Executive Summary

Background. The Unemployment Insurance (UI) program provides weekly benefits for workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. The UI program is authorized in federal law, administered by California’s Employment Development Department (EDD), and is financed by contributions paid by employers.

Many States Face UI Fund Insolvency. Beginning in 2008, the UI funds of many states, including California’s, were under stress and soon became insolvent. To continue payment of UI benefits, many states sought loans from the federal government. As of June 2011, California’s outstanding federal loan totaled over $10 billion. The state is required to make interest payments on its federal loan, the first of which is expected to total $320 million and is due September 2011.

Federal Proposals Have Been Introduced to Correct UI Fund Insolvency. In response to UI fund insolvency in many states, three federal proposals have recently been introduced to address the insolvency issue. Two of these proposals introduce a comprehensive solvency plan aimed at ensuring the long–term solvency of states’ UI funds. In addition to providing a framework for achieving solvency, these two proposals would suspend state interest payments and federal UI tax increases on employers during the next two years. The third proposal includes significant changes to program financing in the short–term and tightens eligibility requirements which could substantially impact future costs of the UI program.

Federal Proposals Could Solve California’s UI Fund Deficit. All three of the recent federal proposals would improve the solvency of California’s UI fund. We find that the two comprehensive solvency plans would likely eliminate California’s UI fund deficit by 2016 and put California on track to develop a sizeable reserve by the end of the decade. This improved solvency would come through a significant increase in the UI employer contributions—amounting to a total increase of $13 billion between 2012 and 2018 compared to current law.

Pending Federal Proposals Complicate Difficult Choices for the Legislature. It is currently unclear whether any federal reforms will be enacted. This uncertainty complicates the Legislature’s decision as to how it should address the insolvency of its UI fund. By acting now, the Legislature could stop the growth of the UI fund deficit and reduce associated state interest costs. On the other hand, such actions have the disadvantage of increasing employment costs and/or decreasing aid to unemployed workers during what is likely to remain a difficult economic time for the state.

Ensure Long–Term Solvency of the UI Fund. Regardless of whether Congress acts to address the UI insolvency problems faced by California and other states, we recommend that the Legislature ensure implementation of a long–term solvency plan by 2014. If federal reforms are enacted, it is likely that no additional action by the Legislature will be necessary to ensure long–term solvency. However, if no federal reforms are enacted, it will be critically important for the Legislature to adopt its own long–term solvency plan. In developing such a plan, we recommend that the Legislature consider an approach which includes both increased employer contributions and decreased benefits for UI claimants.

Introduction

California’s UI fund has been insolvent since January 2009 and is expected to remain so for the foreseeable future. To continue payment of UI benefits, the state has obtained loans from the federal government which now total over $10 billion. In our October 2010 report, California’s Other Budget Deficit: The Unemployment Insurance Fund Insolvency, we discussed the issue of the UI fund insolvency in detail and examined potential solutions.

Many other U.S. states now face insolvency issues similar to California’s. In response, three proposals have been introduced in Congress pertaining to UI fund insolvency problems in California and the other states. In this report we provide a brief update to the status of the UI fund, describe the federal proposals, consider their impact on California, and discuss how the Legislature may wish to address the insolvency of the UI fund.

Background

The UI program, which provides weekly benefits to individuals who are unemployed through no fault of their own, was established under the federal Social Security Act of 1935. Although the program is authorized by federal law, much discretion is given to states to set benefit and employer contribution levels.

Program Benefits

Under state law, UI weekly benefit amounts are intended to replace up to 50 percent of a claimant’s earnings (defined as the wage replacement rate) during a 12–month base period—subject to statutory minimum ($40) and maximum ($450) limits. Regular UI benefits are paid for up to 26 weeks. However, during periods of high unemployment, additional extension programs are typically available. In addition to being unemployed through no fault of their own, claimants must meet additional monetary and nonmonetary eligibility requirements. To meet monetary eligibility requirements, a claimant must have earned (1) at least $900 in a single quarter, as well as $1,125 total in a 12–month base period or (2) at least $1,300 in any quarter in the base period. To meet nonmonetary eligibility requirements, a claimant must be able to work, be actively seeking work, and be willing to accept a suitable job if offered one.

