Several state departments administer health care programs and some departments administer more than one program. For example, DHCS administers the state–federal Medicaid Program—known as Medi–Cal in California—as well as the California Children’s Services Program and other programs. Similarly, DPH administers the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) and other programs aimed at protecting California’s population from infectious diseases. The health programs administered by state departments provide a variety of benefits to California’s citizens, including purchasing health care services for qualified low–income persons and performing various public health functions.

Most major state health programs are administered by one of the following three departments: (1) DHCS, (2) DPH, and (3) DSH. (Funding for state employees to administer health programs at the state level and/or provide services is known as “state operations.”) The actual delivery of many of the health care services provided through state programs takes place at the local level and is carried out by local government entities, such as counties, and private entities such as commercial health plans. (Funding for these types of services delivered at the local level is known as “local assistance.”) Most health services are provided through the local service delivery model.

Overview of Health Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes $18.8 billion from the General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $714 million—or 3.9 percent—above the revised estimated 2013–14 spending level, as shown in Figure 1. The net increase reflects increases in caseload and changes in utilization of services as well as the impact of major ongoing initiatives.

Figure 1

Major Health Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13Actual

|

2013–14 Estimated

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Medi–Cal—Local Assistance

|

$14,862

|

$16,230

|

$16,900

|

$670

|

4.1%

|

|

Department of State Hospitals

|

1,277

|

1,505

|

1,515

|

10

|

0.7

|

|

Healthy Families Program (HFP)—Local Assistancea

|

176

|

22

|

—

|

–22

|

—

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

129

|

115

|

111

|

–4

|

–3.5

|

|

Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP)b

|

34

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Other Department of Health Care Services programs

|

110

|

87

|

141

|

54

|

62.1

|

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

|

All other health programs (including state support)

|

149

|

165

|

171

|

6

|

3.6

|

|

Totals

|

$16,744

|

$18,131

|

$18,845

|

$714

|

3.9%

|

Summary of Major Budget Proposals and Changes. The budget plan reflects the fiscal effects of a major Medi–Cal provider payment proposal and two proposals to make state–level organizational changes. Regarding the latter, the administration proposes to transfer $200 million in all funds ($5 million General Fund) and 291 positions for the administration of DWP from DPH to SWRCB. The administration also proposes to transfer three health insurance programs from MRMIB to DHCS and eliminate MRMIB effective July 1, 2014. This would continue the shift of health insurance programs from MRMIB to DHCS that began with the transfer of the Healthy Families Program (HFP) in January 2013. As shown in Figure 1, General Fund spending for HFP decreases from a revised estimate of $22 million in 2013–14 to no expenditures in 2014–15 to reflect the completed transfer of children in HFP to Medi–Cal in November of 2013.

In 2011, budget–related legislation authorized reductions in certain Medi–Cal payments by up to 10 percent. Until recently, federal court injunctions prevented the state from implementing many of these reductions. In June 2013, the injunctions were lifted, giving the state authority to: (1) apply the reductions to current and future payments to providers on an ongoing basis and (2) retroactively recoup the reductions from past payments that were made to providers during the period in which the injunctions were in effect. The Governor’s budget proposes to exempt certain (but not all) classes of providers and services from the retroactive recoupments, and includes $36 million in increased General Fund expenditures in 2014–15 associated with this exemption proposal. Because the recoupments were otherwise scheduled to take place over several years, the total General fund cost of the proposal over this multiyear period is estimated to be $218 million. (We note that the budget assumes that the provider payment reductions—unless exempted legislatively or administratively—will continue prospectively, resulting in ongoing General Fund savings of $245 million in 2014–15.)

Summary of Major Ongoing Initiatives. The budget plan reflects the fiscal effects of major health policy initiatives that are under implementation. First, the budget assumes a couple of major fiscal effects associated with various provisions of the ACA that were enacted as part of the 2013–14 budget. For example, the budget assumes about $400 million in net General Fund costs in 2014–15 largely associated with the implementation of simplified Medi–Cal eligibility and enrollment processes that are expected to increase enrollment among individuals who are eligible for the program—often referred to as the mandatory Medi–Cal expansion. In addition, the budget assumes General Fund savings of $300 million in 2013–14 and $900 million in 2014–15 from implementation of the optional Medi–Cal expansion. These savings are realized through changes to the 1991 health realignment that were authorized as part of the 2013–14 budget and result in lower state General Fund costs in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) budget.

The budget plan also assumes a General Fund cost of $173 million from beginning implementation of the Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI) in 2014–15. (The CCI is scheduled to begin no sooner than April 2014 in eight counties.) Once fully implemented, CCI is estimated to save hundreds of millions of General Fund dollars annually. The CCI is intended to better serve seniors and persons with disabilities through improved integration of long–term care, behavioral health, and medical services. Specifically, the CCI includes two main components: (1) a three–year demonstration project, known as Cal MediConnect, for individuals—often referred to as “dual eligibles”—who are eligible for both Medi–Cal and Medicare and (2) integration of long–term services and supports (LTSS) into managed care and a requirement for nearly all Medi–Cal beneficiaries to be enrolled in managed care to receive these benefits. Implementation of CCI involves several departments, including DHCS, the Department of Social Services, and the Department of Aging.

Caseload trends are one important factor influencing state health care expenditures. Below, we highlight the caseload trends assumed in the Governor’s budget for Medi–Cal—by far the largest state–administered health program.

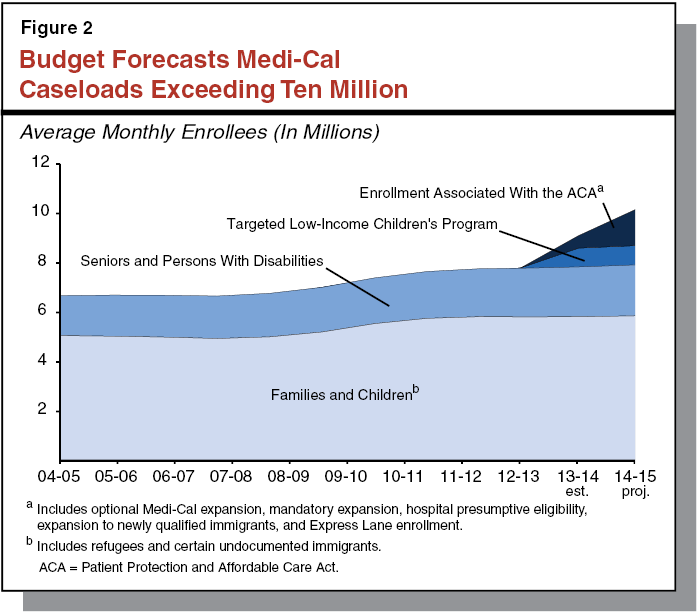

Medi–Cal Caseload. The Governor’s budget plan projects an average monthly Medi–Cal caseload of 9.2 million in 2013–14 and 10.3 million in 2014–15—an 11.6 percent year–over–year increase. This increase is mainly the result of implementing various ACA–related provisions. Figure 2 illustrates past Medi–Cal caseloads and the Governor’s projected caseload trends for Medi–Cal in 2013–14 and 2014–15, divided into four groups: (1) seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs), (2) families and children, (3) the Targeted Low–Income Children’s Program, or TLICP (including children formerly in HFP), and (4) individuals who will enroll as a result of various ACA–related changes. The SPDs and families with children categories include estimated underlying caseload trends for these populations, absent the effects of recent major policy changes. These two underlying caseload categories are projected to grow by about 1 percent between 2013–14 and 2014–15. The TLICP enrollment is projected to grow by 2.7 percent between 2013–14 and 2014–15. The remaining year–over–year caseload increase is largely the result of ACA implementation, including expanded eligibility for certain adult populations that began January 1, 2014, and various changes to the eligibility determination process that are expected to increase the proportion of eligible individuals who enroll. We discuss the Governor’s Medi–Cal caseload estimates, including estimated caseload increases associated with the ACA, in more detail below.

