Background

State Traditionally Has Budgeted for Universities Based on Workload. Traditionally, the state has adjusted University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) funding to account for changes in enrollment and inflation—two basic workload adjustments. For enrollment, the state typically set an enrollment target and provided UC and CSU a specified funding rate (based on an estimated marginal cost) for each additional, authorized student. For inflation, the state provided base increases so the universities could cover increased costs for their existing operations. The state also typically funded a few cost increases separately (such as pension costs) and earmarked some state funding for targeted purposes (such as student outreach programs). For capital outlay, the state reviewed and approved specific projects and used state bond funds to pay for them. The state typically did not have a policy on student tuition levels and revenues, though tuition revenues are used along with state funds to support the universities’ core programs.

State Has Been Moving Away From Traditional Budgetary Approach. Beginning in 2008–09, the state started to move away from its traditional budgetary approach for the universities. The state budget no longer includes enrollment funding and base increases no longer are connected with inflation. The state budget also no longer earmarks as much funding for specific purposes. Though the state continues to fund capital outlay at CSU in the traditional manner, the Legislature no longer approves capital projects for UC as part of the regular budget process. In addition to these departures from the traditional budgetary approach, the state recently added some new elements to the budgetary process for the universities. Specifically, the state has begun requiring the universities to report on certain outcome measures, such as graduation rates. In addition, in 2013, the state adopted legislation specifying that student access, student success, state civic and workforce needs, and efficiency all should be taken into account when making higher education budget decisions.

Assessment

Mixed Review of Traditional Budgetary Approach. The state’s traditional budgetary approach connected funding with costs and allowed the state to ensure a certain level of student access. However, the state’s process for funding enrollment had several shortcomings in that the state set its enrollment targets based only on access to undergraduate education, without considering other related goals (such as meeting state workforce needs or providing a certain level of access to graduate education); the state set its enrollment targets after the universities had already made fall enrollment decisions; and the state did not provide incentives for the universities to become more efficient. The state’s lack of a tuition policy also resulted in volatility in student tuition, with steep tuition increases during fiscal downturns.

Also Mixed Review of New Budgetary Approach. The state’s more recent budgetary approach disconnects funding and costs. It also diminishes legislative oversight and decision making regarding capital outlay. At the same time, the more recent budgetary approach includes an emphasis on a broader set of state priorities (including student success), though it does not specify how these priorities are to be factored into budgetary decision making.

Recommendations

Recommend Legislature Refine Traditional Approach. Because it connects funding and costs and ensures a certain level of student access, we recommend the Legislature return to using its traditional approach to funding the universities but make some refinements. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature authorize an updated eligibility study (such a study has not been conducted in over six years), set different targets for different groups of students (the universities are to report the cost of educating undergraduate and graduate students separately beginning October 2014), and set enrollment targets for one year out to better influence university enrollment decisions. In addition, we recommend the Legislature adopt a share of cost policy for student tuition to reduce volatility in tuition levels.

Recommend Legislature Use Performance Metrics as Part of Budget Decisions. In conjunction with refining its traditional budgetary approach, we recommend the Legislature use the universities’ required reports on outcome measures to inform its budget decisions. To this end, we recommend the Legislature require UC and CSU to report on their performance measures at budget hearings each spring, so the Legislature can learn more about each university’s performance and develop expectations for performance moving forward. We recommend the Legislature work with the universities during subsequent budget hearings later in the spring to (1) identify the reasons why the universities are or are not meeting state expectations and (2) redirect state resources accordingly.

Traditionally, one of the main ways California has budgeted for UC and CSU is through enrollment funding. In recent years, however, the state has not taken a consistent approach to funding enrollment at the universities. For this reason, the Legislature adopted language in the Supplemental Report of the 2013–14 Budget Package directing our office to review the state’s enrollment funding practices. Because the state in recent years has departed from its traditional budgetary approach in numerous other ways, such as by incorporating specific performance measures, we took a broader look at all state funding practices for the universities as part of our review.

In this report, we first describe the state’s traditional approach to funding UC and CSU and then discuss the state’s recent departures from this approach. Next, we assess the relative merits of the state’s traditional budgetary approach versus its more recent approach. Based on this assessment, we make several recommendations regarding how to budget for the universities moving forward. These recommendations are intended to serve as guiding principles for the Legislature to consider. (In the next few days we will publish a report as part of our 2014–15 budget analysis series that uses these guiding principles to make specific recommendations on the Governor’s 2014–15 budget proposals for UC and CSU.)

This section describes the way the state historically has funded UC and CSU. It then describes how the state has moved away from its traditional funding approach in recent years, particularly as part of the 2013–14 budget.

Traditional Approach to Funding UC and CSU

Budgetary Approach for Universities Has Been Similar to Approach Used for Other State Agencies. Historically, the state has used an incremental budgetary approach to fund nearly all state agencies, including UC and CSU. Under this approach, the state annually adjusts each agency’s existing base budget to account for changes in workload—consisting mainly of changes in the number of individuals receiving services from the agency (often referred to as caseload) and changes in how much it costs to deliver services due to price or salary increase (inflation). Besides these workload–related budget adjustments, the state also adjusts funding to account for policy changes that affect an agency’s costs.

Main Workload Affecting Universities’ Budgets Has Been Enrollment. For UC and CSU, the state’s main caseload adjustment has been related to changes in enrollment. If the state decides to increase enrollment, it sets an enrollment target and provides UC and CSU with funding for each additional authorized student at a specified funding rate. This setting of enrollment targets and determining the associated enrollment–growth funding allocation have long been one of the state’s main annual budget decisions for UC and CSU.