Program Financing

The UI program is financed by unemployment tax contributions paid by employers for each covered worker. Unemployment contributions have a federal and a state portion—both levied on a taxable wage base of $7,000 in California. The federal portion of unemployment contributions is primarily used to fund administration at the state and federal level, while the state portion funds UI benefit payments. The federal unemployment tax rate is 6.2 percent. However, a state’s effective federal tax rate may be lowered to 0.8 percent as long as the state is in compliance with federal program requirements. (This is the case in California.) Compliance with federal requirements also allows the state to receive an annual federal grant to fund state administration of the UI program. State unemployment tax rates are set by a series of rate schedules ranging from AA (the lowest rates) to F+ (the highest). A rate schedule is selected annually based on the condition of the UI fund. Contributions have been set to the highest rate schedule (F+) since 2004.

The UI Fund Is Insolvent

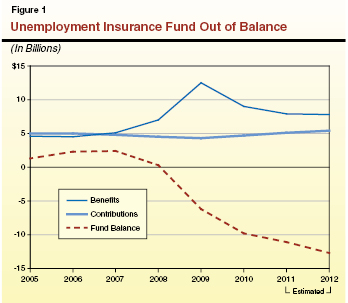

The UI fund became insolvent in January 2009 when benefit payments exceeded the available balance of the UI fund. By the end of 2009, the UI fund deficit totaled $6.2 billion. In 2010, benefit payments again exceeded UI fund revenues by $3.6 billion. As a result, the UI fund ended 2010 with a deficit of $9.8 billion. Current forecasts suggest that the deficit may continue to grow for several years without action to bring the fund into balance. As shown is Figure 1, the deficit is estimated to reach $12.7 billion by the end of 2012. While still substantial, this projected deficit is significantly less than previous EDD estimates. This reduction is due to a slightly improved outlook for California’s economy and the receipt of additional federal funds.

Several factors contributed to the insolvency of the UI fund, including an increase of UI benefits in 2001 without a corresponding change in the funding mechanism. Several years of worsening economic conditions resulted in historically high levels of benefit payments, pushing the fund deeper into the red.

Past Changes to UI Benefit Provisions. Between 1992 and 2001, UI weekly benefit payments covered up to 39 percent of a claimant’s previous weekly base period earnings—subject to a statutory maximum of $230. Chapter 409, Statutes of 2001 (SB 40, Alarcón), established the benefit levels currently in effect by instituting a phased increase of the wage replacement rate to 50 percent (effective January 2003) and an increase in the maximum weekly benefit amount to $450 (effective January 2005). This nearly doubled the maximum weekly benefit amount. The legislation did not provide for any changes to the UI financing mechanism to pay for these additional benefit costs.

UI Financing Structure Unable to Adjust for Increased Costs. As mentioned previously, the state unemployment tax rate is determined by a series of schedules ranging from AA (the lowest) to F+ (the highest). The effective schedule is adjusted annually based on the UI fund condition. The series of tax rate schedules is intended to allow flexibility in the UI financing structure to account for the cyclical nature of UI benefit payments. Fundamentally, the system of tax rate schedules is intended to allow the revenues flowing into the UI fund to increase in response to significant increases in UI benefit payments and decline during improved economic conditions. However, despite significant fluctuations in the state’s unemployment rate since 2004 (unemployment rates were less than 5 percent in 2006 and greater than 13 percent in 2010), UI tax rates have remained steady at schedule F+ (the highest schedule). Under the current statutory constraints on UI tax rates, the UI program’s financing structure can no longer adjust sufficiently to pay the increasing costs of the UI program.

The Costs of Insolvency

Since the UI fund became insolvent in January 2009, the state has received quarterly loans from the federal government in order to continue payment of UI benefits without interruption. As of June 2011, the state’s outstanding federal loan balance was about $10 billion. Absent corrective action, the state is expected to continue borrowing for the remainder of the decade, if not longer. Continual borrowing has negative ramifications for the state, particularly in the cost to the state of ongoing interest payments and increases in the effective federal unemployment tax rate on California employers.

