Governor’s Budget Includes Significant Increase in Core Funding for Higher Education. The Governor’s budget includes a total of $21.6 billion in core funding for higher education, $1.2 billion (6 percent) more than the 2014–15 level. As the Governor assumes tuition rates will be flat in 2015–16, the bulk of the increase is covered by the state. State funding rises from $13 billion to $14.1 billion—an increase of $1.1 billion (9 percent). Under the Governor’s budget, the California Community Colleges (CCC) receive a relatively large increase in core funding (9 percent), though about two–thirds is attributable to a large augmentation for new adult education consortia. The University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) receive smaller increases (2 percent and 3 percent, respectively).

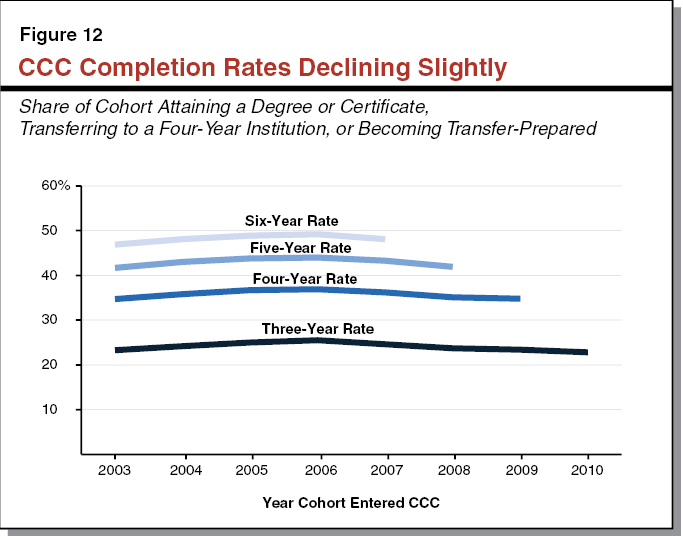

State Beginning to Review Segments’ Performance as Part of Budget Deliberations. New performance reports show that the segments’ performance is improving in some areas, but additional improvement is needed. For example, UC’s and CSU’s graduation rates have increased somewhat in recent years, but, at CSU, barely over half of entering full–time freshmen complete a degree within six years, with most of the other half never completing their degrees. At CCC, completion rates are declining, with only 35 percent of the cohort entering in 2009–10 completing a degree, certificate, or transferring within the next four years. Excess–unit taking also remains an issue, particularly at CSU and CCC, with the average CSU graduate taking 7 courses more than required to obtain a bachelor’s degree and the average CCC student generating more than double the required units. To make the new performance reports more useful moving forward, we recommend the Legislature direct each segment to compare its performance to public institutions serving similar students in other states and identify strategies for addressing areas in need of improvement.

Most Indicators Point to Less Enrollment Demand in the Coming Years. State projections indicate a steady decline in the traditional college–age population over the next five years, with the number of individuals 18 to 24 years of age 300,000 smaller in 2020 compared to 2015. Additionally, the most recent data available on college participation rates shows a small decline. Moreover, both UC and CSU are likely admitting freshman applicants beyond their Master Plan eligibility pools. Furthermore, student demand for community college education tends to dampen during economic recoveries when individuals have more employment opportunities.

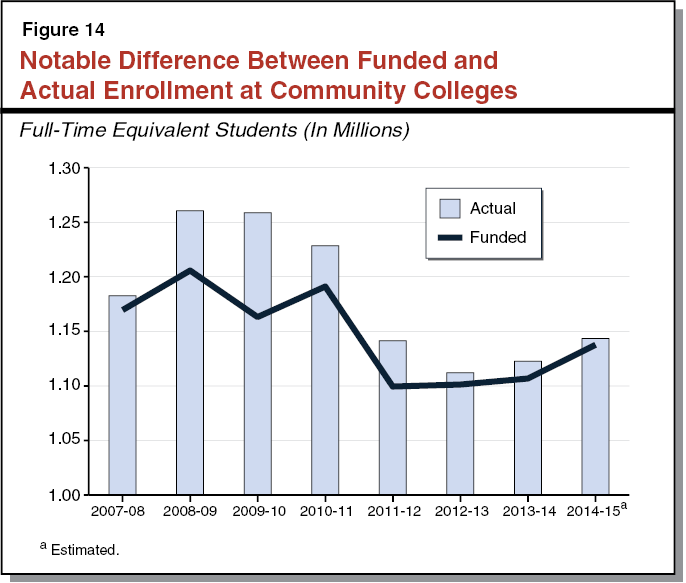

Recommend Setting Enrollment Targets. We recommend the Legislature set enrollment targets for the segments to ensure that they provide the level of access the state desires. We recommend setting UC’s resident enrollment target at its current–year level, with a potential cap on nonresident enrollment. Though CSU appears to lack justification for additional freshman slots, CSU reports denying admission to eligible transfer students. It has not determined, however, how many local transfer students were denied at campuses enrolling nonlocal students. We recommend CSU report certain data by May 1, 2015 that would allow the Legislature to determine if some campuses require growth funding to enroll eligible transfer applicants at their local campus. At CCC, preliminary evidence suggests that enrollment grew by 2 percent in 2014–15, below the budgeted level of 2.75 percent. We recommend waiting until May for an updated estimate of 2014–15 enrollment and then adjusting community college apportionments in the current and budget years accordingly.

Recommend Linking Base Increases With Inflation. For UC and CSU, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed unallocated base increases and instead provide base increases linked to expected inflation. We estimate that providing a 2.2 percent cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) to their core funding (state General Fund and tuition revenue combined) would equate to $126 million for UC and $94 million for CSU. For community colleges, we recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s proposed $92 million COLA but designate another $295 million in unallocated funds for its highest Proposition 98 priorities.

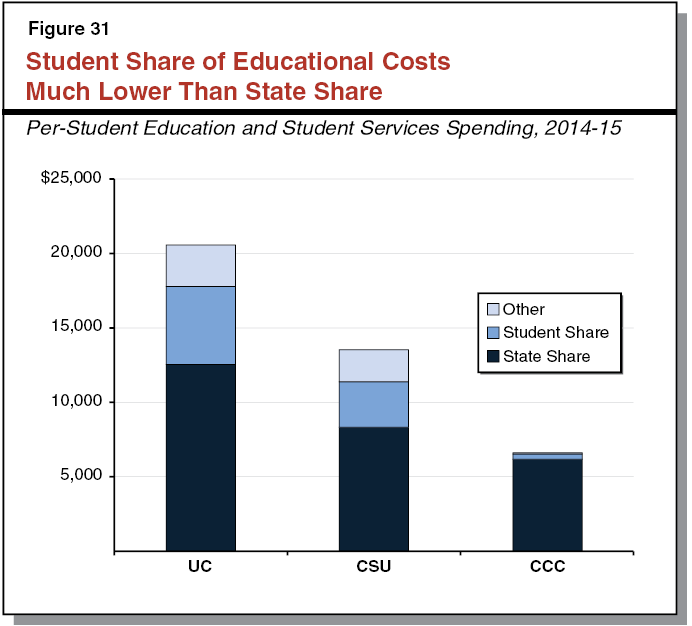

Recommend Adopting Share–of–Cost Policy to Guide Tuition Decisions. After settling on cost increases, the Legislature needs to decide who should bear what share of those increases. We continue to recommend the state adopt a share–of–cost policy under which cost increases are shared by the state and nonneedy students (as financially needy students would receive aid sufficient to cover their cost increases). Such a policy promotes greater attention and accountability for ensuring that any cost increases are warranted. If nonneedy students’ tuition payments were to cover a proportional share of the cost increases, the state share of cost would be $66 million for UC and $47 million for CSU.

