On January 9, 2015, the Governor presented his 2015–16 budget proposal to the Legislature. As shown in Figure 1, the budget package proposes spending $158.8 billion, an increase of 1 percent over revised levels for 2014–15. While the figure shows 1.4 percent General Fund spending growth, that number understates growth in program spending because of a variety of one–time factors. This total consists of $113.3 billion from the General Fund and $45.5 billion from special funds. In addition, the administration proposes to spend $5.9 billion from bond funds and $100.4 billion from federal funds. (For a summary of estimated and proposed state spending by major program area, see the appendix.)

Figure 1

Governor’s Budget Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Fund Type

|

2013–14

Revised

|

2014–15

Revised

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

General Funda

|

$99,838

|

$111,720

|

$113,298

|

|

$1,578

|

1.4%

|

|

Special funds

|

38,311

|

45,559

|

45,520

|

|

–38

|

–0.1

|

|

Budget Totals

|

$138,149

|

$157,278

|

$158,818

|

|

$1,540

|

1.0%

|

|

Selected bond funds

|

$4,494

|

$5,252

|

$5,885

|

|

$633

|

12.1%

|

|

Federal funds

|

72,583

|

96,505

|

100,376

|

|

3,871

|

4.0

|

The 2015–16 Governor’s Budget marks the first budget proposal since Proposition 2—the budget reserve and debt payment measure—was approved by voters in November 2014. Proposition 2 is highly complex and significantly alters how the state saves money in its budget reserves and pays down existing debts.

The General Fund receives most state taxes and is the state’s main operating account. The Legislature must balance resources and expenditures from the fund each year. Figure 2 displays the administration’s estimate of the condition of the General Fund.

Figure 2

The Administration’s General Fund Condition Statement

Includes Education Protection Account (In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

Revised

|

2014–15

Revised

|

2015–16

Revised

|

|

Prior–year fund balance

|

$2,264

|

$5,100

|

$1,423

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

102,675

|

108,042

|

113,380

|

|

Expenditures

|

99,838

|

111,720

|

113,298

|

|

Difference between revenues and expenditures

|

$2,837

|

–$3,678

|

$82

|

|

Ending fund balance

|

$5,100

|

$1,423

|

$1,505

|

|

Encumbrances

|

971

|

971

|

971

|

|

SFEU balance

|

4,130

|

452

|

534

|

|

Reserves

|

|

|

|

|

SFEU balance

|

$4,130

|

$452

|

$534

|

|

Pre–Proposition 2 BSA balance

|

—

|

1,606

|

1,606

|

|

Proposition 2 BSA balance

|

—

|

—

|

1,220

|

|

Total Reserves

|

$4,130

|

$2,058

|

$3,361

|

Despite Large Revisions, 2014–15 Ends With Nearly Unchanged SFEU Balance. In the Governor’s budget proposal, the administration routinely updates estimates of revenues and spending for the last two enacted budgets, as well as the estimate of the entering fund balance for the prior year (in this case 2013–14). Over 2013–14 and 2014–15 combined, the administration projects higher revenues ($3 billion) and higher net spending ($2.9 billion) compared with figures assumed in the June 2014 budget package. (For 2014–15, overall General Fund spending for education rises $2.5 billion above last June’s assumptions largely due to higher Proposition 98 requirements, and health and human services spending rises by a net amount of over $800 million.) In addition, the Governor’s budget reflects a $165 million downward adjustment to the entering fund balance for 2013–14. These revisions result in an ending balance in the 2014–15 Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU)—the state’s traditional budget reserve—which is just $3 million higher than assumed in the June 2014 budget package.

Budget Proposes Total Reserves of $3.4 Billion for End of 2015–16. Under the administration’s revenue projections and spending proposals, the General Fund would end 2015–16 with $3.4 billion in reserves. This total is the combination of $1.6 billion deposited in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) before Proposition 2, a $1.2 billion projected deposit in the BSA for 2015–16, and a $534 million year–end reserve in the SFEU. As we discussed in our November 2014 publication, The 2015–16 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, there is a strong argument that the Legislature could appropriate pre–Proposition 2 BSA balances with a simple majority vote, whereas the Governor would have to declare a budget emergency before the Legislature could access BSA funds deposited after passage of Proposition 2.

Figure 3 presents the major features of the Governor’s proposal.

Figure 3

Major Features of the Governor’s Budget Proposal

|

Budget Reserves

|

- Ends 2015–16 with $3.4 billion in total reserves.

|

- Includes $2.8 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account and $534 million in the state’s traditional budget reserve.

|

|

Paying Down State Debts

|

- Pays down $1.2 billion in non–retirement budget debts, to meet Proposition 2 requirements.

|

- Includes about $1 billion in special fund loans and $256 million in Proposition 98 “settle up.”

|

- Eliminates all remaining school and community college deferrals ($992 million).

|

- Pays down $1.5 billion of mandate backlog for schools and community colleges.

|

- Provides final $273 million payment for school facility repair program.

|

- Provides $533 million to cities and counties for mandates under 2014–15 budget “trigger.”

|

- Plans to discuss $72 billion unfunded liability for retiree health benefits with state employee groups.

|

|

Education

|

- Provides additional $4 billion for K–12 Local Control Funding Formula.

|

- Provides additional $876 million for workforce education and training.

|

- Includes funding for adult education consortia, career technical education, apprenticeships, and noncredit instruction.

|

- Increases community college funding by $524 million for enrollment growth, COLA, student support, and other campus priorities.

|

- Increases base funding by $119 million each for the California State University and the University of California.

|

- Augments Cal Grant funding by $69 million in 2014–15 and an additional $129 million in 2015–16 for increased participation.

|

|

Health and Human Services

|

- Assumes Medi–Cal caseload of 12.2 million.

|

- Restructures managed care organization tax to comply with federal law and to raise additional revenues in order to restore IHSS hours eliminated as a result of the 7 percent reduction.

|

- Reserves $300 million for costs associated with new Hepatitis C medication.

|

- Funds previously approved CalWORKs grant increase with redirected realignment revenues and $73 million from the General Fund.

|

|

Resources/Environment

|

- Appropriates remaining funds from Proposition 1E (2006) flood prevention bond ($1.1 billion).

|

- Allocates $532.5 million of the Proposition 1 water bond passed by the voters in 2014.

|

- Assumes $1 billion of cap–and–trade auction revenues.

|

- Spends $115 million ($93.5 million General Fund) for drought response.

|

|

Infrastructure

|

- Addresses some deferred maintenance issues in specified departments using about $500 million from the General Fund.

|

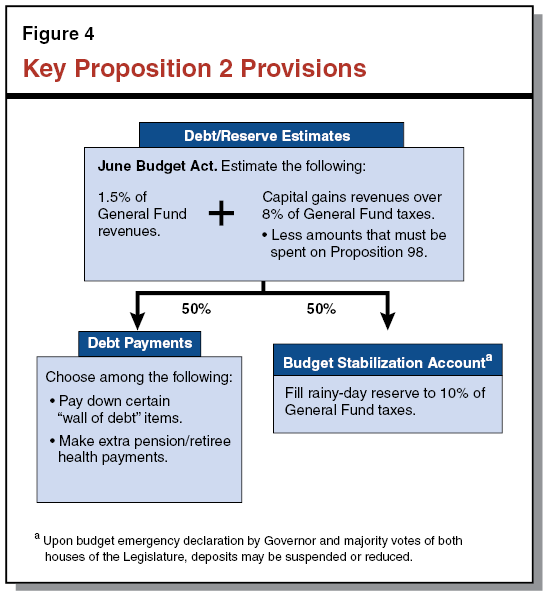

Deposits $1.2 Billion in the BSA. Figure 4 displays the Proposition 2 rules and calculations relevant for the 2015–16 budget process. (Proposition 2 also created a reserve for school and community college funding under Proposition 98, but a deposit into that reserve seems unlikely in the next few years.) As shown in the figure, Proposition 2 annually captures an amount equal to 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues plus capital gains taxes that exceed a long–term historical average. Under the administration’s revenue and Proposition 98 estimates, Proposition 2 captures a total of $2.4 billion. Proposition 2 requires that this total be split between debt payments and the BSA. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget makes a $1.2 billion deposit in the BSA in 2015–16.

