Court–ordered debt collected from defendants convicted of traffic violations or criminal offenses provides revenue to a number of state and local funds, which in turn support a variety of programs including trial court operations and victim assistance. As a result, the state has an interest in ensuring that such debt is collected in a cost–effective manner that maximizes the amount of revenue available to support these programs. Over the past decade, the Legislature, the judicial branch, counties, and other stakeholders have made a number of different changes intended to improve the court–ordered debt collection process. For example, a cost–recovery program for collecting delinquent debt (debt not paid on time) was put in place by the Legislature. In addition, the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) launched a court–ordered debt collection program. While many of these actions have helped increase the amount of debt collected, additional improvements can be made to further improve the collection of court–ordered debt.

In this report, we (1) provide background information on court–ordered debt, including how it is collected and who benefits from the proceeds, (2) assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the current court–ordered debt collection process, and (3) make a series of recommendations to improve the court–ordered debt collection process which could potentially lead to increased collections of such debt. In preparing this report, we spoke with a number of court administrators and judges from trial courts throughout the state in order to gain an in–depth understanding of the various complexities of the court–ordered debt collection process. We also spoke with county staff, state agency staff, and other stakeholders involved in the collections process. For example, we met with staff of the Judicial Council and analyzed collections data they provided to us.

What Is Court–Ordered Debt?

During court proceedings, trial courts typically levy a monetary punishment upon individuals convicted of traffic violations or criminal offenses. All fines, fees, forfeitures, penalty surcharges, assessments, and restitution assessed in the disposition of traffic and criminal cases are known as court–ordered debt—meaning the total amount of money that an individual owes the court. State law sets a base fine for each traffic or criminal offense and requires the court to add certain charges (such as a state penalty assessment) to the base fine. As shown in Figure, these additional fees and assessments can greatly increase the total obligation owed upon conviction of a traffic violation or criminal offense. The amount of this increase can vary widely depending on the specific offense committed and other factors.

Court ordered–debt is classified as nondelinquent or delinquent. Nondelinquent court–ordered debt consists of a monetary punishment assessed by the court that has not become overdue. Individuals make timely payments of nondelinquent debt by paying in full by a specified date or through installment payments as set by the court. Delinquent court–ordered debt consists of any debt that has not been paid on time, including any missed installment payments.

Figure 1

Various Fines and Fees Substantially Add to Base Fines

As of March 1, 2014

|

|

Failure to Stop at Stop Signa(Infraction)

|

Driving Under Influence of Alcohol/Drugsa(Misdemeanor)

|

|

Base fine

|

$35

|

$390

|

|

State surcharge

|

7

|

78

|

|

State penalty assessment

|

40

|

390

|

|

County penalty assessment

|

28

|

273

|

|

Court construction penalty assessment

|

20

|

195

|

|

DNA Identification Fund penalty assessment

|

20

|

195

|

|

EMS penalty assessment

|

8

|

78

|

|

EMAT penalty assessment

|

4

|

4

|

|

Court operations fee

|

40

|

40

|

|

Conviction assessment fee

|

35

|

30

|

|

Night court fee

|

1

|

1

|

|

Totals

|

$238

|

$1,674

|

Who Collects Court–Ordered Debt?

Counties Statutorily Responsible for Collections. Prior to 1997, each county bore responsibility for funding and operating the trial court in its jurisdiction. This included the responsibility for collection of court–ordered debt. Some counties operated the collection program by themselves, while other counties either operated the collection program in partnership with their courts or delegated all administrative control of the collection program to their courts.

In 1997, the state shifted primary responsibility for the funding of trial court operations from the counties to the state. State law defined the specific programs and services considered part of trial court operations and made them a state responsibility. State law also listed specific programs and services excluded from this shift—one of which was collections. Accordingly, counties continue to be statutorily responsible for the collection of court–ordered debt. However, unless both parties subsequently agree to changes, state law also required courts and counties to maintain the structure of the collection program that was in place in 1996. This preserved any previously–agreed–upon divisions of responsibility between courts and counties.

Actual Division of Responsibilities Varies Across Counties. As a consequence of these laws that preserved preexisting court–ordered debt collection arrangements, the structure of collection programs varies across the state. In some programs, the court or county individually collects all court–ordered debt in their jurisdiction. Other programs delegate collection activities among multiple entities in various ways. For example, in some cases, the court is responsible for collecting all debt related to traffic violations and the county is responsible for collecting all debt related to felony offenses. However, while collection activities may be delegated among various entities, either the county or the court will serve as the primary administrator of the collection program. According to Judicial Council staff, courts are currently the primary administrator of collection programs in about two–thirds of the state’s counties.

Numerous Entities Have a Role in Collections. A number of public and private entities participate in the court–ordered debt collection process. The exact role and responsibilities of these entities varies widely across the state. We provide a general description of how each entity participates below.

- Trial Courts. Each of California’s 58 trial courts (one per county) oversees the disposition of all criminal and civil cases in its jurisdiction. Upon resolution of these cases, each court generates an order detailing its decision, which includes any court–ordered debt owed by a convicted individual. Once these orders are entered into court case management and financial systems, courts begin collection activities themselves or transfer the information in the orders to another collecting entity, such as a county agency or private vendor.

- County Agencies. As described above, some counties collect some or all of the court–ordered debt. In these cases, typically revenue recovery units within the County Treasurer/Tax Collector’s Office handle the collections for the county. In some counties, however, other agencies handle court–ordered debt collections (such as the Local Child Support Agency Office). Counties are responsible for submitting all revenues obtained by a collection program—after deducting its share of the revenue—to the State Controller’s Office (SCO) monthly.

- Judicial Council. The Judicial Council serves as the governing and policymaking body of the judicial branch. Although counties are statutorily responsible for collections, state law requires the Judicial Council to oversee collection programs by adopting operational guidelines, developing performance measures and benchmarks, and submitting annual reports to the Legislature. Its staff also provides guidance and assistance to collection programs. Specifically, the staff coordinates data collection, helps develop and implement best practices, helps negotiate contracts for third–party collection services, and assists with the distribution of collected revenues.

- Collection Vendors. Collection programs may contract with private vendors for the collection of nondelinquent or delinquent court–ordered debt. These vendors provide specific services in exchange for a percentage of the amount they collect. Currently, collection programs typically contract with one (or more) of the 11 vendors who have negotiated contracts with Judicial Council.

- FTB. Collection programs can also contract with FTB for the collection of delinquent court–ordered debt. The board offers two different services to collection programs. First, the board’s Tax Intercept Program, which is operated in partnership with SCO, intercepts tax refunds, lottery winnings, and unclaimed property from individuals who are delinquent in paying court–ordered debt. An administrative fee is charged for each successful intercept. Second, the Court–Ordered Debt Collection Program identifies debtors’ assets through automated searches of wage and financial records. The FTB then administratively issues levies against these assets or orders the withholding of funds to meet debt obligations. The FTB only contracts with courts and county agencies for the collection of debt that is more than 90 days delinquent, and retains up to 15 percent of collected revenue to cover administrative costs of the Court–Ordered Debt Collection Program.

