within six months after Congress approves the

creation of the six new states, it does not prohibit an earlier

selection of commissioners.)

The Board of Commissioners would be required to “settle and adjust

the property and financial affairs” between the existing state and the

six new states. This likely would require disposing of each of the State

of California’s physical and other assets—as well as splitting the

state’s financial and other liabilities—among the six new states. If the

commissioners fail to reach resolution “before the end of their terms,”

the measure states that California’s state debts would be distributed

among the new states based on population and the assets of California

within each new state’s boundaries would become an asset of that new

state. The measure requires the California Legislature to provide

financial and staff resources to the Board of Commissioners as needed.

Process to Reassign Counties Among the Six States.

Through November 15, 2017, the measure would allow any

county—subject to approval of county voters—to adopt an ordinance

allowing it to be reassigned from the state in which it is placed by

this measure to one of the other five proposed states. This could only

occur, however, if the reassigned state’s borders are immediately

adjacent to those of the county in question and if a majority of the

county Boards of Supervisors in the reassigned state approve of the

change.

Congressional Approval for State Split Plan Sought by

January 1, 2019. The measure requires the Governor of

California to transmit the state-splitting proposal to Congress for its

consideration on January 1, 2018. The Governor would be required to

request that Congress act on the proposal by January 1, 2019.

Other Steps Required Before Splitting California

In addition to the steps described above, additional steps would be

required—assuming voters approve this measure—before California could

split into six new states.

Potential Court Challenges. Litigants

likely would bring a variety of challenges to California’s separation in

federal and state courts. These challenges could involve various issues,

including ones related to the distribution of California’s assets and

liabilities, the provision of public services among the six states (some

of which are discussed later in this analysis), and constitutional

issues related to congressional approval of the new states. Court cases

related to California’s split could persist for a long time. Legal

disputes between Virginia and West Virginia, for example, concerning the

latter’s share of state debt lasted for about 50 years after West

Virginia statehood (including several cases before the U.S. Supreme

Court). In addition, a possible suit would concern whether this is an

initiative measure (as the text of this measure states) or a revision of

the California Constitution. A revision is generally broader in scope

than an initiative measure—for example, a change that substantially

alters the basic governmental framework of the state is a revision.

Under the California Constitution, revisions may be proposed only by the

Legislature or a constitutional convention.

Congressional Approval Required. Assuming

voters approve this measure, California would not be split unless the

federal government enacted a law approving the separation. The bill to

create the new states would have to be approved by a majority of the

U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. Finally, the measure

would have to be approved by the President of the United States, unless

his or her veto were overridden by Congress.

Fiscal Effects on State and Local Governments

If approved and implemented in full, this measure eventually would

terminate tax and fee collections and spending by the existing State of

California. A specified process would divide California’s assets and

liabilities among six new states. To the extent that the new states

continue existing local governments, local entities (and the new state

governments) would face a number of budgetary, economic, and other

issues summarized in this section.

The Six States’ Different Income Levels and Tax Bases

At least initially—and perhaps for many decades after their

creation—the six proposed new states would have widely varying income

levels. The varied income levels would have important effects on each

state’s tax base. This section considers the three largest state and

local tax sources: the personal income tax (PIT), sales taxes, and

property taxes.

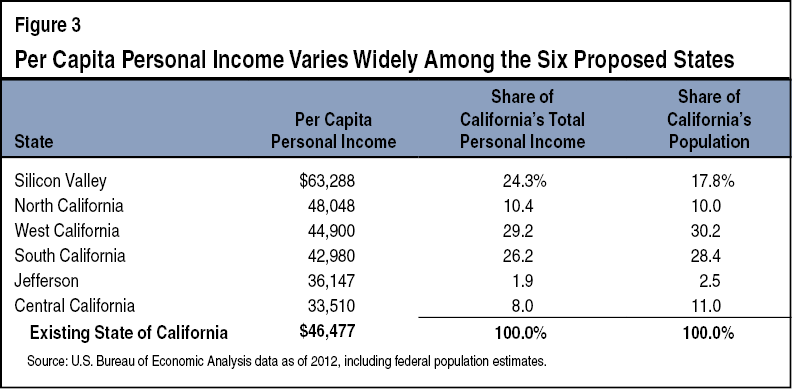

Significant Income Differences Among the Proposed States.

