Major Expenditure and Other Budget Actions

The previous chapter described the state’s overall budget situation under the 2012–13 budget plan, as well as the tax provisions of Proposition 30. This chapter provides more detail on the expenditure and other budget actions included in the spending plan.

Proposition 98 funding is the main funding source for K–12 education and the California Community Colleges (CCC). Proposition 98 funding also fully supports the state’s subsidized preschool program. In this section, we (1) review the changes in the 2011–12 Proposition 98 budget, (2) describe the major factors that affect the minimum guarantee in 2012–13, (3) summarize the major Proposition 98 components of the 2012–13 budget package if Proposition 30 goes into effect, and (4) discuss the Proposition 98 reductions that would be triggered if the tax increases included in Proposition 30 do not go into effect. In the subsequent three sections, we discuss in more detail the budgets for K–12 education, child care and preschool, and higher education, respectively. (In addition, the online version of this report contains a link to a packet of detailed tables relating to various aspects of the education budget.)

2011–12 Spending Essentially Unchanged From 2011–12 Budget Act

Drop in 2011–12 Minimum Guarantee Primarily Due to Lower Revenues. As shown in Figure 1, the 2011–12 minimum guarantee decreased by roughly $2.2 billion due to General Fund revenues being lower than estimated in the 2011–12 Budget Act. The guarantee decreased by an additional $609 million due to eliminating the rebenching for the “gas tax swap” adopted by the Legislature in 2011. These reductions in the guarantee were partly offset by an increase associated with attributing (or, accruing) some of the new revenues from Proposition 30 to the 2011–12 fiscal year. After adjusting for all of these changes, 2011–12 Proposition 98 spending was $893 million above the revised estimate of the minimum guarantee.

Figure 1

Major Adjustments to Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

2011–12 Budget Act

|

$48,651

|

|

Update for changes in baseline revenues

|

–$2,220

|

|

Update for changes in other Proposition 98 factorsa

|

–339

|

|

Eliminate gas tax rebenching

|

–609

|

|

Use consistent rebenching approach

|

103

|

|

Add Governor’s new revenues accrued to 2011–12

|

1,330

|

|

2011–12 Revised

|

$46,916

|

|

Baseline growth

|

$3,702

|

|

Add Governor’s new revenues attributed to 2012–13

|

2,878

|

|

Additional student mental health services rebenching

|

99

|

|

2012–13 Budget Act

|

$53,595

|

Plan Redesignates Funds Provided Above Minimum Guarantee. Total spending for schools and community colleges in 2011–12 is essentially unchanged from the level in the 2011–12 Budget Act. To bring ongoing Proposition 98 spending down to the lower minimum guarantee, however, the budget package reclassifies $893 million of 2011–12 appropriations above the guarantee. Of the amount reclassified, $672 million is counted toward meeting a statutory obligation associated with 2004–05 and 2005–06 and the remaining $221 million replaces ongoing Proposition 98 funds with one–time Proposition 98 funds unspent from prior years. These accounting adjustments do not affect the amount of funding school districts and community colleges receive.

Higher General Fund Spending Due to Lower Redevelopment Property Taxes. The 2011–12 Budget Act assumed $1.7 billion in redevelopment–related property tax revenues would flow back to school districts and community colleges. The updated budget package assumes only $133 million in associated revenues will flow back in 2011–12. If these revenues do not materialize, the budget plan would backfill school districts and community colleges with additional General Fund monies.

2012–13 Minimum Guarantee Substantially Higher Than 2011–12

Minimum Guarantee Higher Primarily Due to Revenues From Tax Measure. As shown in Figure 2, the 2012–13 minimum guarantee increases from $46.9 billion to $53.6 billion, an increase of $6.7 billion. Of this amount, $3.7 billion is due to growth in baseline revenues and $2.9 billion is due to the new revenues assumed from Proposition 30. The budget plan also increases the minimum guarantee by $99 million to account for additional Proposition 98 funding being provided for student mental health services. The significant year–to–year increase in the minimum guarantee is partly driven by the manner in which the budget plan makes maintenance factor payments, which results in a larger share of new revenues being dedicated to Proposition 98.

Programmatic Spending Roughly Flat

As Figure 2 shows, Proposition 98 funding grows to $53.5 billion in 2012–13, a $6.6 billion increase from 2011–12. (Proposition 98 spending under the budget plan is $46 million below the minimum guarantee as a result of vetoes by the Governor.) Of this increase in spending, $3.7 billion is supported by the General Fund and $2.9 billion is supported by local property tax revenues. Although local property tax revenues not related to redevelopment decrease somewhat in 2012–13, the budget plan assumes large increases in redevelopment–related property tax revenues. Specifically, the budget plan assumes $1.7 billion in ongoing redevelopment property tax revenues and $1.5 billion in one–time property tax revenues from the transfer of liquid assets from the former redevelopment agencies (RDAs) to school districts and community colleges. (For more information, see the “Redevelopment Agencies” section later in this report.)

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

Change From 2011–12

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$29,995

|

$29,361

|

$32,828a

|

$3,468

|

12%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

12,191

|

11,856

|

14,342

|

2,487

|

21

|

|

Subtotals

|

($42,186)

|

($41,216)

|

($47,170)

|

($5,954)

|

(14%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,885

|

$3,279

|

$3,415a

|

$136

|

4%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

1,965

|

1,971

|

2,403

|

432

|

22

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,850)

|

($5,251)

|

($5,818)

|

($568)

|

(11%)

|

|

Preschool

|

$380

|

$368

|

$481

|

$113

|

31%

|

|

Other Agencies

|

87

|

82

|

79

|

–3

|

–3

|

|

Totals, Proposition 98

|

$48,503b

|

$46,916

|

$53,549c

|

$6,633

|

14%

|

|

General Fund

|

$34,346

|

$33,089

|

$36,804a

|

$3,714

|

11%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

14,157

|

13,827

|

16,745

|

2,918

|

21

|

Virtually All Additional Spending Used for Existing Obligations. Although Proposition 98 spending increases substantially from 2011–12 to 2012–13, most of the additional funding is used to pay for existing Proposition 98 obligations. As Figure 3 shows, $3.3 billion is needed to backfill one–time actions made in 2011–12 and $2.2 billion is used to pay down existing K–14 deferrals (reducing total outstanding deferrals from $10.4 billion to $8.2 billion). Several other Proposition 98 spending increases also have no programmatic effect. The package, for example, uses: $110 million to more closely align K–14 mandate funding with anticipated costs, $99 million to complete the shift of student mental health services to schools, and $60 million for anticipated student growth in a few existing programs. The package also funds the existing Quality Education Investment Act and State Preschool Program from within Proposition 98 rather than from other fund sources. (We discuss the major changes to the preschool program in the “Child Care and Preschool” section of this report.)

Figure 3

Major 2012–13 Proposition 98 Spending Changes

(In Millions)

|

|

|

|

Technical Changes:

|

|

|

Backfill one–time actions

|

$3,334

|

|

Make revenue limit adjustments

|

238

|

|

Backfill Proposition 63 mental health funding

|

99

|

|

Fund growth in certain categorical programsa

|

60

|

|

Other adjustments

|

–25

|

|

Subtotal

|

($3,705)

|

|

Policy Changes:

|

|

|

Pay down K–14 deferrals

|

$2,225

|

|

Fund QEIA program within Proposition 98

|

361

|

|

Fund all preschool slots within Proposition 98

|

164

|

|

Create K–14 mandate block grant

|

110b

|

|

Backfill for lower CCC fee revenues

|

82

|

|

Fund CCC enrollment growth (0.9 percent)

|

50

|

|

Reduce preschool slots and collect family fees

|

–50

|

|

Eliminate Early Mental Health Initiative

|

–15

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2,928)

|

|

Total Changes

|

$6,633

|

Trigger Reductions if Proposition 30 Does Not Take Effect

As discussed earlier in this report, the 2012–13 Budget Act includes a backup plan that makes $6 billion in trigger cuts if Proposition 30’s tax increases do not go into effect. The vast majority of those reductions are made to K–14 education. We discuss the Proposition 98 backup plan in more detail below.

