February 20, 2015

The 2015-16 Budget:

Governor’s Criminal Justice Proposals

Overview. The Governor’s budget proposes a total of $15 billion from various fund sources for judicial and criminal justice programs in 2015–16. This is an increase of $306 million, or 2.1 percent, above estimated expenditures for the current year. The budget includes General Fund support for judicial and criminal justice programs of $11.9 billion in 2015–16, which is an increase of $308 million, or 2.6 percent, over the current–year level. In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the judicial and criminal justice area and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize our major recommendations, and provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of the report.

Inmate Medical Care. The Governor’s budget provides $76.4 million from the General Fund to the federal Receiver for additional permanent staff for the recently opened California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton to ensure adequate staffing upon full activation. We note, however, an independent assessment of CHCF found that the facility requires fewer staff than proposed in the budget. Since this assessment was conducted before the facility was fully activated, it is unclear whether all the requested positions are necessary. Accordingly, we recommend approving some positions on a one–year, limited–term basis. In order to assess whether the limited–term positions are necessary on an ongoing basis, we also recommend contracting out for an updated staffing analysis for CHCF.

The budget also includes $4.9 million from the General Fund and 30 positions to expand the Receiver’s quality management efforts in 2015–16. However, given that the Receiver’s current quality management section was found to be unnecessarily large by an independent assessment, we recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposal.

Trial Courts. The Governor’s budget includes $109.9 million in increased General Fund support for trial court operations—$90.1 million from a 5 percent base increase and $19.8 million to backfill an expected decline in fine and fee revenue in 2015–16. There are no reporting requirements for, or constraints on, the use of these funds to ensure that they will be used in a manner that is consistent with legislative priorities. To help increase legislative oversight, we recommend that the Legislature (1) provide courts with its priorities for how the funds from the augmentation should be spent and (2) take steps towards establishing a comprehensive trial court assessment program, which will help the Legislature determine whether the funding provided to the courts is being used effectively.

The administration is also proposing to address a shortfall in the Improvement and Modernization Fund (IMF), which supports projects and services benefiting trial courts. This is necessary because the Judicial Council has not sufficiently reduced expenditures from the IMF to match the decline in revenues. To address the shortfall, the administration is proposing to reduce the amount of revenue transferred out of the IMF. While we recommend reducing the amount transferred out of the IMF, we also recommend that the Legislature exercise greater oversight of its expenditures by requiring the Judicial Council to report on planned expenditures from the fund and prioritizing expenditures from the fund in statute.

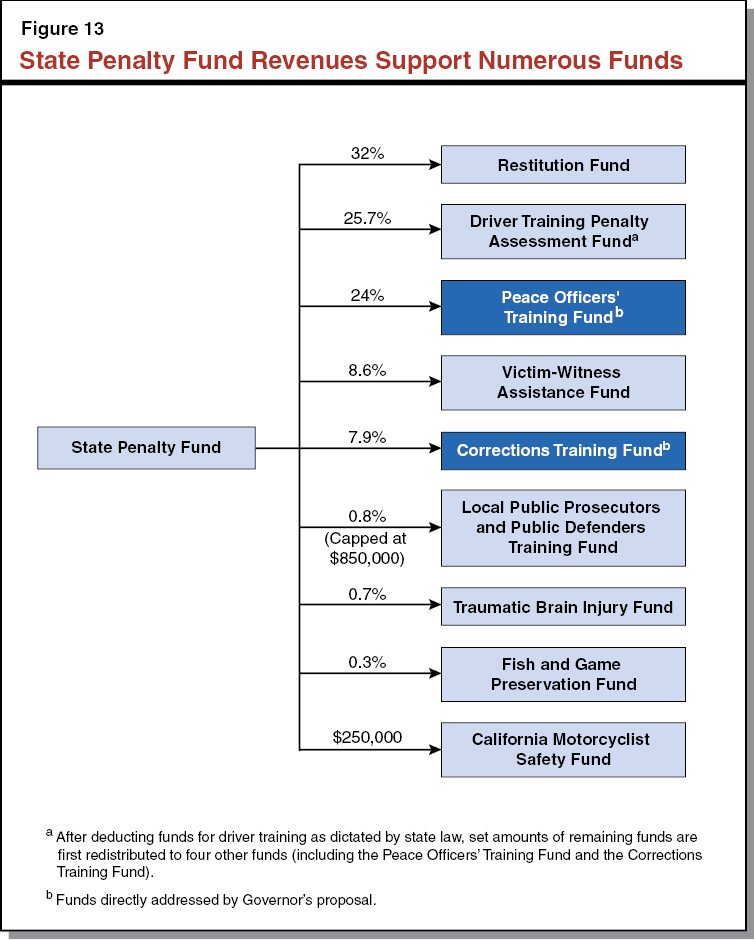

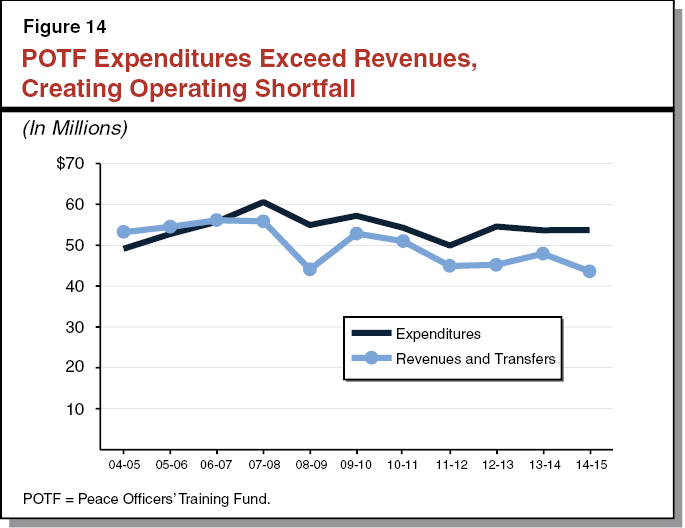

Funding for Local Law Enforcement Training. The Governor proposes several changes to address shortfalls in fine and fee revenue deposited into two state funds—the Peace Officer Training Fund (POTF) and the Corrections Training Fund (CTF)—that are used to support local law enforcement training. First, the Governor proposes a traffic amnesty program to temporarily increase fine and fee revenue to the funds. The amnesty program would allow certain individuals who are delinquent in paying their fines and fees to reduce their debt by 50 percent if they pay the reduced amount in full. In addition, the administration is proposing to restructure the expenditures from the POTF and zero–base budget the POTF and CTF, as well as the other funds that are supported by the same revenue source.

Based on our analysis, we find that the Governor’s proposed amnesty program is unlikely to raise the amount of revenue required to address the shortfalls in the POTF and CTF, and could potentially negatively affect future collections. In addition, we find it unlikely that the planned expenditure reductions from the POTF are achievable. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature: (1) reject the proposed traffic amnesty program, (2) make more targeted reductions in POTF expenditures than proposed by the Governor, (3) reduce expenditures from the CTF, and (4) approve the zero–base budgeting proposal. Given the overall decline in fine and fee revenue affecting various state funds (including the POTF and CTF), we also recommend that the Legislature consider comprehensively evaluating funds receiving fine and fee revenue and restructuring the overall process of collecting fines and fees.

The primary goal of California’s criminal justice system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, punishing individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating criminals back into the community. The state’s major criminal justice programs include the court system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and the Department of Justice (DOJ). The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of nearly $15 billion for judicial and criminal justice programs. Below, we describe recent trends in state spending on criminal justice and provide an overview of the major changes in the Governor’s proposed budget for criminal justice programs in 2015–16.

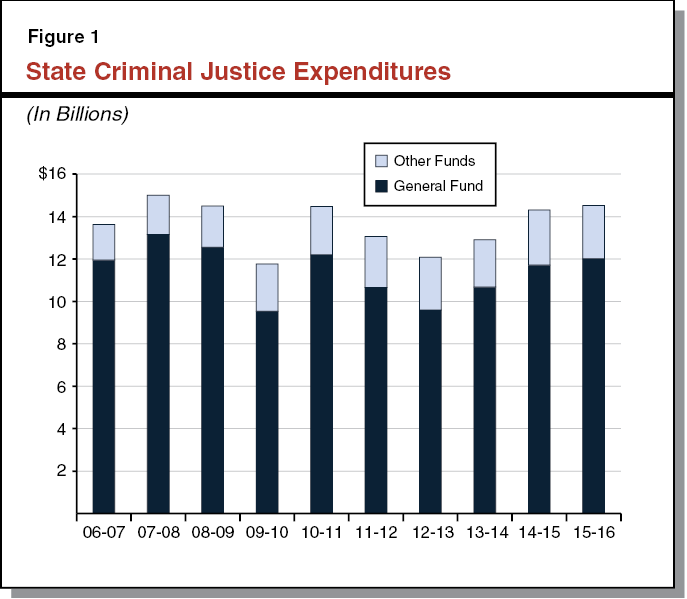

Over the past decade, total state expenditures on criminal justice programs has varied. As shown in Figure 1, criminal justice spending declined between 2010–11 and 2012–13. This is primarily due to two factors. First, in 2011, the state realigned various criminal justice responsibilities to the counties, including the responsibility for certain low–level felony offenders. This realignment reduced state correctional spending. Second, the judicial branch—particularly the trial courts—received significant one–time and ongoing General Fund reductions.

