Executive Summary

Background. Under state and federal law, all individuals who face criminal charges must be mentally competent to help in their defense. By definition, an individual who is incompetent to stand trial (IST) lacks the mental competency required to participate in legal proceedings. In California, there is a monthly statewide waitlist that averages between 200 and 300 individuals alleged to have committed felonies whom the courts have deemed mentally incompetent to stand trial. These individuals are waiting for a bed to become available in a state hospital so they can undergo evaluation and receive treatment to restore them to competency. Once at a state hospital, the state spends significant resources to provide treatment for this population-approximately $170 million annually.

Waitlist Received Courts Attention. Traditionally, these individuals have waited in county jails before being transferred to state hospitals. A recent state court case has highlighted the legal issues in the long wait times experienced by ISTs and resulted in a recommendation by the courts that IST commitments be transferred to a state hospital within 35 days. However, many ISTs currently wait in jails longer than 35 days. The lack of physical space to house IST commitments combined with the difficulty in staffing key personnel in state hospitals has maintained a steady backlog of IST commitments in county jails. If the state were required to eliminate its waitlist in its entirety, it could face costs of $20 million annually.

Pilot Program Could Reduce Waitlist. The Department of Mental Health (DMH) received an appropriation from the Legislature in the amount of $4.3 million in 2007-08 to begin pilot programs to examine alternative approaches to addressing the IST waitlist problem. After several years of delays, the department, working with a private vendor, established a pilot program in San Bernardino County to treat ISTs in the county jail instead of at a state hospital. The nine-month results are promising in regard to the ability of the program to reduce the IST waitlist. Specifically, we find the pilot program provides less incentive for potential malingerers, has greater flexibility to hold down costs, and is able to restore ISTs to competency in a shorter amount of time than the state hospitals. Additionally, the number of referrals from courts into IST treatment has decreased, possibly because treatment in a county jail is less appealing to defendants who may use a claim of incompetency as a defense strategy to keep out of prison.

Pilot Program Brings Public Sector Savings. We find expansion of the pilot not only has the potential to reduce the waitlist, but also to significantly decrease costs to the public sector. We estimate the San Bernardino County pilot has resulted in approximately $1.4 million in public sector savings after a nine-month period-providing treatment at a cost of about $70,000 less per IST commitment.

Expand Pilot Program. If the Legislature wishes to reduce the waitlist, we recommend that it do so first by expanding the pilot into counties with historically long waitlists. Those counties would be the ones that ordinarily send their IST commitments to Patton and Atascadero state hospitals. Our analysis indicates that such an approach would result in significant savings for the state and counties in the costs of providing services to IST commitments. Furthermore, it would reduce state and county exposure to potential future court involvement from delays in the treatment of ISTs held in county jail longer than recommended by the courts.

|

Introduction

Under state and federal law, all individuals who face criminal charges must be mentally competent to help in their defense. By definition, an individual who is IST lacks the mental capacity required to participate in legal proceedings. While a person may be IST because of a mental illness or for other reasons (such as a developmental disability), this report focuses on the former. For individuals who are accused of felonies and who are seriously mentally ill, California generally provides mental health treatment in state hospitals to restore them to competency. At the time this report was prepared, more than 1,000 persons, about 20 percent of the state hospital population, were IST commitments. Due to a myriad of issues in state hospitals, the state has had a waiting list for entry into the state hospitals by ISTs for some time. For various reasons discussed in this report, our analysis finds that it is in the best interest of the state to attempt to reduce its waitlist population in order to provide prompt treatment for these commitments, reduce county costs, and avoid potentially significant future state costs.

In this report we (1) provide an overview of the state process for handling IST commitments, (2) assess the cause of the IST waitlist problem, (3) examine an ongoing pilot project in San Bernardino County to expedite the restoration of ISTs to competency, and (4) present our recommendations for steps to address the waitlist problem.

Background

Below, we describe how persons accused of misdemeanors and felonies are deemed to be ISTs. We also describe how felony IST commitments are restored to competency.

