Ballot Pages

A.G. File No. 2015-043

September 4, 2015

Pursuant to Elections Code Section 9005, we have reviewed the proposed constitutional and statutory initiative related to poverty reduction (A.G. File No. 15-0043 Amendment #1).

Background

Poverty in California. Poverty is generally defined as the condition of having insufficient means to achieve a minimum standard of living. The extent of poverty in California depends on how it is measured. The U.S. Census Bureau is charged with publishing poverty statistics for the nation and for states. Under the Census Bureau’s traditional, or “official,” poverty measure, about 17 percent of all Californians—more than 6 million people—are poor. Among children the state’s official poverty rate is higher, at 23 percent. In recent years, the Census Bureau has also published results from the Research Supplemental Poverty Measure, an alternative to the official poverty measure that more fully accounts for certain family circumstances such as receipt of public benefits and the cost of housing. Under this alternative measure, the state’s poverty rate is higher—with more than 23 percent of all Californians (about 9 million people) considered poor. About 27 percent of children in California are poor under the alternative poverty measure.

Poverty Associated With Numerous Negative Outcomes. Individuals in poverty tend to have lower skill levels and educational attainment, are less likely to be working, and have poorer health than the general population. Research suggests that poverty can have particularly negative effects on children, with children growing up in poverty at greater risk of poor academic achievement, behavioral and emotional problems, poor health, and remaining in poverty as adults.

Numerous Federal, State, and Local Programs Intended to Alleviate Poverty. Addressing poverty is a major objective of government. Federal, state, and local governments dedicate significant resources to funding various programs and services in California that are intended to address both causes and effects of poverty, some of which would be affected by this measure. Examples of programs intended to address poverty include concentrated state funding for school districts with large numbers of low-income students under the Local Control Funding Formula; free health coverage, cash and food assistance, housing vouchers, and subsidized child care for low-income individuals and families; and tax credits and education and training programs for low-wage workers. (Some of these programs are available to all qualifying individuals as an entitlement, while others have capped funding and are available on a limited basis.)

Overview of the Proposal

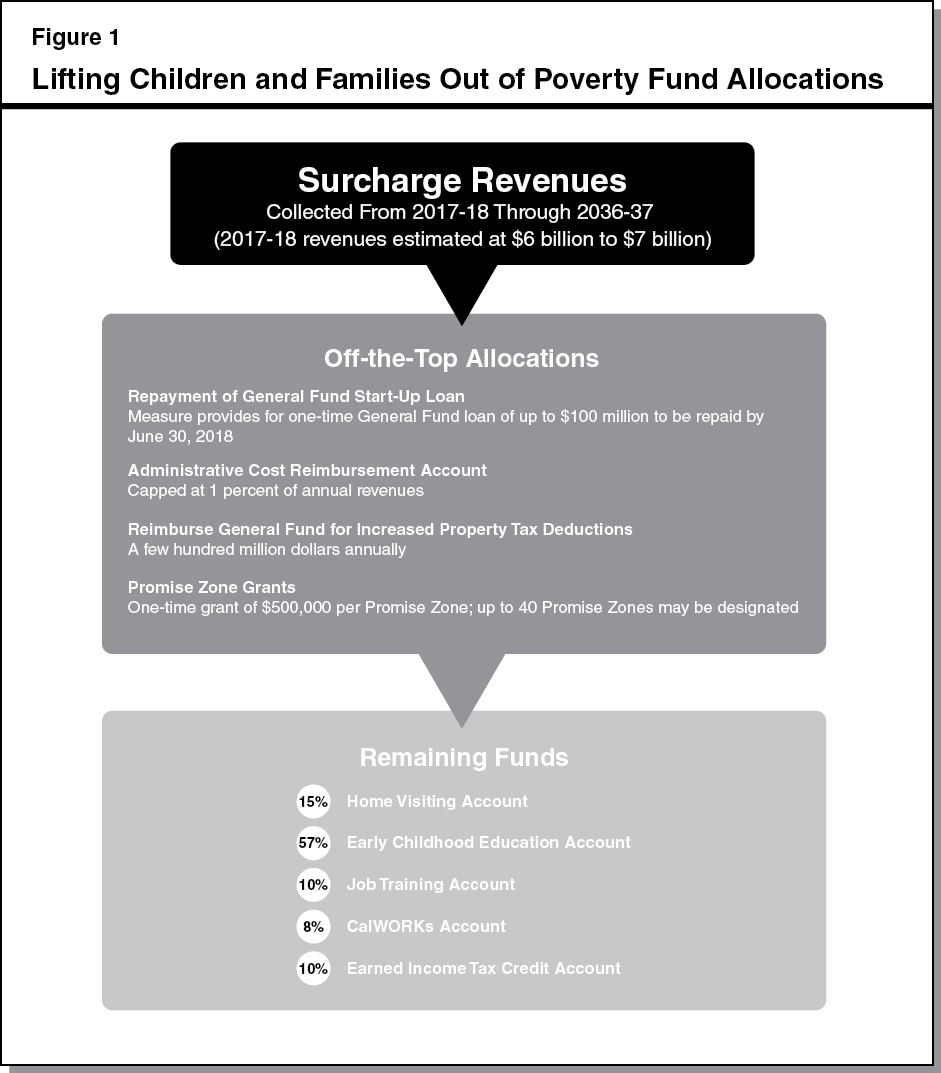

This measure enacts a surcharge from 2017-18 through 2036-37 on most properties in the state valued (for tax purposes) at above $3 million. This surcharge would raise between $6 billion and $7 billion in new revenues in 2017-18, with revenue amounts in future years generally expected to grow over time (in nominal terms). The measure deposits these revenues into a new special fund—the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund—and would dedicate the revenues to several programs intended to reduce poverty. These are: (1) the designation of certain areas of the state with high concentrations of poverty as “California Promise Zones” to facilitate coordination of anti-poverty efforts; (2) a significant expansion in home visiting programs that provide prenatal and early childhood services; (3) a significant expansion in government-subsidized child care; (4) the creation of a new sector-specific job training and tax credit program; (5) an increase to cash grants provided through the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program; and (6) a supplement to the California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a personal income tax (PIT) credit for low-wage workers. Figure 1 displays how surcharge revenues deposited in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund would be allocated across various accounts and subaccounts in order to fund the purposes described above. The remainder of this letter describes in greater detail the revenues that would be generated by the measure, the programs that would be funded with these revenues, and the possible indirect effects of the measure on the state’s economy and on state and local government finances. We conclude with a summary of the measure’s potential fiscal effects on state and local governments.

