Understanding California’s voter–approval requirements for local taxes necessitates some basic knowledge of local governments. Therefore, prior to our discussion of voter–approval requirements, in this section we provide a brief introduction to local governments in California.

California Has Over 5,000 Local Governments. Californians receive services from over 5,000 local governments—counties, cities, school districts, community college districts, and special districts (such as fire districts, flood control districts, and water districts). Each local government has a local governing body (such as a city council or board of supervisors) that makes decisions about its programs, services, and operations. Local residents generally elect the members of local governing bodies.

Role of Local Governments. Cities, counties, and special districts share the responsibility of providing municipal services—such as police, fire protection, sewer, water, parks, and libraries—to California residents. Counties, in addition to providing some municipal services, also provide countywide services, such as health and social service programs. School and community college districts are the primary provider of education from kindergarten to lower–level post–secondary education and vocational training.

Local Governments May Increase Property Taxes Only to Finance Voter–Approved Debt. Taxes levied on property owners based on a property’s value are known as ad valorem taxes. (For the remainder of the report, ad valorem property taxes are referred to simply as property taxes.) The State Constitution limits, with narrow exceptions, the property tax rate to 1 percent. Local governments may raise the property tax rate only for two purposes: (1) to pay debt approved by voters prior to July 1, 1978 and (2) to finance bonds for infrastructure projects.

Cities and Counties Have Broad Tax Authority. Outside of the property tax, cities and counties have authority to impose a broad range of taxes, including sales taxes, parcel taxes, utility taxes, hotel taxes, and business taxes. Figure 1 provides descriptions of the primary types of taxes that local governments may impose.

Figure 1

Local Governments Levy Many Types of Taxes

|

Tax

|

Description

|

Local Governments

|

|

Property Tax for debt

|

A levy on property based on the properties’ assessed value and used for voter approved debt.

|

Cities, counties, special districts, and school and community college districts

|

|

Parcel Tax

|

A levy on parcels of property, typically set at some fixed amount per parcel. Cannot be based on a property’s value.

|

Cities, counties, special districts, and school and community college districts

|

|

Sales Tax

|

A levy on the retail sale of tangible goods.

|

Cities, counties, and some special districts

|

|

Hotel Tax

|

A levy on the occupancy of hotels, motels, or other short–term lodging.

|

Cities and counties

|

|

Utility Tax

|

A levy on the use of utilities, such as electricity, gas, or telecommunications.

|

Cities and counties

|

|

Business Tax

|

A levy on operators of businesses.

|

Cities and counties

|

|

Other Taxes

|

Other types of taxes including Mello–Roos taxes and property transfer taxes.

|

Primarily cities and counties

|

Special Districts and School and Community College Districts Have More Narrow Tax Authority. Most special districts and school and community college districts are authorized to levy only parcel taxes to fund services. Parcel taxes generally are paid by most property owners within each local government’s jurisdiction. In some cases, however, certain groups of property owners—such as senior citizens—may be exempted. A limited number of special districts—primarily transportation districts—also may levy sales taxes.

Local governments must obtain the approval of local voters to raise taxes. The only exception to this rule is for property tax rate increases to pay debt approved by voters before 1978. Local government voter–approval requirements vary based on several factors, including the type of local government raising the revenues, the revenue mechanism, and the use of the revenues. In this section we summarize California’s complex system of voter–approval requirements for local taxes.

Is the Charge a Tax?

Some types of local government charges are not considered taxes and, therefore, are not subject to voter approval. In general, a local government levy, charge, or exaction is a tax and subject to voter approval unless it meets at least one of seven exemptions defined in the State Constitution. Figure 2 lists these exemptions. Some charges are categorically exempt: fines and penalties for violating the law, entrance charges and charges for use of government property, local property development charges, and property assessments and property–related fees imposed in accordance with Proposition 218 (discussed in more detail below). Other charges are exempt if they satisfy certain conditions. Charges for a government service, benefit, or product are exempt if the local government (1) charges no more than its reasonable costs, (2) provides the service directly to the payer, and (3) does not provide the service to non–fee payers. In addition, regulatory fees are exempt if the fee is limited to the local government’s direct cost to regulate the fee payer.

Figure 2

Local Government Charges Exempt From Voter Approval

|

|

- A charge imposed for a specific benefit conferred or privilege granted directly to the payer that is not provided to those not charged, and which does not exceed the reasonable costs to the local government of conferring the benefit or granting the privilege.

|

- A charge imposed for a specific government service or product provided directly to the payer that is not provided to those not charged, and which does not exceed the reasonable costs to the local government of providing the service or product.

|

- A charge imposed for the reasonable regulatory costs to a local government for issuing licenses and permits, performing investigations, inspections, audits, enforcing agricultural marketing orders, and the administrative enforcement and adjudication thereof.

|

- A charge imposed for entrance to or use of local government property, or the purchase, rental, or lease of local government property.

|

- A fine, penalty, or other monetary charge imposed by the judicial branch of government or a local government, as a result of a violation of law.

|

- A charge imposed as a condition of property development.

|

- Assessments and property–related fees imposed in accordance with the provisions of Article XIII D.

