Introduction

As part of the 2011–12 budget package, California adopted new eligibility standards for colleges participating in the Cal Grant programs. Based on the changes, colleges with a substantial proportion of students taking out federal student loans and a high percentage of those borrowers defaulting no longer qualify to participate. The 2012–13 budget package tightened the loan default limit and added a minimum graduation rate that colleges must meet to remain eligible. The effects of these new rules were difficult to predict because they would depend in part on how students and colleges responded to the changes. Consequently, the Legislature directed our office to submit a report in January 2013 on implementation of the new policies. The Legislature also requested that we make recommendations for how best to measure the quality or effectiveness of educational institutions participating in the Cal Grant programs.

Below, we first provide some background information on the concerns about institutional quality that led to the recent eligibility changes. We then describe the implementation of the new standards and their effects on students, institutions, and the state budget. Lastly, we offer recommendations for eligibility standards and implementation changes that would better protect student and state interests.

Background

Cal Grant Is State’s Primary Student Aid Program. The state’s main Cal Grant program guarantees financial aid awards to recent high school graduates and community college transfer students who meet financial, academic, and other eligibility criteria. The state also provides a relatively small number of competitive grants to students who do not qualify for entitlement awards. Cal Grants cover full systemwide tuition at the public universities for up to four years and partly contribute to tuition costs at nonpublic institutions. Apart from tuition grants, some students qualify for grants that cover a portion of their living costs. Altogether, the state awards more than 340,000 Cal Grants annually.

Existing Minimum Institutional Standards Retained. Even prior to the 2011 changes, schools had to meet minimum standards to participate in Cal Grant programs. These standards remain in place alongside the new restrictions. To qualify, an institution must be one of the following:

-

A California public postsecondary educational institution.

-

A California nonprofit institution headquartered and operating in California and accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges that demonstrates administrative capability (including policies, procedures, systems, and personnel) and certifies that 10 percent of its operating budget is expended for institutionally funded student financial aid grants.

-

A California institution that participates in the federal Pell Grant program and at least two of three specified federal campus–based aid programs (federal work–study, Perkins Loan, and Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant programs). To participate in these programs, an institution must meet federal standards that include state approval to operate (or state exemption from approval requirements), accreditation by a federally recognized accrediting agency, minimum admission standards (such as requiring high school graduation or its equivalent), and various standards of financial responsibility and administrative capability. In addition, schools must maintain student loan default rates below specified levels. (See nearby box for explanation of default rates.)

Student Loan Default Rates and Federal Student Aid

Measuring Cohort Default Rates. Federal student loan cohort default rates are measured from the time a borrower’s loan enters the repayment period (usually six months after graduation or leaving school) for a period of two or three federal fiscal years. A borrower whose loan entered repayment any time during the 2008–09 federal fiscal year is counted in the official two–year cohort default rate for 2009 if the borrower defaults on the loan before the end of the 2009–10 fiscal year. Although the definition of default varies by type of loan, it generally means that the loan has been delinquent (that is, at least one missed payment remains outstanding) for at least 360 days in the two–year period.

