October 19, 2015

The 2015-16 Budget:

California Spending Plan

Chapter 1: Key Features of the 2015–16 Budget Package

This publication summarizes California’s 2015–16 spending plan. It primarily reflects the Legislature’s passage of the budget and related trailer bills in mid–June 2015. While the text reflects additional actions taken later in the summer—for example, trailer bills ratifying new labor agreements—the figures generally reflect estimated budget totals as of June 2015.

Budget Overview

State Spending

Figure 1 displays total state and federal spending in the 2015–16 budget package. As shown in the figure, the spending plan assumes total state spending of $161 billion (not including bond funds), an increase of 1.3 percent over revised totals for 2014–15. The budget package also includes major increases in 2014–15 General Fund spending (primarily for education), which helps explain the large increase in expenditures between 2013–14 and 2014–15. General Fund spending grows little in 2015–16, increasing at only 0.8 percent. Programmatic spending growth, however, is masked by various one–time actions, including one–time spending in 2014–15 on debt payments and mandate backlog claims, and the end of the “triple flip” mechanism used to finance the state’s prior deficit financing bonds.

Figure 1

Total State and Federal Fund Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Fund Type |

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2014–15 |

||||

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

General Fund |

$100,005 |

$114,473 |

$115,370 |

$897 |

0.8% |

||

|

Special funds |

38,311 |

44,523 |

45,717 |

1,194 |

2.7 |

||

|

Budget Totals |

$138,317 |

$158,996 |

$161,087 |

$2,090 |

1.3% |

||

|

Selected bond funds |

$4,494 |

$6,089 |

$6,488 |

$398 |

6.5% |

||

|

Federal funds |

72,583 |

93,554 |

97,957 |

4,404 |

4.7 |

||

General Fund Revenues

Figure 2 displays the revenue assumptions incorporated into the June 2015 budget package. The budget assumes $115 billion in revenues and transfers in 2015–16, a 3.3 percent increase over 2014–15. The state’s “big three” General Fund taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), sales and use tax, and corporation tax—are assumed to increase at a slightly higher rate (4 percent). The PIT estimate for 2015–16 reflects a $380 million revenue loss associated with the new state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). General Fund revenue growth was much higher in 2014–15, increasing at a very healthy 7.7 percent rate.

Figure 2

General Fund Revenue Assumptions

(Dollars in Millions, Includes Education Protection Account)

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Change From 2014–15 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Personal income tax |

$67,025 |

$75,384 |

$77,700 |

$2,316 |

3.1% |

|

Sales and use tax |

22,263 |

23,684 |

25,240 |

1,555 |

6.6 |

|

Corporation tax |

9,093 |

9,809 |

10,342 |

533 |

5.4 |

|

Subtotals, “Big Three” Taxes |

($98,381) |

($108,877) |

($113,281) |

($4,404) |

(4.0%) |

|

Insurance tax |

$2,363 |

$2,486 |

$2,556 |

$70 |

2.8% |

|

Other revenues |

2,254 |

1,994 |

2,094 |

100 |

5.0 |

|

BSA deposit |

— |

–1,606 |

–1,854 |

–248 |

— |

|

Other transfers and loans |

376 |

–444 |

–1,045 |

–601 |

— |

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$103,375 |

$111,307 |

$115,033 |

$3,726 |

3.3% |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||||

Proposition 2

Figure 3 displays the calculations of Proposition 2 requirements incorporated into the budget package. As shown in Figure 3, Proposition 2 requires a $1.9 billion deposit into the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) and $1.9 billion of debt payments. Figure 4 displays the debt payments in the budget package that meet Proposition 2’s requirements.

Figure 3

Proposition 2 Calculations for 2015–16

(In Millions)

|

Proposition 2 Requirements |

|

|

Base amounta |

$1,753 |

|

Excess capital gains taxes captured by Proposition 2 |

1,955 |

|

Totals, Proposition 2 Requirement |

$3,708 |

|

Deposit into Budget Stabilization Account |

$1,854 |

|

Debt payments |

1,854 |

|

Calculation of Excess Capital Gains Taxes |

|

|

Total taxes from capital gains |

$11,659 |

|

Less amount equal to 8 percent of all General Fund taxes |

–9,330 |

|

Subtotals, Capital Gains Taxes Over 8 Percent Threshold |

($2,329) |

|

Less Proposition 98 share |

–$374 |

|

Totals, Excess Capital Gains Taxes Captured by Proposition 2 |

$1,955 |

|

a Equal to 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues. |

|

Figure 4

Proposition 2 Debt Payments in 2015–16

(In Millions)

|

Amount |

|

|

Special fund loan repayments |

$1,371 |

|

Special fund loan interest |

47 |

|

Proposition 42 loan repayment |

84 |

|

Proposition 98 settle upa |

256 |

|

UC pension program |

96 |

|

Total |

$1,854 |

|

aRelated to 2006–07 and 2009–10 minimum guarantees. |

|

The Condition of the General Fund

2015–16 Assumed to End With $4.6 Billion in Total Reserves. Figure 5 displays the condition of the General Fund under the revenue and spending assumptions of the 2015–16 spending plan, as estimated by the Department of Finance. As described above, the budget package requires a $1.9 billion deposit in the BSA, bringing the total BSA balance to $3.5 billion. Combined with the $1.1 billion balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU)—the state’s traditional budget reserve—the budget ends 2015–16 with $4.6 billion in estimated total reserves. If revenues differ from the budget assumptions—for example, if 2015–16 revenues end up higher than the assumed level shown in Figure 5—reserves could differ from this $4.6 billion total.

Figure 5

General Fund Condition

(In Millions, Includes Education Protection Account)

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

|

Prior–year fund balance |

$5,590 |

$2,423 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

111,307 |

115,033 |

|

Expenditures |

114,473 |

115,370 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$2,423 |

$2,086 |

|

Encumbrances |

971 |

971 |

|

SFEU balance |

1,453 |

1,116 |

|

Reserves |

||

|

SFEU balance |

$1,453 |

$1,116 |

|

Pre–Proposition 2 BSA balance |

1,606 |

1,606 |

|

Proposition 2 BSA balance |

— |

1,854 |

|

Total Reserves |

$3,059 |

$4,576 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. Source: Department of Finance. |

||

Major Features of the 2015–16 Spending Plan

The centerpiece of the 2015–16 spending plan is a large increase in Proposition 98 funding for schools and community colleges. Outside of K–14 education, the budget package makes notable augmentations for child care and preschool, higher education, and Health and Human Services (HHS) programs. The major features of the budget package are summarized below. We discuss these and other actions in more detail in Chapter 2.

Large Increase in Proposition 98 Funding. Due primarily to state General Fund revenues exceeding June 2014 budget assumptions, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantees for 2013–14 and 2014–15 are up by $612 million and $5.4 billion, respectively. The 2015–16 minimum guarantee is up $7.6 billion from the June 2014 estimate of the 2014–15 guarantee. The budget dedicates a portion of all this additional funding for ongoing purposes, with the largest ongoing augmentation for the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) ($6 billion). The budget package also dedicates a portion for one–time purposes, with the largest one–time augmentations for paying down the K–14 mandates backlog ($3.8 billion) and eliminating K–14 payment deferrals ($992 million).

Notable Increase in Funding for Child Care and Preschool Programs. The budget increases total funding for child care and preschool programs by $423 million (18 percent), with the bulk of the increase coming from state General Fund ($389 million). The additional funding supports rate and slot increases for non–California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) child care and preschool programs. It also supports caseload and cost of care increases for CalWORKs child care programs.

Also Notable Funding Increases for Universities. The budget includes increases of $241 million for the University of California (UC) and $254 million for the California State University (CSU), reflecting 8 percent year–over–year increases for each segment. The bulk of new funding is unallocated, with the universities allowed to use the funds for any operational or facility purpose. In exchange for the funding increases, the universities continue to agree to keep most resident undergraduate and graduate tuition charges flat. The budget also includes provisions relating to increasing resident enrollment at UC and CSU by 5,000 students and 10,400 students, respectively, in 2016–17 compared to 2014–15 levels. Part of UC’s increase is to accelerate payments on UC’s pension liabilities ($96 million). This funding (counted as Proposition 2 debt repayment) is contingent on UC limiting the amount of compensation that can be factored into pension benefits for future employees.