|

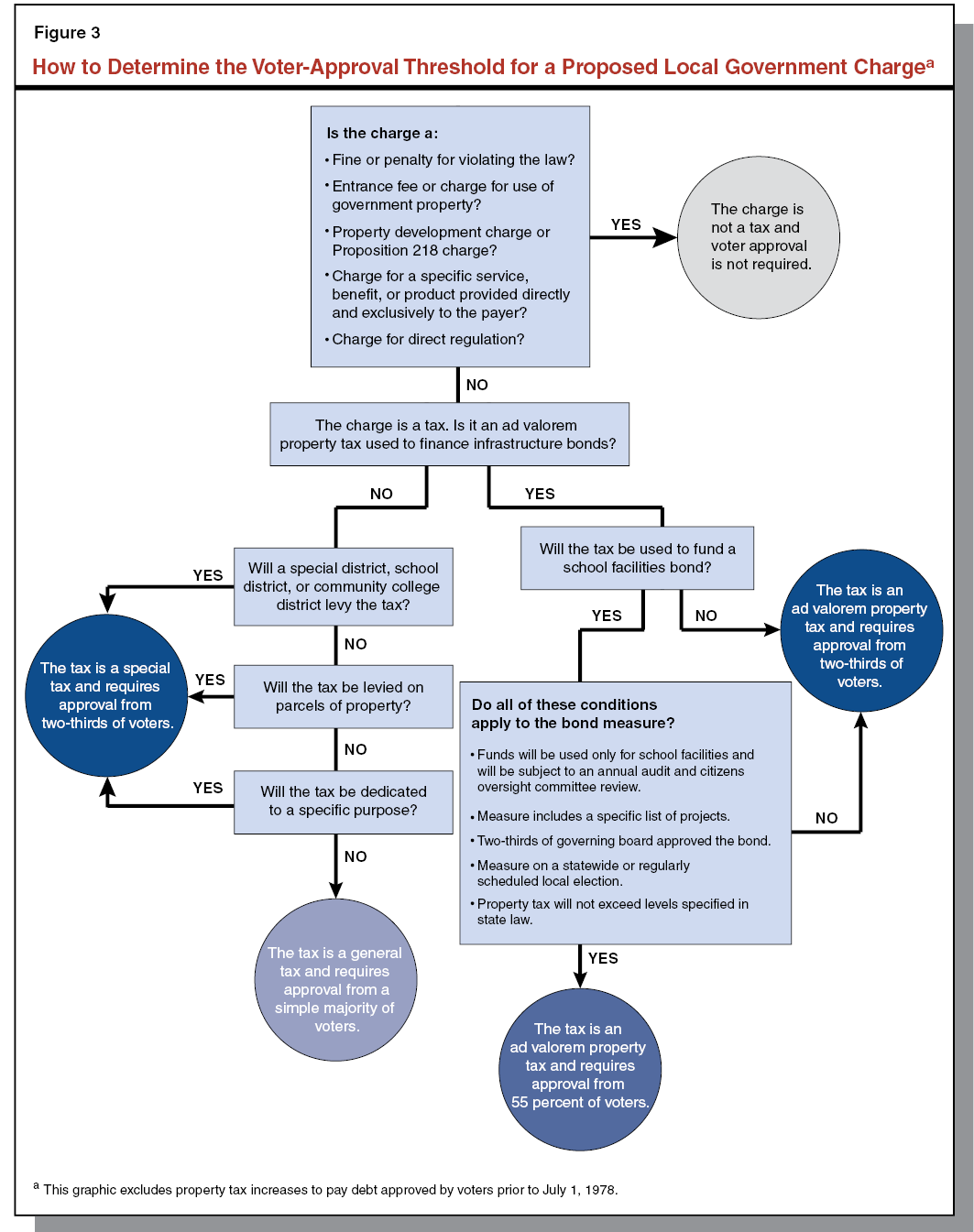

Determining the Applicable Voter–Approval Threshold

All Local Government Taxes Fall in One of Three Categories. New local government taxes generally can be placed into one of three categories: (1) property taxes to finance debt, (2) general taxes, and (3) special taxes. Each of these categories has different rules regarding voter approval. Figure 3 displays a process that can be used to determine to which of the three categories a proposed tax belongs and to determine the tax’s voter–approval requirement. Below, we define each of these categories of taxes and discuss the applicable voter–approval requirements.

Requirements Vary to Increase Property Tax for Infrastructure Bonds. As discussed above, the property tax may be raised only to (1) pay debt approved by voters prior to July 1, 1978 and (2) finance infrastructure bonds. Additional, voter approval is not required to increase property tax to pay debt approved by voters prior to July 1, 1978. Voter approval is required to increase the property tax to finance infrastructure bonds. The voter–approval requirement to raise property taxes to fund bonds depends on the type of infrastructure project to be funded. Generally speaking, property tax increases for infrastructure bonds require approval by two–thirds of local voters. Property tax increases for school facility bonds that satisfy certain conditions, however, can be approved by 55 percent of local voters. These requirements are described in more detail in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Conditions a School Facilities Bond Must Meet to Qualify for 55 Percent Voter Approval

|

|

- The bond measure includes:

|

- A requirement that the bond funds can be used only for construction, rehabilitation, equipping of school facilities, or the acquisition or lease of real property for school facilities.

|

- A specific list of projects to be funded and certification that the school district board or community college board has evaluated safety, class size reduction, and information technology needs in developing the list.

|

- A requirement that the school district board or community college board conduct annual, independent financial and performance audits until all bond funds have been spent to ensure that the bond funds have been used only for the projects listed in the measure.

|

- Two–thirds of the governing board of the school district or community college district approve placing the bond measure on the ballot.