Enrollment Targets Set Expectations for Access. Enrollment targets reflect the state’s expectations for access to the public universities. These expectations are based on the eligibility policies included in the state’s Master Plan for Higher Education. Specifically, the Master Plan requires UC and CSU to admit freshmen students from among the top 12.5 percent and 33 percent, respectively, of the state’s high school graduates. The Master Plan further requires the universities to accept all qualified transfer students. (The universities themselves define which transfer students are qualified, though state law requires UC and CSU to dedicate 60 percent of enrollment slots for upper–division students to allow sufficient room for transfers.) The Master Plan contains no specific eligibility criteria for graduate students, though it encourages the universities to consider state workforce needs, such as for physicians.

Enrollment Targets Based on Several Considerations. The state typically took into account a number of factors when setting enrollment targets. One main consideration was changes in the college–age population. The state also routinely considered college participation rates and freshman eligibility studies. Freshman eligibility studies were designed to determine if UC and CSU were drawing from less or more than their Master Plan eligibility pools. (These studies were conducted by the California Postsecondary Education Commission, which the state closed down in 2011. The last study conducted was published in 2007.)

Marginal Cost Formulas Used to Calculate Enrollment Costs. To calculate the associated cost of enrollment growth, the state used a marginal cost formula. Figure 1 displays the marginal cost calculations for UC and CSU for 2014–15 if the historical formula were to be used. As shown in the figure, the formulas approximate the staffing resources and operating expenses necessary to educate an additional student. They estimate teaching costs based on fixed student–to–faculty ratios and actual salaries and benefits for new faculty. Other cost components, such as academic support, are based on the average cost per student. (For some of these other areas, certain subcategories of costs, such as for museums and executive management, are excluded.) The marginal cost formulas were used both to provide funding to the universities for increases in enrollment targets as well as to take money back from the universities should they fail to meet their targets.

Figure 1

Calculation for Funding an Additional Studenta

2014–15 Marginal Cost Calculation

|

Cost Categoryb

|

UC

|

CSU

|

|

Faculty salaryc

|

$5,839

|

$3,767

|

|

Faculty benefits

|

1,876

|

1,740

|

|

Teaching assistant (TA) salaryd

|

570

|

23

|

|

Instructional support

|

3,796

|

628

|

|

Instructional equipment

|

391

|

93

|

|

Academic support

|

1,226

|

1,285

|

|

Student services

|

917

|

1,057

|

|

Institutional support

|

820

|

1,169

|

|

Operation and maintenance

|

2,160

|

1,074

|

|

Total Marginal Cost

|

$17,591

|

$10,836

|

|

Less Student Fee Revenuee

|

–$9,079

|

–$4,837

|

|

State Funding Rate

|

$8,512

|

$5,999

|

Base Augmentations Provided to Maintain Purchasing Power. The state’s other main workload adjustment for UC and CSU has been base augmentations to cover cost increases. These augmentations are intended to cover inflationary increases for salaries and benefits, utilities, supplies, and other expenses. These base augmentations allow the universities to maintain their purchasing power in order to keep their educational programs running at a consistent level. In the past, base augmentations typically corresponded with expected inflation, as measured by a price index of goods purchased by state and local governments.

Other Workload Adjustments Also Provided to Cover Cost Increases. The state also routinely adjusted the universities’ budgets to account for a few other changes in costs. Most notably, the state adjusted the universities’ budgets to account for changes in pension costs, retiree health benefits, and debt service. These areas were funded separately from base augmentations because their costs did not always track with inflation.

Targeted Funding Provided for Specific State Priorities. The state also earmarked specific amounts of funding in the universities’ budgets for certain state priorities, such as student outreach programs. Typically, UC’s budget has contained a dozen or so earmarks, while CSU’s budget has contained about half as many earmarks.

State Historically Has Not Had a Policy on Tuition. Though traditional state budgetary practices for UC and CSU were similar to those used for other state agencies in many ways, a key difference is that the universities have the authority to raise additional revenue. That is, along with state General Fund, tuition revenues are used to support the universities’ core programs. The state, however, typically has not had a policy on student tuition levels. Instead, the universities generally have been free to set tuition at levels that generate a certain amount of desired revenue for their programs. In practice, the universities usually set tuition levels to generate enough revenue to cover any increases in their expenditures that were not covered with state funding. (Non–resident and professional degree supplemental tuition charges also are set based on other factors, including how much students are willing to pay.)

State Bonds Used to Support Capital Projects. To access state funding for capital projects, the universities traditionally submitted specific capital project proposals to the state that included each project’s scope, cost, and schedule. These proposals typically were related to constructing new academic facilities and modernizing existing facilities. To pay for projects it had approved, the state issued bonds and repaid the associated debt service.

Funding Provided to Systems, Not Campuses. The state’s funding decisions traditionally have been made at the systemwide level. The state budget has appropriated funds to the universities’ central offices, which then have distributed these funds to their campuses. Both universities have governing boards that are responsible for overseeing how the central offices distribute funding to the campuses.

State Approach to Funding UC and CSU at a Crossroads

State Has Taken Different Budgetary Approaches Since 2008–09. From the onset of the most recent recession (2008–09) through the current budget (2013–14), the state has largely abandoned its traditional funding approach for UC and CSU. Throughout most of this period, the state shifted away from its normal funding practices because it was trying to address the state’s fiscal shortfall. As the state has recovered from these fiscal difficulties, however, it has continued to depart from its traditional funding approach. Below, we recap the various ways in which the state has approached the universities’ budgets in recent years.

