Executive Summary

Legislation enacted in 2013–14 made major changes both to the way the state allocates funding to school districts and the way the state supports and intervenes in underperforming districts. The legislation was the culmination of more than a decade of research and policy work on California’s K–12 funding system. This report describes the major components of the legislation, with the first half of the report describing the state’s new funding formula and the second half describing the state’s new system of district support and intervention. Throughout the report, we focus primarily on how the legislation affects school districts, but we also mention some of the main effects on charter schools. (This report does not cover the new funding formula for county offices of education [COEs], which differs in significant ways from the new district formula.) The report answers many of the questions that have been raised in the aftermath of passage regarding the final decisions made by the Legislature and the Governor in crafting new K–12 funding and accountability systems for California.

The Formula

Components

Chapter 47, Statutes of 2013 (AB 97, Committee on Budget) created the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Two subsequently enacted pieces of legislation—Chapter 70, Statutes of 2013 (SB 91, Committee on Budget) and Chapter 357, Statutes of 2013 (SB 97, Committee on Budget)—made minor changes to the formula. As set forth in this package of legislation, the LCFF has several components, described below. (Except where otherwise noted, the components that apply to school districts also apply to charter schools.)

Sets Uniform, Grade–Span Base Rates. Under the new formula, districts receive the bulk of their funding based on average daily attendance (ADA) in four grade spans. Figure 1 displays the four LCFF grade–span base rates as specified in Chapter 47. Each year, beginning in 2013–14, these target base rates are to be updated for cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs). The differences among the target grade–span rates reflect the differences among existing funding levels across the grade spans. Specifically, the new base–rate differentials are linked to the differentials in 2012–13 statewide average revenue limit rates by district type (the same rates previously used to set charter school grade–span funding rates). These grade–span differences are intended to recognize the generally higher costs of education at higher grade levels.

Figure 1

Overview of Local Control Funding Formulaa

|

Formula Component

|

Rates/Rules

|

|

Target base rates (per ADA)b

|

- K–3: $6,845

- 4–6: $6,947

- 7–8: $7,154

- 9–12: $8,289

|

|

Base rate adjustments

|

- K–3: 10.4 percent of base rate.

- 9–12: 2.6 percent of base rate.

|

|

Supplemental funding for certain student subgroups (per EL/LI student and foster youth)

|

20 percent of adjusted base rate.

|

|

Concentration funding

|

Each EL/LI student above 55 percent of enrollment generates an additional 50 percent of adjusted base rate.

|

|

Add–ons

|

Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant, Home–to–School Transportation, Economic Recovery Target.

|

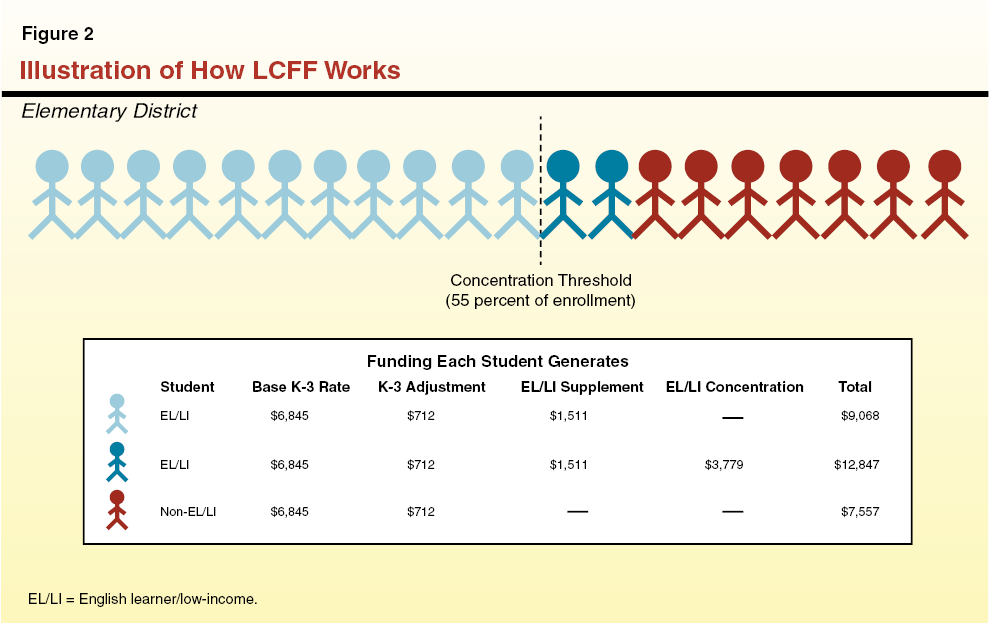

Adjusts Early Elementary and High School Base Rates. The LCFF includes certain adjustments to the K–3 and high school base rates. These adjustments effectively increase the base rates for these two grade spans. The K–3 adjustment increases the K–3 base rate by 10.4 percent (or initially $712 per ADA)—for an adjusted, initial K–3 base rate of $7,557. This adjustment is intended to cover costs associated with class size reduction (CSR) in the early grades. (The $712 per–pupil adjustment reflects the average K–3 CSR rate under the previous funding rules.) The high school adjustment increases the grades 9–12 base rate by 2.6 percent (or initially $216 per ADA)—for an adjusted, initial high school base rate of $8,505. This adjustment is not designated for any particular activity, but the genesis of the adjustment related to the costs of providing career technical education (CTE) in high school. The $216 adjustment reflects the average total amount spent per pupil on Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROCPs) under the old system. Moving forward, the adjustment percentages will remain the same, though the dollar value of the adjustments will increase as the base rates rise due to statutorily authorized COLAs.

Includes Supplemental Funding for English Learners and Low–Income (EL/LI) Students. The LCFF provides additional funds for particular student groups. Under the formula, each EL/LI student and foster youth in a district generates an additional 20 percent of the qualifying student’s adjusted grade–span base rate. For instance, an LI kindergartener generates an additional $1,511 for the district, which is 20 percent of the adjusted K–3 base rate of $7,557. (Because all foster youth also meet the state’s LI definition, hereafter we do not refer to them as a separate subgroup.) For the purposes of generating this supplemental funding (as well as the concentration funding discussed below), a district’s EL/LI count is based on a three–year rolling average of EL/LI enrollment. Students who are both EL and LI are counted only once. For more information regarding the classification of EL/LI student groups, see the nearby box.

Classification of English Learner/Low–Income (EL/LI) Students

Classification of EL Students. For the purposes of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), students are classified as EL based on a home language survey and the California English Language Development Test (CELDT). If a parent or guardian reports on the home language survey that a language other than English is the student’s initial language learned or the primary language used at home, the student is required to take the CELDT. If the student is determined by the school district not to be English proficient based on CELDT results, then the student is classified as EL. Each year thereafter, an EL student is reassessed using the CELDT. Once a student is determined to be English proficient—based on CELDT results, performance on other state assessments, teacher input, and local criteria—the student is reclassified as Fluent English Proficient (FEP). Each school district can use its own criteria for reclassifying EL students as FEP. Under the LCFF, no time limit is placed on how long an EL student can generate supplemental and concentration funding for a district, but a student reclassified as FEP who is not also LI will no longer generate additional funding.