Personal income is a broad measure of the size of the

economy, which includes wages and salaries, proprietors’ income, rental

income, dividends, interest income, and transfer receipts such as

payments by governments to individuals. When measured on a per-person

(or per capita) basis, personal income data can show which areas tend to

have higher-income (generally, wealthier) or lower-income (generally,

less wealthy) individuals and households. As shown in Figure 3 (see next

page), per capita personal income (PCPI) in today’s California is

$46,477, which ranks 12th among the 50 U.S. states. Wealth in

today’s California, however, is disproportionately concentrated among

households in the San Francisco Bay Area, including Silicon Valley,

which benefits from a concentration of technology firms. For this

reason, if California is split into six states as proposed by this

measure, two of the six states (Silicon Valley and North California)

would have PCPI above that of today’s California, while the other four

states would have lower PCPI based on 2012 data.

Silicon Valley’s PCPI—$63,288—currently would rank as the highest

among U.S. states ($3,600 above Connecticut, but still below the

District of Columbia). Central California would rank as a leading

agricultural producer. Its PCPI and that of Jefferson, however, would be

notably lower than the PCPI of the other four new states. Currently,

Central California’s PCPI would rank last among all U.S. states (about

$150 below Mississippi).

The data in Figure 3 assume that no counties reassign themselves to

one of the other states as allowed under the measure. If, for example,

Marin County—just north of the Golden Gate Bridge—opted to join Silicon

Valley instead of North California, Silicon Valley’s PCPI would climb by

about $1,000, while North California’s PCPI would fall below that of

West California.

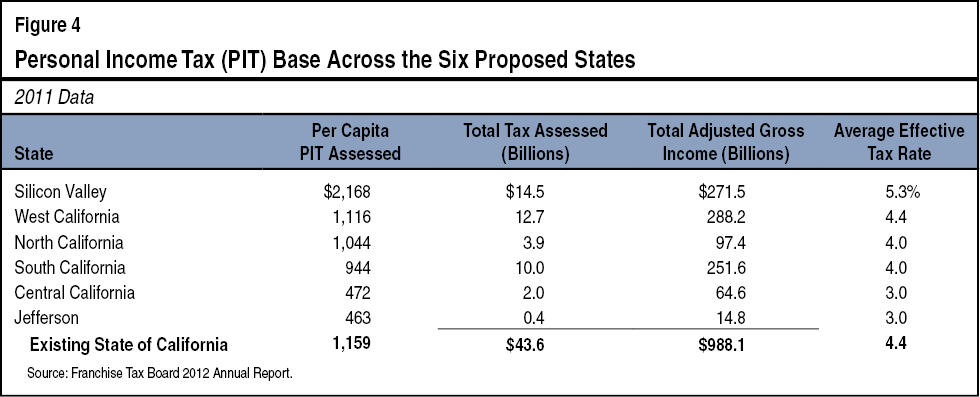

California’s PIT Base Concentrated in Bay Area.

California’s state General Fund provides most state support for

public schools, universities, health and social services programs, and

prisons. Currently, PIT is the primary tax revenue source for state

government, making up about two-thirds of the state’s General Fund

revenues. Today’s California relies upon a progressive PIT rate

structure—one in which higher-income individuals pay a higher effective

tax rate on their income—and taxes capital gains income from stock and

home sales when realized by taxpayers. In 2011, as illustrated in

Figure 4, about 28 percent of the adjusted gross income reported on

state tax returns originated from the proposed Silicon Valley state,

despite it having 18 percent of California’s total population. This is a

direct result of Silicon Valley being a higher-income area than

elsewhere in California. Owing as well to California’s progressive PIT

rate structure—in which higher-income taxpayers pay higher effective tax

rates—Silicon Valley paid one-third of all PIT assessed by California in

2011. Just as Silicon Valley has disproportionately high PIT totals,

Jefferson and Central California have lower PIT totals, with per capita

PIT assessed in those areas far below levels in the other four proposed

states.

