About 150,000 violent crimes are reported annually in California. However, a recent study by the U.S. Department of Justice found that, on average, only about three–fifths of violent crimes are reported to law enforcement. This suggests that there could be over 250,000 violent crimes each year in California. Many of these victims require medical care, mental health counseling, legal services, and other assistance as they recover from the crime and participate in the justice system. Some victims access services through private resources, such as their existing health insurance. However, many victims must rely to a certain extent on public programs in order to access services. The state funds services to victims primarily through VCGCB and OES.

As part of the Governor’s budget for 2015–16, the administration proposes to reorganize VCGCB. In this report, we (1) review existing victim programs, (2) identify challenges regarding the current structure and delivery of these programs, and (3) recommend steps to help address these challenges.

As shown in Figure 1, a variety of victim programs are administered by four state departments: VCGCB, OES, the Department of Justice (DOJ), and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). For 2015–16, the Governor’s budget proposes about $225 million for these programs, with most of the funding split between VCGCB and OES. These programs—47 in all—support a wide array of assistance to victims of crime. In most instances, the programs allocate grants to local agencies and community–based organizations to help support some of the services that they provide to victims of crime. For example, some community–based organizations receive state funds to provide crisis intervention services to women escaping domestic violence. We describe the state’s victim programs in greater detail below.

Figure 1

Overview of State Victim Programs

Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board

- California victim compensation program (known as “CalVCP”).

- Trauma recovery center grants.

- Good Samaritan Program.

- Missing Children Reward Program.

|

Governor’s Office of Emergency Services

- Victim Witness Assistance Program.

- 39 other grant programs.

- Victim–related task forces.

|

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Restitution collection and notification.

|

- Victim assistance and information services.

|

The VCGCB is a board within the Government Operations Agency that is comprised of three members—the Secretary of the Government Operations Agency, the State Controller, and a Governor’s appointee. As discussed below, VCGCB’s primary responsibility is administering four of the state’s victim programs: the California victim compensation program (CalVCP), trauma recovery center (TRC) grants, Good Samaritan Program, and the Missing Children Reward Program. The board also administers programs unrelated to victims, including the Government Claims Program, which processes claims for money or damages against the state, and a program that pays claims to wrongfully imprisoned individuals. The Governor’s 2015–16 budget proposes $105 million—primarily from the Restitution Fund (supported by a portion of fines and fees collected from traffic infractions and criminal offenders) and federal funds—and 144 staff for VCGCB’s victim programs. This reflects a decrease of $14 million from the levels provided in 2014–15.

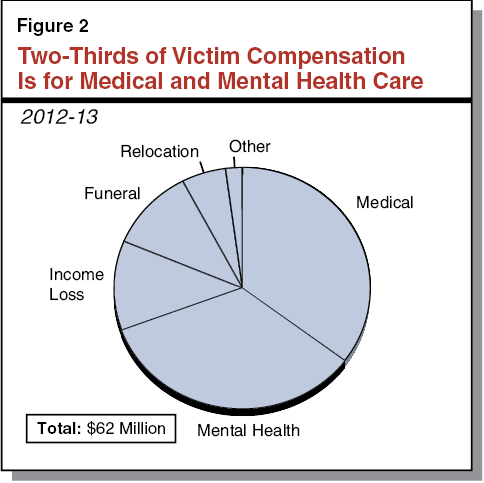

Purpose. The largest of VCGCB’s programs is the CalVCP, which helps pay for expenses that result when a violent crime occurs and are not paid for by another source (such as the victim’s health insurance). Specifically, if a victim of a crime has been injured or has been threatened with injury, he or she could be eligible to have qualifying costs paid for by the board. In 2012–13, the program provided a total of $62 million in payments to victims. As shown in Figure 2, the most common payments made by the program are for medical and mental health care.

Funding. The CalVCP is supported by the Restitution Fund and federal Victim of Crime Act (VOCA) grant funds. Restitution Fund monies are used as a match to draw down federal funds under the VOCA grant program. Specifically, the CalVCP receives 60 cents in federal VOCA grant funding for each state dollar spent to provide qualifying victims with services. The Governor’s budget proposes $103 million and 144 staff for CalVCP in 2015–16. Of this amount, $80 million is from the Restitution Fund and $23 million from federal VOCA grant funds.

Application Process. Individuals can fill out and submit an application to VCGCB themselves or with the assistance of others, such as private attorneys or “victim advocates”—individuals who are specially trained to assist victims and work for locally run victim witness assistance centers. (Please see the nearby box for more detailed information on victim advocates.) Applicants are required to submit additional information after the initial application, such as a copy of the crime report to verify that they qualify for the program. A representative for the victim, such as an advocate, can also help with these subsequent steps. Once an application is approved, victims can be compensated by the program in a couple of different ways. In the majority of cases, victims receive services from providers, who then send qualifying bills directly to CalVCP. The program has established reimbursement rates it pays to providers. For example, CalVCP will pay $99 for a one–hour counseling session with a psychologist. However, the reimbursement rates may not cover all of the costs the provider incurred. This is similar to the way many medical insurance reimbursement rates do not fully cover all provider costs. Alternatively, victims could pay their bills themselves and then request reimbursement from CalVCP.