|

- The bond measure is decided at a statewide primary, general, or special election or a regularly scheduled local election.

|

- The property tax rate levied as a result of any single election will not exceed $60 (for unified school district), $30 (for a school district), or $25 (for a community college district), per $100,000 of taxable property value.

|

- The bonds issued, when combined with other bonds issued by the district, will not exceed 1.25 percent of property value in the district or 2.5 percent of property value in unified school districts and community college districts.

|

- The governing board of the school district or community college district appoint a citizens’ oversight committee to inform the public concerning spending of the bond revenues.

|

Simple Majority Approval Is Required for General Taxes. A general tax requires approval by a simple majority of voters. (A simple majority is 50 percent of voters plus one additional voter.) A general tax is a tax (1) levied by a general purpose government—city or county—and (2) expended, at the discretion of the local government’s governing body, on any programs or services. All non–property taxes which cities and counties are authorized to levy may be imposed as general taxes.

Two–Thirds of Voters Are Required to Approve Special Taxes. Special taxes require approval from two–thirds of local voters. A special tax is a tax that meets one of the following conditions:

- Special–Purpose District Tax. All taxes—other than property taxes for infrastructure bonds—levied by special districts, school districts, and community college districts are special taxes.

- Tax Dedicated to a Specific Purpose. A city or county tax dedicated to a specific purpose or specific purposes—including a tax for a specific purpose deposited to the agency’s general fund—is a special tax. All non–property taxes that cities and counties are authorized to levy may be raised as special taxes.

- Tax Levied on Property. All taxes levied on property other than the property tax—typically parcel taxes—are special taxes.

Election Timing

State Law Establishes Official Election Dates. State law designates four dates as established election dates: (1) the second Tuesday in April in even–numbered years, (2) the first Tuesday after the first Monday in March in odd–numbered years, (3) the first Tuesday after the first Monday in June in each year, and (4) the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in each year. Statewide elections generally are held in June and November in even–numbered years. Local government elections—including elections called for voter approval of taxes—generally must be held on an established election date or at a special election called by the Governor. This requirement does not apply to:

- Elections of charter cities and charter counties (cities and counties that are governed primarily by their own charter as opposed to state law) as these local government are generally free to select their own election dates.

- Elections of school districts that have consolidated their election with a city or county.

- Elections for school facilities bond measures that are to be approved by two–thirds of local voters.

- All–mail ballot elections, which may be held on one of three dates: (1) the first Tuesday after the first Monday in May in each year, (2) the first Tuesday after the first Monday in March in even–numbered years, and (3) the last Tuesday in August in each year.

Additional Limitations Apply to Some Taxes. Local governments may call an election to seek approval of a special tax or bond measure (except for school facilities bond measures subject to a 55 percent voter–approval threshold) on any date allowed in state law or authorized in their local charters. Additional limitations, however, apply to elections for general taxes and school facilities bond measures subject to a 55 percent voter–approval threshold. General taxes must be decided at a regularly scheduled local election, except in the case of an emergency declared by a unanimous vote of the local government’s governing body. (This requirement applies to charter cities and charter counties, although these entities generally have broad authority to set the dates of their regularly scheduled elections.) School facilities bond measures subject to a 55 percent voter–approval threshold must be decided at a regularly scheduled local election or a state primary, general, or special election.

California’s voter–approval requirements for local taxes evolved over multiple decades, as can be seen in Figure 5. In this section, we discuss the major events in the evolution of voter–approval requirements for local taxes.

Figure 5

Major Milestones in the Development of Voter–Approval Requirements for Local Taxes

|

Year

|

Event

|

Significancea

|

|

1978

|

Proposition 13

|

- Lowered the property tax rate to a maximum of 1 percent (for general purposes).

- Required special taxes to be approved by two–thirds of voters.

|

|

1982

|

City and County of San Francisco v. Farrell

|

- Defined a special tax as a tax levied for a specific purpose.

|

|

1986

|

Proposition 46

|

- Allowed local governments to raise the property tax rate to finance infrastructure bonds if approved by two–thirds of local voters.

|

|

1986

|

Proposition 62

|

- Required general taxes to be approved by a simple majority of voters. (Did not apply to charter cities.)

|

|

1996

|

Proposition 218

|

- Required all general taxes to be approved by a simple majority of voters.

- Defined a special tax as all taxes (1) levied by special districts and school and community colleges districts and (2) used for specific purposes.

- Required all parcel taxes to be levied as special taxes.

|

|

2000

|

Proposition 39

|

- Lowered the voter–approval threshold for school facilities bond measures to 55 percent.

|

|

2010

|

Proposition 26

|

- Narrowed the scope of charges that local governments can levy without voter approval.

|

Prior to Proposition13, Most Taxes Could Be Raised Without Voter Approval. Local governments generally could raise or lower a tax without the assent of local voters prior to voter approval of Proposition 13 in 1978. For most local governments, the property tax was the most significant source of local tax revenue. Each local government annually determined the amount of property tax revenue necessary to finance the desired level of services and set its property tax rate—by a vote of its governing board—to collect that amount. A property owner’s property tax bill reflected the sum of the individual rates set by each taxing entity serving the property. State law provided most local governments very limited authority to levy other non–property taxes. Cities, especially charter cities, were an exception as they had greater authority to levy non–property taxes. Although voter approval generally was not required for local taxes until 1978, as discussed in the nearby box, voter–approval requirements for local government debt date back to the 19th century.