Interest Payments. Under federal law, the state must pay interest on any federal loans to the UI fund that are not repaid within the same calendar year. Due to historically high levels of unemployment, and the financial pressure this situation placed on a number of states, Congress has suspended these interest payments in recent years. However, as of January 1, 2011, the state began accruing interest on its federal loan at an annual rate of roughly 4 percent. The state’s first interest payment, which is expected to be about $320 million, is due in September 2011. As federal law requires that these interest payments be made from state funds, the cost of the payments will likely fall on the state’s General Fund. Without changes to the UI program, interest payments on the federal loan are expected to be a significant cost to the General Fund for the foreseeable future. Figure 2 shows projected federal loan balances and the state’s interest costs absent corrective action. The amounts shown in Figure 2 were calculated by the EDD based on LAO’s economic assumptions. These figures are very similar in the short run to those contained in the EDD’s May 2011 forecast of the UI fund condition. However, in the long run, as the LAO’s economic forecast assumes slightly lower unemployment than the EDD, the figures differ from EDD’s forecast.

Figure 2

Federal Interest Payments Will Be a Significant Cost to the General Funda

(In Millions)

|

Year

|

Loan Balance

|

Interest Payment

|

|

2011

|

$10,108

|

$319

|

|

2012

|

11,714

|

448

|

|

2013

|

12,263

|

417

|

|

2014

|

11,598

|

370

|

|

2015

|

10,015

|

371

|

|

2016

|

7,719

|

348

|

|

2017

|

5,287

|

283

|

|

2018

|

2,745

|

185

|

Increased Federal Tax Rate. If a state carries a federal loan balance for two consecutive years, the state’s effective federal unemployment tax rate must begin to increase incrementally. In recent years, federal legislation has suspended this provision. However, absent further action by Congress in the coming months, the federal unemployment tax rate charged to California employers will increase as of January 1, 2012 by 0.3 percent because the state will continue to carry an outstanding loan balance. This incremental increase in the employer tax rate is expected to result in the collection of $300 million in additional contributions from employers in 2012. If the state continues to carry an outstanding loan balance, the federal tax rate will increase by an additional 0.3 percent each year through 2014, at which time the incremental increases would be larger. (Hereafter, we refer to these incremented tax increases as federal administration surcharges.)

Figure 3 details the annual increase in employer costs that are projected to result from the federal administration surcharges. Revenues from the surcharges are applied to the state’s outstanding federal loan balance.

Figure 3

Federal Administration Surcharges If Federal UI Loan Is Not Repaid

|

Year

|

Annual Surcharge Per Employee

|

Increase in Employer Cost (In Millions)

|

|

2012

|

$25

|

$304

|

|

2013

|

50

|

629

|

|

2014

|

78

|

985

|

|

2015

|

106

|

1,356

|

|

2016

|

135

|

1,745

|

|

2017

|

165

|

2,154

|

|

2018

|

195

|

2,565

|

Federal Proposals to Address UI Fund Insolvency

Three proposals have recently been introduced in Congress that would have a significant and sustained impact on UI programs in most states, including California. Two of the proposals offer comprehensive plans to resolve the UI fund insolvencies experienced by many states. In the short run (over the next three years) these two proposals would provide interest payment relief to the state’s General Fund and eliminate potential federal administration surcharges on California employers. In the long run, changes in the UI financing structure would be expected to put the UI fund on a path toward solvency and allow for repayment of the federal UI loan within five years. A third, less comprehensive, proposal would reduce federal support for extended UI benefits, transfer the federal savings to state UI funds, and make other changes affecting the eligibility of current program recipients. We outline all three of these proposals below.

President’s Proposal

The President’s 2012 federal budget includes a proposal to address UI fund insolvency in both the short and long term. The President’s proposal contains four key provisions: (1) suspending state interest payments on federal UI fund loans for two years, (2) suspending federal administration surcharges for two years, (3) increasing the federal minimum taxable wage base to $15,000 in 2014 and indexing the wage base to the change in the average annual wage in subsequent years, and (4) reducing the federal unemployment tax rate effective 2014.

Suspension of Interest Payments. As discussed, absent a change to federal law, the state will be required to make an interest payment of roughly $320 million in September 2011. In 2012, this interest payment is expected to grow to about $448 million. These costs are likely to be borne by the state of California’s General Fund. By suspending interest payments over the next two years, the President’s proposal would eliminate this cost to the General Fund, resulting in expected savings of over $750 million during the next two years.

