State Provides Services in Homes and Communities to SPDs. Today, about 1.9 million SPDs are enrolled in California’s Medicaid program (known as Medi–Cal), the state–federal program providing medical and long–term care to low–income persons. The number of SPDs served by Medi–Cal will likely grow as the baby boom generation ages. By 2030, the number of Californians age 65 and older is projected to increase by about 60 percent. This growth in the aging population will undoubtedly put fiscal pressure on Medi–Cal and possibly strain Medi–Cal’s system of long–term care services and supports (LTSS) provided to SPDs. There are two main types of LTSS: (1) HCBS and (2) institutional care. The HCBS are provided in a client’s home and community, while institutional care is provided in a facility, such as a SNF. In this report, we focus on three HCBS programs provided by the state: In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS), Community–Based Adult Services (CBAS), and the Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP).

HCBS Assessments Generally Include Three Main Components. In California, assessors for each HCBS program determine eligibility and conduct an assessment to determine the amount and type of services that a client may need from the particular program to remain safely in his/her home and community. An assessment generally includes questions that cover one or more of the following three areas: (1) medical needs, (2) routine daily functional needs, and/or (3) consumer characteristics. In Figure 1, we provide our working definition of these three main components of HCBS assessments.

Figure 1

Three Main Components of Home– and Community–Based Services Assessments

- Medical Needs. An assessment of medical needs generally involves the collection of information related to an individual’s physical health, such as medical diagnoses, medications taken, or a bodily systems review. (The assessment of medical needs is different and separate from the medical record retained by a health care provider.)

|

- Routine Daily Functional Needs. An assessment of functional needs generally involves the collection of information related to an individual’s ability to perform routine daily activities, such as bathing, dressing, or meal preparation.

|

- Consumer Characteristics. This category is broad and may include an assessment of the following: a consumer’s psychological functioning, his/her preferences for receiving care, his/her financial status, safety of the consumer’s living arrangements, or informal and formal assistance the consumer receives. Collecting this type of information can help determine the type and amount of services to be provided.

|

Legislature Has Expressed Concerns About Current Assessment Approach. Currently, clients who receive services from more than one HCBS program undergo multiple assessments that, in some areas, collect duplicative information. These assessments are typically paper forms used by assessors for each program. The Legislature has expressed concerns that this fragmented approach to HCBS assessment creates administrative inefficiency and hinders the ability to coordinate the care of clients receiving services from more than one HCBS program. Given these concerns, the Legislature has enacted legislation, as discussed below, to move the state to an alternative approach.

Legislature Has Identified UAT as a Way of Improving HCBS Assessment System. As part of the 2012–13 budget, the Legislature enacted the Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI), with the intent to promote care coordination among SPDs by integrating health care and LTSS benefits in up to eight pilot counties. (We describe the CCI in greater detail later in this report.) Reflecting the Legislature’s concerns about the current assessment approach, the CCI also includes the development and implementation of a UAT for the state’s three major HCBS programs—to be piloted in a select number of the CCI counties. This component of the CCI is the focus of this report.

The UAT is a single application and data system that would streamline eligibility determinations and assessments for the state’s major HCBS programs. We define this UAT as being “universal” in two respects.

- The UAT would comprehensively determine an individual’s needs for HCBS. In our review of existing assessment tools, we found that they generally collect information in three broad areas defined in Figure 1—that is, medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics.

- The UAT would use the comprehensive information collected on an individual’s medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics to determine an individual’s eligibility and, in most cases, the authorized amount and type of service needs for the state’s major HCBS programs.

The assessor administering the UAT would draw on the full range of HCBS for which the consumer is found to be eligible and other pertinent information to develop the consumer’s HCBS care plan, which ultimately determines the specific amount and type of HCBS to be delivered. As we will discuss in this report, we find that this approach can facilitate the coordination of care for clients with high needs or who may receive more than one HCBS program. We note that more than one–half of states are either already using or preparing to adopt a UAT for HCBS. Typically, a UAT is a computer–based tool that assessors access via laptop computer when conducting an in–home assessment.

Development and Pilot Implementation of UAT Is Authorized, but Policy Decisions Remain. The CCI legislation—Chapter 45, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1036, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review)—requires the state’s Department of Social Services (DSS) and the California Department of Aging (CDA) to convene a stakeholder workgroup to develop the UAT. The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) is also participating in the workgroup. The workgroup met for the first time in September 2013 and plans to continue its work of developing the tool through 2015. At the time of this analysis, our understanding is that piloting of the UAT will take place in 2016–17. Although the workgroup has started, there are several fundamental policy choices related to the development and implementation of the UAT for which Chapter 45 is silent. We offer an analysis of these policy decisions to assist the Legislature and the stakeholder workgroup as it continues its development efforts.

In this report, we first provide an overview of Medi–Cal and HCBS and then identify problems with the current HCBS assessment process. We then discuss benefits to the HCBS system of adopting the UAT, costs associated with developing and implementing the UAT, and implementation issues the state must address during the UAT’s pilot phase. Finally, we make a number of recommendations to guide the development and pilot implementation of the UAT in the state.

Medicaid Is a Joint Federal–State Program. Medicaid is a joint federal–state program that provides health coverage to low–income populations. In California, the Medicaid program is primarily administered by DHCS and is known as Medi–Cal, although some benefits are administered by other state departments (such as DSS). The federal government pays for a share of the cost of each state’s Medicaid program. The Medi–Cal program generally receives one dollar of federal funds for each state dollar it spends on those services. (The federal share of costs has increased for some of the Medi–Cal population under federal health care reform.)

Medi–Cal Provides a Wide Range of Health–Related Services. Federal law establishes some minimum requirements for state Medicaid programs regarding the types of services offered and who is eligible to receive them. Required services include hospital inpatient and outpatient care, SNF stays, emergency services, and doctor visits. California also offers an array of medical services considered optional under federal law, including HCBS.

Services Are Provided Through Two Main Systems. Medi–Cal provides health and long–term care through two main systems: fee–for–service (FFS) and managed care. In a FFS system, a provider receives an individual payment for each service provided. In a managed care system, managed care plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Unlike FFS providers, managed care plans assume financial risk, in that it may cost them more or less money than the capitated amount paid to them to deliver the necessary care. In 2014–15, managed care enrollees will account for more than 70 percent of Medi–Cal beneficiaries. While LTSS have been delivered on a Medi–Cal FFS basis in all counties, they are transitioning to Medi–Cal managed care benefits in the CCI counties, as will be discussed later.

HCBS Are Medi–Cal Benefits

Medi–Cal provides LTSS—both HCBS and institutional care—to beneficiaries who meet certain eligibility requirements. Unlike medical care provided during hospital stays or doctor visits, HCBS must be integrated into a client’s daily life for an extended period of time and often involve family caregivers. California spends more than 50 percent of its total Medicaid long–term care dollars on HCBS. The average cost of institutional care in a SNF is currently about $70,000 annually per person whereas the average annual cost of the vast majority of HCBS per person is considerably less. Below, we describe the three Medi–Cal HCBS programs covered in this report.

IHSS. The IHSS program—administered at the state level by DSS—provides personal care and domestic services to individuals to help them remain safely in their own homes and communities. Recipients, who must be aged, blind, or disabled, are eligible to receive up to 283 hours per month of assistance with tasks such as bathing, dressing, housework, and meal preparation. In most cases, the recipient is responsible for hiring and supervising a provider—oftentimes a family member or relative. Social workers employed by county welfare departments conduct an in–home IHSS assessment of an individual’s functional needs in order to determine the amount and type of service hours to be provided.

CBAS. The CBAS program—administered at the state level by DHCS and CDA—is an outpatient, facility–based program that provides the following services: skilled nursing care, social services provided by a social worker, therapies, personal care, family/caregiver training and support, meals, and transportation to and from the participant’s residence. The CBAS centers—both for–profit and nonprofit at the local level—deliver services by a multidisciplinary team, including: nurses; physical, occupational, and speech therapists; social workers; dieticians; mental health professionals; and others. As a result of a court settlement, this program replaces the Adult Day Health Care (ADHC) program, which was eliminated as a Medi–Cal benefit in March 2012. Unlike most other LTSS, CBAS are currently delivered as a managed care benefit in counties with historically operating Medi–Cal managed care systems. (At the time of this analysis, CBAS is only delivered as a FFS benefit in the rural counties that recently transitioned to Medi–Cal managed care systems in 2013.)

