Legislature Authorizes California State University (CSU) To Award Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) Degrees. Existing law assigns authority to the University of California (UC) for awarding doctoral degrees independently. As an exception to this rule, Chapter 425, Statutes of 2010 (AB 2382, Blumenfield), authorizes CSU to independently award DPT degrees. The legislation followed a 2009 decision by the sole organization recognized by the federal government to accredit physical therapy programs to no longer accredit programs at the master’s level. The legislation requires CSU, the Department of Finance, and the Legislative Analyst’s Office to conduct a joint evaluation of CSU’s new DPT programs by January 2015.

CSU Created Five DPT Programs. CSU converted master of physical therapy programs to DPT programs at four campuses (Fresno, Sacramento, Long Beach, and Northridge). In creating the DPT programs, these campuses enhanced previous master’s level courses and added several new ones, such as digital imaging and pharmacology. These four programs retained enrollment at levels similar to their master’s programs—each enrolling DPT cohorts of about 32 students per year. CSU also created one new DPT program (San Diego). This new program is enrolling about 36 students per year—generating a modest overall increase in CSU graduate physical therapy enrollments compared to pre–DPT levels. All five DPT programs are structured as three–year programs. The programs operate on a year–round basis, with instruction occurring in fall, spring, and summer terms. Students progress through their programs in cohorts, taking the same sequence of courses together. Each program receives several times the number of applicants as available slots. Student persistence has been high for the first few cohorts. (The first student cohort will graduate in spring 2015.)

Student Tuition Funds Most Program Costs. Although some campuses allocate a relatively small amount of state General Fund support to their DPT programs, student tuition funds the majority of DPT program costs. Tuition, capped by Chapter 425 at the UC DPT tuition level, is significantly higher than what students paid for earlier CSU physical therapy master’s programs but lower than they would pay at most private institutions. Higher costs of providing doctoral education account for a portion of the tuition difference. Students on average incur about $72,000 in debt for their DPT programs. Given that average CSU undergraduate debt is about $18,000, students who incur debt from both their undergraduate and DPT programs likely would exceed the recommended threshold for manageable debt—about one year’s worth of expected salary upon graduation.

Programs Help Meet State Demand for Physical Therapists. California’s supply of physical therapists, including new graduates expected from CSU and private institutions, appears more than sufficient to meet the state’s projected need for these professionals over the next decade. CSU has discretion to expand DPT education to other campuses, but has not indicated an intent to do so.

CSU Complies With Programmatic Requirements. The joint review team concluded that CSU DPT programs meet the programmatic requirements of Chapter 425. The programs focus on preparing practicing physical therapists (rather than primarily training academic researchers). CSU also has not reduced its ratio of undergraduate to graduate students, in accordance with the legislation.

Tuition Policy. Campuses currently charge tuition just under the rate for UC’s sole DPT program (which it offers jointly with San Francisco State University). Given the different objectives of CSU and UC doctoral programs, this tuition benchmark is somewhat arbitrary. Policymakers could lower the cap based on the relative faculty course loads at UC and CSU or other cost comparisons. Alternatively, if policymakers chose to eliminate the cap, CSU could set the rates consistent with student demand and the rates charged by similar programs across the country.

Future Expansion of Academic Programs. UC and CSU currently have discretion to expand new academic programs. The segments’ internal approval processes include review by the campus requesting the program, the system offices, the governing boards, and academic accreditors. Prior to 2011, such expansion also required review by a state agency separate from CSU. If policymakers are concerned about the need for external review of new programs, they could require that the segments submit new program proposals to the Legislature and Governor for approval.

Year–Round Programs. Most CSU students enroll only during the fall and spring terms, leaving many campus facilities underutilized during the summer. Year–round schedules would allow the university to accommodate more students (given sufficient funding), thereby reducing bottlenecks in courses requiring laboratories, studios, specialized equipment, and other scarce capital resources. Policymakers may wish to consider encouraging CSU to build on the success of the year–round model in its doctoral programs by expanding this model to other academic programs.

Additional Independent CSU Doctoral Programs. Changes in workforce needs, accreditation requirements, and campus aspirations likely will result in additional proposals to expand doctoral education at CSU. The Legislature and Governor will want to weigh the advantages of new doctoral programs against the higher costs to deliver doctoral education and increased financial barriers for individuals to enter a profession. Should policymakers wish to respond to future proposals to elevate academic programs for accreditation requirements, four options exist: (1) provide alternate routes towards licensure other than completing an accredited academic program; (2) establish state accreditation processes; (3) expand CSU’s authority to provide independent doctoral degrees; and (4) continue to rely on UC and private institutions, rather than CSU, to provide doctoral education.

Report Evaluates Implementation of California State University (CSU) Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) Programs. Chapter 425, Statutes of 2010 (AB 2382, Blumenfield), authorizes CSU to award DPT degrees. The legislation requires CSU, the Department of Finance, and the Legislative Analyst’s Office to jointly conduct a statewide evaluation of the new DPT programs and report the findings to the Legislature and Governor. Below, we provide background on CSU’s development of DPT programs. We then evaluate CSU’s compliance with statutory requirements for these programs and identify a number of issues for further consideration regarding doctoral education at CSU. An appendix contains the full text of Chapter 425, including specific reporting requirements.

1960 Master Plan Gave University of California (UC) Sole Authority to Award Doctoral Degrees. In 1960 the Legislature passed the Donohoe Act, incorporating many provisions of California’s Master Plan for Higher Education into statute. Among these provisions is the assignment of specific missions to the various educational segments. The Donohoe Act assigned CSU responsibility for undergraduate and graduate education in liberal arts and sciences through the master’s degree and primary responsibility for teacher education. It assigned UC responsibility for undergraduate and graduate education through the doctoral degree and primary responsibility for research and public service.

CSU Permitted to Participate in Joint Doctoral Programs. During the discussions leading to the creation of the Master Plan, the state college system (now CSU) sought authority to provide graduate education through the doctoral level, whereas UC sought to maintain its exclusive domain in doctoral education. The inclusion of joint doctorates in the final plan was a compromise between the two systems.

Several Joint Doctoral Programs Created. Over the following decades, UC and CSU developed 30 joint doctoral programs, including 17 doctor of philosophy (Ph.D.) programs (mainly in the sciences and engineering), 9 education doctorate (Ed.D.) programs, 2 DPT programs, a doctor of physical therapy science program, and a doctor of audiology program. In addition, CSU developed 5 joint Ph.D. programs with an independent university (Claremont Graduate University). As shown in Figure 1 , 26 of these programs remain active today, the majority of them at San Diego State University.