Enrollment Funding and Targets No Longer Included in Budget. As shown in Figure 2, since 2007–08, the state budget only twice included both enrollment targets and enrollment growth funding. The state’s ad–hoc approach during this time is at least partly due to difficult budget years in which the state reduced the universities’ budgets and, in turn, provided the universities with increased flexibility in how to respond, including setting their own enrollment levels. Though the state recovered its fiscal footing in 2013–14, the current budget also omitted enrollment targets and funding. The Legislature, however, expressed its interest in resuming funding enrollment by adopting the reporting language directing our office to review enrollment funding practices. To gain further knowledge about enrollment costs, the Legislature also directed UC and CSU to report on the cost of education by student level and discipline categories starting in October 2014. (Appendix A at the end of this report contains the enrollment reporting language, while Appendix B contains the cost of education reporting language.)

Figure 2

Enrollment Targets and Enrollment Growth Funding Not Used on a Consistent Basis in Recent Years

Full–Time Equivalent Students

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14a

|

|

UC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrollment target

|

198,455

|

None

|

None

|

209,977

|

209,977b

|

209,977b

|

None

|

|

Enrollment growth

|

5,000

|

—

|

—

|

5,121

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Actual enrollment

|

203,906

|

210,558

|

213,589

|

214,692

|

213,763

|

211,212

|

210,986

|

|

Funding rate

|

$10,586

|

—

|

—

|

$10,011

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Percent change in actual enrollment

|

|

3.3%

|

1.4%

|

0.5%

|

–0.4%

|

–0.5%

|

–0.1%

|

|

CSU

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrollment target

|

342,553

|

None

|

None

|

339,873

|

331,716b

|

331,716b

|

None

|

|

Enrollment growth

|

8,355

|

—

|

—

|

8,290

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Actual enrollment

|

353,915

|

357,223

|

340,289

|

328,155

|

341,280

|

343,227

|

350,000

|

|

Funding rate

|

$7,710

|

—

|

—

|

$7,305

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Percent change in actual enrollment

|

|

0.9%

|

–4.7%

|

–3.6%

|

4.0%

|

–0.4%

|

2.0%

|

Base Augmentations Not Linked with Costs. Throughout the recession, the state for the most part did not provide base increases to UC and CSU to account for inflation. (By not providing inflation adjustments, the state effectively was directing the universities to absorb the relatively low inflationary cost increases that occurred during this time using internal measures.) More recently, as the state has resumed providing base increases, it has not adopted augmentations based on expected inflation. Further departing from the traditional approach, CSU’s base increases have not been derived based on its own budget but instead have been based on UC’s budget.

Most Funding Not Targeted for Specific Purposes. In order to provide the universities with more flexibility, the state eliminated many of the earmarks in the universities’ budgets over the last few years. The 2013–14 budget includes very few earmarks compared to past budgets. The most notable earmark in the current budget is $15 million for UC to open a new medical school at the Riverside campus.

Universities Still Determine Tuition Levels in Response to State Funding. One budget area where the state continued its traditional approach is student tuition. The state continued to budget each year without a tuition policy (though in recent years the state has expressed an expectation that the universities not raise tuition). In the absence of such a policy, tuition levels and revenues notably spiked and leveled off, as the universities made their tuition decisions each year based on available state funding. From 2008–09 through 2011–12, tuition levels and revenues increased significantly at both UC and CSU in response to cuts in state funding. Since 2011–12, tuition levels and revenues have remained flat as the state has resumed providing budget augmentations.

New Capital Outlay Process Adopted for UC. In a major departure from past practice, the state adopted a new process for UC capital outlay as part of the 2013–14 budget. Under this new process, the state no longer uses state bond funding to support UC’s capital projects. Instead, UC has been given the authority to pledge its state support appropriation to issue its own debt to pay for academic facilities. The university is to pay for the associated debt service from its main state support appropriation. (To enable the university to pay for the debt service, the state shifted funding associated with existing debt service on UC projects into UC’s support appropriation.) In order to use the new authority, the university is required to notify and seek approval from the Joint Legislative Budget Committee and the Department of Finance. However, UC’s capital projects no longer are heard by budget committees or listed in the state budget. For CSU, the state continues to use the traditional capital outlay budget process.

Universities Required to Report on New Performance Measures. After considerable debate in recent years regarding ways to include performance funding in UC and CSU’s budget, the 2013–14 budget package established a new requirement for UC and CSU to report annually, beginning March 1, 2014, on a number of performance outcomes. As shown in Figure 3, the universities now are required to report on graduation rates, funding per degree, and the number of transfer and low–income students enrolled, among other measures. These measures are intended to be used to “guide” future budget decisions, though the legislation did not specify exactly how the measures would be used. (Appendix C contains the language in trailer legislation requiring the universities to report on specified outcome measures.)

Figure 3

Performance Metrics for UC and CSU

|

Metric

|

Definition

|

|

CCC transfers

|

(1) Number of CCC transfers enrolled.

|

|

|

(2) CCC transfers as a percent of undergraduate population.

|

|

Low–income students

|

(1) Number of Pell Grant recipients enrolled.

|

|

|

(2) Pell Grant recipients as a percent of total student population.

|

|

Graduation ratesa

|

(1) Four– and six–year graduation rates for freshmen entrants.

|

|

|

(2) Two– and three–year graduation rates for CCC transfers. Both of these measures also calculated separately for low–income students.

|

|

Degree completions

|

Number of degrees awarded annually in total and for:

|

|

|

(1) Freshman entrants.

|

|

|

(2) Transfers.

|

|

|

(3) Graduate students.

|

|

|

(4) Low–income students.

|

|

First–year students on track to degree

|

Percentage of first–year undergraduates earning enough credits to graduate within four years.

|

|

Funding per degree

|

(1) Total core funding divided by total degrees.

|

|

|

(2) Core funding for undergraduate education divided by total undergraduate degrees.

|

|

Units per degree

|

Average course units earned at graduation for:

|

|

|

(1) Freshman entrants.

|

|

|

(2) Transfers.

|

|

Degree completions in STEM fields

|

Number of STEM degrees awarded annually to:

|

|

|

(1) Undergraduate students.

|

|

|

(2) Graduate students.

|

|

|

(3) Low–income students.

|

Additional Factors for Higher Education Budget Decisions. The Legislature also recently added factors to consider in the budget process for UC and CSU by passing Chapter 367, Statutes of 2013 (SB 195, Liu). This bill establishes three goals for higher education budget decision–making moving forward.