Classification of LI Students. For the purposes of the LCFF, LI students are those that qualify for free or reduced–price meals (FRPM). Eligibility for FRPM is determined by school districts through a variety of means. In many cases, students are determined FRPM–eligible through an application process sent to students’ households. If a household’s income is below 185 percent of the federal poverty line ($43,568 for a family of four), the student is eligible for FRPM. In other cases, students are directly certified as FRPM–eligible due to participation in other social service programs, such as the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program. Foster youth automatically are eligible for FRPM, therefore the foster family’s income has no bearing on the foster student’s FRPM eligibility. An LI student will generate supplemental and concentration funding for a district until the student is no longer FRPM–eligible.

Provides Concentration Funding for Districts With Higher EL/LI Populations. Districts whose EL/LI populations exceed 55 percent of their enrollment receive concentration funding. Specifically, as shown in Figure 2, these districts receive an additional 50 percent of the adjusted base grant for each EL/LI student above the 55 percent threshold. (A charter school cannot receive concentration funding for a greater proportion of EL/LI students than the district in which it resides. For instance, if a charter school has 80 percent EL/LI enrollment but the district in which it resides has only 60 percent EL/LI enrollment, the charter school’s concentration funding is capped based on 60 percent EL/LI enrollment. If a charter school has multiple sites located in multiple districts, its concentration funding is capped based on the encompassing district with the highest EL/LI concentration, or its own EL/LI concentration if lower.)

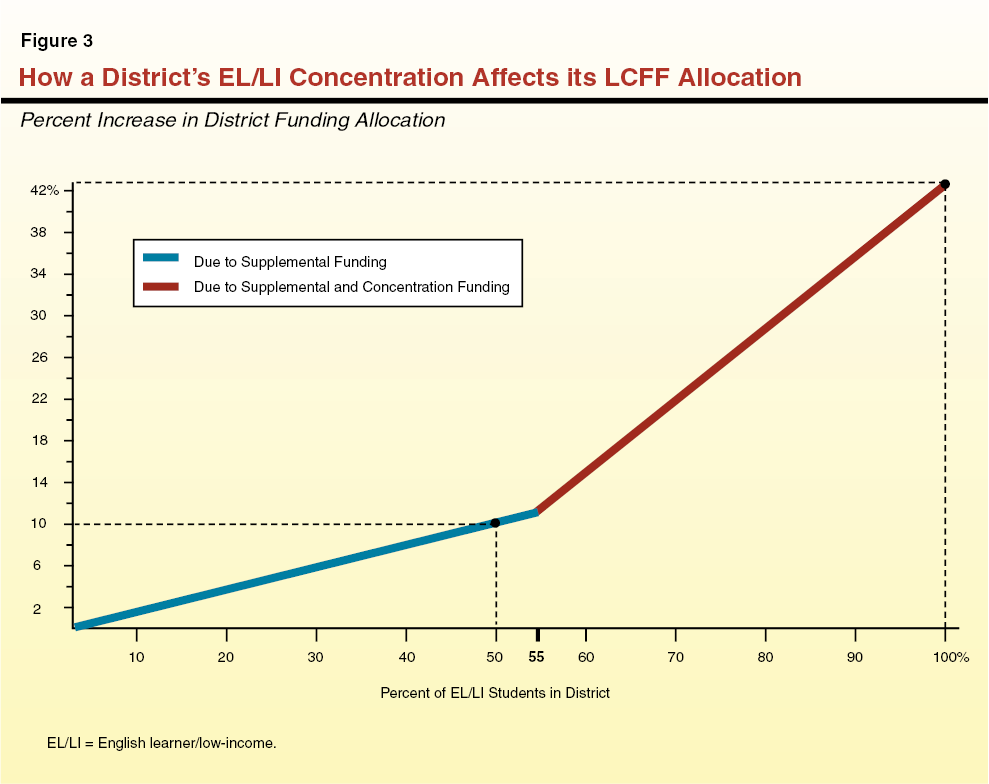

Effect of Supplemental and Concentration Funding on a District’s Total Allocation. In the description above, the supplement and concentration factors are described in per–student terms. Alternatively, the supplement and concentration factors can be viewed in per–district terms. Thinking of the supplement and concentration factor in this latter way allows total district funding allocations to be compared more easily. As seen in Figure 3, as a district’s proportion of EL/LI students increases, so does its total funding allocation. For instance, a district with 50 percent EL/LI students has a total allocation that is 10 percent higher than the same–sized district with no EL/LI students. In Figure 3, the first section of the line (colored blue) shows percent increases in a district’s funding allocation up to the 55 percent EL/LI threshold, whereas the second section of the line (colored red) shows funding increases once a district passes the 55 percent concentration threshold and begins receiving concentration funding in addition to supplemental funding. As shown in the figure, a district in which every student is EL/LI has a total funding allocation 42.5 percent greater than the same–sized district with no EL/LI students.

Treats Two Existing Categorical Funding Streams as Add–Ons. Funds from two existing programs—the Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant and Home–to–School (HTS) Transportation program—are treated as add–ons to the LCFF. Districts that received funding from these programs in 2012–13 will continue to receive that same amount of funding in addition to what the LCFF provides each year. Districts that did not receive funds from these programs in 2012–13 do not receive these add–ons moving forward.