Raises Revenues From a New Surcharge

Background

Local Governments in California Levy Taxes on Property Owners. Local governments in California levy taxes on property owners based on a property’s assessed value, known as ad valorem property taxes. (For the remainder of the letter, ad valorem property taxes are referred to simply as property taxes.) The State Constitution limits, with narrow exceptions, the property tax rate to 1 percent of the assessed value of a property. Local governments, with voter approval, may raise the property tax rate only for two purposes: (1) to pay debt approved by voters prior to July 1, 1978 and (2) to finance bonds for infrastructure projects. The property tax raises around $55 billion each year.

California Taxes Individual Income and Corporate Profits. California levies a tax, known as the PIT, on the income of state residents, as well as the income of nonresidents derived from California sources. The PIT is the state’s largest revenue source, raising around $78 billion in 2014-15. California also levies a tax, known as the corporation tax, on the net income of corporations. The corporation tax is the third largest state General Fund revenue source, raising around $10 billion in 2014-15.

Property Owners Can Deduct Property Tax Payments From Taxable Income. State law allows property owners who itemize deductions to deduct property tax payments from their taxable income for the purposes of calculating PIT and corporation tax payments, effectively reducing their tax liability—the amount owed to the state.

Proposal

Increases Property Taxes On High-Value Properties. For 20 years beginning in 2017-18, the measure levies a surcharge on most properties with assessed values greater than $3 million. Property owners would pay an additional 0.3 percent on the portion of assessed values greater than $3 million and less than $5 million, 0.6 percent on the portion greater than $5 million and less than $10 million, and 0.8 percent on the portion above $10 million. These assessed value thresholds would be adjusted annually for inflation. The Legislature, under certain conditions, could increase the specified surcharge percentages up to a maximum rate of 1 percent. This action would require the approval of two-thirds of the members of each house of the Legislature.

Exempts Specified Rental Housing. The measure exempts a property from the surcharge if (1) it is used exclusively as rental housing and (2) the average value of a housing unit is less than $2 million (adjusted annually for inflation).

Deposits Surcharge Revenues in Newly Created State Fund. The measure deposits the revenues derived from the property tax surcharge in a new state fund, the Lifting Children and Families out of Poverty Fund. Revenues deposited in the fund would be allocated pursuant to a set of formulas for various purposes, as shown in more detail in Figure 1. Under these formulas, certain allocations would come off the top. For example, the measure requires that funds be allocated to reimburse the state General Fund for revenue reductions arising from increased property tax deductions claimed by PIT and corporation tax filers as a result of the measure. After these specified allocations are made, the remaining funds are allocated by percentage.

Fiscal Effect

New Surcharge Revenues. The surcharge would be collected from 2017-18 through 2036-37. In 2017-18, the surcharge likely would raise between $6 billion and $7 billion. Surcharge revenue amounts in future years would be expected to generally grow over time (in nominal terms).

Decreased State PIT and Corporate Tax Revenues. The increased property tax payments resulting from the measure would decrease taxable personal and corporate income as higher property tax payments are deducted and, in turn, decrease state PIT and corporation tax revenues. We estimate that this decrease in PIT and corporation tax revenues probably would be a few hundred million dollars annually. As discussed above, the measure requires a portion of the surcharge revenues be used to reimburse the state General Fund for these PIT and corporation tax losses.

Allocates Revenues to California Promise Zones

Background

Two Federal Programs Assist Areas With Concentrated Poverty. Since 2010, two federal programs—the Promise Neighborhood program and the Promise Zone program—have aimed to assist certain high-poverty areas in better coordinating public services. The ultimate goal of these programs has been to improve the outcomes of children and adults living within those areas. The U.S. Department of Education administered the Promise Neighborhood program between 2010 and 2012—awarding nationwide 46 planning grants of up to $500,000 each and 12 implementation grants of up to $6 million each. Areas in California received eight planning grants and four implementation grants. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is currently administering the Promise Zone program. Benefits of Promise Zone designation include assignment of federally funded staff and preference for many federal grant programs. Two geographical areas in California (located within Los Angeles and Sacramento) are currently Promise Zones. Promise Zone designation lasts for ten years. The HUD has designated 13 Promise Zones nationally since the program started in 2014. (The federal government has indicated that it will award all allowable 20 Promise Zone designations by the end of 2016.)

Proposal

Establishes California Promise Zone Program. The measure establishes a new state program that would designate certain areas as California Promise Zones. To be eligible for California Promise Zone designation, the measure specifies that a geographical area must have (1) a population of 200,000 or less, (2) academic attainment rates that are lower than the state average, and (3) poverty and unemployment rates that are higher than the state average. Similar to the goals of the federal Promise Neighborhood and Promise Zone programs, the purpose of the California Promise Zone program is to improve the outcomes of children living within those zones by providing comprehensive public services from birth into adulthood. California Promise Zones must include participation of, or sponsorship by, eight types of community organizations, including an early childhood development provider, a public school, and a business organization. Federally designated Promise Neighborhoods or Promise Zones that apply to the program would be automatically designated as California Promise Zones.

Provides Each Zone $500,000 and Priority for Other Grant Programs. The measure allows the California Department of Education (CDE) to designate up to 40 California Promise Zones between 2017 and 2036 using a competitive application process. California Promise Zone designation would last for ten years and CDE could renew the designation if a zone continues to meet program requirements. The measure provides each California Promise Zone with a one-time grant of $500,000 for the first year of its designation, with no subsequent funding authorized. The measure also gives the California Promise Zones priority for various federal and state grants if they meet certain standards.

Requires Promise Zones to Submit Plan for Improving Services and Annual Reports. Applicants for California Promise Zone designation must submit with their application a plan for improving the outcomes of children in their area, including a list all of organizations that will offer services and a description of their roles. The plan must include ways to measure Promise Zone outcomes using longitudinal data. The measure also requires each California Promise Zone to submit an annual report to CDE that includes information about how many people it served and its performance.

Designates CDE as Lead Agency. The measure designates CDE as the lead agency for administering the program and requires it to select the first round of California Promise Zones in spring of 2018. The measure also tasks CDE with several specific administrative responsibilities, including working collaboratively with other state agencies to implement the program and providing annually a list of California Promise Zones to the Legislature.

Fiscal Effects

Total State Grant Costs of Up to $20 Million, Funded From New Surcharge Revenues. The measure creates a California Promise Zone Account in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. The account would receive $500,000 from surcharge revenues for each California Promise Zone designated in the prior year. Funds in the account would be used to provide grants to California Promise Zones. If CDE were to designate the maximum number of California Promise Zones allowed by the measure, total grant costs would be $20 million, with the bulk of grant costs likely incurred in 2018-19 and 2019-20, as CDE approves initial applications. The exact annual grant costs would depend on the number of areas applying and the number of designations CDE awards each year.

