Executive Summary

The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]), commonly referred to as AB 32, established the goal of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. In order to help achieve this goal, the California Air Resources Board (ARB) recently adopted regulations to establish a new "cap–and–trade" program that places a "cap" on the aggregate GHG emissions from entities responsible for roughly 80 percent of the state's GHG emissions. The ARB will issue carbon allowances that these entities will, in turn, be able to "trade" (buy and sell) on the open market. A cap–and–trade program offers the potential to reduce GHG emissions more cost–effectively than traditional "command–and–control" regulations.

Key Trade–Offs Inherent in Designing a Cap–and–Trade Program. In this report, we analyze the design of the cap–and–trade program as adopted by ARB and the important policy choices inherent in this design that have broad environmental, fiscal, and policy implications. The ARB has made these policy choices in the context of AB 32's competing and potentially conflicting goals and requirements. In general, our analysis indicates that ARB has made a reasonable effort to balance various policy trade–offs, such as those involving (1) efforts to prevent the unintentional increase in GHG emissions outside of California (referred to as "emissions leakage"), (2) the use of offset credits, (3) actions to reduce volatility in the price of allowances and offset credits, (4) auction and market oversight, and (5) enforcement of cap–and–trade requirements. As we demonstrate in this report, there is no one "right" way to design such a complex program. Thus, the Legislature will want to carefully consider both potential changes to the design of the cap–and–trade program, as well as possible alternatives, depending on its priorities. We present various options for program changes that could be adopted to meet various legislative priorities.

Significant State Revenues Planned to Be Raised. The ARB plans to auction (rather than give away for free) an increasing portion of carbon allowances over time. Annual revenues from the planned auctions will average in the billions of dollars. We discuss the legal constraints on the use of these revenues and the Legislature's prerogative to determine the use of these revenues through its appropriation authority.

Recommendations to Change Design and Operation of Cap–and–Trade. In this report, we identify some program design changes that would improve the cap–and–trade program, have relatively little downside from a policy standpoint, and would be consistent with the overall goals set forth in AB 32. Thus, if the Legislature determines that it wishes to proceed with a cap–and–trade program, we would recommend that the Legislature seriously consider the following modifications to ARB's design of the program: (1) make producers of offset credits liable for offset project failures, (2) eliminate holding limits to improve the way the carbon market functions, and (3) reduce uncertainty about how and if the cap–and–trade program would operate after 2020.

Potential Alternatives to Cap–and–Trade. If the Legislature decided not to proceed with the cap–and–trade program, it would need to look at alternatives for achieving the state's goals under AB 32. We find that there are two main alternatives for achieving the GHG emissions reductions assumed in ARB's cap–and–trade program: making changes or additions to direct command–and–control regulations that apply to GHG emitters and the imposition of some form of carbon tax.

Introduction

As part of a larger, legislatively mandated effort to reduce emissions of GHGs, the ARB recently adopted regulations to establish a new program, known widely as cap–and–trade, that relies on market–based mechanisms to help reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels in California. Cap–and–trade constitutes one of the most wide–ranging and complex regulatory efforts in the history of the state. As we will discuss in this report, the particular design of the program chosen by the ARB involves a number of important policy choices that have broad environmental, fiscal, and economic policy implications.

Given the importance of the policy issues involved and what are likely to be the deep and long–lasting effects of this new regulatory scheme, this report examines in detail the specific policy choices made by the ARB in the design of the program, some specific policy trade–offs inherent in those decisions, and alternative policies the Legislature may wish to consider before implementation of the cap–and–trade program. In our view, there is still an opportunity for the Legislature to weigh in on these important decisions.

Methodology. In preparing this report, we reviewed the ARB rulemaking documents for its cap–and–trade regulation, related analyses (including public comments on the rules), and the academic literature on market mechanisms. We communicated with staff of the ARB; the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC); the Office of Legislative Counsel; the South Coast Air Quality Management District (which operates an air quality–related market trading program); federal regulatory bodies, including the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodities and Futures Trading Commission; the Congressional Budget Office; and staff of market–based climate change initiatives, including the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and the Western Climate Initiative (WCI). We also communicated with various academics, industry associations, and financial market trading participants.

Background

Global Warming and GHGs

Greenhouse gases are gases that trap heat from the sun within the earth's atmosphere, thereby increasing the earth's temperature. Both natural phenomena (mainly the evaporation of water) and human activities (principally burning fossil fuels) produce GHGs. Scientific experts have voiced concerns that higher concentrations of GHGs resulting from human activities are increasing global temperatures, and that such global temperature rises will eventually cause significant problems. Global temperature increases are commonly referred to as global warming or climate change.

California's Climate Change Goals

The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, referred to as AB 32, established the goal of reducing GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Among various other requirements, the legislation directed ARB to develop a plan by January 1, 2009, which encompasses a set of measures that, taken together, would enable the state to achieve its 2020 GHG reduction target. Commonly referred to as the AB 32 Scoping Plan, it is required by law to meet a complex, and at times competing, set of requirements. The plan is to minimize costs and maximize benefits for California's economy, improve and modernize California's energy infrastructure and maintain electric system reliability, maximize additional environmental benefits, and complement the state's efforts to improve air quality. The law also requires that regulations developed pursuant to AB 32 minimize so–called emissions "leakage"—increases in emissions of GHGs outside of the state that result from efforts to reduce emissions of GHGs within the state—and not disproportionately impact low–income communities in California. A final Scoping Plan was approved by the ARB in December 2008.

AB 32 Authorizes Use of Market–Based Compliance Mechanisms

Traditionally, California has relied upon direct regulatory measures to achieve emissions reductions and meet other environmental goals. Such regulations, commonly referred to as command–and–control measures, typically require specific actions on the part of emissions sources to achieve the desired emissions reductions or other goals. For example, a direct regulatory measure may require that a building meet a specified energy efficiency performance standard as a means to reduce emissions. In contrast, market–based mechanisms provide economic incentives to achieve emissions reductions, without specifying how emissions sources are to achieve those reductions.

In addition to a traditional regulatory approach, AB 32 also authorizes, but does not require, the ARB to include market–based compliance mechanisms as part of its portfolio of measures to meet AB 32 goals. Assembly Bill 32 defines a market–based compliance mechanism as a system that includes an annually declining limit on GHG emissions as well as a trading component whereby sources of GHG emissions may buy and sell carbon allowances in order to comply with the regulation. In adopting any market–based compliance mechanism, the ARB must consider the potential local impacts on communities that are already adversely impacted by air pollution. The ARB is required to design the market–based mechanisms to prevent any increase in emission of toxic air contaminants or other air pollutants as well as to maximize environmental and economic benefits of such an approach for California.

Two Types of GHG–Related Market Based Mechanisms

Two types of GHG market–based mechanisms are commonly discussed in academic literature: a carbon tax and a cap–and–trade program. While AB 32 only authorizes the use of a cap–and–trade program, both of these types of market–based mechanisms have been used in other jurisdictions to achieve GHG emissions reductions. Below, we briefly define the two types of market mechanisms, explain the economic theory behind them, and compare the theoretical benefits and costs of these two mechanisms with each other and with command–and–control programs.

Carbon Tax. A carbon tax amounts to a tax on each ton of carbon dioxide emitted, thereby placing a new cost on emitting GHGs. Under a tax, the regulator does not directly limit the amount of emissions that any emissions source may emit. Rather, the regulator would set the tax schedule such that, overall, the resulting amount of emissions would not be expected to exceed targets. Thus, an emissions source would generally experience greater costs, as a result of the tax, the greater its emissions. Those sources that can reduce emissions will presumably do so as long as the cost of making such reductions is less than the cost of paying the tax on those emissions. If that is not the case, they would pay the tax. The overall level of emissions reductions can be achieved, in theory, at the least cost possible because the tax provides an economic incentive to all emissions sources subject to the tax to find the mix of emissions reductions and tax payments that minimizes their costs.

