California’s major human services programs provide a variety of benefits to its citizens. These include income maintenance for the aged, blind, or disabled; cash assistance and welfare–to–work services for low–income families with children; protecting children from abuse and neglect; providing home care workers who assist the aged and disabled in remaining in their own homes; collection of child support from noncustodial parents; and subsidized child care for low–income families.

Human services are administered at the state level by DSS, Department of Developmental Services (DDS), Department of Child Support Services, and other California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHSA) departments. The actual delivery of many services takes place at the local level and is carried out by 58 separate county welfare departments. The major exception is Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP), which is administered mainly by the U.S. Social Services Administration.

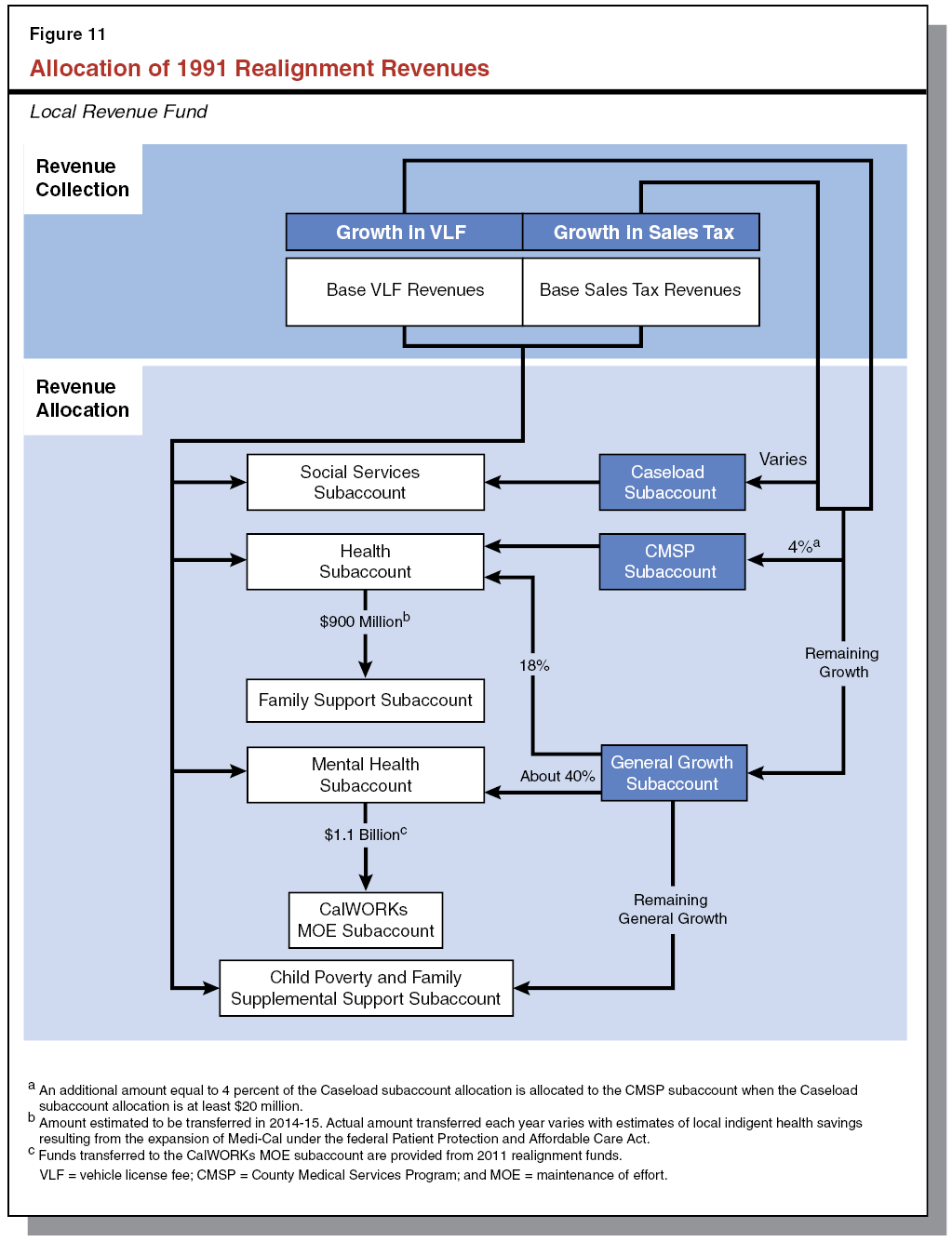

Recent Major Changes in Funding for Human Services Programs. As a result of realignment–related legislation in 2011 and 2013, the budget reflects shifts to counties of a significant amount of General Fund costs in human services programs. Specifically, as a result of 2011 legislation, the budget (beginning in 2011–12) reflects shifts to local realignment revenues of about $1.1 billion of General Fund costs in the CalWORKs program and about $1.6 billion in child welfare and adult protective services General Fund costs. As a result of the latter shift, the state’s role with respect to child welfare and adult protective services is largely one of oversight of county administration of these program areas.

Legislation enacted in 2013 shifted additional General Fund costs in the CalWORKs program to local realignment revenues that previously have been used to provide health services to indigent individuals. These realignment revenues have been freed up given that many indigent individuals are newly eligible for coverage in the state–funded Medi–Cal Program. Specifically, the budget shifts $300 million in CalWORKs General Fund costs to these local realignment revenues in 2013–14 and an additional $600 million (for a total of $900 million) in 2014–15. The 2013 legislation additionally provided that the costs of specified ongoing increases to CalWORKs assistance payments will be shifted to revenues from the growth of existing local realignment revenues that otherwise would have supported other social services programs. These recent changes to realignment are discussed in greater detail below in the “CalWORKs” section of this report.

Overview of Human Services Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of about $9.9 billion from the General Fund for human services programs in 2014–15. As shown in Figure 1, this reflects a decrease of $132 million—or 2.5 percent—from revised General Fund expenditures in 2013–14.

Figure 1

Major Human Services Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Actual

|

2013–14 Estimated

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14 to 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

SSI/SSP

|

$2,752.6

|

$2,782.3

|

$2,816.5

|

$34.2

|

1.2%

|

|

Department of Developmental Services

|

2,674.5

|

2,803.1

|

2,934.7

|

131.6

|

4.7

|

|

CalWORKs

|

1,544.5

|

1,206.2a

|

636.9b

|

–569.3

|

–47.2

|

|

In–Home Supportive Services

|

1,705.9

|

1,910.0

|

1,994.1

|

84.1

|

4.4

|

|

County Administration and Automation

|

617.0

|

763.2

|

798.7

|

35.5

|

4.6

|

|

Department of Child Support Services

|

298.9

|

313.0

|

312.9

|

–0.1

|

—

|

|

Department of Rehabilitation

|

55.3

|

57.0

|

57.0

|

—

|

0.1

|

|

Department of Aging

|

31.4

|

32.2

|

32.2

|

—

|

—

|

|

All other social services (including state support)

|

239.3

|

261.7

|

294.7

|

33.0

|

12.6

|

|

Totals

|

$9,919.3

|

$10,128.7

|

$9,877.7

|

–$251.0

|

–2.5%

|

Summary of Major Budget Proposals and Changes. As shown in Figure 1, the budget reflects generally stable or modest growth in General Fund expenditures across most human services programs, with CalWORKs being the major exception. The 47 percent decrease ($569 million) in CalWORKs General Fund expenditures can largely be explained by a year–over–year increase of $600 million in 1991 health realignment revenues that are being redirected to help pay for CalWORKs grant costs, thereby reducing General Fund expenditures by a like amount. The CalWORKs budget also reflects a 5 percent increase in cash grant levels costing $168 million, although this is funded almost entirely from realignment revenues (with $6 million General Fund). The CalWORKs budget also reflects a net increase of $91 million from the General Fund to implement a number of recent policy changes—that result in costs and savings—related to early engagement, family stabilization, and subsidized employment. Finally, the budget proposes a six–county, three–year Parent/Child Engagement Demonstration Pilot in CalWORKs, at a three–year cost totaling $115 million General Fund ($9.9 million in 2014–15). We discuss the grant increase, implementation of recent policy reforms, and the proposed pilot program in detail later.