Administrative Costs, Funded From New Surcharge Revenues. We estimate CDE’s associated administrative costs would be less than $1 million annually, with costs likely higher in the first year of administration. The administrative costs at other state agencies involved in coordinating the California Promise Zone measure with CDE would likely be minor and vary somewhat by agency depending upon each agency’s specific level of involvement. The measure provides that these administrative costs would be reimbursed out of the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. As discussed later, there is an overall cap on surcharge revenues deposited in the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account.

Allocates Revenues to California Prenatal and Early Childhood Services Program

Background

Home Visiting Programs Provide Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Services. Home visiting programs provide prenatal and early childhood services to eligible families through in-home visits. There are several different home visiting models that are targeted at improving child health and well-being, such as the Nurse-Family Partnership, the Tribal Home Visiting Program, and Healthy Families America. The structure, content, and frequency of the home visits depend on the home visiting model. For example, under the Nurse-Family Partnership model, registered nurses provide periodic home visits to first-time mothers during pregnancy and continuing until the child turns two years old.

Department of Public Health (DPH) Administers the California Home Visiting Program. The DPH administers the California Home Visiting Program that was created through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and is funded by the federal government. The program has served over 4,000 families since June 2012. Under this program, home visiting services are provided in 24 counties under either the Healthy Families America or Nurse-Family Partnership home visiting model. Under the Healthy Families America model, pregnant women or new mothers who are deemed high-risk based on program criteria are eligible for services. Pregnant women who are less than 28 weeks pregnant, are low-income, and are first-time mothers are eligible for services under the Nurse-Family Partnership model. DPH estimates that services provided through the Healthy Families America model cost $5,800 per family and services provided through the Nurse-Family Partnership model cost $10,000 per family.

Proposal

This measure would increase funding for home visiting services beyond what is currently provided by the California Home Visiting Program.

Home Visiting Program Would Be Administered by DPH and Implemented in All Counties by Home Visiting Organizations. Under this measure, DPH and counties would share responsibility for administering the home visiting program. At the state level, DPH would determine which home visiting models would be implemented, establish the qualifications for home visiting organizations, and determine the allocations of funding, among other responsibilities. Funding would be allocated annually to all counties based on the need in each county, which would be determined using a formula based on the number of children in poverty in a given county compared to the number of children in poverty statewide. Two or more counties would be able to form a county group and jointly participate in the home visiting program. Each county or county group would be responsible for administering grants to home visiting organizations that would conduct home visits for eligible families in the given county. The department would also oversee mobilization and outreach activities carried out by the home visiting organizations. These would include provider training for home visiting programs and referral services or outreach to eligible families with the goal of expanding the pool of organizations eligible to be home visiting organizations and increasing the utilization of the home visiting programs.

Eligible Families Would Have Children up to Age Five and Meet Medi-Cal Eligibility Criteria. Families would be eligible for home visiting services under this measure based on family composition and income. To meet the family composition eligibility criteria, families would either include a pregnant woman, parent, or primary caregiver of a child aged five or younger. The child, parent, or primary caregiver must also be enrolled in Medi-Cal—a joint federal-state program that provides health care services to qualified low-income persons—be eligible for Medi-Cal, or be otherwise eligible for Medi-Cal but for immigration status.

Fiscal Effects

This measure would allocate additional funding to home visiting programs. The programs would have the potential to impact state and local government spending as discussed below.

Measure Would Allocate Over $1 Billion to Home Visiting Programs Annually From New Surcharge Revenues. The measure would create a Home Visiting Account in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. The account would receive 15 percent of the monies deposited into the fund (after off-the-top allocations, discussed previously). We estimate that, in 2017-18, between $850 million and $1 billion would be allocated to the Home Visiting Account to provide for expanded home visiting services. The funding allocated annually for this purpose generally would grow over time, tracking the growth of the new surcharge revenues.

Administrative Costs, Funded From the New Surcharge Revenues. We estimate that DPH would incur annual costs of potentially up to several million dollars, depending on whether new home visiting models not currently being used were implemented. We estimate that counties would additionally incur costs potentially in the low tens of millions of dollars to administer the program at the local level. The measure provides that these costs would be reimbursed from the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund.

Allocates Revenues to Education for California Children Program

Background

Certain Low-Income Families Qualify for Subsidized Child Care and Early Education Services. The state’s subsidized programs are intended to enable low-income parents to work while also benefiting children’s early development. Currently, to be eligible for subsidies: (1) families must earn no more than 70 percent of the State Median Income (SMI), (2) a child must be under the age of 13, and (3) parents must be working (with the exception of the State Preschool Program). While the SMI that is used to determine eligibility has not been updated since 2007-08, it is still much higher than the federal poverty level (FPL). For example, for a family of three (either two parents and one child or one parent and two children), the current SMI cap is $42,216 whereas the 2015 FPL for a family of three is $20,090.

Some Families Guaranteed to Receive Services, Others Receive Priority Based on Income Level. In the current system, California funds subsidized child care and early education for all qualifying CalWORKs families. California also funds some qualifying non-CalWORKs families, with highest priority given to families with the lowest income. As funding is insufficient to cover all qualifying non-CalWORKs families, long waiting lists for subsidized child care are common.

In 2015-16, Budget Includes $2.8 Billion for Subsidized Child Care and Early Education. About two-thirds of this funding comes from the state and one-third from the federal government. Though some families pay fees for child care, fee revenue comprises less than 1 percent of total funding. In 2015-16, California is funding full-day child care and preschool for more than 250,000 children as well as part-day preschool for an additional almost 100,000 children.

State Supports Local Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS). The state supports local QRIS designed to improve the quality of infant and toddler child care and preschool. Local QRIS typically evaluate and monitor the quality of these services based on teacher qualifications, curriculum, and academic environment, among other metrics. Funds are allocated to providers, with priority given to rewarding providers with the highest quality rating. Typically, providers use state QRIS funding for staff development. In 2015-16, the state provided $74 million to support local QRIS. Of this amount, the state provided $50 million ongoing for improving preschool and $24 million in one-time funds for improving care for infants and toddlers.