Cap–and–Trade. The second common type of market–based mechanism that has been used to reduce emissions is a cap–and–trade program. As with a carbon tax, a cap–and–trade program does not directly require an individual emissions source to reduce its emissions. However, under a cap–and–trade program, the regulator issues one "allowance" for each ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions permissible within the regulated area. An emissions source regulated under the program must possess an allowance (or equivalent thereof) for each ton of CO2e emissions it produces in order to comply with the regulation. Because the amount of allowances issued is less than the amount of emissions that would otherwise be produced, the effect of the program is to lower overall emissions.

A cap–and–trade program differs from a carbon tax in that the cost of emitting each ton of CO2e is not decided by the regulator. Rather, the cost is determined, in effect, by the emissions sources themselves through trading of emissions allowances. The supply and demand of allowances in a trading market determine the price of an allowance. Parties that can reduce their emissions are likely to do so as long as it is cheaper than buying allowances at current prices. (When emissions reductions result in a party holding more allowances than it needs for compliance, excess allowances can be traded with others who find it less costly to buy allowances rather than reduce their emissions.) As with the carbon tax, the level of overall emissions reductions is achieved, in theory, at the least cost possible. This is because the allowance price provides an economic incentive to all regulated emissions sources to find the mix of emissions reductions and allowance purchases that minimize their costs.

Each Approach Inherently Has Its Advantages and Disadvantages. There are major differences between a carbon tax and a cap–and–trade program regarding (1) the level of certainty provided to regulated emissions sources about the cost of compliance and (2) the level of certainty for the regulator that the planned reduction in GHG emissions will actually be achieved.

A carbon tax provides relative certainty about the cost of compliance because the per–ton cost of emitting CO2e gases is, by definition, the dollar amount of the per–ton emissions tax. However, there is less certainty with the imposition of a carbon tax about the quantity of emissions reductions that will result. Should regulators set the emissions tax too low, emissions may exceed regulatory targets. If regulators set the emissions tax too high, then regulated emissions sources may act to reduce emissions beyond what is required to meet the targets.

In contrast to a carbon tax, a cap–and–trade program provides relative certainty to the regulator about the reduction in GHG emissions that will be achieved. By definition, the total number of tons of CO2e emitted by regulated sources cannot exceed the amount of emissions allowances issued by the regulator. However, because the price of an allowance is determined by market forces, the cost of compliance for an emitter is less certain under a cap–and–trade program.

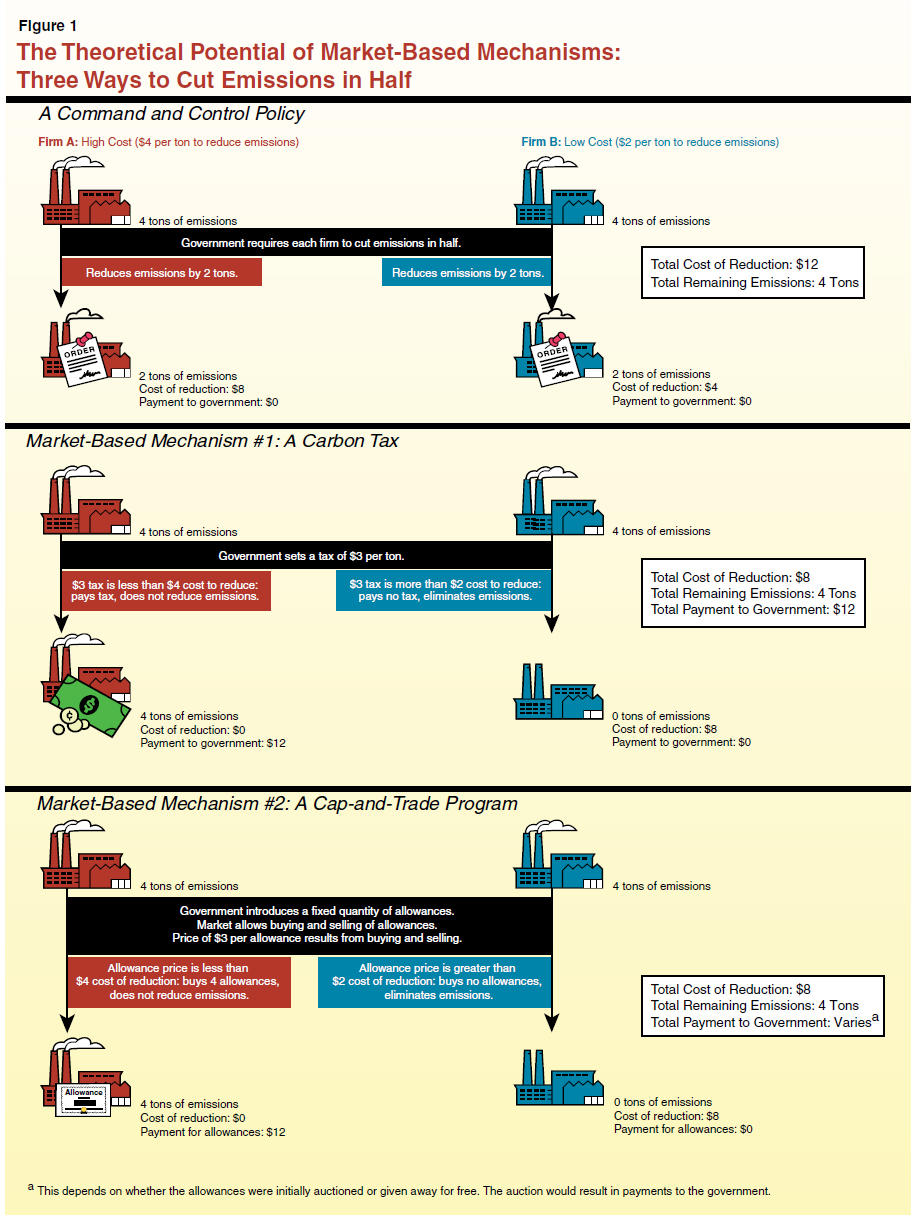

Command–and–Control Measures Usually Less Cost–Effective Than Market Mechanisms. Economic theory indicates that either a carbon tax or a cap–and–trade approach has lower compliance costs for emitters collectively than direct regulatory measures. Figure 1 provides a graphic illustration of the theoretical potential of a carbon tax and a cap–and–trade program to achieve the same emissions reduction at potentially lower total cost than a command–and–control program. The potential for lower total compliance costs under market mechanisms stems from the fact that the regulated emissions sources can be expected in many cases to have better information about which compliance strategies minimize costs for them than even the best–informed regulator could. Emissions sources facing relatively high costs to reduce emissions can potentially minimize their costs by choosing not to reduce their emissions, instead deciding to buy allowances (under cap–and–trade) or pay the tax (under the carbon tax). On the other hand, emissions sources that can reduce their emissions relatively cheaply are given an economic incentive to do so, as an alternative to buying allowances or paying the tax.

The Cap–and–Trade Program as Designed by ARB

ARB's Scoping Plan Includes a Cap–and–Trade Program

As AB 32 did not authorize a carbon tax, ARB included a cap–and–trade program in the AB 32 Scoping Plan as a market–based compliance mechanism. This is in addition to various direct regulatory measures referenced in the Scoping Plan, such as regulations reducing the carbon content of fuels sold in California or requiring generators to increase the amount of the electricity supplies they receive from renewable sources to 33 percent of their total. As a package, the Scoping Plan measures are intended to collectively lower the state's GHG levels in 2020 from what they otherwise would be (often referred to as the "business–as–usual" scenario) to the 1990 level. The ARB has estimated the 1990 level to be 427 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (MMTCO2e). This number is therefore the 2020 emissions limit—an aggregate statewide limit. The difference between the estimate of 2020 business–as–usual emissions and the 2020 emissions limit is therefore the emissions reduction target of the Scoping Plan. In the 2008 Scoping Plan, the total emissions reduction target was 174 MMTCO2e. In 2010, the ARB adjusted this number downward to 80 MMTCO2e, in part to account for the economic downturn's impact on emissions levels. Similar downward adjustments were made to the emissions reductions estimated for each of the Scoping Plan measures.

Below, we discuss the major features of the cap–and–trade program as designed by ARB and how the program is intended to work.