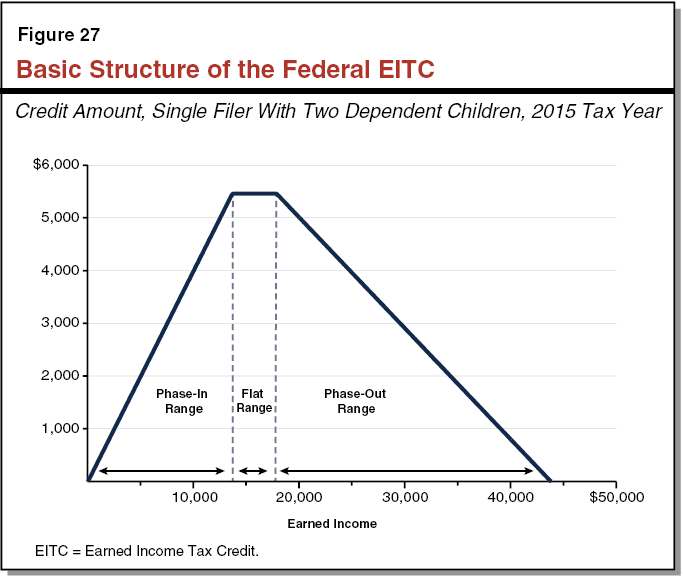

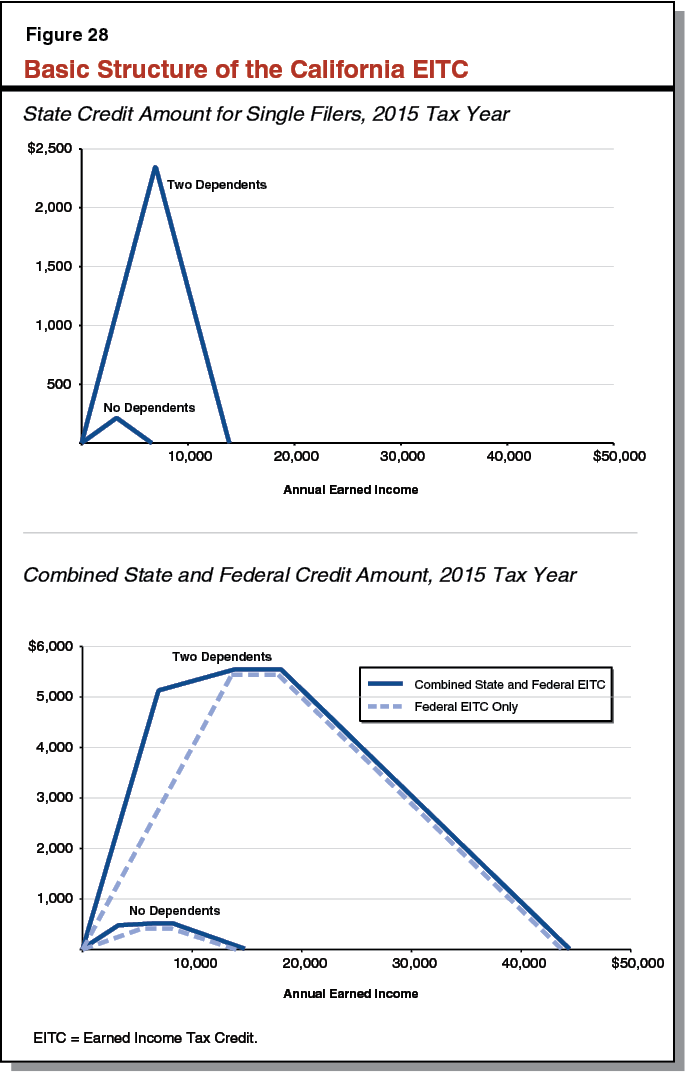

State EITC. The 2015–16 budget creates a new state EITC, which is estimated by the administration to reduce annual revenues by $380 million. The federal EITC is an income tax credit that increases the after–tax income of low–income workers. The state EITC will supplement the federal credit for lower–income individuals and households.

HHS Augmentations. In addition to spending augmentations due to increased caseloads, utilization of services, and labor costs in the HHS area, the spending plan reflects a select number of HHS policy–driven augmentations. Specifically, the budget package includes $226 million from the General Fund (one time) to restore the 7 percent reduction in In–Home Supportive Services service hours. Beginning May 2016, the spending plan provides Medi–Cal coverage to undocumented immigrants under the age of 19 who are otherwise eligible for those benefits but for their immigration status.

Evolution of the Budget

The Governor signed the 2015–16 Budget Act and 18 budget–related bills on June 24, 2015. Between that date and September 2015, the Governor signed five additional budget–related trailer bills into law. These bills are detailed in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Budget–Related Legislationa

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

AB 93 |

10 |

2015–16 Budget Act |

|

SB 97 |

11 |

Amendments to the 2015–16 Budget Act (“Budget Bill Junior”) |

|

AB 95 |

12 |

Transportation |

|

AB 104 |

13 |

Education and child care |

|

AB 114 |

14 |

Public works: building construction |

|

AB 116 |

15 |

Amendments to the 2014–15 Budget Act |

|

AB 117 |

16 |

Resources |

|

AB 119 |

17 |

Medi–Cal: nursing facilities |

|

SB 75 |

18 |

Health |

|

SB 78 |

19 |

Education finance: Local Control Funding Formula |

|

SB 79 |

20 |

Human services |

|

SB 80 |

21 |

Earned Income Tax Credit |

|

SB 81 |

22 |

Higher education |

|

SB 82 |

23 |

Developmental services |

|

SB 83 |

24 |

Resources |

|

SB 84 |

25 |

State government |

|

SB 85 |

26 |

Public safety |

|

SB 88 |

27 |

Water |

|

SB 98 |

28 |

Vacant positions and state health premiums |

|

September Budget–Related Legislation |

||

|

SB 99 |

322 |

State employees: memoranda of understanding |

|

SB 101 |

321 |

Amendments to the 2015–16 Budget Act |

|

SB 102 |

323 |

State government |

|

SB 103 |

324 |

Education |

|

SB 107 |

325 |

Redevelopment dissolution |

|

aIncludes budget bill and “trailer bills” identified in section 39.00 of the 2015–16 Budget Act that were enacted into law. |

||

January Budget Proposed $3.4 Billion Reserve. On January 9, 2015, the Governor presented his 2015–16 budget proposal to the Legislature. The budget proposal included $159 billion of state spending, consisting of $113 billion from the General Fund and $46 billion from special funds. The administration’s revenue estimates for 2014–15 increased more than $2 billion compared to its June 2014 estimates that were incorporated in the 2014–15 budget package. Those revenue estimates resulted in a multibillion–dollar influx of new funds for schools and community colleges under Proposition 98. The Governor’s Proposition 98 package included over $3 billion to pay down K–14 obligations and $4 billion for LCFF implementation. In addition, the administration estimated Proposition 2 requirements to be $2.4 billion—consisting of a $1.2 billion deposit in the BSA and a $1.2 billion debt payment requirement.

May Revision: Higher Revenues, Increased Proposition 98 and Proposition 2 Requirements. In the May Revision, the administration revised its revenue estimates upward $6.7 billion compared to the January budget proposal for 2013–14 through 2015–16 combined. The higher revenues were mostly offset by $5.5 billion in higher General Fund spending necessary to meet the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. In addition, the administration’s May 2015 calculations of Proposition 2 requirements increased from $2.4 billion to $3.7 billion—requiring a $1.9 billion deposit in the BSA and $1.9 billion of debt payments. Hundreds of millions of dollars in net General Fund savings in HHS programs, debt service, prisons, the Cal Grant program, and other programs provided the resources necessary to fund the Governor’s May Revision proposals. These proposals included (1) growing the SFEU reserve balance by almost $600 million, (2) establishing a state EITC ($380 million), and (3) providing over $100 million to the universities. (The May Revision also included the final estimate of the mandates “trigger” included in the 2014–15 budget package—$765 million.)

Initial Legislative Package Included More Spending and Budget Reserves. Our office’s May 2015 estimates of the state’s big three revenues were $3.2 billion higher than the administration’s May 2015 estimates for 2013–14 through 2015–16 combined. The Legislature adopted our office’s revenue estimates—including our estimates of local property taxes—in the first budget package passed on June 15, 2015. The package also reflected our office’s estimates of General Fund spending in a few areas where they differed from the administration’s estimates. This initial budget package included $2.1 billion in higher General Fund spending, including $760 million in higher Proposition 2 debt payments. Similarly, the Proposition 2 BSA deposit was also $760 million higher, contributing to a total reserve of $5.7 billion under the initial legislative budget plan. Key legislative priorities reflected in this initial budget plan were in the areas of HHS, child care and preschool, and higher education.