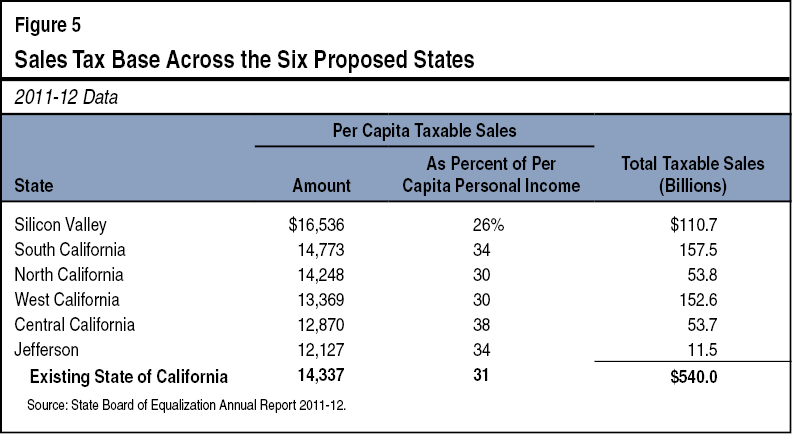

Silicon Valley Leads State in Per Capita Taxable Sales.

The sales tax is the second-largest General Fund revenue

source for the state government and is also a major local government

revenue source. California taxes most physical goods purchased in the

state, but not most services. Currently, the statewide sales tax rate of

7.5 percent generates tax revenue that is divided among state and local

government programs. (Many localities charge an additional rate on top

of the 7.5 percent statewide rate, such that the average sales tax rate

paid by California consumers currently is around 8.4 percent.)

As shown in Figure 5, Silicon Valley leads all of the proposed six

states in per capita taxable sales, while Jefferson and Central

California have less taxable sales per person than the other four

states. Nevertheless, the disparities between Silicon Valley and the

other states are not as great for this measure as they were for per

capita PIT revenues. Part of the reason for this is that lower-income

consumers spend a greater portion of their income on taxable goods. In

Central California—the region with the lowest PCPI—per capita taxable

sales total 38 percent of PCPI, the highest level for this measure of

any of the six proposed states. While South California has ranked fourth

among the six states in the income measures cited previously, it ranks

second in per capita taxable sales as a result of its residents spending

more of their income on taxable goods than any other area except Central

California. In some cases, the data in Figure 5 may be influenced by

“interstate” consumer activity—for example, by a Los Angeles County

(West California) resident purchasing a car, clothes, or large

appliances in the Inland Empire or Orange County (South California).

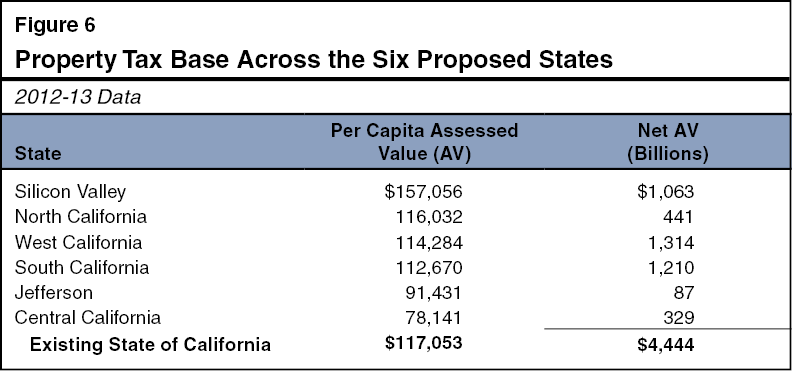

Per Capita Assessed Property Value Highest in Silicon

Valley. Property taxes are a major local government

revenue source and directly influence the existing state budget since

higher distributions of property taxes to schools typically reduce the

amount of money the state must provide to local school districts under

Proposition 98, a state constitutional provision passed in 1988. As

shown in Figure 6 (see next page), the existing California property tax

base is also somewhat concentrated in the Bay Area, with per capita

assessed value (AV) considerably higher in the proposed Silicon Valley

state than in any other region. Per capita AV in Central California and

Jefferson lags the other four states by a considerable margin. Housing

in these two proposed states tends to be less costly than housing in

Silicon Valley and coastal areas in Southern California.

