The property tax is a major source of revenue for local governments, raising more than $50 billion annually for counties, cities, special districts, and schools and community colleges. Counties administer the property tax. While most local governments that receive property taxes reimburse the county for their proportionate share of administrative costs, schools and community colleges (“schools”) are not required to pay these costs. Instead, counties pay the schools’ share of costs as well as their own. Statewide, counties pay about two–thirds of the cost to administer the tax while receiving less than one–third of the revenues they collect. As a result of this imbalance, there have been long–standing concerns that counties might not fund property tax administration appropriately. If property tax administration were not funded appropriately, this could have a fiscal effect on the state because local property taxes that go to schools generally offset required state spending on education.

The 2014–15 Governor’s Budget proposes a modest pilot program to study potential improvements to the current property tax administration system. We recommend that the Legislature approve a pilot program but make several modifications to (1) ensure each county has the same fiscal incentive to participate, (2) provide participating counties greater funding certainty, (3) promote representative and consistently measured results, and (4) potentially increase near–term state savings on school spending.

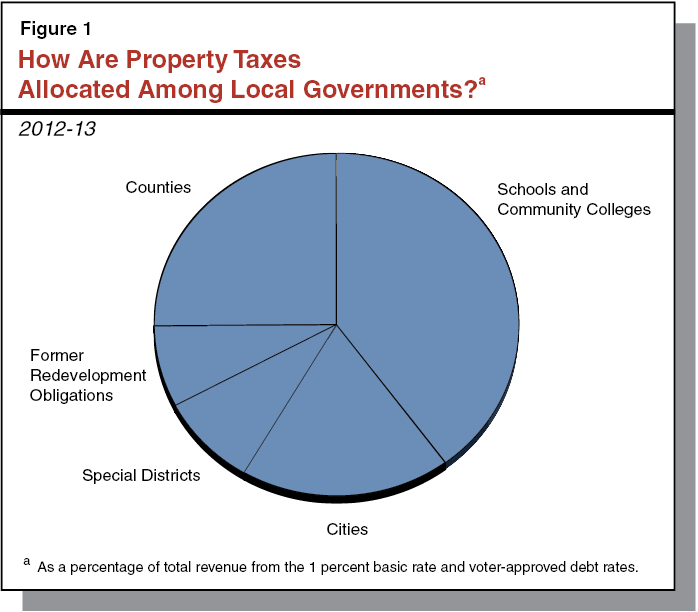

The property tax is California’s second largest source of revenue, raising more than $50 billion annually for local governments—including cities, counties, special districts, and school and community college districts. Figure 1 shows how property tax revenues were distributed statewide to these governments in 2012–13. In future years, the share of the property tax allocated to schools and community colleges (schools) will increase to more than 50 percent due to the end of a temporary adjustment known as the “triple flip” and the dissolution of redevelopment.

Property Tax Allocation Varies Across the State. The distribution of property taxes shown in Figure 1 reflects statewide averages. As we discuss in our report, Understanding California’s Property Taxes (November 2012), the share of countywide property taxes allocated to specific counties, schools, and other local governments varies across the state. Among other factors, this variation reflects taxation decisions of the mid–1970s. In some counties, the distribution of property tax revenues differs considerably from the distribution shown in Figure 1. For example, Orange, San Mateo, and Santa Clara Counties get a smaller share of the countywide property tax than the share shown in Figure 1 and schools in these counties receive above–average shares. Los Angeles and San Francisco Counties, in contrast, get a larger share of the countywide property tax and their schools receive smaller shares.

County Role in Property Tax Administration. Counties administer the property tax. County assessors determine the taxable value of property, county tax collectors bill property owners, and county auditors distribute the revenue among local governments. Statewide, county spending for assessors’ offices exceeds $500 million each year. County costs for property tax collectors and auditors are unknown but much smaller.

