On May 13, 2014, the Governor released the 2014–15 May Revision to his annual budget proposal. The revision includes a higher forecast of revenues, offset in part by increased General Fund spending requirements under Proposition 98. In addition, the revision includes increased estimates for caseload costs in health and human services programs, as well as increased costs for state employee pensions. The preeminent new proposal in the May Revision is a plan to fully fund California’s teachers’ pension system in about 30 years. Below, we describe the administration’s latest projection of the General Fund condition and provide an overview of the major changes since the January budget proposal.

Projected 2014–15 General Fund Condition

Revised Proposed Reserve for End of 2014–15 Down Slightly From January. Figure 1 displays the administration’s projected General Fund condition in the May Revision. The Governor’s January budget plan proposed a reserve of $2.3 billion, comprised of $1.6 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)—the state’s rainy–day reserve created by Proposition 58—and a $693 million reserve in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties, the state’s traditional reserve. The administration’s latest forecast projects higher revenues for 2012–13, 2013–14, and 2014–15 combined, which are more than offset by higher General Fund requirements under Proposition 98, higher net revised cost estimates for programs, and new proposals. The Governor now proposes a $2.1 billion reserve, down slightly from January.

Figure 1

Governor’s May Revision General Fund Condition

Includes Education Protection Account (In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Prior–year fund balance

|

$2,429

|

$3,903

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

102,185

|

106,950a

|

|

Total resources available

|

$104,614

|

$110,853

|

|

Expenditures

|

$100,711

|

$107,766b

|

|

Ending fund balance

|

$3,903

|

$3,087

|

|

Encumbrances

|

$955

|

$955

|

|

Reserve

|

$2,948

|

$2,132

|

|

Budget Stabilization Account

|

—

|

$1,604

|

|

Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties

|

$2,948

|

528

|

Differences From January Budget. Figure 2 displays the major features of the Governor’s May Revision. The major changes to the budget include the following:

- Lower Revenues for 2012–13 (–$513 Million). The administration now estimates that personal income tax (PIT) revenues were $849 million lower in 2012–13. In addition, the May forecast reflects $321 million in higher estimated corporation tax (CT) receipts for 2012–13, with no change to the sales and use tax (SUT) forecast. Overall, the result is $513 million in lower estimated revenues for 2012–13.

- Higher Revenues for 2013–14 ($2 Billion). The administration’s forecast of PIT revenues for 2013–14 is $2.2 billion above January levels. (The administration’s January forecast had already revised 2013–14 PIT revenues upward by $3.5 billion over 2013 budget projections. The administration’s PIT forecast is now $5.7 billion above totals incorporated into the 2013–14 Budget Act.) The administration estimates that CT revenues in 2013–14 are up $136 million and SUT revenues are down $161 million from the January figures. Combined with other changes, the administration’s forecast for 2013–14 is up $2 billion.

- Higher Revenues for 2014–15 ($843 Million). The May Revision includes a relatively small adjustment to the administration’s forecast of General Fund revenues in 2014–15. Specifically, the administration projects higher PIT revenues ($474 million), higher CT revenues ($228 million), and lower SUT revenues ($248 million). After other changes, the administration’s forecast for 2014–15 is up $843 million.

- Higher General Fund Requirements Under Proposition98 ($659 Million). The administration’s lower revenue forecast for 2012–13 produces a greater than dollar–for–dollar decrease in General Fund spending under Proposition 98. Specifically, General Fund spending is down $524 million. The administration’s higher 2013–14 revenue forecast produces $1.8 billion in higher General Fund spending for Proposition 98 in that year. Despite the administration’s higher revenue forecast for 2014–15, the lower year–to–year change in General Fund revenues results in $600 million less General Fund spending on Proposition 98. Across the period, General Fund requirements under Proposition 98 are up $659 million relative to the January budget proposal.

- Higher Net Estimates of Costs ($1.6 Billion). The Governor’s May proposal includes several significant revisions to the January budget. Higher caseload costs, lower savings related to 1991 realignment, and various other adjustments increased health and human services costs by about $1.4 billion. Costs for state employee pensions are up $343 million under recent annual valuation approved by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) board. These amounts are offset by a nearly $200 million savings in the state’s debt–service costs.

- New Proposals to Pay Down Liabilities ($159 Million). Perhaps the most significant proposal in the May Revision is a plan to fully fund CalSTRS over a period of about 30 years. (This plan is discussed in detail later in this report.) Under the proposal, the state’s contribution to CalSTRS would increase by $59 million in 2014–15. In addition, the Governor proposes to pay down $100 million of the mandate obligation owed to cities, counties, and special districts.

- Other Spending Proposals ($176 Million). Senate Bill 103 (Chapter 2, Statutes of 2014) appropriated $687 million for drought assistance activities. Most of the expenditures in that package accelerated bond spending for water infrastructure. The May Revision proposes an additional $116 million in General Fund spending for drought assistance, including additional firefighter capacity and resources programs. The administration also proposes to increase the $100 million General Fund augmentation proposed in January for trial courts by $60 million.

Figure 2

Major Features of the Governor’s May Revision

2012–13, 2013–14, and 2014–15 Combined (General Fund Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Impact on Reserve

|

|

Governor’s January Budget Proposed Reserve for End of 2014–15

|

$2,284a

|

|

Higher Net Revenue Forecast

|

|

|

Lower 2012–13 revenues

|

–$513

|

|

Higher 2013–14 revenues

|

2,038

|

|

Higher 2014–15 revenues

|

843

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2,368)

|

|

Change in Proposition 98 Guarantee

|

|

|

Higher revenue forecast increases General Fund spending

|

–$659

|

|

Changes to Other Cost or Savings Estimates

|

|

|

Debt–service savings

|

$194

|

|

Higher firefighting costs in 2013–14

|

–90

|

|

Increased CalPERS costs

|

–343

|

|

Net cost increases in health and human services programs

|

–1,368

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$1,606)

|

|

Proposals to Pay Down Liabilities

|

|

|

Fully fund CalSTRS over about 30 years

|

–$59b

|

|

Pay down a portion of pre–2004 mandate obligation

|

–100

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$159)

|

|

Other Spending Proposals

|

|

|

Additional proposals to mitigate effects of drought

|

–$116

|

|

Increase trial court augmentation relative to January proposal

|

–60

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$176)

|

|

Net Other Changes

|

$80

|

|

Governor’s May Revision Proposed Reserve for End of 2014–15

|

$2,132c

|

Figure 3 displays our office’s projections of General Fund revenue through 2019–20, based on our office’s newly revised U.S. and California economic forecasts. (For tables summarizing our economic forecasts, refer to the Appendix of this publication.) Figure 4 displays the administration’s General Fund revenue projections through 2017–18, and Figure 5 compares recent revenue forecasts of our office and the administration for 2013–14 and 2014–15.

