The 2011–12 state spending plan includes total budget expenditures of $120.1 billion from the General Fund and special funds, as shown in Figure 1. This consists of $85.9 billion from the General Fund and $34.1 billion from special funds. While General Fund spending has dropped by around 6 percent from 2010–11, this has, in part been offset by increases in special fund spending as the state shifts some programs—from state to local responsibility under what has been called "realignment"—from General Fund support to special fund support. Federal funds spending continues to decline with the expiration of much of the funding made available through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Figure 2 summarizes the estimated General Fund condition for 2010–11 and 2011–12.

Figure 3 shows the solutions adopted to close the budget gap. The budget plan (including gubernatorial vetoes) includes the following actions (based upon our office's categorization):

Figure 2 displays the estimated revenue effects of the revenue–related budget solutions in the budget package. By far, the most significant solutions were those that scored additional baseline revenues—that is, additional revenues above what was assumed in January due to economic performance and not any increase in tax rates or tax bases. Over one–half of the additional revenues were assumed consistent with the administration's May Revision economic forecast, and the remainder was built into the budget package during the final days of legislative action on the budget plan in June 2011. The budget package also authorized $2.9 billion of additional loans and transfers to the General Fund from state special funds. This included a $320 million loan from the Disability Insurance Fund. Many, but not all, of these loans and transfers are reflected in the loans and transfers item of Figure 1.

The realignment plan included in the 2011–12 budget package is discussed in more detail in "Chapter 3." This section briefly discusses revenue actions in the budget that are related to the realignment plan.

Proposition 98 funding constitutes about 70 percent of total funding for K–12 education and the California Community Colleges (CCC). Proposition 98 funding also supports the state's subsidized preschool program and, historically, has supported certain child care programs. In this section, we review the changes in 2010–11 Proposition 98 spending and describe the major Proposition 98 components of the 2011–12 budget package. In the following three sections, we discuss in more detail the budgets for K–12 education, child care, and community colleges, respectively.

Figure 1 shows all the changes in the 2011–12 Proposition 98 minimum guarantee relative to the January current–law estimate. These changes are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 2 (see next page) shows funding levels for K–12 education, CCC, child care, and other Proposition 98–supported agencies (including the state special schools and juvenile justice). As the figure shows, total K–12 education funding remains relatively flat from 2010–11 to 2011–12. The share covered by local property taxes, however, is significantly higher (largely due to estimated redevelopment agency remittance payments) whereas the share covered by the General Fund is lower. Proposition 98 funding for community colleges is down $419 million year over year. Child care funding is removed from the Proposition 98 guarantee beginning in 2011–12. Although not evident from the figure (which shows only ongoing Proposition 98 funding), overall child care funding (including one–time funding) is reduced by roughly $400 million year over year.

As discussed earlier, the 2011–12 budget package includes various "trigger" reductions that would be implemented if estimates of state revenues as of December 2011 are more than $1 billion lower than budget assumptions, with additional reductions triggered if revenues fall more than $2 billion below budget assumptions.

The state currently faces a number of Proposition 98–related funding obligations associated with payment deferrals, K–12 revenue limits, mandates, the Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA), and the Emergency Repair Program (ERP).

Figure 3 shows K–12 per–pupil programmatic funding from 2007–08 through 2011–12. Per–pupil programmatic funding decreased by $117 from 2010–11 to 2011–12, reflecting a 1.5 percent year–over–year reduction. School districts will receive $522 less per pupil in 2011–12 than in 2007–08.

In addition to K–12 revenue limit deferrals, discussed earlier, and a major change in funding for certain student mental health services, discussed below, the budget package includes the following K–12 spending changes.

The budget package includes a notable shift of program and funding responsibility related in student mental health services.

The budget package also includes several budget provisions that affect school district financial management and administration.

Although former Stage 3 families maintained eligibility for services, uncertainty regarding the program's funding and status in the months following the veto resulted in decreased caseload numbers once program services resumed. (Some Stage 3 families re–enrolled in CalWORKs Stage 2 child care through the county–level Diversion program, resulting in a $27 million increase in 2010–11 Stage 2 costs compared to 2010–11 Budget Act assumptions.) As shown in Figure 4, budget estimates reflect diminished Stage 3 caseload levels continuing through 2011–12.

Figure 5

Major Child Care and Development Spending Changes

(In Millions)

|

Change

|

Amount

|

|

Reduce child care contracts by 11 percenta

|

–$177

|

|

Make technical and caseload adjustments

|

–122

|

|

Reduce maximum reimbursement rate for license–exempt providers from 80 percent to 60 percent of licensed rate

|

–68b

|

|

Lower maximum income eligibility from 75 percent to 70 percent of the state median income

|

–28

|

|

Reduce or eliminate quality improvement activities

|

–16

|

|

Eliminate $7.9 million for Centralized Eligibility Lists, redirect funds to child care program

|

—

|

|

Total

|

–$412

|

<

Higher Education

The enacted budget provides a total of $10.1 billion in General Fund support for higher education in 2011–12 (see Figure 6). This reflects a decrease of $1.4 billion, or 12 percent, from the 2010–11 amount. Thus, the 2011–12 budget more than eliminates the $911 million General Fund increase higher education received the previous year. As a result, higher education's share of state General Fund spending declines from 12.6 percent to 11.8 percent.

Figure 6

Higher Education Funding

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

Change From 2010–11

|

|

Change

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$2,911.6

|

$2,374.1

|

$537.6

|

–18%

|

|

California State University

|

2,607.7

|

2,141.3

|

466.4

|

–18

|

|

California Community College

|

3,913.5

|

3,477.3

|

436.2

|

–11

|

|

Hastings University

|

8.4

|

6.9

|

1.4

|

–17

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

1,257.3

|

1,402.9

|

145.6

|

12

|

|

California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

1.9

|

—

|

1.9

|

–100

|

|

General obligation bond debt service

|

809.9

|

743.2

|

66.8

|

–8

|

|

Lease–revenue bond debt servicea

|

(265.8)

|

(267.7)

|

(1.9)

|

(1)

|

|

Totals

|

$11,510.3

|

$10,145.6

|

$1,364.7

|

–12%

|

Tuition Partly Backfills Cuts. All three public higher education segments will receive additional tuition and fee revenue as a result of approved increases. After diverting a portion of this new revenue to institutional financial aid programs, the segments will receive from these increases about $675 million, which effectively backfills an equal amount of their General Fund reductions. As explained below, this continues a recent trend whereby students pay an increasing share of the cost of their education.

When all core sources of revenue (including General Fund, local property taxes, federal stimulus funds, and net fees/tuition) are considered, higher education's programmatic support is now about 7 percent lower than it was in 2010–11 (see Figure 7). Compared to 2007–08—generally considered to be the last "normal" funding year before the current recession necessitated spending reductions—higher education's programmatic support has declined about 2 percent.