Final Budget Package Reflects Governor’s Revenue Assumptions. The Legislature passed the final budget package on June 19, 2015. The spending plan relies on the Governor’s lower May 2015 General Fund revenue assumptions and the resulting administration calculations of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and Proposition 2. While overall General Fund spending in the final budget package rose only $61 million above May Revision levels, various choices were made to shift spending priorities compared to the Governor’s proposal. Specifically, with savings resulting from (1) rejection of various administration proposals, (2) an error in the administration’s Medi–Cal estimates, (3) legislative changes made to the Middle–Class Scholarship Program, and (4) other legislative actions, the agreement made modest augmentations, generally in the areas of HHS, child care and preschool, and higher education.

Budget Package Signed by Governor. The Governor signed the 2015–16 Budget Act and related budget legislation on June 24, 2015. Similar to the 2014–15 budget, the Governor did not veto any General Fund appropriations, but vetoed $1.3 million in appropriations from other funds.

Late Session Budget Legislation. In September 2015, the Governor signed several trailer bills. We display these under “September Budget–Related Legislation” in Figure 6. These bills included legislative ratification of certain labor union bargaining agreements and the administration’s proposal related to the dissolution of redevelopment agencies.

Ongoing Special Sessions, Unallocated Cap–and–Trade Revenues. On the day the Governor signed the 2015–16 Budget Act, he called special sessions related to transportation funding and health care and developmental services financing. As of the date of this publication, these special sessions are ongoing. In addition, at the time of this publication, a significant amount of cap–and–trade auction revenue remains unallocated.

Chapter 2: Spending by Program Area

Proposition 98

State budgeting for school and community college districts is based primarily on Proposition 98, approved by voters in 1988. Below, we provide an overview of Proposition 98 funding and spending changes under the enacted budget package. We then highlight Proposition 98 spending changes specifically for K–12 education, adult education, and the California Community Colleges (CCC). In this section of the report, we also highlight notable non–Proposition 98 changes for the California Department of Education (CDE) and the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC). In the subsequent section, we describe preschool and child care changes.

Overview

Substantial Upward Revisions to Estimates of Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee. Proposition 98 establishes a minimum funding requirement commonly called the minimum guarantee. Figure 1 shows estimates of the minimum guarantee for 2013–14, 2014–15, and 2015–16. As shown in the figure, the estimate of the 2013–14 and 2014–15 minimum guarantees have increased $612 million and $5.4 billion, respectively, from the June 2014 estimates. These increases are due primarily to state revenue being higher than assumed in last year’s budget package. The estimate of the 2015–16 minimum guarantee is $7.6 billion (12 percent) higher than the 2014–15 Budget Act level. Under the budget package, Proposition 98 spending is set at these latest estimates of the minimum guarantees.

Figure 1

Tracking Changes in Estimates of Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee

(Dollars in Millions)

|

June 2014 |

June 2015 |

Increase |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

2013–14 |

$58,302 |

$58,914 |

$612 |

1.0% |

|

2014–15 |

60,859 |

66,303 |

5,444 |

8.9 |

|

2015–16 |

— |

68,409 |

7,550a |

12.4 |

|

aReflects increase from June 2014 estimate of 2014–15 minimum guarantee. |

||||

Increase in Estimated Property Tax Revenue Covers Increase in 2015–16 Guarantee. Figure 2 shows approved Proposition 98 funding levels for each of the three years by segment and fund source. As shown in the figure, growth from the revised 2014–15 level to the enacted 2015–16 level is $2.1 billion (3 percent). This relatively modest growth in the guarantee reflects growth in per capita personal income (3.8 percent) offset by a reduction due to spike protection (discussed below). In 2015–16, total Proposition 98 funding is $68.4 billion. Of this amount, $49.4 billion is General Fund and $19 billion is local property tax revenue. The estimated increase in local property tax revenue from 2014–15 to 2015–16 ($2.3 billion, 14 percent) is due in large part to the end of the triple flip and the shift of associated local property tax revenue back from cities, counties, and special districts to school and community college districts. Estimated growth in local property tax revenue ($2.3 billion) is slightly greater than growth in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee ($2.1 billion), resulting in a slight reduction in Proposition 98 General Fund from 2014–15 to 2015–16.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment and Source

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Change From 2014–15 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Preschool |

$507 |

$664 |

$885a |

$220a |

33% |

|

K–12 Education |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$38,162 |

$43,888 |

$43,151 |

–$737 |

–2% |

|

Local property tax |

13,736 |

14,432 |

16,380 |

1,947 |

13 |

|

Subtotals |

($51,898) |

($58,321) |

($59,530) |

($1,210) |

(2%) |

|

Adult Education Block Grant |

$25b |

— |

$500 |

$500 |

— |

|

California Community Colleges |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$4,223 |

$4,975 |

$4,801 |

–$175 |

–4% |

|

Local property tax |

2,182 |

2,263 |

2,613 |

350 |

15 |

|

Subtotals |

($6,406) |

($7,238) |

($7,414) |

($176) |

(2%) |

|

Other Agencies |

$78 |

$80 |

$80 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$58,914 |

$66,303 |

$68,409 |

$2,106 |

3% |

|

General Fund |

$42,996 |

$49,608 |

$49,416 |

–$192 |

–0.4% |

|

Local property tax |

15,918 |

16,695 |

18,993 |

2,298 |

14 |

|

aIncludes $145 million for existing wraparound care, formerly funded with non–Proposition 98 General Fund. Excluding this accounting shift, growth is $75 million (11 percent). bFor adult education consortium planning grants. Available for expenditure in 2013–14 and 2014–15. |

|||||

2015–16 Guarantee Affected by Spike Protection Provision. In a year when the minimum guarantee increases at a much faster rate than per capita personal income, a constitutional spike protection provision excludes a portion of Proposition 98 funding from the calculation of the minimum guarantee the subsequent year. The significant increase in the 2014–15 minimum guarantee triggered the spike protection provision, resulting in a corresponding $424 million reduction in the 2015–16 minimum guarantee (from what it would have been absent the spike protection provision). This is the second time spike protection has been triggered. (The first time was in 2013–14 based on a 2012–13 revenue surge.)

Outstanding Maintenance Factor Obligation Reduced Significantly. Due to the increase in state revenue, the estimated 2014–15 maintenance factor payment increased by $2.8 billion compared to the June 2014 estimate—rising from $2.6 billion to $5.4 billion—resulting in the largest maintenance factor payment made to date by the state. The state is expected to end 2014–15 with an outstanding maintenance factor of $743 million—the smallest outstanding maintenance factor obligation the state has owed since 2006–07. The maintenance factor obligation is projected to grow modestly in 2015–16, increasing to $772 million. The increase is linked to the change in per capita personal income. Because growth in state General Fund is less than growth in per capita personal income, no maintenance factor payment is required in 2015–16.

Budget Package Contains Many Spending Changes. Given the increases in the minimum guarantees across the three–year period, the budget package includes notable spending increases each year of the period. For 2013–14, the budget accounts for higher LCFF costs and uses the remaining funding increase for paying down the K–14 mandate backlog. The many spending changes for 2014–15 and 2015–16 are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. In addition to these changes, the budget package includes a $256 million settle–up payment related to meeting the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for 2006–07 and 2009–10 and $207 million in unspent prior–year Proposition 98 funds that have been repurposed. The remainder of this section of the report discusses these spending changes in more detail.