Figure 3

LAO Revenue Forecast

General Fund and Education Protection Account Revenues and Transfers (In Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

2019–20

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$64,154

|

$66,967

|

$73,012

|

$76,957

|

$80,477

|

$83,739

|

$83,014

|

$84,041

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

20,482

|

22,581

|

23,222

|

24,698

|

25,253

|

25,639

|

26,834

|

28,030

|

|

Corporation tax

|

8,070

|

8,398

|

8,980

|

9,553

|

10,113

|

10,604

|

11,069

|

11,566

|

|

“Big Three” Taxes

|

($92,706)

|

($97,945)

|

($105,214)

|

($111,208)

|

($115,843)

|

($119,982)

|

($120,918)

|

($123,638)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,222

|

$2,271

|

$2,368

|

$2,490

|

$2,580

|

$2,668

|

$2,756

|

$2,832

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,617

|

2,164

|

2,414

|

2,105

|

2,057

|

2,081

|

2,059

|

2,038

|

|

Transfers and loans

|

1,813

|

347

|

–803

|

–1,124

|

–832

|

–261

|

239

|

239

|

|

Totals

|

$99,357

|

$102,727

|

$109,193

|

$114,679

|

$119,648

|

$124,470

|

$125,972

|

$128,747

|

Figure 4

Administration Revenue Forecast

General Fund and Education Protection Account Revenues and Transfers (In Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$64,484

|

$66,522

|

$70,238

|

$74,444

|

$78,082

|

$82,029

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

20,482

|

22,759

|

23,823

|

25,686

|

26,267

|

26,775

|

|

Corporation tax

|

7,783

|

8,107

|

8,910

|

9,644

|

10,034

|

10,292

|

|

“Big Three” Taxes

|

($92,749)

|

($97,388)

|

($102,971)

|

($109,774)

|

($114,383)

|

($119,096)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,221

|

$2,287

|

$2,382

|

$2,499

|

$2,584

|

$2,672

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,619

|

2,163

|

2,400

|

2,076

|

2,034

|

2,098

|

|

Transfers and loans

|

1,813

|

347

|

–803

|

–1,124

|

–832

|

–261

|

|

Totals

|

$99,402

|

$102,185

|

$106,950

|

$113,224

|

$118,169

|

$123,605

|

|

Difference From LAO Forecast

|

$44

|

–$542

|

–$2,242

|

–$1,454

|

–$1,479

|

–$865

|

Figure 5

Comparing LAO and Administration Revenue Forecasts for 2013–14 and 2014–15

General Fund and Education Protection Account Revenues and Transfers (In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

|

2014–15

|

|

LAO Nov. 2013

|

DOF Jan. 2014

|

DOF May 2014

|

LAO May

2014

|

LAO Nov. 2013

|

DOF Jan. 2014

|

DOF May 2014

|

LAO May

2014

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$66,002

|

$64,287

|

$66,522

|

$66,967

|

|

$71,363

|

$69,764

|

$70,238

|

$73,012

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

22,809

|

22,920

|

22,759

|

22,581

|

|

23,561

|

24,071

|

23,823

|

23,222

|

|

Corporation tax

|

8,278

|

7,971

|

8,107

|

8,398

|

|

8,851

|

8,682

|

8,910

|

8,980

|

|

“Big Three” Taxes

|

($97,089)

|

($95,178)

|

($97,388)

|

($97,945)

|

|

($103,775)

|

($102,517)

|

($102,971)

|

($105,214)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,163

|

$2,143

|

$2,287

|

$2,271

|

|

$2,343

|

$2,297

|

$2,382

|

$2,368

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,254

|

2,480

|

2,163

|

2,164

|

|

1,874

|

2,046

|

2,400

|

2,414

|

|

Transfers and loans

|

342

|

346

|

347

|

347

|

|

–375

|

–765

|

–803

|

–803

|

|

Totals

|

$101,847

|

$100,147

|

$102,185

|

$102,727

|

|

$107,617

|

$106,094

|

$106,950

|

$109,193

|

LAO Revenue Forecast Somewhat Higher Than Administration’s. Across the four fiscal years (2011–12 through 2014–15), our General Fund revenue forecast is $2.5 billion higher than the administration’s. Our forecast is slightly lower than the administration’s for 2012–13, but higher by larger and varying amounts in later years. In 2013–14, we forecast $542 million more General Fund revenues than the administration. For 2014–15—reflecting our office’s economic forecast, including our assumptions concerning the stock market—we project $2.2 billion more in General Fund revenues than the administration. Thereafter, our forecast and the administration’s drift closer together, and by 2017–18 (the last year of the administration’s forecast) our office forecasts just $865 million more in revenue than the administration. The routine variability of California’s General Fund revenues means that the $2.2 billion difference between our revenue forecast and the administration’s for 2014–15 is not that large in the whole scheme of things. While our best estimates right now are for General Fund revenues to be over $2 billion higher than the administration’s projections in 2014–15, changes in asset markets and the economy could materialize that would result in less or more tax collections than our office now projects.

2011–12 and 2012–13 Revenues: Accruals Still Changing. Both the administration’s projections and our own continue to make budgetary accounting adjustments related to revenues for the 2011–12 and 2012–13 fiscal years. These relate largely to the state’s complex, obscure revenue accrual practices, which take revenue collected in one fiscal year and move it back to prior fiscal years. (We have discussed accruals in several prior publications.) For 2011–12, our lower Proposition 30 accrual estimates result in $268 million of a lower entering fund balance for the General Fund than the administration. (We suspect that these 2011–12 Proposition 30 accrual adjustments may continue through at least the presentation of the Governor’s 2015–16 budget plan in January 2015 as the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) continues to analyze 2012 collection data. If these 2011–12 adjustments are finalized on January 10, 2015, that would be about 925 days after the 2011–12 fiscal year ended.)

For 2012–13, the administration has reduced its General Fund PIT estimate by $849 million since January. The primary reason for this change was a reduction in a specific category of accruals, largely separate from the Proposition 30 accruals mentioned above. Proposition 30 accrual changes also contributed to the lowering of the administration’s General Fund PIT estimate for 2012–13. Our office has reduced its 2012–13 PIT estimates for similar reasons, as we attempt to incorporate these technical accrual practices into our own revenue estimates. As we have noted in the past, changes in accruals can cause revenue estimates to be off by hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. The reduction in 2012–13 PIT revenues is a good example of this.

2013–14 Revenues: June Collections Loom. June is a major month for PIT collections, as high–income taxpayers and others make their second quarterly “estimated payments,” principally on capital gains and business income. These payments are due on June 15 and typically flow in a few days thereafter in large amounts—a few days after the Legislature’s constitutional deadline for passing a 2014–15 state budget plan. The administration assumes that June 2014 net PIT collections (for all state funds) total $8.9 billion—mostly from estimated payments. Our office assumes that June 2014 net PIT collections total around $9.5 billion. This difference—along with accrual and other differences—largely accounts for our office’s $445 million higher PIT forecast for 2013–14. For this year’s first estimated payment month—April 2014—quarterly estimated payments were $2.3 billion, or 14 percent, above those collections in April 2013. Our forecast assumes that June 2014 estimated payments are about 20 percent above June 2013 levels, which seems reasonable to us based on continued strength in stock and house prices.

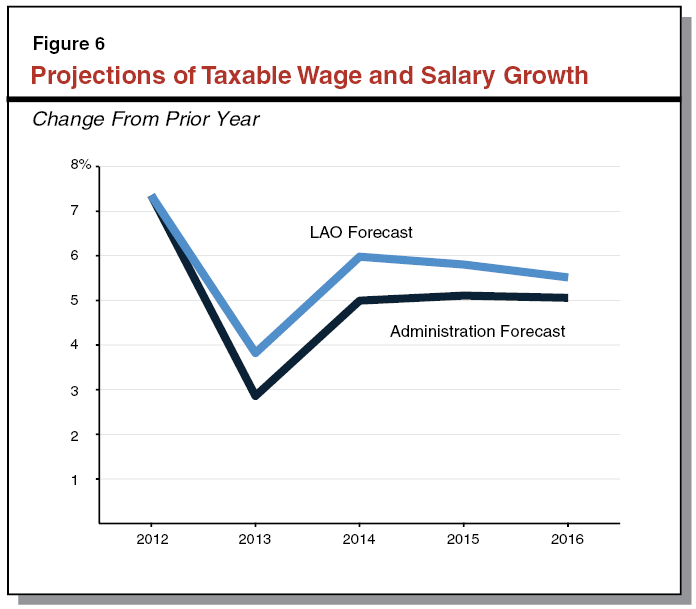

2014–15 Revenues: Higher LAO Capital Gains and Wage Assumptions. Our forecast of 2014–15 General Fund PIT revenues is $2.8 billion above the administration’s. Based on our office’s economic forecast assumptions—including assumptions about near–term trends in stock and home prices—we forecast notably higher net capital gains realizations by California resident taxpayers in 2014–15. Specifically, our office assumes realizations of $136 billion of these net capital gains in 2014, dropping to $123 billion in 2015. The administration, by contrast, assumes $105 billion in 2014, dropping to $89 billion in 2015. These differences alone result in about $3 billion more in 2014–15 capital gains taxes in our office’s forecast. Our office also assumes faster growth in taxable wages and salaries—the largest category of taxable income—as shown in Figure 6. The difference in our wage and salary projection generates around $1 billion of a revenue difference between our office and the administration in 2014–15. In some other revenue categories, such as other investment income and certain business income taxed through the PIT, the administration has higher revenue projections than our office, resulting in the overall net revenue difference of $2.8 billion for the fiscal year.

