In This Report

LAO CONTACTS

K-12 Education in Context

Overview of the Governor's Budget

Local Control Funding Formula,

Special Education

Preschool Restructuring

Education Mandates,

Teacher Workforce Trends

County Offices of Education,

High Speed Network

February 18, 2016

The 2016-17 Budget

Proposition 98 Education Analysis

Executive Summary

Overall Proposition 98 Budget Plan

Governor’s Budget Increases Proposition 98 Funding Significantly. Proposition 98 funds preschool, K–12 education, the California Community Colleges (CCC), and adult education. The Governor’s budget includes $4.3 billion in Proposition 98 funding increases, with the largest augmentation ($2.8 billion) for implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) for school districts and charter schools. For community colleges, the largest proposals are $255 million for deferred maintenance and instructional equipment and $200 million for a new CCC workforce development program.

Governor’s Estimates of Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee Reasonable. The Governor’s budget plan contains multiyear estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. We believe these estimates are a reasonable starting point for budget deliberations. Changes in state General Fund revenue, however, will affect estimates of the guarantee over the period. Whereas revenue changes will have an almost dollar–for–dollar effect on the guarantee in 2014–15, the guarantee is relatively unaffected by revenue changes in 2015–16, and the 2016–17 guarantee likely will change about 50 cents for every $1 change in state General Fund revenue.

Governor’s Local Property Tax Estimates Likely Too Low. Though the administration’s estimates of the minimum guarantee appear reasonable to us, we think the administration’s estimate of local property tax revenue is around $1.1 billion too low across the 2015–16 and 2016–17 period. This is primarily due to differences in our estimates of redevelopment–related revenue and growth in assessed property values. Though higher local property tax revenue would not affect overall Proposition 98 funding, it would free up a corresponding amount of non–Proposition 98 General Fund.

Governor’s Budget Has Relatively Small Cushion. As in the past few years, a key budget decision this year concerns the amount of 2016–17 funding allocated to one–time versus ongoing purposes. The Governor allocates $520 million (about 1 percent of 2016–17 Proposition 98 spending) to one–time purposes. The Legislature could consider designating a larger amount for one–time purposes to provide a greater cushion in the event of a future economic slowdown.

Specific Proposition 98 Proposals

Recommend a Preschool Restructuring Approach That Links Funding to Children. The Governor proposes to redirect $1.6 billion in Proposition 98 funds from three existing preschool programs to create a new block grant intended to benefit low–income and at–risk four–year olds. The block grant would be given to local education agencies (LEAs) and potentially other entities based on historical funding allocations and local need. The administration would develop the remaining aspects of the program over the next few months. Though we think the Governor’s general approach of consolidating existing programs and prioritizing the neediest children is promising, we are concerned that basing funding on historical allocations would work counter to keeping funding linked to children. We recommend the Legislature create a single, coherent program that would serve all low–income and at–risk children, provide a uniform per–child funding rate, offer a full–day option for working families, and include developmentally appropriate activities.

Recommend Creating a Plan for Retiring the Mandate Backlog. The Governor proposes to allocate $1.4 billion towards paying down the K–14 mandate backlog ($1.3 billion to schools and $76 million to community colleges). While the per–student funding approach is consistent with prior years and initially had notable advantages, it can practically never retire the entire K–14 backlog. As an alternative, we recommend the Legislature create a $2.6 billion plan to retire the backlog over the next two or three years (depending on the availability of one–time funding). Participating school districts and county offices of education (COEs) would receive per–student funding based on the statewide median claim ($450 per student), with an additional allocation to COEs based on the number of students within the county ($20 per student) and a minimum COE payment of $1 million. As a condition of accepting funding, participating LEAs would write–off all outstanding claims through 2015–16.

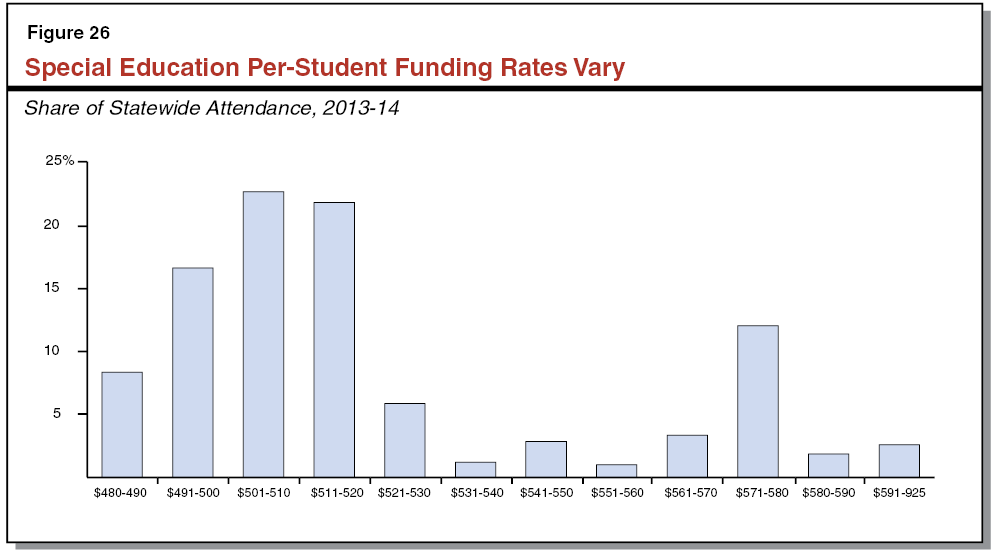

Funding Inequities in Special Education Going Unaddressed. The administration has no specific proposal on special education equalization. Existing per–student special education funding rates, however, vary widely across the state, and these differences affect local contributions to special education as well as the amount of resources remaining for general education. We recommend equalizing special education funding rates over the next few years in tandem with LCFF implementation.

Services for Infants and Toddlers With Disabilities in Need of Comprehensive Reform. The Governor removes a $30 million ongoing augmentation that the state had provided last year for LEAs serving infants and toddlers with disabilities. He removes the funding because no agreement could be reached on how to use the funds. The state’s existing approach to serving these children is outdated and overly complex. We recommend the Legislature undertake a comprehensive review of this program with the intent of pursuing a major restructuring in future years.