In California, the federal–state Medicaid Program is administered by DHCS as the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi–Cal). Medi–Cal is by far the largest state–administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. As a joint federal–state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for most low–income persons. Until recently, Medi–Cal eligibility was mainly restricted to low–income families with children, SPDs, and pregnant women. California generally receives a 50 percent Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) (federal share of costs) for these populations—meaning the federal government pays one–half of Medi–Cal costs for these populations. As part of the ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, the state expanded Medi–Cal eligibility to include additional low–income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program. The federal government will pay 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to this newly eligible Medi–Cal population from 2014 through 2016; the federal matching rate will phase–down to 90 percent by 2020 and thereafter.

There are two main Medi–Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: FFS and managed care. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi–Cal FFS generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the managed care plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Medi–Cal managed care plans provide enrollees with most Medi–Cal covered health care services—including hospital, physician, and pharmacy services—and are responsible for ensuring enrollees are able to access covered health services in a timely manner.

The Governor’s budget proposes $16.9 billion General Fund in 2014–15 for local assistance under the Medi–Cal Program, including the provision of health care services and administrative costs. This is a $670 million net increase, or 4.1 percent, over estimated 2013–14 expenditures. Generally, the level of expenditures and changes in year–over–year spending are driven by various factors, including:

- The total enrollment of beneficiaries in the program and per–person cost of providing health care services, which is affected by both the price and level of utilization for individual services.

- Technical changes that result from the timing of receipt or payment of funds.

- Implementation of various state and federal policy changes enacted in recent years.

Major Policies Affecting Year–Over–Year Spending Changes. The Governor’s 2014–15 budget reflects recent implementation and planned implementation of major programmatic changes enacted in recent years, including:

- ACA Implementation. The budget includes a variety of significant fiscal effects related to ACA implementation. Changes related to the ACA result in both costs and savings to the Medi–Cal Program that are hundreds of millions of dollars annually in some instances. We discuss the major ACA–related changes in the “ACA Implementation” section below.

- CCI. The budget assumes a General Fund cost of $173 million from beginning implementation of CCI no sooner than April 1, 2014. This is because the state will incur upfront costs from making both managed care payments and retroactive FFS payments as beneficiaries and services transition to Medi–Cal managed care. (Once fully implemented, CCI is estimated to save hundreds of millions of General Fund dollars annually.) The administration recently announced that one of the demonstration plans, CalOptima in Orange County, was subject to a federal audit of its existing Medicare Special Needs product for dual eligibles. As a result of this audit, the Cal MediConnect portion of CCI will not proceed in Orange County—which represents about 14 percent of the estimated 456,000 beneficiaries eligible for enrollment in Cal MediConnect—until CalOptima takes corrective actions to address the deficiencies uncovered by the audit. At the time of this analysis, the administration had not released updated fiscal estimates to reflect anticipated changes in CCI enrollment resulting from CalOptima’s temporary removal from the demonstration.

- Payment Reductions. The budget assumes that the state will continue to implement reductions to payments, enacted in 2011, to certain providers and managed care plans for certain services. (Some providers have been legislatively or administratively exempted from the payment reductions.) The budget assumes net General Fund savings of $100 million in 2013–14 and $246 million in 2014–15. (These estimates reflect reduced savings due to a temporary exemption from the payment reduction for primary care services in 2013 and 2014, as required by the ACA.) We discuss the implementation of these payment reductions in the “Medi–Cal Payment Reductions and Access to Care” section later in this analysis.

- Tax on Medi–Cal Managed Care Plans. The budget assumes General Fund offsets of $256 million in 2013–14 and $462 million in 2014–15 from a tax on Medi–Cal managed care organizations (MCOs), known as the MCO tax, that was authorized as part of the 2013–14 budget. These estimates exclude additional MCO tax General Fund offsets associated with a significant increase in Medi–Cal managed care enrollment under the ACA—$51 million in 2013–14 and $233 million in 2014–15—which are accounted for as General Fund offsets in the “ACA Implementation” section later in this analysis.

- Hospital Fee. The budget assumes General Fund offsets of $155 million in 2013–14 and $713 million in 2014–15 from the recently enacted hospital quality assurance fee. These estimates reflect a delay in implementation as the state seeks federal approval of the new fee program. The administration has indicated that it expects to receive this approval no sooner than June 2014.

Managed Care Enrollment Continues to Increase. Managed care is increasingly becoming the dominate delivery system in the Medi–Cal program as both the number and the percentage of Medi–Cal beneficiaries enrolled in managed care continues to grow. Roughly 65 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care in 2012–13. The Governor’s budget projects that, on average, 70 percent of beneficiaries will be enrolled in managed care in 2013–14 and 73 percent—about 7.5 million Medi–Cal beneficiaries—will be enrolled in managed care in 2014–15. The increase in managed care enrollment reflects transitions of beneficiaries from FFS to managed care, as well as additional enrollees associated with the transfer of HFP and implementation of the ACA.

Baseline Caseload Estimates Reasonable. The administration projects baseline caseload—or program caseload absent changes associated with recent major policy changes, such as the shift of HFP and implementation of the ACA—will be about 7.7 million average monthly enrollees in 2013–14 and 7.8 million in 2014–15—a 1 percent year–over–year increase. We have reviewed the administrations baseline caseload projections and we do not recommend any adjustments at this time. If we receive additional information that causes us to change our assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis at the time of the May Revision.

ACA Estimates Are Generally Reasonable. As shown in Figure 3, the budget assumes that various ACA provisions will result in nearly 1.5 million additional average monthly enrollees in 2014–15. The caseload increase includes additional enrollment associated with the optional expansion, mandatory expansion, hospital presumptive eligibility, and Express Lane enrollment. (Please see our “ACA Implementation” section below for a more detailed description of these changes.) We have reviewed the administration’s caseload estimates and, accounting for the significant amount of uncertainty about how the ACA will affect Medi–Cal caseload, we find the estimates to be reasonable. If we receive additional information that causes us to change our assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis at the time of the May Revision.

Figure 3

Major ACA Caseload Estimates

Average Monthly Enrollees (In Thousands)

|

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Optional expansiona

|

330

|

779

|

|

Mandatory expansionb

|

130

|

509

|

|

Express Lane enrollmentc

|

17

|

151

|

|

Hospital presumptive eligibilityd

|

25

|

32

|

|

Totals

|

502

|

1,471

|

High TLICP Caseload Projection Raises Questions. The HFP provided health coverage to children in households with incomes too high to qualify for Medi–Cal, but below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). The transition of children from HFP to Medi–Cal generally did not change the eligibility criteria. Children transferring from HFP were enrolled in the newly created Medi–Cal TLICP, which provides coverage to children in families with incomes too high to qualify for Medi–Cal, but below 250 percent FPL. (Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs converted to the new Modified Adjusted Gross Income method for counting income for most beneficiaries and the new converted standard for the TLICP is 261 percent FPL.) When the transition began in January 2013, approximately 850,000 children were enrolled in HFP.

