Executive Summary

California's Statewide Automated Welfare System (SAWS) is made up of multiple systems which support such functions as eligibility and benefit determination, enrollment, and case maintenance at the county level for some of the state's major health and human services programs (including Medi–Cal, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids [CalWORKs], and CalFresh). These automation systems have been a sizable financial commitment for the state, taking multiple years and hundreds of millions of state and federal dollars to develop and maintain. Over the years, the Legislature has consolidated the total number of SAWS systems, reducing the state's financial burden of maintaining multiple systems and also assisting in standardizing the eligibility determination processes of the state's health and human services operations. Most recently, the Legislature enacted Chapter 13, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 16, Blumenfield), which will decrease the number of SAWS systems to two. Additionally, this legislation specifies that the reduction will occur by migrating, or moving, 39 counties from an existing system to Los Angeles County's new replacement system.

In this report, we identify several issues for the Legislature to consider as the administration pursues legislative goals for SAWS consolidation, with a particular focus on how to contain potentially significant, but to some extent avoidable, migration costs. We offer alternative procurement approaches for the migration that would encourage greater vendor participation and competition for state services. Increased competition should help drive down the costs for the migration effort. Finally, we make several recommendations intended to enhance legislative oversight and clarify legislative priorities for SAWS consolidation.

Introduction

The SAWS is made up of multiple systems which support such functions as eligibility and benefit determination, enrollment, and case maintenance at the county level for some of the state's major health and human services programs. This report provides a background on SAWS, presents and comments on recent legislative changes that would consolidate the SAWS' systems, and ends with recommendations for the Legislature to consider as the administration pursues consolidation activities.

Background

Development of the Consortia Strategy. Since the 1970s, the state has made several attempts to build a single, statewide automated welfare system to deliver and support some of California's major health and human services programs, such as Medi–Cal, CalWORKs, and CalFresh (formerly known as Food Stamps). In the early 1990s, several systems were under development. For example, the state, along with certain counties, began developing a system called Interim Statewide Automated Welfare System (ISAWS). Los Angeles (LA) County was developing its own system called the LA Eligibility Automated Determination, Evaluation, and Reporting System (LEADER). At the same time, other counties were pursuing their own automated systems, each attempting to demonstrate that theirs could be the single statewide system.

