California’s Child Care and Development System Serves Approximately 300,000 Children. California dedicates approximately $2 billion annually to subsidized child care and development programs. The state provides about 60 percent of this funding, with the federal government covering about 40 percent. (Revenue from family fees comprise a very small share of total funding.) California’s subsidized system serves approximately 300,000 children. Generally, the state’s subsidized programs are intended to enable low–income parents to work while also helping maximize the growth and development of their children. To be eligible for subsidized programs: (1) families must earn less than 70 percent of state median income (SMI), (2) children must be under the age of 13, and (3) parents must be working (with the exception of the State Preschool program).

Current System Has Several Serious Design Flaws. We believe California’s child care and development system has four major shortcomings.

- Similar Families Have Different Levels of Access. In the current system, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) families and certain former CalWORKs families are guaranteed services, whereas other low–income, working families that have never accessed CalWORKs are prioritized based on income. As a result, long waiting lists exist for non–CalWORKs families, with many eligible families never receiving care. Moreover, some former CalWORKs families that now effectively are guaranteed child care benefits for as long as they remain under the income cap and their children remain under the age cap have higher incomes than other eligible, low–income families that never receive even a single year’s worth of child care benefits.

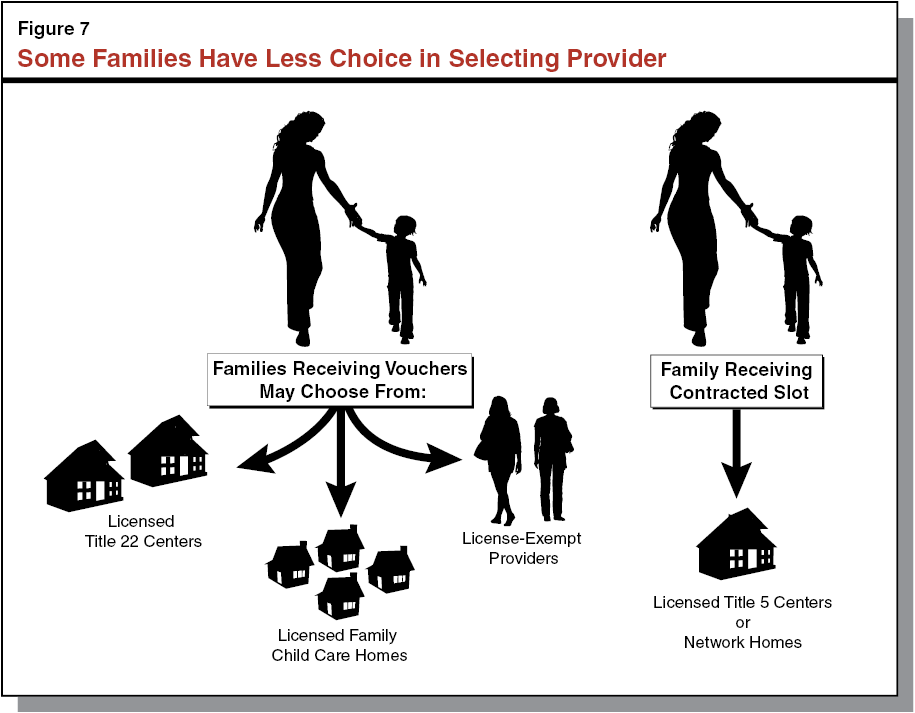

- Similar Families Have Different Amount of Choice in Selecting Care. CalWORKs families (and some other non–CalWORKs families receiving vouchers) can choose from a variety of providers—selecting care that best fits their needs. Other non–CalWORKs families, however, can only access child care at specific locations that contract directly with the California Department of Education (CDE).

- Similar Families Provided Different Standards of Care. The standard of care also varies based upon the type of subsidy a family receives. Those families receiving vouchers generally have access to providers that meet only health and safety standards, whereas those families receiving direct–contracted services have access to providers that meet health, safety, and developmental standards.

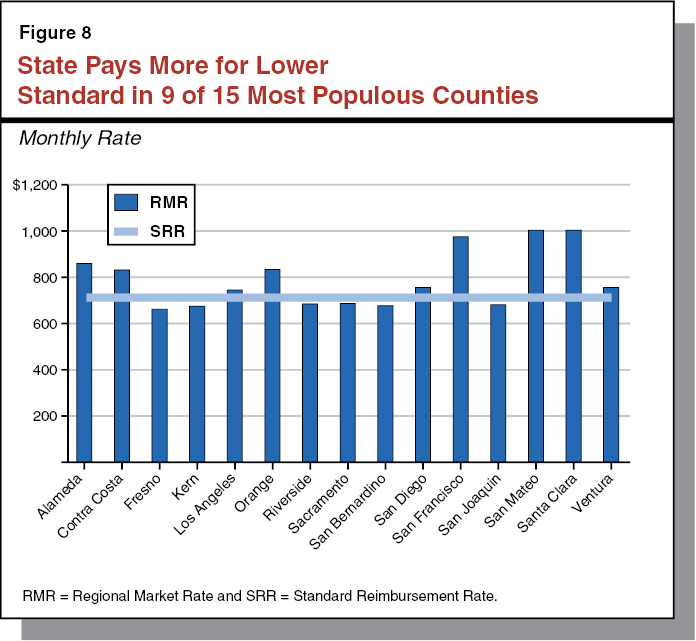

- State Has Higher Reimbursement Rate for Lower Standard of Care. In 19 counties, the state pays more to providers that are subject only to health and safety standards than to providers subject to health, safety, and developmental standards.

Recommend Restructuring System

Child Care and Development System in Need of Comprehensive Restructuring. Given these serious problems with the current child care and development system, we recommend the Legislature fundamentally restructure the system. We lay out a plan for a new, simplified, and rational system. Overall, the restructured system could be implemented with little, if any, additional cost. The new system would:

- Provide Similar Levels of Access to Most Low–Income Families. We recommend the Legislature continue to prioritize families new to CalWORKs for child care subsidies, as these families are likely to be among the most vulnerable families eligible for care. In order to provide greater access to eligible families, however, we recommend setting time limits on subsidized child care for all families. Providing eligible families six to eight years of child care would give them time to become more economically stable, while expanding services to approximately 35,000 additional families.

- Provide Similar Levels of Choice. We recommend the Legislature provide all eligible families similar levels of choice by providing subsidies primarily through vouchers. As a result, families currently limited to care in specific locations could choose the provider that best fits their needs. (Because of the manner in which local educational agencies [LEAs] generally are funded and the benefits of connecting families to the broader K–12 system, we recommend the Legislature make an exception to the voucher–based system and continue to have CDE contract directly with LEAs for preschool.)

- Require Developmentally Appropriate Care for Children Birth Through Age Four. We recommend requiring all child care providers serving children birth through age four to provide developmentally appropriate care. We recommend the Legislature direct CDE to develop standards that are similar to existing requirements for direct–contracted programs but modified to reduce some programmatic and administrative burden. In addition, we recommend the Legislature direct CDE to develop a monitoring system to ensure programs meet the new standards. Lastly, we recommend the Legislature update reimbursement rates to reflect the new standards.