The Governor’s budget estimates that about 995,000 beneficiaries will be enrolled in the TLICP in 2014–15—representing a nearly 17 percent increase in caseload over roughly a two–year period. This is a large increase in caseload, compared to the relatively stable HFP caseload in the years before the transition began. According to the administration, there has been a significant increase in TLICP enrollment that appears to be driven by a large number of children shifting from existing Medi–Cal categories to the new TLICP categories—possibly caused by increasing incomes as the economy improves.

In our view, it is unlikely that the economic recovery alone would explain such a significant increase in TLICP caseload. This is because rising incomes associated with the economic recovery could serve to both increase and decrease the TLICP caseload. For example, individuals who were previously eligible for Medi–Cal who experience an increase in income may become eligible for the TLICP, thereby increasing caseload. On the other hand, individuals who were previously eligible for the TLICP whose families’ experience an increase in income may have incomes that are too high to qualify for the program, thereby decreasing caseload. While the degree to which these two factors offset each other is uncertain, it is unlikely that changing economic conditions alone would cause such a significant and rapid net increase in caseload.

Recommend Legislature Direct DHCS to Report on TLICP Caseload. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report at budget hearings on all the factors contributing to the significant increase in TLICP caseload. With more comprehensive information on the basis for the administration’s projections, the Legislature can assess whether the amount budgeted for the TLICP caseload is the appropriate amount and whether the higher caseload reflects any unintended changes in children’s health coverage associated with the HFP transition to Medi–Cal.

The budget assumes a wide variety of fiscal effects—some major and some minor—associated with implementing various provisions of state and federal law related to the ACA. Many of the ACA provisions that affect the Medi–Cal Program went into effect in 2013 or early 2014 and the effects of many of these changes are still highly uncertain. In this section, we: (1) summarize the major ACA state fiscal effects that are estimated in the Medi–Cal budget and provide our assessment of them, (2) identify some potential fiscal effects that are omitted from the budget, (3) provide our assessment of the Governor’s proposal to modify coverage offered to pregnant women in Medi–Cal, (4) raise issues that the Legislature may want to consider in light of recent ACA changes, and (5) provide recommendations that are generally intended to enhance legislative oversight of ACA implementation.

Figure 4 summarizes the major ACA–related fiscal effects (over $10 million General Fund in a year) that are included in the 2014–15 Medi–Cal local assistance budget. Figure 4 also includes estimated General Fund savings (in the CalWORKs budget) from the changes to 1991 health realignment that were enacted as part of the 2013–14 budget. These changes reflect the decreased county indigent care responsibilities as a result of the expansion of Medi–Cal under the ACA. Some of the major ACA fiscal effects are the result of complying with federal requirements, such as the costs associated with the so–called mandatory Medi–Cal expansion. Other major ACA fiscal effects are the result of choices made by the Legislature, such as the decision to adopt the optional Medi–Cal expansion. We note that Figure 4 excludes some other major ACA fiscal effects assumed in the 2014–15 budget, such as additional General Fund offsets gained through increased hospital fee revenue (no estimates of this amount were available at the time of this analysis) and additional federal funding that is used to offset state General Fund spending in other state departments.

Figure 4

Selected Major Fiscal Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on Medi–Cala

(In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

|

2014–15

|

|

Federal Funds

|

General Fund

|

Federal Funds

|

General Fund

|

|

Additional Enrollment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optional expansion

|

$2,618

|

–$43

|

|

$6,622

|

–$198

|

|

Changes to 1991 health realignmentb

|

—

|

–300

|

|

—

|

–900

|

|

Mandatory expansion

|

119

|

104

|

|

448

|

419

|

|

Express Lane enrollment

|

70

|

1

|

|

676

|

12

|

|

Hospital presumptive eligibility

|

13

|

10

|

|

43

|

39

|

|

County Administration

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional county administration funding

|

72

|

72

|

|

65

|

65

|

|

Enhanced federal match for certain eligibility determination functions

|

124

|

–124

|

|

248

|

–248

|

|

Changes to Benefits

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enhanced mental health services

|

45

|

28

|

|

181

|

119

|

|

Enhanced substance use disorder services

|

51

|

33

|

|

127

|

79

|

|

Shift certain pregnant women to Covered California

|

—

|

—

|

|

–17

|

–17

|

|

Other Changes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Temporary rate increase for primary care services

|

1,628

|

34

|

|

575

|

27

|

|

Health insurer fee

|

—

|

—

|

|

67

|

55

|

|

Collect managed care drug rebates

|

–194

|

–194

|

|

–146

|

–179

|

|

One percent increase in federal match for preventative services

|

40

|

–40

|

|

27

|

–27

|

The state budget will continue to be affected by ACA implementation in the future. The estimates included in the budget plan generally do not reflect future state costs and savings associated with ACA implementation that will occur after 2014–15. For example, the enhanced federal cost share for the newly eligible Medi–Cal optional expansion population will begin to phase down in 2017, resulting in increased state costs. However, the federal cost–share for the Medi–Cal population that was formerly enrolled in HFP—now referred to as TLICP—will temporarily increase in October 2015, resulting in state savings.

In the next section of this analysis, we describe eligibility expansions, changes to county administration of eligibility determinations, changes to Medi–Cal benefits, and other major ACA–related changes that affect the Medi–Cal budget.

Additional enrollment in Medi–Cal resulting from ACA implementation will result in both state costs and savings. Much of the additional enrollment is a result of expanded Medi–Cal eligibility. Other ACA changes—such as penalties for not obtaining coverage (also known as the individual mandate), increased outreach activities, and new enrollment pathways—will increase enrollment above the levels that would otherwise have occurred in the absence of these changes. We first describe the major fiscal effects related to increased Medi–Cal enrollment under the ACA that are included in the Governor’s budget.

Optional Expansion. Effective January 1, 2014, Medi–Cal eligibility expanded to include previously ineligible adults with incomes up to 138 percent FPL—largely childless adults. The administration estimates that nearly 700,000 newly eligible beneficiaries will enroll in 2013–14, growing to over 800,000 newly eligible beneficiaries in 2014–15. (Newly eligible persons who enroll through new enrollment pathways such as Express Lane enrollment or hospital presumptive eligibility are estimated separately and discussed in more detail below.) The federal government is paying for 100 percent of the health care costs for the newly eligible population through 2016. Fiscal estimates of the optional expansion incorporate savings achieved from higher General Fund offsets from the MCO tax and costs for providing services to certain newly qualified immigrants who are eligible for state–only Medi–Cal coverage under state law. Savings from changes to 1991 health realignment and stemming from the optional Medi–Cal expansion are estimated separately.