Figure 1

CSU Operating 26 Joint Doctoral Programs

|

CSU Campus

|

Partner University

|

Degree

|

Discipline

|

|

Long Beach

|

Claremont Graduate University

|

Ph.D.

|

Engineering and Industrial Applied Mathematics

|

|

Los Angeles

|

UC Los Angeles

|

Ph.D.

|

Special Education

|

|

Sacramento

|

UC Santa Barbara

|

Ph.D.

|

Public History

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Math and Science Education

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Cell and Molecular Biology

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Chemistry

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Clinical Psychology

|

|

San Diego

|

UC Davis

|

Ph.D.

|

Ecology

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Bioengineering

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Electrical and Computer Engineering

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Structural Engineering

|

|

San Diego

|

UC Berkeley

|

Ph.D.

|

Evolutionary Biology

|

|

San Diego

|

UC Santa Barbara

|

Ph.D.

|

Geography

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Geophysics

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Language and Communicative Disorders

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Ph.D.

|

Public Health

|

|

San Diego

|

Claremont Graduate University

|

Ph.D.

|

Information Systems

|

|

San Diego

|

Claremont Graduate University

|

Ph.D.

|

Education

|

|

San Diego

|

Claremont Graduate University

|

Ph.D.

|

Computational Science/Statistics

|

|

San Diego

|

Claremont Graduate University

|

Ph.D.

|

Computational Science

|

|

San Francisco

|

UC Berkeley

|

Ph.D.

|

Special Education

|

|

San Marcos

|

UC San Diego

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Leadership

|

|

Sonoma

|

UC Davis

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Leadership

|

|

San Francisco

|

UC San Francisco

|

DPT

|

Physical Therapy

|

|

San Diego

|

UC San Diego

|

Au.D.

|

Audiology (Au.D. is Doctor of Audiology)

|

State Authorized CSU to Offer Independent Ed.D. Programs in 2005. Forty–five years after adoption of the Master Plan, Chapter 269, Statutes of 2005 (SB 724, Scott), authorized CSU to offer its first independent doctoral degree, the Ed.D. The legislation provided a limited exception to the Master Plan in recognition of the urgency of meeting critical education leadership needs. In response to the legislation, CSU developed independent Ed.D. programs at 14 of its 23 campuses.

State Authorized CSU to Offer Nursing and Physical Therapy Doctorates in 2010. Five years after authorizing CSU to offer its first independent doctoral degrees in education leadership, the Legislature approved two bills expanding this authority for doctoral degrees in clinical professions. Chapter 425 and Chapter 416, Statutes of 2010 (AB 867, Nava), authorized the university to independently award the DPT and doctor of nursing practice (DNP), respectively. Figure 2 lists all of CSU’s active independent doctoral programs. (Some of these programs were converted from former joint doctoral programs with UC, as indicated in the figure.)

Figure 2

CSU Operating 21 Independent Doctoral Programs

|

Campus

|

Degree

|

Discipline

|

Former Joint Program Partners

|

|

East Bay

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadership

|

|

|

Fresno

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

UC Davis

|

|

Fresno at Bakersfield

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

|

|

Fullerton

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

UC Irvineb

|

|

Long Beach

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

UC Irvineb

|

|

Los Angeles

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadership

|

UC Irvineb

|

|

Northridge

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

|

|

Pomona

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadership

|

UC Irvineb

|

|

Sacramento

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

UC Davis

|

|

San Bernardino

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadership

|

|

|

San Diego

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

UC San Diego

|

|

San Francisco

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

UC Berkeley

|

|

San Jose

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadership

|

UC Santa Cruz

|

|

Stanislaus

|

Ed.D.

|

Educational Administration/Leadershipa

|

|

|

Fresno

|

DPT

|

Physical Therapy

|

UC San Francisco

|

|

Long Beach

|

DPT

|

Physical Therapy

|

|

|

Northridge

|

DPT

|

Physical Therapy

|

|

|

Sacramento

|

DPT

|

Physical Therapy

|

|

|

San Diego

|

DPT

|

Physical Therapy

|

|

|

Fresno, San Jose

|

DNP

|

Nursing Practice

|

|

|

Fullerton, Long Beach, Los Angeles

|

DNP

|

Nursing Practice

|

|

Accreditor Set Doctorate as Entry–Level Degree for Physical Therapists. The sole federally recognized accreditor for physical therapy programs in the United States is the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE). This accrediting agency is associated with the American Physical Therapy Association, the professional organization for physical therapists working in the country. In 2009, CAPTE announced that beginning in 2015 it no longer would accredit physical therapy practitioner programs at the master’s level. As a result, the new floor for entry–level physical therapists would become the DPT. This decision continued the evolution of physical therapy education from sub–baccalaureate certificate programs in the first half of the 20th century to baccalaureate programs in the 1960s, followed by adoption of the master’s degree as the minimum standard beginning in 2002. According to CAPTE, this evolution has occurred in response to changing expectations for graduates resulting from significant advances in the science and practice of physical therapy, including the advent of direct patient access to physical therapists, discussed in the nearby box.

Until recently, patients in California could not see a physical therapist for treatment of a condition without first receiving a medical diagnosis from a physician. Without such a diagnosis, patients could see a physical therapist only for general fitness and wellness services. Chapter 620, Statutes of 2013 (AB 1000, Wieckowski), allows patients to self–refer to a physical therapist and receive treatment for 45 calendar days or 12 visits, whichever comes first, before being seen by a physician and receiving sign–off on the treatment plan initiated by a physical therapist. (Statute does not require health plans to offer or pay for these services.) This approach to early physical therapy intervention, commonly called direct access, requires physical therapists to independently diagnose conditions, determine appropriate treatments, and initiate care. Direct access physical therapists also must be able to identify problems that require attention from physicians or other practitioners and refer patients accordingly. This greater scope of practice, already adopted in most states, has been one of the main rationales for elevating physical therapy education to the doctoral level.

Accreditation Necessitated Change at CSU. Because of the higher accreditation requirement, CSU had to phase out its master’s programs and (1) cease offering physical therapy education, (2) develop additional partnerships with UC or other institutions to offer joint entry–level DPT programs, and/or (3) secure legislative authorization to independently offer DPT degrees. CSU and UC have not developed additional joint degrees. CSU did, however, seek and win approval to establish independent DPT programs.

Chapter 425 sets out several requirements regarding the purpose and funding of the new independent DPT programs. Specifically:

DPTs To Be Practitioner–Focused. Chapter 425 requires the independent CSU programs to focus on preparing physical therapists to provide health care services. This requirement seeks to distinguish between the applied doctorates that CSU may offer and the research doctorates that remain the exclusive domain of UC. More specifically, UC’s doctoral degrees typically include basic research and an extensive dissertation requirement, whereas CSU’s DPT programs focus on clinical research and applied doctoral projects.

DPT Programs Not To Diminish Undergraduate Programs. Four requirements in the legislation aim to ensure that enrollment growth in DPT programs not come at the expense of undergraduate programs. The requirements are: (1) enrollment is to be funded from within CSU enrollment growth levels as agreed to in the annual budget act; (2) state funding is to be at the agreed–upon marginal cost rate for CSU students; (3) DPT enrollments may not alter CSU’s ratio of graduate instruction to total enrollment, nor diminish growth in university undergraduate programs; and (4) CSU must provide any start–up funding from existing budgets without diminishing the quality of undergraduate programs.

Tuition Rates Limited to UC Rates. The legislation further specifies that fees charged to students may be no greater than fees for joint CSU and UC DPT programs (or fees for independent UC DPT programs, though none exist to date). This resembles a provision in Chapter 269 limiting CSU Ed.D. program fees to the amount of UC’s doctoral program fees.

In this section we present our findings regarding CSU’s implementation of independent DPT programs and its compliance with the requirements of Chapter 425.

