What Is Unclaimed Property? When the owner of personal property, such as a checking account, has no contact with their financial institution for a specified period (in most cases three years), that property is transferred to the State Controller’s Office (SCO). The state “escheats”—or takes temporary title in—these properties, maintaining an indefinite obligation to reunite the property with the owner. These “unclaimed” properties include bank accounts, insurance policies, stocks and other securities, and various other types of personal property.

$7.2 Billion in Unclaimed Property. Since the 1950s, the state has accumulated 28.4 million unclaimed properties totaling $7.2 billion. Much of this total, however, will never be claimed for various reasons, including poor information reported to the state, outdated owner contact information, and the difficulty inherent in reuniting property with the heirs of deceased owners. Given these and other constraints, the state estimates it will reunite less than $1 billion with owners.

SCO Faces Constraints in Reuniting More Property. Over the past 20 years, the state has reunited about $4 with owners for every $10 it escheats on average. This reunification rate is better than in decades past, but several factors inhibit SCO’s ability to reunite more property with owners. In particular, because property not reunited with owners becomes state General Fund revenue, the unclaimed property law creates an incentive for the state to reunite less property with owners. Now generating over $400 million in annual revenue, unclaimed property is the state General Fund’s fifth–largest revenue source. This has created tension between two opposing program identities—unclaimed property as a consumer protection program and as a source of General Fund revenue. The unclaimed property program also suffers from a lack of public awareness. Despite these constraints, SCO has made strides in recent years, including a streamlined Internet claims process.

Recommend Performance Measures for Program. The Legislature could clarify the goals of the unclaimed property program by establishing clear performance measures, or targets, for the program. We recommend an increased focus by the state on reuniting unclaimed property with owners. The more that the Legislature targets a higher level of property reunification with owners, the more this will tend to decrease state General Fund revenues in the future. We offer various options that could improve the program’s success in reuniting unclaimed property with owners. Among these options are a simpler and more efficient property claims process and new outreach efforts to better inform residents and businesses about the program. While SCO may be able to implement a few options administratively, others would require changes in law or additional resources.

California law has long required banks, insurance companies, and many other types of entities (known as holders) to transfer to SCO personal property considered abandoned by owners. These “unclaimed” properties are bank accounts, insurance policies, stocks and other securities, and many other types of properties for which owners have had no contact with holders for a specified period of time, in most cases three years. Real property, such as houses and land, and certain types of personal property, such as automobiles, are not covered by the state’s Unclaimed Property Law (UPL). The state “escheats,” or takes temporary title in, these properties and maintains an indefinite obligation to reunite the property with owners, should they come forth and make a claim. (The state also escheats the value of estates belonging to deceased persons without heirs, but these properties are not the focus of this report. In addition, the California Government Code outlines procedures used by local governments for unclaimed funds in their possession, but this report focuses on properties in the state’s possession.) The box below explains terms used in the unclaimed property program.

This report includes a number of terms used in unclaimed property policy. Below, we explain these terms as they relate to California’s program.

- Unclaimed Property: Bank accounts, amounts owed under insurance policies, securities, sums payable on checks or other written instruments, safe deposit box contents, and other assets that have remained dormant for a specified period of time.

- Dormancy Period: The unclaimed property law provides for the escheat of properties for which owners have had no contact with holders for a specified period of time known as the dormancy period.

- Holder: Any individual, business, or local government in possession of unclaimed property. For example, a bank is the holder of dormant checking accounts.

- Owner: Any individual, business, or local government having a legal interest in unclaimed property. For example, an individual that visits the State Controller’s website and identifies a dormant checking account belonging to them is the owner of that account. The heir(s) of a deceased owner of unclaimed property is also considered an owner.

- Escheat: The transfer of title in property to the state. As used in this report, the term escheat generally refers to a temporary transfer of title wherein the state acts as a custodian—maintaining an indefinite obligation to reunite the property with the owner.

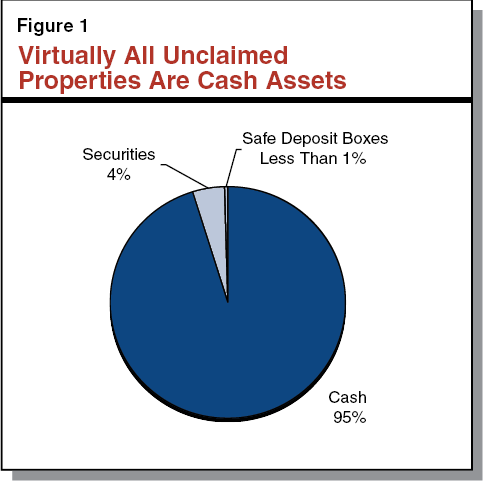

Nearly All Unclaimed Properties Are Cash Assets. As shown in Figure 1, 95 percent of unclaimed properties are cash assets—for example, checking accounts, savings accounts, the cash value of gift certificates with expiration dates, the value of stocks that the state has liquidated, and other cash properties. Unclaimed property also includes securities that have not yet been liquidated to cash (4 percent), as well as tangible items, such as the contents of safe deposit boxes (under 1 percent). (In general, dollar figures referenced in this report do not account for items without a cash value.)

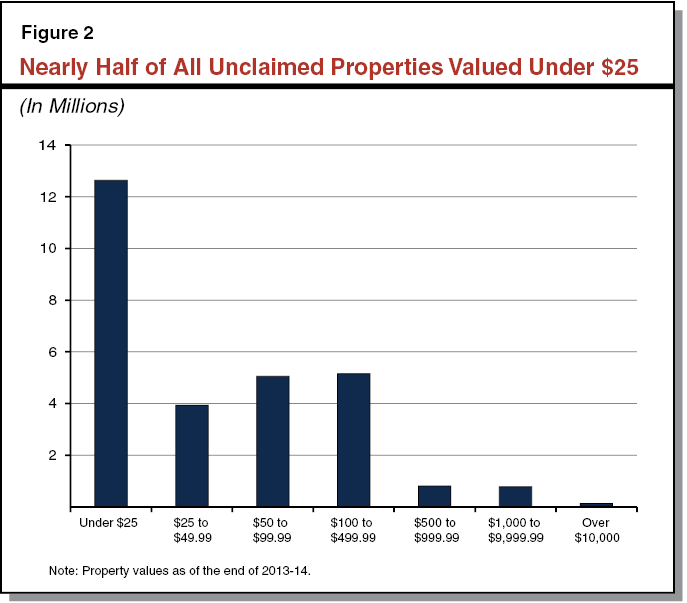

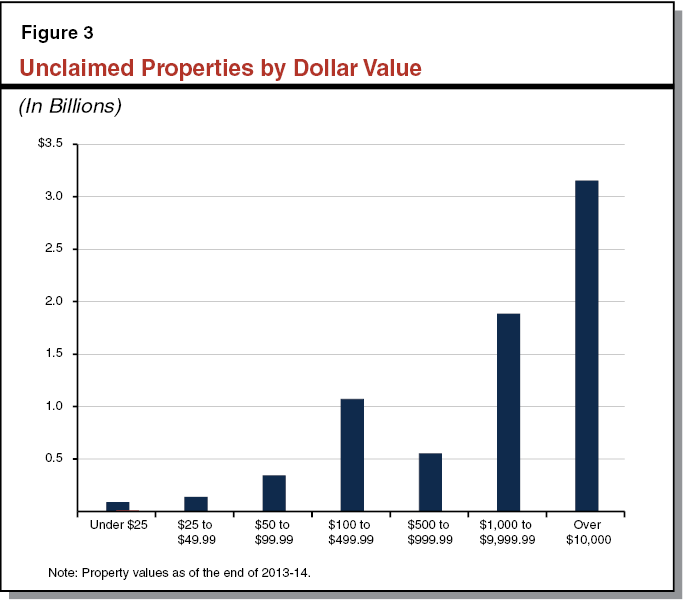

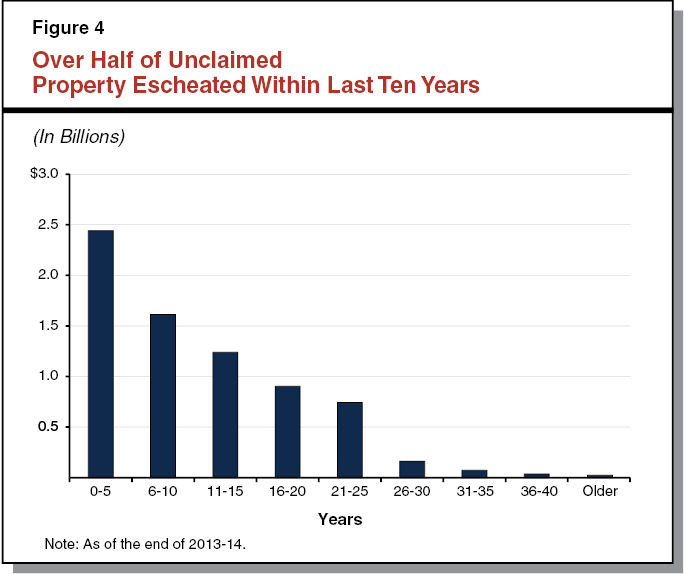

How Much Are We Talking About? As of the end of 2013–14, the state had 28.4 million escheated properties that had not been claimed by owners. Collectively, these properties are valued at $7.2 billion. As shown in Figure 2, most properties have relatively low values. Nearly half of unclaimed properties are valued under $25 and over 90 percent are less than $500. In dollar terms, over two–thirds of the total is comprised of properties valued over $1,000, as shown in Figure 3. Most unclaimed property has been escheated within the past ten years, as shown in Figure 4.