U.S. Supreme Court Requires Competency. The 1960 U.S. Supreme Court decision Dusky v. United States found that a defendant must have "sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding" and "a rational as well as factual understanding of the proceedings against him." In short, being competent means the defendant both understands the charges against him and has sufficient mental ability to help in his or her own defense. The 1972 U.S. Supreme Court decision Jackson v. Indiana found the state violated a criminal defendant's federal constitutional right to due process of law by involuntarily committing an individual for an indefinite amount of time because of his incompetency to stand trial. The U.S. Constitution (as well as the State Constitution) states that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of the law. In the Jackson case, the court ruled that "a person charged by a State with a criminal offense who is committed solely on account of his incapacity to proceed to trial cannot be held for more than the reasonable period of time necessary to determine whether there is a substantial probability that he will attain that capacity in the foreseeable future."

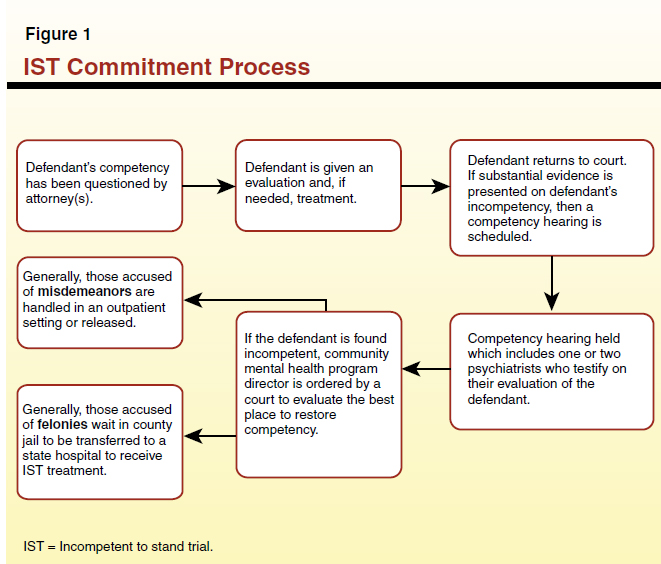

How Is Incompetency Determined? Under state law, when a defendant's mental competency to stand trial is in doubt, the courts must follow a specific competency determination process before the defendant can be brought to trial. Figure 1 summarizes this process.

Typically, the process is initiated by defense attorneys reporting their concerns about their clients' mental capacity to the judge. The judge then orders the defendant to undergo an initial evaluation by court-appointed mental health experts, during which time court proceedings are suspended. The court assesses the evaluation, which guides it in deciding whether to hold a competency hearing. If a hearing is ordered, one or two additional experts are appointed by the court to assess the defendant's competency and the defendant has the opportunity to challenge their conclusions during this hearing. Generally, a defendant charged with a violent felony and found incompetent to stand trial will be ordered to undergo treatment at a state hospital to be restored to competency.

Judges typically order a community mental health program director or designee to determine the most appropriate treatment facility for IST defendants. The program director is then required to submit a report with findings to the court within 15 days. Defendants charged with misdemeanors are usually provided treatment in a local mental health facility, provided treatment in an outpatient setting, or released with the charges dismissed. Defendants charged with nonviolent, non-sexual felonies are sometimes treated in the community. Those defendants charged with violent and/or sexually violent felony crimes are committed to state hospitals to have competency restored. If there is a bed available in a state hospital for felony defendants, they are transferred from the jail to the state hospital. However, if there is not a bed available, then they are usually put on a statewide waitlist and held in a county jail until a bed becomes available.

Court Recommendation Increases Pressure for Speedy Transfer From Jail to State Hospitals. California law requires that state hospitals admit, examine, and report to the court on the likelihood of competency restoration within 90 days of the defendant's commitment in order to avoid violating the defendant's constitutional right to due process. In a case known as Freddy Mille v. Los Angeles County, the Second District Court of Appeal ruled in 2010 that a person determined to be IST must be transferred to a state hospital within a "reasonable amount of time" in order to comply with this 90-day statutory requirement. The court specifically held that the provision of medications alone to mentally ill defendants within the confines of a jail-a common practice-did not legally constitute the kind of treatment efforts that are required to restore someone to mental competency. Thus, the court held, the transfer of such defendants in a timely fashion from jail to a state hospital (or perhaps to a community treatment center) is legally required. This legal precedent is binding across the state.

As the result of a series of rulings, the courts have recommended that the transfer of IST defendants from jail to a state hospital be completed in no more than 30 to 35 days. (This would still leave 55 to 60 days for the examination and assessment of competency.) Thus, the Mille court case increased the pressure on state hospitals to admit IST commitments promptly and report back to the courts within the required 90-day period.