Paying for Property Tax Administration. For most of the state’s history, counties paid all property tax administration costs using county resources. After passage of Proposition 13 in 1978 and some changes to state–county program responsibilities, however, counties argued that they did not have sufficient revenues to continue paying all these costs. In 1990, the state authorized counties to split these costs among all governments receiving property tax revenues, including schools (Chapter 466, Statutes of 1990 [SB 2557, Maddy]). One year later, in response to concerns from schools, the state prohibited counties from charging schools, in effect requiring counties to cover the schools’ share of these costs (Chapter 75, Statutes of 1991 [SB 75, Maddy], and Chapter 282, Statutes of 1991 [SB 282, L. Greene]).

Current Cost Allocation System Raises Concerns. Making counties responsible for covering the schools’ share of property tax administrative costs, in turn, has prompted concerns that counties might not fund these activities appropriately. This is because counties pay a large share of property tax administrative costs (often more than two–thirds) yet receive a small share of property tax revenues (often less than one–third). If tax administration is not funded appropriately, counties could collect less property taxes for all local governments than they otherwise would. This would also affect the state because most property tax revenue allocated to schools offsets required state spending on education.

Prior State Actions to Support County Property Tax Administration. Recognizing the state’s fiscal interest in school property tax revenues, the Legislature has created programs to support county property tax administration on several occasions. These efforts, summarized later in this brief, were temporary in nature, modest in scope, and oriented toward giving all counties some financial resources. The program evaluations did not provide useful information and tended to overstate additional property tax collections.

Property Tax Administration—County Perspective

Counties Pay Disproportionate Share of Property Tax Administration Costs. As discussed above, the average county pays more than two–thirds of the costs to administer the property tax, yet receives less than one–third of revenue collected. Cities and special districts typically pay the remaining one–third of property tax administration costs and receive about one–third of the revenue. Schools, in contrast, usually receive over 40 percent of the property tax but do not pay any property tax administration costs. In effect, counties pay their share and the schools’ share.

County Assessors Must Justify Their Spending. County assessors have a statutory obligation to administer the property tax fairly and effectively. As part of county government, however, funding for county assessors’ offices depends on annual budget decisions by county boards of supervisors. Given the many competing uses for county resources, it is reasonable to assume that supervisors are more likely to approve assessor office spending proposals that generate enough county benefits to offset the county’s costs. We note that the state uses a similar analytical approach as part of its review of budget proposals from the Franchise Tax Board, the agency that administers the state’s personal income and corporation taxes.

Cost Allocation System Weakens Incentive to Fund Property Tax Administration Appropriately. Under the current cost allocation system, counties pay their share and the school’s share of property tax administration costs. A portion of the benefits from county spending on administration (increased property taxes) nevertheless go to schools, and do not benefit the county. Given this fiscal incentive, when considering proposals for funding the assessor’s office, county supervisors might decide not to approve spending that benefits all local governments financially but imposes a net negative fiscal impact on the county itself.

Incentive to Fund Property Tax Administration Is Weaker in Some Counties Than Others. The fiscal effect of this cost allocation system varies considerably among counties, depending on the share of property taxes allocated to the county, schools, and other local governments. Figure 2 shows the county benefits and costs for three hypothetical counties considering a proposal to increase funding for property tax administration. In the case of the County A (low county share), the county would receive 10 percent of any increased property tax revenues, but would pay 70 percent of the proposal’s costs. Counties B and C would receive 25 percent or 50 percent of the revenues while paying 75 percent or 80 percent of the costs. In many cases, therefore, a proposal to increase funding for property tax administration would need to show that it could generate considerable returns in order for the county to “break even.” In the case of County A, for example, the county would need to generate returns of seven–to–one in order to break even. Thus, we characterize County A’s incentive to fund property tax administration as “very low.” County B supervisors, in contrast, would have to determine that the assessor would generate roughly $3 for each additional dollar spent on property tax administration, and County C supervisors would require about $2. Under a proportionate funding system, in contrast, each county’s share of costs would be the same as its share of benefits. In these cases, boards of supervisors would have a greater financial incentive to provide resources to assessors’ offices.