Figure 7

Higher Education Programmatic Supporta

Selected Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

Change From 2010–11

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$4,399.7

|

$4,326.4

|

$4,067.0

|

$4,841.9

|

$4,313.6

|

–$528.22

|

–11%

|

|

California State University

|

3,945.0

|

4,018.4

|

3,599.0

|

4,015.1

|

3,587.8

|

–427.30

|

–11

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

6,702.9

|

6,796.0

|

6,442.6

|

6,595.4

|

6,228.6

|

–366.80

|

–6

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

32.3

|

36.8

|

39.1

|

42.7

|

42.4

|

–0.30

|

–1

|

|

California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

2.1

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

1.9

|

—

|

–1.85

|

—

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

866.7

|

912.3

|

1,075.5

|

1,357.5

|

1,465.1

|

107.63

|

8

|

|

Totals

|

|

$16,091.9

|

|

$16,854.4

|

|

|

–7%

|

UC and CSU

Overall Funding. As shown in Figure 6, the 2011–12 budget provides $2.4 billion in General Fund support to the University of California (UC), and $2.1 billion to the California State University (CSU). For both university systems, these amounts reflect net reductions of 18 percent. Specifically, each segment received a General Fund reduction of $650 million, a General Fund augmentation of $106 million to replace one–time federal stimulus funds in the 2010–11 budget, and a variety of other technical adjustments. Approved tuition increases (net of amounts set aside for student financial aid) will backfill about $266 million and $300 million, respectively, of UC and CSU's General Fund reductions. As a result, the decline in total programmatic funding for each system is about 11 percent.

Potential for Further General Fund Reductions. The UC and CSU budgets each reflect a $500 million reduction originally proposed in the Governor's January budget, as well as an additional $150 million reduction included in the final budget agreement. As described in "Chapter 1", the enacted budget makes provision for an additional $100 million General Fund reduction to each university system in the event that anticipated state revenues are not realized. If the Director of Finance determines that revenues are projected to fall more than $1 billion short, the Director must reduce UC and CSU's General Fund appropriations by up to $100 million each.

Enrollment Targets. The 2011–12 budget sets state–supported enrollment targets of 209,977 full–time equivalent (FTE) students at UC and 331,716 FTE students at CSU. The target for UC is the same as the 2010–11 target, while the CSU target is about 8,000 FTE students lower than in 2010–11. The CSU's enrollment fell short of its target in 2010–11, and a provision in that year's budget caused $75 million in General Fund support associated with that enrollment shortfall to be reverted from CSU's budget. In a departure from past practice, the 2011–12 budget provides for no reversion of funding if either university system falls short of its enrollment target.

Student Tuition. Both UC and CSU have approved the following tuition increases for the 2011–12 academic year:

- The UC Regents initially adopted an 8 percent increase at their November 2010 meeting. In July 2011, following adoption of the 2011–12 Budget Act, they approved an additional 9.6 percent increase. Together, those actions bring 2011–12 mandatory systemwide charges to $12,192—an overall increase of 18.3 percent. Including mandatory campus fees, undergraduate students will pay an average of about $13,218 at UC campuses.

- The CSU Trustees initially adopted a 10 percent tuition increase for 2011–12 in November 2010, and approved an additional 12 percent increase in July, for an overall increase of 23.2 percent. Mandatory systemwide charges for CSU undergraduates will be $5,472, with campus fees (some of which may increase) adding another $1,000 on average.

The 2011–12 tuition increases are expected to generate about $415 million at UC and $450 million at CSU in additional revenues. Both segments plan to increase financial aid expenditures by about one–third of this amount. In addition, Cal Grant recipients will receive larger grants to cover the tuition increases.

Other Provisions. The budget includes several new requirements for the universities. One provision requires UC to allocate $3 million of its General Fund appropriation for scheduled salary increases for its service employees. Other provisions provide guidance as to how the universities allocate their budget reductions, prohibiting disproportionate cuts in academic preparation and outreach programs at both segments, and in certain math, science, and nursing education programs at UC. The Budget Act makes explicit a longstanding prohibition on the use of General Fund appropriations to support auxiliary enterprises or intercollegiate athletic programs at UC. Trailer bill language strengthens requirements for CSU's annual systemwide audit and removes a requirement for individual campus audits.

Capital Outlay. The budget includes appropriations for six UC projects—$45.3 million in lease–revenue bond funding for two new projects, and $9.3 million in general obligation bond funding for the equipment phase of four projects. It also includes appropriations for seven CSU projects—$201 million in lease–revenue bond funding for five new projects, and $2.8 million in general obligation bond funding for the equipment phase of two projects.

California Community Colleges

Like K–12 education, community colleges' local property tax revenue and most of their General Fund support is included within Proposition 98's funding formulas. Figure 2 (in the "Proposition 98" section of this chapter) shows that the 2011–12 budget package provides the CCC system with $5.4 billion in Proposition 98 funding, which is 11.1 percent of total state Proposition 98 spending. This reflects a reduction of $419 million (7 percent) from the revised 2010–11 spending level.

Budget Defers More Funding to Later Years. As noted earlier in the "Proposition 98" section, the 2011–12 budget defers an additional $129 million to 2012–13, thereby creating a total ongoing deferral of $961 million. This represents about 17 percent of Proposition 98 funding for CCC.

Base Apportionment Cuts Coupled With Workload–Reduction Provision. The budget includes a $400 million base reduction in Proposition 98 General Fund support for CCC apportionments (general–purpose monies), offset by an increase of $110 million in fee revenue. The budget includes a provision that permits community colleges to reduce the number of students they serve in 2011–12 in proportion to the net reduction in base apportionment funding ($290 million). The provision expresses the Legislature's intent that any resulting workload reductions be limited as much as possible to "courses and programs outside of those needed by students to achieve their basic skills, workforce training, or transfer goals."

Higher Student Fees to Mitigate Budget Cuts. The budget package increases enrollment fees from $26 per unit to $36 per unit beginning in the fall 2011 term. The budget assumes that these higher fees will generate $110 million in additional revenue for CCC, thereby mitigating the impact of reduced Proposition 98 General Fund support for apportionments.

Categorical–Program Flexibility Extended. As discussed in our 2009–10 California Spending Plan (page 34), the 2009–10 budget created a "flex item" so that, between 2009–10 and 2012–13, community colleges could transfer funds from about a dozen categorical programs to any other categorical spending purpose. The 2011–12 budget package extends this flexibility until the end of 2014–15.

Mandates. The budget provides $9.5 million in Proposition 98 monies for CCC mandates, and suspends 7 of CCC's 21 mandates. Two of these seven mandates were added in the 2011–12 budget (Student Records and Sexual Assault Response Procedures).

Trigger Cuts. As noted in the "Proposition 98" section, if projected 2011–12 state revenues fall short by at least $1 billion, CCC's apportionment funding would be reduced by an additional $30 million. In addition, enrollment fees would be increased from $36 per unit to $46 per unit beginning in January 2012, which would likely generate enough revenues to backfill the $30 million cut. If projected 2011–12 state revenues fall short by more than $2 billion, CCC apportionments would be further reduced by $72 million.

Capital Outlay. The 2011–12 budget package appropriates $48.6 million in general obligation bond funding for three continuing projects (at City College of San Francisco, College of the Canyons, and Orange Coast College).

California Postsecondary Education Commission (CPEC)

The Governor's May Revision proposed to reduce CPEC's General Fund support roughly by half, and eliminate the commission as of January 1, 2012. Most of CPEC's functions would disappear, with the exception of a federal teacher grant program that would be transferred from CPEC to CDE. The Legislature rejected the Governor's proposal, and restored full funding for CPEC. The Legislature also adopted supplemental report language directing LAO to recommend structures and duties for a statewide higher education coordinating body. The report is to be submitted to the Legislature by January 1, 2012.

The Governor vetoed all funding for CPEC, and in his veto message requested that the three segments and other higher education stakeholders explore alternatives for coordinating higher education.