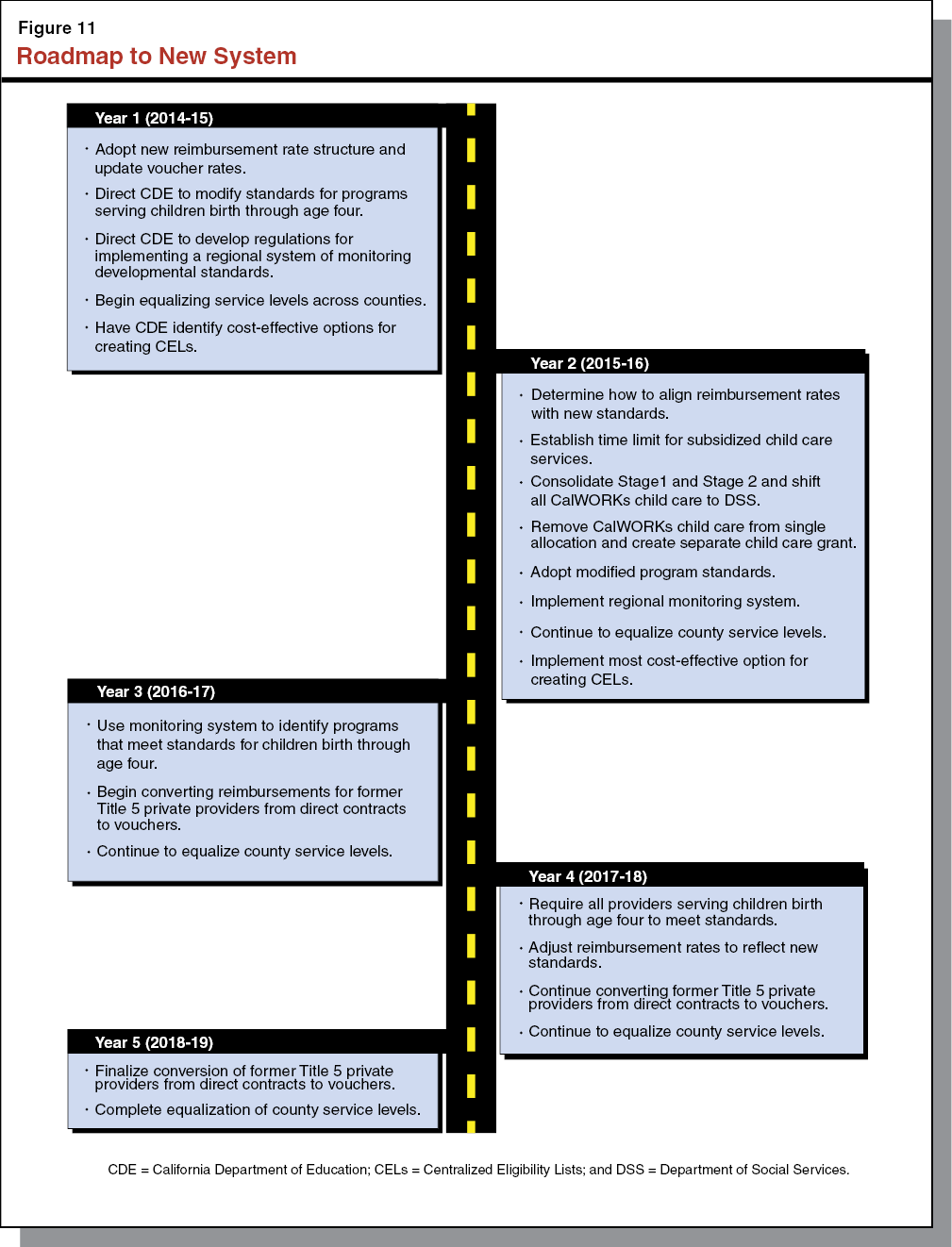

Roadmap to New System. Since a fundamental restructuring would require significant changes, we provide the Legislature a roadmap by which it could consider incrementally moving to this new system. In the first year, we recommend the Legislature update the reimbursement rates based on current data and determine the time limit for services. In the second year, we recommend the Legislature adopt new standards for programs serving children birth through age four, but wait until year four to require all providers to meet the new standards. In year four, we recommend the Legislature align the reimbursement rates to ensure families have access to providers meeting the new standards. By year five, families would access subsidized child care through vouchers, with the exception of LEA preschool programs. The five–year roadmap assumes no additional resources are provided for the restructured system. If the Legislature appropriated additional resources, it could implement certain components of the new system more quickly.

This report provides a comprehensive overview and assessment of the state’s child care and development system. The first part of the report contains background on California’s child care programs. The second part compares California’s child care and development system with other states’ systems. The third section identifies several major shortcomings of California’s system. Given the serious flaws of California’s existing system, the fourth section sets forth a package of recommendations for restructuring it, and the final section provides a roadmap showing how the Legislature might transition to the restructured system.

The child care and development system in California is a complex—and in many ways confusing—patchwork of providers and policies. The piecemeal evolution of the system is summarized in Figure 1. Below, we provide an overview of the state’s existing child care and development system—focusing on eligibility criteria, access to care, programs, funding, administration, and oversight.

Figure 1

System Developed Incrementally Over Time

|

1940

|

Congress enacts the Lanham Act. Provides federal funding for child care centers to promote female participation in the workforce.

|

|

1947

|

Legislature backfills loss of federal funding after the war ends and maintains child care centers with state funding. Targets services to low–income, working families.

|

|

1965

|

Legislature establishes State Preschool modeled after the Federal Head Start program and targeted to low–income children.

|

|

1976

|

Legislature creates the Alternative Payment (AP) Program using state funds. The AP Program provides families vouchers for child care and reimburses providers at lower rates than school districts. Standards for providers also are lower. (Prior to 1976, the majority of child care programs were operated by school districts.)

|

|

1978

|

Proposition 13 eliminates school districts’ ability to levy additional property taxes to support child care programs. Legislature backfills school districts’ lost child care revenue, increasing the state’s investment in these programs significantly.

|

|

1980

|

Legislature directs the Superintendent of Public Instruction to develop a “standard reimbursement rate” (SRR). The SRR is intended to serve as a target reimbursement rate for school district programs (as existing district rates varied significantly).

|

|

1997

|

CalWORKs provides all welfare–to–work participants access to child care vouchers.

|

Eligibility and Access

Subsidized Child Care Generally Designed for Low–Income, Working Families. Subsidized child care programs are intended to serve two primary purposes: (1) enable low–income families to work and (2) improve low–income children’s cognitive and educational development. California provides child care subsidies to some low–income families, including those families participating in CalWORKs as well as other low–income families who have never participated in CalWORKs. Families generally must meet the following three criteria to be considered eligible for child care subsidies.

- Parents must be working or participating in an education or training program—that is, the family must demonstrate “need” for care. (Families may receive subsidized child care only for the hours the parents are working.)

- A family’s income must be below 70 percent of SMI as calculated in 2007–08. (For a family of three—either two parents and one child or one parent and two children—the SMI cap the state currently uses is $42,216.)

- Children must be under the age of 13.

Eligibility for Migrant and Handicapped Child Care Programs. The state also subsidizes care for two specific populations—children of migrant workers and children with severe handicaps. For migrant child care, families must meet all the criteria specified above as well as earn at least 50 percent of their gross income through agricultural work. To be eligible for subsidies through the handicapped child care program, a child must have a physical, mental, or emotional handicap of such severity that he or she cannot be served adequately or appropriately in a regular child care program (as determined by the individualized education program designed by a special education team). Children participating in the handicapped program may remain in the program until 21 years of age. The handicapped child care program is only available in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Families Learn of Available Child Care in Various Ways. Those CalWORKs families participating in training or seeking employment typically become aware of child care subsidies through county welfare departments (CWDs) or the Alternative Payment (AP) agencies that CWDs use to help them administer CalWORKs child care. (Thirty eight CWDs contract with AP agencies to inform families of child care options and provide various related services.) Non–CalWORKs families—families who are low–income but have never participated in CalWORKs—have no single means of connecting to subsidized care. These families may learn about subsidies from friends or family, through outreach and advertising, or through visiting a resource and referral agency. These agencies are nonprofit entities supported by state funding that provide information about child care options in their counties. (Resource and referral agency services are available to all families, regardless of whether they receive subsidies.)

Only CalWORKs Families Are Guaranteed Subsidized Care. CalWORKs families are statutorily guaranteed child care subsidies during “Stage 1” and “Stage 2” of the program. Families are considered to be in Stage 1 when they first enter CalWORKs and connect to CWDs’ services. Once CalWORKs families become stable (as defined by the county), they move into Stage 2. Families move into “Stage 3” two years after they stop receiving cash aid. Families in CalWORKs Stage 3 are not statutorily guaranteed child care subsidies, but the Legislature in practice has funded all eligible families. Families remain in Stage 3 until their income exceeds 70 percent of SMI or their child ages out of the program.

Non–CalWORKs Families Prioritized Based on Income Level. Given funding is sufficient to subsidize only a portion of eligible non–CalWORKs families, the state prioritizes these families based on income. Those families with the lowest income are prioritized over those families with relatively higher incomes.

Waiting Lists Common for Non–CalWORKs Programs. Those eligible non–CalWORKs families that do not receive subsidies may be put on waiting lists. Families can remain on waiting lists for years and may never receive a subsidized child care slot. From 2005 to 2010, the state funded all counties to maintain Centralized Eligibility Lists (CELs). Each county’s CEL consolidated the waiting lists for all non–CalWORKs programs within the county. The consolidated waiting list enabled providers to connect families more easily to available subsidies, since once a family signed up for one program’s waiting list, the family was automatically on the waiting list for all of the programs in the county. State support for counties’ CELs was eliminated during the recession. Some counties, however, continue to maintain their own CELs using local resources.