Figure 2

Counties May Face Weak Incentive to Fund Property Tax Administration

|

Share of Property Taxes

|

County A

|

|

County B

|

|

County C

|

|

Low

County Share

|

Average

County Share

|

High

County Share

|

|

County

|

10%

|

|

25%

|

|

50%

|

|

Schools

|

60

|

|

50

|

|

30

|

|

Cities and special districts

|

30

|

|

25

|

|

20

|

|

Totals

|

100%

|

|

100%

|

|

100%

|

|

County share

of costs

|

70%

|

|

75%

|

|

80%

|

|

County share

of benefits

|

10

|

|

25

|

|

50

|

|

Amount county needs to “break even”

|

Seven–to–one

|

|

Three–to–one

|

|

About two–to–one

|

|

County incentive to fund property tax administration

|

Very low

|

|

Low

|

|

Moderate

|

Property Tax Administration—State Perspective

Though considered a local tax, the property tax has a major impact on the state’s budget. Under the state’s education finance system, the amount of school funding each year is set according to Proposition 98 and paid for with a combination of local property tax revenue and state General Fund revenue. Increases in property tax revenues generally allow for decreases in state General Fund spending on education. The state therefore benefits from additional local property taxes. In 2012–13, local property taxes offset about $16 billion in required state spending on education. (In certain instances, under Proposition 98’s so–called “Test 1” calculation, school property tax revenue increases the overall level of school funding and does not offset the required state contribution.)

The state also has a policy interest in a fairly administered system with accurate determinations of value, complete property tax rolls, accessible records, and full compliance with the laws governing property tax administration. Such a system likely would function more efficiently, be viewed more favorably by taxpayers, and would help ensure that property owners in different counties are treated similarly.

Past Efforts to Improve System Were Modest and Temporary. Recognizing the disproportionate share of administrative costs borne by counties, the state has provided grants and loans for these costs on several occasions over the past 20 years. First, the 1994–95 budget package included $25 million in grants to counties for property tax administration. This grant program helped reduce county assessor backlogs that resulted from the early 1990s recession. Over the following three years, the administration loaned $60 million annually to counties for property tax administration. The administration forgave these loans if additional property taxes for schools exceeded the county’s loan amount. (Ultimately, all loans were forgiven.) Later, between 2002 and 2005, the state operated a similar loan program funded at $60 million annually. The Legislature ended this program as part of the 2005–06 budget agreement.

Past efforts to improve property tax administration produced some positive results. The programs provided additional resources to process reassessments and to meet audit requirements. They also generally resulted in additional property tax revenue. Evaluation of the programs, however, likely overstated the amount of additional revenues they generated and did not provide data sufficient to evaluate the programs’ overall effectiveness.

The 2014–15 Governor’s Budget proposes a modest grant program to study ways to improve property tax administration. The administration proposes appropriating $7.5 million from the General Fund to begin a three–year pilot program, called the State–County Assessors’ Partnership Agreement Program. The administration expects the program to generate additional property taxes for schools and other local governments.

Additional Staff to Accelerate, Increase, and Preserve Property Tax Revenues. Under this proposal, the Department of Finance would provide state funds for nine counties—two urban, four suburban, and three rural counties, all to be selected later—to hire additional county assessor’s office staff. Participating counties would match the state grant on a dollar–for–dollar basis. New staff hired with these funds would be directed to accelerate, increase, and preserve county property tax revenue. Accelerated revenue occurs when property tax collections happen sooner than they otherwise would. Increased revenue occurs when staff update the taxable value of properties that received tax reductions during the real estate crisis. (These properties are known as Proposition 8 [1978] decline–in–value properties.) Preserved revenue occurs when staff successfully defend the initial taxable value of a property when a property owner appeals that value. Otherwise, an appeal would result in a smaller tax bill and therefore reduced property taxes. Staff hired with grant funds could undertake the following activities:

- Assess new construction.