CSU Converted Four Programs From Master’s to Doctoral Level and Created One New DPT Program. The Fresno, Long Beach, Northridge, and Sacramento campuses replaced established master’s programs with DPT programs. San Diego State University created a new DPT program. Although it did not have a master’s degree program in physical therapy, the university had well–established master’s degree programs in kinesiology, exercise physiology, and related disciplines that provided a foundation for its physical therapy curriculum.

Existing Joint Program Continued. In addition, a joint San Francisco State University (SFSU) and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) DPT program, created in 1989, is continuing. Leaders from both campuses cite the advantages of offering a joint program that incorporates CSU’s emphasis on access, applied learning and research, and UC’s long–established focus on research and scholarship. (This is the only physical therapy practitioner education program currently involving a UC campus.) Until recently, CSU Fresno also had a joint program with UCSF, permitting its physical therapy master’s students to earn a DPT with a third year of study. The campus phased out the partnership upon starting its independent DPT.

Curriculum Expands on Master’s Program Requirements. Although DPT programs typically are three years in length compared with two years for their master’s–level predecessors, the inclusion of former prerequisites as degree requirements accounts for a portion of this difference. That is, many students had to complete up to a full year of prerequisites before entering a master’s program, even if they had completed a pre–physical therapy major. (This is because CSU limited many master’s programs to 60 units.) The new DPT programs incorporate some of the former prerequisites into the doctoral curriculum and add a number of new courses. Campuses typically added new courses in evidence–based practice, diagnostic imaging, pharmacology, and diagnosis, as illustrated in Figure 3. Some campuses also modified existing courses to strengthen their emphasis on evidence–based practice and critical thinking skills and increased the amount of time students spend in clinical rotations. (In addition to classroom work, the DPT curriculum includes laboratory work and clinical practice in various inpatient and outpatient settings.) Campuses also enhanced capstone project requirements. Like master’s projects, doctoral projects typically take the form of a case report on the treatment of one patient or participation in faculty–led research. The doctoral projects require higher–level analysis, however, such as more extensive documentation of the evidence considered in determining a patient’s diagnosis and treatment. These curricular changes are meant to better prepare students for the greater level of independence that direct access to patients requires.

Figure 3

DPT Curriculum Builds on Master’s Curriculum

Required DPT Courses at CSU Long Beach

|

New Courses Added (18 Units)

|

|

Imaging

|

Musculoskeletal Practice II

|

|

Pharmacology

|

Intervention for Neuromuscular Disorders II

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

|

Neuromusculoskeletal Practice II

|

|

Current Trends in Physical Therapy

|

Management of Integumentary Disorders

|

|

Advanced Management of Musculoskeletal Disorders

|

Doctoral Project (replaced Directed Research/Thesis)

|

|

Prerequisites and Master’s Courses Converted to Doctoral Courses (96 Units)

|

|

Anatomy

|

Physiology

|

|

Neuroanatomy

|

Pathology

|

|

Tissue Mechanics

|

Professional Interactions

|

|

Advanced Management of Cardiopulmonary Disorders

|

Management of Orthotic and Prosthetic Needs

|

|

Advanced Management of Neuromuscular Disorders

|

Management of the Geriatric Population

|

|

Biomechanical Principles

|

Management of the Pediatric Population

|

|

Acute Care Principles

|

Motor Learning and Motor Control

|

|

Critical Thinking for Physical Therapy

|

Musculoskeletal Practice I

|

|

Electroneuromyographic Management I

|

Neuromusculoskeletal Practice I

|

|

Electroneuromyographic Management II

|

Normal and Pathological Gait

|

|

Evaluation of Neuromuscular Disorders

|

Physical Therapy Across the Life Span

|

|

Examination of Musculoskeletal Disorders

|

Professional Practice Issues

|

|

Exercise Science for Physical Therapy

|

Research Methods

|

|

Health Care Delivery I

|

Clinical Internship I

|

|

Health Care Delivery II

|

Clinical Internship II

|

|

Interventions for Musculoskeletal Disorders

|

Clinical Pathophysiology

|

|

Management of Cardiopulmonary Disorders

|

Clinical Practice I

|

|

Intervention for the Individual With Neuromuscular Disorders I

|

Clinical Practice II

|

Programs Operate Year–Round. The CSU DPT programs are eight or nine semesters in length. Students progress through these programs in cohorts. That is, all students entering a program in a given year take their courses together and are expected to complete the program together. Students proceed sequentially through a nine–semester program in three years, with instruction and clinical work extending throughout the summers.

Program Approval Streamlined for Former Master’s Programs. New educational programs typically require approval at the department, campus, and system levels as well as from institutional accreditors (such as the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, or WASC) and programmatic accreditors (such as CAPTE). With the closure of the California Postsecondary Education Commission in 2011, the state no longer has an administrative agency external to the CSU that reviews academic programs. (The California Bureau for Private Postsecondary Education reviews certain private programs, but it usually relies on programmatic accreditors to assess the quality of these programs.) Programmatic accreditation provides the most intensive of these reviews. The four programs that replaced CAPTE–accredited master’s degree programs, however, did not have to undergo full programmatic reaccreditation from CAPTE at the time of transition. Each received approval from department and campus curriculum committees and the CSU Chancellor’s Office, submitted a “substantive change proposal” to WASC detailing the planned changes, and notified CAPTE of the changes. These programs will undergo full CAPTE reaccreditation as DPT programs when their current accreditation period is over. The new program at San Diego State University was required to go through the full CAPTE accreditation process and will complete full WASC accreditation following graduation of its first entering class.

Sufficient Student Demand for DPT Programs. In addition to recruiting students through undergraduate health science fairs, websites, and referrals, all programs except San Diego use the Physical Therapy Centralized Application Service, which allows an applicant to apply to multiple DPT programs with a single application. The CSU programs aim to enroll between 32 and 36 students per cohort and most of the programs report significantly more qualified applicants than available slots. Figure 4 summarizes qualified applications, admissions, and enrollments for each program. Overall, programs admitted 30 percent of applicants in the last three years, with admission rates ranging from 14 percent to 91 percent. Of those students admitted, 42 percent enrolled. Enrollment rates also varied by campus and year, ranging from 21 percent to 82 percent.

Figure 4

DPT Admission and Enrollment Rates Have Varied

|

Year

|

Qualified Applicantsa

|

Admissiona

|

Admission Rate

|

Enrollment

|

Enrollment Rate

|

|

Fresno

|

|

2012

|

86

|

39

|

45%

|

32

|

82%

|

|

2013

|

55

|

50

|

91

|

32

|

64

|

|

2014

|

162

|

51

|

31

|

32

|

63

|

|

Long Beach

|

|

2012

|

166

|

82

|

49%

|

36

|

44%

|

|

2013

|

163

|

86

|

53

|

29

|

34

|

|

2014

|

297

|

114

|

38

|

38

|

33

|

|

Northridge

|

|

2012

|

827

|

155

|

19%

|

32

|

21%

|

|

2013

|

630

|

109

|

17

|

32

|

29

|

|

2014

|

332

|

112

|

34

|

31

|

28

|

|

Sacramento

|

|

2012

|

239

|

45

|

19%

|

32

|

71%

|

|

2013

|

239

|

49

|

21

|

32

|

65

|

|

2014

|

326

|

46

|

14

|

33

|

72

|

|

San Diego

|

|

2012

|

78

|

64

|

82%

|

36

|

56%

|

|

2013

|

162

|

85

|

52

|

36

|

42

|

|

2014

|

228

|

88

|

39

|

36

|

41

|

Undergraduate Share of Enrollment Has Not Diminished. Because the DPT programs have relatively low enrollment—484 students in the current year, about one–tenth of 1 percent of total CSU enrollment—and four of the five new programs transitioned from master’s–level programs with similar enrollment, the DPT programs have had little effect on the undergraduate share of enrollment. In the year prior to commencement of DPT programs, undergraduate and graduate enrollment accounted for 89 percent and 9.5 percent, respectively, of total enrollment, as shown in Figure 5. Since then, the undergraduate share has increased slightly and the graduate share has dropped to 9.2 percent. (Postbaccalaureate credential students comprise between 1 percent and 2 percent of CSU enrollment.)