- Improving student access and success, such as by increasing participation from certain demographic groups and by improving completion rates for all students.

- Better aligning degrees and credentials with the state’s economic, workforce, and civic needs.

- Ensuring the effective and efficient use of resources in order to increase high–quality postsecondary educational outcomes and maintain affordability.

The bill states the Legislature’s intent to develop metrics in the future to measure progress toward meeting these goals. These metrics are to take into account the aforementioned outcome measures the universities are required to report on through the budget process. (Appendix D contains the complete language of Chapter 367.)

This section assesses the state’s traditional funding approach as well as its more recent budgetary approach for UC and CSU.

Traditional Funding Approach Has Both Pluses and Minuses

Enrollment Funding Helpful for Establishing State’s Expectations for Access . . . As noted earlier, enrollment budgeting directly relates to the level of access to the public universities, which historically has been a strong state priority. By linking funding with students, the traditional enrollment funding model easily allows the state to influence the level of access provided by the universities. This is because the universities must serve the number of students specified in the budget or risk losing some of their state funding.

. . . But a Few Shortcomings With Process Used to Set Enrollment Targets. Regarding the state’s method for setting enrollment targets, a few notable shortcomings existed.

- Focused Only on Access for Undergraduates. Traditionally, the state only considered access for undergraduates in setting enrollment targets. The state did not consider graduate student access or other state goals related to enrollment, such as state workforce needs. Moreover, by setting a single target, the state allowed the universities to determine the mix of student enrollment. (Also, because the state had a single enrollment target for all students, the marginal cost calculation did not distinguish costs for different student levels or disciplines.)

- Enrollment Decisions Made by Universities Before State Set Targets. Under the traditional process, enrollment targets were finalized when the state budget passed in June—after the universities had made their admissions decisions for the fall semester. This meant the state ended up having little influence over UC’s admissions decisions, as most UC students enter in the fall. For CSU, if the state did not fund enrollment based on the university’s plan, then CSU had to make potentially large adjustments in its spring admissions.

Enrollment and Inflation Funding Helped Connect Funding With Costs . . . By funding workload such as enrollment and inflation, the state aimed to connect funding with costs. This allowed the universities to maintain their programs from year to year, while it allowed the state to have knowledge over how its funds were being spent. Moreover, the state’s approach to estimating enrollment and inflation costs balanced accuracy with simplicity.

. . . But Lacked Incentives for Universities to Be Efficient. Despite connecting funding and costs, the traditional approach had one negative aspect. Neither the marginal cost calculation nor the base augmentations for inflation provided an incentive for the universities to reduce their costs. Rather, these budget adjustments were designed simply to cover cost increases.

Targeted Funding Not Always Connected With Highest State Priorities. Targeting funding for specific purposes in theory helps the state ensure that its priorities are being met. In practice, however, the state had a tendency to earmark relatively small amounts of funding for narrow purposes. For example, several recent budgets included a $3.2 million earmark for a supercomputer center at the San Diego campus. Moreover, some specific earmarks became outdated. For example, the state many years ago earmarked $52 million of UC’s budget for financial aid at a time when the university itself provided relatively little financial aid. This earmark continued each year until 2012–13, even though by then UC was providing students with a little over $1 billion annually in financial aid.

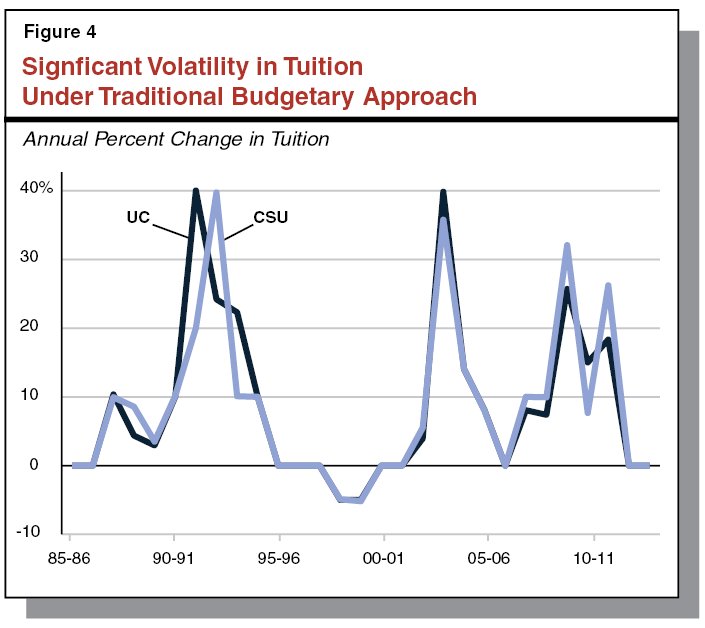

Tuition Decisions Led to Volatility for Students. Because the state traditionally has not had an explicit tuition policy, student tuition levels generally have fluctuated in response to state budget conditions. During times when the state budget has been balanced, tuition levels have remained flat. In contrast, during times when the state budget has suffered a shortfall, tuition levels have increased sharply. This can create difficulty for some middle– and upper–income students enrolled during times of sharp increases, as these students do not qualify for state financial aid (which increases to match tuition increases). Similar students enrolled during times of state fiscal stability, however, benefit from flat tuition. The impact on any particular middle– or upper–income student traditionally has been related solely to the timing of when they enroll. Figure 4 illustrates the volatility in tuition levels over the last three decades.