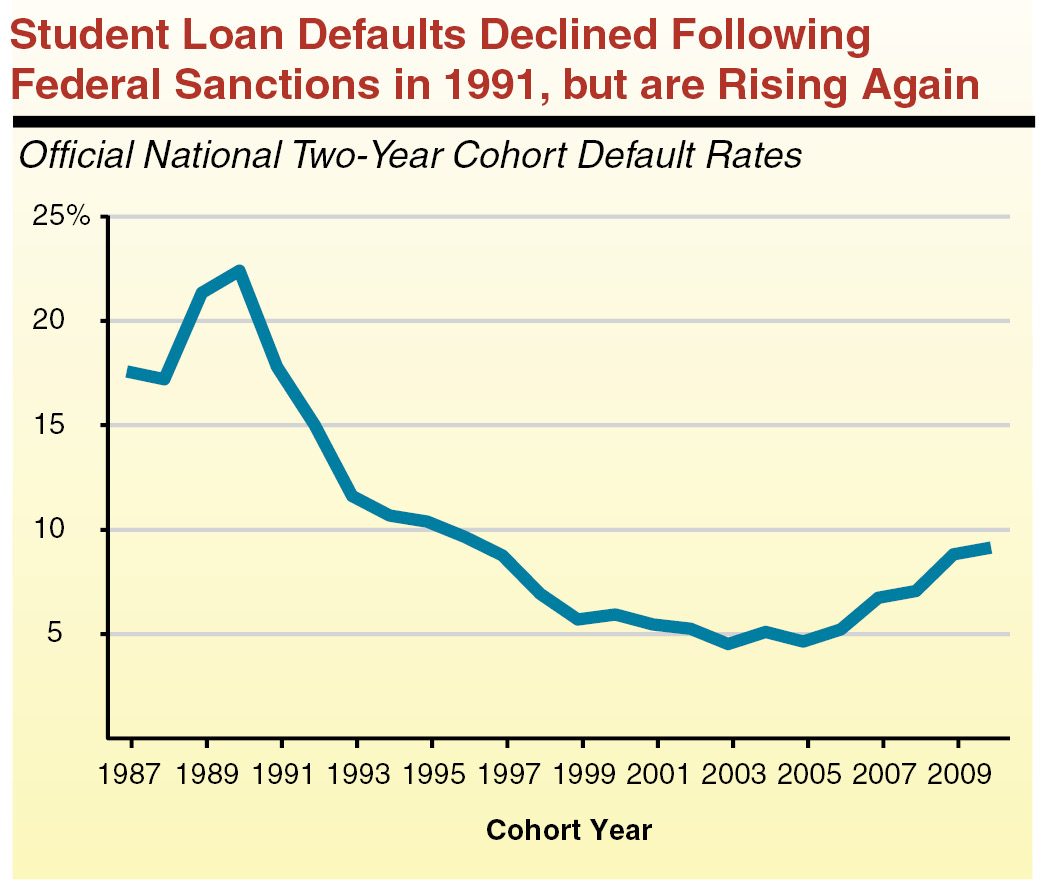

Defaults Peaked in 1980s . . . In the late 1980s, the U.S. Department of Education grew concerned about increasing student loan default costs. The growing default volume was largely attributed to rapid expansion of private trade schools that were recruiting many unprepared students, often without providing a useful education leading to gainful employment. One federal study found about 1,200 schools with default rates greater than 40 percent. While student loan volume nearly tripled in the 1980s, federal default payments increased 16–fold.

. . . Prompting New Policies. Congress imposed sanctions on schools with high default rates beginning in 1991. Schools with two–year cohort default rates exceeding 40 percent in any one year were excluded from participation in federal student loan programs. Those with rates exceeding 25 percent for three consecutive years lost eligibility for Pell Grants as well as loan programs. The new policy eliminated more than 1,200 high–default schools over the next several years and reduced aggregate default rates from a high of more than 22 percent for the 1990 cohort to a low of 4.5 percent by 2003. The figure below shows the history of two–year cohort default rates over this period.

New Default Measure Effective in 2012. Default rates began to rise again in the mid–2000s with the expansion of for–profit education. In addition, federal regulators were concerned about strategies employed by institutions and lenders to delay defaults just beyond the two–year period used to calculate official rates. As part of the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008, Congress lengthened the operative default period from two to three years, beginning with the cohort of borrowers entering repayment in 2008–09. The change increased the aggregate default rate for public and nonprofit institutions by slightly more than 50 percent and nearly doubled the rate for for–profit schools. To partly compensate for the longer default period, the department changed the threshold for sanctions from a default rate of 25 percent to 30 percent for three consecutive years (or 40 percent in any one year). Sanctions based on the three–year rates are to be imposed beginning in 2014. Based on current rates, more than 250 schools would face potential sanctions.

Policymakers Concerned About Institutional Effectiveness

In recent years, a number of highly critical national news stories and a major congressional investigation of for–profit education companies have raised concerns about student outcomes at for–profit colleges. These investigations highlighted misleading recruitment practices, poor completion rates, and high student debt among for–profit education students. Some of the institutions implicated in these reports participate in the Cal Grant programs, prompting concern that state funds may be encouraging some California students to attend poorly performing schools. Although Congress strengthened standards in 2008, state lawmakers questioned whether the new requirements went far enough.

Budget Concerns Also a Factor. At the same time these investigations were uncovering evidence of questionable practices at for–profit colleges, the state was facing a substantial structural budget deficit. Moreover, Cal Grant costs doubled between 2006–07 and 2011–12—growing faster than all other major areas of state government. For all these reasons, the Governor and Legislature sought ways to stem growth in Cal Grant costs while addressing their concerns about the quality of some participating colleges.

Legislature Enacts Tougher Institutional Eligibility Standards

The Legislature enacted Chapter 7, Statutes of 2011 (SB 70, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), and Chapter 38, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1016, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), limiting institutional participation in Cal Grant programs. In both years, the legislation was part of the budget package. These changes marked the first reductions in institutional eligibility since the inception of Cal Grants in 1976.

The 2011–12 Budget Package. Chapter 7 established a student loan default rate limit for colleges seeking to participate in the Cal Grant programs. Institutions had to maintain three–year cohort default rates below 24.6 percent to remain eligible in 2011–12, with a rate below 30 percent thereafter. This new eligibility standard applied only to institutions with 40 percent or more of their undergraduates borrowing federal student loans (effectively exempting all community colleges). For transitional purposes, Chapter 7 also specified that continuing students at newly ineligible institutions still could qualify for renewal awards, though the award amounts were reduced by 20 percent. In addition, Chapter 7 required all colleges participating in the Cal Grant programs to provide data on certain student outcomes, including graduation rates, employment rates, and graduate earnings.

The 2012–13 Budget Package. Chapter 38 reduced the allowable default rate and added a minimum graduation rate. Beginning in 2012–13, institutions must maintain cohort default rates below 15.5 percent and graduation rates above 30 percent to remain eligible. While the legislation continued the exemption for institutions with less than 40 percent of undergraduates borrowing, it ended the exception for renewal awards beginning in 2013–14. As a result, recipients at ineligible institutions will have to transfer to eligible ones to continue using their Cal Grant awards. The budget package also reduced maximum Cal Grant award amounts for students at nonpublic institutions. Maximum awards will decline 17 percent by 2014–15 for students at nonprofit institutions, and 59 percent by 2013–14 for students at for–profit institutions. The Appendix contains sections of the revised Cal Grant statute incorporating the combined changes in Chapters 7 and 38.