Figure 5

Undergraduate Share of Enrollment Has Not Declined

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Full–Time Equivalent Students

|

|

Undergraduate

|

302,817

|

306,233

|

315,931

|

321,744

|

|

Teacher Credential

|

5,969

|

5,300

|

5,299

|

5,517

|

|

Graduate

|

32,494

|

31,694

|

30,725

|

32,994

|

|

Totals

|

341,280

|

343,227

|

351,955

|

360,255

|

|

Share of Enrollment

|

|

Undergraduate

|

88.7%

|

89.2%

|

89.8%

|

89.3%

|

|

Teacher Credential

|

1.7

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

|

Graduate

|

9.5

|

9.2

|

8.7

|

9.2

|

Many Student Characteristics Similar Across Campuses. Students enrolling in independent CSU DPT programs typically are in their mid–20s. Similar to overall CSU enrollment, nearly 60 percent are women and 94 percent are California residents or students eligible for resident tuition. The average college grade point average for enrolled students was 3.6 out of 4.0.

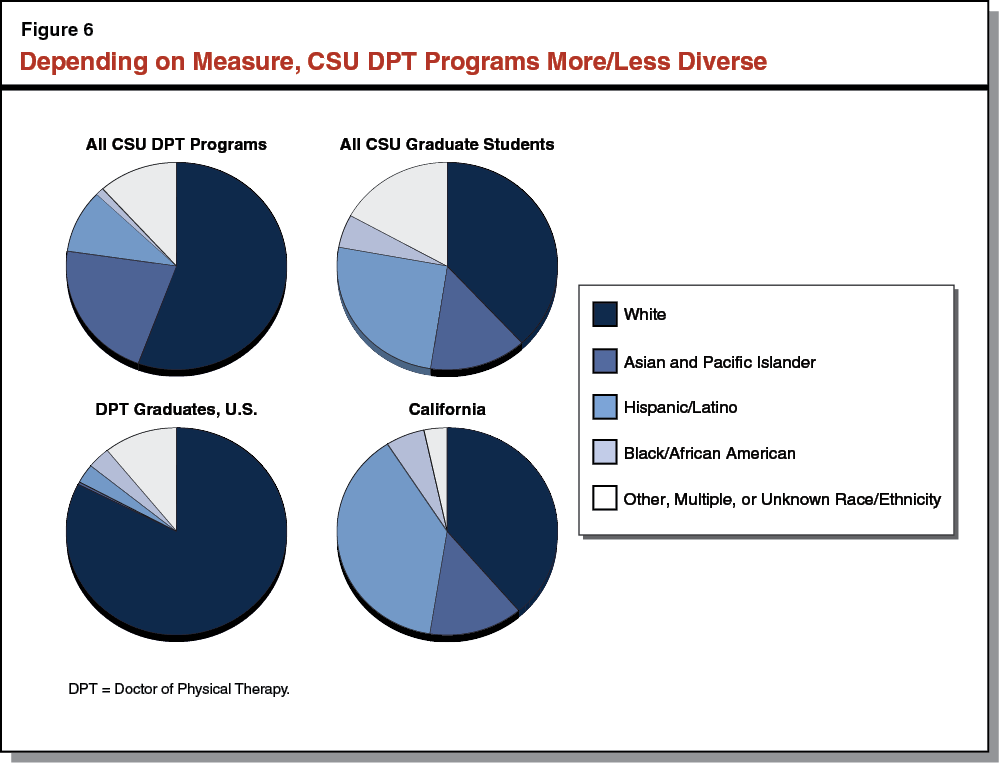

Enrollment Less Diverse Than CSU Graduate Programs Overall and State Population, More Diverse Than National DPT Programs. As shown in Figure 6, the proportion of white and Asian students enrolled in CSU DPT programs is higher than in CSU graduate programs overall and the California population. The proportion of Hispanic and African–American students is lower in CSU’s DPT programs than in its graduate programs and the state population. Although racial and ethnic composition varies somewhat across campuses, these basic patterns hold across all CSU DPT programs. In contrast, national DPT enrollment is notably less diverse than CSU DPT enrollment.

Many Students Motivated by Personal Experiences. In interviews at three CSU campuses, many students attributed their interest in becoming physical therapists to their own experiences with physical therapy professionals. Some had been athletes and received physical therapy treatment. Others had parents or relatives who benefited from physical therapy. Students also were attracted by the prospect of seeing tangible results from their work in the form of markedly improved mobility and quality of life for patients. Students also expressed interest in serving as patients’ point of entry to health care under the new direct access law.

To Date, Student Persistence Has Been High. Of the 329 students who enrolled in 2012–13 and 2013–14, 318 (97 percent) remained enrolled in 2014–15. No comparable data are available regarding student persistence in DPT programs nationally. The first group of entering CSU DPT students currently is in its final year of study, due to complete degrees in spring 2015. As a result, no measure of completion is available for CSU DPT programs.

Employers Do Not Specifically Require DPT. In a review of physical therapist job openings posted by the American Physical Therapy Association, we found that most postings list certificate, bachelor’s degree, or master’s degree as the minimum educational requirement. Others list state licensure. (State licensing requirements are such that a new graduate must be from a DPT program beginning in 2015, but an earlier graduate need not hold a DPT, as described in the nearby box.) Employers report that they do not give preference to candidates with a DPT over candidates with other degrees and do not offer a salary differential based on educational level.

New Graduates Will Need Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) Degree To Qualify for License. The Physical Therapy Board of California in the Department of Consumer Affairs oversees physical therapy licensing and practice in California. Under the board’s regulations, to receive a license an applicant must be a graduate of an accredited physical therapy program. (Candidates also must pass a national physical therapy exam and an exam on California laws related to the practice of physical therapy.) Because only DPT programs will be eligible for accreditation as of 2015, the DPT will become the de facto educational requirement for licensure of new graduates in California. Physical therapists holding a pre–2015 certificate, bachelor’s degree, or master’s degree in physical therapy from an accredited program will continue to qualify for state licensure. This is because these applicants graduated from an accredited program—even if that program would not qualify for accreditation today.

Relatively High Earnings for Physical Therapists. The median annual salary for physical therapists in California was $91,000 in 2014. This group includes experienced physical therapists as well as new graduates. (By comparison, median salary for all workers in California is less than $40,000.) Based on our review of job listings and interviews with employers, it appears entry–level physical therapists initially can expect to earn between $50,000 and $80,000 annually and increase their income thereafter as they gain experience. One–fourth of California physical therapists earn $107,000 or more annually.