If Proposition 30 Does Not Take Effect, Debt Service and Early Start Program Shifted Into Proposition 98. As shown in Figure 4, if the tax increases in Proposition 30 do not go into effect, the backup plan pays for K–14 facility debt service ($2.5 billion) and the Early Start program ($197 million) using Proposition 98 funds. These shifts increase Proposition 98 costs by $2.7 billion. (As part of the debt service shift, the budget package adjusts the 2012–13 minimum guarantee upward by $190 million. It makes no adjustment in the minimum guarantee to reflect the shift of the Early Start program.)

Figure 4

Proposition 98 Trigger Reductions

(In Millions)

|

|

|

|

New Proposition 98 Spending:

|

|

|

Fund K–14 debt service payments within Proposition 98

|

$2,518

|

|

Fund Early Start program within Proposition 98

|

197

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2,715)

|

|

Proposition 98 Reductions:

|

|

|

Rescind K–12 deferral pay downs

|

–$2,065

|

|

Rescind CCC deferral pay downs

|

–160

|

|

Reduce K–12 revenue limits

|

–2,740

|

|

Reduce CCC apportionments

|

–339

|

|

Rescind apportionment funds for CCC enrollment growth

|

–50

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$5,354)

|

|

Total Changes

|

–$2,639

|

Total Reductions of $5.4 Billion to Schools and Community Colleges. The backup plan includes $5.4 billion in trigger cuts to Proposition 98 funding in 2012–13 to address the drop in General Fund revenues and the shift of additional programs into Proposition 98 if the Governor’s tax measure is not implemented. Figure 4 itemizes these reductions. The backup plan rescinds the proposal to pay down outstanding K–14 payment deferrals, resulting in $2.2 billion in General Fund savings. The rescinding of these payments would have little programmatic effect, but it may require some school districts and community colleges to increase their short–term borrowing. The backup plan also includes $3.1 billion in programmatic reductions—$2.7 billion to K–12 revenue limits and $389 million to community college apportionments. Of the community college reduction, $50 million would eliminate funding provided to serve additional students in 2012–13. To accommodate the programmatic reductions, the budget plan allows school districts to reduce the school year by an additional 15 days in both 2012–13 and 2013–14. Any reductions in instructional time and accompanying reductions in teacher costs, however, would need to be achieved by school districts through the collective bargaining process.

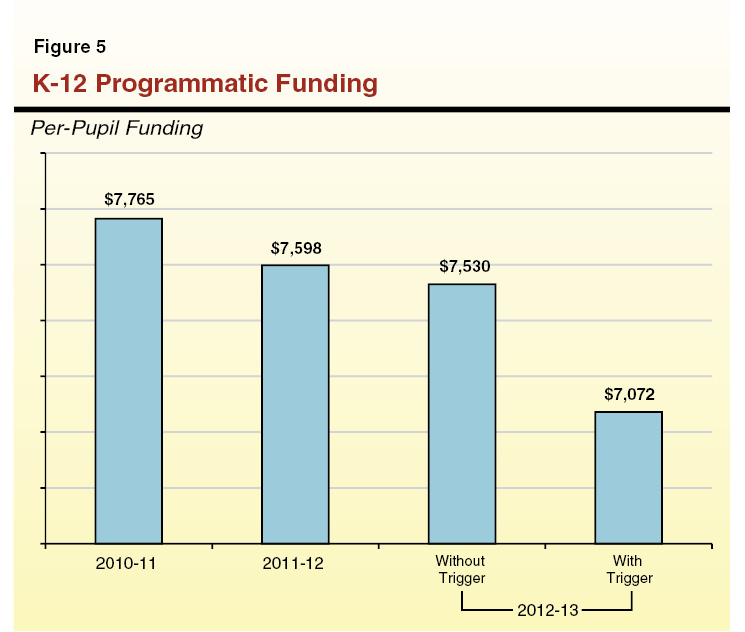

Spending Roughly Flat, Though Down 6 Percent Under Trigger Plan. Figure 5 displays K–12 per–pupil programmatic spending from 2010–11 through 2012–13. As the figure shows, if the Governor’s tax measure is implemented, per–pupil funding in 2012–13 will decrease slightly from $7,598 to $7,530, a drop of less than 1 percent from the prior year. This slight decrease is primarily due to the loss of federal “Education Jobs” funds that were available for school districts to spend in 2010–11 and 2011–12. This 2012–13 per–pupil spending level is about 9 percent less than the prerecession 2007–08 level. By comparison, if the trigger reductions are implemented, per–pupil funding will decrease to $7,072, a 6 percent decrease from the prior year and a 14 percent decrease from the prerecession 2007–08 level.

Mandate Block Grant Adopted. The 2012–13 budget includes $167 million for a new discretionary block grant for K–12 mandates. School districts, charter schools, and county offices of education (COEs) may apply for mandate block grant funding. School districts and COEs that choose to participate in the block grant are to receive $28 per average daily attendance (ADA), whereas charter schools are to receive $14 per ADA. In addition, COEs are to receive $1 per ADA for all ADA served within the county. In lieu of participating in the block grant, local educational agencies could continue to seek reimbursement for mandated activities through the existing mandates claiming process. (The enacted budget appropriates a total of $41,000 for agencies that opt to submit claims for reimbursement.) The budget continues to suspend the same mandates in 2012–13 that were suspended in 2011–12 and does not eliminate any K–12 mandates.

Final Shift of Student Mental Health Service Funding. The budget plan provides an additional $99 million to complete the shift in responsibility of student mental health services from county mental health agencies to school districts. The additional funding backfills for the loss of $99 million in one–time Proposition 63 funds that were provided in 2011–12.

Various Changes to Increase Charter School Access to Facilities and Short–Term Cash. The budget package includes several changes to existing law that provide charter schools with additional access to facility space and short–term cash. The plan includes provisions that give charter schools priority to lease or purchase properties that have been deemed “surplus property” by a school district. In addition, the budget package authorizes COEs and county treasurers to provide short–term loans to charter schools. The plan also allows charter schools to issue their own tax revenue anticipation notes (TRANs) or have a COE issue a TRAN on their behalf.

Governor Vetoes Funding for Certain K–12 Programs. In June, the Governor vetoed all funding for the Early Mental Health Initiative, for Proposition 98 savings of $15 million. In addition, the Governor vetoed $10 million in non–Proposition 98 funds that would have provided child nutrition funding for private schools and child care centers not eligible for the state’s existing child nutrition program. The Governor also vetoed $8.1 million in one–time Proposition 98 funding for support of regional activities and statewide administration of the Advancement Via Individual Determination program.

As shown in Figure 6, the 2012–13 Budget Act authorizes total spending of $2.2 billion for subsidized child care and preschool programs. This is a decrease of $185 million, or 8 percent, from the prior year. As shown in the bottom part of the figure, this decline is due to reduced state funding, as federal funding remains relatively flat. The drop in state funding consists of a $306 million reduction in non–Proposition 98 General Fund support, partially offset by a $113 million increase in Proposition 98 General Fund spending.