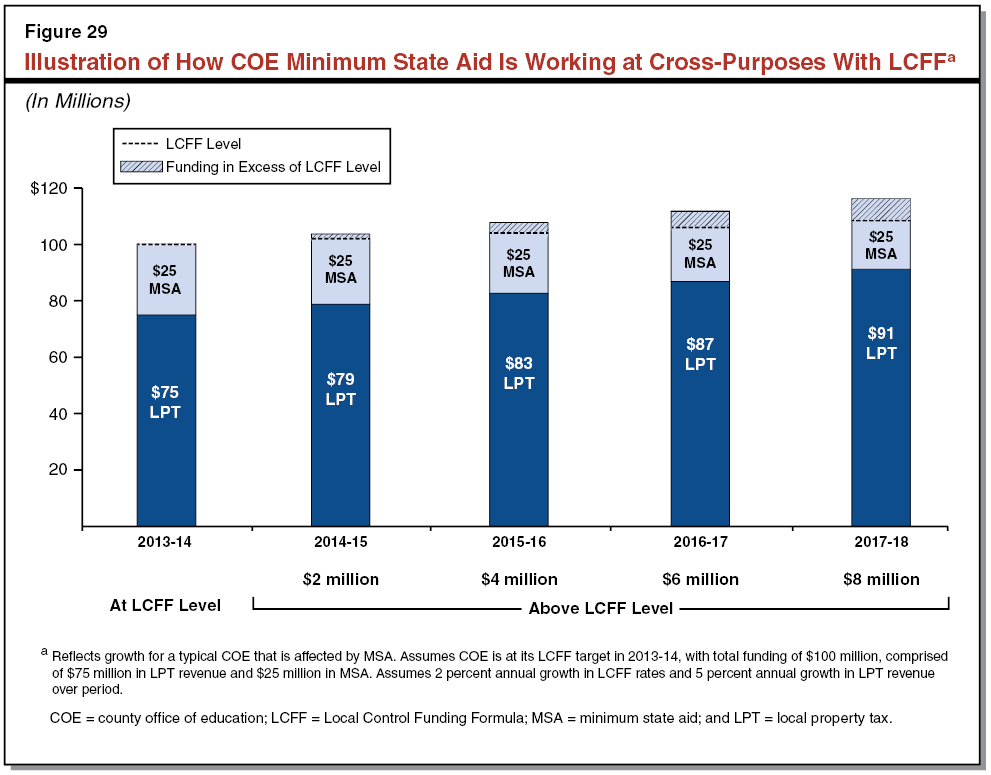

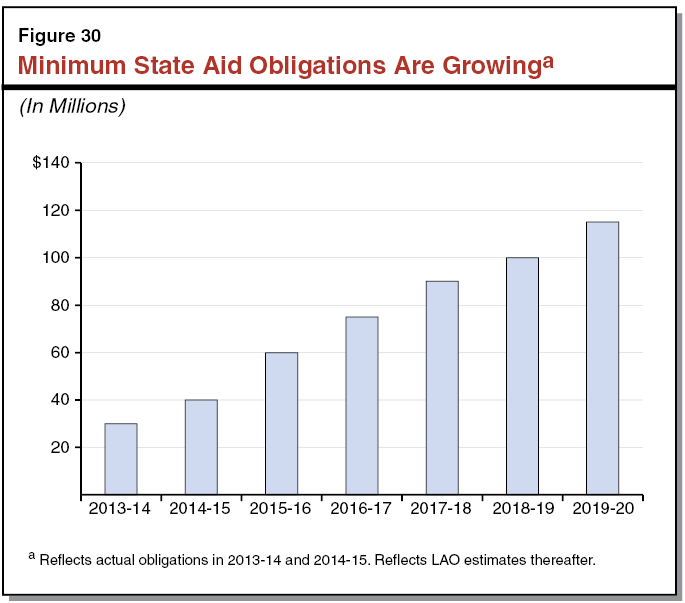

Governor’s COE Cost Estimates Highlight Need to Address Larger LCFF Design Flaw. We believe that the administration underestimates LCFF costs for some COEs by a total of $20 million in 2015–16 and $35 million in 2016–17. The shortfall is related to how the state funds COEs under the “minimum state aid” provision of LCFF. We believe this provision is a fundamental design flaw of LCFF that works at cross–purposes to the formula’s intent by creating new and growing funding differences among COEs. We recommend the Legislature repeal the provision. Doing so would free up $40 million (Proposition 98) in 2016–17 and save tens of millions of dollars every year moving forward.

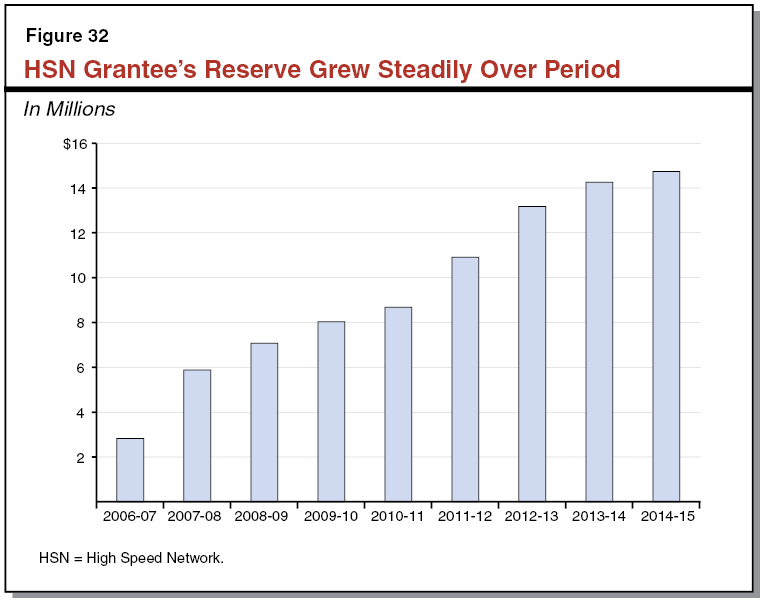

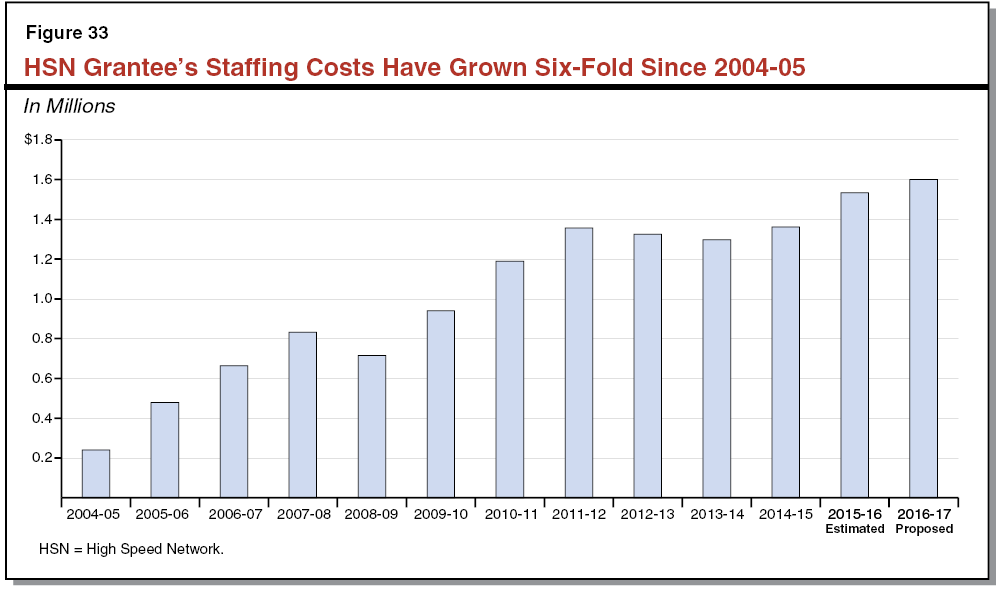

Recommend Rethinking Governor’s Proposal for Funding High Speed Network (HSN) Grantee. The Governor proposes providing the HSN grantee $19.3 million in 2016–17 expenditure authority. Of this amount, $8 million would come from Proposition 98 General Fund. We are concerned that the proposal would allow the HSN grantee to carry a reserve of $8.8 million without adequate justification and that the proposal does not include a plan for “right–sizing” the grant to meet present–day expectations. We recommend the Legislature provide no General Fund appropriation to the grantee in 2016–17, instead requiring the grantee to fund its 2016–17 operations using its reserves, leaving a $1.4 million reserve at year end. We also recommend the Legislature ask CDE to report about the performance and cost–effectiveness of the HSN grantee at spring budget hearings.

Introduction

Proposition 98 funds subsidized preschool, elementary and secondary education, and community colleges. In this report, we analyze the Governor’s Proposition 98 budget package. In the first section, we provide background on public schools in California. (We provide background on community colleges in our forthcoming Higher Education Budget Analysis.) In the second section, we provide background on Proposition 98 and the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee. We next describe and assess the Governor’s estimates of the minimum guarantee and his corresponding overall Proposition 98 spending package. In the remaining sections of the report, we describe and assess the Governor’s specific Proposition 98 proposals.

K–12 Education in Context

In this section, we answer many questions legislators and others commonly ask about K–12 education in California. We begin with a focus on the main components of California’s public school system, then turn to the state’s academic standards and student performance on standards–aligned assessments, and finish by explaining the basics of school finance in California.

California’s Public School System

Below, we describe California’s students, teachers, local education agencies, and state education agencies.

Students

California Has More Than 6 Million Public K–12 Students. In 2014–15, California’s public schools enrolled a total of 6.2 million students, representing 13 percent of all public school students in the nation. About two–thirds of these students were in grades kindergarten through eight, with one–third attending high school. Over the past decade, student enrollment has been virtually flat, with enrollment in 2014–15 about 1 percent below the 2004–05 level. Enrollment in the preceding decade, however, grew rapidly, with growth averaging 2 percent per year between 1994–95 and 2004–05. Over this earlier decade, statewide enrollment grew by nearly 1 million students.

Almost Six in Ten California Students Are From Low–Income Families. In 2014–15, 59 percent of California’s public school students were eligible to receive a free or reduced price school meal under a large federal nutrition program. States frequently use this eligibility measure as an indicator of student poverty. Qualifying students come from families earning no more than 185 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2014–15, this level equated to $45,000 for a family of four. California’s rate of free or reduced price meal eligibility is above the nationwide rate of 50 percent.