In the coming months, it will be important to remember that 2013 capital gains and certain other income categories were depressed as taxpayers “accelerated” realizations of large amounts of income to 2012 to avoid higher federal taxes that took effect in 2013. Many taxpayers are able to make estimated payments during the course of the year based on their taxes for the prior year. As a result, there appears to us a strong possibility that many taxpayers will make estimated payments in 2014 based on their smaller tax liabilities in 2013, which could result in an unusually large amount of “settle up” by estimated payment filers when they make estimated, final, or extension payments in early 2015. For example, January and April 2015 could be unusually large PIT collection months. If this is the case, trends on 2014–15 revenue collections may not become clear until the second half of the fiscal year. In fact, if more taxpayers wait until early April 2015 to settle up, there is a greater chance that monthly revenue collections will fall short of some months’ estimates during the first several months of 2014–15.

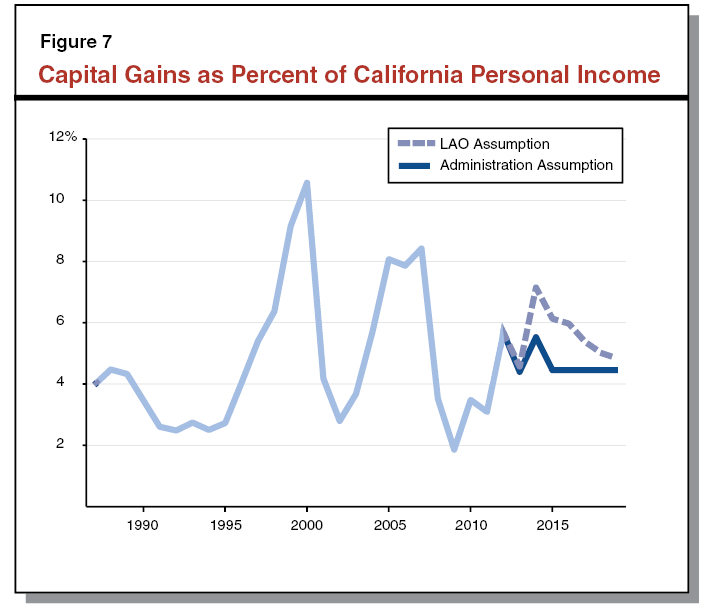

Estimating Capital Gains Requires Making Assumptions About Asset Prices. The chart frequently displayed by the Governor that shows the wildly fluctuating levels of taxable capital gains tells an important cautionary tale about California budgeting. Elevated levels of capital gains and other volatile state revenue sources have produced spikes in state revenues that have not lasted long, and the state’s budget has been left deeply out of balance after several prior revenue spikes ended. While stock and house prices have both exceeded our office’s prior projections recently, asset markets are not nearly as “overvalued” as they were in past bubbles by some measures. Figure 7, for instance, shows historical and projected capital gains (from both our office and the administration) as a percentage of California personal income. The projected levels are both currently well below the levels of the “dot–com” bubble. Figure 7 shows that, as compared to the size of the California economy, capital gains are below peaks reached in prior bubbles. Our 2014 capital gains projection reaches 7.2 percent of personal income. Other measures, however, indicate that certain components of the stock market and housing prices in some areas of California may be overvalued or close to it. In any event, no economic or budget forecaster can reliably predict when stock and other asset prices will fall substantially.

Yet, every California budget forecast must make assumptions and projections related to capital gains. We base ours on historical data about capital gains and assumptions concerning the future trend of stock and house prices. With regard to the stock market, our office currently assumes that the S&P 500 stock index will remain fairly flat at between 1,850 and 1,900 through the end of 2014 and grow slowly thereafter in line with the general economy. We assume the Nasdaq stock index—important for technology firms in California and elsewhere—will stagnate between 4,050 and 4,100 through the rest of 2014. Despite these modest near–term stock price forecasts, stock prices this year are elevated substantially above levels of just one year ago. On May 15, for example, the S&P 500 was 13 percent above its levels of one year prior. This means that, even if markets are flat or they decline somewhat in the coming months, California investors selling stocks they bought a year or more ago often will realize substantial gains, which, in turn, will generate tax liabilities due to the state. The administration’s economic forecast—which is posted online—lists identical assumptions about S&P 500 performance through 2016 (both the administration and our office use the same national economic firm, which provides certain U.S. economic data and analysis).

In Near Term, LAO Capital Gains Assumptions Consistent With Recent Data. We believe that our office’s revenue forecast better accounts for the fact that asset prices, such as stock prices, are substantially higher than they were one year ago. Our capital gains forecast—like the administration’s and those of some other forecasters—now starts with an assumption about what capital gains would have been but for the changes in federal tax law at the beginning of 2013. (Following development of this “baseline” capital gains forecast, forecasters then “accelerate” some capital gains realizations that would have occurred in 2013 to 2012 to match the actions of investors in response to the changed federal tax laws.) In its baseline capital gains forecast, the administration assumes that capital gains in 2014 are equal to those that would have been realized in 2013 but for the federal changes, despite recent gains in asset prices. In our view, such stagnation is unlikely under the stock market assumptions in both of our economic forecasts. Our office’s baseline capital gains forecast for 2014 is 14 percent above 2013 levels, consistent with our economic forecast, as well as recent trends in asset prices and estimated payments.

These Assumptions Can Prove to Be Wrong. While we believe our near–term capital gains forecast assumptions are consistent with recent economic and tax collection data, it is important for policy makers and the public to understand that the assumptions underlying any such capital gains forecast are subject to great uncertainty. For example, we developed one scenario in which stock prices decline 15 percent over the next year. In this scenario, our PIT projections dropped by $1.4 billion for 2014–15 and $4.2 billion for 2015–16 due to reduced capital gains alone (other taxable income sources also would decline in such a scenario). Conversely, a scenario in which stock prices climbed 15 percent over the next year produced similar amounts of increased revenue from capital gains relative to our current forecast. More broadly, the nation is now five years into an economic expansion, which is about the average length of such an expansion in the post–World War II era. This fact, our downside stock market scenario, and the various charts showing the ebbs and flows of capital gains over time all emphasize the importance of an important state budgeting goal: setting aside reserves when revenues or capital gains climb sharply, as seems to be happening now.

Lower LAO Sales Tax Forecast. Our General Fund sales tax revenue forecast is $178 million lower than the administration’s for 2013–14 and$601 million lower than the administration’s for 2014–15. The difference between our sales tax forecast and the administration’s partly reflects differences in our forecasts for residential construction. Residential construction generates some taxable sales directly (through purchases of construction materials and other goods), but it also serves as a proxy for consumer confidence, which is difficult to measure directly. Our short–term construction forecast is lower than the administration’s because construction has underperformed our expectations in recent forecasts. Our long–term forecast is lower due to underlying demographic trends, including population growth, household formation, and average household size, that dictate how many new housing units are built each year. As a result, our forecast for total residential building permits is 12 percent lower than the administration’s in 2014 and remains lower throughout the forecast period, plateauing at around 130,000 permits per year in 2017.