Historically, counties have had the fiscal and programmatic responsibility for providing health care for low–income populations without public or private health coverage—also known as indigent health care. As part of 1991 realignment, the state provided a dedicated funding stream to counties for indigent health care and public health activities—hereafter referred to as health realignment funds. The optional Medi–Cal expansion shifts much of the responsibility for indigent health care to the state and federal governments, and counties are likely to experience significant savings. In recognition of the shifting responsibilities for indigent health care, the 2013–14 budget established a complex structure under which a portion of county health realignment funds will be redirected to help pay CalWORKs grant costs previously borne by the state—thereby offsetting state General Fund costs. The methods used to determine the redirected amount differ among counties and some counties will have the option to choose between two general approaches: (1) the so–called “60/40” option, whereby a predetermined percentage of health realignment funds will be redirected from the county each year, or (2) the so–called “formula” option whereby 80 percent of the estimated savings counties realize under the ACA is redirected to the state. The amount that can be redirected in 2013–14 is capped at $300 million. For more detail on the different methods for determining the redirected amount, see our November report, The 2013–14 Budget: California Spending Plan. The administration projects $300 million will be redirected in 2013–14 and $900 million will be redirected in 2014–15.

Mandatory Expansion. Several federal ACA requirements will result in additional Medi–Cal enrollment and state costs. For example, the ACA includes requirements that will likely encourage individuals who were eligible for Medi–Cal prior to January 1, 2014, but not enrolled, to enroll in the program (hereafter referred to as previously eligible populations). These requirements include streamlining and simplifying the eligibility determination process and a penalty for certain individuals who do not obtain health coverage (also known as the individual mandate). The ACA also requires Medi–Cal to expand eligibility to include former foster youth up to age 26. Collectively, the administration refers to these changes as as the “mandatory expansion.” Generally, the state will continue to be responsible for 50 percent of the costs of providing services to these new enrollees. A small portion of the state costs will be offset by savings from higher MCO tax General Fund offsets that result from the additional enrollment. The administration assumes net mandatory expansion costs of $104 million General Fund in 2013–14 and $419 million General Fund in 2014–15.

Hospital Presumptive Eligibility. Prior to ACA implementation, some Medi–Cal providers have been able to grant temporary presumptive eligibility to a limited group of individuals, including pregnant women and children. Beginning January 1, 2014, under the ACA, hospitals now have the option to make presumptive eligibility determinations for most Medi–Cal applicants on the basis of preliminary information provided by individuals, generally when they seek care at the hospital. Individuals who are determined presumptively eligible may receive full–scope Medi–Cal for up to two months, at which point the individual will need to complete a full Medi–Cal eligibility application in order to continue to qualify for coverage. Implementation of hospital presumptive eligibility will result in an estimated partial–year General Fund cost of $10 million in 2013–14 and a full–year General Fund cost of $39 million in 2014–15.

Express Lane Enrollment. States have the option to implement “Express Lane” enrollment, whereby a streamlined process is used to enroll certain persons who—based on information already available to states—are likely to be eligible for Medicaid, but not yet enrolled. California is scheduled to implement an Express Lane enrollment option in February 2014 for persons who are enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as CalFresh in California. The state is targeting its Express Lane enrollment process toward adults who are likely newly eligible for Medi–Cal and, thus, most of the costs associated with providing coverage to the new enrollees would be eligible for a 100 percent federal match. In the future, the state also plans to implement an Express Lane process for parents with children in Medi–Cal and enrollees in other state health programs, such as the Genetically Handicapped Persons Program (GHPP), Every Women Counts, and the Prostate Cancer Treatment Program. The administration estimates that over 300,000 individuals will enroll through the new Express Lane enrollment process in 2014, roughly 50 percent of whom would not have otherwise enrolled in the program through one of the other enrollment pathways. Implementation of Express Lane enrollment will result an estimated partial–year General Fund cost of $1 million in 2013–14 and a full–year General Fund cost of $12 million in 2014–15.

The ACA will increase the number of Medi–Cal applicants and require counties to make changes to how they carry out eligibility determinations for Medi–Cal applicants. In addition, under new federal rules related to the ACA, a significant portion of state General Fund costs for Medi–Cal eligibility determinations may be offset by an enhanced federal match for specified functions.

County Administration Funding for Eligibility Determinations. The ACA contains several provisions that will affect county administration costs for conducting Medi–Cal eligibility determinations. Certain provisions of the ACA—such as those that significantly increase the number of Medi–Cal applications and enrollees—will increase costs for counties conducting Medi–Cal eligibility determinations. On the other hand, ACA provisions that simplify the eligibility determination process will likely reduce the average cost of conducting eligibility determinations and redeterminations. The Governor’s budget provides $65 million of additional General Fund support for counties in 2014–15 to fund costs related to ACA implementation—slightly less than the $72 million of additional General Fund provided in the 2013–14 budget because it removes one–time costs for training county eligibility workers and county/state–level planning and implementation. (These costs do not reflect the ongoing $15 million General Fund cost–of–living adjustment that was provided for county eligibility determination activities in 2013–14.)

Enhanced Federal Funding for Certain Eligibility Determination Functions. Generally, payments to counties for making Medi–Cal eligibility determinations for both the previously and newly eligible populations are eligible for a 50 percent federal match. However, federal guidance released in 2011 allows states to receive a 75 percent federal match for certain eligibility determination functions, including costs for processing applications, case maintenance, and renewals. (Activities classified as policy, outreach, or post–eligibility are not eligible for the 75 percent match.) In order to qualify for the enhanced federal funding, states must meet certain minimum eligibility system requirements outlined by the federal government, including coordinating with the health insurance Exchange operating in the state, which in California is called Covered California. (The federal guidance is not solely related to ACA implementation, but the regulations are, in part, related to changes in Medicaid eligibility determination systems and processes under the ACA.) The DHCS must secure federal approval prior to receiving the enhanced federal match. The budget assumes the state currently meets federal requirements and will be eligible to receive the enhanced federal funding for roughly 70 percent of county eligibility determination costs incurred after January 1, 2014.

Enhanced Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services. As part of ACA implementation, California is providing all Medi–Cal–covered nonspecialty mental health services through managed care, including some new mental health services that are included in the benefits package that is covered by plans offered through Covered California. These services will be available for both the previously and newly eligible Medi–Cal populations. The state will also provide an enhanced set of substance use disorder services for previously and newly eligible populations. The budget assumes General Fund costs of $198 million in 2014–15 to provide these additional services.

Shift Certain Pregnant Women to Covered California. The Governor’s 2014–15 budget proposes to shift pregnant women between 109 percent and 208 percent FPL who qualify for Medi–Cal pregnancy–only coverage to plans offered through Covered California. The administration also proposes to provide full–scope coverage—rather than pregnancy–only coverage—to all pregnant women below 109 percent FPL who receive coverage from Medi–Cal. The budget assumes General Fund savings of $17 million in 2014–15 related to this proposal. We discuss the Governor’s pregnancy–only proposal and our assessment of it in more detail below.

Similar proposals were discussed last year in budget subcommittee and policy committees. For example, the administration proposed a similar shift of pregnant women to Covered California and the associated savings were adopted as part of the 2013–14 budget under the assumption that the details of the proposal would be worked out through policy committees. However, the statutory language authorizing such a shift was never enacted.

Temporary Primary Care Physician Rate Increase. The ACA requires states to increase Medicaid primary care physician service rates to 100 percent of Medicare rates for services provided from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2014. The rate increase applies to services provided in both FFS and managed care. The federal government will pay for 100 percent of the incremental increase above the Medi–Cal rates that were in effect as of July 1, 2009. Since the state enacted a 9 percent payment reduction for Medi–Cal primary care services in 2011, it must temporarily pay for the state share of the incremental difference between existing Medi–Cal rates and the rates that were in effect on July 1, 2009. The budget includes foregone General Fund savings associated with not implementing the scheduled payment reduction for primary care services in 2013 and 2014, as well as additional administrative costs associated with implementing the rate increase in managed care. The budget assumes the higher rates for primary care services sunset at the end of 2014 and the 9 percent reduction to primary care services that was postponed for 2013 and 2014 will go into effect at the start of 2015.