- Assess property that changed ownership.

- Assess property additions or modifications.

- Assess property that was not taxed in prior years.

- Reassess properties that received tax reductions in recent years.

- Respond to and defend property tax appeals.

Counties Must Report Results. Each year, participating counties would have to report to the administration the number and taxable value of properties added to the local property tax roll as a result of activities undertaken with grant funds. In addition to new or updated assessments, each county would report the total amount of property taxes “preserved” when staff successfully defended a property owner’s appeal to reduce their property’s taxable value.

Measuring Success. Each year, the administration would determine whether each county’s pilot was successful. The administration defines success as a county pilot resulting in additional property tax revenues being allocated to schools that are at least three times larger than the amount of the state grant in that county. (Additional revenue from the program includes revenue accelerated, increased, or preserved by staff hired using state grants and county matching funds.) The administration’s calculation would not vary by county based on the schools’ share of countywide property taxes in that county. The Director of Finance would have authority to terminate the grant program in any county that does not meet this level of return.

Findings From Pilot Program to Inform Future Decisions. The administration’s grant program is a three–year pilot program, after which the administration would use its findings to make a “recommendation as to whether the Program should be continued in its current form, expanded to include additional county assessors’ offices, or terminated in 2017–18.”

The Governor’s proposal recognizes the state’s interest in property tax administration. The current system does not give counties appropriate incentives regarding property tax administration funding, potentially resulting in delayed and lower revenue for local governments (including schools). The administration’s proposal is one approach the state could pursue to improve county incentives to fund property tax administration and merits serious consideration. In our view, however, the administration’s pilot program has several shortcomings. We discuss these below after first outlining the characteristics of an effective pilot program.

What Makes an Effective Pilot Program?

Governments, nonprofit organizations, and private businesses frequently use pilot programs to test new projects on a small scale before implementing larger, more costly, versions. An effective pilot program evaluates a project’s outcomes—its costs, benefits, and effectiveness—for a small but representative portion of the potential project. In particular, an effective pilot proposal is:

- Representative. Participants selected for a pilot project should be similar to the additional participants that would be included in the full–scale project. This way, the pilot’s results are more likely to be replicated. If the pilot’s participants are systematically different from other participants, full–scale results may differ significantly from those of the pilot. This is because, as the program expands to new participants, these participants might perform differently. Therefore, having representative participants makes pilot programs more helpful for policy makers.

- Measured Accurately and Consistently. In order for the state to make informed decisions about whether to expand a pilot program, the program’s results must be measured accurately and consistently for all participants. This way, the state can appropriately consider the costs and benefits of full–scale implementation. If outcomes are measured inaccurately or inconsistently across participants, it may be impossible to notice important trends or identify areas where the program might benefit from modifications prior to full implementation.

Is the Administration’s Proposal an Effective Pilot Program?

Requiring Dollar–for–Dollar County Match Will Influence Which Counties Apply. To receive state grants under the pilot program, counties must agree to match the amount of state funds they receive. The administration’s proposed matching requirement likely would influence the types of counties that apply. Figure 3 illustrates this fiscal effect for the three hypothetical counties (discussed earlier in Figure 2), under the assumption that each dollar of grant funding for property tax administration generates three dollars of additional revenue. Specifically, County A (low county share) pays $50,000, yet receives only $30,000 of the resulting revenues. County C (high county share), in contrast, pays $50,000, and receives $150,000 in additional property taxes. Overall, the ratio of benefits to costs for high–share counties would tend to be greater than for low–share counties because high–share counties would receive a larger portion of additional property taxes generated under the pilot, yet they would be required to match the same amount to participate. Given these fiscal incentives, some counties, particularly lower–share counties, may not participate in the pilot because the expected benefits (in this case, the amount of increased revenue) of doing so would be outweighed by the required dollar–for–dollar matching amount. Because of this influence, counties that participate in the pilot may not be representative of counties that do not participate.