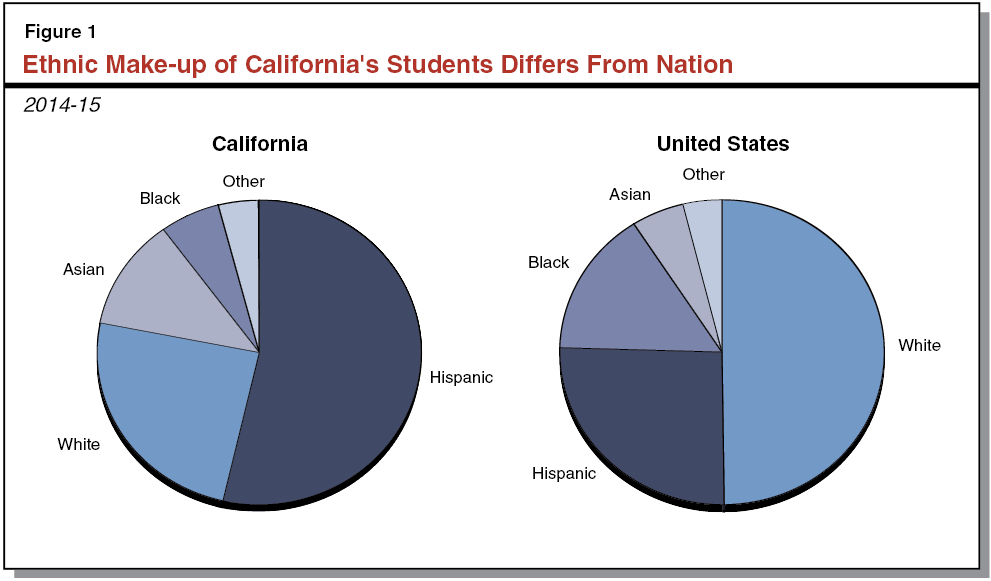

Half of California Students Are Hispanic. As shown in Figure 1, the ethnic make–up of California’s students differs notably from the nationwide picture. Whereas half of California’s students are of Hispanic origin and about one–quarter are white, in the United States those shares are flipped. Differences exist among other ethnic groups too, with Asian students comprising a larger share of students in California than the nation (12 percent and 5 percent, respectively), and black students comprising a smaller share (6 percent in California compared to 15 percent nationwide).

Nearly One–Quarter of California Students Are English Learners. In 2014–15, 22 percent (1.4 million) of California students were classified as English learners—a higher proportion than in any other state. One out of every three English learners in the nation attends school in California. Even more California students—almost 2.7 million students overall—speak a primary language other than English at home, but almost half of these students are considered fluent in English. California students come from families speaking over 60 different home languages, although the vast majority (78 percent) speak Spanish, with Vietnamese the next most common language (3 percent).

One in Ten California Students Are Identified as Having a Disability Affecting Their Education. In 2014–15, about 647,000, or roughly 10 percent of K–12 students in the state, were identified with a disability affecting their education. Pursuant to federal law, schools must provide these students with special education services. California identifies a slightly smaller proportion of students for special education than the rest of the nation (13 percent). Specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia are the most common diagnoses requiring special education services (affecting 4 percent of the state’s K–12 students), followed by speech and language impairments (affecting 2 percent of California’s students). While the overall prevalence of students with autism and chronic health problems still is relatively rare (each affecting about 1 percent of California’s students), the number of students diagnosed with these disabilities has increased notably over the last decade.

Teachers

California Has Almost 300,000 Teachers. In 2014–15, about 296,000 teachers were employed in the public school system. Roughly three–quarters of teachers are women, similar to the share in other states. Compared to the student population, teachers are more likely to be white (68 percent of teachers compared to 25 percent students) and less likely to be Hispanic (19 percent of teachers compared to 54 percent of students). The number of teachers decreased during the last economic recession, dropping from 310,000 in 2007–08 to 284,000 in 2011–12. Since 2011–12, the number of teachers has increased each year.

California’s Credentialing Requirements Are Similar to Those in Other States. To obtain a first–time teaching credential in California, individuals must have a bachelor’s degree, complete a teacher preparation program, meet certain basic skills requirements, and demonstrate subject matter competency. Within five years of receiving their initial credentials, teachers must complete approved, two–year, on–the–job training programs to obtain their full professional credentials. Most other states have similar requirements. Fully credentialed teachers from other states who want to work in California typically are granted in–state credentials conditionally, having to fulfill certain California–specific requirements (including a basic skills requirement and a requirement relating to teaching English learners) within a set amount of time.

Four in Ten Teachers in California Have Advanced Degrees. In 2014–15, less than 1 percent of California’s teachers held less than a bachelor’s degree, 57 percent possessed a bachelor’s degree, and 42 percent had a master’s degree or other advanced graduate degree. The share of teachers with a master’s or other advanced graduate degree has increased by almost 10 percentage points over the past ten years.

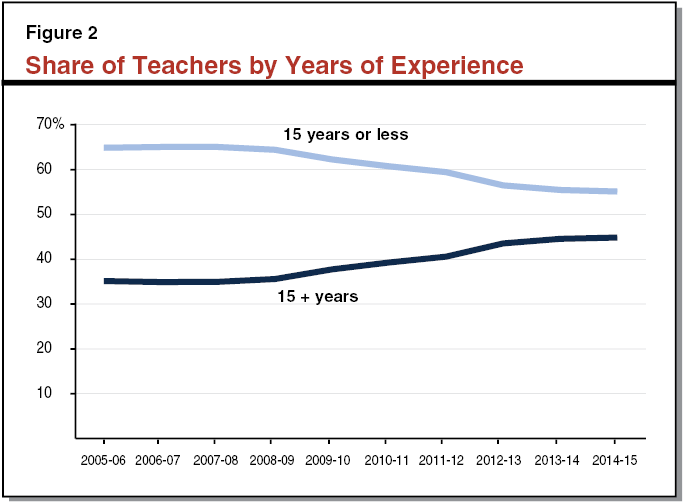

Average Years of Teaching Experience Have Steadily Increased Over Last Decade. In 2014–15, California’s teachers had an average of 14 years of experience. This is higher than ten years ago, when teachers had an average of 13 years of experience. As shown in Figure 2, the share of teachers in California with 15 or fewer years of experience has steady declined (from 65 percent in 2005–06 to 55 percent in 2014–15), whereas the share with more than 15 years of experience has steadily increased (from 35 percent in 2005–06 to 45 percent in 2014–15).

California’s Teacher Salaries Higher Than Most Other States. Based upon the most recent national data, California has the third highest average teacher salary. Its average teacher salary in 2013–14 was 26 percent higher than the national average. California consistently has ranked in the top four of states, having the highest average teacher salary of all states three of the last ten years.

Teacher Salaries Vary Significantly Across the State. In California, the state requires most LEAs to set teacher salary levels through collective bargaining. The average teacher salary in California in 2014–15 was $71,400, but teacher salary levels varied widely across the state. Orange County had the highest average salary at $81,000, whereas Siskiyou County had the lowest salary at $55,200. Average teacher salaries tend to be higher in urban counties, such as San Mateo ($74,500), Los Angeles ($72,400), and San Diego ($71,700), and lower in rural counties, such as Shasta ($60,900) and Sierra ($56,500).

California Has Among Highest Student–to–Teacher Ratio in Nation. Though California’s teachers tend to be better paid than the rest of the nation, the state employs comparatively fewer of them. Based upon the most recent national data, California had the highest student–to–teacher ratio. California’s average student–to–teacher ratio in 2012–13 was 23.7 to 1 compared to the national average of 16 to 1. The state’s student–to–teacher ratio consistently has been among the highest in the nation, even prior to the recent economic recession.

Local Education Agencies

School Districts, Charter Schools, and County Offices of Education Provide Instruction to Students. The public school system is comprised of many local education agencies (LEAs). In 2014–15, 947 school districts, 1,173 charter schools, and 58 county offices of education operated in California. California’s public school system also includes three state special schools for certain blind and deaf students as well as four Division of Juvenile Justice facilities for incarcerated students.

Size of California School Districts Varies Dramatically. As shown in Figure 3, California’s 947 school districts vary greatly in size. One–quarter of school districts are very small, serving 300 or fewer students. Another one–third are small, serving between 301 and 2,500 students. Whereas these two sets of districts combined comprise more than half of all districts in California, they account for only 7 percent of all students. At the other extreme, 13 very large districts each serve more than 40,000 students and together educate about one–fifth of all students in the state. The largest district in California (and the second largest in the nation) is the Los Angeles Unified School District, serving 9 percent of all California students. Seven of the state’s counties contain only a single school district, and 201 school districts contain only a single school. At the other extreme, Los Angeles County contains 80 school districts and the Los Angeles Unified School District contains almost 800 schools.

Figure 3

California School Districts Vary Greatly in Size

2014–15

|

District Size |

Number of Districts |

Percent of All Districts |

Total Students |

Percent of All Students |

|

6 to 300 |

238 |

25% |

28,970 |

1% |

|

301 to 2,500 |

308 |

33 |

335,323 |

6 |

|

2,501 to 5,000 |

136 |

14 |

490,730 |

9 |

|

5,001 to 10,000 |

116 |

12 |

863,800 |

16 |

|

10,001 to 40,000 |

136 |

14 |

2,593,579 |

47 |

|

40,000+ |

13 |

1 |

1,172,038 |

21 |

|

Totals |

947 |

100% |

5,484,441 |

100% |

|

Note: Based on average daily attendance. Excludes charter school attendance. |

||||

Charter Schools Are Fast–Growing Sector of California’s K–12 School System. An increasing share of California students attend charter schools. Charter schools are publicly funded schools that are similar to traditional schools in many ways—they must employ state–certified teachers, and they must teach and assess students based on the same state academic standards. They differ from traditional district–operated schools, however, in that they are exempt from certain laws, allowing them more flexibility over the design of their education programs. While overall K–12 enrollment has been relatively flat over the past decade, the number of students attending charter schools has more than tripled, growing at an average rate of 12 percent each year. In 2014–15, charter schools served 545,000 students (9 percent of the statewide total). Charter schools ranged in size from 7 students to more than 5,000 students, with an average school size of 444.