Health Insurer Fee. The ACA established a nationwide fee on the health insurance industry beginning January 2014. The nationwide fee will initially generate $8 billion annually and grow to $14.3 billion annually by 2018. The fee is allocated to qualifying health insurers based on their relative market share and exempts certain insurers such as nonprofit insurers that receive a substantial share of their premium revenue from public programs, such as Medicaid and Medicare. The budget includes costs associated with higher state payments to Medi–Cal managed care plans that are subject to the fee.

Managed Care Drug Rebates. The ACA extended the federal drug rebate requirement to outpatient drugs covered by all Medi–Cal managed care plans. Previously, drug rebates were collected for drugs provided through FFS and certain managed care plans. The fiscal estimates provided in Figure 4 include $33 million savings from a new proposal in the Governor’s budget that would allow the state to collect additional MCO supplemental drug rebates. Many of the details associated with this proposal are still unclear so we are unable to comment on the merits of the proposal at this time.

FMAP Increase for Preventative Services. Effective January 1, 2013, the ACA established a 1 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate for preventative services and adult vaccines in states that meet certain requirements. In order to qualify for the increase, a state must cover all preventative services assigned a Grade A or B by the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) and all approved vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and cannot impose beneficiary cost–sharing on such services. California opted to provide the preventative services necessary to qualify for the enhanced match and to not impose beneficiary cost–sharing for these preventative services. The budget includes $26.4 million General Fund costs from adding screening and counseling services for alcohol and substance use—services that were recently assigned a Grade A or B by the USPSTF—to the existing benefits package effective January 1, 2014. With this addition, the state will provide all services assigned Grade A or B; although we note that, at the time of this analysis, it is unclear whether these preventative services would have been added in the absence of the enhanced FMAP for preventative services. The budget assumes General Fund savings of $27 million in 2014–15 associated with the 1 percent increase in the federal match for preventative services.

We have reviewed the major ACA–related fiscal estimates included in the Governor’s budget, including the major underlying assumptions upon which these estimates are based. There is a significant amount of uncertainty surrounding many of the estimates, generally due to limited available data and actual experience as many ACA changes were only recently implemented. Based on currently available information, we find the administration’s ACA–related fiscal estimates to be reasonable. However, more reliable data and actual experience from the initial months of ACA implementation should become available in the next several months to better inform future ACA–related fiscal estimates. We highlight two major areas of uncertainty below: health realignment savings and mandatory expansion costs.

Health Realignment Savings. In recent weeks, information has been released that helps inform estimates of the amount of health realignment savings that will be achieved in 2013–14 and 2014–15. For example, counties have made decisions about which method they are using to determine realignment savings: the shared savings formula or the 60/40 option. These decisions are shown in Figure 5. In addition, based on information submitted by counties, DHCS determined the historical percentage of health realignment funds that has been spent on indigent health care which, among other things, will be used to establish a cap on the amount of realignment funds that can be redirected from counties that select the shared savings formula. (Counties have until February 28, 2014 to formally dispute these percentages.)

Figure 5

County Health Realignment Decisions

|

County

|

Decisiona

|

|

Counties With County Hospitals

|

|

|

Alameda

|

Formula

|

|

Contra Costa

|

Formula

|

|

Kern

|

Formula

|

|

Los Angeles

|

Formulab

|

|

Monterey

|

Formula

|

|

Riverside

|

Formula

|

|

San Bernardino

|

Formula

|

|

San Francisco

|

Formula

|

|

San Joaquin

|

Formula

|

|

San Mateo

|

Formula

|

|

Santa Clara

|

Formula

|

|

Ventura

|

Formula

|

|

Counties Without County Hospitals

|

|

|

Fresno

|

Formula

|

|

Merced

|

Formula

|

|

Orange

|

Formula

|

|

Placer

|

60/40

|

|

Sacramento

|

60/40

|

|

San Diego

|

Formula

|

|

San Luis Obispo

|

Formula

|

|

Santa Barbara

|

60/40

|

|

Santa Cruz

|

Formula

|

|

Stanislaus

|

60/40

|

|

Tulare

|

Formula

|

|

Yolo

|

60/40

|

While the newly available information helps inform estimates of the amount of health realignment funds that will be redirected to offset General Fund costs in CalWORKs, the state and counties are still in the process of collecting and analyzing data that will be used to project savings in counties that selected the shared savings formula. It is in these counties where the projected savings are subject to the most uncertainty because savings will depend on a variety of ACA impacts that remain highly uncertain. For example, the amount of realignment funds that will be redirected from counties that elect the shared savings formula and operate county hospitals will depend on uncertain factors such as how the ACA affects the number of patients who will receive care from county hospitals and whether these patients have Medi–Cal or other sources of health coverage.

Our office’s November Fiscal Outlook assumed $930 million in General Fund savings from health realignment. Based on our initial review of the additional information that has become available since that projection, our revised savings estimates are similar to what we projected in November. Given the uncertainty discussed above, we consider $900 million—the January budget’s assumed savings—a reasonable “placeholder” number until more detailed and reliable data becomes available. When the administration provides revised projections of health realignment savings, we will provide the Legislature with an updated assessment.

Mandatory Expansion Costs. Mandatory expansion costs largely depend on behavioral responses that are very difficult to predict, such as responses to the individual mandate, and the degree to which the new simplified eligibility processes serve to facilitate enrollment and thereby increase caseload. In addition, the degree to which changes in caseload among the previously eligible population are attributable to factors related to the mandatory expansion versus some other recent policy changes, such as Express Lane enrollment, is highly uncertain. For example, some previously eligible individuals who enroll in Medi–Cal in response to the individual mandate, may have otherwise enrolled through the new Express Lane enrollment process. The degree to which caseload changes associated with the various ACA policy changes overlap is highly uncertain.

Last year, we conducted a detailed analysis of the administration’s mandatory expansion cost estimates. At the time of that analysis, the administration estimated mandatory expansion costs would be roughly $650 million General Fund in 2014–15. Our analysis concluded that the administration’s mandatory expansion cost estimates, while plausible, were significantly higher than what we considered most likely (about $300 million General Fund in 2014–15).

The Governor’s 2014–15 budget now estimates just over $400 million in General Fund costs in 2014–15 for the mandatory expansion. This estimate is similar to our office’s most recent estimate of slightly more than $350 million General Fund. We believe the administration’s mandatory expansion cost estimate is reasonable. Somewhat more reliable mandatory expansion cost estimates may be available in a few months, after more data are collected and analyzed and the effects of ACA implementation are better understood. When the administration provides updated mandatory expansion estimates in May, we will provide the Legislature with an updated assessment.

Budget Does Not Include an Estimate of Savings Related to Claiming Enhanced Federal Funds, as Required by State Law. Under some of the new ACA eligibility rules and the optional expansion, the state may be able to claim a 100 percent federal match for some enrollees who would have previously qualified for a 50 percent match. Chapter 23, Statutes of 2013 (AB 82, Committee on Budget), requires DHCS to report to the Legislature, each January and May, the projected General Fund savings attributable to claiming enhanced federal funding for previously eligible Medi–Cal beneficiaries. The law also required DHCS to confer with applicable fiscal and policy staff of the Legislature by no later than October 1, 2013 regarding the potential content and attributes of the information provided in its savings estimate.