Chapter 425 calls for this report to consider the job placement of graduates. As noted, the first CSU DPT cohort is not expected to graduate until the end of spring 2015. According to CSU, its physical therapy master’s degree graduates had a 100 percent job placement rate, and campuses expect the new DPT programs to match this record. Below, we present information about statewide physical therapist demand and supply from public sources and interviews with employers.

High Employment Growth Projected. Figure 7 summarizes employment demand and supply data for physical therapists in California. Between 2012 and 2022, the California Employment Development Department projects nearly 900 average annual physical therapy job openings, reflecting average annual growth of 2.6 percent. The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects even faster average growth—3.1 percent annually—for the same period. Both of these estimates are much higher than growth projected for all occupations, estimated at 1.4 percent by the California Employment Development Department and just over 1 percent by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Analysts attribute the growing demand for physical therapy services to the aging U.S. population, increases in the prevalence of chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity that restrict mobility, and baby boomers staying active later in life.

Figure 7

Despite High Employment Growth, Supply of Physical Therapists Adequate

|

Employment Demand for Physical Therapists in California

|

|

Average Annual Job Openings, Projected 2012–2022

|

|

|

Jobs from growth

|

470

|

|

Jobs from replacement

|

400

|

|

Total Estimated Job Openings

|

870

|

|

Supply of New DPT Graduates in California

|

|

|

Estimate of Annual Graduates Based on Current Enrollment Levels

|

|

|

CSU independent and joint programs

|

182

|

|

Private nonprofit programs

|

434

|

|

Private for–profit programs

|

173

|

|

Total

|

789

|

|

Supply of Newly Licensed Physical Therapists in California

|

|

|

New License Applications and Awards, 2013–14

|

|

|

Applicants—graduated from U.S. schoolsa

|

1,204

|

|

Applicants—graduated from foreign schools

|

314

|

|

Total Applicants

|

1,518

|

|

Licenses Awarded

|

1,192

|

Demand Varies by Region and Setting. Physical therapist shortages exist in rural areas of California and in nursing homes. Employers report the least difficulty in hiring PTs for academic medical centers and facilities with advanced training programs. These sites receive many qualified applicants for open positions.

Limited Increase in Supply From CSU Programs. In total, the six CSU DPT programs (including the joint UCSF–SFSU program) expect to produce about 200 graduates annually over the coming decade. Master’s programs at CSU and the joint doctoral program already were producing close to this number of graduates before the transition to DPT programs. Only San Diego State University began an entirely new program, which expects to produce about 30 graduates annually. Nine private institutions offer DPT programs in the state that collectively generate about 600 graduates annually. Altogether, the projected supply of new PTs from California’s education programs is sufficient to fill about 90 percent of projected job openings.

State Attracts Physical Therapists From Other States and Countries. The California Physical Therapy Board awarded about 1,200 new licenses in 2013–14. According to the board, this number has been growing 5 percent to 8 percent annually in recent years. Four–fifths of license applications are from graduates of U.S. schools, including those in California. The remaining applicants are graduates of foreign schools. The annual number of newly licensed physical therapists in California exceeds projected job openings by about one–third.

Total Program Funding and Costs Vary by Campus. Figure 8 summarizes program revenues and costs, as reported by the CSU Chancellor’s Office. Program revenues range from $1.4 million at the Fresno, Long Beach, and San Diego campuses to $1.8 million at Sacramento. Program costs closely match revenues, with each program generating a surplus or deficit of less than 1 percent.

Figure 8

DPT Program Funding and Costs Vary by Campus

2014–15, Budgeted

|

|

Fresno

|

Long Beach

|

Northridge

|

Sacramento

|

San Diego

|

|

Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net Tuition Revenuea

|

$1,384,852

|

$1,065,206

|

$1,405,601

|

$1,476,815

|

$1,251,885

|

|

State General Fund

|

—

|

232,145

|

320,042

|

282,000

|

—

|

|

From Campus General–Purpose Funds

|

—

|

150,000

|

—

|

—

|

100,000

|

|

Totals

|

$1,384,852

|

$1,447,351

|

$1,725,643

|

$1,758,815

|

$1,351,885

|

|

Costs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instructional Faculty

|

$854,606

|

$843,172

|

$1,223,100

|

$950,940

|

$757,884

|

|

Administrative Faculty and Staff

|

286,733

|

314,661

|

310,560

|

412,916

|

213,154

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,141,339)

|

($1,157,833)

|

($1,533,660)

|

($1,363,856)

|

($971,038)

|

|

Other Direct Costs

|

242,896

|

288,148

|

187,200

|

239,908

|

127,000

|

|

Subtotals, Program Costs

|

1,384,235

|

1,445,981

|

1,720,860

|

1,603,764

|

1,098,038

|

|

Campus Overhead

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

150,000

|

260,000

|

|

Total Costs

|

$1,384,235

|

$1,445,981

|

$1,720,860

|

$1,753,764

|

1,358,038

|

|

Difference

|

$617

|

$1,370

|

$4,783

|

$5,051

|

–$6,153

|

|

Full–Time Equivalent Students (FTES)

|

143

|

147

|

140

|

141

|

158

|

|

Net Tuition Revenue per FTES

|

$9,684

|

$7,246

|

$10,040

|

$10,474

|

$7,923

|

|

State General Fund per FTES

|

—

|

1,579

|

2,286

|

2,000

|

—

|

|

Campus General–Purpose Funds per FTES

|

—

|

1,020

|

—

|

—

|

633

|

|

Total Revenue per FTES

|

$9,827

|

$9,993

|

$12,466

|

$12,615

|

$8,714

|

|

Program Spending per FTES

|

9,680

|

9,837

|

12,292

|

11,374

|

6,950

|

Per–Student Funding and Costs Also Vary by Campus. On a per full–time equivalent student (FTES) basis, the five DPT programs collect an average of about $9,000 in net tuition revenue, $1,150 in state General Fund support, and $350 in other campus resources annually. Of this amount, campuses report spending an average of almost $10,000 per FTES for direct program costs and the remaining $500 per FTES on campus overhead. These amounts vary substantially by campus. Net tuition revenue per FTES ranges from $7,246 at Long Beach, where several students qualified for statutory tuition waivers, to $10,474 at Sacramento. (Statutory tuition waivers primarily are for children and dependents of disabled or deceased military and public safety personnel.) State General Fund support allocated to DPT programs varies from none at Fresno and San Diego to nearly $2,300 per FTES at Northridge. Total funding per FTES ranges from about $8,700 at San Diego to more than $12,000 at Northridge and Sacramento. (A variety of factors, including differences in the sizes of student cohorts and faculty compensation, explain these differences in funding per student.)

Annual Tuition Rate Overstates Net Tuition Revenue Per FTES. The CSU Board of Trustees establishes systemwide tuition and fee levels for all programs. The systemwide tuition rate for the DPT program is $24,222 annually ($8,074 per term for fall, spring, and summer terms). As noted, net tuition revenue averages $9,000 per FTES with substantial variation across programs. Two main factors account for the difference between the annual tuition rate and net tuition revenue per FTES. Firstly, annual tuition for a DPT student is based on 36 units of coursework whereas a standard graduate FTES equates to 24 units of coursework. As a result, one DPT student counts as 1.5 FTES. The $24,222 year–round tuition rate amounts to $16,148 per FTES. Secondly, campuses redirect one–third of tuition revenue to financial aid for DPT students and count only the remaining two–thirds as net revenue. The remaining two–thirds of the tuition rate per FTES is $10,765. This amount is further reduced at the campuses to varying degrees by statutory tuition waivers.