Victim advocates are individuals who work for victim witness assistance centers (which provide services to victims and witnesses of crime) and receive special training and certification to work with victims of crime. Advocates have an important role in the state’s victim services programs because they both provide some services directly to victims and help victims connect with services.

Advocate Training and Certification. In order to effectively assist victims, advocates receive special training on the needs of crime victims, the programs available to them, and effective ways of interacting with victims who are traumatized or in a state of crisis. Specifically, all advocates must be certified by the California District Attorneys Association. This certification requires the completion of a 40–hour training program. The certification program trains advocates on a broad array of victim issues, such as victim rights, how victims respond to crime, and the needs of specific types of victims (such as domestic violence and child abuse victims). In addition, some advocates employed by victim witness assistance centers also have a background in social work or mental health counseling, which furthers their ability to effectively assist victims.

Assistance Provided by Advocates. Because these advocates work for victim witness assistance centers, which are generally based in law enforcement agencies, they directly provide certain services to guide the victim through the justice system. For example, advocates may accompany victims to court to help them with the stress of possibly encountering their perpetrators or individuals connected to their perpetrators. Advocates also provide information on the status of pending legal cases and help victims understand the legal process.

Advocates also help victims access services provided by other programs, such as California’s victim compensation program (CalVCP). Specifically, advocates working in the state’s 59 victim witness assistance centers (one in each county and an additional one in the City of Los Angeles) can represent victims in the CalVCP application and approval process. This means that the advocate can fill out the application form, obtain necessary supporting documents, submit the application, and communicate with CalVCP staff regarding questions about the application. Because advocates generally work for a law enforcement agency, they have the ability to access the documents necessary to substantiate a victim’s application (such as crime reports). They also have access to other law enforcement agencies, such as the police department that responded to the crime. Such access allows advocates to speak to the officer who wrote the crime report and get supplemental information if it is needed for the CalVCP application. In addition to assisting with CalVCP applications, advocates refer victims to other services that they may qualify for, such as emergency shelters or other community–based programs.

The process of getting an application and associated bill payments approved by CalVCP involves multiple steps, largely due to federal VOCA requirements. Specifically, VOCA requires that VCGCB ensure that applicants (1) were the victim of a qualifying crime (typically by providing a crime report), (2) were not involved in a criminal act at the time of the crime, and (3) cooperated with law enforcement in the investigation of the crime. As a result, VCGCB claim processors who work in Sacramento must sometimes go through numerous steps to get all of the information necessary from the victim in order to satisfy the federal requirements. Because VCGCB claim processors typically communicate with victims through phone calls and written correspondence, the process can be lengthy.

In an effort to streamline the process for victims, VCGCB has established “joint powers” (JP) agreements with some counties to fund staff in victim witness assistance centers to evaluate and approve CalVCP applications and payments—rather than evaluating and approving applications with VCGCB staff in Sacramento. These claim processors are located in victim witness assistance centers along with victim advocates who assist victims in completing the CalVCP application. Since the advocates have more experience with the claim process and greater access to local law enforcement to get the necessary crime information, the process is shorter and easier for the victim than if the victim’s application is processed by VCGCB staff. Currently, VCGCB has JP agreements with 20 counties to fund between 150 and 175 positions. These counties serve victims within their jurisdiction, as well as in neighboring counties. In total, 51 counties are served through the 20 JP agreements. The VCGCB reports that in recent years between 75 percent and 80 percent of applications were processed by counties with staff funded through JP agreements.

Purpose. The VCGCB also administers a grant program that funds several TRCs. TRCs are centers that directly assist victims in coping with a traumatic event (such as by providing mental health care and substance use treatment). For example, victims may receive weekly counseling sessions with a licensed mental health professional at a TRC for a specified amount of time. The centers also sometimes help victims connect with other services provided in their community and by the state.

Funding. While some of the TRCs existed before receiving grants from VCGCB, the board first began funding TRCs in 2001 with a grant to the San Francisco TRC. Since then, three other TRCs have also received state funding—one in Long Beach and two in Los Angeles. Currently, VCGCB provides a total of $2 million annually in grants to four TRCs.

- San Francisco TRC. The San Francisco TRC is affiliated with San Francisco General Hospital—a level I trauma center—and the University of California, San Francisco. (A level I trauma center is a 24–hour research and teaching hospital with the surgical and medical capabilities to handle the most severely injured patients.)

- Long Beach TRC. The Long Beach TRC is affiliated with Dignity Health St. Mary Medical Center—a level II trauma center—and California State University, Long Beach. (A level II trauma center is 24–hour hospital with the surgical and medical capabilities to handle severely injured patients.)