CT Remains Difficult to Project. The CT revenue collections in 2013–14 have been somewhat higher than the administration projected in January because refunds have been substantially lower than the administration estimated at that time. Both our forecast and the administration’s take this into account. However, the administration expects about $550 million in refunds to be paid in May and June of 2014. During this period last year, less than $150 million was refunded to taxpayers. Our forecast for CT “agency cash” revenue collections in 2013–14 is a few hundred million dollars higher than the administration because we assume that much less will actually be refunded over the next two months. Because of the state’s complicated accrual policies, our lower level of projected 2013–14 refunds has a positive effect on CT revenues booked to 2012–13. We acknowledge the possibility that refunds in May and June 2014 could either be closer to the administration’s estimates or below our estimates.

Forecasting CT revenue continues to be challenging. The FTB analyzes data that it, the administration, and our office all use to estimate the revenue effects of recent CT policy changes adopted by the state, including the adoption of a mandatory single sales apportionment factor with passage of Proposition 39 (2012) and the end of the suspension in the use of net–loss carryover deductions. In addition, changes in corporate income taxable in California was historically highly related to trends in national corporate income. Over the past five years, however, this relationship has significantly weakened to the point at which estimates of national corporate income (a key variable in both our revenue forecasting model and the administration’s) have become less useful for this purpose. It is unclear whether this is due to state–level policy changes or other factors. As we have noted in prior publications, it will take several years before data is available to help us address these forecasting uncertainties.

Funding for schools is largely governed by a set of constitutional formulas established by Proposition 98, approved by voters in 1988. Most importantly, Proposition 98 established a funding requirement commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. The minimum guarantee is determined by various factors, including General Fund revenues, per capita personal income, and K–12 average daily attendance (ADA). The guarantee is funded by state General Fund and local property tax revenues. Funding for schools, the California Community Colleges (CCC), state–subsidized preschool programs, and various other state education programs count toward meeting the guarantee. Below, we provide an overview and assessment of the May Revision Proposition 98 package.

Proposition 98 Spending Increases $242 Million Over Three–Year Period. As Figure 8 shows, the May Revision lowers Proposition 98 spending by $547 million in 2012–13 and $700 million in 2014–15 but increases spending by $1.5 billion in 2013–14—for a net increase in spending of $242 million over the period. Funding for both schools ($229 million) and community colleges ($13 million) increases over the period. As shown in the figure, Proposition 98 General Fund costs are down in 2012–13 and 2014–15 but up in 2013–14. In 2013–14, these costs are up $1.8 billion due to the combined effect of the increase in the minimum guarantee and lower anticipated growth in local property tax revenues for that year.

Figure 8

Changes in Proposition 98 Funding

(In Millions)

|

|

January

|

May

|

Change

|

|

2012–13 Minimum Guarantee

|

$58,342

|

$57,795

|

–$547

|

|

By Segment:

|

|

|

|

|

Schools

|

$51,634

|

$51,119

|

–$515

|

|

Community colleges

|

6,149

|

6,117

|

–32

|

|

Othera

|

559

|

559

|

—

|

|

By Fund Source:

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$42,207

|

$41,682

|

–$524

|

|

Local property taxes

|

16,135

|

16,112

|

–23

|

|

2013–14 Minimum Guarantee

|

$56,813

|

$58,302

|

$1,489

|

|

By Segment:

|

|

|

|

|

Schools

|

$49,995

|

$51,363

|

$1,368

|

|

Community colleges

|

6,233

|

6,355

|

121

|

|

Othera

|

585

|

585

|

—

|

|

By Fund Source:

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$40,948

|

$42,731

|

$1,783

|

|

Local property taxes

|

15,866

|

15,572

|

–294

|

|

2014–15 Minimum Guarantee

|

$61,559

|

$60,859

|

–$700

|

|

By Segment:

|

|

|

|

|

Schools

|

$54,250

|

$53,626

|

–$624

|

|

Community colleges

|

6,723

|

6,646

|

–76

|

|

Othera

|

587

|

587

|

—

|

|

By Fund Source:

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$45,062

|

$44,462

|

–$600

|

|

Local property taxes

|

16,497

|

16,397

|

–100

|

Estimates of Local Property Taxes Down $417 Million Over Three–Year Period. Estimates of local property tax revenue growth are down over the period for various reasons. In 2012–13, the small drop in local property tax revenue growth is due primarily to an upward revision in “excess tax revenues,” which in turn reduces the amount of local revenue that offsets Proposition 98 costs. (Excess tax revenues reflect local revenues that some school districts, county offices of education, and community colleges receive beyond their general purpose funding levels set by the state. These excess revenues are excluded from the calculation of Proposition 98.) In 2013–14, property tax revenues are $294 million lower due to higher estimates of excess taxes together with a slightly lower rate of growth in local property values. In 2014–15, local property tax estimates decrease by $100 million primarily due to an increase in the estimated amount of local property taxes that schools and community colleges must transfer to cities and counties under current law.

2012–13 Minimum Guarantee Down $547 Million. The Governor’s May Revision estimate of the 2012–13 minimum guarantee is $57.8 billion. Of the $547 million decrease in the minimum guarantee from the January estimate, $533 million is due to General Fund revenues being lower than in January. The minimum guarantee decreases more than the decrease in General Fund revenues as a result of Test 1 being operative in 2012–13 and the state having a large required maintenance factor payment (as is also the case in 2014–15). The small remaining drop in the 2012–13 minimum guarantee is the net effect of various adjustments, including the small reduction in property tax revenues noted above.

2013–14 Guarantee Up $1.5 Billion. The Governor’s revised estimate of the 2013–14 minimum guarantee is $58.3 billion. The $1.5 billion increase from the January estimate is due primarily to higher General Fund revenues coupled with a higher year–to–year growth rate (partly due to the downward revision to prior–year General Fund revenues). The guarantee also increases slightly due to an upward revision to the K–12 ADA estimate (described below). Because Test 3 is operative in 2013–14, the minimum guarantee is sensitive to changes in both General Fund revenues and K–12 ADA.

2014–15 Guarantee Down $700 Million. Although the Governor’s estimates of 2014–15 General Fund revenues are higher than in January, his revised estimate of the minimum guarantee ($60.9 billion) is down $700 million from the January level. The drop in the minimum guarantee is primarily due to a smaller required maintenance factor payment, which, in turn, results from smaller year–to–year growth in General Fund revenues (due to General Fund revenues under the May Revision increasing more in 2013–14 than 2014–15). As in 2012–13, Test 1 is operative in 2014–15 and the maintenance factor payment is highly sensitive to changes in General Fund revenues.