Since 2012–13, overall state spending on criminal justice programs has increased. As we discuss later in this report, this was largely due to additional funding for CDCR and the trial courts. For example, increased CDCR expenditures resulted from (1) increases in employee compensation costs, (2) the activation of a new health care facility, and (3) costs associated with increasing capacity to reduce prison overcrowding. During this same time period, General Fund augmentations were provided to the trial courts to partially offset reductions made in prior years.

As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s 2015–16 budget includes a total of $15 billion from all fund sources for judicial and criminal justice programs. This is an increase of $306 million (2.1 percent) over the revised 2014–15 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $11.9 billion in 2015–16, which represents an increase of $308 million (2.6 percent) above the revised 2014–15 level.

Figure 2

Judicial and Criminal Justice Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Actual

2013–14

|

Estimated 2014–15

|

Proposed 2015–16

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

|

$9,293

|

$10,124

|

$10,283

|

$159

|

1.6%

|

|

General Funda

|

9,173

|

9,846

|

10,008

|

162

|

1.6

|

|

Special and other funds

|

120

|

277

|

275

|

–3

|

–1.0

|

|

Judicial Branch

|

$3,067

|

$3,293

|

$3,474

|

$181

|

5.5%

|

|

General Fund

|

1,208

|

1,445

|

1,585

|

141

|

9.7

|

|

Special and other funds

|

1,859

|

1,848

|

1,888

|

40

|

2.2

|

|

Department of Justice

|

$701

|

$793

|

$793

|

—

|

—

|

|

General Fund

|

172

|

201

|

201

|

—

|

0.2%

|

|

Special and other funds

|

529

|

593

|

592

|

–1

|

–0.1

|

|

Board of State and Community Corrections

|

$111

|

$191

|

$171

|

–$20

|

–10.3%

|

|

General Fund

|

44

|

69

|

81

|

12

|

17.1

|

|

Special and other funds

|

67

|

122

|

90

|

–31

|

–25.8

|

|

Other Departmentsb

|

$229

|

$248

|

$234

|

–$14

|

–5.7%

|

|

General Fund

|

63

|

62

|

55

|

–7

|

–12.0

|

|

Special and other funds

|

166

|

186

|

179

|

–7

|

–3.6

|

|

Totals, All Departments

|

$13,401

|

$14,648

|

$14,955

|

$306

|

2.1%

|

|

General Fund

|

$10,660

|

$11,623

|

$11,930

|

$308

|

2.6%

|

|

Special and other funds

|

2,741

|

3,026

|

3,024

|

–1

|

—

|

Major Budget Proposals. The most significant proposals for new spending are related to CDCR and the judicial branch. For example, the Governor’s budget includes $71 million for CDCR for increases in salary and benefit costs, as well as various other augmentations related to various lawsuits against the department. Some of these augmentations include (1) $76 million for additional staff for the CHCF in Stockton to improve inmate medical care in response to the Plata v. Brown case, (2) $42 million to comply with a court order in the Coleman v. Brown case related to mental health care for inmates, and (3) $36 million to activate three new infill facilities to comply with a court order to reduce prison overcrowding. These augmentations are partially offset by reduced spending elsewhere in the CDCR budget, including a $72 million reduction for correctional relief staff (correctional staff who fill in for other correctional employees who are away on leave). In addition, the budget proposes various augmentations for the judicial branch, including $90 million for a 5 percent General Fund augmentation for the trial courts.

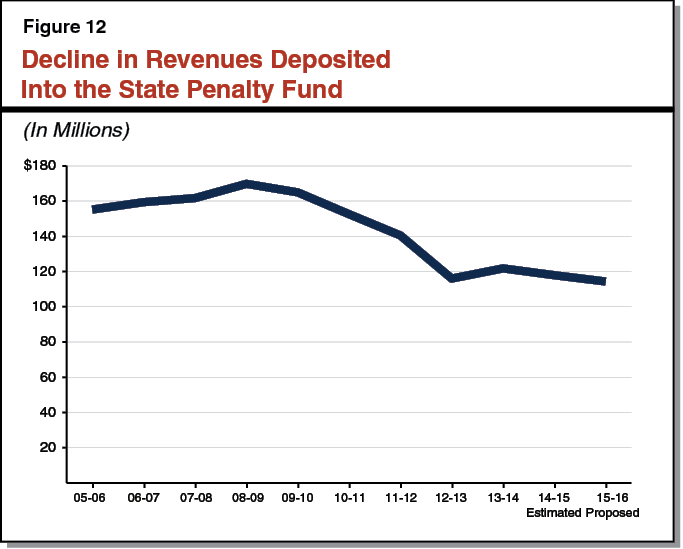

Decline in Fine and Fee Revenue Collected. The Governor’s budget includes a number of proposals to address a decline in the amount of fine and fee revenue allocated to various state funds. (Fine and fee revenue is collected from individuals convicted of criminal offenses, including traffic violations.) These proposals include: (1) additional General Fund resources to backfill fine and fee revenue that supports trial court operations, (2) structural changes to one of the judicial branch’s special funds, and (3) a proposed traffic amnesty program to address immediate shortfalls in two special funds that support local law enforcement training.

Previously, such shortfalls have sometimes been addressed through increases in fines and fees. However, this may no longer be a viable solution because recent increases have generated less additional revenue than expected. As we discuss later in this report, the Legislature may want to consider taking a more comprehensive approach towards addressing this issue before other special funds receiving these revenues become insolvent. Such steps could focus on strategically increasing revenue collections, reducing expenditures from the funds that receive fine and fee revenue, or changing how the state uses and allocates fine and fee revenue entirely.

The CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of February 4, 2015, CDCR housed about 132,000 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 34 prisons and 43 conservation camps. About 15,000 inmates are housed in either in–state or out–of–state contracted prisons. The department also supervises and treats about 44,000 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who commit new offenses or parole violations. In addition, about 700 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice, which includes three facilities and one conservation camp.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $10.3 billion ($10 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2015–16. Figure 3 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the current year and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level is an increase of $159 million, or about 2 percent, from the 2014–15 spending level. This increase reflects higher costs related to (1) employee compensation, (2) increased staffing for CHCF, (3) complying with a court order regarding the way the state handles inmates with mental illnesses, and (4) the activation of new infill bed facilities located at Mule Creek and R.J. Donovan prisons. This additional spending is partially offset by reduced spending for correctional relief staff, workers’ compensation, and a projected slight decrease in the prison population.

Figure 3

Total Expenditures for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14 Actual

|

2014–15 Estimated

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Prisons

|

$8,195

|

$8,894

|

$8,949

|

$55

|

1%

|

|

Adult parole

|

457

|

445

|

547

|

102

|

23

|

|

Administration

|

427

|

556

|

561

|

5

|

1

|

|

Juvenile institutions

|

176

|

185

|

183

|

–2

|

–1

|

|

Board of Parole Hearings

|

37

|

44

|

43

|

–1

|

–2

|

|

Totals

|

$9,293

|

$10,124

|

$10,283

|

$159

|

2%

|

The average daily prison population is projected to be about 133,000 inmates in 2015–16, a decline of roughly 1,900 inmates (1 percent) from the estimated current–year level. This decline is largely due to an estimated reduction in the inmate population resulting from the implementation of various court–ordered population reduction measures (such as increased credit earnings for certain inmates) as well as Proposition 47, which was approved by voters in November 2014. Proposition 47 reduces penalties for certain offenders convicted of nonserious and nonviolent property and drug crimes and allows certain offenders currently serving sentences for such crimes to request that the courts resentence them to lesser terms. The reduction in new prison admissions due to Proposition 47 is offset by other factors. In particular, CDCR reports an increase in the number of offenders convicted as “second strikers.” (Under the state’s Three Strikes law, an offender with one previous serious or violent felony conviction who is convicted for any new felony can be sentenced to twice the term otherwise required under law for the new conviction and must serve the sentence in state prison. These particular offenders are commonly referred to as second strikers.) The department estimates that it will receive 12,400 second strikers in 2015–16, which is an increase of 68 percent from the 2011–12 level of 7,400.