Figure 6

Child Care and Preschool Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12a

|

2012–13

|

Change From 2011–12

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Expenditures

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CalWORKs Child Care

|

$1,232

|

$1,023

|

$976

|

–$46

|

–5%

|

|

Non–CalWORKs Child Care

|

1,083

|

918

|

666

|

–252

|

–27

|

|

Preschool

|

397

|

368

|

481

|

113

|

31

|

|

Support programs

|

100

|

76

|

76

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$2,812

|

$2,385

|

$2,199

|

–$185

|

–8%

|

|

Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Proposition 98 General Fund

|

$1,597b

|

$368

|

$481

|

$113

|

31%

|

|

Non–Proposition 98 General Fund

|

35

|

1,077

|

771

|

–306

|

–28

|

|

Federal funds

|

1,179

|

939

|

947

|

8

|

1

|

Aligns All Funding for State Preschool Program Within Proposition 98. The budget package includes a change in the way the state accounts for subsidized preschool services. In 2011–12, the state supported approximately 100,000 part–day/part–year preschool slots using Proposition 98 funds and an additional roughly 45,000 full–day/full–year preschool slots using non–Proposition 98 funds. The 2012–13 Budget Act consolidates the state’s subsidized preschool program by funding the preschool–associated portion of full–day/full–year slots within Proposition 98. From an accounting perspective, this increases Proposition 98 funding for the State Preschool Program by $164 million and decreases funding for the General Child Care program by a commensurate amount (resulting in state General Fund savings). The accounting change has no programmatic effect. Eligible working families whose preschoolers need full–day/full–year child care can continue to receive supplementary “wraparound” services funded through the General Child Care program.

Funds Fewer Subsidized Child Care and Preschool Slots. The budget package adopted by the Legislature reduced General Fund support for child care programs by $80 million, or 8.7 percent, eliminating funding for about 10,500 slots. Child care contractors would achieve these savings through attrition and, to the degree necessary, by disenrolling currently served children from higher–income families. The Legislature applied these across–the–board reductions to the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) Stage 3, Alternative Payment, General Child Care, and migrant child care programs (exempting the CalWORKs Stage 1 and Stage 2 programs and the State Preschool Program). The Governor vetoed $50 million of associated spending in the legislative budget package. Specifically, he vetoed: (1) $20 million in non–Proposition 98 General Fund spending by deepening the AP program cut to about 18 percent (eliminating an additional 3,400 slots) and (2) $30 million in Proposition 98 spending by also applying the 8.7 percent reduction to the State Preschool Program (eliminating 12,500 slots).

Extends Family Fees to Preschool Program. As their family earnings increase, the state requires parents to pay an increasing share of their subsidized child care costs. (The maximum family contribution is capped at 10 percent of the family’s total income.) For example, based on 2012–13 rates, a family of three earning $2,500 per month pays about $45 per month towards the cost of part–day care. The budget package extends this fee policy to families participating in the part–day/part–year State Preschool Program, which previously had been available free of charge. Revenue from charging these fees—estimated at $3.4 million—will support approximately 900 additional preschool slots. (The legislative budget package had assumed $20 million in additional family fee revenue, but the Governor’s veto reduces the number of preschool slots. Given enrollment priorities, the reduction in slots will affect the relatively higher–income families who pay fees, which in turn results in less fee revenue assumed in the final enacted budget.)

The enacted budget provides a total of $9.5 billion in General Fund support for higher education in 2012–13 (see Figure 7). The net General Fund reduction of $554 million from the prior year results largely from (1) using federal funds to replace about $800 million in General Fund support for Cal Grants, and (2) modest General Fund augmentations for the three public higher education segments. On a programmatic basis, support for public colleges and universities is relatively flat, while Cal Grant awards are reduced primarily at private institutions. Total General Fund support for higher education has declined since its peak in 2007–08, though much of that General Fund reduction has been backfilled with substantial tuition and fee increases at the public colleges and universities as well as with federal and other funds in the state Cal Grant programs. Below, we discuss the major components of the 2012–13 budget package for the University of California (UC), California State University (CSU), CCC, and California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). (In the nearby box, we discuss the Governor’s proposed “long–term funding plan” for higher education which the Legislature ultimately rejected.)

Figure 7

Higher Education Funding

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

Change From 2011–12

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$2,910.7

|

$2,273.6

|

$2,378.1

|

$104.5

|

5%

|

|

California State University

|

2,577.6

|

2,002.7

|

2,010.7a

|

8.0

|

0

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

4,060.8

|

3,366.9

|

3,531.6b

|

164.7

|

5

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

8.4

|

6.9

|

7.8

|

0.9

|

13

|

|

California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

1.9

|

0.9

|

—

|

–0.9

|

—

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

1,251.0

|

1,486.2

|

678.5

|

–807.6c

|

–54

|

|

General obligation bond debt service

|

809.9

|

724.3

|

700.5

|

–23.8

|

–3

|

|

Lease–revenue bond debt serviced

|

(335.0)

|

(330.9)

|

(346.7)

|

(15.7)

|

(5)

|

|

Totals

|

$11,620.3

|

$9,861.5

|

$9,307.3

|

–$554.2

|

–6%

|

No Higher Education “Compact”

The Governor’s January budget proposed a new “long–term funding plan” for higher education. In general, the plan was similar to multiyear funding “compacts” developed under prior administrations. Those earlier compacts were uncodified agreements whereby the Governor promised to propose specified funding increases for the universities in exchange for the universities’ commitments to specified enrollment and tuition levels, as well as other targets. Unlike the prior compacts, however, the Governor’s plan would have (1) significantly reduced budgetary controls for all the segments and (2) eliminated the budgetary distinction between support and facility funding for the universities. The Legislature rejected the Governor’s proposed plan.

UC and CSU

Overall UC Funding. The 2012–13 budget provides UC with $2.4 billion in General Fund support—an increase of $105 million (5 percent) from the prior year. Of this increase, $89 million is for UC’s pension costs (as discussed below). The remainder is for increased lease–revenue bond payments for projects approved by the Legislature in prior budgets ($10 million) and increased health care costs for UC retirees ($5.2 million). In addition, the university currently expects to receive roughly $2.4 billion in 2012–13 from student tuition payments. Given that UC has not approved any tuition increase for 2012–13, this amount is roughly the same as the university collected in the prior year.

Overall CSU Funding. For CSU, the budget provides $2 billion in General Fund support—virtually the same as the prior year. (The CSU budget also includes $240 million for health care costs for retired annuitants. These costs previously were funded in a statewide item outside of CSU’s budget.) In addition to its General Fund support, CSU currently expects to receive roughly $1.7 billion in 2012–13 from student tuition payments. This includes $132 million from a 9.1 percent tuition increase that the Trustees approved for 2012–13. As described below, the budget includes financial incentives for the university to rescind that tuition increase.

Provides Augmentation for UC Pension Costs. The $89 million augmentation for UC’s pension costs represents the first time in more than two decades that the state has provided funding for this purpose. (For most of that time, neither UC nor its employees were contributing to UC’s pension plan because investment returns more than covered those costs. The university and its employees resumed contributions in 2010, which was a few years after the plan ceased to be fully funded.) Provisional language in the budget restricts the funding to increased pension costs for university employees whose salaries are supported by General Fund or student tuition. In addition, this language states that the amount of future augmentations for this purpose, if any, shall be determined by the Legislature. (In addition, the budget provides about $1 million to Hastings College of the Law for retirement costs.)

Eliminates Most UC and CSU Earmarks. Typically, the annual budget act includes a number of restrictions on UC’s and CSU’s General Fund appropriations that reflect legislative priorities. For example, the 2011–12 budget earmarked $9.2 million for AIDS research at UC. The Legislature rejected the Governor’s January proposal to eliminate these earmarks—restoring them in provisional language. The Governor, however, vetoed the earmarks, with three exceptions—the $89 million for UC’s pension costs, $52 million for UC student financial aid, and $34 million for CSU financial aid. Because the earmarks were all in provisional language (rather than in itemized budget schedules), the Governor’s vetoes did not reduce the total amount of funding available to the universities. Rather, his vetoes allow the universities to use this once restricted funding for any purpose that they wish.