Traditional Approach to Capital Outlay Allowed for Transparent State Review and Oversight. In the area of capital outlay, the state’s traditional budgetary approach included hearings open to the public to comment on proposed projects. This provided a transparent and deliberative forum for overseeing state expenditures. Under the traditional approach, funding, however, could be sporadic in that voters might not approve a state bond measure or the state might suspend bond sales due to a fiscal downturn.

Mixed Review of Current Budgetary Approach

Unallocated Funding Approach Problematic. The state’s current practice of providing unallocated base increases lacks transparency since the state has not identified why the specific amounts of funding are being provided. For example, the state has not articulated whether these base increases are intended to expand enrollment, cover cost increases, or enhance programs. Instead, the current state budget provides UC and CSU with base increases of a seemingly arbitrary amount. Moreover, the current budget provides UC and CSU with the same base augmentations, despite differences in missions and costs at the two universities.

Including Performance Measures in Funding Process Helps State Focus on Broader Set of Priorities . . . In the past, the main decisions regarding how to budget for UC and CSU have addressed mostly access and inflationary adjustments. Yet, the state recently has adopted several other goals for higher education, including student success and the relevance of educational programs for meeting state workforce needs. The state’s newly adopted performance measures incorporate these other state priorities into the budget process.

. . . But Unclear the Role These Measures Will Have in Budget Process. So far, the state has only required that the segments report information about how they are furthering certain state priorities. While this is an initial step in the right direction, the state has not yet determined how it will actually hold the universities accountable for making progress toward meeting these priorities. Notably, the state has chosen not to create a specific link between funding and performance measures. While this might be viewed as a weakness in terms of holding the universities accountable for performance, not having a funding formula allows for more flexibility and professional judgment on the part of the state in making its budget decisions.

New Capital Outlay Process for UC Raises Concerns. By removing the review and approval of UC capital outlay projects from the regular state budget process, the new capital outlay process for UC has been made less transparent and deliberative. For example, UC’s 2013–14 capital program includes $87 million in capital expenditures that were approved without a budget hearing. Moreover, it is unclear whether the change in debt issuance practices (whereby UC issues bonds) will actually result in more stability in the long term. Furthermore, the administration, Legislature, and segments appear to have somewhat different understandings regarding the state’s versus the segments’ facility responsibilities moving forward.

Because the state’s traditional and current approaches to funding UC and CSU both have strengths and weaknesses, we recommend the Legislature move forward by building upon the positive elements from each. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature retain the basic elements of the traditional funding approach—including funding enrollment and inflation—but add some refinements to address some of its shortcomings. In addition, we recommend the Legislature build upon its recent efforts to consider the universities’ performance as part of the budget process. Figure 5 summarizes these recommendations, which are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 5

Summary of Recommendations

|

Refine Traditional Budgetary Approach

|

- ✓ Authorize updated freshman eligibility study.

|

- ✓ Establish different enrollment targets and funding rates for different types of students.

|

- ✓ Set enrollment targets for year after budget year.

|

- ✓ Fund inflation instead of unallocated base increases.

|

- ✓ Limit earmarks to highest state priorities and review periodically.

|

- ✓ Adopt a share of cost tuition policy.

|

- ✓ Maintain traditional review and approval process for funding capital projects.

|

|

Use Performance Measures to Guide Budgetary Decisions

|

- ✓ Require universities to report on measures at budget hearings.

|

- ✓ Identify causes for universities meeting or not meeting state expectations and adjust funding accordingly.

|

Refine Traditional Funding Approach

Despite some weaknesses in the state’s traditional approach to funding UC and CSU, the state’s treatment of the universities overall had positive features, particularly by connecting funding and costs and building in incentives for the universities to meet expectations on access. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature retain this basic budgetary approach but make the following refinements.

Authorize an Updated Eligibility Study. We recommend the Legislature authorize an updated freshman eligibility study, as the last eligibility study was undertaken six years ago. Information from such a study is necessary to determine whether UC and CSU currently are drawing from less or more than their Master Plan eligibility pools. If the study concludes the universities are drawing from beyond their eligibility pools, this information suggests that enrollment levels currently are too high. If the study concludes the universities are drawing from too small a pool of students, this information suggests that enrollment levels currently are too low. (Such a study must be conducted by reviewing transcripts of high school students and linking with university admissions. Given the amount of coordination required across high schools, UC, and CSU, the state traditionally has relied on independent consultants to undertake parts of the study.)

Make More Targeted Decisions on Enrollment. We recommend the Legislature establish different enrollment targets for different types of students. This would allow the Legislature to set expectations for access for different student groups. For instance, the Legislature could set one target for undergraduate enrollment and another target for graduate enrollment. The Legislature also could consider targets for different disciplines by taking into consideration state workforce needs. (Once UC and CSU submit their required reports on the cost of education by student level and discipline starting in October 2014, information will be available to create different marginal cost formulas to distinguish these targets. Currently, information is not available to make these calculations.)

Better Align State and University Enrollment Decisions. We also recommend the Legislature set enrollment targets for the year after the budget year. This would allow the universities more time to plan their admissions decisions accordingly, though it would entail making a commitment for enrollment funding prior to the development of the state’s budget for that year. Ideally, in times of fiscal stability, the Legislature would be able to honor this spending commitment. A risk exists, however, that a state fiscal shortfall could necessitate revisions to the approved enrollment target. Nonetheless, over the long term, such a budgetary practice would give the Legislature more influence in setting enrollment levels and the systems more certainty over planning for enrollment.

Fund Inflation Instead of Unallocated Base Increases. Rather than providing unallocated base increases of a seemingly arbitrary amount, we recommend the Legislature link base increases with an inflation index. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature use the state and local deflator index that approximates cost increases for state and local governments. We recommend the Legislature exclude any costs that it decides to fund separately (such as pension costs or debt service) from the inflation adjustment calculation.

Limit Targeted Funding to Highest Priorities. We recommend the Legislature in the future only designate funding for specific purposes in the budget when it is of the highest state priority and only when the Legislature has reason to believe the university would not advance these priorities without being required to do so. One example could be an earmark for student outreach programs. Moreover, we recommend the Legislature annually review any earmarks included in the budget to determine whether they are justified on an ongoing basis.

Adopt a Share of Cost Policy. Instead of having tuition levels be set on an ad–hoc basis, we recommend the Legislature adopt a policy that bases tuition at each public university on a share of educational costs. Such a policy would provide a rational basis for tuition levels and a simple mechanism for annually adjusting them. (This share of cost would be factored into both the marginal cost formula and inflationary adjustments.) Though such a policy would depend on the state providing its share of funding, we believe it would be more likely to result moderate, gradual, and predictable tuition increases over time. It also would provide students with a greater incentive to hold the universities accountable for ensuring that proposed cost increases are worthwhile.

Maintain Control Over Capital Outlay. We recommend the Legislature not relinquish further oversight and control over capital expenditures for the universities. Traditionally, the Legislature has considered managing state infrastructure, including university facilities, one of its key responsibilities. Making decisions about the universities’ capital projects also traditionally has been seen as closely connected with the state’s responsibility for ensuring access to undergraduate and graduate academic programs.

Use Performance Metrics to Inform Funding Decisions

One positive aspect of the state’s newer approach to funding UC and CSU is its inclusion of certain state funding priorities, including a greater focus on student success. Below, we offer guidance on how the Legislature could build upon its recent efforts to incorporate performance into its budget decisions.

Require Universities to Present Performance Results at Budget Hearings Each Spring. We recommend the Legislature require UC and CSU to discuss their performance in specific areas (including student access and success) at budget hearings each spring. The Legislature could use this opportunity to learn more about each university’s performance and develop expectations for performance moving forward.

Adjust Funding Accordingly. We further recommend the Legislature use the information reported at budget hearings to make funding decisions based on whether the universities are meeting state expectations. In order to do so, the Legislature would need to work with the universities to identify the reasons why they are or are not meeting state expectations. For example, the state has expressed an interest in the universities improving their four– and six–year graduation rates. However, there could be multiple factors that explain why some students do not graduate within four or six years. Some examples include: (1) course sections not being available for students to take when they need them, (2) students not being able to take enough units each semester to graduate within four or six years because of part–time work or other reasons, (3) poor academic preparation for students that causes them to not graduate at all, or (4) students not focusing on a course of study early enough that results in them taking excess units. Depending on which of these factors are most relevant, the Legislature’s responses would vary. For example, the Legislature might require that the universities redirect their resources in order to better align their course offerings with student demand if it identifies course availability as the main hindrance to timely graduation. The state also could set expectations for funding per degree to encourage the universities to become more efficient.

The state’s longstanding funding practices for UC and CSU have connected funding with costs, thereby matching public dollars with the amount of work needed to fulfill expected public objectives. In particular, enrollment funding has allowed the state to establish its expectations for access to the universities. Apart from some shortcomings with the specific approach used to fund enrollment, this basic budgetary approach has provided a transparent and rational method for the state to allocate funding. At the same time, however, this approach fails to encourage the universities to address other state priorities, such as student success and the relevance of degree programs. The state’s newly adopted performance measures provide an opportunity for the state to monitor progress in these areas. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature budget for the universities by refining its traditional process and by using performance measures to inform its spending decisions.

Enrollment Funding Reporting Requirement

Supplemental Report of the 2013–14 Budget Package

Item 6440–001–0001—University of California

1. Enrollment Funding. The Legislative Analyst, in consultation with the University of California, California State University, and the Department of Finance, shall review the state’s current approach to enrollment funding, including a review of current funding per student and the marginal cost funding formula, and submit a report to the Legislature by January 1, 2014 with recommendations on how to fund enrollment going forward to promote access, quality, and other state higher education goals.

Item 6610–001–0001—California State University

1. Enrollment Funding. The Legislative Analyst, in consultation with the University of California, California State University, and the Department of Finance, shall review the state’s current approach to enrollment funding, including a review of current funding per student and the marginal cost funding formula, and submit a report to the Legislature by January 1, 2014 with recommendations on how to fund enrollment going forward to promote access, quality, and other state higher education goals.

Cost of Education Reporting Requirement

Chapter 50, Statutes of 2013 (AB 94, Committee on Budget)

SEC. 3. Article 10 (commencing with Section 89290) is added to Chapter 2 of Part 55 of Division 8 of Title 3 of the Education Code, to read:

Article 10. Expenditures for Undergraduate and Graduate Instruction and Research Activities

89290. (a) The California State University shall report biennially to the Legislature and the Department of Finance, on or before October 1, 2014, and on or before October 1 of each even–numbered year thereafter, on the total costs of education at the California State University.

(b) The report prepared under this section shall identify the costs of undergraduate education, graduate academic education, graduate professional education, and research activities. All four categories listed in this subdivision shall be reported in total and disaggregated separately by health sciences disciplines, disciplines included in paragraph (10) of subdivision (b) of Section 89295, and all other disciplines. The university shall also separately report on the cost of education for postbaccalaureate teacher education programs. For purposes of this report, research for which a student earns credit toward his or her degree program shall be identified as undergraduate education or graduate education, as appropriate.

(c) The costs shall also be reported by fund source, including all of the following:

(1) State General Fund.

(2) Systemwide tuition and fees.

(3) Nonresident tuition and fees and other student fees.

(d) For any report submitted under this section before January 1, 2017, the costs shall, at a minimum, be reported on a systemwide basis. For any report submitted under this section on or after January 1, 2017, the costs shall be reported on both a systemwide and campus–by–campus basis.

(e) A report to be submitted pursuant to this section shall be submitted in compliance with Section 9795 of the Government Code.

(f) Pursuant to Section 10231.5 of the Government Code, the requirement for submitting a report under this section shall be inoperative on January 1, 2021, pursuant to Section 10231.5 of the Government Code.

SEC. 11. Article 7.5 (commencing with Section 92670) is added to Chapter 6 of Part 57 of Division 9 of Title 3 of the Education Code, to read:

Article 7.5. Expenditures for Undergraduate and Graduate Instruction and Research Activities

92670. (a) The University of California shall report biennially to the Legislature and the Department of Finance, on or before October 1, 2014, and on or before October 1 of each even–numbered year thereafter, on the total costs of education at the University of California.

(b) The report shall identify the costs of undergraduate education, graduate academic education, graduate professional education, and research activities. All four categories listed in this subdivision shall be reported in total and disaggregated separately by health sciences disciplines, disciplines included in paragraph (10) of subdivision (b) of Section 92675, and all other disciplines. For purposes of this report, research for which a student earns credit toward his or her degree program shall be identified as undergraduate education or graduate education.

(c) The costs shall also be reported by fund source, including all of the following:

(1) State General Fund.

(2) Systemwide tuition and fees.

(3) Nonresident tuition and fees and other student fees.

(4) University of California General Funds, including interest on General Fund balances and the portion of indirect cost recovery and patent royalty income used for core educational purposes.

(d) For any report submitted under this section before January 1, 2017, the costs shall, at a minimum, be reported on a systemwide basis. For any report submitted under this section on or after January 1, 2017, the costs shall be reported on both a systemwide and campus–by–campus basis.

(e) A report to be submitted pursuant to this section shall be submitted in compliance with Section 9795 of the Government Code.

(f) Pursuant to Section 10231.5 of the Government Code, the requirement for submitting a report under this section shall be inoperative on January 1, 2021, pursuant to Section 10231.5 of the Government Code.

Performance Measures Reporting Requirement

Chapter 50, Statutes of 2013 (AB 94, Committee on Budget)

SEC. 4. Article 10.5 (commencing with Section 89295) is added to Chapter 2 of Part 55 of Division 8 of Title 3 of the Education Code, to read:

Article 10.5. Reporting of Performance Measures

89295. (a) For purposes of this section, the following terms are defined as follows:

(1) The “four–year graduation rate” means the percentage of a cohort that entered the university as freshmen that successfully graduated within four years.

(2) The “six–year graduation rate” means the percentage of a cohort that entered the university as freshmen that successfully graduated within six years.

(3) The “two–year transfer graduation rate” means the percentage of a cohort that entered the university as junior–level transfer students from the California Community Colleges that successfully graduated within two years.

(4) The “three–year transfer graduation rate” means the percentage of a cohort that entered the university as junior–level transfer students from the California Community Colleges that successfully graduated within three years.

(5) “Low–income students” means students who receive a Pell Grant at any time during their matriculation at the institution.

(b) Commencing with the 2013–14 academic year, the California State University shall report, by March 1 of each year, on the following performance measures for the preceding academic year, to inform budget and policy decisions and promote the effective and efficient use of available resources:

(1) The number of transfer students enrolled annually from the California Community Colleges, and the percentage of transfer students as a proportion of the total undergraduate student population.

(2) The number of low–income students enrolled annually and the percentage of low–income students as a proportion of the total student population.

(3) The systemwide four–year and six–year graduation rates for each cohort of students and, separately, for low–income students.

(4) The systemwide two–year and three–year transfer graduation rates for each cohort of students and, separately, for each cohort of low–income students.

(5) The number of degree completions annually, in total and for the following categories:

(A) Freshman entrants.

(B) Transfer students.

(C) Graduate students.

(D) Low–income students.

(6) The percentage of first–year undergraduates who have earned sufficient course credits by the end of their first year of enrollment to indicate they will complete a degree in four years.

(7) For all students, the total amount of funds received from all sources identified in subdivision (c) of Section 89290 for the year, divided by the number of degrees awarded that same year.

(8) For undergraduate students, the total amount of funds received from all sources identified in subdivision (c) of Section 89290 for the year expended for undergraduate education, divided by the number of undergraduate degrees awarded that same year.

(9) The average number of course credits accumulated by students at the time they complete their degrees, disaggregated by freshman entrants and transfers.

(10) (A) The number of degree completions in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, disaggregated by undergraduate students, graduate students, and low–income students.

(B) For purposes of subparagraph (A), “STEM fields” include, but are not necessarily limited to, all of the following: computer and information sciences, engineering and engineering technologies, biological and biomedical sciences, mathematics and statistics, physical sciences, and science technologies.

SEC. 12. Article 7.7 (commencing with Section 92675) is added to Chapter 6 of Part 57 of Division 9 of Title 3 of the Education Code, to read:

Article 7.7. Reporting of Performance Measures

92675. (a) For purposes of this section, the following terms are defined as follows:

(1) The “four–year graduation rate” means the percentage of a cohort that entered the university as freshmen that successfully graduated within four years.

(2) The “two–year transfer graduation rate” means the percentage of a cohort that entered the university as junior–level transfer students from the California Community Colleges that successfully graduated within two years.

(3) “Low–income students” means students who receive a Pell Grant at any time during their matriculation at the institution.

(b) Commencing with the 2013–14 academic year, the University of California shall report, by March 1 of each year, on the following performance measures for the preceding academic year, to inform budget and policy decisions and promote the effective and efficient use of available resources:

(1) The number of transfer students enrolled annually from the California Community Colleges, and the percentage of transfer students as a proportion of the total undergraduate student population.

(2) The number of low–income students enrolled annually and the percentage of low–income students as a proportion of the total student population.

(3) The systemwide four–year graduation rates for each cohort of students and, separately, for each cohort of low–income students.

(4) The systemwide two–year transfer graduation rates for each cohort of students and, separately, for each cohort of low–income students.

(5) The number of degree completions annually, in total and for the following categories:

(A) Freshman entrants.

(B) Transfer students.

(C) Graduate students.

(D) Low–income students.

(6) The percentage of first–year undergraduates who have earned sufficient course credits by the end of their first year of enrollment to indicate they will complete a degree in four years.

(7) For all students, the total amount of funds received from all sources identified in subdivision (c) of Section 92670 for the year, divided by the number of degrees awarded that same year.

(8) For undergraduate students, the total amount of funds received from the sources identified in subdivision (c) of Section 92670 for the year expended for undergraduate education, divided by the number of undergraduate degrees awarded that same year.

(9) The average number of course credits accumulated by students at the time they complete their degrees, disaggregated by freshman entrants and transfers.

(10) (A) The number of degree completions in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, disaggregated by undergraduate students, graduate students, and low–income students.

(B) For purposes of subparagraph (A), “STEM fields” include, but are not necessarily limited to, all of the following: computer and information sciences, engineering and engineering technologies, biological and biomedical sciences, mathematics and statistics, physical sciences, and science technologies.

State Goals for Higher Education

Chapter 367, Statutes of 2013 (SB 195, Liu)

SECTION 1. Article 2.5 (commencing with Section 66010.9) is added to Chapter 2 of Part 40 of Division 5 of Title 3 of the Education Code, to read:

Article 2.5. State Goals For California’s Postsecondary Education System

66010.9. The Legislature finds and declares all of the following:

(a) Since the enactment of the Master Plan for Higher Education in 1960, California’s system of postsecondary education has provided access and high–quality educational opportunities that have fueled California’s economic growth and promoted social mobility.

(b) In today’s global information economy, California’s national and international success as an educational and economic leader will require strategic investments in, and improved management of, state educational resources.

(c) Several factors, including changing demographics, rising costs, increased competition for scarce state funding, and employer concerns about graduates’ skills, present new challenges to higher education and state policymakers in effectively meeting the postsecondary education needs of Californians.

(d) Although the public segments of postsecondary education have each undertaken efforts to improve reporting and transparency, these efforts do not combine to indicate whether the postsecondary system as a whole is on track to meet the state’s needs.

(e) The absence of a common vision and common goals for California’s postsecondary education system hinders the state’s ability to effectively make critical fiscal and policy decisions.

(f) Policy and educational leaders should collectively hold themselves accountable for meeting the state’s civic and workforce needs, for ensuring the efficient and responsible management of public resources, and for ensuring that California residents have the opportunity to successfully pursue and achieve their postsecondary educational goals.

66010.91. In order to promote the state’s competitive economic position and quality of civic life, it is necessary to increase the level of educational attainment of California’s adult population to meet the state’s civic and workforce needs. To achieve that objective, it is the intent of the Legislature that budget and policy decisions regarding postsecondary education generally adhere to all of the following goals:

(a) Improve student access and success, which shall include, but not necessarily be limited to, all of the following goals: greater participation by demographic groups, including low–income students, that have historically participated at lower rates, greater completion rates by all students, and improved outcomes for graduates.

(b) Better align degrees and credentials with the state’s economic, workforce, and civic needs.

(c) Ensure the effective and efficient use of resources in order to increase high–quality postsecondary educational outcomes and maintain affordability.

66010.93. (a) It is the intent of the Legislature that appropriate metrics be identified, defined, and formally adopted for the purpose of monitoring progress toward the achievement of the goals specified in Section 66010.91. It is further the intent of the Legislature that all of the following occur:

(1) The metrics take into account the distinct missions of the different segments of postsecondary education.

(2) At least six, and no more than 12, metrics be developed that can be derived from publicly available data sources for purposes of periodically assessing the state’s progress toward meeting each of the goals specified in Section 66010.91.

(3) The metrics be disaggregated and reported by gender, race or ethnicity, income, age group, and full–time or part–time enrollment status, where appropriate and applicable.

(4) The metrics be used for purposes of the requirements of subdivision (a) of Section 69433.2.

(5) The metrics take into account the performance measures required to be reported pursuant to Sections 89295 and 92675.

(b) It is the intent of the Legislature to promote progress on the statewide educational and economic policy goals specified in Section 66010.91 through budget and policy decisions regarding postsecondary education. It is the intent of the Legislature that the metrics be used to ensure the effective and efficient use of state resources available to postsecondary education. It is further the intent of the Legislature that progress on the adopted metrics be reported and considered as part of the annual State Budget process.

66010.95. For the purposes of this chapter, “segments of postsecondary education” means the California Community Colleges, the California State University, the University of California, independent institutions of higher education, as defined in Section 66010, and private postsecondary educational institutions, as defined in Section 94858.