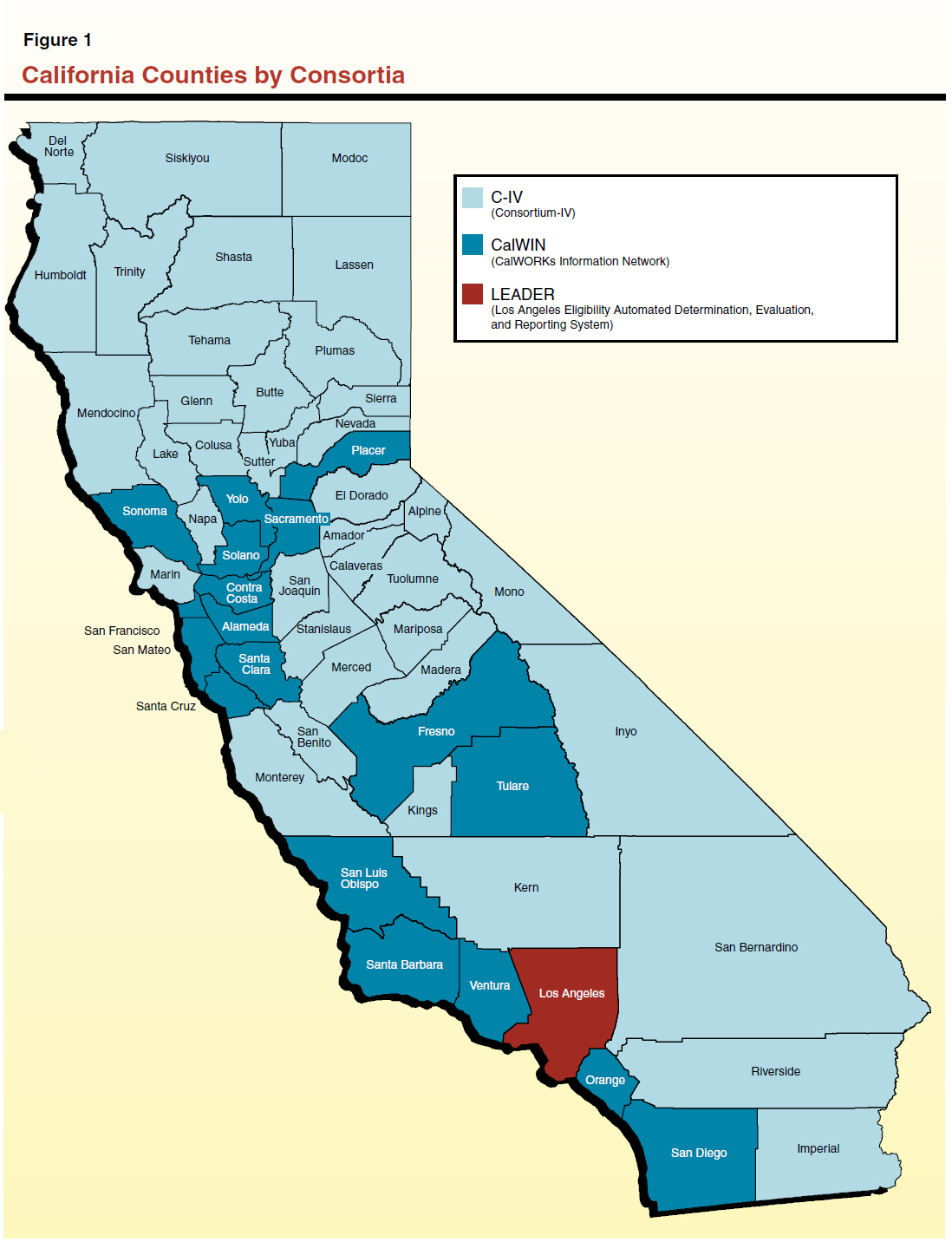

In 1995, the Legislature ultimately concluded that a single statewide system was not feasible at the time. Instead, it approved a strategy whereby a limited number of systems, called consortia, would make up SAWS. Specifically, the Legislature instructed the Health and Welfare Data Center, now called the Office of Systems Integration (OSI), to work with the counties on a consortia strategy that would include "no more than four county consortia." The Legislature chose ISAWS and LEADER as two of these consortia. The OSI and counties decided that two other county–developed systems, the CalWORKs Information Network (CalWIN) and Consortium IV (C–IV), would round out the four.

Reducing the Number of Consortia. In 2006 legislation, the Legislature expressed its preference to reduce the number of consortia. The administration had proposed migrating the 35 counties utilizing ISAWS to the C–IV consortium, rather than build a new system that would replace an aging ISAWS. (A migration, in simplest terms, is the effort of moving data housed in one county consortium system to another county consortium system.) The Legislature approved this plan and ISAWS Migration, as that effort was called, was completed in mid–2010. That migration cost about $210 million ($130 million General Fund) and brought the number of consortia to three. See Figure 1 for a current map of California counties by consortia.

Consortia Costs. The consortia systems have been a sizable financial commitment for the state. Developing each of the systems took multiple years and hundreds of millions of state and federal dollars. Once developed, the state has been responsible for paying the annual maintenance and operations (M&O) costs on these systems, totaling tens of millions of dollars. See Figure 2 for details on consortia development and maintenance costs.

Figure 2

Costs for the Statewide Automated Welfare System

(In Millions)

|

Consortium

|

Total/General Fund Costsa

|

|

Development

|

Maintenance and Operation

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

|

ISAWS (fully implemented in 35 counties in 1998)

|

$110/$90b

|

$20/$11

|

—c

|

|

LEADER (fully implemented in LA County in 2001)

|

110/75

|

31/16

|

$31/$15

|

|

C–IV (fully implemented in 4 counties in October 2004)

|

280/215

|

46/24

|

71/37d

|

|

CalWIN (fully implemented in 18 counties in 2006)

|

525/350

|

78/41

|

76/39

|

|

Totals

|

$1,025/$730

|

$175/$92

|

$178/$91d

|

Legislature Considers Again the Possibility of a Single Statewide System. Chapter 7, Statutes of 2009 (ABX4 7, Evans), directed the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and the Department of Social Services (DSS) to implement a statewide enrollment determination process for many of the programs administered by the SAWS consortia. The goals of Chapter 7 included (1) using state–of–the–art technology to improve the efficiency of eligibility determination processes and (2) minimizing the overall number of technology systems performing the eligibility process. The statute required DHCS and DSS to develop a comprehensive plan, including costs and benefits of possibly building a single statewide system, to streamline the eligibility determination process.