Income and Wealth Differences Would Affect Policy

Decisions. In summary, Silicon Valley would have the

highest income levels of the six proposed states and Central California

and Jefferson would have the lowest, according to the standard economic

measures discussed above. Considering the major taxes that now fund

California governments—personal income, property, and sales taxes—these

disparities in incomes (and related disparities in wealth) translate

into very different tax bases for the proposed states. Mainly because

Silicon Valley residents have higher incomes, they pay more per person

in income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes under the existing

California tax system. By the same token, Central California and

Jefferson residents are, on average, less well-off and pay less per

person for each of these major taxes. The other three proposed

states—North California, West California, and South California—rank in

between. The regional disparities in income and wealth would affect

various fiscal and policy decisions of the six new states.

Issues Concerning Public Schools and Higher Education

According to Census data, California governments spend over

$100 billion per year on education, more than on any other area of

public services. The large majority of this money goes to fund public

schools and community colleges. Most of the rest goes to fund the

state’s two university systems, the University of California (UC) and

the California State University (CSU). The different tax bases and other

characteristics of the six states would force each to make major

decisions about these areas of public spending.

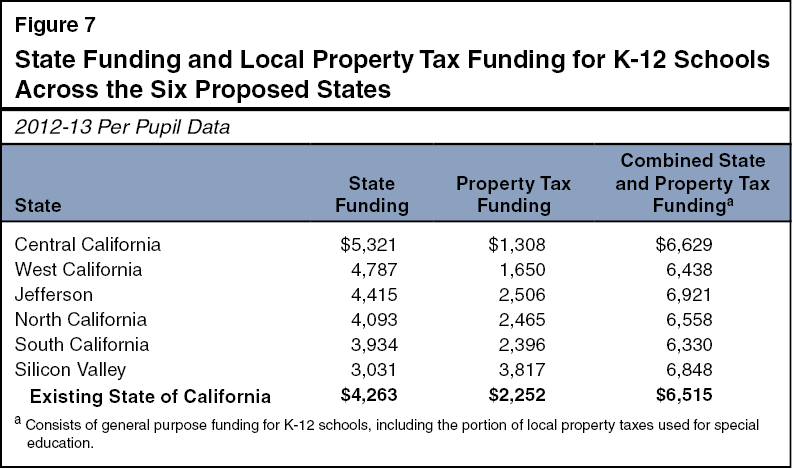

Different Regions Rely Differently on State Aid for

Schools. Figure 7 (see next page) shows the level of

per-pupil state and local property tax general purpose funding for

public schools as of 2012‑13. (This excludes certain categories of

federal and other funding.) By this measure, combined state and local

property tax funding ranged from an average of $6,330 per pupil in South

California to $6,921 in Jefferson—a less than 10 percent spread, despite

the income and wealth disparities among the regions. The reason for the

relatively small disparity in per-pupil school funding is that the

existing State of California provides state funding to supplement

resources of districts that receive relatively less in property taxes.

In other words, state funding serves to equalize disparities in property

tax wealth across school districts and regions. As a result of the

state’s funding policies, the two proposed states with the lowest level

of per-pupil property taxes—Central California and West

California—receive more state funding per pupil than the other four

states. By contrast, Silicon Valley—in which school districts receive

far more property taxes per pupil—receives far less in state funding per

student.

Decisions Concerning School Funding. As

shown in Figure 7, Silicon Valley’s schools already are funded

significantly from local property tax sources. As described earlier,

state tax revenues of the existing California are paid

disproportionately by Bay Area residents, such that a significant

portion of their state tax payments essentially is used to subsidize

funding for schools and other public services in lower-income regions

like the Central Valley. If Silicon Valley becomes a state, its state

tax revenues presumably would not be used to fund Central Valley, Los

Angeles, and other schools with less property tax funding. By contrast,

some of the other proposed states—especially Central California and West

California—could find themselves in the opposite situation, no longer

able to benefit from a state tax system disproportionately funded by

California’s higher-income regions.