The average daily parole population is projected to remain stable at 42,000 parolees in the budget year. This is because there are factors that are projected to have offsetting influences on this population. On the one hand, the parole population is expected to continue to decline as a result of the 2011 realignment, which shifted from the state to the counties the responsibility for supervising certain offenders following their release from prison. On the other hand, this decline is completely offset by a projected increase in parolees from the implementation of court–ordered population reduction measures and Proposition 47, which will result in certain inmates being paroled early.

As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests modifications to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the prison and parole populations in the current and budget years. The administration then adjusts these requests each spring as part of the May Revision based on updated projections of these populations. The adjustments are made both on the overall population of offenders and various subpopulations (such as inmates housed in contract facilities and sex offenders on parole). As can be seen in Figure 4, the administration proposes net increases of $4.3 million in the current year and $58.5 million in the budget year.

Figure 4

Governor’s Population–Related Proposals

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

Population Assumptions

|

|

|

|

Prison Population—2014–15 Budget Act

|

135,482

|

135,482

|

|

Prison Population—2015–16 Governor’s Budget

|

134,986

|

133,109

|

|

Prison Population Adjustment

|

–496

|

–2,373

|

|

Parole Population—2014–15 Budget Act

|

41,874

|

41,874

|

|

Parole Population 2015–16 Governor’s Budget

|

41,874

|

42,003

|

|

Parole Population Adjustments

|

—

|

129

|

|

Budget Adjustments

|

|

|

|

Medical staffing adjustment

|

$12.4

|

$10.8

|

|

New inmate housing activations

|

0.9

|

41.0

|

|

Inmate–related adjustments

|

0.1

|

–7.7

|

|

Contract bed adjustments

|

–9.5

|

2.3

|

|

Other adjustments

|

0.4

|

12.1

|

|

Proposed Budget Adjustments

|

$4.3

|

$58.5

|

The current–year net increase in costs is primarily due to an adjustment to medical staffing levels to account for a technical error related to staffing. These costs are mostly offset by savings related to in–state contract beds due to a lower–than–expected population housed in such beds. The budget–year net increase in costs is largely related to (1) the activation of new infill bed facilities at Mule Creek prison in Ione and R.J. Donovan prison in San Diego, (2) a projected increase in certain populations of inmates needing mental health care, and (3) the activation of a new mental health treatment unit for condemned inmates at San Quentin prison. These increases are partially offset by a projected reduction in the inmate population.

In past years, the population projections have included the department’s estimate of what the average annual inmate population will be in each of the four fiscal years following the budget year. The department’s population projections are always subject to some uncertainty because the prison population depends on several factors (such as crime rates and county sentencing practices) that are hard to predict. However, according to the administration, this year’s projections are particularly uncertain due to the additional challenge of estimating the effects of Proposition 47 and other court–ordered population reduction measures. Due in part to this, CDCR has decided not to publish its estimate of the inmate population beyond 2015–16.

In our recent report, The 2015–16 Budget: Implementation of Proposition 47, we raise concerns that the administration may be underestimating the population impacts of Proposition 47 and thus overestimating the inmate population for 2015–16. In addition, we raise concerns with the administration’s plan for managing the state’s prison capacity following the implementation of Proposition 47. Specifically, we find that the proposed level of contract bed funding appears higher than necessary. We are also concerned that the administration has not provided the Legislature with long–term population projections, as this makes it impossible for the Legislature to make an informed decision regarding how to adjust the state’s prison funding and capacity in response to Proposition 47.

We recommend that the Legislature not approve the proposed level of contract bed funding until the department can provide additional information justifying the need for contract beds. With regard to the portions of the Governor’s proposal not related to contract beds, we withhold recommendation until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations, and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to resume its historical practice of providing long–term population projections biannually in order to assist the Legislature in determining how best to adjust prison capacity in response to Proposition 47.

2011 Realignment. In 2011, the state enacted legislation that realigned responsibility for managing certain felony offenders from the state to the counties and provided counties funding to support their new responsibilities. Specifically, the 2011 realignment limited the type of offender that could be sent to state prison and parole. These changes were expected to significantly reduce the state’s prison and parole populations, and create significant state savings.

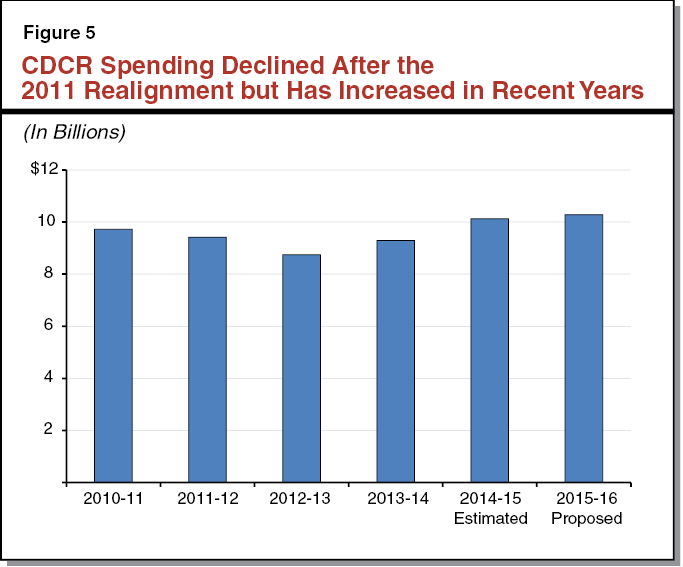

CDCR Spending Initially Declined. . . Shortly after the implementation of the 2011 realignment, CDCR released a report (referred to as the “blueprint”) on the administration’s plan to reorganize various aspects of CDCR operations, facilities, and budgets. The blueprint estimated that the state would make a total of $1.5 billion in reductions to CDCR by 2015–16 as a result of the 2011 realignment. As shown in Figure 5, expenditures for CDCR did decline following the 2011 realignment. Specifically, the department’s expenditures declined by $1 billion from 2010–11 to 2012–13—from $9.7 billion to $8.7 billion.

. . .But Has Recently Increased. However, many of the reductions made to CDCR’s budget have been offset by increased costs. Consequently, CDCR’s budget began increasing in 2013–14 and is proposed to reach a level of $10.3 billion in 2015–16—reflecting a $1.6 billion increase since 2012–13. As we discuss below, this increase is driven by increased costs associated with (1) employee compensation, (2) the activation of a new prison health care facility, (3) additional prison capacity to reduce prison overcrowding, and (4) other cost drivers.

Employee Compensation. The costs to operate CDCR’s prisons and supervise state parolees has been impacted by significant increases in employee compensation costs. For example, the department’s contribution rate for retirement for employees in peace officer classifications, including correctional officers, has increased by roughly one–third since 2012–13. In addition, the contract approved by the state in 2013 for Bargaining Unit 6 employees—most of whom are correctional officers—included several provisions that have increased CDCR’s employee compensation costs (such as a 4 percent salary increase). We estimate that the above changes account for roughly $400 million of the increase since 2012–13.

Activation of New Prison Health Care Facility. The activation of CHCF in Stockton in 2013–14 has also increased CDCR’s costs. In 2006, a federal court found that CDCR was not providing a constitutional level of medical care and appointed a Receiver to take over the direct management and operation of the state’s prison medical care delivery system. In order to address inadequacies in CDCR’s health care infrastructure identified by the court, the Receiver developed a health care facility improvement plan which included the construction of CHCF. The Governor’s 2015–16 budget includes $295 million for the operation of CHCF.

Additional Prison Capacity. Another significant driver of CDCR’s costs is the addition of prison capacity to comply with a federal court order to reduce prison overcrowding. This order was issued after the federal courts found that prison overcrowding was the primary cause of the state’s inability to deliver a constitutional level of prison medical care. In response to the order, the department has added thousands of contract beds in recent years and intends to activate three new infill facilities in 2015–16. The Governor’s proposed budget includes $495 million for contract beds in 2015–16. This represents an increase of $223 million from the 2012–13 level of $272 million and reflects an increase of nearly 6,000 contract beds over the same time period. In addition, the Governor’s budget also includes $36 million for the activation of the three new infill facilities described above.

Other Cost Drivers. The remaining increase in CDCR’s expenditures between 2012–13 and 2015–16 is due to various factors. For example, the department has incurred increased costs related to (1) lease revenue debt service, (2) the reactivation of its correctional officer academy, and (3) inmate pharmaceuticals.

The federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires all public entities to provide individuals with disabilities equal access to programs and services. In 1994, a federal court ruled in a lawsuit, Armstrong v. Brown, that CDCR was in violation of the ADA. The Armstrong court ordered the department to (1) bring its practices and institutions into compliance with the ADA and (2) ensure that disabled inmates and parolees have equal opportunity to participate in programs, services, and activities as nondisabled inmates and parolees.

In May 2014, CDCR requested $17.5 million to perform a variety of upgrades to prisons to ensure that they meet Armstrong and ADA standards. That proposal noted that future funding would be necessary to upgrade additional prisons. At that time the department submitted information justifying the proposal, such as a detailed description of the proposed projects and their costs, and the Legislature approved the request as part of the 2014–15 budget.

The administration proposes a total of $38 million from the General Fund—$19 million in 2015–16 and $19 million in 2016–17—to construct ADA improvements at 14 prisons. According to the administration, different projects may be required at each facility, which could include accessible cells, chairs, ramps, and walkways, among other changes. The proposal, however, does not identify which 14 prisons will receive modifications, nor does it provide any details about the specific projects or costs associated with each prison.

Unlike when funding was requested for ADA improvements for 2014–15, the administration’s proposal for 2015–16 currently lacks sufficient information for the Legislature to evaluate it. While the administration indicates that the proposed $19 million would support projects at 14 prisons, it has not indicated (1) which prisons will receive modifications, (2) what specific problems exist at those prisons, (3) what specific projects will be undertaken at each prison to address the associated problem, and (4) the cost of each project and potential alternatives. Moreover, according to CDCR, the department has been working with Armstrong plaintiffs to achieve compliance. Based on those discussions, the department will identify the specific projects that would be funded from this proposal. The department stated that a list of accessibility improvements is not currently available. Without this information the Legislature cannot assess whether the planned projects are the most cost–effective method of achieving ADA and Armstrong compliance.

While we recognize the need to provide ADA accessibility in all of CDCR’s prisons and be in compliance with Armstrong standards, we are concerned that the Governor’s proposal lacks sufficient detail for the Legislature to assess whether the proposed changes are appropriate and cost–effective. As such, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal and require CDCR to provide additional information at budget hearings to justify the request. This information should include (1) an update on CDCR’s discussions with Armstrong plaintiffs and how such discussions impact the department’s request and planned projects, (2) which prisons will receive renovations, (3) the existing problems in those prisons, (4) the specific projects that will be undertaken in each prison, and (5) the cost of each project and any alternatives that were considered. If the department does not provide this information to the Legislature, we would recommend rejecting the proposed funding. If, however, CDCR provides this information, our office will analyze it and make specific recommendations based on our analysis.

Background. The CHCF in Stockton was designed to provide health care for 2,951 prison inmates with more serious mental and medical conditions. According to the Receiver, centralizing such inmates in one facility would result in a more efficient delivery of health care. The Receiver has indicated that the design of CHCF makes it unprecedented in nature. The CHCF opened in fall 2013 and was initially estimated to require $82 million and 810 positions for clinical staffing when fully activated. However, admissions to the facility were halted soon after it opened as it immediately began experiencing problems. Specifically, the Receiver identified serious inadequacies in clinical and custody staffing, a lack of basic supplies, and infection outbreaks. The CHCF has since resumed admissions, and currently houses about 1,900 inmates.

Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes a General Fund augmentation of $76.4 million and 714.7 additional clinical positions in 2015–16 to ensure adequate staffing upon full activation, including primary care, nursing, and support staff. (The Receiver is also seeking a supplemental appropriation to cover the partial–year cost of the proposed staffing increase in 2014–15.) If the proposed augmentation to CHCF staffing is approved, total clinical staffing costs would increase from about $82 million annually to about $158 million annually, and staffing levels would increase from 810 positions to 1,525 positions.

Proposal Exceeds Independent Assessment Recommendations. In January 2014, the Receiver contracted with CPS HR Consulting for an independent assessment of the clinical staffing levels at CHCF. The assessment included a review of the current CHCF staffing levels and recommendations for ongoing clinical staffing levels. As part of the review, the consulting firm conducted on–site reviews of staff responsibilities and patient records. However, during the time of these visits, CHCF was less than half–filled. In July 2014, CPS HR released a report summarizing its findings and recommendations. Specifically, the report found that the current staffing levels at CHCF are inadequate and included recommendations to increase the number of staff positions by about 600. Such an increase would cost about $60 million annually.

As mentioned above, the Governor’s proposal recommends increasing staffing by 714.7 positions, at a cost of $76.4 million. This is about 100 positions and $16 million more than recommended by CPS HR. According to the Receiver’s office, this is due to several reasons. First, the Receiver’s office notes that certain services were not included in the CPS HR analysis, such as mental health group treatment. Second, the office notes that the analysis did not account for supervisory and administrative staff, which the Receiver believes are necessary to provide adequate care. Finally, the Receiver notes that because CPS HR did not visit CHCF when it was at full capacity, the analysis did not account for issues that have arisen since the facility expanded its operations. For example, the analysis did not include staffing for a mental health unit that was not open at the time the consulting group visited CHCF.

While the overall staffing levels proposed by the Receiver for CHCF are higher than the CPS HR recommendations, we note that the Receiver’s proposal excludes some positions recommended by CPS HR. For example, the Receiver’s request includes fewer certified nursing assistants than recommended by CPS HR. According to the Receiver, this is because certified nursing assistants cannot perform certain tasks like other classifications, such as licensed vocational nurses. Given the unprecedented nature of CHCF, it is difficult to assess whether deviations from the CPS HR analysis are appropriate, or whether other changes to the analysis are needed.

LAO Recommendations. Given the deficiencies in care identified at CHCF, we recommend the Legislature approve the additional clinical staffing and funding requested. However, in view of the above concerns, we recommend that only a portion of the staff be approved on an ongoing basis and the remainder on a limited–term basis. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature approve the staffing recommended by the CPS HR staffing analysis—excluding those staff the Receiver found to be unnecessary—on an ongoing basis. This amounts to about $52 million and 515 permanent positions. For the remaining positions not recommended by CPS HR, we recommend that the Legislature approve them on a one–year, limited–term basis because it is unclear whether all of these positions are necessary. This amounts to about $24 million and 200 limited–term positions.

In order to assess whether the above limited–term positions are necessary on an ongoing basis and whether care can be delivered in a more efficient manner than proposed by the Receiver, we further recommend that the Legislature require the Receiver to contract for an updated staffing analysis for CHCF. This staffing analysis, which would likely cost less than $100,000, should include (1) a review of all positions not recommended by the CPS HR analysis, and (2) whether adequate care can be delivered with fewer positions. As this analysis would be carried out after CHCF is fully activated, it would provide better information on what the ongoing staffing needs of CHCF are than the other reviews conducted to date. The results of the analysis should be provided to the Legislature in time for its consideration of the 2016–17 budget.

Background. Valley Fever is a disease caused by inhaling fungal spores found in the soil in many areas of California. Most people who get Valley Fever have few or no symptoms, but some individuals can experience severe symptoms similar to flu or pneumonia or even die. Once an individual has Valley Fever he or she cannot get it again. The fungal spores that can cause Valley Fever are particularly common in the areas surrounding Pleasant Valley State Prison (PVSP) in Coalinga and Avenal State Prison (ASP). Currently, about 500 inmates in California prisons have Valley Fever. More than 80 percent of these inmates are housed at ASP and PVSP. The Receiver spends about $23 million annually for care and treatment of inmates with Valley Fever.

In April 2013, the Receiver requested assistance from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in reducing the number of Valley Fever cases. In July 2014, the CDC recommended several options for the Receiver to consider. For example, the CDC recommended excluding from placement at ASP and PVSP inmates who do not have Valley Fever. Under this policy, inmates who test negative for Valley Fever would be excluded from placement at ASP or PVSP, while inmates who test positive would be eligible to be housed at ASP or PVSP. The rationale is that excluding inmates who test negative from placement at ASP or PVSP could eventually reduce Valley Fever cases by about 60 percent, as such exclusion would reduce their likelihood of obtaining Valley Fever.

Governor’s Proposal. Accordingly, the Receiver recently spent $5.4 million on sufficient supplies to test 90,000 inmates for Valley Fever. On January 12, 2015, the tests were administered to roughly 30,000 consenting inmates. The Receiver is seeking a supplemental appropriation in the current year to cover the costs of the medical supplies already purchased. In the future, the Receiver will administer Valley Fever skin tests to all new inmates entering the prison system who are eligible for placement at ASP and PVSP. The Receiver anticipates that savings from not treating Valley Fever in the future would offset future testing costs.