Families May Continue Receiving Subsidies Until They Income Out or Children Age Out. Once a CalWORKs or non–CalWORKs family accesses a subsidy, the family may continue receiving the subsidy as long as it continues to meet the program’s eligibility criteria. Some families that access the system stop receiving benefits only after their youngest child turns 13 years of age. (Data do not exist on the average number of years families in the system receive subsidies.)

Programs

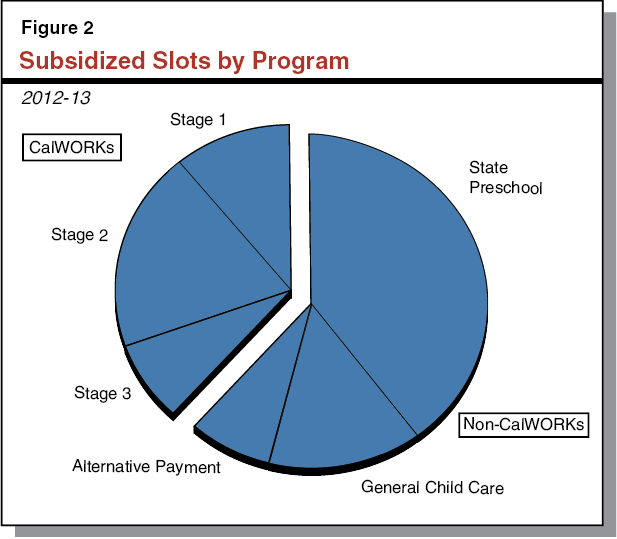

The state offers a variety of programs through which families may access child care. Families participating in CalWORKs receive subsidies through the three stages of the CalWORKs child care program. Non–CalWORKs families participate in the AP Program, General Child Care, or State Preschool. Across all of these programs, the state subsidized about 325,000 low–income children in 2012–13. Figure 2 shows the share of subsidized child care slots by program. Non–CalWORKs programs comprised 62 percent of all slots whereas CalWORKs child care comprised 38 percent of all slots. The single largest program is State Preschool (with 40 percent of all slots), followed by CalWORKs Stage 2 (with 20 percent of all slots).

Age of Children Served Varies Somewhat by Program. In 2012–13, 25 percent of children served in the state’s subsidized child care system were infants and toddlers (birth through age three), 34 percent were preschool–aged children, and 41 percent were school–aged children. The General Child Care program serves the highest share of infants and toddlers (34 percent of its slots served this age group in 2012–13), followed by the CalWORKs Stage 2 and the AP programs (at 19 percent and 18 percent of their slots, respectively). By comparison, CalWORKs Stage 3 serves the highest share of school–aged children (more than two of every three Stage 3 slots served school–aged children in 2012–13). Excluding State Preschool, which targets enrollment to four–year–olds, 55 percent of children served in all other programs were school–aged.

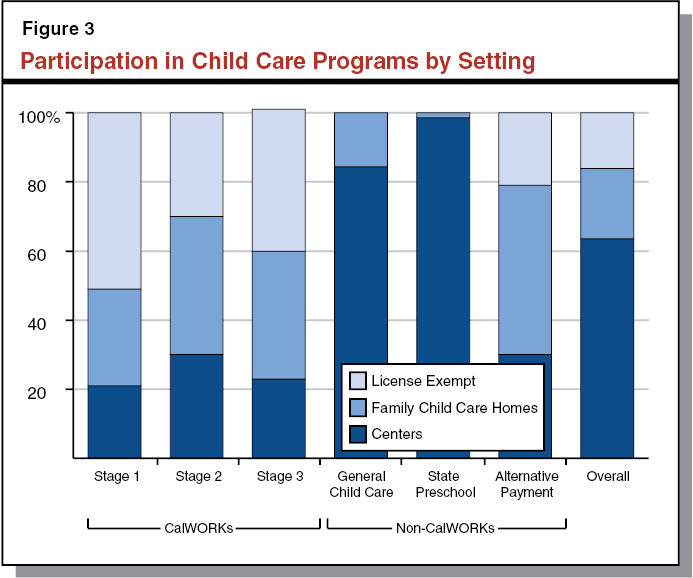

Children Receive Care in a Variety of Settings. Families participating in CalWORKs child care programs or non–CalWORKs families participating in the AP Program can choose from three types of child care settings: licensed centers, licensed family child care homes (FCCHs), and license–exempt care. Centers typically are run by community–based organizations or LEAs and often serve more children than other types of providers. The FCCHs operate from the provider’s home, with each home typically serving 6 to 12 children. License–exempt care is provided by an individual of the family’s choosing—typically a relative, friend, or neighbor who provides care in a private home. All non–CalWORKs families participating in the General Child Care program are served in centers or in FCCHs associated with a center (referred to as child care network homes).

Reliance on Particular Child Care Settings Differs Across Programs. Looking across all child care programs, the vast majority of children are served in licensed settings—64 percent of children are served in centers and 20 percent of children are served in FCCHs (see Figure 3). License–exempt care is most common among CalWORKs families. Whereas more than one–third of CalWORKs slots rely on license–exempt care, about one–fifth of non–CalWORKs AP slots rely on license–exempt care. (The General Child Care and State Preschool programs do not allow for license–exempt care.)

Special Rules for State Preschool. State Preschool has a few unique features compared to other child care programs. One unique feature is that State Preschool prioritizes four–year–olds for enrollment (but may serve three–year olds if space remains after enrolling all eligible four–year–olds). State Preschool also may serve some families that have incomes up to 15 percent above the eligibility threshold. In addition, families do not have to be working to enroll their child in a part–day preschool program. State Preschool can be offered at a child care center, a family child care network home, a school district, or a county office of education (COE). Today, 324 LEAs provide preschool programs serving approximately two–thirds of all children enrolled in State Preschool. While not all school districts offer State Preschool, most school districts offer transitional kindergarten (TK) to some four–year–olds (described in the nearby box).

Transitional Kindergarten

State Recently Created New Program for Four–Year–Olds. Chapter 705, Statutes of 2010 (SB 1381, Simitian), changed the eligibility for kindergarten and established a new “transitional kindergarten” (TK) program. Previously, children who turned five before December 2 were eligible for kindergarten. Under the new criteria, children must turn five before September 2 to be allowed to enroll in kindergarten. Consequently, the new TK program was created to serve those children turning five between September 2 and December 2 who would no longer be eligible for kindergarten. The kindergarten eligibility change and TK program took effect in 2012–13. In the first year, only children turning five in November were eligible for TK. In the subsequent year, both October and November birthdays were eligible for the program. In 2014–15, all children turning five between September 2 and December 2 will be eligible for the program.

TK Differs From State Preschool in a Few Key Ways. The TK program and State Preschool have a few notable differences. Regarding eligibility, State Preschool targets four–year–olds born in any month of the year whereas TK is only available for four–year–olds born within the last quarter of the calendar year. In addition, State Preschool serves low–income children whereas TK serves children regardless of family income. Regarding curriculum, TK programs must use a “modified kindergarten curriculum” that is age and developmentally appropriate. State Preschool programs also use a curriculum that is age and developmentally appropriate, but providers typically base their programs on the state’s preschool learning foundations rather than its kindergarten standards. Regarding types of providers, all TK programs are operated by school districts. (Most school districts, however, currently offer TK at only a few school sites.) By comparison, State Preschool is offered by some school districts and some private providers. (Private providers are not eligible to run state–funded TK programs.)

State Sets Different Standards for Different Providers. Figure 4 identifies the child care standards that apply to different providers. License–exempt providers must have a criminal background check and self–certify that they meet certain health and safety standards required by Community Care Licensing (CCL). Families using licensed centers and FCCHs (in any of the various child care programs) are guaranteed child care that meets CCL health and safety standards known as Title 22 standards. General Child Care and State Preschool providers must meet Title 22 standards and include cognitive development and an educational component as part of their programs—commonly referred to as “learning foundations.” The learning foundations describe the skills that children of different ages should be able to exhibit. Programs using the foundations focus activities around supporting the development of these skills. The requirement that these programs include developmentally appropriate activities is a key difference from other programs. The state also requires teachers in these programs to have more training than teachers in other child care settings. Together, these requirements are commonly referred to as Title 5 standards. (If a provider must meet only Title 22 standards, we hereafter refer to it as a Title 22 provider. If a provider must meet both health and safety as well as educational standards, we hereafter refer to it as a Title 5 provider.)