MSSP. The MSSP—administered at the state level by CDA—provides social and health case management services for Medi–Cal beneficiaries age 65 or older who meet the clinical eligibility criteria for a SNF, meaning they have a medical and/or functional need for continuous skilled nursing care. The MSSP care managers—registered nurses and social workers—develop a care plan that identifies needs and arranges for appropriate Medi–Cal and community services. The care plan is updated by care managers through monthly telephone calls and quarterly face–to–face visits. The care managers are employed by local MSSP sites—typically a nonprofit entity or a unit of local government under contract with CDA. Each MSSP site has funds reserved for the purchase of goods and services necessary to maintain a person in the community after all other private or public program options have been exhausted. Purchased goods can include items such as a personal emergency response system, safety guardrails for a bathtub or toilet, or an air conditioner. Purchased services can include services such as adult day care, personal care and domestic services, respite for caregivers, transportation, or meal services.

Other HCBS. The state provides a number of other HCBS programs to SPDs, including individuals with developmental disabilities. However, this report focuses exclusively on IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP—the three programs to be included in the UAT pursuant to the CCI legislation.

HCBS Are Preferred Over Institutional Care. Many of the SPDs eligible for IHSS, CBAS, and/or MSSP prefer these programs over institutional care because HCBS programs enable clients to remain in their homes and communities. Surveys show that consumers in need of long–term care strongly prefer to remain in their own homes and communities. In addition, disability and senior advocacy groups advocate for long–term care that promotes clients’ independence and privacy.

Further, longstanding federal policy—reflected in the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1999 Olmstead decision—requires public entities to provide services to individuals with disabilities in integrated community–based settings. In practical terms, Olmstead confirmed that states must ensure that Medicaid beneficiaries are not placed into institutional care when they could reasonably receive services in a less restrictive community–based setting.

Medi–Cal Eligibility Is Generally Required Before HCBS Eligibility Determination and Assessment Is Conducted

Medi–Cal eligibility is generally a precondition for consumers to receive state–funded HCBS. Currently, for most individuals who go on to receive HCBS, the methodology to determine Medi–Cal eligibility is complex—it requires a calculation of individuals’ income, accounting for a variety of income deductions and exemptions; verification of assets; as well as fitting into specific eligibility categories, such as having a disability. In general, individuals apply for Medi–Cal in person, by mail, or online, and eligibility is determined by a county eligibility worker. Individuals who are aged (65 and over), blind, or disabled and qualify for Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment cash assistance are automatically enrolled in Medi–Cal. The SPDs who are covered by Medi–Cal and in need of HCBS undergo an eligibility determination and assessment for each HCBS program.

HCBS Assessment Processes

As we have noted, each HCBS program requires its own eligibility determination and assessment (beyond the generally required Medi–Cal eligibility determination) to determine the amount and type of services that a client is authorized to receive from a particular program. We note that anyone can refer a potential client to be screened for receipt of HCBS. Generally, referrals are made by the potential client, a family member, or a health care provider. Figure 2 provides a brief overview of the three HCBS on which we focus in this report and their respective assessment processes. Generally, the assessments for IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP are not conducted using automated computer–based systems. Rather, they are typically conducted using paper–based assessments and oral interviews unique to each program. Below, we provide a detailed discussion of each of these assessment processes.

Figure 2

Current Assessment Processes for Three Major HCBS Programs

2013–14 (Dollars in Thousands)

|

HCBS Program

|

Population Served

|

Estimated Caseload

|

Estimated State Costs

|

Assessment Process

|

|

In–Home Supportive Services provides in–home personal care and domestic services to individuals to help them remain safely in their own homes and communities.

|

Aged (65 and over), blind, or disabled individuals.

|

429,635

|

$2,017,939

|

In–home assessment conducted by a county social worker using a statewide standardized assessment to determine the number of service hours to be provided to the consumer.

|

|

Community–Based Adult Services (CBAS) is an outpatient, facility–based program that provides services to program participants by a multidisciplinary staff.

|

Adults with chronic medical, cognitive, or mental health conditions and/or disabilities who are at risk of needing institutional care.

|

28,777

|

140,877

|

Eligibility determination conducted by managed care plan (or by state nurse for fee–for–service [FFS] applicants), which is followed by a multidisciplinary team assessment and individual plan of care (IPC) developed by the multidisciplinary staff of the CBAS center. The IPC requires authorization by the managed care plan (or Medi–Cal field office for FFS applicants).

|

|

Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP) provides social and health case management services.

|

Adults age 65 and older who are eligible for skilled nursing facility placement.

|

11,103a

|

20,232

|

A nurse and social worker employed by the local MSSP site conduct an initial health and psychosocial assessment, respectively, to determine eligibility and needs for case management services.

|

IHSS Assessment Process

IHSS Assessment Primarily Assesses Routine Daily Functional Needs. The DSS requires county social workers to use a standardized assessment to determine eligibility for the IHSS program as well as the number of service hours to be provided for various tasks. The IHSS assessment—which takes place in the individual’s home—generally relies on a scale depicted in Figure 3 for county social workers to assign a ranking (1–5) for an individual’s functional ability in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). The ADLs refer to daily self–care activities performed by individuals in their home, such as bathing, grooming, or eating. The IADLs—such as housework, laundry, or shopping—are not necessary for fundamental functioning, but allow individuals to live independently in their homes and communities. A functional index (FI) ranking of 1 is considered the lowest impairment level while a 5 is the highest. This FI ranking corresponds to a range of hours for a related task—known as the hourly task guideline—that provides guidance to county social workers when determining the number of service hours to authorize for a particular task. For instance, a higher FI ranking for an ADL or IADL will typically lead a county social worker to authorize more time for the corresponding task. The FI ranking system and related hourly task guidelines developed by DSS generally seek to ensure that county social workers authorize service hours for tasks using a standardized methodology that promotes a consistent determination of needs for all consumers. In addition to the FI ranking and hourly task guidelines, the county social worker considers his/her observations of the consumer, the consumer’s living arrangements, and comments made by the consumer and/or the caregiver when making a determination of the number of service hours to authorize for each of the 25 tasks in the IHSS assessment.

Figure 3

Five–Point Scale for Assessing an Individual’s Functional Ability for ADLs and IADLs in the IHSS Assessment

|

Rank

|

Classified as Such if. . .

|

|

1

|

His or her functioning is independent, and he or she is able to perform the function without human assistance; although the recipient may have difficulty in performing the function, the completion of the function, with or without a device or mobility aid, poses no substantial risk to his or her safety.

|

|

2

|

He or she is able to perform a function, but needs verbal assistance, such as reminding, guidance, or encouragement.

|

|

3

|

He or she can perform the function with some human assistance, including, but not limited to, direct physical assistance from a provider.

|

|

4

|

He or she can perform a function, but only with substantial human assistance.

|

|

5

|

He or she cannot perform the function, with or without human assistance.

|

IHSS Assessment Also Collects Information on Consumer Characteristics and Medical Needs. County social workers are required to ascertain in their assessment the alternative resources—such as assistance received from community–based health programs or senior centers—that help consumers perform routine daily activities. For instance, a county social worker may find that a consumer receives home–delivered meals, which is then considered when determining the number of IHSS hours for related tasks (such as meal preparation and cleanup). Further, the IHSS assessment collects some information related to medical needs as reported by the consumer, including medical diagnoses, medical problems, and medications taken. This information may be used by a county social worker to better understand the observed functional impairments of an individual.

CBAS Eligibility Determination and Assessment Process

CBAS Eligibility Determination and Assessment Is a Four–Step Process. As a result of the ADHC court settlement, the required eligibility determination and assessment process for CBAS as a managed care plan benefit includes four steps.

- Step One: Initial Eligibility Determination. A nurse affiliated with the CBAS applicant’s managed care plan uses the standardized CBAS eligibility determination tool (CEDT) developed by DHCS to conduct a face–to–face eligibility determination.

- Step Two: Assessment of the Individual. Once the applicant is determined eligible for CBAS using the CEDT, the CBAS center’s multidisciplinary team—including a nurse, therapist, social worker, and the center director—conduct an assessment to identify an individual’s needs. The CBAS center staff are required to contact the consumer’s physician to obtain the individual’s medical history and conduct an in–home visit to evaluate the individual’s home environment.