Vote Requirements for Local Debt Were Established in the 19th Century

The State Constitution of 1879 required most local governments to obtain approval from two–thirds of local voters prior to issuing long–term debt. While these requirements remain in effect today (voters relaxed these requirements for school facilities bonds in 2000), the breadth of their application has declined over time. Various types of long–term obligations commonly incurred by local governments—such as lease–revenue bonds, certificates of participation, pension obligation bonds, and pension liabilities and other retiree benefits—have not been held to be debt subject to voter–approval requirements. Long–term obligations not subject to voter–approval were far less common among local governments over a century ago than they are today.

Proposition 13 Fundamentally Altered Local Government Finance. In June 1978, California voters approved a constitutional amendment that fundamentally changed local government finance. (Proposition 13 also required state taxes to be approved by two–thirds of both houses of the Legislature. Requirements for state taxes are not discussed in this report.) Specifically, Proposition 13 lowered the aggregate property tax rate in each county to a constitutional maximum of 1 percent (plus amounts necessary to pay debt approved by voters prior to Proposition 13) and assigned responsibility for property tax allocation to the state. In effect, Proposition 13 eliminated local government control over property taxes and immediately reduced local government property tax revenues by more than 60 percent.

Voter Approval Required for “Special Taxes.” Proposition 13 also required special taxes levied by local governments to be approved by two–thirds of local voters. At the time of Proposition 13’s passage, the ramifications of this provision were unclear. Some supporters of Proposition 13 indicated that they intended special taxes to refer to all non–property taxes levied by local governments, thereby requiring all new local taxes to be approved by two–thirds of local voters. However, the measure did not explicitly define the term special taxes and different local governments interpreted this term differently. Notably, the City and County of San Francisco suggested an alternative definition of a special tax: a tax levied for a specific purpose. Based on this reasoning, in 1980 the City and County of San Francisco increased a tax on businesses for general government purposes without obtaining approval of two–thirds of voters. The legality of the new business tax was challenged—in City and County of San Francisco v. Farrell—and, in 1982, the California Supreme Court ruled in favor of San Francisco. In doing so, the Court defined a special tax as a tax levied for a specific purpose, as opposed to a tax used for general government purposes. (This ruling is hereafter referred to as the Farrell decision.) By extension, taxes levied for general government purposes, general taxes, were not subject to voter approval.

Voter–Approval Requirements Extended to General Taxes. Following Proposition 13, many cities that had historically been reliant on the property tax began to enact other non–property taxes. Business taxes, hotel taxes, and utility taxes that had comprised a small portion of city revenue prior to Proposition 13 began to comprise a growing share of city revenues. In many cases, these taxes were enacted as general taxes and, therefore, did not require voter approval. In response to this trend, in 1984 the proponents of Proposition 13 advanced another initiative constitutional amendment, Proposition 36, that would have required all local government tax increases (both general and special taxes) to be approved by two–thirds of local voters. Voters did not approve Proposition 36. Two years later, voters approved Proposition 62, which required general taxes to be approved by a simple majority of local voters. Proposition 62 also reiterated that special taxes must be approved by two–thirds of local voters. Some challenged Proposition 62 in court, arguing that it (1) constituted an unconstitutional referendum on taxes and (2) as a statutory measure, did not apply to charter cities, which derive their taxing authority from the State Constitution. In 1990, prior to the California Supreme Court ruling on Proposition 62, voters rejected a measure (Proposition 136) proposing to amend the State Constitution to require, among other provisions, simple majority voter approval of all local government general taxes. Five years later, the California Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Proposition 62, for all local governments other than charter cities.

Legislature Authorizes Local Governments to Levy Parcel Taxes. While Proposition 13 capped property taxes, it did not prohibit other levies on property owners not based on a property’s value. During the 1980s, the Legislature enacted a series of legislation that authorized local governments to levy a new type of tax on property owners: the parcel tax. Unlike the property tax which varies based on a property’s value, a parcel tax is typically set at a fixed amount per parcel (or fixed amounts per room or per square foot of the parcel). Under Proposition 13, parcel taxes are the only source of locally controlled, general purpose tax revenue for most special districts, school districts, and community college districts.

Proposition 218 Adds Voter–Approval Requirements to the State Constitution. In November 1996, voters approved Proposition 218, which added to the State Constitution a collection of voter–approval requirements for local taxes. Proposition 218 also made other important changes to local government finance, which are summarized in the box below. In several respects, Proposition 218 simply constitutionalized aspects of the voter–approval system that already existed in statute and case law. First, Proposition 218 reinforced Proposition 62’s simple majority approval requirement for general taxes. In doing so, Proposition 218 extended voter–approval requirements of general taxes to all local governments—including charter cities. Proposition 218 also largely affirmed the Farrell decision’s definition of special taxes—special taxes are those dedicated for specific government purposes. Proposition 218 established in the State Constitution that special taxes are (1) all taxes levied by special districts and school and community colleges districts and (2) taxes for specific purposes, even if the revenues are deposited in an agency’s general fund. Finally, Proposition 218 added to the State Constitution the requirement that all parcel taxes must be approved as special taxes, thereby requiring them to be approved by two–thirds of local voters. Proposition 218 also introduced a new requirement that a general tax must be presented to voters at a regularly scheduled local election, except in cases of an emergency declared by a unanimous vote of the local government’s governing body.