Pays Down $1.2 Billion in Debts Under Proposition 2. Proposition 2 requires that the remaining $1.2 billion be used to pay down existing state debts. The administration proposes to pay down $965 million in special fund loans and $256 million in prior–year Proposition 98 costs known as “settle up.” These actions reduce the outstanding amount of special fund loans and Proposition 98 settle up to $2.1 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively. The administration’s multiyear forecast proposes to dedicate Proposition 2 debt payments exclusively for these two purposes through 2018–19, thereby providing no Proposition 2 funding to address the state’s large retirement liabilities—those liabilities resulting from unfunded pension and retiree health benefits—during that period.

Budget Suggests Collective Bargaining on Retiree Health Liabilities. The state prefunds pension benefits for state employees by investing contributions during those employees’ working years and using these resources to pay monthly pension payments in retirement. Unlike pension benefits, the state does not prefund health and dental benefits for its retired workers. Rather, the state pays for the cost of retiree health benefits when those workers retire, a much more expensive system known as “pay–as–you–go.” As of the end of 2013–14, the state recorded a $71.8 billion unfunded liability for retiree health benefits earned to date by current and past state and California State University (CSU) employees.

In his budget proposal, the Governor suggests bargaining with public employee unions in the coming years to begin addressing this problem. The 2015–16 Governor’s Budget Summary calls for active and future state workers to split the cost of prefunding benefits earned in the future—similar to the standard adopted by the Legislature for pensions in 2012. The Governor’s budget plan—including the administration’s multiyear budget forecast—provides no funding for any of these efforts through 2018–19 (the multiyear forecast’s final year).

Significant New Funding for Education. The bulk of new spending under the Governor’s budget is for education. The largest single education augmentation is $4 billion to continue implementing the Local Control Funding Formula, a new school funding formula adopted in 2013. The Governor also has major new proposals in the area of workforce education and training, including $500 million for adult education regional consortia. The Governor has a relatively generous budget proposal for the California Community Colleges (CCC), including funding for 2 percent enrollment growth, a 1.6 percent cost–of–living adjustment, and $200 million for student support—all on top of a $125 million unallocated base increase and various other increases related to the Governor’s workforce initiative. The Governor also would retire all payment deferrals for community colleges and pay off most of the community college mandates backlog. (The Governor also retires all school deferrals and a portion of the school mandates backlog.) The Governor’s main higher education proposal is 4 percent ($119 million) base increases for the University of California (UC) and CSU.

MCO Tax and Restoring IHSS Service Hours. The state imposes a tax on managed care organizations (MCOs) to draw down matching federal Medicaid funds. The federal government indicated that taxes structured like California’s MCO tax do not comply with federal regulations. The administration proposes to modify the MCO tax to achieve compliance with federal law. As part of that process, the administration proposes to raise additional revenues to provide the nonfederal share of Medicaid funding necessary to restore In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) authorized service hours that were eliminated as a result of the current 7 percent reduction in these hours enacted in the 2013–14 budget. This restoration of hours by seeking a non–General Fund funding source is consistent with an IHSS litigation settlement agreement adopted by the Legislature.

Includes Placeholder for Cost of New Hepatitis C Medication. The federal Food and Drug Administration recently approved new breakthrough drugs to treat Hepatitis C. These drugs—at $85,000 per treatment regimen—will increase costs across a few state departments. Specifically, inmates in state prisons, patients in state hospitals, and individuals enrolled in Medi–Cal and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program will receive these medications. While costs for the new treatments are uncertain, the administration reserves a total of $600 million across 2014–15 and 2015–16 combined, split between the state General Fund and federal funds.

Proposes Spending $533 Million From Proposition 1 Water Bond. The Governor proposes spending $533 million from the $7.5 billion water bond approved by voters in November 2014. In addition, the administration proposes appropriating the remaining $1.1 billion from the Proposition 1E flood prevention bond approved by voters in 2006.

Governor’s Priorities Generally Prudent Ones. In the coming weeks, we will examine the administration’s proposals and budget estimates in more detail and report to the Legislature on our findings. The Governor’s budgeting philosophy continues to be a prudent one for the most part. In the near term, the Governor’s reluctance to propose significant new program commitments outside of Proposition 98 could help avoid a return to the boom and bust budgeting of the past. Moreover, his proposal to address the state’s retiree health liabilities over the next few decades would, if fully funded, address the last of state government’s large unaddressed liabilities. Over the long run, eliminating these liabilities will significantly lower state costs, affording future generations more flexibility in public budgeting.

Budget Vulnerability Remains. Our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook showed how a downturn could throw the budget out of balance, although no recession appears imminent. While the budget is on track to enter the next downturn healthier than it was a decade ago, the state’s finances remain vulnerable to the sudden tax revenue declines that will inevitably return with little warning. The array of complex budget formulas—especially those of Propositions 98 and 2—complicate budget planning and could exacerbate this vulnerability in some scenarios. History tells us that strong revenue periods like now are ones that require cautious budgetary decision making.

Administration Revenue Numbers Higher. The Governor’s plan reflects higher revenue projections compared to the administration’s estimates in the June 2014 state budget plan. For 2014–15, the administration raised its General Fund revenue estimates by about $2.5 billion, with higher personal and corporate income taxes offsetting a somewhat weaker sales tax projection. In fact, over the three–year “budget window” (2013–14 through 2015–16 combined), the Governor’s Budget projection for the state’s “big three” revenues (personal income, sales, and corporation taxes) exceeds our office’s November 2014 estimate by $1.3 billion, mostly due to the administration’s $900 million higher projection for sales and personal income taxes in 2015–16. The big three taxes make up over 95 percent of General Fund revenue.

2014–15 Revenues Trending Even Higher. Midway through the 2014–15 fiscal year, the state’s big three taxes already are running $3.5 billion ahead of the administration’s June 2014 projections. For the entire fiscal year, the administration raised its revenue estimates by about $2.5 billion. Therefore, there is a strong possibility that revenues for 2014–15 will be significantly above the administration’s new projections. Barring a sustained stock market drop, an additional 2014–15 revenue gain of $1 billion to $2 billion above the administration’s new estimate seems likely. Even bigger gains of a few billion dollars more are possible. The exact amount of the likely additional 2014–15 revenue will depend in large part on the following trends:

- 2014 personal income tax (PIT) estimated payments received from high–income taxpayers over the next week (mostly just after the January 15 due date) as well as April and June 2015 income tax payments and refunds.

- The extent to which lower oil prices and the improving economy boost taxable retail sales and other economic activity in 2015.

- How the state’s complex accrual policies shift 2014–15 revenue collections to other fiscal years.

Strong Revenues May Not Last Long. As we described in our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook, additional 2014–15 General Fund revenues likely will almost all go to schools and community colleges, thereby not benefiting the state’s financial bottom line. Further, this could increase ongoing school costs by a few billion dollars per year. Yet, state revenue collections now may be peaking, due largely to surging stock prices in 2014. History cautions that this level of peak revenue will not persist for long. Weak revenue growth in an upcoming year could make it difficult to sustain state spending level, with the higher level of school spending generated in 2014–15. As such, the likely higher revenues in the current fiscal year and the resulting increase in ongoing school spending present a potential challenge for the state budget.