Administration Suspends Planning Effort for Possible Single Statewide System. To ensure the Legislature was kept informed of the plan, Chapter 7 required that the administration submit a strategic plan for a (minimum) 45–day legislative review period prior to a request for an appropriation to begin work on a new system related to eligibility determination process changes. While the administration did take initial steps to implement Chapter 7, a plan was never submitted to the Legislature for review. Ultimately, the administration suspended planning when the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in early 2010. In large part, this was due to the fact that the ACA will create significant changes to eligibility and enrollment processes for state health programs, such as Medi–Cal and Healthy Families, and will therefore impact the state systems, like SAWS, that support them. Additionally, ACA creates health benefit exchange systems that will need to interact with SAWS for information and data exchange. Eligibility changes, pursuant to ACA, could result in significant changes to the SAWS systems and therefore the administration paused in planning for a new system. (See the nearby box for more information on health exchanges.)

Health Benefit Exchanges

In March 2010, President Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Pursuant to ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, most U.S. citizens and legal residents must have health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. To make coverage more accessible and affordable, ACA creates new entities called American Health Benefit Exchanges, through which individuals and small businesses will be able to research, compare, check their eligibility for, and purchase health coverage. Each state may develop its own exchange system and has significant flexibility in its design and implementation. Federal law requires that state exchanges begin running no later than January 1, 2014. If a state cannot or chooses not to establish an exchange by that time, the federal government will establish and operate one within the state.

Chapter 655, Statutes of 2010 (AB 1602, John A. Pérez), established an independent entity within California state government called the Health Benefit Exchange (hereafter called the Exchange). The Exchange is comprised of a five–member board and is responsible for planning and implementing the state's health exchange system. In January 2012, the Exchange, in collaboration with California Department of Health Care Services and the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board, released a request for proposal that included the functions for the proposed exchange system, called the California Healthcare Eligibility, Enrollment, and Retention System (CalHEERS). The Exchange plans to award a contract in early April 2012 to a vendor who will design, develop, and implement CalHEERs. The vendor is responsible for building a system that includes multiple business functions such as: real–time eligibility determination; health plan certification, recertification, and decertification; reporting and tracking of data for federal, state, and local purposes; and consumer assistance. Additionally, CalHEERS must leverage existing state systems, which could include California's Statewide Automated Welfare System and other health–related systems, and be built using flexible technology to allow for future enhancements.

LEADER Replacement Plans

Technology Issues Lead to Proposed New System. As LEADER's maintenance contract approached an end in spring of 2005, the state and LA County considered building a replacement system rather than procure another vendor for continued maintenance. Project staff stated LEADER's dated technology could no longer meet the business needs of the county. Additionally, staff explained that when the LEADER system was originally designed, it was built using proprietary hardware and software, which meant that only the development vendor had the ability to maintain and update the system. These maintenance services have not been easily replaced and the state has had to enter into multiple "sole source" contracts with the development vendor for continued support. Sole source contracts are generally more expensive than contracts that have been competitively bid, where the presence of other vendors tends to drive down costs.

In 2005, the administration proposed moving LA County from the LEADER system to an existing consortia system, so as to no longer be dependent on a single vendor for its maintenance. However, in 2007, the administration decided to open the procurement to all viable and interested vendors, stating that the existing consortia systems did not meet all of LA County's program and business needs. The Legislature approved this change of approach, thus allowing LA County to go forward with a LEADER replacement system (LRS).

Delays in LRS Development. Since the Legislature's approval of LRS development, the state and LA County have proceeded with project activities. After several years of planning and preparing a request for proposal for LRS, the procurement for a vendor was planned for completion by July of 2008 and work was to begin on the system by summer of 2009. However, there have been several delays:

- In the 2009–10 Budget Act, the Legislature delayed the LRS project by six months, deferring expenditures in light of the state's financial condition. This delay pushed out the design, development, and implementation (DD&I) activities. Procurement efforts continued, however, and by the fall of 2009, project staff had selected Accenture LLP as the winning vendor to build the new system.

- In early 2010, the administration proposed delaying the project another six months to again defer DD&I activities and costs. The Legislature approved this additional delay.

- In the 2011–12 Governor's May Revision, the administration proposed another stop to LRS development, this time proposing an indefinite suspension of all project activities. (See the nearby box for more details on the administration's proposal to suspend LRS development.) However, the Legislature approved continued funding for LRS development in the 2011–12 Budget Act, but at less than one–half of the funding level included in the Governor's 2011–12 January budget proposal. (The Legislature reduced the General Fund appropriation from the initially proposed $27 million to $12 million.) In making this appropriation, the Legislature was aware that the administration was preparing a long–term plan for the SAWS systems to submit to the federal government.