Figure 3

Benefits Vary Under Administration’s Proposal

|

|

County A

|

County B

|

County C

|

|

Share of Property Taxes

|

Low

County Share

|

Average

County Share

|

High

County Share

|

|

County

|

10%

|

25%

|

50%

|

|

Schools

|

60

|

50

|

30

|

|

Cities and special districts

|

30

|

25

|

20

|

|

Totals

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

Under Administration’s Proposal

|

|

Total Grant Amount

|

$100,000

|

$100,000

|

$100,000

|

|

State portion

|

50,000

|

50,000

|

50,000

|

|

County portion

|

50,000

|

50,000

|

50,000

|

|

Revenue Generateda

|

$300,000

|

$300,000

|

$300,000

|

|

Schools/state portion

|

180,000

|

150,000

|

90,000

|

|

County portion

|

30,000

|

75,000

|

150,000

|

|

State Perspective

|

|

|

|

|

Net impact

|

$130,000

|

$100,000

|

$40,000

|

|

Ratio of benefits to costs

|

3.6

|

3.0

|

1.8

|

|

County Perspective

|

|

|

|

|

Net impact

|

–$20,000

|

$25,000

|

$100,000

|

|

Ratio of benefits to costs

|

0.6

|

1.5

|

3.0

|

State Benefit Smallest in Counties Most Likely to Apply. Counties that receive a relatively large share of countywide property taxes (such as County C) are most likely to benefit from, and therefore apply to, the proposed pilot program. The share of property taxes allocated to schools in these counties tends to be smaller than in other counties. Conversely, as shown in Figure 3, a relatively small share of each additional tax dollar generated by the pilot program in County C would provide state benefit by reducing required state spending on education. In general, the state would tend to benefit least from the pilot program in counties where the county government has the most to gain from participating in the pilot. Consequently, the state would tend to benefit most in cases where the counties have little or no incentive to participate.

Achieving “Success” Easier for Some Counties Than Others. According to the administration, its pilot program would be successful if accelerated, increased, and preserved revenue allocated to schools as a result of the grant program are at least three times greater than the state’s grant amount in each county. (This measure would be calculated annually for each participating county, and the administration could discontinue funding for counties that do not achieve this three–to–one return.) As shown in the section of Figure 3 labeled “State Perspective,” additional property taxes for schools depend on (1) the amount of additional property taxes resulting from the pilot, and (2) the share of these revenues allocated to schools. In order to meet the administration’s target, a county with a lower allocation to schools, such as County C, would need to generate a greater overall return than other counties. Alternatively, a county with a large school share, such as County A, could meet its target with a lower overall return on pilot funds. Given this variability among counties, it is unclear whether the administration’s three–to–one target is the best measurement of the program’s effectiveness.

Increased and Preserved Revenue Difficult to Quantify. Federal, state, and local governments regularly invest in tax administration improvements in order to reduce the amount of owed taxes that go uncollected each year. The impact of these efforts is often difficult to calculate. This is because it is not possible to know how much revenue would be collected in the absence of increased spending on tax administration. For example, though we can calculate how much additional revenue each additional employee collected, we do not know how much of that same revenue would have been collected otherwise. As a result, the amount of increased or preserved revenue reported by counties under this pilot program could somewhat overstate the impact of the pilot funds.

Accelerated Revenue Treated the Same as Increased Revenue. In reporting its outcomes to the administration, each participating county is required to estimate the amount of additional property taxes collected as a result of activities undertaken with its pilot grant. Many of these activities focus on accelerating revenues, meaning they would result in collecting revenue earlier than it otherwise would be (without pilot funds). Although local governments and the state receive some benefit from accelerated property tax revenues, they derive more lasting fiscal benefits from increased revenue. It will be important for counties to distinguish carefully between accelerated and increased revenue.