Campuses Determine General Fund Allocation for CSU Degree Programs. While state General Fund support varies across the CSU system, campuses receive an average of about $6,400 per FTES. Campuses have discretion about how to allocate these dollars across their academic programs and other services, such as student support and administration. As shown in the figure, three DPT programs (Long Beach, Northridge, and Sacramento) receive between $1,600 and $2,300 per FTES in state funding—about one–quarter to one–third of CSU’s average state funding per FTES. The two remaining programs—Fresno and San Diego—receive no state General Fund for direct program costs. All DPT programs report that state funding not allocated for program costs supports overhead and other costs at their campuses.

Start–Up Costs Typically Funded by Campus, School, or Department. Although four of the five campuses with independent DPT programs previously operated physical therapy master’s degree programs, all report having start–up costs related to their transition to doctoral programs. Start–up costs typically included the purchase of new equipment, totaling several hundred thousand dollars per program. Some campuses also reported moving their DPT programs into new or renovated facilities. Campuses covered these start–up costs using a combination of bond proceeds, Lottery funds, and general–purpose funds allocated by campus administration.

Students’ Educational Costs Approach $30,000 Annually. In addition to the $24,222 systemwide tuition, campuses set campus fees required of all students. Campus fees for DPT students vary from $1,223 at CSU Fresno to $1,752 at San Diego State University. Book and supply costs for the DPT programs range from about $1,300 to $2,900. Altogether, these annual costs range between $27,000 and $30,000 at the five campuses. These costs do not include living expenses such as housing, food, transportation, and personal expenses.

Most Students Receive Need–Based Financial Aid To Cover Education Costs. Because of the intensity of DPT programs (which operate for much of the day and much of the year), students generally are unable to maintain employment while enrolled. A large majority of students receives financial aid to support enrollment costs. Figure 9 provides information on the main sources of financial aid for students in 2013–14. About three–quarters of students received loans averaging $24,700 per student. (Many students received two or more loans of different types, including federal Stafford, Perkins, and Grad PLUS loans and private student loans.) More than 90 percent received a grant or scholarship, with awards averaging $7,500. A few students qualified for statutory fee waivers. Altogether, the typical financial aid package covered all direct education costs in the DPT program.

Figure 9

Most DPT Students Receive Campus Grants and Federal Loans

2013–14

|

|

Campus Grants and Scholarships

|

Federal Loans

|

Private Loans

|

Statutory Fee Waivers

|

Total

|

|

Student Financial Aid

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of students receiving aid

|

293

|

239

|

21

|

10

|

288

|

|

Percent of students receiving aid

|

91%

|

74%

|

7%

|

3%

|

89%

|

|

Total amount of aid

|

$2,200,700

|

$5,407,700

|

$216,500

|

$212,000

|

$8,333,800

|

|

Average amount of aid

|

7,500

|

23,900

|

10,300

|

21,200

|

28,900

|

|

Sample Financial Aid Packages

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Student with high grant

|

$28,600

|

$13,900

|

—

|

—

|

$42,500

|

|

Student with medium grant

|

8,100

|

20,500

|

—

|

—

|

28,600

|

|

Student with low grant

|

6,000

|

24,300

|

—

|

—

|

30,300

|

|

Student with fee waiver

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

$24,222

|

24,222

|

|

Student with no grant or waiver

|

—

|

28,500

|

—

|

—

|

28,500

|

For Students With Prior Debt, DPT Borrowing High. Based on two full years of data and preliminary information for the current academic year, average DPT student loan debt for the three–quarters of graduates who borrow is expected to be about $74,000. Given expected starting salaries for DPT graduates, this amount of debt is at the high end of what is considered a manageable student loan debt burden. (Experts recommend that cumulative debt not exceed a graduate’s starting annual salary.) Debt from these graduate programs, however, is in addition to any student loan debt DPT students may already have from their undergraduate or other graduate programs. Overall, average undergraduate debt for bachelor’s degree graduates at California’s public four–year universities is about $18,000. A student with combined undergraduate and graduate debt totaling more than $90,000 likely would exceed the recommended debt–to–income ratio.

CSU Complies With Programmatic Requirements. Chapter 425 required that independent CSU DPT programs be practice–focused. As evident from their curricula and clinical components, the programs are focused on preparing physical therapists to provide health care services, consistent with this requirement.

State’s Funding Approach Makes Compliance With Law’s Financial Provisions More Difficult To Ascertain. The law also requires, through various financial provisions, that CSU DPT programs not detract from CSU’s undergraduate mission. (For example, enrollment is to be funded from within CSU’s enrollment levels as agreed to in the annual budget act, and state funding is to be at the agreed–upon marginal cost rate for CSU students.) Some of these requirements, however, no longer are applicable to CSU. The state budget in recent years has not specified CSU enrollment levels or enrollment funding amounts against which the DPT programs could be compared. In addition, all CSU academic programs use general–purpose resources, including state and university funding and facilities. Because these resources otherwise could be used for undergraduate education, one cannot determine definitively how their use for DPT programs has affected undergraduate education. Nevertheless, graduate enrollment has not grown disproportionately to undergraduate enrollment at CSU since implementation of Chapter 425, and CSU DPT programs appear to be using less state funding than other CSU programs. The DPT programs even appear to be contributing funds to support departmental and campus overhead.

Review Raises Issues for Further Consideration. Beyond assessing compliance with statutory requirements, the joint review team took a comprehensive look at the new DPT programs. From this review, we identified four main issues for the Legislature’s and Governor’s further consideration. Specifically, the state may wish to reconsider its tuition policy for DPT programs, whether to limit further expansion of DPT programs, and whether to encourage CSU to extend the year–round model to other education programs. We also bring to policymakers’ attention that other professions are moving in the direction of increased education requirements, and we offer some options to consider when responding to future requests. We discuss each of these issues below.

CSU Tuition Rates for DPT Higher Than for Other CSU Graduate Programs. The CSU Trustees annually establish systemwide tuition rates. These include separate rates for undergraduate, certificate, and graduate programs through the master’s level, currently $2,736, $3,174, and $3,369 per semester, respectively. In addition, the Trustees set tuition rates for each of the three doctoral programs the CSU offers, currently $5,559 per semester for the Ed.D. program, $7,170 per semester for the DNP program, and $8,074 per semester for the DPT program.

CSU Physical Therapy Students Pay More Than Their Predecessors . . . Students in the CSU physical therapy master’s degree programs paid the graduate student tuition rate of $3,369 per semester in recent years. As discussed earlier, CSU no longer offers these programs, which do not meet the new accreditation requirements. Students wishing to become licensed physical therapists now must enroll in the doctoral program and pay the DPT tuition rate of 8,074 per semester. Over three years, the price difference for a full tuition–paying student otherwise earning a master’s in physical therapy from a CSU campus (including required pre–master’s courses and summer internships) and now earning a DPT from the same campus is more than $40,000. (A physical therapist with a pre–2015 master’s degree can earn a DPT through a “transition DPT” program, as described in the nearby box.)