Proposition 2 Drives Reserve Levels. Proposition 2 was approved by voters in November and affects the budget for the first time in 2015–16. As we described in our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook, Proposition 2 deposits funds to the state’s rainy–day fund based on a series of formulas that interact with each other in complex and sometimes counterintuitive ways. (We will analyze the administration’s calculations more in the coming weeks.) Under the administration’s calculations, total budget reserves grow to $3.4 billion, including a $1.2 billion rainy day fund deposit under Proposition 2. This represents progress in building the state’s budgetary reserves.

Are Larger Reserves Needed? With the economy now years past the last recession and with the possibility that volatile capital gains could fall, a $3.4 billion reserve provides little protection for budgetary shortfalls that can reemerge with little warning. The administration also correctly identifies several major budget risks due to federal or court actions in health and human services programs. While it would be difficult to build larger reserves under the administration’s current budget estimates, more reserves now would be desirable. To the extent that 2015–16 revenue and capital gains rise above the administration’s projections, Proposition 2 likely would require added reserve deposits.

Governor Prioritizes Wall of Debt. The Governor coined the term “wall of debt” a few years ago to cover billions of dollars of non–retirement related budget liabilities such as deferred payments to schools and loans from state accounts known as special funds. The state has made significant progress in addressing the wall of debt, including this budget’s anticipated elimination of all remaining school payment deferrals. In his budget plan and multiyear budget projections (through 2018–19), the Governor proposes using the portion of Proposition 2 funds dedicated to debt payment exclusively to address the state’s non–retirement liabilities, including the remaining special fund loans and prior–year Proposition 98 settle–up obligations.

Governor’s Ideas About Retiree Health. The Governor and Legislature made difficult decisions in recent years to reduce future state pension costs and fully fund the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). In his budget proposals, the Governor mentions a number of ideas about how to address the state’s largest remaining set of unaddressed retirement liabilities, those related to state government retiree health benefits (now valued at $72 billion, including CSU). We agree that it is time to start difficult discussions with state employee groups and the Legislature on these matters.

Money Needed. The Governor’s budget plan articulates a goal of eliminating unfunded state retiree health liabilities within about 30 years. The indispensable component of such an effort is money. Money is needed from various public and employee sources to start paying normal costs (on the retiree benefits earned with each new year of employee service) and to ensure that existing unfunded liabilities are paid off within 30 years or whatever alternative period of time is chosen by state leaders. To meet the Governor’s goal, additional payments from all funding sources may approach $2 billion per year in current dollars (growing over time). The administration does not recognize the costs of the ambitious retiree health proposal in its multiyear budget projection (which ends in 2018–19). The administration could have suggested a tentative earmark of a portion of Proposition 2 debt reduction funding during the 2020s to pay for some or all of its plan. The voters approved the dedicated funding for exactly this kind of effort.

Plan Needed for Proposition 2 Debt Payments. The administration does not provide a long–term plan for the 15 years of required annual Proposition 2 debt payments. We advise the Legislature to choose its own priorities for Proposition 2 debt payments in 2015–16 and also consider a short–term and longer–term plan for these debt payments during this legislative session. As we advised in November, we think the Legislature would benefit from soliciting proposals from the administration, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), CalSTRS, UC, and others on how the Proposition 2 moneys could best be used in the future. Addressing the budgetary obligations prioritized by the Governor involves certain benefits, while there would be other benefits from addressing retiree health liabilities, paying off the remaining of the old retirement system for judges, or paying down CalPERS, CalSTRS, or UC liabilities faster. By committing soon to future Proposition 2 debt payments on the retiree health liability, for example, the state potentially could reduce its unfunded liabilities in the near term and generate investment returns and federal dollars.

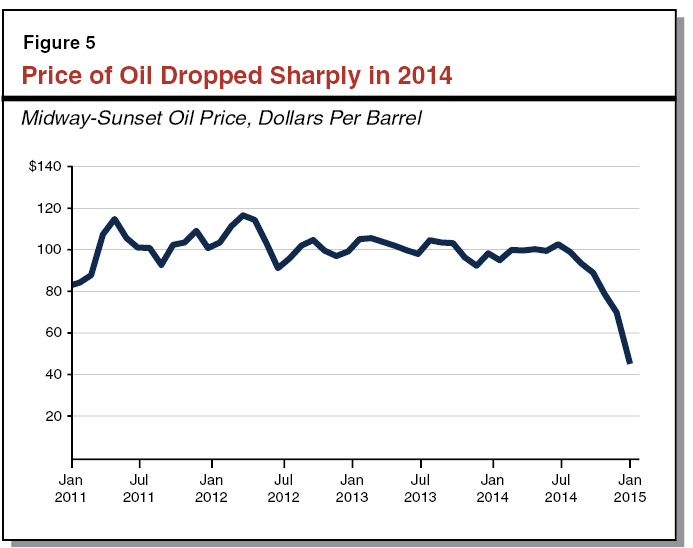

Forecast Does Not Reflect Recent Changes. The administration’s new economic forecast projects that real gross domestic product (GDP) for the U.S., a key measure of overall economic activity, rose 2.2 percent in 2014 and will grow by 2.6 percent in 2015 and 2.8 percent in 2016. (A comparison of the administration’s economic projections with other recent forecasts will be posted on our California Economy and Taxes blog.) This is a reasonable forecast, but by necessity, the administration had to complete most of its forecasting work before the sharp fall in worldwide oil prices of recent weeks. Like the prices in California’s primary oil field displayed in Figure 5, worldwide oil prices have fallen sharply in recent months from over $100 per barrel to about $50 per barrel, with much of this drop occurring during December. By contrast, the administration’s forecast assumes roughly $80 per barrel oil prices in the final quarter of 2014, as well as all of 2015. At the same time that oil price declines are helping the economy in various ways, other key economic data have been strong. For example, the preliminary estimate of California’s November 2014 job growth (90,100) was the second–highest seasonally adjusted monthly increase since 1990. Based on all these trends, we currently assume that real GDP will grow slightly faster than the administration estimates in 2014 and 2015.

Low Oil Prices Help Economy in Near Term. Oil accounts for more than one third of all U.S. energy use, mostly as vehicle fuel. Some recent studies estimate that lower oil prices should cause overall U.S. economic output to rise by 0.5 percent to 1 percent on a one–time basis, accounting for both the gains to oil users and the losses to oil producers. The positive effect of a price decline on California would most likely be in the same range, if not slightly above the national average. Although California is a net consumer of oil, some areas of the state (such as Kern County) are net producers. Cheaper oil can hurt these local economies.

Gasoline Prices Affect Transportation Funding. As oil prices have dropped, so have California’s gasoline prices. Last week, the average retail price of gasoline in California was $2.72 per gallon—down a dollar since the first week of October. When prices drop, consumers buy more gasoline. California’s transportation funding relies heavily upon gasoline excise taxes. The state’s gasoline excise tax has two parts, and low gasoline prices affect each part differently. The first one—an 18–cent “base” excise tax—depends only on the amount of gasoline sold. Low prices lead to higher gasoline consumption, which leads to higher revenue from the base excise tax. The second excise tax on gasoline—resulting from California’s fuel tax swap—has a rate that varies from year to year. In the short run, revenue from this tax depends only on the amount of gasoline sold, so low gasoline prices lead to higher revenue. However, the year–to–year rate changes are based on a formula that incorporates past gasoline prices. That means that low gasoline prices this year will lead to a lower excise tax rate—and therefore lower revenue—in future years.