Figure 4

Standards for Child Care Providers

Preschool–Age Childrena

|

|

License–Exempt

Providers

|

Title 22 FCCHs

|

Title 22 Centers

|

Title 5 Centersb

|

|

Staff Qualifications

|

None.

|

15 hours of health and safety training.

|

Child Development Associate Credential or 12 units in ECE/CD.c

|

Child Development Teacher Permit (24 units of ECE/CD plus 16 general education units).d

|

|

Staffing Ratios

|

None.

|

1:6 adult–child ratio.

|

1:12 teacher–child ratio or 1 teacher and 1 aide per 15 children.

|

1:24 teacher–child and 1:8 adult–child ratio.

|

|

Health and Safety Standards

|

Criminal background check. Self–certification of certain health and safety standards.

|

Staff and volunteers are finger printed. Subject to health and safety standards.

|

Same as Title 22 FCCHs.

|

Same as Title 22 FCCHs.

|

|

Content Standards

|

None.

|

None.

|

None.

|

Requires developmentally appropriate activities.

|

|

Monitoring

|

None.

|

Unannounced visits by CCL every five years or more frequently under special circumstances.

|

Same as Title 22 FCCHs.

|

Same as Title 22 FCCHs, but also onsite reviews by CDE every three years (or as resources allow) and annual outcome reports.

|

|

Applicable Programs

|

CalWORKs, AP Program

|

CalWORKs, AP Program

|

CalWORKs, AP Program

|

General Child Care, Migrant Child Care, State Preschool

|

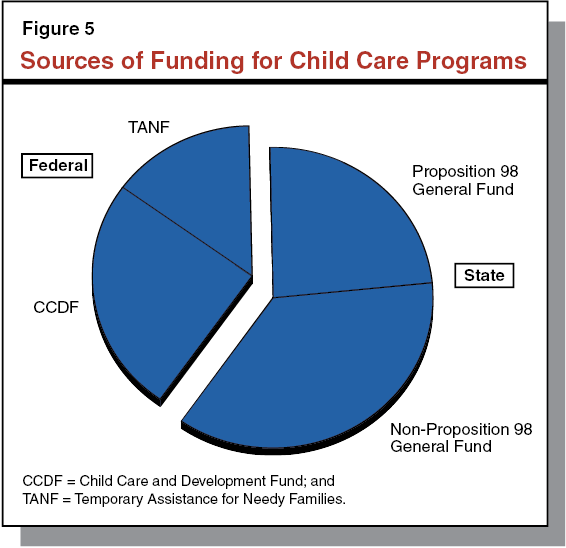

Funding

State Makes Significant Investment in Subsidized Care. Figure 5 displays the sources of funding for child care and development programs. In 2013–14, California dedicated $2.1 billion to these programs. State funding—non–Proposition 98 and Proposition 98 General Fund combined—made up approximately 60 percent of total funding, while federal funding made up approximately 40 percent. Federal support is provided through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Whereas TANF predominately supports CalWORKs Stage 1 child care, the CCDF is blended with state funding to support child care programs generally. (One condition of receiving the CCDF is that a state dedicate some child care spending—currently approximately $70 million for California—to activities intended to improve the quality of child care programs.)

State Pays for Services Through Contracts and Vouchers. The state provides child care subsidies through a combination of contracts (with particular providers) and vouchers (that families can use for almost any provider).

- Contracts. The CDE contracts directly with providers that meet Title 5 standards. These providers are reimbursed based on the number of children served (up to a specified total cost). In 2012–13, 54 percent of all child care slots were reimbursed through direct contracts.

- Vouchers. Providers serving families participating in CalWORKs child care and the AP Program are paid using vouchers. The AP agencies determine which families are eligible to receive vouchers. Once a family is determined as eligible for a voucher, the AP agency works with the family to connect them to child care. The AP agency then reimburses the child care provider directly for the hours of eligible care used by the family. In 2012–13, 46 percent of all child care slots were provided through vouchers.

Reimbursement Rate Structures Vary for Contracts and Vouchers. Providers required to meet Title 5 standards are paid a Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR) that is set in Education Code and in the annual budget act. The SRR is higher for Title 5 centers than Title 5 FCCHs. The SRR also is adjusted to account for various characteristics of the child served—including age, being limited English proficient, or having a disability. In contrast, reimbursements for providers meeting Title 22 standards vary based on the county in which the child is served. These reimbursement rates are referred to as Regional Market Rates (RMRs) and are based on regional market surveys of private providers. Currently, the state sets the RMR at the 85th percentile of a 2005 regional market survey. (Though the state has conducted more recent surveys, as required by federal regulations, it has chosen not to set rates based upon them.) The percentile at which the state sets the RMR effectively reflects the purchasing power, amount of choice, and quality associated with a voucher. At the 50th percentile, for example, a voucher would allow a low–income family to select among the less–expensive half of all providers. Like the SRR, the RMR also is adjusted based on the age of the child and if the child has a disability. The SRR and the statewide average RMR for full–day care of a preschool–age child is $716 per month and $714 per month, respectively.

Different Reimbursement Rules Used for License–Exempt Providers. The state reimburses license–exempt providers at a percentage of their county’s maximum RMR or their actual costs, whichever is lower. Currently, the reimbursement rate for license–exempt providers is set at 60 percent of each county’s maximum RMR.

Actual Reimbursements Vary Based on What Provider Charges. Reimbursements for Title 22 providers also vary based upon what they actually charge. If a Title 22 licensed center or FCCH charges less than the county’s RMR, then the voucher covers the cost of care. If a family selects a provider that charges above the RMR for the county, the family must pay the difference between the value of the voucher and what the provider charges. To prevent providers from shifting any cost above the RMR to other families, the state requires that providers charge subsidized families and non–subsidized families the same price.

State Requires Contribution From Families Too. Families not receiving CalWORKs cash assistance must pay fees for child care, requiring families to make an investment in the services provided. Fees are based on family size, income, and whether the family receives part–day or full–day care. (Full–day care is defined as six or more hours of care.) For instance, a family of three making approximately $2,000 per month is required to pay $2.50 per day for full–day care and $1.25 per day for part–day care (regardless of the number of children in care). Family fees increase as family income increases. All fees collected are used to offset the state General Fund cost of the programs. In 2012–13, the state collected approximately $54 million in fees across all child care programs.

Recent Recession Reduced Funding for Child Care. Between 2009–10 and 2011–12, significant budget shortfalls required the state to make reductions to a variety of state programs. Funding for child care programs was reduced by approximately $1 billion. The reduction was implemented through a combination of narrowing eligibility, reducing reimbursements for license–exempt providers, and serving fewer children. During this period, the state held the RMR and SRR at 2005 and 2007 levels, respectively. The nearby box describes some of the effects of these actions on the child care system.

Changes in the Child Care Landscape

Fewer Title 22 Providers, Higher Costs. There were 3,880 (or 10 percent) fewer Title 22 family child care homes and 312 (or 2 percent) fewer Title 22 child care centers operating in 2013 compared to 2008. (These figures reflect changes in the total number of Title 22 licenses statewide, not only those serving subsidized families.) Partly due to this reduction in child care capacity and partly a result of the state not updating reimbursement rates as child care costs increased, the percentage of Title 22 providers charging at or above the maximum regional market rate (RMR) increased in almost all counties over the past six years. That is, the relative value of vouchers diminished significantly in almost all counties. Comparing the current RMR for preschool–age children served in centers to the 2012 RMR survey reveals that vouchers cover the full cost of care for less than 50 percent of providers in seven counties. In 22 other counties, the current preschool RMR for centers provides access to between 50 percent and 70 percent of providers.

Fewer Title 5 Providers. Based on data provided by the California Department of Education (CDE), 224 Title 5 providers (or approximately 16 percent) declined to renew their contracts during the recession. (This figure does not include contracts terminated by CDE due to fiscal or programmatic noncompliance.) While the reimbursement rate may not have been the deciding factor in all contract terminations, CDE indicates providers typically terminate contracts due to insufficient funding. When a provider declines to renew its contract with CDE, the department tries to find another provider to take on the additional child care slots. In some cases, providers within the same community are able to provide the additional slots. In other cases, CDE cannot find a provider in the same community to take on the contract, and CDE ends up contracting with a provider in a different area to provide the slots. As a result, the availability of subsidized child care in particular communities changes.

Administration and Oversight

Two State Departments Administer the Programs. The CalWORKs program is administered at the state level by the Department of Social Services (DSS). For CalWORKs, DSS provides CWDs a “single allocation” of funding. Funding for Stage 1 child care is part of the single allocation. The CWDs may use their single allocations for any combination of subsidized child care and welfare–to–work services. Funding for families in Stage 2 and Stage 3 is provided through CDE. All non–CalWORKs child care programs also are administered by CDE.