Administration Proposes Suspending LRS Development

As part of the 2011–12 Governor's May Revision, the administration proposed indefinitely suspending the Los Angeles Eligibility Automated Determination, Evaluation, and Reporting System (LEADER) replacement system (LRS) development, citing the state's continued financial problems as a primary factor. However, the administration also stated that the federal government wanted to see a long–term plan for the state's eligibility systems that included integration with the state's proposed health exchange system, pursuant to federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Without federal approval of the plan, the federal government would not approve federal financial participation for either the maintenance of the LEADER system beyond April 2013 or the development of LRS. The administration needed additional time to develop such a plan, and thus proposed the suspension of LRS development. The administration submitted a high–level strategic plan to the federal government in the summer of 2011. At the time this report was prepared, the administration was expecting to soon receive a response from the federal government regarding its approval for the state to proceed with LRS development and its continued financial participation.

The Selected LRS Proposal. Based on Accenture LLP's proposal for LRS development, project staff estimated the new system would take four years to build and cost about $475 million (total funds). (Generally, the federal government has paid about 60 percent of the total development costs for the state's other welfare automation systems.) It is important to note that the consortium has not yet entered into a contract with the vendor and will only do so once it has received federal approval to proceed with LRS development and is guaranteed federal financial participation for the new system. Therefore, the Legislature has a window of opportunity to potentially direct changes to the process of LRS development.

Legislature Establishes Plan for a Two–System Consortia

Highlights of Legislation. Through its actions in the 2011–12 Budget Act, the Legislature made known its intent that the administration should proceed with LRS development. Additionally, the Legislature enacted Chapter 13 to further highlight its priorities for the future of SAWS. Specifically, Chapter 13 states that there will be two consortia systems that make up SAWS. It directs OSI to migrate the 39 counties currently in the C–IV consortium to a system that would replace both the LEADER and C–IV consortia. The Legislature determined that the CalWIN consortium would be the state's other system.

Major Milestone for SAWS. Chapter 13 is a major milestone in SAWS history not only because it reduces the number of consortia to two, but because it also specifies which two consortia and how consolidation will occur—through a migration. We believe the move towards fewer systems is generally a good one and in the past have suggested that the Legislature create a goal of no more than two consortia in SAWS. Fewer systems decrease M&O costs, avoid some future development expense for building new systems, and assist in standardizing the state's health and human services operations at the county level. And having more than one consortium still encourages competition among the remaining systems. For example, we have witnessed how innovation in one consortium has often spurred similar efforts to improve the other systems. (See our May 2010 report, Moving Forward With Eligibility and Enrollment Process Improvements, for details.)

No Requirement for Particular Plans. Through Chapter 13, the Legislature gives broad authority to the administration to pursue the Legislature's stated goals for welfare automation system consolidation and migration. We note that, unlike Chapter 7, which directs the administration to provide a strategic plan for legislative review before an appropriation, Chapter 13 does not include a similar requirement. Chapter 13 also does not require the administration to develop a specific type of plan known as a feasibility study report (FSR), the first step that state departments are generally required to undertake as part of the California Technology Agency's approval of an information technology (IT) project. An FSR is a cost–benefit analysis that justifies a department's decision to proceed with an IT project and includes alternative approaches to meeting business needs as well as estimates of total costs and a timeframe for developing a new system.

While Chapter 13 does not require that the administration develop any particular plans to implement the legislation, there is nothing in Chapter 13 or other state law that prevents the administration from conducting a planning effort that includes analyses of costs and alternative approaches to meeting the goals in question.

C–IV Migration to Be Handled Under a Specified Contract. Chapter 13 directs OSI to oversee the C–IV migration "under the LRS contract." Statute does not specify a vendor. The administration, however, has stated in communications with the federal government that it plans to amend the current contract with Accenture LLP to include the migration work. The administration's decision means that Accenture LLP would be given the migration work.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Addressing the Lack of Planning for C–IV Migration

As stated above, Chapter 13 does not require the administration to conduct an FSR or other plan that analyzes alternatives for migrating the 39 C–IV counties to LRS. Without such an initial analysis, it is unknown whether a certain approach is the most efficient, cost–effective, and/or least risky. Some projects that have been allowed to bypass this initial analysis (either by executive proclamation and/or through statutory authority) have encountered issues that could have been foreseen and dealt with earlier in the project's planning stages. These issues can lead to significant cost increases and system delays.