- SCO. The SCO receives collected revenues from the counties on a monthly basis and oversees their distribution to the appropriate funds. In addition to participating in FTB’s Tax Intercept Program, the SCO also routinely audits collection programs to ensure that they record and designate debt revenues appropriately amongst numerous state and local funds. The SCO assesses monetary penalties against collection programs for inaccurate distributions.

- Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). Collection programs also partner with DMV for assistance in the collection of delinquent court–ordered debt. The DMV will suspend the driver’s license of individuals when they receive notification from collection programs that the individuals have delinquent court–ordered debt. The DMV typically removes holds on driver’s licenses after five years if the collection program has not already requested their removal.

How Is Court–Ordered Debt Collected?

Collection of Nondelinquent Debt. The first stage of the collection process begins with the collection of nondelinquent debt. This may occur when individuals choose not to contest a violation and instead submit full payment of their debt (for example, paying a traffic ticket). It may also occur after the court has issued a final ruling in traffic or criminal proceedings. In both scenarios, the exact amount owed by the individual is calculated by the court based on statutory requirements, though judges have discretion to reduce or waive some fines and fees. Individuals who plead guilty or are convicted of traffic violations or criminal offenses must either provide full payment immediately or set up installment payment plans. When setting up installment payments, court or collections staff obtain personal, contact, and financial information to establish a payment record for each individual. Courts can then use this information to send monthly payment reminders or billing slips to help individuals maintain timely payments.

Collection of Delinquent Debt. If an individual does not pay on time, the collections process enters the second stage—the collection of delinquent debt. The agency responsible for collecting nondelinquent debt (such as the court or a private vendor) converts the payment record into a collections account and transfers it to the entity responsible for the collection of delinquent debt. In some cases, the same entity collects both nondelinquent and delinquent payments.

Nearly all collection programs utilize a variety of tools to motivate individuals to pay their debt. Most delinquent individuals first receive a mailed courtesy notice outlining the punitive actions that they will face if payment is not made by a specific date. (Some collection programs provide this notification after individuals become delinquent, while others provide notification immediately prior to the individual becoming delinquent.) Under state law, delinquent collection activities and sanctions can commence after a minimum of ten calendar days of that notification.

Often times, collection programs have relatively little contact information for debtors, particularly for those who did not provide the court with personal information as part of establishing installment plans. Programs may also have out–of–date contact information if, for example, the debtor has moved. Thus, collection programs often need to locate debtors. These programs commonly use a process called “skip tracing” to do so. Skip tracing involves using a wide range of public records (such as phone or criminal records and license or credit reports) to locate an individual. Some programs also use tools like predictive dialers, which are automated telephone systems that dial phone numbers in an order intended to maximize the number of debtors each collection agent is able to successfully contact. This is because the system focuses on connecting collection agents to only those phone numbers where individuals actually answer the phone. This enables collectors to contact debtors efficiently to encourage them to make payments. These automated systems can also efficiently direct incoming calls from debtors to the next available collection agent. This helps debtors seeking to resolve their cases reach a collector more quickly and efficiently.

As indicated earlier, when the ten–day notification period has passed without payment, programs can begin utilizing punitive sanctions. One of the first sanctions typically used by collection programs is a civil assessment. State law authorizes collection programs to impose a $300 civil assessment against any individual who fails to either pay court–ordered debt or appear in court without good cause. Another sanction that is typically used early in the process is the suspension of the debtor’s license by the DMV. When collection programs notify the DMV of the individual’s debts, the DMV suspends the debtor’s license.

If these individuals continue to remain delinquent after the above sanctions are implemented, collection programs can apply additional sanctions. These can include wage garnishments, bank levies, or liens placed on assets. Typically, collection programs progressively add sanctions used in order to gradually increase pressure on debtors to make payments. If a collection program determines that it has been unsuccessful at collecting payments from an individual despite imposing sanctions, the program can refer the account to other collecting entities, such as a private collection vendor or to FTB. These entities can impose most of the same sanctions described above. Private or FTB collection programs receive a share of any delinquent debt they collect. For example, state law authorizes FTB to charge an administrative fee of up to 15 percent of court–ordered debt collected. (The FTB currently aligns its fee with the actual cost of collections.) At any point in the process, debtors may contact the appropriate collections entity to either make a full payment or reestablish installment payments, thereby halting collection sanctions.

Discharging Delinquent Debt. A collection program may determine that the amount of debt it is pursuing is too small to justify the cost of collection. In such cases, state law authorizes the program to seek a “discharge of accountability.” When debt is discharged, debtors are still liable for their debts, but the collection program is no longer obligated to actively pursue the debt. This reduces how much outstanding court–ordered debt is “on the books.” Either the collection program’s county board of supervisors or the presiding justice of its court must approve the discharging of debt.

Actual Collection Process Varies Across Counties. Individual collection programs generally follow the process outlined above and have access to the same types of tools and sanctions as one another. However, each program can vary in (1) how much information it collects from debtors, (2) how it uses collection tools and sanctions, (3) when it leverages specific sanctions, and (4) the amount of staff or other resources the program dedicates to collection efforts. These variances lead to collection programs collecting different amounts of debt and differences in the portion of that debt that is nondelinquent versus delinquent.

How Much Court–Ordered Debt Has Been Collected?

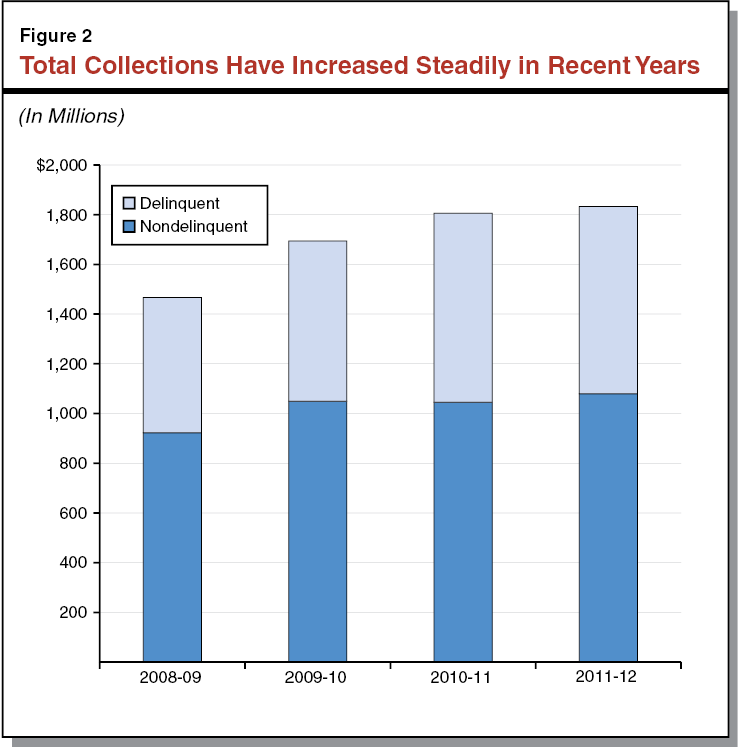

Amount Collected Annually. Based on available data in Judicial Council reports, the total amount of court–ordered debt collected has increased annually since 2008–09. As shown in Figure 2, total collections increased by over $350 million—from just over $1.4 billion in 2008–09 to an estimated $1.8 billion in 2011–12. The $1.8 billion collected in 2011–12 includes about $1.1 billion (59 percent) in nondelinquent debt and about $750 million (41 percent) in delinquent debt. However, this data likely understates the total amount collected—particularly the total amount of nondelinquent debt collected. As we discuss later, this results from the incomplete collection of data—meaning actual collections may be tens of millions of dollars higher. Regardless, the total amount actually collected is only a small fraction of the total outstanding balance of debt owed by defendants, as we discuss below.