Modern Laws Derived From Ancient English Common Law. There were two different types of escheats in English common law. The first type concerned landowners who died without heirs. Because the monarch was the original proprietor of all lands in the kingdom, it was held that any property for which no known heir could take title would revert to the crown. The second type of escheat affected individuals who had committed crimes. When a property owner committed a felony or treason, it was held that such individual had forfeited their rights as a landowner and the land would escheat to the monarch. California escheat laws relate most closely to the first type of escheat, and govern estates with no known heirs as well as property that has remained dormant for a specified period of time.

California Escheat Laws Date to 19th Century. Since at least the 1870s, California laws have provided for the escheat of properties belonging to deceased persons without known heirs. In the 1890s, escheat laws were expanded to require banks to (1) report to the state concerning dormant accounts and (2) post notices about those accounts in newspapers. Chapter 35, Statutes of 1897 (SB 178, Stratton)—the first California statute providing for the escheat of abandoned property—applied to banks in the process of dissolution.

California Begins Escheating Dormant Properties in 1910s. Whereas the requirements of Chapter 35 were limited to banks in the process of dissolution, escheat laws were changed in the 1910s to require the escheat of dormant accounts at active banks. Three laws in the 1910s—Chapter 104, Statutes of 1913 (AB 1137, Benedict), Chapter 84, Statutes of 1915 (SB 671, Hans), and Chapter 555, Statutes of 1915 (SB 1123, Kehoe)—expanded escheat laws to cover accounts with any bank that remained dormant for 20 years.

The laws of this era created a process for the state to permanently escheat the property. (Prior statutes had limited the state to a custodial role—maintaining properties indefinitely until they were claimed by owners.) Specifically, the Attorney General would commence an action in the superior court and publish a notice in a newspaper for four weeks to allow interested parties an opportunity to claim the accounts in question. If the owner did not appear and make a claim, the state escheated the property. Thereafter, statute provided an additional five–year period for persons not a party to the original escheat proceeding to file a claim. After the additional five years had run, the owner’s rights were forever barred, meaning that the title in the property permanently escheated to the state. (In 1923, these laws were held by the U.S. Supreme Court to satisfy due process requirements under the U.S. and California Constitutions.)

State Escheat Laws Expanded in Mid–20th Century. In 1954, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (now known as the Uniform Law Commission) drafted model legislation to protect consumers from banks and other entities that tended to maintain abandoned assets for their own use instead of tracking down the rightful owners. Between 1946 and 1961, at least 20 states expanded their escheat laws, with half adopting the Uniform Law Commission’s model legislation. Today, every state and the District of Columbia have unclaimed property laws on the books. According to the National Association of Unclaimed Property Administrators website, the total amount of unclaimed property nationwide is $41.7 billion.

California Adopts UPL in 1959. Whereas earlier escheat laws applied only to bank accounts, the UPL (initially passed as Chapter 1809, Statutes of 1959 [AB 16, Miller]) expanded coverage to insurance properties, securities, travelers checks, and safe deposit boxes. The goals of the law were twofold. First, the law sought to reunite unclaimed property with its rightful owner. Second, the law gave the state rather than the holder the benefit of the use of properties that cannot be reunited. Unlike earlier escheat laws, the UPL does not permanently escheat unclaimed property. Rather, the state returned to a custodial role—maintaining an indefinite obligation to reunite property with owners.

Legal Issues in 2000s. The UPL and its predecessor laws have a rich case law history that informs the boundaries of today’s program. In the 2000s, the state faced challenges to the constitutionality of certain aspects of the unclaimed property program. Most notably, cases dealt with whether (1) the state’s failure to pay interest on property was an unconstitutional taking and (2) the program’s notice procedures failed to satisfy the due process clauses of the California and U.S. Constitutions. In the box below, we outline our understanding of the current case law in these two areas.

State Not Required to Pay Interest. In 2003, the state discontinued its policy of paying interest on the value of unclaimed property once the property was in the possession of the state. In Morris v. Chiang (2008) and Suever v. Connell (2009), state and federal courts ruled that the state is not required to pay interest. Under state law, once unclaimed property is sent to the state, the title in that property is vested in the state until the owner makes a claim. The courts reasoned that this transfer in title—albeit temporary—means that the property belongs to the state during this period. Because owners do not have title in the property while the property is in the state’s custody, the courts held the state’s failure to pay interest on that property cannot be an unconstitutional taking. (In contrast, a 2013 federal ruling held that Indiana’s failure to pay interest was an unconstitutional taking on the basis that title does not vest in that state. Indiana since amended their statute to pay interest.)

Program Enjoined in 2007. In Taylor v. Westly (2007), a federal circuit court ruled that state efforts to notify owners were unconstitutional in part because procedures at the time failed to notify many property owners prior to escheat. In July 2007, the court issued an injunction that prevented the state from escheating property until the notice provisions were amended to meet due process requirements.

Senate Bill 86 Made Changes Necessary to Lift Injunction. As part of the 2007–08 budget package, Chapter 179, Statutes of 2007, (SB 86, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), responded to the injunction, making changes necessary to restore the state’s authority to escheat property. Specifically, SB 86 amended the Unclaimed Property Law to require the State Controller’s Office (SCO) to mail a notice to all owners of property valued $50 or more before the state escheats the property (provided that the holder report contains an address for the property). This allows owners to reestablish contact and maintain their assets with holders before their property is escheated by the state. Senate Bill 86 also requires SCO to wait 18 months before liquidating securities or auctioning or destroying tangible property, such as the contents of safe deposit boxes. (The waiting period for destroying property was later extended to seven years.) The federal district court found these changes to satisfy due process requirements and lifted the injunction in October 2007.

In this section of the report, we first explain the process by which (1) holders report unclaimed property, (2) the property is escheated to the state, and (3) owners submit claims for their property. We then describe how unclaimed property relates to the state budget.

Figure 5 depicts how unclaimed property is escheated to the state and how it is later claimed by owners.

Jurisdiction of UPL. The state escheats most types of property when the owner’s last known address is in the state. (The contents of safe deposit boxes are escheated if the property itself is located in the state.) In cases where no known address is kept on record with the holder—in many cases, sums payable on a cashier’s check or money order—or if the owner is a foreign nation, the state escheats property if the holder is located in the state.

Property Subject to Escheat if Dormant for Specified Period. In general, when an owner has had no contact with a holder for a period of time (and efforts to contact the owner have been unsuccessful), property covered by the UPL escheats to the state. Figure 6 shows unclaimed property types grouped by dormancy period. For example, a checking account escheats to the state when no deposits or withdrawals have been made on the account and the holder has had no other contact with the owner for three years. Over time, the dormancy period for most types of property has been shortened. For example, the dormancy period for checking accounts was lowered from 15 years to 7 years in 1976, 5 years in 1988, and 3 years in 1990.

Figure 6

Dormancy Period Is Three Years for Most Property Types

|

One Year

|

|

Wages and salaries, such as uncashed paychecks

|

|

Three Years

|

|

Checking and savings accounts

|

|

Contents of safe deposit boxes

|

|

Matured CDs and other time deposits

|

|

Sums payable on checksa

|

|

Escrow accounts

|

|

Individual retirement accounts

|

|

Stocks, bonds, dividends, and mutual funds

|

|

Amounts owed under life insurance policies and annuities

|

|

Fiduciary property

|

|

Personal property not explicitly covered by Unclaimed Property Lawb

|

|

Distributions from employee benefit plans

|

|

Seven Years

|

|

Sums payable on money orders

|

|

Fifteen Years

|

|

Sums payable on traveler’s checks

|

Holders Must Notify Owners of Impending Escheat. The UPL requires holders to notify owners their property will escheat to the state if they do not contact the holder. (Holders are only required to conduct this due diligence if they have an address for the owner in their records.) Holders must notify owners between six months and one year prior to the reporting deadlines described below. The UPL requires notices to contain certain specific information, including details about the property, a statement that the property will escheat to the state, and a form that owners can use to contact the holder to keep the property active. The UPL authorizes holders to recover a fee from most types of property, not to exceed the lesser of the cost of sending the notice or $2.