Implementation To Date

First–Year Implementation

Ineligible Institutions Quickly Identified. The Governor signed Chapter 7 on March 24, 2011 establishing the cohort default rate limit at 24.6 percent. Within about two weeks, CSAC certified the three–year cohort default rates of all participating schools and notified the top administrative official at each ineligible school by letter. Because the U.S. Department of Education had not yet published official three–year cohort default rates, CSAC used unofficial 2008 trial three–year rates.

Students Admitted to/Attending Ineligible Institutions Quickly Identified, Some Backtracking Required. By the time the new restrictions became law, CSAC already had begun awarding grants for the 2011–12 academic year. Some of these grants were to new students at newly ineligible institutions. In early May, CSAC staff sent letters and e–mail messages to these students, advising them that they would need to transfer to eligible schools to receive their Cal Grant awards. The commission also notified continuing students at ineligible schools that their awards would be reduced by 20 percent.

Commission Notified Financial Aid and Counseling Communities, Updated Grant Delivery System. In the first months of implementation, CSAC notified college financial aid administrators and high school counselors of the changes in the law. It also compiled a list of frequently asked questions to post on its website and distribute to the financial aid and counseling community. In addition, the commission updated its automated Grant Delivery System to display cohort default rates, identify ineligible institutions, prevent new awards at these schools, and reduce renewal awards at these schools by 20 percent. Commission staff conducted two webinar training sessions with campus financial aid administrators regarding the eligibility and system changes.

Certification for 2012–13 Initially Expanded Eligibility. The commission certified institutions’ three–year cohort default rates for the 2012–13 academic year by October 1, 2011, as required by the new law. Because the U.S. Department of Education had not yet published official three–year cohort default rates, the 2008 trial rates CSAC had used for the previous certification were still in effect. Although the rates did not change, the threshold for institutional eligibility moved from 24.6 percent to 30 percent, reducing the number of institutions deemed ineligible for Cal Grant participation by nearly half. The commission published a new list of ineligible institutions based on these factors.

Second–Year Implementation Under New Rules

Revised Standard for 2012–13 Substantially Reduced Number of Eligible Institutions. Following the 2012 changes to the law which reduced the default threshold from 30 percent to 15.5 percent, CSAC revised its list of ineligible schools. Once again, some institutions that were initially deemed eligible (based on the 2011 legislation) were disqualified after grants already were awarded to students at those institutions. Commission staff repeated the implementation steps from the prior year, notifying school officials, students, college financial aid administrators, and high school counselors of the eligibility changes and their implications, completing this process in August 2012.

Certification for 2013–14 Raises Some Concerns. Chapter 38 requires CSAC to certify institutional eligibility by October 1 each year. This date was selected to follow the U.S. Department of Education’s publication of cohort default rates, which by federal law must be completed by September 30 each year. When the Legislature added the minimum graduation rate, it left the same certification date in place. There is no statutory requirement, however, for the U.S. Department of Education to publish graduation rates by the same date. The department released the latest (2011) graduation rates through its College Navigator website on July 5, 2012. This is a website designed to deliver consumer information about postsecondary institutions. The department did not release the 2011 graduation rates through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) website (which is designed for research and policy purposes and was the source for the current year’s certifications) until October 9, more than a week after CSAC’s deadline for certifying the rates. The primary difference between the rates released through IPEDS and those published earlier on College Navigator is that IPEDS includes estimates for schools that did not report their actual rates for a given year. Because CSAC used the most recent data available on IPEDS, it applied the 2010 rates to determine eligibility for both the 2012–13 and 2013–14 award cycles. As a result, ten institutions remained ineligible despite having improved their graduation rates. Conversely, seven schools that would have lost eligibility using the new rates remained eligible. According to IPEDS officials, the department expects to release graduation rates on both the College Navigator and IPEDS websites in early October going forward.

Several Institutions Have Appealed CSAC’s Eligibility Determination. Six schools have filed appeals challenging their loss of eligibility. The commission has denied each of these appeals, noting that it is required by law to certify the latest rates published by the U.S. Department of Education. Two of the challenges are being litigated.

Identifying the Effects of Recent Changes

In this section, we describe the immediate effects of the new eligibility standards on students, schools, and the budget. As noted at the end of the section, determining the longer–term effectiveness of this policy will take more time.

Students

More Than 2,500 New Cal Grant Recipients Did Not Use Their Awards in 2011–12. Preliminary information shows that about 3,200 students who were offered new Cal Grant awards for 2011–12 were initially planning to attend schools that later were deemed ineligible, almost all of them for–profit schools. About 550 (18 percent) of these students instead attended eligible schools, primarily shifting to other for–profits or the California Community Colleges (CCC). Another 450 students (14 percent) requested leaves of absence from the Cal Grant program, preserving their awards for later use rather than claiming them. The remaining 2,200 students (68 percent) did not claim their Cal Grants, and we have no information concerning their college attendance. They may have opted to attend an ineligible California institution without Cal Grant support, decided not to go to college, or transferred to an out–of–state school. Normally, not all students who are offered initial awards actually claim them. The proportion of recipients claiming awards—which differs by institutional sector and type of award—is called the take rate. Accounting for the take rate, it appears that at least 1,000 students who would normally have used their awards in 2011–12 did not do so. (If the Legislature would like a more complete picture of the new policy’s initial impact on these students, it could direct CSAC to work with the National Student Clearinghouse service to track their attendance patterns.)