Proposal Does Not Account for Future Savings. According to the Receiver, the potential reduction in the number of inmates with Valley Fever will likely generate some medical care–related savings in 2015–16 and thereafter. However, the Governor’s budget does not reflect any potential savings. Given that the Receiver spends $23 million on Valley Fever treatment each year and the CDC estimates that its recommendations could decrease Valley Fever cases by 60 percent, the Receiver could eventually see a reduction in treatment costs of around $14 million annually within a few years. Though the proposal indicates that savings could be used to fund ongoing testing, such testing is only estimated to cost a couple million dollars annually. In addition, the Receiver used only about one–third of testing supplies it purchased. According to the Receiver’s office, they will use those tests for their ongoing testing, which would reduce the ongoing costs associated with Valley Fever in the budget year. Despite these considerations, the administration has not provided information on how any additional savings would be used.

LAO Recommendation. We do not have concerns with the Receiver having tested inmates for Valley Fever in January of this year. However, we are concerned that the Governor’s proposal does not account for all the savings associated with implementing an ongoing Valley Fever testing process. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature request that the Receiver report at budget hearings this spring on (1) the amount of annual savings from reductions in the number of inmates with Valley Fever and (2) how he plans to account for these savings in the budget year and on an ongoing basis. This would ensure the Legislature has sufficient oversight of the Receiver’s budget, and that any savings as a result of Valley Fever testing are spent in a way that is consistent with the Legislature’s priorities.

Background. In June 2008, the federal court approved the Receiver’s “Turnaround Plan of Action” to achieve a sustainable constitutional level of medical care. The plan identified six major goals for the state’s inmate medical care program, including specific objectives and actions for each goal. One of the identified goals was to implement a quality assurance and continuous improvement program to (1) track prison performance on a variety of measures (such as access to care), (2) provide some training and remedial planning (for example, developing a plan to improve access to care at a prison that is struggling to meet that goal), and (3) share best practices across prisons, among other tasks.

Currently, the quality management section within the Receiver’s office has 32 positions and a budget of $3.9 million. In addition, there are also 170 staff statewide (5 positions at each prison) who are involved in quality management activities. These staff include psychologists, managers, and program specialists who perform quality management functions as well as other responsibilities. According to the department, about 90 percent of their time is devoted to quality management activities.

Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes $4.9 million from the General Fund and 30 positions to expand the Receiver’s quality management efforts in 2015–16. Of the additional staff being requested, 20 positions are to develop quality management programs in the Receiver’s new regional offices. Regional staff would be responsible for overseeing prisons located within their geographic area of responsibility. Similar to existing quality management staff, these requested staff would be responsible for tracking prison performance, identifying areas where medical care is deficient, developing performance improvement plans, and sharing best practices across prisons.

Independent Review Raised Concerns About Receiver’s Quality Management Section. In 2012, the Receiver contracted with Health Management Associates (HMA) for a review of the structure of the Receiver’s office. In February 2013, HMA released its analysis and recommendations. The analysis recommended several changes to the Receiver’s quality management section, including reassigning many of the staff to other activities. According to HMA, the size of the quality management section in the Receiver’s office far exceeded that in any other prison or health care system of a similar scale. At the time HMA found the quality management section to be overstaffed, it had 24 staff. Under the Governor’s proposal, the section would have 62 staff. This does not include the 170 additional staff that spend a majority of their time on quality management activities at the state’s 34 prisons.

Proposal Exceeds Community Standard. Private health insurance plans generally spend about 0.7 percent of their budget on quality management activities. Currently, the Receiver’s office spends about 0.25 percent of their budget on the headquarters quality management section. However, including the prison–level quality management staff, the Receiver’s office currently spends about 1.3 percent of their budget on quality management—more than double the spending of private health plans. If the Governor’s proposal was approved, the Receiver’s office would spend about 1.6 percent of its budget on quality management.

LAO Recommendation. Given that the Receiver’s quality management section was found to be unnecessarily large in an independent assessment and is already larger than the community standard, we find no compelling reason at this time to expand the Receiver’s quality management staff. Thus, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal.

Judicial Branch Budget. The judicial branch is responsible for the interpretation of law, the protection of an individual’s rights, the orderly settlement of all legal disputes, and the adjudication of accusations of legal violations. The branch consists of statewide courts (the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal), trial courts in each of the state’s 58 counties, and statewide entities of the branch (the Judicial Council, Judicial Branch Facility Program, and the Habeas Corpus Resource Center). The branch receives revenues from several funding sources including the state General Fund, civil filing fees, criminal penalties and fines, county maintenance–of–effort payments, and federal grants.

Figure 6 shows total funding for the judicial branch from 2011–12 through 2015–16. Although total funding for the branch declined between 2011–12 and 2012–13—primarily due to significant reductions in the level of General Fund support—it has steadily increased since then and is proposed to increase in 2015–16 to $3.7 billion.

As shown in Figure 7, the Governor’s budget proposes $3.5 billion from all state funds to support the judicial branch in 2015–16, an increase of $181 million, or 5.5 percent, above the revised amount for 2014–15. (These totals do not include expenditures from local revenues or trial court reserves.) Of the total budget proposed for the judicial branch in 2015–16, about $1.6 billion is from the General Fund—43 percent of the total judicial branch budget. This is a net increase of $141 million, or 9.7 percent, from the 2014–15 amount.

Figure 7

Judicial Branch Budget Summary—All State Funds

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14

Acutal

|

2014–15

Estimated

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

Change From 2015–16

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

State Trial Courts

|

$2,437

|

$2,538

|

$2,702

|

$163

|

6.4%

|

|

Supreme Court

|

43

|

46

|

46

|

—

|

0.3

|

|

Courts of Appeal

|

205

|

216

|

217

|

—

|

0.2

|

|

Judicial Council

|

133

|

140

|

135

|

–5

|

–3.7

|

|

Judicial Branch Facility Program

|

236

|

339

|

361

|

22

|

6.6

|

|

Habeas Corpus Resource Center

|

13

|

14

|

14

|

—

|

0.1

|

|

Totals

|

$3,067

|

$3,293

|

$3,474

|

$181

|

5.5%

|

Trial Courts Budget. The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 proposes a total of $2.7 billion in state funds for the trial courts, including $1.2 billion from the General Fund. This amount reflects a proposed $179.5 million ongoing General Fund augmentation for trial courts. This increase includes:

- $90.1 million for trial court operations, which reflects the second year of a two–year funding plan that provides a 5 percent General Fund augmentation that was initially approved as part of the 2014–15 budget.

- $42.7 million for increased trial court health benefit and retirement costs.

- $26.9 million in 2015–16 and $7.6 million in 2016–17 to process resentencing petitions from offenders currently serving felony sentences for crimes that Proposition 47 (2014) reduces to misdemeanors. (In our recent report, The 2015–16 Budget: Implementation of Proposition 47, we recommend that the Legislature approve the amount requested for 2015–16, but not for 2016–17 pending additional data on the actual impacts on court workload.)

- $19.8 million for trial court operations to backfill an expected decline in fine and fee revenue to the Trial Court Trust Fund (TCTF) in 2015–16. In addition, the Governor’s budget proposes to make the one–time $30.9 million General Fund backfill provided in the 2014–15 budget ongoing. (According to the judicial branch, an additional $11.1 million is needed to fully address the shortfall in fine and fee revenue in 2014–15. As a result, trial courts will likely use part of the General Fund base augmentation provided in 2014–15 to essentially backfill the remaining shortfall—thereby reducing the level of resources available to increase service levels.)

As indicated above, the Governor’s budget includes $109.9 million in increased General Fund support for trial court operations—$90.1 million from a 5 percent base increase and $19.8 million to backfill an expected decline in fine and fee revenue in 2015–16. The Governor’s budget includes no constraints on the use of these funds. As we discuss below, the availability of the additional General Fund support will impact individual trial courts differently due to the continued implementation of two recently adopted policies that affect trial court operations—the Workload Allocation Funding Methodology (WAFM) and the new trial court reserves policy.

Increased Percentage of Funding Allocated Under WAFM. In April 2013, the Judicial Council approved a new methodology—known as WAFM—to allocate funding to individual trial courts based on workload instead of the historic share of statewide allocations received by each court. This reallocation of funds is intended to address historic funding inequities amongst the trial courts by redistributing funds among courts based on workload. In 2013–14, the Judicial Council began to phase in WAFM over a five–year period. Under this plan, a greater percentage of the funds used to support base operations are allocated through WAFM each year. For example, in 2015–16, the percentage of funding that will be allocated under WAFM increases from 15 percent to 30 percent, with the remaining 70 percent allocated under the old methodology. However, the judicial branch intends to allocate any augmentations provided for trial court operations (such as the $90.1 million base increase proposed for 2015–16) based on WAFM, unless the funding is provided for a specified purpose.