Proposition 218 Addressed More Than Voter Approval of Taxes

Proposition 218, a constitutional amendment approved by voters in November 1996, added to the State Constitution a collection of voter–approval requirements for local taxes. Proposition 218 also constrained the revenue–raising capacity of local governments in other ways, described below.

Tightened Approval Requirements for Property Assessments. Local governments may levy a charge, known as an assessment, on property owners to pay for a particular public improvement or service—such as flood control improvements, streets, lighting, and landscaping—that benefits the properties. Assessment rates are linked to the cost of providing the service or improvement. Proposition 218 established requirements local governments must follow to impose an assessment. First, a local government must verify that property owners would receive a specific, direct benefit from the project or service being funded by the assessment. Second, a local government must estimate the cost of providing the specific benefit to each property owner. Next, each property owner’s assessment should be set such that the assessment does not exceed his or her proportional share of total costs. Finally, the local government must notify all affected property owners by mail. Each assessment notice must contain a mail–in form for the property owner to indicate his or her approval or disapproval of the assessment. The assessment may be imposed only if 50 percent or more of these forms, weighted by the assessment amount each property owner will pay, support the assessment.

Constrained Local Government Authority to Impose Certain Fees on Property Owners. Proposition 218 limits local government authority to impose “property related fees.” This term is defined as fees imposed “as an incident of property ownership” and includes fees such as those for garbage service, sewer service, and storm water management. Under Proposition 218, revenues from these fees may not be used for a general governmental service or for a service not immediately available to the fee payer. In addition, the amount of the fee may not exceed the local government’s proportionate cost to provide the service to the property owner. Finally, Proposition 218 specifies that, before imposing or increasing these fees, the local government must (1) mail information to fee payers, (2) reject the fee if written protests are presented by a majority of the affected property owners and (3) hold an election except for fees for water, sewer, and refuse collection.

Voters Given Power to Reduce or Repeal Taxes and Other Charges Via Initiative. Proposition 218 also included a provision which expressly authorizes local residents to reduce or repeal any local tax, assessment, or fee through the initiative process.

Voters Relaxed Proposition 13’s Limit on Property Taxes. During roughly the same period that two measures (Proposition 62 and Proposition 218) were approved to expand the voter–approval requirements of Proposition 13, voters approved two measures that relaxed the Constitution’s limitations on property taxes. In June 1986, voters approved Proposition 46, which amended the provisions of Proposition 13 to allow local governments to raise the aggregate property tax rate for the purpose of financing infrastructure bonds if approved by two–thirds of local voters. (Property tax increases to fund infrastructure bonds are hereafter referred to as “bond measures.”) Following Proposition 46, three measures proposed to lower the voter–approval threshold (the proportion of voters that must approve a tax measure) for school facilities bond measures. Specifically, Proposition 170 (November 1993) and Proposition 26 (March 2000) proposed to lower the voter–approval threshold from two–thirds to a simple majority. These measures were not approved by voters. The third measure, Proposition 39, approved by voters in November 2000, lowered the voter–approval threshold to 55 percent for school facilities bond measures meeting certain conditions. Proposition 39 and legislation enacted to implement Proposition 39—Chapter 44, Statutes of 2000 (AB 1908, Lempert), as amended by Chapter 580, Statutes of 2000 (AB 2659, Lempert)—defined the conditions a bond measure must satisfy to qualify for a 55 percent voter–approval threshold. These conditions are described in Figure 4.

Proposition 26 Broadened the Definition of a Tax. It generally is easier for local governments to approve new fees—which can be imposed by a majority vote of the governing board without voter approval—than to approve new taxes. Proposition 26, approved by voters in November 2010, amended the State Constitution to recast as taxes some charges that local governments formerly could levy without voter approval. (Proposition 26 also recast as taxes certain charges that the Legislature formerly could impose as fees.) Under Proposition 26, a local government levy, charge, or exaction is a tax and subject to voter approval unless it meets at least one of seven exemptions. Figure 2 lists these exemptions.

Over the past 15 years, voters have considered over 3,000 local tax and bond measures (property tax increases to fund infrastructure bonds) under the rules described earlier in this report. In this section, we discuss the main findings of our review of the outcomes of these measures.

- The passage rate of tax and bond measures increased during the past 15 years.

- Proposition 39 led to a substantial increase in the passage rate of school facilities bond measures.

- Voter support of tax and bond measures is influenced by many factors, including location, revenue sources, use of the revenues, and election timing.

- Variation in voter–approval requirements results in variation in passage rates. Certain taxes, subject to a higher voter–approval threshold, pass less often despite receiving more yes votes.

About the Data. We compiled data from two primary sources: (1) California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission summary reports of state and local elections and (2) the California Elections Data Archive maintained by the Institute for Social Research at California State University, Sacramento. These sources provide the outcomes of most local tax and bond measure elections over the period 1998–2012. The dataset does not include information about measures proposed by special districts at local special elections.