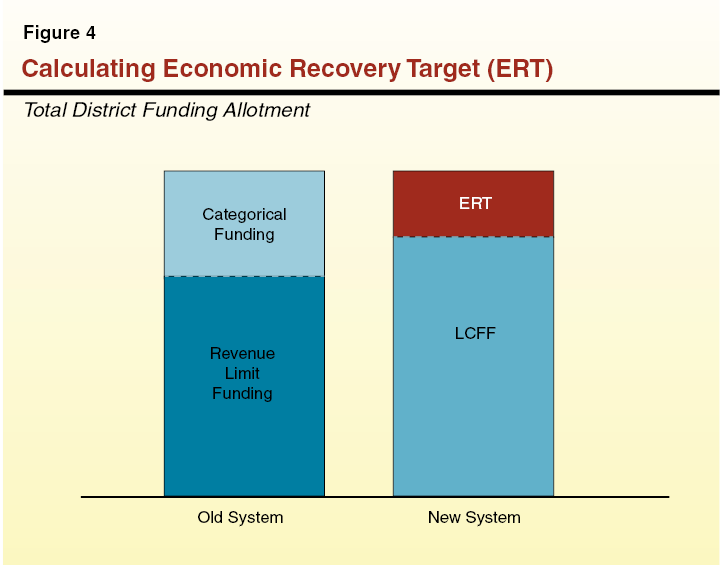

Also Provides New Economic Recovery Target (ERT) Add–On to Some Districts. Had the revenue limit deficit factor been retired and categorical program funding been restored, the previous funding system would have generated greater levels of funding than the LCFF for approximately 230 districts (about 20 percent of districts). To address this issue, the new funding system provides an ERT add–on to a subset of these districts. As shown in Figure 4, the ERT add–on amount equals the difference between the amount a district would have received under the old system and the amount a district would receive based on the LCFF in 2020–21. To derive the amount a district would have received under the old system in 2020–21, assumptions are made that the revenue limit deficit factor would have been retired, a 1.94 percent COLA would have been applied to revenue limits every year from 2013–14 through 2020–21, and categorical funding would be increased to the district’s 2007–08 level (reflecting an increase of 24 percent over the 2012–13 level). Approximately 130 districts are eligible to receive the ERT add–on. The 100 remaining districts are not eligible for the add–on because of their exceptionally high per–pupil funding rates. Specifically, a provision disallows a district from receiving an ERT add–on if its funding exceeds the 90th percentile of per–pupil funding rates under the old system (estimated to be approximately $14,500 per pupil in 2020–21).

Spending Restrictions

The LCFF eliminates the vast majority of categorical spending restrictions. In their place, the LCFF establishes a more limited set of spending restrictions, some of which apply over the long term and some of which are applicable only during the initial transition period.

Long–Term Spending Requirements

Many Existing Categorical Spending Requirements Removed. Approximately three–quarters of categorical programs were eliminated in tandem with the creation of the LCFF. As a result, the majority of categorical spending restrictions that districts faced under the old system were eliminated. Under the new system, 14 categorical programs remain. Figure 5 lists those categorical programs that were eliminated and those that are retained under the new system.

Figure 5

Treatment of Categorical Programs Under LCFF

|

Retained Programs

|

|

|

Adults in Correctional Facilities

After School Education and Safety

Agricultural Vocational Education

American Indian Education Centers and Early Childhood Education Program

Assessments

Child Nutrition

|

Foster Youth Services

Mandates Block Grant

Partnership Academies

Quality Education Improvement Act

Special Education

Specialized Secondary Programs

State Preschool

|

|

Eliminated Programs

|

|

|

Advanced Placement Fee Waiver

|

Instructional Materials Block Grant

|

|

Alternative Credentialing

|

International Baccalaureate Diploma Program

|

|

California High School Exit Exam Tutoring

|

National Board Certification Incentives

|

|

California School Age Families

|

Oral Health Assessments

|

|

Categorical Programs for New Schools

|

Physical Education Block Grant

|

|

Certificated Staff Mentoring

|

Principal Training

|

|

Charter School Block Grant

|

Professional Development Block Grant

|

|

Civic Education

|

Professional Development for Math and English

|

|

Community–Based English Tutoring

|

School and Library Improvement Block Grant

|

|

Community Day School (extra hours)

|

School Safety

|

|

Deferred Maintenance

|

School Safety Competitive Grant

|

|

Economic Impact Aid

|

Staff Development

|

|

Educational Technology

|

Student Councils

|

|

Gifted and Talented Education

|

Summer School Programs

|

|

Grade 7–12 Counseling

|

Teacher Credentialing Block Grant

|

|

High School Class Size Reduction

|

Teacher Dismissal

|

Districts Eventually Must Ensure “Proportionality” When Spending EL/LI Funds. Under the LCFF, districts will have to use supplemental and concentration funds to “increase or improve services for EL/LI pupils in proportion to the increase in supplemental and concentration funds.” The exact meaning and regulatory effect of this proportionality clause is currently unknown. On or before January 31, 2014, the State Board of Education (SBE) is required to adopt regulations regarding how this clause will be operationalized. These regulations also may include the conditions under which districts can use supplemental and concentration funds on a school–wide basis.

Districts Encouraged to Have K–3 Class Sizes No More Than 24 Students. Under full implementation of the LCFF, as a condition of receiving the K–3 base–rate adjustment, districts must maintain a K–3 school–site average class size of 24 or fewer students, unless collectively bargained otherwise. If a district negotiates a different class size for those grades, the district is not subject to this provision and will continue to receive the adjustment. Absent a related collective bargaining provision, were a particular school site in a district to exceed an average class size of 24, the district would lose the K–3 adjustment for all its K–3 school sites.

Restrictions on HTS Transportation Funding Maintained. Starting in 2013–14, districts receiving the HTS Transportation add–on must spend the same amount of state HTS Transportation funds as they spent in 2012–13. Districts that did not receive HTS Transportation funds in 2012–13 and therefore are not eligible for the add–on moving forward, do not have similar transportation spending requirements.

Short–Term Requirements

Specific Maintenance–of–Effort (MOE) Requirements Imposed During First Two Years of Implementation. Of the state categorical funds they received, school districts are required to spend no less in 2013–14 and 2014–15 than they did in 2012–13 on ROCPs and Adult Education. If districts received funding for ROCPs and/or HTS Transportation through a joint powers authority (JPA), they must continue to pass through those funds to the JPA in 2013–14 and 2014–15. Funds used to satisfy these MOE requirements count towards a district’s LCFF allocation. Consequently, districts subject to these MOE requirements will have relatively less general purpose funding over this two–year period. (A district that already shifted all funds away from these programs as part of its response to categorical flexibility is not subject to these MOE requirements.)

Districts Must Make Progress Toward Meeting CSR Goal During Transition Period. As mentioned earlier, to receive the K–3 base–rate adjustment, districts by full LCFF implementation must reduce K–3 class size to no more than 24 students, unless collectively bargained otherwise. Over the phase–in period (discussed later in more detail), districts must make progress toward this goal in proportion to the growth in their funding. For example, if a district started with an average K–3 class size of 28 students, and it received new funding equivalent to 10 percent of its LCFF funding gap, that district would have to reduce average K–3 class size to 27.6 students (10 percent of the difference between 28 and 24). Similar to the CSR requirement under full implementation, this interim requirement does not apply to districts that collectively bargain K–3 class sizes.

Cost of Formula

As explained below, the LCFF costs significantly more than the previous funding system. As a result, it will take several years to fully transition to the new funding formula.

Fully Implementing LCFF and ERT Add–On Estimated to Cost an Additional $18 Billion. Were the state to fully implement the LCFF in 2013–14, the costs would be $18 billion more than the state spent on K–12 education in 2012–13. (This assumes current levels of ADA, EL/LI enrollment, and property tax revenue.) Given the cost, coupled with projected growth in Proposition 98 funding, fully implementing the new system is anticipated to take eight years. Each year the total General Fund cost of the new system will change somewhat due to providing COLAs, fluctuations in ADA and student demographics, and growth in property tax revenue.