Migration Costs Could Be Significant

Currently, it is difficult to know how much the C–IV migration effort could cost. The ISAWS Migration project, the only large–scale migration the state has conducted for the SAWS systems, cost over $200 million (all fund sources). While that effort may be very different from the proposed migration, without an FSR or similar plan the state has no baseline estimate of the cost or the amount of time this migration could take. What is certain is that the current $475 million price tag to build LRS will increase, perhaps significantly, to account for the additional migration activities. Without understanding the scope and complexity of the effort, the state could be at a disadvantage when negotiating to amend the current LRS contract.

Consider Alternative Procurement Approaches for the C–IV Migration

The administration's current plans are to proceed with the LRS procurement results and amend the Accenture LLP contract for LRS to include the migration of C–IV. However, this plan could lead to potentially significant cost increases for the state, some of which could potentially be avoidable. The result of this plan could be very similar to the results under a non–competitive bid or sole source contract where no other vendors are allowed to compete for the work. (As previously mentioned, these types of contracts can lead to increased costs, as no other vendors are present to potentially drive down costs or offer alternative solutions.) To better control for cost increases due to the migration, the state may wish to consider alternative procurement options that would infuse more competition for the migration work, potentially offering different, less costly alternatives. We offer several options below and describe potential advantages and disadvantages for each.

Option 1: Reopen the LRS Procurement. Rather than amend the current Accenture LLP proposal for LRS, the state could reopen the LRS procurement to the original vendors who submitted proposals, adding the C–IV migration as a component. Four vendors participated in the initial procurement. This option would allow each of the original vendors a limited time to submit a revised proposal. This option could create some competition and help bring down overall project costs. It is important to point out that Accenture LLP built the current C–IV system and is the selected vendor poised to build LRS. Generally, an incumbent vendor has a significant advantage over other vendors when bidding on work that involves its own systems. As a result, this option might not significantly enhance competition. Additionally, this option could easily delay the project start date by months as vendors rewrite and resubmit proposals and the state reviews them. Delays are costly for the state as many project staff must still be retained and project contracts extended.

Option 2: Plan Migration as a Separate Project. Another option for the state to consider is to continue with the proposed LRS project using the administration's chosen vendor, leaving the C–IV migration as a separate project. This option would require conducting a second procurement for a vendor who would migrate the 39 C–IV counties to LRS once it has been implemented in LA County. An advantage of this option is that it creates an opportunity for more than just the original vendors to participate. Opening up the competition could attract vendors with particular expertise in migration activities. These vendors may not have been able to compete in a procurement to build a complex eligibility system, but they may be strong competitors for a migration project. As with the first option, the incumbent vendor may still have an advantage over all other vendors due to its knowledge of both the C–IV system and the newly developing LRS. However, a possible advantage of conducting a new procurement is that it forces the incumbent vendor to reduce its cost for the migration, as it knows that more viable vendors are competing for the migration contract. This could potentially help the state secure a better price for the migration effort. Another advantage of this option is that it would not delay the LRS project from commencing because the procurement for the migration could be conducted concurrently with LRS development. The downside of this option is that conducting a new procurement process for migration services could be administratively costly and add additional time to the overall migration effort.

Option 3: Break Migration Into Multiple Contracts. Breaking the migration work into separate service contracts and hiring vendors for each service could create a more competitive environment and potentially reduce the state's costs for the overall migration. This option would require the state to elicit vendors for major components of the migration—such as project management, data conversion, testing, training, service desk, and change management. As with option two above, this alternative opens the door to multiple vendors who could compete for each of the proposed contracts. These vendors may be experts in a particular service and could possibly be able to offer more competitive rates than the incumbent vendor, thus helping to lower the overall costs for the migration work. A disadvantage of this option, however, is that the state would have to conduct several procurements and manage numerous contracts at the same time. From a resource and management perspective, this could be difficult given that the state would also be developing LRS.

Consider Requiring Cost–Reasonableness Assessments

A "cost–reasonableness assessment" is a study conducted by contracted experts who collect data on the costs of a particular effort (for example, building a new IT system) from other public and private–sector experiences. They extrapolate what costs might be for California to proceed with a similar effort, and then compare these results with the information included in a vendor's proposal.