Continues to Pay Down All Outstanding Deferrals, but Changes Timing. All of the changes noted above result in little new Proposition 98 spending over the period. The largest change in the Proposition 98 package relates to the scoring of school and community college deferrals. As in the Governor’s budget, the May Revision provides a total of $6.4 billion to eliminate all school and community college deferrals by the end of 2014–15, but the May Revision attributes smaller deferral paydowns to 2012–13 and 2014–15 and a larger paydown to 2013–14 (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Changes to Governor’s Deferral Paydown Plan

(In Millions)

|

|

January

|

May

|

Change

|

|

2012–13

|

|

|

|

|

Schools

|

$1,813

|

$1,295

|

–$518

|

|

Community colleges

|

194

|

139

|

–55

|

|

Subtotals

|

($2,007)

|

($1,433)

|

(–$574)

|

|

2013–14

|

|

|

|

|

Schools

|

$1,520

|

$2,781

|

$1,260

|

|

Community colleges

|

163

|

296

|

134

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,683)

|

($3,077)

|

($1,394)

|

|

2014–15

|

|

|

|

|

Schools

|

$2,238

|

$1,496

|

–$742

|

|

Community colleges

|

236

|

158

|

–78

|

|

Subtotals

|

($2,474)

|

($1,653)

|

(–$820)

|

|

Total Proposed Deferral Paydown

|

$6,164

|

$6,164

|

—

|

Slight Increase in LCFF Costs Due to Higher–Than–Anticipated ADA. As shown in Figure 10, the May Revision maintains the proposed $4.5 billion augmentation for second–year implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The May Revision also updates underlying ADA estimates, which in turn affect total LCFF costs. Specifically, the May Revision estimates ADA will grow 0.33 percent rather than 0.01 percent in 2013–14 (reflecting about 19,000 additional ADA) and assumes the higher associated ADA count moving forward. The May Revision estimates ADA in 2014–15 will decrease 0.11 percent (compared to a decline of 0.12 percent assumed in January). These revised ADA estimates increase LCFF costs by $103 million in 2013–14 and $121 million in 2014–15.

Figure 10

Changes in 2014–15 Proposition 98 Spending

(In Millions)

|

|

January

|

May

|

Change

|

|

Crosscutting K–14 Adjustments

|

|

|

|

|

Deferral paydown

|

$2,474

|

$1,653

|

–$820

|

|

K–14 COLA

|

82

|

80

|

–1

|

|

Prior–year adjustments

|

–2,784

|

–2,784

|

—

|

|

Proposition 39 adjustments

|

–101

|

–112

|

–11

|

|

Other changes

|

—

|

–18

|

–18

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

LCFF implementation

|

4,498

|

4,498

|

—

|

|

K–12 pupil testing

|

56

|

54

|

–2

|

|

LCFF attendance growth

|

7

|

128

|

121

|

|

FCMAT

|

—

|

1

|

1

|

|

Attendance growth for categorical programs

|

–18

|

–1

|

17

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

Student Success and Support

|

200

|

200

|

—

|

|

Enrollment growth

|

155

|

140

|

–15

|

|

Deferred maintenance (one–time)

|

88

|

148

|

61

|

|

Instructional equipment (one–time)

|

88

|

—

|

–88

|

|

Community college technical assistance teams

|

3

|

3

|

—

|

|

CTE funding (one–time)

|

—

|

50

|

50

|

|

Internet equipment (one–time) and connectivity

|

—

|

6

|

6

|

|

Total Changes

|

$4,746

|

$4,046

|

–$700

|

Other Notable Spending Changes. The May Revision contains a few other notable Proposition 98 spending changes—mostly for community colleges. The May Revision rescinds the January proposal to provide $87.5 million (one–time) for instructional equipment but provides an additional $60.5 million (one–time) for maintenance projects at community colleges. In addition, the May Revision provides $50 million (one–time) for the community colleges to undertake certain activities relating to career technical education (CTE) and $6 million ($4.6 million ongoing, $1.4 million one–time) for Internet connectivity and networking equipment. The May Revision reduces CCC enrollment growth from 3 percent to 2.75 percent and recognizes the updated K–14 cost–of–living adjustment of 0.85 percent (down slightly from 0.86 percent assumed in January). The May Revision also reappropriates $27 million in unspent prior–year Proposition 98 funds for one–time grants to improve K–12 Internet connectivity.

Per–Pupil Programmatic Funding Is Virtually Unchanged From January. Because the May Revision makes few programmatic adjustments from the Governor’s January budget, K–12 per–pupil funding is virtually unchanged. Almost identical to the January budget, K–12 per–pupil funding under the May Revision goes up from $7,933 in 2013–14 to $8,717 in 2014–15—a year–to–year increase of $784 (10 percent). Because the bulk of May Revision spending changes for the community colleges are one–time, per–student ongoing programmatic funding also remains virtually unchanged from January. Under the May Revision, per–student funding at CCC increases from $5,636 in 2013–14 to $5,828 in 2014–15—a year–to–year increase of $192 (3.4 percent).

Overall Approach Continues to Be Sound. If the Legislature were to adopt the administration’s May Revision estimates of the minimum guarantee, we believe the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 spending package—with a balance of one–time and ongoing proposals—is sound. Most notably, we believe the Governor’s basic packaging approach—maintaining a large ongoing augmentation for LCFF and adjusting deferral paydowns across the three–year period to align with revised estimates of the minimum guarantee—is reasonable. In addition, we believe the Governor’s decision to devote additional funding to deferred maintenance projects at the community colleges is appropriate. In both of these cases, the May Revision largely builds off of earlier January proposals. Though we have some concerns with the Governor’s new spending proposals (as discussed in more detail below), we believe using some of the additional May Revision Proposition 98 funds for one–time purposes is prudent. By reserving these funds for one–time purposes, the state would minimize the potential disruption to schools and community colleges were revenues ultimately to come in lower (due either to typical volatility or an earlier–than–expected economic slowdown).

Some New Proposition 98 Spending Proposals Appear Either Unnecessary or Premature. Though the May Revision contains little new Proposition 98 spending, we have concerns with some of the Governor’s new proposals. Most notably, we believe the proposed $50 million for CCC CTE activities is duplicative of several other existing CTE programs. In addition, the administration has not been able to provide adequate detail and justification for its new CCC and K–12 Internet connectivity proposals.

Notable Differences in Estimates of General Fund Revenues and Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee. Though the May Revision spending package is reasonable within the context of the administration’s estimates of revenues and the minimum guarantee, we have notably different estimates. As discussed earlier in this report, our estimates of General Fund revenues are higher than the administration’s in 2013–14 and 2014–15. Largely due to these differences, our estimate of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is higher than the administration’s in both years (see Figure 11 below). Though the difference in the minimum guarantee is relatively small for 2013–14 ($313 million), the difference is notable for 2014–15 ($2.2 billion).

Figure 11

Comparing Administration and LAO Estimates of Minimum Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Governor’s May Revision

|

$58,302

|

$60,859

|

|

General Fund

|

42,731

|

44,462

|

|

Local property taxes

|

15,572

|

16,397

|

|

Base property taxesa

|

(15,293)

|

(16,245)

|

|

RDA revenue

|

(1,095)

|

(811)

|

|

Excess taxes

|

(–817)

|

(–659)

|

|

LAO May Estimates

|

$58,615

|

$63,097

|

|

General Fund

|

42,825

|

46,259

|

|

Local property taxes

|

15,790

|

16,837

|

|

Base property taxesa

|

(15,307)

|

(16,462)

|

|

RDA revenue

|

(1,071)

|

(1,008)

|

|

Excess taxes

|

(–588)

|

(–633)

|

|

Difference

|

$313

|

$2,237

|

|

General Fund

|

95

|

1,797

|

|

Local property taxes

|

218

|

440

|

|

Base property taxesa

|

(14)

|

(216)

|

|

RDA revenue

|

(–25)

|

(198)

|

|

Excess taxes

|

(229)

|

(26)

|

Local Property Tax Estimates Also Vary Notably. In addition to having different General Fund revenue estimates for 2013–14 and 2014–15, we have notably different local property tax estimates than the administration. Our local property tax revenues are a total of $658 million higher than the administration’s estimates across the two years ($218 million higher in 2013–14 and $440 million higher in 2014–15). As discussed in more detail below, the differences in our estimates of excess local property tax revenues and revenues redirected from redevelopment agencies (RDAs) are particularly significant. (We do not have major differences in our baseline property tax forecast. The administration forecasts assessed property value will grow 4.2 percent in 2013–14 and 7 percent in 2014–15, similar to our estimates of assessed value for these years.)