California Student Aid Commission (CSAC)

The budget provides $1.5 billion for CSAC, including $1.4 billion in General Fund support, $62.3 million in one–time funds from the Student Loan Operating Fund (SLOF), and $15 million in federal funds for Cal Grants and other financial aid programs. This reflects an increase of about $145 million from the 2010–11 level, primarily to offset tuition increases at UC and CSU. However, given that UC and CSU raised tuition further after passage of the budget act, actual Cal Grant costs are likely to be at least $100 million higher than the amount appropriated for this purpose.

The budget act and related legislation make two significant changes to the operation of Cal Grants programs:

- Tighter Eligibility Criteria for Renewals. Previously, Cal Grant recipients only had to meet certain eligibility criteria when they first applied for a Cal Grant (and not when they renewed the grant in subsequent years). Changes enacted with the budget package now require Cal Grant recipients applying for renewals to meet several of those requirements. For example, a renewal applicant's family income and assets must fall below specified levels (see Figure 8). Applying these requirements to renewals will disqualify an estimated 12,920 recipients who would otherwise be eligible for awards, reducing Cal Grant expenditures by about $100 million. To mitigate the impact on students, CSAC will use the higher of the limits in place at the time of a student's initial award and those in place at the time of renewal.

- New Restrictions on Student Loan Default Rates. A second change enacted by the budget package removes some higher education institutions from eligibility to participate in Cal Grant programs. Specifically, institutions may not participate if a high proportion of their former students default on federal student loans. For 2011–12, the threshold is set at 24.6 percent of an institution's students defaulting within three years of loan repayment, as defined and calculated by the federal government. For subsequent years, the ceiling is 30 percent. These ceilings apply only to institutions with 40 percent or more of undergraduates borrowing federal student loans. For 2011–12, about 76 institutions are affected, and most of these are career and technical colleges. There is a limited exception for continuing students at institutions that become ineligible. These students may qualify for renewal awards reduced by 20 percent.

Figure 8

2011–12 California Grant Program Income and Asset Ceilings for Dependent Students

|

Family Size

|

Cal Grant A and C

|

Cal Grant B

|

|

Income Ceilings

|

|

|

|

Six or more

|

$90,300

|

$49,600

|

|

Five

|

83,800

|

46,000

|

|

Four

|

78,100

|

41,100

|

|

Three

|

71,900

|

36,900

|

|

Two

|

70,200

|

32,800

|

|

Asset Ceiling

|

|

|

|

All family sizes

|

60,500

|

60,500

|

Federal Loan Program. In November 2010, the U.S. Department of Education transferred federal student loans guaranteed by CSAC (and serviced by its auxiliary, EdFund) to Education Credit Management Corporation (ECMC), ending California's role in administering federally guaranteed loans. As part of the transition, ECMC has entered into a two–year agreement to provide CSAC with technical and operational support previously offered by EdFund. In addition to providing some services, ECMC has also agreed to continue sharing proceeds from SLOF to offset Cal Grant costs. The Governor's budget assumed a $30 million General Fund offset from this source, and subsequent actions by the ECMC Board raised the available amount to $62.25 million. The SLOF contributions are expected to continue beyond the two–year service agreement, with available amounts to be determined annually by the ECMC Board.

Realignment

As part of the 2011–12 budget package, the Legislature made a number of changes to realign certain state program responsibilities and revenues to local governments (primarily counties). Figure 3 in "Chapter 1" identifies the budget–related bills including those related to the realignment package. In total, the realignment plan provides $6.3 billion in 2011–12 to local governments to fund various criminal justice, mental health, and social service programs. The plan adopted by the Legislature is largely similar to the one proposed by the Governor, as modified in the May Revision, with respect to the programs realigned and the amount of revenue provided to local governments. However, the adopted realignment package differs in two important respects from the administration's proposal. First, the Legislature's plan relies on a shift of existing state and local tax revenues rather than the extension of expiring tax rates as proposed by the Governor. Second, the adopted budget legislation does not include the Governor's proposal for a constitutional amendment to, among other things, make the funding allocations to local governments permanent and protect the state from potential mandate claims. We discuss the details of the adopted realignment package in more detail below.

Architecture of 2011 Realignment

2011–12 Expenditures

The realignment package includes $6.3 billion in 2011–12 for court security, corrections and public safety, mental health services, substance abuse treatment, child welfare programs, adult protective services, and CalWORKs. Figure 9 displays the amounts dedicated to each of the realigned programs in 2011–12.

Figure 9

Expenditures for 2011 Realignment

(In Millions)

|

Adult offenders and parolees

|

$1,587

|

|

Local public safety grant programs

|

490

|

|

Court security

|

496

|

|

Existing juvenile justice realignment

|

97

|

|

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment

|

579

|

|

Mental health managed care

|

184

|

|

Drug and alcohol programs—substance abuse treatment

|

184

|

|

Foster care and child welfare services

|

1,567

|

|

Adult protective services

|

55

|

|

CalWORKs/mental health transfer

|

1,084

|

|

CalWORKs

|

(1,066)

|

|

Mental health

|

(18)

|

|

Total

|

$6,322

|

Shift of Existing State and Local Revenues

Unlike the Governor's realignment proposal, the realignment package adopted by the Legislature does not extend the sales and vehicle license fee (VLF) tax rate increases that expired at the end of 2010–11. Instead, the budget reallocates $5.6 billion of state sales tax and state and local VLF revenues for purposes of realignment in 2011–12. Specifically, the Legislature approved the diversion of 1.0625 cents of the state's sales and use tax rate to counties. This is projected to generate $5.1 billion in 2011–12, growing to $6.4 billion in 2014–15 (see Figure 10,). In addition, the realignment plan redirects an estimated $453 million from the base 0.65 percent VLF rate for local law enforcement grant programs. Under prior law, these VLF revenues were allocated to the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) ($300 million) for administrative purposes and to cities and Orange County ($153 million) for general purposes. The budget increases the motor vehicle registration fee by $12 per automobile to offset the lost revenue to DMV. The budget also shifts $763 million on a one–time basis in 2011–12 from the Mental Health Services Fund (established with voter approval of Proposition 63 in November 2004) for support of the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) and Mental Health Managed Care programs.

Figure 10

Revenues for Realignment

(In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

$5,106

|

$5,571

|

$6,015

|

$6,388

|

|

Vehicle license fee

|

453

|

453

|

453

|

453

|

|

Proposition 63

|

763

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$6,322

|

$6,025

|

$6,468

|

$6,841

|

Realignment Account Structure

The revenues provided for realignment are deposited into a new fund, the Local Revenue Fund 2011. The budget package creates 8 separate accounts and 12 subaccounts within this fund to pay for the realigned programs. One of the accounts, the Mental Health Account, is somewhat different than the other accounts because its funds support the CalWORKs program and interact with accounts created in 1991 under the state–local realignment plan adopted at that time. Another account created in the Local Revenue Fund 2011 is the Reserve Account, where revenues in excess of the amount projected for each account are deposited. The budget legislation requires revenue deposited into the Reserve Account to be used to reimburse counties for programs paid from the Foster Care, Drug Medi–Cal, and Adoption Assistance Program Subaccounts. In addition, for 2011–12, the budget assumes that about $1.2 billion of the funds deposited into the Local Revenue Fund 2011 will be used to reimburse the state for costs associated with incarcerating and supervising inmates and parolees who were convicted prior to the implementation of realignment.