Beginning in 1977, holders were required to perform this due diligence for all properties, regardless of value. The UPL was amended in 1982 to exempt properties under $25 from the due diligence requirements, and this threshold was increased to $50 in 1997. (In the case of safe deposit box contents, holders must notify owners regardless of property value.)

Holders of Unclaimed Property Report to SCO Annually. The UPL requires holders to file an annual report with SCO before November 1. The holder reports detail properties that have already exceeded the dormancy period. (In the case of insurance properties, the report is filed by May 1 for properties that will escheat on December 31.) In 2012–13, SCO received reports from about 37,000 holders. For properties over $25, holders generally must report the name, last known address, and other identifying information about the owner, if available. Holders may report items valued under $25 without identifying information about the owner. (This is referred to as aggregate reporting.) In its instructions for holders, SCO strongly discourages the filing of aggregate reports.

SCO Also Contacts Some Owners Prior to Escheat. The UPL requires SCO to notify owners within 165 days of the holder report that their property will escheat to the state unless they contact the holder. These notifications are usually sent by April 15 of the following year for noninsurance properties and October 13 of the same year for insurance properties. Specifically, the UPL requires SCO to send these pre–escheat notices to owners of properties valued over $50 and for whom holders have listed an address in their report to SCO. If the record includes a social security number, SCO cross checks Franchise Tax Board (FTB) records for a more recent owner address. If an owner contacts the holder prior to the date by which property escheats to the state, that owner’s property is considered active and remains with the holder. In 2012–13, SCO sent 1.1 million pre–escheat notices to owners.

Property Escheats to State About Seven Months After Holder Report. If efforts by holders and SCO to prevent escheat have failed, holders must deliver property to SCO between June 1 and June 15 (between December 1 and December 15 for insurance properties). The SCO arranges for holders to deliver the contents of safe deposit boxes within one year of the holder report. SCO can refuse to take possession of tangible property if they determine it is not in the interest of the state to take custody. If the total payment is over $20,000, the UPL requires holders to pay cash by electronic funds transfer (EFT). If an owner contacts a holder after the property escheats to the state, the holder may compensate the owner for the value of the property and submit a claim to SCO for reimbursement.

Holders May Incur Penalties for Failing to Report or Deliver Properties. Under current law, holders may be charged a penalty of 12 percent per year for failing to report and/or deliver property to SCO. Chapter 522, Statutes of 2009 (AB 1291, Niello), capped the penalty at $10,000 for holders who file their reports on time but fail to include all properties subject to the UPL. Holders may also incur relatively small penalties for not remitting properties valued over $20,000 by EFT. Between 2009–10 and 2012–13, interest assessments relating to the unclaimed property program averaged about $17 million per year.

SCO Publishes Newspaper Notices. The UPL requires SCO to publish a notice in a newspaper of general circulation within one year of escheat. Whereas decades ago notices specified apparent owners by name, modern notices do not identify individual owners or properties. Rather, they direct the public at large to search SCO’s public database—www.claimit.ca.gov—or call the unclaimed property call center to determine whether they have unclaimed property.

Annual Budget Bill Limits Spending on Outreach. Provisional language routinely included in the annual budget bill prohibits SCO from spending more than $50,000 per year to inform the public about the unclaimed property program. (The 2015–16 Governor’s Budget proposes to increase this limit to $60,000.) The language applies only to general owner outreach, and places no specific limit on the amount SCO can spend to send pre–escheat notices to owners or notify holders about the unclaimed property program. In 2014, SCO ran advertisements in 50 physical newspapers in California, reaching a circulation of about 4.5 million. SCO spent about $38,000 on these advertisements.

SCO Must Consider Claims Within 180 Days. The UPL requires SCO to consider all claims within 180 days. The majority of paper claims require months to process, but relatively simple paper claims can be processed in 30 to 45 days. Claims submitted via SCO’s Internet eClaim feature are processed within 14 days, as discussed below. In 2012–13, SCO received and processed about 175,000 claims.

Documentation Requirements for Paper Claims Vary by Property Type. Figure 7 displays documentation requirements for individuals submitting paper claims. Individuals must submit all of the documentation shown in the figure and in some cases SCO requires additional documentation. For example, heirs claiming property belonging to deceased persons must provide a copy of a final death certificate. In the case of businesses filing claims, SCO requires similar information as shown in Figure 7, but instead of verifying a social security number, the claimant must demonstrate their relationship to the company and verify the company’s Federal Employer Identification Number (FEIN). In addition, the company must be in good standing with the Secretary of State’s office and FTB. (Requirements for governments are similar to those of businesses.) SCO requires claimants to certify under penalty of perjury that they are the rightful owner of the property being claimed. The UPL specifies a process by which claimants may appeal a decision.

Figure 7

General Documentation Requirements for Individuals Filing Paper Claimsa

|

Individuals Must Submit All of the Following:

|

|

|

- Proof of identification.c

|

- Proof of social security number.d

|

- Proof of current mailing address.e

|

- Proof of address shown in holder record, if different from current mailing address.e

|

- Proof of ownership, if holder records do not contain an address.f

|

- If property is a negotiable instrument (such as a check, gift card, or money order), a copy of the instrument.

|

eClaim Process Shortens Processing Period for Most Properties. If a property is valued under $1,000 and belongs to a single owner, owners can opt to submit a claim through SCO’s website rather than mailing a paper claim. eClaim requires less documentation—claimants need only fill out an online form. In addition, SCO can consider eClaims in minutes compared to months for the paper process. SCO touts that properties claimed through the website can be reunited with owners within 14 days. Over three–quarters of the properties in the program—representing about one–third of the total dollar value of unclaimed property—are eligible for the eClaim process.

SCO Stores Tangible Items in Two Facilities. In 2012–13, SCO processed around 5,700 safe deposit box properties. SCO stores these properties according to their value. Valuable properties are stored at the State Treasurer’s Office, while valueless properties are stored at a third–party storage facility. SCO spent about $20,000 in 2013–14 storing around 4,500 cubic feet of tangible items, the physical volume of which is illustrated in Figure 8.

SCO Discontinued Auctions of Valuable Properties. The UPL requires the Controller to sell all valuable tangible property to the highest bidder at public sale, but not before 18 months after the holder reporting deadline. The UPL allows the Controller to conduct such auctions in the most favorable market, including on Internet websites. The last public auction was to be held in May 2006, but was halted due to the injunction arising from Taylor v. Westly. Auctions could have resumed in October 2007, but SCO has since maintained a policy not to auction unclaimed property.

SCO Chooses Not to Destroy Valueless Properties. Prior to SB 86, SCO was authorized to destroy property without commercial value at any time. Senate Bill 86 required SCO to retain such property for at least 18 months beyond the holder reporting deadline. (This period was extended to seven years by Chapter 305, Statutes of 2011 [SB 495, Fuller].) SCO has retained all properties without commercial value since 2007.

Securities Required to Be Sold Within 20 Months After Holder Report. The UPL requires SCO to sell securities between 18 months and 20 months after the holder reporting deadline. If owners claim the security property after sale, they receive the cash proceeds of the sale no matter if the security increased or decreased in value while in possession of the state. Maintaining security properties is relatively labor intensive. Prior to sale, SCO must ensure these properties are up to date, reflecting stock splits, mergers, and other corporate actions. Otherwise, SCO may be selling a security at the wrong amount. SCO reports, however, that 99 percent of corporate actions are current when the shares escheat to the state. (Private firms typically conduct these activities on behalf of owners prior to escheat.) In recent years, the significant workload associated with security sales has exceeded SCO’s staffing for processing these properties, resulting in a large backlog of shares not being sold by the 20–month statutory deadline. The 2014–15 Budget Act gave SCO 23.1 three–year limited term positions in part to address the securities backlog.