The Concept of the Cap

Cap–and–Trade Places Emissions Cap on Certain Sectors of the Economy. The ARB's cap–and–trade program is designed to limit or cap the aggregate amount of GHGs emitted from emissions sources that collectively represent roughly 80 percent of the state's total GHG emissions. While they are not assigned an individual emissions reduction target, entities that emit at least 25,000 metric tons or more of CO2e per year are subject to the cap–and–trade regulation and are therefore considered to be a "covered" entity. When the program is fully operational, approximately 350 of the state's largest emission sources will be covered entities, including oil producers, refiners, and electricity generators, as well as other large industrial entities. Covered entities and their customers within California are collectively referred to as "capped sectors" or "the capped economy." The remaining 20 percent of GHG emissions come from entities in other economic sectors such as agriculture and forestry. These sectors are referred to as the uncapped sectors and are not subject to the cap–and–trade regulation.

As noted earlier, the overall goal of AB 32 is to reduce GHG emissions from both the capped and uncapped sectors by 2020 to the 1990 level of 427 MMTCO2e. As the capped sectors emit 80 percent of the state's GHG emissions, ARB intends these sectors to reduce their GHG emissions to around 340 MMTCO2e by 2020 in order to meet the AB 32 emissions target. As discussed further below, the cap on the aggregate emissions of covered entities is designed to decline over time to result in the planned level of aggregate emissions from the capped economy in 2020 to meet AB 32's emissions target.

High–Level Overview of Compliance With the Cap

As a step toward enforcing compliance with the cap–and–trade program, the ARB will require covered entities to report their GHG emissions annually based on mandatory reporting requirements. Covered entities within the capped sectors can comply with the regulation by obtaining one allowance for each ton of CO2e that it emits during a particular compliance period. The covered entity must turn in allowances to ARB that match the level of its reported emissions for the compliance period. The first opportunity to obtain allowances will either be through ARB's free allocation or through ARB's allowance auction. After the initial auction, covered entities will have the opportunity to obtain allowances in the carbon market (discussed in more detail later). In addition, covered entities will be allowed to use a relatively small portion of offset credits—which are derived from GHG emission reduction projects that are undertaken by emissions sources not subject to the cap–and–trade program's GHG emissions cap—to comply with the regulation. (Collectively, allowances and offset credits are referred to as compliance instruments.) The ARB intends to phase in the sectors of the economy that are covered under the cap–and–trade regulation and ultimately reduce emissions by reducing the annual supply of new allowances over the course of the program.

Allocation of Allowances and Use of Compliance Instruments

Some Allowances Auctioned, Some Given Away for Free. An essential component of the cap–and–trade program design is deciding how to place allowances into circulation so they can be acquired by those who will need to use them for compliance. Generally speaking, allowances could be allocated in one of three ways: (1) they could be given away for free, (2) they could be auctioned, or (3) some portion could be freely allocated while the other portion is auctioned. All of these approaches yield the same programmatic results in terms of GHG reductions.

The ARB intends to do a combination of auction and free allocation of allowances. Initially, a majority of allowances will be allocated for free. Between now and 2020, the ARB estimates that it will give away approximately 430 million allowances (each allowance is for one ton of CO2e) to some industrial sources in order to reduce the competitive disadvantage to those sectors that are subject to the cap–and–trade regulation. The intent is to reduce what is called economic leakage—the decision by firms to relocate outside of California as the result of a perceived competitive disadvantage imposed by the cap–and–trade policy. In addition, the ARB will provide electricity distribution utilities free allowances to reduce the cost burden on electricity users from electricity price increases expected to result from the implementation of the cap–and–trade program. Also, while no estimates have yet been provided, the ARB has indicated that there will be some consideration given to providing free allowances to the natural gas distribution sector once these entities are phased into the program in 2015.

In total, between 2012 and 2020, the ARB will make available up to 2.5 billion allowances, with roughly 50 percent auctioned and 50 percent given away for free. The amount of allowances that ARB puts into circulation is controlled by ARB over time to move the state towards AB 32's 2020 emissions target. Please see the nearby box for ARB's plans for auctions and allowance allocations in 2012–13.

The Air Resources Board's (ARB's) Auction and Allowance Allocation Plans for 2012–13

2012–13 Allowance Auctions. The ARB intends to hold quarterly auctions of a set number of allowances beginning in 2012. In August of this year, it plans to auction 20 million allowances for use in 2015 or beyond ("vintage 2015" allowances). A similar auction will be held in November in which 20 million vintage 2015 allowances will be made available. By auctioning these future–year allowances, ARB intends to provide greater transparency to the market regarding potential future prices in order to provide covered entities more information to use in planning for future compliance with the regulation. In February 2013, ARB plans to auction 3 million current–year allowances as well as an additional 10 million vintage 2016 allowances. In May 2013, ARB plans to hold a similar auction where another 3 million current–year allowances as well as an additional 10 million vintage 2016 allowances will be offered.

2012–13 Free Allowance Allocation. In 2012–13, ARB plans to allocate approximately 150 million free allowances to some sectors of the economy, including electric utilities and some large industrial emitters, in part to minimize leakage. Specifically in 2012–13, electricity distribution utilities will receive almost 100 million allowances. Of this number, 65 million allowances will be given to the state's Investor Owned Utilities, which must then sell their allowances at auction.

Determination of Free Allowance Allocation to Leakage–Prone Industries. As mentioned above, the ARB has chosen to allocate allowances for free to some covered entities to reduce a competitive disadvantage to them potentially resulting from the cap–and–trade program. In order to determine which industries may be competitively disadvantaged as a result of the cap–and–trade program and therefore may be at risk of leakage, the ARB evaluated covered entities' degree of reliance on energy in the production or distribution of their products as well as their exposure to out–of–state competition. It then classified covered entities as either high, medium, or low risk of leakage. According to the ARB, the sectors that it determined are at high risk of competitive disadvantage include oil and gas extraction, cardboard manufacturing, and the manufacturing of certain chemicals such as fertilizers. Medium–risk sectors include food processing, sawmills, and petroleum product manufacturing. Low–risk sectors include pharmaceutical, medicine, and aircraft manufacturing. The provision of free allowances will continue longer, and at higher levels, for entities in sectors determined to be at higher risk. The allocation of free allowances is also based on an entity's prior output. Within those sectors that receive free allowances, the more of a product, such as cement, that an entity produces, the more allowances it will generally get for free. The ARB has committed to adjust its free allocation policies based on its ongoing judgments about such issues as the acceptable impacts of the cap–and–trade program on business competitiveness.

Offset Credits Can Be Used in Lieu of Emissions Reductions. The ARB's cap–and–trade regulation allows the use of offset credits as a means to comply with the cap on emissions. Offsets refer to GHG emissions reductions from projects that are undertaken by emissions sources not subject to the cap–and–trade program's GHG emissions cap. These projects are developed in lieu of direct emissions reductions by sources subject to the cap. For example, the owners of a power plant with emissions covered by the cap–and–trade program may pay a dairy (which is not otherwise regulated) to reduce its emission of GHGs. Under the ARB's offset program, the owners of the power plant would be credited for the GHG emissions reductions realized by the dairy. The power plant owners would, in effect, pay for the dairy to offset its emissions if that would be cheaper than reducing their own GHG emissions. Thus, the use of offset credits allows parties subject to the cap–and–trade program to lower their cost to comply with the regulation.

The ARB's rules currently allow for offset projects in four areas: forestry, urban forestry, dairy methane digesters, and prevention of the release of ozone–depleting substances (such as refrigerants) into the atmosphere. The cap–and–trade regulation allows for offset projects anywhere in the United States. However, the ARB's regulation allows no more than 8 percent of a covered entity's compliance obligation within each compliance period to be met with offset credits. (The remainder must be met with allowances.)