- Step Three: Development of Individual Plan of Care (IPC). The CBAS center’s multidisciplinary team develop an IPC specific to CBAS for an individual, which is submitted to the managed care plan.

- Step Four: Authorization by Managed Care Plan. The managed care plan reviews the IPC and provides authorization for six months of CBAS, with reauthorization for an updated IPC required every six months.

Standardized Eligibility Determination Collects Information on Medical and Functional Needs. The CEDT determines eligibility for CBAS by collecting information related to an individual’s medical and functional needs. It requires the nurse determining eligibility to collect information in the following areas: medical diagnoses, medications, assistive/sensory devices, a bodily systems review, cognitive and behavioral factors, medication management, recent health care encounters, and information about additional services and supports (including whether the individual receives IHSS, MSSP, hospice services, home health services, physical therapy, home–delivered meals, and/or other services). Further, the CEDT assesses functional needs for 12 ADLs and IADLs, relying on a binary yes–or–no response as to whether the applicant can perform each task independently, in contrast to the IHSS five–point scale for assessing functional ability.

CBAS Centers Do Not Use a Standardized Assessment. The CBAS centers are not mandated by the state to use any specific assessment tool when conducting their multidisciplinary team assessment of an individual’s needs—the second step in the four–step eligibility determination and assessment process. However, the California Association for Adult Day Services has recently released a web–based standardized assessment tool to seven pilot sites.

MSSP Assessment Process

Standardized MSSP Assessments Collect Information on Medical Needs, Functional Needs, and Consumer Characteristics. For MSSP, a nurse care manager and a social worker care manager determine eligibility and case management needs based on assessments of medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics. The initial health assessment is conducted by an MSSP nurse care manager and collects information in the following areas: medical diagnoses, medications, nutrition, health habits, a bodily systems review, as well as mobility and psychiatric questions.

The assessment conducted by an MSSP social worker care manager collects information in the following areas related to consumer characteristics: living arrangements, occupational history, activities and interests, finances, family and social network, safety of the client’s living arrangements, and psychological functioning. This assessment also includes an assessment of functional needs for 17 ADLs and IADLs, which relies on a five–point scale—similar to IHSS—to identify an individual’s level of impairment. Further, this assessment asks clients about services they received in the last month (prior to receiving MSSP), including the number of IHSS hours, transportation services, meal services, day care services, or other services. The social worker care manager also conducts an assessment of cognitive functioning.

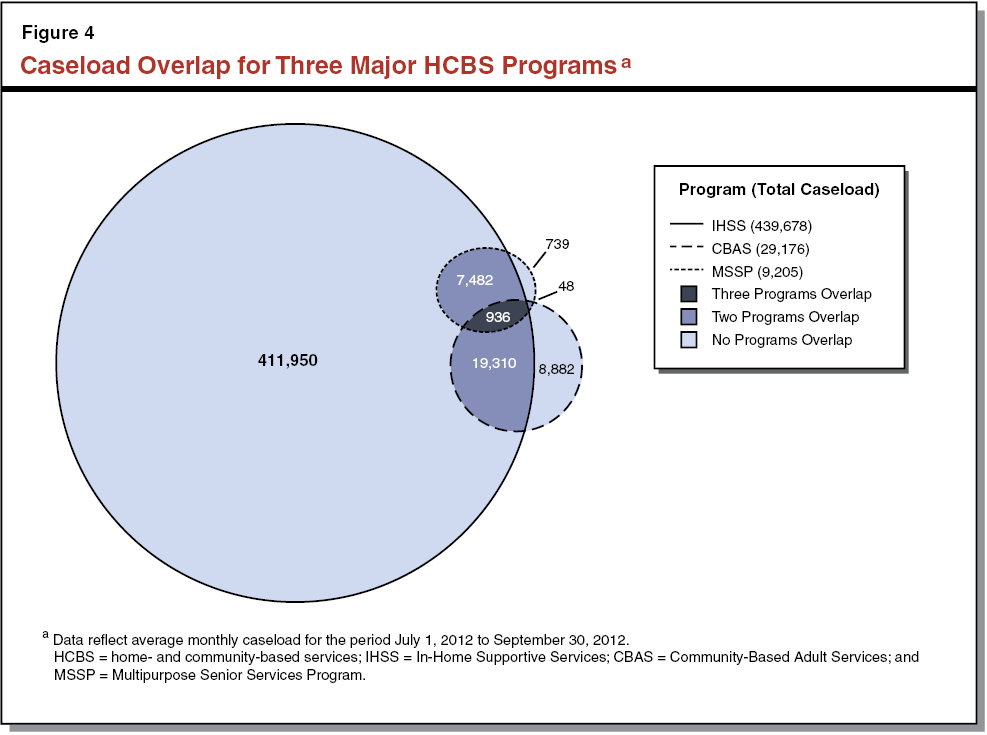

While the vast majority of HCBS recipients statewide only receive IHSS, about 28,000 of these recipients receive services from more than one HCBS program, as shown in Figure 4. Because clients benefitting from more than one HCBS program are likely to be at risk of—or eligible for—SNF placement, these 28,000 individuals can be considered “higher–risk” clients. For purposes of this report, we broadly define higher–risk clients as individuals for whom the better coordination of medical care and HCBS could delay or avert a SNF placement. Typically, these are individuals who have multiple chronic medical conditions and/or severe functional impairments. Conversely, we define “lower–risk” clients as individuals who have medical conditions that are not as complex in nature and/or functional impairments that are not as severe as higher–risk clients and who therefore would be less likely to benefit from coordination of medical care and HCBS.

The state’s current HCBS assessment system has two shortcomings. First, the current approach creates administrative inefficiency in that duplicative assessments are administered to frail elderly clients. Because each HCBS program conducts its own assessment, assessors are forced to rely primarily on client–reported information at a single point in time, which may be inaccurate—particularly regarding the extent of the client’s utilization of other HCBS. Second, separate assessments and data systems for each HCBS program ultimately hinder the coordination of care for clients. We discuss these problems in detail below.

Separate Assessments for Each HCBS Program Creates Administrative Inefficiency and Burdens Clients

Separate eligibility determination and assessment processes for IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP create several forms of inefficiency in the administration of these HCBS programs: (1) higher–risk clients are burdened with multiple assessments collecting duplicative information; (2) assessors may be authorizing services based on an inaccurate understanding of HCBS utilization; and (3) three separate data systems are maintained, further increasing costs and inefficiencies.

Duplicative Information Is Collected by IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP Eligibility Determinations/Assessments. For clients receiving more than one HCBS program, the state–developed tools—including the IHSS and MSSP assessments and the CBAS eligibility determination tool—collect duplicative information. The most glaring example of this duplication is the determination of functional needs, which is conducted by assessors for all three programs. Figure 5 displays the duplicative information collected by these three instruments. For consumers eligible for more than one program—typically frail elderly individuals—multiple lengthy assessments containing repetitive questions may be burdensome and potentially a deterrent to seeking needed services. Further, a separate assessment for each program may lead to inconsistent determinations of a client’s needs, calling into question the reliability of each individual assessment. For instance, an assessor for one program could potentially identify greater functional needs than the assessor from another program.

Figure 5

Duplicative Information Collected by IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP Eligibility Determinations/Assessments

|

Collected by IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP

|

Collected by IHSS and MSSP

|

Collected by CBAS and MSSP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Determination of functional needs

|

|

|

- Alternative resources or other HCBS received

|

|

|

Assessors May Be Authorizing Services Based on an Inaccurate Understanding of HCBS Utilization. In the existing HCBS assessment system, assessors for each program are primarily dependent upon the consumer to accurately report the formal services and supports he/she receives from other HCBS programs. As we note in Figure 5, the IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP eligibility determinations/assessments each seek information on other forms of assistance (referred to as “alternative resources” for IHSS) currently being provided to a consumer through other programs and services. However, several county IHSS administrators reported to us that IHSS recipients and applicants may not be able to provide reliable information about the alternative resources they receive. Specifically, county IHSS administrators in several counties reported to us that they did not know the actual extent to which IHSS recipients were receiving ADHC (prior to the transition to CBAS) until the state released this information to counties on a one–time basis in 2011. Alternatively, it is possible that IHSS recipients and applicants may overstate the formal assistance they receive from other HCBS programs, thereby causing the county social worker to authorize less assistance than is warranted. Such inaccurate self–reporting of HCBS utilization can occur during assessments for all three HCBS programs. Therefore, the assessment model of relying on consumers to disclose alternative resources or other HCBS they receive may not adequately capture the information necessary to conduct an accurate assessment of service needs for higher–risk clients. In the case of unreported ADHC (now CBAS) among IHSS recipients and applicants, the county social worker is likely authorizing service hours for tasks for which the consumer already receives assistance through CBAS.