State Stopped Paying Interest in 2003. Under current law, properties do not accrue interest while in the state’s possession. (Securities, however, fluctuate in value while in stock form.) Historically, the state has had different policies concerning owner interest, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9

State Law Providing Interest to Owners Has Varied

|

Chapter 1809, Statutes of 1959 (AB 16, Miller)

|

|

No interest provided to owners.

|

|

Chapter 1151, Statutes of 1976 (AB 3547, Burke)

|

|

Lesser of: 5 percent or the rate the property earned while in possession of the holder, compounded annually.

|

|

Chapter 815, Statutes of 1978 (AB 3042, Agnos)

|

|

Lesser of: 5 percent compounded annually or the state PMIA rate.

|

|

Chapter 1124, Statutes of 2002 (AB 3000, Committee on Budget)

|

|

Lesser of: 5 percent or the bond equivalent rate of 13–week U.S. Treasury bills, not compounded.

|

|

Chapter 228, Statutes of 2003 (AB 1756, Committee on Budget)

|

|

Eliminated interest payments to owners.

|

Owners Have Not Been Charged Fees Since 1977. The 1959 law required SCO to charge a fee of the greater of $10 or one percent of the amount of the claim. Chapter 49, Statutes of 1976 (AB 1872, Boatwright), eliminated that fee.

Administrative Costs. Prior to 2008–09, administrative costs for the unclaimed property program were funded from the General Fund—the state’s main operating account. Starting in 2008–09, these costs have been paid for from the Unclaimed Property Fund (UPF), the state account into which cash properties are deposited upon escheat.

Private “Investigators” Also Contact Apparent Owners. The UPL allows individuals or businesses—known as investigators—to assist owners in recovering their unclaimed property. Investigators may charge a fee of up to 10 percent of the value of the claim. Depending on the nature of the agreement between parties, SCO either sends two separate payments or sends the entire property value to the owner with a letter noting that the owner must pay the investigator. From 2008–09 through 2013–14, an average of about 23,000 properties were returned by investigators each year. The average annual dollar value returned by investigators during the period was nearly $19 million, not including the value of unliquidated securities. This represents roughly 10 percent of the dollar value returned to owners over the period.

SCO Conducted Holder Amnesty Program in Early 2000s. Chapter 267, Statutes of 2000 (AB 1888, Dutra), authorized a one–year amnesty program beginning in January 2001 that allowed holders to come into compliance with UPL without incurring fees. (The program was extended for a second year—through December 2002—by Chapter 22, Statutes of 2002 [AB 227, Dutra].) SCO conducted outreach efforts during the amnesty program, including advertisements in national newspapers. The program resulted in 4,927 holder reports detailing 145,903 properties valued at $196 million (in nominal terms)—$113 million in cash and $83 million in securities. A total of 1,567 of these reports were made by holders that had never previously filed. By comparison, a total of about $780 million (also in nominal terms) was escheated by the state in two fiscal years around this time—2000–01 and 2001–02.

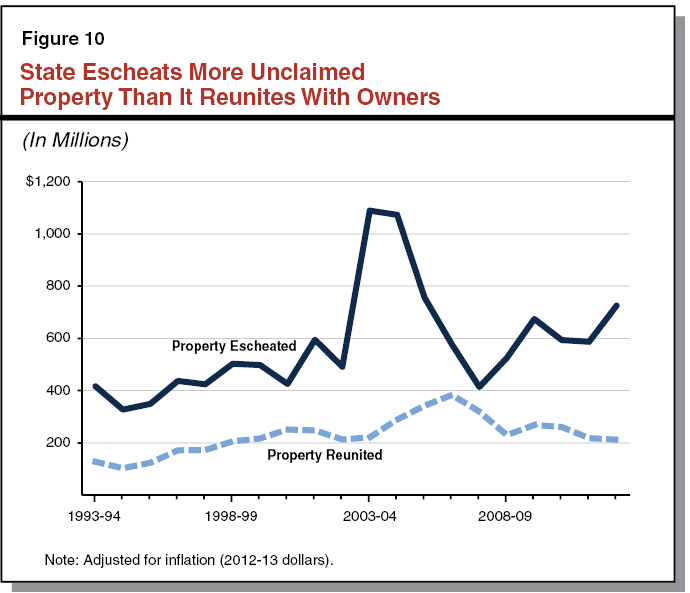

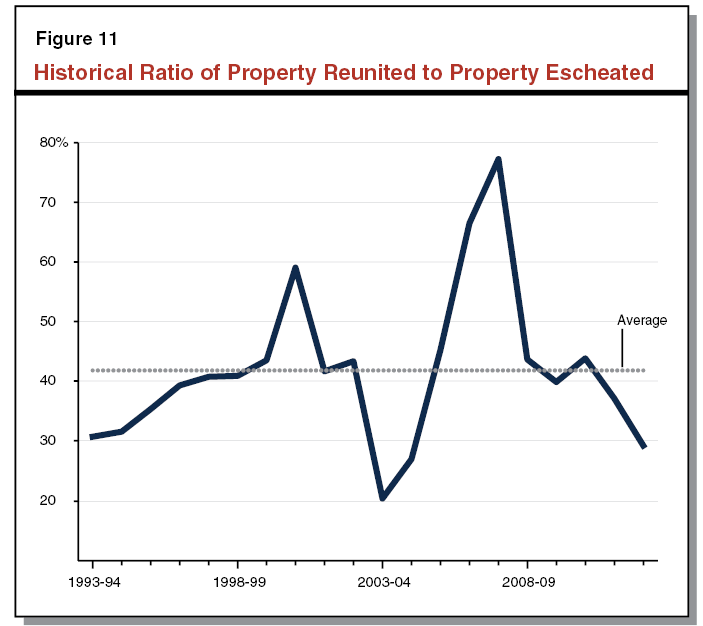

Amount Escheated Always Exceeds Amount Reunited With Owners. Figure 10 shows the value of property escheated and reunited with owners over a recent 20–year period. As shown in the figure, escheats always exceed property reunited with owners. Over this same period, the average amount of property that the state reunited with owners was about 40 percent, as shown in Figure 11. The large variance during the mid–2000s results from a large spike in escheated properties in 2003–04 and 2004–05—much of which was due to a decision to accelerate the schedule for selling securities—and resulting claims that lagged over the ensuing few years. The reunification rate over the last two decades is apparently much higher than in the past. According to a 1990 legislative bill analysis, the state reunited only 20 percent of property escheated around that time.

Cash Swept to General Fund Monthly. Rather than allowing the ending fund balance in the UPF to grow each year, the state transfers all but $50,000 to the General Fund each month. Once swept to the General Fund, these properties become General Fund revenues, as described below.

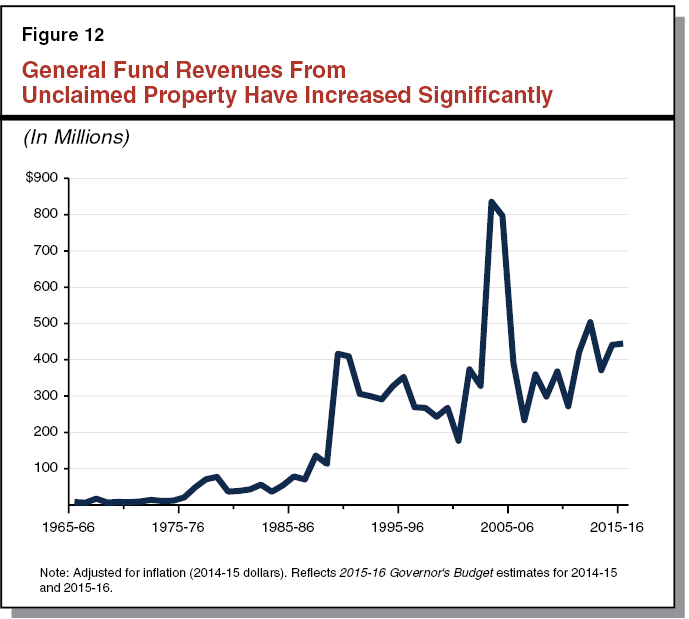

Fifth Largest Source of General Fund Revenue. While constituting less than one–half of 1 percent of General Fund revenue and transfers, revenue from the unclaimed property program is still the fifth largest source of General Fund revenue. (The four largest sources of General Fund revenue—in descending order—are the personal income tax, the sales and use tax, the corporation tax, and the insurance tax.) Revenues from the unclaimed property program are not considered proceeds of taxes, meaning that they are not counted toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for schools and community colleges. In other words, these revenues are able to be used for either Proposition 98 or non–Proposition 98 spending items. The 2015–16 Governor’s Budget estimates that these revenues will be $442 million in 2014–15 and $452 million in 2015–16. Figure 12 displays General Fund revenues from the unclaimed property program since 1965–66, adjusted for inflation.