The 4.4 percent growth ($84 million) in IHSS General Fund expenditures mainly reflects the partial–year cost ($99 million General Fund in 2014–15) of the Governor’s policy proposal to comply with new federal labor regulations. These regulations require, among other things, that IHSS providers be paid overtime for work over 40 hours a week. We provide an analysis of this proposal later.

The 4.6 percent increase ($36 million) in General Fund expenditures in the County Administration and Automation budget line item largely reflects a $30 million increase for CalFresh administration (due to the caseload impact of outreach conducted with the implementation of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [ACA]) and a $12 million increase for two human services automation projects.

Varied Growth Through Recession. While caseload grew for most of the state’s human services programs during the recent recession, there was substantial variability among them. (One key exception is the state’s foster care caseload, which has declined since 2001 and through the recession. In part, this reflects the creation of the Kinship Guardian Assistance Payment program in 2000 that facilitates a permanent placement option for relative foster children outside of the foster care system.) For example, over the 2007–08 to 2011–12 period, the CalFresh and CalWORKs caseloads increased by 97 percent and 27 percent, respectively, while the IHSS caseload—less susceptible to economic fluctuations—increased by 8 percent. The SSI/SSP caseload grew modestly during this time period (3.4 percent)—in part reflecting recent grant reductions that in effect reduced the eligible population—and is projected to grow relatively modestly in 2014–15.

We now turn more specifically to caseload trends in the IHSS and CalWORKs programs and the budget’s assumptions regarding caseload for these two programs in 2014–15.

IHSS Caseload Projected to Grow Modestly in 2014–15. The budget projects the average monthly caseload for IHSS to be 453,417 in 2014–15—a 1.3 percent increase over the most recent estimate of the 2013–14 caseload. We discuss the administration’s projection in further detail below in the “IHSS” section of this report. For historical perspective, the IHSS caseload has remained relatively flat throughout the five–year period from 2009–10 through 2013–14, in part reflecting policy changes that constrained caseload growth.

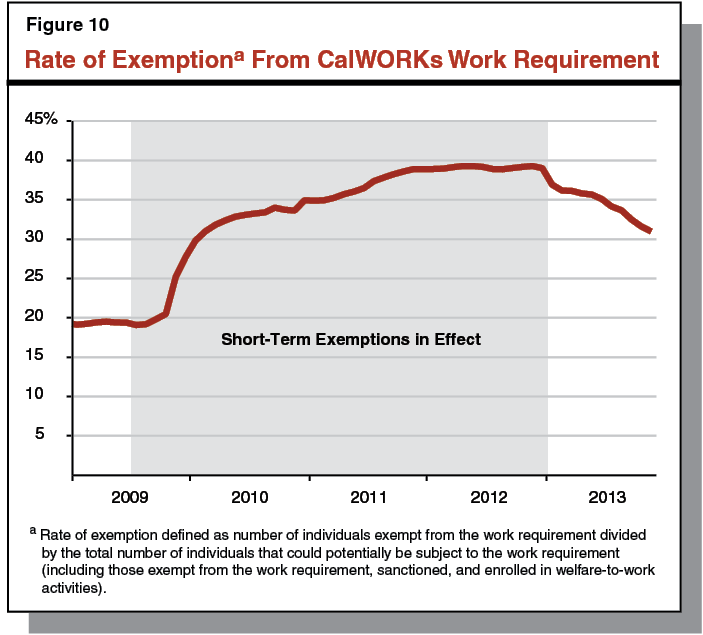

CalWORKs Caseload Continues to Decline. In the midst of the recent recession, the CalWORKs caseload rose substantially and peaked at over 597,000 cases in June 2011. The caseload has been declining since that time due to enacted policy changes and an improving labor market. The budget assumes a CalWORKs caseload of 545,647 cases in 2013–14, a 2.5 percent decline from the previous year. The year–over–year decline in caseload is assumed to accelerate somewhat to 3 percent in 2014–15, resulting in a caseload of 529,376.

The federal Department of Labor recently released new regulations that affect home care workers. A home care worker can be any individual who provides home care services, including certified nursing assistants, home health aides, or personal care aides such as providers for California’s IHSS program. Personal care refers to assistance with activities of daily living—such as bathing, grooming, and bowel and bladder care—provided to a consumer by a home care worker. The new federal labor regulations—effective January 1, 2015—make two significant changes, discussed below, that affect the home care industry. These new federal labor regulations have budgetary implications for both the state’s IHSS program and DDS. In this analysis, we describe the federal labor regulations, explain how these regulations impact IHSS and DDS, describe the Governor’s proposals to comply with the regulations, and provide modifications to the Governor’s IHSS proposal for consideration by the Legislature.

Federal Labor Regulations Require Home Care Workers to Be Paid for Certain Work Activities. The federal labor regulations require home care workers to be paid for certain work activities, effective January 1, 2015. Generally, employers have been exempt from the requirement to pay home care workers for the following work activities that will now require payment.

- Wait Time During Medical Appointments. Time spent waiting for consumers during medical appointments must be paid.

- Travel Time During the Work Day. Time spent traveling during the employee’s regular work hours, such as travel time to shop for food or perform other errands on behalf of the consumer, must be paid. For home care workers employed by a “third–party employer,” travel time between consumers during the workday must also be paid. (A third–party employer is an employer other than the consumer receiving services. In the case of the IHSS program, the state can be understood to be the third–party employer.)

- Mandatory Worker Training. Time spent attending training required by the employer must be paid.

Federal Labor Regulations Require Home Care Workers to Receive Overtime Pay for Working More Than 40 Hours Per Week. Employers of home care workers have been exempt from the requirement to pay overtime at the rate of one–and–a–half times the regular pay rate for all hours worked that exceed 40 in a week. However, effective January 1, 2015, federal labor regulations require home care workers to be paid overtime. Under federal law, the requirement to pay overtime may not be waived by agreement between the employer and employee. Further, an announcement or notice by the employer that no overtime work will be permitted will not infringe on the employee’s right to receive overtime pay for hours that exceed 40 in a workweek. In other words, the employer is required to pay overtime when it is claimed by an employee on his/her timesheet, regardless of whether the overtime is authorized or not.

Narrow Exemptions to Overtime Pay Requirement When Consumer, His/Her Family, or Household Is the Employer. When a worker is employed by a consumer receiving services or the consumer’s family or household, the federal labor regulations provide for narrow exemptions to the requirement to pay overtime. One of these exemptions—known as the “live–in domestic service worker exemption” is available when a worker is employed by—and resides with—the consumer receiving services or the consumer’s family or household. In these cases, the consumer, his/her family, or household may claim the live–in domestic service worker exemption to avoid paying the worker overtime for hours that exceed 40 in a workweek (and would instead pay at least the state–mandated hourly minimum wage for all hours worked). However, this exemption is not available to a third–party employer, such as the state in the existing program model of IHSS. (It may be possible for an IHSS recipient to claim this exemption under a different program model for the delivery of IHSS–like services, which we discuss later in this report.)

The federal labor regulations we describe have significant implications for the state’s IHSS program. Effective January 1, 2015, IHSS providers that deliver personal care and domestic services to IHSS recipients will be compensated for certain work activities, including wait time during medical appointments and travel time during the work day, which are currently not compensated by the IHSS program. Additionally, IHSS providers will be eligible to receive overtime pay for hours worked that exceed 40 in a workweek. Below, we provide background information about the IHSS program that is relevant to understanding the implications of the federal labor regulations.

The IHSS Program Is a Medi–Cal Benefit That Provides Personal Care and Domestic Services. The IHSS recipients are eligible to receive up to 283 hours per month of assistance with tasks such as bathing, dressing, housework, and meal preparation that are delivered by an IHSS provider in the recipient’s home. The recipient has the right to determine when service hours are provided within the month. For nearly all recipients, the IHSS program is delivered as a benefit of the state’s Medicaid health services program (known as Medi–Cal in California) for low–income populations. The IHSS program is therefore subject to federal Medicaid rules. For more background on IHSS, please refer to the “In–Home Supportive Services” section of this report.