The budget legislation establishes various formulas to determine how much revenue is deposited into each account and subaccount. Several of these accounts and subaccounts have annual caps on how much funding each can receive. The budget package limits the use of funds deposited into each account and subaccount to the specific programmatic purpose of the account or subaccount. The budget does not contain any provisions allowing cities or counties flexibility to shift funds among these programs. The budget legislation also contains some formulas and general direction to determine how the funding would be allocated among counties. The budget legislation does not specify program allocations among the various accounts and subaccounts, or among counties, for 2012–13 and beyond (except for the CalWORKs/mental health transfer which appears to be ongoing). Despite uncertainty surrounding these ongoing allocations, the revenues being deposited into the Local Revenue Fund 2011 for purposes of realignment are expected to be ongoing.

Legislative Intent for Future Actions. The budget package also includes legislative intent language that (1) new allocation formulas be developed for 2012–13 and subsequent fiscal years, and (2) sufficient protections be in place to provide ongoing funding and mandate protection for the state and local governments.

Most of State Fiscal Benefit From Proposition 98 Savings

The budget assumes that, by depositing the sales tax revenue into a special fund for use by local governments for realignment, these funds are not available for the Legislature to spend for education purposes and thus are not counted as state revenue for purposes of calculating the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee. As discussed more fully in our education section of this report, this action reduced the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee by $2.1 billion. The exclusion of these revenues, however, is contingent upon the approval of a ballot measure providing additional funding for K–12 school districts and community colleges. If no ballot measure is adopted satisfying these requirements, the funds would not be excluded from the guarantee moving forward and the state would need to repay K–14 education for the loss of $2.1 billion for the 2011–12 year.

In addition to the Proposition 98 savings, the realignment plan achieves state General Fund savings in two other ways. First, using VLF revenue to fund local law enforcement grant programs reduces the state's costs for these programs by $453 million. Second, the budget assumes about $86 million in savings to the state associated with corrections realignment. Offsetting these savings, however, is $34 million provided in the budget to support local government hiring, training, and other transition costs associated with implementing the corrections realignment in 2011–12.

Description of Realignment Changes

We describe each of the major programs included in the realignment package below.

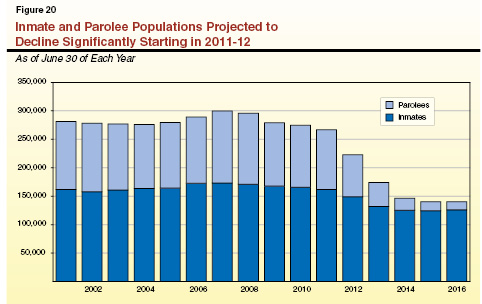

Adult Offenders and Parolees

As part of the 2011–12 budget package, the Legislature shifted the responsibility for certain lower–level offenders, parole violators, and parolees from the state to the counties on a prospective basis effective October 1, 2011. Under the realignment plan, the shifted offenders who previously would have been sentenced to state prison will now serve their sentence in a county jail and/or under local community supervision. In addition, certain offenders released from prison will now be supervised in the community by county agencies (such as county probation) instead of by state parole agents. When locally supervised offenders violate the terms and conditions of their supervision, the courts, rather than the Board of Parole Hearings, will preside over revocation hearings to determine if they should be revoked to county jail. According to the administration, the above changes are projected to reduce the state inmate population by about 14,000 inmates in 2011–12 and nearly 40,000 inmates (roughly one–fourth of the total inmate population) upon full implementation in 2014–15. The state parolee population is projected to decline by about 25,000 parolees in 2011–12 and by 77,000 parolees (roughly three–fourths of the total parole population) in 2014–15. The budget assumes that the reduction in the inmate and parolee populations will result in state savings of about $453 million in 2011–12, growing to $1.5 billion upon full implementation.

The realignment plan assumes a total of $1.6 billion from the Local Revenue Fund 2011 to support the realignment of adult offenders and parolees in 2011. Of this total, $354 million will be transferred to the newly established Local Community Corrections Account to support the local incarceration and supervision of the realigned offenders. In addition, the plan estimates that about $13 million will be transferred into the District Attorney and Public Defender Account to support the involvement of district attorneys and public defenders in parole revocation proceedings. The funds in these two accounts will be distributed in 2011–12 to counties based on a formula that takes into account various factors, such as the proportion of the state prison population that is from a particular county. The realignment plan also assumes that the Local Revenue Fund 2011 will reimburse the state about $1.2 billion for costs that the state incurs in 2011–12 for lower–level offenders in state prison who were sentenced prior to October 1, 2011 (when the realignment is implemented).

Local Public Safety Grant Programs

Under the realignment plan, funding for various local public safety grant programs (such as the Citizens' Option for Public Safety Program, juvenile justice grant programs, and booking fees) will be shifted directly to local governments for the same purposes as specified in existing statutes.

Under the plan, a total of about $490 million will be transferred to the newly established Local Law Enforcement Services Account—an estimated $453 million from the redirection of existing VLF revenue and $37 million from the Local Revenue Fund 2011—to support the realigned public safety grant programs. For 2011–12, the funds in this account will be allocated to local governments by the State Controller's Office generally based on the level of funding received for each grant program in recent years. The realignment plan requires that, if there are insufficient revenues to fully fund this account, the Director of Finance shall allocate the funds necessary from the Local Revenue Fund 2011 to provide the full allocation.

Court Security

Current law generally requires trial courts to contract with their local sheriff's offices for court security. Under the realignment plan, the sheriffs would continue to be responsible for providing court security. However, funding to pay for the security will now be provided directly to the sheriffs rather than being appropriated in the annual state budget to the trial courts. Existing statutes related to court security (such as the requirement that each trial court negotiate a memorandum of understanding with the sheriff specifying the level of security to be provided) are unchanged.

The realignment plan estimates that $496 million from the Local Revenue Fund 2011 will be transferred to the newly established Trial Court Security Account for allocation to county sheriffs for the provision of court security. Under the terms of the realignment legislation, the Department of Finance (DOF) will determine how much money is allocated to each county sheriff for these purposes in 2011–12. According to DOF, the allocation of funds in 2011–12 will generally be determined based on the amount of state funding a given sheriff's office received in 2010–11 for court security.

Existing Juvenile Justice Realignment

Under recent statutory changes, only certain juvenile offenders who are violent, serious, or sex offenders may be committed to youth correctional facilities operated by the state. Counties are responsible for the housing and supervision of all other juvenile offenders, as well as for the community supervision of all offenders upon their release from state youth correctional facilities, including some who previously were state responsibility. Counties receive state funding from two grants to support these responsibilities—the Youthful Offender Block Grant Program and the Juvenile Reentry Grant. Under the realignment plan, funding for these grants will be shifted directly to counties for the same purposes as specified in existing statutes.

The realignment plan estimates that $97 million from the Local Revenue Fund 2011 will be transferred to the Juvenile Justice Account in support of the above grants—$93.4 million for the Youthful Offender Block Grant Program and $3.7 million for the Juvenile Reentry Grant. The allocation of these grants among the 58 counties is unchanged in 2011–12.

Mental Health Managed Care (MHMC)

County Mental Health Plans administer MHMC and are responsible for ensuring that Medi–Cal beneficiaries receive specialty mental health services. Under a federal waiver, specialty mental health services are "carved out" of the Medi–Cal program administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), which provides physical health care. County mental health plans generally have responsibility for authorization and payment of Medi–Cal covered psychiatric inpatient hospital services and outpatient specialty mental health services. In November 2004, the state's voters approved Proposition 63, an initiative that allocated additional state revenues generated through a surcharge on income taxpayers earning more than $1 million annually for various specified community mental health programs.