Even when clients are able to accurately report the alternative resources or other HCBS they receive, assessors or care managers are limited to an understanding of a client based on a single assessment at a single point in time. For an IHSS recipient, for instance, the county social worker would not come to know of a change in CBAS utilization that occurred after an IHSS assessment. Unless the recipient requests an earlier reassessment, the authorization of service hours from the initial IHSS assessment would likely be left unchanged—despite the change in CBAS utilization—until the next annual IHSS reassessment. Ultimately, assessors may be authorizing services based on an inaccurate understanding of a client’s total HCBS utilization.

Separate Data Systems to Store Client Assessment Data Hinders Efficiency of Care Coordination. Each of the three major HCBS programs stores clients’ assessment information in its own data system(s). For IHSS, the Case Management, Information and Payrolling System (CMIPS) II data system stores information about clients’ authorized service hours. The CBAS centers and MSSP sites use various data systems to store information about participants gathered during the assessment process. These data systems are not compatible with each other, making it difficult for assessors or care managers to easily and efficiently track the other HCBS delivered to a client or to view relevant information collected by assessors for other programs. In the absence of a formal data–sharing arrangement among HCBS programs, we find that the ability to coordinate the long–term care of clients suffers, an issue to which we now turn.

Current HCBS Assessment System Hinders Ability to Coordinate Long–Term Care for Clients

Comprehensive HCBS Record Not Available for Clients Who Access Multiple HCBS Programs. A comprehensive HCBS assessment record is a single electronic source that includes relevant information on certain medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics. There is currently no single data depository that can be accessed to retrieve comprehensive HCBS assessment information for clients receiving services from more than one program. A comprehensive HCBS assessment record would ensure that assessors or care managers have an accurate understanding of a client’s medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics as well as HCBS utilization over time, which would likely improve the coordination of care for clients. For example, the MSSP care manager—who makes monthly telephone calls to MSSP clients—may come to learn from that phone call that a client has been hospitalized, leading the care manager to adjust services as needed and document both the hospitalization and the adjustment of services in the comprehensive record so as to be available to all assessors and care managers involved in the individual’s care.

Available Information Does Not Use Standardized Data Elements. Even if the existing HCBS assessment information were to be collated, we note that data elements are not standardized across programs. Consider the determination of functional needs that is conducted by all three major HCBS programs. The programs do not use a standard set of ADLs and IADLs when evaluating functional needs. For instance, the MSSP assessment determines a consumer’s ability to use the telephone while the IHSS assessment and CEDT do not. Further, the rating to describe the level of functional impairment is not standardized across all three programs. The CEDT relies on a yes–or–no response as to whether the applicant can perform each task independently while the IHSS and MSSP assessments both rely on the five–point scale displayed in Figure 3. These inconsistencies may make it difficult for an assessor or care manager to interpret the actual needs of a client who is receiving services from more than one HCBS program. Standardized data elements could also help state policymakers better understand how the needs of recipients compare across programs.

Onus Is on Clients to Manage Their Long–Term Care. As a consequence of the fragmentation in the administration of HCBS programs and the consequential lack of a comprehensive HCBS assessment record, the responsibility for care coordination in the current HCBS framework appears to lie with clients and/or their caregivers. This onus on clients to manage their long–term care is problematic because many clients, who may have disabilities, mental illness, and/or cognitive impairments, will likely face major challenges in doing so. The lack of care coordination is also troubling because it potentially leads to poorer outcomes among higher–risk clients, such as avoidable hospitalizations and SNF stays.

CCI Integrates Delivery of Medical Care and LTSS for SPDs

Addressing a Fragmented Health Care System for SPDs. Generally, SPDs are more expensive to serve than other Medi–Cal beneficiaries because of the higher prevalence of complex medical conditions and greater functional needs within this population. The high cost of SPDs may be exacerbated by the fragmentation of care under a system in which Medi–Cal FFS, Medi–Cal managed care, and Medicare function in silos. (Medicare is the federal program that provides health care services to qualifying individuals over age 65 and to certain persons with disabilities.)

This fragmented delivery system has contributed to a lack of coordination of services for SPDs and an incentive for each program to shift costs to other programs. For example, Medi–Cal FFS has historically paid for the majority of LTSS (including HCBS) costs for “dual–eligible” beneficiaries—that is, beneficiaries eligible for both Medi–Cal and Medicare. However, Medi–Cal pays a relatively small portion of acute medical care costs, such as hospitalizations, for dual eligibles. (Medicare pays for most physician, hospital, and prescription drug benefits for dual eligibles, with Medi–Cal covering a smaller portion of these costs—known as “wraparound coverage.”) Therefore, the state has had limited financial incentive to provide additional HCBS that would potentially reduce acute care utilization for dual eligibles, since the savings that would have resulted from avoided hospitalizations would largely have accrued to the federal government, which funds Medicare. The CCI, which is authorized to be piloted in up to eight counties, tests a different delivery model to address the problems with the existing fragmented health care system for dual eligibles and SPDs covered only by Medi–Cal. We describe the CCI in more detail below.

The CCI Has Three Main Components; Requires Development of a UAT. The CCI, which began April 1, 2014, includes three interrelated components that broadly seek to integrate medical care and LTSS into managed care plans in up to eight counties statewide. These components include: (1) the mandatory enrollment of dual eligibles—with certain exceptions—into managed care plans for their Medi–Cal services, (2) the integration of Medicare benefits into the Medi–Cal managed care plan for dual eligibles under a three–year “duals demonstration” project, and (3) the shift of LTSS from Medi–Cal FFS to managed care plan benefits for most SPDs—both dual eligibles and Medi–Cal–only SPDs. By integrating LTSS (IHSS, CBAS, MSSP, and SNF care) into managed care plans, the intent is to give plans a financial incentive to better coordinate care for beneficiaries and rebalance toward HCBS programs and away from costly SNF stays and avoidable hospitalizations. The authorizing legislation for the CCI—Chapter 33, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1008, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) and Chapter 45—also includes provisions that require the development and pilot implementation of a UAT as well as data–sharing agreements between managed care plans and HCBS administrators. (Please see our report, The 2013–14 Budget: Coordinated Care Initiative Update, for further background on the CCI.)

CCI Requires Managed Care Plans to Assess Health Risks of SPDs and Coordinate Care for Higher–Risk Beneficiaries. The CCI requires managed care plans to conduct a brief health risk assessment either in person, by telephone, or by mail for all new beneficiaries. Further, managed care plans must also use historical health utilization data in order to identify SPDs enrolled in the plan who likely have a higher–risk of experiencing an adverse health outcome or a worsening of their health or functional status. For dual eligibles and Medi–Cal–only SPDs found to be at higher–risk, managed care plans are required to develop a care plan that coordinates programs and services delivered by other entities, such as county welfare departments for IHSS. Even though IHSS is becoming a managed care plan benefit in the CCI counties, we note that Chapter 33 specifies that county social workers will continue to conduct assessments for IHSS to determine the number of service hours to be provided to IHSS recipients. We also note that, under the CCI, MSSP will transition to a managed care plan benefit—with plans granted full authority to provide case management services similar to MSSP to consumers.

CCI Authorizes Development and Pilot Implementation of UAT. Chapter 45 requires DSS and CDA to convene a stakeholder workgroup to develop the UAT for IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP. (The DHCS is also involved in the stakeholder workgroup.) The workgroup includes the following stakeholders: consumers of IHSS and other HCBS programs, representatives of managed care plans, representatives of county welfare departments, CBAS and MSSP providers, health care professionals, advocates, union representatives, and legislative staff. The workgroup is required to build on the IHSS assessment process and hourly task guidelines, the MSSP assessment process, and other appropriate home– and community–based assessment tools. Chapter 45 requires that the UAT be piloted in two to four of the CCI counties. (Consumers in those counties will have the option to be assessed using the UAT and using the previous assessments for IHSS, CBAS, and/or MSSP.) Expanded use of the UAT—to more counties or statewide—would require a statutory change. Figure 6 enumerates the issue areas for the stakeholder workgroup to consider, as specified in Chapter 45.