- Los Angeles TRC—Special Service for Groups. The first Los Angeles TRC to receive state funding is affiliated with a community–based organization, Special Service for Groups, which provides a wide array of services, such as substance use treatment, mental health counseling, and housing assistance.

- Los Angeles TRC—Downtown Women’s Center. The second Los Angeles TRC to receive state funding is affiliated with a community–based organization, the Downtown Women’s Center, which provides housing assistance and other supportive services in an effort to end homelessness for women.

Beginning in 2016–17, funding for TRCs will increase significantly as a result of Proposition 47, passed by voters in November 2014. Proposition 47 reduces the penalties for certain crimes, which will result in state savings, mainly by reducing the number of inmates in state prisons. Under the measure, these savings will be deposited into a special fund with 10 percent of the funds provided to VCGCB for TRCs. We estimate that Proposition 47 funding for TRCs will likely total between $10 million and $20 million annually beginning in 2016–17. This would reflect an increase in funding for TRCs of roughly five to ten times the current level. (Please see our report The 2015–16 Budget: Implementation of Proposition 47 for more detailed information regarding Proposition 47.)

The Good Samaritan Program provides compensation to individuals who suffer injury or loss as a result of their efforts to prevent a crime, apprehend a criminal, or rescue a person in immediate danger of injury or death. The individual acting as a “good Samaritan” (or next of kin) may apply for up to $10,000 in compensation. In order to be eligible, the individual must not be a public safety worker who was on duty at the time of the event and must not have received compensation from another source, such as CalVCP. The Governor’s budget proposes $20,000 for the Good Samaritan Program in 2015–16.

The Missing Children Reward Program was established in 1986, along with a special fund—the Missing Children Reward Fund—to encourage individuals to provide information that leads to the return of missing children and incentivize nonstate entities (such as private individuals) to offer rewards for missing children. The program authorizes VCGCB, in coordination with DOJ, to pay a $500 reward to individuals who (1) provide information leading to the return of a missing child, (2) receive a similar reward from a nonstate entity, and (3) meet other eligibility criteria, such as not being related to the missing child. An initial deposit of $24,000 was made to the account from the Victim Witness Assistance Fund (discussed below). The Governor’s budget proposes to fund the program from the Restitution Fund beginning in 2015–16 rather than the Missing Children Reward Fund, which no longer has the necessary resources to support the program.

The OES is primarily responsible for assuring the state’s readiness to respond to and recover from natural and man–made emergencies. In addition, OES administers certain grant programs, including most of the state’s victim grant programs.

The OES received responsibility for these programs in 2004–05, which were previously under the jurisdiction of the Office of Criminal Justice Planning (OCJP). When OCJP was eliminated, most of its programs (including the various victim programs below) were transferred to OES even though OES did not have expertise in these program areas.

The proposed budget provides a total of $119 million to OES for various victim–related programs for 2015–16—$77 million in federal funds and $42 million in state funds. Most of these funds support various grant programs.

Federal Requirements. There are federal requirements that govern the use of much of the federal funding OES administers for victim grant programs. However, these requirements are typically broad and give the state a significant degree of flexibility to determine the number and type of victim programs the state administers. For example, some federal funding sources specify minimum amounts that must be spent on specific types of programs, such as requiring that a minimum of 30 percent of federal Violence Against Women Act funds be spent on direct services to victims, but do not require that the state fund specific programs or a certain number of programs.

State Requirements. State law establishes additional requirements for the use of state funds provided for victim grant programs. For example, some of the state’s existing programs are specified in state law. However, OES has significant flexibility to determine how to allocate funding to the various victim programs it administers. This is because funding for these programs is generally appropriated in the annual budget to OES broadly without specifying amounts to each program. Along with the discretion to determine funding levels for programs, OES has authority to establish new programs. It makes decisions on which programs to establish and fund based on the recommendations of its advisory task forces, which are discussed below.

The OES administers the Victim Witness Assistance Program, which provides grants to each of the state’s 58 counties and the City of Los Angeles to fund victim witness assistance centers. These centers provide multiple services to roughly 150,000 victims each year, but primarily focus on assisting victims through the justice system and with accessing other victim programs through the help of a victim advocate. For example, advocates at the centers accompany victims to court and assist them in applying for compensation from CalVCP. Statewide, 51 victim witness assistance centers are based in district attorney’s offices, 3 are in county probation departments, 3 are in community–based organizations, 1 is in a county sheriff’s department, and 1 is in the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office. The Governor’s budget proposes $22 million for the Victim Witness Assistance Program to support these centers in 2015–16. This amount includes (1) $11 million from the Victim Witness Assistance Fund, which is primarily supported by a portion of fines and fees collected from traffic infractions and other criminal offenses, and (2) $11 million in federal funds. In many cases, these funds will only partially support the costs of victim witness assistance centers. As a result, some centers also rely on local funding.