Transition Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) programs, typically fewer than 24 semester units (or two terms of full–time study), are available only to licensed physical therapists (regardless of degree earned) who wish to earn a DPT degree for their own professional development or marketability. These programs provide students the same courses that California State University (CSU) added to its physical therapy curricula when converting its master’s degree programs to DPT programs: evidence–based practice, diagnostic imaging, pharmacology, medical screening, and diagnosis. Because they provide the additional doctoral–level content that was not included in physical therapy master’s degree programs, they help to illustrate the difference in costs between master’s and doctoral physical therapy education. In California, both Chapman University and Western University of Health Sciences offer a transition DPT program and charge students $10,000 or less for the entire program. Unlike CSU DPT programs, however, transition DPT programs serve practicing physical therapists.

. . . But Less Than They Would Pay in Most Private Programs. Total program charges for CSU DPT programs, including campus fees, over the three years range from $72,000 at Fresno (an 8–semester program) to $89,000 at Sacramento (a 9–semester program), whereas total charges for private programs range from $84,000 at Loma Linda University to $153,000 at University of Southern California.

Some Tuition Difference Warranted . . . We would expect somewhat higher costs per semester for CSU’s DPT programs than its master’s programs because of certain costs related to doctoral education. Accreditation standards under WASC require that institutions offering doctoral education provide a “doctoral culture” involving, among other things, increased allocation of faculty time for research and scholarship, enriched library offerings, and enhanced professional development (such as conference participation) for both faculty and doctoral students. Instead of teaching an average of 12 units per term and reserving 3 units for research, scholarship, and service, for example, doctoral faculty teach 9 units and have 6 units available for these other functions. As a result, CSU doctoral programs require a faculty–to–student ratio that is one–third higher than the ratio for undergraduate and other graduate programs. Because instructional faculty make up about 60 percent of program budgets, the one–third higher ratio could add about 20 percent to program costs. (The additional cost comes from the need to hire more faculty to accommodate faculty release time and the resulting higher faculty–to–student ratio.)

. . . But Identified Changes Do Not Fully Explain Size of Difference. The addition of new courses may add more semesters to the program, but would not necessarily increase instructional costs per semester. Moreover, the tuition difference (140 percent) is disproportional to the increase in cost related to faculty time allocation (20 percent). Campuses report a variety of reasons to explain the remaining difference. For example, they enhanced the quality of instruction, advising, and mentoring for physical therapy students, requiring increased faculty professional development. In addition, campuses report higher equipment costs related to the revised curriculum. Furthermore, any reduction in General Fund support campuses allocate to the DPT programs (compared with the physical therapy master’s programs) would account for a portion of the tuition difference.

Unclear Why UC Tuition Rates Would Be Suitable Benchmark. Chapter 425 capped tuition for independent CSU DPT programs at the amount charged for UC DPT programs. (Because the only such program at UC is the joint UCSF–SFSU program, this program provides the sole benchmark for CSU tuition levels.) Yet faculty at UC typically teach about two–thirds as many courses per year as their CSU doctoral faculty counterparts. They receive significantly more release time for scholarship and research to support UC’s mission as the state’s primary research university.

How Should Funding and Tuition Levels Be Set? The Legislature has chosen to cap CSU DPT tuition at a level that arguably is somewhat arbitrary, and CSU has charged tuition at just under the cap for each of its programs. Should the Legislature and Governor wish to reconsider this cap, they have several options. They could lower the tuition cap to an amount they determine better ties to expected costs. For example, they could cap tuition at two–thirds of the UC rate given the relative faculty course load. They could limit tuition to an amount they determine is affordable for students. They could treat CSU DPT programs similar to UC programs and set no limit on tuition levels, allowing campuses to charge market rates for these professional education programs.

Decision About How to Set Tuition Level Could Have Broader Implications. The decision as to whether CSU DPT tuition rates should be linked to costs or to what other universities charge and what students may be willing to pay could have implications for UC and CSU tuition rates for other programs. Currently, the universities implicitly link undergraduate and graduate academic tuition rates to a share of education cost (with student tuition covering some share of cost and state funding covering the remainder). In contrast, the universities link some tuition rates (for example, UC’s professional school rates) to rates charged by comparison institutions. Neither the universities nor the state has a standard policy specifying how tuition levels are to be set. Setting a new tuition policy for CSU DPT programs might be seen as setting a precedent for other programs’ tuition levels.

At this time, new DPT programs do not appear warranted, as the current supply of new physical therapists in California more than meets current demand, and CSU is not indicating an intention to create additional DPT programs in the coming years.

Should State Place Limits on Further Expansion of DPT Programs? Prior to 2011, the state had a central mechanism, through the California Postsecondary Education Commission, to assess the need for new academic programs. State review examined student demand, societal needs, existing capacity in the state, and program costs. Following the closure of the commission in 2011, however, the segments have broader discretion to create new academic programs. The segments’ internal approval processes for new academic programs include review by the campus requesting the program, the system offices, the governing boards, and WASC, typically considering some of the same factors as the commission reviewed. If policymakers are concerned about the lack of external review for new programs, they could require that the segments submit new program proposals to the Legislature and Governor for approval, with justification including analysis of regional supply and demand. Policymakers then could consider these submissions in the context of other state priorities and available funding.

Decision About Approval Process Also Could Have Broader Implications. The decision as to whether CSU should be allowed to expand DPT programs at its discretion or be subject to state review and approval could have implications for other program expansions that UC and CSU desire. That is, the state may want to apply a new state review and approval process to all UC’s and CSU’s desired program expansions.

Year–Round Schedule for DPT Programs Has Multiple Benefits. The year–round schedule for CSU DPT programs permits students to complete nine semesters in 36 months (3 years) instead of 54 months (4.5 years). (Similarly, the CSU doctoral programs in nursing practice follow a year–round schedule, permitting students to complete five semesters in 20 months instead of 30 months.) By DPT students finishing up sooner than otherwise, campuses are able to expand access to new students. Additionally, the year–round schedule helps programs accommodate clinical placements for students. (Because the programs rely on a limited number of employers to host students for clinical experiences, spreading these placements throughout the year, instead of in summer only as a regular academic calendar would require, more fully utilizes these resources and reduces competition for clinical slots in the summer.) CSU’s cohort model for DPT programs also appears to have the effect of expanding access to new students by minimizing excess–unit taking, as all students progress through the same curriculum and are effectively guaranteed access to required courses.

CSU Could Accommodate More Students if It Operated Year–Round. Currently most CSU students enroll only during the fall and spring terms. During the summer term, many campus facilities are underutilized or closed. Year–round schedules would more fully utilize facilities, allowing the university to accommodate more students (given sufficient funding), thereby reducing or eliminating bottlenecks in courses requiring laboratories, studios, specialized equipment, or other scarce capital resources. The Legislature and Governor may wish to consider encouraging CSU to build on the success of the year–round model in its doctoral programs by expanding this model to other academic programs. Similarly, the state may wish to consider encouraging CSU to use its cohort model more frequently when it is determined to be advantageous for students.