Figure 6

Issue Areas for UAT Stakeholder Workgroup to Consider

|

|

- Roles and responsibilities of health plans, counties, and HCBS providers.

|

- Criteria for reassessment.

|

- How results of new assessments would be used for oversight and quality monitoring of HCBS providers.

|

- How the appeals process would be affected by the assessment.

|

- Ability to automate and exchange data and information between HCBS providers.

|

- How the universal assessment process would incorporate person–centered principles and protections.

|

- How the UAT would meet the goals of the duals demonstration.

|

- Qualifications for, and how to provide guidance to, the individuals conducting the assessments.

|

- How the UAT may be used to assess the need for nursing facility care and divert individuals from nursing facility care to HCBS.

|

HCBS Data Sharing Under the CCI

As noted earlier, there has been no systematic data sharing among HCBS programs and consequently no comprehensive HCBS assessment record on which assessors and care managers can rely to coordinate the long–term care of clients. While the CCI does include provisions that require HCBS administrators to share data with managed care plans, as described below, the data provided to managed care plans is delivered piecemeal by each HCBS administering entity and often with a time lag. Consequently, there continues to be no single, up–to–date HCBS assessment record that is accessible to assessors and care managers.

DSS Sharing IHSS Data With Managed Care Plans in the CCI Counties. The DSS is providing managed care plans with information on the service hours delivered to IHSS recipients enrolled in the plan.

CBAS Data Sharing Remains the Same. The authorizing legislation for the CCI does not make any changes to the existing relationship between CBAS centers and managed care plans. (The CBAS centers will continue to submit individual plan of care forms to managed care plans, which will continue to authorize CBAS on a six–month basis.)

MSSP Data Sharing With Managed Care Plans. Managed care plans have entered into agreements with MSSP sites to define roles and responsibilities and establish policies and procedures for sharing information and coordinating care.

We find that Chapter 45 provides an appropriate framework for the stakeholder workgroup to consider as it develops the UAT. Below, we discuss the benefits of universal assessment for HCBS.

Benefits of Universal Assessment for HCBS

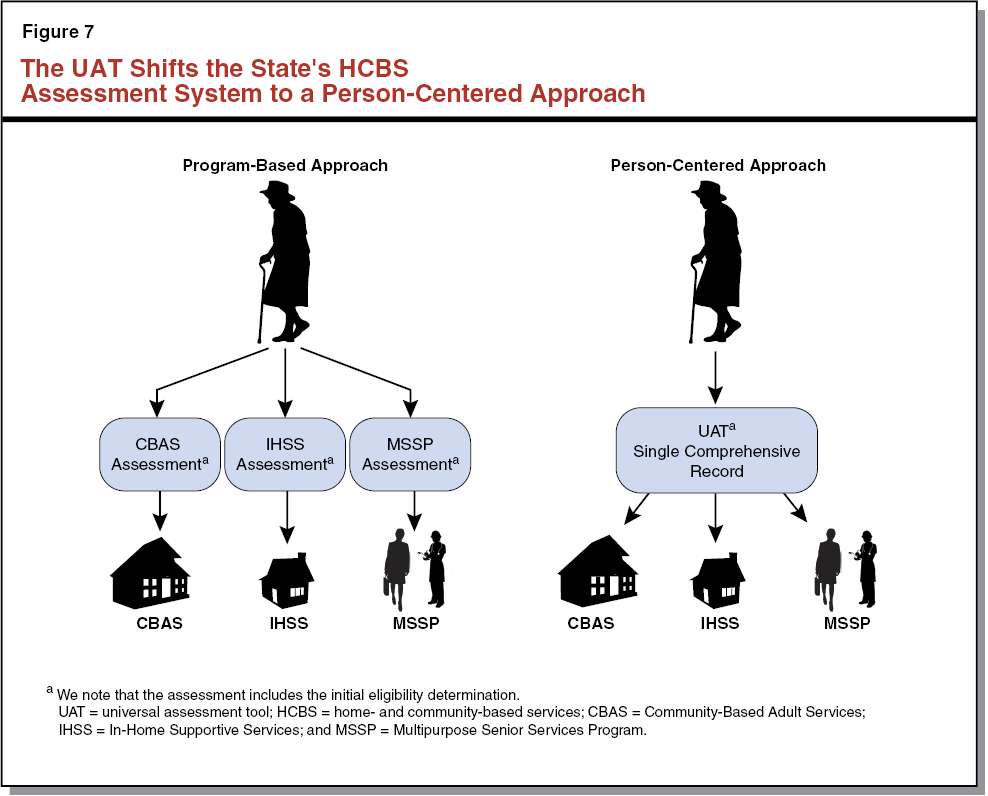

The historical HCBS framework has been reliant on a program–based approach in which assessors focus on eligibility and an assessment for a particular program, which can create administrative inefficiency and may not fully meet the needs of the individual assessed. For instance, a higher–risk consumer may require both IHSS and MSSP to remain safely in his/her home, but would not necessarily be assessed for both programs under the current framework. If the UAT meets the principles established in Chapter 45, then it would shift the existing HCBS framework from a program–based approach to a person–centered approach—that is, an approach that seeks to broadly collect information on a consumer’s characteristics as well as his/her medical and functional needs and then develop an HCBS care plan that authorizes the amount and type of HCBS the consumer is eligible to receive. Figure 7 displays the shift from a program–based approach to a person–centered approach to assessment—enabled by the UAT. Next, we enumerate the benefits of this person–centered approach to HCBS assessment.

UAT Creates Single HCBS Assessment Record

As discussed earlier, the current program–based approach to HCBS assessment does not establish a comprehensive HCBS record or use standardized data elements. Over time, the UAT creates a single comprehensive HCBS record that can be accessed by assessors and care coordinators. Ideally, this record would eventually be compatible with an individual’s electronic medical record to create a single repository of reliable medical and long–term care information. Such data could be accessed by a care coordinator for (1) higher–risk consumers who require ongoing care management and (2) lower–risk consumers who may require an adjustment to their HCBS care plan. For instance, a care coordinator affiliated with a managed care plan could use such an HCBS record to quickly track medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics when an individual is undergoing a care transition, such as a discharge from the hospital or a SNF, and make a determination about the adequacy of the existing HCBS care plan.

UAT Can Help to Improve Care Coordination

As we note in our previous discussion of the CCI, Chapter 33 requires managed care plans to conduct a health risk assessment for all new beneficiaries and to coordinate care—possibly through teams—for beneficiaries found to be at higher risk of an adverse health outcome or a worsening of their health and functional status. We define care coordination as a process in which an individual is assessed to identify his/her needs, a comprehensive care plan is developed, and services are managed or monitored by a care coordinator.

UAT Can Systematically Identify Consumers’ HCBS Needs to Ensure the Right Care Is Delivered at the Right Time. The UAT supports the goals of the CCI by identifying an individual’s HCBS needs in a systematic way that can improve care coordination. Research studies have found that coordinating care and providing needed HCBS for higher–risk patients during care transitions, such as a transition from a hospital to the home, can reduce re–hospitalizations. The UAT can serve to enable this outcome. For instance, the UAT could be used at the point of discharge to identify immediate care needs by including the following assessments: ability to manage a medication regimen, determination of functional impairments, need for case management services (such as a nurse coach), and barriers to keeping follow–up appointments (such as unreliable transportation). Once these needs have been systematically identified by the UAT, the HCBS care plan would ensure that the individual received needed HCBS on a timely basis—particularly in the critical four to six weeks after discharge. As such, the UAT could ultimately help reduce re–hospitalizations and possibly help delay or avert SNF placements. In this sense, the UAT can be understood as supporting the broader goal of delivering coordinated care to beneficiaries.