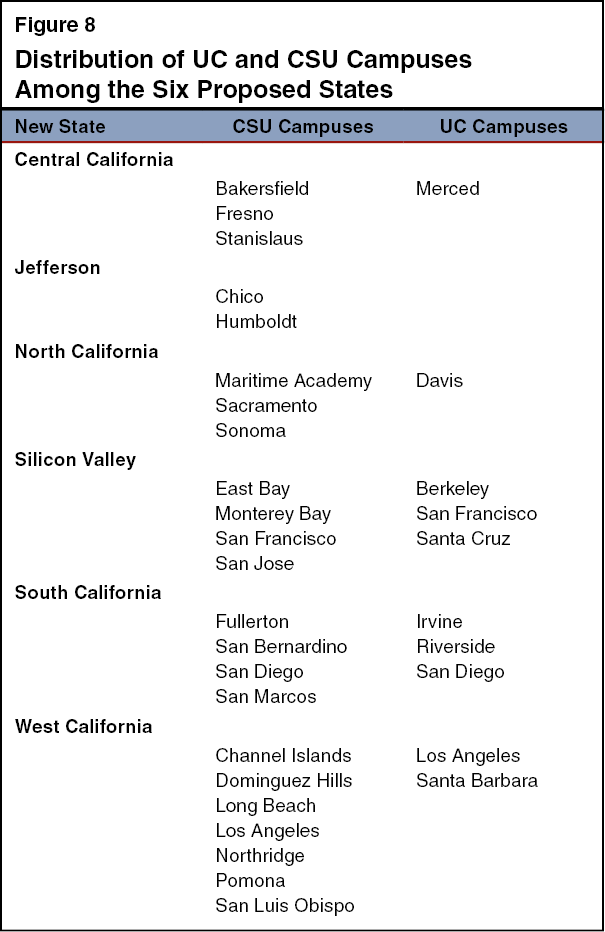

Higher Education Across the Six States.

California’s public higher education system consists of 72 local

community college districts, the 23 campuses of the CSU system, and the

10 campuses of the UC system. If California splits into six new states,

each new state’s leaders could face a variety of choices about how to

fund and organize the campuses in their jurisdictions (see Figure 8,

next page).

As currently stands, Central California and Jefferson do not have a

full array of professional programs, such as law and medical schools, at

public universities within their boundaries. Federal research funding

also is not evenly distributed among the six proposed states. Finally,

because the state General Fund currently provides a much larger

per-student subsidy at UC, the proposed states with more UC

campuses—such as Silicon Valley and South California—might have more

costly higher education systems, at least initially.

A 1992 State Assembly report on splitting California suggested that

the university systems—along with a few other state functions—could be

reorganized as multistate entities. Establishing multistate universities

would be an option for the Board of Commissioners (the entity

established to dispose of California’s assets and liabilities) and the

new states’ leaders, but multistate university systems would require

choices to be made—both initially and over time—about the appropriate

share of funding to be provided by each of the six proposed states,

among other issues.

Issues Concerning Health and Social Services Programs

Key Health and Social Services Programs Across the Six

States. Currently in California, state and local

governments jointly fund various health and social services programs—in

some cases, with additional support provided by funding from the federal

government. According to Census data, state and local governments in

California now spend around $80 billion per year on public welfare and

health programs, primarily to assist poor and disabled individuals in

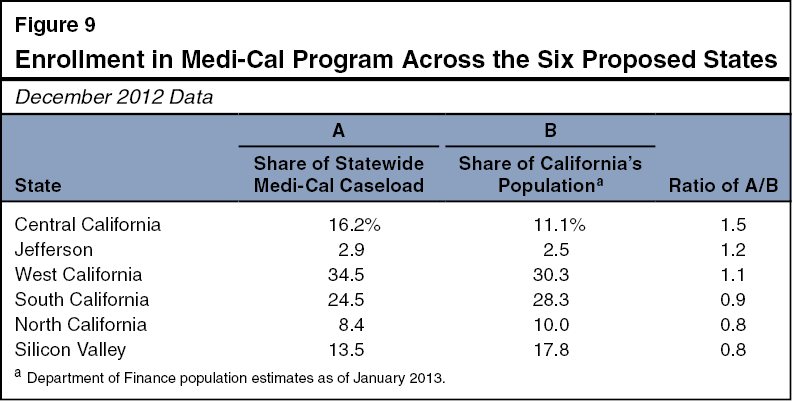

the state. Figure 9 shows that, in 2012, the caseload of the Medi-Cal

Program—the state’s primary health care program for the poor—was not

distributed evenly across the six proposed states. For example, Central

California had 16 percent of the statewide Medi-Cal caseload, or about

1.5 times its 11 percent share of California’s statewide population.