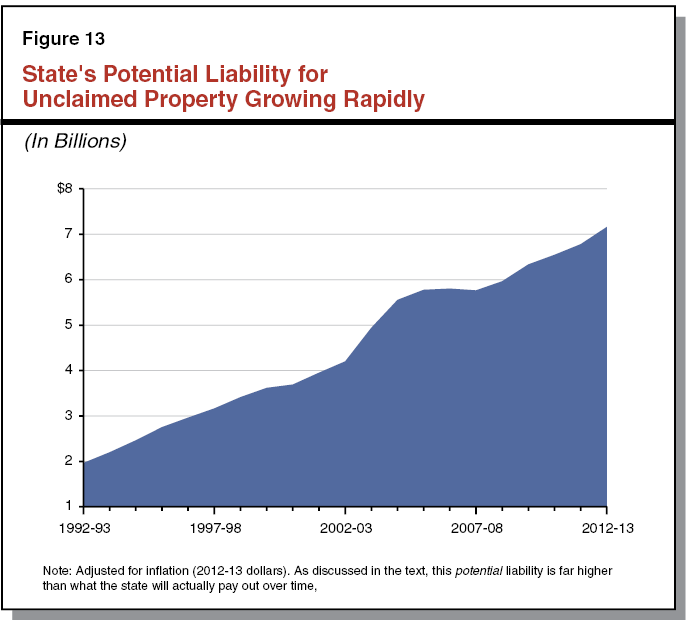

Potential Liability for Unclaimed Property Grows Indefinitely. . . As described earlier, the cash value of unclaimed property is transferred to the General Fund the month after it is received and is available to be spent on state programs. There is presently no limitation, however, on the amount of time that may pass before owners must claim their properties. Because the state routinely takes in more unclaimed property than it reunites with owners, the amount of unclaimed property that could theoretically be claimed by owners grows each year. As shown in Figure 13, the total amount of unclaimed property escheated by the state but not yet claimed by owners is over $7 billion. We refer to this as the state’s potential liability for unclaimed property.

. . .But Impossible to Return All Properties. While the state’s potential liability for unclaimed property is over $7 billion, the state would only pay out this amount if every owner came forward to claim their property. This will never occur for a variety of reasons. For example, some holder records contain very little to no information about owners, rendering reunification with owners virtually impossible. Owners of properties that the state escheated long ago may have died or moved to another state, greatly diminishing the chances of reunification.

Actual Liability Much Smaller. The state’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR)—a display of the state’s finances in compliance with generally accepted accounting principles—includes an alternative estimate of the state’s unclaimed property liability. Specifically, the CAFR includes an estimate of the amount that owners will actually claim in the future. (The estimate is produced in compliance with Governmental Accounting Standards Board Statement No. 21.) This estimate is based on the state’s historical experience in reuniting property with owners. The 2012–13 CAFR reflects an unclaimed property liability of $853 million.

2015–16 Budget Proposes $39 Million for Unclaimed Property Administration. The 2015–16 Governor’s Budget proposes $39.2 million from the UPF for administration of the unclaimed property program. The unclaimed property program has 273 positions performing various functions, as displayed in Figure 14.

Figure 14

Unclaimed Property Staffing By Function

Personnel Years

|

Claims

|

124

|

|

Securities management

|

32

|

|

Owner assistancea

|

23

|

|

Holder reporting

|

22

|

|

Audits

|

16

|

|

Administrative support

|

14

|

|

Financial accountabilityb

|

13

|

|

Operations support

|

9

|

|

Holder compliance

|

8

|

|

Fraud protection

|

7

|

|

Safe deposit box processing

|

7

|

|

Totalc

|

273

|

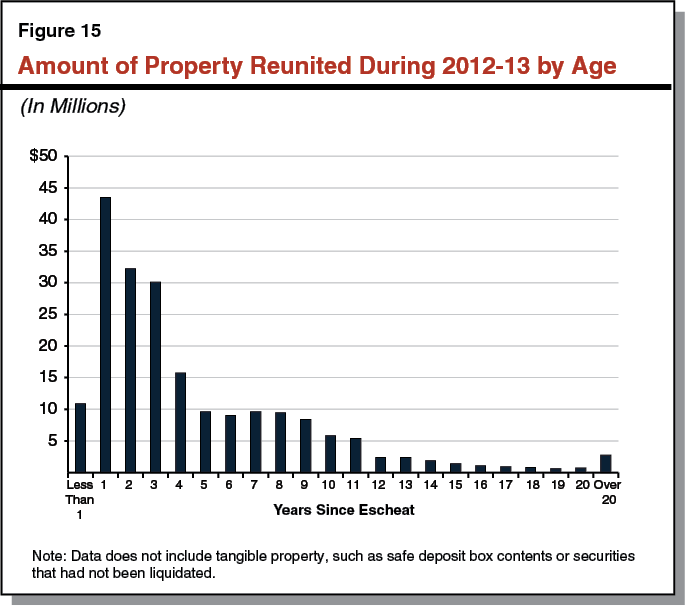

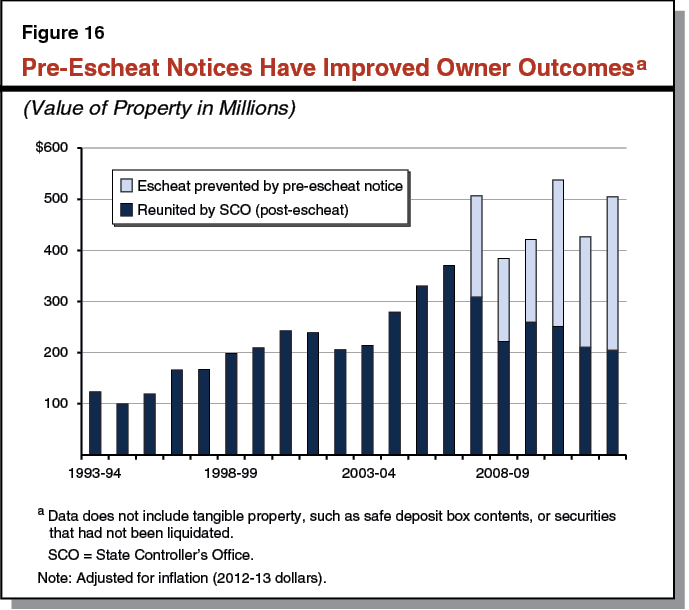

Pre–Escheat Notices Have Reunited More Property With Owners. As shown in Figure 15, most of the property that the state reunites with owners is less than four years old. This suggests that the earlier an owner is contacted, the more likely they will be reunited with their property. Senate Bill 86 resulted in SCO sending more notices sent to owners, and requires SCO to send notices before property is escheated by the state. By reaching out to owners before the property is escheated, owners are more likely to reestablish contact with the holder and keep their property before the state gets involved. Since 2007, this change has resulted in millions of additional notices mailed to apparent owners than would have otherwise been the case. Figure 16 displays the value of properties reunited with owners and properties the escheat of which was prevented by a pre–escheat notice.

Increased Holder Compliance With UPL. In recent years, SCO has increased efforts to enhance compliance with the UPL. For example, SCO’s holder compliance unit (established in the 2012–13 budget): (1) conducts outreach to holders that are not submitting reports to SCO to improve awareness of and compliance with the program, and (2) audits holders to ensure compliance with unclaimed property laws. In addition, SCO began auditing insurance companies in 2008. Twenty–one such companies have since entered into settlement agreements with SCO covering $269 million in properties, about $60 million of which has been reunited with owners. The 2014–15 budget provided SCO with 11 permanent positions and $1.1 million to continue insurance company audits and locate owners of unclaimed insurance properties.

Fraud Prevention. In 2010–11, SCO estimated that $2.8 million in fraudulent claims had been paid between 2000 and 2011. The 2012–13 budget established 17.9 positions at SCO on a two–year limited term basis for a fraud prevention unit. (Sixteen of those positions and $2.1 million were extended for an additional two years in the 2014–15 budget.) The unit: (1) runs all claims through a fraud detection system to verify their legitimacy, (2) investigates suspicious property claims, and (3) prevents payment on those claims found to be fraudulent. In 2012–13, SCO investigated 6,727 claims, ultimately preventing payment on 631 claims valued at $8.5 million.

eClaim Process Reduces Burden of Claiming Properties. Since January 2014, claimants can submit claims through SCO’s website rather than the traditional paper process. The eClaim process is available for properties belonging to a single owner and valued under $1,000. (In December 2014, SCO increased the threshold for eClaim from $500 to $1,000.) Over the same four–month period in 2013 and 2014, the amount of single–owner properties valued under $500 reunited with their owners nearly tripled—both in terms of properties and dollar value—after implementation of eClaim. While some of this could be due to variation in the amount of property escheated in recent years, it is clear that eClaim has resulted in more property reunited with owners.