The OES also administers 39 other grant programs that fund various activities related to assisting victims. These programs generally fund victim services provided through community–based organizations or local agencies that provide services to victims, such as mental health counseling. For example, OES provides grant funds to rape crisis centers to provide services such as counseling, self–defense training, and staff who accompany victims to hospitals or other appointments. Some programs also provide training and other assistance to law enforcement, first–responders, and community–based providers in developing effective approaches to assisting victims. The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 proposes a total of $89 million for these victim grant programs. This funding is from a variety of sources, with the majority coming from federal funds, the state General Fund, and the Victim Witness Assistance Fund.

The OES also administers five victim–related task forces that bring together expertise on specific types of victims in order to collect and disseminate information on victim needs and best practices. They also provide recommendations to OES on how to allocate the funding associated with its various victim programs. In addition, the task forces can recommend the creation of new grant programs or changes to existing programs. The five task forces are the following:

- Domestic Violence Advisory Council.

- State Advisory Committee on Sexual Assault.

- Children’s Justice Act Task Force.

- Child Abduction Task Force.

- Violence Against Women Act Implementation Committee.

CDCR Programs. While the majority of CDCR’s workload relates to supervising offenders in state prison and on parole, the department also offers certain services to victims. For example, CDCR collects the criminal fines and fees owed by inmates in its facilities. This includes restitution orders (payments owed directly to victims) and restitution fines (paid into the Restitution Fund). Typically, when CDCR collects the fines and fees owed by offenders, it transfers them out of inmate accounts that are maintained for inmates to deposit and withdraw money, similar to bank accounts. In cases where it is collecting restitution orders for victims, the department transfers the funds from an inmate’s account to VCGCB, which then provides it to the victim. In addition, when requested, CDCR will notify victims of certain changes in an inmate’s status, such as when the inmate is eligible for parole or if the inmate escapes from prison. The CDCR also administers a program that provides a limited amount of funding to assist victims with the cost of travel when they choose to attend a parole hearing. The Governor’s budget proposes $2.8 million ($1.4 million in special funds, $1.1 million from the General Fund, and $200,000 in federal funds) to support CDCR’s victim services programs in 2015–16.

DOJ Programs. The department provides victim assistance, particularly in cases that are directly prosecuted by DOJ or cases where DOJ is seeking to uphold a conviction on appeal. These services are similar to those provided by victim witness assistance centers and primarily involve assisting the victim though the justice system. In addition, DOJ provides notification services to victims on the status of all cases that are appealed. Given DOJ’s expertise with respect to the state’s legal system, the department also provides various other services to victims, such as providing information about the legal process. The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 includes $800,000 ($600,000 from the General Fund and $200,000 in federal funds provided through a grant from OES) for DOJ’s victim services unit.

Based on our review of the state’s victim programs, we find that the state lacks a comprehensive strategy for assisting crime victims. A primary reason for this is because the state lacks a lead agency that is responsible for planning and coordinating that state’s efforts to assist victims. Instead, the state’s various victim programs are all administered by departments whose primary mission is not focused solely on victims. For example, VCGCB is currently focused on both victim programs and government claims, and OES has a primary mission of planning and coordinating the state’s response to emergencies, which is unrelated to victim services. The absence of a comprehensive strategy limits the efficiency and effectiveness of the state’s victim programs.

Specifically, we find that (1) programs lack coordination, (2) the state is likely missing opportunities for federal VOCA grants, (3) many programs are small and appear duplicative, (4) narrowly targeted grant programs undermine prioritization, and (5) limiting advocates to victim witness assistance centers limits access to CalVCP. Figure 3 summarizes our findings, which we describe in detail below.

Figure 3

Summary of LAO Findings

- Programs Lack Coordination

|

- Likely Missing Opportunities for Federal Funds

|

- Numerous Small, Duplicative Programs Reduces Efficiency and Effectiveness

|

- Narrowly Targeted Grants Undermine Prioritization

|

- Limiting Advocates to Victim Witness Assistance Centers Hinders Access to CalVCP

|

Our review finds that the state’s victim programs lack coordination. This is problematic because many programs are closely interrelated. For example, a victim may receive legal assistance through a victim witness assistance center (funded by grants from OES), receive assistance from that center to apply to CalVCP, and directly receive services from community–based providers that receive grants from either VCGCB or OES. Despite this, the state’s victim programs currently lack the level of coordination one would expect from such closely related programs.

Lack of Collaboration. Staff at both VCGCB and OES indicated that the two departments generally do not collaborate on the administration of the state’s largest victim programs. Rather, the departments administer their programs independently, each with separate goals, processes, and subject matter expertise. Such a lack of collaboration limits the effectiveness and efficiency of programs. For example, OES administers several task forces that provide subject matter expertise to its staff and grant recipients, but this knowledge is not shared with the staff at VCGCB.