County Offices of Education (COEs) Operate Regional Programs and Services. Specifically, they operate alternative programs for students who are incarcerated, on or referred by probation, or have been mandatorily expelled by their district of residence. Many COEs also operate regional special education and career technical education programs. In addition, COEs offer a variety of regional services to support school districts. Most COEs, for example, operate countywide payroll systems and provide professional development for teachers and administrators. The COEs also are required to review and approve school districts’ annual budgets, monitor the fiscal health of districts twice per year, and review districts’ strategic plans, known as Local Control and Accountability Plans.

State Education Agencies

California Department of Education (CDE) Administers Education Programs at the State Level. The department is the primary state entity responsible for administering federal and state education programs. The department monitors compliance with laws and regulations for education programs; collects and compiles data related to districts, schools, and students; allocates funding; and monitors state contracts for student testing. The department has an annual budget of around $250 million and about 1,500 employees—rendering it midsized compared to other departments within California state government. More than two–thirds of CDE’s funding comes from federal funds, as most of CDE’s activities are associated with federal programs. The Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI) oversees the day–to–day operations of CDE. In California, the SPI is a non–partisan position elected by voters. This contrasts with most other states in which the officers heading their departments of education typically are appointed by their governors or state boards of education.

Three Other State Agencies Involved in Aspects of K–12 Education. In addition to CDE, the following three state entities are involved in major aspects of K–12 education.

- The State Board of Education (SBE), consisting of ten members appointed by the Governor, is responsible for setting and implementing various state policies, including developing regulations needed to implement state laws involving K–12 education, granting LEAs waivers from certain requirements in state law, selecting a contractor for the state’s standardized tests, and adopting instructional materials for kindergarten through grade eight.

- The Commission on Teacher Credentialing is responsible for accrediting teacher preparation institutions to ensure those institutions have met minimum standards; credentialing teachers to ensure those individuals have met minimum training requirements; and monitoring teacher conduct to ensure teachers conduct themselves appropriately.

- The State Allocation Board allocates bond funding for the construction and modernization of public school facilities. Prior to receiving state bond funding, school facility projects must be reviewed and approved by the Office of Public School Construction, an office within the Department of General Services.

A Few Entities Tasked With State–Level Functions. In addition to these state entities, the state contracts with a few entities (via their COEs) to undertake activities that have statewide benefits. The Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (affiliated with the Kern COE) provides fiscal advice, management assistance, and other training to school districts across the state. California School Information Services (also affiliated with the Kern COE) helps LEAs across the state with data management issues. The K–12 High Speed Network (affiliated with the Imperial COE) assists schools with connectivity to Internet2 (a network reserved mostly for education institutions). The California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (affiliated with the Riverside COE), established by the state in 2013 and in the midst of development, will serve as a hub of expertise for helping LEAs improve student outcomes.

Policy and Performance

Below, we focus on major state and federal laws affecting K–12 education and then turn to student performance.

Law and Regulations

State and Federal Law Governs Large Portion of K–12 Education. Much of school operations are dictated by state and federal law. For example, the state sets caps on the size of elementary and middle school classrooms, requires a minimum of 180 instructional days per year, and sets minimum course requirements for high school graduation. State law also requires LEAs to implement state–adopted academic standards, administer state–approved student assessments, and report certain student performance outcomes. In addition to state law, federal law places, as a condition of receiving funding, several major requirements on schools. Most notably, the federal government requires schools to provide special education services and requires annual testing in certain subjects and grade levels. The federal government also funds various programs that have specific requirements associated with them. For example, if a school district accepts a federal Title I grant, then it must demonstrate that the funds are used for supplemental services for low–income students. (As highlighted in the nearby box, the federal government recently reauthorized the legislation governing much of its K–12 education requirements.)

President Signs Every Student Succeeds Act on December 10, 2015

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) is the main federal legislation affecting K–12 education. The act supersedes the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, enacted in 2002 and up for reauthorization since 2007. As with NCLB, the ESSA sets specific requirements for states to test students in English language arts, math, and science; report testing data by specified student subgroups (including low–income students); and identify and intervene in their lowest–performing schools. The ESSA most notably differs from NCLB in that it provides states with flexibility to develop their own accountability systems and decide for themselves what actions they will take to improve low–performing schools and districts. By comparison, NCLB was much more prescriptive in dictating specific school turnaround strategies that states were to implement.

The SBE Is Responsible for Developing State Regulations. In many instances, state law delegates important policy decisions to the board. In 2014, for example, the board adopted regulations that specified how LEAs could spend certain revenues from the Local Control Funding Formula. The board also is in the midst of considering various issues relating to the state’s new accountability system, including whether to modify or replace the Academic Performance Index (a summary measure of academic performance), what to include in the evaluation rubrics COEs are to use to monitor school district performance, and how to integrate the state’s accountability system with recently adopted changes in federal law.

Academic Standards

The SBE Adopted California’s First Set of Academic Content Standards in the Late 1990s. As required in state law, these academic content standards were to specify what students should know after completing each subject area in each grade level. California first adopted academic content standards for its core content areas—English language arts, math, science, and history–social science—in 1997 and 1998. The state subsequently adopted standards for English language development (used for instructing English learners), visual and performing arts, physical education, career technical education, and world languages. The Instructional Quality Commission, an advisory body to SBE, created associated curriculum frameworks that provided examples of lesson plans aligned with the content standards.

Like Most States, California’s Instruction Now Based on Common Core State Standards. In 2010, at the direction of the state Legislature, the SBE adopted the Common Core State Standards (with the addition of a few California–specific standards) as the new foundation for what students should know and be able to do in English language arts and math from kindergarten through twelfth grade. The new standards are designed to be better at preparing students for college and career. California schools are implementing the new standards by modifying curriculum, conducting professional development for staff, and purchasing new instructional materials. Forty two states and the District of Columbia also have adopted and are implementing the Common Core State Standards.

State in Process of Implementing New Science Standards. California also adopted the nationally developed Next Generation Science Standards in 2013. (California was a lead state partner in the development of these new standards.) Because the state has yet to develop curriculum frameworks or new exams aligned with NGSS, instruction in the classroom is not yet aligned to the new science standards.

Student Assessments

Federal Law Requires States to Administer Standardized Tests. Federal law requires states to assess students in English language arts and math in grades 3 through 8 and at least once from grades 10 through 12. In addition, federal law requires states to assess students in science at least once during: (1) grades 3 through 5, (2) grades 6 through 9, and (3) grades 10 through 12. States also are required to annually assess the English proficiency of English learners. From 2003 through 2013, most students in California were assessed using the California Standards Tests (CSTs) in these subjects, which were aligned to the state’s first set of academic standards. (Students with moderate or severe disabilities were assessed using alternative assessments.)

First Exams Aligned to Common Core Administered in Spring 2015. Although the Common Core State Standards were adopted by SBE in 2010, schools were not expected to have their instruction aligned with the new standards until 2014–15, at which time the state was to administer a new set of Common Core–aligned assessments. The new assessments were developed by the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), a group of 18 member states, with California a lead member. The SBAC assessments are intended to be taken online using a computer or tablet (though schools have a pencil–and–paper option for the first three years). Compared to the state’s previous exams, which consisted almost exclusively of multiple choice questions, the SBAC assessments contain some open–ended responses. For example, both English language arts and math exams include performance tasks that require students to review source materials and respond in writing to several questions.

State in Process of Developing Several New Exams. Over the next several years, the state plans to develop additional assessments aligned with the Common Core State Standards. Specifically, the state plans to develop new assessments for students with disabilities and new assessments in languages other than English. In addition, the state plans to develop new exams in science and English language development to replace existing exams that are aligned to older standards. The state also will consider whether to add other assessments. By March 1, 2016, the SPI must submit recommendations to SBE regarding whether the state should add assessments in social science, visual and performing arts, technology, or any other subject matter. The SPI also may consider whether additional assessments should be developed to supplement existing exams in English language arts, math, and science.