Suspension of Federal Administration Surcharges. As a result of carrying a federal loan balance, under current federal law the effective unemployment tax rate on California employers would increase by 0.3 percent on January 1, 2012 and an additional 0.3 percent on January 1, 2013. The President’s proposal eliminates this increase in the federal tax rate for 2012 and 2013—avoiding increases in employer contributions in those years by $300 million and $630 million, respectively, that would otherwise be required.

Increase in the Taxable Wage Base. California currently collects employer contributions on the first $7,000 in annual wages paid per covered employee. This wage base is the minimum amount allowable under current federal law. The President’s proposal would more than double the minimum taxable wage base to $15,000 in 2014 for all states. In addition, the taxable wage base would then be indexed to the change in the average annual wage in subsequent years. This proposed increase in the taxable wage base is somewhat less than the increase in the average annual wage since 1983, the year in which the federal taxable wage base was last adjusted.

Reduction in the Federal Unemployment Tax Rate. As discussed previously, the UI tax rate charged to California employers has both a state and federal portion which are both charged on the federal minimum taxable wage base. Absent a change in the state portion of the UI tax rates, the President’s proposed increase in the taxable wage base would significantly increase the state portion of UI employer contributions. However, the President’s proposal avoids a net increase in the federal portion of UI employer contributions by roughly halving the federal unemployment tax rate.

Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act

The proposed Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act of 2011, introduced to the U.S. Senate on February 17, 2011, sets forth a solvency plan that is identical to the President’s except for two additional provisions. Both of these provisions are intended to provide greater incentives for states to ensure the solvency of their UI funds in the future. These additional provisions are: (1) a mechanism for partial forgiveness of federal loans to state UI funds and (2) reduced federal tax rates and increased interest earnings for states that meet certain solvency targets. Below is a brief description of these additional provisions.

Federal Loan Abatement. The legislation includes a so–called abatement provision which would forgive as much as 60 percent of a state’s outstanding federal loan if it agreed to meet specific UI fund solvency targets. To do so, the state would work with the U.S. Department of Labor to construct a solvency plan which would allow the state to: (1) repay any remaining outstanding federal loan balance and (2) improve the state’s UI fund solvency to a level such that reserves would be adequate to pay one year of UI benefits even if they were at historically high levels. (Technically, this level of solvency is defined as an average high cost multiple [AHCM] of 1.0. See the nearby box for additional discussion of AHCM.) During the effective period of the abatement agreement (no longer than seven years), the state would not be allowed to lower UI benefit levels or adopt more stringent UI eligibility requirements.

Rewards for Solvent States. The federal government currently pays states interest whenever there are positive balances in their UI funds. For example, the federal government deposited $98 million in earned interest into the state’s UI fund in 2008 (a period before California’s UI fund became insolvent). To encourage states to improve UI fund solvency to an AHCM of 1.0, the act increases the interest paid on UI fund balances by 0.5 percent for those states that meet this solvency target. In addition, states meeting the act’s requirements would be provided a reduction in their effective federal unemployment tax rate. Potentially, these rate reductions would decrease federal unemployment taxes for California employers by hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Average High Cost Multiple (AHCM)

The AHCM is a widely used metric of Unemployment Insurance (UI) fund solvency which measures the number of years a UI fund could pay benefits at recessionary levels without additional UI employer contributions. The U.S. Department of Labor has concluded that an AHCM equal to 1.0—whereby a state would be able to pay one year of historically high benefits without additional revenue—represents a minimum acceptable level of solvency. Evidence from the most recent recession (December 2007 to June 2009) provides some support for this conclusion. Immediately prior to the recession, six states had an AHCM of 1.0 or greater. Of these, only one had to obtain a loan from the federal government as a result of the recession. Overall, 32 states had to obtain federal loans. The average AHCM of states that received a federal loan was 0.39, as compared to 0.83 for states that did not receive a federal loan.

Calculation of AHCM. The AHCM is calculated in three steps:

- Calculate what is known as a reserve ratio. A reserve ratio is calculated by dividing the balance of the state’s UI fund by the total wages paid to covered employees in the preceding twelve months.