Less Effect on Students Renewing Awards. Preliminary information also indicates that of about 1,700 students attending ineligible schools who were offered renewal awards for 2011–12, about 60 percent remained at their schools and received a reduced award, 9 percent transferred to eligible colleges, and another 4 percent took leaves of absence. No further information is available about more than one–quarter of the renewal recipients at ineligible schools.

Commission Has Not Provided Data for 2012–13. Initial projections suggested that about 7,600 new recipients and 5,600 renewal recipients would be affected by the new policy, after accounting for the take rate. Despite repeated requests, CSAC has not provided information to the Legislature regarding the actual numbers affected to date.

Changes Reduce Student Choices. The new policies disqualified many schools (see next section) that historically have served Cal Grant recipients. Consequently, these recipients now have fewer options for using their Cal Grant awards. Students’ choices are most constrained in the for–profit sector, where a large majority of schools were disqualified. This reduction in for–profit eligibility coincides with enrollment restrictions in the public sector. At California State University (CSU), 16 of 23 campuses are impacted and do not admit all fully qualified applicants. Even at the remaining seven CSU campuses, some majors are oversubscribed. Both CSU and CCC have been unable to meet all student demand for courses, slowing progress toward completion for some students. The combination of these factors exacerbates the impact of the new measures on student choices.

Nontraditional and Disadvantaged Students Particularly Affected. Compared to the public and nonprofit sectors, the for–profit segment as a whole serves students who tend to be older and are more likely to be financially independent from parents, financially responsible for dependents, and from a racial or ethnic minority group. For–profit students are also more likely to have below–average income and parents with no postsecondary education. Several of these factors make students more likely to drop out of school and default on student loans. Because the new standards primarily exclude for–profit institutions from Cal Grant participation, these students are disproportionately affected.