Regardless of the chosen procurement approach, but particularly if it is a sole–source approach, there would be value in performing a cost–reasonableness assessment of a C–IV migration. The administration has not performed such an assessment to date. Conducting a cost–reasonableness assessment for the migration scenario would give the state information about how much a migration could potentially cost. This would be valuable data to possess, particularly if the chosen procurement approach is to amend the current contract with the already chosen vendor to include migration as a component. Under this approach, no other vendor would be able to put forward a cost proposal for which the state could use as a comparison to know whether amending the current contract would be a cost–effective approach to the C–IV migration.

Recommend Legislature Direct Administration to Review Feasible Options for Migration

Given the lack of information the state has regarding the cost for a C–IV migration, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report on the extent to which the procurement options provided above (or others not presented here) may be feasible and potentially less costly alternatives to its current plans. The Legislature could require the administration to conduct an FSR or other analysis, such as a cost–reasonableness assessment or cost–benefit analysis. This exercise could provide vital information on the best and most cost–effective approach to consolidating the consortia systems.

As mentioned above, the state has not yet signed a contract for LRS development. Therefore, this could be an opportunity for the state to conduct its analyses of migration alternatives without being committed to a specific vendor or proposed plan.

Improving Legislative Oversight

By statute, OSI is required to report to the Legislature each February 1st on the general state of SAWS. Reports must include any significant schedule, budget, or functionality changes that occur to any of the consortium. Chapter 13 adds that OSI include the projected timeline and key milestones for LRS development in this same report. No other legislative reporting requirements are stipulated. Given the significant costs and magnitude of building a new eligibility system for LA County as well as the effort to migrate 39 counties to that system, more frequent reporting requirements may be necessary to enhance the Legislature's oversight of this project.

Recommend Enhanced Reporting to the Legislature

Currently, there are multiple state projects of similar scope and magnitude to the LRS effort under development. For many of these projects, administration staff provide regular updates to the Legislature or legislative staff to ensure the Legislature is aware of significant milestones, issues, and risks. These updates are often presented through informal meetings rather than formal written reports, allowing two–way communication to occur. We understand that these regular meetings, rather than being onerous, are considered helpful to project staff. They have provided opportunities to communicate project status to the Legislature, allowed the administration to showcase its accomplishments, and provided a forum for administration and legislative priorities to be discussed and heard, among other benefits. We believe similar communication would be particularly helpful during LRS development and C–IV migration.

We recommend that, during budget hearings, the Legislature direct the administration to conduct regularly scheduled briefings between the administration and legislative staff as LRS progresses and as the administration goes forward with its migration planning. The frequency could vary depending on the phase of the project. For example, the Legislature may want monthly or as–needed updates during key points, such as the testing and piloting of LRS or the transfer of data during the migration effort.

Consider Reconciling Chapters 7 and 13

Chapter 7's goals deal mainly with streamlining the eligibility determination processes for health and human services programs. However, as discussed above, Chapter 7 leaves open the door for the creation of a single statewide welfare system. If the Legislature's long–term plan for SAWS is to eventually move to a single system, it may make sense to leave Chapter 7 intact. However, if the Legislature's long–term plan is the maintenance of a two–consortia system, there could be potential conflicts between Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 goals. As it currently stands, any administration (current or future) could present a plan that further consolidates SAWS into a single system, as allowed under Chapter 7. However, such a plan might conflict with legislative priorities, such as enhanced vendor competition, found under the more recently passed Chapter 13 legislation.

Recommend Legislature Clarify Its Intent for SAWS

As suggested above, leaving Chapters 7 and 13 intact as they are could leave ambiguity regarding legislative intent on the future of SAWS. We recommend that the Legislature consider enacting legislation that would clarify its intent. This could include repealing or amending portions of Chapter 7 to correspond with Chapter 13 goals.

Summary

Through Chapter 13, the Legislature has stated its intent that California reduce from three to two the number of consortia systems that make up the state's automated welfare system. We believe this decision has merit and in the long run should reduce the state's overall welfare automation costs and help standardize the eligibility determination processes for many of the state's major health and social services programs. In this report, we identify issues for the Legislature to consider as the administration pursues Chapter 13 goals, with a particular focus on containing the potentially significant, but to some extent avoidable, costs associated with a C–IV migration. We offer alternative approaches that the administration could take to help mitigate costs and make several recommendations for the Legislature to adopt regarding SAWS consolidation and its oversight thereof. Figure 3 summarizes the issues raised and our corresponding recommendations.