- Calculate what is known as an average high cost rate. This calculation proceeds in two steps: (1) for each of the preceding 20 calendar years, the amount of benefits paid is divided by the total wages paid to covered employees and (2) the highest three values are averaged.

- Divide the reserve ratio by the average high cost rate.

By comparing the reserve ratio and the average high cost rate, the AHCM reports the duration for which current fund balances could cover benefit costs if they were at historically high levels.

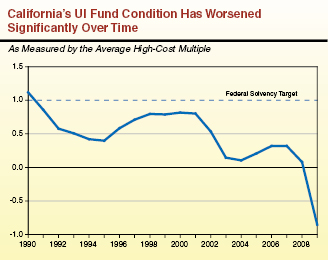

AHCM of 1.0 a Historically High Target for California. As shown on the nearby graph, California’s UI fund solvency has been trending downward significantly over the past 20 years. The state has not achieved an AHCM of at least 1.0 since 1990. Since full implementation of the state’s most recent statutory increase in UI benefits (passed in 2001), the state’s AHCM has not exceeded 0.32.

|

JOBS Act

Although the proposed Jobs, Opportunity, Benefits and Services (JOBS) Act, introduced in both houses of the U.S. Congress on May 5, 2011, is not intended to be a plan to return states UI funds to solvency it would make two significant changes to the UI program.

Proposed Block Grant. When the federal government extends unemployment benefits beyond the state–authorized 26 weeks, it generally pays for most, if not all, of the benefit costs. Currently, unemployed Californians may receive up to 99 weeks of benefits, with the final 73 weeks funded by the federal government. The proposed JOBS act replaces the funding now used for extended benefits with federal block grants and relieves states of the obligation to provide extended benefits. The block grants could be used for (1) continued payment of extended benefits if a state elected to provide them, (2) payment of regular UI benefits, (3) repayment of federal UI loans, and (4) reemployment services. Preliminary calculations based on the most recent available data suggest California would receive block grants of around $1.8 billion and $2.6 billion, in 2011 and 2012 respectively. According to EDD projections, these block grant amounts would slightly exceed the anticipated federal costs for extended benefits for California claimants in these years.

Additional Eligibility Requirements. As discussed previously, California’s UI program must meet specific federal requirements in order to qualify for a reduced effective federal UI tax rate and annual federal grants to administer the UI program. Another major change proposed by the JOBS Act is to add two provisions to these federal requirements related to non–monetary eligibility requirements for receipt of UI benefits. The current federal requirement that UI claimants be “actively seeking work” to receive benefits would be amended to specifically require that all claimants register for state administered employment services (programs which provide job search assistance to unemployed workers) and post a resume in a state–maintained database. Moreover, as a condition of receiving UI benefits, all claimants would be required to have earned a high school diploma or General Educational Development credential or be making satisfactory progress in classes toward such credentials. Although insufficient data exists to quantify the impact of these eligibility requirements, it is likely that they would result in a significant overall reduction in the number of California workers eligible to receive benefits.

Evaluating the Federal Proposals

The federal proposals would likely have significant impacts on California’s UI program, as well as California’s economy. To explore these impacts, we have examined and compared forecasts of the UI fund condition under current law and the President’s proposal.

Because of technical complications, we were unable to model the loan abatement provisions of the Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act. However, due to the similarity between the President’s proposal and the Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act, it is likely that the act would result in a similar or slightly improved level of UI fund solvency as compared to the President’s proposal. Moreover, we were unable to model the impacts in California of the JOBS Act because its ultimate impact on the solvency of California’s UI fund would be dependent upon the state’s use of block grants and the degree to which the new eligibility requirements described above would reduce the number of workers eligible to receive benefits. Our review indicates that the measure would likely improve the condition of California’s UI fund but not restore it to solvency.

Our forecasts of the UI fund condition under the President’s proposal go out seven years and are based on the LAO’s current economic outlook. In general, the LAO’s economic outlook assumes a gradual and sustained recovery. It is important to note that these forecasts are very sensitive to changes in future economic conditions as both employer contributions and benefits paid fluctuate with changes in the unemployment rate. Below, we compare the President’s proposal to current law in the areas of UI fund solvency, state interest costs, and impacts on employment costs.