Sets UC and CSU Enrollment Expectations. The budget act typically specifies the number of full–time equivalent (FTE) state–supported resident students that the state expects the universities to enroll. As passed by the Legislature, the 2012–13 budget specifies corresponding enrollment targets of 209,977 state–supported students at UC and 331,716 students at CSU.

Capital Outlay. The budget includes new appropriations from general bond funding for two UC projects—$7.7 million for the construction phase of an infrastructure improvement project at the Santa Cruz campus and $4.8 million for preliminary plans and working drawings for a new classroom and academic office building at the Merced campus. It also includes a total $16.5 million in general obligation bond funding for three renovation projects and five seismic upgrade projects at CSU.

Provides Fiscal Incentive to Freeze Tuition Levels. For UC and CSU, the budget package appropriates $125 million each in General Fund support for the 2013–14 fiscal year under specified conditions. Specifically, the universities would receive these augmentations only if (1) they maintain student tuition for the 2012–13 academic year at the same level as the 2011–12 academic year and (2) the Proposition 30 tax increases take effect. At the time this report was prepared, the UC Regents had not taken any action to increase student tuition for 2012–13. However, the CSU Trustees had already approved a 9.1 percent tuition increase for fall 2012. At the time this report was prepared, the Trustees had not made any change to that action.

Potential Trigger Reductions. As discussed elsewhere in this report, the enacted budget includes various midyear cuts that would be triggered in the event that the Proposition 30 tax increase measures do not take effect. Among those trigger cuts, UC and CSU each would receive an unallocated $250 million reduction.

CCC

Total Proposition 98 Funding. As with K–12 education, community colleges’ local property tax revenue and most of their General Fund support counts toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Figure 2 (in the “Proposition 98” section of this chapter) shows that the 2012–13 budget provides CCC with $5.8 billion in Proposition 98 support. This reflects an increase of $568 million (11 percent) over the revised 2011–12 level. The 2012–13 budget assumes that CCC’s Proposition 98 funding will include $451 million in revenues (local property taxes as well as cash assets) resulting from the dissolution of RDAs. The budget package includes language that provides a General Fund backfill for community colleges to the extent that these revenues do not materialize in 2012–13.

Slight Programmatic Increase. Much of CCC’s increased funding pays for costs incurred in the prior year or reflects funding swaps and technical adjustments that do not have a programmatic effect on community colleges. Most notably, the 2012–13 budget package provides a $129 million increase to restore base funding following a prior–year deferral and $160 million to retire other existing CCC deferrals (reducing the state’s late payments to community colleges to $801 million). From a programmatic perspective, CCC funding increases by $88 million. Of this amount, $50 million is for 0.9 percent enrollment growth, $24 million is an increase associated with creating a CCC mandate block grant (bringing total block grant funding to $33 million), and $14 million is a workload adjustment for CCC financial aid administration.

Mandate Block Grant Adopted. As discussed in the “Proposition 98” chapter of this report, the budget package includes a new mandate block grant for K–12 education and CCC. The 2012–13 budget provides community colleges with $33 million for the block grant. Community college districts that choose to participate in the block grant will receive $28 per FTE student in 2012–13. Alternatively, districts can seek reimbursement for mandated activities through the regular claiming process. (The enacted budget appropriates a total of $17,000 for community college districts that opt to submit claims for reimbursement.)

Community College Fees. Effective July 2012, enrollment fees for in–state residents increased to $46 per unit (from $36 per unit) as part of the 2011–12 budget package’s trigger cuts. The 2012–13 budget package does not include any additional changes to this fee level for resident students. It does, however, increase fees for nonresident students from neighboring states that have a reciprocity agreement with California (currently, Arizona and Oregon). Specifically, in 2012–13, fees for these nonresident students will increase from $42 per unit to two times the amount of in–state enrollment fees (that is, $92 per unit). Beginning in 2013–14, these fees will be pegged to three times the prevailing in–state fee. (Nonresident students from other states will continue to pay higher fees that reflect the full cost of instruction.)

Potential Trigger Reductions. If Proposition 30’s tax increases do not go into effect, two of CCC’s budget act augmentations would be rescinded: (1) $160 million to buy down deferrals and (2) $50 million for enrollment growth. In addition, community colleges would experience a base programmatic cut of $339 million. Under such a scenario, the budget includes a provision that makes a proportionate reduction (about 6 percent) to the number of FTE students community colleges would be required to serve in 2012–13. Statutory language expresses the Legislature’s intent that any resulting workload reductions be limited as much as possible to “courses and programs outside of those needed by students to achieve their basic skills, workforce training, or transfer goals.”

Cal Grants

The 2012–13 budget provides $1.5 billion for Cal Grants, including $645 million in General Fund support, $804 million in federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds, and $85 million from the Student Loan Operating Fund (SLOF). Spending is virtually flat from the prior year. Spending changes include a combination of cost increases offset by programmatic reductions. The 2012–13 Budget Act and related legislation make several programmatic changes to Cal Grants. The budget package also relies heavily on fund swaps and phases out loan assumption programs. Each of these changes is discussed in more detail below.

Tightens Eligibility Requirements for Schools. The 2011–12 budget package established a new rule that affected which postsecondary institutions may participate in the Cal Grant program. The new rule specified that institutions with student default rates on federal loans of greater than 24.6 percent no longer would be able to participate. The 2012–13 budget package tightens this default rate limit and adds a graduation rate requirement. Specifically, a school must have a three–year cohort default rate below 15.5 percent and a graduation rate above 30 percent to remain eligible for Cal Grants. (The budget package also clarifies that an institution that becomes ineligible due to its default or graduation rates may regain eligibility for an academic year for which it satisfies the requirements.)

The package contains two exceptions to these requirements. First, the restrictions do not apply to institutions with fewer than 40 percent of undergraduates borrowing federal student loans. Second, institutions with a default rate below 10 percent and a graduation rate above 20 percent are exempt from the graduation requirement until 2016–17. Students already attending an institution that becomes ineligible as a result of the new rules would be allowed to receive renewal awards (in 2012–13 only), but the amount of those awards is reduced by 20 percent. The budget assumes these actions will result in $55 million in Cal Grant savings.

Veto Results in Reduced Award Amounts in 2012–13. Using his veto authority, the Governor reduced new and renewal Cal Grant awards by 5 percent from their 2011–12 levels—achieving $23 million in associated savings. The reduction applies to the maximum Cal Grant A and B tuition and fee award for students at nonpublic institutions, the Cal Grant B access award (a stipend for books and supplies), the Cal Grant C tuition and fee award, and the Cal Grant C book and supply award (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

Lower Maximum Amounts for Many New Cal Grant Awardsa

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Maximum New Cal Grant A and B Tuition Awardsb

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nonprofit and WASC–accredited for–profit institutions

|

$9,708

|

$9,223

|

$9,084

|

$8,056

|

|

All other for–profit institutions

|

9,708

|

9,223

|

4,000

|

4,000

|

|

Other Maximum Awards

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cal Grant B access awards

|

1,551

|

1,473

|

Amounts to bespecified in annual budget act

|

|

Cal Grant C tuition and fee awards

|

2,592

|

2,462

|

|

Cal Grant C book and supply awards

|

576

|

547

|

Trailer Bill Reduces Some Award Amounts in 2013–14 and 2014–15. The education trailer bill reduces award amounts for some students in 2013–14 and 2014–15 (as shown in Figure 8). Specifically, in 2013–14, tuition and fee awards are reduced by an additional 2 percent for new recipients at nonprofit colleges and universities as well as for–profit institutions accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC). Awards are reduced by an additional 57 percent for new recipients at all other for–profit colleges. In 2014–15, new awards at nonprofit and WASC–accredited for–profit institutions are reduced an additional 11 percent. Renewal awards in future years will be based on the award amount in place when the recipient first received a Cal Grant.