Under realignment, in 2011–12 about $184 million of Proposition 63 (Mental Health Services Act) funds will be redirected and used in lieu of General Fund on a one–time basis to support MHMC. Proposition 63 revenues are not deposited into the Local Revenue Fund 2011. Although the final budget package did not specify ongoing realignment allocations, the administration's plan was for realignment revenues to substitute for the Proposition 63 funds on an ongoing basis beginning in 2012–13.

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment

The EPSDT is a federally mandated program that requires the state to provide Medi–Cal beneficiaries under age 21 with any physical and mental health services that are deemed medically necessary to correct or ameliorate a defect, physical or mental illness, including services not otherwise included in the state's Medicaid plan. Periodic health screening, vision, dental, and hearing services are provided under EPSDT. So are some mental health services, including crisis intervention and medication monitoring. County mental health plans generally have responsibility for authorization and payment of mental health services provided through EPSDT.

Under realignment, in 2011–12, about $580 million of Proposition 63 funds will be redirected and used in lieu of General Fund on a one–time basis to support EPSDT. Proposition 63 funds are not deposited into the Local Revenue Fund 2011. Although the final budget package did not specify ongoing realignment allocations, the administration's plan was for realignment revenues to substitute for the Proposition 63 funds on an ongoing basis beginning in 2012–13.

Drug and Alcohol Programs—Substance Abuse Treatment

The budget plan realigns several substance abuse treatment programs that were previously funded through the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP). While DADP in the past provided funding and state oversight of these programs, the provision of services has long been administered primarily at the county level. The major substance abuse treatment programs that have been realigned are:

- Regular and Perinatal Drug Medi–Cal. The Drug Medi–Cal program provides drug and alcohol–related treatment services to Medi–Cal beneficiaries. These include outpatient drug free services, narcotic replacement therapy, day care rehabilitative services, and residential services for pregnant and parenting women.

- Regular and Perinatal Non Drug Medi–Cal. The Non Drug Medi–Cal program provides treatment services generally to individuals who do not qualify for Medi–Cal. This includes the Women and Children's Residential Treatment Services Program.

- Drug Courts. Drug courts link supervision and treatment of drug users with ongoing judicial monitoring and oversight.

The budget plan realigns a total of about $184 million of DADP programs (Regular and Perinatal Drug Medi–Cal, $131 million; Regular and Perinatal Non Drug–Medi–Cal, $26 million; and Drug Courts, $27 million) to the counties. Under the realignment plan, funding for these programs are deposited into three separate subaccounts within the newly created Health and Human Services Account of the Local Revenue Fund 2011. Under realignment, some programs would be supported with a combination of realignment funds and federal matching funds, while other programs would be supported mainly by realignment funds.

Foster Care and Child Welfare Services (CWS)

California's child welfare system was created to prevent, identify, and respond to allegations of child abuse and neglect. Under prior law, the state and counties shared the nonfederal costs of the child welfare system. Pursuant to the realignment legislation of 2011, counties will now bear 100 percent of the costs for nearly the entire child welfare system, including CWS, Foster Care, Adoptions, Adoptions Assistance, and Child Abuse Prevention. (The state will continue to oversee the CWS Case Management System, social worker training, state–tribal agreements, and some adoptions services.) The realignment legislation does not change the major programmatic functions of the child welfare system. Counties, which were already responsible for ensuring the safety of children within their communities, will continue to make the decision of whether or not to remove a child from a home due to allegations of abuse or neglect. Meanwhile, the state will continue to oversee the child welfare system.

The budget legislation creates five child welfare system program subaccounts within the Health and Human Services Account of the Local Revenue Fund 2011. Under this arrangement, total funding for the child welfare system is estimated to be about $1.6 billion in 2011–12. The allocations for each subaccount are designed to be equal to what the programs would have received in General Fund support absent realignment. Funding in the CWS subaccount will be distributed among counties based on the 2010–11 allocation structure. Funding in the other subaccounts will be distributed to counties based on an allocation provided by DOF.

Adult Protective Services (APS)

County APS agencies investigate reports of abuse and neglect of elders and dependent adults who live in private settings. Upon investigating these reports, APS social workers may arrange for services such as counseling, money management, or out–of–home placement for the abused or neglected adult. Although there is no federal requirement to operate an APS program, state law currently requires that APS be available in all 58 counties.

The 2011–12 realignment legislation establishes the APS Subaccount within the Health and Human Services Account for the support of the APS program. The APS Subaccount will be allocated 3 percent of the funds available in the Health and Human Services Account, which is estimated to be $55 million in 2011–12. The funds from the APS Subaccount will be allocated to the local APS programs, to the extent possible, in the same way they were in 2010–11.

CalWORKs/Mental Health Transfer

The CalWORKs program provides cash grants and welfare–to–work services (such as child care, training, or job readiness) to families whose incomes are insufficient to meet their basic needs. The program is administered by the counties, but the state and federal governments provide the vast majority of funding. Although each county must provide grants and services consistent with state law, counties have significant control over how services are provided and when to sanction clients for noncompliance. With respect to funding, counties have a fixed maintenance–of–effort level for administration and welfare–to–work services, and a 2.5 percent share of grant costs. The 2011 realignment legislation provides counties with revenue from the Local Revenue Fund 2011 for mental health programs, which then frees up existing county mental health funding to pay for a higher share of CalWORKs grant costs. This process is described in more detail below.

In 1991, the Legislature adopted realignment legislation that, among other changes, established several local funding streams for various mental health and other programs. This included creation of a mental health subaccount and a social services subaccount. The 1991 social services subaccount is available to fund several programs including CalWORKs. The 2011 realignment legislation provides $1,084 million in funding for a new Mental Health Account in the Local Revenue Fund 2011. From this account, the 2011 legislation allocates to each county new mental health funding equal to what it would have received in its mental health subaccount under the 1991 realignment formula. Because the new funding is now available to pay mental health obligations, the 2011 legislation shifts the preexisting 1991 mental health funding to the social services subaccount with no detrimental effect on support for county mental health programs. The 2011 realignment legislation also increases each county's individual share of CalWORKs grant costs so that it exactly equals the amount of its new mental health realignment funds. Essentially, the additional mental health funding for 2011 pays for an increased county share of CalWORKs grants. On average this new county share for CalWORKs grants will be about 34 percent, but the exact amount will vary by county and be directly tied to what the county would have received under the 1991 formula for distribution of funding for mental health services. The amounts provided to counties will be recalculated each year to equal whatever they would otherwise have been under the 1991 formula.

Health

The 2011–12 spending plan provides $19.7 billion from the General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $2.2 billion, or 12.5 percent, compared to the revised prior–year spending level, as shown in Figure 11. The net increase largely reflects the following: (1) increases in caseload and utilization of services, (2) the expiration of federal economic stimulus funds used to temporarily offset state General Fund costs, (3) the adoption of significant health program reductions and cost–containment measures, and (4) shifts in the funding sources used to support various health programs. The major program–specific changes and cost–containment measures are summarized in Figure 12 (see next page) and discussed in more detail below.