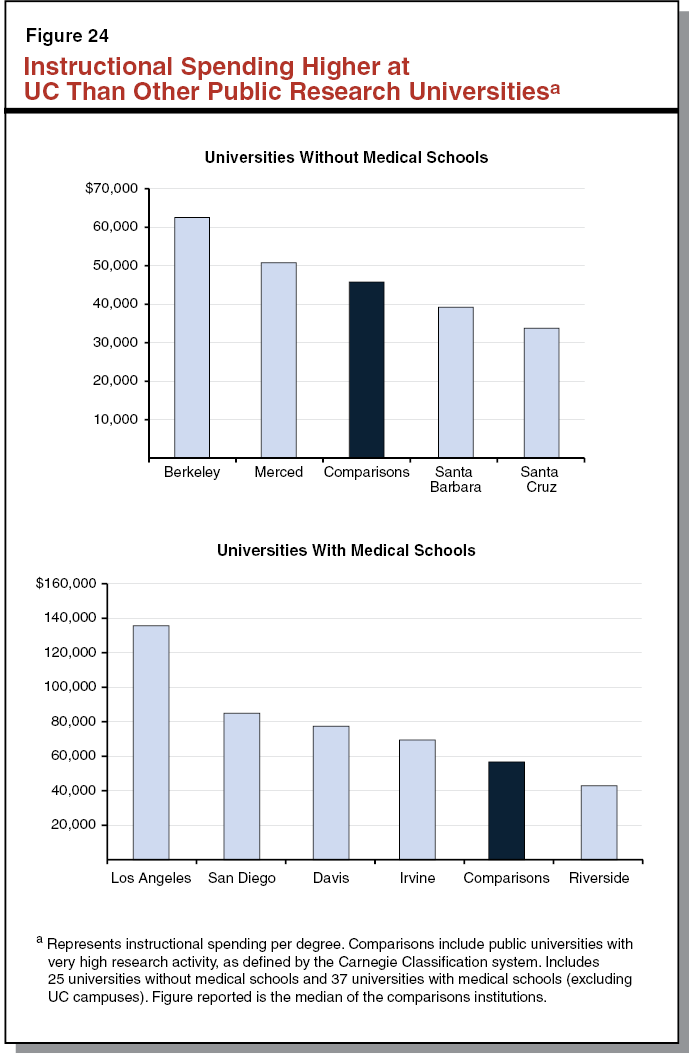

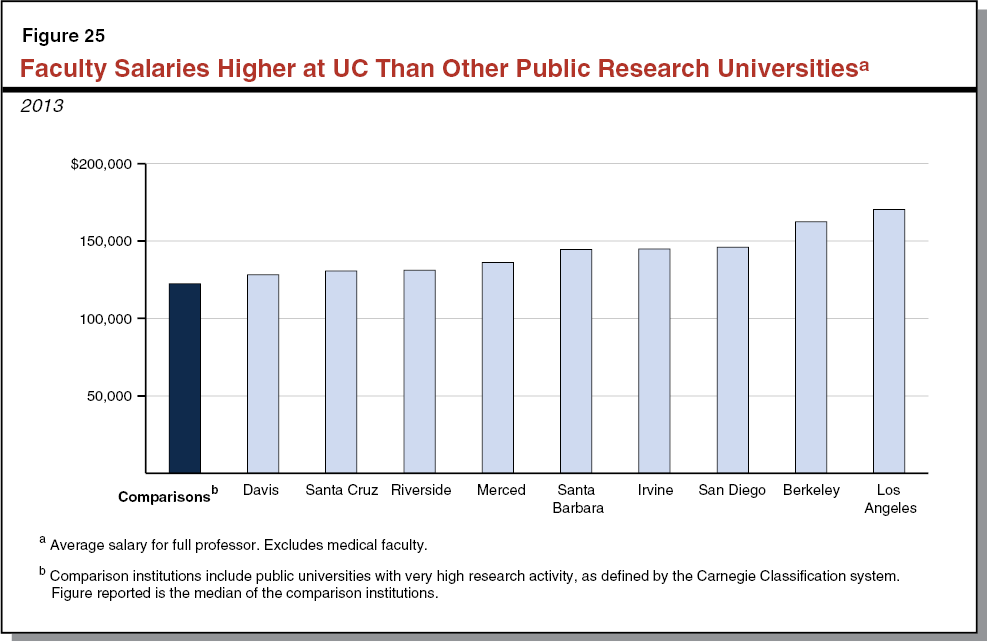

Multiple Issues to Consider, No Easy “Solutions.” This year the state is paying particular attention to UC’s proposed cost increases. To help inform its discussions, we examined how UC’s costs compare with costs at other public universities that also have very high research activity. We found that UC’s instructional spending per degree, noninstructional spending, and average faculty salaries were notably higher than the median of the comparison group. Though UC’s costs are higher in many regards than costs at other public universities with very high research activity, the Legislature may feel these differences are warranted. For example, UC faces higher wage and living costs than much of the rest of the nation and may be more prestigious than some other research universities. Additionally, the state has not given UC explicit direction on the amount of teaching versus research it expects of faculty. Whereas UC costs would be lower if faculty had a higher teaching load, the state has not directly expressed that it desires less research activity. Moreover, a major determinant of costs at UC, and virtually all other research universities, is the instructional delivery model itself. The state has not directly expressed that it desires UC to change this model, with its primary reliance on faculty members with advanced degrees teaching a relatively small number of students in a physical setting.

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. We begin by providing background on higher education funding and expenditures. We then give an overview of the Governor’s higher education budget. In the next five sections, we analyze core aspects of higher education: (1) performance, (2) enrollment, (3) operations, (4) facilities, and (5) tuition and financial aid. In each of these sections, we provide relevant background, describe any related Governor’s proposals, assess those proposals, and make recommendations. The final section consists of a summary of the recommendations we make throughout the report.

This section provides some background information on higher education in California. Below, we first provide an overview of California’s colleges and universities, their missions, and the students they serve. We next summarize all sources of funding for higher education in California. To provide a historical perspective, we then track core funds (including state General Fund and student tuition revenue) over time. To provide another perspective, we also track all education–related spending regardless of fund source.

The Master Plan for Higher Education in California (first established in 1960 and subsequently amended by various bills over the years) set forth different missions and student populations for the state’s public segments. In addition to public higher education, California has a private sector consisting of many nonprofit and for–profit colleges and universities. Figure 1 provides basic information about each segment and sector, described in more detail below.

California Community Colleges (CCC). The CCC system has a broad mission that includes providing citizenship and English as a second language courses, basic skills instruction, career technical education that leads to certificates and credentials, and lower division coursework that leads to associate degrees and transfer to baccaleaurate institutions. The CCC system is open access—meaning any adult may enroll. The transfer process between the open–access CCC and the more selective public universities is a key component of the Master Plan—ensuring all students have an opportunity to earn a bachelor’s degree from a public university even if they did not qualify for university admission directly from high school. The CCC system consists of 112 colleges in 72 districts located throughout the state. The CCC system currently provides credit instruction to 1.1 million full–time equivalent (FTE) students and noncredit instruction to 66,000 FTE students. A Board of Governors oversees the statewide system and appoints a chancellor to run day–to–day statewide operations at the Chancellor’s Office (located in Sacramento).

California State University (CSU). CSU’s mission is undergraduate education for the top one–third of California public high school graduates as well as graduate education through the master’s degree. CSU currently serves 379,000 FTE students at 23 campuses. Of these students, 89 percent are undergraduates and 11 percent are graduate (including postbaccalaureate) students. Nonresident students account for 5 percent of all students. The system is overseen by a 25–member Board of Trustees, with most of the members appointed by the Governor. The Trustees appoint a chancellor that oversees campus presidents and serves as the head of the CSU Chancellor’s Office (located in Long Beach).

University of California (UC). UC’s mission is research; professional, doctoral, and other graduate education; and undergraduate education for the top one–eighth of high school graduates. UC currently serves 249,000 FTE students at ten campuses. Of these students, 80 percent are undergraduates and 20 percent are graduate students. Nonresident students account for 15 percent of all students. The university is overseen by a Board of Regents, comprised mainly of members nominated by the Governor. The Regents appoint a president that oversees campus chancellors and serves as the head of the UC Office of the President (located in Oakland).

Hastings College of the Law (Hastings). Hastings currently serves 970 FTE graduate students in law at its one campus in San Francisco. The college is affiliated with UC but is overseen by a separate Board of Directors, consisting mainly of members nominated by the Governor. Hastings’ Board of Directors appoints a dean to oversee the law school.

Private Colleges and Universities. California also has an estimated 1,300 private colleges and universities. These institutions have a variety of missions, ranging from vocational training for specific industries to education in the liberal arts to specialized graduate and professional programs. Approximately 1,100 private schools are for–profit, such as the University of Phoenix and ITT Technical Institute. Nearly 200 are nonprofit schools (often referred to as independent institutions), such as Stanford University and Saint Mary’s College. About 575,000 FTE students in California attend private postsecondary institutions, with enrollment split about evenly between nonprofits and for–profits. About one in five college students in California attends private colleges and universities. California has a slightly smaller private higher education sector compared to the national average.

Public Higher Education Funded From Several Sources. The state General Fund, student tuition revenue, local property tax revenue, the state lottery, private donations, the federal government, medical center revenue, and auxiliary revenue are the main funding sources supporting public higher education. The first four sources listed are fungible, meaning they can be used for the same purposes. Segments typically use these funds to pay for faculty compensation, instructional materials, academic support, research, public service, and related expenses. The second four sources listed are fungible in some cases but in other cases are legally restricted to supporting certain activities. For example, segments have discretion over the use of some private donations, though many private donors place restrictions on their donations. Most federal funding supports specific research projects. Medical centers and auxiliary enterprises (such as dormitories, cafeterias, and parking garages) generate revenues that typically are used to cover their costs.

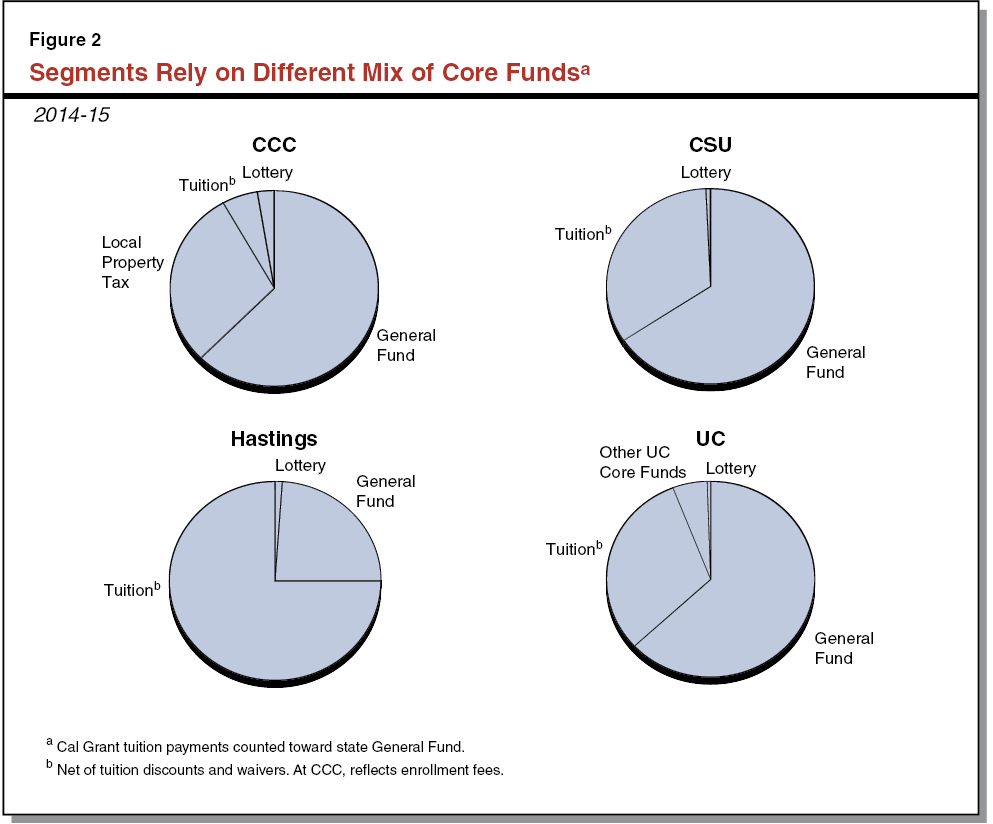

Higher Education Segments Funded From Different Combination of Core Funds. Figure 2 focuses on “core funding,” which typically is defined as state General Fund, student tuition revenue, local property tax revenue, and state lottery funds. (UC has a few other core funds, such as a portion of patent royalty income.) As shown in the figure, the CCC system relies heavily on the state General Fund and local property tax revenue, with only a small share of funding coming from student fees. By comparison, UC and CSU rely heavily on state General Fund and student tuition revenue. Neither UC nor CSU receives any local property tax revenue. Hastings relies to the greatest extent on student tuition revenue, with only about a quarter of its core funding coming from the state General Fund. All four segments receive state lottery funds, though these funds comprise less than 2 percent of their core funding.