Division of Employer Responsibilities in the IHSS Program. Employer responsibilities in the IHSS program are divided among three entities.

- Recipient. The recipient has the right to hire, supervise, and train the IHSS provider and can fire the provider for any reason. Essentially, the recipient has the right to receive care from a provider of his/her choosing—a concept we refer to as “consumer choice.”

- State. The IHSS providers submit their timesheets to a state processing facility and receive payment from the state for the hours they work during each pay period. The state is responsible for paying for certain benefits, including state disability insurance, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation insurance.

- Public Authority. The Public Authority at the county level currently negotiates with unions representing IHSS providers to set wages and benefits. The Public Authority also maintains a registry of providers who may be available to work for IHSS recipients who are unable to identify their own provider. (We note that recent legislation provides for the future transfer of collective bargaining responsibilities from the county level to the state level in certain counties.)

Because of this division of IHSS employment responsibilities, it is our understanding that the IHSS recipient, the state, and the Public Authority at the county level are all considered to be joint employers of IHSS providers for the purposes of the new federal labor regulations. The state and the Public Authority are third–party employers because they are entities other than the consumer receiving services. However, because of the financial structure of the IHSS program in which county costs are effectively capped given recently enacted maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirements, the state would assume all of the nonfederal costs associated with newly paying for overtime and for the work activities newly required to be compensated.

Individuals Must Follow Four Steps Before Being Enrolled as IHSS Providers. Currently, prospective IHSS providers must complete four steps in order to be enrolled as a provider and receive payment from the state, including completion of an application, a criminal background check, a brief IHSS program provider orientation, and completion of an enrollment agreement.

IHSS Providers Receive Wages Negotiated at the County Level. Because the wages of IHSS providers are negotiated at the county level, they vary by county—currently ranging from the state–mandated hourly minimum wage of $8 to $12.20 per hour. Providers currently receive the negotiated wage for all hours worked, regardless of whether they work in excess of 40 hours in a week. Chapter 351, Statutes of 2013 (AB 10, Alejo), increases the state–mandated hourly minimum wage from $8 to $9 effective July 1, 2014—and to $10 effective January 1, 2016. In 2014–15, the minimum wage increase to $9 will affect IHSS providers in 17 counties, where wages are currently less than $9 per hour.

IHSS Providers and Recipients Impacted by Federal Labor Regulations. The DSS, which administers the IHSS program, estimates that 385,425 individuals will work as IHSS providers in 2014–15. About 49,000 providers, or 12.7 percent of the estimated workforce, currently work more than 160 hours per month and will therefore be impacted by the requirement to pay overtime for hours that exceed 40 in a workweek. We note that some providers work for more than one recipient.

The DSS estimates that 453,417 low–income individuals who are aged, blind, or disabled will receive IHSS in 2014–15. About 37,000 recipients, or 8.2 percent of the estimated caseload in 2014–15, are expected to receive more than 160 service hours per month from a single IHSS provider. The IHSS recipients who receive more than 160 service hours per month are generally individuals who are reliant on the IHSS program for significant assistance with activities of daily living.

IHSS Providers Are Often Family Members or Relatives of Recipients. About 70 percent of IHSS recipients (an estimated 317,000 recipients) receive their care from a family member or relative provider. About half of IHSS recipients (an estimated 222,000 recipients) receive their care from a live–in provider, and 84 percent of these live–in providers are family members of the recipient. These family members could be, for example, a parent providing services to a minor child, a spouse providing services to a husband or wife, or an adult child providing services to a parent.

Absent any changes to the IHSS program, the administration estimates the annualized cost to comply with the federal labor regulations to be $620 million ($288 million General Fund). There are three main components of this cost estimate.

- Overtime Costs. Based on the existing workload of IHSS providers statewide, the DSS estimates that the cost of paying overtime would be $402 million ($186 million General Fund) annually. This estimate likely understates the actual cost of paying overtime as some IHSS providers would choose to work additional hours for other recipients in order to receive overtime pay for hours exceeding 40 in a workweek.

- Costs of Newly Compensable Work Activities. The DSS estimates that the cost of paying IHSS providers for wait time during medical appointments and travel time during the work day is $192 million ($89 million General Fund) annually.

- Administrative Activities. The DSS estimates that the cost of administrative activities to implement the new payments is $26 million ($13 million General Fund) annually. These costs would fund such administrative activities as county social worker time to answer questions from IHSS recipients and providers, making provider timesheet changes, and modifying the Case Management, Information, and Payrolling System (CMIPS) II information technology (IT) system used by the IHSS program—in order to handle authorization and payment for the newly compensable work activities and overtime.

The federal labor regulations we describe also have a budgetary impact on the state’s Community Services Program for eligible individuals with developmental disabilities that is administered by DDS. The budgetary impact for the Community Services Program is relatively minor when compared to the impact on the IHSS program. For more background on the Community Services Program, please refer to the “Developmental Services” section of this report.

Community Services Program Provides In–Home Assistance, Among Other Services and Supports. The Community Services Program provides eligible individuals with developmental disabilities with a broad range of services and supports they need to live in the community. The DDS oversees 21 nonprofit organizations known as regional centers (RCs), which purchase services and supports from vendors (generally organizations that hire employees to deliver services) for consumers. In some cases, consumers receive IHSS as a Medi–Cal benefit and receive other in–home services paid for by RCs, either on an ongoing basis or temporarily to provide respite to the primary caregiver.

Consumers and Workers Affected by Federal Labor Regulations. Due to current data limitations, the number of consumers who receive in–home assistance that exceeds 40 hours per week—and the number of workers who provide in–home assistance that exceeds 40 hours per week—is not known by DDS. These consumers who receive more than 40 hours of in–home assistance per week and home care workers who provide this assistance will be affected by the federal labor regulations.

The Governor’s budget responds to the federal labor regulations by (1) funding the cost associated with newly compensable work activities, (2) limiting the cost of overtime in the IHSS program by restricting IHSS providers to no more than 40 hours of work per week, and (3) providing a small rate increase to certain RC vendors in order for vendors to mitigate the fiscal impact of the requirement to pay overtime to their employees. At the time of this analysis, the administration had not yet released budget–related legislation providing further detail on its overtime proposals for IHSS and DDS. We provide details of the Governor’s proposals that were made available to us at the time of this analysis.

The administration estimates the annual ongoing cost of funding the three main components of its IHSS proposal—(1) paying for newly compensable work activities, (2) funding administrative activities to prevent overtime, and (3) maintaining a “Provider Backup System”—is $239 million ($113 million General Fund) annually. In Figure 2, we provide a cost summary of the Governor’s proposal to respond to the federal labor regulations in 2014–15 and 2015–16. (We note that Figure 2 includes the estimated costs of the Governor’s IHSS proposal as corrected by the administration for a technical budgeting error.) We discuss each component of the Governor’s IHSS proposal below.

Figure 2

Cost of Governor’s IHSS Proposal to Respond to Federal Labor Regulations

(In Millions)a

|

|

2014–15

|

|

2015–16

|

|

General Fund

|

Total Funds

|

General Fund

|

Total Funds

|

|

Newly compensable work activities

|

$40

|

$87

|

|

$88

|

$188

|

|

Administration to restrict overtime

|

27

|

53

|

|

10

|

19

|

|

Provider Backup System (including higher wage for backup providers and related costs)b

|

10

|

21

|

|

15

|

32

|

|

Totals

|

$77

|

$161

|

|

$113

|

$239

|

Pay for Newly Compensable Work Activities. The Governor’s budget proposes $87 million ($40 million General Fund) in 2014–15 to comply with the federal labor regulations that require the state to compensate IHSS providers for certain previously exempted work activities beginning January 1, 2015, or, for six months of 2014–15. The department estimates that the full–year cost is $188 million ($88 million General Fund) in 2015–16. The Governor’s budget funds compensation for wait time during medical appointments and travel time during the work day, but not the mandatory provider orientation, as explained below.