Courts With Less Funding Relative to Workload Will Benefit More. Since an increasing percentage of base trial court operations funding will be allocated based on workload rather than historic shares of allocation, funding will essentially be redistributed among courts. Specifically, those courts that historically have had more funding relative to their workload will experience a reduction in their base funding. In contrast, courts with less funding relative to their workload will receive additional funding, which could lead to increased levels of service. Moreover, given that all of the proposed $90.1 million augmentation, as well as an equal amount of base funding, will be allocated under WAFM, courts that historically have had more funding relative to their workload will benefit less from the augmentation, while other courts will benefit comparatively more.

Restrictions on Retaining Reserves. As part of the 2012–13 budget package, the Legislature approved legislation to cap the amount of reserves (unspent funds from prior years) that could be retained by individual trial courts at 1 percent of their prior–year operating budget—approximately $24.8 million at the beginning of 2014–15. Trial courts were previously permitted to retain unlimited reserves and use such funds to help them avoid cash–flow issues, address budget reductions and unanticipated cost increases, and plan and fund future projects. Reserves also provided individual courts with an incentive to operate more efficiently as they would be able to keep any savings that could be used for other purposes in the future. Under the reserves policy, courts are permitted to exclude from the 1 percent cap monies that can only be used for specific purposes defined in statute (such as children’s waiting rooms) or were encumbered prior to the enactment of the cap. A total of $190.5 million was excluded from the cap at the beginning of 2014–15.

In addition, a statewide reserve was also created in 2012–13, which consists of a withholding of 2 percent of the total funds appropriated for trial courts in a given year. This fund is used to address unforeseen emergencies, unanticipated expenses for existing programs, or unavoidable funding shortfalls. Any unexpended funds are distributed to the trial courts on a prorated basis at the end of the year. Under the Governor’s budget, $39.8 million would be withheld in the statewide reserve in 2015–16.

Increased Funding Could Be Used to Backfill Reserves Spending. How trial courts used their reserves in prior years could potentially impact how they will use any additional General Fund support provided in the budget year. For example, courts that used their reserves to implement changes that helped them become more cost–effective (such as by replacing aging technology or implementing new processes like electronic filing) will likely be able to use more of their augmentation for increasing services to the public. In contrast, courts that used their reserves as a one–time solution to address their budget reductions or that now need to address large one–time costs (such as replacing old case management systems) may have less funding available to increase services to the public. This is because these courts may have to use some of the increased funding to maintain existing service levels that were previously supported by their reserves.

As discussed previously, the Governor’s budget includes no constraints for the use of the proposed General Fund augmentation for trial court operations. There is also no requirement for trial courts to report on how they will use the funds. As a result, the Legislature has no assurance that the proposed funds will be used in a manner consistent with its priorities—particularly given that the funds will impact individual trial courts differently due to the continued implementation of WAFM and the new trial court reserves policy. To help increase legislative oversight, we recommend that the Legislature (1) provide courts with its priorities for how the funds from the augmentation should be spent and (2) take steps towards establishing a comprehensive trial court assessment program.

Define Legislative Funding Priorities for Use of Funds. As discussed above, the Governor’s proposal to provide $109.9 million in increased General Fund support for trial court operations reflects the continued implementation of policies enacted by the Legislature as part of the 2014–15 budget. However, we recommend that the Legislature (1) establish priorities for the use of the increased funding (such as for restoring access to court services) and (2) require that courts report on the expected use of the funds prior to allocation and on the actual use of the funds near the end of 2015–16. Such information would allow the Legislature to conduct oversight to ensure that the additional funds provided are used to meet legislative priorities.

Establish Comprehensive Trial Court Assessment Program. Currently, there is insufficient information to assess whether trial courts are using the funding provided in the annual budget effectively. This makes it difficult for the Legislature to ensure that (1) certain levels of access to court services are provided, (2) trial courts use their funding in an effective manner, and (3) funding is allocated and used consistent with legislative priorities. Thus, we recommend that the Legislature take steps towards establishing a comprehensive trial court assessment program for the trial courts. (We initially made such a recommendation in our 2011 report, Completing the Goals of Trial Court Realignment.) While the judicial branch collects some statewide information related to certain measures of trial court performance (such as the time it takes a court to process its caseload), it currently lacks a comprehensive set of measurements for which data is collected consistently on a statewide basis.

In developing these comprehensive performance measures, we recommend that the Legislature—in consultation with the judicial branch—specify in statute the specific performance measures it believes are most important and require that data be collected on such measures. For example, other states and local courts have implemented all or parts of CourTools—performance measures developed by the National Center for State Courts. (Please see the nearby box for a more detailed description of CourTools.) After specific measurements are established, the Legislature would then be able to establish a system for holding individual courts accountable for their performance relative to other courts. Such an accountability system would allow the establishment of (1) a specific benchmark that the courts would be expected to meet for each measurement and (2) steps that would be taken should the court fail to meet the benchmark over time (such as by requiring the court to adopt the practices of those courts that were successful in meeting the same performance benchmark).

CourTools is a series of performance measures developed by the National Center for State Courts (NCSC)—an independent, nonprofit organization that provides research, information, training, and consulting to help courts administer justice in a cost–effective manner. CourTools offers trial courts a series of ten performance measures that were developed by applying best practices from performance measurement systems used in the public and private sectors to the judicial branch. These measures are designed to provide court administrators, policymakers, and members of the public with indicators to determine if trial courts are achieving operational goals (such as access to the courts, perceptions of fairness, timeliness in processing workload, and managerial effectiveness). The NCSC also provides detailed step–by–step implementation guides that include detailed templates for capturing information for the implementation of CourTools.

Specifically, CourTools measures:

- User and Employee Satisfaction. CourTools measures capture (1) court users’ opinions about their ability to access court services as well as their perceptions about how fairly or respectfully they were treated and (2) court employees’ opinions about their satisfaction with their work environment and their relationship with management.

- Court Performance. CourTools also measures courts performance by tracking: (1) how quickly courts process and resolve incoming caseloads, (2) the percentage of cases that are processed within established time frames, (3) the number of days that have passed since a case was filed, and (4) the number of times cases that are ultimately resolved by a trial were scheduled for trial.

- Administrative Efficiency. CourTools measures the administrative efficiency of trial courts. Specifically, it measures: (1) the ability of the court to retrieve case files within certain established time frames and that such files meet standards for completeness and accuracy, (2) the ability of courts to collect and distribute payments to address monetary penalties, (3) how effectively courts manage the number of jurors called to report for services, and (4) the average cost of processing a single case by case type.

A comprehensive set of performance measures would allow the Legislature to provide greater oversight over trial courts. First, the Legislature would have more information on whether courts are using their funds effectively and efficiently. The measures would also provide necessary information to help the Legislature decide whether additional resources or statutory changes are needed for the trial courts to meet the service levels it expects. Additionally, the comprehensive measures can help the Legislature ensure that trial courts balance public access to court services, efficient operations, and employee satisfaction. For example, in setting benchmarks for measuring court users’ satisfaction for accessing the courts and how quickly courts process cases, the Legislature can assess whether additional funding provided to the trial courts actually results in higher public satisfaction with the service provided by the courts.

Two Separate Judicial Branch Funds. In 1997, the state took significant steps towards shifting responsibility for trial courts from counties to the state. For example, Chapter 850, Statutes of 1997 (AB 233, Escutia and Pringle), transferred financial responsibility for trial courts (above a fixed county share) to the state. Chapter 850 also established the following two special funds to benefit trial courts, which, as we discuss later, were consolidated in 2012.

- Judicial Administration Efficiency and Modernization Fund. The purpose of this fund was to promote projects designed to increase access, efficiency, and effectiveness of the trial courts. Such projects included judicial or court staff education programs, technological improvements, incentives to retain experienced judges, and improvements in legal research (such as through the use of technology). The fund received monies primarily from a General Fund transfer to the judicial branch. Beginning in 2008–09, the fund received approximately $38.7 million annually. In recent years, some of these funds were redirected to help offset reductions to the trial courts.

- Trial Court Improvement Fund. The purpose of this fund was to support various projects approved by the Judicial Council. The fund received monies from (1) fine and fee revenue from criminal cases and (2) a transfer of 1 percent of the amount appropriated to support trial court operations from the TCTF. (The TCTF provides most of the funding to support trial court operations.) While the Judicial Council had significant flexibility regarding the expenditure of monies in the fund, some of the monies were restricted for specified uses. For example, a portion of the fine and fee revenues had to be used for the development of automated administrative systems (such as accounting, data collection, or case processing systems). State law also required that some of these funds be redirected back for allocation to trial courts for court operations.