Poor Program Administration. Another example of a lack of coordination is the Missing Children Reward Program. As mentioned above, the Governor’s budget proposes to support the Missing Children Reward Program from the Restitution Fund because the Missing Children Reward Fund no longer has sufficient resources. However, since the inception of the program 28 years ago, no rewards have been paid. Instead, funding in the account was spent only on state administrative fees, which are typically charged to special funds. The statutory authorization for the program contemplates an administrative role for both VCGCB and DOJ. However, when each department was asked why no rewards were paid, each indicated that the other was primarily responsible for the program. Overly restrictive reward criteria or other factors likely contributed to the failure of the program to pay out rewards. However, the unclear delineation of administrative duties hampered the program because neither department was monitoring it closely enough to realize that it was not being accessed until the funding in the account was depleted. It is possible that a similar lack of coordination is undermining the ability of other victim programs to fully achieve their goals.

We also find that the state is likely not maximizing the amount of federal VOCA matching funds that could be drawn down. As discussed above, the state receives 60 cents in federal VOCA funds for each state dollar spent to provide qualifying victims with services. Currently, VCGCB determines the amount of state expenditures that are used as a match to draw down federal funds based on the amount of qualifying CalVCP expenditures from the Restitution Fund. However, it appears that some state expenditures in other victim programs meet the eligibility criteria for matching funds under VOCA. For example, the Domestic Violence Assistance program at OES spent $37 million (including $20.6 million from the General Fund) and provided over 41,000 mental health counseling sessions to victims in 2013–14. Because these sessions are a qualifying service under VOCA, it seems likely that if OES had coordinated these expenditures with VCGCB, some additional VOCA funds could have been received.

The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 proposes to spend $41 million in state funds for other victim grant programs, many of which provide at least some services that appear to meet the criteria for the federal match. Of this total, $39 million is for grant programs administered by OES and $2 million is for TRC grants administered by VCGCB. While VCGCB staff have indicated that they are working with the TRCs on reporting requirements to determine how much of the TRC grant funds are eligible for VOCA matching funds, no such effort is being made related to the programs administered by OES. As a result, the state may be missing out on millions of dollars in additional federal funding for victim programs.

In addition, we find that the state has many victim grant programs that appear duplicative and provide relatively small grant awards. Such an approach does not result in the most efficient and effective use of funds. As shown in Figure 4, many of the state’s 47 victim programs overlap in terms of the type of crime victim served. For example, 31 of the state’s 47 programs serve victims of sexual assault. We also note that 22 programs each awarded less than $500,000 in 2013–14, with the average grant awarded to an applicant being about $180,000.

Figure 4

Many State Victim Programs Serve Similar Types of Victims

|

Department/Program

|

Type of Victim Served

|

|

Child Abuse

|

Sexual Assault

|

Domestic Violence

|

Other

|

|

Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

Victim Compensation

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Trauma Recovery Center grants

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Good Samaritan

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Missing Children Reward

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Governor’s Office of Emergency Services

|

|

|

|

|

|

Victim Witness Assistance

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

American Indian Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Anti–Human Trafficking Task Force

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

California Victim Witness Advocate Training

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Court Education and Training

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Unserved/Underserved Victim Advocacy and Outreach

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Victims’ Legal Resource Center

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Children’s Justice Act Evaluator

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

|

Children Exposed to Domestic Violence Specialized Response

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

|

Domestic Violence Assistance

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

|

Domestic Violence Response Team

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Equality in Prevention and Services for Domestic Abuse

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Family Violence Prevention

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Law Enforcement Training

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

State Coalition Technical Assistance and Training

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Statewide Domestic Violence Prevention Resources Center

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Farmworker Women’s Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Forensic Medical Forms

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

Legal Training

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Medical Training Center

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Prison Rape Elimination Act

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

Rape Crisis

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

Sexual Assault Training and Technical Assistance

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

American Indian Child Abuse Treatment

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Child Abduction Intervention and Resources Training

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Child Abuse Treatment

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Child Sexual Abuse Training and Technical Assistance

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

|

Child Sexual Abuse Treatment

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

|

Homeless Youth and Exploitation

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

Human Trafficking of Minors Law Enforcement and First Responder Training

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

Native American Children Training Forum

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Statewide Multi–Disciplinary Interview Center Coordinator

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Training on Prosecution of Physical and Sexual Abuse of Children

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

|

Violence Against Women Vertical Prosecution

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Youth Emergency Telephone Referral Network

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

Victim Identification and Notification Everyday

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Victim Notification

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Victim Services Information

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Campus Sexual Assault

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

Child Victims of Human Trafficking

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

Victim–Related Task Forces

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Other Departments

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDCR Restitution Collection and Notification

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

DOJ Victim Assistance and Information Services

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

There are different reasons why having many duplicative and small programs can be inefficient. First, since state staff and other administrative resources are required for each program, less funding ends up being available to directly serve victims. In addition, it forces entities to apply for funding from multiple programs, which requires them to navigate through and keep track of the different rules and eligibility requirements of each program. For example, a grant recipient may have to apply for multiple small awards just to fund one staff position to assist victims. Our review found that grant applicants are frequently awarded grants from multiple state programs. Specifically, in 2013–14, 38 percent of grant recipients received funding from multiple grant programs administered by the state. Moreover, to the extent that a particular staff person is funded from multiple state grants, the individual may need to spend unnecessary time preparing reports to comply with the terms of each grant received rather than actually providing services to victims.