Program Monitoring Varies by Provider Type. All centers and FCCHs must have a license to operate (a license ensures providers meet Title 22 standards). The CCL—part of DSS—processes applications for child care licenses, inspects applicants, and periodically monitors those who have been granted a license. Licensing visits typically happen once every five years. Title 5 providers are monitored by CCL for health and safety standards but they also are monitored by CDE for meeting developmental standards. Typically, Title 5 providers receive monitoring visits every three years, but CDE recently began using a risk–review process that targets monitoring visits to those providers at higher risk of not meeting requirements. As a result, some providers are visited more frequently than every three years, while others are visited less frequently. License–exempt providers are not actively monitored by a state agency.

State Collects Some Information on Children Served. In general, CDE collects descriptive information about the families served in subsidized child care programs. Specifically, CDE collects data on the age of the children served, the setting in which the child is served (licensed or licensed–exempt), and whether the care is full day or part day. In addition, CDE collects data on the income level of families receiving subsidized care and the program through which they receive subsidies. By comparison, DSS only collects information on the type of setting in which CalWORKs families receive Stage 1 child care services.

In this section, we compare California’s child care and development system to other state’s systems, focusing primarily on income eligibility, prioritization of low–income families, duration of benefits, standards of care, and reimbursement structures.

All States Have Subsidized Child Care for Low–Income Families. All states receive a minimum level of federal funding for subsidized child care. If states contribute matching funds, they receive additional federal funds. Together, these federal funds are known as the CCDF. In addition, federal TANF regulations allow for up to 30 percent of the TANF grant to be transferred to CCDF to augment child care services for a broader low–income population. Using some combination of these federal funds, all states offer some amount of subsidized child care.

California’s Income–Eligibility Threshold Is Relatively High. Federal regulations set the maximum income–eligibility level at 85 percent of SMI but allow states to set lower thresholds. (Rather than using SMI, some states use the federal poverty level [FPL] as an alternate way to set income eligibility.) The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services collects data on states’ eligibility thresholds relative to the FPL. The majority of states (31) set their eligibility threshold at or below 200 percent of the FPL (approximately $39,000 for a family of three) and the remaining 19 states set their eligibility threshold somewhere between 200 percent and 250 percent of the FPL. The lowest eligibility threshold is in Nebraska (at 120 percent of the FPL) and the highest eligibility threshold is in New Hampshire (at 250 percent of the FPL). By comparison, California’s current eligibility threshold equates to 228 percent of the FPL.

California Among Group of States Prioritizing Child Care Subsidies for Welfare–to–Work Families. Similar to states’ latitude in setting their income–eligibility thresholds, federal regulations governing CCDF allow flexibility in how states prioritize families. Federal CCDF regulations require that children with special needs and children in very low–income families be prioritized; however, states have discretion as to how to define these characteristics. As described below, given the significant level of discretion allowed under federal regulations, states vary in how they prioritize families’ access to subsidized care.

- Twenty Two States, Including California, Guarantee Child Care Subsidies for Welfare–to–Work Families. In these states, families participating in TANF receive top priority for subsidized care.

- Nineteen States, Including California, Guarantee Services to Families Transitioning Off of Welfare. Fourteen of the states that guarantee subsidized child care to families participating in welfare–to–work activities (including California) also guarantee subsidies to families who recently went off cash assistance. Five other states guarantee subsidized child care for families transitioning off of TANF (but do not guarantee those families subsidized child care when participating in TANF).

- Other States Prioritize in Various Ways. For the rest of states, policies on how to prioritize families vary. Some states do not guarantee any family access to subsidized child care but still give TANF families priority over other low–income families. Other states do not prioritize welfare–to–work families but instead give low–income families subsidized slots essentially on a first–come, first–served basis.

Duration of Benefits in California Probably Longer Than Many States. While most states do not have explicit time limits for child care, often states limit eligibility to those participating in TANF. That is, once families either exhaust the time allowance for job search or the time limit for cash aid, families lose eligibility for subsidized child care. As a result, the time limits associated with states’ TANF programs also act as time limits for subsidized child care. By comparison, California guarantees subsidized child care benefits for former welfare recipients for as long as they meet work and income requirements and have children younger than age 13. Once a low–income, non–welfare recipient in California receives subsidized child care, he or she also continues to receive benefits as long as all other requirements are met. (With the exception of Oregon, all states set the child care age cap at 13. Oregon discontinues child care benefits at age 12.)

California’s Standards Relatively High. Federal regulations require that states set licensing standards for child care providers in the areas of health and safety. Twenty–one states, including California, exceed federal regulations in these areas. Some states, including California, not only have stricter health and safety standards but also exceed federal regulations by requiring providers to have training in child development. (The amount of required child development training varies across these states.) In an effort to promote high child development standards, some states use a Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) to identify providers that meet certain standards. California does not use a QRIS; yet, even compared to those states using quality rating systems, its Title 5 standards for developmentally appropriate care are relatively high.

California’s Reimbursement System Unique Among the States. The majority of states use vouchers as the primary means of providing subsidized child care. By comparison, California uses both vouchers and direct contracts with child care providers. California is one of only a few states that directly contracts with child care providers. Moreover, among the states that use direct contracts with providers, California uses contracts for a relatively large share of subsidized child care. Given these differences, California’s child care system is more centralized than other states.

Overall, California’s child care system has two components that we believe are core strengths. One strength relates to choice whereas the other relates to high standards. Regarding choice, families accessing some subsidized child care programs may choose among a broad array of providers, thereby increasing the likelihood they can find a provider that meets their needs. Regarding standards, families in some subsidized child care programs have access to developmentally appropriate care. Though these two strengths exist, the fundamental shortcoming of California’s current system is that no subsidized program exhibits both of these strengths concurrently. This inconsistent treatment of families stems from four serious design flaws with the state’s current system. Figure 6 lists these design flaws as well as two other consequences resulting from them. We discuss each of these shortcomings further below.

Figure 6

Current System Treats Similar Families Differently

|

Design Flaws

|

- Similar families have different levels of access.

|

- Similar families have different amount of choice in selecting care.

|

- Similar families provided different standards of care.

|

- State has higher reimbursement rate for lower standard of care.

|

|

Other Consequences of Design Flaws

|

- Resources not always used most strategically.

|

- Levels of service vary across the state.

|

Similar Families Have Different Levels of Access. The prioritization of families in or formerly in CalWORKs over otherwise similar non–CalWORKs families results in different access to services without clear justification. In counties with waiting lists, some non–CalWORKs families never receive services, whereas current and former CalWORKs families are guaranteed services as long as they remain otherwise eligible. As a result, former CalWORKs families can receive more than 13 years of subsidized child care, whereas a similar low–income family might not receive even a single year of benefits. Moreover, some CalWORKs and non–CalWORKs families have similar incomes, particularly when comparing Stage 3 families to non–CalWORKs families. The income distribution of these two groups of families is quite similar, with a slightly greater share of Stage 3 families having higher incomes than non–CalWORKs families.

Similar Families Have Different Amount of Choice in Selecting Care. As displayed in Figure 7, CalWORKs families (and other families receiving vouchers) can choose from a variety of providers. These families can choose among different care settings and locations—choosing child care that best fits their needs. By comparison, families receiving a contracted slot only have access to care at a specific location. The limited choice for families receiving a contracted slot can result in significant match issues. That is, the contracted slot may not match the parents’ needs because the location of the center is far from where the parents work and live, or the slot available does not fit with the hours of care the family requires. Due to challenges associated with matching parents’ needs to available contracted slots, some non–CalWORKs families are unable to take advantage of subsidized care when it becomes available. This issue is most prevalent for State Preschool programs, since the majority of programs only offer part–day care. For those families working full time, a part–day slot is insufficient.

Similar Families Provided Different Standards of Care. Families receiving subsidies can receive care meeting different standards. This is true between CalWORKs and non–CalWORKs families and across non–CalWORKs families. This is because the standard of care varies based upon the type of subsidy received. Those families receiving vouchers are guaranteed providers that meet only health and safety standards, while those families that access contracted slots receive care that meets health, safety, and developmental standards. (Care provided to families with vouchers can but is not required to have educational and developmental components.)

State Has Higher Reimbursement Rate for Lower Standard of Care. Figure 8 displays the RMR and SRR for preschool–age children in the 15 most populous counties. (As mentioned earlier, the RMR is used to pay Title 22 providers, which are subject only to health and safety standards, whereas the SRR is used to pay Title 5 providers, which are subject to health, safety, and developmental standards.) As shown in the figure, the RMR is higher than the SRR in over half of the 15 counties. Statewide, the RMR is higher than the SRR in 19 counties (for preschool–age children based on monthly reimbursements). In these cases, the state is paying a higher reimbursement rate for a lower standard of care.