State Provides Loans to Cover Certain Child Care Facility Costs. The state currently has a revolving fund that offers interest-free loans to local educational agencies and other agencies that contract with the state to provide child care and preschool services. Providers may use loans to renovate existing facilities or lease portable facilities. The average loan for renovation in 2013-14 was $54,000, while loans for portable facilities range from $70,000 to $210,000, depending on the type of portable facility leased. Child care providers must repay the loans within a ten-year period. Regarding renovation, providers may use loans to ensure their facilities comply with federal and state laws and regulations. Regarding leasing, providers may use loans to purchase portable facilities. At the end of the ten-year lease period, the state transfers ownership of the portable facility to the provider.

State Requires Child Care Staff to be Licensed and Supports Some Associated Education. The state requires some child care staff to have a Child Care Associate Credential or a Child Development Teacher Permit. These licenses require individuals to complete a certain amount of general education and early education coursework. People interested in obtaining one of these licenses typically enroll in relevant academic courses at the California Community Colleges (CCC). In the 2014-15 school year, about 18,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) students took such courses at CCC. Though less common, some people enroll in early education courses at four-year colleges and universities. At the California State University, for example, about 6,500 FTE students majored in early childhood education and development in 2014-15.

State Provides Some Financial Aid for Students in These Programs. College students who intend to teach or supervise in a child care center and enroll in an approved course of study are eligible to apply for a grant to cover a portion of their expenses. Administered by the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), this financial aid program provides an annual grant of $1,000 per participant enrolled at a two-year institution and $2,000 per participant enrolled at a four-year institution. Awards are made on a competitive basis, and participants (enrolled in two-year or four-year institutions) can renew their awards for one year. In 2015-16, the state will provide grants totaling $277,000 to 243 participants (208 at two-year institutions and 35 at four-year institutions). In addition, many of these students are eligible for other financial aid programs, such as the state Board of Governor’s fee waiver program (community colleges), the state Cal Grant program (all public institutions), and the federal Pell Grant program.

State Also Funds After School Education and Safety Program (ASES). The ASES program provides grants to providers of before and after school programs for students in kindergarten through ninth grade. Each program must provide (1) tutoring and/or homework assistance in core academic subjects and (2) enrichment activities such as physical activity, art, music, or other general recreation. All staff who directly supervise students in the program must meet the minimum qualifications for an instructional aide. Schools that have a high percentage of pupils eligible for free and reduced price lunch receive priority for these grant funds. Schools that receive funding for after school programs during the school year are eligible to receive an additional grant to operate the program during the summer and other school vacations. California provides $550 million annually for ASES (school-year and summer programs combined). In 2015-16, ASES is serving more than 400,000 students.

Proposal

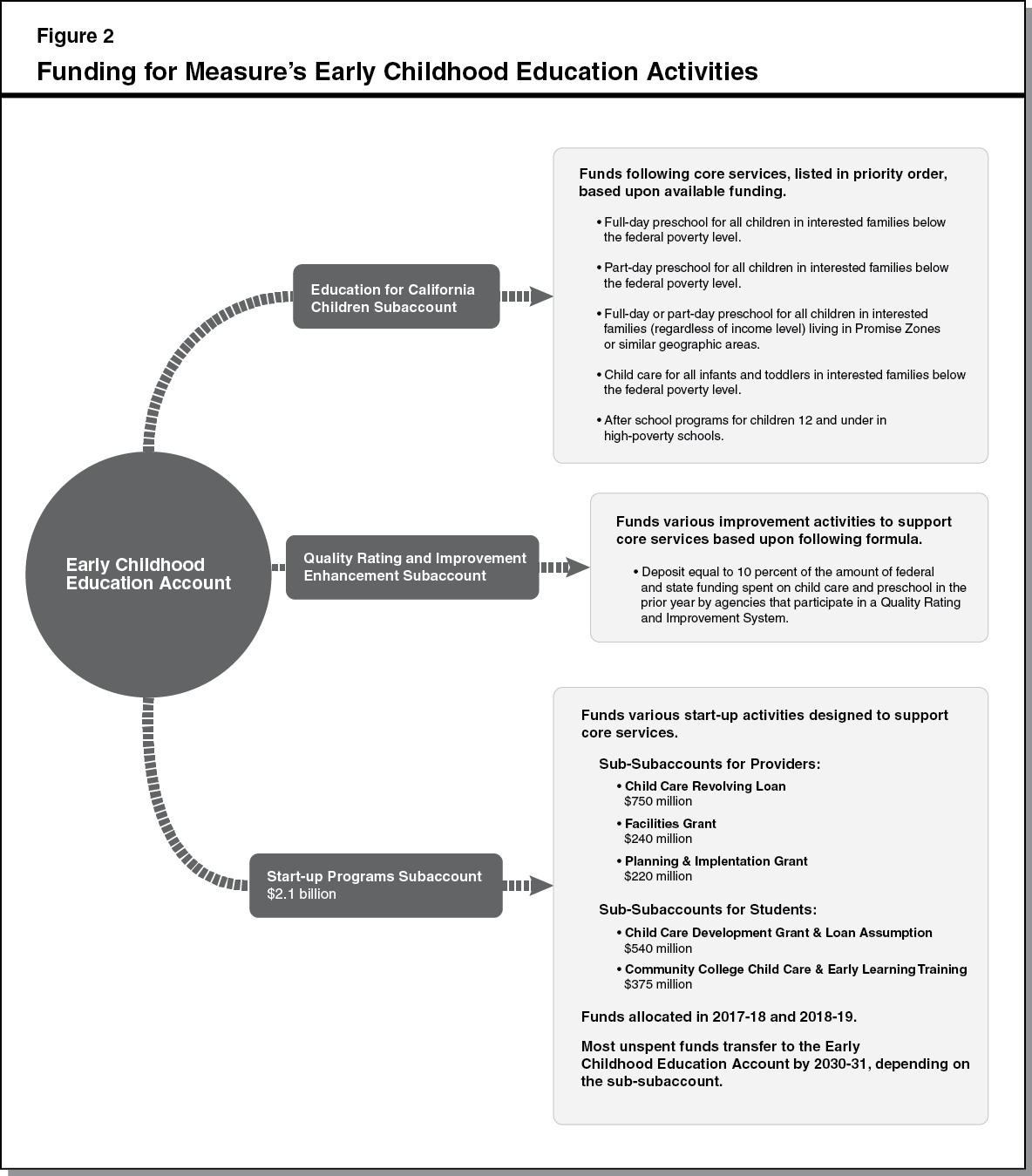

Measure Contains Several Child Care and Early Education Provisions. The measure creates an Early Childhood Education (ECE) Account within the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. The account would receive 57 percent of monies deposited into the fund (after off-the-top allocations). As shown in Figure 2, the measure creates various subaccounts and sub-subaccounts within this main account. Below, we describe the activities the measure authorizes, beginning with the child care, preschool, and after school program expansions funded from the Education for California Children Subaccount; then turning to quality improvement activities funded from the Quality Rating and Improvement Enhancement Subaccount; and ending with start-up activities.