Figure 3

2014–15 Proposition 98 Changesa

(In Millions)

|

Technical Adjustments |

|

|

Make Local Control Funding Formula growth adjustments |

$306 |

|

Otherb |

149 |

|

Subtotal |

($455) |

|

K–12 Education |

|

|

Pay down mandate backlog |

$2,748 |

|

Eliminate deferrals |

897 |

|

Fund teacher training and support block grant |

490 |

|

Fund career technical education (CTE) grants |

150 |

|

Provide learning and behavioral supports for special educationc |

10 |

|

Fund Internet technology management, training, and technical assistance |

10 |

|

Finish developing evaluation rubricsd |

— |

|

Subtotal |

($4,306) |

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

Pay down mandate backlog |

$393 |

|

Eliminate deferrals |

94 |

|

Create basic skills transformation program |

60 |

|

Extend CTE Pathways Program |

48 |

|

Fund maintenance and instructional equipment |

48 |

|

Fund CCC Innovation Awards |

23 |

|

Create basic skills partnership pilot program |

10 |

|

Support implementation of baccalaureate degree pilot program |

6 |

|

Subtotal |

($683) |

|

Total, 2014–15 Changes |

$5,444 |

|

a All actions shown, except for technical adjustments, reflect one–time spending. bIncludes various property tax adjustments and adjustments to state agencies receiving Proposition 98 funding. cPart of special education package. d Provides $350,000 for the State Board of Education. |

|

Figure 4

2015–16 Proposition 98 Changes

(In Millions)

|

Technical Adjustments |

|

|

Back out prior–year fundsa |

–$6,554 |

|

Otherb |

335 |

|

Subtotal |

(–$6,219) |

|

K–12 Education |

|

|

Fund LCFF increase for school districts |

$5,994 |

|

Fund career technical education grants (one time) |

250 |

|

Increase preschool funding |

220c |

|

Fund various special education activities |

50 |

|

Fund Internet infrastructure grants (one time) |

50 |

|

Provide 1.02 percent COLA for select categorical programs |

40 |

|

Pay down mandate backlog (one time) |

31 |

|

Increase funding for the Charter School Facility Grant Program |

20 |

|

Increase funding for Foster Youth Services |

10 |

|

Other |

–3 |

|

Subtotal |

($6,663) |

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

Fund adult education consortia |

$500 |

|

Increase apportionment funding (above growth and COLA) |

267 |

|

Fund 3 percent enrollment growth |

157 |

|

Pay down mandate backlog (one time) |

117 |

|

Augment Student Success and Support Program (SSSP) for matriculation services |

100 |

|

Fund maintenance and instructional equipment (one time) |

100 |

|

Augment SSSP for implementation of local student equity plans |

85 |

|

Hire additional full–time faculty |

62 |

|

Provide 1.02 percent COLA for apportionments |

61 |

|

Fund CDCP noncredit courses at credit rate |

50 |

|

Provide funds to restore enrollment earned back by districts |

42 |

|

Supplement Cal Grant B awards for full–time CCC students |

39 |

|

Augment Extended Opportunity Programs and Services |

35 |

|

Fund new apprenticeships in high–demand occupations |

15 |

|

Increase funding for established apprenticeships |

14 |

|

Augment SSSP to fund dissemination of effective institutional practices |

12 |

|

Augment SSSP for technical assistance to improve district operations and outcomes |

3 |

|

Fund administration of higher Cal Grant B awards (one time) |

3 |

|

Provide 1.02 percent COLA for select categorical programs |

2 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,663) |

|

Total, 2015–16 Changes |

$2,106 |

|

aIncludes one–time funds for retiring deferrals, paying down the K–14 mandate backlog, and supporting various other one–time initiatives. bIncludes LCFF growth adjustments, growth for K–12 categorical programs, and annualized funding for 4,000 preschool slots initiated in 2014–15. cIncludes $145 million for existing wraparound care, formerly funded with non–Proposition 98 General Fund. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; COLA = cost–of–living adjustment; and CDCP = Career Development and College Preparation. |

|

Notably Reduces Backlog of K–14 Mandate Claims. The largest one–time spending increase in the budget package affects both school and community college districts. The budget package includes $3.8 billion to pay down the K–14 mandate backlog ($3.2 billion for the K–12 backlog and $632 million for the CCC backlog). Of the K–12 backlog funding, $40 million is earmarked for county offices of education (COEs), with intent language that they prioritize the funds for supporting new responsibilities associated with their review of districts’ Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs). After the state makes the $3.8 billion in payments, we estimate the outstanding K–14 mandate backlog will be $2 billion ($1.7 billion for schools and about $300 million for community colleges).

Eliminates K–14 Payment Deferrals. As required by trailer legislation enacted last year, the budget package also provides $992 million to eliminate all remaining K–14 payment deferrals. The budget year will be the first fiscal year since 2000–01 that the state is set to make all K–14 payments on time.

K–12 Education

$59.5 Billion Proposition 98 Funding for K–12 Education in 2015–16. This is $1.2 billion (2 percent) more than revised 2014–15 funding and $6 billion (11.2 percent) more than the 2014–15 Budget Act level. On a per–student basis, funding increases from the 2014–15 Budget Act level of $8,931 per student to the 2015–16 Budget Act level of $9,942 per student—an increase of $1,011 (11.3 percent). These amounts exclude Adult Education Block Grant funding and preschool funding. We discuss specific K–12 augmentations below.

Local Control Funding Formula

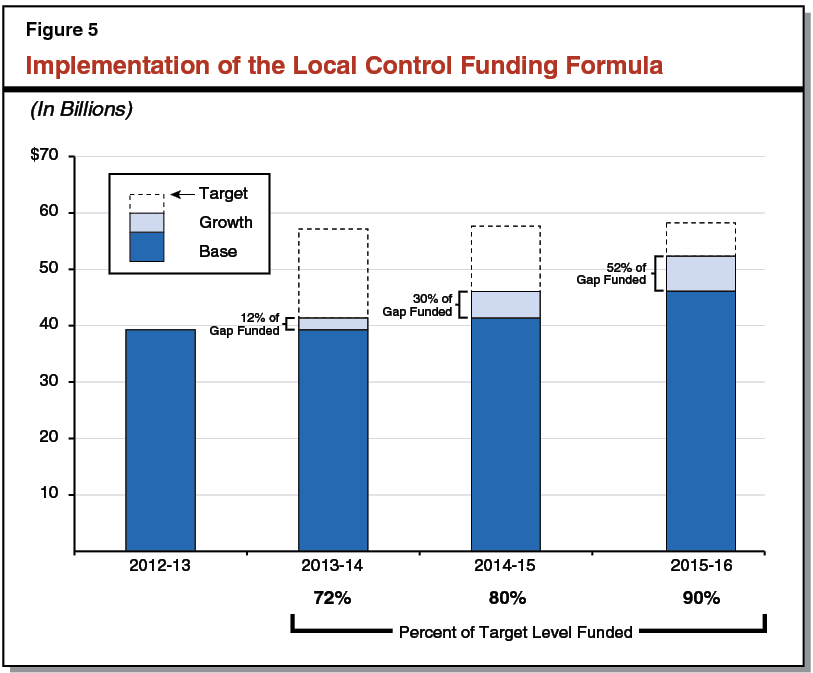

Large Increase for LCFF. The largest ongoing augmentation in the state budget is $6 billion for implementing the LCFF for school districts and charter schools—bringing total LCFF funding to $52 billion. This reflects a 13 percent year–over–year increase in LCFF funding. The administration estimates this funding will close 52 percent of the gap to LCFF target rates. As shown in Figure 5, the budget funds 90 percent of the estimated statewide full LCFF implementation cost. School districts and charter schools may use LCFF monies for any educational purpose, including implementation of their LCAPs.

Categorical Programs

New Secondary School Career Technical Education (CTE) Competitive Grant Program. The budget package includes $900 million in one–time funding for a three–year competitive grant program to promote high–quality CTE. Of this amount, $400 million is provided in 2015–16, $300 million in 2016–17, and $200 million in 2017–18. School districts, COEs, charter schools, and Regional Occupational Centers and Programs operated by joint powers agencies (JPAs) may apply for grants, individually or in consortia. The program provides separate pools of funding for large–, medium–, and small–sized applicants, based on applicants’ average daily attendance (ADA) in grades 7–12. Specifically, 88 percent of the funding is reserved for applicants with ADA greater than 550, 8 percent is reserved for applicants with ADA between 140 and 550, and 4 percent is reserved for applicants with less than 140 ADA. The Superintendent of Public Instruction (Superintendent), in collaboration with the executive director of the State Board of Education (SBE), will determine the number of grants to be awarded and specific grant amounts. Applicants that do not currently operate CTE programs; those that serve low–income students, English learners, foster youth, and students at high risk of dropping out; and those located in rural locations and areas with high unemployment will receive special consideration. In addition, the program prioritizes local applicants’ collaboration with postsecondary education, other local education agencies (LEAs), and established CTE efforts. Grantees are required to match grant funds and commit in writing to funding CTE programs after their grants expire.

