Ballot Pages

A.G. File No. 2021-011

October 13, 2021

Pursuant to Elections Code Section 9005, we have reviewed the proposed constitutional and statutory initiative related to funding for students attending private schools (A.G. File No. 21-0011, Amendment #1).

Background

California Has Nearly 6.6 Million K-12 Students. California law requires all children between the ages of 6 and 18 to attend a public school, private school, or homeschool. These options are organized into kindergarten and grades 1 through 12 (K-12). The state currently has nearly 6.6 million K-12 students—6 million attending public schools, 471,000 attending private schools, and 84,000 attending homeschool. In this section, we review the structure and funding of each of these options.

Public Schools

Overview

State Required to Provide a Public School System. The California Constitution requires the state to organize and fund a system of public schools that provide free education for all students. The public school system consists primarily of school districts and charter schools, as well as a small number of schools operated by county offices of education and a few schools operated directly by the state.

School Districts Are the Largest Component of the Public School System. The state has 942 school districts operating 8,600 individual schools and enrolling approximately 5.3 million students. School districts are responsible for educating all students residing within their geographic jurisdiction, except for the students who have chosen to enroll in another public or private school option. Each school district is governed by a board elected by the voters who reside in that district.

Charter Schools Also Enroll a Significant Number of Students. The Charter Schools Act of 1992 authorized the creation of charter schools in California as an alternative to schools operated by districts. The state has 1,279 charter schools enrolling approximately 700,000 students. Charter schools are responsible for enrolling all interested students up to their maximum capacity. Charter schools operate under locally developed agreements (“charters”) that define their educational goals, services, and programs. Charter schools are monitored by the school districts in which they are located.

State Law Regulates School District Operations in Many Areas. For example, the law requires school district students to take standardized tests in several subjects, specifies the courses that students must complete to earn a high school diploma, and specifies the reasons a district may suspend or expel a student. State law also requires districts to provide various services to students with disabilities. (Districts sometimes arrange and pay for the education of these students at specialized types of private schools.) State law also sets requirements related to school employees. For example, the law requires districts to hire teachers with state teaching credentials, establishes a number of steps districts must follow before dismissing or laying off employees, and sets forth many rules for negotiating over pay and job responsibilities. Other areas regulated by state law include construction requirements for school facilities, rules for developing budgets, school start times, and the length of the school year and school day.

Charter Schools Have More Autonomy, but Subject to Some Requirements. In exchange for following the terms of their charters, the state exempts charter schools from many laws pertaining to school districts. For example, charter schools decide locally on their governance structure and have more flexibility in developing their budgets. On the other hand, charter schools remain subject to a number of state requirements. For example, charter school students take the same standardized tests as school district students.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Oversees the Public School System. The voters elect the State Superintendent on a statewide ballot every four years. The State Superintendent heads the California Department of Education and is responsible for administering programs, collecting and publishing data, monitoring compliance with state laws, and investigating certain types of complaints, among other duties.