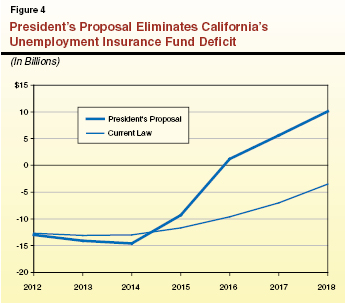

UI Fund Balance

If no action is taken to address the UI fund deficit, the fund is likely to maintain a negative balance through the remainder of the decade. In contrast, our forecast indicates that the President’s proposal would eliminate the UI fund deficit by 2016. In addition, under the President’s plan, the UI fund would accumulate a reserve of about $10 billion by the end of 2018. In Figure 4 we display how the balance of the UI fund would change under both the President’s proposal and current law over the period 2012 to 2018.

Under the President’s proposal, the UI fund deficit is projected to peak in 2014, while under current law it is projected to peak in 2013. As the President’s proposal suspends federal administration surcharges until 2014, the maximum deficit is actually higher under the President’s proposal ($14.6 billion) than under current law ($13.2 billion). However, beginning in 2014 the pace of improvement in the UI fund is much greater under the President’s proposal than current law. Between 2014 and 2018, the UI fund deficit is expected to decrease by an average of $2.2 billion per year under current law, as compared to an average of $5.2 billion per year under the President’s proposal. As a result, the President’s proposal is projected to have a positive UI fund balance of about $10.1 billion by the end of 2018, whereas under current law there would be a deficit of $3.5 million at the end of this period.

State Interest Costs

As previously discussed, without corrective action the state will face significant ongoing interest costs due to continued federal borrowing. Under current law, these interest payments would be hundreds of millions of dollars annually and total almost $3 billion through 2018. However, as shown in Figure 5, these interest costs would be significantly reduced under the President’s proposal. Suspension of interest payments in 2011 and 2012 would reduce state interest costs by a total of $767 million. In addition, as it is anticipated that the federal loan would be repaid by 2016 under the President’s proposal, the state would not incur any interest costs in 2016 or succeeding years. Interest savings during this period would amount to around $800 million. Altogether, state interest costs during the period 2011 to 2018 would be about $1.7 billion less under the President’s proposal than under current law.

Figure 5

Comparison of UI Interest Payments Under Current Law and President’s Proposal

(In Millions)

|

Year

|

Current Law

|

President’s Proposal

|

|

2011

|

$319

|

—

|

|

2012

|

448

|

—

|

|

2013

|

417

|

$443

|

|

2014

|

370

|

383

|

|

2015

|

371

|

259

|

|

2016

|

348

|

—

|

|

2017

|

283

|

—

|

|

2018

|

185

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$2,741

|

$1,086

|

Increased Employer Contributions

Figure 6 details total annual employer contributions to the UI fund under the President’s proposal and under current law. The President’s proposal would result in a considerable increase in total employer contributions to the UI fund—about $13 billion over the forecast period. In the next two years, however, the President’s proposal would result in a small reduction in total employer contributions due to the elimination of the federal administration surcharge.

Figure 6

Comparison of UI Employer Contributions Under Current Law and President’s Proposal

(In Billions)

|

Current Law

|

|

President’s Proposal

|

|

Year

|

Base Contributions

|

Federal Administration Surcharge

|

Total Contributions

|

|

Base Contributions

|

Federal Administration Surcharge

|

Total Contributions

|

|

2012

|

$5.4

|

$0.3

|

$5.7

|

|

$5.4

|

—

|

$5.4

|

|

2013

|

5.4

|

0.6

|

6.0

|

|

5.4

|

—

|

5.4

|

|

2014

|

5.6

|

1.0

|

6.6

|

|

9.0

|

$0.3

|

9.3

|

|

2015

|

5.7

|

1.4

|

7.1

|

|

9.8

|

1.2

|

11.0

|

|

2016

|

5.8

|

1.7

|

7.5

|

|

9.5

|

1.9

|

11.4

|

|

2017

|

5.8

|

2.2

|

8.0

|

|

9.7

|

—

|

9.7

|

|

2018

|

5.8

|

2.6

|

8.4

|

|

10.2

|

—

|

10.2

|

|

Totals

|

$39.5

|

$9.8

|

$49.3

|

|

$59.0

|

$3.4

|

$62.4

|

Figure 7 compares annual employer contributions per employee and effective tax rates (total employer contributions as a percent of total wages) under the President’s proposal and under current law. In 2012 and 2013, both the contributions per employee and effective tax rates on employers would be slightly lower under the President’s proposal than under current law. However, for 2014 through 2016 contributions per employee and effective tax rates would increase roughly 40 percent over those required under current law.