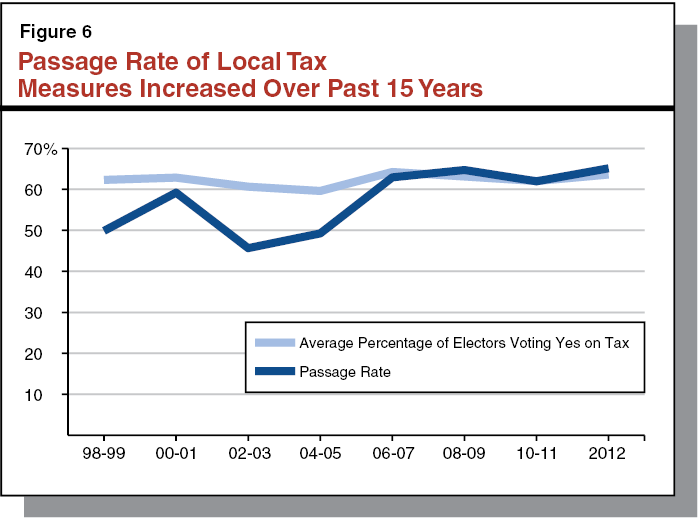

Passage Rates of Tax and Bond Measures Have Increased

Tax Measures Are Now Passing More Frequently. As Figure 6 shows, the statewide passage rate of tax measures increased over the period 1998–2012. Voters approved a little less than half of tax measures in 1998, compared with nearly two–thirds of tax measures in 2012. The increase in the passage rate of tax measures does not appear to reflect an increase in voter support for taxes because the average percent of electors voting yes for tax measures was fairly flat during this period. Instead, the upward trend in the passage rate of tax measures appears to be due to an increase in the number of proposed general taxes relative to the number of proposed special taxes. Largely because general taxes are subject to a lower voter–approval threshold, general taxes typically pass more often than special taxes.

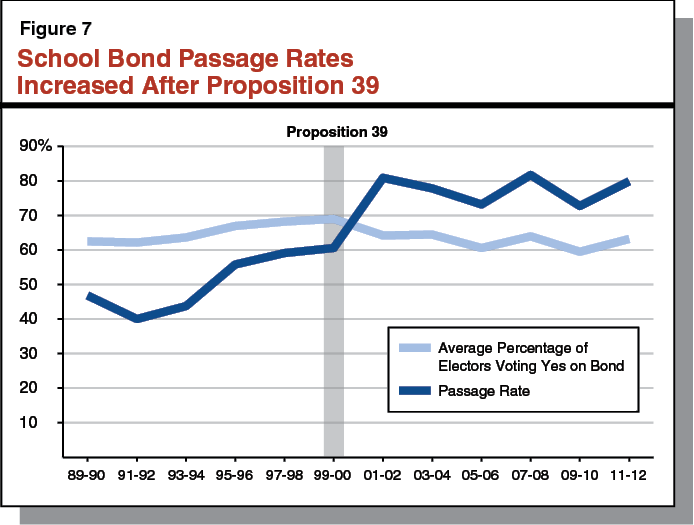

Passage Rate of Bond Measures Increased Significantly Following Proposition 39. The statewide passage rate of bond measures also increased during this period. Voters approved 58 percent of bond measures in 1998, compared with 80 percent in 2012. Similar to tax measures, the increase in the passage rate of bond measures does not appear to reflect an increase in voter support for bonds. The average percent of electors voting yes on bond measures was roughly flat during this period. Rather, the increase in the passage rate of bond measures appears to be the result of Proposition 39’s reduction in the voter–approval threshold for school facility bonds, which comprise a significant majority of local bond measures. As Figure 7 shows, the passage rate of school facilities bonds increased by almost 30 percentage points following voter approval of Proposition 39 in 2000. In the 12 years following voter approval of Proposition 39, 83 percent of Proposition 39 school facilities bonds passed, compared to 54 percent of bonds for the 12 year period prior to Proposition 39. Factors other than Proposition 39’s change in the voter–approval threshold for school facilities bonds—such changes in availability of state matching funds or the various transparency requirements for Proposition 39 school facilities bonds—could have contributed to the increase in the passage rate of these measures. However, the fact that we find no increase in the percent of yes votes received by school facilities bond measures suggests that the effect of these other factors was limited.

No Clear Trend In Passage Rate of Nonschool Bond Measures. Although the passage rate of school facilities bonds increased, we find that there was no clear trend in the passage rate of nonschool bond measures. During this period, voters approved 57 percent of nonschool bond measures.