Funding

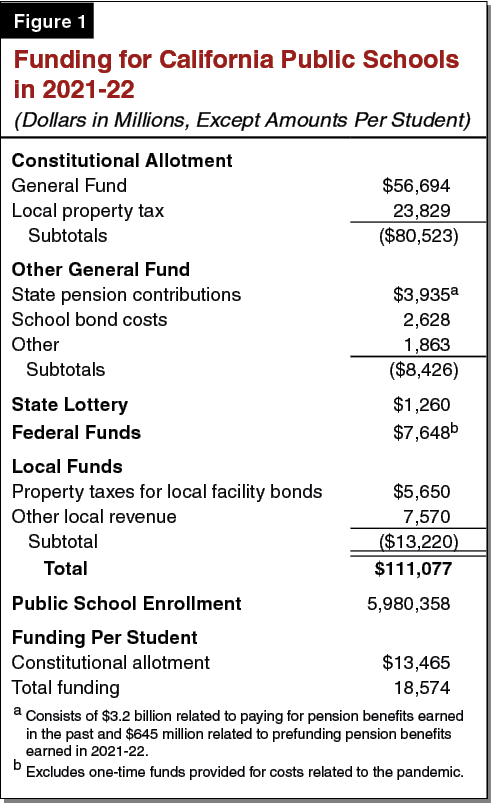

Public Schools Receive State, Federal, and Local Funding. As Figure 1 (on the next page) shows, revenues for public schools currently total about $111 billion ($18,500 per student). The largest source of funding is an allotment of state General Fund and local property revenue that the Constitution requires to be set aside for the public school system. This allotment accounts for more than 70 percent of the total funding for public schools (about $13,500 per student). Below, we provide more information on the main sources of funding for public schools. (These amounts exclude a significant amount of one-time funding provided by the federal government over the past two years.)

Constitutional Allotment. Proposition 98 (1988) sets aside a minimum amount of state General Fund and local property tax revenue for public schools and community colleges. The size of this allotment depends on several factors, including the number of students attending public schools, growth in the state economy, and General Fund revenues. In most years, the state must allocate about 40 percent of General Fund revenue to meet this requirement. (The General Fund—the state’s main operating account—is estimated to receive about $175 billion in revenues this year. The General Fund also pays for many other activities, including healthcare programs, state universities, and prisons.) The state allocates nearly all of the Proposition 98 allotment to public schools through a per-pupil formula. This formula provides a base amount for each student, plus additional funding for low-income students and English learners. Schools pay for most of their general operating expenses (including teacher salaries, supplies, and student services) using these funds.

State Pension Contributions. Public school teachers and administrators qualify for pensions when they retire. These pensions are funded by annual contributions from public schools, employees, and the state, as well as income from investing contributions in stocks and other assets. The state contribution consists of two components. The first component helps fund the cost of pension benefits employees are earning each year they work in the public school system. This amount is based on the number of teachers and administrators districts currently employ and the salaries of those employees. The second component is a contribution to make up for the fact that previous contributions were not large enough to cover the pension benefits that employees earned in the past. This amount depends on the number of teachers and administrators districts employed in the previous years, past contributions and investment returns, and other historical factors. Similar to the state, public schools also make pension contributions that include both of these components. (Most other public school employees also qualify for pensions when they retire, but the state does not fund these pensions directly.)

State School Bonds. The state provides grants to public schools to cover a portion of the cost of constructing and renovating facilities. The state raises the money for these grants by selling bonds to investors. (Before selling a bond, the state must obtain approval from a majority of voters statewide.) The state then repays the investors, with interest, from the General Fund. The state typically pays off bonds over several decades. The state currently is paying $2.6 billion annually related to five school bonds it sold between 1998 and 2016.

Federal Funding. Most of the funding provided by the federal government supports three main activities: (1) serving meals to low-income students (primarily through the National School Lunch Program), (2) providing academic support and other services at low-income schools, and (3) educating students with disabilities. The meals program reimburses schools based on the number of meals served. For the other two programs, public schools receive an allocation based on several factors, including the total school-age population (including private school students) within their geographic area and the percentage of students from low-income families. Public schools, however, must use a portion of their federal funding to provide services on behalf of private school students. This amount generally is proportional to the number of students in their attendance area who attend private schools.

Local Funding. The largest source of local funding for public schools consists of property taxes levied for school facilities. Similar to the state, districts can sell facility bonds with the approval of their local voters. Districts pay off these bonds over time with revenue generated by increasing their property tax rates. Other sources of local revenue include donations, parcel taxes, interest earnings, and developer fees.