Each County Category Would Receive Same Grant Amount. The administration recognizes that counties vary in terms of the number and value of properties in their jurisdiction, their so–called “assessed valuation.” Mindful of this, grants of different sizes would be made under the proposed pilot: $1,875,000 to urban counties, $825,000 to suburban counties, and $150,000 to rural counties. However, variation within each category remains problematic. For example, Monterey County and Modoc County would be eligible as rural counties and receive the same grant amounts, yet Monterey County’s assessed valuation is 50 times larger than Modoc County’s. Thus, the grant would increase Modoc County’s property tax administration budget by 36 percent, while Monterey County’s property tax administration budget would increase by only 3 percent.

Such large differences in relative grant amounts might affect county efforts to improve property tax administration. For example, a large grant might be difficult to implement quickly and cost–effectively. Alternatively, some counties might not require such a large grant to make a significant new investment in their property tax systems. On the other hand, grants that are small may be insufficient to hire qualified staff. Ultimately, these differences might unnecessarily influence pilot outcomes.

Administration’s Selection Process Unclear. Under the administration’s proposal, all counties could apply for pilot funds and nine counties would be selected—two urban, four suburban, and three rural counties. In the event that more than nine counties apply, it is unclear what process or criteria the administration would use to ultimately select participating counties.

We recommend the Legislature approve the administration’s pilot proposal but modify the proposal in the following four ways.

Modify County Matching Amount to Ensure Representative Participation. As discussed earlier, the administration’s dollar–for–dollar county match would likely influence the types of counties that apply, with counties that receive a large share of countywide property taxes more likely to apply than lower–share counties. In addition to influencing the types of counties that participate, it is likely that the greatest state benefit from investing in property tax administration is with counties least likely to apply under the administration’s proposal.

As an alternative, we recommend modifying each county’s matching amount to reflect its proportionate share of benefits received from additional spending on property tax administration. In other words, under our suggested approach, each county would pay its share of the total increase in funding from the pilot. As illustrated in Figure 4, each county would face the same fiscal incentive to participate in the pilot. For example, if the total grant under the pilot was $100,000 and County A’s share of countywide property taxes was 10 percent, the county would be required to contribute 10 percent of the grant cost, or $10,000, under our approach. This would help ensure that a representative group of counties participated. This would occur because each county would face the same potential benefits and costs of participating in the pilot. Counties with higher (lower) shares of their countywide property taxes would be required to pay a higher (lower) matching amount, but in turn receive a larger (smaller) share of additional property taxes generated by the pilot. Therefore, each county would face the same ratio of benefits to costs when choosing whether to participate in the pilot.