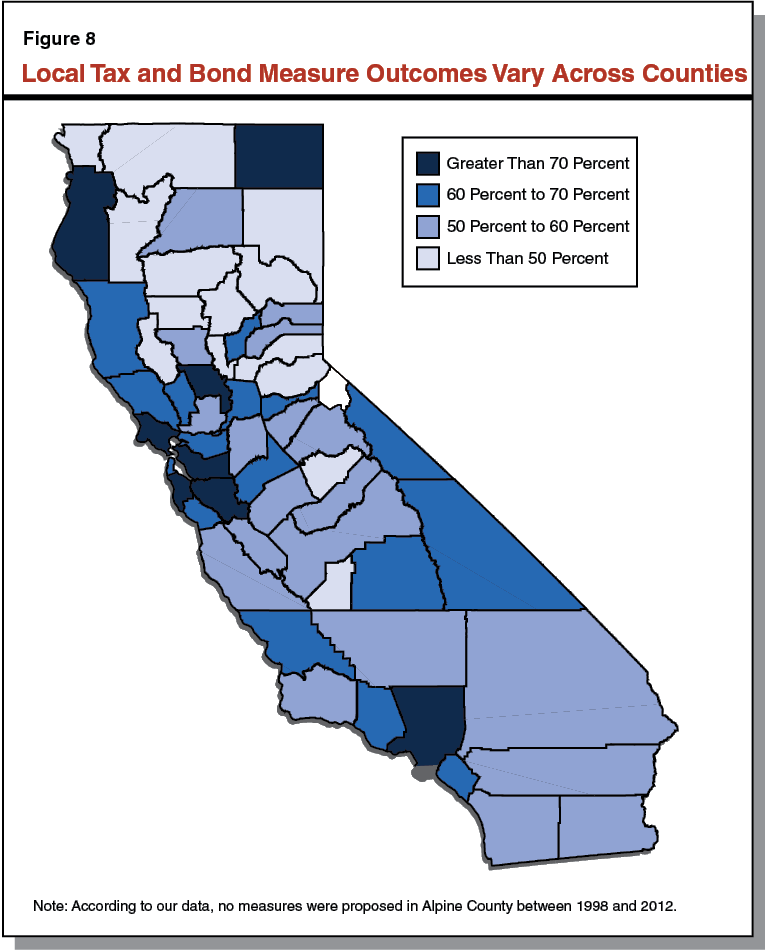

Location, Revenue Source, and Purpose Affect Passage Rates

Taxes Passed More Often in Some Counties. The passage rate of tax and bond measures varies significantly from county to county. Voters approved over 80 percent of tax and bond measures in some counties, while voters approved less than a third of measures in other counties. Figure 8 displays the passage rate for each county.

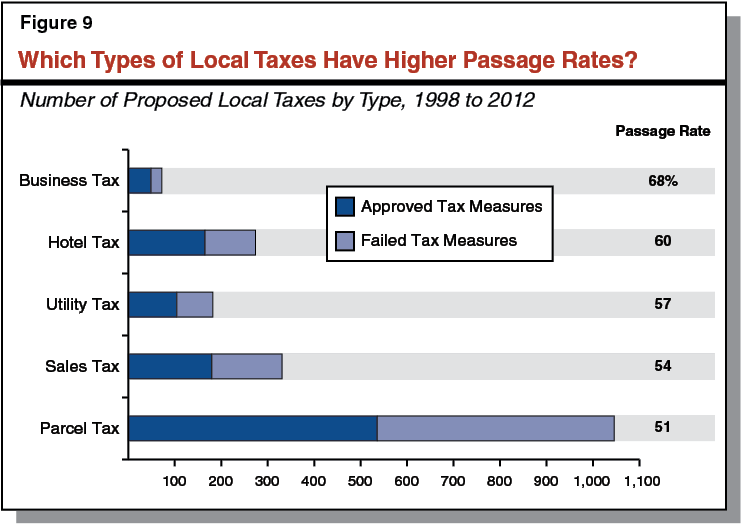

A Higher Percentage of Taxes Paid by a Narrow Group Passed Than Other Types of Taxes. Voters approved a higher percentage of taxes levied on a narrow taxpayer base—such as business taxes and hotel taxes—than other types of taxes. Figure 9 shows the number of approved and failed tax measures by revenue source. As suggested by Figure 9, the passage rates of business taxes (68 percent) and hotel taxes (60 percent) exceeded the passage rates of other major types of local government taxes, specifically utility taxes (57 percent), sales taxes (54 percent), and parcel taxes (51 percent). Although business and hotel taxes passed more often, they represent less than 20 percent of approved tax measures (in part because only cities and counties may impose these taxes). Over two–thirds of approved measures were parcel taxes and sales taxes (taxes that also may be imposed by special districts and/or schools).

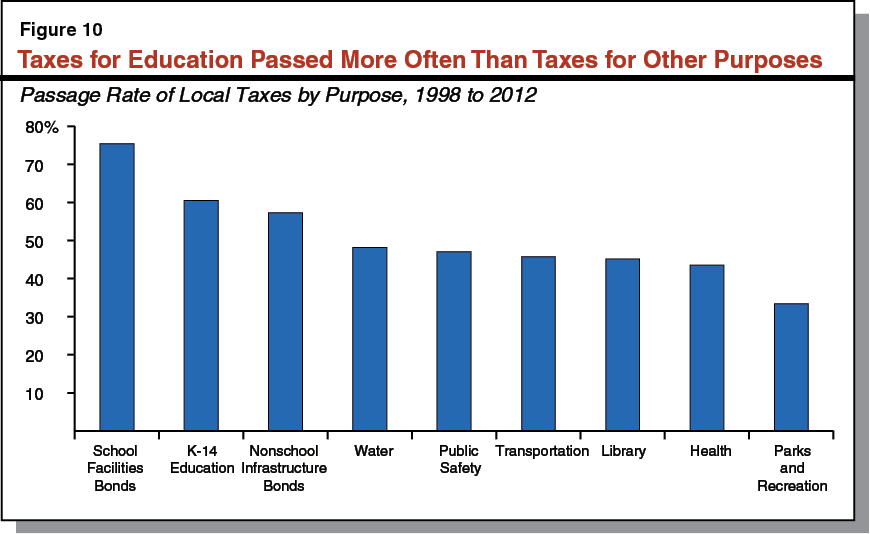

Taxes for Education Pass More Often Than Taxes for Other Purposes. Education–related tax and bond measures passed significantly more often than measures dedicated for other purposes. Figure 10 shows the passage rates of taxes dedicated to various purposes. Education–related measures also comprised a significant majority (75 percent) of approved measures.