Private Schools

Overview

Private Schools Educate Approximately 471,000 Students. The latest available data show that California has 3,050 private schools enrolling 471,000 students. Private schools are located throughout the state, and all but four small counties have at least one private school. Compared with school districts, private schools are somewhat more concentrated in urban areas and somewhat less common in rural areas. State data show that approximately 70 percent of private school students attend religiously affiliated schools and 30 percent attend secular (nonreligious) schools. Most private school students attend schools that are incorporated as nonprofit organizations, but some schools are unincorporated or organized as for-profit organizations. Like public schools, most private schools obtain accreditation. (Accreditation means that a school has developed and implemented an improvement plan with the assistance of an accrediting agency.)

Private Schools Operate With Minimal State Involvement. In contrast to the public school system, the state has relatively few laws governing private schools. With one exception, the state does not certify or monitor private schools. (The state does oversee private schools that have contracts to educate public school students with disabilities.) A private school generally can operate as long as it is able to attract students who are willing to pay tuition. The absence of state involvement means private schools have much more autonomy than school districts or charter schools. For example, private schools develop their own curriculum and goals for student learning, including graduation requirements and testing policies. They set their own admission policies, including the number of students they will admit and any entrance requirements. They also decide on the qualifications and duties of their teachers and administrators.

State Has a Few Requirements for Private Schools. Most notably, the law requires private schools to provide instruction in the same general areas as public schools; keep records of student attendance; and file affidavits identifying their address, contact information, and enrollment. State law also establishes rules related to health and safety. For example, private schools must (1) conduct background checks on employees who will interact with students, (2) ensure their buildings meet fire and earthquake safety requirements, and (3) require students to be immunized against certain diseases. (The law waives a few rules for small schools.)

Funding

Private Schools Generate Most of Their Revenue From Tuition. Available data suggest that private school tuition in California averages roughly $12,000 per year for elementary schools and $20,000 per year for high schools. Tuition varies widely, however, with many schools charging much less than the average and some charging more than twice the average. Available data also suggest that roughly one in four students attending a private school receives some type of tuition discount, generally based on financial need or having a sibling enrolled at the same school. In addition, many private schools charge enrollment or registration fees. Some schools also ask students to pay for books and supplies. Private schools typically supplement their tuition revenue by pursuing donations and other private funds.

Constitution Prohibits State Funding for Private Schools. The Constitution specifically prohibits the state from funding schools that are outside of the public school system. Another provision of the Constitution prohibits the state from funding religious organizations, including religiously affiliated schools. The state, however, does exempt nonprofit private schools from state income taxes and local property taxes.

Federal Support for Private Schools Is Limited. The most notable form of this support is the requirement for public schools to use some of their funding to pay for services on behalf of private school students. A few federal programs allow private schools to participate directly. For example, private schools can receive reimbursements for serving qualifying meals under the school lunch program. Available data suggest that private schools participate in these programs at relatively low rates.

Homeschool

Approximately 84,000 Students Attend Homeschool. Homeschooling is the practice of parents educating their children at home instead of sending them to regular schools. California law allows homeschooling in two basic ways. First, parents can register as a private school if they meet requirements that generally apply to private schools. Alternatively, parents with state credentials (or parents who hire tutors with state credentials) are exempt from nearly all requirements. Available data suggest that approximately 84,000 students attend homeschool. Similar to private schools, the state does not oversee or providing funding for these students.

Proposal

This measure proposes to establish a program that would provide state funding for students attending private schools. Below, we describe the main features of the measure, the associated changes to the Constitution, and the agencies that would administer the program.

Overview

Provides State Funding for Students Attending Participating Private Schools. The measure would allow a K-12 student to open an Education Savings Account administered by the state. After establishing an account, the student could enroll in a participating private school and submit a participation agreement to the state. For each year the student attended that school, the state would deposit $13,000 from the General Fund into the student’s account. Moving forward, the state would adjust the annual deposit amount based on changes in funding for the public school system. The student could use these funds to pay tuition, fees, and other educational expenses charged by the private school. The state would disburse the funds to pay these costs directly to participating schools in monthly installments. Students who decided to remain in public schools would not receive any funding under this program, but they would continue to generate funding for their public schools as they do under current law. Homeschool students also would not generate funding under the program.