Figure 11

Major Health Programs and Departments—Spending Trend

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

|

|

|

Change2010–11 to 2011–12

|

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Medi–Cal—Local Assistance

|

$10,136

|

$12,437

|

$14,701

|

$2,264

|

18.2%

|

|

Department of Developmental Services

|

2,419

|

2,451

|

2,622

|

171

|

7.0

|

|

Department of Mental Health

|

1,711

|

1,852

|

1,314a

|

–538

|

–29.0

|

|

Healthy Families Program—Local Assistance

|

217

|

126

|

286

|

160

|

127.0

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

184

|

186

|

226

|

40

|

21.5

|

|

Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs

|

189

|

189

|

222

|

33

|

17.5

|

|

Other Department of Health Care Services programs

|

106

|

32

|

96

|

64

|

200.0

|

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority

|

8

|

8

|

7

|

–1

|

–12.5

|

|

All other health programs (including state support)

|

212

|

221

|

219

|

–2

|

–0.9

|

|

Totals

|

$15,182

|

$17,502

|

$19,693

|

$2,191

|

12.5%

|

|

Costs paid from temporary federal funds

|

$3,995

|

$3,777

|

$31

|

|

|

|

Estimated realignment savingsb

|

—

|

—

|

–$184

|

|

|

Expiration of Enhanced Federal Funding. The ARRA, the 2009 federal economic stimulus law, and subsequent federal legislation extended fiscal relief to the states. California benefited from an enhanced federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP), which is the federal share of Medicaid costs, from October 2008 through June 2011. Normally the state pays 50 percent of costs for most Medi–Cal services and the federal government pays the balance. The ARRA temporarily increased the federal matching share to 61.59 percent. Subsequent federal legislation extended the enhanced FMAP for an additional six months, but reduced the level of federal funding available during this phase–out period in comparison to ARRA. The budget adjusts for the loss of about $3.8 billion in federal funding due to the expiration of the enhanced FMAP that the state received in 2010–11, thereby increasing state General Fund costs in the budget year. While the expiration of enhanced federal funding mainly affects General Fund expenditure levels for Medi–Cal benefits provided by DHCS, it also affects components of the Medi–Cal Program administered by other state departments that administer health programs.

Federal Waiver Helps State Achieve Savings. The budget assumes $400 million in General Fund savings related to Medi–Cal's 1115 demonstration waiver renewal. Under the waiver, the state may claim up to $400 million in federal funds to offset costs in designated state health programs that are generally supported only with state funds. The waiver savings are reflected in the budget as follows: (1) $219 million in Medi–Cal local assistance, (2) $74 million in AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) savings, and (3) $106 million in savings for DHCS Family Health Programs.

Administration States Intent to Eliminate Departments. As part of its 2011–12 budget proposal, the administration stated its intent to eventually eliminate the Department of Mental Health (DMH) and DADP. Responsibility for the programs administered by DMH and DADP would be transferred to other departments, agencies, and government entities. The administration indicates that as part of its 2012–13 budget proposal, it will submit a detailed plan to eliminate these two departments.

Department of Health Care Services (Medi–Cal)

The spending plan provides $14.7 billion from the General Fund for Medi–Cal local assistance expenditures administered by DHCS. This is an increase of almost $2.3 billion, or 18 percent, in General Fund support for Medi–Cal local assistance compared to the revised prior–year spending level. In addition to growth in caseload and utilization, several major factors contributed to this net increase:

- Expiration of FMAP. General Fund support was needed to offset the loss of $3.2 billion due to the expiration of the enhanced FMAP.

- Acceleration of Provider Payments. The administration took advantage of the enhanced FMAP before it expired by making payments to Medi–Cal providers and some managed care plans earlier than previously scheduled to achieve General Fund savings of $144 million. The accelerated payments resulted in a prior year cost of $691 million and reduced costs of $835 million in 2011–12.

- Hospital Quality Assurance Fee. The revised prior–year spending level reflected an estimated $770 million in hospital fee revenue from the imposition of a quality insurance fee used to offset General Fund costs. As we discuss below, pending legislation would again impose a quality assurance fee on hospitals that could generate an estimated $320 million in General Fund relief in 2011–12.

- Other Changes. The spending plan includes program reductions, fund shifts, and cost–containment measures that reduce program costs as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12

Major Changes—State Health Programs2011–12 General Fund Effect

(In Millions)

|

Program

|

Amount

|

|

Medi–Cal—Department of Health Care Services

|

|

|

Impose provider payment reduction of up to 10 percent

|

–$623

|

|

Impose mandatory copayments on Medi–Cal beneficiaries

|

–511

|

|

Implement unallocated reduction

|

–345

|

|

Eliminate Adult Day Health Care (ADHC) benefit

|

–170

|

|

Provide funds to transition ADHC beneficiaries to other services

|

85

|

|

Adopt fund shifts and one–time funding sources

|

–128

|

|

Collect additional drug rebates

|

–64

|

|

Impose "soft cap" on physician and clinic visits

|

–41

|

|

Collect state share of intergovernmental transfers

|

–34

|

|

Impose utilization limits and eliminate certain benefits

|

–16

|

|

Department of Mental Health

|

|

|

Shift support for mental health programs from General Fund to Proposition 63 funds

|

–763

|

|

Provide resources to improve safety and security in state hospitals

|

10

|

|

Expand psychiatric program at California Medical Facility—Vacaville

|

6

|

|

Provide funds to activate Stockton health care facility

|

1

|

|

Department of Developmental Services

|

|

|

Implement various cost–containment measures for community programs

|

–284

|

|

Extend provider payment reduction of 4.25 percent

|

–92

|

|

Assume additional federal funds from various initiatives

|

–78

|

|

Reduce funding for Developmental Centers

|

–28

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

|

|

Impose several measures to achieve public health savings

|

–8

|

|

Healthy Families Program

|

|

|

Implement unallocated reduction

|

–103

|

|

Increase premiums paid by families for children's health insurance

|

–22

|

|

Increase copayments for emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays

|

–6

|

|

Reduce the scope of the vision benefit

|

–3

|

We discuss the most significant spending changes that were adopted in the Medi–Cal Program budget in more detail below.

Provider Payment Reductions of Up to 10 Percent. The budget assumes $623 million in General Fund savings from reducing Medi–Cal provider payments by up to 10 percent for physicians, pharmacies, clinics, medical transportation, home health, family health programs, and other providers. The budget authorizes the director of DHCS to adjust these payment reductions based on studies of whether such reductions meet certain federal requirements. Implementation of this action requires federal approval.

Mandatory Copayments. The budget assumes $511 million in General Fund savings by imposing mandatory copayments on physician and clinic visits ($5), dental visits ($5), prescriptions ($3 for preferred drugs, $5 for non–preferred drugs), emergency and nonemergency use of emergency rooms ($50), and hospital inpatient visits ($100 per day, $200 maximum per admission). The copayments apply to all Medi–Cal enrollees and providers may deny the service if the enrollee does not make the copayment. Implementation of this action requires federal approval.

Unallocated Reduction. The spending plan includes a $345 million unallocated reduction to the Medi–Cal Program. A large portion of the unallocated savings may be achieved through the passage of pending legislation discussed above which would impose a quality assurance fee on hospitals potentially generating $320 million in General Fund relief.

Elimination of Adult Day Health Care Benefit. The spending plan assumes elimination of Adult Day Health Care (ADHC) as an optional Medi–Cal benefit for savings of about $170 million to the General Fund. The spending plan also provides up to $85 million from the General Fund to assist ADHC beneficiaries in transitioning to other services in order to minimize the risk of institutionalization. However, the Governor vetoed legislation that would have created a new type of ADHC program, to be called the Keeping Adults Free from Institutions Program, to provide services to eligible Medi–Cal beneficiaries who are at high risk of institutionalization. The Governor instead proposed to continue efforts to transition beneficiaries who previously received ADHC into other existing home and community–based services.