- Providers’ Wait Time During IHSS Recipients’ Medical Appointments. The current in–home IHSS assessment conducted by a county social worker assesses a consumer for the amount of time needed to travel to medical appointments, but makes no assessment for the amount of wait time that may be involved. The Governor’s budget assumes that the 85 percent of IHSS recipients who receive medical accompaniment will have their provider wait three hours per month—on average—during appointments. Based on these assumptions, the six–month cost of this work activity is estimated to be $81 million ($37 million General Fund) in 2014–15. However, because the exact amount of time that providers wait at medical appointments is unknown, the actual cost of paying IHSS providers for wait time during recipients’ medical appointments is uncertain.

- Providers’ Travel Time Between IHSS Recipients. The Governor’s budget estimates that 19 percent of IHSS providers serve multiple recipients. It is assumed that these providers who work for multiple recipients will spend one hour per month—on average—traveling between recipients. Based on these assumptions, the six–month cost of this work activity is estimated to be $6 million ($3 million General Fund). Like wait time during medical appointments, there is currently no data collected by the IHSS program on the exact amount of time IHSS providers spend traveling between IHSS recipients during the work day. Therefore, the cost of paying IHSS providers for travel time is uncertain.

- Mandatory Provider Orientation. While the federal labor regulations require IHSS providers to be paid for any mandatory training, the Governor’s budget does not request funding for the cost of paying individuals to attend the mandatory orientation prior to enrollment as an IHSS provider. The DSS has indicated to us that it assumes that the state may not need to pay individuals for participating in the mandatory orientation since it occurs before the individual enrolls as an IHSS provider. Based upon our review of the federal labor regulations, we find this assumption to be reasonable. However, because the mandatory orientation is brief (about one to two hours in most counties) and is only required to be completed once for individuals newly seeking to become IHSS providers, we do not estimate a significant General Fund cost if this activity is ultimately determined to require compensation.

Administrative Costs to Prohibit IHSS Providers From Working Overtime. The Governor’s budget proposes to respond to the federal labor regulations requiring overtime pay for home care workers by establishing an administrative structure that would prohibit IHSS providers from working overtime—at an estimated cost of $53 million ($27 million General Fund) in 2014–15. This restriction would generally require an IHSS recipient who receives more than 40 hours of care per week from a single provider to secure a second provider. To help IHSS providers set their schedules to avoid working overtime, the proposal requires all recipients and providers to complete “workweek agreements” to ensure no provider is scheduled to work more than 40 hours per week. These workweek agreements must be submitted to the county, reviewed by a county social worker, and entered by clerks into CMIPS II. The full–year cost of the administrative activities to restrict overtime is estimated to be $19 million ($10 million General Fund) in 2015–16. These administrative costs are estimated to decrease in 2015–16 primarily because the processing of workweek agreements by county social workers and clerks mostly occurs in the first year of implementation.

In addition to the workweek agreements, as a method to deter providers from working overtime, the proposal provides for suspending IHSS providers who claim more than 40 hours per week on their timesheet on at least two occasions. After the first instance of overtime claimed on a timesheet, the IHSS provider would receive a warning notice that he/she cannot claim more than 40 hours per week on his/her timesheet. After the second instance, the IHSS provider would be suspended from the program for a period of one year.

County social workers and clerks would conduct all administrative activities associated with the overtime restriction, including: (1) mass mailings about the overtime restriction and workweek agreement, (2) answering questions from IHSS providers and recipients about the overtime restriction, (3) reviewing the workweek agreements and entering the agreements into CMIPS II, (4) suspending and reenrolling certain IHSS providers, (5) adding IHSS providers to the Public Authority registry, and (6) coordinating services for the Provider Backup System, described below.

Provider Backup System for Unforeseen Circumstances. The Governor’s budget proposes $69 million ($32 million General Fund) in 2014–15 for the costs associated with establishing a Provider Backup System at the county level. (In Figure 2, we display the estimated costs of the Provider Backup System in 2014–15 and 2015–16 after correcting for a technical budgeting error, discussed below.) This system would supply a backup provider for an unforeseen circumstance in which an IHSS recipient is in need of immediate assistance but his/her regular provider has already worked 40 hours within the week, and other options, such as a second provider or the informal support of a family member or neighbor, are unavailable. In such circumstances, the consumer could call the system to request a backup provider who would be available in a short amount of time to provide assistance. Service hours delivered by a backup provider would be counted toward—and not in addition to—a recipient’s total allotment of monthly IHSS hours. The backup provider would receive a higher wage than the standard rate in the county to compensate him/her for the need to provide services on short notice.

The majority of the costs for the Provider Backup System funds a wage premium for backup providers above the county’s negotiated wage in order to compensate them for providing services on short notice. The estimate assumes that the cost of compensating the backup provider would be—on average—25 percent higher per hour than the estimated statewide average cost per hour of $12.33 in 2014–15. This translates into a wage premium of $3.08, and an average wage of $15.41 per hour for backup providers in 2014–15. (We note the exact amount of the wage premium for backup providers will be specified in forthcoming budget–related legislation.) The administration assumes that IHSS recipients with at least 60 monthly service hours will use the Provider Backup System. Accepting the administration’s assumptions regarding the utilization of the Provider Backup System and the incremental cost increase of about $3 per hour for provider backup services, we find the administration has overestimated the cost associated with paying for authorized service hours delivered by a backup provider by $22 million General Fund in 2014–15 (and by $48 million General Fund in 2015–16). This overestimation is due to a technical budgeting error, the administration acknowledges. In the nearby box, we provide an overview of two small–scale programs in San Francisco and Los Angeles Counties that have some similarities to the proposed Provider Backup System.

A number of Public Authorities at the county level have administered small–scale programs that have some similarities to the proposed Provider Backup System. The In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) hours provided by these programs are counted toward—and not in addition to—a recipient’s total allotment of monthly service hours. Below, we provide an overview of the programs in San Francisco and Los Angeles Counties that recipients may use when their regular provider is unavailable.

San Francisco’s Public Authority Operates On–Call Program. Consumers in San Francisco who need an IHSS provider on short notice can get assistance from the On–Call Program operated by the Public Authority. The On–Call Program is intended for several unforeseen circumstances: (1) when a consumer suddenly needs a provider but has not yet hired one, (2) when a recipient’s regular provider is not available, and (3) when the consumer is being discharged from a hospital or nursing home without a regular provider in place. The On–Call Program phone line is available Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. with messages retrieved until 8 p.m. On weekends and holidays, an assigned counselor checks the On–Call line for messages five times throughout the day. The On–Call Program averages about 130 requests per month from consumers seeking assistance. The On–Call counselors dispatch a provider from a select group of providers who are willing to make themselves available on short notice and who receive a higher wage of $16 per hour plus a $5 transportation allowance (compared to the standard wage of $11.75 per hour in San Francisco with no transportation allowance).

Los Angeles’ Public Authority Operates Backup Attendant Program (BUAP). The BUAP began as a pilot program in 2007 with the intent of providing high–need IHSS recipients in Los Angeles County with a backup provider available on short notice for urgent, temporary needs. Today, IHSS recipients who receive 25 hours or more of personal care each month are eligible to access BUAP when their provider and usual substitute provider are not available. The BUAP phone line is available Monday through Friday 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. When a consumer calls, the BUAP operators use a computer database to identify a backup provider who can best meet the consumer’s needs. All backup providers are required to undergo training or a proficiency exam in the provision of paramedical services, such as administering medications, wound care, or tube feeding. Backup providers also receive a higher wage of $12 per hour (compared to the standard wage of $9.65 per hour in Los Angeles County). We note that BUAP is not heavily utilized. In 2013, only 142 IHSS recipients were enrolled in BUAP. The BUAP phone line received 254 calls and provided 1,342 backup service hours for the full year in 2013.

Apart from paying for backup provider wages, the estimated cost for the Provider Backup System in 2014–15 includes $4 million General Fund to make relevant changes to CMIPS II and $250,000 General Fund for paying overtime to some IHSS providers who may claim more than 40 hours per week, despite the overtime restriction, on no more than two occasions.