Phases in Program Over Five Years, Based on Family Income. Assuming the voters approve the measure on the November 2022 ballot, the state would begin funding the program in 2023-24. The measure initially would limit the program to students from families with annual incomes below certain thresholds. For the first two years of the program, students would be eligible if the income of their parents (as reported on their joint tax returns) was less than $100,000. For the next two years, the threshold would increase to $200,000. Beginning in year five (2027-28), the program would be open to all students regardless of income. (For students from households filing single tax returns, the income threshold would be $50,000 for the initial two years and $100,000 for the subsequent two years.)

Sets Application Deadlines and Procedures. To receive the full deposit amount, a student would need to select a participating school and submit a participation agreement by April 1 prior to the start of the school year. For applications submitted after April 1, students would receive reduced deposits in their Education Savings Accounts. Each participation agreement would renew automatically until the student graduated or transferred to a different school.

Students Would Retain Unused Funds in Their Accounts. In some cases, a student would select a private school where tuition and other costs were less than the amount provided by the state. We estimate that as many as three out of four private elementary schools and one in three private high schools currently charge tuition of $13,000 or less. The measure provides that any unused funds would roll over to the following year and remain in the student’s account. In other cases, a student might select a private school where costs exceeded the amount provided by the state. The student would be responsible for these costs, but could draw upon any previously unused funds. (A student with financial need potentially could qualify for assistance from the private school.)

After Graduation, Students Could Retain Up to $60,000 for Postsecondary Education. Students would no longer generate funding once they graduated from high school or ceased to be K-12 students. Students, however, could retain up to $60,000 in their accounts to pay for tuition and related expenses at participating colleges, universities, and job training programs. (Moving forward, the state would adjust this limit for inflation.) The state would disburse funds from student accounts directly to these institutions. The measure would require the University of California, the California State University, and the California Community College system to accept these funds as payments for eligible costs. In addition, it would allow other public and private colleges and universities located in California and other states to register and accept these funds (job training programs located in California also could receive funds). Students would be able to draw upon their accounts until they reached age 30. The state would reclaim any funds exceeding the $60,000 limit or remaining in a student’s account after age 30. The state could allocate these funds for K-12 education, colleges and universities, and/or job training programs.

Imposes a Few Requirements on Participating Private Schools but Prohibits Additional Requirements. The measure requires participating private schools to register for the program and (1) obtain accreditation from an accrediting agency recognized by the state, (2) disclose the receipt and expenditure of funds provided by the state, and (3) periodically certify student attendance and eligible costs. The measure prohibits the state from making participation contingent on any other requirements. For example, the state could not require participating schools to modify their admission policies, change their curriculum, or require their students to participate in statewide tests. The measure would not change state’s ability to adopt laws that would apply to all private schools regardless of their participation in the program.

Constitutional Changes

Allows State to Cover Program Costs With Funds Set Aside for Public Schools. The measure amends the Constitution to authorize the program and exempt it from the sections prohibiting funding for private schools and religious organizations. In addition, it allows the state to pay for the program using Proposition 98 funds currently set aside for public schools. Finally, the measure modifies the calculation of the Proposition 98 funding requirement to include students participating in this program (in addition to students attending public schools).

Program Administration

Establishes New Board to Administer the Program. The board would consist of ten members representing a mix of elected officials, state agencies, private schools, and postsecondary institutions. The State Treasurer would be the chair of the board. The board would manage student accounts, including receiving state deposits and disbursing funds on behalf of students. It would invest any funds not immediately needed to pay eligible expenses and credit the earnings to student accounts. The board also would conduct oversight, including random audits to verify the use of funds for eligible expenditures. To accomplish these activities, the measure allows the board to adopt regulations, hire staff, and contract for services. The measure also allows the board to deduct an administrative fee of up to 1 percent of the annual funding provided by the state.