Excess Property Tax Estimates Vary Due to Differences in Estimation Methods. Whereas the administration’s estimate of excess property taxes does not account for recent changes in school finance, our estimates do reflect these changes. Prior to 2013–14, excess taxes were calculated relative to a school district’s revenue limit funding. If a district’s property tax revenues were greater than their revenue limit requirement, the revenues received above the revenue limit requirement were considered excess taxes. (As discussed above, excess tax revenues are excluded from the Proposition 98 calculation.) In 2013–14, the state combined funding for revenue limits and more than 30 categorical programs into the LCFF. Beginning in 2013–14, excess tax revenues will be calculated based on a district’s LCFF entitlement. Because a school district’s LCFF funding will be significantly higher than its 2012–13 revenue limit funding, the amount of excess tax revenues should decrease in 2013–14, resulting in a corresponding increase in the amount of Proposition 98 local property tax revenues available to offset General Fund costs. The administration’s estimates, however, do not account for these changes in school funding and are instead calculated based on the prior school finance model. As a result, we believe the administration overstates General Fund costs by $229 million in 2013–14. Despite the fundamental difference in estimation method, 2014–15 estimates are much closer, with the administration’s estimate of General Fund costs only $26 million higher than our estimate.

RDA Revenue Estimates Also Vary. Our estimate of 2014–15 RDA revenues flowing to schools and community colleges is $198 million higher than the May Revision estimate. The administration’s estimate assumes RDA revenues for schools and community colleges is lower year over year because of an anticipated increase in the amount of outstanding RDA obligations as well as delays in the distribution of RDA assets due to pending litigation. Although these factors likely will reduce RDA revenues in 2014–15, we forecast a much smaller year–to–year reduction in the amount of RDA revenues that schools and community colleges would receive.

Spending Options Linked With Different Levels of Budget Risk. Were the Legislature to adopt our higher General Fund and local property tax revenue estimates and recognize the higher resulting Proposition 98 minimum guarantee across the period, it would have corresponding decisions to make regarding how to adjust its Proposition 98 spending package. The Legislature has various Proposition 98 options to consider. The option associated with the least amount of downside risk would be to set aside the entire amount associated with our higher estimates of the minimum guarantee. Later in the fiscal year, if updated revenue estimates indicated the guarantee was higher, then the Legislature at that time could settle up the minimum guarantee by appropriating available funds for any high–priority one–time purpose (such as paying down the mandate backlog). A slightly different approach that still has little risk would be to declare the Legislature’s intent to use the funds in a specified way but wait to allocate the funds until certain stated revenue conditions have been met. For example, the Legislature could specify that it intends to distribute a portion of higher Proposition 98 funds on an ADA basis, with retiring unpaid mandate claims having first call on the funds and implementing the new academic standards and assessments having second call on the funds (with any one–time educational purpose allowable for remaining funds). Under this option, the Legislature would signal to schools how revenues were to be used if they materialized, but the funds would be allocated to districts only after updated revenue estimates showed the expenditures could be supported. Compared to these two low–risk strategies, a somewhat riskier approach would be to allocate at least some one–time funding to schools and community colleges now.

Established in 1913, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) administers pension programs for 868,000 members—equivalent to about 2 percent of California’s population. CalSTRS members are current, former, and retired teachers and administrators of school and community college districts, as well as their beneficiaries. As discussed in our recent publication, Addressing California’s Key Liabilities, CalSTRS has not been appropriately funded for most of its 101–year history. As a result, the system has considerable unfunded liabilities.

Large Unfunded Liabilities. “Fully funding” a pension system means that the future benefits already earned by members are 100 percent funded by assets on hand. Actuaries make assumptions about how long members will live and work, how much their pay will rise in the future, and how much the assets will grow with future investment returns. Typically, pension systems set employer and, in some cases, employee pension contributions to ensure that 100 percent funding is achieved or retained over the long term. CalSTRS, however, was 100 percent funded for just a brief period in the late 1990s. Around that time, the state increased member benefits and reduced its contributions to CalSTRS. These actions—combined with major investment losses during some recent periods and other factors—contributed to the unfunded liability estimated by CalSTRS to total $74 billion at the end of 2012–13. This means that the system is only 67 percent funded. (These estimates reflect CalSTRS’ current actuarial assumptions, including an assumed average annual investment return of 7.5 percent over the long term. If lower investment returns were assumed, the unfunded liabilities would be much greater.)

State Action Required. State law provides that CalSTRS members are entitled to a financially sound pension system. Unlike other pension systems, however, CalSTRS itself has no authority to change contribution rates of its employers or others. Under existing law, only the Legislature can increase contributions of school districts, teachers, and/or the state in order to address the system’s liabilities.

Existing Law Provides No Clear Answers. There have been many varied legal opinions about CalSTRS over time. In the May Revision, the administration asserts that one statute in the Education Code means the state “is not responsible” for much or most of CalSTRS’ unfunded liabilities—those created by the state’s own actions on benefits and contributions about 15 years ago. Recent legislative hearings also have considered conflicting legal positions of the state’s top lawyers concerning required Proposition 98 school funding levels under a future CalSTRS financing plan.

Based on our years of analysis of CalSTRS, we conclude that state laws are unclear on all of these points. That has been the big problem with CalSTRS all along. No law clearly assigns responsibility for CalSTRS’ unfunded liabilities. No law clearly tells the state how to fund a CalSTRS financing plan under Proposition 98. No law says how much of the future funding plan should be paid for by teachers, districts, or the non–education part of the state budget. No law provides CalSTRS with tools to ensure the system reaches and remains at 100 percent funding over the long term. Today’s legislators face the daunting task of developing—and funding—such a law.

Fully Funding CalSTRS in About 30 Years. Under the Governor’s May Revision proposal, contribution increases from the state, districts, and teachers would begin July 1, 2014, and ramp up in the coming years. Contributions by the state and teachers would ramp up over three fiscal years, and district contributions would increase over the next seven years. The plan aims to fully fund CalSTRS within about 30 years.

Districts Would Pay About 70 Percent of Added Costs. Figure 12 displays the proposed contribution rate increases under the Governor’s plan, including estimates from CalSTRS on the dollar amounts that would be generated by these contribution rate increases. (The figure reflects, for example, CalSTRS’ assumptions concerning future school district payroll increases.) Over the next seven fiscal years, school and community college district contribution rates would more than double from their current level, which is 8.25 percent of teacher payroll. The 10.85 percentage point contribution increase shown in Figure 12 would result in total district contributions of 19.1 percent of payroll. By 2020–21, when the plan is fully phased in, additional contributions by districts would total about $3.8 billion. Over the 32–year life of the funding plan, districts would pay an estimated 70 percent of the total added contributions under the proposal. The Governor proposes no adjustments to Proposition 98 specifically related to this additional funding responsibility. The higher contributions to CalSTRS would consume a noticeable portion of the additional funding districts expect to receive over the next few years.