One–Time Educator Effectiveness Block Grant. The budget includes $500 million (one time) for training and support of certificated staff, including teachers, administrators and counselors. The CDE is to allocate a total of $490 million to school districts, COEs, and charter schools based on the number of full–time equivalent certificated staff they employed in 2014–15. Funds may be used for a broad array of activities, including beginning teacher support, assistance for struggling veteran teachers, training for implementation of new state standards, and administrator training. The remaining $10 million is allocated to the K–12 High–Speed Network (HSN) to provide LEAs with training and technical assistance to help them better manage their Internet connections. The HSN may partner with COEs and other LEAs to provide statewide access to training and resources.

Pays Off Emergency Repair Program Obligation. Statute requires the state to provide a total of $800 million to school districts for emergency facility repairs. To date, the state has provided $527 million for the program. The budget includes $273 million (one time) for the final Emergency Repair Program payment. Of the $273 million, $145 million comes from a settle–up payment and $128 million comes from unspent prior–year Proposition 98 funds.

Package of Special Education Actions. The budget includes $67 million for a package of special education–related activities, as summarized in Figure 6. Of the $67 million, $52 million is ongoing and $15 million is one time. The largest ongoing augmentations in this package are for expanding services for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers with disabilities as well as requiring preschool staff training and parent education relating to identifying and meeting preschoolers’ special needs. The largest one–time augmentation is for one or two COEs to develop statewide resources and training opportunities for addressing students’ diverse instructional and behavioral needs.

Figure 6

Package of Special Education Actions

2015–16 (In Millions)

|

Program Area |

Action |

Amount |

|

Proposition 98 Funds |

||

|

Infant and toddler services |

Increase funding for districts to serve children with disabilities ages birth to three (brings total funding to $119 million). |

$30.0 |

|

Preschool slots |

Fund 2,500 additional part–day State Preschool slots, with priority given to students with disabilities. |

12.1 |

|

Learning and behavioral supports |

Provide funding for one or two county offices of education to develop statewide resources, provide trainings, and allocate subgrants to improve how districts meet students’ learning and behavioral needs. |

10.0a |

|

Preschool training, parent information, and rate increase |

Specify that State Preschool contractors must provide staff training and parent education on how to identify and meet students’ special needs. Increase part–day reimbursement rate by 1 percent to cover associated costs. |

6.0 |

|

State Special Schools |

Provide one–time increase for instructional activities at the state’s schools for deaf and blind students.b |

3.0c |

|

Fund swap |

Redirect federal funds from local assistance to state–level activities, then backfill with Proposition 98 funds. |

2.0 |

|

Subtotal |

($63.1) |

|

|

Federal Fundsd |

||

|

Office of Administrative Hearings |

Increase funding for state–level hearings regarding special education disputes (brings total funding to $12.8 million). |

$1.9a |

|

Alternative dispute resolution |

Increase funding for local grants to help districts and families resolve disputes without a trial (brings total funding to $1.95 million). |

1.7 |

|

State–level improvement activities |

Fund CDE to develop resources and provide technical assistance to districts implementing the new federally required statewide plan for improving services for students with disabilities. |

0.5 |

|

Subtotal |

($4.0) |

|

|

Total |

$67.1 |

|

|

aOne–time allocation scored to 2014–15 Proposition 98 guarantee. bThe budget also requires that these schools spend at least $4.8 million from their non–Proposition 98 funds in 2015–16 to address critical facility maintenance needs. cFunded with one–time Proposition 98 Reversion Account monies . dNew state–level activities funded in part by an increase in the state’s federal grant and in part by redirecting $2 million from local assistance. CDE = California Department of Education. |

||

Second Round of Broadband Internet Infrastructure Grants. The budget includes $50 million in one–time funding for HSN to provide certain schools with grants to purchase Internet infrastructure. Eligible schools are those that cannot administer online tests or can administer the tests only by shutting down other essential online activities such as e–mail. The Department of Finance (DOF) must approve projects with costs exceeding $1,000 per test–taking pupil and notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC). If any funds remain after meeting this core objective, HSN may provide grants to other school sites that do not have Internet infrastructure that allows them to increase their Internet speeds in a cost–effective manner. These latter allocations also are pursuant to a DOF–approved plan and JLBC notification.

Suspends HSN Budget Appropriation and Adds Annual Program Audit. The Imperial COE receives an annual grant from CDE to assist LEAs with network connectivity, Internet services, and information sharing. In recent years, HSN has kept a large reserve. To help spend down this reserve, the budget package suspends HSN’s annual budget appropriation of $8.3 million and instead requires the agency to use up to that amount of its reserve for 2015–16 operating costs. The budget also increases state oversight of the program by requiring HSN to submit to CDE, DOF, Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), and JLBC an annual financial audit that accounts for all funding and use of funds.

Expands Eligibility for Charter School Facility Grant Program. The budget provides a $20 million augmentation for this program, raising the total annual appropriation from $92 million to $112 million. The augmentation funds an increase in eligibility. Formerly, eligibility was limited to charter schools that (1) had at least 70 percent of their students qualifying for free or reduced–price meals or (2) were located in the attendance area of a surrounding elementary school that met this criterion. Trailer legislation reduces this threshold to 55 percent of students qualifying for free or reduced–price meals. In an effort to provide more certainty for charter schools regarding their eligibility for the program, trailer legislation also specifies that eligibility will be based on prior–year (rather than current–year) data.

Ongoing $10 Million Increase for Foster Youth Services. The 2015–16 budget increases funding for Foster Youth Services from $15 million to $25 million. The increase in funding is intended to reflect the new program requirements set forth in Chapter 781, Statutes of 2015 (AB 854, Weber). This legislation shifts the program’s focus from COEs providing foster youth services directly to school districts providing those services and COEs helping to coordinate services. Chapter 781 also expands the definition of foster youth to include children placed with relatives. This change makes the definition of foster youth the same as for LCFF.

Funding for Some Former Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA) Districts. The budget provides $4.6 million (one time) for school districts that previously received QEIA funding but are not eligible to receive LCFF concentration funding. The funding is equivalent to half of the amount districts received from QEIA in 2014–15. The QEIA program sunsets at the end of 2014–15.

Adds Two New Mandates to Block Grant. The budget adds a new mandate related to pertussis (whooping cough) immunizations to the schools mandates block grant and provides an associated $1.7 million augmentation to the block grant. This mandate requires schools on an ongoing basis to verify pertussis immunizations for all students entering the seventh grade and to undertake related record–keeping and reporting activities. Enacted through Chapter 434, Statutes of 2010 (AB 354, Arambula), the mandate took effect starting in the 2011–12 school year. The budget also adds to the block grant a new mandate relating to Race to the Top activities. The budget provides no associated increase in block grant funding for this mandate, as its estimated statewide cost is very small (less than $30,000).

Other Augmentations and Actions

CDE General Fund Augmentations. In addition to K–12 Proposition 98 funding, the budget includes $9.8 million in non–Proposition 98 General Fund augmentations and 3.5 new positions for CDE. Of this funding increase, $8.7 million is one time and $1.1 million is ongoing. The largest augmentations are $3.7 million (one time) for CDE to continue to contract with a legal firm to represent the state in the Cruz v. California case and $3.6 million (one time) to continue the Standardized Account Code System (SACS) upgrade project. Other notable augmentations include $350,000 for two three–year limited–term positions to administer the new CTE Incentive Grant Program and $335,000 for three existing CDE positions to support the new adult education consortia.

SACS Upgrade Project. The budget includes a total of $12.2 million ($5 million in federal carryover funds, $3.6 million one–time General Fund highlighted above, and $3.6 million General Fund carryover) to upgrade SACS. The California Department of Technology (CalTech) initially approved the project in 2011 with a cost of $5.9 million. In 2014, CDE revised the cost to $21.2 million, noting that it had significantly underestimated the project’s cost and complexity. Changes in data storage standards and software licensing and maintenance costs contributed to the cost increase. As of spring 2015, CDE had selected a vendor (M Corp) and planned to award a contract in the summer following final approval and legislative notification of the revised project scope and cost, as required by budget language. Subsequently, M Corp informed CalTech it would not extend the price quoted for the project, and, on August 12, 2015, CalTech terminated the project citing insufficient funding.

Various Other Policy Changes. The budget package also includes the following statutory changes.

- Expands Transitional Kindergarten (TK) Enrollment. Trailer legislation modifies TK rules to allow school districts and charter schools to enroll four–year–old children in TK if their fifth birthday falls between December 2 and the end of the school year. These children will begin generating attendance–based funding when they turn five. Formerly, only children turning five years of age between September 1 and December 2 could enroll in TK.