While the Legislature would appropriate a set amount of funding from the Judicial Administration Efficiency and Modernization Fund and the Trial Court Improvement Fund each year in the annual state budget, Judicial Council was responsible for approving and allocating monies to specific projects or programs. Accordingly, the Legislature’s role in determining how the funds were used was limited.

Two Funds Merged Into New IMF. Chapter 41, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1012, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), merged the Judicial Administration Efficiency and Modernization Fund with the Trial Court Improvement Fund into the new IMF. While there are some differences between the IMF and the previous two funds, there are many similarities.

- Revenues. The IMF retained all sources of revenue associated with the two prior funds, such as fines and fees from criminal cases.

- Fund Transfers. As discussed above, various monies were required to be transferred into and out of the two funds. The IMF maintains these various transfers. For example, the IMF is required to annually transfer a portion of its revenues to the TCTF.

- Expenditures. While the Legislature appropriates a total amount of funding from the IMF in the state budget, the Judicial Council generally has even more discretion in how the funds are allocated to specific projects and activities than previously. Except for a couple requirements (such as one that requires a certain portion of the fine and fee revenue be used for the development of automated administrative systems), none of the statutory purposes that applied to the two previous funds (such as to improve legal research through the use of technology) currently apply to the IMF. The judicial branch is only required to provide an annual report to the Legislature on the expenditures from the IMF.

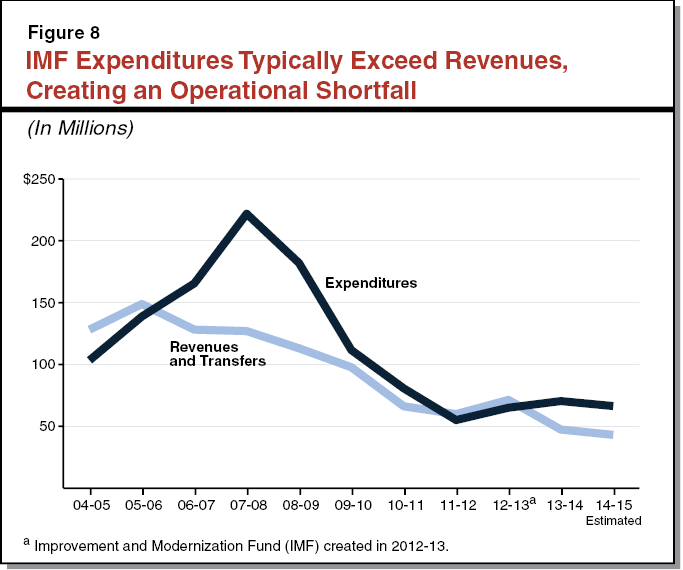

Persistent Operational Shortfalls. Prior to the establishment of the IMF in 2012–13, the combined revenues and transfers of the prior two funds generally did not cover their expenditures, as shown in Figure 8. Upon the consolidation of the two funds into the IMF in 2012–13, these shortfalls continued, steadily reducing the IMF’s fund balance. In the current year, the IMF is estimated to have combined revenues and transfers of approximately $43 million and expenditures of approximately $66 million. This will largely deplete the IMF fund balance, which will be $3 million going into 2015–16. As we discuss below, these shortfalls in the IMF result from (1) declines in fine and fee revenue deposited into the IMF and (2) spending decisions made by Judicial Council that did not fully reflect the decline in revenue.

Decline in Fine and Fee Revenue. During court proceedings, trial courts typically levy a monetary punishment—consisting of fines, fees, penalty surcharges, assessments, and restitution—upon individuals convicted of criminal offenses (including traffic violations). When partial payments are collected from an individual, state law specifies the priority order in which the partial payments are to be allocated to various state and local funds. In cases where full payment is not made, funds that are a lower priority (such as the IMF) receive less revenue than those funds that are a higher priority (such as victim restitution or reimbursement for certain collection activities).

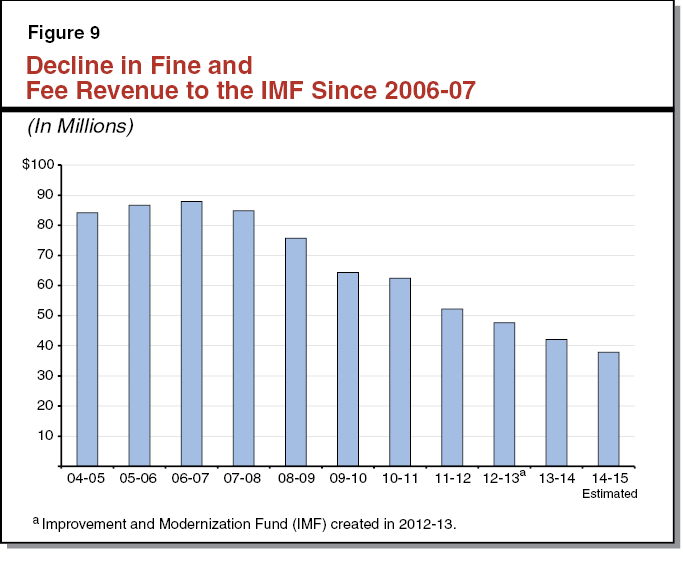

As shown in Figure 9, fine and fee revenues deposited in the IMF and its predecessor funds peaked at $88 million in 2006–07 and steadily declined since to an estimated $38 million in 2014–15—a drop of 57 percent. The specific causes of this decline are likely due to two reasons. First, there may have been a reduction in collections of the fine and fee revenues allocated to the IMF. For example, law enforcement could be writing fewer tickets for traffic violations or judges may be waiving more fines and fees—thereby reducing the amount of debt available for collection. Second, even if the total amount of fine and fee collections had remained the same, state and local funds that are a higher priority in the distribution of fine and fee payments may have been receiving an increased share of the revenue compared to the IMF.

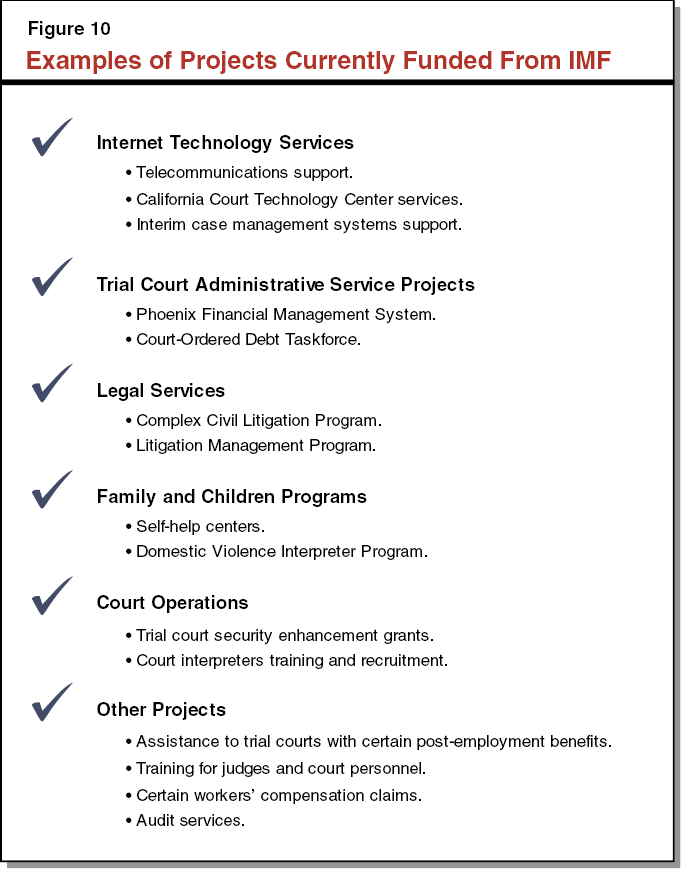

Judicial Council Authorized More Expenditures Than Available Revenues. As discussed above, state law authorizes Judicial Council to allocate funds from the IMF, as well as its predecessor funds, to specific projects and programs with very little legislative oversight. Once annual revenue into the IMF began declining, the Judicial Council struggled to reduce expenditures to match the amount of available resources. Although the council took some steps to address the operational shortfalls by eliminating or reducing funding for certain projects, or shifting projects to other fund sources, it continued to authorize funding for projects and services in excess of available resources. As shown in Figure 10, funding is provided to a wide array of one–time and ongoing projects and services. For example, in 2013–14, the IMF supported nearly 60 one–time and ongoing projects or services totaling approximately $70 million.