Because the process does not require printing a form and mailing documentation to SCO, eClaim reduces the administrative burden associated with claiming properties. eClaim therefore results in some owners who otherwise would have chosen not to submit a paper claim proceeding with the online process. Perhaps more importantly, eClaim represents a significant increase in claims processing efficiency, as the amount of time needed to process an eClaim is 30 seconds compared with 30 minutes to 1 hour for a paper claim. In addition, properties claimed through the SCO website are returned within 14 days rather than an average of about 4 months in the case of paper claims. This alternative claims process is clearly an improvement over the traditional paper method.

2013 Law Means More Small Properties Claimed. As mentioned earlier, Chapter 362, Statutes of 2013 (AB 212, Lowenthal), requires holders to report more information for property valued between $25 and $50. Properties reported without identifying information about the owner—referred to as aggregate reporting—are virtually impossible to reunite with owners. Effective July 1, 2014, SCO receives more information for properties valued between $25 and $50. While the total dollar value of these properties is low, Chapter 362 will make it far more likely those properties will be reunited with owners.

Other Recent Successes. Given the fiscal challenges SCO faces in returning more properties to owners—for example, restrictions in the annual budget bill that cap their spending on informing owners about the program—we think some of their other recent efforts are praiseworthy. For example, SCO established a property owner advocate’s office in 2007 that has assisted more than 6,500 individuals with their claims. In addition, the advocate suggests changes to policies and procedures that, in the advocate’s judgment, improves owner outcomes. SCO worked with the California Department of Veterans Affairs to send more than 95,000 notices to veterans who appeared to have unclaimed property. SCO also participated in two telethons to promote the unclaimed property program.

Lack of Public Awareness of Program. We observe that the unclaimed property program suffers from a lack of public awareness. To begin with, the name itself—unclaimed property—is not very user–friendly. It likely prevents potential claimants from quickly understanding the program. The poor branding is likely made worse by limited state efforts to increase public awareness of the program. We think that a lack of public awareness is one of the biggest hurdles to returning more property to owners.

Documentation Requirements for Paper Claims Likely Discourage Some Claimants. Earlier in this report, Figure 7 displayed general documentation requirements for individuals filing paper claims. (Requirements differ somewhat for other types of owners, such as businesses.) As shown in the figure, individuals are instructed to provide various documentation supporting their claim, including various items verifying their identity, proof of addresses at which they lived, and, in some cases, original documentation of the property (such as a bank statement or insurance policy). SCO requires this level of documentation at the outset of the paper claims process to reduce the need to request additional information from the owner later. Based on information from SCO, however, some of this documentation is unnecessary in many cases. For example, when an owner’s name and social security number matches the holder record and SCO can verify the owner lived at the associated address using a fraud detection system, SCO can approve the claim without additional documentation.

Requiring such extensive documentation at the outset of the process likely results in some potential claimants abandoning their paper claim because they find the process too time consuming. In other cases—in particular, for those owners seeking to claim older properties—documents may be difficult or impossible to produce. It seems unrealistic to expect owners to produce documentation from years and, in many cases, decades in the past, especially when that documentation may not be necessary for approval of the claim. Lower requirements for paper claims could encourage more claims and increase the amount of unclaimed property reunited with owners. (Earlier, we noted the success of the SCO’s Internet eClaim process that requires much less documentation.)

Owner Confusion and Skepticism May Also Be Problems. Some owners appear skeptical of state notification efforts. In some cases, this may be due to junk mail they receive touting other opportunities to collect easy money. In other cases, owners are confused when they receive separate notices from the state and investigators. Still other consumers may not file claims due to a general distrust in government and other institutions. These hurdles seem difficult to overcome.

SCO Notes Substantial Potential Holder Under Compliance. In 2013, SCO conducted an analysis of holder compliance. SCO estimated that about 900,000 businesses in California not currently reporting unclaimed property were potentially holders of unclaimed property. Extrapolating from the population of holders currently in compliance with the UPL, SCO estimated that these potentially noncompliant businesses may be in possession of $12.5 billion in unclaimed property.

SCO Does Not Comply With Requirements to Auction Property. Section 1563 of the Code of Civil Procedure requires the Controller to auction physical assets 18 months after they are reported by holders. The state, however, has not held an auction since 2006. As shown earlier in Figure 8, SCO uses public funds to maintain the equivalent of about six full–size vans of valuable property at the State Treasurer’s Office.

Two Recent Initiatives May Be Counterproductive. In the fall of 2014, SCO announced two new unclaimed property initiatives. First, SCO produced a new online database that searches only life insurance properties. While the webpage notes that a different database searches unclaimed property more broadly, we see no point in having two separate databases. It seems to us that some users may unsuccessfully search the life insurance database and abandon their search before realizing they must search a separate database to find noninsurance properties. Second, together with the Labor Commissioner’s Office, SCO launched “Operation Pay–Up.” Under this initiative, the state used the UPL to sue two businesses in an attempt to compel them to provide a total of $263,194 that employees claimed were owed as back wages. It is unclear to us that these unpaid wages are consistent with the main focus of the unclaimed property program. Resources used for this effort could have instead been applied to the core unclaimed property mission.

Law Creates Incentive for State to Return Less Property to Owners. The two goals of the UPL are to (1) reunite property with rightful owners and (2) allow the state rather than holders to use the property if owners cannot be located. These two goals are at odds with one another, such that actions designed to meet one goal erode progress in achieving the other. For example, reuniting more property with owners means that the state receives less revenue and that the state budget is worse off. The opposite is true as well. The state has an incentive to reunite less property with owners, thereby increasing General Fund revenue. These competing goals have created tensions between two opposing program identities—unclaimed property as a consumer protection program and as a source of General Fund revenue.

Tension Between Competing Roles a Historical Problem. The tension between these two roles seems to have been a problem since the beginning of the program. For example, in 1961–62—while the state was beginning to implement the UPL—SCO requested additional midyear funds to process the greater–than–expected workload associated with safe deposit boxes escheated by the state. In our Analysis of the 1963–64 Budget Bill, we noted that the administration at that time reduced the number of requested positions by half on the basis that there was insufficient information at the time to determine whether the program would produce enough revenue to justify screening all boxes. It was SCO’s position at the time that the request should not be evaluated based on the resulting General Fund revenues, but rather on SCO’s legal responsibilities to escheat the boxes under the UPL. Similarly, in our Analysis of the 2000–01 Budget Bill, we noted that the state finally had an opportunity “to consider an aggressive approach in returning unclaimed property to its rightful owners” because the budget situation at the time allowed the state to rely less on revenues from unclaimed property.

Legislature Could Clarify Program Goals. Over time, the goal of reuniting property with owners has often lost out to the competing goal of raising money for the state General Fund. This is because when the state’s officials are considering proposals to increase the return of property, they are confronted with the prospects of lower General Fund revenues now and in the future. This can result in undervaluing the benefits of reuniting more unclaimed property with the state’s residents. We think it would be helpful for the Legislature to acknowledge this tension and clarify the unclaimed property program’s goals for the future.

Setting Clear Goals to Improve Owner Outcomes. By setting clear performance goals, the Legislature could consider directly the extent to which the program should be more focused on returning unclaimed property to owners. For example, the Legislature could consider the following goals.

- Increase Dollar Value Returned. The average amount of property that the state returned over the last 20 years—in dollar terms—was about 40 percent. The Legislature could choose to establish a target of returning a certain amount of escheated property to owners—for example, 50 percent or 60 percent. The higher this percentage, the greater the reduction will be in General Fund revenues.

- Return a Target Amount of Unclaimed Property. Over the past ten years, the state has reunited an average amount of about $250 million per year with owners, adjusted for inflation. The Legislature could establish a goal of reuniting a greater annual amount. The higher this goal is, the greater the reduction will be in General Fund revenues.

- Achieve a Certain Return on Increased Program Spending. The state’s tax agencies have been given additional audit or collection resources with the understanding that they would achieve a minimum return per dollar (say a 3 to 1 ratio). The Legislature could establish a similar target return for additional resources given to the SCO to ensure that monies were being spent efficiently.

By establishing such measures, the Legislature would be creating a more helpful context in which to consider proposals related to the administration of the unclaimed property program. In other words, such targets could focus attention on longer–run objectives of reuniting unclaimed property with owners. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature adopt performance measures that place greater emphasis on the goal of reuniting property. Such an emphasis likely would reduce General Fund revenues from unclaimed property in the future. Below, we turn to a variety of options the state could consider to achieve such a goal.