Compliance Instruments Can Be "Banked" for Later Use. The ARB allows some banking—the carryover of compliance instruments from one compliance period to any future compliance period—as part of its cap–and–trade program. The ability to bank compliance instruments may limit volatility in compliance instrument prices. If an unexpected shortage in compliance instruments caused prices to spike, parties that had banked these instruments would have a strong incentive to sell the ones they had set aside, putting downward pressure on prices. Banking also potentially provides an incentive for covered entities to make early reductions in their GHG emissions. Firms that believe that compliance instruments will become more valuable in the future will be more likely to invest in making emissions reductions today, thereby freeing up compliance instruments it could sell to others down the line.

Banking and the use of banked compliance instruments thus give entities important flexibility regarding the speed at which they reduce their emissions. Banking is limited to some degree, however, by ARB's limit on the number of allowances that any one entity can hold for trading purposes, as discussed later in this report.

ARB's Plan Includes Phased–In Approach With Gradually Declining Cap

The ARB will use a phased–in approach to its cap–and–trade program in which there will be three distinct compliance periods between now and 2020. The three compliance periods will encompass 2013–14, 2015–17, and 2018–20, respectively.

In the first compliance period, only electricity generators and large industrial sources will be subject to the cap–and–trade program. Beginning with the second compliance period, fuel suppliers will be added to the entities that are subject to the regulation. As shown in Figure 2 (see next page), from 2015 (when the cap–and–trade program is fully phased in) to 2020, the amount of aggregate annual emissions allowed from covered entities (the cap) gradually declines from just over 400 million tons to 341 tons. As the cap declines, allowances are likely to become more scarce which, in turn, will likely increase the cost of allowances.

Figure 2

Annual "Caps" on Emissions of Capped Economy (in MMTCO2e)

|

|

|

Approximate Annual Capa

|

Forecast BAU Emissions From Capped Economy

|

Cap as Percentage of BAU Emissions

|

|

|

2015

|

407

|

407

|

100%

|

|

Compliance Period 2b

|

2016

|

398

|

407

|

98

|

|

|

2017

|

386

|

408

|

95

|

|

|

2018

|

363

|

408

|

89

|

|

Compliance Period 3

|

2019

|

352

|

408

|

86

|

|

|

2020

|

341

|

409

|

83

|

Cap–and–Trade Serves as a Backstop for GHG Emission Levels

In Figure 3, we show how the mix of measures in the Scoping Plan—including both direct regulatory measures and cap–and–trade—are intended to achieve the aggregate emission reduction target by 2020. At full implementation of the Scoping Plan, cap–and–trade is now expected to contribute the equivalent of 18 MMTCO2e in reductions in GHG emissions annually by 2020 compared with 62 MMTCO2e from direct regulatory measures. As the figure shows, the sectors covered under the cap–and–trade program (referred to in the figure as the capped economy) are also subject to various direct regulatory measures.

Figure 3

Scoping Plan Forecast of GHG Emissions (in MMTCO2e)

|

|

Emissions in 2020

|

|

Planned Reductions in Emissions in 2020

|

|

Business–As–Usual Scenario

|

AB 32 Target (1990 Emission Levels)

|

|

Totals

|

Direct Regulatory Measuresa

|

Cap–and–Tradeb

|

|

Capped Economy

|

409

|

341

|

|

68

|

50

|

18

|

|

Uncapped Economy

|

98

|

86

|

|

12

|

12

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

507

|

427

|

|

80

|

62

|

18

|

The actual emissions reductions achieved under the cap–and–trade program, however, could be significantly different than shown in this figure. That is because the ARB has designed the cap–and–trade program to serve as a "backstop" to achieve GHG emissions targets in the covered sectors. Any underperformance of direct regulatory measures at reducing emissions in effect will result in additional reductions under the cap–and–trade program. In other words, the cap of the cap–and–trade program serves as a backstop for GHG emissions, regardless of the performance of the direct regulatory measures in achieving their estimated emissions reductions.

For example, in the electricity sector, electricity consumption and GHG emissions are supposed to be reduced through the implementation of the energy efficiency programs included in the Scoping Plan. If, however, these programs fail to meet their planned emissions targets, electricity generators or importers would have to either take additional steps to reduce their emissions or purchase additional compliance instruments to meet their cap–and–trade compliance obligations.

If in the future it appeared that the number of allowances ARB plans to introduce into the carbon market would likely allow emissions in 2020 to exceed the AB 32 target, ARB would have to take corrective actions to ensure the target will be met. For example, the size of allowance auctions or giveaways in future years could be reduced.

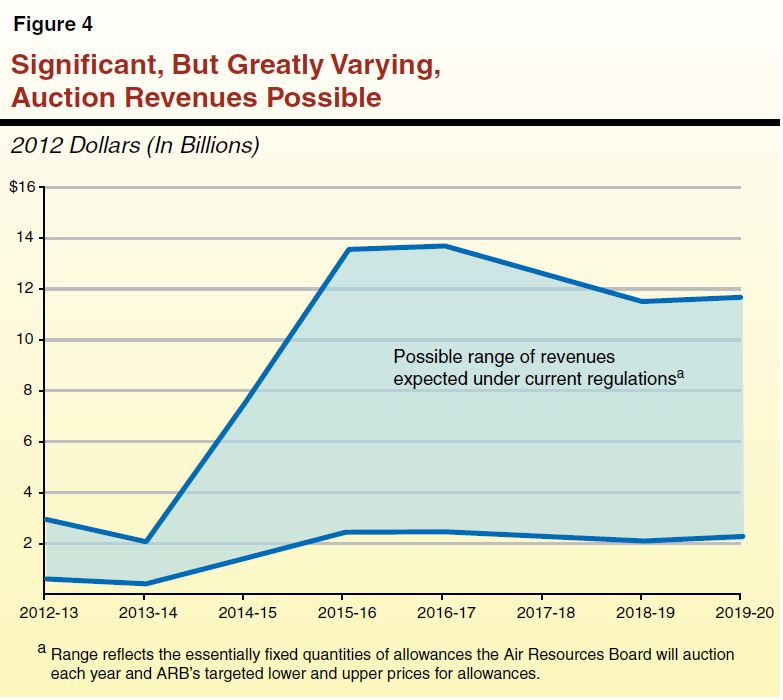

Auction Revenues

Billions of dollars in revenues from the auction of allowances will become available as a result of the ARB's cap–and–trade program. The amount of revenues could range greatly, as shown in Figure 4, depending upon the cost of directly reducing GHG emissions, the state of the economy overall, and other factors. The range of revenues shown in the figure is based on ARB's plan to auction a certain portion of allowances rather than giving them away for free, as well as ARB's targeted price range for allowances. In 2012 and 2013, the ARB targets a price range between $10 and $50 per allowance. These price targets are adjusted upwards over time.

The 2012–13 Governor's Budget assumes that cap–and–trade auctions will generate $1 billion in state revenues in 2012–13. Under the administration's plan, these revenues would be invested in (1) clean and efficient energy, (2) low–carbon transportation, (3) natural resource protection, and (4) sustainable infrastructure development. The budget also assumes that $500 million of the revenues will be used to offset General Fund costs of existing programs. According to the administration, since actual cap–and–trade revenues will not be known until late in 2012–13, the planned expenditures are not specified by program in the proposed budget. Rather, the administration plans to submit an expenditure plan to the Legislature after the first cap–and–trade auction—which would be after the 2012–13 budget is enacted—and allocate funds to specific programs not sooner than 30 days after submitting this plan.

Linkage With Other Jurisdictions' Cap–and–Trade Systems

In developing the cap–and–trade regulation, ARB indicated that it plans to link with other cap–and–trade programs, namely those in the WCI Inc.—a consortium of Western states, Canadian provinces, and Mexican states. Linkage would mean that compliance instruments certified or issued by any linked jurisdiction would be accepted for compliance purposes by all linked jurisdictions. While many of the members of WCI Inc. have either postponed or are further behind the regulatory development process, Quebec is one member of WCI that is on track to link with California prior to the first auction, which is scheduled for August 2012. Linking with other jurisdictions' cap–and–trade programs could serve to contain aggregate program compliance costs by providing more opportunities for low–cost emission reductions. It does, however, potentially raise both legal and economic questions.