The Governor’s budget proposes $7.5 million ($4 million General Fund) in 2014–15 to respond to the new federal labor regulations for DDS. These costs would double in 2015–16 to $15 million ($8 million General Fund). This amount funds a 2.25 percent increase in the rates paid to certain RC vendors that provide in–home assistance to individuals with developmental disabilities. The rate increase intends to provide vendors with sufficient funding to mitigate the fiscal impact of the requirement to pay their employees overtime for hours that exceed 40 in a workweek. Vendors may mitigate this fiscal impact by, for example, hiring more employees to deliver in–home services. However, as we noted earlier, the DDS does not have data available on the number of consumers who currently receive in–home assistance that exceeds 40 hours per week nor does it maintain data on the number of workers who provide in–home assistance that exceeds 40 hours per week. While we find it reasonable to assume that vendors will incur increased administrative costs to minimize overtime pay, we are uncertain because of data limitations whether a rate increase in the amount of 2.25 percent is appropriate.

Analyst’s Recommendation. Although we find it reasonable that vendors would incur administrative costs to limit overtime, it is difficult to determine the actual cost to vendors in the absence of data. In order to assess whether a 2.25 percent rate increase for certain vendors is appropriate on an ongoing basis, we recommend DDS report to the Legislature—no later than May 1, 2016—on the results of the rate increase on impacted vendors. The DDS could potentially gather and report relevant information, such as the average number of new employees that were hired by vendors based on organizational size, the average administrative cost of hiring a new employee, and other methods used by vendors to mitigate the fiscal impact of overtime pay for employees who would otherwise work more than 40 hours in a week.

We find the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime for IHSS providers to be worthy of consideration by the Legislature as a reasonable starting point for addressing the fiscal impact of the federal labor regulations on the IHSS program. The Governor’s proposal complies with the federal labor regulations in a manner that controls costs without reducing authorized service hours for IHSS recipients. Notwithstanding its merits, below we identify fiscal and policy issues that the Governor’s proposal raises. Later, we offer modifications to the Governor’s proposal that the Legislature may wish to consider to mitigate some of these policy concerns.

Below, we raise a number of policy issues with the Governor’s proposal to restrict IHSS providers from working more than 40 hours in a week. Some of these policy issues call into question whether the Governor’s proposal will work as intended to restrict overtime without causing recipients to forgo authorized service hours.

Some IHSS Recipients Will Experience an Erosion of Consumer Choice. As we note, the administration estimates that about 37,000 recipients who receive more than 160 service hours per month from a single provider will be impacted by the overtime restriction. About 49,000 providers currently work more than 160 hours per month and would experience a reduction in income because of the proposed overtime restriction. Under the Governor’s proposal, high–hour recipients would need to hire, supervise, and train an additional provider. Further, recipients who receive less than 160 service hours per month would need to ensure that their providers—who may work for multiple recipients—do not exceed 40 hours in any workweek. For some recipients who receive less than 160 service hours per month, this may involve switching to a provider who can fully accommodate their care without exceeding 40 hours in a workweek or hiring a second provider. The overtime restriction may prove to be an inconvenience for recipients who have an established plan of care with a single preferred provider. For consumers who receive care from a live–in provider, or from a family member or relative, the overtime restriction and potential need to hire a second provider may prove to be undesirable. Finally, for recipients with certain disabilities, such as a developmental disability, we understand anecdotally that some may experience challenges in adjusting to a new provider. The requirement that no single provider work more than 40 hours per week can be understood as an erosion of the existing consumer choice of some IHSS recipients who would no longer be able to receive all of their care from a single provider of their choice.

Uncertain Whether IHSS Providers Will Be Available to Fully Meet Predictable, Regular Care Needs. Because the Provider Backup System is only intended for unforeseen circumstances, an IHSS recipient who predictably and regularly needs more than 40 hours of assistance per week would need to retain at least two providers. It is uncertain if a sufficient number of IHSS providers would be available to meet this new demand for second providers—in some cases, for a small number of weekly hours. Depending on the labor market in a particular geographic area and a county’s negotiated wage—both of which change over time—along with a consumer’s needs and preferences, there may or may not be a sufficient pool of available providers.

We note that the following factors will likely assist consumers in identifying second providers: Public Authorities currently maintain registries of available IHSS providers (some providers on the registries may not be currently working at all), some existing IHSS providers who regularly work less than 40 hours per week may be willing to work additional hours for other recipients, and—in 17 counties where wages are currently set below $9 per hour—the increase in the state–mandated hourly minimum wage to $9 may encourage some individuals to work as IHSS providers. On the other hand, the Governor’s proposed one–year suspension of IHSS providers who claim overtime on two occasions, discussed further below, could somewhat reduce the pool of available providers.

Uncertain Whether the “Right” Backup Provider Will Be Available for Unforeseen Circumstances. For consumers who are in need of a backup provider to provide unforeseen assistance within a workweek, we find that a higher wage for backup providers is a reasonable way to work toward ensuring that a sufficient pool of backup providers is available from which to draw on short notice. However, even with a higher wage, it remains uncertain whether the Provider Backup System will be able to successfully pair all consumers with backup providers who meet consumers’ individualized needs in a manner that maintains their quality of care and preserves their preferences. The consumer may live in a geographically isolated area, may communicate in a language other than English, may have paramedical needs, or other specialized needs during the period in which the unforeseen assistance is required. The system would need to have a sufficient pool of backup providers as well as an effective matching process in order to adequately meet consumers’ individualized needs and preserve consumers’ right to hire a provider of their choosing.

Governor’s Proposal to Restrict Overtime Generally Lacks Flexibility. By restricting all overtime that exceeds 40 hours in a workweek, the Governor’s proposal inherently lacks flexibility. This lack of flexibility could have some significant policy consequences.

- Could Impede Consumers’ Access to Care. In the case of predictable, regular care for high–hour recipients, we are concerned about situations in which a county faces a shortage of available providers and is therefore unable to provide a consumer with a list of possible second providers. Under this scenario, the county would not have the flexibility to authorize overtime for a recipient’s regular provider until a second provider can be identified, and a consumer may be forced to forgo authorized care that exceeds 40 hours in a week in the interim.

- Could Result in Inefficient Response to Some Unforeseen Circumstances. Although the cost per hour of a backup provider is less expensive than the cost per hour of overtime for a regular provider, there may be other factors to consider—such as convenience and a consumer’s preference—when the care needed is unforeseen and requires a provider to exceed 40 hours in a week, but is expected to be limited in duration to just a couple hours. For instance, a recipient could fall and require assistance from the provider to get up, or a doctor’s appointment may last longer than expected. Under the Governor’s proposal, there is no flexibility for a provider to claim overtime for these types of short, unforeseen care needs if he/she has reached—or is approaching—the 40–hour workweek limit. However, such a situation may be an inefficient use of the Provider Backup System, which includes not only the higher wage of the backup provider but associated administrative costs to coordinate services in a short time frame.

- Enforcement of Overtime Restriction Could Lead to Some Unnecessary Disruptions in Care. The Governor’s proposed one–year suspension of IHSS providers who claim overtime on two occasions—without any exceptions—raises concerns in that it may suspend some IHSS providers and unduly cause a disruption in care for individuals receiving care from these providers. For example, if a provider does not receive the warning notice—because of a change of address or for some other justifiable reason—and as a result, claims overtime on two occasions, the provider would be suspended for a period of one year and the recipient would lose his/her regular provider. The provider may also submit two timesheets simultaneously or in close succession—both claiming overtime—before he/she receives the warning notice. Short of appealing the suspension, the provider would have no recourse but to wait for the period of one year to elapse. In cases in which the provider has made an honest mistake, the one–year suspension may be unwarranted and the recipient would likely experience a disruption in care that may cause him/her to rely on the Provider Backup System or to forgo care while a new regular provider can be identified.