Care Coordination Shown to Reduce Emergency Room (ER) Use and Hospitalization Among Dual Eligibles—A Case Study. The ability of the UAT to improve care coordination is important because of the role effective care coordination can play in reducing costly ER visits and hospitalizations. The Health Plan of San Mateo (HPSM)—the countywide health care plan for Medi–Cal beneficiaries in San Mateo County—found a significant reduction in ER use and hospitalizations among dual eligibles receiving the types of care coordination shown to be effective in research studies. The evaluation was conducted in 2008 among more than 800 dual eligibles enrolled in HPSM’s special needs plan—a plan exclusively for dual eligibles that is required to have interdisciplinary care teams that coordinate Medicare services. The evaluation found the percentage of dual eligibles with at least one hospitalization dropped from 31 percent to 17 percent among beneficiaries once receiving care coordination. Similarly, the percentage of dual eligibles with at least one ER visit declined from 43 percent before care coordination to 30 percent after care coordination. The evaluation found no change in ER use and hospitalizations among beneficiaries not receiving care coordination services over the same period. The forms of care coordination delivered to these dual eligibles included such services as a nurse coach to educate hospitalized patients about their condition, a nurse who follows up with patients after discharge from the hospital, and a doctor who conducts home visits and is always accessible by cell phone for the highest–risk beneficiaries. As discussed above, the UAT can facilitate effective care coordination by identifying an individual’s HCBS needs in a systematic way.

UAT Reduces Administrative Inefficiencies And Enhances Consumer Choices

In addition to the improved care coordination that can result from implementing the UAT, the administrative inefficiencies of the current program–based approach to assessment would also dissipate. An assessor would visit the client to conduct an assessment that collects information on medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics, requiring a single data system to store client information. The potential use of technology, such as a laptop or tablet computer, to conduct the UAT in the field could further streamline the administrative process. (Recall that the current assessment process is mostly reliant on paper assessment forms unique to each program.) With the use of such technology, assessors would no longer need to input assessment information collected through a paper tool into a data system. Further, a computer–based UAT could be designed to skip questions that were irrelevant to a particular individual based on answers to previous questions, further streamlining the assessment process for consumers. For medically complex cases, a computer–based UAT could be designed to become more detailed—with the initial social worker assessor potentially handing off the assessment to a nurse assessor who could determine eligibility for CBAS and/or MSSP.

By streamlining the assessments for three HCBS programs into a universal assessment, the administrative efficiencies of the UAT would also enhance consumer choices. Clients who qualify for more than one program would be able to learn about their HCBS options at the time of their universal assessment and share their long–term care preferences with assessors.

Data Collected by the UAT Can Be Analyzed to Improve Long–Term Care

We noted earlier that CCI requires entities that administer HCBS to share relevant client information with managed care plans. The current HCBS data elements are not standardized nor are they stored in a single data system. However, over time, the UAT would collect comprehensive long–term data on consumers receiving HCBS, including standardized data elements to identify medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics.

Managed Care Plans, County Welfare Departments, and Other HCBS Providers Could Use UAT Data to Better Understand Clients. For managed care plans, data collected by the UAT may provide useful information for statistical modeling conducted to make predictions about beneficiaries’ level of health care utilization. Plans generally conduct predictive modeling to identify those beneficiaries who are likely to be high health care utilizers, and health care providers may deliver targeted care coordination services to these individuals. For county welfare departments and other HCBS providers, comprehensive data collected by the UAT can provide valuable information for care managers and for assessors conducting a reassessment of an individual’s medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics.

Lessons for California From Existing UATs

At the time of this analysis, some version of a UAT is already in use or is being developed by more than half of states nationwide. The design of a state’s UAT can vary, and it is helpful to think of the possible options on a continuum. At one end of the continuum would be an “off–the–shelf” assessment tool with limited ability to be modified to fit within a state’s specific programmatic and policy environment. At the other end of the continuum would be a UAT built from scratch for a specific state. Between these two extremes, a state could adopt an off–the–shelf assessment tool with a greater capacity to be modified to fit within the state’s programmatic and policy environment. Or, a state could adopt a customized tool that leverages aspects of existing assessment–related tools, processes, and data systems, rather than building a tool from scratch. Typically, a tool would either need to be customized or built from scratch to have the functionality to directly determine eligibility and service needs for a state’s HCBS programs, reflecting the fact that each state’s environment for its HCBS programs is somewhat unique. We refer to such customized tools as “state–specific.” Meanwhile, off–the–shelf assessment tools—unless modified—generally provide data that only assist with determining eligibility and service needs for a state’s HCBS programs. In this sense, off–the–shelf assessment tools with limited ability to be modified are not fully “UATs,” as defined in this report and in Chapter 45, since these tools, at best, assist with—rather than directly provide—eligibility determinations and authorization for the amount and type of services needed for multiple HCBS programs.

In the nearby box we provide two case studies—from Washington State and San Mateo County—which showcase the benefits and trade–offs of two distinct approaches to universal assessment. In Washington, the UAT was customized for the state, leveraging aspects of existing assessments. In San Mateo County, the assessment was an off–the–shelf tool with limited ability to be modified. These two case studies illustrate the relative policy merits of an automated state–specific tool when compared to other assessment options. Even though an automated state–specific tool would have higher development costs than an off–the–shelf assessment tool, this cost can be mitigated to some degree by leveraging aspects of existing assessment tools. In both Washington and San Mateo, we note that the assessments are automated and are designed to be administered using a laptop computer. As such, assessors can achieve certain efficiencies, such as recording assessment information directly into the computer–based tool and being able to easily retrieve data for analytical or care management purposes.

Two Distinct Approaches for a UAT

Washington State: Customized UAT

By leveraging aspects of existing assessment tools, Washington was able to develop a customized tool at a lower cost than a tool built from scratch. (The total initial development costs were less than $10 million.) Washington’s universal assessment tool (UAT)—known as Comprehensive Assessment Reporting Evaluation (CARE)—is based on Oregon’s tool. Both the Washington and Oregon assessment tools are derived from the Minimum Data Set—the federally mandated tool used to assess individuals receiving skilled nursing facility care. The Minimum Data Set utilizes a core set of data elements that have been shown over time to be reliable in assessing the medical, functional, psychological, and social needs of consumers in a standardized fashion. These standardized data elements provide a uniform language for understanding consumers’ varied needs, thereby promoting reliability in assessment results and enhancing a tool’s data analysis capabilities. Since it was implemented in 2003, the CARE tool has amassed data that can be used to better understand the Medicaid population receiving home– and community–based services (HCBS) and to target care coordination services to high–cost clients.

Customized UAT Is Inherently Designed to Be State–Specific and Flexible, Thereby Broadening Its Potential Use and Streamlining the Assessment Process. Washington’s CARE tool is designed to rely on computer algorithms—or, calculation procedures—to determine eligibility and the authorized number of hours for personal care services as well as eligibility and level of need for other HCBS offered in the state. In this way, the CARE tool is designed to fit within the unique programmatic and policy environment of the state in which it is used. The CARE tool also has the flexibility to incorporate additional standardized screening measures, such as a screening for depression, or to include questions related to additional state programs and services, such as those serving individuals with developmental disabilities. In this way, the uses of the CARE tool have broadened over time, further streamlining the eligibility and assessment process in the state. As an automated tool, CARE prompts assessors to ask new questions based on answers to previous questions—another example of how the tool has been used to streamline the assessment process by only asking questions that are relevant to a particular consumer. For the initial eligibility determination and assessment, the CARE tool is administered by state–employed social workers. For medically complex cases, assessors may consult a state nurse, who may accompany the assessor during an in–home assessment or simply review the case.

Customized UAT Takes Time and Financial Resources to Develop. Even though the CARE tool leveraged aspects of existing assessment tools, it still took five years to design and test and required several million dollars in upfront development costs. As a customized tool, extensive testing was required to ensure that the algorithms were operating as intended. However, when compared to a tool built from scratch, a customized tool that relies on aspects of existing assessment tools can mitigate some of the cost and time required for development.

San Mateo County: An Off–the–Shelf Assessment Tool With Limited Ability to Be Modified

In 2008, San Mateo County Aging and Adult Services (AAS) began using an off–the–shelf assessment tool, known as interRAI–Home Care (or, interRAI–HC), to assess needs for In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS), Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP), and other AAS programs. The InterRAI is a collaborative network of researchers that has developed a suite of assessment instruments for a variety of health care settings—available for free in exchange for entities sharing data for InterRAI’s research purposes. Like the CARE tool used in Washington, the interRAI–HC assesses consumers using a core set of data elements that yield standardized results. However, because InterRAI seeks to analyze these data, this particular off–the–shelf assessment cannot be customized to meet the specific needs of the entity administering the tool.