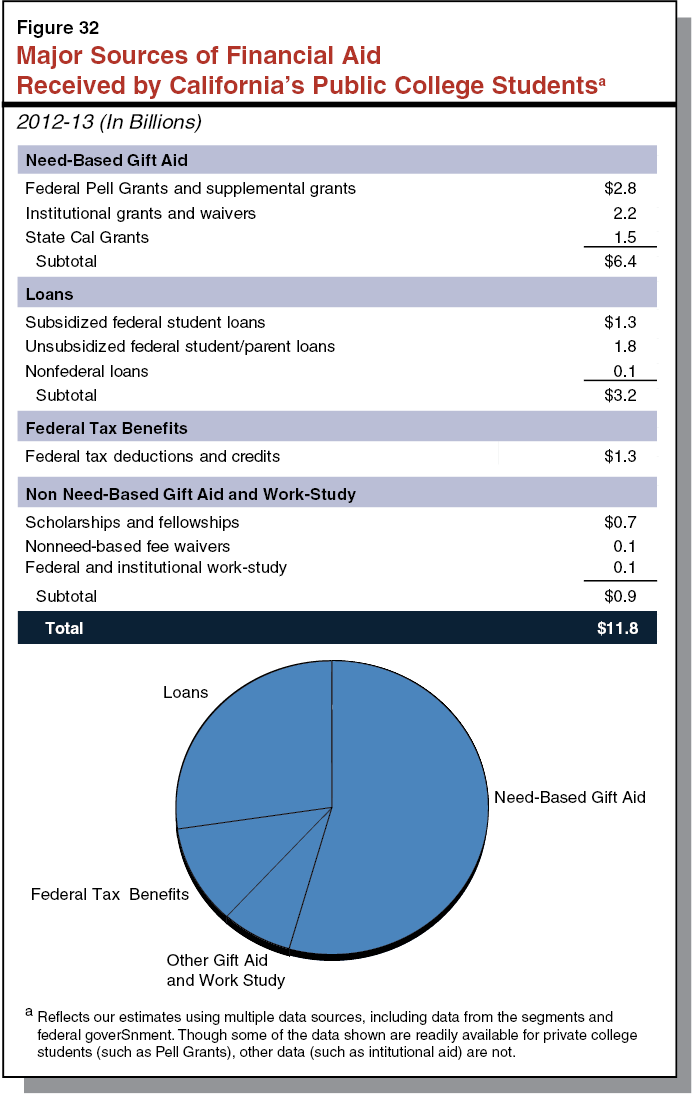

Financial Aid Funded From Various Sources. In addition to direct state General Fund appropriations for each segment, the state supports several student financial aid programs. The largest program, the Cal Grant program, currently provides aid to 276,000 California high school graduates and community college transfer students who meet financial, academic, and other eligibility criteria. An additional 56,000 students currently receive awards through competitive grants. (Though historically the state has covered all Cal Grant costs, in recent years it has used federal funds to offset some Cal Grant costs.) Created more recently (2013), the Middle Class Scholarship currently provides tuition discounts to 81,000 higher income students not benefiting from the Cal Grant program. These and a few other smaller student financial aid programs are administered by the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). In addition to state financial aid, the four segments each provide certain students with institutional financial aid. This aid comes mostly in the form of tuition discounts and fee waivers. The federal government also funds student financial aid in the form of Pell Grants, subsidized student loans, and tax credits and deductions. The segments and the federal government also provide some aid through subsidized work–study programs.

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Funded With General Obligation Bonds. Created by California voters in 2004 through Proposition 71, the Institute supports stem cell research. The Institute does not perform research itself; rather, it solicits research proposals and funds research, training, and new research space throughout the state. Proposition 71 authorized $3 billion in bonds for the Institute. The state issues the bonds to fund the Institute’s operations and then repays the associated debt service from the General Fund.

Private Colleges Mostly Funded With Nonstate Revenues. California’s private higher education sector does not receive core funding directly from the state. Private colleges and universities, however, receive some state funding indirectly through student tuition payments funded by the Cal Grant program. This sector also benefits indirectly from federal financial aid programs.

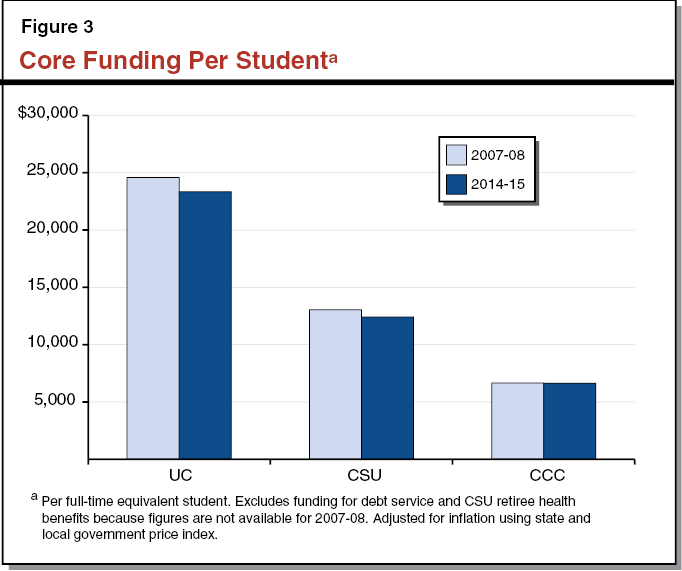

Variety of Perspectives on How to Compare Funding Over Time. Funding can be tracked in various ways—for example, by focusing on a single fund source (such as state General Fund) or a combination of fund sources. Funding also can be tracked in the aggregate or on a per–student basis. Additionally, funding can be shown in actual dollars or inflation–adjusted dollars. Each of these decisions can have major implications on the conclusions drawn from the data. For our comparison below, we focus on core funding per student adjusted for inflation (using the state and local government price index).

Comparing Current Funding to 2007–08 Highlights Effects of Recent Recession. With any trend data, the story told also depends heavily on the starting and ending points selected. For instance, comparing current spending with a historical low point versus a historical high point will portray very different pictures. In recent years, the Legislature has expressed interest in comparing current funding to 2007–08 levels to see the effects of the most recent recession. Thus, for our comparison below, we track funding levels from 2007–08 through 2014–15.

Tracking Core Funding Offers Relatively Comprehensive View of Segments’ Overall Mission. At all three segments, core funding is used for student–driven workload. This workload is associated with core faculty and the time core faculty spends on instruction, research, and public service. (At UC, core faculty devote considerably more time to research than core faculty at CSU and CCC.) In addition to student–driven workload, UC uses some of its core funding for nonstudent–driven workload—particularly university–sponsored research and outreach programs. For example, UC uses some of its core funding to support off–campus agricultural research stations and provide college preparatory outreach programs for high school students.

Change in Per Student Funding Differs By Segment. As shown in Figure 3, inflation–adjusted per–student core funding in 2014–15 compared to 2007–08 is slightly lower at UC, CSU, and CCC (down 5 percent, 4 percent, and 1 percent respectively). Per–student funding at Hastings (not included in the figure) is up sharply (46 percent). The variation results from different decisions made over this time regarding state General Fund support, tuition revenues, and enrollment. For CCC, core funding (including Proposition 98 funding) is up and enrollment is down, but the resulting per–student increase is not sufficient to keep up entirely with inflation. (CCC funding counts toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. See our publication The 2015–16 Budget: Proposition 98 Education Analysis for more information on the minimum guarantee.) For UC and CSU, core funding and enrollment are both up, with per–student funding also falling somewhat behind inflation. For Hastings, the sharp increase largely is attributable to a significant drop in enrollment coupled with higher student tuition.

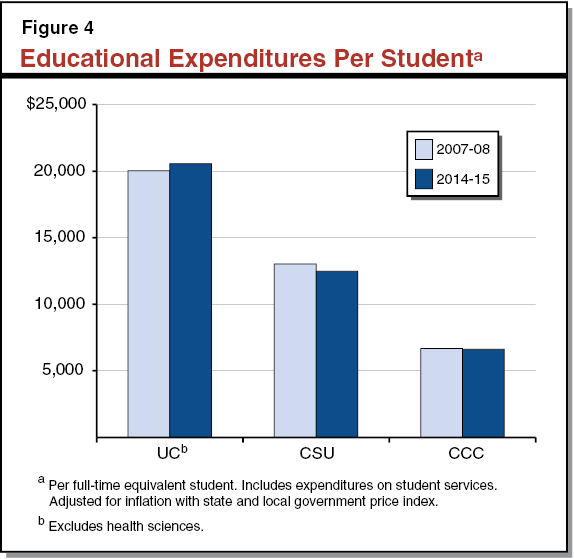

Tracking Spending on Education Offers Somewhat Different Perspective. To offer another perspective on the condition of higher education, we examine education spending patterns from 2007–08 through 2014–15. Three main differences exist between our calculation of core funding per student and education spending per student:

- We include spending from all fund sources, not just core funds. Including noncore funds, such as private donations, provides a broader perspective on educational support (particularly for UC, which raises the greatest amount of private donations among the three segments).

- We focus on education spending, including all core faculty instruction, research, and public service, as well as a portion of academic support, student services, and other operational costs (such as maintenance and utilities) for undergraduate and graduate education. We exclude all health services spending at UC because spending per student tends to be significantly higher in this area. We also exclude spending on sponsored research, public service, auxiliary enterprises, and other spending not closely tied to undergraduate and graduate education. For instance, we exclude UC’s spending for its teaching hospitals and its off–campus agricultural research stations.

- Third, whereas core funding shows the amount of resources available per student, spending per student shows the amount actually spent. The two figures can vary if, for example, a segment chooses not to spend all of its funding in one year (instead putting aside some funds as reserves).

Taken together, education spending per student tends to be somewhat lower than core funding per student at each of the three segments. This is because the effect of including noncore resources is more than offset by the effect of limiting the analysis to actual education expenditures.