Student Performance

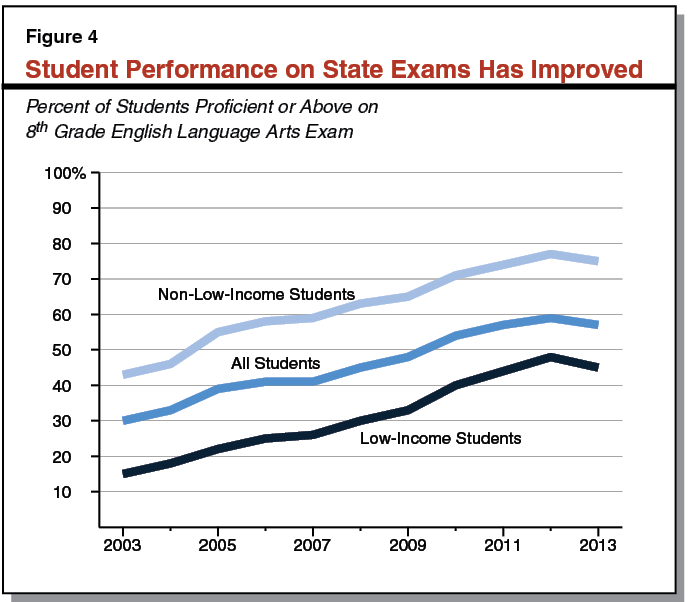

Student Performance on State Exams Improved From 2003 Through 2013. Student performance on the CSTs improved significantly during the ten years when the CSTs were administered. As Figure 4 shows, the percentage of students scoring advanced or proficient on the eighth grade English language arts exam almost doubled—from 30 percent to 57 percent—from 2003 to 2013. Performance improved at similar rates for both low–income and non–low–income students. Student performance also improved at similar rates in English language arts at other grade levels and on math exams. As part of the transition to new exams, California suspended the CSTs in spring 2014. Thus, no performance data is available for 2014.

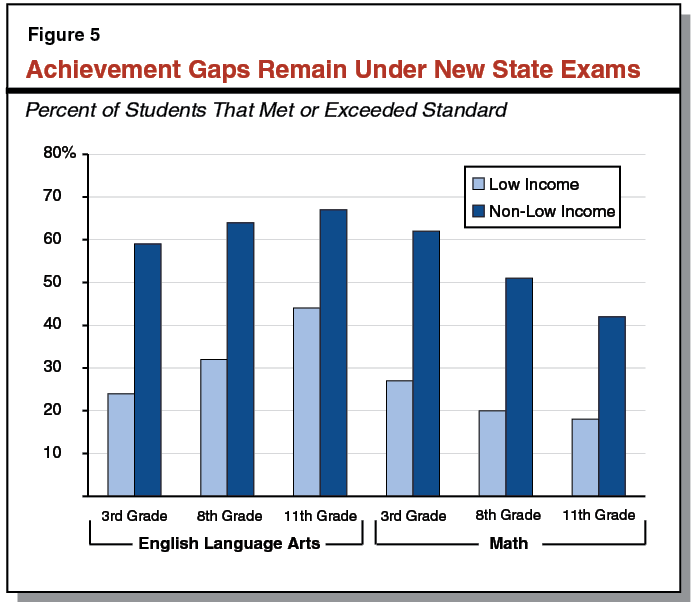

Large Achievement Gaps Remain Under New Assessments. The results of the new assessments in English language arts and math—the first year of results based on the new standards—were made public in September 2015. Statewide, 44 percent of California students met or exceeded standards in English language arts, whereas 33 percent met or exceeded standards in math. As Figure 5 shows, the results of the new exams show significant “achievement gaps”—the difference between the scores of low–income and non–low–income students. In eighth grade English language arts, for example, 64 percent of non–low–income students met or exceeded the state standards, compared to 32 percent of low–income students. These gaps are similar for other subjects and other grade levels and similar to achievement gaps under the prior exams (a difference of roughly 30 percentage points).

California Ranks Near Bottom on National Tests. Figure 6 shows California’s ranking on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a federal assessment conducted nationwide. As the figure shows, California performs near the bottom in tests of reading and math for fourth and eighth grades. Although the performance of non–low–income students tends to rank somewhat higher than that of low–income students, both groups perform lower than their peers in other states. California’s performance compared to other states has not changed significantly in the past ten years. In addition to having lower performance compared to other states, California also has among the largest achievement gaps between low–income and non–low–income students. In fourth grade reading, for example, California’s achievement gap is ranked 49th in the country. (That is, 48 states have achievement gaps that are smaller than California.)

Figure 6

California Ranks Near Bottom on National Testsa

California’s Ranking Among 50 States and District of Columbia

|

All Students |

Low Income Students |

Non–Low Income Students |

Achievement Gapb |

|

|

4th grade |

||||

|

Reading |

49 |

49 |

40 |

49 |

|

Mathematics |

48 |

51 |

39 |

49 |

|

8th grade |

||||

|

Reading |

44 |

45 |

39 |

37 |

|

Mathematics |

41 |

45 |

34 |

38 |

|

aBased on performance on the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress. Ranking compared to 50 states and District of Columbia. bAchievement gap is difference between score of non–low–income and low–income students. The state that is ranked 1 has the smallest gap. |

||||

Eight in Ten Students Graduate High School Within Four Years. Of the cohort of students that entered ninth grade in the 2010–11 school year, 81 percent graduated within four years, 12 percent dropped out of school, 7 percent returned to school for a fifth year, and less than 1 percent received either a High School Equivalency Certificate (if they passed the General Educational Development Test) or a special education certificate of completion.

Increasing Share of Graduates Complete Coursework Required for University Eligibility. In 2014, 42 percent of California students graduated high school having completed the coursework required to be eligible for admission to the University of California and California State University. This proportion has been gradually increasing over the last 20 years. In 1994, 32 percent of California high school graduates completed such coursework. (To meet the minimum eligibility requirements for the University of California and California State University, students also must meet certain grade point average requirements and take college entrance exams.)

Finance

Below, we discuss how schools are funded in California and how funds are allocated and spent at the local level.

School Funding

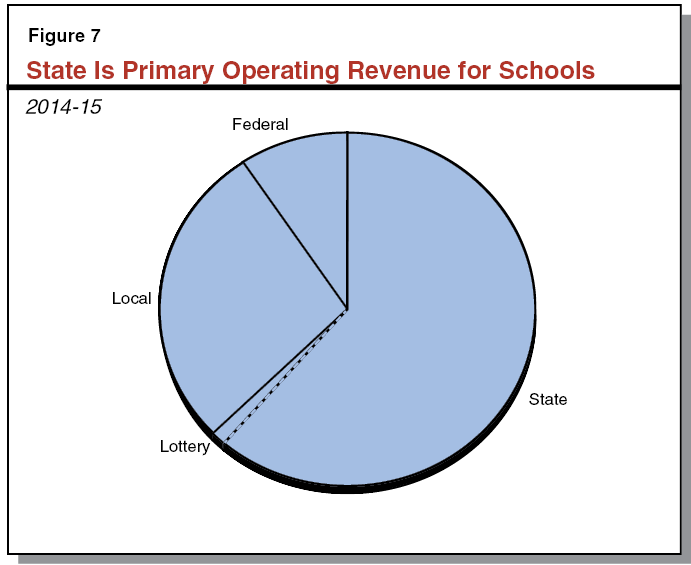

State Is Primary Source of Operating Revenue for Schools. In 2014–15, schools received $82 billion in total funding from all sources. As Figure 7 shows, the largest share of school funding comes from the state, with smaller shares coming from local sources (primarily from local property tax revenue) and the federal government. These proportions differ from many other states, where local property tax revenues cover a much larger share of school funding. (Unlike many other states, California’s State Constitution limits local property tax rates.) Additionally, in contrast to many other states, most school districts’ overall funding levels are not affected by how much local property tax revenue they receive. This is because California generally uses local property tax revenue as an offset for state General Fund spending. That is, if a district receives more local property tax revenue in a given year, the state reduces the district’s General Fund support by a like amount. About one in ten school districts in California, however, are affected by growth in their local property tax revenue, as they have such high levels of local revenue that the state provides no direct base aid.

Per–Pupil Funding in 2014–15 Exceeded Pre–Recession Level. For 2014–15, schools directly received $9,853 in state General Fund and local property tax revenue per student, about $200 (2 percent) above the 2007–08 pre–recession level adjusted for inflation. The 2015–16 Budget Act provided schools with $10,089 per student, a $200 (2 percent) increase from 2014–15.

California Per–Pupil Spending Ranks in Bottom One–Third of States. Based on data from 2012–13, California ranked 36th in per–pupil spending among the 50 states and District of Columbia. In 2007–08, prior to the most recent recession, California ranked 23rd in per–pupil spending. The drop in ranking over this period is primarily due to the reductions the state made during the recession. Because California’s revenues are highly sensitive to changes in the economy and financial markets, California’s budget tends to be more significantly affected by recessions (and recoveries) than most other states. Given California has made significant increases in K–12 funding over the past three years, its ranking likely will increase as newer data become available.

If Adjusted for Cost of Employment, California Drops in the Rankings. Some organizations produce rankings of state per–pupil spending with adjustments for regional costs. In these rankings, California typically ranks much lower. In one recent ranking, for example, California ranked 46th in per–pupil spending. The adjustments in these rankings are primarily intended to control for the variation in wages across the country, with average wages higher in California.