Amount of Outstanding Debt. Every year, the courts estimate the total outstanding balance of debt owed by defendants. This balance may decrease when defendants make payments or debt is resolved in an alternative manner, such as when a portion of a debt is dismissed because the debtor performs community service in lieu of payment. However, this amount generally grows each year as some amount of newly assessed court–ordered debt goes unpaid and is added to the amount of unresolved debt accumulated from prior years. As shown in Figure 3, an estimated $10.2 billion in court–ordered debt remained outstanding at the end of 2011–12. This is basically the amount of delinquent debt, as adjusted for discharged debts.

How Does the Judicial Branch Measure Success?

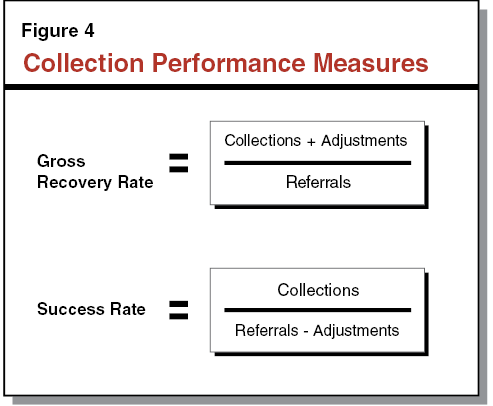

Metrics Used by Courts. State law requires the Judicial Council to develop performance measures for collection programs. Accordingly, the Judicial Council adopted the use of two ratios—the “gross recovery rate” (GRR) and the “success rate” (SR)—to measure the performance of collection programs in collecting delinquent debt. These indicators are commonly used by the collections industry and are designed to measure the ability of a program to successfully collect payments owed. The GRR and SR are similar in that they both rely on the same three pieces of data: (1) the amount of delinquent debt established and referred for collection activities (“referrals”), (2) the amount of delinquent debt actually collected (“collections”), and (3) various changes to the initial amount of debt owed (“adjustments”). Adjustments could increase the amount of debt owed, such as from increased fees assessed on debtors whose checks “bounce” due to insufficient funds. On the other hand, some adjustments could reduce the amount of debt owed, such as from dismissals of debt by the court, use of alternative payments (community service for example), and discharges of debt by collection programs.

While the GRR and SR rely on the same data, they differ in how they incorporate adjustments, as shown in Figure 4. Specifically, the GRR measures the percent of total delinquent debt referred that was addressed through either collections or adjustments. In other words, the GRR does not differentiate how the debt was resolved. In contrast, the SR focuses specifically upon the ability of a collection program to resolve delinquent debt through the collection of actual payments. Specifically, this ratio measures the amount of delinquent payments actually collected as a percentage of the amount referred after any adjustments have been made.

Performance of Collection Programs. In addition to developing performance measures for collection programs, state law requires the Judicial Council to set performance benchmarks for these measures. Accordingly, the Judicial Council established performance benchmarks of 34 percent for the GRR and 31 percent for the SR. In 2011–12, Judicial Council staff calculated that 50 programs (86 percent) exceeded both the GRR and SR benchmarks. The exact performance of collection programs varied greatly. (Later in this report, we assess whether the GRR and SR as calculated by the Judicial Council adequately measure the performance of collection programs.)

How Are Court–Ordered Debt Revenues Distributed?

State law dictates how debt revenue is allocated. For example, as we discuss in more detail below, state law authorizes collection programs that engage in a certain number and type of collection activities specified in state law to offset operating costs related to the collection of delinquent debt. State law also specifies how to distribute revenue among various state and local funds for specific purposes (such as the State Penalty Fund and the Driver Training Penalty Assessment Fund) and prioritizes the order in which revenue is deposited in these funds.

Cost–Recovery for Delinquent Debt Collections. Collection programs are designated as “comprehensive collection programs” if they engage in a certain number and type of collection activities identified in state law. Such activities include accepting payments by credit card, attempting telephone contact to inform debtors of their delinquent status and payment options, and using the FTB Tax–Intercept or Court–Ordered Debt Collection Program services. The benefit of being a comprehensive collection program is that state law allows such programs to recover most operating costs related to the collection of delinquent court–ordered debt. State law does not allow these programs to be reimbursed for the costs related to collecting certain debts—primarily victim restitution payments. Thus, after collecting sufficient revenues to fulfill a defendant’s victim restitution obligation, collection programs may then recover their operating costs before the remaining revenues are distributed to other state and local funds. In 2011–12, collection programs in 57 of the state’s 58 counties were designated as comprehensive collection programs. These programs retained about 16 percent of the total delinquent revenue they collected to offset their costs.

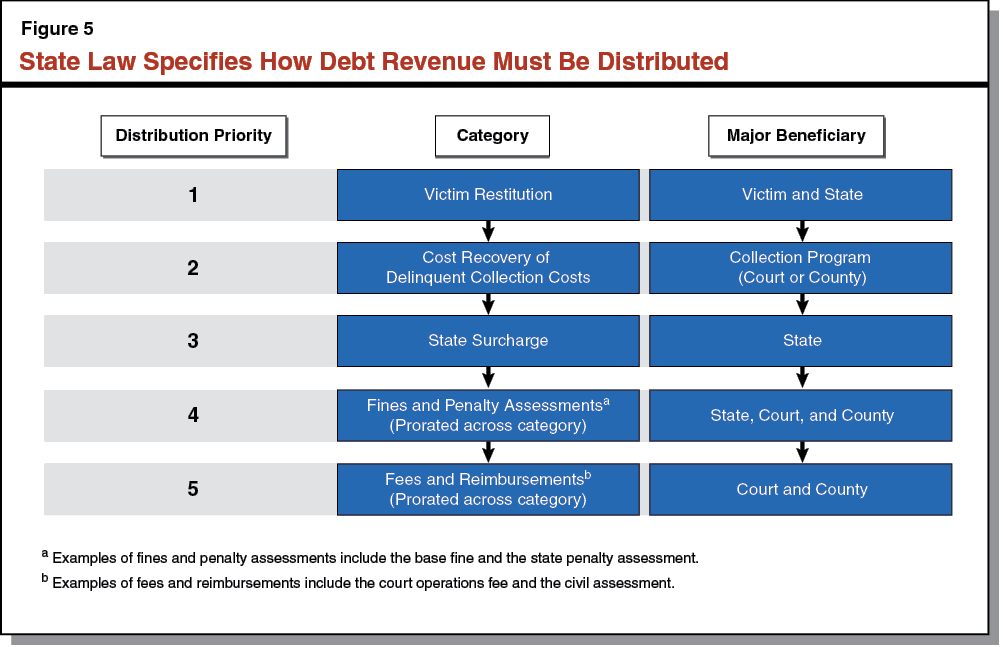

Distribution of Collections to State and Local Funds. State law specifies the order in which the payments collected from an individual debtor are to be used to satisfy the charges added to the base fine. As shown in Figure 5, state law specifies that payments from an individual be (1) first used to satisfy victim restitution debts, (2) then used to offset the cost of delinquent collections for eligible collection programs, (3) then used to satisfy the state surcharge, (4) then used to satisfy all fines and penalty assessments on a prorated basis, and (5) finally used to satisfy all fees and reimbursements on a prorated basis. Because the debt in each of these categories must be fully satisfied before revenue is disbursed to the next category, counties and courts operating the collection programs generally benefit only towards the end of the collection process. As a result, if an individual makes partial payments or pays in installments, counties or courts may pursue debt for some time with no guarantee they will actually receive their full distribution. This provides courts and counties with only a limited incentive to collect revenue.