California’s Economy Is Globally Connected. International trade is important to California’s economy. The state’s largest trading partners include Japan and many European nations. Over the past several months, the near–term economic outlook for many of these countries has considerably worsened. China’s economy also is a concern, given inflated asset “bubbles” there and other economic imbalances. These issues may affect California in various ways over the coming year, both positive and negative. On the one hand, California households may benefit from lower–cost imports due to the recent strength of the U.S. dollar in global currency markets. Weakness in economies elsewhere in the world has caused the U.S. dollar to appreciate significantly over the last few months. On the other hand, sagging economic growth in Europe and Japan could be accompanied by falling incomes and rising unemployment there. These factors, along with higher prices resulting in part from the stronger U.S. dollar, could reduce consumer demand for California exports.

The administration now estimates that the big three General Fund taxes will total $105.2 billion in 2014–15 and $110.9 billion in 2015–16, a $5.6 billion year–over–year increase (including technical adjustments shown in Figure 6).

Figure 6

Comparing New Administration Revenue Projections With Other Recent Projections

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (In Millions)

|

|

June 2014

Budget Packagea

|

Nov. 2014

LAO (Main Scenario)

|

Jan. 2015

Governor’s Budget

|

|

2013–14

|

|

|

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$66,522

|

$66,667

|

$66,560

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

22,759

|

22,251

|

22,263

|

|

Corporation tax

|

8,107

|

8,519

|

8,858

|

|

Subtotals, “Big Three” taxes

|

($97,388)

|

($97,437)

|

($97,681)

|

|

Insurance Tax

|

$2,287

|

$2,371

|

$2,363

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,163

|

2,093

|

2,253

|

|

Transfers (net)

|

347

|

376

|

376

|

|

Totals

|

$102,185

|

$102,277

|

$102,675

|

|

2014–15

|

|

|

|

|

Personal income taxb

|

$70,238

|

$72,201

|

$72,039

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

23,823

|

23,420

|

23,438

|

|

Corporation taxb

|

8,910

|

9,482

|

9,748

|

|

Subtotals, Big Three taxes

|

($102,971)

|

($105,103)

|

($105,225)

|

|

Insurance Tax

|

$2,382

|

$2,435

|

$2,490

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,400

|

2,050

|

2,405

|

|

Transfer to BSA

|

–1,606

|

–1,606

|

–1,606

|

|

Other transfers (net)b

|

–658

|

–540

|

–472

|

|

Totals

|

$105,488

|

$107,442

|

$108,042

|

|

2015–16

|

|

|

|

|

Personal income taxb

|

$74,444

|

$74,932

|

$75,403

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

25,686

|

24,653

|

25,166

|

|

Corporation taxb

|

9,644

|

10,375

|

10,293

|

|

Subtotals, Big Three taxes

|

($109,774)

|

($109,960)

|

($110,862)

|

|

Insurance Tax

|

$2,499

|

$2,512

|

$2,531

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,076

|

2,018

|

2,050

|

|

Transfer to BSA

|

–937

|

–1,974

|

–1,220

|

|

Other transfers (net)b

|

–1,084

|

–1,118

|

–842

|

|

Totals

|

$112,328

|

$111,397

|

$113,380

|

Billions of Dollars More Revenues. As shown in Figure 6, the administration has raised its revenue projections since June by billions of dollars, spread across the three years of the budget window (2013–14 through 2015–16). In general, the administration has raised its personal and corporate income tax projections noticeably: PIT by $1.8 billion in 2014–15 and nearly $1 billion in 2015–16 and corporation tax (CT) by $750 million in 2013–14, over $800 million in 2014–15, and $650 million in 2015–16. Offsetting these increases, the administration has lowered its sales and use tax projections by about $500 million for 2013–14, $400 million in 2014–15, and over $500 million in 2015–16. For the big three taxes combined, which make up over 95 percent of General Fund revenues, the new administration projections increase the June 2014 budget projections by $300 million in 2013–14, $2.25 billion in 2014–15, and $1.1 billion in 2015–16.

Robust Income Tax Collections. The administration’s new projections reflect recent months’ strong personal and corporate income tax collections by the state, including gains in PIT withholding (generally related to employees’ wage income) and low levels of CT refunds. After the administration completed its projections, the state experienced a surge in estimated PIT payments (generally by higher–income taxpayers related to capital gains and business income) in December 2014. Significant periods of income tax collections will occur over the next week, in mid–April, and in mid–June, which, collectively, will be the key to determining the eventual level of 2014–15 state revenues. The big three tax collections for 2014–15 to date, as well as strong economic and stock trends in recent months, lead us to conclude that additional 2014–15 General Fund tax revenues of $1 billion to $2 billion above the administration’s new projections are likely, barring a sustained stock market drop during the rest of this fiscal year. Even bigger gains of a few billion dollars more are possible in 2014–15. Future trends in stock prices and business income will affect whether 2015–16 income tax collections climb further, stagnate, or, in the worst case, decline compared to this year’s robust levels. Our office expects to release updated revenue projections in May.

Loan repayments to special funds are booked on the “revenue side” of the budget as a transfer out of the General Fund (therefore, as a reduction in overall revenues). In 2015–16, the Governor proposes repaying around $1 billion of loans that special funds were required to make to the General Fund to help address multibillion–dollar annual deficits in the last decade. Figure 7 summarizes these proposed repayments. The funds listed are among the hundreds of state accounts other than the General Fund. They fund public services supported by taxes or fees collected for specific purposes.

Figure 7

Special Fund Loan Repayments Proposed in 2015–16a

(In Millions)

|

Fund Name

|

Amount

|

|

Unemployment Compensation Disability Fund

|

$303.5

|

|

Motor Vehicle Account

|

300.0

|

|

State Courts Facility Construction Fund

|

220.0

|

|

Electronic Waste Recovery & Recycling Account

|

27.0

|

|

Vehicle Inspection Repair Fund

|

25.0

|

|

Hazardous Waste Control Account

|

13.0

|

|

California Health Data and Planning Fund

|

12.0

|

|

Off–Highway Vehicle Trust Fund

|

11.0

|

|

Contingent Fund of the Medical Board of California

|

10.0

|

|

Enhanced Fleet Modernization Subaccount

|

10.0

|

|

Board of Registered Nursing Fund, Professions and Vocations Fund

|

8.3

|

|

Dealers’ Record of Sale Special Account

|

6.5

|

|

Accountancy Fund

|

6.0

|

|

Private Security Services Fund

|

4.0

|

|

Debt and Investment Advisory Commission Fund

|

2.0

|

|

Debt Limit Allocation Committee Fund

|

2.0

|

|

Physical Therapy Fund

|

1.5

|

|

Behavioral Science Fund

|

1.2

|

|

Illegal Drug Lab Cleanup Account

|

1.0

|

|

Speech–Language Pathology and Audiology Fund

|

0.5

|

|

Driving–Under–The–Influence Program Licensing Trust Fund

|

0.4

|

|

Total

|

$964.8

|

Proposition 2 Debt Payments. The Governor’s clear priority for use of dedicated Proposition 2 debt reduction payments is the repayment of special fund loans. The repayments that he identifies equal 79 percent of his proposed Proposition 2 debt payments in 2015–16. The state could pay off more or less special fund loans now than the Governor proposes, and it could prioritize other eligible Proposition 2 debt reductions, including paying off retiree health liabilities.

