Executive Summary

This report provides an overview and assessment of the state's fiscal oversight system for school districts. The primary goal of this system is to ensure that school districts can meet their fiscal obligations and continue educating students. In recent years, the system has received considerable attention as the economic downturn has presented school districts with significant fiscal challenges.

System Consists of Monitoring, Support, and Intervention. The fiscal oversight system established by the state in 1991 makes County Offices of Education (COEs) responsible for the fiscal oversight of all school districts residing in their county and requires them to review a school district's financial condition at various points throughout the year. If a school district appears to be in fiscal distress, COEs, and in some instances the state, are granted various tools designed to help the district return to fiscal health.

Fiscal Distress Often Linked to Unsustainable Local Bargaining Agreements and Declining Enrollment. School districts with several consecutive years of operating deficits tend to be the ones most likely to be experiencing fiscal distress. This is particularly the case when districts run deficits during good economic times, as these districts will have a smaller cushion to deal with unanticipated cost increases or funding reductions during an economic downturn. Prolonged deficit spending often is linked with unsustainable local bargaining agreements. Given employee costs are the largest component of a district's budget, bargaining agreements that increase district costs at a faster rate than school district funding are particularly problematic. School districts with declining enrollment also are more likely to have fiscal problems, since the district's funding typically will decrease at a faster rate than its costs and require reductions even during good economic times.

Fiscal Oversight Process Begins With COE Review of Locally Adopted District Budget . . . To provide a consistent framework for assessing fiscal health, COEs use a state–established set of criteria and standards. The first point of review in the school year begins when the COE reviews the school district's adopted budget. The COE determines whether the budget allows the school district to meet its financial obligations during the fiscal year. If the COE disapproves the school district's budget, the school district must make modifications and resubmit the budget for approval. Disapproved budgets are a rare occurrence (on average only three budgets are disapproved per year), in part because school districts typically understand what is required to receive budget approval.

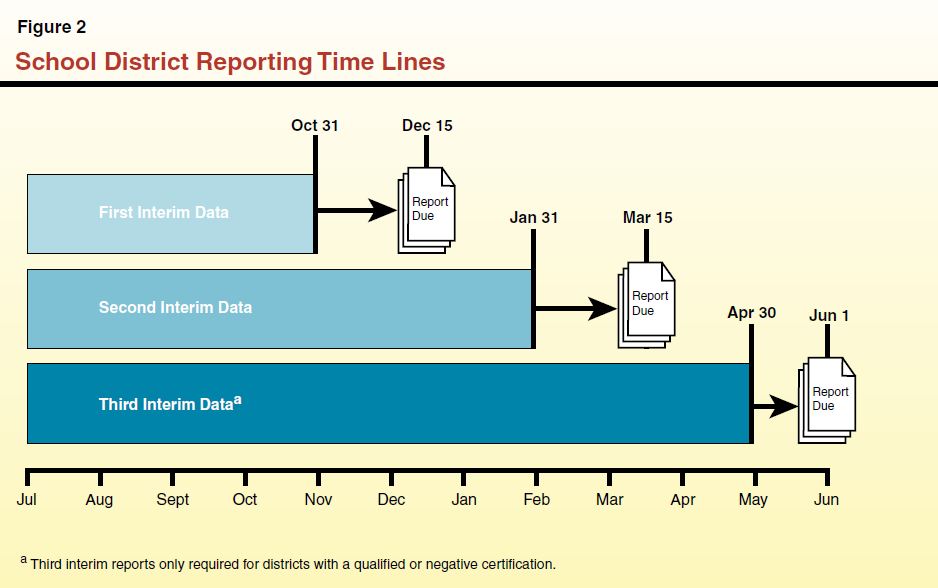

. . . Continues as Districts Submit Interim Budget Reports at Subsequent Points in Fiscal Year. The COEs also must review the financial health of school districts at two points during the school year using updated revenue and expenditure estimates. These reviews are known as "first interim" and "second interim" reports. After reviewing a district's report, the COE certifies whether the school district is at risk of failing to meet its obligations for the current year or two subsequent fiscal years. A district in good fiscal condition receives a positive certification. By comparison, a district that may be unable to meet its obligations in the current or either of the two subsequent fiscal years receives a qualified certification. A district that will be unable to meet its obligations in the current or subsequent fiscal year receives a negative certification.