Assigns Oversight Duties to the State Superintendent. Although the board would administer most aspects of the program, the measure assigns a few new duties to the State Superintendent. These duties include (1) receiving applications from participating students, (2) verifying that participating students reside in California and are not also enrolled in public schools, (3) verifying the accreditation status of participating schools, (4) developing a list of accrediting agencies, and (5) investigating any allegations about ineligible students receiving funds.

Fiscal Effects

This measure would affect the state budget and the budgets of public schools. The magnitude of these effects largely depends on (1) the number of participating students, and (2) how public and private schools respond to the measure.

State Budgeting

Increased Costs Related to Students Currently Attending Private Schools. The 471,000 students who already attend private schools likely would be the first students to register for this program. In addition, some of the 84,000 students currently attending homeschool probably would switch to participating private schools. Since these students currently receive no state funding, their participation represents an additional cost to the state. A majority of current private school students and schools likely would participate in the program by year five, mainly because the annual funding amount is relatively large and the participation requirements are relatively modest. Participation probably would be less than 100 percent, however, because some students might be unaware of the program, miss the application deadline, or attend nonparticipating schools. Based on these factors, a range of participation rates is plausible. On the lower end, if 308,000 students participated (representing 60 percent of current private school students and 30 percent of homeschool students switching to private schools), the annual state cost at full implementation would be about $4 billion. On the high end, if 462,000 students participated (representing 90 percent of current private school students and 45 percent of homeschool students switching), the annual state cost would be about $6 billion. The state generally would pay for these costs through reductions to funding for public schools (as the measure allows) and/or reductions to other state programs supported by the state General Fund.

Cost Increases Would Be Smaller Prior to Full Implementation. The range of $4 billion to $6 billion represents state costs upon full implementation of the measure by year five (excluding any inflation-related adjustments). Initially, however, costs would be lower due to the program’s income thresholds. Available data suggest that the current private school students are divided about evenly into those with family incomes (1) below $100,000, (2) between $100,000 and $200,000), and (3) above $200,000. Assuming students in these groups participate in the program at similar rates, state costs would be approximately one-third of the full amount during the first two years of the program and two-thirds of the full amount during the subsequent two years.

Increased Costs Related to Students Moving From Public Schools, More Than Offset by Lower Spending on Public Schools. Over time, the costs of the program would increase based on the number of students shifting from public schools to private schools. The size of the shift would depend on many factors, including (1) the number of private schools that open or expand capacity in response to the measure, (2) the extent to which private schools raise tuition, and (3) the changes public schools make to their programs and services. The associated costs likely would be at least several billion dollars annually. For example, if 600,000 public school students (10 percent) were to shift to private schools, the additional state costs would be approximately $7.8 billion. (The shift reasonably could involve half as many to more than twice as many students.) Reduced state spending on public schools, however, would more than offset these additional costs. The state currently spends about $13,500 per student from funds constitutionally set aside for public schools, and this amount is estimated to exceed $14,000 per student—$1,000 more than the initial amount for the program—by 2023-24. The difference between these two amounts represents savings that likely would approach several hundred million dollars annually. For example, if 600,000 public school students shifted to participating private schools, total state spending on those students would decrease by around $600 million per year.

Reduced State Costs Related to School Bonds, Emerging Slowly. A shift in students from public schools to private schools would not affect the $2.6 billion in annual costs the state is paying for previous bonds. Moving forward, however, public schools likely would have lower demand for facility funding, which probably would result in the state selling fewer bonds. Over the next few decades, the associated reduction in state costs eventually could reach a couple hundred million dollars per year. The exact amount would depend on several factors, including the number of students shifting to private schools, the extent to which public schools could consolidate their facilities, the willingness of voters to approve future bonds, and interest rates on state debt.

Reduced State Pension Costs. To the extent public schools enroll fewer students, they likely would reduce their teaching and administrative staff. This reduction would reduce the state’s payment related to pension benefits earned by current employees (about $650 million per year). The reduction to state pension costs likely would be tens of millions of dollars annually, with the exact amount depending on several factors including the number of students leaving public schools and how quickly schools would reduce their staff. The amount the state contributes to pension benefits earned in the past, however, would not decrease.