Oversight. When the administration proposes repaying a special fund loan, it is a good opportunity for the Legislature to exercise its oversight role concerning that special fund. Are the fund’s fee or tax sources too high or too low? Should the services provided by the fund change? Are affected members of the public satisfied with services provided by the fund? Is the special fund still needed?

Funding for Schools and Colleges Largely Driven by Formulas. State budgeting for K–12 education, the California Community Colleges (CCC), subsidized preschool, and various other state education programs is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by voters in 1988. The measure establishes a minimum funding requirement, commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. Both state General Fund and local property tax revenue apply toward meeting the minimum guarantee. The Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is determined by one of three tests set forth in the State Constitution. These tests are based on several inputs, including changes in K–12 enrollment, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue.

Significant Proposed Increase in Proposition 98 Funding. The Governor’s budget package includes substantial new Proposition 98 spending—a total of $7.8 billion. From an accounting perspective, $4.9 billion of this amount is related to 2015–16, $2.3 billion to 2014–15, $371 million to 2013–14, and $256 million to 2009–10. Under the Governor’s budget, K–12 Proposition 98 funding rises from $8,931 per student in 2014–15 to $9,571 per student in 2015–16—an increase of $640 (7.2 percent). CCC Proposition 98 funding increases from $6,066 per full–time equivalent (FTE) student in 2014–15 to $6,574 per FTE student in 2015–16—an increase of $508 (8.4 percent).

2013–14 Minimum Guarantee Up $371 Million. As shown in Figure 8, the administration’s revised estimate of the 2013–14 minimum guarantee is $58.7 billion, a $371 million increase from the June 2014 estimate. Of this increase, about $200 million is due to General Fund revenue being higher than previously assumed and about $100 million is due to a 0.17 percent increase in K–12 enrollment. Revised estimates of state population and small changes to the minimum guarantee in earlier years account for the remaining difference. Estimated state costs for 2013–14 are up $70 million due to the increase in K–12 enrollment. After accounting for higher enrollment costs, state spending is $301 million below the revised estimate of the minimum guarantee.

Figure 8

Increase in 2013–14 and 2014–15 Minimum Guarantees

(In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

|

2014–15

|

|

June 2014

Estimate

|

January 2015

Estimate

|

Change

|

June 2014

Estimate

|

January 2015

Estimate

|

Change

|

|

Minimum Guarantee

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$42,731

|

$42,824

|

$94

|

|

$44,462

|

$46,648

|

$2,186

|

|

Local property tax

|

15,572

|

15,849

|

277

|

|

16,397

|

16,505

|

108

|

|

Totals

|

$58,302

|

$58,673

|

$371

|

|

$60,859

|

$63,153

|

$2,294

|

2014–15 Minimum Guarantee Up $2.3 Billion. As shown in Figure 8, the administration’s revised estimate of the 2014–15 minimum guarantee is $63.2 billion, a $2.3 billion increase from the June 2014 estimate. This increase is almost entirely attributable to General Fund revenue being higher than previously assumed. Test 1 remains operative in 2014–15, with General Fund revenue increases yielding a near dollar–for–dollar effect on the guarantee. The Governor revises estimated state costs for 2014–15 upward by $279 million due to higher–than–expected K–12 enrollment. These changes result in state spending that is $2 billion below the revised estimate of the minimum guarantee. (The increase in revenue mentioned above results in the state’s estimated maintenance factor payment increasing by $1.2 billion—for a total estimated payment in 2014–15 of $3.8 billion.)

2015–16 Minimum Guarantee Up $4.9 Billion Over 2014–15 Budget Act Level. As shown in Figure 9, the Governor’s budget includes $65.7 billion in total Proposition 98 funding in 2015–16. This is $2.6 billion above the revised 2014–15 guarantee and $4.9 billion above the 2014–15 Budget Act level. This increase is driven primarily by the higher level of funding in 2014–15 and a 2.9 percent increase in per–capita personal income in 2015–16. (Test 2 is operative in 2015–16, with the guarantee affected primarily by the change in per–capita personal income. Though changes in K–12 enrollment also are part of the calculation of the guarantee, the Governor projects enrollment to be flat from 2014–15 to 2015–16.) The Governor estimates the state will make a $725 million maintenance factor payment in 2015–16—leaving an outstanding maintenance factor of $1.9 billion.

Figure 9

Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14

Revised

|

2014–15

Revised

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Preschool

|

$507

|

$664

|

$657

|

–$8

|

–1%

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$38,005

|

$41,322

|

$41,280

|

–$43

|

—

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

13,671

|

14,184

|

16,068

|

1,885

|

13%

|

|

Subtotals

|

($51,675)

|

($55,506)

|

($57,348)

|

($1,842)

|

(3%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$4,235

|

$4,581

|

$5,002

|

$421

|

9%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

2,178

|

2,321

|

2,628

|

307

|

13

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6,413)

|

($6,902)

|

($7,630)

|

($728)

|

(11%)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$78

|

$80

|

$80

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$58,673

|

$63,153

|

$65,716

|

$2,563

|

4%

|

|

General Fund

|

$42,824

|

$46,648

|

$47,019

|

$371

|

1%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

15,849

|

16,505

|

18,697

|

2,192

|

13

|

Despite Significant Growth in 2015–16 Guarantee, Only Slight Increase in General Fund Spending. As shown at the bottom of Figure 9, Proposition 98 General Fund for 2015–16 is up only $371 million (1 percent) from the prior year whereas local property tax revenue is up $2.2 billion (13 percent). The primary reason growth in local property tax revenue is so significant has to do with the end of the “triple flip.” The Governor’s budget assumes the triple flip ends in 2015, thereby triggering the flow of significant local property tax revenues back to school and community college districts from cities, counties, and special districts. Local property tax revenue also is higher in 2015–16 due to growth in assessed property values (at about the historical average). Additionally, a small part of the growth in 2015–16 is due to local property tax revenues flowing back to school and community college districts from former redevelopment agencies.

Provides $4 Billion Increase for Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The largest funding increase in the Governor’s budget is for the LCFF. As shown in Figure 10, the Governor’s budget provides an additional $4 billion for LCFF, reflecting a 9 percent year–over–year increase. The Governor estimates the increase will close 32 percent of the remaining gap between school districts’ 2014–15 funding levels and full LCFF implementation rates. Under the Governor’s proposal, we estimate that LCFF will be approximately 85 percent funded. The Governor’s plan to dedicate most additional ongoing K–12 funding to LCFF implementation is consistent with the budget approach the Legislature has taken the past two years. Dedicating almost all new ongoing K–12 funds to LCFF helps further the phase in and retains the state’s emphasis on local control and flexibility.

Figure 10

Proposition 98 Spending Changes

(In Millions)

|

Revised 2014–15 Proposition 98 Spending

|

$63,153

|

|

Technical Adjustments

|

|

|

Remove prior–year one–time payments

|

–$3,503

|

|

Make LCFF growth adjustments

|

53

|

|

Adjust energy efficiency funds

|

15

|

|

Provide growth for categorical programs

|

21

|

|

Annualize funding for 4,000 new preschool slots

|

15

|

|

Make other adjustments

|

213

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$3,186)

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

Fund LCFF increase for school districts

|

$4,048

|

|

Fund Internet infrastructure grants (one–time)

|

100

|

|

Provide K–12 COLA for select programs

|

71

|

|

Increase funding for the Charter School Facility Grant Program

|

50

|

|

Other

|

2

|

|

Subtotal

|

($4,271)

|

|

Workforce Education and Training

|

|

|

Fund adult education consortia

|

$500

|

|

Fund career technical education grants (one–time)

|

250

|

|

Fund certain noncredit courses at credit rate

|

49

|

|

Fund new apprenticeships in high–demand occupations

|

15

|

|

Increase funding for established apprenticeships

|

14

|

|

Subtotal

|

($828)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

Pay down mandate backlog (one–time)

|

$125

|

|

Provide apportionment increase (above growth and COLA)

|

125

|

|

Fund 2 percent enrollment growth

|

107

|

|

Augment Student Success and Support Program

|

100

|

|

Fund implementation of local student equity plans

|

100

|

|

Provide 1.58 percent COLA for apportionments

|

92

|

|

Subtotal

|

($650)

|

|

Total Changes

|

$2,563

|

|

2015–16 Proposition 98 Spending Level

|

$65,716

|

The Governor’s budget proposes $876 million (Proposition 98) in additional spending for various workforce education and training initiatives, as detailed below. (Of this amount, $828 million is attributed to 2015–16 and $48 million to 2014–15.)