First, in order to formally link with another jurisdiction, ARB must first go through the formal rulemaking process on a jurisdiction–by–jurisdiction basis. Under state law, such rulemaking is subject to public hearing and notice requirements as well as requirements for an economic impact analysis. While it has not officially filed a notice of proposed rulemaking to link with Quebec, ARB has indicated that it intends to open such a proceeding in the spring of 2012. Legal questions have been raised regarding California's ability to legally enter into a compact or agreement with the province of another country.

Second, in order to effectively link California's cap–and–trade program with another jurisdiction's program, California's cap–and–trade rules should be harmonized with the rules of the other jurisdiction, ensuring that covered entities in both jurisdictions are subject to equally stringent rules for compliance. In an unharmonized world, regulated entities would pick and choose whichever jurisdiction's rules best serves their economic interests, even if this goes against the design decisions and policy priorities of their "home state." Without such harmonization, unintended adverse impacts, economic or otherwise, may result. For example, if California's and Quebec's offset protocols are not harmonized, the ability of offsets to serve as a cost–containment mechanism for the program may be diluted and emission reductions from offset projects may be less certain. As another example, to the extent that Quebec's cap on its covered entities is more stringent than California's, this may increase the scarcity of allowances, which would serve to increase overall allowance prices for all covered entities and potentially increase the compliance cost for California's covered entities.

Legislative Oversight of ARB's Linkage Plans Will Be Important. To the extent that linking would expand the market and provide a greater number of opportunities for low–cost emissions reductions, harmonizing and linking with other jurisdictions' cap–and–trade programs could serve to contain overall compliance costs. However, we will not know how well programs proposed to be linked are harmonized nor will we have a clear understanding of the potential economic and other impacts of such action until an analysis has been conducted of the board's particular proposals to link California with cap–and–trade programs in other jurisdictions.

As ARB must include an economic impact analysis in its initial statement of reasons for any formal rulemaking on linking, the Legislature will have an opportunity to evaluate such analysis, determine if linking with another jurisdiction is indeed in the state's best interest, and provide any necessary policy direction to ARB on this issue.

Cap–and–Trade Program to Give Rise to Multiple Carbon Markets

The introduction of emission allowances and offset credits that are designed to be tradable gives rise to what is known as a carbon market. The carbon market will consist of a number of distinct but interrelated markets. The ARB's allocation or auction of emission allowances, as well as the ARB's development and certification of offset credits, will take place in what is commonly referred to as the "primary market." There are also so–called "trading markets" where trading activity related to compliance instruments will take place. These include the secondary market (where compliance instruments are traded directly) and the derivatives market (which involves the trading of financial contracts, primarily for hedging and investment, the value of which depends on the market behavior of compliance instruments).

The ARB has set rules regarding who may participate in auctions and in the trading markets, with the exception of the derivatives market. (The ARB is of the view that it lacks the authority to govern participation in the derivatives market.) As noted earlier, market participation is not limited to covered entities. Non–covered entities and other interested parties are generally permitted to participate as well. Some parties may participate in order to reduce the level of allowable emissions by buying compliance instruments and making them unavailable for use. Only entities with a potential conflict of interest, such as third–party verifiers (entities and individuals who are responsible for auditing and verifying emissions reductions), are not allowed to participate in the market. In order to participate, all interested parties must be registered with ARB.

While ARB has set rules governing market participation, it will not directly operate the trading markets. Rather, these trades will take place through privately operated exchanges or in "over–the–counter" trading directly between parties. The ARB will, however, require that information on a trade in these markets be reported to it for input into a tracking system before the trade can be completed. And, while ARB will share an oversight role, the bulk of the oversight responsibility will fall to third parties with whom ARB will contract. We discuss this approach to oversight in more detail later in this report.

The carbon market will play a pivotal role in the cap–and–trade program. As previously noted, one advantage of a market mechanism is its potential to reduce emissions at a lower cost than a traditional regulatory approach. However, in order to facilitate lower economy–wide compliance costs, the carbon market must function well. A well–functioning carbon market is one that allows for broad participation and allows participants to easily buy and sell compliance instruments at sufficiently predictable prices that accurately reflect costs of abatement in the capped economy. As we will discuss later, to help its carbon market function well, the ARB has established rules and processes to help prevent abuse and to allow the punishment of fraudulent activity. These rules and processes include efforts to establish clear legal jurisdiction over market participants, ban entities with market oversight or offset verification roles from trading, and punish entities that violate market rules in various ways.

Key Trade–offs Inherent in Designing a Cap–and–Trade Program

The ARB Made Reasonable Choices . . . As we noted earlier, AB 32 establishes a number of different and potentially competing requirements. In addition to the main purpose of reducing GHG emissions, the plan must take into account impacts on local air quality, impacts on state revenues, cost impacts on regulated parties, and impacts on the overall state economy. The specific design of a cap–and–trade program thus inherently involves making a number of key policy choices. For virtually every feature of its plan, the ARB had to weigh the perceived policy benefits of a particular approach in light of the potential trade–offs of pursuing its chosen course of action.

There is no way to know for sure exactly how the ARB's program and its related carbon markets will ultimately work out because of its complexity and scale. Our analysis indicates that, for the most part, the ARB has made a reasonable effort to balance these various policy trade–offs in the particular design of the cap–and–trade program it has adopted in its regulations. Based on our economic and policy analysis of the ARB's package, for example, we believe the cap–and–trade program would likely function fairly effectively in terms of achieving the targeted level of GHG emissions reductions required under AB 32.

. . . But Alternative Choices Are Possible. Our analysis further suggests, however, that the reductions in GHG emissions contemplated by the ARB would probably not be achieved as efficiently, from an economic perspective, as might be possible with a different design involving different policy choices. A number of the features of the ARB's plan involve significant policy trade–offs that warrant policy review and discussion by the Legislature. In this section, we discuss a number of policy choices and trade–offs made by the ARB in its cap–and–trade plan involving: efforts to prevent leakage, the use of auction revenues, the use of offset credits, actions to reduce volatility in the price of allowances and offset credits, auction and market oversight, and enforcement of cap–and–trade requirements.

There is no one right way to design a cap–and–trade program. The Legislature could, however, modify some features of the ARB's cap–and–trade program before compliance is required to reflect a different set of policy choices among the competing and conflicting goals inherent in AB 32.

Trade–Offs Involving Efforts to Reduce Leakage

Potential for Leakage

California Policies Can Increase Economic Activity—and Emissions—Outside California. While any form of California climate policy could directly reduce California emissions, it could also unintentionally increase emissions outside of California. Such increases are referred to as emissions leakage. For example, under cap–and–trade, the new costs of reducing emissions and the new costs of covering any remaining emissions with compliance instruments could put businesses in California at a competitive disadvantage relative to businesses in places without analogous costs. If a California firm reduced its activities due to these costs, out–of–state competitors might increase their activities to serve the California market, with the possible result that their emissions would increase. Alternatively, a California business might relocate outside of California due to competitive pressures, again increasing out–of–state GHG emissions.

There is another type of emissions leakage commonly referred to as reshuffling. A utility within California that imports electricity or fuel might switch to importing a less emissions–intensive product, such as renewable energy, to reduce its cap–and–trade obligations. However, this would free up "dirtier" resources or electrical generation capacity for purchase by utilities outside California. Thus, GHG emissions associated with those out–of–state markets might increase. For example, staff at CPUC estimate that importers of electricity into California could reduce their cap–and–trade obligations by up to 15 to 27 MMTCO2e in this way in 2013 without reducing aggregate GHG emissions. Thus, this type of leakage would lessen the efficacy of the cap–and–trade program in directly reducing global emissions.

Portion of Allowances to Be Given Away for Free to Reduce Leakage

Allowances to Be Given Away Will Reduce Costs of Covering Emissions. In its design of the cap–and–trade program, the ARB chose to reduce leakage risks to a certain degree by giving allowances away to certain sectors. The ARB's policy will essentially reduce the number of compliance instruments these sectors will need to purchase to cover the GHGs they emit. This will therefore reduce their compliance costs. With lower compliance costs, these sectors will experience fewer competitive disadvantages relative to businesses in places without analogous regulations. (If covered entities receive more allowances for free than they need, they will be able to sell excess allowances to other parties.)