Child Care, Preschool, and After School Program Expansion

Over the operative period of the measure, the bulk of available ECE Account funding would be for expanding child care, preschool, and after school programs. The measure sets forth five program expansion priorities funded from the Education for California Children Subaccount. The top priority would have first call on available funds in the subaccount, the second priority would have second call, and so on, until all available funds in the subaccount have been spent. The five priorities beginning with the top priority, are:

-

Full-day state preschool for all interested children from families with incomes below the FPL.

-

Part-day state preschool for all interested children from families with incomes below the FPL.

-

Full-day and part-day preschool for all interested children who live in California Promise Zones or other low-income areas as designated by the CDE.

-

Child care for all interested children birth to 36 months from families below the FPL.

-

A higher reimbursement rate for after school programs for children 12 and under at schools where (1) more than 75 percent of the students qualify for free lunch, (2) the staff members meet certain credentialing requirements or other qualifications as deemed necessary by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, and (3) the program provides a minimum local match of cash or in-kind support equal to one-third of the total additional grant. (Facilities and space usage may comprise no more than 25 percent of the total local match requirement.) The higher reimbursement rates apply to both the school-year and summer programs.

Quality Improvement

Funds in the Quality Rating and Improvement Enhancement Subaccount would be for increasing QRIS grants. The measure annually deposits into this subaccount an amount equal to 10 percent of the total state and federal funds that participating QRIS agencies spent in the prior year on providing subsidized child care and preschool. The measure effectively takes this amount off the top prior to funding the program expansions described above each year from 2017-18 through 2036-37. Participating QRIS agencies, in turn, would receive a share of subaccount funding equal to the share of children they serve from all children receiving care at QRIS participating agencies statewide. The measure allows QRIS agencies to spend their grants on (1) increasing reimbursement rates for participating providers who are able to achieve higher quality ratings and (2) supporting providers’ quality improvement efforts that will increase their QRIS ratings in the future.

Start-Up Programs

The measure designates a total of $2.1 billion for a variety of start-up purposes. The measure allocates a portion of these funds in 2017-18 and a portion in 2018-19. In general, the start-up activities would be for supporting the child care and preschool expansion described above. The measure creates three new programs involving providers and two new programs designed for students. In most cases, if carryover exists in these start-up sub-subaccounts, it eventually would return to the ECE Account for supporting other early education activities. We discuss the start-up programs below.

Creates a New Revolving Loan Program for Child Care Providers. The measure provides $750 million ($500 million in 2017-18 and $250 million in 2018-19) for a new loan program for child care and preschool centers based on the structure of the Charter School Revolving Loan program. (The charter school program offers loans of up to $250,000 to help new schools with start-up activities, including hiring staff, developing curriculum and programs, and covering initial lease and payroll costs.) Because the measure does not specify particular loan amounts or use of funds for the new program, CDE and State Board of Education (SBE) likely would have broad discretion in administering the program. Consistent with the charter school program, the measure specifies that the loans would be interest-free for a five-year term. Repaid loans would fund new loans for other centers. The measure would allow loans to be made from 2017-18 through 2036-37. The measure is silent on what would happen to funds after this time period.

Creates a Facilities Grant for New Child Care Providers. The measure provides $240 million in 2017-18 to fund a facilities grant program for new child care or preschool centers. The new program is to be based on the existing Charter School Facility Grant Program. (The charter school program provides certain schools up to $750 per student for facility lease costs.) The grants would be for five-year terms, though CDE and SBE have some discretion to change this time line, and would be given out from 2017-18 through 2021-22. The measure sets the maximum grant under the new program at $750 per child served at the center for the first three years of operation, $500 per child for the fourth year of operation, and $250 per child in the fifth year of operation.

Funds Planning and Implementation Grants for Providers. The measure provides a total of $220 million in 2017-18 for three-year grants to child care and preschool providers. The CDE would be required to commence grant awards prior to June 30, 2022. The measure bases the new grant program on an existing federal planning and implementation grant program for charter schools. (The federal program issues grants to charter schools for various costs, including equipment and supplies, curriculum development, and training for new teachers. It also issues grants to established charter schools to disseminate best practices and help other schools implement those practices.) The measure requires SBE to adopt regulations that presumably would include specificity on allowable uses of grant funds. Under the measure, grant amounts would vary depending on the age of the children served and the setting of care. Providers serving infants and toddlers in family child care homes or networks would receive grants of $4,500 each, whereas providers serving infants and toddlers in centers would receive $15,000 each, and preschool providers would receive $45,000 each.

Increases Financial Aid Available to Students Training to Be Child Care Providers. The measure provides $540 million ($65 million in 2017-18 and $475 million in 2018-19) for financial aid for college students training to become child care providers. As detailed below, students can receive financial aid in the form of either a grant or loan forgiveness. Students cannot receive both the grant and loan forgiveness. The measure designates CSAC as the administering agency for both aid programs.

-

Expands Grants Available to Students Training to Be Child Care Providers. The measure creates a new grant program based on the state’s existing grant program but with higher grant amounts. The measure authorizes the new program to issue a total of up to 175,000 additional grants from 2017-18 through 2023-24—up to 150,000 additional grants of up to $2,000 each for community college students, and 25,000 additional grants of up to $5,000 each for four-year college students. If a grant recipient does not work as a child care provider upon graduation, they would need to repay their grant to the state. All repaid funds would return to the ECE Account.

-

Creates New Student Loan Forgiveness Program for Certain Child Development Professionals. The measure creates a new loan forgiveness program to be modeled after the state’s existing loan forgiveness program for teachers. (Under the teacher loan-forgiveness program, students typically are selected while enrolled in college and receive awards to pay down their student loans after they begin teaching.) Depending on the type of permit or credential held by the child care worker, a recipient would be eligible for either $1,000 or $2,000 of loan forgiveness after the end of the first year of work and either $1,500 or $3,000 after the end of each of the second through fourth years of work. Students would be able to apply for this program from 2017-18 through 2023-24.