At Signs of Distress, COEs Authorized to Provide Support. When a school district is certified as qualified or negative, COEs may intervene in certain ways, including assigning a fiscal expert and requiring an update of the district's cash flow and expenditure estimates. In addition, COEs must review any new collective bargaining agreements and approve the issuance of certain debt. School districts with these certifications also are required to submit a "third interim" report. If the above interventions do not improve the district's fiscal condition, COEs can impose more intense interventions, including staying and rescinding actions of a school district's local governing board.

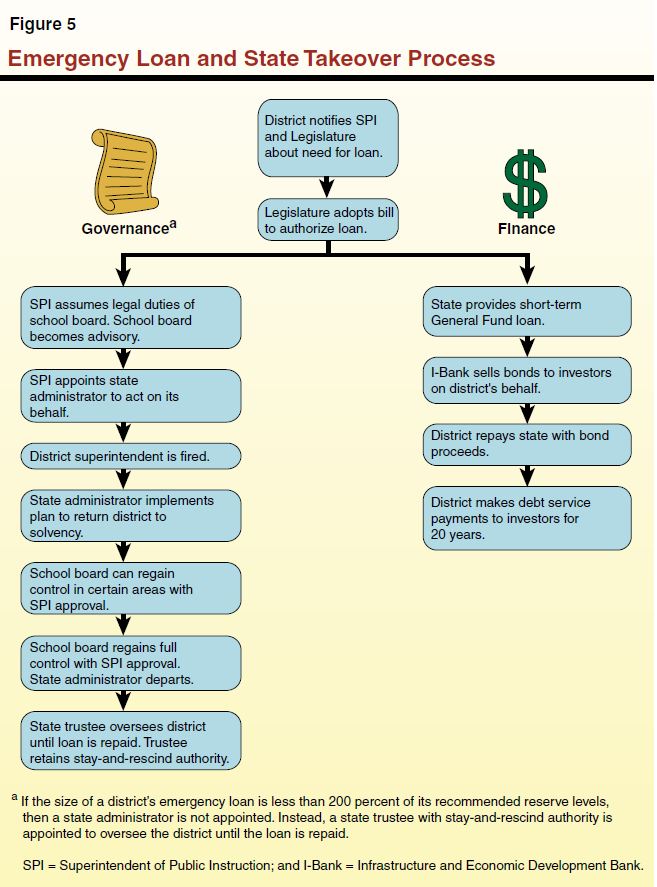

If District Cannot Meet Obligations, State Provides Emergency Loan and Takes Administrative Control. When a school district is unable to meet its financial obligations, the state provides it with an emergency General Fund loan. The school district then works with the state's Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank to issue bonds to repay the initial state loan. The district is responsible for paying the debt service and issuance costs of the loan as well as the salaries of various employees hired to provide administrative assistance to the district. From a governance perspective, the state Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI) assumes all of the duties and powers of the local board and appoints a state administrator to act on his or her behalf. The primary goal of the state administrator is to restore the fiscal solvency of the school district as soon as possible. When the SPI and state administrator determine that the district meets certain performance standards and is likely to comply with its recovery plan, the local governing board regains control of the district and the state administrator departs. Until the loan is repaid in full, a state trustee with stay and rescind powers is assigned to oversee the district.

System of Oversight and Intervention Generally Has Been Effective. Over the last two decades, the state's fiscal oversight system has reduced the number of school districts requiring state assistance and has provided oversight and support while still primarily maintaining local authority. During the more than 20 years the new system has been in effect, eight districts have received emergency state loans. By comparison, 26 districts required such loans in the 12 years prior to the new system. Furthermore, to this point, no school district has required an emergency loan as a result of the recent recession and associated budget reductions. Additionally, while the number of districts with qualified and negative budget certifications has increased in recent years, the state has not seen a corresponding increase in the number of emergency loans required. This suggests the system's structure of support and intervention is serving a critical early warning function—allowing districts to get the help they need while fiscal problems tend to be smaller and more manageable.

Recommend Preserving System Moving Forward. Despite the system's effectiveness, state actions over the last three budget cycles temporarily have reduced the ability of COEs to identify districts on the road toward fiscal distress. Most notably, the state adopted legislation that prevented COEs from disapproving 2011–12 budgets if districts appeared unable to meet their financial obligations for the following two fiscal years. We recommend the state avoid additional actions that would diminish its ability to assess school district fiscal health, provide support for fiscally unhealthy school districts, and prevent the need for emergency loans. Although proper fiscal oversight is important at any time, it is particularly important in years during and following an economic recession, when districts are more likely to experience fiscal distress.