Spending Tells Somewhat Different Story for Two of the Four Segments. As shown in Figure 4, inflation–adjusted education spending per student in 2014–15 compared to 2007–08 is somewhat higher at UC (up 2.6 percent) and slightly lower at CSU (down 4 percent) and CCC (down 0.8 percent). At CSU and CCC core funding and education spending trend almost exactly, with 2014–15 levels slightly lower than 2007–08 levels. The difference between core funding and education spending is more notable at the other two segments. At UC, the notable difference between having core funding down by 5 percent and education spending up by 2.6 percent likely is explained by UC being able to rely more on noncore university funds. For Hastings, 2014–15 spending is up 60 percent compared to the 2007–08 spending level. The reason education spending at Hastings is up even more than its core funding (60 percent and 46 percent, respectively) likely is due to the law school’s ability to rely more on noncore university funds, such as private donations (similar to UC).

Governor’s Budget Includes 6 Percent Increase in Core Funding for Higher Education. As shown in Figure 5, the largest year–to–year increases come from the state General Fund and local property tax revenue. A portion of the General Fund increase, however, is due to a decline in federal funds that offset General Fund support for the Cal Grant program. The slight dip in net tuition revenues is unrelated to changes in fee levels but rather is due to higher Cal Grant participation. (Cal Grants are funded by the state and cover eligible students’ tuition costs.) Under the Governor’s budget, CCC receives a relatively large year–to–year increase in core funding (9 percent) whereas UC, CSU, and Hastings receive smaller increases (ranging from 2 percent to 4 percent).

Figure 5

Higher Education Core Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14 Actual

|

2014–15 Estimated

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

UC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$2,844

|

$2,991

|

$3,131

|

$140

|

5%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

2,671

|

2,782

|

2,782

|

—

|

—

|

|

Other UC core funds

|

314

|

323

|

323

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

31

|

39

|

39

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,860)

|

($6,134)

|

($6,274)

|

($140)

|

(2%)

|

|

CSU

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$2,769

|

$3,026

|

$3,179

|

$153

|

5%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

2,145

|

2,133

|

2,139

|

6

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

36

|

59

|

59

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($4,949)

|

($5,219)

|

($5,377)

|

($158)

|

(3%)

|

|

CCC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$4,622

|

$5,019

|

$5,443

|

$424

|

8%

|

|

Local property tax

|

2,178

|

2,321

|

2,628

|

307

|

13%

|

|

Fees

|

412

|

417

|

423

|

6

|

1%

|

|

Lottery

|

193

|

186

|

186

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($7,405)

|

($7,944)

|

($8,680)

|

($737)

|

(9%)

|

|

Hastings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

$33

|

$31

|

$31

|

—

|

1%

|

|

General Funda

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

1

|

13%

|

|

Subtotalsc

|

($43)

|

($42)

|

($43)

|

($2)

|

(4%)

|

|

CSAC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$1,063

|

$1,627

|

$1,940

|

$313

|

19%

|

|

SLOF

|

98

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

N/A

|

|

TANF funds

|

542

|

377

|

286

|

–91

|

–24%

|

|

Other

|

29

|

36

|

15

|

–21

|

–58%

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,731)

|

($2,040)

|

($2,241)

|

($201)

|

(10%)

|

|

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

|

|

General Funda

|

$95

|

$271

|

$383

|

$112

|

42%

|

|

Awards for Innovation in Higher Education

|

|

General Fund

|

—

|

$50

|

$25

|

–$25

|

N/A

|

|

Totalsd

|

$18,904

|

$20,361

|

$21,601

|

$1,241

|

6%

|

|

General Fund

|

$11,403

|

$12,995

|

$14,113

|

$1,118

|

9%

|

|

Net tuition/feesd

|

4,080

|

4,025

|

3,953

|

–73

|

–2

|

|

Local property tax

|

2,178

|

2,321

|

2,628

|

307

|

13

|

|

Other

|

982

|

736

|

624

|

–112

|

–15

|

|

Lottery

|

260

|

284

|

284

|

—

|

—

|

Governor Proposes Major Spending Increases for CCC and Financial Aid. Figure 6 summarizes the Governor’s higher education proposals. By far, the largest spending proposal is to fund CCC for new adult education consortia. (We discuss this proposal in–depth in The 2015–16 Budget: Proposition 98 Analsysis.) Other notable CCC increases relate to enrollment growth, enhancements to instructional programs, and expansion of student support services. The Governor also increases funding to (1) reflect greater student participation in the Cal Grant program and (2) continue phasing in the Middle Class Scholarship program (begun in 2014–15 and scheduled for full implementation in 2017–18). For the universities, the Governor’s only notable proposals are to increase base funding.

Figure 6

Major Higher Education General Fund Spending Changesa

(In Millions)

|

2014–15 Budget Act

|

$12,994

|

|

Pay down CCC mandate backlog

|

$146

|

|

Pay down CCC deferrals

|

94

|

|

Fund Cal Grant program growth

|

69

|

|

Extend CCC Career Technical Education Pathways (one time)

|

48

|

|

Recognize Middle Class Scholarship savings

|

–27

|

|

Other

|

54

|

|

Total 2014–15 Changes

|

$385

|

|

Revised 2014–15 Spending

|

$13,378

|

|

Fund new adult education consortia

|

$500

|

|

Increase base funding for UC, CSU, and Hastings

|

240

|

|

Augment CCC student support programs

|

200

|

|

Augment CCC funding (to be specified in May Revision)b

|

170

|

|

Fund Cal Grant program growth

|

129

|

|

Pay down CCC mandate backlog

|

125

|

|

Provide CCC apportionment increase

|

125

|

|

Fund 2 percent CCC enrollment growth

|

107

|

|

Provide 1.58 percent CCC cost–of–living adjustment

|

92

|

|

Fund Middle Class Scholarship at statutory level

|

72

|

|

Fund deferred maintenance at UC and CSU

|

50

|

|

Fund certain CCC noncredit courses at credit rate per state law

|

49

|

|

Increase CCC funding for apprenticeships

|

29

|

|

Add one–time funding for Awards for Innovation

|

25

|

|

Backfill federal grant for financial aid outreach and awards

|

15

|

|

Add funding to improve technology used to administer Cal Grants

|

1

|

|

Remove one–time funding for legislative priorities at UC

|

–4

|

|

Remove CCC enrollment restoration funding

|

–47

|

|

Remove one–time funding for Awards for Innovation

|

–50

|

|

Remove one–time CCC funding, including prior–year mandate and deferral payments

|

–647

|

|

Other

|

–160

|

|

Total 2015–16 Changes

|

$1,021

|

|

2015–16 Proposed Spending

|

$14,399

|

Governor Proposes Making UC Adhere to Certain Conditions Prior to Receiving State Funds. The administration stipulates that UC is to (1) not increase tuition, (2) not increase nonresident enrollment, and (3) take action to constrain costs. UC must verify to the Department of Finance (DOF) its compliance with these conditions prior to the release of state funds. (At their November board meeting, the UC Board of Regents approved a 5 percent tuition increase for 2015–16. We discuss issues relating to UC’s tuition increase in the box) The Governor does not place these conditions on CSU or Hastings, though he has indicated he expects both segments to not increase tuition.

Regents’ Budget Assumes Much Higher Spending Than Governor’s Plan. The budget the UC Board of Regents adopted in November 2014 includes total spending of $459 million—$340 million more than the Governor’s proposed base augmentation. Of the $459 million, UC identifies $125 million in “mandatory costs,” including retirement contributions, health benefit increases, and its faculty merit program; $179 million for three “high–priority costs” consisting of compensation increases ($109 million), deferred maintenance ($55 million), and other high–priority capital needs ($14 million); $73 million for institutional financial aid; $60 million for an “investment in academic quality;” and $22 million for “enrollment growth” (intended mostly to serve existing students the university believes to be “unfunded”).

Regents Adopt Tuition Increase to Pay for Part of Increased Spending. To pay for the increased expenditures above the Governor’s level, the university’s budget plan relies on a variety of funding sources other than the state General Fund, including a 5 percent systemwide tuition increase (that would apply to resident and nonresident students) and additional private donations. The university estimates the systemwide tuition increase would result in $98 million in additional revenue (after taking into account institutional financial aid that would provide tuition discounts and fee waivers for financially needy students). The university’s budget plan also increases nonresident enrollment, thereby generating additional associated revenues, and builds in some additional administrative cost savings.

UC Plans to Sharply Curtail Resident Enrollment if Systemwide Tuition Remains Flat. The 2014–15 budget required UC to provide a “sustainability plan” to the Department of Finance (DOF) and the Legislature in November 2014. The report had to include UC’s plan for expenditures and enrollment using revenue assumptions provided by DOF. The DOF’s revenue assumptions included $119 million in state support and no additional tuition revenue. Under these assumptions, UC reported back to the state that it would maintain the same level of expenditures included in the Regents’ budget. To accommodate the higher spending, UC reported it would increase nonresident enrollment by about 3,000 students (8 percent) and decrease resident enrollment by about 4,000 students (2 percent). This would allow the university to fund the expenditure increases because nonresidents pay significant supplemental tuition beyond the systemwide charge that applies to both residents and nonresidents.

In this section, we provide background on the state’s higher education goals and performance measures, review the segments’ recent reports on their performance outcomes, and assess these results. We then discuss some underlying causes of poor performance and recommend two legislative actions that would help the state target resources toward improving student outcomes.

State Recently Adopted BroadGoals for Higher Education. Chapter 367, Statutes of 2013 (SB 195, Liu), establishes three goals for higher education. The goals are: (1) improve student access and success, such as by increasing college participation and graduation rates; (2) better align degrees and credentials with the state’s economic, workforce, and civic needs; and (3) ensure the effective and efficient use of resources to improve outcomes and maintain affordability. The law states the Legislature’s intent that these goals guide state budget and policy decisions for higher education. The law also calls for the creation of performance measures, or “metrics,” to monitor progress toward these goals. A working group with legislative and administration representatives met with national higher education experts during 2014 to discuss performance metrics. The experts’ main recommendation was for policymakers to adopt a statewide goal for educational attainment and related goals for annual increases in the number of degrees and certificates earned. Segment–specific targets would roll up into these statewide goals.

State Adopted Performance Measures for Universities. In addition to this policy development, the 2013–14 budget package codified a new requirement for UC and CSU to report annually on a number of performance outcomes. The universities are required to report by March 15 of each year their graduation rates, spending per degree, and the number of transfer and low–income students they enroll, among other measures.