We note that ARB will not be able to use giveaways to eliminate all compliance costs because the supply of allowances—the cap—shrinks over time.

To achieve its desired reduction in compliance costs, ARB estimates that, by 2020, it will have given away approximately 430 million allowances valued (in 2012 dollars) between about $4 billion and $24 billion. The broad range of allowance value given away for free reflects ARB's targeted range of prices for allowances, discussed below. The level of leakage risk that will remain with ARB's policies in place is unknown and would be challenging to quantify.

Trade–Offs. If ARB gave away more of the allowances for free than currently is planned, there would be three kinds of impacts, some positive and some negative. First, if the ARB gave more allowances away to sectors at risk of leakage, the resulting risks of leakage, and costs to covered entities receiving free allowances, would be lower. This would further reduce the competitive disadvantages those sectors face. Second, because the ARB's policy will essentially reduce the number of compliance instruments certain entities will need to purchase to cover the GHGs they emit, these entities would emit more than if they had to pay for the allowances. For example, it is possible that ARB's free allowances might allow an aging factory to continue to operate, emitting both GHGs and other types of pollutants that potentially degrade air quality. Third, if the ARB gave more allowances away, then fewer allowances would be available for other parties to buy at auction. This would lower allowance auction revenues and could affect the carbon market and other markets in the state. For example, parties that would have participated in auctions might have a harder time finding other parties to buy allowances from if auctions were smaller. This would make the carbon market less efficient and allowance prices potentially higher.

If, on the other hand, ARB gave away fewer of the allowances for free than currently is planned, there would the same kinds of impacts just mentioned, but in the opposite directions. First, the risks of leakage, and costs to covered entities, would be greater. Second, local air quality could be improved. Third, auction revenues would be higher and allowance prices might be somewhat lower because of improved market efficiency.

Trade–Offs From Directing the Use of Certain Auction Revenues

Cap–and–Trade Program Will Impact Electricity Users

Because the cap–and–trade program will in effect incorporate a carbon price into goods and services produced in the state, this will have the effect of making many things in the economy more expensive, including electricity. Under a cap–and–trade approach, allowing prices of more emissions–intensive goods and services to rise over time is intended to effectively motivate people and businesses to change their behavior in order to reduce GHG emissions.

Provision of Free Allowances to Electricity Distributors

Reducing Impacts on Electricity Users. The ARB and the CPUC have jointly agreed that ARB will allocate free allowances to electricity distributors (as opposed to generators), including both investor–owned utilities (IOUs) and publicly owned utilities, through 2020. The purpose of these free allocations is to reduce the cost burden on electricity users from electricity price increases expected to result from the implementation of the cap–and–trade program.

In the first year of the cap–and–trade program, the ARB plans to give electricity distributors allowances equivalent to almost 100 MMTCO2e. The amount will decline slightly after that. The allowances given to the IOUs will then be sold on their behalf by the ARB in its quarterly allowance auctions. We estimate the approximate revenues from the auction of these allowances on behalf of the utilities between now and 2020 will be from $8 billion to $41 billion (in 2012 dollars), depending on the prices of allowances auctioned. In March 2011, the CPUC began a formal process to decide on the appropriate use of these revenues by the IOUs. While the CPUC has not completed this proceeding, it has indicated that it expects that the majority of the proceeds will be used by the IOUs in ways intended to benefit their ratepayers—such as by increased investments in energy efficiency that would reduce energy consumption in the state and thus indirectly reduce the cost burden of the cap–and–trade program on California electricity ratepayers.

Trade–Offs. As with the approach to reducing leakage, giving away allowances to electricity distributors would reduce the revenues that would otherwise potentially accrue to the state from auctions. While the planned uses of these revenues—for energy efficiency and renewable programs—may have merit, using the revenues for these purposes comes at the cost of not making them available for other state purposes that may better align with legislative priorities.

Trade–Offs Related to the Use of Offset Credits

Allowing Use of Offset Credits to Reduce Compliance Costs

As discussed earlier, while the cap–and–trade program focuses on reducing the emissions of the capped economy, the ARB would allow certain emissions reductions from offset projects anywhere in the United States to count toward compliance with the cap–and–trade program. Accepting offset credits for compliance is a way to allow parties in the "uncapped economy" to help meet emissions reduction goals.

Accepting offset credits for compliance is also a way to reduce the costs to the state economy of reducing GHG emissions. The theory behind using offsets as a cost–containment mechanism is that, because entities in the uncapped economy may not have had relatively strong incentives to reduce emissions, relatively low–cost options to reduce emissions may exist there. In the capped economy, in contrast, years of regulation and rising energy prices have already forced entities to undertake many lower–cost options so additional abatement could be more expensive. To the degree that the cost of obtaining offset credits is less expensive than abatement within the capped economy, allowing the use of offset credits would reduce compliance costs and lead offset credit producers to make emissions reductions that covered entities would otherwise have to make.

Regulating the Quality of Offset Credits

Legislation Sets Standards Applicable to Offset Credits. Assembly Bill 32 sets a number of standards that must be met in order for emissions reductions from offset projects to be counted towards meeting the AB 32 goal of reducing GHG emissions. The standards are intended to ensure that the projects result in real and permanent reductions in GHG emissions (see nearby box). However, the strictness of the standards affects the cost of the offset projects and thus the quantity and price of offset credits available.

The ARB will rely on verifiers it will accredit to establish that offset projects meet the statutory criteria. Verifiers must demonstrate competence, assess and mitigate any conflicts of interest, and be subject to audits and strict performance evaluations. The ARB is relying on these private parties for this activity because its own staff does not currently have this expertise and because private verifiers are already carrying out similar functions.

Criteria for Offset Credits and Projects

Offset credits and projects must meet these emissions reductions criteria required by Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006 (AB 32, Núñez/Pavley):

- Real. Offset credits should result from demonstrable actions based on appropriate, accurate, and conservative methodologies. This should include accounting for leakage. For example, the accounting for emissions reductions from a carbon sequestration project by not harvesting timber somewhere in the United States should account for leakage, such as increased emissions due to timber harvests increasing elsewhere.

- Permanent. Emissions reductions from offset projects should not be reversible.

- Quantifiable. Emissions reductions from offset projects should be able to be accurately measured and calculated in a reliable and replicable manner.

- Verifiable. Emissions reductions from offset projects should be well–documented and lend themselves to an objective review by an accredited verifier.

- Enforceable. Some party should be able to be held liable by the Air Resources Board (ARB) in respect to an offset project, and ARB must be able to take appropriate action if the cap–and–trade regulation is violated.

- Additional to What Would Otherwise Occur. Offsets cannot be counted if the emissions reductions were already required or would otherwise have occurred on the natural.

Trade–Offs. There are policy trade–offs to consider with regard to ARB's specific approach to allowing offset projects to meet the GHG emissions cap. The most fundamental trade–off is that their intended benefit of lowering the cost of compliance comes at the cost of some loss of certainty about how much emissions will actually be reduced. This is because an offset credit's quality often cannot be proven definitively. The emissions of covered entities are relatively easier to verify as they are based on reported emissions that have already occurred. However, verifying that an offset credit is legitimate involves estimating how much GHG emissions are with the offset project and would have been without the offset project. If offset credit quality were low, offset projects would result in more emissions than expected.

Limitations on the Use of Offset Credits

8 Percent Limit on Use of Offset Credits. The cap–and–trade program designed by the ARB limits each covered entity's use of offset credits to at most 8 percent of its compliance obligations per compliance period. In other words, as an alternative to complying by having an emissions allowance for each ton of CO2e it emits or by reducing its emissions, the covered entity could use offset credits to cover up to 8 percent of its emissions.