Postsecondary Institutions

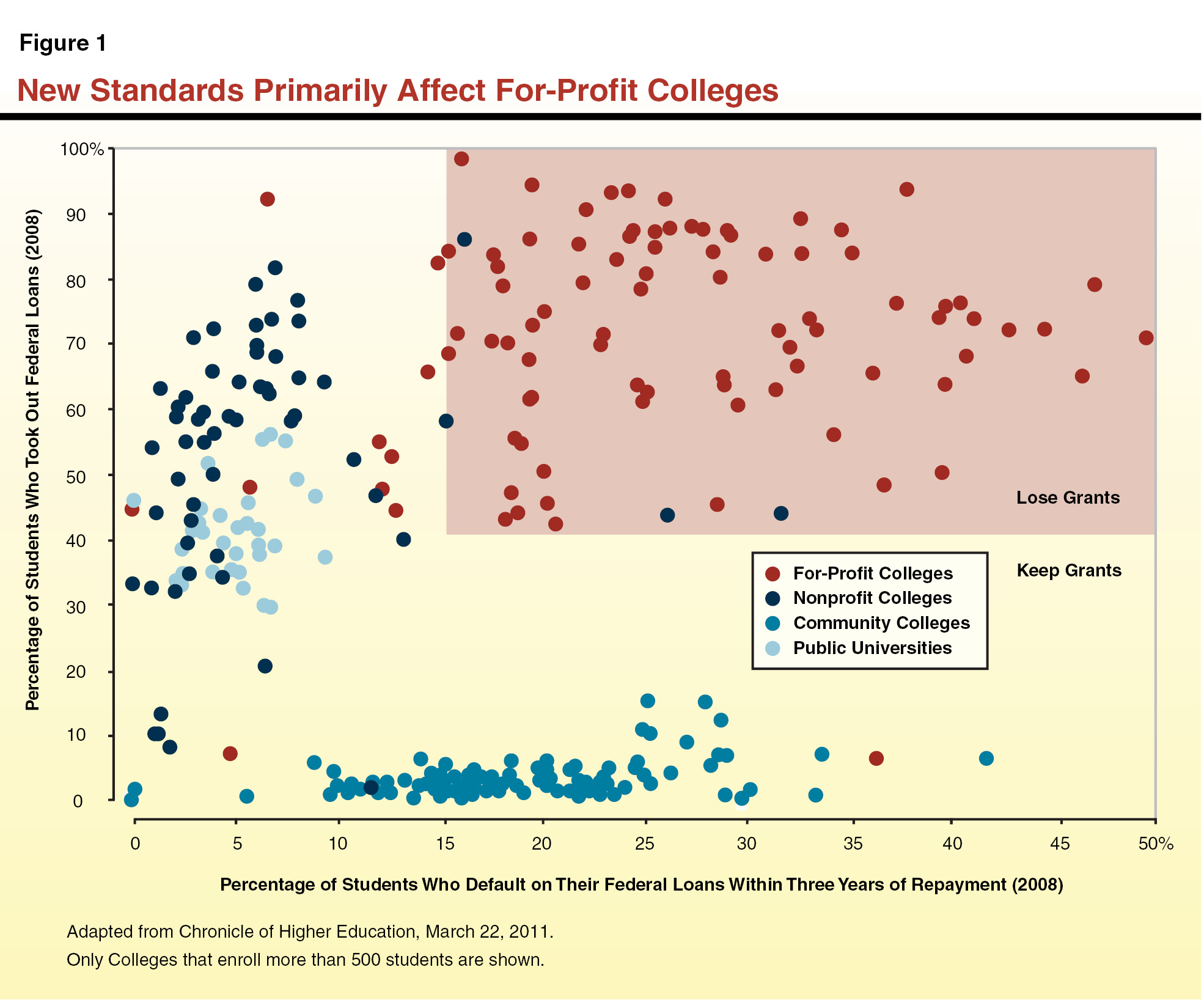

Most For–Profit Schools Disqualified. Applying the eligibility standards in Chapter 7, CSAC identified 76 schools as ineligible for 2011–12, 42 of which would remain ineligible for 2012–13. Following enactment of Chapter 38’s stricter standards, CSAC revised the list of ineligible institutions for 2012–13 to include 154 schools, comprising 35 percent of all institutions—and more than 80 percent of for–profit schools—participating in the Cal Grant programs in recent years. The rule changes had limited impact on the private nonprofit sector and no impact on the public sector, as shown Figure 1.

Each dot in the figure depicts a Cal Grant participating school with enrollment of at least 500 students. Its location on the graph represents both the proportion of students borrowing federal student loans and the cohort default rate for the school. Schools with high borrowing and default rates are in the top right region of the figure. The highlighted area represents the range in which schools are ineligible to participate in Cal Grants—those with more than 40 percent of students having federal loans and having default rates of 15.5 percent and above. (The figure does not address the graduation rate standard, which is a separate, additional eligibility requirement.) All but three of the institutions in the highlighted range are for–profit schools, depicted by red dots. (The three are nonprofit schools, shown as dark blue dots.) Most nonprofit schools have moderate to high borrowing rates but low default rates. All public universities, depicted in light blue, have moderate proportions of students borrowing and low default rates, while the community colleges, shown at the bottom of the figure, have low borrowing rates and a range of default rates.

State Budget

Savings on Target for 2011–12. General Fund savings from the default rate standard in 2011–12 were initially projected at $24 million, and adjusted down to $10.7 million before the budget was finalized. The erosion was due in part to the U.S. Department of Education’s default rate corrections, resulting in lower rates and fewer ineligible schools than originally identified. Based on information provided in February 2012, savings were on track to meet the new target. The commision has not provided requested data on the final savings amount.

Savings Falling Short for 2012–13. Savings for 2012–13 were projected at $55 million. Early indications are that savings will fall at least $5 million short of that target. However, CSAC has not provided requested data to the Legislature to update estimated savings.

Longer–Term Effects

While the immediate impact on student awards, institutions, and budget savings will be apparent once more data become available, the longer–term effects will be more difficult to discern. This is because they depend to a large extent on how students and institutions adapt to the new rules. Overall, we believe the impacts will diminish as new students seek enrollment at eligible institutions, eligible institutions expand to meet demand, and ineligible institutions take steps to improve their student outcomes and regain eligibility.

Assessment and Recommendations

In this section, we recommend the Legislature maintain the current eligibility standards in the near term. Moving forward, we recommend the Legislature continue to monitor the effects of the recent changes and begin exploring various alternative measures of institutional quality. We also recommend the Legislature make a few specific changes to the process.

Maintain Default Risk Measures, But Consider Refinements in Future

No broad agreement exists on direct, quantifiable measures of institutional quality. Absent such measures, student outcomes including default rates and graduation rates provide rough proxies for how well an institution is serving students. The current Cal Grant eligibility standards, however, have three notable drawbacks. One drawback is that institutions can manipulate cohort default rates. Another drawback is that the current standards exempt some institutions without strong justification for doing so. A third drawback is that the measures penalize institutions that serve more disadvantaged students. These drawbacks, as well as ways to address them, are discussed in more detail below.

Institutions Can Manipulate Cohort Default Rates

A recent federal investigation and related analyses have found that many for–profit schools employ extensive “default management” strategies to keep their cohort default rates below federal thresholds. Some of these strategies, including forbearance and deferment, permit students to delay payments without being deemed in default. In these cases, most students end up increasing their total debt and likely would be better served by repayment counseling or alternative repayment plans. Another default management strategy involves combining campuses of multi–site institutions in ways that minimize the aggregate default rate. A third strategy increasingly used by schools is directing students to private student loans, which usually have less beneficial terms and conditions than federal loans but are not included in schools’ federal default rate calculations.