Tool Lacks State–Specific Information Needed to Determine Eligibility and Authorize Services for Multiple HCBS Programs. Because the interRAI–HC is an off–the–shelf assessment tool with limited ability to be modified, its assessment of functional needs cannot be changed to include California’s IHSS assessment process. Ultimately, the tool was found to assess functional needs in a manner deemed inconsistent with existing state standards for IHSS. For this reason, the use of interRAI–HC for the purposes of assessing needs for IHSS was discontinued during San Mateo’s pilot use of interRAI–HC. At the time of this analysis, the interRAI–HC tool is administered by the MSSP social worker and nurse care managers and is used to assist in determining eligibility and identifying service needs only for MSSP. Accordingly, while the tool used in San Mateo does identify medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics, it is not a multiprogram UAT, even though San Mateo initially intended to use the interRAI–HC as a UAT for IHSS, MSSP, and other AAS programs.

Off–the–Shelf Assessment Tool Can Still Provide Some Useful Data on Consumers. The computer–based interRAI–HC provides standardized ratings on various “health scales” and “risk triggers” that can be useful to assessors and care managers. While these standardized ratings do not directly determine eligibility and the amount and type of services to authorize for California’s HCBS programs, they do provide valuable information to assessors and care managers. For instance, if a risk trigger for falls is identified for a consumer—and the consumer is eligible for MSSP—then the assessor or care manager may seek to ensure that MSSP provides a home modification, such as a handrail, to mitigate the fall risk.

Off–the–Shelf Assessment Tool Avoids Development Time and Some Costs, but Training Still Necessary. In adopting an off–the–shelf tool with limited ability to be modified, San Mateo avoided the time and fiscal risks associated with developing a customized tool, while still gaining some useful data on consumers. However, as noted, this came with the major trade–off of the tool not being able to serve as a multiprogram UAT. The San Mateo experience also illustrates that the use of any new assessment requires that assessors are trained in how to administer the tool. A 2009 evaluation of San Mateo’s pilot use of the interRAI–HC tool found that implementation of the tool was hindered by the fact that social worker assessors did not receive adequate training in collecting detailed medical information and in using laptops in the field to administer the tool.

We have discussed the benefits that a UAT affords in terms of creating a single HCBS assessment record that could facilitate better care coordination that can, in turn, reduce hospitalizations and delay or avert SNF placements. The UAT also provides the benefits of reducing administrative inefficiencies, enhancing consumer choices, and improving data analysis capabilities. By authorizing the development of a UAT in Chapter 45, the Legislature has recognized the policy merits of universal assessment for HCBS. However, a UAT is not without significant upfront development and ongoing implementation costs. These costs can vary widely, depending on whether the tool is automated or paper–based and, if automated, whether it is off–the–shelf, customized, or built from scratch. Accordingly, we address these issues and then related development and implementation costs.

Automated UAT Specific to California Makes Sense

The UAT’s design would need to balance the dual goals of (1) creating a comprehensive assessment of medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics, and (2) ensuring a streamlined process so that consumers are only asked questions that are necessary for determining eligibility and identifying their particular needs. Reaching consensus among varied stakeholders on the particular standardized ratings and other questions to include in the UAT could complicate this design process, since each HCBS program currently utilizes its own unique approach to identifying consumers’ needs. While the stakeholder workgroup tasked with developing the UAT is contemplating design issues, we think that the workgroup could benefit from further legislative guidance where Chapter 45 is not definitive.

Automated State–Specific UAT Maximizes Benefits of Effectiveness and Efficiency. While Chapter 45 specifies that the UAT should build on various existing HCBS assessment tools, it does not explicitly mention the adoption or creation of an automated tool. We find that the flexibility potentially afforded by an automated tool offers benefits and efficiencies not available with a paper–based tool. Earlier, we describe the automated tool used in Washington State, which prompts assessors to skip questions that may be irrelevant to a particular consumer and stores clients’ assessment data in one place. This case study and other research lead us to conclude that an automated tool can maximize a number of the benefits of a universal assessment in terms of improving the efficiency of the assessment process and establishing a single HCBS assessment record. If an automated tool is chosen, then a secondary decision should be made about the type of automated tool to be developed—ranging from an off–the–shelf tool with limited ability to be modified to a tool built from scratch. We find that some degree of customization is needed in order for California’s UAT to streamline eligibility determinations and authorization of services for the state’s HCBS programs. An off–the–shelf assessment with limited ability to be modified is therefore not a practical option for California. One key design feature enabled by automation is the ability of the universal assessment to be tailored to the varied needs of consumers—described further below.

Automated UAT Could Be More Streamlined for Lower–Risk Consumers. In the context of CCI, in which managed care plans rely on health utilization data and a health risk assessment to determine whether an individual is at higher– or lower–risk for future health and/or long–term care utilization, it may not be necessary for consumers identified as lower–risk to undergo as detailed an assessment through the UAT as higher–risk consumers. For these lower–risk consumers, an automated UAT has the potential to be streamlined so these individuals are asked initial questions to screen for medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics and—triggered by answers to the initial screening questions—undergo a detailed assessment only in necessary areas. For a large portion of the IHSS caseload that is medically stable, we anticipate that such a UAT would primarily assess their functional needs.

Automated UAT Could Be More Detailed for Higher–Risk Consumers. For individuals determined by managed care plans to be at higher–risk for health and/or long–term care utilization, the initial UAT questions to screen for medical needs, functional needs, and consumer characteristics would likely trigger a comprehensive assessment in all three areas. For medically complex cases, an initial social worker assessor may need to hand off the assessment to a nurse assessor who could assess medical needs more fully in order to determine eligibility for CBAS and/or MSSP. However, the assessment would still be streamlined in that multiple duplicative assessments would be avoided.

Significant Costs to Developing and Implementing an Automated State–Specific UAT

If the state pursues an automated UAT specific to California, then we anticipate significant costs related to the following: development of an Information Technology (IT) system; administrative costs for training, computers, and additional staff time; coordination among HCBS providers; and better identification of HCBS needs among consumers, potentially increasing demand and therefore costs for HCBS programs. The cost to develop an IT system can be mitigated somewhat by building on existing automated tools and data systems.

Development of an IT System Involves Costs. An automated UAT built from scratch would incur the costs and inherent fiscal risks of developing a large–scale IT system. For instance, the state’s experience in developing and implementing CMIPS II—the new web–based data system that stores information about an IHSS recipient’s authorized service hours and processes payments to IHSS providers—included delays and cost overruns. However, the state could look for opportunities to build on existing automated tools and data systems, such as the Comprehensive Assessment Reporting Evaluation (CARE) tool used in Washington, to potentially reduce the time and cost associated with building an automated tool primarily from scratch. As mentioned earlier, the total cost to develop the CARE tool was less than $10 million. While we recognize that California’s larger size and complexity would likely require higher development costs than in Washington, we think that Washington’s development costs can serve as a rough guide for California. By leveraging existing automated tools and data systems, the state could develop a UAT customized to fit within California’s programmatic and policy environment at a lower cost (and lower risk) than a tool built from scratch. Even then, this type of automated state–specific UAT could still likely take up to several years to develop and involve significant development costs. The state should also take into account costs associated with ensuring compatibility with CMIPS II and potentially other existing data systems relevant for HCBS programs.

Administrative Costs for Training, Computers, and Staff Time. By adopting an automated state–specific UAT, additional administrative costs would be incurred in order to train assessors in how to administer the assessment and operate the IT system. Other administrative costs include the cost of providing laptop or tablet computers to administer the UAT in the field as well as the additional staff time required to conduct a universal assessment of some consumers. (That is, for the majority of lower–risk consumers who may only receive IHSS, the UAT would likely collect some additional information—in the areas of medical needs and consumer characteristics—not included in the current IHSS assessment.)