After correcting the technical budgeting error, the administration estimates that the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime for all IHSS providers, including administrative activities to prevent overtime and maintenance of the Provider Backup System, would cost $51 million ($25 million General Fund) annually. This is significantly less than the estimated cost of paying for the overtime—$401 million ($186 million General Fund) annually. Both the cost of the Governor’s proposal and the estimated cost of paying the overtime are subject to some uncertainty. On the one hand, the cost of restricting overtime under the Governor’s proposal is somewhat uncertain because the ongoing administrative costs could be higher than assumed and the ongoing Provider Backup System costs could be higher if utilization exceeds the administration’s assumptions. On the other hand, the cost of paying for overtime would likely be higher than estimated by the administration since providers could change their behavior (such as by working additional hours for other recipients) in order to receive overtime pay.

Despite this uncertainty, the General Fund cost of restricting overtime as proposed by the Governor would still likely be significantly lower than the alternative—paying for overtime for all IHSS providers. We therefore find that on a purely fiscal basis, the Governor’s proposal makes sense. Even if the annual ongoing costs of restricting overtime were significantly higher, the state would still likely save more than $100 million General Fund annually by implementing the Governor’s overtime restriction instead of paying for overtime for IHSS providers. However, as we explained, there are programmatic implications associated with the Governor’s overtime restriction. Below, we suggest potential modifications to the proposal that the Legislature may wish to consider to mitigate, at least to some degree, these concerns.

Because of the policy issues we raise with the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime, the Legislature may want to consider potential modifications to the Governor’s proposal. In evaluating these modifications, the Legislature would want to weigh any additional costs of implementing the modification against the benefit of mitigating a particular policy concern using the following criteria.

- Costs Incurred for Overtime. What is the annual General Fund cost of overtime associated with the modification? Generally, mitigating an undesirable policy consequence of the overtime restriction—such as requiring a new provider for a high–hour recipient who currently relies on a single live–in provider—would result in additional costs compared to what the Governor is proposing (through the payment of overtime at least for some circumstances). However, the Legislature may wish to incur this cost if the modification mitigates, at least to some degree, an undesirable policy consequence of the Governor’s overtime restriction.

- Consumer Choice. Does the modification preserve or infringe on the existing choice of a recipient to hire a single provider of his/her choosing? Does the modification create added inconvenience for the consumer? The modification should mitigate—at least to some extent for certain populations—the undesirable policy consequence of reduced consumer choice and added inconvenience under the Governor’s overtime restriction.

- Administrative Cost and Complexity. Is the modification administratively costly and complex to implement? The modification should not be overly burdensome to implement at the state and county levels.

- Need for Additional Providers. Would the modification require the recruitment of new IHSS providers? The modification should not require a significant number of additional providers.

Within the framework of the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime, we find the Legislature has options to modify the proposal in a manner that addresses the policy concerns we raise. We assess each modification based on the criteria described above. We note that because IHSS is a Medi–Cal benefit, the implementation of some of these modifications would likely require approval from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to ensure compliance with federal requirements.

The Legislature could consider a targeted exemption from the overtime restriction for the providers of certain IHSS recipients—recipients who would find themselves in particularly disruptive situations if the overtime restriction applied to their providers. For example, a targeted exemption could include providers of (1) individuals with developmental disabilities who may face particular challenges in adjusting to a new provider, (2) individuals in rural counties who may face difficulties in finding a suitable second provider, or (3) individuals with live–in family or relative providers who strongly prefer to receive all of their care from the family member or relative. Because of federal Medicaid rules, we note there is significant uncertainty as to whether this modification would receive CMS approval. In Figure 3, we assess this modification to the Governor’s overtime restriction based on the criteria discussed above.

Figure 3

A Targeted Exemption From the Overtime Restriction for IHSS Providers of Certain Recipients

|

Criteria

|

Assessment of Modification Relative to Governor’s Proposal

|

|

Costs incurred for overtime

|

Additional costs, with amount dependent upon the overtime exposure of exempted providers delivering services to the targeted recipient population.

|

|

Consumer choice

|

Enhances consumer choice for the targeted recipient population.

|

|

Administrative cost and complexity

|

Results in some additional administrative activities—and thus added costs and complexity—associated with authorizing and tracking overtime for exempted providers of the targeted recipient population.

|

|

Need for additional providers

|

Reduces number of additional providers that would need to be recruited, since the targeted recipient population would not need additional providers.

|

The Legislature could consider modifying the Governor’s proposal by authorizing a limited allotment of overtime hours—for example, 48 hours in a year—to IHSS providers who work for high–hour recipients in order to give these providers some flexibility to work hours exceeding 40 in a week for special circumstances, such as a recipient’s fall or a long doctor’s appointment, without facing disciplinary action. This option could give providers who may already be in a consumer’s home the opportunity to address an unforeseen issue that is limited in duration to just a couple hours and could potentially reduce the number of calls placed to the Provider Backup System. We assess this modification to the Governor’s overtime restriction—using the example of 48 hours of flexible overtime in a year—in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Provide a Limited Allotment of Overtime, Such as 48 Hours Annually, to Certain IHSS Providers

|

Criteria

|

Assessment of Modification Relative to Governor’s Proposal

|

|

Costs incurred for overtime

|

- Additional costs, with amount dependent upon the amount of the flexible overtime allotment and utilization by providers.

- For our example, assuming 49,000 providers working for high–hour recipients claim the full 48 hours per year, the overtime cost would be roughly $5 million General Fund annually

|

|

Consumer choice

|

- Some added convenience and greater consumer choice for the special circumstances in which overtime is used.

|

|

Administrative cost and complexity

|

- Results in some additional administrative activities—and thus costs and complexity—associated with designating and tracking the flexible overtime allotment to ensure it is not exceeded.

|

|

Need for additional providers

|

- Need for additional providers largely unchanged.

|

We noted earlier that it is uncertain if a sufficient number of additional providers will be available in all counties to meet the new demand for providers under the Governor’s proposed overtime restriction. If a county is unable to provide a consumer with a list of alternative providers or a backup provider, the recipient could presumably be forced to forgo authorized care. If the Legislature wishes to ensure that all recipients maintain their current level of access to services, then it could consider authorizing overtime for an existing provider when a county is unable to give recipients a list of alternative providers or supply a backup provider. By authorizing overtime for the recipient’s existing provider in these situations, the state could ensure that the IHSS recipient receives authorized service hours until a second provider or backup provider can be identified. We assess the modification of authorizing overtime for a provider in the event that the county is unable to provide alternative options to the recipient in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Authorize Overtime When Other Providers Are Unavailable

|

Criteria

|

Assessment of Modification Relative to Governor’s Proposal

|

|

Costs incurred for overtime

|

- Additional costs dependent upon the frequency and amount of overtime authorized.

|

|

Consumer choice

|

- Enhances—to some degree—consumer choice by enabling a recipient to receive care from his/her existing provider in the event that a county is unable to provide alternative options.

|

|

Administrative cost and complexity

|

- Some additional administrative activities—and thus costs and complexity—associated with tracking instances of authorized overtime.

|

|

Need for additional providers

|

- Reduces need for additional providers in the short term.

- Need for additional providers largely unchanged in the longer run.

|

The Cash and Counseling Model Is an Alternative to IHSS. Some states have implemented what is commonly referred to as the Cash and Counseling (or “Self–Determination”) Model as an alternative to the IHSS model for the provision of personal care and domestic services. Under the Cash and Counseling Model, consumers receive a monthly sum of available funds, based on the cost of the hours of in–home services that they would otherwise have been authorized to receive under an IHSS–like program. Recipients have more flexibility in the use of these funds than they would in a program like IHSS. They can use these monthly sums to set wage levels; hire a provider; and purchase permissible goods that make it easier to remain at home—expenditures not permitted now under IHSS. Under the Cash and Counseling Model, a counselor (often a social worker) helps consumers craft spending plans; offers advice on hiring, supervising, and training a provider; and monitors use of the available funds. A bookkeeper from a financial management services agency assists the consumer in the paperwork required to pay a provider’s wages and withhold taxes.