- Clarifies Requirements Related to Identifying Low–Income Students. Statute contains certain rules relating to how LEAs are to identify low–income students for the purposes of generating LCFF supplemental and concentration funding. The LEAs identify most low–income students based on annual paperwork that these students submit to participate in the National School Lunch Program. To identify some other low–income students, LEAs use what is known as the “alternative household income form.” Trailer legislation clarifies the information that LEAs must include on the alternative form and how the forms can be used and shared by LEAs.

- Adds LCFF Reporting Requirements at Full Implementation. Trailer legislation also adds intent language imposing new LEA reporting requirements once LCFF is fully implemented. At that time, LEAs will be required to report annually the amount of supplemental and concentration funding they received on behalf of low–income students, English learners, and foster youth as well as the amount they spent on behalf of these students.

- Adds Homeless Youth as a New Student Subgroup. Trailer legislation requires LEAs and schools with 15 or more homeless students to publish results of statewide assessments for homeless youth. In addition, it requires LEAs to include in their LCAPs specific goals for homeless youth in the eight state priority areas and specific actions the district will take to meet those goals.

- Extends Deadline for SBE to Adopt Evaluation Rubrics. Trailer legislation extends the deadline for SBE to adopt evaluation rubrics from October 2015 to October 2016. The evaluation rubrics are to measure and assess school district performance.

- Extends Reduction in Routine Maintenance Set–Aside. Trailer legislation modifies and extends provisions relating to the amount districts must annually deposit in their routine maintenance accounts. Prior to 2008–09, school districts were required to set aside 3 percent of their total expenditures for routine maintenance each year for 20 years after receiving state bond funding. From 2008–09 through 2014–15, statute reduced the routine maintenance requirement to a 1 percent deposit. For 2015–16 and 2016–17, trailer legislation requires districts to deposit no less than they deposited in 2014–15. For the next three years (2017–18 through 2019–20), the required deposit increases to 2 percent, rising to 3 percent beginning in 2020–21.

Commission on Teacher Credentialing

Budget Includes $33 Million for CTC. The budget provides $33 million for CTC—$26 million in special funds and $7 million non–Proposition 98 General Fund. This is $7 million (37 percent) more than the 2014–15 Budget Act level. The budget contains four major CTC–related changes, as discussed below.

Credential Fee Raised to Help Address Increased Teacher Disciplinary Workload. Trailer legislation increases the maximum credential fee from $70 to $100. The budget scores a corresponding increase of $4.5 million in credential fee revenue. The bulk of this funding increase ($3.9 million) is for addressing higher workload related to teacher disciplinary cases—specifically covering the costs of the Attorney General’s office, which represents CTC in discipline hearings when teachers appeal an adverse ruling from the commission. (Over the past several years, CTC has had an increase in the number of disciplinary cases appealed by teachers, resulting in a large backlog of unresolved cases that CTC expects will take several years to eliminate.) The remaining $600,000 in new credential fee revenue is split evenly between CTC’s certification and professional services divisions, supporting higher ongoing costs in those areas.

Streamlined Accreditation Data System. The budget package includes non–Proposition 98 General Fund of $3.5 million in 2015–16 and $1.5 million in 2016–17 for CTC to build a data system that it could use as part of a streamlined system to accredit teacher preparation programs in the state. Specifically, CTC plans to focus its accreditation reviews on issues identified by the data, as well as provide additional public information on program quality through a data dashboard accessible from CTC’s website. The commission plans to implement some data collection and reporting in 2016–17, with full implementation of the new data system scheduled for 2017–18.

Updates to the Teacher and Administrator Performance Assessments. For the past several years, the state has required that individuals seeking to become teachers pass a performance assessment. Currently, CTC has approved four allowable teacher performance assessments, and teacher preparation programs have discretion to select which of the four assessments they will administer to their teacher candidates. In 2013, the commission approved a similar requirement that candidates in administrator preparation programs pass a performance assessment in order to receive an administrator credential. The budget package provides non–Proposition 98 General Fund of $4 million in 2015–16 and $1 million in 2016–17 for various activities related to these assessments. Of the $5 million provided across the two years, $2 million is for updating the state–developed teacher performance assessment known as CalTPA to reflect the new state academic content standards, $1 million is for conducting a study to determine equivalent scores across the four teacher performance assessments approved by CTC, and the remaining $2 million is for developing the administrator performance assessment.

Updates to Subject–Matter Exams in Science. The budget also includes $600,000 from the Test Development and Administration Account to revise CTC’s teacher preparation science standards and update science content on required teacher exams to reflect the new state science standards.

Adult Education

$500 Million for Adult Education Block Grant. This funding implements a restructuring of adult education services begun in 2013. The restructuring is intended to improve coordination among providers and better serve the needs of adult learners. During the past two years, school districts and community college districts formed 70 consortia (largely coinciding with community college district service areas). With input from other regional groups (such as local workforce investment boards and libraries), the consortia developed joint plans to coordinate and deliver adult education in their regions. Each plan included (1) a needs assessment, (2) plans for coordinating and integrating existing adult education programs, and (3) strategies for improving student success. The block grant funding provides resources to begin implementing these plans.

Eligible Programs and Recipients

Instruction Authorized in Seven Areas. Consortia may use block grant funds for programs in seven adult education instructional areas: (1) elementary and secondary basic skills, (2) citizenship and English as a second language, (3) workforce programs for older adults, (4) programs to help older adults assist children in school, (5) programs for adults with disabilities, (6) CTE, and (7) preapprenticeship programs. (Providers may offer instruction in other adult education areas, such as parenting, home economics, and recreation, using other fund sources, including LCFF.)

LEAs Eligible for Block Grant Funding. Formal consortia membership is limited to school districts, community college districts, COEs, and JPAs. Each formal member may be represented only by an official designated by its governing board, and only members may receive block grant funding directly. A consortium member, however, may pass through block grant funding to other adult education providers, such as libraries and community–based organizations, serving students in the region.

Funding

Guarantees Funding for Existing Adult Schools. In 2013–14 and 2014–15, school districts and COEs operated under a maintenance–of–effort (MOE) provision that required them to spend the same amount annually on adult education as in 2012–13. During this period, school districts and COEs funded adult education using LCFF monies. The MOE provision expired July 2015. The 2015–16 budget effectively extends the MOE for one additional year but begins funding adult education from the block grant rather than LCFF. Specifically, the 2015–16 budget requires the CCC Chancellor’s Office to allocate up to $375 million of the $500 million block grant for existing school district and COE adult education programs. (If CDE determines the aggregate MOE level exceeds $375 million, then school districts’ and COEs’ allotments will be prorated downward accordingly.) To receive a part of the $375 million earmark, school districts and COEs must be formal members of adult education consortia.

Remaining Funds Distributed to Consortia Based on “Need for Adult Education.” The CCC Chancellor and Superintendent will distribute the remaining 2015–16 funds to the regional consortia based on each region’s need for adult education, as determined by measures relating to general adult population and immigrant population as well as low employment, educational attainment, and adult literacy. Beginning in 2016–17, the Chancellor and Superintendent will distribute the full block grant amount based on (1) the amount allocated to each consortium in the prior year, (2) the region’s need for adult education, and (3) the consortium’s effectiveness in meeting those needs. Trailer legislation tasks the Chancellor and Superintendent with identifying associated measures of consortia effectiveness by January 1, 2016.

Within Each Consortium, Locks in Funding for All Members Going Forward. Trailer legislation requires each consortium to align its Adult Education Block Grant allocation with its regional service plan. The trailer legislation, however, also specifies that members of a consortium generally are to receive at least as much as in the prior year. That is, if a consortium’s total block grant funding in a given year is equal to or greater than its prior–year amount, then each of its consortium members is to receive at least the same level of block grant funding as in the prior year unless the member no longer wishes to provide the service, is unable to do so, or has been consistently ineffective in meeting expectations despite interventions.

Requires State to Coordinate Federal Adult Education Funding. Trailer legislation requires the state to coordinate funding of two federal adult education programs with state Adult Education Block Grant funding. The two federal programs are: (1) the Adult Education and Family Literacy Act, also known as Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Title II, and (2) the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act (Perkins). Statute requires the Chancellor and Superintendent to develop a plan to distribute funds from these two federal programs to regional adult education consortia. The two agencies are required to submit the plan to DOF, SBE, and the Legislature by January 31, 2016.