In the course of our review, we came across many ideas—such as those discussed or tried in other states or considered in the past by the SCO—to increase the amount of unclaimed property reunited with owners. Figure 17 lists a variety of options, discussed in more detail below, which we believe merit consideration. These options would have to be fleshed out prior to their adoption and implementation, but we think the list illustrates the steps the state could take to reach its program objectives. In some cases, options could be evaluated on a pilot basis. While SCO may be able to implement a few options administratively, others would require changes in law or additional resources.

Figure 17

Options for Reuniting More Property With Owners

|

Automatic Payments to Tax Filers

|

- Send automatic payments to tax filers whose information matches unclaimed property records.

|

|

Documentation Requirements

|

- Reduce owner burden by lowering paper claim documentation requirements.

- Allow claimants to upload documents online.

- Increase eClaim threshold.

|

|

Enhanced Notification Efforts

|

- Expand efforts to find owners and notify them of their property.

- Lower threshold for pre–escheat notification.

|

|

Advertising and Outreach Campaign

|

- Increase public awareness by advertising in additional media, such as social media, radio, and television.

- Contract with marketing experts to improve outreach and branding.

- Conduct targeted telephone outreach.

- Create a mobile unit that visits state and county fairs, malls, and other large gatherings.

- Publicize top unclaimed property owners or regions.

|

|

Database Enhancements

|

- Create a feature that suggests possible matches to users.

- Create a shopping cart feature to allow users to claim more than one property at once.

- Allow users to search more fields.

- Perform periodic database search on behalf of users.

- Clean errors in data, such as misspelled cities.

|

|

Increasing Holder Compliance

|

- Conduct another amnesty program.

- Decrease 12 percent penalty for noncompliance.

|

|

Investigators

|

- Increase investigator rewards on cold cases.

|

Wisconsin Program Will Return Property Without Owners Filing Claims. In August 2013, Wisconsin’s unclaimed property program was transferred from the Office of the State Treasurer to the Department of Revenue. A recent law requires the Department of Revenue to return unclaimed property to tax filers owed unclaimed property without the owner having to file a claim. If the sum of the net tax liability and unclaimed property is $2,000 or less, the property is automatically reunited with the owner. If the amount is over $2,000, the department sends a written notice to the tax filer alerting them to the existence of their unclaimed property.

Program Makes a Lot of Sense. As part of their efforts, Wisconsin integrated unclaimed property data into their tax processing system. Officials note that individuals and businesses owning unclaimed property tend to be tax filers, indicating that similarly linking California’s unclaimed property program to its tax administration system could make sense. In addition, these efforts may prove less costly than other alternatives highlighted in this report, in particular some types of advertising. It could also free up staff resources to focus on higher value unclaimed property.

Idea Promising. Wisconsin’s aggressive efforts offer a promising opportunity to reunite more property with owners. SCO could send potential matches to state tax agencies for cross checking with those agencies’ records of tax filers. (SCO already coordinates with FTB for pre–escheat notices.) When a tax agency identifies a match, it could augment the tax filer’s refund or SCO could mail a check to the tax filer at the address the filer identified in their tax return.

Reduce Owner Burden by Lowering Paper Claim Documentation Requirements. As described earlier, the current documentation requirements for paper claims are excessive in some cases. One option to return more property would be to lower the documentation required at the outset of the paper claims process. This would (1) make the process significantly easier for many claimants, (2) increase the number of claims, and (3) increase the amount of unclaimed property reunited with owners.

Allow Users to Upload Documents Online. Another way to lessen the administrative burden on claimants would be to allow them to scan and submit supporting documentation online. Users could even take pictures of documents with their phones, as many banks now allow their customers to do when depositing checks. As seen with the eClaim program, efforts to make the claims process easier can result in more property reunited with owners.

Increase eClaim Threshold. The eClaim process has reunited properties with claimants who otherwise would have been intimidated by the burden of the paper process. As noted earlier, in December 2014, SCO increased the threshold for eClaim eligibility from $500 to $1,000. To further increase the number of eClaims and reduce the documentation burden on owners, the Legislature could direct SCO to make the eClaim option available for more properties. For example, increasing the threshold to $10,000 could nearly double the value of properties eligible for eClaim. (We note that this could require directing SCO to change its notary or other claims requirements.)

Seek Updated Contact Information for Owners. SCO uses a system to detect fraud in the unclaimed property program. The system culls public records—for example postal service change of address forms, property tax records, and phone books—to gather current and prior addresses, phone numbers, and other identifying information about individuals. When an individual submits a claim with a new address that differs from the holder record, for example, SCO can use this system to verify that the owner actually lived at the address from the holder record.

Sending Additional Notices. SCO currently uses this fraud system for locating efforts on a small scale. These efforts could be expanded to find new addresses and other contact information for owners and notify them of their unclaimed property. Figure 18 displays SCO’s rough estimates of property reunited with owners under four alternatives. The amount of property reunited under these scenarios ranges from $30 million to $80 million per year, depending on the number of notices sent. The figure reflects additional personnel requirements, as these efforts would result in an increase in claims processing workload. That workload, however, could be partially offset by efforts to make the claims process simpler, such as increasing the number of properties eligible for eClaim. SCO estimates that around 5 million properties valued over $50 owners can potentially be searched, meaning that under any of these scenarios several years could pass before SCO would exhaust possible properties to investigate.

Figure 18

SCO’s Rough Estimates of Outcomes Under Four Alternatives for Increased Notification Efforts

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Alternative

|

Estimated Annual Searches

|

Estimated Annual Matches

|

Estimated Claims Filed

|

Additional Claims Positions

|

Estimated Cost

|

Projected Property Reunited

|

|

1

|

460,000

|

184,000

|

42,000

|

20.7

|

$2.3

|

$29.8

|

|

2

|

713,000

|

284,000

|

65,000

|

29.4

|

3.3

|

44.7

|

|

3

|

1,013,000

|

405,000

|

92,000

|

39.9

|

5.0

|

62.1

|

|

4

|

1,313,000

|

525,000

|

119,000

|

50.1

|

6.3

|

79.6

|

Lower Threshold for Pre–Escheat Notification. SCO sends pre–escheat notices to owners of properties valued over $50 and for whom holders have listed an address in their report to SCO. As described earlier, beginning in 2014–15 the state will have better information about owners of properties valued between $25 and $50. Only $12.8 million (or 2 percent) out of the roughly $550 million in property escheated in 2011–12 was valued under $50. While lowering the threshold for pre–escheat notification to $25 could return a significant number of properties, it would not return a significant amount measured in dollar terms.

The lack of public awareness of the unclaimed property program means that an expanded outreach effort could result in more owners coming forward to claim their property. The target population, however, could be difficult to reach. To maximize the effectiveness of a media campaign, the state may want to seek the advice of professionals that could help direct public resources to media most likely to reach owners of unclaimed property. Below, we present some possibilities for outreach of this type.

Opportunities to Supplement Current Efforts. The UPL requires SCO to publish a notice to owners of unclaimed property in a newspaper of “general circulation.” In 2014–15, SCO spent $38,000 on these notices. We are skeptical that the population of unclaimed property owners—individuals and businesses who have lost track of their assets—are highly correlated with the population of subscribers to physical newspapers. State resources might be spent more efficiently on advertising more through other media, such as radio, television, and social media and other Internet advertising.

Social Media Advertising. Social media sites in particular may enable SCO to reach out to individual owners directly. For example, if an unclaimed property record lists an apparent owner in Sacramento and a social media user profile appears to match, SCO might be able to advertise directly on that user’s feed. The Legislature may wish to consider a pilot program to determine whether dollars spent on advertising through these media would achieve a greater return than current methods.

Marketing and Rebranding Efforts Might Help. We think that a lack of public awareness of the unclaimed property program is a significant hurdle to reuniting more property with owners. An updated branding strategy could connect better with owners. Some other states, for example, use terms like “lost and found” or “treasure hunt” to promote their programs. The Legislature may want to consider a one–time appropriation to SCO to contract with marketing experts to work on improving outreach and branding of the unclaimed property program. The state could even consider using a celebrity in its campaign to create more interest and encourage more owners to claim their property.

Targeted Telephone Outreach. Some states call apparent owners to notify them of their unclaimed property. For example, Nebraska officials reported in October 2014 that such efforts reached 28,000 apparent owners, resulting in $1.4 million in property claims. This would have represented about one–fifth of the property reunited in that state during 2012. Kansas also targets apparent owners through telephone outreach. SCO could use their fraud detection system to obtain owner phone numbers, reach out to owners over the phone, and provide them instructions on how to make a claim.