Fund Shifts and One–Time Funding Sources. The budget assumes one–time fund shifts and other one–time funding sources totaling $128 million to offset General Fund spending in the Medi–Cal Program. These funds include: (1) a $45.2 million shift from the Inpatient Payment Adjustment Fund, (2) a $32.7 million shift from Private Hospital Supplemental Fund, and (3) $50.1 million from a court settlement with Quest Diagnostics Inc. to reflect the repayment of alleged overcharges for testing services. The budget does not assume that a shift of $1 billion in Proposition 10 funds approved in a March 2011 budget action will be used to support Medi–Cal as had initially been proposed.

Managed Care Drug Rebates. The budget assumes savings of a benefit of $64 million to the General Fund from new authority to collect rebates from drug manufacturers for medications provided through Medi–Cal managed care plans.

"Soft Cap" on Physician and Clinic Visits. The budget assumes $41 million in General Fund savings through a soft cap on physician and clinic visits for adults. This utilization limit of seven annual visits can be waived through a physician certification that additional visits are medically necessary.

Other Utilization Limits and Benefit Eliminations. The budget assumes about $16 million in General Fund savings by limiting or eliminating some other Medi–Cal benefits. These changes include: (1) limiting enteral nutrition to tube feeding only for savings of almost $14 million, (2) eliminating Medi–Cal coverage for over–the–counter cold and cough products for savings of about $2 million, and (3) limiting annual hearing aid expenditures to $1,510 per person for savings of $229,000.

State Share of Intergovernmental Transfers. Counties and district hospitals may voluntarily transfer funds to DHCS under what are known as Intergovernmental Transfers (IGTs) for the purpose of providing increases in the rates paid to Medi–Cal managed care plans. The monies that counties and district hospitals transfer to the state draw down matching federal Medicaid monies, thus generating additional funding for managed care plans that ultimately is used to increase compensation for certain county– and district hospital–operated providers. Under the budget plan, entities that choose to submit these IGTs will pay a processing fee to the state equal to 20 percent of the IGTs. The estimated $34 million in fee revenues generated from this proposal will be used to offset General Fund costs in Medi–Cal.

Department of Mental Health

The budget plan provides about $4.6 billion from all fund sources for DMH programs. This is a decrease of about $310 million, or 6.3 percent, compared to the revised prior–year spending level. Between 2010–11 and 2011–12, General Fund spending will decrease from about $1.8 billion to $1.3 billion, or about 29 percent.

This year–over–year decrease in General Fund support is mainly due to the one–time use of $862 million in Proposition 63 (Mental Health Services Act) funds in lieu of General Fund monies to support three community mental health programs—EPSDT, MHMC, and so–called "AB 3632" mental health care for special education students. Another major factor affecting net General Fund expenditures for DMH programs was the expiration of the enhanced FMAP provided under ARRA and subsequent federal legislation which provided about $167 million in General Fund relief to mental health programs in 2010–11. We discuss below the most significant spending changes included in the DMH budget.

Administration States Intent to Eliminate DMH and Create State Hospitals Department. In presenting its budget plan, the administration stated its intent to eventually eliminate DMH based on its rationale that this would achieve administrative efficiencies and provide more focused leadership for behavioral health services. Part of the administration's plan is to create a new Department of State Hospitals, again based on its rationale that this would improve fiscal accountability, create safer hospitals, and achieve other benefits. The administration indicated it will provide its plan to accomplish these objectives along with its 2012–13 budget proposal.

Shift of Some Mental Health Programs to DHCS. Consistent with the administration's plan to eventually eliminate DMH, the budget plan transfers administrative responsibility for EPSDT and MHMC to DHCS by June 30, 2012. The DOF must notify the Legislature regarding various aspects of the shifts, including the number and classification of the positions to be transferred and any potential fiscal effects on the programs from which resources are being transferred. Furthermore, the administration is required to provide a transition plan to the Legislature by October 1, 2011. We note that EPSDT and MHMC are included in realignment. We discuss the details of realignment elsewhere in this report.

Proposition 63 Funds Used to Support Services for Special Education Students. The budget plan uses $99 million of Proposition 63 funds on a one–time basis to pay for mental health services for special education students. In the past, these services were supported in part with a General Fund appropriation in the DMH budget. Responsibility for providing these services is being shifted from the counties to the school districts as part of realignment. We discuss this shift in more detail earlier in this chapter.

Department of Developmental Services (DDS)

The 2011–12 budget provides $4.6 billion in total funds for DDS programs. This is a decrease of $113 million, or 2.3 percent, compared to the revised prior–year spending level. Between 2010–11 and 2011–12, General Fund spending will increase from about $2.5 billion to $2.6 billion, or about 7 percent. This net year–over–year increase in General Fund support is partly due to increases in caseload and utilization of services. Another major factor affecting net General Fund expenditures for DDS programs was the expiration of the enhanced FMAP provided under ARRA and subsequent legislation, which had provided about $386 million in fiscal relief in 2010–11. Below, we discuss the most significant spending changes that were adopted in the DDS budget.

Measures to Contain Costs and Improve Transparency and Accountability. The budget plan achieves $284 million in savings through a combination of measures to contain costs and improve transparency and accountability. For example, costs will be contained by implementing an annual family program fee for families with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty level (about $89,000 for a family of four in 2011). The budget plan also reflects about $110 million in savings from various measures to improve the transparency and accountability of the community services program.

Extension of Regional Center Provider Payment Reduction. The budget plan extends a 4.25 percent provider payment reduction that has been imposed in recent years in order to achieve $92 million in savings in 2011–12.

Assumption of Additional Federal Funds. The budget plan assumes $78 million in additional federal funds resulting from the following initiatives: (1) modifications to the state's Home and Community–Based Services program of community services for persons with disabilities ($60 million); (2) certification of Porterville Developmental Center to obtain federal Medicaid reimbursement for care provided to certain patients ($13 million), and (3) an increase in Money Follows the Person grants intended to help promote the shift of disabled persons from institutions to the community ($5 million).

Reduction in Funding for Developmental Centers (DCs). The budget plan includes several reductions to the DCs for a total of $28 million in savings. These reductions reflect the consolidation of residences and programs, reductions in funding for operations, and the elimination of funding for some DC staff.

Trigger Reductions. As noted earlier, the final 2011–12 budget included several reductions that would only be triggered if state General Fund revenue estimates are later determined to be too high. Effective January 2012, these trigger reductions include up to $100 million in unspecified savings in services for persons with developmental disabilities.

Department of Public Health (DPH)

The budget provides $3.5 billion from all fund sources for DPH programs. This is an increase of $188 million or about 5.6 percent compared to the revised prior–year spending level. Of this total, the spending plan provides $226 million from the General Fund for DPH, an increase of $40 million or 22 percent. This year–over–year increase is largely the result of increased General Fund support for ADAP.

Various Savings Measures. The budget plan includes several reductions to achieve a total of $8.3 million in General Fund savings in various public health programs. Funding reductions to Licensing and Certification, the Laboratory Field Division, the County Health Services Section, and operating expenses and equipment achieve combined savings of $4.5 million. Federal funds held in reserve for maternal and child health programs were redirected to offset $1.7 million in General Fund costs, and $1 million of General Fund support for a contract to support Valley Fever research was eliminated. The budget plan also reduces funding for the California Health Information Survey by $572,000 and for health care surge standby costs by $506,000.