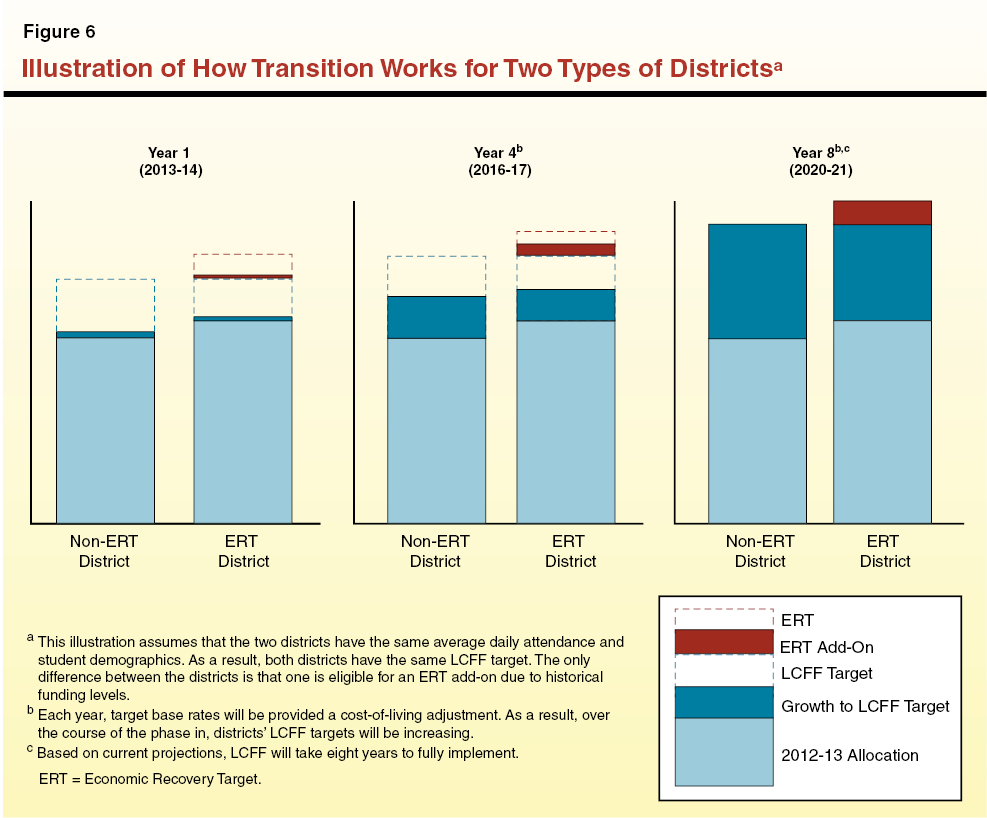

Additional LCFF Funding to Be Allocated Based on Funding “Gap.” Over the course of implementation, districts will receive new funding based on the difference (or gap) between their prior–year funding level and their target LCFF funding level. Every district will see the same proportion of their gap closed, but the dollar amount they receive will vary depending on the size of their gap. For example, in 2013–14, districts (in most cases) will have 12 percent of their gap filled. For a district whose gap is $100 million, this corresponds to $12 million in additional funding. For a district whose gap is $10 million, this corresponds to $1.2 million in additional funding. Figure 6 depicts transition funding for years one, four, and eight for a non–ERT district as well as an ERT district (discussed below).

Funding for ERT Add–On to Be Allocated in Equal Increments Over Eight–Year Period. Districts eligible to receive the ERT add–on will receive incremental ERT funding over the course of implementation in addition to their gap funding discussed above. As depicted in Figure 6, an ERT district will receive the same proportion of gap funding towards its LCFF target as other non–ERT districts, as well as a portion of its ERT add–on. In 2013–14, an ERT district will receive one–eighth of its add–on, in year two two–eighths, in year three three–eighths, etcetera. In year eight (the estimated year of full implementation), ERT districts will receive their full ERT add–on (as calculated in 2013–14) and will continue to receive this add–on amount in perpetuity. Changes in the implementation timeline for LCFF will not affect the ERT funding schedule.

Distributional Effects of Formula

Vast Majority of Districts to Receive More State Aid, No District to Get Less State Aid. The vast majority of districts will see significant increases in funding under the LCFF. That notwithstanding, statute further includes a “hold harmless” provision that specifies no district is to receive less state aid than it received in 2012–13. Specifically, no district is to receive less moving forward than it received last year for revenue limits (calculated on a per–ADA basis) and categorical programs (calculated based on the district’s total entitlement).

A Few Districts Will Not Receive Additional Funds. Though most districts will see funding increases under the new formula, approximately 15 percent of districts will not receive additional funding. (These districts, which have particularly high existing per–pupil funding rates, are the ones that benefit from the hold harmless provision described above.) Three types of districts are unlikely to receive additional funding.

- Basic Aid Districts. Most basic aid districts currently have more per–pupil funding than needed to meet their LCFF targets and their ERT. As a result, they will continue to receive the same amount of state aid they received in 2012–13 (though, as discussed below, a few districts will fall out of basic–aid status and begin receiving state aid as a result of the LCFF).

- Non–Isolated, Single–School Districts. Prior to 2012–13, these types of districts were eligible to receive additional funding if the school met the necessary small school (NSS) ADA requirements. Starting in 2013–14, schools that are not geographically isolated are no longer eligible for NSS funding. As a result, these districts’ 2012–13 funding levels exceed their LCFF targets and they will continue receiving their 2012–13 amounts until those amounts drop below their LCFF targets.

- Anomalous Districts. Some districts had funding levels under the old system that were abnormally high either because of peculiar categorical rules (such as receiving an extremely high meals–for–needy–pupils add–on) or peculiar charter–school conversion rules (used by a few districts to receive significant fiscal benefit from conversions). These districts also will continue to receive their 2012–13 funding amounts until those amounts drop below their LCFF targets.

A Few Districts Likely to Fall Out of Basic Aid Status and Begin Receiving State Aid. Under the previous funding system, property tax revenue counted only against a district’s revenue limits. Consequently, basic aid districts were those districts whose revenue limit entitlements were equal to or less than their local property tax revenue. Under the LCFF, local property tax revenue counts against a district’s entire LCFF allocation (which has base rates higher than old revenue limit rates and greater funding for EL/LI students). As a result, the threshold for basic aid status is significantly higher under the LCFF. Moreover, some districts recently entered basic aid status as a result of state cuts in revenue limit rates. These districts are most likely to fall out of basic aid status under the new system, but a few other basic aid districts also might fall out of basic aid status due to increased funding levels under the LCFF.

Transparency and Accountability Under New System

In addition to creating a new funding formula, the 2013–14 package of legislation establishes a set of new rules relating to school district transparency and accountability. Specifically, under the new rules, districts are required to adopt Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs). Districts that do not meet the goals specified in their LCAPs and fail to improve educational outcomes are to receive assistance through a new system of support and intervention. We describe this new system in more detail below.