Corrects Unintended Consequence of Previous Legislation. Last year the Legislature adopted several changes to Cal Grant eligibility, including a requirement that students meet income, asset, and financial need thresholds to renew awards. Previously, students had to meet these financial criteria only for initial awards. Under the new policy, about 5,000 students who were initially eligible for both Cal Grant A and Cal Grant B awards received a Cal Grant B award and then became ineligible for renewal under Cal Grant B eligibility thresholds, which are tighter than those for Cal Grant A. These recipients were unable to renew their awards, even though they continued to meet the eligibility criteria for Cal Grant A. The budget clarifies that students in this situation may receive Cal Grant A renewal awards. This action increased Cal Grant expenditures by $28 million in 2011–12 and $27 million in 2012–13.

Codifies Transfer Entitlement Requirement. Under current practice, a student must attend a baccalaureate institution in the year immediately after attending a community college to qualify for a transfer entitlement award. A recent CSAC decision would have removed this restriction, potentially adding 9,000 students and $70 million in new Cal Grant awards. The budget package codifies the attendance requirement in legislation but provides an additional year of eligibility for students who attended community college in 2011–12.

New and Expanded Fund Shifts Offset General Fund Costs. The budget includes two fund shifts. The SLOF, which receives proceeds of the federal guaranteed student loan program, will provide $85 million toward Cal Grant costs, an increase of $22 million in SLOF support over 2011–12. The TANF funds redirected from the state’s CalWORKs program will provide $804 million for Cal Grants. Although previous budgets have proposed similar actions, this is the first time the Legislature has adopted a redirection of TANF funds to Cal Grants. Each fund shift offsets an equal amount of General Fund support, with no programmatic impact on financial aid programs.

Hiatus in Loan Assumption Programs. The Governor’s January budget proposed phasing out loan assumption programs. Under these programs, the state agrees to make loan payments on behalf of eligible students who borrow federal loans and work in specified occupations and settings—such as teachers in low–performing schools and nurses in state prisons—after graduation. The proposed phase–out involved issuing no new agreements and continuing payments for students who have already received at least one payment and who complete additional years of qualifying employment. (Students can receive payments for a total of three to four years as they complete years of qualifying employment.) Students with existing agreements who had not yet received initial payments would have received no benefits under the Governor’s proposal, even if they had completed a portion of their qualifying employment. The Legislature rejected this proposal and restored budget language authorizing 7,500 new agreements in 2012–13. The Governor deleted authority for new warrants using his veto power. While this action has no 2012–13 impact, it will reduce expenditures in later years. Under the terms of the final budget, students with existing agreements who continue to meet their employment obligations will receive loan assumption payments in accordance with their agreements.

In 2011, the Legislature made a number of changes to realign certain state program responsibilities and revenues to local governments (primarily counties). In total, the 2011 realignment shifted about $6 billion in state sales tax revenues, vehicle license fee revenues, and (on a one–time basis) Mental Health Services Fund revenues to local governments to fund various criminal justice, mental health, and social service programs. (For more detail on the 2011 realignment, see our August 2011 publication, 2011 Realignment: Addressing Issues to Promote Its Long–Term Success.) As part of the 2012–13 budget package, the Legislature approved a number of changes to the funding structure and programs in the 2011 realignment. The most significant of these changes are described below.

Ongoing Funding Structure

As part of the 2012–13 budget process, the Legislature approved an ongoing funding structure for the programs realigned in 2011. The structure establishes several state accounts and subaccounts within the Local Revenue Fund 2011 into which the realignment funding is deposited for the various realigned programs. The realignment legislation provides formulas for how the funding is to be allocated among these accounts and subaccounts. The legislation specifies, for example, that the first allocation of sales tax revenue each month goes to fund 1991 mental health realignment responsibilities that were incorporated in the 2011 realignment. The legislation also specifies how much of any future increases in realignment revenues are distributed among growth accounts associated with each account and subaccount. The funding structure also provides some formulas and general direction for how the funding in each of the accounts and subaccounts is to be allocated among local governments.

The realignment structure also establishes some limits on how local governments can use their realignment funding. For example, the legislation creates a strict “firewall” between the criminal justice programs and the health and human services programs in realignment so that funding provided for criminal justice programs cannot be used for health and human services programs and vice versa. In addition, the structure provides counties with some flexibility to shift funding among the health and human services programs. It does so primarily in two ways. First, the new account structure groups all realigned health and human services programs into one account—the Support Services Account—which contains two subaccounts, the Protective Services Subaccount (includes funding for various child welfare and adult protective services programs) and the Behavioral Health Subaccount (includes funding for several mental health and substance abuse treatment programs). In so doing, the account structure allows counties flexibility to shift funding among different programs within the same subaccount to meet their local needs and priorities. Second, the new realignment legislation allows each county to transfer a limited amount of funding—up to 10 percent of the smaller subaccount—between these two subaccounts. The legislation does not provide any similar flexibility for the law enforcement services subaccounts (including community corrections, trial court security, and various grant programs). Figure 9 shows the estimated realignment revenues in 2012–13 and how they would be allocated among the realigned programs.

Figure 9

Local Revenue Fund 2011: Realignment Revenues and Allocations

2012–13 (In Millions)

|

Revenues

|

|

|

Sales Tax

|

$5,435

|

|

Vehicle License Fee

|

455

|

|

Total Revenues

|

$5,890

|

|

Allocations

|

|

|

Law Enforcement Services

|

|

|

Community corrections

|

$901

|

|

Trial court security

|

504

|

|

Various law enforcement grants

|

490

|

|

Juvenile justice

|

107

|

|

District attorneys and public defenders

|

19

|

|

Law Enforcement Total

|

($2,020)

|

|

Support Services

|

|

|

Protective servicesa

|

$1,759

|

|

Behavioral healthb

|

983

|

|

Support Services Total

|

($2,742)

|

|

1991 Mental Health and CalWORKs

|

$1,128

|

|

Total Allocations

|

$5,890

|

Child Welfare and Adult Protective Services Programs

The 2012–13 budget continues implementation of the 2011 realignment for the Child Welfare Services, Foster Care, Adoptions, Adoption Assistance, Child Abuse Prevention, and Adult Protective Services programs (for additional detail on these programs, see our August 2011 publication on realignment). Legislation enacted as part of the 2012–13 budget package makes several policy and technical changes to the child welfare realignment programs, provides additional county flexibility, and establishes oversight and accountability provisions specific to realignment. Some of the major changes for child welfare realignment include:

- County Flexibility. The 2012–13 budget gives counties a single funding allocation for all child welfare and Adult Protective Services realignment programs, thus allowing counties to establish local funding priorities for these programs and providing counties greater funding flexibility to respond to caseload trends in these programs. As mentioned previously, budget legislation also allows counties to transfer funds between protective services and behavioral health programs, on a limited basis, to more flexibly respond to caseload growth and funding needs across health and human services realignment programs. Budget legislation also makes some child welfare program components optional to counties, subject to public notice requirements.

- Outcomes and Accountability. Budget legislation clarifies the Department of Social Services’ (DSS) oversight role in the state’s child welfare programs and clarifies continued county accountability to state and federal outcome measures under realignment. Budget legislation also clarifies the state’s authority to conduct audits of county child welfare programs, and requires DSS and the counties to develop mutually agreed–upon program performance goals when counties do not meet child welfare outcome measures. Budget legislation also requires DSS to prepare an annual report on county expenditures of child welfare realignment funds.