Increased State Administrative Costs. The State Superintendent does not currently (1) administer an application process for students interested in attending private schools, (2) assess student eligibility for private schools, (3) determine whether private schools are accredited, or (4) maintain a list of accrediting agencies. We estimate that the costs of these additional duties would be a couple million dollars annually. The board overseeing the program also would incur costs, but we estimate the 1 percent administrative fee could cover these costs.

Public School Budgeting

Some Effects Would Depend on Implementation Decisions. The effects of this measure on public schools would depend upon how the state pays for the costs of students currently attending private school. For example, if the state covered the $4 billion to $6 billion cost entirely with existing Proposition 98 funds, it would need to reduce public school funding by a corresponding amount. This reduction would range from approximately 5 percent to 8 percent of Proposition 98 funding ($700 to $1,000 per student). The state, however, could provide public schools with more funding than the Proposition 98 minimum requires. In addition, adding private school students to the Proposition 98 calculation could increase the minimum requirement. (Any changes to the minimum requirement would depend on how the state adjusted the Proposition 98 calculations, underlying trends in public school attendance, General Fund revenues, and other factors.) Finally, the state could use the savings from students who shift from public to private schools to augment funding for students who remain in public schools. Under any of these scenarios, the reductions to public school funding would be smaller. Once the state determined the amount, public schools would need to reduce their operating budgets accordingly, probably through a range of actions including reductions to staffing and programs.

Reductions in State, Federal, and Local Funding to the Extent Students Move to Private Schools. Regardless of how the state covers the initial cost of the program, public schools would experience additional funding reductions to the extent students shift to private schools. The reduction in state funds would be approximately $14,000 for each student. In addition, public schools likely would experience reductions in federal and local funds. Some of these reductions would be direct. For example, schools serving meals to fewer students would receive smaller federal reimbursements. Some reductions would be indirect. For example, districts probably would not lose federal funding for low-income students, but they would need to use more of that funding for private school students. Other reductions would take time to emerge. For example, school districts probably would not sell as many local facility bonds, which would reduce the amount of property tax revenue they collect to pay for these bonds over the next few decades. A few revenue sources would not change. For example, some districts generate funding from certain taxes that do not vary based on enrollment. The magnitude of the reductions would depend on the number of public school students shifting to private schools and likely would vary significantly for individual school districts and charter schools across the state.

Cost Reductions Related to Enrolling Fewer Students. To the extent students shift to private schools, public schools also would experience lower costs. With fewer students, for example, public schools could employ fewer teachers and instructional aides. The immediate reduction, however, likely would not fully offset the reduction in funding because some costs do not depend directly on enrollment. For example, the costs of a school include salaries for the principal and office support staff, which do not decline in tandem with lower enrollment. To cover the difference, schools likely would need to make additional reductions or draw down reserves. Over a longer period, public schools likely could make additional changes that would offset their enrollment declines more fully. For example, they could close schools, consolidate classes and programs, or reorganize administrative responsibilities. Even with these actions, a few remaining costs would be unchanged. For example, some of the costs schools pay for pensions would not drop for another couple decades even with fewer students and teachers. Similar to the reductions in funding, reductions in costs also would vary across the state.

Summary of Major Fiscal Effects

We estimate this measure would have the following major fiscal effects:

- Increased annual state costs, likely growing to $4 billion to $6 billion by the end of the five-year implementation period, to provide state funding for students currently enrolled in private school. Depending on how the state implements the measure, these costs could be paid for with reductions to funding for public schools and/or reductions to other programs in the state budget.

- Increased annual state costs, probably at least several billion dollars, for students who move from public to private schools. Lower spending on public schools would more than offset these costs, likely producing state savings of several hundred million dollars annually.

- Likely reduced state costs for school bonds, potentially reaching a couple hundred million dollars annually within the next few decades.