Cost Implications for Enabling Coordination Among HCBS Providers. In order for an automated state–specific UAT to serve as a single comprehensive HCBS assessment record, assessors and care managers from county welfare departments, managed care plans, and CBAS centers would need to have access to the IT system in which the HCBS assessment record is stored. Providing and acting on such access to the HCBS assessment record would result in increased costs compared to the existing assessment approach.

Implementation of UAT Could Increase Demand for HCBS Programs, Thereby Increasing HCBS Costs. A person–centered approach to assessment removes administrative hurdles to accessing IHSS, CBAS, and/or MSSP, particularly for higher–risk consumers who may be in need of more than one program. As such, the UAT could potentially identify needs that previously would have gone unmet, causing the number of consumers receiving HCBS to increase. This would increase HCBS costs. (As discussed earlier, this could also reduce hospitalizations and SNF placements.) On the other hand, it is also possible that the UAT could identify unnecessary duplication of HCBS for consumers that leads to HCBS savings. The net fiscal effect on HCBS program costs is therefore uncertain.

Statewide Use of Automated State–Specific UAT Makes Sense

Similar to the benefits discussed, the costs associated with an automated state–specific UAT are significant, but difficult to quantify. However, we are of the view that, on balance, the benefits of a UAT likely outweigh its costs. In our view, the UAT pilot should be premised on the assumption that the UAT will eventually be used statewide. Absent this operating assumption, it would not make fiscal sense to incur the significant development costs associated with testing such a UAT. If the Legislature concurs with pursuing an automated state–specific UAT on a statewide basis, then there are some important implementation questions that could be addressed through the UAT pilot, as discussed below.

Here we discuss how the pilot could address the implementation issues of which entity should administer the UAT as well as the role and structure of an initial screening prior to administration of the UAT. While Chapter 45 does not specify any requirement for a formal evaluation of the pilot phase of the UAT, it does appear—in materials developed for the stakeholder workgroup—that a final report on the pilot is anticipated. However, lacking legislative direction on this matter, it is uncertain whether the report will include sufficiently robust analysis of implementation issues to adequately inform the Legislature as it considers how to expand use of the UAT.

Which Entity Should Administer the UAT?

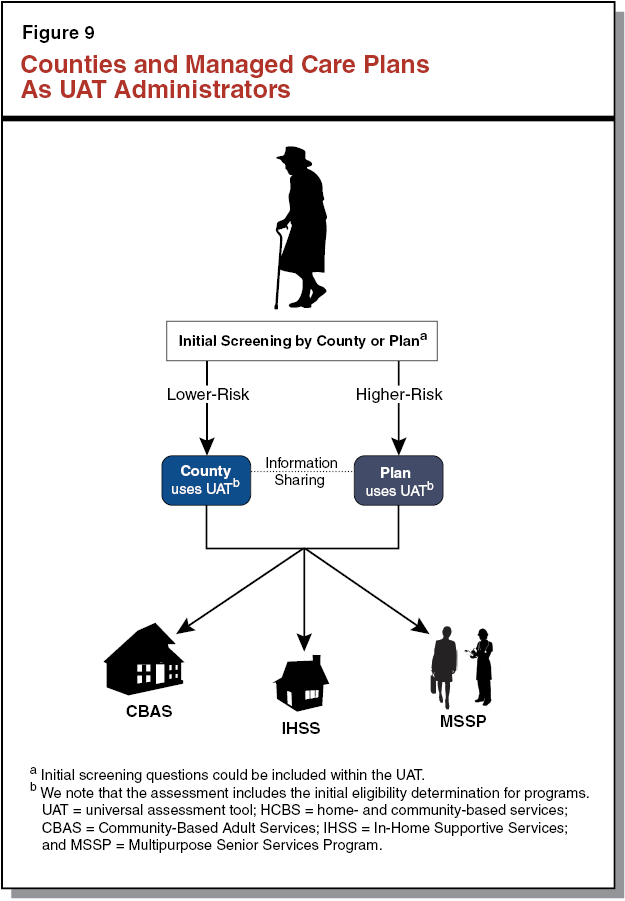

To fully realize the benefits of a UAT, it is necessary for the Legislature to establish a clear process for administering the UAT. In the context of the CCI, in which IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP are managed care benefits, we believe it is worthwhile to explore whether managed care plans should have some role in administering the UAT during its pilot phase.

Clear Process for Administering UAT Is Essential to Realizing Benefits of Universal Assessment. It is a major decision point for the Legislature to determine which entity will be responsible for administering the UAT—county welfare departments, managed care plans, a combination of these entities, or some other entity altogether—as Chapter 45 is silent on this issue. Failure to address this question of administrative process could potentially lead to adverse outcomes, such as administration of the UAT by assessors from the county welfare department and administration of similar assessments by managed care plans—an inefficient duplication that could be burdensome to consumers. In order to fully realize the benefits of the UAT, we find that county welfare departments and managed care plans will likely need to work collaboratively when assessing the needs of consumers for HCBS. For instance, in order to fully realize the benefits of the UAT to streamline the assessment process, information initially entered into the UAT by a county social worker would need to be available to a plan nurse who may need to complete the universal assessment in order to determine eligibility and assess needs for CBAS and/or MSSP for a higher–risk consumer. We recognize that such collaboration represents a significant cultural shift for entities that have historically not coordinated their efforts in this way.

Chapter33 Defines Role of County for IHSS Assessment, but Not for Universal Assessment. We note that Chapter 33 stipulates that county welfare departments will continue to be responsible for conducting IHSS assessments and authorizing service hours to be provided to IHSS recipients. Despite this provision that currently restricts administration of the IHSS assessment to county welfare departments, we believe it is worthwhile to consider options that would allow other entities to become involved in the administration of the UAT—a tool that would identify a broad array of needs ultimately leading to the provision of IHSS as well as CBAS and MSSP. We recognize that a statutory change would be needed to fully consider these options, such as involving managed care plans as administrators of the UAT. (As discussed below, we think that, depending on the level of health risk posed by a consumer, certain entities would be more appropriate UAT administrators than others.)

Criteria for Determining Which Entity Should Administer the UAT. It is a challenging implementation question to determine which entity should administer the UAT. As we have mentioned, this decision will likely determine the effectiveness of the UAT in streamlining HCBS assessment processes. For dual eligibles and Medi–Cal–only SPDs who receive all of their health benefits and LTSS from a single managed care plan, we believe it is worthwhile to assess which entity—the managed care plan or the county welfare department—is better suited to administer the UAT. We apply the criteria below in order to make this assessment.

- Access to Comprehensive Medical and Long–Term Care Data. Under what circumstances is comprehensive medical and long–term care data necessary for the assessor to conduct an accurate assessment? Which entity is best able to secure timely access to these data?

- Availability of Medical Expertise. Under what circumstances would medical expertise be needed to conduct an accurate assessment? Which entity is best equipped to provide this type of expertise?

- Financial Incentives of Entity. What are the appropriate financial incentives for the administering entity to have and which entity has such incentives?

- Familiarity With Models of Care. What models of care are important for the administering entity to have familiarity with, and which entity has such familiarity?

Initial Screening Could Be Used to Determine if Consumers Are at Higher or Lower Risk of Adverse Health Outcomes

In our consideration of which entity should administer the UAT, we find that the entity better suited to administer the tool varies based on whether the consumer is at higher or lower risk of experiencing an adverse health outcome. That is, it may make sense to enable one entity to administer the UAT to higher–risk consumers and a different entity to administer the UAT to lower–risk consumers. It appears to us that a consumer’s level of health risk is an indicator of whether the assessor would need to access medical and long–term care data as well as medical expertise in order to successfully complete the UAT.

In order to determine if consumers should be categorized as higher– or lower–risk, there are several options that could potentially be used.

- As we have noted, managed care plans are using health utilization data and a brief health risk assessment to determine if beneficiaries should be considered higher– or lower–risk—a process that could potentially be co–opted to help determine which entity should administer the UAT for a particular consumer.

- Another possibility is to include initial screening questions within the automated UAT to be used to determine if a consumer is higher– or lower–risk. As we have noted, this type of initial screening could also be used to help determine which areas need to be assessed more fully for a particular consumer—with lower–risk consumers undergoing a more streamlined process and higher–risk consumers undergoing a more detailed assessment.

- Alternatively, the initial screening could be done using a stand–alone tool that is separate from both the UAT and the process used by managed care plans.