Resources Not Always Used Most Strategically. The existing system does not target resources to low–income children to promote school readiness. While the state provides a significant number of slots for State Preschool, Title 5 programs (those program with an educational component) serve children of all ages, including school–age children who have access to the state’s After School Education and Safety (ASES) program as well as the federal 21st Century Program—both of which provide educationally focused wraparound care for low–income children. (In 2013–14, the state spent $550 million on ASES and $132 million on the 21st Century Program.) Given these other programs, additional resources are dedicated to children already receiving academic instruction in school rather than focusing those resources on low–income infants, toddlers, and preschool–age children. Moreover, TK eligibility is based on birth month, not income, such that middle– and high–income children born in the selected months receive preschool while low–income children born in other months do not have access to preschool. Moreover, the state pays a substantially higher rate—almost 50 percent more—for non–need based TK than need–based preschool.

Levels of Service Vary Across the State. Because data on the share of low–income children with working parents is not available, we cannot know how many children actually are eligible for subsidized child care. Data is available, however, on low–income children by county, which we compared with the total number of subsidized child care slots by county. Based on this measure, counties in the San Joaquin Valley and southern part of the state serve the lowest proportions of low–income children, with Kern County serving the smallest share. The highest share of children served is in Modoc County (with 30 percent of low–income children served). San Francisco County also serves a relatively high proportion of low–income children (27 percent). Despite this variation among counties, almost all counties in California serve a relatively small proportion of children, with 54 counties serving less than 20 percent of low–income children and 26 counties serving less than 10 percent of low–income children.

As discussed above, California’s child care and development system has several serious shortcomings. Similar families have different levels of access to programs that offer different choices among providers that meet different standards of care and, in turn, are reimbursed at different rates. In short, the system is complex, bifurcated, confusing, and inconsistent. We recommend undertaking a fundamental restructuring to create a simpler, more rational, and efficient system. Figure 9 summarizes our package of recommendations. Below, we discuss each of our recommendations in more detail. (In the subsequent section, we lay out a five–year roadmap for transitioning to the new system.)

Figure 9

Summary of Recommendations

|

Access

|

- Priority. Continue to give families new to CalWORKs priority for subsidized child care. Guaranteeing child care for these families helps overcome a key barrier to employment.

|

- Time Limit. Cap number of years families may receive subsidized child care. Set time limit between six and eight years. (Allows more low–income families to benefit.)

|

- Choice. Give families similar levels of choice in selecting care. Allow families to choose among licensed centers and family child care homes (FCCHs) as well as license–exempt providers.

|

- Service Levels. Provide similar levels of access across the state. Reestablish CELs.

|

|

Standards

|

- School Readiness for Four–Year–Olds. Require centers and FCCHs serving low–income four–year–olds to include educational components for three hours per day. Require families to opt–out of licensed care.

|

- Developmentally Appropriate Activities for Children Birth Through Age Three. Require centers and FCCHs serving children birth through age three to provide developmentally appropriate activities for three hours per day.

|

- Health and Safety for School–Age Children. Repeal Title 5 requirements for school–age children but retain Title 22 health and safety standards.

|

|

Payments

|

- Vouchers. Subsidize child care primarily using vouchers. Continue to contract directly with LEAs, however, for preschool.

|

- New Rate Structure. Rather than 58 unique county rates, provide three rates based on cost of care in low–, medium–, and high–cost counties. Use a standard reimbursement rate for LEAs.

|

- Rates by Age. Provide highest reimbursement rate for infants/toddlers, next highest rate for preschool–aged children, and lowest rate for school–aged children.

|

- Update Rates. Assuming total funding remains the same, new reimbursement rates would reflect 70th percentile of most recent (2012) regional market survey.

|

- Future Rate Adjustments. Update reimbursement rate in order to meet standards described above.

|

|

Administration

|

- CalWORKs. Merge CalWORKs child care Stage 1 and Stage 2 into one program and administration to the Department of Social Services.

|

- New CalWORKs Child Care Grant. Remove child care funding from counties’ single allocation and create new child care grant.

|

- Monitoring. Develop regional system to monitor programs serving children birth through age four.

|

Access

Continue to Prioritize Families New to CalWORKs. Though we believe a main goal of the restructured system should be to treat similar families similarly, we recommend the Legislature make an exception by giving families new to CalWORKs priority for child care subsidies (if they participate in welfare–to–work activities). Families new to CalWORKs are likely to be among the most vulnerable families eligible for subsidized child care in that they might recently have lost a job or otherwise be in the midst of a difficult transition. This does not necessarily apply to other low–income families. Guaranteeing these families subsidized child care can help them manage this transition and overcome a key barrier to employment. As work participation is a key component of the subsidized child care system, this benefit could be critical for helping these families reengage in the workforce.

Set Time Limits on Subsidies for All Families. We recommend the Legislature set a time limit of six to eight years for child care subsidies. Time limits would apply to both CalWORKs and non–CalWORKs families. (As noted earlier, most states do not have explicit time limits for child care, but effectively set time limits through TANF.) Providing eligible families six to eight years of child care would give them time to become more economically stable. In addition, after six to eight years of child care subsidies, many families’ children would be school age, at which time the children could access before and after school programs. Moreover, providing child care for six to eight years still represents a significant investment by the state—a total of at least $40,000 per child. Capping the number of years a particular family could receive care would allow the state to serve approximately 35,000 additional families (assuming total funding remained the same).

Give Families Similar Levels of Choice in Selecting Care. We recommend the Legislature provide all eligible families similar levels of choice by providing subsidies primarily through vouchers. Under this approach, rather than some families having to take whatever slot opens for them in General Child Care or State Preschool, these families would receive vouchers allowing them to choose the provider that best fits their needs. This would eliminate the “match” issue some families currently face in accessing care when and where they need it. This recommendation would provide greater choice for approximately 89,000 children (or 28 percent of all subsidized families). All children currently enrolled in General Child Care, as well as all children in State Preschool programs run by private providers, would be affected. The recommendation would affect approximately 280 private providers that currently contract directly with CDE for subsidized slots in the General Child Care and State Preschool programs. Under the recommendation, we believe many of these providers would shift to accepting voucher clients. Though accepting vouchers is a somewhat less predictable business model than direct contracting, all Title 22 providers have been operating under the voucher–based business model for decades.

Continue to Contract With LEAs for Preschool. As an exception to the voucher–based system, we recommend the Legislature continue to have CDE contract directly with LEAs for preschool. Collocating State Preschool programs with LEAs has advantages for transitioning children into kindergarten, leveraging LEAs’ resources (including counselors and nurses), and connecting low–income families to the educational system. Without direct contracts, LEAs, however, could be less likely to provide preschool programs because a voucher–based program would be substantially different from how they receive virtually all other funding.

Provide Similar Levels of Access Across the State. Given the variation in the proportion of eligible families served across the state, we recommend the Legislature equalize access across counties. The Legislature could consider addressing the differences across counties in one of two ways.

- Serve Same Share of Families in Each County. For instance, the Legislature could adjust funding levels to serve 10 percent of all eligible families in each county.

- Serve Families Based on Statewide Income Cut–Off. For instance, the Legislature could adjust funding levels to serve all families under 50 percent of SMI.

The first option accounts for regional differences in income and cost of care. Because average income levels are higher in some areas of the state, some counties would serve families closer to the income cap, yet these families still might struggle to cover the cost of child care in their county given it is more expensive than in other areas. For example, subsidies could reach families whose incomes were 50 percent of SMI in coastal counties but only 40 percent of SMI in inland counties. By comparison, the second option treats all families across the state similarly regardless of regional cost differences. Under the second option, those counties with a greater share of families at the bottom of the income distribution would see more families served than those counties with relatively higher–income families. We believe either option would be an improvement over the existing ad hoc service levels across counties.

Standards

Require Programs Serving Four–Year–Olds to Focus on School Readiness. We recommend requiring all centers and FCCHs serving low–income four–year–olds to include educational components. The state already makes significant investments in school readiness for four–year–olds through State Preschool and the existing TK program. Currently, not all four–year–olds in subsidized child care, however, have access to programs that are required to provide educational components. In creating the standards for these programs, we recommend the Legislature direct CDE to develop standards that are similar to existing Title 5 requirements but modified to reduce some programmatic restrictions and administrative burden. For instance, CDE could (1) relax some environmental requirements, such as classroom configuration; (2) provide some flexibility in teacher ratios; and (3) reduce some reporting requirements.