Figure 12

CalSTRS Contributions Under Governor’s Plan

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

2019–20

|

2020–21

|

|

Districts

|

|

Current law rate

|

8.25%

|

8.25%

|

8.25%

|

8.25%

|

8.25%

|

8.25%

|

8.25%

|

|

Proposed increase

|

1.25

|

2.85

|

4.45

|

6.05

|

7.65

|

9.25

|

10.85

|

|

New Rate

|

9.50%

|

11.10%

|

12.70%

|

14.30%

|

15.90%

|

17.50%

|

19.10%

|

|

Projected Contribution

|

$347

|

$821

|

$1,329

|

$1,874

|

$2,458

|

$3,083

|

$3,751

|

|

State

|

|

Current law rate

|

3.29%

|

3.52%

|

3.52%

|

3.52%

|

3.52%

|

3.52%

|

3.52%

|

|

Proposed increase

|

0.16

|

1.37

|

2.81

|

2.81

|

2.81

|

2.81

|

2.81

|

|

New Rate

|

3.45%

|

4.89%

|

6.33%

|

6.33%

|

6.33%

|

6.33%

|

6.33%

|

|

Projected Contributiona

|

$59b

|

$384

|

$772

|

$812

|

$842

|

$874

|

$906

|

|

Teachers Hired Prior to January 1, 2013

|

|

Current law rate

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

|

Proposed increase

|

0.15

|

1.20

|

2.25

|

2.25

|

2.25

|

2.25

|

2.25

|

|

New Rate

|

8.15%

|

9.20%

|

10.25%

|

10.25%

|

10.25%

|

10.25%

|

10.25%

|

|

Projected Contribution

|

$39

|

$314

|

$592

|

$594

|

$595

|

$595

|

$594

|

|

Teachers Hired After January 1, 2013

|

|

Current law rate

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

8.00%

|

|

Proposed increase

|

0.08

|

0.56

|

1.21

|

1.21

|

1.21

|

1.21

|

1.21

|

|

New Rate

|

8.08%

|

8.56%

|

9.21%

|

9.21%

|

9.21%

|

9.21%

|

9.21%

|

|

Projected Contribution

|

$1

|

$15

|

$43

|

$55

|

$69

|

$83

|

$98

|

|

Grand Total, Projected Contributions

|

$446

|

$1,534

|

$2,736

|

$3,335

|

$3,964

|

$4,635

|

$5,349

|

State Would Pay Around 20 Percent of Added Costs. Under the Governor’s plan, additional state contributions to CalSTRS would be phased in over three years. By 2016–17, the state’s contributions to the defined benefit program of CalSTRS would grow by about 80 percent from what they otherwise would be—from 3.5 percent of payroll to 6.3 percent. (In addition, the state already makes annual payments to another program—which shields CalSTRS pension benefits from the effects of inflation—equal to about 2.5 percent of teacher payroll.) Like all of the state’s current direct contributions to CalSTRS, the additional payments would be funded from the non–education (“non–Proposition 98”) part of the state budget, thereby reducing the amount of funds otherwise available to fund other state priorities.

Teachers Would Pay About 10 Percent of Added Costs. Longstanding case law in California limits the ability of the state to change benefits or contribution rates for existing members of CalSTRS. Consistent with this law, the administration advances a proposal—already discussed in legislative hearings—to guarantee for the first time an existing benefit that adjusts teachers’ pensions by a simple 2 percent per year in retirement. In exchange for this new guarantee, the state would increase teachers’ required contributions to CalSTRS. Because pension benefits for teachers hired after January 1, 2013 were lowered by the Legislature below those of previously hired teachers, the amount by which the state would increase contributions of post–2013 hires is lower under the Governor’s plan. Specifically, the Governor’s plan increases contributions for teachers hired before 2013 by 28 percent—from 8 percent of payroll to 10.25 percent. For teachers hired after 2013, the increase would be 15 percent—from 8 percent of payroll to 9.21 percent.

Bold Proposal to Address Huge Problem. In 2012, the Legislature adopted a resolution declaring its intent to approve legislation to address CalSTRS’ long–term funding needs by the end of the 2014 legislative session. Both houses have held hearings over the last two years that developed some of the ideas now reflected in the Governor’s proposal. The Governor deserves considerable credit for this bold proposal that advances an important discussion. We recommend that the Legislature use the Governor’s plan as a starting point and adopt a comprehensive, long–term funding program for CalSTRS this year. As we have pointed out in legislative testimony, the costs to address this difficult problem only grow the longer the state waits.

Sharing These Unfunded Liability Costs Is Reasonable. Districts, teachers, and the state each benefited from the underfunding of teachers’ pension benefits over time. Districts benefited by offering a valuable compensation benefit at a lower cost. Teachers benefited from receiving that compensation at a lower cost, as there was more funding in district budgets for other purposes—including pay and benefit increases. Finally, by not providing additional funding for these teacher compensation costs, the state benefited by having more money to fund various priorities. Because all three groups benefited, we think it is reasonable for each group to share in the costs to address CalSTRS’ existing unfunded liabilities.

No One Right Way to Share These Costs. There is no magic formula for determining what portion of the unfunded liability should be paid by the state, districts, or teachers. Instead, allocating these costs is one of the key choices the Legislature and the Governor need to make. After the state’s leaders reach a basic agreement on how costs should be shared, the specific allocation of costs to teachers, districts, and the state’s non–education budget—and any desired Proposition 98 adjustments—can be adopted as statutory law.

Critical to Avoid Future Unfunded Liabilities. Pension liabilities are paid over an extraordinarily long time horizon. Moreover, in California public employees have strong contractual protections that often limit changes to pension benefit and contributions once they are hired and continuing throughout their lifetimes. For these reasons, if the Legislature wishes to change how CalSTRS is funded and administered 50 years in the future, decisions have to be made now. By taking such actions, the state can put CalSTRS on a course to be consistently and fully funded—reliably providing teachers with benefits they have earned.

We recommend that the Legislature adopt a CalSTRS funding plan that achieves this goal by:

- Aiming for Full Funding in About 30 Years. As the American Academy of Actuaries pointed out in a 2012 brief, there is a myth that pension finances are healthy if the systems are 80 percent funded. In fact, 80 percent funding means that 20 percent of previous benefit costs are shifted to future taxpayers—and in some cases, employees—with high interest costs accruing over time. Pension systems generally aim to reach and maintain 100 percent funding over the long term. The Governor correctly proposes this sound funding goal.

- Preserving Full Funding Once It Is Achieved. One of the key flaws with CalSTRS’ historical setup has been the inability of the system to adjust contribution rates based on changing actuarial conditions—investment returns, system demographics, and changing benefit structures. To avoid new unfunded liabilities in the future, CalSTRS would need to be given authority to adjust contribution rates for employers and/or future employees—similar to the authority of CalPERS and other pension systems.

- Ending the State’s Unusual Position in CalSTRS Over Time. The state is responsible for California’s public education system, but local districts are the employers of teachers and administrators covered by CalSTRS, and those local districts set most teacher compensation at the bargaining table—except for CalSTRS pensions. Districts pay their employees and most of their benefits, but the state makes an unusual direct contribution to fund part of the CalSTRS benefits. We believe the state should clarify funding responsibilities for newly hired teachers in the future. Specifically, we recommend that teachers and districts be responsible for all pension costs—including any future rate changes needed to keep the system fully funded over time. This would result in teachers being treated similarly to virtually all other local government employees, whose pension benefits are funded from employee and local government contributions. This would also ensure that the state—particularly after paying billions of dollars to help retire the existing unfunded liability of the system—was no longer on the hook for any future unfunded liabilities. This does not mean, however, that future teacher benefits would have to be changed. It merely means that the system would be funded entirely from teacher and district contributions and resulting investment earnings.

Two–Year Spending Increases by $1.4 Billion. The Governor’s May Revision includes increased General Fund spending for health and human services programs of almost $1.4 billion ($528 million in 2013–14 and $840 million in 2014–15) above the spending levels proposed in the January 10 budget plan. Of the $1.4 billion increase, about $400 million is for human services programs and almost $1 billion is for health programs. An increase in spending for the Medi–Cal Program of $919 million ($417 million in 2013–14 and $502 million in 2014–15) accounts for the bulk of the growth in health spending, with the remainder spread across other health programs. Most of the growth in human services spending is concentrated in two programs—California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) and In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS).