Introduction

In 1991, the state established a comprehensive system for monitoring the fiscal condition of school districts. Under this system, COEs review their school districts' fiscal conditions shortly after districts adopt their budgets and then at a few subsequent points in the fiscal year. School districts that show signs of fiscal distress receive assistance, with the type and amount of assistance depending on the gravity of a district's fiscal condition. In the most serious case—when a district no longer appears able to meet its financial obligations—the state provides it with an emergency loan and assumes administrative control until the district has demonstrated clearly that it is solidly on the road to fiscal recovery.

During the two decades this system has been in place, school districts have faced numerous fiscal challenges. Particularly through the economic downturns, the system has proven to be generally effective at identifying districts experiencing fiscal distress and providing them targeted support. Despite the relatively longstanding success of the system in helping to maintain good school district fiscal health, the state recently has taken certain actions that have temporarily reduced the system's effectiveness. These recent actions generally have reduced the ability of COEs to identify fiscal problems looming on the horizon for districts. Especially in difficult, uncertain budget times, a system of monitoring and supporting school district fiscal health is paramount. As the state considers future actions, we recommend that it remain focused on preserving the system.

Below, we identify the common problems that characterize fiscally unhealthy districts. We then summarize the oversight process for evaluating school district fiscal health. Next, we describe the first– and second–level interventions designed to assist fiscally unhealthy school districts as well as describe the emergency loan process for districts that are unable to meet their financial obligations. Finally, we provide our assessment of the existing system.

Signs of Fiscal Distress

A number of common problems tend to be found in fiscally unhealthy districts. The Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT)—the state agency that provides fiscal advice, management assistance, and other training to school districts—identified 15 conditions that most frequently indicate district fiscal distress. These conditions are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Fifteen Key Predictors of School District Fiscal Distress

|

Administrative Issues

|

|

|

- Lack of communication with educational community

|

- Lack of interagency cooperation

|

- Failure to recognize ongoing budget problems

|

- Disconnect between personnel data and payroll

|

- Limited access to timely personnel, payroll, and budget control data and reports

|

- Lack of routine categorical program monitoring

|

|

Financial Issues

|

- Unsustainable collective bargaining agreements

|

- Compensation increases in excess of state funding increases

|

- Failure to maintain healthy reserves

|

- Flawed multiyear projections

|

- Flawed average daily attendance projections

|

- Inaccurate revenue and expenditure estimates

|

- Poor cash flow analysis and reconciliation

|

- Categorical program increases in excess of categorical funding increases

|

Fiscal Distress Often Linked With Multiple Years of Deficit Spending. School districts with several consecutive years of operating deficits likely have many of the indicators of fiscal distress listed in Figure 1 and tend to be most at risk for failing to meet their financial obligations in the near future. This is particularly true of school districts that run operating deficits during good economic times. These districts will have a smaller cushion to deal with unanticipated cost increases or reductions in funding during an economic downturn.

Deficit Spending Commonly Linked With Unsustainable Local Bargaining Agreements and Declining Enrollment. Since employee salary and benefit costs typically represent about 85 percent of school district expenditures, the terms of a school district's collective bargaining agreements have a significant effect on its fiscal health. Local bargaining agreements that increase district costs at a faster rate than school district funding are particularly problematic, as the district will be more likely to run operating deficits during these times. School districts with declining enrollment also are more likely to have fiscal problems, since their revenues tend to decline at a faster rate than their costs. Because of this fiscal pressure, declining enrollment districts must be proactive in reducing costs during good fiscal times when other districts in the state are providing cost–of–living increases to employees and expanding the size of their programs. School districts that do not make sufficient reductions to address the decline in funding can experience significant fiscal distress. Of the five school districts that have received an emergency state loan since 2000, four had experienced flat or declining enrollment in the years prior to receiving state intervention.

More Recently, Payment Deferrals and Budget Reductions Contributing to Fiscal Distress. Over the past several years, school districts have faced increased fiscal pressure as a result of funding reductions implemented to solve the state's budget problem. Since 2007–08, the year prior to the economic downturn, state programmatic per–pupil funding for school districts has decreased by 8 percent. The state also has relied significantly on payment deferrals as a budget solution over the past several years, with school districts currently receiving $9.4 billion (roughly 20 percent of Proposition 98 funding) in late state payments (that is, receiving cash in 2012–13 for costs incurred in 2011–12). To remain in good fiscal health as a result of these additional challenges, school districts have had to make significant adjustments to their budgets, including reducing their educational programs and borrowing to meet their financial commitments.

Fiscal Oversight Process

Under the state's fiscal oversight process, a school district's COE is responsible for monitoring its fiscal health at specific points during the year. At the beginning of the fiscal year, the COE must review and approve the school district's locally adopted budget. The district also must submit up–to–date multiyear projections for the COE to review at two subsequent points during the year. (A third interim report also is required for school districts that show signs of fiscal distress.) In addition to these formal points of review, COEs seek to remain in constant contact with school district superintendents, administrators, and business officers. In our conversations with COE officials throughout the state, we found that virtually all have monthly meetings with school district staff to remain informed of each district's fiscal condition. We discuss the details of the formal oversight process below.

Criteria and Standards for Review

To provide a consistent framework, COEs must use a consistent set of criteria and standards established by the state to assess school districts' fiscal condition. These criteria and standards are used both to review school districts' adopted budgets and their interim budget reports. The specific criteria and standards used vary depending on the specific point of review. Each review, however, focuses on the following major criteria:

- Fund and cash balances.

- Reserve levels.

- Operating deficits.

- Accuracy of attendance and enrollment estimates.

- Accuracy of revenue limit funding estimates.

- Salary and benefit costs.

- Facility maintenance costs.

Each criterion has a specific standard that is used for evaluation of a school district's financial condition. School districts, for example, are expected to have reserves of at least 1 percent to 5 percent depending on the size of the district (smaller districts having higher reserve requirements).

Budget Adoption

In accordance with state law, the local governing board of a school district must adopt a budget in a public hearing by July 1 every year. The school district's budget must be reviewed by the COE by August 15. Though the main objective of the COE is to determine whether the budget allows the school district to meet its financial obligations during the coming fiscal year, the COE also examines whether the district's budget plan would enable it to satisfy its financial commitments in future years. The COE also must determine whether the district complies with the existing criteria and standards. The district is required to submit to the COE any studies, reports, evaluations, or audits that show evidence the school district is under fiscal distress or exhibits at least 3 of the 15 indicators of fiscal distress listed in Figure 1. After reviewing the budget, the COE takes one of the following actions:

- Approves Budget. The COE approves the district's budget plan. No further action is needed.

- Conditionally Approves Budget. The COE approves the budget plan but has concerns about the district's ability to meet its financial obligations. The COE must provide a rationale for its conditional approval and recommend revisions the district can take to improve its budget situation. The COE also can assign a fiscal advisor to help the school district make revisions to the budget plan. The district, however, is not required to take specific action to address the concerns of the COE or fiscal advisor.

- Disapproves Budget. The COE can disapprove a district's budget if it determines the district cannot meet its financial obligations under the adopted plan. In response to a disapproved budget, the district must hold a hearing and publicly release the COE's recommended changes. The district also must make modifications and resubmit the budget to the COE for review. If the COE disapproves the budget a second time, a Budget Review Committee can be established to resolve the issue. (The committee consists of three members who are chosen by the school district from a list of candidates provided by the SPI.) The committee reviews the COE's concerns and determines whether they merit disapproval of the district's budget. If the committee rules in favor of the district, the school district can implement its budget plan without modifications. If the committee rules in favor of the COE, the district must submit modifications to the SPI for approval. If the SPI rejects the district's revised budget plan, the COE can implement a budget plan for the district.

Budget Review Provides Feedback for All Districts. Even when the COE approves a district's budget plan, the COE review can provide useful feedback and point out key areas that merit the district's attention. For example, the COE may point out that more accurate estimates of the school district's annual enrollment would help prevent inadvertent deficit spending in future years. Such an analysis gives the district additional information on the specific issues that the COE thinks are important in ensuring the long–term fiscal health of the district.

Disapproved Budgets Are Rare. Given the constant communication between districts and COEs, school districts typically have a clear understanding of the actions they must take to have their budget plans approved by the COE. As a result, a disapproved budget is rare. Since 1991–92, an average of three school districts have had their budgets disapproved each year (less than 1 percent of all districts). A Budget Review Committee also is a very rare occurrence. Roughly seven of eight districts with disapproved budgets resolved the issue working directly with their COE.

Interim Reporting

After reviewing a school district's adopted budget, COEs review the financial health of school districts at two points during the school year. The information required and report due dates are shown in Figure 2. By December 15, school districts must provide COEs with a financial report based on revenue and expenditure data as of October 31. By March 15, districts must provide a financial report based on data as of January 31. These reports are known as first interim and second interim. Districts must provide COEs with an interim report that includes revenue and expenditure estimates for the current year and two subsequent fiscal years. The COE reviews each district's report and uses the criteria and standards to place districts into one of the following three categories:

- Positive Certification. Will meet obligations for current and two subsequent years.

- Qualified Certification. May not meet financial obligations for current or either of the two subsequent fiscal years.

- Negative Certification. Will be unable to meet financial obligations for current or subsequent fiscal year.

Highest Number of Qualified and Negative Certifications in 2009–10 and 2010–11. Figure 3 shows the number of qualified and negative ("at–risk") districts each year since 1991–92. As the figure shows, the number of districts with such certifications significantly increased beginning in 2007–08. The year with the most at–risk districts was in 2009–10, the first full year following major state reductions in education funding. Given certifications are based on the district's fiscal condition in the current and two subsequent fiscal years, assumptions about future funding have a significant effect on a school district's certification. The basis for assessing second interim reports (submitted based on data as of January 31) is the Governor's January 10 budget proposal. If the Governor's budget proposes to make significant budget reductions, districts are more likely to be certified as negative or qualified if they do not have a plan for implementing the Governor's proposed reductions.

First Level of Intervention for At–Risk Districts

The oversight process is designed to address the school district's fiscal problems with the least amount of intervention possible. When a district is certified as qualified or negative during the interim reporting process, the state's fiscal oversight system provides COEs with certain tools to assist school districts as well as creates additional reporting requirements for these districts. Existing law also allows COEs to use these tools if a school district received a positive certification but now appears unable to meet its financial obligations. These tools and additional reporting requirements are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Intervention for At–Risk Districts

|

First–Level Intervention for Qualified and Negative Districts

|

|

COEs Must Do at Least One of the Following:

|

|

|

- Conduct a study of the district's financial condition.

|

- Require a report of the district's financial projections.

|

- Require an update of cash flow and expenditure estimates.

|

- Require that the district submit a proposal to address its fiscal health.

|

- Assign FCMAT to review the district's management of the teacher workforce.

|

- Withhold compensation from the district superintendent or governing board members if they do not provide all requested information.

|

|

Reporting and Review for All At–Risk Districts:

|

- "Third interim" report due June 30.

|

- COE must review and comment on proposed collective bargaining agreements.

|

- COE must approve issuance of certain debt.

|

- District may be subject to audit or review by State Controller.

|

|

Second–Level Intervention for Negative Districts

|

|

COEs Must Do at Least One of the Following:

|

- Assign a fiscal advisor.a

|

- Develop and impose budget revisions in consultation with SPI and local governing board.

|

- Stay or rescind local governing board action.

|

- Assist in developing budget or financial plan.

|

Tools to Assist School Districts

When a school district is certified as qualified or negative, the COE will take action to develop further understanding of the district's financial condition and help the district develop a plan for returning to fiscal health. Under state law, the COE must take at least one of the following actions:

- Assign a Fiscal Expert. The COE can appoint a fiscal expert, at no cost to the district, to help the district improve its fiscal health. Fiscal experts tend to be former school district superintendents or chief business officers with significant experience in school district fiscal issues. The expert, however, has no formal authority to impose his or her recommendations. The school district governing board still maintains all authority to make the necessary changes to improve the district's fiscal health. Based on our discussions with COE staff, assigning a fiscal expert is common, particularly for school districts with a negative certification.

- Conduct a Study of Financial Condition. The COE can conduct a study of the school district's financial condition to develop a more thorough understanding of the school district's financial problems. The study must include a review of the internal controls currently in place to manage district expenditures.

- Require Report of Financial Projections. To develop a greater understanding of the district's finances, the COE can require the district to submit financial projections of all fund and cash balances for the current and subsequent fiscal years.

- Require Update of Cash Flow and Expenditure Estimates. The COE can require the district to revise its financial documents to ensure that information is accurate and based on the latest information. Specifically, the COE can require the district to review its accounting of existing contracts and financial transactions, update its cash flow analyses, and resubmit its monthly or quarterly budget revisions.

- Require District Submit Proposal to Address Fiscal Health. The COE can direct the district to submit a proposal that would address the primary fiscal issues that caused the district to be certified as qualified or negative.

- Assign FCMAT to Review Teacher Workforce Issues. The COE can assign FCMAT to study and provide recommendations to streamline and improve the district's teacher hiring process, teacher retention rate, extent of teacher misassignments, and supply of highly qualified teachers.

- Withhold Compensation. The COE can withhold the compensation of the district superintendent or governing board members if they fail to provide all requested financial information.

Additional Oversight for All At–Risk Districts

In addition to the above corrective actions that COEs can take, qualified and negative school districts are subject to additional requirements for reporting and review. These requirements ensure that the COE is aware of any changes to a district's fiscal condition that would require further intervention or support.

Third Interim Reporting. A school district certified as qualified or negative at second interim is required to submit a third interim report by June 1. This report must be based on information through April 30. Third interim reports provide a COE with additional information to ensure that the school district's fiscal condition has not significantly deteriorated during the subsequent months since the second interim report.

COE Review of New Collective Bargaining Agreements. Prior to approving any new collective bargaining agreement, qualified or negative school districts must allow the COE at least ten working days to review and comment on whether the proposed agreement would endanger the fiscal health of the district. The COE notifies the school district governing board, school district superintendent, and all parent and teacher organizations within ten days if the agreement would endanger the fiscal well–being of the district. The school district is required to provide all information to the COE necessary to assess the cost of the collective bargaining agreement and list any budget revisions that the school district must make to have sufficient funds to fulfill the agreement. If the school district does not make these revisions, it will receive a qualified or negative certification in the subsequent interim report.

COE Approval to Issue Certain Debt. Prior to issuing non–voter approved debt, a qualified or negative school district must obtain a determination from the COE that the district would likely be able to repay the debt. School districts issue non–voter approved debt for a number or reasons. For example, many districts issue certificates of participation to finance facility projects or issue tax and revenue anticipation notes to meet their cash flow needs. The COE determination provides an additional layer of oversight to ensure that school districts do not issue debt that is unlikely to be repaid. The COE also must issue the determination for non–voter approved debt in the year following the negative or qualified certification, even if the district has a positive certification.

Possible Controller Audit or Review. When a district is qualified or negative, the State Controller has the authority to audit or review the fiscal condition of the district at any time during the year. The controller, however, rarely exercises this authority.

COEs Can Intervene in Some Districts With Positive Certification

The COE's assessment of a school district's financial condition can change shortly after major reporting periods, as the school district updates its revenue and expenditure estimates based on the latest data. In some cases, a school district with a positive certification may be at risk of not meeting its financial obligations due to changes in its revenue or expenditure estimates. If a COE finds that a district with positive certification would be classified as qualified or negative using more up–to–date information, existing law allows COEs to use the same tools that can be used for qualified or negative districts. This ensures the COE can assist any district whose fiscal situation has deteriorated after interim reporting was completed.

Second Level of Intervention for Negative Districts

If a district's fiscal condition has not improved after the initial level of intervention, the existing fiscal oversight system allows COEs to impose more intense interventions if a district has a negative certification (or if the district has a positive certification but is later deemed to be unable to meet its obligations in the current or subsequent fiscal year, the equivalent of a negative certification). In these cases, the COE must notify the school district governing board, the school district superintendent, the SPI, and all parent and teacher organizations in the district that the school district still appears unable to meet its financial obligations. In the notification, the COE must include its assumptions in making the determination. As Figure 4 shows, the COE then must take at least one of the following actions:

- Assign Fiscal Advisor. The COE can assign a fiscal advisor to assist the school district. The fiscal advisor can take the actions listed below on the COE's behalf.

- Develop and Impose Budget Revisions. The COE can develop and impose a budget revision, in consultation with the school district and SPI, to ensure the district will be able to meet its financial obligations in the current fiscal year. The school district can appeal the revision to the SPI if it finds the revision unnecessary or believes the revision is larger than necessary for the district to be able to meet its financial obligations. The revision cannot violate state or federal law and cannot conflict with the school district's existing collective bargaining agreements. Because the revision must be developed in consultation with the school district and cannot change the terms of any collective bargaining agreements, COEs rarely impose budget revisions.

- Stay or Rescind District Actions. The COE can stay or rescind any action taken by the local governing board of the school district if the COE finds that the district would be unable to meet its financial obligations as a result of the action. For example, the COE can rescind the district governing board's approval of a new or revised collective bargaining agreement if the COE finds the district could not afford the agreement. Of the powers granted to the COE to assist districts with negative certification, stay–and–rescind authority is the strongest. Because COEs may exercise this additional authority and overturn the actions of the local governing boards, local boards presumably have greater incentive not to take any action that could result in the districts being unable to meet their financial obligations in the future.

- Assist in Developing Budget or Financial Plan. The COE can help the school district develop a multiyear budget or financial plan to enable the district to meet its future obligations.

The Ultimate Intervention: Emergency Loan and State Takeover

When a school district is unable to meet its financial obligations, the state will intervene to ensure the school district continues to provide educational services for its students. In these cases, a number of actions are taken to prepare the school district for an emergency loan, process the emergency loan, and transfer administrative control of the district to the state. This process can result in significant changes to the governance and finances of a school district. Figure 5 summarizes the various changes that occur with an emergency loan and state takeover.

Cash Flow Ultimately Determines a District's Need for Emergency Loan. Whereas a school district's return to fiscal health is primarily determined by taking action to avoid deficit spending in future years, lack of available cash is the most important factor that results in a district needing an emergency loan. School districts can continue to run deficits and meet their financial obligations if they have sufficient cash reserves or can borrow from external sources. As the district's fiscal condition deteriorates, however, the district's reserve levels decrease and lenders become less willing to provide cash to the school district. Eventually, if no steps are taken to improve the district's condition, the district will be unable to borrow and will need an emergency loan.

Districts Prepares for Emergency Loan. If the school district appears unable to make the necessary adjustments to meet its financial obligations, the district (often in coordination with the COE) must take immediate action to notify state officials and the public. The COE or FCMAT staff may attend a meeting of the school district governing board to discuss the consequences of receiving an emergency loan from the state. School district or COE staff also may contact members of the Legislature and notify them that emergency legislation may be necessary for the district to remain solvent. Because the process of securing an emergency loan typically takes several months, the district and COE must act early to ensure the district has cash available to meet its monthly obligations, such as payroll and utility costs. Prior to receiving the loan, however, the district must develop a plan for improving its financial condition and have the plan approved by the COE and submitted to the SPI, the Legislature, the Department of Finance, and State Controller.

Financial Effects

Emergency Loan Must Be Provided by Legislation. For a district to secure an emergency state loan, the Legislature must adopt authorizing legislation. The legislation typically is carried by a legislator who represents the Assembly or Senate district in which the school district resides. The legislation provides a direct General Fund appropriation to the school district. This appropriation is only intended to serve as short–term financing until the school district secures another loan that will provide longer–term financing.

District Finances Loan Using Bonds. Until 2004, the state provided emergency loans to school districts with General Fund monies at relatively low interest rates. In that year, however, the state passed Chapter 263, Statutes of 2004 (AB 1554, Keene), which required districts to obtain funding by selling bonds to private investors through the state's Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank (I–Bank). The legislation was intended to relieve the General Fund from the burden of financing school district emergency loans in the event that several large school districts were unable to meet their financial obligations. Under the Chapter 263 system, the I–Bank issues bonds on behalf of the district to finance the emergency loan. The process of developing and selling bonds can take several months. Once the bonds are issued, the district uses part of the proceeds to repay the state's General Fund appropriation and uses the remaining funds to pay its obligations. Funds to make debt service payments are intercepted from the school district's revenue limit funding.

District Bears Costs of Loan and Oversight. School districts are responsible for paying the interest and issuance costs of the bonds, typically over a 20–year period. (Issuance costs tend to be fixed costs that do not vary significantly with the size of a loan.) The school district also must pay for the salaries of fiscal experts, state administrators, trustees, auditors, and other employees who have been hired to provide assistance to the district. The loan amount is intended to provide the district with sufficient funds to meet all these obligations.

Changes in Governance

Local Governing Board Loses All Authority. If the emergency loan received by the district is more than 200 percent of its recommended reserve levels (typically about 6 percent of total expenditures), the governing board loses its authority over the administration of the school district. The SPI assumes all of the duties and powers of the local board and appoints a state administrator to act on his or her behalf. The local board serves as an informal advisor to the state administrator and does not receive any form of compensation from the district. State law also requires that the district superintendent no longer be employed by the district.

Existing Contracts and Obligations Remain. The primary goal of the state administrator is to restore the fiscal solvency of the school district as soon as possible. In achieving this goal, the state administrator is to develop a budget and financial plan for restoring the school district's fiscal health. The state administrator, however, is not granted any additional powers to change existing collective bargaining agreements or other contracts entered into by the school district. These agreements must be renegotiated with interested parties.