The base fine and each of the various fees, forfeitures, penalty surcharges, assessments, and restitutions added to it each fall within the various categories described above. For example, the state penalty assessment falls into the fourth distribution priority. As a result, it is fulfilled when revenue is distributed on a prorated basis to all fines and penalty assessments that were owed by an individual. State law then further specifies how the base fine and various additions to it will then be distributed among various state and local funds. For example, state law requires that 70 percent of the state penalty assessment added to a base fine be deposited into the State Penalty Fund. The state’s share of this assessment revenue is then subsequently split among nine state funds (such as the Peace Officers Training Fund and the Restitution Fund) with each receiving a certain percentage specified in state law. The other 30 percent of the assessment goes to the county General Fund. Collection programs must carefully track and record how collected funds should be deposited in accordance to numerous state laws. Programs submit this information, along with the collection revenue, to the county for (1) distribution to county funds and (2) transfer to the SCO for subsequent distribution to state funds.

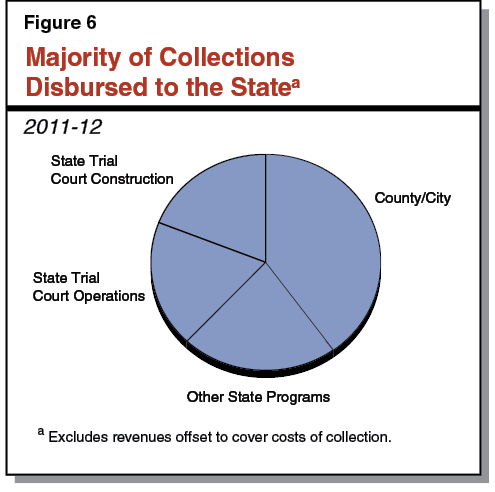

Entities Benefiting From Collection Distributions. Total distributions of debt revenue to specific state and local funds vary annually and depend in large part on the number and type of traffic violations and criminal offenses committed. It also depends on how individuals fulfill their debt obligations (such as through installment payments or paying debt once it becomes delinquent). Based on the limited data that is currently available (and excluding revenues offset for cost–recovery), Figure 6 shows that roughly 40 percent of the total remaining revenue from court collections in 2011–12 went to local governments (primarily counties) where the underlying offenses occurred, while roughly 60 percent went to the state. Of the amount that went to the state, nearly two–thirds supported trial court operations and construction. The remainder supported various other state programs such as victim/witness assistance and peace officer training. Of the amount allocated to trial courts, roughly half funded statewide trial court projects (such as trial court construction and technology projects), and the other half supported trial court operations. However, only a small portion of the total amount received by each trial court is tied to how effectively the program is able to collect debts. (As we discuss in the nearby box, a task force established by the Judicial Council is currently considering how to simplify the assessment and distribution of various fines and fees.)

Task Force Reviewing Complexity of Fine and Fee Assessment and Distribution

State law requires that certain fines and fees be added to the base fine assessed for a traffic or criminal violation. Various laws dictate how to distribute the base fine and each additional charge among a wide range of state and local funds. Because the distribution of each individual fine varies, it can be difficult for trial courts and collection programs to correctly calculate, record, and track the allocation of these revenues. A number of courts have reported to us that this complexity is exacerbated by a lack of up–to–date technology that would allow these calculations to be automated and updated as laws change. In fact, we are informed that some collection programs do these calculations manually, increasing the likelihood of error.

In recognition of the above complexity of the state’s fine and fee structure, the Legislature directed the Judicial Council in 2010 to establish a 21–member taskforce to examine how court–ordered debt is assessed and how the resulting revenues are distributed. (The Legislature initially directed the Judicial Council to establish such a taskforce in 2007, but amended the directive in 2010.) The panel consists of state, local, judicial branch, and other criminal justice stakeholders. Existing state law requires the task force to (1) identify all fines, fees, forfeitures, penalties, and assessments imposed for traffic violations or criminal offenses; (2) identify how these revenues were distributed and used; (3) consult with stakeholders on who would be impacted by a simplified structure; and (4) recommend opportunities to simplify the assessment and distribution of court–ordered debt revenues. The taskforce submitted a preliminary report in June 2011. Although the report did not include conclusive recommendations (such as steps to simplify the assessment and distribution of debt revenues), the task force indicated that it would continue its work in this area and issue a subsequent report. To date, such a report has not been submitted to the Legislature.

Based on our analysis and discussions with various stakeholders in the collection process, we identified a number of weaknesses in the current court–ordered debt collection process. Specifically, we find that (1) there is a lack of clear fiscal incentives for cost–effective collections, (2) it is difficult to comprehensively evaluate the performance of collection programs, and (3) the current division of responsibilities between the courts and counties can undermine oversight and make modification of collection programs difficult. Figure 7 provides a summary of our findings, which we discuss in greater detail below.

Figure 7

Weaknesses of the Current Court–Ordered Debt Collection Process

- Lack of Clear Fiscal Incentives for Cost–Effective Collections

- Limited fiscal incentive for counties to collect debt.

- Even less fiscal incentive for courts to collect debt.

- Little fiscal incentive to collect nondelinquent debt.

- Current cost–recovery approach does not incentivize efficiency.

- Current incentive structure can penalize cost–effective collection programs.

|

- Difficult to Comprehensively Evaluate Performance of Collection Programs

- Incomplete and inconsistent reporting of total collections and distributions.

- Minimal reporting of nondelinquent collection costs and revenues.

- Miscalculation and lack of performance measures for delinquent collections.

- Lack of evaluation of collection practices.

- Lack of data on collectability of outstanding debt.

|

- Current Division of Responsibilities Can Undermine Oversight and Make Program Modification Difficult

- Limited oversight of collection programs.

- Program changes more difficult to make.

|

Lack of Clear Fiscal Incentives for Cost–Effective Collections

The current collection process provides limited fiscal incentives to encourage counties and courts to maximize the collection of debt revenue in a cost–effective manner. Failure of collection programs to maximize collections and operate cost–effectively means less financial resources are available to courts and other state and local programs.