Could Redirect Funds to Support Educational Component of Care. While the state would not incur costs directly from requiring programs to meet higher standards (aside from monitoring, which we discuss later), some providers might want to make additional investments in curriculum and professional development. In addition, some existing Title 22 providers likely would have to enroll in additional training to meet the higher teacher qualifications (though some of these providers already might have the requisite education to meet higher standards). For instance, some Title 22 teachers likely would have to complete 12 additional early education units and 16 general education units (typically at a community college) to attain a Child Development Teacher Permit. Should the Legislature wish to provide support for these providers, it could redirect existing “quality” funding. (As noted earlier, a condition of CCDF is that the state must set aside approximately $70 million for improving child care quality.)

Require Programs Serving Children Birth Through Age Three to Include Developmentally Appropriate Activities. We recommend the Legislature require all centers and FCCHs serving children birth through age three to include some cognitive development to their care. Under the current system, only a small share of children in subsidized child care birth through age three may access programs that are required to include cognitive development. Growing research indicates that investing in developmentally appropriate care for children birth through age three can have significant impacts on social, emotional, motor, and cognitive skills, which, in turn, can result in low–income children being better prepared for school. As with our recommendation for standards for four year–olds, we recommend the Legislature direct CDE to develop standards for children birth through age three that are similar to current Title 5 standards but modified to reduce programmatic and administrative burden. As with programs for four–year–olds, requiring a developmental component in programs for children birth through age three likely would require some existing Title 22 providers to obtain additional training. This training also could be supported with redirected quality dollars.

Apply Developmental Standards to Part of the Day. We recommend the Legislature require programs serving children birth through age four to meet the new developmental standards for three hours per day. Requiring developmentally appropriate activities for a core portion of the day is consistent with the state’s current approach for State Preschool, TK, and kindergarten—all of which are part–day programs. For the other portion of the day, we recommend the Legislature require providers to meet only Title 22 health and safety standards. (Should the Legislature expand TK to all four–year–olds, we recommend only requiring a focus on cognitive development for children birth to age three.)

Balancing Developmentally Appropriate Care With Choice. The state has a long history of struggling to satisfy the two core goals of its subsidized child care system: (1) maximizing choice to ensure parents can find subsidized care during work hours while also (2) maximizing quality to ensure children are benefiting from their care. In an attempt to provide a reasonable balance of these sometimes competing policy objectives, we recommend the Legislature continue to allow families with children birth through age three to choose license–exempt care. For these youngest children, families may be more comfortable with a family or friend caretaker. Moreover, in some cases, these caretakers may provide care that is superior to care in centers and FCCHs (though the state currently does not assess whether care on average is better or worse in these settings). Once children reach four years old, the state has a greater interest in ensuring low–income children are prepared for school. The state, however, cannot readily ensure that developmentally appropriate activities are occurring for four–year–olds in license–exempt settings. Therefore, we recommend families be required to opt out of licensed settings for their four–year–olds. Families requiring full–day care still could choose license–exempt care for wraparound hours without going through an opt–out process. We recommend families wishing to opt out be required to provide a satisfactory reason for not enrolling their four–year–olds in preschool, with approvals granted if families make a solid case that the alternative care setting is higher quality or essential to maintain their jobs.

Effect of New Rules on Families Mixed. These new rules would affect families differently depending upon the subsidized child care programs they currently use. For those families currently receiving vouchers, these new rules could reduce the number of available providers (as some existing Title 22 providers might decide not to meet the new standards). Though availability for these families might be somewhat reduced, these families now would be provided care that includes developmentally appropriate activities (unlike in the current system). For those families currently receiving contracted slots, their choice of providers would increase substantially under the new rules (as these families no longer would be limited to taking whichever contracted slot might become available). Moreover, this latter group of families would see little, if any, change in the standard of care provided (as Title 5 already contains developmental standards).

Do Not Require Educational Component for Child Care Programs Serving School–Age Children. We recommend the Legislature repeal Title 5 requirements for school–age children. School–age children already receive several hours per day of instruction from certificated teachers. Moreover, the state and federal government already provide substantial resources to support “educationally enriching” after school care for low–income children. As noted earlier, excluding State Preschool, 55 percent of children in subsidized care are school age, including approximately 23,000 school–age children in General Child Care. Repealing the requirement to include educational components to care for these children would free up additional resources to support developmentally appropriate activities for children birth through age four.

Payments

Reimburse Vouchers Based on High–, Medium–, and Low–Cost Areas. As discussed earlier, we recommend offering families similar levels of choice among providers by paying for subsidized child care primarily through vouchers. As part of the new voucher–based system, we recommend the Legislature eliminate the current reimbursement rate structures and instead reimburse based on high–, medium–, and low–cost counties. Looking at the most recent RMR survey indicates that the differences across counties generally cluster into three groups. Urban and coastal counties tend to be the highest–cost counties with monthly preschool rates varying less than $20. The lowest–cost counties (which tend to be the rural northern and Central Valley counties) also have rates that vary less than $20 per month. The medium–cost counties (including San Bernardino and Sacramento) have somewhat more variation, with differences as great as $60 per month, but even this difference is relatively small on a percentage basis (8 percent of the average monthly rate in this set of counties). Relying only on high–, medium–, and low–cost rates would be a significant simplification of the current system, whereby each county has a different maximum reimbursement rate. Understanding the new system therefore would be much easier yet the rates would remain connected to the child care market and accurately reflect notable cost differences among counties.

Provide Higher Subsidy for Those Programs Required to Have Developmental Component. We recommend the Legislature set higher reimbursement rates for programs that meet the cognitive development and education standards developed by CDE for children birth through age four. Each high–, medium–, and low–cost county rate would reflect the higher standard for infants, toddlers, and preschool–aged children, with lower rates for school–aged children. For license–exempt providers, we recommend the Legislature continue to provide a notably lower rate (for example, 60 percent of the licensed rates), given underlying costs and requirements are notably lower. For LEAs, we recommend the Legislature continue to use a standard reimbursement rate, as LEAs receive a standard rate for virtually all other K–12 services they provide.

To Start, Set Reimbursements at the 70th Percentile of Most Recent Survey. As a first step in moving toward a new rate structure, we recommend the Legislature set the high–, medium–, and low–cost county reimbursement rates at a specified percentile of the 2012 RMR survey based on available funding. For instance, we estimate that setting the initial reimbursement rates at about the 70th percentile would allow the state to serve the same number of children without additional cost. (For each grouping of counties—high, medium, and low—the 70th percentile of the applicable counties could be averaged to set the corresponding rate.) Figure 10 shows what the rates would be under the simplified rate structure assuming the current funding level. (LEAs could be reimbursed at the average of the three county rates for preschool–aged children—$738 per month.) Setting the initial rates using the most recently available data helps lay a more appropriate foundation for the new rate structure.

Figure 10

A New, Greatly Simplified Rate Structure

|

|

2014–15 Ratea

|

|

High–Cost Counties

|

|

Infants

|

$1,342

|

|

Preschool

|

902

|

|

School–age

|

601

|

|

Medium–Cost Counties

|

|

Infants

|

$1,077

|

|

Preschool

|

719

|

|

School–age

|

479

|

|

Low–Cost Counties

|

|

Infants

|

$836

|

|

Preschool

|

594

|

|

School–age

|

396

|

Moving Forward, Align Rates With Standards. In the new system, we recommend the Legislature think differently about what the reimbursement rates represent. Under the current system, the state sets rates at a percentile of regional market prices to ensure families can access a certain quality of child care provider. Given the state does not directly measure the quality of these providers, the rate only indirectly reflects quality (presumably, the higher the percentile setting, the higher the quality). Under our suggested system, the state would directly address the quality issue by requiring all providers to offer developmentally appropriate care. The state would still need to ensure that the reimbursement rate was adequate enough that low–income families could access child care providers that meet the required standards without undue burden (for example, having to drive an excessive amount to find a qualified provider willing to accept their vouchers). The Legislature could consider various options to achieve this goal. For example, families receiving vouchers could be surveyed to determine whether they can find a qualified provider. The Legislature, in turn, could use this data to identify whether any access problems were emerging in the new system. Another option would be to narrow the regional market rate survey to providers meeting the new standards and select a rate deemed appropriate for ensuring a reasonable level of access among these providers. Once the reimbursement rate has been modified to reflect the standards of the restructured system, we recommend the Legislature continue to monitor whether families can access providers meeting the updated standards.