Recommend Legislature Explore Two Alternative Debt Measures . . . Because of increasing concern about institutions manipulating their cohort default rates, the U.S. Department of Education has developed alternative debt measures, including a repayment rate and debt–to–earnings ratio. In both cases, the measures appear to be less susceptible to manipulation. The repayment rate counts the proportion of former students making at least partial payments on their loans. By comparison, the earnings ratio, calculated with Social Security earnings data, provides a gauge of graduates’ ability to repay their loans. The earnings ratio is calculated for each instructional program (rather than the entire institution). It compares the average annual loan repayment owed by students who completed a program with those students’ average annual earnings. (The measure includes private loan debt, when that information is known.) For now, a federal court has blocked implementation of the regulations that require institutions to report data for these two measures. If the federal reporting requirements are reinstated, we recommend California consider using these alternative measures instead of the cohort default rate for determining Cal Grant program eligibility.

Moving forward, even these better alternative measures likely could be further refined. For example, if more detailed repayment data become available in the future, California might be able to use a repayment measure that identifies the proportion of students who are substantially current on their loan repayment—a notably better indicator than the proportion of students making $1 or more of repayments. Such refinements in the measures would provide even more useful information to both policymakers and students comparing colleges.

. . . But Maintain Cohort Default Rate Measure for Now. Until these data are readily available, however, we recommend continued use of the cohort default rate as a proxy for institutional quality. In the absence of federal data, California would have considerable difficulty directly collecting the information—including annual loan obligations and earnings data—necessary to calculate these more nuanced rates, especially at the program level.

Weak Justification for Exempting Some Schools

Another drawback of the existing system is that it exempts some schools from the new standards without strong justification. Specifically, the graduation rate requirement applies only to schools with more than 40 percent of students borrowing federal loans. In effect, this policy excludes community colleges from the graduation rate requirement because low student fees, a high proportion of part–time and working students, and an extensive fee waiver program result in few community college students borrowing. The policy justification, however, for linking the borrowing and graduation rate standards is unclear. If a minimum graduation rate requirement is intended to measure institutional quality, then applying it only to some institutions is at best awkward. Regardless of the share of students borrowing, a graduation rate could provide the Legislature with additional information about effectiveness.

Apply Graduation Standard to All Schools—But Focus Only on Graduation of Cal Grant Recipients. We recommend the Legislature apply the graduation rate requirement to all Cal Grant institutions but refine the measure to focus only on the graduation rate of Cal Grant recipients. Cal Grant programs are reserved for students working toward degrees and certificates. For example, a student must be enrolled in a two–year or four–year program leading to a degree to receive a Cal Grant A and in a degree or certificate program of at least one year for a Cal Grant B. Measuring graduation rates for these students—while avoiding the measurement challenges of accounting for the many community college students pursuing different goals—would provide a reasonable assessment of whether institutions are providing value for the state’s Cal Grant investment.

Measures Do Not Account for Differences in Students Served

A third drawback of some existing measures of institutional quality is that they fail to take into consideration characteristics of schools’ students. For example, open access institutions have poorer student outcomes than selective ones because they do not limit admission to students who are academically well prepared. This is evident in the default rates for community colleges shown in Figure 1, which overlap substantially with those of equally nonselective for–profit institutions. It is also evident in graduation rates for open–access institutions. As a result, these measures could create a disincentive for institutions to serve disadvantaged students.

Take Into Consideration Student Population Served. Certain analytic approaches are able to tease out an institution’s impact on student outcomes by comparing it with other institutions serving similar students. Given such analytical tools increasingly are available, we recommend the Legislature consider adjusting default rates, graduation rates, and other outcome measures for students’ characteristics (including their financial need and level of academic preparation). While we believe maintaining some limit for default rates is reasonable, the current limit of 15.5 percent may be too strict for a school serving primarily disadvantaged students. At the same time, this standard may be too lax for a school with less disadvantaged, more academically prepared students. The Legislature could use the results of the more sophisticated calculations that control for underlying student characteristics to provide an exception for schools that do not meet the limit but significantly outperform peer institutions.

Explore Other Proxies for Quality

New Cal Grant Reporting Requirements Need More Work, but Could Be Considered in Future. Chapter 7 created new reporting requirements for Cal Grant–participating institutions, including disclosure of enrollment, persistence, and graduation data for all students and separately for Cal Grant recipients, as well as job placement and earnings data by program. The commission is in the process of developing regulations for reporting these data, including definitions and time frames. The purpose of these new disclosure requirements is to give prospective students information that will help them choose schools. We have already discussed using graduation rates for Cal Grant recipients in determining school eligibility. Some of the other new measures also could be used for this purpose in the future. Overall data could be used as a proxy for institutional quality, and outcome data for Cal Grant recipients could be used to monitor the state’s investment in these students. At this time, however, we do not recommend considering these additional measures for eligibility determination because CSAC is still refining the definitions for the measures and schools have not completed any reporting cycles. In addition, information on some of these outcomes already is publicly available from federal, state, and institutional sources, but the specific measures differ. Until there is broader agreement about how these outcomes should be measured, we do not recommend using them to determine school eligibility. Moving forward, however, these other measures likely will become more viable options for assessing institutional quality.