Spending Increases Are Largely Caseload–Driven, Reflecting Implementation of Federal Health Care Reform. As shown in Figure 13, most major changes in estimated and proposed health and human services spending are due to caseload increases. Two of the major caseload changes—the Governor’s updated caseload estimates for the so–called mandatory and optional Medi–Cal expansions—are related to the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as federal health care reform. Specifically, the Governor’s caseload estimate for the mandatory Medi–Cal expansion in 2014–15 increased from 509,000 beneficiaries to 815,000 beneficiaries between the January 10 budget and the May Revision—an increase of about 60 percent. As shown, the net cost of the estimated increase in Medi–Cal enrollment over 2013–14 and 2014–15 is $410 million. While Figure 13 shows major ACA–related caseload changes, we note that there are many other smaller ACA–related impacts in Medi–Cal and other programs. For example, the Governor proposes a $20 million General Fund increase in the CalFresh program that is ACA–related. (The Governor’s May Revision estimates that more households eligible for CalFresh will enroll in the program as a result of outreach efforts conducted as part of ACA implementation.)

Figure 13

Major Changes in Estimated Health and Human Services (HHS) Spendinga

General Fund (In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

Combined

Two–Year

Difference

|

|

Medi–Cal Caseload Increases

|

|

|

|

|

Mandatory Medi–Cal expansion caseload increaseb

|

$92.9

|

$513.2

|

$606.1

|

|

Optional Medi–Cal expansion caseload increasec

|

–7.2

|

–189.3

|

–196.5

|

|

Subtotals

|

($85.7)

|

($323.9)

|

($409.6)

|

|

Other HHS Program Caseload Increases

|

|

|

|

|

CalWORKs caseload increase

|

$35.0

|

$95.0

|

$130.0

|

|

In–Home Supportive Services caseload–related cost increases

|

102.3

|

137.8

|

240.1

|

|

Subtotals

|

($137.3)

|

($232.8)

|

($370.1)

|

|

Lower Savings Related to Changes to 1991 Health Realignmentd

|

—

|

$175.1

|

$175.1

|

|

Various Other Changes (Net)

|

$305.0

|

$108.0

|

$413.0

|

|

Net Increased Costs

|

$528.0

|

$839.8

|

$1,367.8

|

Fiscal Uncertainty of ACA Implementation. Given the significant uncertainty surrounding the fiscal effects of ACA implementation when the Governor prepared the January 10 budget plan—some major ACA provisions affecting Medi–Cal and other state and local government programs went into effect on January 1, 2014—it is not surprising that the May Revision makes significant adjustments that reflect the first few months of available data. However, ACA implementation is still in its initial phases, and estimates of its impact on state programs are still subject to significant uncertainty and in many cases are based upon limited data and key assumptions. We will review the Governor’s estimates of ACA–related caseload adjustments and report to the Legislature at budget hearings on our findings.

IHSS Spending Increases. The administration now estimates that IHSS General Fund program costs in 2013–14 and 2014–15 will be a combined total of $240 million above the Governor’s proposed budget in January. The administration estimates that this increase is mostly due to expected caseload growth, higher costs per hour, and increased hours per consumer. We are evaluating the administration’s caseload, cost, and utilization assumptions, and will report at budget hearings on our findings.

CalWORKs Spending Increases. The administration has revised upward its caseload estimates for the CalWORKs program in light of recent actual data that show the caseload declining at a slower rate than was previously expected. Higher caseloads are estimated to increase CalWORKs costs in 2013–14 and 2014–15 by a combined total of $130 million. Additionally, the administration has also revised downward its estimate of county health program savings expected to result from ACA implementation, as many low–income uninsured individuals who would previously have been served by county indigent care programs are transitioned into Medi–Cal. Chapter 24, Statutes of 2013 (AB 85, Assembly Committee on Budget), revised the 1991 health realignment to redirect these county savings to pay for an increased share of CalWORKs grant costs, directly offsetting General Fund expenditures. Expected savings in 2014–15 have been reduced from $900 million (as estimated in the Governor’s January budget) to $725 million, resulting in additional General Fund costs in CalWORKs of $175 million.

Governor’s Proposals. In February 2014, the Legislature passed legislation providing $687 million in 2013–14 for various activities related to responding to the current drought in California. The Governor’s May Revision proposes an additional $142 million ($116 million from the General Fund) in 2014–15 to continue and expand upon those activities in the budget year. As shown in Figure 14, this funding would support a range of activities in seven departments. Almost half of the funding ($66 million) would be available to the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection to expand fire suppression and prevention activities, including funding for additional firefighters for what is expected to be an extended fire season. The total also includes $39 million for the Department of Fish and Wildlife to monitor impacts of the drought on fish populations, as well as to improve fish and wildlife habitat throughout the state. In addition, it includes $18 million for the Department of Water Resources (DWR) for various emergency water supply activities, such as coordinating the state’s response to the drought, monitoring water conditions, and increasing the availability of water to communities. (In addition to the total cited above, the May Revision proposes to redirect $28 million in previously appropriated bond funds to install temporary barriers to prevent salt water from intruding into the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. It also includes provisional language that would allow the Director of Finance to augment DWR’s General Fund budget by up to $19.3 million to operate, maintain, and remove those barriers.)

Figure 14

May Revision Proposes Additional Drought Funding for Seven Departments

2014–15 (In Millions)

|

Department

|

Purpose

|

General Fund

|

Other Funds

|

Totals

|

|

Forestry and Fire Protectiona

|

Increased fire suppression and prevention

|

$53.8

|

$12.2

|

$66.0

|

|

Fish and Wildlife

|

Monitoring and habitat improvements

|

30.3

|

8.5

|

38.8

|

|

Water Resources

|

Emergency water supply activities

|

18.1

|

—

|

18.1

|

|

Social Services

|

Food assistance to drought–affected areas

|

5.0

|

—

|

5.0

|

|

Office of Emergency Services

|

Drought response coordination and guidance

|

4.4

|

—

|

4.4

|

|

State Water Resources Control Board

|

Enforcement of limits on water diversions

|

4.3

|

—

|

4.3

|

|

General Services

|

Water conservation in state facilities

|

—

|

5.4

|

5.4

|

|

Totals

|

|

$115.9

|

$26.1

|

$142.0

|

Considerations When Reviewing Drought Proposals. In reviewing the administration’s drought–related proposals, the Legislature may wish to consider several questions. These include (1) the degree to which the proposals address the most critical problems associated with the current drought; (2) whether the proposed activities are cost–effective means of addressing those problems; and (3) whether there are alternative funding sources that could be used to support the activities, such as charges on beneficiaries or polluters. We will provide additional comments on these proposals in the course of budget hearings.

Modest Statewide Economic Effects From Drought. We note that we are often asked about the potential effect of the drought on California’s economy and tax revenues. There is no doubt that the drought presents substantial economic burdens for some local communities, particularly those dependent on agriculture and those experiencing severe water supply issues. To address these concerns, the previous drought legislation and the May Revision include a total of $53 million for food, employment, and rental housing assistance for communities most affected by the drought. On a statewide basis, however, the net effects of the drought on economic activity likely will be very modest in the near term. Should the drought persist or intensify, its effects could increase somewhat, including the effects of longer–term changes in agriculture and other parts of the economy. Our office will continue to monitor the economic effects of the drought.

The improvement in the state’s fiscal condition—driven largely by continued economic growth and rapid increases in financial and housing markets—has resulted in large increases in the revenue available to the state in recent years. This year, under current law, a significant portion of these new revenues is required to be spent on schools. In addition, health and human services expenditures are increasing in 2014–15, particularly higher Medi–Cal costs related to ACA implementation. Even after accounting for such baseline spending increases, there remain several billion dollars to be allocated. The Governor’s key choices for what to do with these funds are to: