In this section we describe CDE’s major activities as well as identify statewide education functions performed by agencies other than CDE.

Figure 2

Major Statewide Education Functions Not Administered by CDE

- Teacher–Related Activities. Administered by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC). The CTC accredits teacher preparation programs, issues teacher credentials, collects information on teacher misassignments, and monitors teacher conduct.

|

- Fiscal Assistance for LEAs. Administered by the Fiscal Crisis Management and Assistance Team (FCMAT), operated out of Kern COE. The FCMAT provides fiscal advice, management assistance, training, and other related services to LEAs in need of such assistance. (The CDE oversees school districts that receive emergency state loans.)

|

- Assistance to LEAs on Managing Student Data. Also administered by FCMAT. The California School Information Services project assists LEAs with data management practices and electronically exchanging data with the state’s California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System and other K–12 and postsecondary institutions.

|

- Academic Intervention and Support. Various statewide initiatives implemented by various COEs to support schools and districts identified by state and federal accountability metrics as low–performing. Initiatives include the Regional System of District and School Support, District Assistance and Intervention Teams, and Title III COE leads.

|

- Oversight of State Funding for School Facilities. Administered and overseen by the State Allocation Board (SAB) and the Office of Public School Construction (OPSC). The SAB apportions funds from voter–approved state bonds to LEAs and adopts policies and regulations related to school facilities. The OPSC administers the state’s school facilities construction program.

|

- K–12 High Speed Network. Overseen by the Imperial COE. The Imperial COE manages LEA participation in a high–speed internet network.

|

State Relies on COEs for Certain Key Monitoring Responsibilities. Given the size of the state, number of LEAs, and diversity among LEAs, the state relies on COEs to provide some statewide monitoring activities. While each of the state’s 58 COEs offers a unique array of services for the school districts in its county, the state has tasked every COE with certain statewide roles. State–required COE oversight activities historically have included reviewing and approving district budgets as well as monitoring that districts have sufficient instructional materials, are staffed with qualified teachers, and maintain adequate facility conditions. The recent Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) legislation added some new oversight responsibilities for COEs, including reviewing districts’ Local Control and Accountability Plans and verifying districts’ counts of certain student groups. In many of these ways, COEs in California carry out tasks that the state departments of education in other smaller states perform directly.

State Relies Primarily on COEs, Not CDE, to Help Districts Improve Student Outcomes. Based on many districts’ preferences and the structure of many education programs, COEs are more likely than CDE to provide direct assistance and specific advice to LEAs on how they can improve their educational programs. The COEs frequently provide professional development, technical assistance, and other forms of support for their districts. The state, however, also has tasked certain COEs with providing formal assistance within their regions for schools and districts identified as needing intervention under the federal or state accountability systems. Specific intervention initiatives include the Regional System of District and School Support, District Assistance and Intervention Teams, and Title III regional COE leads.

In this section, we describe CDE’s organizational structure, its staffing levels, and its funding sources and levels. (The CDE also operates three statewide schools for blind and deaf students and three state diagnostic centers serving students with disabilities and their families. Because this report focuses on CDE’s role as administrator of statewide education programs, all totals throughout this report exclude funding and positions for daily operation of those six sites.)

Organizational Structure and Staffing

The State Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI) Oversees CDE Operations, Advocates for His or Her Priorities. The SPI oversees day–to–day CDE operations. This includes responsibility for managing CDE staff and ensuring they perform required activities. In California, the SPI is a non–partisan position elected by voters to serve up to two four–year terms. (This contrasts with most other states in which the officer heading the department of education typically is appointed by the governor or state board of education. As discussed in the nearby box, previous researchers have raised concerns about the state’s educational governance structure.) While the SPI’s primary responsibility is to oversee program implementation, the SPI commonly advocates to the Governor and Legislature for passage of certain education policies and initiatives he or she believes would be beneficial. (The SPI also serves as a nonvoting member of SBE.) Additionally, the SPI typically dedicates a small share of the CDE budget—often paired with funding from private sources—to undertake discretionary projects, including convening advisory task forces to make policy recommendations.

California’s Educational Governance Structure Highly Criticized

Previous Studies Have Highlighted Shortcomings. Several research reports have highlighted concerns with California’s system of educational governance, including the roles played by the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI) and California Department of Education (CDE). Frequently cited criticisms about the existing structure include the following:

- Contains Overlapping Roles, Lacks Clear Lines of Responsibility. The Legislature, Governor, and State Board of Education (SBE) all play roles in developing education policies, sometimes leading to inconsistent or even conflicting policies. Moreover, the SPI—who is not charged with developing policy and who does not report to any of the policy–making entities—can modify those policies through their administration.

- Lacks Clear Lines of Accountability. The spreading of statewide responsibilities across multiple agencies makes holding the state’s educational system accountable challenging. As the SPI does not report to the Governor (in contrast with most other state departments), holding CDE accountable for its performance also is relatively difficult.

- Creates Potential Conflicts of Interest. The SPI is charged with assessing the effectiveness of the same educational system that he or she also is charged with administering. Moreover, the SPI may be charged with implementing policies that he or she actively opposed.

Suggested Alternatives Have Included Restructuring CDE Governance. Researchers have suggested various alternative structures the state could adopt, including a major restructuring of CDE management and the roles of the SPI and SBE. While an analysis of these issues and proposals is beyond the scope of this report, we believe the state could benefit from exploring options for improving efficiency and accountability within its educational governance system. In particular, the state could further explore whether other entities might be better positioned to carry out some of the state–level responsibilities currently assigned to the SPI.

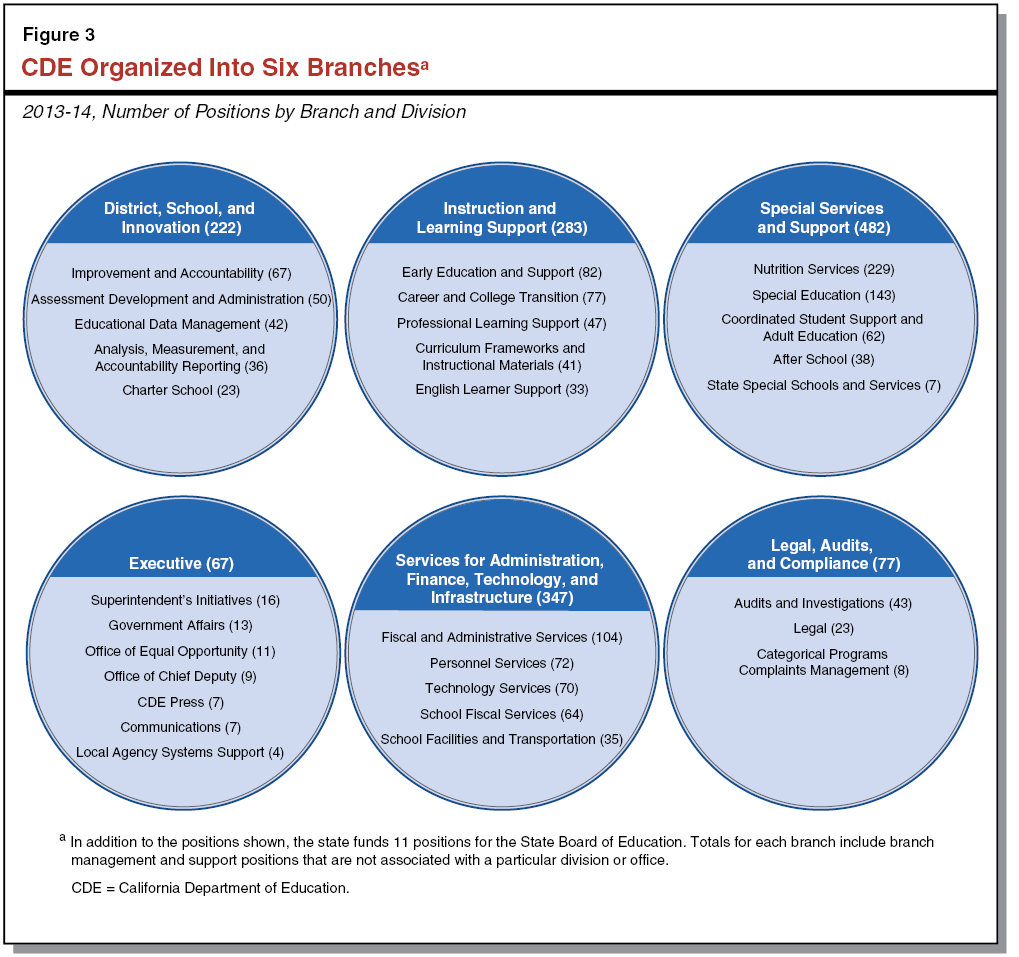

Staff Organized Into Six Branches and 30 Divisions. Generally, the SPI has discretion to organize CDE staff in whatever way he or she believes will be most effective to perform departmental functions. Over the years, SPIs have reorganized staff in different ways based on the specific priorities of the era or the individual. As shown in Figure 3, the current SPI has organized CDE employees into six branches, with each branch containing between three and seven divisions or offices. According to CDE executive staff, the branches generally are organized around thematic areas, with three branches primarily focused on services for LEAs and three primarily focused on internal CDE functions. Appendix A contains a detailed description of the total funding for and primary activities performed by each CDE branch.

CDE Has Roughly 1,500 Staff. The 2013–14 budget authorized 1,490 full–time equivalent (FTE) positions for CDE. (This total includes 11 positions that exclusively support SBE and report to SBE’s executive director, not the SPI.) The majority of the staff works at the CDE headquarters building in Sacramento. Roughly 100 individuals—primarily overseeing components of child nutrition programs—work in other locations. (Other CDE locations include food distribution centers in Sacramento and Pomona and about 25 small nutrition field offices spread throughout the state, as well as the CDE Press publishing facility and a school bus driver training facility, both located in Sacramento.) As shown in Figure 3, the largest CDE branch is Special Services and Support with 482 positions. This branch also contains the two largest CDE divisions—Nutrition Services (229 positions) and Special Education (143 positions).

CDE Vacancy Rate of 8 Percent Comparable to Similarly Sized Departments. As of June 2014, 8 percent of CDE’s authorized positions (124) were vacant. This rate is comparable to other similarly sized state departments, and is lower than CDE’s typical vacancy rate before the state’s economic downturn. (As discussed below, in recent years the state eliminated authority for many vacant CDE positions.) While in previous years certain CDE divisions maintained chronically high vacancy rates, eliminating some positions and changing hiring practices to promote more internal candidates seem to have reduced persistent vacancies.

Funding

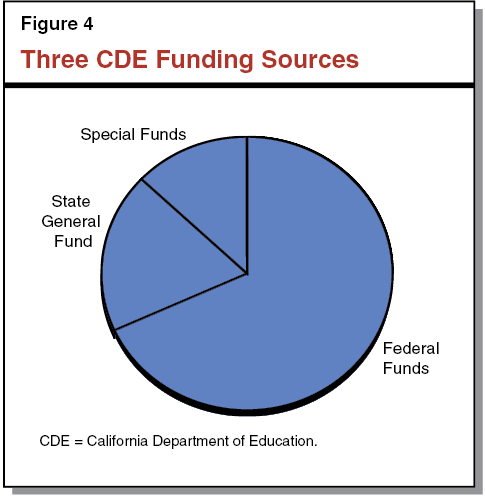

CDE Operations Supported by Three Funding Sources. In 2013–14, CDE received $251 million in total funding. As shown in Figure 4, federal funds made up the bulk (68 percent, or $171 million) of this total. (Most federal grants allow CDE to retain a portion of the grant for administrative and oversight activities.) The state provides non–Proposition 98 General Fund monies for CDE to fulfill state–required activities. State General Fund made up 19 percent ($48 million) of the CDE budget in 2013–14. (This total included $2 million for SBE.) The final funding source—monies generated by and for specialized activities—made up 13 percent ($32 million) of CDE’s overall funding.

Majority of Divisions Supported Primarily by Federal Funding. Corresponding to the large proportion of federal funds in the overall CDE budget, the majority of CDE divisions primarily are funded with federal monies. In 2013–14, federal funds made up a majority of the operating budget in 17 of the 30 divisions, and nearly the entire budget for many large divisions, including Nutrition Services and Special Education.

State Funds Spread Throughout Most CDE Divisions. Although state General Fund support for CDE makes up only one–fifth of its overall budget, these monies are spread amongst nearly all divisions. The School Fiscal Services Division—which apportions funds and provides guidance to LEAs on fiscal issues—received the largest share of total General Fund support at $9 million in 2013–14. Only a few divisions are primarily funded with General Fund. These include most of the divisions and offices in CDE’s Executive Branch, including the Office of the Chief Deputy, Communications, and Superintendent’s Initiatives.

Other Specialized Funding Sources Support Specialized Activities. Just over one–tenth of CDE’s budget is supported by various special funds. For example, the 2013–14 budget included $1.7 million from the state’s Driver Training Penalty Assessment Fund to support CDE’s school bus driver training program. Most special fund sources are fee revenues that support related activities, such as fees charged to charter schools and nonpublic schools for CDE staff to oversee them and publisher fees that help fund the costs of state instructional materials adoptions. The CDE’s largest source of special revenue consists of district payments for food deliveries from the federal food commodity program. These revenues are deposited into the Donated Food Revolving Fund ($7.3 million in 2013–14), which CDE uses to operate that program. The department also collects revenue from sales of its various publications to support printing costs. (Publications for sale by CDE Press include summaries of the state’s curriculum frameworks and content standards, as well as a number of resources developed for caregivers serving infants and toddlers.)

Over time, CDE’s personnel and budget have grown as the federal and state governments have tasked the department with additional responsibilities. Like many public agencies, CDE experienced a decline in both positions and funding during the recent economic recession and an increase in positions and funding during the recent economic recovery. In this section, we discuss CDE’s staffing and funding levels over the past 20 years, including a more detailed review of recent trends.

Historical Trends

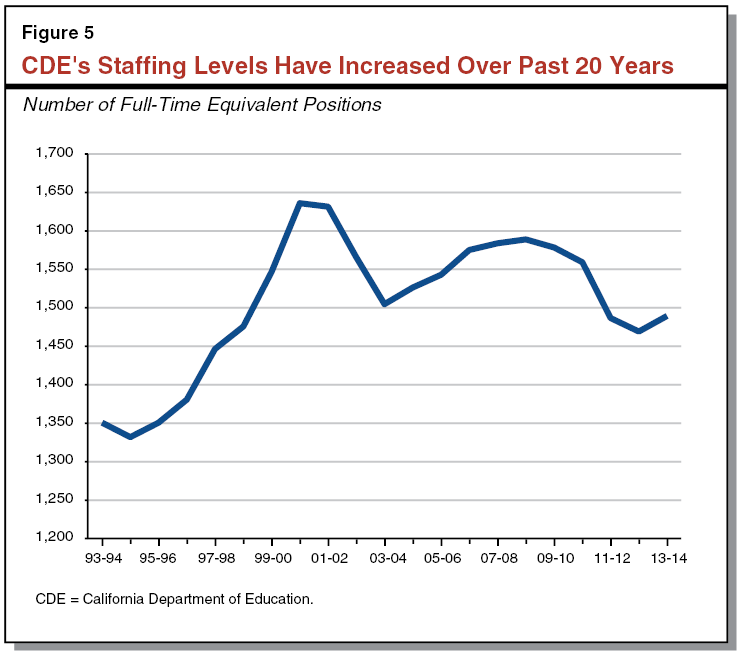

CDE Staffing Levels Have Fluctuated. Figure 5 displays the number of FTE positions authorized at CDE from 1993–94 through 2013–14. The number of positions increased notably (21 percent) between 1993–94 and 2000–01, from 1,351 to 1,636. Significant federal and state education initiatives were implemented during this period—including the federal Improving America’s Schools Act and the state Public Schools Accountability Act—leading to additional CDE responsibilities. The figure displays some small fluctuations in positions between 2000–01 and 2008–09, with a slight decline over the period. The recent economic downturn between 2008–09 and 2012–13 led to a more significant (8 percent) decrease in CDE’s total positions. Additional positions authorized in 2013–14, however, rendered total CDE staffing 10 percent, or nearly 140 positions, higher than staffing levels in 1993–94.

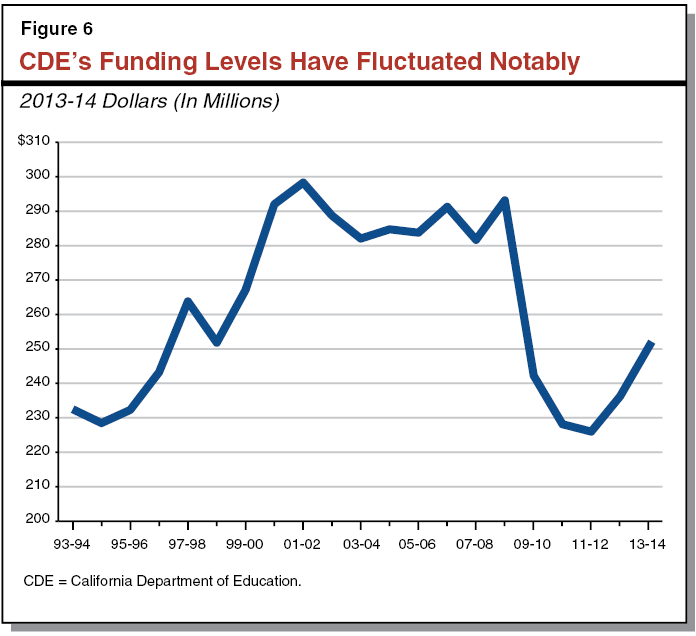

The CDE Budget Also Has Fluctuated. Figure 6 shows total funding for CDE operations over the past 20 years, adjusted for inflation. Unsurprisingly, funding trends generally mirror the staffing trends displayed in Figure 5. As shown in the figure, inflation–adjusted funding increased notably (28 percent) between 1993–94 and 2001–02, to a high of nearly $300 million. Between 2001–02 and 2008–09, the CDE budget remained relatively unchanged, averaging roughly $290 million in adjusted dollars. The figure shows that during the recent recession, the CDE budget declined markedly—to an inflation–adjusted 20–year low in 2011–12—but that recent budgets restored a portion of those reductions. Over the entire period, CDE’s inflation–adjusted funding increased by 8 percent.

Federal Funds Represent a Large and Increasing Share of CDE Funding. Figure 7 shows the proportion of CDE funding supported by federal funds, state General Fund, and special funds over the past20 years. The share covered by federal funds has increased notably over time, from about half of overall funding in 1993–94 to nearly 70 percent in 2013–14. Commensurately, the shares covered by the state General Fund and special funds have dropped—from about one–quarter each to 19 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

Recent Trends

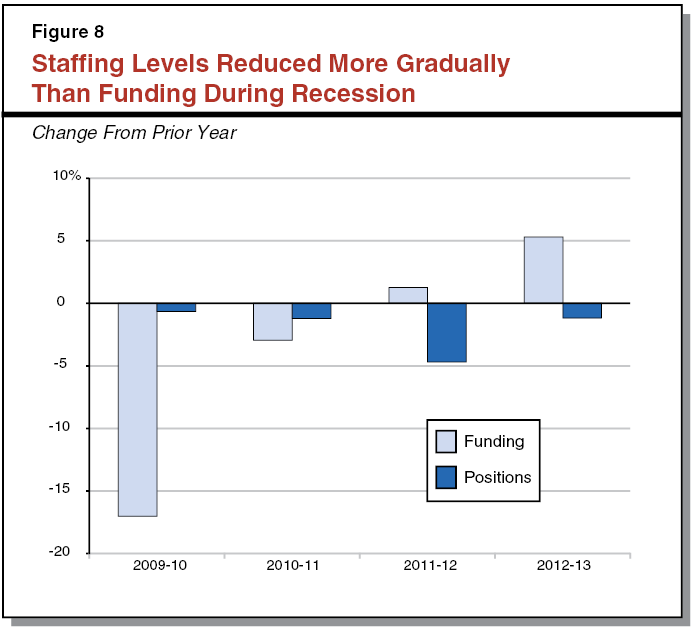

Staffing Levels Were Reduced More Gradually Than Funding During Recession. The recent economic recession and downturn in state revenues led to reductions in both CDE positions and budget. Figure 8 displays the annual percent change in both total authorized staffing levels and budget for CDE between 2008–09 and 2012–13. While the average annual decline across the period was somewhat comparable (2 percent for positions and 3 percent for funding), the figure shows that in certain years staffing levels changed much less than did funding. For example, between 2008–09 and 2009–10, staffing levels declined by only 1 percent whereas funding dropped by 17 percent. This difference largely was a result of the state granting CDE discretion in implementing the funding reductions. Instead of conducting layoffs, CDE achieved savings by implementing staff furloughs and not backfilling for attrition. Over a number of years, the state gradually reduced the number of positions authorized in the annual budget act as positions became vacant. (This explains why the number of authorized positions dropped in 2011–12 and 2012–13 even as funding increased.)

CDE Reductions Corresponded to Reduction in State Requirements. At the same time the state reduced General Fund support for CDE, it implemented major funding changes for schools. Specifically, beginning in late 2008–09, the Legislature suspended the funding formulas and programmatic spending requirements for approximately 40 state categorical programs, providing LEAs greater flexibility over how to use their monies. The CDE staff therefore no longer had to monitor implementation or calculate annual allocations for those programs. Accordingly, many of the positions that CDE eliminated during the recession previously had workload related to “flexed” state categorical programs.

Many Staffing Reductions Related to Changes in State Categorical Programs. Figure 9 shows the CDE divisions from which positions were eliminated between 2008–09 and 2012–13. As shown, the largest number of positions (25) was eliminated from the Professional Learning Support Division, which had overseen several of the state’s categorical programs prior to their being flexed (as well as the federal Reading First program, which was defunded in 2010–11). The next largest reduction (12 positions) came from the School Fiscal Services Division, which had calculated the apportionment formulas for many of the affected categorical programs. (The figure shows eliminated positions but does not show positions that were redirected from one division to another over the same period. As such, individual divisions may have experienced more or less notable changes in overall staffing levels during this period compared to the reductions shown in the figure.)

Figure 9

Eliminated CDE Positions by Division

Reductions Between 2008–09 and 2012–13

|

Division

|

Eliminated Positions

|

|

Professional Learning Support

|

25

|

|

School Fiscal Services

|

12

|

|

Assessment Development and Administration

|

11

|

|

Improvement and Accountability

|

10

|

|

Fiscal and Administrative Services

|

8

|

|

Early Education and Support

|

7

|

|

Audits and Investigations

|

4

|

|

Coordinated Student Support and Adult Education

|

4

|

|

Government Affairs

|

4

|

|

Othera

|

35

|

|

Total

|

119

|

CDE Used Various Strategies to Manage Workload Amid Budget Constraints. While the divisions highlighted in Figure 9 experienced the most notable reductions, most CDE divisions experienced some decrease in staffing levels during the recession. Not all lost positions were associated with flexed or eliminated state categorical programs. The department used various approaches to accommodate those reductions. First, CDE curtailed many activities not explicitly required by federal or state law, including most on–site monitoring and support activities (saving the associated travel costs). Other common strategies CDE employed included adding new tasks to existing staff members’ workload and endeavoring to find a nexus between state and federal goals whenever possible (so as to permissibly use federally funded positions to also meet state goals). The department also identified certain minor activities for which funding and positions were not explicitly identified, deemed them lower priority, and opted not to perform them—sometimes even if they were explicit statutory requirements. For example, as identified in Appendices B and D, the department opted not to complete some reports for the Legislature, citing a lack of resources.

Recent Budgets Included Increases. After several years of reductions, recent state budgets have increased funding for CDE. Together, the 2012–13 and 2013–14 budget packages augmented total CDE funding by $29 million, including a notable increase in state General Fund support ($7 million). Moreover, the 2013–14 budget package authorized an additional 20 positions for the department.

As part of the state budget process, each year the Legislature considers whether CDE should receive augmentations—or reductions—to its authorized positions and budget. To help guide the Legislature in this exercise, this section assesses the existing alignment among CDE activities, staffing, and funding. Figure 10 summarizes our major findings and recommendations.

Figure 10

Summary of Major Findings and Recommendations

|

Finding

|

Recommendation

|

|

CDE has the resources to meet its existing requirements, but has limited capacity to absorb new workload.

|

Align changes in CDE’s responsibilities with changes in resources.

|

|

CDE’s compliance–based orientation limits the value of its interactions with LEAs.

|

Explore ways to make CDE’s oversight activities more valuable for LEAs.

|

|

CDE could play an important role in aligning state and federal requirements.

|

Ensure funding and positions for CDE reflect an integrated system for supporting and intervening in struggling LEAs.

|

|

Certain state reporting requirements provide limited value.

|

Repeal some reporting requirements.

|

CDE Can Meet Existing Requirements but Has Limited Capacity to Absorb New Workload

Overall Staffing Level Reasonably Well Aligned With Existing Responsibilities. While certain divisions may have slightly too many or slightly too few positions relative to current workload, our review did not uncover any glaring misalignment whereby CDE was failing to conduct required activities or had grossly excessive numbers of staff assigned to particular activities. (As noted, we did learn that CDE has not completed some minor state requirements—such as preparing some of the reports listed in Appendices B and D—for which state funding was not explicitly provided.)

Federal Portion of CDE Budget Likely Could Accommodate Some Amount of Additional Workload. . . The department typically underspends its federal funding by around $15 million each year, “carrying over” the funds to the subsequent year. Should a moderate amount of new workload arise that is permissible under federal law, the Legislature therefore could direct CDE to accommodate it using some portion of these funds. For example, in 2014–15, CDE will begin conducting new federally required child nutrition program oversight activities using existing funding and existing authorized positions.

. . . However Existing Federal Funds Likely Cannot Cover All New Workload. While federal funds may be available to help support new CDE activities in some circumstances, the Legislature should not assume this is always the case. When a clear nexus exists between state and federal requirements, federal funds sometimes can be used to help support CDE activities that also achieve state goals. For example, in 2014–15, the federal government granted CDE permission to use federal funds for aligning the state’s English Language Development standards with the state’s academic content standards for mathematics and science (which are considered rigorous standards by the federal government and aligned with standards adopted in other states). Some federal audits over the years, however, have found that CDE has relied too heavily on federal funds to support particular activities. For example, a recent federal audit required CDE to discontinue using federal funds to support certain activities within the English Learner Support Division. (As a result, the department may will be unable to meet those requirements absent additional state funding.) Because state and federal goals for public education frequently overlap, the distinctions around which funding sources should support particular activities are not always clear. The Legislature, however, clearly cannot expect the federal government to pay the entire cost of all overlapping activities.