District Development and Adoption of LCAPs

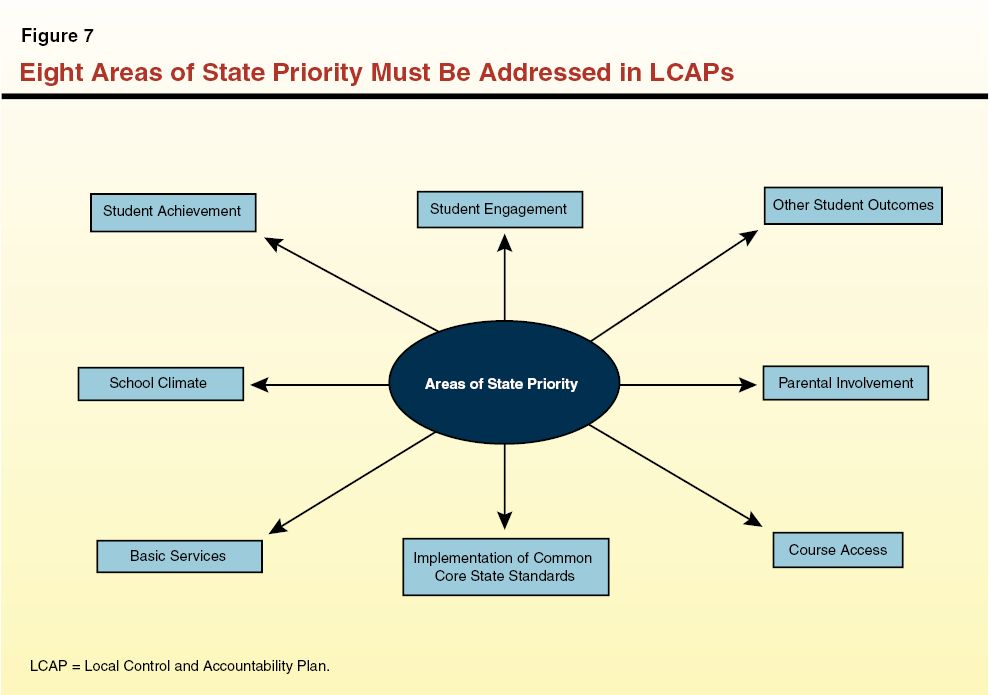

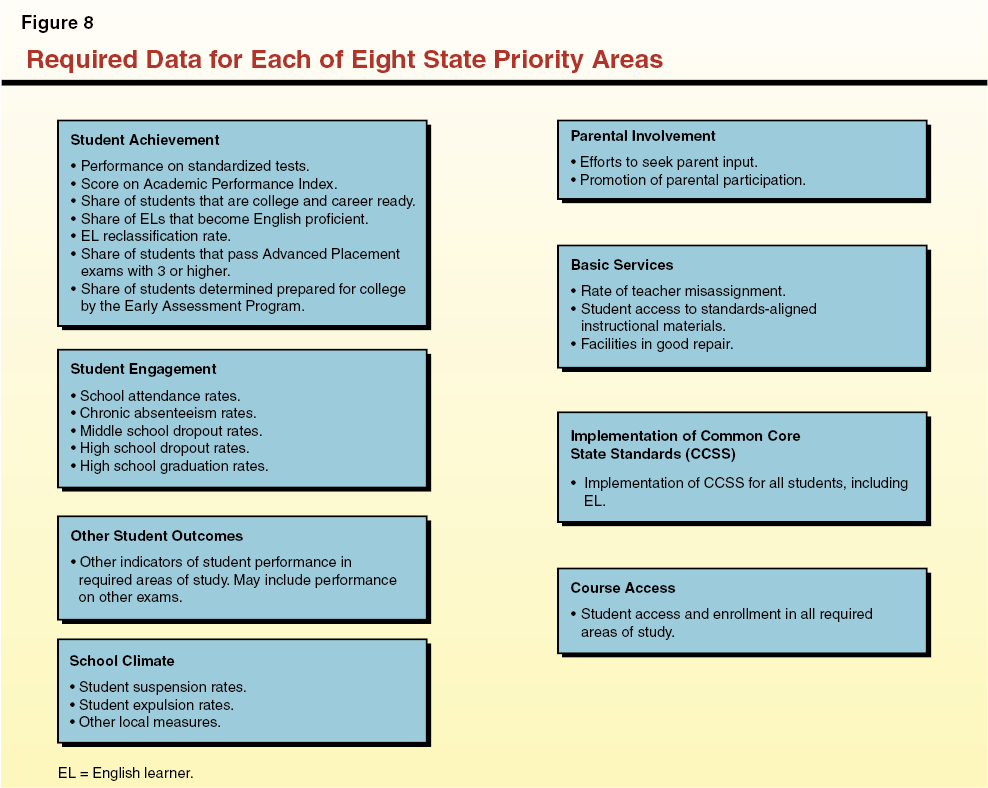

Districts Must Set Annual Goals in Eight Specified Areas. Each LCAP must include a school district’s annual goals in each of the eight areas shown in Figure 7. These eight areas of specified state priorities are intended to encompass the key ingredients of high–quality educational programs. Figure 8 identifies how districts are to measure success in each of the eight areas, with districts required to include associated data in their LCAPs. The plans must include both district–wide goals and goals for each numerically significant student subgroup in the district. (To be numerically significant, a district must have at least 30 students in a subgroup, with the exception of foster youth, for which districts must have at least 15 students.) The student subgroups that must be addressed in the LCAPs are listed in Figure 9. (In addition to specified state priorities, districts’ LCAPs can include annual goals in self–selected areas of local priority.)

Figure 9

Student Subgroups to Be Included in Local Control and Accountability Plans

|

Racial/Ethnic Subgroups:

|

|

Black or African American

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

|

Asian

|

|

Filipino

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

|

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

|

|

White

|

|

Two or more races

|

|

Other Subgroups:

|

|

Socioeconomically disadvantaged students

|

|

English learners

|

|

Students with disabilities

|

|

Foster youth

|

Districts Must Specify Actions They Will Take to Achieve Goals. A district’s LCAP must specify the actions the district plans to take to achieve its annual goals. The specified actions must be aligned with the school district’s adopted budget. For example, a school district could specify that it intends to provide tutors to all EL students reading below grade level to improve its EL reclassification rate. To ensure the LCAP and adopted budget were aligned, the school district would be required to include sufficient funding for EL tutors in its adopted budget plan.

Districts Must Use SBE–Adopted LCAP Template. In preparing their LCAP, districts are required to use a template developed by SBE. The template is intended to create consistency in LCAPs across the state and assist school districts in developing their plans. The SBE is required to adopt the LCAP template by March 31, 2014.