Figure 7

Comparison of UI Employer Costs Under Current Law And President’s Proposal

|

Current Law

|

|

President’s Proposal

|

|

Year

|

Contributions Per Employee

|

Effective Tax Rate

|

|

Contributions Per Employee

|

Effective Tax Rate

|

|

2012

|

$467

|

0.91%

|

|

$442

|

0.86%

|

|

2013

|

480

|

0.91

|

|

430

|

0.81

|

|

2014

|

517

|

0.95

|

|

739

|

1.46

|

|

2015

|

549

|

0.96

|

|

853

|

1.49

|

|

2016

|

579

|

0.97

|

|

881

|

1.47

|

|

2017

|

606

|

0.97

|

|

742

|

1.19

|

|

2018

|

637

|

0.97

|

|

775

|

1.18

|

During the period from 2014 to 2018, annual employer contributions to the UI fund under the President’s proposal are expected to exceed benefits paid to recipients, which would allow the state to repay its federal loan and build a reserve. After 2018, as the state builds a sufficient reserve, it would likely result in a decrease in the employer contribution rate schedule, which would reduce employer contributions in the out–years.

Benefits and Drawbacks of the President’s Proposal

While the President’s proposal would make significant progress in improving the health of California’s UI fund, it does have potential drawbacks. Below, we briefly summarize the potential benefits and drawbacks of the President’s proposal.

Benefits of the President’s Proposal. The most immediate benefit of the President’s proposal is that it avoids negative impacts on the state, UI claimants, or employers over the next two years, a period during which unemployment is expected to remain high. The President’s proposal achieves this by suspending both state interest payments in 2011 and 2012 and federal administration surcharges on employers in 2012 and 2013, while maintaining current UI benefit levels for claimants.

Also, the solvency of California’s UI fund would increase dramatically under the President’s proposal. By 2018, the UI fund could be expected to have a balance of about $10 billion. This balance would represent an AHCM of 0.71, which would be the highest level of UI fund solvency since 2001. The improved solvency of the UI fund would be expected to save the state $1.7 billion in General Fund costs during the 2012 to 2018 period.

Drawbacks of the President’s Proposal. The President’s proposal relies exclusively on increased employer contributions to address UI fund insolvency. A potential drawback of such a strategy is that it fails to spread negative impacts across all parties. Rather, the proposal’s direct impacts are focused on employers in the form of increased employment costs. While these increased employment costs are imposed directly on employers, a significant portion of these impacts would ultimately be passed along to workers in the form of reduced hiring and decreased wages. All other things being equal, we believe that higher employer contributions will reduce, to some extent, the employment gains that are likely to occur as the economy recovers.

What Should the Legislature Do Now with Potential Federal Action Pending?

The insolvency of California’s UI fund poses significant problems for California. Absent reform of the UI program, payments from the UI fund are expected to continue to exceed revenues, resulting in continued borrowing from the federal government and associated state interest costs. As described in the previous section, two federal proposals have been introduced which would likely eliminate California’s UI fund deficit and establish a significant reserve by the end of the decade without the need for additional state action. However, it is currently unclear whether these, or any other congressional solvency legislation, will be enacted. This uncertainty complicates the Legislature’s decision as to how it should address the insolvency of the UI fund. Below, we provide guidance for the Legislature in managing the insolvency issue in light of potential federal actions.