Increases Community College Early Education Course Offerings for Students. The measure provides a total of $375 million ($62.5 million in 2017-18 and $312.7 million in 2018-19 for use from 2018-19 through 2023-24) to the CCC Chancellor’s Office for the purpose of expanding child care and early learning course offerings. The measure is silent on exactly how the Chancellor’s Office could use the funds to expand course offerings. The measure sets associated enrollment targets of up to 8,000 additional FTE students in 2017-18, up to 15,000 FTE students in 2018-19, and up to 25,000 FTE students each year from 2019-20 through 2023-24. In each case, these targets would be measured from the 2016-17 enrollment level.

Monitoring and Reporting

The measure establishes various monitoring and reporting requirements for CDE, program providers, CSAC, and CCC. Specifically, the measure requires CDE to establish evidence-based indicators to evaluate the effectiveness and outcomes of the programs that the measures requires it to administer. The measure requires child care, preschool, and after school providers who receive ECE Account funding to submit data annually to CDE. The CDE is then required to issue an annual report on implementation and outcomes. The measure also requires CSAC and CCC to issue annual reports on the implementation of the new financial aid programs and on the early education course offering expansion, respectively. As with the other program reports required by the measure, these reports must include program outcome data.

Fiscal Effects

Substantial Additional State Spending on Child Care and Preschool. We estimate that the measure would provide between $3.2 billion and $3.8 billion for the ECE Account beginning in 2017-18 and annually thereafter, with annual deposits generally growing over time, tracking the growth in the new surcharge revenues. The ECE Account funding would be sufficient to cover many, but likely not all, of the priorities set forth by the measure. The measure also would create some higher local costs for ASES programs. Below, we highlight the major fiscal effects of the ECE Account provisions of the measure.

Measure Likely Fully Covers Cost of Top Two Preschool Expansion Priorities. We estimate available funding would fully support the top two program expansion priorities—full-day and part-day preschool services for all families below the FPL. We estimate fulfilling these top two priorities would cost several hundred million dollars annually. This cost is relatively low because a large majority of preschool-age children living below the FPL already enrolls in preschool or transitional kindergarten. The estimated cost of meeting these top two priorities would be lower if some of these families choose not to send their children to preschool.

Cost for Preschool Expansion in CDE-Designated Geographical Areas Could Vary Widely. The extent to which ECE Account funds would cover the remaining priorities set forth in the Education for California Children Subaccount would depend upon how CDE defines “other geographic areas” under priority three. We estimate the cost of providing preschool to all children (regardless of income) living in the California Promise Zones could range from the low hundreds of millions of dollars to about $1.5 billion annually, depending on the number of zones selected, the number of preschool-age children in those zones, the number of unserved children in those zones that choose to accept preschool, and the number of those that choose full-day over part-day preschool. If CDE defined other geographic areas narrowly, the additional costs of preschool expansion would be relatively low. Conversely, if CDE defined other geographic areas broadly, such that many areas of the state begin providing preschool for all children regardless of income, then the expansion costs would increase notably. In some cases, little, if any, of the ECE Account funds would remain for supporting the remaining fourth and fifth priorities of the Education for California Children Subaccount.

Other Education for California Children Cost Estimates. Regarding the fourth priority of the Education for California Children Subaccount, we estimate that providing subsidized child care to all infants and toddlers in families below the FPL would cost about $4 billion annually, though costs would be lower if some qualifying families decline the services. Given the estimated costs of the top four priorities, ECE Account funding likely would be insufficient to cover ASES expansion. We estimate that providing the higher ASES grant authorized under the measure to all schools currently participating in ASES would cost a couple hundred million dollars annually. If new schools participate in ASES and receive the higher grant amount, ASES costs could increase notably. If all schools with more than 75 percent of students receiving free lunch were to participate at the higher rate, we estimate ASES costs could increase by as much as $2.5 billion. This cost would be lower, however, to the extent ASES staff in these schools do not meet the measure’s staff or local matching requirements. In addition to the potentially higher state ASES spending, local ASES costs would increase due to the matching requirement.

QRIS and Start-Up Cost Estimates. Regarding QRIS, the state currently does not collect data on the total amount of state and federal spending on child care and preschool by local QRIS participating agencies. Based on some available data regarding existing QRIS agencies, we estimate that the QRIS subaccount might receive funding from the low tens of millions of dollars to hundreds of millions of dollars. To the extent that less funds are allocated to the QRIS subaccount, more funds would be available to fund preschool, child care, and after school activities. Given each local QRIS would receive a percentage of this amount based on its share of children served, the state would spend all available funds in the subaccount. Regarding start-up activities, the measure also is designed to spend whatever is available in that subaccount, but any unspent funds would roll forward for several years and then revert to the ECE Account.

Administrative Costs Likely to Range From Low Millions of Dollars to $10 Million Annually, Funded From New Surcharge Revenues. Under the measure, CDE, CSAC, and CCC would incur costs to administer the newly created programs. These costs would be more significant in the initial years of the measure, as these departments would need to establish policies and regulations for the new programs, develop application materials, review submitted applications, create funding procedures, and collect some additional data. Their costs would decline over time because start-up activities would be completed and ongoing monitoring and review activities likely would be less intensive. Of the three affected agencies, CDE would incur the highest administrative costs, with CSAC and CCC incurring lower costs. We estimate total annual administrative costs for all three of these agencies combined would range from the low millions of dollars to $10 million. The measure provides that these administrative costs would be reimbursed from funds from the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Subaccount in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund.

Allocates Revenues to Sector-Specific Job Training and Tax Credit Program

Background

California Has More Than 30 Workforce Development Programs. California’s current workforce education and training programs provide a range of workforce development services to between 3 million and 6 million people annually. In the 2015-16 fiscal year, the state spends about $5.5 billion from various funding sources on workforce development programs.

Some Existing Tax Credits Encourage Job Creation. Several provisions in California’s Revenue and Taxation Code provide incentives for qualified businesses to increase hiring. The New Employment Credit is available to businesses located in designated regions of the state that increase full-time hiring of qualified employees. The California Competes Credit is a competitive tax credit program available to businesses that increase their investment and hiring in California by negotiated levels. The California Film and Television Credit is a competitive tax credit available to qualified motion picture industry businesses based in part on hiring. The competitive tax credit programs are both administered by the California Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz), California’s single point of contact for economic development and job creation efforts.

Proposal

Creates a New Workforce Development Program. The measure creates a new job training program. Through this program, any qualified “regional collaborative”—a loosely defined group of organizations that may include educational institutions, local workforce investment boards, and various other nonprofit or public entities—may apply for a grant to provide job training activities and related educational services to individuals.