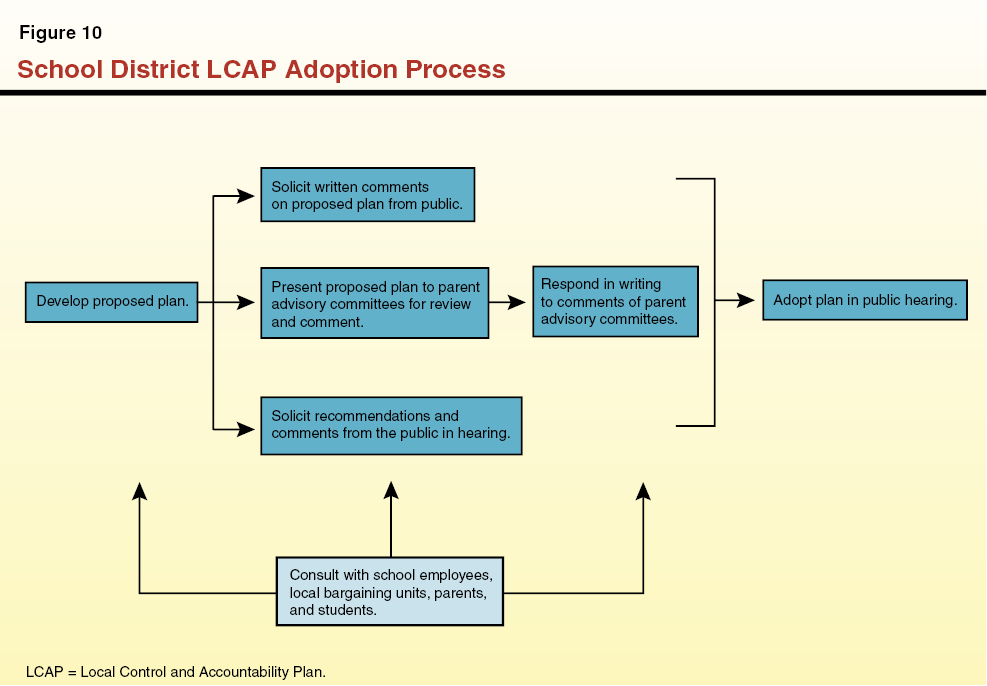

Districts Must Solicit Input From Various Stakeholders in Developing Plan. Figure 10 outlines the process a district must follow in adopting its LCAP. One of the main procedural requirements is that a district consults with its school employees, local bargaining units, parents, and students. As part of this consultation process, districts must present their proposed plans to a parent advisory committee and, in some cases, a separate EL parent advisory committee. (EL parent advisory committees are required only if ELs comprise at least 15 percent of the district’s enrollment and the district has at least 50 EL students.) The advisory committees can review and comment on the proposed plan. Districts must respond in writing to the comments of the advisory committees. Districts also are required to notify members of the public that they may submit written comments regarding the specific actions and expenditures proposed in the LCAP.

LCAP to Be Adopted Every Three Years And Updated Annually. Districts are required to adopt an LCAP by July 1, 2014 and every three years thereafter. In the interim years between adoptions, districts are required annually to update their LCAPs using the SBE template. Each year, districts must adopt (or update) their LCAPs prior to the adoption of their budget plans. Annual updates must review a school district’s progress towards meeting the goals set forth in its LCAP, assess the effectiveness of the specific actions taken toward achieving these goals, and describe any changes the district will make as a result of this review and assessment. The school district also must specify the expenditures for the next fiscal year that will be used to support EL/LI and foster youth students, as well as former ELs redesignated as English proficient. Districts also are required to hold at least two public hearings to discuss and adopt (or update) their LCAPs. The district must first hold at least one hearing to solicit recommendations and comments from the public regarding expenditures proposed in the plan. It then must adopt (or officially update) the LCAP at a subsequent hearing.

COE Review of District LCAPs

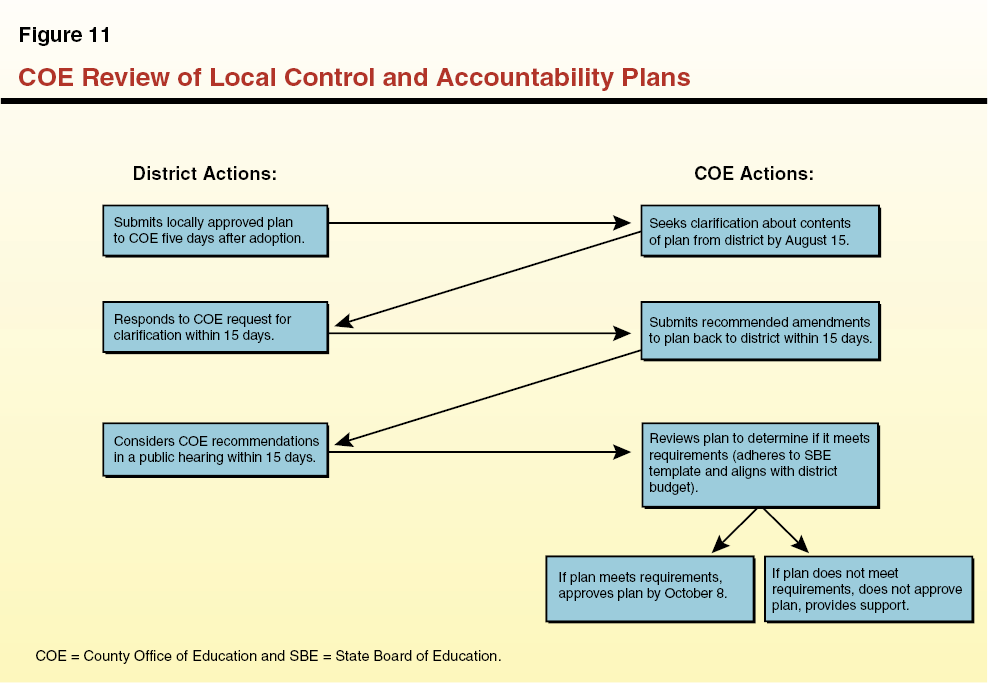

COE Can Ask for Clarification, Make Recommendations Regarding District LCAPs. Within five days of adopting (or updating) its LCAP, a district must submit its plan to its COE for review. Figure 11 displays the process of COE review. Before August 15 of each year, the COE can seek clarification in writing from the district about the contents of its LCAP. The district must respond to these requests within 15 days. Then, within 15 days of receiving the district’s response, the COE can submit recommendations for amendments to the LCAP back to the district. The district must consider the COE recommendations at a public hearing within 15 days, but the district is not required to make changes to its plan.

COE Must Approve LCAP if Three Conditions Are Met. The COE must approve a district’s LCAP by October 8 if it determines that (1) the plan adheres to the SBE template, (2) the district’s budgeted expenditures are sufficient to implement the strategies outlined in its LCAP, and (3) the LCAP adheres to the expenditure requirements for supplemental and concentration funding. As we discuss in the next section, districts whose LCAPs are not approved by the COE are required to receive additional support.

Support and Intervention

Chapter 47 also establishes a system of support and intervention for school districts that do not meet performance expectations for the eight state priority areas identified in the LCAP. Below, we discuss this new system in greater detail. (This system works somewhat differently for charter schools. We discuss the major differences in the box below.)

New System Works Somewhat Differently for Charter Schools

Chapter 47, Statutes of 2013 (AB 97, Committee on Budget) requires charter schools to adopt Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs), have their performance assessed using rubrics adopted by the State Board of Education (SBE), and receive support from its authorizer or the California Collaborative for Education Excellence (CCEE). The charter school process, however, works somewhat differently from the school district process. We describe the major differences below.