The administration has not complied with either of these requirements. The DHCS did not confer with all of the relevant fiscal staff of the Legislature by October 1, 2013. Furthermore, the Governor’s January budget does not include the required fiscal estimate. According to the administration, the details of the federal claiming process are still being discussed with the federal government and the administration did not provide an estimate because it has no basis on which to estimate savings.

In our view, preliminary fiscal estimates of factors that will likely have significant effects on the amount of General Fund spending in the Medi–Cal Program should be included in the budget—even if these estimates are highly uncertain and subject to change in the coming months. The Medi–Cal budget frequently contains preliminary estimates and assumptions that are based on limited data and experience. For example, many of the other ACA–related fiscal estimates discussed above are subject to substantial uncertainty and are based on assumptions that are based on limited actual experience, yet these estimates are included in the budget. Such estimates serve as placeholders until more refined estimates can be completed and allow for more informed budget deliberations because the Legislature has an opportunity to assess the administration’s estimates and assumptions and discuss the budget with a more complete understanding of the factors affecting expected General Fund spending.

Recommend Legislature Direct Administration to Report on Estimates of Enhanced Federal Funding for Previously Eligible Beneficiaries. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report at budget hearings on the reasons it failed to confer with all of the relevant legislative staff and provide a fiscal estimate of enhanced federal funding available for previously eligible beneficiaries, as required by state law. In addition, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to describe: (1) the previously eligible populations that may now be eligible for the 100 percent federal match, (2) the total amount of General Fund that was spent on these populations in previous years, (3) the major sources of uncertainty that led to the decision to not include a fiscal estimate in the budget, and (4) the administration’s timelines for providing its fiscal estimate. With this additional information, the Legislature can begin to assess the potential magnitude of the fiscal effects and account for these effects as it discusses the 2014–15 budget.

Budget Does Not Assume Caseload Decreases for Some Smaller State Health Programs. Some state health programs, such as certain programs that are optional under federal Medicaid law—such as the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program (BCCTP)—or funded primarily with state funds (also known as state–only programs)—such as the GHPP—have traditionally provided coverage to individuals who may not qualify for full–scope Medi–Cal and who may not have private health insurance. Figure 6 lists the major optional and state–only health programs. Under the ACA, some of the individuals who would have otherwise enrolled in these programs will likely obtain coverage through the optional Medi–Cal expansion or Covered California—thereby likely decreasing caseload in these programs. In some programs, such as the ADAP, the budget adjusts for savings associated with reduced caseload under the ACA. In other programs, the budget does not adjust for likely caseload declines.

Figure 6

State Health Programs Affected or Potentially Affected by the ACAa

|

Program

|

Major Eligibility Criteriab

|

Description of Services

|

|

Prostate Cancer Treatment Program

|

- Age 18 or older.

- Income up to 200 percent FPL.

- No other health coverage.

|

Prostate cancer treatment, patient education, and case management/patient navigation.

|

|

Every Woman Counts

|

- Female.

- Income up to 200 percent FPL.

- Services not covered by health coverage or coverage has high deductible/copayment.

|

Comprehensive breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services, clinical follow–up, and tailored health eduction.

|

|

Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program

|

- In need of treatment for breast or cervical cancer.

- Income up to 200 percent FPL.

- No other health insurance.

- State–only program for individuals: (1) without satisfactory immigration status, (2) with high cost health insurance, and (3) females 65 years or older.

|

Full–scope coverage for individuals who meet federal eligibility criteria; cancer treatment and cancer–related services for individuals in state–only portion of the program.

|

|

Genetically Handicapped Persons Program

|

- Generally over age of 21.

- Diagnosis of an eligible genetic condition.

- No income limit.

- State–only program for Medi–Cal–ineligible persons.

|

Medically necessary services, including case management services, regardless of whether services are related to qualifying medical condition.

|

|

Major Risk Medical Insurance Program

|

- Persons unable to obtain private health insurance because of a pre–existing medical condition.

|

Health coverage, including preventative care, hospital care, physician visits, and drugs.

|

|

Access for Infants and Mothers Program

|

- Pregnant women.

- Income 200 percent to 300 percent FPL.

- No health coverage or coverage has maternity–only deductible or copay greater than $500.

|

Comprehensive benefits, including pregnancy and non–pregnancy related services.

|

|

AIDS Drug Assistance Program

|

- HIV–infected.

- Over age 18.

- Income up to $50,000.

- Lack health coverage that covers the medications.

|

HIV/AIDS medications.

|

|

Medi–Cal 200 Percent FPL Pregnant Women

|

- Pregnant women.

- Income at or below 208 percent FPL.

|

Pregnancy related and 60–day post partum services.e

|

|

Medi–Cal Medically Needy Share–of–Cost Families

|

- Pregnant women, parent/caretaker relatives, and children.

- No income limit, but income determines share–of–cost amount.

- Asset test.

|

Full–scope Medi–Cal once share–of–cost has been met.

|

|

Family Planning, Access, Care, and Treatment

|

- Income up to 200 percent FPL.

- No other source of health care coverage for family planning, or meet other specified criteria.

|

Family planning and reproductive health services.

|

|

California Children’s Services (CCS)c

|

- Under age 21.

- Diagnosed with CCS–eligible medical condition.

- State–only program for children ineligible for Medi–Cal with family income less than $40,000 per year or estimated annual cost of care that exceeds 20 percent of family income.

|

Pediatric specialty and subspecialty health care, case management, and care coordination; school–based therapy services available regardless of family income.

|

|

Qualified aliens inside the five–year bard

|

- Qualified aliens who otherwise meet Medi–Cal eligibility requirements, but who have been legally residing for less than five years and, thus, do not qualify for federal matching funds.

|

Full–scope Medi–Cal .

|

Many of the major ACA changes only recently went into effect and the magnitude of their effects on caseloads in these optional and state–only health programs are highly uncertain. Some of these programs serve populations that are ineligible for Medi–Cal or subsidized insurance offered through Covered California. However, there will likely be at least minor caseload reductions in many of these programs that are not accounted for in the budget plan. The Department of Finance (DOF) indicated in meetings with legislative staff that it intends to review the impact ACA has on caseload and utilization levels for these programs in the fall of 2014 as part of its 2015–16 budget development process. The DOF also indicated that more complete caseload and utilization data will be available in the latter half of 2014 that will better inform any proposals DOF puts forward to modify these existing state–only programs to account for the impact of ACA implementation. Under this approach, 2014–15 caseload and budgeted funds would be the basis for future discussions about whether to modify these programs.

Recommend Legislature Direct Administration to Report on Effects of ACA on Other State Health Programs. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report in budget hearings on the following: (1) the existing state health programs that are likely to experience caseload declines under ACA; (2) factors that would limit any potential decline in caseload and costs in these programs, such as a substantial portion of enrollees who continue to be ineligible for Medi–Cal or subsidized coverage through Covered California; and (3) the administration’s timeline for making adjustments to the budgets of these programs. With this information, the Legislature can better assess potential caseload decreases in these programs under the ACA and potentially adjust the budgets for these programs accordingly.