Each regional collaborative would be required to develop a program focused on one or more industrial sectors in a specified geographic region. The regional collaborative would be required to partner with local businesses in the designated industrial sector to (1) help develop job training curriculum and (2) provide job opportunities for individuals receiving training provided by the regional collaborative. In addition, the collaborative may partner with local nonprofit organizations that provide other related services to low-income individuals such as child care, transportation, housing, and legal services.

Training Program Supported by New Tax Credit. This measure also creates a new tax credit that would be offered to provide an incentive for businesses to participate in the new program. The amount of tax credits and conditions under which partnering businesses would qualify for them would depend on the details of a negotiated agreement between the businesses and the regional collaborative, subject to the approval of the GO-Biz. The measure specifies that credits would provide an incentive for both partnering with a regional collaborative and to hire program participants on a per-employee basis. The tax credits could be used by eligible taxpayers to reduce either their PIT or corporation tax liability. Credits would be non-refundable and could be carried forward for five years.

Fiscal Effects

Grants and Tax Credits Funded From New Surcharge Revenue. We estimate that this measure would make between $560 million and $660 million available in a new Job Training Account for the program, corresponding to 10 percent of monies deposited into the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund (after off-the-top allocations). Included in this amount are funds that would be transferred to the General Fund to replace revenue lost due to the use of job training tax credits. The proportion that would be used for grants to the regional collaboratives for job training programs and the proportion used to offset the new tax credits is uncertain. Ultimately, those amounts would depend on the specific details of the grant agreements and the level of participation and hiring by businesses.

Administrative Costs Funded From New Surcharge Revenues. The GO-Biz and the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) would incur one-time and ongoing costs to promulgate new regulations and to administer the new competitive grant and tax credit programs. We estimate that administrating the new jobs training and tax credit programs could cost up to several million dollars annually. Because the tax credits can be carried forward for five years, some fiscal effects would likely continue through 2045. This measure would provide for these administrative costs to be reimbursed from the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account of the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund.

CalWORKs Grant Increase

Background

The CalWORKs program provides monthly cash grants and employment services to low-income families with children. The amount of the monthly grant a family enrolled in CalWORKs receives is determined by current state law and varies with, among other things, the family’s size, the county in which the family lives, and how much other income the family has available. For example, as a family gains additional income through earnings, its monthly CalWORKs grant decreases until the amount of the grant reaches zero, at which point the family is no longer eligible for assistance. In this way, the CalWORKs grant levels set in state law indirectly determine the income level at which families no longer qualify for assistance, with higher grant levels resulting in higher income thresholds for exiting the program. The CalWORKs program is administered locally by county human services departments and overseen by the state Department of Social Services (DSS).

Proposal

Dedicated Revenue Source for Grant Increase. The measure creates a CalWORKs Account within the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. The CalWORKs Account would receive 8 percent of monies deposited into the fund (after off-the-top allocations). The measure provides that, beginning July 2018 and annually thereafter, the CalWORKs grant levels laid out in state law would be increased such that the total estimated costs of the higher grants would be equivalent to available monies in the CalWORKs Account. The amount of the grant increase could be adjusted at any time to prevent the costs of the increase from exceeding available funds.

Fiscal Effects

Direct and Indirect Costs of Grant Increases Covered by New Surcharge Revenues. We estimate that roughly between $450 million and $530 million in surcharge revenues would be deposited in the CalWORKs Account beginning in 2017-18 and annually thereafter, with annual deposits generally growing over time, tracking the growth in the new surcharge revenues. As discussed above, these funds would be used to increase CalWORKs grants, likely by more than 10 percent in 2018. By increasing CalWORKs grants, the measure would also raise the income threshold at which families become ineligible for assistance. This higher threshold would make it less likely that families would exit the program than would otherwise be the case, leading to a higher caseload. Counties would incur costs to provide case management and employment services for families that otherwise would have been discontinued, and these costs would be included in the total costs of providing the grant increase. As provided in the measure, the total cost of providing the grant increase would roughly equal, but not exceed, available monies in the CalWORKs Account.

State Level Administrative Costs Minor and Absorbable. The DSS would likely incur some costs to administer the CalWORKs grant increase provided by the measure that we estimate would be minor and absorbable. To the extent that costs are not absorbable, the measure would provide for reimbursement from the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account of the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund.

Allocates Revenues to State EITC Supplement

Background

In July 2015, the state enacted the California EITC, a PIT credit that is intended to encourage work and to reduce poverty among low-wage, working families by increasing their after-tax income. For those filers who qualify, the credit reduces income tax liability and, in the common case where the amount of the credit exceeds the filer’s liability, the difference is paid to the filer as a tax refund. By reducing PIT revenues that would have been received by the state absent the credit (an estimated $380 million in 2015-16), the California EITC reduces available resources in the state General Fund that could be used for other purposes. The California EITC is modeled after the federal EITC, a similar provision in the federal income tax code. The California EITC differs significantly from the federal EITC, however, most notably in that it (1) is more narrowly focused on filers with the very lowest incomes and (2) excludes earnings from self-employment when calculating a filer’s credit amount. The California EITC is administered by the FTB.

Proposal

Dedicated Revenue Source for State EITC Supplement. The measure creates an EITC Account in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. The account would receive 10 percent of monies deposited into the fund (after off-the-top allocations). Beginning in tax year 2017, the measure establishes a supplement to the California EITC. Under the supplement, filers could claim an additional credit amount equal to a percentage—likely between 5 percent and 10 percent—of the amount a filer is eligible to claim under the federal EITC. The measure provides that this percentage of the federal EITC that could be claimed under the supplement would be determined annually such that the total amount claimed by all filers (equivalent to revenue losses to the state) would approach, but not exceed, monies available in the EITC Account. Monies in the EITC Account would then be used to reimburse the state General Fund for the total amount of credit claimed. Annual determinations of the supplement’s matching percentage would be based on the estimated number of filers that would qualify for and claim the supplement, as well as the estimated amount of surcharge revenue that would be available in the EITC Account.

Fiscal Effects

State PIT Revenue Losses Reimbursed by New Surcharge Revenues. We estimate that roughly between $560 million and $660 million in surcharge revenues would be deposited in the EITC Account beginning in 2017-18 and annually thereafter, with annual deposits generally growing slowly over time, tracking the growth in the new surcharge revenues. As provided in the measure, these funds would be used to reimburse the state General Fund for the revenue loss associated with the supplement to the California EITC. In general, the measure requires that the supplement be structured to result in revenue losses that approach, but do not exceed, estimated available funds for a given year. However, uncertainty in estimating future claims and available amounts in the EITC Account may in some years result in there being insufficient funds in the account to fully reimburse the General Fund. Depending on how the measure is implemented, the General Fund may incur some costs for credits claimed but not reimbursed.