Universities Directed to Set Performance Targets. Provisional language in the 2014–15 Budget Act required the UC and CSU governing boards to adopt three–year sustainability plans by November 30, 2014. Required information in the plans includes targets for each of the statutory performance measures referenced earlier above as well as resident and nonresident enrollment projections for each of the three years (2015–16 through 2017–18). The language directed the universities to base their plans on General Fund and tuition assumptions provided by DOF. Accordingly, the universities provided projections of their likely performance under these assumptions.

Overall, Universities’ Targets Somewhat Lackluster. Figure 7 shows the statutory performance measures used for budgeting purposes, along with the segments’ corresponding performance targets. (Generally, the data compare the segments’ actual performance in 2013–14 with their targets for 2017–18.) As shown in the figure, CSU set modest targets for graduation rates and degree completions, both overall and for specific disadvantaged groups. For example, CSU set a goal of raising its six–year graduation rate for low–income students from 46 percent to 48 percent by 2017–18. For units per degree (an efficiency measure), CSU projected no reduction in units per degree for freshmen and a reduction of only one unit for transfer students (despite considerable efforts the past few years to streamline the transfer pathway from CCC to CSU). For funding per degree (another efficiency measure), CSU projected becoming less efficient between 2013–14 and 2017–18, with funding per degree set to increase almost $5,000 per student during period. UC’s goals in these areas were similar, with modest projected improvement in graduation rates, no improvement in units per degree, and a notable increase in funding per degree.

Figure 7

UC and CSU Performance Measures and Targetsa

|

Metric

|

University of California

|

|

California State University

|

|

Current Performanceb

|

Targetc

|

|

Current Performanceb

|

Targetc

|

|

CCC Transfer Students Enrolled. Number and as a percent of undergraduate population.

|

33,715 (19%)

|

33,358 (18%)

|

|

137,797 (36%)

|

142,226 (36%)

|

|

Low–Income Students Enrolled. Number and as a percent of total student population.

|

76,634 (42%)

|

60,667 (32%)

|

|

170,491 (44%)

|

167,755 (42%)

|

|

Graduation Rates.d

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) 4–year rate—freshman entrants.

|

62%

|

66%

|

|

18%

|

19%

|

|

(2) 4–year rate—low–income freshman entrants.

|

56%

|

60%

|

|

11%

|

11%

|

|

(3) 6–year rate—freshman entrants (CSU only).

|

—

|

—

|

|

53%

|

55%

|

|

(4) 6–year rate—low–income freshman entrants (CSU only).

|

—

|

—

|

|

46%

|

48%

|

|

(5) 2–year rate—CCC transfer students.

|

54%

|

58%

|

|

27%

|

29%

|

|

(6) 2–year rate—low–income CCC transfer students.

|

50%

|

54%

|

|

25%

|

27%

|

|

(7) 3–year rate—CCC transfer students (CSU only).

|

—

|

—

|

|

63%

|

68%

|

|

(8) 3–year rate—low–income CCC transfer students (CSU only).

|

—

|

—

|

|

62%

|

67%

|

|

Degree Completions. Annual degrees awarded for:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Freshman entrants

|

31,866

|

36,200

|

|

34,254

|

41,966

|

|

(2) CCC transfer students

|

14,651

|

15,400

|

|

43,741

|

44,673

|

|

(3) Graduate students

|

17,300

|

20,000

|

|

18,574

|

19,308

|

|

(4) Low–income students

|

21,469

|

22,700

|

|

40,318

|

41,302

|

|

(5) All students

|

65,431

|

72,200

|

|

103,637

|

112,457

|

|

First–Year Students on Track to Graduate on Time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percentage of first–year undergraduates earning enough credits to graduate within four years.

|

51%

|

51%

|

|

48%e

|

54%e

|

|

Funding Per Degree. Core funding divided by number of degrees for:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) All programs.

|

$98,300 (2012–13)

|

$112,900

|

|

$36,300 (2012–13)

|

$41,100

|

|

(2) Undergraduate programs only.

|

Not reported

|

Not reported

|

|

Not reported

|

$50,700

|

|

Units Per Degree. Average course units earned at graduation for:

|

Quarter Units

|

|

Semester Units

|

|

(1) Freshman entrants.

|

187

|

187

|

|

139

|

139

|

|

(2) Transfers.

|

100

|

100

|

|

141

|

140

|

|

Degree Completions in STEM Fields. Number of STEM degrees awarded annually to:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Undergraduate students.

|

16,327

|

18,000

|

|

17,020

|

21,574

|

|

(2) Graduate students.

|

8,700

|

10,000

|

|

3,817

|

4,105

|

|

(3) Low–income students.

|

7,027

|

7,400

|

|

7,128

|

7,828

|

UC and CSU Have Very Different Enrollment Strategies. As required by provisional budget language, UC and CSU also set forth resident and nonresident enrollment targets. Figure 8 compares current enrollment with the segments’ targets under the Governor’s proposed funding levels. As shown in the figure, UC is planning to reduce resident undergraduate enrollment by almost 16,000 students (10 percent) over the period while more than doubling nonresident undergraduate enrollment. In contrast, CSU is planning to increase both resident and nonresident enrollment by 3 percent.

Figure 8

UC and CSU Enrollment Targets Under Administration’s Revenue Assumptions

|

|

2014–15

|

2017–18

|

Change from 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

UC

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resident undergraduate

|

158,410

|

142,678

|

–15,732

|

–10%

|

|

Nonresident undergraduate

|

23,832

|

47,939

|

24,107

|

101

|

|

Graduate/professional

|

49,892

|

52,142

|

2,250

|

5

|

|

Totals

|

232,134

|

242,759

|

10,625

|

5%

|

|

CSU

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resident

|

420,271

|

433,004

|

12,733

|

3%

|

|

Nonresident

|

22,274

|

22,949

|

675

|

3

|

|

Totals

|

442,545

|

455,953

|

13,408

|

3%

|

CCC Recently Revised Accountability System. In 2012, the CCC Student Success Task Force recommended the implementation of a new accountability framework. The framework replaces previous annual accountability reports required by 2004 legislation. The core of the new framework is the Student Success Scorecard, which contains information on student completion of a degree, certificate, or transfer preparation and several progress indicators (remedial course progression, student persistence for three terms, and completion of 30 units). All measures are reported for all students, separately by age group and race/ethnicity, and separately for college–prepared and remedial students. The scorecard contains both systemwide and district–level data and is publicly available online.

Community Colleges and CCC System Also Required to Adopt Targets. The 2014–15 budget package required each community college and the CCC Board of Governors to adopt goals and targets for student performance by June 30, 2015. The Board of Governors adopted systemwide targets in July 2014 primarily based on Student Success Scorecard measures, shown in Figure 9. (A particular college’s goals may be more or less ambitious than the systemwide goals.)

Figure 9

CCC Systemwide Performance Measures and Targets

|

Metric

|

Recent Performancea

|

Target

|

|

Completion Rate. Completion defined as: (1) earning an associate degree or credit certificate, (2) transferring to a four–year institution, or (3) completing 60 UC/CSU transferable units with a GPA of at least 2.0 within 6 years of entry.

|

41% for underprepared 70% for prepared 48% overall

|

Increase rate by 1 percent (of rate) annually.

|

|

Remedial Progress Rate. Success in college–level English or math class for students who took remedial English, remedial math, or English as a second language.

|

31% in math44% in English

|

To be determined.

|

|

CTE Completion Rate. CTE students who completed a degree, certificate, or 60 transferable units, or transferred.

|

54%

|

To be determined.

|

|

Associate Degrees for Transfer. Number of these degrees completed annually.

|

5,365

|

Increase number by 5 percent annually for 5 years.

|

|

Equity Rate. Index showing whether a subgroup’s completion rate is low compared with overall completion rate. An index of less than 1.0 indicates underperformance.

|

0.78 African American0.78 American Indian0.81 Hispanic0.89 Pacific Islander1.09 White1.29 Asian

|

Increase annually until all indices are 0.80 or above.

|

|

Education Plan Rate. Share of students who have an education plan.

|

To be determined.

|

To be determined.

|

|

FTE Years Per Completion. A measure of efficiency showing amount of instruction, on average, required for each completion. (A student completing 60 units, the standard length of an associate degree or preparation for transfer, would generate two FTE years.)

|

5.21 for underprepared2.84 for prepared4.33 overall

|

Decrease measure (increase efficiency).

|

|

Participation Rate. Number of students ages 18–24 attending a community college per 1,000 California residents in the same age group.

|

261

|

Increase participation rate each year.

|

|

Participation Among Subgroups. Index comparing a subgroup’s share of enrollment with its share of the state population. An index of less than 1.0 indicates underrepresentation.

|

0.87 White 1.01 Hispanic 1.01 African American 1.22 Asian

|

Maintain index above 0.80 for all subgroups.

|

State Uses Performance Measures for Determining Institutional Cal Grant Eligibility. In response to concerns about the quality of some postsecondary institutions, California in 2011 adopted eligibility standards for colleges participating in the Cal Grant programs. Colleges with a substantial proportion of their students taking out federal student loans now must meet two Cal Grant eligibility criteria. Specifically, these colleges must maintain student loan default rates below 15.5 percent (measured over the first three years of repayment) and graduation rates above 30 percent. (A statutory amendment temporarily reduced the graduation rate requirement to 20 percent from 2014–15 through 2016–17.)

Performance Not Linked With Base Funding. As noted, the state’s goals for higher education and associated performance measures are intended to guide state budget and policy decisions, though Chapter 367 does not explain exactly how this is to be accomplished. In 2012 and 2013, the Governor proposed a formula to tie future funding increases for the universities (but not the community colleges) to their success in meeting specific performance targets. The Legislature did not adopt the proposed performance funding formula, opting instead to establish performance measures and reporting requirements without linking them directly to funding.

Some Targeted Funding Provided in Recent Years to Boost Performance. The Governor and Legislature have funded various initiatives to improve university and community college performance. Most notably, the state has provided large ongoing augmentations in each of the last two years for CCC’s Student Success and Support Program, with funding $220 million higher in 2014–15 than 2012–13. This program funds assessment, placement, and orientation services for new CCC students, as well as academic counseling and tutoring for both new and continuing students. The program also funds efforts to improve access and outcomes for disadvantaged groups. The 2013–14 budget also included $17 million for CCC (and encouraged UC and CSU to spend $10 million each of their base funding increases) toward online initiatives intended to expand students’ access to courses and improve student success. In addition, the 2014–15 budget included $50 million in one–time funding to promote innovative models of higher education at CCC, CSU, and UC campuses. The 2014–15 budget also included $3.6 million for the CCC Chancellor’s Office to offer greater assistance to community colleges seeking to improve their performance.