Charter School LCAP Adoption Process Different in Two Ways. Chapter 47 requires the petition for a charter school to include an LCAP that establishes goals for each of the eight state priorities (and any identified local priorities) and specifies the actions the charter school will take to meet these goals. The LCAP must be updated annually by the charter school’s governing board. Like school districts, charter schools are required to consult with school employees, parents, and students when developing their annual updates. The LCAP adoption process is different, however, in that charter schools are exempt from the specific requirements to solicit public comment and hold public hearings that apply to school districts. Charter schools also are not required to have their plans approved by the County Office of Education (COE).

Support Required for Persistently Failing Charter Schools. Like school districts, charter schools must have their performance assessed based on the new SBE rubrics. For charter schools, however, this assessment is to be conducted by the charter authorizer rather than the COE. A charter school is required to receive support from its authorizer if, based on the intervention rubric, it does not improve outcomes in three out of four consecutive school years for three or more subgroups in more than one state or local priority area—the same standard applied for determining whether the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI) intervention is necessary in a school district. (Unlike school districts, a charter school that is determined to be struggling based on the support rubric is not required to receive support.) In addition to the support from the charter authorizer, the SPI may assign the CCEE to provide the charter school with support if the authorizer requests and SBE approves the assistance. (If a charter school requests support but is not underperforming based on the intervention rubric, the charter authorizer and CCEE are not required to provide support.)

Instead of SPI Intervention, Charter Can Be Revoked by Authorizer. The charter authorizer can consider revoking a charter if the CCEE provides a charter school with support and determines that (1) the charter school has not been able or will not be able to implement CCEE recommendations and (2) the charter school’s performance is so persistently or severely poor that revocation is necessary. If the authorizer revokes a charter for one of these reasons, the decision is not subject to appeal. Consistent with current law, the authorizer must consider student academic achievement as the most important factor in determining whether to revoke the charter.

The SBE Also Can Revoke Charter or Take Other Actions Based on Poor Academic Performance. The SBE—based upon a recommendation from the SPI—also can revoke a charter or take other appropriate actions if the charter school fails to improve student outcomes across multiple state and local priority areas. (Prior to the adoption of Chapter 47, SBE could take similar action for charter schools only if the schools were (1) engaging in gross financial mismanagement, (2) illegally or improperly using funds, or (3) implementing instructional practices that substantially departed from measurably successful practices and jeopardized the educational development of students.)

New Rubrics to Determine if Districts Need Support or Intervention

COE Must Assess School District Performance Based on SBE–Adopted Rubrics. As shown in Figure 12, SBE must develop three new rubrics for assessing a school district’s performance. The SBE is to adopt all three rubrics by October 1, 2015. The rubrics are to be holistic and consider multiple measures of district and school performance as well as set expectations for improvement for each numerically significant subgroup in each of the eight state priority areas.

Figure 12

State Board of Education (SBE) Required to Adopt Three New Rubrics

|

|

|

Chapter 47, Statutes of 2013 (AB 97, Committee on Budget) requires SBE to develop and adopt the following three evaluation rubrics by October 1, 2015.

|

- Self–Assessment Rubric. This rubric is to assist districts in evaluating their strengths and weaknesses.

|

- Support Rubric. This rubric is to be used by COEs to determine if a school district does not improve outcomes in more than one state priority for at least one subgroup, and thus is required to receive some form of support.

|

- Intervention Rubric. This rubric is to be used by the SPI to determine if a district does not improve outcomes in three out of four consecutive school years for three or more subgroups in more than one state or local priority, and thus is considered to be persistently failing.

|

Support for Struggling School Districts

Three Reasons Districts Can Be Flagged for Additional Support. School districts are required to receive additional support in the following three instances.

- LCAP Not Approved by COE. A district is required to receive support if its LCAP is not approved by the COE because it does not follow the SBE template or is not aligned with the district’s budget plan.

- District Requests Assistance. A district may specifically request additional support.

- District Not Improving Student Outcomes. A district must receive support if, based on the support rubric, it does not improve outcomes in more than one state priority area for at least one subgroup.

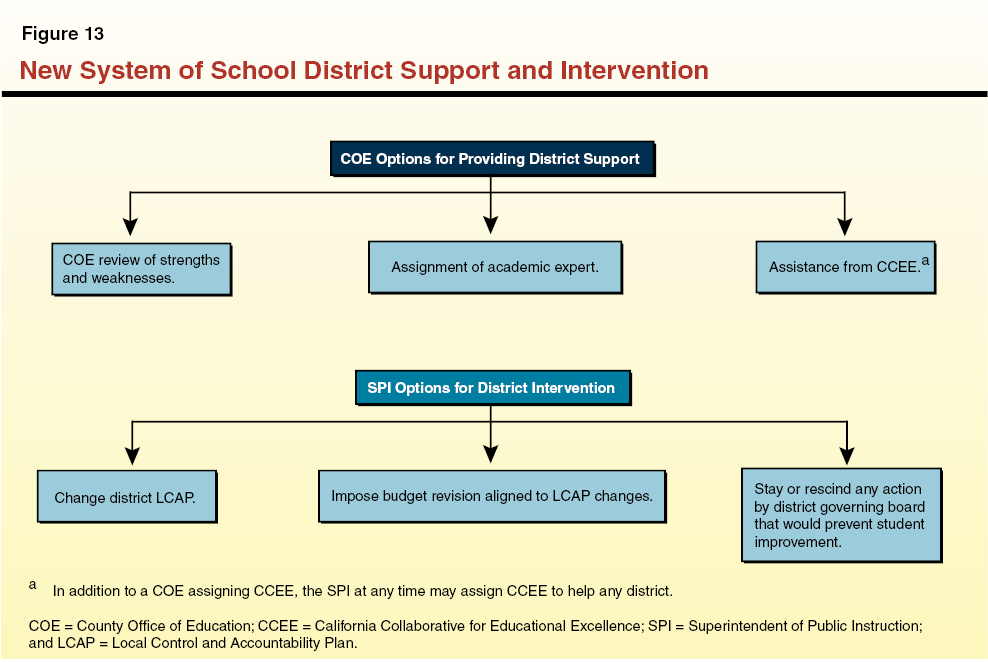

Three Forms of Support. Under the new system, COEs are responsible for providing school districts with certain types of support. As Figure 13 shows, COEs can provide three types of support.

- COE Review of Strengths and Weaknesses. The COE can deliver assistance by providing a written review of the district’s strengths and weaknesses in the eight state priority areas. The COE review also must identify evidence–based programs that could be used by the school district to meet its annual goals.

- Assign an Academic Expert. The COE can assign an academic expert or team of experts to assist the district in implementing effective programs that are likely to improve outcomes in the eight areas of state priority. The COE also can assign another school district within the county to serve as a partner for the school district in need of assistance.