Limited Fiscal Incentive for Counties to Collect Debt. Counties have limited incentive to maximize the collection of court–ordered debt. As discussed previously, the majority of court–ordered debt revenue collected goes to the state. Thus, counties have a greater incentive to focus on collecting other forms of debt that they keep a greater share of—such as probation fees or medical billings—at the expense of court–ordered debt. In addition, the county incentive to collect court–ordered debt is further reduced by the way state law prioritizes the distribution of debt revenue from payments made by debtors. Specifically, counties do not begin to benefit from their collection efforts until restitution and the state surcharge obligations have been completely paid. If a debtor is making partial payments, completely fulfilling these two obligations can result in counties investing in collection activities over a lengthy period of time before they even begin to benefit from their collection activities. This further reduces the fiscal incentive counties have to invest in collection activities because there is no guarantee that such an investment will actually generate a sufficient net increase in the revenue they retain.

Even Less Fiscal Incentive for Courts to Collect Debt. Current statute provides even less incentive for courts to collect debt. As discussed previously, courts also do not begin to benefit from their collection efforts until restitution and state surcharge obligations have been completely paid. In addition, an individual trial court’s incentive to collect is further reduced because the amount of revenue it receives from collections is only partially tied to its performance as reflected in how much revenue it collects. As discussed previously, nearly 40 percent of debt revenues in 2011–12 went to the state trial courts. However, roughly half of these revenues are set aside to fund specific statewide trial court projects (such as trial court construction and technology). The allocation of such funds occurs primarily on a project–by–project basis based upon statewide priorities and need. Thus, these funds may not directly benefit the trial courts collecting the revenue. The remaining half of revenue for trial courts is used to fund trial court operations. This revenue—with the exception of the civil assessment—is allocated by Judicial Council to the courts based on factors, such as workload, that are not related to the amount collected.

Little Fiscal Incentive to Collect Nondelinquent Debt. Because collection programs are not reimbursed for the costs of collecting nondelinquent debt, they have little fiscal incentive to use a large share of their resources to improve the collection of such debt, such as by purchasing kiosks or constructing payment windows to bypass security to make it easier for debtors to pay. Rather, programs generally focus their resources on collecting delinquent debt. This is problematic for two primary reasons. First, the collection of delinquent debt is significantly more expensive and difficult than the collection of nondelinquent debt. This is because more effort is typically necessary to locate and communicate with delinquent debtors. Accordingly, focusing on the collection of delinquent debt at the expense of nondelinquent debt can increase the overall cost of collections. Second, minimal effort to collect nondelinquent debt can also negatively affect the amount of delinquent debt collected. Based on our discussions with collection administrators and experts, activities related to the collection of nondelinquent debt increase the likelihood of collecting delinquent debt. For example, collecting personal information early on to facilitate nondelinquent collections also allows programs to quickly and cost–effectively locate and communicate with individuals whose debt becomes delinquent. According to program administrators, the quicker a program reestablishes contact with a delinquent debtor, the more likely the delinquent debt will be paid.

Current Cost–Recovery Approach Does Not Incentivize Efficiency. Allowing collection programs to recover operational costs related to delinquent collections regardless of how high those costs are and how much debt is actually collected provides no incentive to operate efficiently. This is problematic because, if more resources than necessary are being devoted to collections, less revenue is available for distribution to the state and local governments. In 2011–12, collection programs used about 16 percent of the delinquent debt they collected to offset most of their delinquent collection costs. However, programs exhibit a wide variation of delinquent collection costs. Programs ranged from using a high of 49 percent to a low of 6 percent of their delinquent collections on collection operations. This suggests that some programs may be spending more than is necessary to collect delinquent debt.

Current Incentive Structure Can Penalize Cost–Effective Collection Programs. Because the current structure does not closely tie fiscal benefits to the performance of collection programs and does not incentivize nondelinquent collection, it can penalize collection programs operating in a cost–effective manner. Specifically, a collection program that focuses on the cost–effective collection of nondelinquent debt may benefit less than a similar program that focuses on the less efficient collection of delinquent debt. The court that chooses to focus on the collection of nondelinquent debt likely maximizes its collection of total revenue and minimizes its operational costs as it collects debt earlier and reduces the amount of debt that becomes delinquent. Accordingly, it collects relatively little delinquent debt, but contributes more revenue for distribution to the state and local governments. However, this court is unable to recover most of its operating costs and will receive a lower amount of civil assessment as it collects less delinquent revenue. In contrast, the other court that chooses to focus only on the collection of delinquent debt likely collects less total revenue and has higher operational costs as more of its debt becomes delinquent. Although it collects relatively more delinquent debt, it contributes proportionately less revenue for distribution to the state and local governments. Despite this, it is able to recover most of its operating costs.

Difficult to Comprehensively Evaluate Performance of Collection Programs

Currently, it is difficult to comprehensively evaluate the collection process. In particular, there is (1) incomplete and inconsistent reporting of total collections and distributions, (2) minimal data on nondelinquent collections, (3) miscalculation of performance measures for delinquent collections, (4) a lack of evaluation of collection practices, and (5) a lack of data on the collectability of outstanding debt.

Incomplete and Inconsistent Reporting of Total Collections and Distributions. The state currently lacks complete data on the collection and distribution of court–ordered debt revenue, which makes it difficult for the state to ensure fiscal accountability. For example, each of the various records maintained by the Judicial Council and SCO omit different pieces of data. As described previously, counties submit debt revenues and information on how these revenues should be distributed among state funds to SCO on a monthly basis. However, SCO does not receive—and thus does not record—the amount kept by counties or cities. The Judicial Council also compiles a separate, unaudited record of how these collections revenues should be distributed among various local government funds and state trial court funds. However, the council does not keep records on all of the state funds that receive revenues.

Moreover, there appear to be inconsistencies between some of the data that is collected by the Judicial Council and SCO, which further limits the ability of the state to oversee and evaluate collection programs. For example, in 2011–12, the SCO reported about $3.5 million more in revenue distribution to one court construction account than was reported by the Judicial Council. Compounding this problem, there also appears to be a lack of consistency in how collection programs report data to the council. For example, programs appear to report the transfer of collections cases from one collecting entity (such as the court) to another entity (such as FTB) differently. These incomplete and inconsistent records make it difficult to know with certainty the amount of revenues collected and whether they have been properly distributed among state and local funds. We note that in recent months the Judicial Council has taken initial steps to (1) increase training to promote greater standardization in reporting of data across the various entities involved in collections and (2) better reconcile collections and distribution data.

Minimal Reporting of Nondelinquent Collection Costs and Revenues. Collection programs do minimal reporting of data on nondelinquent collections. Specifically, some collection programs do not report the amount of nondelinquent debt they collect and none report the costs of collecting this debt. This is because there currently are no mandatory reporting requirements related to the collections of nondelinquent debt, which is problematic for two reasons. First, without such information it is difficult to accurately evaluate the ability of collection programs to collect nondelinquent debt. Second, the outcomes of nondelinquent collection efforts can directly affect the cost and success of delinquent debt collection. Yet, despite this, the judicial branch only evaluates its delinquent collection programs. Without complete reporting and subsequent analysis of nondelinquent collections, the Judicial Council cannot provide a comprehensive and accurate evaluation of the overall performance and cost–effectiveness of collection programs.