- Extended Foster Care. Chapter 559, Statutes of 2010 (AB 12, Bass and Beall), commonly referred to as “AB 12,” authorized extended foster care for foster youth up to age 21 on a phased–in basis. Assembly Bill 12 required a legislative appropriation to fully implement extended foster care from age 20 to 21. The 2012–13 budget continues AB 12 implementation and provides realignment funding for extended foster care. Beginning in January 2014, extended foster care will be available for foster youth up to age 21.

Mental Health Programs

Two major mental health programs previously funded, in part, through the Department of Mental Health (DMH) were realigned as part of the 2011–12 budget package. The major realigned mental health programs are Mental Health Managed Care (MHMC) and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT).

Under realignment, in 2011–12 $763 million of Proposition 63 funds was redirected in lieu of General Fund on a one–time basis to support MHMC ($184 million) and EPSDT ($579 million). (In November 2004, the state’s voters approved Proposition 63, an initiative that allocated additional state revenues generated through a surcharge on income taxpayers earning more than $1 million annually for various specified community mental health programs.) Beginning in 2012–13, MHMC and EPSDT will mainly be funded with a combination of funds from the 2011 realignment revenues and federal matching funds.

Alcohol and Drug Programs

Several programs previously funded through the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP) were realigned as part of the 2011–12 budget package. The major realigned programs are Regular and Perinatal Drug Medi–Cal, Regular and Perinatal Non–Drug Medi–Cal, and drug courts.

In 2011–12, about $184 million in funding for these programs was deposited into three separate subaccounts within the newly created Health and Human Services Account of the Local Revenue Fund 2011. In 2012–13, some of these programs will be funded mainly with a combination of realignment funds and federal matching funds, while other programs will be funded mainly by realignment funds. Under realignment, counties have some discretion to significantly increase or decrease their spending levels for some drug and alcohol programs to reflect local priorities.

Community Corrections Programs

The 2011 realignment included several changes to the state’s correctional system, most notably requiring counties to house and supervise all newly convicted felons with no current or prior convictions for serious, violent, or sex offenses. As part of the 2012–13 budget package, the Legislature approved trailer legislation related to the ongoing implementation of the realignment of adult offenders. For example, trailer legislation was enacted to make technical corrections to previously enacted realignment–related statutes. The Legislature realigned to local responsibility certain crimes—such as various weapon possession offenses—that were inadvertently excluded from realignment under prior legislation. This legislation also undid the realignment of other crimes—such as certain sex offenses—that were inadvertently included in the set of realigned crimes. In addition, previously enacted realignment legislation shifted responsibility for parole revocation hearings from the state Board of Parole Hearings to local trial courts effective July 1, 2013. To facilitate this transition, the budget package included trailer legislation intended to make future parole revocation hearing procedures in trial courts similar to the procedures already used by these courts for county probation revocation hearings. The trailer legislation also attempts to address local concerns about potential jail overcrowding that could occur under realignment by (1) expanding the ability of counties to transfer—on a contract basis—more inmates to other county jails regardless of how close the counties are to each other and (2) allowing sheriffs operating overcrowded jails to release sentenced inmates up to 30 days before the end of their jail sentence—up from five days under prior law—as long as each affected inmate already had served at least 90 percent of their sentence.

The 2012–13 spending plan provides $19.3 billion from the General Fund for health programs. This is a decrease of $767 million, or almost 4 percent, compared to the revised 2011–12 spending level, as shown in Figure 10. The net decrease reflects both increases in caseload and utilization of services and the adoption of significant health program reductions and cost–containment measures. The major program–specific changes and cost–containment measures are summarized in Figure 11 and discussed in more detail below. Absent the changes shown in the figure, total General Fund spending for health programs in 2012–13 would have been $1.6 billion higher.

Figure 10

Major Health Programs and Departments—Spending Trends

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

Change From

2011–12 to 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Medi–Cal—Local Assistance

|

$12,366

|

$15,461

|

$14,442

|

–$1,019

|

–6.6%

|

|

Department of Developmental Services

|

2,451

|

2,551

|

2,647

|

96

|

3.8

|

|

Department of State Hospitals

|

—

|

—

|

1,368

|

—

|

—

|

|

Department of Mental Health

|

1,852

|

1,351a

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Healthy Families Program—Local Assistance

|

119

|

286

|

163

|

–123

|

–42.9

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

186

|

133

|

132

|

–1

|

–0.8

|

|

Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs

|

189

|

38

|

34

|

–4

|

–10.5

|

|

Other Department of Health Care Services programs

|

32

|

76

|

176

|

100

|

131.6

|

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority

|

8

|

7

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

|

All other health programs (including state support)

|

222

|

121

|

288

|

167

|

137.5

|

|

Totals

|

$17,425

|

$20,024

|

$19,257

|

–$767b

|

–3.8%

|

Figure 11

Major Changes—State Health Programs2012–13 General Fund Effect

(In Millions)

|

Program

|

Amount

|

|

Medi–Cal—Department of Health Care Services

|

|

|

Expand demonstration project to coordinate care for seniors and persons with disabilities

|

|

|

Transition long–term supports and services from fee–for–service to managed care

|

$115

|

|

Defer payments to providers and managed care plans

|

–711

|

|

Shared savings from Medicare

|

–12

|

|

Hospital payment changes

|

–387

|

|

Nursing home payment changes

|

–88

|

|

Change payment structure for retroactive services in certain counties

|

–48

|

|

Use First 5 (Proposition 10) monies to fund Medi–Cal

|

–40

|

|

Temporarily increase rates for primary care services

|

39

|

|

Eliminate payments for certain potentially preventable hospital admissions

|

–30

|

|

Implement copays for certain prescription drugs and emergency room services

|

–20

|

|

Identify and achieve operational efficiencies

|

–10

|

|

Reduce rates for laboratory services

|

–8

|

|

Expand managed care to rural counties

|

–3

|

|

Department of Developmental Services (DDS)

|

|

|

Implement various cost–containment measures for DDS programs

|

–200

|

|

Use First 5 (Proposition 10) monies to fund services for developmentally disabled children

|

–40

|

|

Healthy Families Program (HFP)

|

|

|

Implement unallocated reduction

|

–183

|

|

Transition of HFP children to Medi–Cal (only part of the transition occurs in 2012–13)

|

–13

|

|

Department of State Hospitals

|

|

|

Governor’s veto of funding for the Adult Education program

|

–4

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

|

|

Eliminate the Public Health Laboratory Training Program

|

–2

|

|

Total

|

–$1,645

|

Realignment of Mental Health Programs. As part of the 2011–12 budget package, the Legislature made a number of changes to realign certain state program responsibilities and revenues to local governments (primarily counties). The 2012–13 budget package continues the process of realigning mental health programs and alcohol and drug programs to local governments and dedicating revenue streams to support them. For more information, see the “Realignment” section earlier in this report.

Department Eliminations, Program Shifts, and Other Transfers

As part of its 2011–12 budget proposal, the administration stated its intent to eventually eliminate DMH and DADP. Pursuant to the adopted budget plan, DMH was eliminated effective July 1, 2012, and DADP is slated for elimination at the end of the 2012–13 fiscal year. The budget plan also shifts several programs, offices, and task forces from one department to another and transfers state–level administration of some functions between departments. We discuss these major organizational changes below.

DMH Eliminated: New Department of State Hospitals (DSH) Will Administer State Hospitals. The budget plan approves the administration’s proposal to eliminate DMH and shift state–level administration of community mental health programs and other DMH functions to other departments. It also creates the DSH to administer the state hospitals, in–prison programs, and the Conditional Release Program (CONREP). The administration states that its goals for the creation of DSH are to (1) allow DSH to focus on effective patient treatment and increased worker and patient safety; (2) integrate services to provide an effective continuum of care, consistent with federal health care reform; and (3) better align program missions and functions to improve efficiency and program delivery.