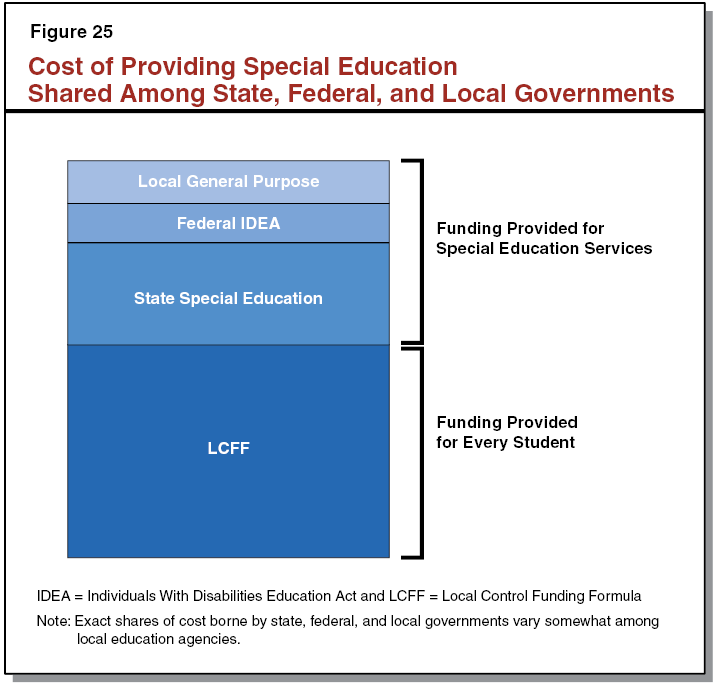

Allocation and Use of Funds

Most Funding Is Allocated Through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The 2015–16 budget plan allocated 90 percent of K–12 education funding (state General Fund and local property tax revenue combined) through LCFF. School districts and charter schools may use LCFF funds for any educational purpose, though they must use a portion of these funds for increasing or improving services for English learners and low–income students. In addition to general purpose LCFF funds, the state provides funding for various categorical programs, the largest being special education. (Categorical programs restrict funding for specified purposes.)

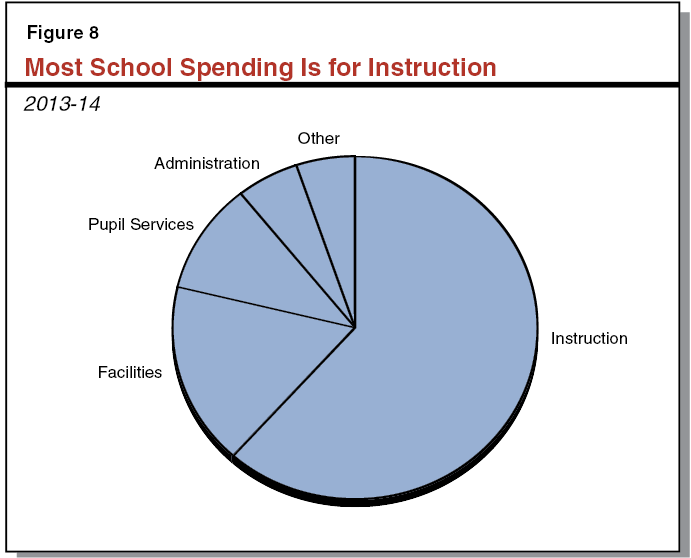

Most School Spending Is for Instruction. As Figure 8 shows, 62 percent of school expenditures in 2013–14 were related to instruction and instructional support—largely paying teacher salaries and benefits. Schools spent 17 percent of their funds on facilities, including land acquisition, construction, and maintenance. Schools spent 10 percent on pupil services, including school meals, pupil transportation, counseling, and health services. About 10 percent of funds were spent on central administration, including the compensation of superintendents; central business, legal, and human resource functions; and other expenses, including purchasing, printing, and data processing.

Back to the Top

Back to the Top

Overview of the Governor’s Budget

In this section, we describe how the state calculates its school funding obligation under Proposition 98; discuss changes in proposed funding and spending from 2014–15 through 2016–17; and examine some of the key issues facing the Legislature over the next few years.

Background on Calculating Minimum Guarantee

Proposition 98 Sets Minimum Funding Level for Schools and Community Colleges. State budgeting for schools and community colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by voters in 1988. The measure, modified by Proposition 111 in 1990, establishes a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges, commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. Both state General Fund and local property tax revenue apply toward meeting the minimum guarantee.

Various Inputs Determine Operative “Test.” As described in Figure 9, the minimum guarantee is determined by one of three tests set forth in the State Constitution. These tests are based on several inputs, including changes in K–12 attendance, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue. The operative test that sets the minimum guarantee is triggered automatically depending on these inputs. In most years, Test 2 or Test 3 has been the operative test, with the minimum guarantee building upon the level of funding provided the prior year. Since the inputs are not finalized until a few years after the close of the fiscal year, the operative test can fluctuate and the minimum guarantee can change significantly from the level initially assumed in the budget.

Figure 9

Constitution Sets Forth Three Tests for Calculating Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee

|

Test 1—Share of General Fund. Ensures Proposition 98 programs receive at least 40 percent of state General Fund revenue. This test applies only when it results in a higher funding level than Test 2 or Test 3. Test 1 has been operative 4 of the last 27 years. |

|

Test 2—Growth in Personal Income. Adjusts prior–year Proposition 98 funding for changes in K–12 attendance and per capita personal income. This test applies when higher than Test 1 but lower than Test 3. Test 2 has been operative 14 of the last 27 years. |

|

Test 3—Growth in General Fund Revenue. Adjusts prior–year Proposition 98 funding for changes in K–12 attendance and per capita General Fund revenue. This test applies when higher than Test 1 but lower than Test 2. Test 3 has been operative 7 of the last 27 years. |

|

Note: In 2 of the last 27 years, the state suspended Proposition 98. |

State Can Provide More Funding Than Required or Suspend Guarantee. During the economic boom that prevailed in the late 1990s, the state for several years provided more funding than was required by the minimum guarantee. Alternatively, in 2004–05 and 2010–11, the state applied a provision of Proposition 98 allowing for the suspension of the minimum guarantee upon a two–thirds vote of each house of the Legislature. When the state suspends the minimum guarantee, it can provide a lower level of funding but it creates an out–year obligation to restore K–14 funding in later years (as described below).

State Creates “Maintenance Factor” Obligation in Certain Years. Proposition 111 allows the state to provide less funding than the Test 2 level if Test 3 is operative or it suspends the minimum guarantee. In these years, the state creates a maintenance factor obligation, which is equal to the difference between the higher Test 2 level and the amount of funding actually provided. Moving forward, the maintenance factor obligation is adjusted annually for changes in K–12 attendance and per capita personal income. In subsequent years, when General Fund revenue is growing more quickly, the Constitution requires the state to make maintenance factor payments until this obligation has been paid off. The magnitude and timing of these payments is determined by formula, though stronger and faster revenue growth generally requires larger and more rapid payments. These maintenance factor payments increase the minimum guarantee on an ongoing basis.

Changes in Minimum Guarantee

As part of its budget package, the administration has updated its estimates of the minimum guarantee for 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17. Below, we describe these changes.

2014–15 Minimum Guarantee Up $387 Million From Budget Act Estimates. As shown in Figure 10, the administration’s revised estimate of the 2014–15 minimum guarantee is $66.7 billion, an increase of $387 million compared with the budget plan adopted last June. This upward revision largely reflects a $441 million increase in the amount of local property tax revenue received by schools and community colleges. (Because Test 1 is operative in 2014–15, increases in property tax revenue result in a higher overall Proposition 98 funding level rather than offsetting General Fund costs.) The increase in property tax revenue is due to higher–than–expected ongoing savings from the dissolution of redevelopment agencies ($303 million) and changes to several other components of local property tax revenue ($138 million). The administration also adjusts its estimate of the guarantee to reflect changes in a few other factors, including a $93 million reduction in General Fund tax revenue and slightly lower–than–expected growth in state population. These adjustments result in a $54 million reduction to General Fund Proposition 98 funding.