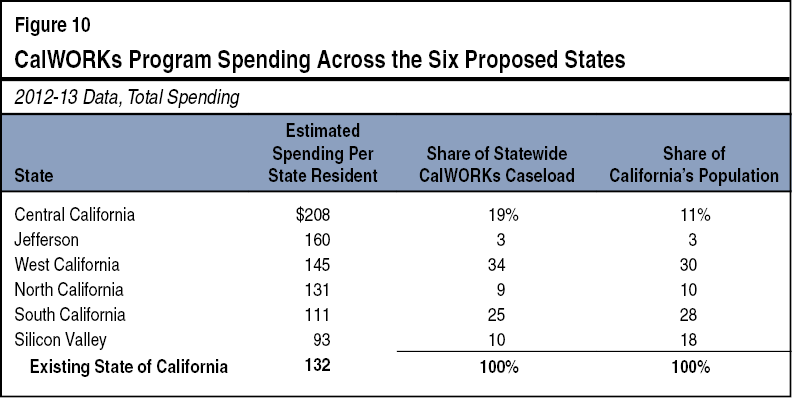

Figure 10 (see next page) shows that per-resident spending on the

California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program—the

program that provides cash assistance and welfare-to-work services to

very low-income families—is considerably higher in Central California

than the other proposed states.

Changes in the socioeconomic status and policies of the new states

could increase the level of federal funding, particularly for the poorer

new states. Such changes in federal funding could offset part or most of

any change in state and local funding for certain health and social

services programs.

Issues Concerning Water Supply and Delivery

Complex Water System in Today’s California.

California’s existing system of water supply and delivery is

one of the most complex in the world. One reason for this complexity is

that water does not naturally appear in California where demand is

highest. Much of California’s rainfall and snowfall occurs in the north,

while much of the demand for water is in the south. Water flowing

through the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys—originating in part from

the Sierra Nevada snowpack—is the main source of water into the

Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. Two major California water delivery

projects, the State Water Project (SWP) and the federal Central Valley

Project, supply all or part of the drinking water for most Californians

from these sources. In addition, at least one quarter of the state’s

cropland uses water that flows through the Delta, and various habitats

and species rely on the flow of water into and through the Delta.