The State Hospital Role in Restoring Competency. The state's five state hospitals-Atascadero, Coalinga, Metropolitan, Napa, and Patton-provide treatment to a combined patient population of over 5,000 (see the nearby box for more information on these facilities). All but Coalinga serve ISTs. State hospitals treat patients under several other commitment classifications, including not guilty by reason of insanity and mentally disordered offenders. Additionally, two psychiatric programs located on the grounds of state prisons at Vacaville and Salinas Valley have a combined inmate patient population of less than 700, however, these programs typically have served only a handful of ISTs. All of these programs are administered by the state DMH. The process for determining which commitments go to which hospital is complicated. However, ISTs from certain counties tend to be transferred to certain state hospitals. For example, Patton State Hospital typically accepts admissions from Kern, Los Angeles, Merced, Orange, Riverside, Santa Barbara, San Bernardino, San Diego, Stanislaus, and Ventura counties.

California's State Hospital System

California is home to five state hospitals and two in-prison psychiatric programs which specialize in treating the mentally ill.

Atascadero State Hospital is located in the Central Coast and houses and all-male maximum security forensic patient population. As of July 2011, it housed over 1,000 patients.

Coalinga State Hospital is California's newest state hospital. Located in the City of Coalinga, it houses over 700 patients, most of whom are Sexually Violent Predators (SVPs). Coalinga has been reserved for this specific SVP population and does not treat individuals who are incompetent to stand trial.

Metropolitan State Hospital houses over 600 patients and is located in the city of Norwalk. Metropolitan does not accept individuals who have a history of escape from a detention center, a charge or conviction of a sex crime, or one convicted of murder.

Napa State Hospital, located in the city of Napa, is classified as a low- to moderate-security level state hospital. It housed over 1,000 patients as of July 2011.

Patton State Hospital treats approximately 1,500 patients and is primarily a forensic hospital. Located in San Bernardino County, Patton has seen its forensic population grow quickly in the past few years.

Vacaville and Salinas Valley Psychiatric Programs are not hospitals, but psychiatric programs designated to treat inmates with mental health issues. The Vacaville and Salinas Valley Psychiatric Programs are located inside prisons. Both programs treat less than 700 inmate-patients combined.

|

Felony IST commitments may suffer from one or more mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Treatment is provided through a combination of medications, therapeutic classes (like art), and counseling. Additionally, specialized units within the state hospitals teach classes on basic court procedures, giving IST commitments the capability of identifying the judge, defense attorneys, and prosecutors. This allows defendants to understand the charges against them and assist in their own defense once they have been restored to competency and proceed to trial.

California Dedicates Significant Resources to Competency Restoration. California dedicates significant resources to the competency restoration process. With an average daily population of 1,000 ISTs and a cost of approximately $450 per day per patient, the state spends approximately $170 million annually on this category of patients. (This estimate does not include any facilities-related costs.) In recent years, several factors have driven up these costs for ISTs and for other categories of patients. For example:

- As a result of enforcement actions brought by the U.S. Department of Justice under the authority of the Civil Rights for Institutionalized Persons Act, the state was required to increase staff-to-patient ratios and expand the services offered to patients in its facilities.

- Increased concerns about security, stemming mainly from acts of violence committed by patients against staff and other patients, have also increased state hospital operating and capital outlay costs. These increased security measures include the installation of new personal alarm systems and the deployment of more security staff on the grounds.

How Long Does It Take to Restore Competency? Once at a state hospital, it takes an average of six to seven months to restore a defendant to competency. Under state law, defendants charged with a felony and committed to state hospitals for competency treatment are not permitted to spend longer than three years or the maximum prison term the court could have sentenced the defendant to serve if they were found guilty of the crime, whichever is shorter. Additionally, time spent at state hospitals can be applied to the sentence of the individual if they are found guilty of a crime after their competency has been restored.

Limited State Hospital Beds Have Resulted In a Significant IST Waitlist

The state faces a long wait list due to a shortage of staff and/or psychiatric beds at the hospitals. Therefore, county jails have had to hold IST commitments in county jails longer than the court-recommended 35-day time period. According to data collected by DMH, during 2009-10, defendants waited an average of 68 days, almost double the 35 days recommended by the courts, for transfer from a county jail to a state hospital for evaluation. (This average excludes IST patients headed for Metropolitan State Hospital, for which data are not available.) Figure 2 shows the average county jail wait times for IST commitments by facility. Napa is, on average, accepting patients within the time limits recommended by the courts. (One possible reason for the low average wait time for Napa is the relatively lower number of ISTs originating from Northern California counties, which feed into Napa.) The data indicate, however, that almost half of the transfers to Napa are still occurring after 35 days have lapsed. Moreover, IST commitments headed both to Atascadero and Patton are significantly exceeding 35 days. In the case of Patton, it is taking an average of 87 days for ISTs to be transferred from their county jail. Some transfers are taking as long as 162 days after the recommended 35-day limit by the courts.

Figure 2

Average IST Wait Time Varies Significantly

2009-10

|

State Hospitala

|

Average Number of Days Until Transfer to State Hospital

|

|

Atascadero

|

53

|

|

Napa

|

33

|

|

Patton

|

87

|

A total of 1,261 persons were placed on an IST waitlist at some point during 2009-10. Of this group, 923 commitments stayed on the waitlist longer than the recommended 35-day period. Since 2007, the IST waitlist has fluctuated between 200 and 300 persons at any given time. At the time this report was prepared, there were 264 persons on the IST waitlist.

Costs to Counties From Serving ISTs in County Jails. Since IST commitments wait in county jail before being transferred to a state hospital, counties pay the cost of their care during that time. Statewide, jails report spending $92 per day on average for all their inmates, with costs for IST patients generally expected to be higher because of their medical needs (average daily costs vary from county to county). As shown in Figure 3, we estimate that counties are spending a combined annual total of at least $3.5 million to hold IST commitments in their jails beyond the 35-day period while they wait for a state hospital bed to become available. (The actual cost is probably more than we have estimated because it does not include IST commitments held at Metropolitan and because the $92 county jail daily rate we assume likely understates the costs to counties for an IST population that typically has high medical needs.) Patton, which had the longest wait times for IST transfers from the county jails it serves, accounted for more than 70 percent of the costs. As shown in the figure, delays in IST admissions to Atascadero and Napa resulted in lesser, but still significant, costs to counties.

Figure 3

IST Waiting Lists Prove Costly to Counties

2009-10 (In Thousands)

|

State Hospitala

|

Cost to Counties Due to That Hospital's Waitlist

|

|

Atascadero

|

$648

|

|

Napa

|

345

|

|

Patton

|

2,554

|

|

Total

|

$3,545

|

Why State Hospital Beds for IST Commitments Are Limited. The ability of the state hospital system to accept new commitments for ISTs (as well as for certain other categories of patients) is constrained by the physical capacity of these facilities and the state's ability to hire sufficient staff. The DMH has struggled with staffing key personnel classifications, with some state hospitals reporting vacancy rates as high as 40 percent in occupations like staff psychiatrists. The state has aggressively tried to recruit and retain key personnel but has faced challenges in filling positions. The state has used overtime by hospital staff and private contractors to help fill some of the staffing gap. However, the amount of overtime that staff members can work is limited and the use of contractors has proven to be expensive.

In theory, the state has the option of trying to curb other types of patient admissions to create space for IST commitments. However, the risk to public safety posed by other patient population groups, and requirements imposed as a result of other federal court cases, limit the state's flexibility in its use of state hospital beds. For example, admissions of mentally ill prison inmates to the state hospitals required as a result of the longstanding Coleman v. Schwarzenegger case are generally a higher priority for admission than ISTs. The DMH has adopted rules establishing the following priority for admissions of penal code commitments: (1) Sexually Violent Predators, (2) Mentally Disordered Offenders, (3) Coleman inmate-patients, (4) Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity, and (5) ISTs. Thus, ISTs are usually the last group to be placed in a state hospital, having priority only over persons who receive civil commitments to state hospitals under the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act.

As a result of these various constraints, state hospitals have been unable to solve the IST waitlist problem.

Potential Fiscal Implications for the State. If the state were required by the courts to comply immediately with Mille to eliminate the backlog of ISTs solely by expanding staff capacity and filling the remaining available beds in the state hospital, it would face ongoing annual costs of about $20 million. The Mille case highlights the risk of potential problems that could arise for the state and counties as a result of the continued waitlist for IST admissions to state hospitals. The holding of mentally ill defendants in the jails for a longer period than recommended by the courts creates a risk of claims by some defendants that their due process rights are being violated.

How a San Bernardino Pilot Project Helped A County Address Its IST Waitlist

In 2007-08, the Legislature approved a $4.3 million budget request from DMH for additional funding for a pilot program to test a more efficient and less costly process to restore persons determined to be IST to competency. These monies were intended to provide 40 beds at the county level for one year for competency restoration services in lieu of providing this treatment in state hospitals.