Shifts State–Level Oversight for Bulk of Mental Health Programs to Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). State level oversight for the EPSDT program, MHMC, and Proposition 63 activities was largely shifted from DMH to DHCS during 2011–12. The Mental Health Oversight and Accountability Commission will also provide oversight for Proposition 63. As shown in Figure 12, the remaining DMH programs and functions were shifted to various departments including DSS, the Department of Public Health (DPH), and the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

Figure 12

Elimination of Department of Mental Health: Shift of Programs to Other Entities

(Dollars in Millions)

|

From Department of Mental Health (DMH)

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

To

|

|

Personnel Years

|

Total Fundsa

|

Personnel Years

|

Total Fundsa

|

|

Mental health, Medi–Cal, and Propositon 63 oversight

|

74.7

|

$4.2

|

146.6

|

$82.5

|

Department of Health Care Services

|

|

Licensing functions

|

—

|

—

|

10.8

|

1.1

|

Department of Social Services

|

|

Proposition 63—mental health workforce development programs

|

—

|

—

|

0.9

|

12.3

|

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development

|

|

Early Mental Health Initiative

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

California Department of Education

|

|

Proposition 63—Mental Health Services Act technical assistance and training

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

1.7

|

Mental Health Oversight Accountability Committee

|

|

Office of multicultural services

|

—

|

—

|

2.8

|

2.2

|

Department of Public Health

|

DADP Slated for Elimination July 1, 2013. State–level oversight of the Drug Medi–Cal program was shifted from DADP to DHCS effective July 1, 2012. Budget legislation transfers other administrative and programmatic functions of DADP to unspecified departments within the California Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA), effective July 1, 2013. The legislation requires that HHSA, in consultation with stakeholders and affected departments, submit a detailed plan for the reorganization of DADP’s functions to the Legislature as part of the 2013–14 Governor’s Budget. The ultimate placement of these functions will have to be determined in the 2013–14 budget package.

Children Enrolled in the Healthy Families Program (HFP) Shift to Medi–Cal. The budget plan transfers all children enrolled in HFP to Medi–Cal on a phased–in basis, beginning in January 2013. This transition is projected to occur over a 12–month period and create General Fund savings of $13.1 million in 2012–13, $58.4 million in 2013–14, and $72.9 million in 2014–15 (when the transfer of all HFP children to Medi–Cal is expected to be complete). The children enrolled in HFP will be transitioned to Medi–Cal in four phases:

- The first phase will begin January 1, 2013 and include approximately 415,000 children enrolled in HFP managed care plans that also contract with Medi–Cal.

- The second phase will begin April 1, 2013 and include approximately 249,000 children enrolled in HFP managed care plans that subcontract with a Medi–Cal managed care plan.

- The third phase will begin August 1, 2013 and include approximately 173,000 children enrolled in HFP healthcare plans that do not contract with Medi–Cal or subcontract with a Medi–Cal plan. These children will be transitioned into a Medi–Cal managed care plan.

- The fourth phase will begin no earlier than September 1, 2013 and affect approximately 43,000 children enrolled in HFP healthcare plans who live in a county where Medi–Cal managed care is not available. They will be transitioned into Medi–Cal fee–for–service, unless a Medi–Cal managed care plan becomes available.

The budget plan requires HHSA to work with the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board (MRMIB), the Department of Managed Health Care, DHCS, and stakeholders to develop a strategic plan for the transition of HFP. This plan will address several components of the transition, including ensuring stakeholder engagement in the transition, state monitoring of managed care health plans’ performance, and network adequacy standards.

Office of Health Equity (OHE) Created Within DPH. The budget plan creates OHE within DPH to consolidate several offices and other entities that focus on health disparities. The OHE will consolidate the functions and responsibilities of: (1) the Office of Women’s Health—formerly within DHCS, (2) the Office of Multicultural Services—formerly within DMH, (3) the Office of Multicultural Health—formerly within both DPH and DHCS, (4) the Health in All Policies Task Force—within DPH, and (5) the Healthy Places Team—within DPH.

Several Direct Healthcare Service Programs Will Be Transferred From DPH to DHCS. The budget plan transfers the following programs from DPH to DHCS: (1) Every Woman Counts, (2) Family Planning Access Care and Treatment, and (3) the Prostate Cancer Treatment Program. All of these programs deliver individual health care services. In part, the administration’s rationale for transferring these programs from DPH to DHCS is that they align well with DHCS’ mission to preserve and improve the health status of all Californians.

DHCS—Medi–Cal

The spending plan provides $14.4 billion from the General Fund for Medi–Cal local assistance expenditures administered by DHCS. This is a decrease of $1 billion, or 6.6 percent, in General Fund support for Medi–Cal local assistance compared to the revised prior–year spending level. Spending in 2011–12 was about $760 million greater than the amount appropriated in the 2011–12 budget. Some of the major factors that contributed to the higher–than–expected 2011–12 spending levels in the Medi–Cal Program were:

- Federal Government Denies Mandatory Copayment Proposal. The 2011–12 spending plan assumed over $500 million in savings by imposing mandatory copayments for Medi–Cal beneficiaries on physician visits ($5), dental visits ($5), prescription drugs ($3 or $5), emergency room visits ($50), and hospital inpatient visits ($100 per day). The state was unable to obtain approval from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to implement the mandatory copayments at the levels authorized in the 2011–12 budget. As discussed below, the 2012–13 spending plan assumes a lower level of savings from a revised copayment proposal pending CMS approval.

- Legal Challenges Prevent Provider Payment Reductions. The 2011–12 spending plan assumed over $600 million in savings by reducing certain Medi–Cal provider payments by up to 10 percent. Preliminary federal court injunctions prevented the state from implementing many of these reductions. The 2012–13 Medi–Cal budget assumes the state will prevail in its appeal of the court ruling and the payment reductions will be implemented beginning in October 2012.

- Adult Day Health Care (ADHC) Transition. The 2011–12 spending plan assumed General Fund savings of $170 million from eliminating ADHC as a Medi–Cal benefit. The 2011–12 spending plan also provided $85 million from the General Fund to help transition existing ADHC enrollees to other services. A lawsuit resulted in a nine–month delay in the elimination of ADHC and the creation of a new program called Community–Based Adult Services. These developments have caused the administration to revise the General Fund impact in 2011–12 from eliminating ADHC to a net cost of $2.4 million.

Differences in Medi–Cal spending between 2011–12 and 2012–13 are, in part, the result of underlying cost drivers in the program, such as changes to caseload and utilization of services. We discuss the major policy–driven spending changes that were adopted as part of the 2012–13 Medi–Cal Program budget below.

Expand Demonstration Project to Coordinate Care for Seniors and Persons With Disabilities. The budget assumes net savings of $608 million from a payment deferral to Medi–Cal providers combined with expanding from four to eight counties a previously authorized—but not yet implemented—demonstration project aimed at coordinating care for individuals who are eligible for both Medi–Cal and Medicare (“dual eligibles”). (As discussed below, it is the payment deferral that generates most of the savings in 2012–13. The demonstration project will actually result in a cost in 2012–13, although the savings in future years are expected to be significant.) Generally, the demonstration project will test the use of managed care to integrate the provision and financing of Medi–Cal and Medicare services. The eight counties selected by DHCS to participate in the demonstration project are: Los Angeles, Orange, San Mateo, San Diego, Riverside, San Bernardino, Alameda, and Santa Clara. The major components of the expanded demonstration project, also known as the “Coordinated Care Initiative,” include:

- Medi–Cal Long–Term Supports and Services (LTSS) Become Managed Care Benefits. In the demonstration counties, LTSS—including nursing home care, In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS), and the Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP)—will be managed care benefits for nearly all Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Prior to this change, LTSS were provided mainly by Medi–Cal on a fee–for–service basis.