Miscalculation and Lack of Performance Measures for Delinquent Collections. Our analysis indicates that the judicial branch systematically miscalculates the performance metrics it uses to evaluate the effectiveness of collection programs—the GRR and SR. As used in the collections industry, the GRR and SR are supposed to be calculated based on a program’s ability to collect or resolve referrals made within a specific time period, such as during a particular month or year. This allows entities to compare performance across different time periods. The judicial branch, however, calculates each ratio based on data from different time periods. Specifically, the branch uses data that captures collections of (and adjustments made to) all debt in the given time period, regardless of whether the debt was referred in the same time period or earlier. For example, to accurately calculate the GRR for 2011–12, only collections or adjustments made in 2011–12 related to debt referred to the collection program in 2011–12 should be included in the calculation. The judicial branch, however, inputs the amount of collections or adjustments made in 2011–12—regardless of whether they are related to debt referred to the program in 2011–12.

This miscalculation of the formula makes it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about the performance of collection programs from the GRR and SR data reported by the judicial branch. In fact, the specific way the branch applies the formula generally results in ratios that overestimate the successful performance of each collection program. In some cases, courts have actually reported collection rates exceeding 100 percent, a result that would not be possible if the branch appropriately used these formulas. The judicial branch indicates that calculating the GRR and SR in the correct way would be difficult because a number of courts currently lack the technology needed in their case management or collection management systems to compile and report such data.

Furthermore, we would note that there is a lack of other performance metrics—such as cost–effectiveness measures—that are essential in comprehensively evaluating the effectiveness of collection programs. The state could use such cost–effectiveness measures to evaluate whether programs were spending the appropriate amount to resolve debt through the collection of actual payments (as shown by the SR) versus resolving them generally through other means (as shown by the GRR). This type of information would enable the state to conduct greater oversight of how effectively collection programs pursue debt.

Lack of Evaluation of Collection Practices. As discussed above, a number of collection best practices have been identified (1) in state law for the purposes of qualifying as a comprehensive collection program eligible for cost–recovery and (2) by the Judicial Council as additional best practices. Generally, there has been a lack of evaluation to determine whether these collection best practices are cost effective. In addition, collection programs have flexibility in deciding which best practices they adopt and how they implement any of the practices they adopt. From our review of data and conversations with local collection practitioners, programs seem to interpret these best practices differently. For example, not all programs comply with the best practice of sending monthly bills or account statements to all delinquent debtors. Of those that do comply with this practice, programs differ in how they provide such notice. Without an evaluation of the best practices identified by the Judicial Council and state law, it is difficult to determine the effectiveness of such practices and whether the specific ways in which individual collection programs implement these practices are cost effective. Although a Judicial Council task force convened in 2010 to examine court–ordered debt initially indicated that it would evaluate the best practices, it is unclear if or when this study will be conducted.

Additionally, we are informed that a number of collection programs have identified and implemented additional local collection practices—not identified by the state—that they believe improved their success in collecting court–ordered debt. Despite the promise of some of the practices, it does not appear that the Judicial Council has conducted an evaluation of the cost–effectiveness of these practices. Without such an analysis, it is difficult to determine whether these practices, or specific methods of implementing such practices, are cost–effective and should be promoted statewide. (Please see the text box below for additional information on some of these promising practices.)

Examples of Promising Practices Implemented by Collection Programs

Although statute and the Judicial Council identify certain collection best practices, collection programs throughout the state have implemented practices not currently identified by the state as best practices. In our discussions with some collection program administrators, they indicated that in their view many of these practices are also effective. A few examples of such local practices are provided below.

Obtaining Payment Commitments Immediately Upon Adjudication. Some collection programs attempt to obtain payment commitments from individuals immediately upon the resolution of their traffic and non–traffic criminal proceedings. Doing so allows the collection programs to work in conjunction with debtors to immediately set up payment plans. This increases the likelihood of debtors making payments to the courts—potentially increasing the amount of debt collected. According to a number of program administrators, failure to secure payment or establish payment plans before the debtor leaves the courthouse greatly increases the likelihood that the debt will become delinquent, and thus more expensive to collect. Some programs—such as in Shasta County—obtain payment commitments early in the process by stationing collections staff inside courtrooms concurrently with court proceedings. Similarly, in Ventura County, debtors are required to exit the court directly into the collections office.

Making the Collection Process User–Friendly for Debtors. Other programs utilize various tools to make the collections process more user–friendly for debtors. For example, some programs use tools that make it easier for collections staff and debtors to quickly reach each other, such as predictive dialers. This improves the likelihood that debtors make necessary adjustments (such as amending payment plans) to keep from becoming or remaining delinquent. Programs also use tools that help make it more convenient for individuals to pay their debt, such as by (1) extending the hours of operation for collections units to make them more accessible to working individuals, (2) allowing the scheduling of court appearances via kiosks or the Internet, (3) providing payment kiosks in court buildings to reduce lines, and (4) routinely attempting to contact delinquent debtors after regular business hours. We note that at least one court even installed payment windows on the exterior of the building to allow individuals to make payments more quickly by not having to enter the courthouse and go through the security line. It is likely that payment convenience increases the probability that debtors will make their payments in a timely manner.

Other Changes to Make the Collection Process More Cost–Effective. Some programs implemented other changes to help them operate more cost–effectively. For example, rather than have judges calculate the amount of court–ordered debt owed by an individual upon conviction, as well as set specific payment terms during court proceedings, some programs delegate such responsibilities to designated administrative staff. This helps reduce operating costs by more efficiently utilizing judicial court time. Marin County reported that such delegation of duties in traffic cases greatly reduced the number of cases appearing before a judge, thereby reducing the amount of court time needed to resolve such cases. Additionally, some programs vary in their use of collection sanctions. For example, collection programs may apply a $300 civil assessment once debt becomes delinquent. Los Angeles County encourages delinquent individuals to resume payments by offering to partially waive the civil assessment imposed if debtors made payment in full within a certain time period after becoming delinquent. This incentive helps increase the amount of debt collected while reducing the amount of effort required to collect the debt.

Lack of Data on Collectability of Outstanding Debt. A number of collection programs do not assess the collectability of their delinquent debt despite the fact that current law allows them to discharge debt that would be expensive to try to collect. In total, an estimated $10.2 billion in court–ordered debt remained outstanding as of the end of 2011–12. However, a large portion of this likely consists of debt whose cost to collect outweighs the actual amount collected. Pursuing such debt is inefficient and reduces the amount of debt revenue available for distribution to the state and local governments. Compounding the problem, a number of programs refuse to discharge any debt and instead allow delinquent debt to accumulate on their books, increasing the amount of outstanding debt that is uncollectible. Without an analysis of the collectability of this debt, it is unknown what portion of the total outstanding balance should be discharged or the extent to which courts are attempting to collect such debt.

Current Division of Responsibilities Can Undermine Oversight and Make Program Modification Difficult

As discussed previously, statute currently requires that courts and counties maintain the structure of the collection program that was in place in 1996 unless both parties agree to changes. This results in programs preserving divisions of responsibility that can undermine the oversight and modification of such programs.

Limited Oversight of Collection Programs. Existing state law provides the Judicial Council with oversight and policymaking authority over collection programs. However, as the governing and policymaking body for the judicial branch, the Judicial Council technically only has authority over actions taken by trial courts. This makes it difficult for Judicial Council to effectively oversee counties involved in collection programs as they generally have no control over county decisions.