Election Timing Affects Passage Rates

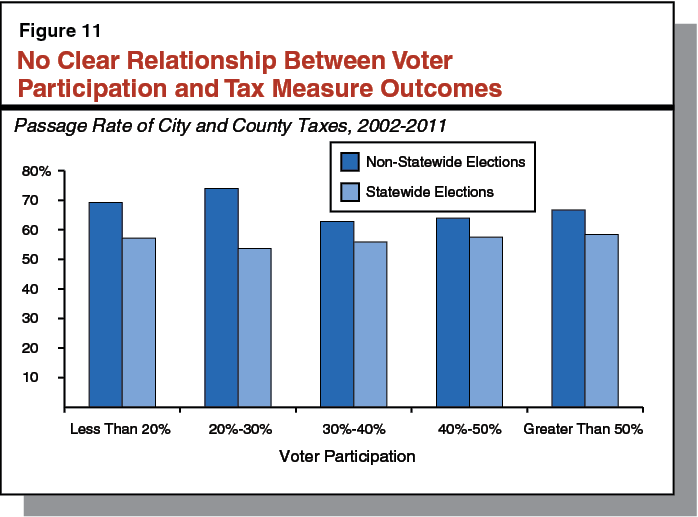

Tax and Bond Measures More Likely to Pass at Off–Cycle Elections. As discussed previously, local governments have substantial autonomy in deciding when to present tax and bond measures to voters for approval. In examining city and county tax and bond elections during the period 2002–2011, we found placing a measure on a statewide ballot significantly affected its passage rate. (This analysis is limited to cities and counties because voter registration data was not readily available for other local governments.) During this period, the passage rate of city and county tax and bond measures on a statewide ballot was 58 percent compared to 68 percent for measures not on a statewide ballot.

Voter Participation Is Higher at Statewide Elections . . . We also found that voter participation was higher for tax measures on a statewide ballot. On average, 55 percent of registered voters cast a vote on city and county tax and bond measures on a statewide ballot, compared to only 30 percent of registered voters for city and county measures not on a statewide ballot.

. . . However, Voter Participation Does Not Appear to Explain Differences in Outcomes. Differences in voter participation, however, do not appear to explain why measures on a statewide ballot are less likely to pass. Even among measures with roughly similar voter participation rates, we found that the passage rate of measures on a statewide ballot fell below measures not on a statewide ballot. For example, measures with voter participation between 20 percent and 30 percent on a statewide ballot had a passage rate of 54 percent compared to 74 percent for measures not on a statewide ballot. Additional comparisons are shown on Figure 11.

Some Taxes Passed Less Frequently Despite Being Favored by More Residents

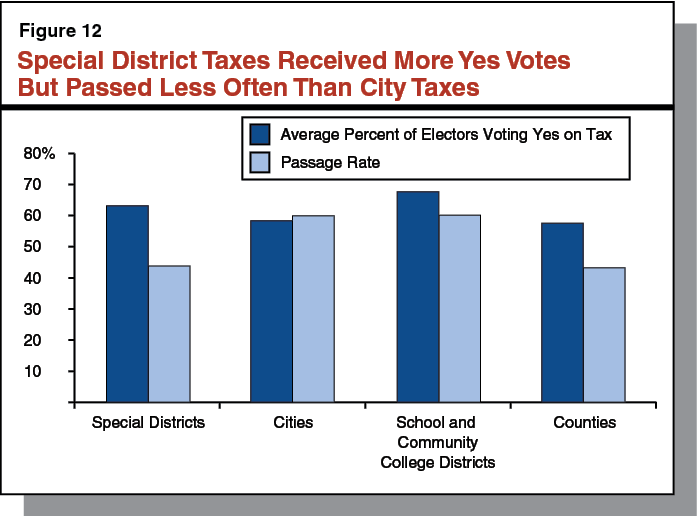

California’s voter–approval system for local taxes provides for a higher voter–approval threshold for certain types of taxes than for others. Specifically, special taxes and bond measures are subject to a higher voter–approval threshold than general taxes. Additionally, nonschool bond measures face a higher voter–approval threshold than school bond measures. One result of requiring higher approval thresholds for some taxes is that they were approved less often than other taxes despite receiving more yes votes. For example, 58 percent of electors, on average, voted in favor of city taxes, a significantly lower percent than the percent voting for special district taxes (63 percent) and school and community college district taxes (68 percent). Nonetheless, as Figure 12 shows, city taxes passed about as often as school and community college district taxes and significantly more often than special district taxes. Similarly, 63 percent of electors, on average, voted for city and county taxes for specific purposes, compared to 55 percent of electors for general taxes. General taxes, however, passed considerably more often than city and county taxes for specific purposes—18 percent more general taxes passed than special taxes.

California’s system of voter–approval requirements is complex. As described in the first section of this report, local government approval requirements vary based on many factors, including the type of local government raising the tax, the revenue mechanism, and the use of the revenues. The system has become increasingly complex in every decade since the 1970s. As discussed in the report’s second section, the current system developed in a piecemeal fashion. Neither the voters nor the Legislature have been asked to consider the current system as a complete package.

Recently, the Legislature has shown interest in exploring changes to voter–approval requirements for local taxes. In this report, we do not offer any suggested changes to the state’s system of voter–approval requirements. Nonetheless, because our analysis in the third section of this report shows that the decisions Californians make about voter–approval requirements have significant implications for local government finance, we suggest that the Legislature and voters carefully weigh the ramifications of any potential changes to these requirements.