Proposes $500 Million for Adult Education Consortia. The Governor’s budget provides $500 million in ongoing funding for adult education programs. This proposal follows a two–year planning period in which school districts, community college districts, and other stakeholders formed 70 adult education consortia to assess, plan, and coordinate adult education services regionally. Under the proposal, the funds would support programs in five instructional areas: (1) elementary and secondary basic skills, (2) citizenship and English as a second language for immigrants, (3) education programs for adults with disabilities, (4) short–term career technical education (CTE) in occupations with high employment potential, and (5) programs for apprentices.

For 2015–16 only, the new funds would replace, dollar–for–dollar, LCFF funds currently allocated to school district–run adult education programs in these five areas. (While the exact amount of the $500 million needed for this purpose would be determined at a later date, the administration estimates it to be about $350 million.) The Superintendent of Public Instruction and the CCC Chancellor’s Office would allocate the remainder of the funds to consortia based on regional adult education needs. Each consortium, in turn, would form a seven–member allocation committee representing school districts, community colleges, other adult education providers, local workforce investment boards, county social services departments, and correctional rehabilitation programs, with one public member, to distribute the funding to adult education providers within the region.

The administration indicates that it will provide a more comprehensive proposal, including a new accountability system, student placement criteria, and linked data systems following receipt of regional adult education plans. Statute requires the CCC Chancellor’s Office and the California Department of Education (CDE) to submit a joint report by March 1, 2015, detailing these regional plans and making recommendations for additional improvements to the adult education delivery system.

Proposes $250 Million for CTE Incentive Grant Program. The budget provides $250 million for a competitive grant initiative that supports K–12 CTE programs that lead to industry–recognized credentials or postsecondary training. Under the Governor’s plan, this appropriation is to be the first of three annual $250 million installments to support CTE infrastructure during LCFF implementation. As a condition of receiving funds, grantees would be required to provide a dollar–for–dollar match, collect accountability data, and commit to providing ongoing support for CTE programs after the grant program expires. Applicants also would be expected to partner with local postsecondary institutions, businesses, and labor organizations. Local education agencies that currently invest in CTE programs and local education agencies that collaborate with each other are to receive funding priority. The administration indicates that it will present additional program details, including grant amounts, at a later date.

Extends CTE Pathways Initiative for One Year. The Governor’s plan includes $48 million to extend the CTE Pathways Initiative grant program for an additional year. The initiative is scheduled to sunset at the end of 2014–15. The initiative supports or supplements a variety of CTE programs at schools and community colleges that improve career pathways and linkages across schools, community colleges, universities, and local businesses. The CDE and CCC Chancellor’s Office jointly allocate funding annually for programs through an interagency agreement. In previous years, community colleges received about two–thirds of the funding and K–12 programs received about one–third of the funding.

Increases Funding for Apprenticeships. The Governor provides an augmentation of $29 million for apprenticeship programs (bringing total funding to $52 million). Of the augmentation, $14 million is for existing apprenticeship programs and $15 million is for new programs in occupations with unmet labor market demand. Funding would support both secondary and postsecondary programs.

Continues Existing Workforce Education and Training Programs. The Governor’s plan maintains several existing CTE programs under Proposition 98. These include California Partnership Academies, Specialized Secondary Programs, the Agricultural CTE Incentive Program, the CCC Economic Development program, and the Adults in Correctional Facilities program. In addition, the budget includes $49 million to fund certain CCC workforce–related noncredit courses at the credit rate, as required by budget–related legislation adopted in 2014.

Governor’s Workforce Education and Training Goals Laudable. The Governor’s Budget Summary describes a comprehensive approach to workforce development that would align training providers and resources to meet regional and industry workforce needs. The summary characterizes the Governor’s budget proposals as a first step toward this broader vision. We think the Governor’s focus on coordination and alignment is laudable. Moreover, we acknowledge that forging a coherent system from multiple existing programs is a significant undertaking that will require several years to complete. We believe now is an opportune time to begin this work. Dedicated funding for two of the state’s major workforce education and training programs—school district–run adult education and high school Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROCP)—will terminate at the end of 2014–15. Moreover, the recent reauthorization of the federal Workforce Investment Act requires enhanced coordination across workforce development providers.

Plan Limits Disruption to Existing Programs. The Governor’s plan takes steps to minimize disruption for established adult education providers and ROCP programs during the transition to a more coordinated workforce development system. Specifically, by protecting funding for adult education programs for an additional year and setting a clear expectation that regional consortia will allocate funds following this transition period, the budget retains some continuity of adult education services. Similarly, providing grant funding opportunities for ROCPs for three more years could minimize disruption of their services during the transition to LCFF and development of the new workforce development system.

More Work Needed to Unify Workforce Development Efforts. Although we believe the Governor’s workforce initiative contains laudable goals, we believe it has room for improvement. Notably, although the Governor’s plan emphasizes regional collaboration, it does nothing to streamline existing, overlapping regional groupings—including the 15 CCC economic development regions, the 49 workforce investment boards, the 70 adult education consortia, and numerous other ad–hoc groupings emerging from recent grant initiatives (such as regional partnerships formed in response to the Career Pathways Trust program). Having so many overlapping regional agencies creates significant duplication for workforce development providers and makes creating coherent programs much more logistically challenging.

In addition, the Governor’s proposals could further fragment workforce efforts by augmenting certain existing programs while simultaneously creating new programs with similar workforce objectives. This fragmentation is further exacerbated because adult education consortia also are entrusted with fulfilling similar workforce objectives—CTE and apprenticeships being two of their five priority areas (as specified in statute). We are concerned that such a piecemeal approach could be counterproductive and result in additional redundancies and inefficiencies in the state’s workforce development system.

Proposes Additional $100 Million for Internet Infrastructure Improvements. The Governor’s budget includes $100 million in one–time funding for CDE to administer a second round of Broadband Infrastructure Improvement Grants (BIIG). (The 2014–15 budget provided $26.7 million in one–time funding for the first round of BIIG awards.) These competitive awards would be used to pay for the costs of improving Internet infrastructure to school sites (also known as schools’ “last–mile connections”). Eligible applicants must demonstrate they are unable to administer the new Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium online tests or unable to administer the tests without curtailing their other Internet activities. Grantees must commit to funding the ongoing costs of their new Internet service from their general purpose funds.

Initial Concerns With Governor’s Proposal. One initial concern with the Governor’s proposal is that the amount of proposed funding does not appear to be linked with an assessment of existing Internet capacity required to administer the online tests. (The K–12 High Speed Network, in consultation with CDE and the State Board of Education, is currently preparing such an assessment. Statute requires this report to be submitted by March 1, 2015. This assessment might help determine how much additional funding, if any, is warranted.) Another initial concern is that the proposal appears to reward certain districts that have chosen to invest less in Internet infrastructure than other districts. The proposal also does not appear to address key underlying issues, such as the willingness of providers to build infrastructure in certain areas of the state.