Figure 10

Updating Estimates of 2014–15 and 2015–16 Minimum Guarantees

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

||||||

|

June 2015 Estimate |

January 2016 Estimate |

Change |

June 2015 Estimate |

January 2016 Estimate |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

$49,608 |

$49,554 |

–$54 |

$49,416 |

$49,992 |

$575 |

|

|

Local property tax |

16,695 |

17,136 |

441 |

18,993 |

19,183 |

191 |

|

|

Totals |

$66,303 |

$66,690 |

$387 |

$68,409 |

$69,175 |

$766 |

|

|

Operative Test |

1 |

1 |

— |

3 |

2 |

— |

|

|

Key Factors |

|||||||

|

General Fund tax revenue |

$112,068 |

$111,975 |

–$93 |

$116,619 |

$120,205 |

$3,585 |

|

|

Maintenance factor payment |

$5,402 |

$5,392 |

–$10 |

— |

$810 |

$810 |

|

|

K–12 average daily attendance |

5,994,522 |

5,981,073 |

–13,449 |

5,995,889 |

5,976,227 |

–19,662 |

|

2015–16 Minimum Guarantee Up $766 Million from Budget Act Estimates. Also shown in Figure 10, the administration’s revised estimate of the 2015–16 minimum guarantee is $69.2 billion, an increase of $766 million compared with the budget plan adopted last June. This increase is due primarily to a $3.6 billion increase in General Fund tax revenue. Whereas the June budget plan assumed the state would make no maintenance factor payment in 2015–16, this higher revenue requires a maintenance factor payment of $810 million. The administration also revises its estimates of a few other Proposition 98 factors. These adjustments yield a net $44 million reduction in the guarantee. The most notable of these other revisions is for K–12 attendance. Whereas the June budget plan assumed attendance would grow by 0.02 percent from 2014–15 to 2015–16, the administration now estimates that K–12 attendance has declined 0.08 percent over the period. (Under a two–year hold harmless provision in the State Constitution, the change in K–12 attendance is deemed to be zero rather than negative.)

Under Revised Estimates, State Pays Off All Maintenance Factor by End of 2015–16. Upon making the $810 million maintenance factor payment, the state will have paid off all maintenance factor created during the last recession, leaving no maintenance factor outstanding for the first time since 2005–06. Paying off this obligation has two main implications. First, any additional increases in 2015–16 revenue will not result in a further increase to the guarantee. This dynamic contrasts notably with the situation in 2012–13 and 2014–15, under which additional revenue increased the guarantee nearly dollar for dollar. Second, paying off the maintenance factor created prior to July 1, 2014 is one of the conditions the state must meet before making a deposit into the state school reserve, thus triggering the capping of local districts’ reserves. Though the state likely now will meet this condition, we do not anticipate the state will meet the remaining conditions for making a deposit and capping school district reserves (as described later).

2016–17 Guarantee Up $3.2 Billion Over 2015–16 Budget Act Level. As shown in Figure 11, the Governor’s budget includes $71.6 billion in total Proposition 98 funding in 2016–17. This funding level is $3.2 billion (4.6 percent) above the 2015–16 Budget Act level and $2.4 billion (3.5 percent) above the revised 2015–16 level. Relative to the 2015–16 Budget Act level, several factors explain the higher 2016–17 guarantee. First, the $766 million upward adjustment in the 2015–16 guarantee carries forward, increasing the 2016–17 guarantee by a like amount. Second, Test 3 is operative in 2016–17, with the guarantee adjusted for the growth in per capita General Fund revenue. The administration estimates this growth at 2.4 percent. In combination with a 0.5 percent increase that applies automatically when Test 3 is operative, this growth results in the guarantee increasing by about $2 billion. Third, the state is required to make a $475 million supplemental appropriation to ensure the minimum guarantee grows at least as quickly as the rest of the state budget. (The supplemental appropriation is due to a state law adopted in 1990 and is required only when Test 3 is operative.) These three increases are offset by a 0.08 percent decline in K–12 attendance, which reduces the guarantee by roughly $25 million. (The constitutional hold harmless provision does not apply in 2016–17 because attendance declined in the two preceding years.) Despite the increase associated with these factors, the 2016–17 guarantee remains below the Test 2 funding level. As a result, the state creates $548 million in new maintenance factor.

Figure 11

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment and Source

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 Revised |

2015–16 Revised |

2016–17 Proposed |

Change From 2015–16 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

K–12 Educationa |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$44,496 |

$44,536 |

$45,442 |

$906 |

2.0% |

|

Local property tax |

14,834 |

16,560 |

17,802 |

1,242 |

7.5 |

|

Subtotals |

($59,330) |

($61,096) |

($63,244) |

($2,148) |

(3.5%) |

|

California Community Collegesb |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$4,979 |

$5,373 |

$5,447 |

$74 |

1.4% |

|

Local property tax |

2,302 |

2,624 |

2,812 |

188 |

7.2 |

|

Subtotals |

($7,281) |

($7,997) |

($8,259) |

($262) |

(3.3%) |

|

Other Agenciesc |

$80 |

$82 |

$83 |

— |

0.3% |

|

Totals |

$66,690 |

$69,175 |

$71,585 |

$2,410 |

3.5% |

|

General Fund |

$49,554 |

$49,992 |

$50,972 |

$980 |

2.0% |

|

Local property tax |

17,136 |

19,183 |

20,613 |

1,430 |

7.5% |

|

aIncludes State Preschool in 2014–15 and 2015–16 and proposed early education block grant in 2016–17. bIncludes $500 million for adult education regional consortia in 2015–16 and 2016–17. cConsists entirely of General Fund. |

|||||

60 Percent of Increase in 2016–17 Guarantee Covered by Higher Local Property Tax Revenue. Though the minimum guarantee grows by $2.4 billion from revised 2015–16 estimates to 2016–17, state General Fund spending grows by only $980 million (2 percent), whereas local property tax revenue increases by $1.4 billion (7.5 percent). As shown in Figure 12, this large increase in local revenue mainly results from two factors:

- Assessed Property Values Projected to Grow by 5.6 Percent. The largest source of local revenue for schools and community colleges is the 1 percent tax levied on the value of residential and commercial property. The administration projects that assessed property values will increase by 5.6 percent in 2016–17, similar to the average growth rate over the past 20 years. This increase equates to $929 million in additional property tax revenue.

- Final Shift of Revenue From End of “Triple Flip.” The triple flip began phasing out in 2015–16, with $1.3 billion in associated local property tax revenue flowing back to schools and community colleges. In 2016–17, schools and community colleges will receive an additional $419 million associated with the final quarter of this shift. (The triple flip was a complex financing mechanism under which the state diverted local sales tax revenue to pay off certain state bonds, backfilled cities and counties with property tax revenue, and backfilled schools and community colleges with state General Fund.)

Figure 12

Proposition 98 Property Tax Revenue Estimates

Reflects Governor’s Budget (Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 Revised |

2015–16 Revised |

2016–17 Estimated |

Change From 2015–16 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Local Property Tax Components |

|||||

|

Tax on assessed valuea |

$15,737 |

$16,616 |

$17,544 |

$929 |

5.6% |

|

End of “triple flip” |

— |

1,257 |

1,676 |

419 |

33.3 |

|

RDA ongoing revenue shift |

1,126 |

1,008 |

1,045 |

36 |

3.6 |

|

Other local revenueb |

1,069 |

998 |

1,039 |

41 |

4.1 |

|

Excess tax revenuec |

–796 |

–695 |

–690 |

5 |

–0.7 |

|

Totals |

$17,136 |

$19,183 |

$20,613 |

$1,430 |

7.5% |

|

aReflects school and community college allocations from the 1 percent property tax levied in each county. bLargely reflects the taxes levied on business property and property sold midyear. Also includes payments of delinquent taxes, one–time revenue associated with the sale of RDA assets, and several smaller taxes. cReflects revenue in “basic aid” districts and county offices of education that does not count toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. RDA = Redevelopment Agency. |

|||||

Changes in Spending

Governor’s Budget Package Includes $4.3 Billion in New Proposition 98 Spending. The Governor’s budget includes a total of $4.3 billion in additional spending related to increases in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. From an accounting perspective, $387 million is attributable to 2014–15, $766 million is attributable to 2015–16, $3.2 billion is attributable to 2016–17, and $257 million is a settle up payment related to meeting the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for 2009–10. In addition, the proposed budget repurposes $1.5 billion in Proposition 98 funding freed up from several expiring one–time 2015–16 initiatives. From a cash perspective, schools and community colleges will receive all of this funding in 2016–17. Below, we describe the Governor’s major Proposition 98 spending proposals.

Higher 2014–15 and 2015–16 Spending Largely Dedicated to Paying Down Mandate Backlog. The Governor proposes to dedicate $342 million of the available 2014–15 funding and $754 million of the available 2015–16 funding toward the K–14 mandate backlog. Of the combined $1.1 billion, schools would receive $1 billion and community colleges would receive $76 million. The Governor designates the remainder of available 2014–15 and 2015–16 funding for a few other purposes (including startup grants for new charter schools).

Largest Spending Proposals for 2016–17. Figure 13 summarizes the Governor’s Proposition 98 spending proposals for 2016–17. For schools, the Governor’s largest proposal is to provide $2.8 billion to continue implementation of LCFF. The next largest proposal is to provide $240 million for the Career Technical Education Incentive Grant for Secondary Schools. (The Governor also proposes $60 million in 2015–16 dollars for this purpose, bringing total program funding to $300 million.) Additionally, the Governor proposes a significant restructuring of the State Preschool and transitional kindergarten programs. For community colleges, the Governor’s largest proposal is to provide $255 million on a one–time basis for deferred maintenance and instructional equipment. The Governor also proposes $200 million to implement the recommendations of the Board of Governors (BOG) task force on workforce development and $115 million to increase community college enrollment by 2 percent.