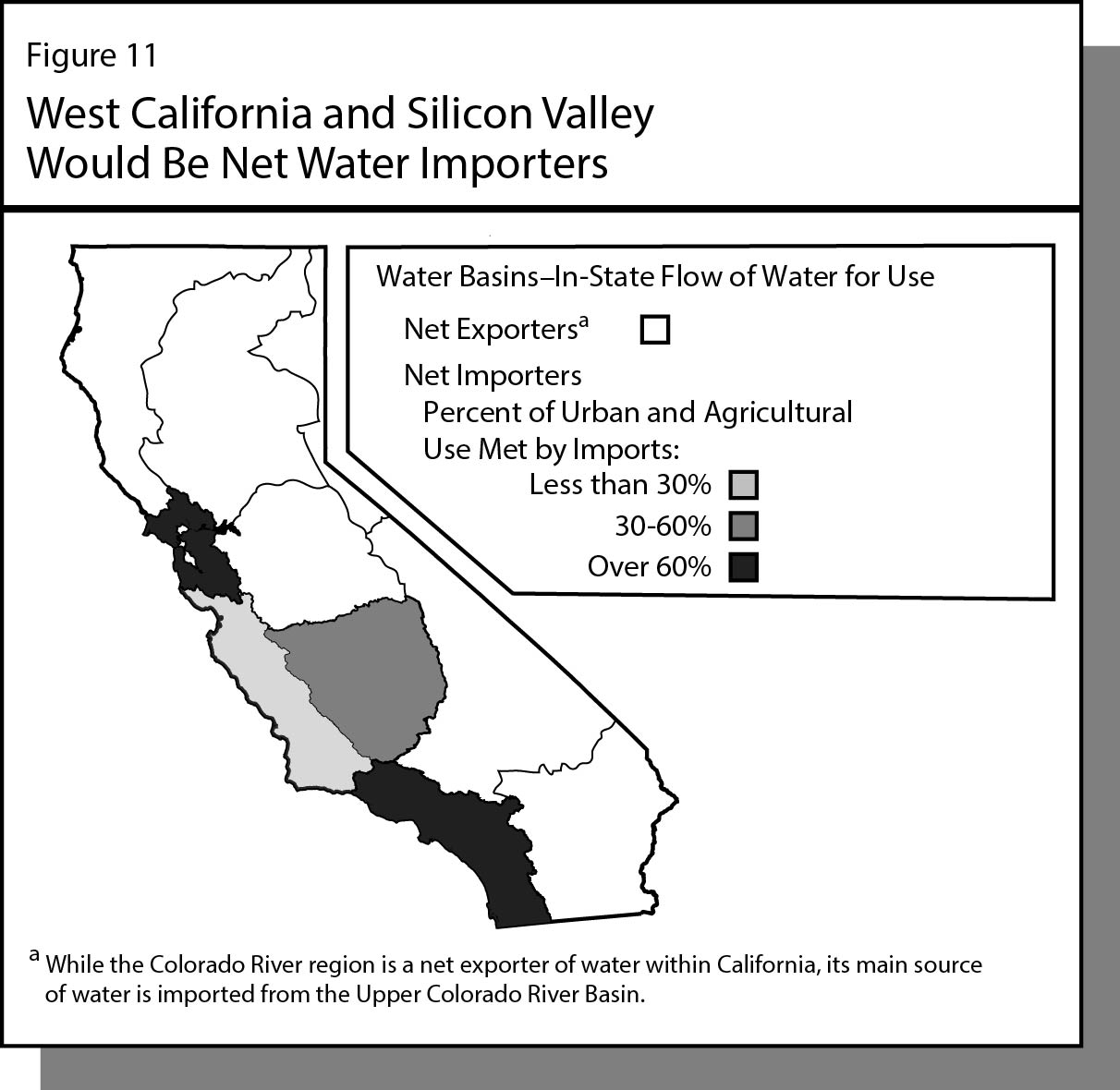

Silicon Valley and West California Are Net Importers of

Water. As shown in Figure 11 (see next page), four of the

state’s ten water basins depend significantly on water imported from

other regions of the state. These four basins, which are largely

urbanized and agricultural regions in central and coastal California,

account for a large portion of urban and agricultural water use

statewide. The state’s water basins in Figure 11 are marked by natural

boundaries, not the new state boundaries specified in this measure. In

general, however, the areas of Silicon Valley and West California

currently appear to be net importers of water from the other states

established by this measure. For example, the San Francisco Public

Utilities Commission (Silicon Valley) delivers water from the Hetch

Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park (Central California) to

2.5 million Bay Area customers. The Metropolitan Water District of

Southern California, which supplies water utilities in West California

and South California, derives its supplies from the northern part of

California via the SWP and from the Colorado River. (The Colorado River

borders only one of the proposed states: South California.)

At least three of the proposed states—Central California, North

California, and South California—contain parts of at least one water

basin that is currently a net importer and another basin that is a net

exporter. Jefferson—location of the largest artificial water reservoirs

in California—currently is a net exporter of water.

Decisions Concerning Water. The proposed

Board of Commissioners would have to consider how to divide California’s

water and related hydroelectric resources among the six proposed states.

In addition, Congress might have to consider water issues for the six

proposed new states—as well as other states bordering the Colorado

River—when considering the statehood proposal. Some issues likely would

have to be addressed in the courts. The development of multistate water

and power arrangements seems likely after California’s split into six

states. The details of these arrangements—their organization, their

funding, and the disposition of current water and power supplies—would

depend on decisions by all of these entities and the new states’

leaders.