Under the Cash and Counseling Model, Live–In Providers Could Potentially Qualify for an Exemption From the Overtime Requirement Under Federal Labor Regulations. Based upon our review of the federal labor regulations, it appears that the Cash and Counseling Model could potentially have the effect of classifying the consumer as the sole employer of a live–in provider. Under such a scenario, the consumer could be able to claim the live–in domestic service worker exemption from the requirement to pay overtime to a home care worker. In effect, this would mean that live–in providers could work more than 40 hours per week and receive the set wage for all hours worked. As we noted earlier, half of IHSS recipients have a live–in provider. The ability of consumers with live–in providers to claim the live–in domestic service worker exemption under a Cash and Counseling Model would depend largely on the operational details of the program. Additionally, consideration of such a significant change to the IHSS program should weigh the benefits to consumers with live–in providers against the overall policy merits of this new model of care. We therefore recommend the Legislature require DSS to report in budget hearings with its initial take on the policy merits and trade–offs of the Cash and Counseling Model as an option for IHSS recipients with live–in providers. We assess this modification of providing a Cash and Counseling Model to recipients with live–in providers in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Cash and Counseling Model for IHSS Recipients With Live–In Providers

|

Criteria

|

Assessment of Modification Relative to Governor’s Proposal

|

|

Costs incurred for overtime

|

- No change in costs to pay overtime.

- Reduced Provider Backup System costs.

|

|

Consumer choice

|

- Enhances the consumer choice of high–hour recipients with live–in providers, who could continue to receive all assistance from a single provider of their choice.

|

|

Administrative cost and complexity

|

- Substantial administrative activities—and thus costs and complexity—associated with providing the “counseling” component of the model.

- Assuming all IHSS recipients with live–in providers chose the Cash and Counseling Model and received quarterly visits from a counselor, the cost of social worker time for these visits could be roughly $20 million General Fund annually.

- Potential additional costs associated with financial management services.

|

|

Need for additional providers

|

- Reduces the number of additional providers that would need to be recruited.

|

If the Legislature wishes to work within the framework of the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime, then we recommend the following two changes related to implementation of the proposal.

Recommend Revision to Enforcement of Overtime Restriction for IHSS Providers. We described earlier that the Governor’s proposed one–year suspension of IHSS providers who claim overtime on two occasions—without any exceptions—raises concerns in that it could be unduly disruptive to some IHSS recipients. For example, if a provider does not receive the warning notice—because of a change of address or for some other justifiable reason—and as a result, claims overtime on two occasions, the recipient would lose his/her provider for a period of one year. The provider may also submit two timesheets simultaneously or in close succession—both claiming overtime—before he/she receives the warning notice. Short of appealing the suspension, the provider would have no recourse but to wait for the period of one year to elapse. In such instances, we find a one–year suspension to be unduly punitive to both provider and recipient. We therefore recommend the Legislature revise the enforcement of the overtime restriction by adding a suspension that is one month in duration prior to the one–year suspension. In effect, providers would be suspended for a period of one month if they claim overtime on two occasions. We find that a shorter suspension would have a similar deterrent effect as a one–year suspension in preventing IHSS providers from claiming overtime, but would not force a recipient to go without his/her preferred provider for an extended period of one year. We find that if a provider claims overtime on a third occasion, it would then be appropriate to suspend the individual for a period of one year.

Recommend Quarterly Reporting From DSS on Authorized Hours Versus Paid Hours. To increase legislative oversight of recipients’ access to service hours under the Governor’s overtime restriction, we recommend the Legislature require DSS to report quarterly on the total number of IHSS hours authorized compared to the total number of hours claimed by providers in each county statewide. A differential between these two indicators that is greater than the historical average may indicate a possible shortage of IHSS providers in a particular county.

We find the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime in the IHSS program has merit in that it complies with the federal labor regulations in a manner that controls costs without reducing authorized service hours for IHSS recipients. Our analysis finds that the Governor’s proposal would result in a net fiscal benefit to the state. We therefore believe the Governor’s proposal should be given consideration by the Legislature as a reasonable starting point for addressing the federal labor regulations in the IHSS program. Although our analysis finds that the Governor’s proposal results in a net fiscal benefit to the state, we raise various policy concerns with the proposal. If the Legislature wishes to proceed within the Governor’s proposed framework of restricting overtime, then we recommend the Legislature consider potential modifications to address the policy concerns raised. Ultimately, the Legislature would want to weigh its policy priorities against the cost of each modification in order to arrive at a suitable approach for addressing the budgetary impact of the federal labor regulations in the IHSS program.

Aside from the Governor’s proposal to restrict overtime in the IHSS program, we find his proposal to fund the costs of newly compensable IHSS work activities to be reasonable. In regards to the Governor’s proposal to provide a rate increase for DDS vendors, we find it reasonable to assume that vendors will incur increased administrative costs to minimize overtime payments. Because of current data limitations on the exact amount of these costs, we recommend DDS report to the Legislature—no later than May 1, 2016—on the results of the proposed rate increase on impacted vendors in order to assess whether it is appropriate on an ongoing basis.

Overview of IHSS. The IHSS program provides personal care and domestic services to certain individuals to help them remain safely in their own homes and communities. In order to qualify for IHSS, a recipient must be aged, blind, or disabled and in most cases have income below the level necessary to qualify for SSI/SSP cash assistance. Recipients are eligible to receive up to 283 hours per month of assistance with tasks such as bathing, dressing, housework, and meal preparation. Social workers employed by county welfare departments conduct an in–home IHSS assessment of an individual’s needs in order to determine the amount and type of service hours to be provided. The average number of hours that will be provided to IHSS recipients is projected to be 84 hours per month in 2014–15 (after accounting for a previously enacted service reduction explained below). In most cases, the recipient is responsible for hiring and supervising a paid IHSS provider—oftentimes a family member or relative.

The IHSS Program Receives Federal Funds as a Medi–Cal Benefit. For nearly all IHSS recipients, the IHSS program is delivered as a benefit of the state’s Medicaid health services program (known as Medi–Cal in California) for low–income populations. The IHSS program is subject to federal Medicaid rules, including the federal medical assistance percentage reimbursement rate for California of 50 percent of costs for most Medi–Cal recipients. For IHSS recipients who generally meet the state’s nursing facility clinical eligibility standards, the federal government provides an enhanced reimbursement rate of 56 percent referred to as Community First Choice Option (CFCO). Because of the large share of IHSS recipients eligible for CFCO—about 40 percent of the caseload—the average federal reimbursement rate is 54 percent for the IHSS program. The remaining nonfederal costs of the IHSS program are paid for by the state and counties, with the state assuming the majority of the nonfederal costs.

Counties’ Share of IHSS Costs Is Set in Statute. Budget–related legislation adopted in 2012–13 enacted a county MOE, in which counties generally maintain their 2011–12 expenditure level for IHSS—to be adjusted only for increases to IHSS providers’ wages (when negotiated at the county level through collective bargaining) and an inflation factor of 3.5 percent beginning in 2014–15. Under the county MOE financing structure, the state General Fund assumes all nonfederal IHSS costs above counties’ MOE expenditure level. In 2014–15, the county MOE is estimated to be $994 million, an increase of $34 million above the estimated revised county MOE for 2013–14. To the extent wage increases negotiated at the county level are implemented in the remainder of 2013–14 or in 2014–15, the individual county’s MOE will increase by a percentage share of the annual cost of those wage increases.

Year–to–Year Expenditure Comparison. The budget proposes $6.4 billion (all funds) for IHSS expenditures in 2014–15, which is a 4.9 percent net increase over estimated revised expenditures in 2013–14. General Fund expenditures for 2014–15 are proposed at $2 billion, a net increase of $84 million, or 4.4 percent, above the estimated revised expenditures in 2013–14. This net General Fund increase incorporates the $34 million increase in the county MOE (which offsets General Fund expenditures) and several other factors described below.

- Costs to Comply With New Federal Labor Regulations. Increase of $209 million ($99 million General Fund) in response to recent federal labor regulations (affecting overtime pay and other matters) to take effect January 1, 2015. Please refer to the “Human Services Compliance With Federal Labor Regulations” analysis in this report for more detail on, and our analysis of, this proposal.

- Increase in IHSS Basic Services Costs. Increase of $68 million ($35 million General Fund) because of (1) caseload growth of 1.3 percent and (2) higher costs per hour because of the increase in the state–mandated hourly minimum wage from $8 to $9 beginning July 1, 2014. (Because the state enacted the minimum wage increase, the county MOE is not adjusted to reflect cost increases associated with the new minimum wage.)