- Request Assistance From Newly Established Agency. The COE can request that the SPI assign the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE), a newly established agency, to provide assistance to the school district. (We discuss the role of the CCEE in more detail in the box below.)

New Agency to Support Struggling Districts

Legislation Establishes California Collaborative for Educational Excellence. Chapter 47, Statutes of 2013 (AB 97, Committee on Budget), creates a new agency, the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE), to advise and assist school districts in improving performance. Chapter 357, Statutes of 2013 (SB 97, Committee on Budget), establishes a CCEE governing board consisting of five members: (1) the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI), (2) the president of the State Board of Education (SBE), (3) a county superintendent of schools appointed by the Senate Committee on Rules, (4) a teacher appointed by the Speaker of the Assembly, and (5) a school district superintendent appointed by the Governor. The SPI, with approval from the SBE, is required to contract with a local education agency (LEA) or consortium of LEAs to serve as the fiscal agent for the CCEE. The fiscal agent, under the direction of the CCEE board, is to subcontract with individuals, LEAs, and other organizations to provide direct support to districts.

CCEE Charged With Helping Districts Improve Performance. Statute requires the CCEE to serve as a statewide expert to help districts: (1) improve their achievement in the eight state priority areas, (2) enhance the quality of teaching, (3) improve district/school–site leadership, and (4) address the needs of special student populations (such as English learner, low–income, foster youth, and special education students). In particular, the CCEE is intended to help districts achieve the goals set forth in their Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAPs).

CCEE Can Intervene in Specific Cases. The CCEE is involved in turnaround efforts in three ways:

- A county office of education (COE) can assign the CCEE to provide assistance to school districts that have an LCAP rejected, request assistance, or are determined in need of assistance based on the COE’s assessment using the support rubric.

- The SPI can assign the CCEE to provide assistance to any school district that the SPI determines needs help to accomplish the goals set forth in its LCAP.

- The CCEE also is required to play a critical role in determining when the state will intervene in a persistently failing school district. If the SPI, with approval of the SBE, would like to intervene in a persistently failing school district, he or she cannot do so unless the CCEE has provided assistance to the district and determined that intervention is necessary to improve the district’s performance.

Intervention in Persistently Failing School Districts

SPI Can Intervene in Select Cases. For a persistently underperforming school district, the SPI can intervene to assist the district in improving its education outcomes. The SPI can intervene, however, only if all three of the following conditions are met.

- Persistent Failure for Several Years. The SPI can intervene if, based on the intervention rubric, the district does not improve outcomes in three out of four consecutive school years for three or more subgroups in more than one state or local priority area.

- CCEE Determines Intervention Is Necessary. The SPI can intervene if the CCEE has provided assistance and determines both that (1) the district has not been able or will not be able to implement CCEE recommendations and (2) the district’s performance is so persistently or severely poor that SPI intervention is necessary.

- SBE Approves Intervention. The SPI can intervene only with approval of SBE.

Provides Three New Powers to SPI. If the above conditions are met, the SPI can intervene directly or assign an academic trustee to work on his or her behalf. The SPI can intervene in the following three ways.

- Change District LCAP. The SPI can change the district’s LCAP to modify the district’s annual goals or the specific actions the district will take to achieve its goals.

- Impose Budget Revision in Conjunction With LCAP Changes. The SPI can impose a revision to the district’s budget to align the district’s spending plan with the changes made to the LCAP. These changes only can be made if the SPI determines they will allow the district to improve outcomes for all student subgroups in one or more of the eight state priorities.

- Stay or Rescind an Action of the Local Governing Board. The SPI also can stay or rescind an action of the district governing board if he or she determines the action would make improving student outcomes in the eight state priority areas, or in any of the district’s local priority areas, more difficult. The SPI, however, cannot stay or rescind an action that is required by a local collective bargaining agreement.

Major Decisions Ahead

Many important state and district decisions relating to the new formula and the new system of support and intervention will be made over the next several years. Figure 14 identifies the major milestones ahead. Below, we discuss some of these major decisions in more detail.

Many Major Regulations to Be Adopted by SBE. Over the next several years, SBE must adopt numerous regulations relating to the LCFF and the new system of support and intervention. As the timeline shows, by January 31, 2014, SBE must adopt regulations to implement the proportionality clause relating to LCFF supplemental and concentration funds. Two months later, by March 31, 2014, it must adopt LCAP templates for districts to use in developing their 2014–15 LCAPs. By October 1, 2015, SBE must adopt the three rubrics that will be used to assess school districts’ performance. The details of these regulations will significantly affect the manner in which these new provisions are ultimately implemented.

CCEE’s Larger Role in New System Remains Unclear. Although Chapter 357 clarifies the governance structure of the CCEE, its larger role within the state’s accountability system remains unclear. The CCEE fiscal agent has the authority to contract with individuals and organizations with expertise and a record of success in the CCEE’s assigned areas of responsibility. The legislation, however, does not specify the process the CCEE should take to identify agencies with expertise or how the role of these agencies would differ from the role of other agencies, including District Assistance and Intervention Teams and the Statewide System of School Support, that currently provide assistance to low–performing schools and districts.

New Agency’s Prominence and Workload Uncertain. Given the many elements of the new system of support and intervention that are yet to be developed and implemented, the CCEE’s workload also remains unclear. The CCEE’s workload will be driven partly by the number of districts determined in need of support or assistance. The number of districts that will need such support, however, will not be known until the SBE rubrics are adopted and districts are evaluated based on these rubrics. Because under state law most of the CCEE’s activities will be driven by specific requests from school districts, COEs, and the SPI, the CCEE’s role in the new system also will be determined by the agency’s reputation as a statewide expert in improving educational programs. To the extent that districts, COEs, and the SPI consider the CCEE a key agency for helping to improve school performance, the agency will have a more prominent role advising districts.

Cost of CCEE Also Unclear. Because of the significant uncertainty regarding the level of workload of the CCEE, its associated costs are unknown at this time. The 2013–14 budget provides $10 million for the CCEE but includes little detail on how and when the funds are to be spent. The annual cost of the CCEE ultimately will depend on the composition of the CCEE; the number of school districts determined to need support or intervention; and the frequency with which school districts, COEs, and the SPI request assistance from the CCEE.

Conclusion

The creation of the LCFF addresses many of the flaws of the state’s prior K–12 funding system, which was widely believed to be overly complex, inefficient, and outdated. The LCFF, for instance, is much simpler when compared with the dozens of categorical funding formulas that were part of the state’s previous funding system. The new system of funding and accountability, including the provisions dealing with the LCAPs, also is intended to reduce some spending requirements while giving districts more guidance in developing fiscal and academic plans designed to improve performance in their local context. As evident throughout this report, both the LCFF and the new system of support and intervention represent major state policy changes. Moreover, in the coming months and years, the Legislature, SBE, and school districts will face many decisions that ultimately will shape how the formula and new accountability system are implemented, which, in turn, will determine the effectiveness of the legislation.