Consider Variations on Federal 90/10 Rule. Another federal standard the state could consider measures institutions’ dependence on public funding. This measure, known as the 90/10 rule, requires for–profit colleges to get at least 10 percent of their revenue from sources other than Title IV federal student aid (which includes federal grants, loans, and work–study funds). Other sources include tuition paid by students, state and private financial aid, and some federal aid including veterans’ education benefits. The measure shows whether other payers, including students, think the school provides sufficient value to justify their investment. The state could consider variations of this requirement—for example, requiring that at least 10 percent of an institution’s revenue be derived from nongovernment sources.

Recommend Other Changes to Process

Recommend Changing Certification Date From October 1 to November 1. To facilitate CSAC’s data collection, we recommend moving the certification date to November 1 instead of October 1. This better reflects the U.S. Department of Education’s schedule for posting graduation rates to IPEDS. Additionally, we recommend the Legislature clarify that CSAC should use the most recent publicly available data, published by the department in any form, for its annual certification.

Avoid Changes During an Award Cycle Already Underway. Moving forward, we recommend the Legislature not implement eligibility changes during the Cal Grant award cycle that is underway at the time of budget enactment. Such implementation can leave students at newly ineligible schools without sufficient time to make alternative plans for the imminent academic year. For example, the eligibility changes approved in 2011 and 2012 took effect after most students already had applied for school, been admitted, received their financial aid offers, and made decisions regarding attendance. Although some students were able to enroll in community colleges, they faced limited course availability. Admissions to University of California and CSU already were closed by the effective dates. In addition to the problems it poses for students, the short implementation timeline places a burden on campuses, whose financial aid offices must repackage aid for their Cal Grant recipients (for example, to offset reduced or eliminated Cal Grant awards).

Even Longer Implementation Lag May Be Warranted in Some Cases. Though a one–year implementation lag likely is reasonable in many cases, we recommend a longer phase–in for some changes. For example, a new standard that requires consultation with institutions regarding specific metrics to be used may require a longer implementation lag. Likewise, for changes that could affect large numbers of students, both students and schools should have sufficient notice—and time to improve their outcomes—before the changes become effective.

Conclusion

New standards for Cal Grant participation have saved money in the short term and focused state financial aid resources on schools with better student outcomes (as measured by graduation rates and student loan default rates). At the same time, by eliminating most for–profit schools from eligibility the new rules have reduced Cal Grant recipients’ college choices and—at least in the short term—their access to postsecondary education. Although they have generally worked as intended, the new standards have some drawbacks that could be addressed by adjusting for differences in student characteristics and, for the graduation rate requirement, making it specific to Cal Grant recipients and applying the standard to all institutions. We recommend the Legislature maintain the new standards (with these adjustments) and continue monitoring their effects. We also suggest alternative measures to explore as new information becomes available. We recommend providing sufficient phase–in time for students and institutions to adapt to eligibility changes. Finally, we recommend moving the annual certification date from October 1 to November 1 and avoiding changes during award cycles that already are underway. With these recommended modifications, we believe the eligibility standards will better target Cal Grant investments to institutions that are effectively serving students and the state.

Appendix

Cal Grant Institutional Eligibility Provisions as Amended by Chapter 7, Statutes of 2011 and Chapter 38, Statutes of 2012

Education Code Title 3, Division 5, Part 42, Chapter 1.7

69432.7 (l) (1) “Qualifying institution” means an institution that complies with paragraphs (2) and (3) and is any of the following:

(A) A California private or independent postsecondary educational institution that participates in the Pell Grant Program and in at least two of the following federal campus–based student aid programs:

(i) Federal Work–Study.

(ii) Perkins Loan Program.

(iii) Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant Program.

(B) A nonprofit institution headquartered and operating in California that certifies to the commission that 10 percent of the institution’s operating budget, as demonstrated in an audited financial statement, is expended for purposes of institutionally funded student financial aid in the form of grants, that demonstrates to the commission that it has the administrative capacity to administer the funds, that is accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, and that meets any other state–required criteria adopted by regulation by the commission in consultation with the Department of Finance. A regionally accredited institution that was deemed qualified by the commission to participate in the Cal Grant Program for the 2000–01 academic year shall retain its eligibility as long as it maintains its existing accreditation status.

(C) A California public postsecondary educational institution.

(2) (A) The institution shall provide information on where to access California license examination passage rates for the most recent available year from graduates of its undergraduate programs leading to employment for which passage of a California licensing examination is required, if that data is electronically available through the Internet Web site of a California licensing or regulatory agency. For purposes of this paragraph, “provide” may exclusively include placement of an Internet Web site address labeled as an access point for the data on the passage rates of recent program graduates on the Internet Web site where enrollment information is also located, on an Internet Web site that provides centralized admissions information for postsecondary educational systems with multiple campuses, or on applications for enrollment or other program information distributed to prospective students.

(B) The institution shall be responsible for certifying to the commission compliance with the requirements of subparagraph (A).

(3) (A) The commission shall certify by October 1 of each year the institution’s latest three–year cohort default rate and graduation rate as most recently reported by the United States Department of Education.

(B) For purposes of the 2011–12 academic year, an otherwise qualifying institution with a three–year cohort default rate reported by the United States Department of Education that is equal to or greater than 24.6 percent shall be ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution, except as provided in subparagraph (F).