Also Requires Local Coordination of Adult Education Funding. Trailer legislation also requires school districts, COEs, JPAs, and community college districts that receive funding from various state and federal adult education programs to become members of their regional consortia to better coordinate their programs. These other funding sources are community college apportionments allocated for the seven authorized adult education instructional areas, Perkins funding, WIOA Title II funding, state adult education funds for CalWORKs participants, Adults in Correctional Facilities program funding, and LCFF monies used for adult education.

Other Features

Includes Planning and Reporting Requirements. Statute requires consortia to approve three–year adult education plans. Trailer legislation requires these plans to contain several additional components, including a list of all other entities that provide adult education in the region and a description of actions the consortia will take to integrate services. Consortia are required to provide data annually to the Chancellor and Superintendent about their services and outcomes. Based on these data, the Chancellor and Superintendent must report annually to DOF, SBE, and the Legislature on the status of consortia, including their funding allocations, types and levels of service, and effectiveness in meeting their region’s adult education needs.

Requires Transparent Decision–Making. Trailer legislation requires each consortium to develop rules and procedures, to be approved by the Chancellor and Superintendent, regarding participation, decision–making, and reporting. The language specifies that all consortium decisions (such as approval of a regional plan or funding allocations) must be considered in an open meeting where members of the public have an opportunity to comment. The language also requires consortia to request and respond to feedback from other entities providing workforce education and training in the region.

Provides One–Time Funds to Develop Consistent Data Policies and Collect Data. The budget provides $25 million Proposition 98 General Fund ($12.5 million to CCC and $12.5 million to CDE) for data collection and reporting. The CCC and CDE must provide 85 percent of the $25 million to consortia to develop or update data systems and collect specified data. The remaining 15 percent is for state–level activities to develop consistent data policies, measures, definitions, and collection procedures. In addition, CCC and CDE are to develop shared data agreements among state agencies, including the Employment Development Department and the California Workforce Investment Board. Statute specifies that performance measures must include improved literacy; attainment of high school diplomas or their equivalent; number of certifications, postsecondary degrees, or completion of training programs; job placement; and improved wages.

Community Colleges

$7.4 Billion Proposition 98 Funding for CCC in 2015–16. This is $176 million (2.4 percent) more than revised 2014–15 funding and $812 million (12 percent) more than the 2014–15 Budget Act level. On a per–full–time equivalent (FTE) student basis, funding increases from the 2014–15 Budget Act level of $5,753 per student to the 2015–16 Budget Act level of $6,379 per student—an increase of $626 (10.9 percent). These amounts do not include the $500 million the budget provides for the Adult Education Block Grant. The budget also appropriates bond monies for the construction phase of seven previously approved CCC capital outlay projects. We discuss specific CCC augmentations below.

Apportionments

Significant Ongoing Increase in Apportionment Funding. The budget augments apportionments for enrollment growth, cost of living, unrestricted educational and operational purposes, noncredit instruction, and full–time faculty. All combined, ongoing apportionment funding increases 12 percent from 2014–15 to 2015–16. We discuss major apportionment increases below.

Funds 3 Percent Enrollment Growth to Be Distributed Under New Formula. The 2015–16 budget includes $157 million for 3 percent enrollment growth, supporting about 30,000 additional FTE students. The CCC Chancellor’s Office will distribute these funds using a new allocation model it developed pursuant to 2014–15 budget legislation. Under the new model, CCC will determine a district’s “need for access” using three factors: (1) its share of the state’s adult population without a college degree, (2) its share of unemployed adults, and (3) its share of households with income below the federal poverty guideline. The Chancellor’s Office will compare this measure of need with the district’s current share of community college enrollment, then allocate funds to reduce gaps between the two. In an effort to balance need, demand, capacity, and equity, the model also considers current enrollment and recent enrollment growth patterns and gives each district the opportunity to grow at a minimum of 1 percent.

Provides 1.02 Percent Cost–of–Living Adjustment (COLA). The budget provides $61 million to fund the statutory 1.02 percent COLA for apportionments. The budget also includes $2 million to provide a 1.02 percent COLA for four categorical programs: (1) CalWORKs Student Services, (2) Disabled Students Programs and Services, (3) Extended Opportunity Programs and Services (EOPS), and (4) Child Care Tax Bailout (which supports campus child care centers that serve as teaching labs for early childhood education students).

Provides Additional Unrestricted Funds Beyond Growth and COLA. The 2015–16 budget also provides a $267 million apportionment increase that districts may use for any educational or operational purpose, including retirement costs, professional development, and facility maintenance. In addition, the budget provides $50 million to increase the rate for certain noncredit courses (Career Development and College Preparation courses) to the credit rate, consistent with 2014–15 trailer legislation.

Funds Additional Full–Time Faculty. The budget includes $62 million for districts to hire additional full–time faculty. The CCC Chancellor’s Office is to distribute the funds to districts based on their share of FTE students. Provisional budget language sets forth rather complicated rules for adjusting each district’s “faculty obligation number” (FON), which, in turn, affects how many new full–time faculty members each district must hire. Districts with a relatively low existing FON will see the greatest increase in their FON, and, to the extent they do not already meet their new FON, will have to spend more of their funding allocations to hire additional full–time faculty. Districts already in excess of their new FON will not be required to hire new full–time faculty. Budget language specifies that districts must use any funds not needed to meet their FON for enhancing student success through the support of faculty, including (but not limited to) support of part–time faculty office hours.

Categorical Programs

Increases Student Success and Support Program. The budget augments the program by $200 million. Since 2012–13, total funding for the program has increased significantly—growing from $49 million in 2012–13 to $472 million in 2015–16. The augmentation for 2015–16 includes four components.

- $100 Million for Matriculation Services. These funds are to enhance orientation, counseling and advising, educational planning, assessment, and other student services, primarily for new students. This increase brings total funding for matriculation services to $285 million.

- $85 Million for Implementation of Student Equity Plans. These funds are to further improve access and outcomes for disadvantaged groups through implementation of student equity plans. This increase brings total associated funding to $155 million. Of this amount, up to $15 million may be used to fund agreements with up to ten districts to provide enhanced student support services for foster youth, consistent with the intent of Chapter 771, Statutes of 2014 (SB 1023, Liu). Provisional budget language clarifies that student equity plan funding may be used for existing campus–based and categorical programs that advance student equity.

- $12 Million for Workshops and Training. These funds are to help community college personnel improve student achievement, college operations, and leadership of statewide initiatives. The CCC also may use these funds to develop and disseminate effective practices through the creation of an online information clearinghouse. Provisional budget language specifies that effective practices shall include development of courses and educational programs for California Conservation Corps members, adult inmates of prisons and jails, and former inmates.

- $3 Million for Local Technical Assistance. These funds are to expand technical assistance to community college districts that demonstrate low performance in any area of operations. The augmentation brings total associated funding to $5.5 million.

Expands EOPS. The budget provides $35 million to restore EOPS to its pre–recession funding level. This program provides academic and support counseling, financial aid, and other support services to help disadvantaged students meet their educational goals. Total funding for the program in 2015–16 is $123 million.

New Financial Aid Program Supplements Cal Grant B Awards for Some Students. The budget provides $39 million to supplement the Cal Grant B access award for CCC students who are enrolled in 12 or more units. In 2015–16, the Cal Grant B access award, which provides aid for books, supplies, and living expenses, is $1,656 without the CCC supplement. The size of the CCC supplement will depend on the number of eligible CCC students enrolled in 12 or more units. The Chancellor’s Office estimates the new funding will provide additional support of about $800 per eligible student. The budget provides campuses a total of $3 million (one time) for administration of the new program.

Augments Existing Apprenticeships and Funds New Apprenticeships in High–Demand Occupations. The budget increases funding for existing apprenticeship programs by $14 million, bringing total annual funding to $37 million. Provisional budget language raises the hourly reimbursement rate for instruction from $5.04 to $5.46 to match the CCC noncredit rate. The budget also provides $15 million to support the development of new apprenticeships in high–demand occupations. The Chancellor’s Office indicates that new apprenticeships likely will be started in healthcare, advanced manufacturing, information technology, and green jobs (for example, jobs involving renewable energy) over the next two years.

Other Augmentations and Actions

Creates Basic Skills and Student Outcomes Transformation Program. The budget provides $60 million for a one–time incentive grant program to improve community college remediation practices. Districts may apply for grants to help them adopt or expand the use of evidence–based models for basic skills assessment, placement, instruction, and student support. Eligible activities under the grant program include curriculum redesign, professional development, release time for faculty and staff, and data collection and reporting. The number of awards and grant amounts will depend on the number of successful applicants. Statutory language specifies data collection requirements for participating community colleges and directs our office to evaluate the program’s effectiveness in interim and final reports to be issued by December 1, 2019 and December 1, 2021, respectively.