Pregnancy–Only Proposal Has Merit, but Some Details Remain Unclear

Currently, certain pregnant women up to 208 percent FPL qualify for pregnancy–only Medi–Cal coverage—which includes only services related to a woman’s pregnancy, rather than full–scope Medi–Cal coverage. The Governor’s pregnancy–only proposal has two main components: (1) shifting certain pregnant women between 109 percent and 208 percent FPL from Medi–Cal pregnancy–only coverage to coverage offered through Covered California and paying for “wrap–around” coverage and (2) providing full–scope coverage to pregnant women up to 109 percent FPL who currently receive pregnancy–only coverage. Pregnant women with incomes between 109 percent FPL and 208 percent FPL would have the option to enroll in federally subsidized coverage from plans through Covered California that provide broad benefits, and Medi–Cal would pay for their premiums, cost–sharing, and certain pregnancy–related supplemental services—also known as wrap around coverage. The proposal caps the amount of wrap–around premiums and cost–sharing that Medi–Cal would pay to the amount that would cover all beneficiary premiums and cost–sharing for the second lowest cost “silver” plan. Thus, women in this income band would have the option to choose any plan on the Exchange, but Medi–Cal would not cover all of the costs of more expensive plan options.

In our view, both components of the Governor’s proposal have merit, but some aspects of the proposal remain unclear. Below, we discuss the primary merits of the proposal and identify some key aspects of the proposal that remain unclear at the time of this analysis.

Shift Would Likely Reduce General Fund Spending, While Potentially Providing More Generous Benefits. The proposal to shift certain pregnant women from pregnancy–only Medi–Cal to Covered California would potentially enhance the scope of services available to these pregnant women. Pregnant women would have the option to receive comprehensive coverage from plans offered through Covered California, while maintaining certain wrap–around services that are available in Medi–Cal, such as dental services and access to certain perinatal specialists. In addition, since the women would qualify for federally subsidized coverage through Covered California, the proposal would generate state General Fund savings by leveraging federal subsidies to pay for a large portion of costs that were previously covered by Medi–Cal. For example, most of the costs for these pregnant women—such as costs for most perinatal visits and labor and delivery—would be covered by the plan obtained through Covered California, instead of the Medi–Cal Program. The state would only pay the relatively minor costs of the wrap–around coverage for these women. The administration estimates that the shift would reduce state General Fund spending by about $17 million in 2014–15.

Full–Scope Coverage Would Eliminate Coverage Inconsistencies for Pregnant Women. Under current law, some childless women applying for Medi–Cal would qualify through the optional expansion and receive full–scope Medi–Cal coverage. If a woman becomes pregnant while enrolled in Medi–Cal, she would be allowed to remain in the new adult group and continue to receive full–scope coverage. However, a woman with the same income who applies for Medi–Cal at the time she is pregnant would be eligible for pregnancy–only coverage. The Governor’s proposal to provide full–scope coverage to pregnant women below 109 percent FPL would make the scope of covered services for pregnant women in Medi–Cal consistent, regardless of whether the woman became pregnant before or after applying for Medi–Cal. The administration assumes no additional cost associated with providing full–scope—instead of pregnancy–only—coverage to pregnant women below 109 percent FPL.

Some Details of Proposal Remain Unclear. The Governor’s proposal has merit in concept because it would expand the scope of coverage available to certain pregnant women in Medi–Cal, make the scope of coverage more consistent for pregnant women who enter the program at different times, and at the same time reduce state General Fund costs. However, some details of the Governor’s proposal remain unclear at the time of this analysis, including:

- Differences in Covered Services and Costs Between Full–Scope and Pregnancy–Only Coverage. The specific differences in covered services between full–scope and pregnancy–only coverage are still unclear. The administration estimates no additional costs associated with providing full–scope coverage instead of pregnancy–only coverage—an estimate that is based on the assumption that there are no significant differences in coverage. However, it has not provided the basis for this assumption. While it is likely that the differences in covered services are relatively minor, full–scope coverage may result in the state paying for some additional services for pregnant women and, thereby, result in additional costs that have not been accounted for in the Governor’s budget.

- Continuity of Coverage and Plan Choice. The specific options that would be available to women to remain in the same plan and continue to receive care from the same physician under this proposal are uncertain.

Recommend the Legislature Direct the Administration to Clarify Details of Pregnancy–Only Proposal. While we believe the Governor’s pregnancy–only proposal has merit, there are some details that remain unclear. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to clarify the details of this proposal, including (1) the differences in covered services between full–scope Medi–Cal and pregnancy–only Medi–Cal, and (2) continuity of coverage and plan choice for individuals moving between Medi–Cal and Covered California. With more complete information, the Legislature can more accurately: (1) assess how this proposal will affect coverage for certain pregnant women on Medi–Cal, (2) evaluate whether the administration’s estimated fiscal effects are appropriate, and (3) identify potential modifications to the proposal.

The ACA has resulted in major changes to the Medi–Cal Program and many other aspects of health care in California. Now that many of the major changes are being implemented, the Legislature will still need to provide oversight of ACA implementation, as well as shift its attention to the future of Medi–Cal and other state health programs. Below, we discuss some of the issues that we believe should be priorities for future legislative consideration.

The Future of Other State Health Programs Under the ACA. As shown in Figure 6, the state currently administers several other health programs that are relatively small compared to the Medi–Cal Program. Many of these other programs provide health care to targeted groups of individuals, often with specific medical conditions. Some of the individuals who currently qualify for these other programs would be newly eligible for Medi–Cal or subsidized coverage through Covered California.

The Legislature may want to consider the future of some of these programs and how they fit into the broader system of coverage established under the ACA. Last year, the administration publicly indicated its interest in discussing potential changes to some of these programs. As a result, options to restrict individuals from enrolling in programs such as ADAP, GHPP, and BCCPT if they were also eligible for Medi–Cal or subsidized coverage through Covered California were discussed in a budget subcommittee last year. While these changes were never officially proposed by the administration or adopted by the Legislature, in our view, the Legislature should consider similar or alternative options to leverage new sources of coverage to reduce costs in some of these programs. For example, the Legislature may want to consider opportunities to shift individuals into subsidized Covered California plans while offering wrap–around coverage—similar to the Governor’s pregnancy–only proposal discussed above.

Any potential modifications to these programs should be thoroughly vetted, as many of the programs serve vulnerable populations with acute health care needs. Some key issues the Legislature may want to consider as it weighs the future of these programs include:

- Need for Services. The Legislature should seek to clarify which services and benefits being provided by these programs are also provided in Medi–Cal or through Covered California plans and which services are only available in these programs. The specialized services offered by these programs may not be available elsewhere, and enrollees who are not eligible for full–scope Medi–Cal or Covered California plans, such as undocumented immigrants, may not be able to obtain these services if the programs are eliminated.

- Federal Requirements. The Legislature should seek to clarify federal requirements and restrictions that limit the state’s options for modifying these programs. For example, several of these programs are subject to federal maintenance–of–effort requirements that limit the state’s ability to modify the programs.

Once these factors were well understood, the Legislature could identify options to modify some of these programs in ways that leverage federal funding to offset state costs and comply with federal requirements. This process would also help identify the key benefits and services provided by these programs that the Legislature would like to preserve or possibly enhance.