(C) For purposes of the 2012–13 academic year, and every academic year thereafter, an otherwise qualifying institution with a three–year cohort default rate that is equal to or greater than 15.5 percent, as certified by the commission on October 1, 2011, and every year thereafter, shall be ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution, except as provided in subparagraph (F).

(D) (i) An otherwise qualifying institution that becomes ineligible under this paragraph for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards shall regain its eligibility for the academic year for which it satisfies the requirements established in subparagraph (B), (C), or (G), as applicable.

(ii) If the United States Department of Education corrects or revises an institution’s three–year cohort default rate or graduation rate that originally failed to satisfy the requirements established in subparagraph (B), (C), or (G), as applicable, and the correction or revision results in the institution’s three–year cohort default rate or graduation rate satisfying those requirements, that institution shall immediately regain its eligibility for the academic year to which the corrected or revised three–year cohort default rate or graduation rate would have been applied.

(E) An otherwise qualifying institution for which no three–year cohort default rate or graduation rate has been reported by the United States Department of Education shall be provisionally eligible to participate in the Cal Grant Program until a three–year cohort default rate or graduation rate has been reported for the institution by the United States Department of Education.

(F) (i) An institution that is ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution under subparagraph (B), (C), or (G) shall be eligible for renewal Cal Grant awards for recipients who were enrolled in the ineligible institution during the academic year before the academic year for which the institution is ineligible and who choose to renew their Cal Grant awards to attend the ineligible institution. Cal Grant awards subject to this subparagraph shall be reduced as follows:

(I) The maximum Cal Grant A and B awards specified in the annual Budget Act shall be reduced by 20 percent.

(II) The reductions specified in this subparagraph shall not impact access costs as specified in subdivision (b) of Section 69435.

(ii) This subparagraph shall become inoperative on July 1, 2013.

(G) For purposes of the 2012–13 academic year, and every academic year thereafter, an otherwise qualifying institution with a graduation rate of 30 percent or less for students taking 150 percent or less of the expected time to complete degree requirements, as reported by the United States Department of Education and as certified by the commission pursuant to subparagraph (A), shall be ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution, except as provided for in subparagraphs (F) and (I).

(H) Notwithstanding any other law, the requirements of this paragraph shall not apply to institutions with 40 percent or less of undergraduate students borrowing federal student loans, using information reported to the United States Department of Education for the academic year two years before the year in which the commission is certifying the three–year cohort default rate or graduation rate pursuant to subparagraph (A).

(I) Notwithstanding subparagraph (G), an otherwise qualifying institution with a three–year cohort default rate that is less than 10 percent and a graduation rate above 20 percent for students taking 150 percent or less of the expected time to complete degree requirements, as certified by the commission pursuant to subparagraph (A), shall remain eligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution through the 2016–17 academic year.

(J) The commission shall do all of the following:

(i) Notify initial Cal Grant recipients seeking to attend, or attending, an institution that is ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards under subparagraph (C) or (G) that the institution is ineligible for initial Cal Grant awards for the academic year for which the student received an initial Cal Grant award.

(ii) Notify renewal Cal Grant recipients attending an institution that is ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution under subparagraph (C) or (G) that the student’s Cal Grant award will be reduced by 20 percent, or eliminated, as appropriate, if the student attends the ineligible institution in an academic year in which the institution is ineligible.

(iii) Provide initial and renewal Cal Grant recipients seeking to attend, or attending, an institution that is ineligible for initial and renewal Cal Grant awards at the institution under subparagraph (C) or (G) with a complete list of all California postsecondary educational institutions at which the student would be eligible to receive an unreduced Cal Grant award.

(K) By January 1, 2013, the Legislative Analyst shall submit to the Legislature a report on the implementation of this paragraph. The report shall be prepared in consultation with the commission, and shall include policy recommendations for appropriate measures of default risk and other direct or indirect measures of effectiveness in quality or educational institutions participating in the Cal Grant Program, and appropriate scores for those measures. It is the intent of the Legislature that appropriate policy and fiscal committees review the requirements of this paragraph and consider changes thereto.

(m) “Satisfactory academic progress” means those criteria required by applicable federal standards published in Title 34 of the Code of Federal Regulations. The commission may adopt regulations defining “satisfactory academic progress” in a manner that is consistent with those federal standards.

69433.2. (a) As a condition for its voluntary participation in the Cal Grant Program, each Cal Grant participating institution shall, beginning in 2012, annually report to the commission, and as further specified in the institutional participation agreement, both of the following for its undergraduate programs:

(1) Enrollment, persistence, and graduation data for all students, including aggregate information on Cal Grant recipients.

(2) The job placement rate and salary and wage information for each program that is either designed or advertised to lead to a particular type of job or advertised or promoted with a claim regarding job placement.

(b) Commencing the year after the commission begins to receive reports pursuant to subdivision (a), the commission shall provide both of the following on its Internet Web site:

(1) The information submitted by a Cal Grant participating institution pursuant to subdivision (a), which shall be made available in a searchable database.

(2) Other information and links that are useful to students and parents who are in the process of selecting a college or university. This information may include, but not be limited to, local occupational profiles available through the Employment Development Department’s Labor Market Information Data Library.