Healthy Families Program (HFP)

The budget plan provides $286 million from the General Fund for HFP, which is administered by MRMIB. This is a General Fund increase of $160 million, or 127 percent, compared to the revised prior–year spending level. The major factors contributing to the year–over–year increase in General Fund support are: (1) an $81 million reduction in contributions from the First 5 California Children and Families Commission used to offset General Fund costs, (2) a $64 million reduction in the availability of revenues from a tax imposed on managed care organizations (MCOs) used to offset General Fund costs in 2010–11, and (3) increased costs of $34 million associated with implementing a new type of payment system for Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Centers that serve program beneficiaries. The spending plan also reflects several measures to reduce General Fund costs in HFP below:

- Increase in Monthly Premiums Paid by Families ($22 Million Savings). The amount of the monthly premium increases vary depending on family income levels.

- Increase in Copayments ($6 Million). The annual copayments for each family would be limited, as under prior program rules, to $250. The copayments established for HFP generally parallel those adopted in the budget plan for the Medi–Cal Program for emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays.

- Reduction in the Scope of Vision Benefit ($3 Million). The budget plan eliminates support for the vision benefit provided to children enrolled in HFP, in lieu of an administration proposal to entirely eliminate the vision benefit.

Unallocated Reduction. The spending plan includes a $103 million unallocated reduction to HFP. A proposed extension of the MCO tax described above, still under consideration by the Legislature, would provide an equivalent amount of money for the support of HFP in 2011–12.

Shift of Programs From MRMIB to DHCS. The budget plan authorizes DOF to transfer expenditure authority from MRMIB to DHCS to consolidate administrative functions for the operation of HFP and Access for Infants and Mothers Program. The DOF must notify the Legislature regarding various aspects of the shift, including the number and classification of the positions to be transferred and any potential fiscal effects on the programs from which resources are being transferred. The administration is required to provide a plan for the transfer of state administrative functions no later than December 1, 2011.

Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs

The budget provides $631 million from all fund sources for DADP programs. This is an increase of $25 million, or about 4 percent, compared to the revised prior–year spending level. Of this total, the budget package provides $222 million from the General Fund for DADP, an increase of $33 million, or 18 percent. The General Fund increase is due, in part, to the expiration of the enhanced FMAP provided under ARRA, which provided about $17 million in fiscal relief in 2010–11. The General Fund spending level for DADP identified above for 2011–12 does not take into account the realignment of most state–supported substance abuse treatment programs to the counties. Doing so would have the effect of reducing the 2011–12 General Fund spending level by $184 million. (The realignment package is discussed in more detail earlier in this chapter.) As part of the budget plan, the administration stated its intent to eventually eliminate DADP, citing what it views as a potential for greater administrative efficiencies and more focused leadership for behavioral health services.

Drug Medi–Cal Program Will Shift to DHCS. Consistent with the administration's plan to eventually eliminate DADP, administrative responsibility for the Drug Medi–Cal Program will be shifted to DHCS in 2011–12. The DOF must notify the Legislature regarding various aspects of the shift. Furthermore, the administration is required to provide a transition plan to the Legislature by October 1, 2011. We note that Drug Medi–Cal and some other programs administered by DADP are included in the realignment.

California Medical Assistance Commission (CMAC)

The budget plan requires CMAC to be dissolved after June 30, 2012. All of CMAC's powers, duties, and responsibilities would be transferred to the Director of DHCS along with CMAC executive and staff positions.

Social Services

Overview of Total Spending Excluding Realignment. General Fund support for social services programs in 2011–12 totals $9.1 billion, an increase of about $80 million, or 0.9 percent, compared to the revised prior–year level. This modest increase is due to higher costs in county administration and automation and the child welfare system, partially offset by reductions in Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program (SSI/SSP) grants. Figure 13 shows the change in General Fund spending in each major social services program and department, excluding the impact of realignment.

Figure 13

Major Social Services Programs and Departments

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

Change

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program

|

$2,860.8

|

$2,752.2

|

–$108.7

|

–3.8%

|

|

California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids

|

2,079.2

|

2,072.3

|

–6.9

|

–0.3

|

|

In–Home Supportive Servicesa

|

1,343.2

|

1,380.3

|

37.1

|

2.8

|

|

Child welfare systemb

|

1,510.3

|

1,590.8

|

80.6

|

5.3

|

|

County Administration/Automation

|

607.5

|

671.8

|

64.3

|

10.6

|

|

Department of Child Support Services

|

335.2

|

321.6

|

–13.6

|

–4.1

|

|

Department of Rehabilitation

|

54.1

|

55.1

|

1.0

|

1.9

|

|

Department of Aging

|

32.8

|

32.5

|

–0.3

|

–0.8

|

|

All other social services (including state support)

|

215.7

|

240.5

|

24.9

|

11.5

|

|

Totalsa

|

$9,038.7

|

$9,117.2

|

$78.4

|

0.9%

|

|

Estimated realignment savingsc

|

—

|

|

—

|

—

|

The Impact of Social Services Realignment on General Fund Spending. Budget legislation realigns 100 percent of most child welfare system costs, 100 percent of APS costs and about 34 percent of CalWORKs costs to counties. Under this realignment, General Fund support for these programs will be replaced by 2011 realignment special fund spending. After accounting for realignment, General Fund spending for social services programs in 2011–12 is reduced by about $2.7 billion, almost 30 percent below the revised spending level for 2010–11. The 2011 realignment plan is discussed in more detail earlier in this chapter.

Summary of Major Changes. Figure 14 shows the major General Fund changes adopted by the Legislature for social services programs. Most of the budget reductions were in the CalWORKs, In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS), and SSI/SSP programs. Absent the changes shown in the figure, total General Fund spending for social services programs in 2011–12 would have been almost $1.5 billion higher. Below, we discuss the major changes in each program area.

Figure 14

Major Changes—Social Services Programs2011–12 General Fund Effect

(In Millions)

|

Program

|

Amount

|

|

CalWORKs

|

|

|

Extend two–year county block grant reduction for an additional year

|

–$369.4

|

|

Reduce grants by 8 percent

|

–314.3

|

|

Establish 48–month time limit for adults

|

–102.9

|

|

Reduce earned income disregard

|

–83.3

|

|

Suspend Cal–Learn services for teen parents

|

–43.6

|

|

Limit license–exempt child care reimbursements to 60 percent

|

–30.6

|

|

Eliminate community challenge grants

|

–20.0

|

|

Reduce allocations for substance abuse/mental health and automation

|

–10.0

|

|

Repeal sanctions and time limits originally scheduled for July 2011

|

135.0

|

|

In–Home Supportive Services

|

|

|

Achieve long–term care savings through medication dispensing devices

|

–$140.0

|

|

Obtain additional federal funding through Community First Choice option

|

–128.0

|

|

Make health certification a condition of eligibility

|

–67.4

|

|

Reflect savings from lower than anticipated caseload

|

–53.7

|

|

End mandate for advisory committees

|

–1.5

|

|

Hold public authorities and counties harmless from caseload decline

|

7.1

|

|

Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program

|

|

|

Reduce grants to federal minimum for individuals

|

–$183.4

|

|

Foster Care

|

|

|

Shift responsibility for seriously emotionally disturbed children to schools

|

–$68.0

|

|

Reflect additional cost of court–imposed rate increase

|

17.4

|

|

County Administration and Automation

|

|

|

Delay Los Angeles county welfare system procurement

|

–$13.0

|

|

Suspend child welfare system procurement

|

–3.0

|

|

Department of Child Support Services

|

|

|