Figure 4

Benefits Same for Each County Under LAO Recommendation

|

|

County A

|

County B

|

County C

|

|

Share of Property Taxes

|

Low

County Share

|

Average

County Share

|

High

County Share

|

|

County

|

10%

|

25%

|

50%

|

|

Schools

|

60

|

50

|

30

|

|

Cities and special districts

|

30

|

25

|

20

|

|

Totals

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

Under LAO Recommendation

|

|

Total Grant Amount

|

$100,000

|

$100,000

|

$100,000

|

|

State portion

|

90,000

|

75,000

|

50,000

|

|

County portion

|

10,000

|

25,000

|

50,000

|

|

Revenue Generateda

|

$300,000

|

$300,000

|

$300,000

|

|

Schools/state portion

|

180,000

|

150,000

|

90,000

|

|

County portion

|

30,000

|

75,000

|

150,000

|

|

State Perspective

|

|

|

|

|

Net impact

|

$90,000

|

$75,000

|

$40,000

|

|

Ratio of benefits to costs

|

2.0

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

|

County Perspective

|

|

|

|

|

Net impact

|

$20,000

|

$50,000

|

$100,000

|

|

Ratio of benefits to costs

|

3.0

|

3.0

|

3.0

|

Assuming the state still committed $7.5 million a year to the pilot, modifying the county matching amount under our approach would reduce the overall amount of additional state–county funding for property tax administration under this program. This would occur because instead of matching state funds dollar for dollar, making available a total of $15 million in state–county funds annually, counties would match the share of grant funds equal to their share of countywide property taxes. In most cases, this is a smaller amount than the current match because counties typically receive less than 50 percent of property taxes. As a result, overall state–county funding would be somewhat smaller—likely $10 million to $12 million—than under the administration’s proposal. Paradoxically, however, this modification might actually increase near–term state General Fund savings. This is because our modified matching grant would not discourage counties that receive lower shares of countywide property taxes from applying. This modification would help maximize state savings because these counties (1) face the weakest incentive to fund property tax administration appropriately and (2) tend to be counties in which schools receive a large share of countywide property taxes.

Provide State Grant for Three Years. Under the proposal, the administration could end a county’s participation if that county’s grant program did not meet the three–to–one target. If the administration rejected these “low–performing” counties, the pilot’s results would not account for their performance and thereby overstate the program’s effectiveness. For the pilot program to represent all counties (and thus be an accurate statewide barometer), it must not systematically exclude low–performing counties. In the near term, of course, this would reduce return on the state’s grant funds. In our view, however, the importance of a representative pilot outweighs maximizing the state’s near–term savings. Thus, we recommend removing the three–to–one revenue target, in effect guaranteeing grant funds to each participating county for all three years of the pilot. (This would also provide county assessors greater funding certainty.)

Allocate State Grant in Proportion to Total Property Value. State grants under the administration’s proposal would be allocated to three categories of counties—urban, suburban, and rural. Each county within a category would receive the same amount, despite the wide variation within categories described earlier. Some counties would therefore receive larger grants, relative to their size, than other counties. To address this imbalance, we recommend allocating grants in proportion to each county’s total property assessed valuation. Mindful that pilot funds are limited, it may be necessary to cap the grant amount for larger counties, in order to preserve adequate funds for all nine counties. Similarly, it may be necessary to provide a minimum amount for rural counties to ensure that they could hire at least one half–time position.

Select Counties Randomly When Possible. If more than nine counties apply to participate in the pilot program, the administration indicates that it would select the final participants based on a review of each county’s application. It is unclear what criteria the administration would use to review county applications. Some criteria—for instance, selecting counties in which a large share of countywide property taxes go to schools—would influence the types of counties participating in the pilot. This could result in the pilot’s outcomes being systematically biased. We therefore recommend, where possible, that the administration be required to select counties randomly (provided that each county meets basic expectations, such as agreeing to collect results from the pilot program).

The Legislature and administration have had long–standing concerns about county incentives for funding property tax administration. Over the years, a wide variety of approaches to address this issue have been proposed. Before making any long–term decisions on this matter, the Legislature would benefit from a better understanding of (1) how counties would spend additional resources for property tax administration (for example, hiring staff or consultants, increasing salaries, or purchasing information technology) and (2) the extent to which school property taxes would increase in the short term (from accelerated revenues) and long term (from increased revenues). The state knows very little about these details. A better understanding of these dynamics not only would help the state choose what approach it should take, but also would help policy makers tailor that approach to best meet the state’s priorities. In our view, an effective pilot program is an important first step and therefore merits serious consideration.

Going forward, the Legislature has an array of alternatives for addressing concerns about county incentives to fund property tax administration. Results from a pilot program could help inform policy makers as they weigh these alternative approaches, which include:

- Allowing counties to deduct each school’s proportionate share of property tax administration costs from the school’s share of property tax revenues.

- Allowing counties to deduct each school’s proportionate share of future increases in county funding for property tax administration from the school’s share of property tax revenues. Under this approach, which our office proposed in Improving the Incentives for Property Tax Administration (1997), increases in property tax administration costs would be paid for by all of the local governments that benefit from property taxes.

- Targeting state funds to those counties where schools would benefit most from additional resources for property tax administration.