After several years of delay, ultimately only 20 beds were established in San Bernardino County using about $300,000 of the budgeted amount. After conducting a competitive bidding process, DMH entered into a contract with Liberty Healthcare Corporation to establish the new program in that one county. Liberty, a private provider with experience in California and other states in providing treatment to ISTs and other types of offenders with mental health problems, in turn established a contractual relationship with San Bernardino County to implement this pilot at its county jail beginning in January 2011. Under these agreements, Liberty provides intensive psychiatric treatment, acute stabilization services, and court-mandated services for IST patients. San Bernardino County jail officials provide security and management of the IST population held in the jail, as well as food and medication.

The state pays Liberty $278 per day for these services-much less than the $450 cost per day of a state hospital bed. Using part of these monies, Liberty, in turn, passes through $68 per day per commitment to the county for various food and housing costs and pays for the medication. Under the terms of its contract with the DMH, Liberty provides services to ISTs in the jail for a maximum of 70 days. At that point, those who have not been restored to competency-typically because their mental health issues are more severe-are transferred to the state hospital system, where their treatment continues. Also, a small portion of those who cannot be restored to competency by Liberty are those who speak languages Liberty is not staffed to handle.

Data on Liberty's Nine-Month Results

In accordance with the terms of its contract with DMH, Liberty submits monthly progress reports to the DMH outlining the number of patients it treats, the number it transfers to Patton State Hospital, the length of time that each of its IST patients have been in treatment, and specific diagnostic patient information. The data collected for the first nine months of the operation of the program are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Initial Outcomes Show Almost Half of Patients Restored to Competency

January to September 2011

|

|

Number of Patients

|

Average Days in Treatment

|

|

Fully restored

|

19

|

54

|

|

In program

|

13

|

N/A

|

|

Transferred to Patton

|

10

|

81

|

|

Total Admissions

|

42

|

63

|

Our analysis indicates that the pilot program has had several important outcomes.

Our analysis indicates that the San Bernardino County pilot program is resulting in some fiscal benefits both for the county and for the state.

Thus far, San Bernardino County estimates that it has been able to achieve net savings of more than $5,000 for each IST commitment Liberty treats. Based on the first nine months of the program, during which 42 commitments were under Liberty's care, San Bernardino County thus estimates that it has saved about $200,000. The annual savings to the county would be higher.

Other factors might modestly change the net fiscal impact to the state, although they are hard to calculate at this time. For example, there is no way to know at this time what cost impacts are associated with the group of ten IST commitments who received treatment from Liberty but were eventually transferred to Patton. If these individuals subsequently had a shorter stay at Patton because of the treatment they received from Liberty before their transfer, the pilot project would result in some additional savings for the state. If their treatment by Liberty did not reduce their subsequent stay at Patton, the pilot program would in effect result in some added state costs for this group. The DMH does not now collect data that would enable us to determine how their treatment at Liberty is affecting their subsequent stays in the state hospital system, but our analysis suggests they are unlikely to greatly change the overall level of savings the pilot program is providing for the state.

Several key factors appear to be behind the programmatic and fiscal benefits that have resulted so far from the pilot program.

As noted in this report, the state faces significant legal risks because of state court rulings in the Mille case. Also, counties are incurring significant costs for IST commitments being held in county jails for a longer period than recommended by the courts. However, the approach the state has used in the past to reduce the waitlist of ISTs being held in county jails-expanding the staffing and capacity of the state hospital system-would likely be expensive and problematic because of ongoing staffing shortages and other problems.

If the Legislature concludes that additional action is needed to reduce the IST waitlist, we recommend the Legislature do so by expanding the San Bernardino County pilot program. Providing treatment to IST commitments in other county jails with a private contractor, largely along the lines of the San Bernardino County model, would not only result in significantly less public sector costs to provide this treatment (over $70,000 per commitment), but also more timely and potentially more effective services to ISTs.

As we have discussed in this report, the state is subject to a legal risk if long wait times for transfers to state hospitals by the IST commitment population continue. To the extent the state has the resources, we recommend expanding the pilot program to those counties with a sufficient IST waitlist population. Replicating the success that San Bernardino County has had in restoring defendants to competency more quickly and less expensively could resolve the waitlist issue, ensure due process, and thereby preempt such court action.