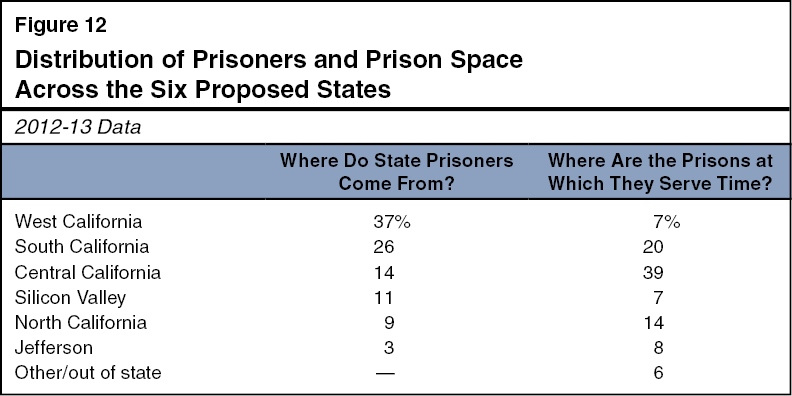

Issues Concerning Prisons

Distribution of Prison Beds Among the Six Proposed

States. Currently, certain higher-level felons—generally,

those with a current or prior conviction for a violent, serious, or sex

offense—are sentenced to one of 34 state prisons managed by the

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

Figure 12 (see next page) shows that about three of every four prisoners

in the CDCR system comes from West California, South California, and

Silicon Valley. These three areas combined, however, currently house

only a little more than one-third of the state’s prison inmates. By

contrast, only about one of every four prisoners comes from Central

California, North California, and Jefferson, while these three states

currently house over 60 percent of the state’s prison inmates. Prisons

in Central California alone house nearly 40 percent of CDCR inmates. The

Board of Commissioners would have to consider these issues when making

decisions about prison facilities near the time of statehood, and these

issues could affect decisions by the new states’ leaders over the long

term concerning prison operations, prison funding, and criminal justice

policies generally.

Other Issues

Outcomes Would Depend on Decisions Made by New States’

Leaders. For all of the issues described above, the

effects that California’s split would have on the new state and local

governmental entities would depend on decisions made by the Board of

Commissioners, the new states’ leaders, Congress, and, in some cases,

the courts. In addition to issues related to education, health and

social services, water, and prisons, the new states’ leaders would have

to make decisions concerning many other issues that could affect public

spending, such as:

- The new states’ tax structures, including whether to continue

the provisions of California’s Proposition 13 (1978).

- Laws and regulations concerning environmental quality and

economic development.

- How to finance transportation and other infrastructure and

whether to complete California’s planned high-speed rail system as a

multistate system.

- How to compensate public employees—including their health and

retirement benefits—and how to address unfunded liabilities of

California’s existing public employee retirement plans.

- Laws related to marriage and families.

- Various other policies related to criminal justice and public

safety, including ones concerning gun ownership and use.

Decisions Could Result in Demographic and Economic

Changes. The decisions made in all of the areas discussed

in this analysis could result in changes to the six states’ demographics

and economy, both initially and over time. For example, differing

policies could result in migration or different settlement patterns

initially. Over the longer term, the states’ economic development and

other policies could alter their respective economies. The exact nature

of these changes, both initially and over time, is unknown.

One-Time Costs to Transition From One State to Six New

States. The State of California and the six new state

governments, collectively, would have to pay various one-time costs in

the decade or so after approval of this measure. For example, the

measure requires funding the work of the Board of Commissioners, which

could total tens of millions of dollars per year in some of the years

soon after this measure’s passage. In addition, some of the new states

could choose to spend money on new buildings, such as new state

capitols, to house their new state governments in the early years after

congressional approval of their statehood. Depending on decisions made

during the transition period, some of these costs could perhaps be

offset by selling existing State of California buildings. These one-time

costs would be minor compared to the other long-term public spending

changes likely to result from the creation of the new states.

Summary of Fiscal Effects

This measure would have the following major fiscal effects:

- If the federal government approves the proposed creation of six

new states, all tax collections and spending by the existing State

of California would end, with its assets and liabilities divided

among the new states.

- Decisions by appointed commissioners and elected leaders would

determine how taxes, public spending, and other public policies

would change for the new states and their local governments.

Return to Initiatives

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page