- CMIPSII—Transition to New Phase. Decrease of $40 million ($20 million General Fund) due to the transition from the design, development, and implementation phase to the maintenance and operation phase for the CMIPS II IT system that stores IHSS case records, provides program data reports, and authorizes IHSS provider payments. As of November 2013, all 58 counties have transitioned to CMIPS II.

- Partial Rollback of Reduction in Authorized Service Hours. Year–over–year increase of $15 million ($8 million General Fund) as a result of implementing current law that requires an ongoing 7 percent reduction in IHSS authorized service hours beginning in 2014–15, rather than the one–time 8 percent reduction in service hours that applied in 2013–14. Total General Fund savings from the 7 percent reduction are estimated to be $181 million in 2014–15. This 7 percent reduction in service hours is part of an IHSS settlement agreement—adopted by the Legislature—that resolves two class–action lawsuits related to previously enacted budget reductions.

New Services Costs Related to Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI). The budget also reflects an increase of $49 million in total expenditures ($22 million as reimbursement from the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) originating from the General Fund) for (1) increased IHSS hours for existing recipients as a result of the CCI and (2) new IHSS recipients who are expected to transition out of more costly institutional care settings and into IHSS because of the CCI. As part of the CCI, the IHSS program will shift from a Medi–Cal fee–for–service benefit to a Medi–Cal managed care plan benefit in certain counties beginning April 1, 2014. For more background on the CCI, please refer to The 2013–14 Budget: Coordinated Care Initiative Update.

Caseload Growth. The Governor’s budget assumes the average monthly caseload for IHSS in 2014–15 will be 453,417, an increase of 1.3 percent compared to the most recent estimate of the 2013–14 average monthly caseload.

LAO Comments on Overall Budget Proposal. We discuss elsewhere in this report the Governor’s proposal to respond to federal labor regulations as they apply to IHSS and DDS. The balance of the IHSS budget changes as outlined above appear reasonable. We have reviewed the caseload projections for IHSS as they relate to caseload growth in prior years and do not recommend any adjustments at this time. We note that the 2014–15 caseload estimate does not take into account a relatively small but likely increase in IHSS recipients as a result of the CCI. If we receive additional information that causes us to change our overall assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis.

The CCL division of DSS develops and enforces regulations designed to protect the health and safety of individuals in 24–hour residential care facilities and day care. The Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of $118 million ($36 million General Fund) for CCL in 2014–15. This represents an 11 percent increase above estimated 2013–14 total expenditures (and a 37 percent increase above estimated 2013–14 General Fund expenditures). This increase is primarily the result of (1) the Governor’s proposal to take steps to enhance the quality of CCL and (2) providing General Fund monies to backfill federal funds that were lost as a result of the reduction in the federal Social Services Block Grant. Below, we provide some background on CCL and the Governor’s proposal.

The CCL oversees the licensing of various facilities including child care centers, adult residential facilities, group homes, foster family homes, and residential care facilities for the elderly (RCFE). The division is also responsible for investigating any complaints lodged against these facilities and for conducting inspections of the facilities. The state monitors approximately 66,000 homes and facilities, which are estimated to have the capacity to serve over 1.3 million Californians. Additionally, DSS contracts with counties to license an additional 8,700 foster family homes and family child care homes.

CCL Staffing and Facility Monitoring. The roughly 66,000 homes and facilities statewide directly under the regulatory purview of CCL are primarily monitored and licensed by just over 460 licensing analysts. These licensing analysts are located in 25 regional offices throughout the state and are responsible for conducting annually about 24,000 inspections and 13,000 complaint investigations. Current law requires CCL to conduct random inspections on at least 30 percent of all facilities annually, and each facility must be visited no less than once every five years. Although the CCL has had difficulty meeting these time frames in the past, the division is generally meeting these time frames currently.

Past Budget Reductions Have Increased the Time Between Annual Visits. Prior to 2002–03, most facilities licensed by CCL were required to be visited annually. Budget–related legislation enacted in 2003 lengthened the intervals between visits for most facilities from one year to five years. Additionally, the legislation included “trigger” language that initially required CCL to randomly visit 10 percent of facilities each year. If, in a given year, the number of citations identified exceeded that of the prior year by 10 percent, the random visits that were required to be conducted would increase by an additional 10 percent. As a result of this trigger methodology, CCL is now required to randomly visit 30 percent of facilities each year, and the requirement that each facility be visited every five years continues.

The CCL Began to Use a Key Indicator Tool (KIT). As a method to assist CCL in achieving the required inspection frequency, the KIT was formally adopted by CCL in the fall of 2010. This tool allowed CCL to increase the number of enforcement visits licensing analysts were able to conduct within existing budget constraints. The KIT is a measurement tool that is designed to measure compliance with a small number of licensing standards to predict compliance with all of the remaining licensing standards. In other words, whether or not a facility is in compliance with certain measures is considered to be an indicator of whether it will be in compliance with all measures. Due to the reliance on key indicators, rather than the more comprehensive assessment, it takes less time for licensing analysts to conduct a KIT inspection than a more comprehensive inspection. Only facilities that are in generally good standing are eligible for the KIT inspection, and at any given point during a KIT inspection, a licensing analyst may discover issues that trigger a more comprehensive inspection. The DSS has partnered with Sacramento State University to evaluate the KIT process and expects to have more information and analysis of the KIT available in the spring of 2014.

Recent Issues at Licensed Facilities Have Gained Attention. Recent health and safety incidents at licensed facilities have gained the attention of the media and the Legislature. These include incidents of neglect and abuse, as well as evidence in general of inconsistent and inadequate oversight, monitoring, and enforcement of licensing standards.

In response to recent health and safety issues discovered at facilities licensed by CCL, the Governor’s budget proposes a comprehensive plan to reform the CCL program. The proposal includes an increase of 71.5 positions and $7.5 million ($5.8 million from the General Fund) for the support of this proposed plan as well as budget–related legislation. Below, we describe the main components of the proposal and provide our analysis and recommendations in conjunction with each component that is discussed in detail. Overall, we find the Governor’s proposal contains elements that seek to respond to the recent issues and shortcomings identified at CCL. Although we do not raise any particular concerns with the level of staff requested by the department, we recommend some modifications to the accompanying budget–related legislation.

There are currently over 7,500 RCFEs that are licensed by CCL for a capacity to provide care for about 175,000 people throughout the state. Historically, RCFEs have been considered to be different from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) because their purpose is to serve those with less acute medical needs than those who would qualify for skilled nursing home placement. However, as the population has aged, and the general policy goal of caring for people in the least restrictive setting has been emphasized, the role of the RCFEs has also changed. Although the populations at the RCFEs have changed to include those with more acute medical conditions, the regulatory and enforcement structure at CCL has not changed, and there are currently no staff in the division with medical expertise. Additionally, there are increasing numbers of corporations applying for licenses to operate multiple RCFEs in multiple regional office jurisdictions. Because the RCFEs that are part of a larger corporation are inspected by licensing analysts from various regional offices, it is difficult for CCL to recognize patterns of problems associated with specific corporations.

Begins to Develop Medical Expertise. The Governor’s budget proposes to establish a nurse practitioner at CCL to begin research on potential policy and regulatory changes that the department and Legislature should consider to ensure that there is adequate oversight of the RCFE population that is increasingly more medically fragile.

Establishes a Mental Health Populations Unit. In response to the changing needs of residents in RCFEs, and recent legislation that is expected to increase the number of facilities that treat individuals with mental health needs, the department proposes to establish four positions to create a mental health populations unit. This unit would create mental health and treatment expertise at CCL and be responsible for such things as developing regulations, answering policy questions from the field, and coordinating oversight activities with the DHCS.

Creates a Corporate Accountability Unit. The Governor’s budget proposes to establish two positions to create a corporate accountability unit that would be responsible for identifying and addressing issues of systemic noncompliance by RCFE operators with facilities in more than one of the geographic areas overseen by regional offices.