Program Changes More Difficult to Make. The statutory preservation of the division of responsibilities between courts and counties can also inhibit structural changes in collection programs, as it requires that both parties agree to any proposed changes. For example, it might be more cost effective for a program to consolidate all of its collections with either the court or the county, instead of dividing collections between both parties. However, because any structural changes to the program require agreement from both the county and the court, such changes—even if they are in the best interest of the program—would not be implemented as long as either the county or court objected to the proposed change.

In this report, we reviewed the collection of court–ordered debt and raised several concerns with the existing process. Based on our findings, we make several recommendations to improve the collections process in order to meet the state’s goals of collecting debt in a cost–effective manner that maximizes revenue for state and local governments. First, we recommend realigning the current court–ordered collection process by shifting responsibility for debt collection to the trial courts and implementing a new collections incentive model. This restructured process would consolidate collections responsibility with the entity best suited for managing collections and provide the necessary incentives to increase collections of debt in a cost–effective manner. Second, we recommend improving data collection and measurements of program performance to enable a comprehensive evaluation of court–ordered debt collections. In combination, we believe these recommendations will promote more cost–effective collections and greater accountability and would increase the amount of revenue collected in the future. Figure 8 provides a summary of our recommendations, which are discussed in greater detail below.

Figure 8

Summary of LAO Recommendations

- Realign Court–Ordered Debt Collection Process

- Shift collections responsibility to trial courts.

- Pilot new collections incentive model.

|

- Improve Data Collection and Measurements of Program Performance

- Require consolidated reporting on collections.

- Require reporting on nondelinquent collections.

- Improve performance measures.

- Direct Judicial Council to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of collection best practices.

- Conduct a collectability analysis.

|

Realign Court–Ordered Debt Collection Process

Shift Collections Responsibility to Trial Courts

We recommend that the Legislature consolidate responsibility for collections with one entity. This would eliminate current statutory requirements that maintains the division of collection responsibilities between courts and counties unless both agree to changes, thereby allowing the Legislature to hold, one entity responsible for effective collections of court–ordered debt. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature amend state law to shift responsibility for collections from the counties to the trial courts. Under our proposal, the courts would retain the ability to contract with the county or other local agencies, FTB, or third party vendors for actual collection duties. However, the trial courts would retain primary responsibility for the collection program. This means that one entity—the courts—would be accountable for the performance of collection programs.

We recommend giving the courts primary responsibility for collection of court–ordered debt for the following two reasons.

- Courts Best Positioned to Interact With Debtors. The court is in the best position to interact with a debtor to accept payment, establish a payment plan, and collect the debtor’s personal information immediately upon adjudication of the case. Shifting full responsibility for collections to the courts could facilitate such initial contact. This type of immediate contact directly impacts the ability of programs to maximize their collection of both nondelinquent and delinquent debt in a cost–effective manner.

- Provides Increased Oversight of Collection Programs. Shifting responsibility for collections to trial courts would allow the Judicial Council to take on increased oversight of all aspects of collection programs, which could lead to greater consistency and accountability. For example, it could direct underperforming courts to make improvements in their collection programs. Such a shift would also allow the Judicial Council to enforce consistent and comprehensive data reporting—improving the accuracy of the collected data.

Pilot New Collections Incentive Model

New Incentive Structure for Collections. Given our concerns about the current lack of fiscal incentives for collecting court–ordered debt, we recommend replacing the existing cost–recovery model with a new incentive–based model. Under the new model, each court would retain a portion of the overall revenue it collected annually depending on its performance relative to a fixed base year. Regardless of the total amount of revenue collected, each court would be able to retain the amount necessary to offset their actual costs of collecting—up to the amount they received through the current cost–recovery model in the fixed base year. However, once a court collects the same amount of total debt (both delinquent and nondelinquent) it collected in the fixed base year, the court would then be able to retain a set percentage of the amount of new revenue it collects above the amount collected in the fixed base year. As a result, the incentive payment would not reduce the amount allocated to state and local funds. This “incentive percentage” would serve as a reward for improved collections performance and would be specified in statute. As a result, the Legislature could use the incentive percentage to influence how much courts spend to pursue debt collection. For example, if the Legislature wanted the courts to be more aggressive at pursuing delinquent debt, it could increase the incentive percentage to encourage courts to dedicate more resources towards collections. Courts would have complete discretion in how they use these incentive funds. For example, courts could offset their costs for collecting this additional revenue, fund further improvements in their collection programs, or support other court programs. These funds would be retained by the courts prior to the distribution of the remaining revenue to state and local funds, with the exception of revenues—such as victim restitution—that have first priority under current law. Only those collection costs currently eligible for cost recovery would be eligible under the new model. For example, collection costs related to victim restitution debt would remain exempt.

Implement Pilot of the New Incentive Structure. We recommend that the Legislature authorize a three–year pilot program to test the new incentive model prior to implementing it statewide. This is because the current incomplete and inconsistent reporting on collections, as well as the miscalculation of existing performance measures, make it difficult to determine the optimal value for the incentive percentage. In addition, a pilot is necessary as it is difficult to estimate the potential impact that our proposed incentive model would have on the total amount of debt collected and the amount distributed to state and local funds. To help answer these questions, we propose that the pilot include six courts (as selected by the Judicial Council) that vary in size, the robustness of their existing collection programs, and other characteristics to enable a comprehensive evaluation of the impacts of the model.

Based on our analysis of limited data, we sought to identify an incentive percentage for the pilot that would provide programs with sufficient incentive to continue collecting debt revenue until it was no longer cost–effective for the state that such debt be pursued. We believe that the rate of 25 percent meets this criterion because it would maximize the benefit to state and local governments while covering the operational costs of programs that appear to have made cost–effective investments in their collection efforts. Thus, for the purpose of the pilot program, we recommend that the incentive percentage be set at 25 percent. Accordingly, participating courts would be able to deduct $0.25 for every dollar collected beyond the amount collected in the fixed base year—recommended to be 2011–12 for the purposes of this pilot.

The courts participating in the pilot would be required to collect and report relevant data to the Judicial Council, such as the amount of nondelinquent and delinquent payments collected and the costs of such collections. This information would help demonstrate whether the new model provided the appropriate incentives needed to increase overall debt collection and how the amount of revenue received by the state and local governments was affected. The Legislature could then make modifications (such as adjusting the incentive percentage to a more appropriate value) based on the results of the pilot prior to statewide implementation.

New Structure Creates Incentive to Be Cost Effective. The proposed incentive model would provide various incentives for courts to operate cost–effective collection programs. Most importantly, the model effectively eliminates the distinction between nondelinquent and delinquent debt. This would encourage programs to reduce collection costs by focusing more on less expensive nondelinquent collections.

To help illustrate this effect, Figure 9 provides a hypothetical example of how the current law approach compares to the proposed incentive model. In our example, a collection program operating under current law collects $100 million in court–ordered debt at a cost of $18.5 million. However, under current law, the program is only able to offset its cost for delinquent collections ($15 million), and cannot offset its cost for nondelinquent collections ($3.5 million). Under the LAO model, the program collects the same amount of total revenue, but increases the proportion of revenue collected as nondelinquent. Because of the ability it has to spend money on collection activities more cost–effectively, the program can reduce its total costs of collection to $15.2 million. The program saves $3.3 million, in local resources that could be redirected to other local court activities.