This section highlights performance for each segment based on three student performance measures: progress upon completing their first year, graduation/completion rates, and total unit taking. These three measures tend to be among the most meaningful measures of institutional performance, tapping elements of both effectiveness and efficiency. The segments’ results are from their 2014 performance reports, as their 2015 reports are not due until March 15. Because the segments use internal data that is not directly comparable with publicly available national data, we make only general comparisons with the performance of other institutions.

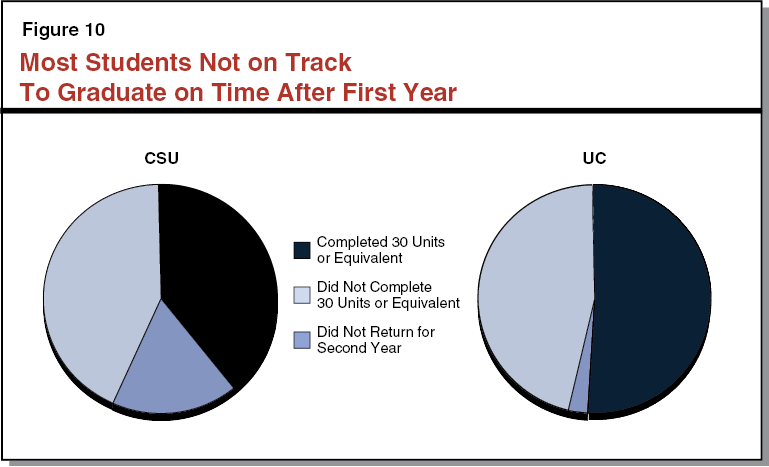

Most Students Not on Track After First Year. Upon completing their first year, only about half of UC students and 40 percent of CSU students are on track to graduate within four years (measured by the number of units they completed), as shown in Figure 10. This indicator is important because full–time enrollment and early credit accumulation are associated with college completion. CCC does not have a comparable measure for units completed in the first year. Instead, the system measures a “remedial progress rate” indicating the share of students who took remedial courses in math or English and successfully completed a college level course in the same subject within six years of entering CCC. For the 2007–08 cohort of entering students, the remedial progress rate was 31 percent in math and 44 percent in English. This indicator is important because the vast majority of entering CCC students are unprepared for college–level coursework.

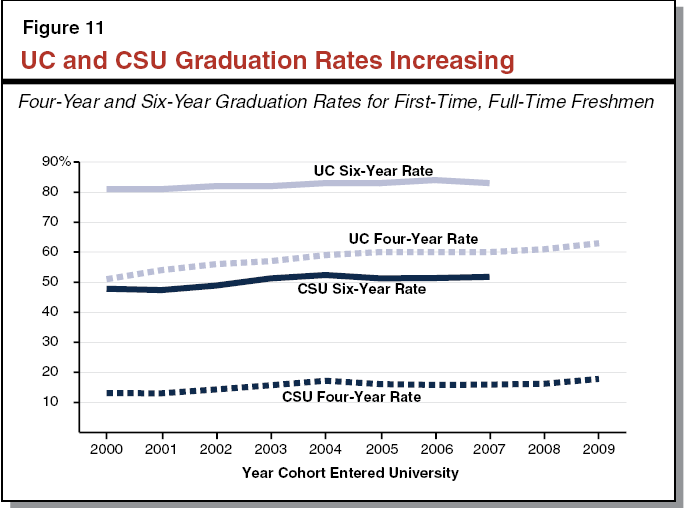

UC and CSU Graduation Rates Increasing. As shown in Figure 11, graduation rates have increased somewhat in recent years at UC and CSU. Although four–year graduation rates are significantly lower than six–year rates at the universities, the four–year rates have been increasing more rapidly. At UC, slightly more than 60 percent of students graduate within four years and slightly more than 80 percent of students graduate within six years. Both UC’s four–year and six–year rates are substantially higher than the average for other public research universities. CSU’s four–year graduation rate is significantly lower than the average for large public master’s universities, whereas its six–year graduation rate is comparable to the average. Even the six–year rate, however, is disappointing—barely over half of entering full–time freshmen complete a CSU degree within six years, and most of the other half never complete their degrees.

CCC Completion Rates Declining Slightly. The community colleges define completion rates somewhat differently from the universities. Instead of measuring the share of entering students who complete a degree within a specified period, CCC measures the success of a “completion cohort.” A student in a completion cohort is one who enters CCC as a first–time student, enrolls in six units within three years of first enrolling, and attempts at least one math or English course during that period (typically an indicator that the student has some academic goal). A successful completion outcome is earning an associate degree or a credit certificate, transferring to a four–year institution, or becoming “transfer prepared” by successfully completing 60 transferable units with at least a “C” average. (The colleges have a similar completion measure for students pursuing noncredit certificates and credentials.) CCC completion rates tend to rise after state funding increases, as more courses become available for students, and decline following reductions in funding. As Figure 12 shows, the most recent available completion rates—for cohorts entering CCC before 2010–11—have been declining. Many CCC students enroll part–time and take several years to achieve a completion outcome.

Excess Units a Concern. Students at all three segments tend to take more courses than needed to obtain a bachelor’s degree. CSU’s 2013 graduating class had accumulated an average of 21 semester units (seven courses) beyond the typical 120 semester unit degree requirement. UC’s 2013 graduating class had accumulated an average of seven quarter units (nearly two courses) of UC credit beyond the typical 180 quarter unit degree requirement. CCC students, on average, generate more than four FTE years to complete an associate degree or certificate or prepare for transfer. A student completing 60 units, the standard length of an associate degree, would generate two FTE years.

Causes of Poor Performance Under Review. All of the segments have been examining to some degree their institutional policies and practices (such as their availability of course sections and support services) as well as various student factors (such as unmet financial need, time dedicated to employment, and students’ academic choices) to determine what might be causing improvement in some areas and lingering performance problems in other areas. In response to its performance issues, CCC has taken the most comprehensive approach by convening a Student Success Task Force to identify common barriers to student success and recommend solutions. To date, CSU has taken a more targeted approach—conducting a study of courses with high failure rates and providing funds to improve instruction in those courses. UC has not undertaken a systemwide study or implemented systemwide improvement efforts, instead prioritizing select campus–based initiatives. For example, UC Santa Cruz formed an Undergraduate Student Success Team at the request of its provost to develop recommendations for improving undergraduate retention rates, graduation rates, and time to degree at the campus.

Recent Research Provides Some Guidance. Research studies examining undergraduate students and institutions that perform better than would be expected—given their student demographics and preparation—provide some guidance regarding practices associated with better student learning and completion outcomes, but these studies differ in their findings. The Association of American Colleges and Universities promotes several “high impact practices” that research has associated with learning gains and graduation. These include first–year seminars and experiences involving regular faculty contact with small groups of students, learning communities in which students take a series of related courses together, writing–intensive courses, undergraduate research, and capstone projects. The advocacy group Complete College America promotes research–based strategies associated primarily with improved college completion. These include guided degree pathways (that is, degree programs with clear requirements and limited choices for students), structured schedules, instructional support for students with remedial needs while they complete mainstream courses, and full–time enrollment. Studies focusing on community college student success, primarily from the Community College Research Center at Columbia Teacher’s College, identify a somewhat different set of factors. These include intensive academic planning and advising for students, small class sizes, special supports for students at risk of academic failure, various other support services and student engagement strategies that are well coordinated, and a data–driven focus on retention and graduation rates (along with ambitious goal–setting for these rates). These studies also mention faculty dedication, professional development focused on improving teaching, and a high proportion of full–time instructors, as well as factors that are more difficult to quantify (and replicate), such as the effects of good leadership promoting systemic improvements and a campus culture of using evidence to continuously assess and improve policies and practices.

Segments Currently Implementing Some Initiatives to Improve Performance. The higher education segments have initiated some activities to improve student outcomes. CSU’s Student Success Initiative aims to increase degree completion rates and reduce units per degree and achievement gaps. The initiative includes activities that are consistent with both the strategies CSU has identified for overcoming barriers to student success and the recommended practices from recent research. The system is enhancing student advising, remediation, and a variety of other support services; implementing a data system that will provide timely and useful information to campuses on students’ time to degree term–to–term retention; and reducing student–to–faculty ratios. CCC is in the process of implementing the 22 recommendations of its Student Success Task Force, including enhancing student support services and performance measurement and increasing the proportion of full–time faculty in the system.

Require Segments to Include External Comparisons. We recommend the Legislature direct each of the segments to compare its performance against external benchmarks—in addition to comparing against its own targets—in its annual performance report. Comparisons should reflect the performance of public institutions serving similar students in other states. If in the future the state identifies targets for the segments, the Legislature could direct the segments to use these targets for comparisons.

Require Segments to Report on Strategies for Improvement. We also recommend the Legislature amend statute to require the segments to include an analysis of current performance and strategies for improving it in their annual performance reports. The analyses could help the Legislature track how each segment is approaching its key performance issues. For example, CSU’s analysis could explain why it believes its four–year graduation rates are significantly below those of other large public master’s universities, or why students take fewer units in their first year but more units overall than required to graduate. A better understanding of the reasons for poor performance would help the state better target resources toward improving outcomes.

In this section, we first provide background on systemwide resident enrollment at all three segments, covering the state’s eligibility policies, traditional approach to setting systemwide enrollment targets, and enrollment funding calculations. We then summarize and assess the Governor’s resident enrollment proposals and make associated recommendations. We next focus on issues relating specifically to the allocation method the CCC Chancellor’s Office uses to distribute enrollment funding among community colleges campuses. We then turn to nonresident enrollment, particularly exploring the balance of resident and nonresident enrollment at UC.

1960 Master Plan Differentiates Among the Three Segments. The state’s Master Plan for Higher Education establishes different eligibility requirements, missions, and costs for each of the three higher education segments. The Master Plan provides the broadest level of access to CCC because it (1) has the broadest mission (including vocational training leading to certificates and credentials, adult education, and instruction leading to associate degrees and transfer) and (2) is the least expensive per student. The universities, by contrast, are more restricted in access because (1) their missions are more narrowly focused on undergraduate and graduate education and (2) they are more expensive per student.