Building upon efforts of the past few years, the Governor’s budget also includes proposals to pay down outstanding education obligations, as discussed below.

Provides $1.5 Billion to Reduce Mandate Backlog. Estimates of the state’s backlog of unpaid claims for education mandates ranges from $4 billion to $5 billion (largely depending on the outcome of active legislation). The Governor proposes to provide $1.5 billion ($1.1 billion for schools and $379 million for community colleges) to reduce this backlog. (From an accounting perspective, $93 million of this amount is scored to 2009–10, $301 million to 2013–14, $975 million to 2014–15, and $125 million to 2015–16.) Funds would be distributed to schools and community colleges on a per–student basis. The Governor indicates the funds for schools could help them implement the academic standards adopted by the state several years ago, though districts are free to spend the funds for any purpose. Similarly, the Governor expects community colleges to use their funds for deferred facilities maintenance, instructional equipment, and other one–time costs, though these funds also may be used for any purpose.

Provides $992 Million to Retire All Remaining Deferrals. As of the 2014–15 Budget Act, the state had $992 million in outstanding payment deferrals (that is, late payments to schools and community colleges). Of this amount, $897 million relates to schools and $95 million relates to community colleges. The 2014–15 budget package included a statutory provision providing that any increase in the 2013–14 or 2014–15 minimum guarantees first be used to pay down these deferrals. Consistent with this requirement and the updated estimates of the 2013–14 and 2014–15 minimum guarantees, the Governor’s budget package includes $992 million to eliminate all deferrals.

Provides Final $273 Million Payment for Emergency Repair Program (ERP). The ERP was created in 2004 through legislation associated with the Williams settlement. The program was intended to provide low–performing schools with a total of $800 million for emergency facility repairs. (Of the $273 million proposed for ERP in 2015–16, $163 million comes from a settle–up payment and $110 million comes from unspent prior–year Proposition 98 funds.) Given the state already has provided $526 million for this program, the additional $273 million payment would retire the state’s ERP obligation.

Proposed Budget Makes Notable Progress Toward Retiring Education Obligations. The Governor’s budget package would allow the state to retire two obligations that have been outstanding for many years. By paying down the remaining deferrals, the state would return to the statutory payment schedule for the first time since 2000–01. For schools and community colleges, returning to the days of timely state payments likely will improve cash flow and reduce reliance on short–term borrowing. For ERP, more than ten years has elapsed since the time the state decided to reimburse districts for emergency repairs. For mandates, though the Governor’s plan does not eliminate the backlog, it makes significant progress in paying it down. We believe the Governor’s approach to paying off existing obligations makes sense, particularly while state revenues are strong and before the next economic downturn.

As discussed earlier in this report, the state’s 2014–15 revenue estimates could be up significantly come May relative to the Governor’s budget. What might happen to state revenues thereafter is uncertain. Changes to the state’s revenue condition will have important implications for Proposition 98 programs—affecting both how much Proposition 98 funding is available and how the Legislature might want to allocate this funding among one–time and ongoing purposes. We discuss these implications in more detail below.

2014–15 Guarantee Could Be Up Notably in May, With Additional One–Time Proposition 98 Funding Required. As mentioned earlier, the guarantee in 2014–15 is highly sensitive to changes in state General Fund revenue, with a near dollar–for–dollar effect on the guarantee. That is, if 2014–15 revenue estimates were to be revised upward by $2 billion this coming May, then the estimate of the 2014–15 guarantee likewise would increase by about $2 billion. The Legislature could begin considering how it might allocate such a large, year–end funding increase to schools and community colleges.

A Caution Against Committing All New Funds to Ongoing Purposes. Were stock market prices to drop in 2015 or growth in the economy and personal income to slow, the guarantee could drop from the level now proposed by the administration for 2015–16. Such a scenario serves as a caution against the state committing all available 2015–16 monies within the Proposition 98 guarantee for ongoing purposes. Were the Legislature to commit all these funds for ongoing purposes, it then would be in the problematic position of having to cut ongoing programs, potentially backpedalling in its implementation of the LCFF.

More Than $1 Billion General Fund Increase for Higher Education. California’s publicly funded higher education system consists of UC, CSU, CCC, Hastings College of the Law, the California Student Aid Commission, and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM). As shown in Figure 11, the Governor’s budget provides $14.4 billion in General Fund support for higher education in 2015–16. This is $1 billion (8 percent) more than the revised 2014–15 level. About half of the additional funding is for adult education consortia (discussed in the Proposition 98 section of this report). The Governor’s other major policy proposals (discussed below) fund base increases at the segments, CCC enrollment growth, CCC student support services, and an award program to increase graduation rates at CSU. The budget also includes funding (not discussed below) for increased participation in Cal Grants, the second–year phase–in of Middle Class Scholarships, and bond repayments that support CIRM research. An additional proposal to fund deferred maintenance at UC and CSU is discussed in the Infrastructure section of this report.

Figure 11

Higher Education General Fund Supporta

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14

Actual

|

2014–15

Estimated

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$2,844

|

$2,991

|

$3,131

|

$140

|

5%

|

|

California State University

|

2,769

|

3,026

|

3,179

|

153

|

5

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

4,622

|

5,019

|

5,443

|

424

|

8

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

1,703

|

2,011

|

2,226

|

216

|

11

|

|

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

|

95

|

271

|

383

|

112

|

42

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

1

|

13

|

|

Awards for Innovation

|

—

|

50

|

25

|

–25

|

–50

|

|

Totals

|

$12,043

|

$13,378

|

$14,399

|

$1,021

|

8%

|

Governor’s 2015–16 Higher Education Plan Somewhat Better Tailored to Challenges Facing UC, CSU, and CCC. In his last two budget proposals, the Governor treated the state’s two public university systems virtually identically, even though the two systems differ in missions, cost structures, and outcomes. One laudable feature of the Governor’s budget plan for 2015–16 is a tailoring of certain proposals to the main challenges facing the different systems. Most notably, the Governor has a proposal for UC that primarily attempts to constrain costs (which remain high compared to other public research universities) and a proposal for CSU that attempts to improve student outcomes (which remain low by various measures). The Governor also targets funding toward student support services at CCC, whose students continue to have very low program completion and graduation rates. Targeting funding proposals to the unique challenges facing each segment is a more effective use of state resources. Though the Governor’s plan generally is better tailored than previous years, some of the Governor’s proposals treat the segments differently without solid justification.

Proposes Cost–of–Living Adjustment (COLA) for Community Colleges. The Governor provides the community colleges with a $92 million (1.6 percent) COLA. The COLA is calculated pursuant to a formula in state law that uses a state and local price index for government agencies.

Proposes Three Unallocated Base Increases. In addition to the COLA for the community colleges, the Governor provides the system with a $125 million (2.1 percent) unallocated base increase to account for increased operating expenses “in the areas of facilities, retirement benefits, professional development, converting part–time to full–time faculty, and other general expenses.” For each UC and CSU, the Governor proposes $119 million (4 percent) unallocated base increases. These increases represent the third annual installment in the Governor’s four–year funding plan. Under this plan, the universities received 5 percent annual base funding increases in 2013–14 and 2014–15 and would receive another 4 percent increase in 2016–17. For UC only, the 2015–16 base increase is contingent upon the university (1) not raising tuition in 2015–16, (2) not increasing nonresident enrollment in 2015–16, and (3) taking action to constrain costs. The Governor further expects UC to form a committee, supported by staff of the UC Office of the President and the Governor, to develop proposals to reduce costs, enhance undergraduate access, and improve time–to–degree and degree completion.