Opportunities to Leverage Federal Funds to Improve Program Outcomes. The state’s actuaries develop a range of potential capitation rates that could be paid to Medi–Cal managed care plans that reflect various assumptions about factors affecting future plan costs—also known as the “rate range.” Generally, the state pays Medi–Cal managed care plans at the lower bound of the rate range. However, through 2016, the state can leverage the 100 percent federal match to pay rates for newly eligible populations at the upper bound of the rate range. This gives the state flexibility to pay higher rates to managed care plans for certain beneficiaries at no additional cost to the state.

As part of the changes made to 1991 health realignment last year, the Legislature determined how it would like to use a portion of the rate range flexibility—higher payments to county hospitals. The Legislature required that plans in counties with county hospitals use 75 percent of the difference between the lower bound and the upper bound of the rate range for newly eligible populations to increase managed care payments to those hospitals. At the time of this analysis, it is still unclear whether the remaining 25 percent of the rate range will be paid to plans in public hospital counties and whether any of the rate range will be paid to plans in other counties. The administration is currently in discussions with plans about whether and how the remaining rate range will be used.

The Legislature should begin to identify key activities and outcomes that it would like to achieve in Medi–Cal managed care and explore opportunities to use the rate range flexibility to promote those activities and outcomes. For example, there may be opportunities to leverage the rate range to promote improvements in managed care quality, access, and/or data reporting that are priorities for the Legislature. The Legislature should also bear in mind that the 100 percent federal match is temporary. Therefore, any ongoing commitment to activities financed through the rate range flexibility would be partially financed with state funds in future years as the federal match for the newly eligible population phases down.

Measuring and Monitoring Access to Care in Medi–Cal Managed Care. Access to care and provider network adequacy in the Medi–Cal Program is an important issue for the Legislature to monitor and oversee. The significant increase in Medi–Cal enrollment under the ACA creates additional demand for health care services from providers treating Medi–Cal patients. Most of the additional services will be provided by managed care plans and their contracted provider networks. If these provider networks do not have sufficient capacity to meet the increased demand, then beneficiaries may have difficulty accessing necessary health care services in a timely manner. We believe the Legislature should focus a significant amount of its oversight and monitoring efforts on access to care in Medi–Cal managed care. We provide more information on issues related to monitoring access to care in the “Medi–Cal Payment Reductions and Access to Care” section that immediately follows.

We do not recommend any specific adjustments to ACA–related fiscal estimates included in the budget at this time. However, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report on certain fiscal effects associated with the ACA that are not accounted for in the budget. We also recommend the Legislature direct the administration to clarify certain details of the Medi–Cal pregnancy–only proposal. Finally, we identify a few fiscal and policy issues that we think should be priorities for the Legislature to consider as the state implements the ACA. These issues include the future of other state health programs, opportunities to leverage federal funds to improve program outcomes, and measuring and monitoring access to care in Medi–Cal managed care.

Medi–Cal Payment Reductions And Access to Care

Chapter 3, Statutes of 2011 (AB 97, Committee on Budget), authorizes DHCS to reduce Medi–Cal FFS payments to providers for certain services by up to 10 percent, and to reduce capitation payments to Medi–Cal managed care plans by a related amount. The Legislature adopted Chapter 3 as part of a package of expenditure–related solutions to address the state’s 2011–12 budget problem. However, the Legislature has expressed concern that these reductions may impede beneficiaries’ access to services, and—as the state’s fiscal condition improves—has shown interest in restoring Medi–Cal payments that were reduced under Chapter 3.

This analysis begins by summarizing the state’s current approach to implementing the Chapter 3 reductions, including the Governor’s 2014–15 budget proposal. We next evaluate this approach taking into account (1) the quality and relevance of access monitoring information that is presently available, and (2) the distinction between—and relative significance of—access in managed care versus FFS. Lastly, we lay out issues for the Legislature to consider when deliberating over whether to restore funding that was reduced with the payment reductions, as well as recommendations for how the Legislature should proceed on the broader subject of access to care in Medi–Cal.

Chapter 3 authorizes (1) reductions in certain Medi–Cal FFS provider payments by up to 10 percent and (2) a roughly proportionate decrease to managed care capitation payments known as “actuarially equivalent” reductions. These reductions originally applied to a wide range of providers and services, including (1) outpatient services provided by physician and clinics, (2) institutional providers such as distinct–part nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities for the developmentally disabled, (3) ancillary services such as laboratory tests and medical transportation, and (4) retailers of medical goods such as pharmacies and medical equipment suppliers. Chapter 3 allows DHCS discretion to adjust these reductions as necessary to comply with federal Medicaid requirements, including those related to beneficiary access that we discuss later. Until recently, federal court injunctions prevented the state from implementing many of these reductions. In June 2013, the injunctions were lifted, giving the state authority to (1) apply the reductions to current and future payments to providers on an ongoing basis and (2) retroactively recoup the reductions from past payments that were made to providers during the period in which the injunctions were in effect. Since the 2013–14 budget was enacted, several types of providers and services have been exempted from the ongoing payment reductions through either administrative decisions by the DHCS or recently enacted legislation.

The Governor’s budget proposes to exempt certain classes of providers and services from the retroactive recoupments, and includes $36 million in increased General Fund expenditures associated with this proposal. Specifically, the budget proposes that the following providers and services be exempted from the retroactive recoupments: (1) physicians and clinics, (2) certain high–cost drugs, (3) dental services, (4) intermediate care facilities for the developmentally disabled, and (5) medical transportation. Because the recoupments are otherwise scheduled to take place over several years, the total General Fund cost of the proposal over this multiyear period is estimated to be $218 million. The administration has stated that while federal approval is required to forgive the recoupments, no statutory changes are necessary.

The budget assumes that the state will continue to implement reductions to payments to providers and services that have not been legislatively or administratively exempted from ongoing reductions. The budget assumes that these ongoing reductions will result in General Fund savings of $245 million in 2014–15.

The state required federal approval to implement the FFS reductions specified in Chapter 3. As part of the conditions of this approval, DHCS agreed to analyze and regularly monitor access to care in the FFS system. The administration has indicated that its FFS access monitoring continues to inform its decisions to exempt specific providers from the reductions, including the decisions reflected in the Governor’s budget. Below we describe the federal requirements for analyzing and monitoring FFS access with respect to Chapter 3.

Federal “Equal Access” Provision Governs FFS Provider Payments. Generally, states are required to obtain federal approval for reducing provider payment rates in their FFS Medicaid programs. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reviews states’ proposed reductions to ensure they comply with federal Medicaid law—including the requirement that FFS payments be sufficient to enlist enough providers so that care and services are available to Medicaid beneficiaries to at least the same extent that they are available to the general population in a geographic area. This requirement, often referred to as the equal access provision, only applies to provider payments and services in the FFS system—it does not apply to managed care. (Later, we discuss separate requirements that govern access considerations in Medi–Cal managed care.)

Proposed Federal Regulations to Implement Equal Access Provision. Until 2011, the federal government provided little regulatory guidance on how states should comply with the Medicaid equal access provision. Shortly after passage of Chapter 3, CMS proposed new regulations that, if adopted, would require states to conduct reviews of beneficiary access to services in their FFS systems. Under the draft regulations, a state seeking to reduce FFS provider payment rates for a service is required to submit the following materials to CMS.

- A baseline analysis of FFS access to the affected service, conducted within 12 months prior to submitting the proposed reductions.

- A plan for continually monitoring FFS access to the service after implementing the proposed reductions.