Administrative Costs Funded From New Surcharge Revenues. The FTB would incur costs to administer the EITC supplement that could be as high as $15 million annually. These costs would be driven primarily by (1) some filers filing PIT returns that otherwise would not have been filed and (2) a heightened level of review for all returns with refundable credits. Annual administrative costs for FTB to administer the supplement would depend on how the supplement is implemented and the emphasis FTB places on preventing fraudulent returns. The measure provides that these administrative costs would be reimbursed with funds from the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account in the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund.

Allocates Revenues to Administrative Cost Reimbursement

Measure Provides for Reimbursement of Administrative Costs. As noted previously, the measure provides that costs to administer new programs are to be reimbursed with monies from the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Fund. The measure creates the Administrative Cost Reimbursement Account and within it two subaccounts, with allocations to the account capped at 1 percent of annual revenues to the fund. The County Surcharge Administrative Cost Reimbursement Subaccount would compensate counties for ongoing costs to implement the measure, such as collecting the new surcharge. Allocations from the fund to this subaccount would be capped at 0.6 percent of annual revenues to the fund. For 2017-18, this is equivalent to roughly $40 million. The State Agency Administrative Cost Reimbursement Subaccount would compensate state agencies for ongoing administrative costs to implement the measure, excluding general overhead. Allocations from the fund to this subaccount would be capped at 0.4 percent of annual revenues to the fund. For 2017-18, this is roughly equivalent to $25 million.

Administrative Costs May Exceed Cap. Total state and local costs to administer the measure are uncertain and would depend to a significant extent on how the measure is implemented. However, it is possible that total administrative costs could exceed funds available for reimbursement under the measure’s specified cap. This could hinder full implementation of the measure and/or put pressure on existing state and local resources to fund administrative costs at a higher level than provided for by the measure. Alternatively, within its authority to amend the statutory provisions of the measure to make program implementation more effective, the Legislature could potentially amend the measure’s administrative cost reimbursement provisions to address this issue, should it come about.

Other Fiscal Effects

In addition to the direct fiscal effects discussed above, this measure could have several indirect effects on the state’s economy, state and local government finances, and state budgetary formulas. We describe these potential effects in greater detail below.

Net Impact on State Economy Is Unclear

The measure likely would have a variety of effects—both positive and negative—on the state’s economy. These effects, in turn, could alter state and local revenues and expenditures. Because the extent of these various effects is uncertain, the measure’s net effect on the economy and the related effect on state and local finances is unclear. On the one hand, the measure increases property taxes paid by many of California’s larger businesses. In response, some businesses may reduce the scale of their operations and employment in California, which would reduce economic activity in the state and government revenues. On the other hand, the measure funds several programs aimed at increasing labor force participation and reducing the number of Californians in poverty, both of which likely would improve the quality of the state’s workforce, making it more attractive to employers, and reduce costs for various government programs providing services and benefits to low-income individuals as fewer individuals and families qualify. These improvements should they occur, likely would take many years to fully realize.

Outreach Due to Measure May Increase Caseloads in Major Health and Human Services Programs

Certain activities that would result from the measure, particularly the significant expansion of home visiting programs across the state and the designation of California Promise Zones, emphasize providing referrals for, and maximizing enrollment in, major health and human services programs for which the state and local governments provide funding. Such programs include Medi-Cal, CalWORKs, and CalFresh. To the extent that the measure results in significantly increased enrollment, the state and counties could incur costs to provide benefits to additional enrollees. The timing and magnitude of this effect are uncertain.

Uncertain Effects on State Budgetary Formulas—Proposition 98

Proposition 98 Sets Minimum Funding Level for Schools and Community Colleges. State budgeting for schools and community colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by voters in 1988. The measure establishes a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges, commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. Both state General Fund and local property tax revenue apply toward meeting the minimum guarantee.

Measure Creates New School Funding Formula. The measure requires the Department of Finance (DOF) to estimate the amount of surcharge revenue transferred to backfill for the loss of General Fund revenue associated with higher tax deductions and credits. The department must make this calculation for the applicable fiscal year and prior fiscal year. The measure requires that schools receive a share of this revenue. Specifically, the measure requires schools to receive the share they would receive if the transferred revenue were considered General Fund revenue pursuant to Proposition 98 calculations. The amount derived by this calculation would be provided to schools in addition to their Proposition 98 allocation. If the DOF changes its applicable revenue estimate for a fiscal year, then the measure requires that the school allocation be adjusted as part of the annual budget act the following year.

Measure Becomes Inoperative if Higher Court Rules That Surcharge Revenue Counts Toward Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee. The measure includes a provision making the entire act inoperative if a California court of appeal or the California Supreme Court rules that the revenues collected under the measure are General Fund proceeds of taxes or allocated local proceeds of taxes for the purposes of making Proposition 98 calculations.

Effect of New School Funding Formula Depends Upon Several Factors and Could Vary. The effect of the new school funding formula on total school funding depends on one’s interpretation of the applicable provisions of the measure. Under one interpretation, the measure would have no effect on funding for schools and community colleges. Under another interpretation, the effect on school funding would vary depending on various underlying inputs. Under this latter interpretation, the impact of the new formula would depend primarily on changes in per capita personal income, General Fund revenue, and student attendance, as well as the size of the maintenance factor obligation in 2017-18 and the subsequent years of the measure. Changing assumptions about these inputs could change the effect of the new formula notably. Under some scenarios, the new formula would have no effect on total school funding whereas under other scenarios, the new formula would increase or decrease total school funding by hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

Uncertain Effects on State Budgetary Formulas—Proposition 2

Changes to State Reserve Deposits and Debt Payments. Proposition 2—approved by the voters in November 2014—places formulas into the State Constitution that determine the minimum amount of debt payments and budget reserve deposits to be made in a fiscal year. Proposition 2 calculations depend on several factors, including state General Fund revenue. As discussed above, the measure would reduce state General Fund revenue by increasing property tax deductions and tax credits claimed by PIT and corporation tax filers. The measure requires property tax surcharge revenues be used to backfill these General Fund losses. The backfill funds, however, may not count as General Fund revenue for certain Proposition 2 calculations. As a result, the measure could change required budget reserves and debt payments. The scope of these changes is unclear.

Summary of Fiscal Effects

This measure would have the following major fiscal effects on state and local governments:

-

Increased state revenues annually through 2036-37—estimated between $6 billion and $7 billion in 2017-18—from a new surcharge on high-value properties, with the revenues dedicated to various programs intended to reduce poverty.