Trade–Offs. To the extent that offset quality is high, the use of offset credits would help meet emissions reduction goals at lower aggregate program compliance costs and ultimately decrease the program's potential negative economic impact. On the other hand, because the use of offset credits presents some problems, there may be reasons to limit their use. First, the emissions reductions associated with offset credits can be uncertain and the offset projects themselves have the potential to fail. For example, a forest being used to sequester carbon could burn down. Restricting offset credit use therefore could limit the unexpected emissions from failed offset projects. Second, a limit on offset credit use could also benefit the environment and society in other ways. Restricting offset credit use would increase the emissions reductions required of covered entities collectively. Because emissions of GHGs are in some cases associated with the release of gases that harm public health, a limit on offset credit use could thus result in a greater improvement in air quality for communities living near covered entities than might otherwise be the case.

To the degree that offset credits are less expensive than direct abatement of GHG emissions by covered entities, allowing their use by covered entities would reduce compliance costs. The ARB's 8 percent limit thus constitutes a somewhat arbitrary limit on the use of offset credits in order to limit the emissions that could result from failed offset projects and to make it more likely that air quality near covered entities improves.

Trade–Offs Related to Actions to Reduce Compliance Instrument Price Volatility

Excessive Volatility in Prices Could Weaken Trading Program

In any market—but particularly in new, untested ones—price stability can be important to its proper functioning. Several factors could contribute to volatile prices in the cap–and–trade market. Prices could spike, for example, if compliance instruments became scarce relative to the demand for them. For example, scarcity could result from a surge in economic activity that increased emissions and therefore demand for compliance instruments. Likewise, prices could "crash" if emissions–producing sectors suffered from an economic downturn or if compliance instruments became plentiful relative to demand.

Excessive volatility in the prices of compliance instruments is a potential concern for the operation of the cap–and–trade program. If compliance instrument prices were particularly volatile, some carbon market participants would likely respond by trading less than they would in a more stable pricing environment. Reduced trading, in turn, would impede the ability of the cap–and–trade program to reduce overall compliance costs.

Mechanisms to Reduce Volatility

Allowance Reserves and Minimum Bid Requirements. The ARB has designed its cap–and–trade program to limit the volatility of compliance instrument prices. The ARB's plan to keep allowance prices from spiking too high is to sell a limited number of allowances from a reserve of allowances that it plans to establish. These allowances will be available to covered entities in case there is an unexpectedly short supply that could otherwise drive allowances prices up to high levels. The size of the reserve would be limited so that, even if the entire reserve were sold, the emissions reduction targets for cap–and–trade would still be met. (The reserve reflects the set–aside of 4 percent of total allowances.) The prices of these allowances are set at $40, $45, and $50 per ton of CO2e in 2013—with the least expensive allowances that are still available to be sold first. These prices will grow at 5 percent per year in addition to taking account further adjustments for inflation. These prices function as ceilings on compliance instrument prices because, so long as the ARB is selling allowances at these prices, market prices are unlikely to go higher. If the reserve were ever exhausted, however, the ARB's cap–and–trade regulations would not limit how high compliance prices could go.

The ARB's plan to keep prices from falling too low is to require a minimum bid amount in all of its allowance auctions. The minimum bid will be $10 per ton of CO2e in 2012 and 2013 and will then grow at 5 percent per year in real terms. This minimum bid will generally function as a floor on compliance instrument prices.

While both of these mechanisms apply only to the price of allowances, they are likely to also have an indirect effect on the prices of offset credits.

Trade–Offs. As discussed above, the market price of compliance instruments under a cap–and–trade program should ideally give each covered entity a signal regarding the degree to which it should reduce emissions before it turns to compliance instruments to meet its obligations to the ARB. A covered entity, for example, generally would abate more if its cost of doing so was below the market price of allowances and credits. To the degree that the ARB's mechanisms provide greater certainty regarding the appropriate level of direct abatement, these mechanisms will potentially reduce price volatility because covered entities and offset producers will have more information to determine the appropriate level of investment. As a result, covered entities will be able to plan better and the markets will generally function better in the long run.

The ARB's choice of the price ceiling and price floor, however, may have costs. It is possible that keeping prices artificially higher or lower than they would be otherwise will distort decisions about investments in abatement. Because of the targeted price floor, for example, a covered entity might abate more than it would in the absence of the price floor. This additional abatement would be unnecessarily expensive and could be more than would be needed to meet the 2020 emissions level target. Because of the targeted price ceilings, the developer of an abatement technology that would reduce emissions at a cost above the price ceilings might be unable to find investors. This failure to invest could limit the options available to reduce emissions and therefore increase compliance costs.

Trade–Offs Involving Auction and Market Oversight

The Potential for Gaming

Oversight of cap–and–trade auctions and trading markets is important because of the potential for "gaming"—manipulation through collusion or fraud. Such activities tend to distort market price signals with potentially significant consequences. If prices for allowances and offset credits were artificially high as a result of market manipulation, for example, covered entities would spend more on abatement than needed. If prices were artificially low, some lower–cost abatement strategies that would be effective in reducing GHG emissions might not be implemented because allowances and credits were less costly options. Gaming could also lower confidence in the carbon market, decrease its liquidity, and reduce the overall economic efficiency of the market. For example, if gaming were common or serious enough that market participants did not trust each other, it might be difficult for a buyer to find a potential seller of compliance instruments or for parties in a potential trading transaction to agree on a sales price, again potentially leading to covered entities making unnecessary and expensive investments in abatement.

Market Oversight Program Relies in Part on Private Third Parties

Oversight Provisions. The ARB's regulations include several components intended to address the potential gaming of its cap–and–trade program. The ARB is in the process of contracting with an independent market monitoring service to detect potential market manipulation as well as issuing a contract for the training of ARB staff market monitors. The ARB plans to assemble a "Market Surveillance Committee" composed of academics with expertise in market development and oversight. The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission and other regulators will also have important oversight roles. Recently, WCI—a nonprofit corporation—has been formed to provide administrative and technical services to support the implementation of GHG trading programs. Officials from California, Quebec, and British Columbia are on the initial board of directors. The WCI plans to conduct market monitoring of allowance auctions and market trading of compliance instruments.

Effective oversight of carbon markets will be important. However, it could also be a challenging and potentially expensive effort.

Limits on Holding Allowances

Basic Limit on Holding More Than 2.5 Percent of the Market. The ARB cap–and–trade program is designed in a way that imposes several limitations on participants in allowance auctions and in compliance instruments markets intended to prevent abuses. In particular, the ARB's regulations limit the number of allowances that participants can hold for buying and selling. These are known as holding limits or position limits. (Allowances held only to be surrendered for compliance will not be limited. Also, offset credits will not be subject to holding limits.) The basic holding limit is set at 2.5 percent of the number of allowances scheduled to be auctioned off or given away for free in that year, with various complex adjustments. Trades that would violate holding limits will not be allowed and could be reversed by ARB, which can impose penalties on violators.

Trade–Offs. Holding limits are a low–cost way—in theory—to limit market power, including the power to manipulate carbon market prices. For example, a market participant who wanted to drive prices up by holding some allowances out of circulation would be unable to do so if the holding limit were tight enough. That said, the potential effectiveness of holding limits at reducing manipulation depends on having sufficient oversight mechanisms in place to detect and penalize such conduct. Also, there are reasons to be wary of holding limits. If the limits were too restrictive, participants could be unable to hold or use desired amounts of compliance instruments for legitimate business purposes, potentially weakening the program in several important ways. Participants might need to find multiple buyers or sellers if they wanted to sell or buy many compliance instruments because any single party would be limited in what they could hold. Because participants could not buy—or hold and sell—as many compliance instruments as they may want, their abilities to "correct," through their trading transactions, for prices that they thought were too high or too low, including price changes due to price manipulation, would be limited. Also, the establishment of holding limits might prompt some participants to try to circumvent them, thus making market oversight more difficult. For example, an entity that wanted to circumvent holding limits could create an entity that registers as a separate market participant but that they actually control. If ARB did not know the controlling entity was linked to the new participant, ARB would not know to limit their joint holdings.

By their nature, holding limits are somewhat arbitrary and inflexible. Moreover, it is possible that the risk of carbon market manipulation may be overstated. Other types of markets involving the trading of commodities function well without holding limits. In summary, the cap–and–trade program designed by the ARB relies on holding limits to attempt to reduce various risks associated with detrimental market behavior at the potential cost of creating less efficient markets and higher overall compliance costs.