We also find that having many small, narrowly targeted programs may not effectively prioritize the state’s limited funding to assist victims. This is because such a structure can limit the flexibility to target resources to the areas of greatest need, which can change over time. By restricting each grant program to a relatively small subset of potential applicants, applicants who are providing services that could be deemed of a higher priority would not be considered for funding. For example, several programs provided grants in 2013–14 to produce brochures and update staff manuals for law enforcement to provide information about addressing victim needs. While such information is important, it is unclear whether these types of efforts are a higher priority than actually providing services, such as medical and mental health care to victims.

As described above, advocates help victims navigate the CalVCP application process. However, because CalVCP only recognizes advocates from victim witness assistance centers, some victims are not benefitting from the assistance of advocates and may face challenges in accessing CalVCP.

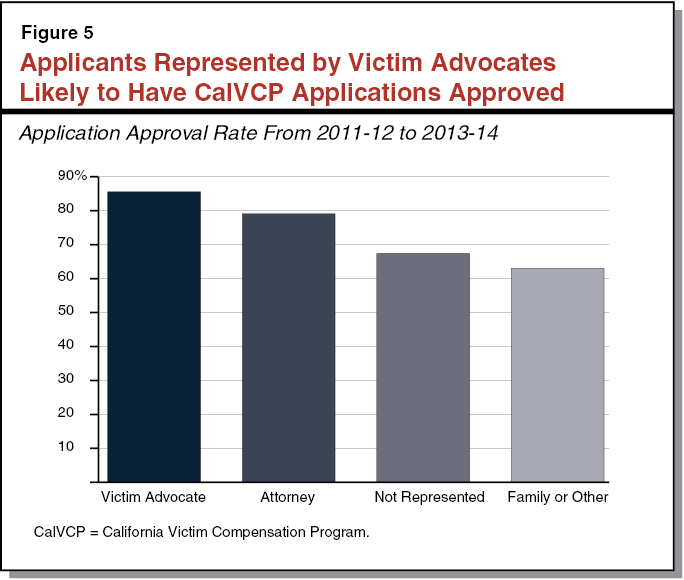

Different Individuals Assist Victims in CalVCP Application Process. Victims who apply to CalVCP can have someone else represent and assist them throughout the application process, such as with completing the application, providing subsequent documents, and communicating with VCGCB staff on the victim’s behalf. Specifically, CalVCP allows victim advocates from a victim witness assistance center, family members, and attorneys to represent a victim. According to CalVCP, about three–fourths of victims applying to CalVCP are represented by a victim advocate, 2 percent by an attorney, and less than 1 percent by a family member. The remaining applicants represent themselves.

Greater Approval Rate With Assistance From Advocates. According to data from CalVCP, victims who are represented by a victim advocate are more likely to have their application approved. From 2011–12 through 2013–14, VCGCB annually received an average of about 53,000 applications for victim compensation. Of this total, 82 percent of applications were approved and 18 percent were denied. However, the approval rate differs depending on the type of representative that assisted the victim in the application process. As shown in Figure 5, 86 percent of applications handled by victim advocates were approved. Those who were represented by attorneys had the second highest approval rate at 79 percent. Victims who represented themselves or were represented by a family member (such as parents of minor children who were victimized) were less likely to have their application approved. The data suggests that the application process is complex enough that some victims need an advocate to successfully access CalVCP. In addition, advocates can advise victims on the eligibility criteria of the program, which may limit the number of ineligible victims who apply for the program and are subsequently denied.

Some Victims Need Advocates to Help Provide Evidence That a Crime Occurred. Data provided to us by VCGCB staff shows that from 2011–12 through 2013–14 the largest single reason for application denial was a lack of evidence that a crime occurred. One possible reason why victims represented by advocates have a high approval rate is because advocates help victims to substantiate their claims such as with crime reports. Such assistance is often necessary because crime reports may be difficult for the victim to obtain and are not written with the intent of substantiating a claim to CalVCP. Instead, they are written for the purposes of documenting the crime the offender is charged with and any information necessary for law enforcement to complete an investigation. As a result, a crime report can sometimes leave out the information relevant to victims and their claims, making it difficult for VCGCB to evaluate the validity of the claims. For example, the perpetrator may ultimately be arrested and charged with a crime that would not appear to have a victim (such as evading police), even if the victim was injured by the person while they were evading police. Victim advocates can often address these types of issues on behalf of the victim by working to get the crime report amended. Victims who do not work with an advocate likely have much more difficulty in addressing these types of issues on their own.