Create a Mobile Unit That Visits Locations Where Large Groups Gather. Many other states send representatives of their unclaimed property program to public gatherings to conduct outreach. For example, Maryland’s Comptroller recently reported that efforts at four fairs and festivals throughout the state reunited 2,000 people with $2.5 million in unclaimed property, including one owner who was reunited with $71,516. In addition to the state fair, county fairs, and other festivals, a mobile unit could visit shopping malls, sporting events, and other gatherings.

Publicize Top Unclaimed Property Owners or Regions. SCO could post top owners of unclaimed property statewide or the top regions for unclaimed property (for example, by county or zip code). Such a list could enhance public awareness of the program and might result in some owners being tracked down by friends and relatives. It could also result in free publicity of the program in news outlets. Some might express concerns about privacy or the possibility that some individuals—for example seniors—could be exploited if the top individual owners of unclaimed property are publicized. We note, however, records can be searched free of charge on SCO’s online database, and the information already is available in a sortable format for a modest fee.

Virginia’s Address Suggestion Feature Promising. One possible upgrade to the unclaimed property database could be an address suggestion feature. Virginia’s database, for example, allows users to enter their name and then suggests cities in which they have lived and streets on which they have lived. The system then displays possible matches of unclaimed property. Virginia’s database seems more effective than California’s, particularly for users living in large cities, who have common names, or who have lived at many addresses.

Allow Users to Place Multiple Properties in a Shopping Cart. As presently configured, SCO’s database allows users to claim only a single property at a time. The database could be enhanced to allow users to check multiple properties, place them in a shopping cart, and complete a single process to claim them all. This would significantly reduce the claims burden for those users with multiple unclaimed properties.

Allow Users to Search More Fields. Many holder records contain inaccurate information. Records may contain misspelled names, switched first and last names, misspelled addresses, or other errors. SCO’s database is presently configured to search first name, middle initial, last name, business or government name, property identification number, and city. If holder records for these fields are incorrect, however, users may not be able to locate their property. This problem could be alleviated by allowing users to search addresses, social security numbers, and other identifying information. If, for example, a holder record contained an accurate social security number but inaccurate information in other fields, a user might be able to locate their property by searching their social security number. Concerns about identify theft could be addressed by allowing users to enter only part of their social security number. (Virginia’s database allows users to enter only the last seven digits of their social security number.) This would seem to protect consumers while at the same time enabling users to better locate their unclaimed property.

Perform Periodic Database Searches on Behalf of Users. As currently designed, the unclaimed property program loses contact with owners once they complete a database search or—if they find property—upon completion of the claim. We think it would be preferable to maintain these relationships beyond these first interactions. SCO’s website and paper claims could be updated to allow users to opt into an automated search that would email the user periodically to alert them of the existence of new unclaimed properties in their name. Users could provide various levels of information—including past addresses, names, and other identifying information—to capture as much of their property as possible.

Allow SCO to Clean the Data. One problem with the database appears to be inaccurate holder records. A sample search on SCO’s mobile site returned at least 18 variations on the city “San Bernardino.” (Searches in other, easier–to–spell cities return far fewer errors.) The Legislature could direct SCO to clean these records, which would make it easier for some owners to find their unclaimed property.

Conduct Another Amnesty Program. As described earlier, a holder amnesty program in the early 2000s resulted in 4,927 holder reports detailing 145,903 properties valued at $196 million. To enhance holder compliance and make more properties available for users to claim, the Legislature could authorize another amnesty program. Particularly if combined with an advertising campaign that raised public awareness of the program, another amnesty period could be successful in making more properties available to be claimed by owners. Allowing penalties to be waived too frequently, however, might provide holders an incentive to remain out of compliance with the law until the next amnesty program. An option to address this incentive could be to limit the program to holders who have never reported in the past.

Decrease 12 Percent Holder Penalty for Failure to Report or Deliver Property. The current 12 percent per year penalty was set in 1976, a period characterized by relatively high inflation and interest rates. We think that penalty may be excessive, and could discourage some holders from coming into compliance with the UPL. By lowering the fee, more holders might come into compliance with the law, increasing the amount of property available to be claimed. Another option could be to maintain a higher fee for holders who were once in compliance but at some point chose to discontinue submitting reports.

Change Incentives for Investigators. As described earlier, investigators that help owners find their property may charge a fee of up to 10 percent of the value of the claim. Under current law, that fee is fixed no matter the age of the property. As shown earlier in Figure 15, more than half of the property returned in 2012–13 was less than four years old. This means that the older a property is, the less likely it will be reunited with owners. The Legislature could change the investigator incentives by increasing the fees as properties grow older. The Legislature could establish a schedule, starting with a very low fee for returning one–year old properties, and steadily increasing thereafter. Changing these investigator incentives could focus their efforts on the harder cases and reward them accordingly.

Require SCO to Auction Properties of Commercial Value. The UPL requires SCO to auction properties of commercial value, but not before 18 months after the holder reporting deadline. SCO, however, has not held an auction since 2006. As described earlier, the goals of the law are twofold. First, the law seeks to reunite unclaimed property with its rightful owner. Second, the law gives the state rather than the holder the benefit of the use of properties that cannot be reunited. If valuable tangible property cannot be reunited with owners, the state can only benefit from its use by selling those properties at public auction. As the program stands, the state does not benefit from indefinitely storing properties with commercial value. We therefore recommend that the Legislature require the Controller to auction properties with commercial value.

Destroy Properties Without Commercial Value. The Controller’s Internet website touts unusual unclaimed property, including historical newspaper articles, baseball cards, jewelry, and other items with commercial value. The website also displays items of no commercial value, such as family photos. As shown in Figure 8, SCO maintains the equivalent of over 12 cargo vans of space in which it stores these items. The UPL requires SCO to retain properties without commercial value for seven years. While the UPL allows SCO to destroy these items, it does not require it.

While we understand the sensitivity of destroying certain properties of no commercial value—such as family photo albums—we think their indefinite storage is an unnecessary expenditure of public resources. In particular, it strikes us as particularly problematic for the state to spend money to store items like some featured on the Controller’s website, such as sardines in tomato sauce, evaporated milk, and miniature bottles of liquor. We recommend that the Legislature require the Controller to destroy properties without commercial value. The Legislature could choose to retain the seven–year grace period in current law or establish a new time limit.

Consider Options for Managing Number of Properties. As of the end of 2013–14, the state had escheated 28.4 million properties that had not been claimed by owners. Under current law, the state maintains an indefinite obligation to return unclaimed property. This means that—absent changes to the program—the amount of unclaimed properties will only continue to grow. Over time, SCO’s database will only become more inundated with records, making it harder for individuals—particularly those that live in large cities or that have common names—to find their property. We suggest that the Legislature consider the two options listed below for managing the number of properties.

- Move Older Properties to a Separate Database. As properties age, they are less likely to be reunited with owners. In 2012–13, only 3 percent of property reunited with owners had been escheated more than 15 years. These properties are featured just as prominently on SCO’s database as property that is far more likely to be reunited with owners. The Legislature could require older properties be moved to a separate database to streamline owner searches.

- Establish a Time Limit on Claiming Property. The Legislature could also choose to limit the amount of time during which an owner can claim their property. (Prior to 1959, the state permanently escheated property that had remained dormant for 20 years.)

The state’s unclaimed property program dates back to the end of the 19th century. It has been shaped over the decades by legislative changes, court decisions, and shifts in the way people keep and hold assets. While there has always been a tension between the program’s goals of reuniting property with owners and raising General Fund money, fiscal considerations have often dominated decision–making regarding how the program is administered.

Our review suggests the Legislature may want to take a fresh look at the program, particularly with regard to the objectives it wants to achieve. We offer a variety of recommendations to the Legislature—summarized in Figure 19—to assist it in its work. We believe a greater emphasis on reuniting property is appropriate. A variety of options exist that could help achieve that goal in efficient and cost–effective ways.

Figure 19

Summary of LAO Recommendations for Unclaimed Property

|

Place Greater Emphasis on Reuniting Property

|

- Establish performance measures for the unclaimed property program that places greater emphasis on reuniting property with rightful owners.

|

- Consider which options to implement to achieve new performance measures.

|

|

Other Recommendations

|

- Require the State Controller’s Office to auction valuable items after 18–month waiting period already in law.

|

- Destroy valueless items after owners given reasonable opportunity to claim.

|

- Consider approaches for managing continuously growing stock of properties.

|

- Move older, less likely–to–be–claimed properties to a separate database.

- Establish a limit on the amount of time property can be claimed.

|