Trade–Offs Related to Enforcement Provisions

Lax Enforcement of Cap–and–Trade Rules Could Weaken Program

Under a cap–and–trade approach, it is possible that at least some entities would fail to surrender in a timely fashion sufficient compliance instruments to cover the emissions they reported for a period. This could be the result of intentional actions or could be inadvertent on the part of covered entities. In any event, ensuring compliance with these requirements is critical to the success of constraining GHG emissions under a cap–and–trade program. Failure to address such issues would undermine the goals of the program.

Penalties Faced by Entities Not Covering Their Reported Emissions

Quadruple Penalties for Noncompliance. Under the ARB cap–and–trade regulations, a covered entity would generally have to surrender four times more compliance instruments than will otherwise be required if it failed to comply with program deadlines. For example, if a covered entity had 100 tons of CO2e emissions but only surrendered compliance instruments covering 90 tons of emissions on time, as a penalty it would have to surrender compliance instruments covering 40 tons of emissions. If emissions were not subsequently covered by compliance instruments as required, the ARB regulations indicate that other penalties would be possible.

Trade–Offs. As noted above, establishing penalties for noncompliance is essential to the success of the cap–and–trade program. Excessive penalties for late compliance, however, could force covered entities to hold an excessive number of compliance instruments as insurance against emissions spikes or compliance instrument price spikes. Such increased holding could reduce market liquidity because it reduces the availability of allowances for trading purposes and thus might increase compliance costs. In summary, ARB's penalty structure for late compliance potentially comes at the cost of less efficient markets and increased compliance costs due to entities holding compliance instruments as insurance against future compliance instrument price increases.

Responses to Smaller Errors In Reported Emissions

No Corrective Actions Required for Smaller Errors. Under ARB's rules, underreported emissions of less than 5 percent of a firm's total in any year are allowed. In such cases, no corrective actions would be required and no penalties would be imposed.

Trade–Offs. By not penalizing small under–reportings of emissions, ARB's approach would save covered entities the costs of ensuring greater accuracy in their reporting. In some cases, this lack of accuracy could result in lower costs for compliance with the cap–and–trade program. On the other hand, the establishment of such a "safe harbor" for underreporting of emissions may prompt some covered entities to deliberately do so. This policy would therefore allow a given level of unaccounted–for emissions. In summary, the ARB's approach of allowing some underreporting of emissions without penalties will keep compliance costs lower for covered entities at the cost of some uncertainty about the amount of emissions reductions that would be achieved by the cap–and–trade program.

Responses to Offset Project Failures

Invalidation of Offset Credits Possible for Up to Eight Years. As discussed above, the actual reduction in emissions associated with each offset credit is uncertain. Under the cap–and–trade program, the ARB will be allowed to invalidate an offset credit up to eight years after its issuance. For example, offset credits would be subject to invalidation if the offset project violated a local, state, or federal regulation, or was being counted "twice" as an offset credit for another program. The ARB could in effect put a hold on offset credits while it investigates potential problems with their validity. While investigations occurred, those offset credits could not be used for trading. Final decisions to invalidate offset credits would be subject to appeal to the ARB's Executive Officer. Under some circumstances, if a party was found to have held or used the invalidated credit for compliance purposes, penalties could be avoided if the invalidated credit were replaced with a valid compliance instrument within 90 days of notification.

Trade–Offs. The ARB's policies of (1) prohibiting the trading of offset credits that are under investigation and (2) seizing invalidated offset credits from whomever holds them place the potential costs of failed offset projects on users of offset credits. In effect, they would bear the costs of invalidation rather than the producers of the projects or the ARB. This would provide users with a strong incentive to try to ensure that offset credits meet the criteria outlined earlier in this report.

Placing the potential costs of failed offset projects on users of offset credits, however, raises concerns because offset producers are in a better position to manage the risks of invalidation. For example, an offset credit producer should know if it sold two offset credits based on the same one–ton reduction in emissions. Moreover, the risk of invalidation of offset credits could make offset credits worth less in general than allowances. For example, an allowance might be worth $20 while an offset credit might trade at a discounted price of $15 because there would be a chance that it would be seized by ARB if invalidated. To reduce the risks associated with offset credit invalidation, parties entering into transactions involving offset credits might write more complex contracts, making carbon market transactions harder to understand and oversee. If the risks associated with offset credit invalidation were thought to be large enough, market participants might avoid using significant amounts of offset credits. The risks of invalidation could thus limit the potential for offset credits to reduce entities' compliance costs, which was the main reason for allowing offset credits in the first place.

In summary, ARB provides covered entities with strong incentives to try to ensure the validity of offset projects and their associated offset credits at the cost of making markets more complex, making the use of offset credits less attractive in the carbon market, and potentially increasing cap–and–trade compliance costs.

Changes or Alternatives to ARB's Cap–And–Trade Approach

In the preceding section, we discuss the policy choices and the associated policy trade–offs involved in the ARB's design of the cap–and–trade program. Because striking the right balance in addressing these trade–offs is so important to the success of a cap–and–trade program and the achievement of the overall goals set forth in AB 32, we believe that the Legislature should carefully examine at this time (1) whether the particular design choices that the ARB has made for the program are the best ones and (2) whether alternatives to establishing cap–and–trade should also be considered. In the first of the next two sections, we offer the Legislature options for changing the cap–and–trade program, such as to reduce overall compliance costs or to increase the certainty that GHG emissions levels will be reduced to targeted levels, that it may want to adopt depending on its priorities for AB 32 implementation. In the second of the following two sections, we discuss potential alternatives to the cap–and–trade program as a means to meet AB 32's goals. These alternatives include both traditional direct regulatory measures as well as the other type of market mechanism—the carbon tax.

A Larger Role for Cap–and–Trade in the Scoping Plan? The ARB has not evaluated the relative cost–effectiveness of each of the measures included in the Scoping Plan. Without such an evaluation, the state cannot be assured that the mix of measures, as well as the extent to which any one measure is used, results in the most cost–effective approach to reducing the state's GHG emissions. It is possible, for instance, that a larger role for cap–and–trade relative to the direct regulatory measures currently in the Scoping Plan could be a more cost–effective means of achieving the goals of AB 32. We recognize that many of the direct regulatory measures included in the Scoping Plan were developed to address other policy goals not directly associated with a reduction of GHG emissions. Therefore, their repeal to accommodate a larger role for cap–and–trade in the Scoping Plan could run counter to the Legislature's policy priorities. However, the Legislature may nevertheless want to balance these other policy goals against the potential to reduce the economic impact of AB 32 by expanding cap–and–trade's role.

Making Changes to the Design and Operation of Cap–and–Trade

In this section, we discuss potential alternatives to the cap–and–trade program's current design and potential uses for allowance auction revenues. The program design options discussed all relate to the policy choices made by ARB and their inherent trade–offs discussed above. The options are organized according to policy goals the Legislature may have, such as increasing certainty that the emissions target will be met. Most of these options would have to be considered in light of their own trade–offs. We conclude this section, however, with three options we recommend the Legislature adopt, as in our view these options have relatively little downside from a policy standpoint and would improve the program.

Changing the Overall Level of Revenues That Would Be Raised

The cap–and–trade program designed by the ARB will create allowances, with some being auctioned for sale and others given away for free. If more allowances were given away for free to covered entities, this would reduce the overall economic burden the program is likely to have on the state's economy. On the other hand, some observers, including economists who provided advice to the ARB about the establishment of the cap–and–trade program, have recommended that greater use be made of auctions in the program and that fewer allowances be given away for free. They argued that greater use of auctions would make the program less reliant on inherently subjective decisions about which entities should receive allowances. Also, in choosing to give a certain portion of allowances away for free, the ARB has in effect chosen to forego tens of billions of dollars in state revenues that could otherwise be allocated by the Legislature over the life of the program to address its priorities. (As will be discussed below, however, there are legal constraints regarding the eligible use of auction revenues.)