Authority Returns to Local Governing Board After Careful Review. While the state administrator is in control, the SPI and FCMAT are to develop standards and expectations for the district's performance in five key areas: (1) financial management, (2) pupil achievement, (3) personnel management, (4) facilities management, and (5) community relations. The district can regain power in any of these areas if it meets these standards. When the district meets the standards in all five areas and the state administrator determines that the district is likely to comply with its recovery plan, the local board regains control of the district and the administrator leaves. Until the loan is repaid in full, however, a state trustee with stay–and–rescind powers is assigned to oversee the district. In practice, the state administrator typically maintains control for several years before the local board regains its powers.

If Loan Is Small, State Trustee Is Appointed. If the emergency loan received by the district is less than 200 percent of its recommended reserve levels, then a state trustee is appointed to oversee the school district. Although the local governing board retains its legal authority over the district, the state trustee has the power to stay or rescind any action of the local board that would have a negative effect on the financial condition of the school district. The state trustee is removed when the district repays the emergency loan and the SPI determines that the district is likely to follow the fiscal plan approved by the COE.

Assessment of System

Given the substantial fiscal challenges that school districts have faced over the last two decades, the state's fiscal oversight system has been effective in ensuring that school districts remain fiscally healthy. The system appears to have reduced the number of school districts requiring state assistance and has provided oversight and support while still allowing school districts to have final decision–making authority in most cases. Although the oversight process appears to be very effective, we have some concerns with the cost school districts must bear for an emergency state loan. Nonetheless, other permanent, lower cost options likely do not exist. For example, financing these loans through the state General Fund likely is not feasible when the state's overall budget condition or short–term cash flow situation is poor.

Existing System Generally Has Been Effective

Fewer Districts Have Received Loans Since the Implementation of Existing System. Since the implementation of the current oversight system in 1991, fewer school districts have required emergency loans from the state to meet their financial obligations. From 1979 to 1991, 26 school districts received emergency appropriations from the state. As Figure 6 shows, eight districts have received emergency loans in the 20 years since the new system was adopted.

Figure 6

Emergency Loans to School Districts Since 1991

(Dollars in Millions)

|

School District

|

Year of Legislation

|

Current State Involvement

|

Total Loan Amount

|

Interest Rate on Loana

|

Pay–Off Date of Loan

|

|

King City Joint Union Highb

|

2009

|

Administrator

|

$13.0

|

5.44%

|

October 2028

|

|

Vallejo City Unified

|

2004

|

Trustee

|

60.0

|

1.50

|

January 2024

|

|

Oakland Unified

|

2003

|

Trustee

|

100.0

|

1.78

|

January 2023

|

|

West Fresno Elementary

|

2003

|

None

|

1.3

|

1.93

|

December 2010

|

|

Emery Unified

|

2001

|

None

|

1.3

|

4.19

|

June 2011

|

|

Compton Unified

|

1993

|

None

|

20.0

|

4.39

|

June 2001

|

|

Coachella Valley Unified

|

1992

|

None

|

7.3

|

5.34

|

December 2001

|

|

West Contra Costa Unified

|

1991

|

None

|

29.0

|

1.53

|

January 2018

|

Given the effectiveness of the existing oversight and intervention system, we think preserving the existing system is critical for ensuring that sufficient support exists to prevent additional districts from requiring an emergency loan.

Our review indicates that the oversight system established in 1991 has been effective in preserving school district fiscal health and helping school districts avoid emergency loans. Most notably, during the more than 20 years the new system has been in effect, 8 districts have received emergency state loans whereas 26 districts required such loans in the 12 years prior to the new system. Additionally, under the new system, the number of districts with qualified and negative budget certifications has increased in tight budget times, but without a corresponding increase in the number of emergency loans required. This suggests the system's structure of support and intervention is serving a critical early warning function—allowing districts to get the help they need while fiscal problems tend to be smaller and more manageable.

Given the system has proven to be generally effective over the last two decades—during both good and bad economic times—we recommend the system be preserved. In recent years, however, certain state actions temporarily have reduced the system's effectiveness. In particular, in the last three years, the state temporarily has reduced the ability of COEs to identify districts on the road toward fiscal distress and provide these districts with additional oversight and assistance. Moving forward, we caution the state against adopting these types of actions. As districts continue to struggle in the aftermath of the recent recession, we believe preserving the existing oversight system is vital for fostering the ongoing fiscal well–being of districts.