- Dual Eligibles Are Enrolled in Managed Care for Medi–Cal and Medicare Benefits. Most dual eligibles will be enrolled in managed care plans that are responsible for providing both Medi–Cal and Medicare benefits beginning no earlier than March 2013. Dual eligibles will be mandatorily enrolled into managed care for their Medi–Cal benefits, but will have the option to opt out of the managed care plan for their Medicare benefits before the demonstration project begins. In addition, the budget assumes that dual eligibles who do not initially opt out of the managed care plan must remain in the plan for six months before having the option to disenroll.

- Budget Legislation Provides Implementation Detail. Budget–related legislation imposes a variety of requirements related to the implementation of the demonstration project, such as: (1) the details of how LTSS will operate as managed care benefits, (2) beneficiary notifications and protections, (3) the process used to determine managed care plan readiness, and (4) additional monitoring and oversight of managed care plans.

- Major Changes to IHSS Collective Bargaining. The budget package includes legislation to transition collective bargaining for IHSS provider wages and benefits from the local level to the state in the eight demonstration counties. Prior law required counties to pay about 17.5 percent of IHSS program costs. Budget–related legislation eliminates the county share of cost and creates a county maintenance of effort (MOE). This MOE is based upon county expenditures in IHSS in 2011–12 and will be adjusted annually for inflation.

Once fully implemented in 2014–15, the demonstration project is estimated to save hundreds of millions of General Fund dollars annually. Generally, the estimated ongoing savings assumes that managed care plans will coordinate the delivery of services in a way that helps beneficiaries avoid costly hospital and nursing home admissions. These savings are expected to accrue to both Medi–Cal and Medicare.

For 2012–13, the budget assumes General Fund savings of $12 million from a partial–year of shared savings from the Medicare Program—mainly by reducing hospital utilization. Estimates of shared savings from the Medicare Program are based on an assumption that the federal government will share 50 percent of any savings from implementing the proposal that would otherwise accrue to Medicare. The transition of services and beneficiaries from Medi–Cal fee–for–service to Medi–Cal managed care will require the state to initially incur an estimated $115 million in General Fund costs in 2012–13. To offset these up–front costs—and generate savings in 2012–13—the state will defer payments to providers and managed care plans. The budget assumes the payment deferral will generate $711 million in General Fund savings.

The demonstration is a joint project with the federal government and is subject to federal approval. In addition, continued state authorization for the demonstration project depends on federal approval of certain aspects of the demonstration, including the six–month stable enrollment period for Medicare benefits.

Hospital Payment Changes. The spending plan assumes combined General Fund savings of $387 million from implementing changes to Medi–Cal payments for three categories of hospitals: private hospitals, designated public hospitals, and non–designated public hospitals (NDPHs).

- Change Payment Methodology for NDPHs. The spending plan assumes $94 million in General Fund savings by requiring NDPHs to use “certified public expenditures” to draw down federal matching payments. The NDPHs will no longer receive reimbursement from the General Fund.

- Reduce Private Hospital Payments. Under the spending plan, $150 million in hospital fee revenues that currently fund managed care payments to private hospitals will be redirected for General Fund savings.

- Split Unspent Federal Funding With Designated Public Hospitals. The spending plan assumes $100 million, or 50 percent, of funds reallocated to an uncompensated care pool for designated public hospitals will be retained for one–time General Fund savings.

- Redirect Unpaid Hospital Stabilization Funding. Under the spending plan, $43 million previously set aside as stabilization funding for NDPHs and certain private hospitals will be redirected to the General Fund for one–time savings.

Nursing Home Payment Changes. The spending plan assumes $88 million in General Fund savings from making adjustments to Medi–Cal nursing home payments, including: (1) rescinding an increase in rates to nursing homes, (2) redirecting funds associated with limiting nursing homes’ costs for professional liability insurance, and (3) deferring one payment to nursing homes until 2013–14.

Change Payment Structure for Retroactive Services in County Organized Health Systems (COHS). The budget assumes $48 million in one–time General Fund savings by changing the payment structure for retroactive services provided to beneficiaries in COHS managed care plans. Previously, COHS were required to pay for the medical services provided to beneficiaries up to 90 days prior to enrollment, also known as a retroactive coverage period. The costs for these services were included in COHS capitation payments. The new payment structure requires COHS to pay for services that a beneficiary receives only while enrolled in the plan; the services received during the retroactive coverage period will be paid by Medi–Cal fee–for–service. This makes the treatment of retroactive coverage in COHS consistent with the payment structure used in other managed care models. The change will lower costs in the budget year by shifting payments for retroactive services received in 2012–13 from an up–front capitation payment to a series of fee–for–service payments—some of which will not be made until 2013–14.

Use First 5 Monies to Fund Medi–Cal. The budget assumes $40 million in Proposition 10 funds from the California First 5 Commission will be used in lieu of General Fund to fund Medi–Cal services for children.

Temporarily Increase Payments for Primary Care Services. The budget assumes $39 million in General Fund costs from increasing payments for primary care services as required by the federal Affordable Care Act (ACA). Under the ACA, Medicaid is required to increase rates for primary care services to an amount equivalent to Medicare for calendar years 2013 and 2014. During this period, the federal government will pay 100 percent of the cost of the rate increase above the rates in effect on July 1, 2009. Since the state enacted a 9 percent payment reduction for primary care services in 2011, it must pay for the state share of the incremental difference between existing Medi–Cal rates and the rates that were in effect on July 1, 2009. The increased rates for primary care services are scheduled to sunset at the end of 2014.

Eliminate Payments for Certain Potentially Preventable Hospital Admissions. The budget assumes $30 million in General Fund savings from eliminating payments to managed care plans for certain potentially preventable hospital admissions. Capitation rates paid to managed care plans will be adjusted downward based on the number of potentially preventable admissions.

Implement Copays for Certain Prescription Drugs and Emergency Room Services. The budget assumes $20 million in General Fund savings from imposing mandatory copayments for certain prescription drugs and nonemergency use of emergency rooms. Only beneficiaries in managed care would be subject to the copayments. Additional details about how the copayments will be implemented are still being developed, but generally enrollees would be required to pay $15 if they receive nonemergency services from an emergency room and $3.10 for non–preferred drugs. As mentioned above, implementation of these copayments requires federal approval.

Identify and Achieve Operational Efficiencies. The budget assumes $10 million in General Fund savings from DHCS achieving “operational efficiencies.” At the time of this report, the source of these operational efficiencies has not been determined.

Reduce Rates for Laboratory Services. The budget assumes $8 million in General Fund savings from reducing rates for laboratory services. Upon federal approval, the department will implement a new payment methodology that is expected to reduce payments for laboratory services. The state will reduce laboratory payments by 10 percent until federal approval for the new rate methodology is obtained.

Expand Managed Care to Rural Counties. The budget assumes $3 million in net General Fund savings associated with authorizing the expansion of Medi–Cal managed care into the 28 counties where managed care does not currently exist—generally rural counties. Mandatory enrollment into managed care plans is expected to begin in June 2013. Certain beneficiaries, such as dual eligibles, will be exempt from the mandatory enrollment. This proposal is estimated to generate savings in future years, but the transition from fee–for–service to managed care will require the state to initially incur some costs. The budget plan offsets these initial costs and generates General Fund savings by deferring payments to managed care plans.

Department of Developmental Services (DDS)