State Portion of CDE Budget Has Extremely Limited Capacity to Absorb New Workload. In contrast to the federal portion of its budget, our review suggests CDE does not have excess state funding available to dedicate towards new activities. As a result, the department struggles to respond when state legislation passes that implicitly assumes the department will absorb related workload within its existing state resources. The Legislature, for example, provided CDE with no additional staff to implement the Transitional Kindergarten program. (Perhaps as a result, some LEAs have expressed concern with the amount and quality of guidance they are receiving from CDE.)

Recommend Legislature Align Changes in Responsibilities With Changes in Resources. Given CDE’s existing staffing levels and responsibilities generally are well aligned, we recommend that when the state tasks CDE with notable new requirements—either through the annual budget act or other legislation—the Legislature provide the department with additional positions and funding to carry them out. Similarly, should the Legislature reduce CDE’s responsibilities, we recommend the Legislature make a conforming reduction to associated CDE positions and funding. While limited federal funds may be available to support a few new activities, we recommend the Legislature provide CDE with General Fund–supported positions to carry out state–directed activities. Our review suggests that taking on significant additional state–directed workload absent new resources likely would force CDE to deprioritize other activities that may be important to the state.

Compliance–Based Orientation Limits Value of CDE’s Interactions With LEAs

Increased Emphasis on Federal Compliance Has Narrowed Scope of CDE’s Activities. Over the past decade, increasing federal requirements and funding, combined with decreasing state categorical requirements and funding, have led CDE staff to focus predominantly on federally required activities. This has narrowed the focus of CDE’s interactions with LEAs and limited the scope of advice and services CDE staff provides. In interviews, CDE staff reports that previously the department used state categorical funds to employ a larger cadre of education experts to anticipate and respond to LEAs’ wide–ranging needs. In contrast, monitoring, technical assistance, or professional development that CDE staff now provides primarily is oriented around the specific requirements of individual federal grants. Moreover, many CDE staff members predominantly are focused on reviewing paperwork to ensure that LEAs have spent federal funds according to prescribed rules—without evaluating or advising on the effectiveness of LEAs’ expenditure choices or programmatic offerings. In interviews, staff from both CDE and LEAs indicate the department’s compliance orientation has caused LEAs to perceive CDE as increasingly reactive and punitive—and less collaborative and service–oriented.

CDE Could Explore Ways to Make Oversight Activities More Valuable for LEAs. Even within the constraints of federal requirements, we believe CDE could explore opportunities for using federally required activities and federally funded staff to provide more helpful services to LEAs. All states face similar federal requirements, and research suggests these requirements have led most state education agencies to assume regulatory, compliance–focused orientations similar to that of CDE. While changes to federal education law could modify these requirements, such revisions do not seem imminent (as discussed in the nearby box). Yet even given these constraints, some states have adopted more innovative approaches towards undertaking federal activities. Specifically, some state education agencies have expanded the scope of their activities beyond an evaluation of whether the activities LEAs undertake with federal funds are permissible, to trying to ensure those expenditures are effective at improving student outcomes. For example, to provide LEAs with more holistic feedback on improving student outcomes, several states have merged staff responsibilities and funding sources that traditionally have worked in separate silos. These include staff supported by federal grants that fund services for students with disabilities, students from low–income families, and English learner students. Such an approach would represent a paradigm shift for CDE and would require more coordination across—or a reorganization of—CDE divisions. Yet approaches being explored by other state education agencies, as well as various types of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) waivers granted to many states, signal the federal government can be flexible with states that demonstrate a plan for and commitment to improving student outcomes.

Eventual Changes to Federal Education Policy Could Result in Major Changes for CDE

Given addressing federal requirements is considerable workload for the California Deptartment of Education (CDE), notable changes to those requirements could have major implications for the department’s activities, staffing and funding levels, and organizational structure. Many of CDE’s federal activities relate to components of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). The current iteration of the ESEA, known as the No Child Left Behind Act, was passed in 2001 and was scheduled to be reauthorized in 2007. The U.S. Congress, however, has yet to reauthorize the act. While President Obama released a “Blueprint” for ESEA reauthorization that mentioned “fewer, larger, [and] more flexible funding streams,” exactly how and when federal requirements ultimately will change still is uncertain. Major CDE activities associated with the existing ESEA include overseeing certain district programs to support low–income students, English learner students, and teachers; developing and implementing statewide standardized assessments for certain grades and subjects; calculating scores for schools and districts based on how students perform on those assessments; and tracking schools and districts that have consistently low student assessment scores.