CalVCP Only Recognizes Advocates in Victim Witness Assistance Centers. Currently, only certified victim advocates working with victim witness assistance centers are allowed to represent victims in their application to CalVCP. However, some victims are uncomfortable working with victim witness assistance centers because these centers are almost exclusively operated by law enforcement agencies. A recent study by the Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy conducted focus group discussions and individual interviews with crime victims and found that some of the victims have a lack of trust in services provided by law enforcement agencies. According to the study, this is due to prior negative encounters with law enforcement. As a result, victims that are uncomfortable receiving assistance from a law enforcement–based advocate likely have greater difficulty in accessing services through CalVCP.

The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 proposes to reorganize the programs currently administered by VCGCB. Specifically, the Governor proposes to shift the Government Claims Program to the Department of General Services (DGS) while keeping the administration of VCGCB’s remaining programs with the board. According to the administration, the Government Claims Program is better aligned with the mission of DGS to provide services to departments statewide. This change would also result in VCGCB having primarily victim programs to administer. In order to allow time for a thoughtful approach, the Governor proposes to make these changes beginning in 2016–17. In the intervening time, the Governor plans to engage stakeholders to better develop the details of the reorganization proposal.

In view of the challenges we identified with the current structure of the state’s victim services programs, we think that the Governor’s proposal to reorganize VCGCB merits legislative consideration because it enables VCGCB to focus primarily on victim programs. However, we think that additional changes are needed to improve the state’s victim programs. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature (1) modify the Governor’s proposals to restructure VCGCB, (2) shift most victim programs to the reorganized VCGCB, (3) require the board to develop a comprehensive strategy for victim programs, and (4) utilize Proposition 47 funds to improve access to services through TRCs. We summarize our recommendations in Figure 6 and describe them in greater detail below.

Figure 6

LAO Recommendations for Improving Victim Services

- Restructure VCGCB to Better Focus on Victim Programs

- Shift nonvictim programs to DGS.

- Change board membership.

|

- Shift Most Victim Programs to the Restructured VCGCB

|

- Require Restructured Board to Develop Comprehensive Strategy

|

- Utilize Proposition 47 Funds for TRCs to Improve Access to Programs

- Ensure TRCs are effective.

- Expand victim advocates to TRCs.

- Expand TRCs to additional regions of the state.

- Refer CalVCP applicants to TRCs.

|

Under the Governor’s proposed reorganization, shifting the Government Claims Program to DGS would leave primarily victim programs at VCGCB, creating a department that is focused on victim issues. The Governor’s proposal is a step in the right direction. However, we find that making additional statutory changes to the structure of VCGCB would further improve the state’s administration of victim programs. In addition, we recommend making these changes (including the Governor’s proposal) as part of the 2015–16 budget package because we think this is a necessary first step to improving victim programs.

Shift Nonvictim Programs to DGS. We recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to reorganize VCGCB and move the Government Claims Program to DGS as this will allow the reorganized VCGCB to focus on victim services. In addition, we recommend shifting responsibility for processing claims from wrongfully imprisoned individuals to DGS. This is because these are claims against the state, similar to those processed by the Government Claims Program. These changes would leave VCGCB solely focused on victim programs.

Change Board Membership. In order to ensure that VCGCB is well positioned to focus on and administer only victim programs, we believe additional changes are needed. As mentioned earlier, two of the three members of the VCGCB board have expertise that is primarily applicable to the Government Claims Program and not related to victim services—the Government Operations Agency Secretary and the State Controller. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature change the membership of the board. First, we recommend removing the Secretary of the Government Operations Agency and the State Controller from the board. Second, we recommend that additional members be added to the board to provide expertise in victim issues. For example, the Legislature could consider requiring the board to include an expert in providing trauma–informed services or a victim of crime, as well as representatives from the other state departments that administer victim programs (such as the Attorney General or the Secretary of CDCR). We also recommend that the Legislature appoint some of the board members in addition to having the Governor’s appointees on the board. Finally, we recommend that the appointed members serve fixed terms to increase their independence. These changes would ensure that the new board is more consistent with its reorganized focus on victim issues and would transition the board from largely focusing on claims processing to its new role of program administration.

In view of our recommended changes to the board, we find that VCGCB would be well suited to administer all of the state’s major victim programs. As such, we recommend that the Legislature adopt various statutory changes to shift all of the victim programs in OES to VCGCB as these programs were never consistent with OES’s primary mission. Along with program responsibilities, we also recommend that the program staff with their subject matter expertise be shifted to VCGCB. This consolidation of programs would allow for better coordination among the state’s largest victim programs. For example, it would likely increase the state’s ability to maximize the receipt of federal VOCA funds, given that some of the grant programs currently administered by OES could potentially be used as a state match. In order to facilitate this, we also recommend that the Legislature specifically direct the new board to review all of the state’s victim programs to ensure that the state receives all eligible federal VOCA funds.