All Adult Californians May Attend Community Colleges. The CCC system is known as an “open access” system because it is open to all Californians 18 years or older. That is, the CCC system has no application process to screen out or select certain students. While CCC does not deny admission to students, it also does not guarantee access to particular classes.

Master Plan Sets Freshman Eligibility Pools at UC and CSU. The Master Plan calls for UC to draw its incoming freshman class from the top 12.5 percent (one–eighth) of public high school graduates. It calls for CSU to draw its applicant pool from the top 33 percent (one–third) of public high school graduates. The Master Plan also allows the universities to admit resident private high school graduates and nonresident students if these applicants meet similar academic standards as eligible public high school graduates.

Master Plan Establishes Minimum Qualifications for Students Transferring to UC and CSU. The Master Plan calls for UC and CSU to accept qualified transfer students who complete 60 units of transferrable credit at a community college and meet a minimum grade point average (GPA) requirement. The minimum GPA is 2.4 for UC and 2.0 for CSU. The Master Plan also calls on UC and CSU to maintain at least 60 percent of their total enrollment as upper–division to allow room for transfer students (who typically transfer as upper–division students). To achieve this target, the universities typically aim to admit one transfer student for every two freshmen. Though not part of the Master Plan, recent legislation—Chapter 428, Statutes of 2010 (SB 1440, Padilla)—also requires CSU to accept applicants who earn new associate degrees for transfer from the community colleges.

Universities Supposed to Align Admission Policies With Freshman Eligibility Pools. Both universities require freshman applicants to complete a set of high school coursework, including history, math, and science courses, known as “A through G” (A–G). These coursework requirements primarily are intended to prepare students for college–level work. In 2012–13, 39 percent of high school graduates had successfully completed A–G coursework. UC and CSU have additional admission criteria, including requiring certain test scores and GPAs, such that they are supposed to be drawing from within their respective eligibility pool.

Freshman Eligibility Studies Assess University Compliance With Master Plan. To gauge whether the universities were drawing from their Master Plan pool of public high school graduates, the state in the past funded what were known as “eligibility studies.” As part of these studies, UC and CSU admission counselors would examine a sample of public high school transcripts and determine the number of students the universities would have admitted had these students applied. If the proportion of transcripts eligible for admission was significantly different from 12.5 percent and 33 percent for UC and CSU, respectively, the universities adjusted their admission policies accordingly. For example, UC tightened its admission criteria after an eligibility study conducted in 2003 found it drawing from the top 14.4 percent of public high school graduates.

State No Longer Routinely Conducting Freshman Eligibility Studies. Typically, the state conducted an eligibility study every three to five years but in recent years it has abandoned this longstanding practice. The state last conducted an eligibility study eight years ago (in 2007). In 2014, the Governor vetoed AB 2548 (Ting), which would have funded a new study.

Transfer Eligibility Tracked by UC and CSU. Because the Master Plan sets the minimum admission standards for transfer students, eligibility studies are not needed for them as they are for freshmen. Instead, the universities are able to track whether they are admitting all transfer students meeting the Master Plan’s admission standards.

Master Plan Does Not Include Eligibility Criteria for Graduate Students. Instead, the Master Plan calls for the universities to consider graduate enrollment in light of workforce needs, such as for college professors and physicians.

Segments Differ in Service Regions. Community colleges primarily are intended to serve the educational needs of their surrounding communities, providing access to all students living in the vicinity. Somewhat similarly, each CSU campus has a designated geographic service area comprised of school and community college districts, with applicants from those districts considered to be “local.” CSU campuses are expected to prioritize local applicants for admission over nonlocal applicants. UC, by contrast, is a statewide system, without regional service areas. Though UC guarantees eligible undergraduate students access to the system, it does not guarantee them admission to a particular campus. UC refers eligible students not admitted to their campus or campuses of choice to another campus with room for them (currently, the Merced campus).

Demographic Changes Affect Enrollment Demand. Other factors being equal, an increase in the number of California public high school graduates causes a proportionate increase in the number of students eligible to enter UC and CSU as freshmen. Similarly, increases in the state’s traditional college–age population generally correspond with increases in UC and CSU eligible students since most university students fall into this demographic group. The CCC system enrolls students from a broader age group but its enrollment also is affected by changes in the college–age population and overall adult population in California.

College Participation Rates Another Factor in Enrollment Demand. For any subgroup of the general population, the percentage of individuals who are enrolled in college is that subgroup’s college participation rate. For example, the participation rate of the traditional college–age population is the number of 18 to 24 year olds attending college divided by the total number of 18 to 24 year olds. Other factors remaining constant, if participation rates increase (or decrease), then enrollment demand increases (or decreases).

State Workforce Planning Also Could Affect Enrollment Decisions. The state for decades has viewed university enrollment primarily in terms of undergraduate eligibility and access. As discussed in the “Performance” section of this report, the Legislature recently enacted Chapter 367, which, in addition to access, established a number of other goals related to higher education. These new goals could provide other perspectives on enrollment demand. For example, the state could consider undergraduate enrollment in the context of projected workforce needs. In the past, the state has done this in only selective cases, such as to address nursing shortages.

Higher Education Enrollment Traditionally Funded on a Per–Student Basis. Under the traditional approach to funding enrollment, the state first determines the growth rate in enrollment from the current year to the budget year based on the factors discussed above. It then sets an enrollment target for the budget year specifying how many students it expects each segment to serve. The state typically has set one overall enrollment target for each segment (not separate targets for undergraduate and graduate students or separate targets by academic discipline). If a segment’s overall enrollment target increases, then the state decides how much associated funding to provide for enrollment growth. (As an exception to these practices, the state traditionally has not provided enrollment funding to Hastings. Instead, the state provides unallocated base increases and gives discretion to the school in setting its enrollment level.)

UC and CSU Enrollment Growth Traditionally Funded Based on Marginal Cost Formula. In the case of the universities, the state for decades funded enrollment growth based on the estimated cost of admitting each additional student. It used a marginal cost per student formula. This formula assumed the universities would hire a new professor for roughly every 19 additional students. It linked the cost of the new professor to the average salary of newly hired faculty. The formula also included the average cost per student for academic and instructional support, student services, instructional equipment, and operations and maintenance of physical infrastructure. The marginal cost formula was based on the cost of all enrollment (undergraduate and graduate students and all academic disciplines excluding health sciences).

Enrollment Funding Not Factored Into Recent Budget Decisions for UC and CSU. In recent years, the state has not consistently tied funding for the universities to an enrollment target or marginal cost formula. As shown in Figure 13, the state has not set enrollment targets for UC and CSU in four of the last eight years. Without enrollment–based budgeting, the state and the universities have come to disagree over how many students the state has funded the universities to serve. Both UC and CSU now assert they have more enrolled resident students than funded by the state.

Figure 13

State Has Not Been Using University Enrollment Targets on a Consistent Basis

Full–Time Equivalent (FTE) Students

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

UC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrollment target

|

198,455

|

None

|

None

|

209,977

|

209,977a

|

209,977a

|

None

|

None

|

|

Actual enrollment

|

203,906

|

210,558

|

213,589

|

214,692

|

213,763

|

211,212

|

210,986

|

211,267

|

|

Percent change in actual enrollment

|

|

3.3%

|

1.4%

|

0.5%

|

–0.4%

|

–0.5%

|

–0.1%

|

0.1%

|

|

CSU

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrollment target

|

342,553

|

None

|

None

|

339,873

|

331,716a

|

331,716a

|

None

|

None

|

|

Actual enrollment

|

353,915

|

357,223

|

340,289

|

328,155

|

341,280

|

343,227

|

351,955

|

360,000

|

|

Percent change in actual enrollment

|

|

0.9%

|

–4.7%

|

–3.6%

|

4.0%

|

–0.4%

|

2.5%

|

2.3%

|

State Continues to Use Enrollment Funding for CCC. The budget annually sets an enrollment target for CCC. State law requires that the system’s annual budget request for enrollment growth be based, at minimum, on changes in the adult population and excess unemployment (defined as an unemployment rate higher than 5 percent). CCC also may request enrollment growth to cover “unfunded” (or over cap) enrollment. The Governor and Legislature do not have to approve enrollment growth at the requested level, however. Their decisions tend to reflect the state’s budget condition—increasing the enrollment target when revenues increase (and the Proposition 98 guarantee rises) and reducing it when revenues fall. The number of FTE students funded depends on the amount of enrollment funding provided and statutory per–student funding rates for credit, noncredit, and “enhanced noncredit” (also known as career development and college preparation) courses. (The latter category consists of noncredit basic skills, English as a second language, and career technical education courses.) The state adjusts these funding rates for any cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) included in the annual budget act.

Proposes No Resident Enrollment Targets for UC, CSU, or Hastings. In his budget summary, the Governor asserts that funding enrollment growth “does not encourage postsecondary institutions to focus on critical outcomes—affordability, timely completion rates, and quality programs—nor does it encourage institutions to better integrate their efforts to increase productivity of the system as a whole.”

Proposes 2 Percent Enrollment Growth at CCC. As an exception to his views on enrollment funding, the Governor proposes $107 million for 2 percent enrollment growth (an additional 23,000 FTE students) at CCC. The Governor does not elaborate on why he proposes to fund enrollment at the community colleges despite his misgivings about enrollment–based budgeting for higher education. (As discussed in the box, the Governor does not designate the $107 million specifically for enrollment growth in the budget. He also removes language guiding the use of the growth dollars and removes funding for “enrollment restoration.”)

State Budget Traditionally Keeps Enrollment Funds Separate From Other Funding. The state budget typically specifies an amount for enrollment growth within the California Community Colleges (CCC) appropriation and contains language requiring these funds be used only for enrollment growth. In recent years, the budget language has required CCC to give highest priority to expanding enrollment in courses related to transfer, basic skills, and workforce training and refrain from funding certain other types of courses (such as concurrent enrollment courses in dance and personal development). In 2014, the state adopted legislation codifying these enrollment priorities.