Although CSU system leadership is not currently seeking authority to expand doctoral education at the CSU, professional associations and accreditors in fields other than physical therapy have expressed interest in raising educational standards for their professions and some campus leaders have expressed interest in offering more doctoral programs. Given these pressures, the Legislature and Governor can expect additional requests to expand CSU’s independent doctoral authority in the future. As highlighted at the end of this section, the state has a few options for responding to these requests.

Other Professions Moving Toward Higher Degree Requirements. The accreditor for nurse–anesthetist education programs has announced that beginning with students enrolling in 2022, a doctorate will become the entry–level degree in the profession. Professional associations and accreditors for nurse practitioners, speech and language pathologists, and occupational therapists likewise are discussing what the minimum entry–level degree should be in those professions and could increase accreditation requirements in the near future. Likewise, changes in the labor market may make doctoral degrees in certain professions attractive. (As noted earlier, the Legislature authorized CSU to offer the Ed.D. and DNP in direct response to employment demand.) In addition, the CSU’s existing independent doctoral programs clearly are a source of pride for participating campuses, and some campus leaders have expressed interest in expanding their doctoral degree offerings.

Higher Degree Requirements Increase Public and Societal Costs. As it considers future requests to expand CSU’s doctoral authority, ideally the state will want to weigh the advantages of new doctoral programs against the higher costs to deliver doctoral education and increased financial barriers for individuals to enter a profession. It currently relies partly on professional associations, accreditors, and educational institutions to determine the level of education required for a profession and how that education should be delivered. Relying on these parties could be problematic, however, because more advanced educational requirements arguably could be self–serving for them—doctoral degrees can provide increased prestige for professionals and raise the profile of a profession. Professional associations and educational institutions may place more value on these benefits, while policymakers may be more concerned about increased costs to students and taxpayers.

Four Options for State To Respond. State policymakers’ options for influencing and responding to professional movements to elevate academic requirements are limited, though four basic options exist:

- Provide Alternative Routes to Professional Licensure. The state could require that professional license applicants meet minimum standards, which applicants could demonstrate by passing a test, graduating from a professional education program (which may not be nationally accredited), or studying in another context. For example, to meet the requirements for admission to the State Bar of California, students may complete four years of study in a law office or judge’s chamber instead of earning a law degree from an accredited law school.

- Establish State Accreditation Process. Policymakers could decide to create a state process so that the state no longer would need to rely on national accreditation for professional programs. Programmatic accreditation typically is not performed by state governments on a large scale, however, and could be costly and inefficient to replicate. (As an exception to this general rule, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing accredits all teacher preparation programs in the state.) These programs likely would not be attractive to students because students may face increased difficulty accessing federal financial aid and obtaining licensure in other states that require graduation from a nationally accredited physical therapy education program.

- Expand CSU Independent Doctoral Authority. If the state continued to rely on professional accreditation, it could authorize more CSU doctoral degrees as accreditation standards for professions increase.

- Rely on UC and Private Institutions. The state could decline to authorize additional CSU doctoral degrees and instead leave it to UC and other doctoral institutions to meet the demand for new doctoral graduates.

Assembly Bill No. 2382

CHAPTER 425

An act to add Article 4.7 (commencing with Section 66042) to Chapter 2 of Part 40 of Division 5 of Title 3 of, and to repeal Section 66042.3 of, of the Education Code, relating to public postsecondary education.

[Approved by Governor September 28, 2010. Filed with Secretary of State September 28, 2010.]

The people of the State of California do enact as follows:

SECTION 1. Article 4.7 (commencing with Section 66042) is added to Chapter 2 of Part 40 of Division 5 of Title 3 of the Education Code, to read:

Article 4.7. Doctoral Programs in Physical Therapy

66042. (a) The Legislature finds and declares both of the following:

(1) Since its adoption in 1960, the Master Plan for Higher Education has served to create the largest and most distinguished higher education system in the nation. A key component of the Master Plan for Higher Education is the differentiation of mission and function, whereby doctoral and identified professional programs are limited to the University of California, with the provision that the California State University can provide doctoral education in joint doctoral programs with the University of California and independent California colleges and universities. The differentiation of function has allowed California to provide universal access to postsecondary education while preserving quality.

(2) Because of the need to prepare and educate increased numbers of physical therapists, the State of California is granting the California State University authority to offer the Doctor of Physical Therapy degree as an exception to the differentiation of function in graduate education that assigns sole authority among the California higher education segments to the University of California for awarding doctoral degrees independently. This exception to the Master Plan for Higher Education recognizes the distinctive strengths and respective missions of the California State University and the University of California.

(b) Pursuant to subdivision (a), and notwithstanding Section 66010.4, in order to meet specific physical therapy education needs in California, the California State University may award the Doctor of Physical Therapy (D.P.T.) degree. The authority to award degrees granted by this article is limited to the discipline of physical therapy. The Doctor of Physical Therapy degree offered by the California State University shall be distinguished from doctoral degree programs at the University of California.

66042.1. In implementing Section 66042, the California State University shall comply with all of the following requirements:

(a) Funding on a per full–time equivalent student (FTES) basis for each new student in these degree programs shall be from within the California State University’s enrollment growth levels as agreed to in the annual Budget Act. Enrollments in these programs shall not alter the California State University’s ratio of graduate instruction to total enrollment, and shall not diminish enrollment growth in university undergraduate programs. Funding provided from the state for each FTES shall be at the agreed–upon marginal cost calculation that the California State University receives.

(b) The Doctor of Physical Therapy (D.P.T.) degree offered by the California State University shall be focused on preparing physical therapists to provide health care services, and shall be consistent with meeting the requirements of the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE).

(c) Nothing in this article shall be construed to limit or preclude the California Postsecondary Education Commission from exercising its authority under Chapter 11 (commencing with Section 66900) to review, evaluate, and make recommendations relating to any and all programs established under this article.

(d) Each student in the programs authorized by this article shall be charged fees no higher than the rate charged for students in state–supported doctoral degree programs in physical therapy at the University of California, including joint D.P.T. programs of the California State University and the University of California.

(e) The California State University shall provide any startup funding needed for the programs authorized by this article from within existing budgets for academic programs support, without diminishing the quality of program support offered to California State University undergraduate programs. Funding of these programs shall not result in reduced undergraduate enrollments at the California State University.

66042.3. (a) The California State University, the Department of Finance, and the Legislative Analyst’s Office shall jointly conduct a statewide evaluation of the new programs implemented under this article. The results of the evaluation shall be reported, in writing, to the Legislature and the Governor on or before January 1, 2015. The evaluation required by this section shall consider all of the following:

(1) The number of new doctoral programs in physical therapy implemented, including information identifying the number of new programs, applicants, admissions, enrollments, and degree recipients.

(2) The extent to which the programs established under this article are fulfilling identified needs for physical therapists, including statewide supply and demand data that considers capacity at the University of California and in California’s independent colleges and universities.

(3) Information on the place of employment of students and the subsequent job placement of graduates.

(4) Program costs and the fund sources that were used to finance these programs, including a calculation of cost per degree awarded.

(5) The costs of the programs to students, the amount of financial aid offered, and student debt levels of graduates of the programs.

(6) The extent to which the programs established under this article are in compliance with the requirements of this article.

(b) (1) A report to be submitted pursuant to subdivision (a) shall be submitted in compliance with Section 9795 of the Government Code.

(2) Pursuant to Section 10231.5 of the Government Code, this section is repealed on January 1, 2019.