Unallocated Approach Raises Concern. Of the four base increases provided by the Governor, only the COLA for the community colleges is associated with a specific purpose. That is, the COLA provided to the community colleges is widely understood to cover increased general operating expenses—such as for faculty and staff salaries and classroom materials—as measured by an inflation index specified in statute. In contrast, the Governor remains silent on the objective of the base increases for UC and CSU, and he does not convey the objective of the additional base increase for CCC clearly (that is, the associated CCC language identifies myriad possible uses, without ensuring that the funds actually are spent on those identified priorities). Because the Governor does not clearly articulate the justification for these three unallocated base increases, the Legislature likely will have difficulty assessing whether the augmentations are needed and ultimately whether any monies provided would be spent on the highest state priorities.

Unallocated Base Increases to UC and CSU Could Be Converted to COLA. A reasonable case could be made that the Governor intends for the UC and CSU unallocated base increases to function as COLAs. For example, both universities’ governing boards adopted budgets in November 2014 that assume additional state funds for general cost increases. Moreover, the base increases provided by the Governor are in the ballpark of the COLA he provides to the community colleges. The Legislature could consider taking a more transparent approach that links funding with expected costs by providing base increases for the universities based on an inflation index. Such an approach would be consistent with the way the state in the past has budgeted for UC and CSU and the way it currently budgets for schools and community colleges. Furthermore, the approach itself (replacing unallocated base increases with a COLA and other targeted appropriations) likely would help foster a clearer dialogue regarding the amount required to fund specific higher education priorities, such as enrollment growth, improved student outcomes, pension obligations, and facility maintenance.

Assumes No Tuition and Fee Increases. Although the Governor acknowledges in his budget summary that public higher education in California is relatively affordable for resident students (due to high public subsidies, relatively low tuition and fees, and robust financial aid programs), he expects the universities to maintain tuition at current levels. The Governor also proposes no fee increase at the community colleges. UC, CSU, and CCC resident tuition/educational fee levels have been flat since 2011–12.

Changing the Tuition Debate. Currently, much of the discussion surrounding university funding is centered around who should pay for cost increases—students and their families or the state. In our view, an equally, if not more important, question pertains to the overall cost of a college education and how it increases from year to year. One of the main reasons we have long argued for a share–of–cost fee policy is that any cost increases would affect all parties—state taxpayers, the universities, and students—such that all parties have an interest in monitoring costs and scrutinizing proposed cost increases while keeping an eye on quality and affordability. That is, the first order of such a policy is to shed greater light on overall cost and improve the public dialogue around whether cost increases are appropriate given all competing higher education objectives. A share–of–cost policy also has other benefits, including potentially reducing future volatility in fee levels and resulting in generations of students being treated more equally over time (if the policy were consistently applied).

Governor Expresses Major Concerns With Enrollment–Based Budgeting. Similar to his 2013–14 and 2014–15 budget proposals, the Governor outlines a number of serious concerns with enrollment growth funding. In particular, the Governor asserts that funding enrollment growth does not encourage postsecondary institutions to focus on affordability, student completion, and educational quality. He further states that enrollment–based funding fails to provide incentives for institutions to increase the productivity of the higher education system as a whole.

Provides Enrollment Growth at Community Colleges but Not Universities. The Governor provides $107 million for 2 percent enrollment growth at CCC. This equates to serving about 23,000 additional full–time students. In contrast, the Governor proposes no resident enrollment targets or enrollment growth funding for the universities, consistent with his critique of enrollment–based funding. The Governor’s budget documents show resident enrollment flat in the budget year at UC and growing by 0.8 percent at CSU. (In a November 2014 report to the Governor and the Legislature, UC indicated that it would reduce resident enrollment by about 2 percent in 2015–16 unless it receives a larger base augmentation than the Governor proposes. How UC ultimately will adjust 2015–16 enrollment levels in response to the Governor’s budget proposal remains unclear.)

Access, Quality, and Cost Controls All Important State Priorities. The Governor makes reasonable observations about the lack of incentives in enrollment–based funding for institutions to improve student outcomes and reduce costs. Nonetheless, linking funding with enrollment serves an important state purpose because it (1) expresses the state’s priority for student access and (2) connects funding with student–generated costs. Despite these benefits, the Governor continues to discard the state’s longstanding enrollment funding practices for UC and CSU. The administration also has not been supportive of funding a new university eligibility study—as a result, the state has limited information on whether UC and CSU continue to meet Master Plan goals for student access. In contrast, the budgeting approach the Governor takes with CCC, by funding both enrollment and student success, appears to better balance the twin goals of access and quality.

Proposes Major Augmentation for CCC Student Support. The Governor proposes a $200 million augmentation to CCC’s Student Success and Support Program, bringing the total for the program to $472 million. Of the $200 million, the Governor designates half to increase assessment, placement, and orientation for new students, as well as academic counseling and tutoring for both new and continuing students. The CCC Chancellor’s Office would allocate these funds based in part on the number and types of support services each district provides. The Governor designates the remaining $100 million to implement local student equity plans. The purpose of these plans is to improve access and outcomes (such as degree or certificate completion) for all students, identify any disparities in achievement for disadvantaged groups, and address any such disparities. The Chancellor’s Office would allocate these funds based in part on measures of disadvantage, such as a district’s poverty and unemployment rates. (Community colleges could provide the same types of activities under both components of the proposed augmentation but likely would further target activities under the second component to disadvantaged groups.)

Focus on CCC Student Success Warranted, but Approach May Be Too Limited. Several recent reports and CCC outcome data support the need for more attention to CCC student success, and the Legislature has shown strong interest in improving student outcomes. As we noted in our 2014–15 Analysis of the Higher Education Budget, however, we are concerned that the Governor’s approach is too narrowly focused. As state and national research has shown, some types of students can benefit from different support services and many students can benefit from multiple types of support. Currently, the state funds specific types of support for CCC students through eight separate categorical programs. Providing more flexibility to use student support funds would enable colleges to allocate funding in a way that best meets the needs of their students. In addition, the Legislature could explore ways to make improvements in student outcomes a factor in the allocation of support services funding.

Proposes Targeting Awards to Improving Graduation Rates at CSU. The Governor proposes $25 million in one–time awards to CSU campuses that are implementing initiatives to improve four–year graduation rates. This proposal differs from the 2014–15 awards, which will be granted to UC, CSU, and CCC campuses that are achieving a broader set of goals. Similar to last year’s awards, a committee comprised of appointees from the Department of Finance, the governing boards of the segments, and the Legislature would make award decisions in a competitive process.

Proposal Raises Several Questions. Consistent with the Governor’s emphasis, data suggest that CSU student performance is lackluster, with only 18 percent of full–time freshmen graduating within four years and only about half graduating within six years. The causes of the performance problem and how best to respond to them, however, are less clear. Are CSU’s low graduation rates due to lack of preparation among entering freshmen, low retention rates from freshmen to sophomore year, poor fee and financial aid incentives, weak incentives to take 15 units per term, students working excessive hours, lack of access to required courses, or other problems? The Governor’s approach to innovation awards appears to tackle a single symptom—that is, low graduation rates—without more comprehensively and systematically addressing underlying issues. We also continue to think relying solely on a small, one–time earmark is a poor budgetary approach for addressing a longstanding CSU performance problem, particularly given student success is so central to CSU’s ongoing mission.