State Budget Traditionally Includes Enrollment Restoration Funds. For many years, state policy has been to give community college districts that experience a decline in enrollment a period during which they can earn back or restore that enrollment. According to state law, districts with declining enrollment in one year lose the associated funding the following year, but the system retains it and the districts have three years to earn the funding back. In effect, this creates a set aside these districts can tap if they resume growing. CCC can use these funds for one–time purposes until they are needed by the respective colleges. After three years, the state adjusts CCC apportionments to reflect whatever portion of the restoration funding districts have earned back. Any unearned funds at that time effectively are redirected to other Proposition 98 priorities.

Governor’s Budget Departs From Traditional Budgeting Practices. The administration makes three changes to CCC enrollment budgeting, describing each as a technical adjustment. Specifically, the Governor’s budget (1) does not specify certain funds for CCC enrollment growth, (2) does not include provisional language restricting their use, and (3) removes $47 million in restoration funding from CCC apportionments. The administration indicates that it believes enrollment restoration is unnecessary because any enrollment growth a district experiences following a temporary decline in enrollment can be earned back using regular enrollment growth funding.

Not Linking Funding Directly to Enrollment Growth Reduces Transparency. Though we are not concerned about the removal of language prioritizing the types of courses to be supported with enrollment growth monies, as this language is now codified, we are concerned about no longer identifying the amount of enrollment growth funding in the budget and no longer requiring that the amount be used only for this purpose. These changes would allow CCC, instead of the Legislature, to direct the use of any funds not needed for enrollment growth as well as increase the difficulty the Legislature and the public would have in tracking enrollment growth. We recommend the Legislature reject these change and specify the amount and purpose of enrollment growth funding in the budget.

Enrollment Restoration Policy Merits Separate Conversation. We also are concerned that the Governor is describing his decision to remove restoration funds as a technical adjustment. This action conflicts with relatively longstanding state policy. Though the set aside seems less valuable when the state is funding notable enrollment growth, removing the set aside could have unintended local effects. Given the potentially varied local effects, we believe the Legislature would want to have more deliberation on this policy before deleting the associated funds, particularly as it does not reflect a purely technical adjustment and would require a statutory change.

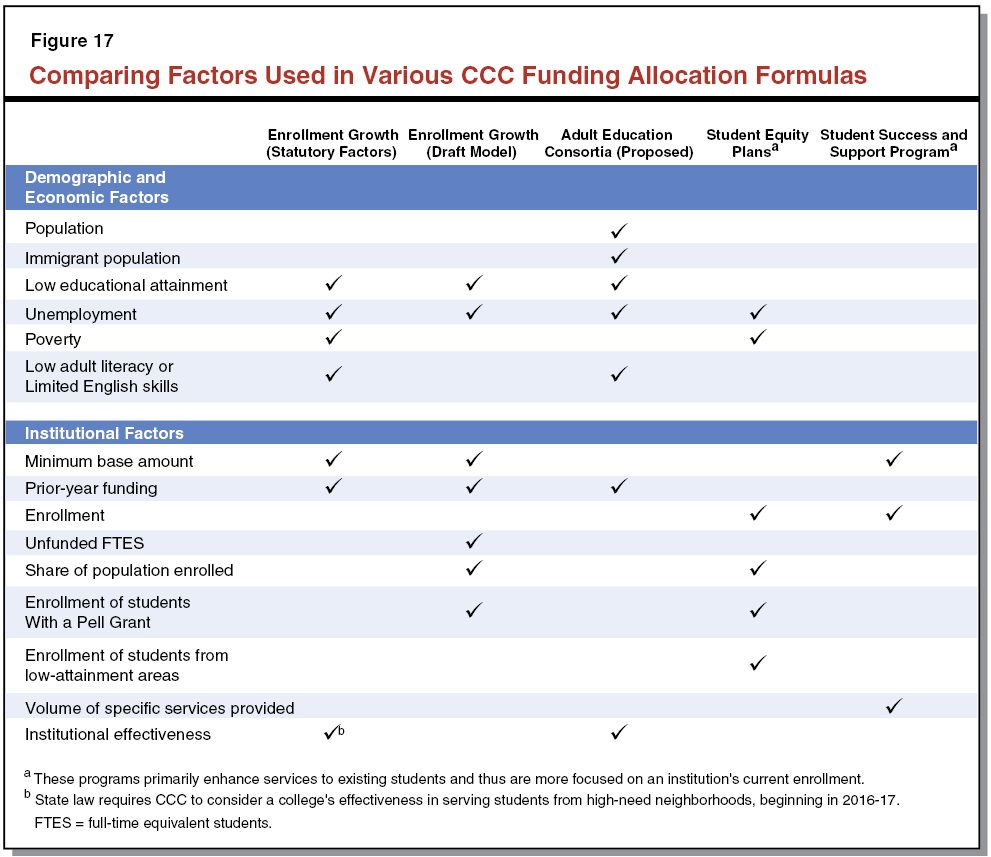

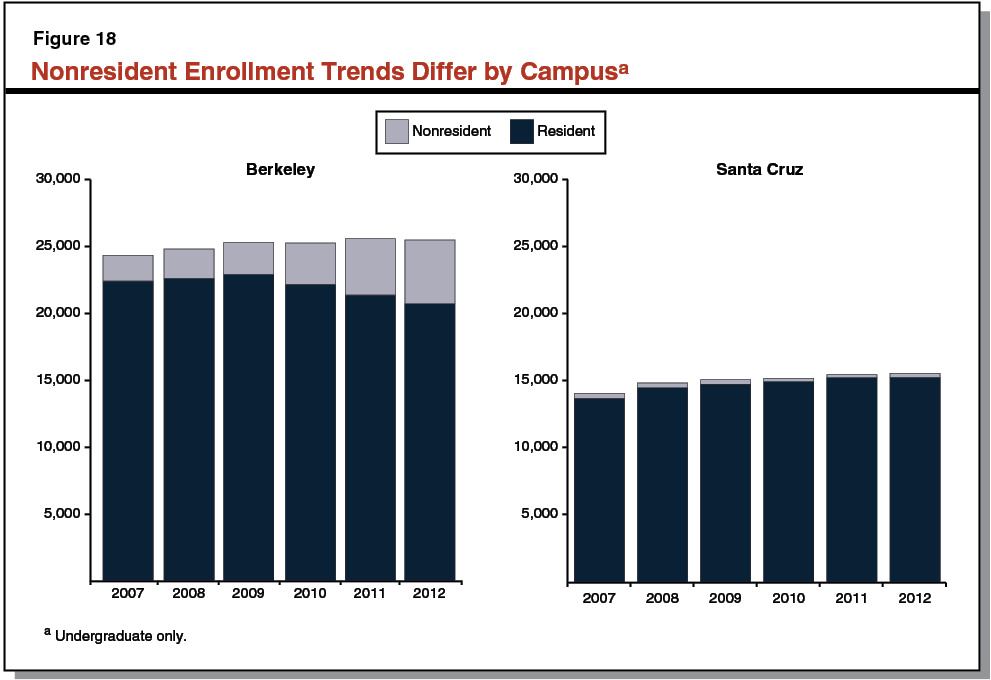

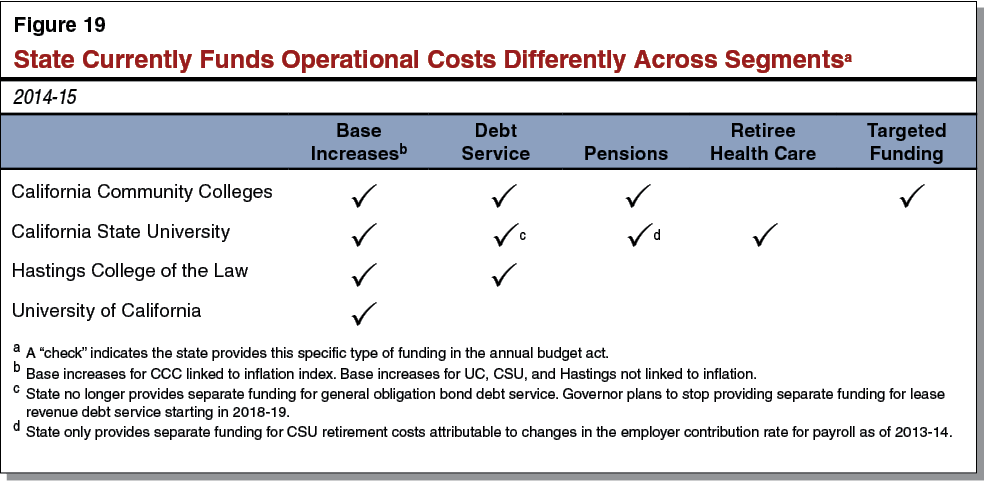

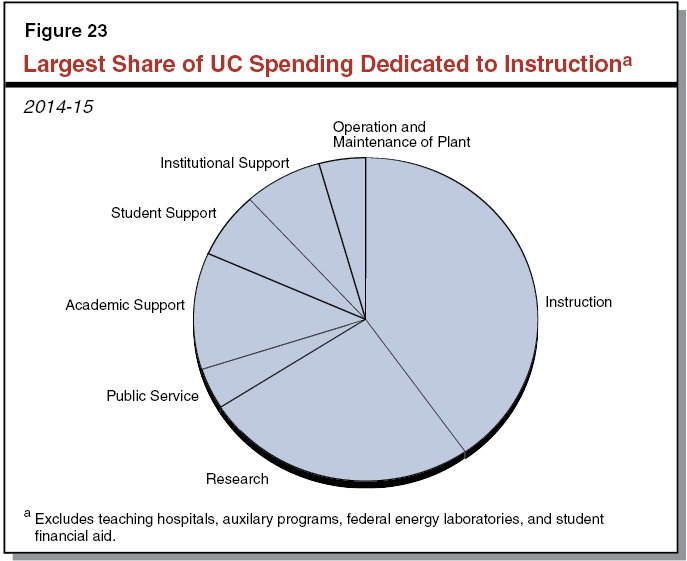

Enrollment Funding a Key State Policy and Budget Tool. Enrollment funding allows the Legislature to set clear expectations about higher education access. In addition, enrollment budgeting aligns state funding with higher education costs. Though the Governor makes an accurate observation that enrollment funding does not provide incentives for the segments to improve outcomes, the state’s interest in improving outcomes could be addressed by monitoring performance. That is, the state need not discard enrollment funding to focus on performance. Rather than choosing one or the other, a balanced budget approach could address the twin goals of access and success (similar to how the Governor treats community colleges).