Creates Basic Skills Partnership Pilot Program. Complementing the larger basic skills grant program is a one–time $10 million grant program to promote more and better collaboration in delivery of basic skills instruction among high schools, community colleges, and CSU campuses. The CCC Chancellor’s Office will award five grants of $2 million each. To qualify for awards, community college districts must collaborate with local school districts and CSU campuses to better articulate English and math instruction across segments. Participating CSU campuses must commit to directing their underprepared students—either currently enrolled or planning to enroll—to basic skills instruction at community colleges. Statute requires the Chancellor’s Office to report by April 1, 2017 on program effectiveness, cost avoidance, and recommendations regarding the expanded use of community colleges to deliver basic skills instruction to CSU students.

Funds Start–up Costs for Baccalaureate Pilot Programs. The budget also includes $6 million for start–up costs related to the implementation of Chapter 747, Statutes of 2014 (SB 850, Block), which authorizes CCC to establish up to 15 baccalaureate degree pilot programs. The pilot districts can use these funds for equipment, library materials, curriculum development, and faculty and staff professional development, among other costs. Professional development activities could include bringing in speakers from community colleges that already have made the transition to offering baccalaureate programs, collaborating with university and industry colleagues, and participating in academic conferences.

Extends CTE Pathways Initiative. The budget provides $48 million to extend for one additional year an existing CTE initiative. The goal of the initiative is to help regions develop sustainable policies and infrastructure to improve CTE pathways among schools, community colleges, and regional business and labor organizations. The CCC and CDE award three–year grants under the program. With the additional funding, the segments will allocate new awards (or renew existing ones) for 2015–16 through 2017–18. To qualify for funding, grantees must work toward eight specific objectives set forth in the program’s authorizing legislation, Chapter 433, Statutes of 2012, (SB 1070, Steinberg). These objectives include aligning secondary and postsecondary CTE programs to create seamless transitions for students, providing professional development to facilitate CTE partnerships, and increasing the number of students who engage in work experience programs.

Enhances Education for Adult Inmates. Provisional budget language directs the Chancellor to identify one or more districts that are willing to use at least $5 million of their combined state funding on a one–time basis to develop effective educational programs for adult inmates and former inmates. Districts could use any unrestricted funding for this purpose. The language responds to the availability of private foundation funds to improve inmate education requiring a match of $1 in state funds for every $3 in private funds. The Chancellor will allocate any private funds received to participating districts in proportion to their use of state funds for this purpose.

Provides Physical Plant and Instructional Equipment Funding. The budget includes $148 million (one time) for facilities and equipment. The Chancellor’s Office is to allocate the funds to community college districts based on their FTE enrollment. Consistent with longstanding policy, districts may use the funds for scheduled maintenance, special repairs, hazardous substances abatement, architectural barrier removal, and seismic retrofit projects up to $400,000, as well as replacement of instructional equipment and library materials. Provisional budget language further expands allowable uses to include certain water conservation projects, including replacement of water–intensive landscaping, drip or low–flow irrigation systems, building improvements to reduce water usage, and installation of meters for wells to monitor water usage.

Increases Chancellor’s Office Staffing. In addition to CCC Proposition 98 funding, the budget includes a $340,000 non–Proposition 98 General Fund augmentation to begin supporting six new permanent positions in the Chancellor’s Office. The 2015–16 budget assumes the Chancellor’s Office will need some time to make all the new hires and correspondingly includes only a half year of funding, with the intent to annualize costs the subsequent year. The additional staffing is to help the system implement several statewide initiatives to improve student success and promote effective administrative and educational practices at community colleges.

Capital Outlay

Funds Construction Phase for Seven Previously Approved Projects. The budget provides $100 million from previously authorized general obligation bonds to support the construction phase of these projects. The state funded earlier phases of the projects in 2014–15. The projects include (1) $33 million to replace fire suppression, electrical distribution, communication, storm water, sanitary sewer, wastewater, and natural gas systems at the College of the Redwoods, Eureka campus; (2) $20 million to make seismic and building code corrections to the L Tower at Rio Hondo College; (3) $19 million to make seismic and code corrections to a campus center building at Santa Barbara City College; (4) $13 million to replace an instructional building at El Camino College’s Compton Center; (5) $8.4 million to construct a new academic facility at Los Rios District’s Davis Center; (6) $4 million to replace a fire alarm system at Mt. San Jacinto College; and (7) $1.7 million to renovate Hayden Hall at Citrus College.

Child Care and Preschool

Budget Act Provides $2.8 Billion for Child Care and Preschool Programs. As shown in Figure 7, the 2015–16 budget includes $1.6 billion for non–CalWORKs programs, $1.1 billion for CalWORKs programs, and $150 million for support programs. Combined, the 2015–16 Budget Act augments these programs by $423 million (18 percent) from the 2014–15 Budget Act level. The bulk of the increase is covered by higher Proposition 98 and non–Proposition 98 General Fund support.

Figure 7

Child Care and Preschool Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Change From 2014–15 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Expenditures |

|||||

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

Stage 1 |

$337 |

$330a |

$411 |

$81 |

24% |

|

Stage 2b |

367 |

355 |

414 |

60 |

17 |

|

Stage 3 |

202 |

220 |

278 |

58 |

27 |

|

Subtotals |

($906) |

($904) |

($1,103) |

($199) |

(22%) |

|

Non–CalWORKs Programs |

|||||

|

State Preschool |

$507 |

$614 |

$835 |

$220 |

36% |

|

General Child Care |

464 |

544 |

450 |

–94 |

–17 |

|

Alternative Payment |

177 |

182 |

251 |

68 |

37 |

|

Migrant |

27 |

28 |

29 |

2 |

6 |

|

Handicapped |

1 |

2 |

2 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($1,177) |

($1,370) |

($1,567) |

($197) |

(14%) |

|

Support and Quality Programs |

$74 |

$123 |

$150 |

$27 |

22% |

|

Totals |

$2,157 |

$2,397 |

$2,820 |

$423 |

18% |

|

Funding |

|||||

|

Non–Proposition 98 General Fund |

$764 |

$809 |

$977 |

$169 |

14% |

|

Proposition 98 General Fund |

507 |

664 |

885 |

220 |

33 |

|

Federal CCDF |

556 |

570 |

573 |

3 |

— |

|

Federal TANF |

330 |

353 |

385 |

31 |

9 |

|

aReflects Department of Social Services’ revised Stage 1 estimates for cost of care and caseload. bDoes not include $9.2 million provided to community colleges for Stage 2 child care. CCDF = Child Care and Development Fund and TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. |

|||||

Higher Spending Predominantly Due to Reimbursement Rate and Slot Increases. New program enhancements and expansions account for the vast majority of the year–over–year increase. As shown in Figure 8, the largest augmentations are for reimbursement rates and additional slots, which receive an additional $177 million and $138 million, respectively. We discuss these augmentations and caseload adjustments in greater detail below.

Figure 8

2015–16 Child Care and Preschool Changes

(In Millions)

|

Change |

Proposition 98 |

Other |

Total |

|

Reimbursement Rates |

|||

|

Increases the Standard Reimbursement Rate 5 percent starting July 1, 2015 |

$38 |

$23 |

$61 |

|

Increases Regional Market Rate 4.5 percent starting October 1, 2015 |

— |

44 |

44 |

|

Annualizes Regional Market Rate increase initiated January 1, 2015 |

— |

34 |

34 |

|

Increases license–exempt rate from 60 percent to 65 percent of family child care home rates starting October 1, 2015 |

— |

18 |

18 |

|

Provides 1.02 percent COLA to Standard Reimbursement Rate |

6 |

8 |

14 |

|

Increases part–day State Preschool rate 1 percent starting July 1, 2015 |

6 |

— |

6 |

|

Subtotals |

($50) |

($127) |

($177) |

|

Slots |

|||

|

Provides 6,800 Alternative Payment Program slots starting July 1, 2015 |

— |

$53 |

$53 |

|

Provides 7,030 full–day State Preschool slots starting January 1, 2016a |

$31 |

3 |

34 |

|

Annualizes funding for 4,000 full–day State Preschool slots initiated June 15, 2015 |

15 |

19 |

33 |

|

Provides 2,500 part–day State Preschool slots with priority for children with disabilities starting July 1, 2015 |

12 |

— |

12 |

|