Regional Agencies Still Better Positioned to Provide Direct Assistance to LEAs. While we think CDE should explore ways to add value to its federally required compliance activities, we do not believe CDE should be the primary entity charged with assisting LEAs in improving student outcomes. Whereas in other states the staff from state education agencies frequently lead turnaround efforts for struggling schools and districts, tasking CDE with this role would not be practical in a state as large and diverse as California. Given the state’s characteristics and CDE’s existing capacity, we believe COEs and other local entities continue to be better sources for providing most professional development, technical assistance, and other forms of ground–level support to LEAs.

CDE Could Play Important Role in Aligning State and Federal Requirements

Questions Remain Regarding New State Support and Intervention System. In tandem with the LCFF, the Legislature recently adopted new district planning requirements, as well as a new system for supporting and intervening in low–performing districts. While the legislation laid out a general framework for this system, several details still are under development by SBE. Outstanding questions include (1) the specific criteria by which districts will be identified as needing additional support, (2) the specific criteria by which districts will be identified as needing more intensive intervention, (3) which entities will provide this support and intervention, and (4) what form the support and intervention will take.

CDE Could Help Align State and Federal Systems, Avoid Duplication of Effort. As the state develops its new accountability approach, opportunities exist to streamline federal and state activities to avoid establishing two parallel systems of requirements, support, and intervention. The CDE could help SBE in aligning federal and state accountability systems. Federal and state funds, requirements, and intervention activities ultimately should be working in tandem towards one purpose—improving student achievement. Many of the new state requirements for districts are similar to activities associated with federal grants that districts currently are performing and CDE staff currently are monitoring. For example, new state requirements regarding how districts must serve English learner students (such as designing expenditure plans, providing supplemental services, and being identified for additional support and intervention from outside experts if students do not meet achievement goals) are similar to federal requirements under Title III of the NCLB Act. Moreover, the structure for the new state support and intervention system outlined in the LCFF legislation—including the new California Collaborative for Educational Excellence—is similar to the existing Regional System of District and School Support, established pursuant to Title I of the NCLB Act. Coordinating under both federal and state laws (1) the ways in which districts may comply with spending and programmatic requirements, (2) the criteria by which districts are identified for support and intervention, and (3) the support and intervention districts receive would both minimize duplication of effort and lead to a more cohesive education program.

Recommend Funding and Positions for CDE Reflect an Integrated Support and Intervention System. Once the state’s new accountability system is fully implemented, we recommend the Legislature carefully review the staff CDE currently dedicates (and, if applicable, proposes to dedicate) to state and federal support and intervention activities. Moreover, we recommend the Legislature make future funding for these CDE positions contingent on evidence of an integrated accountability system. Streamlining the activities and duties of these staff such that they coordinate across—rather than duplicate—overlapping federal and state requirements would be both more efficient and effective. Given an integrated system would incorporate both state and federal requirements, we recommend the Legislature fund associated CDE staff with a combination of state and federal funds.

Certain State Reporting Requirements Provide Limited Value

Staff Spend Considerable Time Preparing Statutorily Required Reports. The Legislature routinely asks CDE to prepare formal, public reports on numerous topics. Some of these reporting requirements are ongoing whereas some are one–time, and some reports are required by state Education Code whereas others are requested through the annual budget act. In interviews, CDE staff indicated that preparing and reviewing these reports for public release requires considerable time and effort for both programmatic and executive–level staff.

Recommend Legislature Repeal Some Reporting Requirements. We reviewed 77 statutorily required CDE reports to assess whether they provide sufficient statewide benefit to merit the resources required for their production. We recommend the Legislature repeal 54 reporting requirements and maintain 23 reports that continue to provide helpful information. (Appendices B, C, and D contain comprehensive lists of each report and its statutory reference, as well as the rationale behind each of our associated recommended actions.) The recommended eliminations are based on our assessment that the reports no longer are pertinent, do not provide sufficient information to merit their costs, or the information provided therein is otherwise already available or available upon request. Of the reports we recommend eliminating, 43 do not represent current workload for CDE, either because the requirement is obsolete or because CDE has prioritized other activities in lieu of completing them. In tandem with removing the remaining 11 required reports, we recommend that CDE provide information as to the staff and funding currently associated with their production so the Legislature can make corresponding adjustments.

The CDE’s core responsibility is to administer federal and state education programs. Our review found that the department currently is adequately positioned to fulfill this core mission. Our review, however, also indicates that the scope of CDE’s responsibilities—and the associated need for staff and funding—change frequently based on shifting state and federal policies. These findings highlight the important role the Legislature has via the annual budget and policy processes in continuously reassessing CDE’s responsibilities and the appropriate staffing and funding required for the department to carry out those responsibilities.