We find that the victim services provided by CDCR and DOJ are relatively minor and seem to fit well in their existing departments (versus shifting them to VCGCB). However, to help ensure that the new board coordinates with these departments, we recommend that the Legislature direct the new board to periodically meet with CDCR and DOJ on how they can coordinate their activities to better serve victims. We also note that this coordination would be facilitated if the Legislature decided to have the Attorney General and Secretary of CDCR serve on the board, as discussed previously.

As discussed earlier in this report, part of the challenge with the state’s efforts to assist victims is that it currently lacks a comprehensive strategy. Our recommended changes above would place the reorganized VCGCB in a position to effectively develop such a strategy. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature require the new board to develop a comprehensive strategy for the state’s victim programs. We note that the Governor’s plan to engage stakeholders as part of his proposed reorganization of VCGCB would help inform the development of a comprehensive strategy. Specifically, we recommend requiring the board to provide a comprehensive strategy to the Legislature by January 10, 2017. We find that some of the issues that the strategy should address are:

- Number, Scope, and Priority of Programs. A key aspect of developing a more comprehensive approach to providing victim services is strategically reorganizing the state’s victim grant programs to maximize their effectiveness and efficiency. For example, the new strategy should evaluate whether many of the state’s grant programs should be consolidated to allow for larger grants and lower administrative costs. Such an evaluation would also provide the information necessary to better prioritize the allocation of the limited funding for victim programs.

- Receipt of Federal Matching Funds. In developing a comprehensive strategy, the board should also consider ways that could help ensure that the state draws down all eligible VOCA funds.

- State’s Role in CalVCP. The board should also consider the state’s role in CalVCP. Currently, close to 80 percent of CalVCP applications are processed by counties through JP agreements, which serve 51 of the 58 counties. This is likely because it is often easier for victims to submit applications through JPs due to the JP’s close collaboration with victim advocates. Accordingly, as part of developing a comprehensive strategy, the board should assess whether it makes sense to expand JP agreements to serve the remaining seven counties and what the implications of such an expansion would have on the level of state staff who currently support CalVCP.

- Periodic Program Evaluations. In order to determine which victim programs are effective and should be expanded or continued in the future, it will be important for the board to establish a process for collecting data and periodically evaluating the outcomes of each of the state’s victim programs. The comprehensive strategy should include a plan to facilitate such evaluations.

The additional funding that will be made available for TRCs from Proposition 47 beginning in 2016–17 provides the state with the opportunity to improve victim services. If appropriately structured, we find that TRCs can provide a wide array of services to victims at a single location and can complement existing victim programs. Below, we recommend the Legislature take several steps to expand access to victim services through TRCs.

Ensure TRCs Are Effective. As we discussed in our recent report The 2015–16 Budget: Implementation of Proposition 47, we recommend that the Legislature (1) structure the grants to ensure the funds are spent in an effective and efficient manner, (2) ensure that the services TRCs provide are being included in the state’s application for federal reimbursement funds, and (3) require the evaluation of TRC grant recipients and their outcomes.

Expand Victim Advocates to TRCs. As we discussed above, the use of victim advocates has several benefits but are currently limited to victim witness assistance centers. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature adopt statutory changes to allow TRCs to have formally recognized victim advocates. This would allow TRCs to have trained staff that can represent victims in their application to CalVCP, which would likely increase the approval rate for CalVCP applicants and increase the number of victims applying to CalVCP. It could also streamline workload for CalVCP because advocates can explain the program and eligibility criteria to victims, which may screen out some victims who do not meet the criteria. Proposition 47 funds could be used to support the advocates at the TRCs.

Expand TRCs to Additional Regions of the State. Currently, three of the state’s four TRCs are located in the Los Angeles region. The fourth is located in San Francisco. While there are many victims in these population centers, there are also many victims who do not currently have access to a TRC because they live in another region of the state. Given the potentially significant benefits of TRCs, we recommend that the Legislature provide access to such centers to additional regions of the state by requiring VCGCB to prioritize Proposition 47 grant funding for regions without TRCs.

Refer CalVCP Applicants to TRCs. The Legislature may want to consider requiring VCGCB to notify applicants to CalVCP if there is a TRC in their community and the victim is not already receiving services through another provider. Since the majority of the claims in the victim compensation program are for medical and mental health care, which may be provided by a TRC, some victims could potentially receive more immediate care, without up–front costs, through a TRC.

The state’s existing victim programs are numerous and complex, which creates challenges for both victims and service providers. The Governor’s proposed reorganization of VCGCB along with the forthcoming increase in funding for TRCs from Proposition 47 provides an opportunity for the Legislature to make improvements to the state’s victim programs. The recommendations we make would create a lead agency to focus on victim programs, require the development of a comprehensive strategy for the state’s victim programs, and ensure that Proposition 47 funding for TRCs helps to create a more cohesive system of programs that better serves victims.