To help address the immediate insolvency of the IMF, the Governor’s budget proposes to end an annual $20 million transfer from the IMF to the TCTF that was first approved as part of the 2011–12 budget package to help offset trial court budget reductions. This would provide the IMF with additional resources beginning in 2015–16. (We note that the Governor’s budget does not propose backfilling the $20 million reduction to the TCTF.) In addition, the budget proposes shifting $6.3 million in costs for supporting the California Case Management System Version 3 (CCMS V3) from the TCTF to the IMF. (The CCMS V3 is a civil, small claims, probate, and mental health case management system currently used by five trial courts.) This means that $6.3 million of the additional resources freed by the terminated TCTF transfer will be used to address these added costs. Thus, the Governor’s proposal would result in a net increase of $13.7 million in IMF resources.

Increase Legislative Control of IMF Expenditures. The Governor’s proposal is a step in the right direction because it helps address the short–term insolvency of the IMF. Specifically, it frees up additional resources in the IMF to help address the operational shortfall in 2015–16. Under the Governor’s proposal, the judicial branch would be required to reduce expenditures by an estimated $13 million to maintain solvency of the IMF in 2015–16. To help ensure that the expenditures from the IMF are more closely aligned to available revenues, we recommend that the Legislature provide greater oversight and direction over such expenditures. As discussed earlier, the Legislature currently authorizes Judicial Council to make all decisions on the projects funded by the IMF and only receives an annual report on expenditures once the fiscal year is complete. At a minimum, we recommend the Legislature require the judicial branch to provide a spending plan for the use of IMF monies prior to appropriation of the total amount of IMF funds in the annual state budget. This would provide the Legislature with an opportunity to review the proposed expenditures from the fund and determine the extent to which they are aligned to its priorities and the expected revenue to the IMF in the budget year.

In order to provide upfront guidance to the Judicial Council regarding expenditures from the IMF, we further recommend that the Legislature identify its priorities for use of the IMF in statute, such as by placing statutory limits on how the fund can be used. In developing priorities for the IMF, we recommend the Legislature consider the following questions.

- What Is the Purpose of the IMF? A key question for the Legislature to consider is what the purpose of the IMF is, particularly since there generally are few restrictions on how the funds can be used. Given recent changes in the way trial courts are funded, the Legislature could choose to redefine what projects and programs should be supported by the IMF. For example, the cap on the amount of reserves that courts are allowed to maintain significantly limits the ability of trial courts to plan and fund limited–term projects to help themselves operate more efficiently, support additional workload, or provide greater access to court services. The Legislature could prioritize the use of the IMF for these types of projects.

- Should Projects Support Ongoing Expenditures? Given the steady decline of fine and fee revenue deposited into the IMF, the Legislature may want the judicial branch to focus on one–time (versus ongoing) expenditures. Supporting a greater proportion of one–time expenditures would provide the Judicial Council with a funding cushion that would help them more easily reduce expenditures to match unexpected fluctuations in revenues. Additionally, the Legislature could encourage the judicial branch to focus on one–time projects that specifically help trial courts operate more efficiently. To the extent that such projects replace existing programs or systems, trial courts can use those existing monies to support the ongoing costs of the new programs or systems instead.

Modify Governor’s Proposal. We recommend not approving the proposal to support CCMS V3 from the IMF as this proposal does not help address the immediate insolvency of the IMF. Instead, we recommend that the Legislature wait to decide whether to support CCMS V3 from the IMF until it decides how to better control judicial branch expenditures from the fund. As such, we recommend that the Legislature modify the administration’s proposal by approving a reduction in the annual transfer out of the IMF of $13.7 million—from $20 million to $6.3 million. This reduced transfer would help the judicial branch partially address the immediate insolvency of the IMF.

State law requires the Director of the Department of General Services (DGS) to negotiate and execute leases for space on behalf of nearly all state departments, unless specifically authorized otherwise. The Director of DGS is also required to notify the Legislature at least 30 days before executing a lease on behalf of a state agency if the lease crosses certain thresholds. Specifically, such notification is required if the firm lease period is five years or more and requires an annual rent of more than $10,000. Upon execution of the lease, annual increases in rent are generally treated as workload adjustments in the annual state budget process. As a result, departments are not required to submit a request to the Legislature specifically to receive additional funds for such increases.

In contrast, Judicial Council negotiates and executes its own leases without state input. Additionally, state law includes no requirements for the judicial branch to notify or report to DGS or the Legislature prior to executing leases. Increased funding to address annual rental increases for the judicial branch’s statewide entities—the Supreme Court, the Courts of Appeal, Judicial Council, and the Judicial Council Facility Program—are requested in the annual budget process. Currently, the judicial branch has 26 leases for its statewide entities.

The Governor’s budget proposes a $934,000 General Fund augmentation to cover increases in rent for statewide judicial entities that initially occurred in 2014–15. (The judicial branch absorbed these increased costs in 2014–15.) In addition, the Governor intends to address future rent increases as baseline adjustments in workload instead of as a requested change presented to the Legislature.

Proposed Funding for Rent Increase Appropriate. The Governor’s proposed augmentation would address annual inflationary increases that are standard requirements in most leases. If the additional funding is not provided, the statewide judicial branch entities would be required to absorb these costs as they are in the current year. This would be particularly difficult for the Supreme Court and the Courts of Appeal to do without impacting their workload, as most of their funding is used for staff salaries. According to the judicial branch, the statewide entities held positions vacant, delayed entering into contracts, and delayed purchasing equipment in order to redirect funds to address their rental increases in 2014–15.

Workload Adjustments for Increased Rent Removes Legislative Oversight. On the one hand, the provision of annual rent increases as a workload adjustment to the judicial branch budget merits consideration. Such a change would treat judicial branch statewide entities in a similar manner as other state departments who have their rental increases reflected as workload budget adjustments. However, unlike certain leases for other state departments and agencies, the Legislature currently receives no notification and opportunity to review leases before execution by the judicial branch. Instead, the Legislature only maintains oversight of judicial branch leases through its approval of a budget change proposal in the annual budget process. Providing funding as a workload adjustment would effectively remove legislative oversight of judicial branch lease costs, as the branch is not subject to any of the state’s existing notification or reporting requirements for leases. Because the state is responsible for providing funding for such increased costs, it should maintain oversight of judicial branch leases.

We recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposed $934,000 General Fund augmentation to address increased state judiciary rental costs. However, to ensure continued legislative oversight when the administration treats future rental increases as workload adjustments, we also recommend the Legislature approve statutory language to require the judicial branch to follow the same notification requirements for leases currently required of DGS. This would enable continued legislative oversight of judicial branch leases and subject the branch to the same level of oversight as most state departments.

The state works closely with local public safety agencies in several ways to create a cohesive criminal justice system. First, the state establishes the body of laws that define crimes and specify punishments for such crimes. Local governments are generally responsible for enforcing these state laws. For example, cities and counties fund the police and sheriff departments that arrest individuals for violating state law. In addition, state and local agencies each have certain responsibilities for managing the population of offenders who violate the law and enter the correctional system.

While the state has historically had a significant role in managing the correctional population, the state’s role in policing communities is more limited. The majority of funding for local police activities comes from the local level. Accordingly, most decisions about how to administer police services are also made at the local level. The state’s role in local police activities has generally been to establish standards for the selection and training of peace officers. Specifically, the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) sets minimum selection and training standards for California law enforcement, develops and runs training programs, and reimburses local law enforcement for training. In addition, the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) operates the Standards and Training for Local Corrections Program, which includes developing minimum standards for local correctional officer selection and training, certifying training courses for correctional staff, and reimbursing local correctional agencies for certain costs associated with the training and standards. The state also provides grant funding for various purposes and a limited amount of operational assistance.

Governor’s Budget Raises Questions About the State Role in Funding Local Law Enforcement. The Governor’s budget includes a couple of proposals related to local law enforcement that raise questions about what the state’s role should be in funding these activities. As discussed below, the budget proposes to reduce the number of state staff at POST. At the same time, the budget proposes to increase state payments made directly to local law enforcement agencies, primarily city police. Given the limited amount of funding the state provides to local law enforcement—particularly relative to the total spent on local law enforcement from all fund sources—the Legislature may want to consider whether the state should consider focusing its limited dollars on state–level priorities and responsibilities. For example, the Legislature might determine that the state’s primary role in local law enforcement should be to provide standards and training to ensure that peace officers receive consistent and high–quality training. We discuss the proposals and our recommendations related to them in greater detail below.