Consider Early Action

In October 2010, prior to the introduction of the federal proposals described previously, we recommended that the Legislature take prompt action to stop the growth of the UI fund deficit. In our report, California’s Other Budget Deficit: The Unemployment Insurance Fund Insolvency, we argued that by doing so the Legislature could mitigate state interest costs and minimize the overall problem that ultimately must be addressed with future comprehensive reform. While the potential benefits of immediate state legislative action remain significant, we note that two recent developments now also need to be taken into account. These are the potential actions by Congress to address the states’ UI insolvencies as well as an improvement in the outlook of California’s UI fund since the publication of our October 2010 report.

Potential Interim Actions. If the Legislature wishes to act now to stop growth in the UI fund deficit, it would need to bring UI fund revenues and benefit payments into balance. If no federal actions are taken, the annual gap between revenues and benefit payments is anticipated to be $1.6 billion and $0.5 billion in 2012 and 2013, respectively. The Legislature has three primary options for eliminating this gap: (1) increasing employer contributions, (2) decreasing benefits paid to UI claimants, or (3) a combination of the first two options. For example, increasing the taxable wage base to $11,000 in 2012 and 2013 would bring annual revenues and spending in line, thereby stopping growth in the UI fund deficit during this period. Decreasing the maximum weekly benefit amount from $450 to $400 along with a reduction in the wage replacement rate from 50 percent to 45 percent would achieve the same end. Alternatively, the Legislature could moderate the above changes by combining increased employer contributions with decreased benefits. In selecting among these options, the Legislature should carefully weigh the effects of each option on various parties within the UI system—employers, employees, and unemployed workers.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Early Action. By acting now to stop growth in the UI fund deficit, the Legislature could reduce ongoing annual state interest costs by about $50 million. Also, the magnitude of the problem that must be solved by future reforms would be reduced by about $2 billion. However, taking immediate action has the disadvantage of increasing employment costs and/or decreasing aid to unemployed workers during what is likely to remain a difficult economic time for the state. In addition, pending federal proposals could make any state actions unnecessary. For this reason, the Legislature may instead wish to take a wait–and–see approach during 2011 and 2012 until it is clear what actions Congress has taken.

Adopt a Long–Term Solvency Plan

Although a wait–and–see approach may be appropriate during the next two years, we recommend that the Legislature ensure that implementation of a long–term solvency plan begins no later than 2014. If federal reforms—such as the President’s proposal—are ultimately enacted, it is likely that the no additional action will be required of the Legislature to ensure long–term solvency of the UI fund. However, depending on the future condition of California’s labor market, the Legislature should evaluate the composition of federal reforms to determine if further state action is warranted.

If federal reforms are not enacted in the next two years, we recommend that the Legislature adopt its own comprehensive solvency plan. While the Legislature has several options for doing so, we recommend that it consider a plan that combines increased employer contributions and decreased benefits for UI claimants. We believe such an approach offers a reasonable trade–off between the impacts of increased employment costs and reduced assistance for unemployed workers. Below, we outline one such solvency plan.

Description of the Plan. Under our proposed approach, employer contributions would be increased in an identical manner to the President’s proposal. The taxable wage base would be increased from $7,000 to $15,000 and indexed to the average annual wage in subsequent years. Our approach would go further than the President’s by taking three actions to reduce UI benefit levels. These actions are: (1) reducing the maximum weekly benefit amount from $450 to $375, (2) increasing the 12–month monetary eligibility requirement from $1,125 to $4,000, and (3) reducing the wage replacement rate from 50 percent to 45 percent. Similar to the taxable wage base, the maximum weekly benefit amount would be indexed to the average annual wage in subsequent years. We note that, due to indexing, the maximum weekly benefit amount would be expected to return to around $450 within five years.

The Major Impacts of the Plan. As mentioned above, if our approach were implemented in 2014, it would likely result in the elimination of the UI fund deficit by 2016 and the establishment of a significant UI fund reserve by 2018. This would be accomplished by increasing employer contributions by a total of about $11 billion and decreasing benefit payments by a total of about $4 billion during the period 2014 to 2018, as compared to current law. Consequently, the average employer contribution per employee would increase by roughly 60 percent during this period, while the average weekly benefit paid to UI claimants would decrease by about 12 percent. Under this approach, state interest costs would be reduced by $1.3 billion. Overall, this approach is intended to return California’s UI fund to solvency in a timely manner while balancing the impacts of increased employment costs and reduced assistance for unemployed workers.