Administration

Merge CalWORKs Stage 1 and Stage 2 Into One Program and Shift All CalWORKs Administration to DSS. We recommend the Legislature consolidate CalWORKs Stage 1 and Stage 2 into a single program administered by DSS. The current distinction between the child care stages rests primarily upon the expected differences in families’ “stability”—those families in Stage 2 are expected to be more stable than those families in Stage 1. Distinguishing between families due to differences in stability, however, does not affect access to the program, as all active CalWORKs families as well as all families recently off CalWORKs cash aid are guaranteed subsidized care. Moreover, CDE’s current administration of CalWORKs Stage 2 does not affect the associated standard of care. Providers serving Stage 2 (or Stage 3) families are not required to participate in provider training administered by CDE, nor does CDE monitor these programs in such a way as to know how many children are in care with an educational focus. Consequently, having DSS administer CalWORKs child care would not inherently hamper providers’ quality. Given DSS administers all other aspects of the CalWORKs program (including employment services and cash aid), we recommend it administer the new consolidated CalWORKs child care program.

Create Separate Grant for CalWORKs Child Care. We recommend the Legislature remove child care funding from counties’ single allocation (such that the single allocation would fund primarily welfare–to–work activities) and create a separate CalWORKs child care grant. We recommend the Legislature allow some amount of transfer (for example, up to 10 percent) across the welfare–to–work and child care grants. This flexibility would allow CWDs to respond to changes in unanticipated increases in child care caseload or increases in demands for welfare–to–work services. Separating the grants, however, would make identifying CalWORKs child care funding much easier, as estimating the portion of the single allocation currently going for child care services is a challenge at the state level every year. Separating the welfare–to–work and child care grants, while also consolidating CalWORKs stages, also could help ensure eligible CalWORKs families can access subsidized care more quickly and easily, as all related funding would be combined into a larger child care pot. The amount of the new child care grant would be based on anticipated CalWORKs child care caseload—much as it is today—but would fund costs only for families first entering CalWORKs, those participating in welfare–to–work activities, those receiving cash aid, and those recently off cash aid.

Merge CalWORKs Stage 3 and Non–CalWORKs Child Care Programs. We recommend merging the child care program for current Stage 3 families (those that have been off CalWORKs cash aid for more than two years) with the non–CalWORKs program (for low–income families that have never accessed CalWORKs benefits). In the near term, no family currently in the system would be affected by this change. Moving forward, if the Legislature were to make changes to the non–CalWORKs child care program, these two groups of families would be affected similarly, without prioritization or special treatment of one group over the other. (Regardless of whether a family entered the subsidized child care system through CalWORKs or non–CalWORKs, it would continue to receive child care benefits until it reached the time limit—six to eight years.)

Have CDE Administer Merged Program. We recommend CDE administer the merged program, as it already administers both the Stage 3 and the non–CalWORKs programs. As part of its administration, CDE would continue to use AP agencies to provide vouchers to former Stage 3 and some non–CalWORKs families as well as begin converting contracts with existing Title 5 providers to vouchers for other non–CalWORKs families. Consequently, AP agencies would issue more vouchers compared to today. In addition, CDE would continue to contract with LEAs to provide preschool.

Establish Regional Monitoring System for Programs Serving Children Birth Through Age Four. We recommend the Legislature establish a regional monitoring system for programs serving children birth through age four. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature direct CDE to contract with regional nonprofit or public entities (such as AP agencies, resource and referral agencies, and COEs) to inspect and monitor centers and FCCHs to ensure they meet the required standards. Based on funding provided for similar monitoring systems within California, we believe the cost of the regional system would be in the low tens of millions of dollars. (These costs could be covered by redirecting remaining quality dollars or augmenting existing funding for AP agencies, resource and referral agencies, or COEs. Absent additional resources, any augmentations made to support the regional monitoring system would result in fewer children served.)

Direct CDE to Do Certain Inspections to Ensure Consistency. To ensure consistency across the state, we recommend directing CDE to do inspections of providers each year in different areas of the state. Inspections performed by CDE would be based on risk reviews of data collected from the regional monitoring agencies. For instance, if a particular monitoring agency certified a far greater share of providers than other monitoring agencies, CDE could randomly inspect a few providers in the agency’s area to ensure providers were meeting the standards. Resources currently used by CDE to oversee Title 5 providers could be redirected for these risk reviews and inspections. (Currently, CDE has approximately 20 staff assigned to monitoring Title 5 centers adherence with developmental standards.)

Reestablish CELs. In order to help families access care, equalize service levels across the state, and make corresponding funding adjustments, we recommend the Legislature reestablish consolidated waiting lists. We estimate restarting CELs would cost between $5 million and $10 million annually. (The previous contract for the CEL cost approximately $8 million annually.)

Figure 11 lays out a roadmap the Legislature could use to transition to the new system. The roadmap assumes the Legislature does not make substantial new investments. Without such investments, the roadmap assumes the transition would take five years. To the extent additional funding were provided, some elements of the timeline could be accelerated. For instance, if the Legislature provided funding for additional slots, consistent service levels across counties could be achieved more quickly. (Other elements of the restructuring, such as developing revised program standards and a regional monitoring system, would take a certain amount of time to implement regardless of available funding.) Below, we discuss the main milestones in the roadmap.

Time Limits Could Begin in the Second Year. In the first year of restructuring, we recommend the Legislature determine the time limit for child care subsidies. Setting the time limit at six years would reflect the maximum number of years CalWORKs families are currently statutorily guaranteed subsidized child care. Setting the time limit at eight years would extend beyond this guarantee and provide families additional time to become self–sufficient. Due to limited resources, however, for each additional year of subsidized care provided to one family, another family is unable to access care. Once a time limit is set, we recommend the Legislature implement the time limit in year two of the transition. For families already participating in subsidized child care programs, their time clock would start in year two and they would continue to receive services (if they remain otherwise eligible) until they reach the time limit. Any families new to subsidized child care would start their time clocks in the first year they receive services.

CalWORKs Changes Could Take Effect in the Second Year. Due to the administrative and budgeting changes associated with consolidating the CalWORKs stages and creating a new child care grant, we recommend the Legislature wait until year two of the transition to implement these changes. In year one of the transition, the Legislature could direct CDE and DSS to work together to determine how to forecast the caseload and funding for the new CalWORKs child care grant. In addition, CDE could determine how many CalWORKs Stage 3 families would require vouchers under the new system. In year two, CalWORKs Stages 1 and 2 could be consolidated and child care services could be funded through the new CalWORKs child care grant (administered by DSS). Stage 3 families would continue to receive vouchers administered by CDE until they reach the time limit. Their child care services, however, technically would not be considered part of the CalWORKs child care grant.

New Standards and Associated Monitoring System Could Be Phased In Over Four Years. To allow existing providers that do not meet the new child care standards time to gain the required training, we recommend the Legislature phase in the new standards over four years. In year one of the transition, the Legislature could direct CDE to adopt a new set of streamlined standards for programs serving children birth through age four. In year two, CDE could inform providers of the new standards and the Legislature could consider reallocating quality dollars to help providers both learn of and begin implementing the new standards. In year three, oversight agencies could begin monitoring providers to identify whether the new standards were met. In year four, only providers certified by the regional monitoring system as meeting the required standards would be allowed to receive subsidies for children ages birth through age four. (As these activities are occurring, providers serving school–aged children could be notified that they remain subject to health and safety standards but not additional developmental standards beyond what the children receive during the course of the regular school day.)

Voucher–Based System Could Be Phased In Over Five Years. We recommend the Legislature direct CDE to begin phasing out contracts with Title 5 private providers starting in year three of restructuring and completely transition to vouchers by year five. One option for phasing out Title 5 contracts would be for CDE to reduce contracts incrementally each year, giving Title 5 providers some financial stability as they become familiar with the voucher–based system. For each Title 5 slot reduced, CDE would increase the number of vouchers correspondingly. (This approach also could help CDE adjust service levels across the state.) After year five, CDE would only contract directly with LEAs to provide preschool.

Equalizing Service Levels Across Counties Also Likely to Take Five Years. We recommend the Legislature direct CDE to develop a proposal in the first year of restructuring for how to establish consistent levels of service across counties based on one of the two options outlined earlier in this report. In the second year of restructuring, we recommend the Legislature review CDE’s proposal, adopt a plan to adjust service levels, and direct CDE to implement it over the subsequent four years. Each year, CDE would redirect a portion of funding for vouchers across counties to meet the service–level goal. (As mentioned above, shifting from Title 5 contracts to vouchers could help CDE make these adjustments.) These funding shifts could happen incrementally over four years to minimize any disruption in services.