Figure 9

LAO Incentive Model Provides Incentive to Be Cost–Effective

(In Millions)

|

|

Current Law

|

LAO Incentive Model

|

|

Collections

|

|

Nondelinquent

|

$35.0

|

$60.0

|

|

Delinquent

|

65.0

|

40.0

|

|

Total Collections

|

$100.0

|

$100.0

|

|

Costs of Collections

|

|

Nondelinquent collection costs

|

–$3.5

|

–$6.0

|

|

Delinquent collection costs

|

–15.0

|

–9.2

|

|

Collection cost payment

|

15.0

|

15.0

|

|

Net Cost to Collection Program

|

–$3.5

|

–$0.2

|

New Structure Creates Incentive That Would Increase Collections. The new model also provides courts with an incentive to increase the amount of debt revenue collected. First, the proposed model ties the amount a court is able to retain directly to its ability to increase total collections. This encourages courts to consider how to improve the way they operate their program rather than simply continuing to use methods they are familiar with. Second, courts would be particularly motivated to increase collections because of the discretion they would have to use the revenue they retain from increased collections. Finally, because the model ties the revenue retained to the total amount of debt collected—rather than just the amount spent on delinquent collections—programs would no longer have an incentive to neglect nondelinquent collections. Because nondelinquent debt is easier to collect, focusing more resources on it would likely increase overall collections as well as the proportion of debt that is collected as nondelinquent.

Figure 10 illustrates how the new model provides a program with incentive to increase overall collections. In this scenario, we assume the program increases its overall collections by 10 percent, for a total of $110 million, by (1) increasing its total collection costs from the $15.2 million in the above example to $16.7 million and (2) dedicating more resources to collect debt when it is nondelinquent. Because it collects more revenue, the program is able to retain $2.5 million as an incentive payment for increasing the amount it collected. This allows the program to save $4.3 million in local resources that could be redirected to other activities. Furthermore, the additional revenue that was collected increases the amount that is now available for distribution to the state and local governments.

Figure 10

LAO Incentive Model Provides Incentive to Increase Collections

(In Millions)

|

|

Current Law

|

LAO Incentive Model

|

|

Collections

|

|

Nondelinquent

|

$35.0

|

$66.0

|

|

Delinquent

|

65.0

|

44.0

|

|

Total Collections

|

$100.0

|

$110.0

|

|

Impact on Collections Program

|

|

Nondelinquent collection costs

|

–$3.5

|

–$6.6

|

|

Delinquent collection costs

|

–15.0

|

–10.1

|

|

Collection cost payment

|

15.0

|

15.0

|

|

Incentive payment

|

—

|

2.5a

|

|

Net Cost to Collection Program

|

–$3.5

|

$0.8

|

Improve Data Collection and Measurements of Program Performance

Require Consolidated Reporting on Collections

We recommend the Legislature make the Judicial Council responsible for coordinating the collection and consistent reporting of statewide data on court–ordered debt. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature direct the Judicial Council, SCO, and collection programs to consolidate and reconcile reporting on court–ordered collections. Consolidating reporting requirements with the Judicial Council will ensure consistent, complete, and accurate data reporting on court–ordered debt. This will help the council provide the Legislature with the information necessary to demonstrate with certainty the amount of revenues collected, the costs of such collections, and whether collected revenue has been properly distributed among state and local funds. In addition, making the Judicial Council responsible for overseeing reporting is particularly appropriate in light of our recommendation to shift collections responsibility to the trial courts.

Require Reporting on Nondelinquent Collections

In transitioning to the new incentive structure, we recommend the Legislature direct the Judicial Council to require collection programs to report on nondelinquent debt collections. Reporting data on the collection and cost of collection of nondelinquent debt would enable the state to better evaluate the overall performance of collection programs. This is critical because all court–ordered debt originally starts as nondelinquent and ultimately becomes delinquent when an individual fails to pay. Thus, actions taken and investments made to increase nondelinquent collections directly impacts the amount of delinquent debt collected and the cost of such collections. However, we would note that upon full implementation of the new incentive structure, the state should focus on evaluating overall debt collections.

Improve Performance Measures

We recommend the Judicial Council improve its collections performance measures by calculating GRR and SR in line with industry standards. Specifically, we recommend that the annual report of GRR and SR for each collection program be calculated using only those collections or adjustments made within that year related to debt that was referred to the collection program in that same year. This will prevent the standards from overstating the success of collection programs. However, we acknowledge that some courts indicate that they may not be able to provide this data due to a lack of technology, such as collections management systems that are able to track and report such information. In addition, the Judicial Council should develop and implement additional performance measures—such as return on investment, cost–benefit, and collection effectiveness ratios—that would apply to courts statewide. This would both allow for a better assessment of each program’s effectiveness and enable the comparison of the performances of all court–ordered debt collection programs. Additionally, all performance measures should be calculated using data for both nondelinquent and delinquent collections to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the success and effectiveness of entire collection programs. This would ensure the courts are able to better evaluate and improve their collection programs.

Direct Judicial Council to Conduct a Comprehensive Evaluation of Collection Best Practices

We recommend that the Legislature direct the Judicial Council to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of collection best practices currently implemented across the state, as well as those utilized by specific programs locally. The results of such an evaluation would allow the council to determine (1) which currently employed best practices or methods of implementation are most cost effective, (2) under what circumstances such practices would be most cost effective, and (3) whether to approve additional statewide collection best practices. The Judicial Council could then direct and assist collection programs to expand implementation of those best practices. This, in turn, could increase the total amount of debt revenue collected and distributed to various state and local funds.

Conduct a Collectability Analysis

We recommend that the Legislature direct the Judicial Council to work with collection programs to conduct an analysis to determine the collectability of outstanding court–ordered debt. As noted above, by the end of 2011–12, collection programs reported nearly $10.2 billion in outstanding court–ordered debt obligations. A collectability analysis—conducted internally by collection programs or externally by private collection vendors—could provide a more accurate understanding of how much of this outstanding balance could potentially be collected and at what cost. This analysis would consider a variety of factors including: the age of the account, prior collections activities used, prior sanctions imposed, the socio–economic characteristics of the debtor, and other debt owed by the debtor. While a collectability analysis may be costly and take time, such information would prevent collection programs from using resources on uncollectable debt and allow them to determine where they should direct their resources in order to increase collections. The analysis could also allow the Legislature to consider whether it would like to provide additional financial resources for collection programs to pursue this debt. For example, the Legislature could adjust the proposed incentive percentage to encourage programs to continue collecting up to the point it deems is in the best interest of the state. Finally, the Judicial Council could use the data on collectability to establish guidelines recommending or requiring programs discharge debts that meet approved criteria.

Based on our review of the existing collections process for court–ordered debt, we believe that improvements can be made to help increase collections of such debt and to subsequently increase the amount available for distribution to various state and local funds. Specifically, we recommend realigning the current court–ordered debt collection process to the courts, piloting a new collections incentive model, and improving data collection to enable comprehensive evaluations of the performance of collection programs.