Figure 13

2016–17 Proposition 98 Changes

(In Millions)

|

Revised 2015–16 Proposition 98 Spending |

$69,175 |

|

Technical Adjustments |

|

|

Remove prior–year one–time payments |

–$1,446 |

|

Make other adjustments |

–115 |

|

Adjust categorical programs for changes in attendance |

–16 |

|

Make LCFF adjustments |

101 |

|

Revise estimate of energy efficiency funds |

58 |

|

Annualize funding for previously approved preschool slot increases |

31 |

|

Subtotal |

(–$1,386) |

|

K–12 Education |

|

|

Increase LCFF Funding |

$2,825 |

|

Fund CTE Incentive Grant for Secondary Schools (year two of three) |

240a |

|

Provide 0.47 percent COLA for select categorical programs |

23 |

|

Fund truancy and dropout prevention program |

7 |

|

Fund High Speed Network |

5b |

|

Support Exploratorium |

4 |

|

Fund improvement of web–based tools for state accountability system |

1 |

|

Shift funding for transitional kindergarten and preschool into new block grant |

0 |

|

Remove prior–year augmentation for infants and toddlers with disabilities |

–30 |

|

Subtotal |

($3,073) |

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

Fund deferred maintenance and instructional equipment (one time) |

$255 |

|

Implement workforce recommendations of BOG task force |

200 |

|

Fund 2 percent enrollment growth |

115 |

|

Make CTE Pathways Initiative ongoing |

48 |

|

Augment Basic Skills Initiative |

30 |

|

Provide 0.47 percent COLA for apportionments |

29 |

|

Fund Innovation Awards at community colleges (one time) |

25 |

|

Increase funding for Institutional Effectiveness Initiative |

10 |

|

Fund development of “zero–textbook–cost” degree programs |

5 |

|

Improve systemwide data security |

3 |

|

Increase apprenticeship reimbursement rate |

2 |

|

Provide 0.47 percent COLA for selected student support programs |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($723) |

|

Total Changes |

$2,410 |

|

2016–17 Proposition 98 Spending |

$71,585 |

|

aBudget includes additional $60 million from other Proposition 98 funds. bBudget includes additional $3.5 million from other Proposition 98 funds. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula, COLA = cost–of–living adjustment, CTE = Career Technical Education, and BOG = Board of Governors. |

|

Other Proposals for 2016–17. The Governor’s budget also includes several smaller proposals. As shown in Figure 13, the budget provides a 0.47 percent cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) for several K–12 programs (including special education and child nutrition) as well as community college apportionments. Due to the recent drop in fuel prices, this COLA is well below the historical average of about 3 percent per year. For schools, the budget also proposes to allocate $7 million for truancy and dropout prevention, consistent with the requirements of Proposition 47. The budget also allocates $5 million in ongoing funding for the K–12 High Speed Network (HSN). (In 2015–16, the state required this program to fund its operations by drawing down reserves.) For community colleges, the budget provides (1) $48 million to make the CTE Pathways program permanent, (2) $30 million to augment the Basic Skills Initiative, (3) $25 million (one time) to fund Innovation Awards, (4) $10 million to increase funding for the Institutional Effectiveness Initiative, and (5) $5 million to create pathways that allow students to earn degrees and certificates with no textbook costs.

Increases in Funding Per Student. Under the Governor’s budget, K–12 Proposition 98 funding per student increases from a revised 2015–16 level of $10,237 to $10,605 in 2016–17, an increase of $368 (3.6 percent). Community college Proposition 98 funding per full–time equivalent (FTE) student increases from a revised 2015–16 level of $6,878 to $7,003 in 2016–17, an increase of $125 (1.8 percent).

Issues to Consider

Changes to Revenue Estimates Affect the Minimum Guarantee Differently Across the Period. The Governor’s budget assumes that General Fund tax revenue will be $112 billion in 2014–15, $120.2 billion in 2015–16, and $124.2 billion in 2016–17. Although we believe these estimates are a reasonable starting point for budget deliberations, they rely upon many assumptions about the national and state economy. In May, the administration will revise these estimates based upon the latest available economic data. Compared with current estimates, higher revenue would tend to increase the minimum guarantee whereas lower revenue would tend to reduce the guarantee. The exact effect, however, varies notably depending on the year in which the revenue changes occur. Below, we describe sensitivity of the guarantee to revenue changes in 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17.

- 2014–15 Guarantee Is Highly Sensitive. In 2014–15, Test 1 is the operative test for calculating the minimum guarantee and the state is making a large maintenance factor payment. Under these conditions, the guarantee changes virtually dollar for dollar with any change in revenue. Any increase in the guarantee, however, likely would not carry forward into 2015–16. This is due to a provision in the State Constitution known as “spike protection,” which effectively prevents large jumps in the guarantee from carrying forward into future years.

- 2015–16 Guarantee Is Relatively Insensitive. In 2015–16, Test 2 is operative and the state has paid off all maintenance factor. Relative to the administration’s estimates, state revenue could increase by as much as $7 billion with no increase in the guarantee. Conversely, state revenue could fall by as much as $1.3 billion with no decrease in the guarantee.

- 2016–17 Guarantee Is Moderately Sensitive. In 2016–17, Test 3 is operative and growth in the guarantee depends upon year–to–year growth in General Fund revenue. For every $1 dollar increase (decrease) in 2016–17 revenue, the guarantee would increase (decrease) by roughly 50 cents. Changes in 2015–16 revenue also could affect the 2016–17 guarantee. Counterintuitively, higher revenue in 2015–16 (all else constant) would reduce the guarantee in 2016–17 because it would lower the year–to–year growth rate. Lower revenue in 2015–16 would increase the guarantee in 2016–17 because it would raise the year–to–year growth rate.

Local Property Tax Estimates Likely Too Low in 2015–16 and 2016–17. We believe the administration’s estimate of local property tax revenue is $1.1 billion too low across the two–year period—$520 million too low in 2015–16 and $620 million too low in 2016–17. As described below, most of our differences with the administration are concentrated in two areas. (Our estimates for a few of the smaller components of property tax revenue also are slightly higher than what the administration projects.)

- Redevelopment–Related Ongoing Revenue. The administration estimates that the ongoing revenue shifted to schools and community colleges from former redevelopment agencies will be about $1 billion per year in 2015–16 and 2016–17. Based on increases in the tax increment allocated to the former redevelopment agencies and the repayment of redevelopment–related debt, we think revenue is likely to exceed the administration’s estimates by $330 million in 2015–16 and $364 million in 2016–17. (We believe the administration’s current forecast methodology systematically understates redevelopment–related revenue.)

- Assessed Property Values. The administration estimates that assessed property values will grow by 5.6 percent per year in 2015–16 and 2016–17. By contrast, we estimate growth of 6 percent in 2015–16 (based on the latest data submitted by county assessors) and 6.3 percent in 2016–17 (based on continuing growth in housing prices). Accounting for the higher growth rates, we think the associated tax revenue will exceed the administration’s estimates by about $100 million in 2015–16 and $200 million in 2016–17.

If local property tax revenue comes in higher than the administration estimates, Proposition 98 General Fund costs will be correspondingly lower and available non–Proposition 98 General Fund will be higher.

Recent Data Suggest Per Capita Personal Income Will Grow More Quickly Than Administration Projects. Federal data released in December 2015 suggest that per capita personal income will grow more quickly than the administration assumes in 2016–17. Whereas the administration assumes a growth rate of 4.4 percent, we believe growth could be around 1 percentage point higher based on this new information. Though the higher growth is unlikely to change the operative test or the minimum guarantee in 2016–17, it does mean the state likely will create more maintenance factor than the administration assumes. With a 5.4 percent growth rate, for example, the state would create a new maintenance factor obligation of about $1.3 billion, compared with the $548 million obligation assumed by the administration. This additional maintenance factor obligation would tend to increase school funding in future years.

Devoting Some 2016–17 Funding for One–Time Purposes Provides Cushion if Revenue Declines in Future Years. Though a recession does not seem imminent, the minimum guarantee could decrease in 2017–18 or future years if stock market prices were to drop or growth in the economy and personal income were to decline. Even a modest slowdown could reduce the 2017–18 minimum guarantee below the Governor’s proposed 2016–17 spending level. Such a scenario serves as a caution against the state committing all available Proposition 98 funding for ongoing purposes. The Governor’s budget dedicates $520 million of the funding within the 2016–17 minimum guarantee for one–time activities. This effectively reflects a cushion of less than 1 percent (0.7 percent). If the guarantee were to decline by more than this amount in 2017–18, the Legislature might have to reverse its progress toward LCFF implementation or make reductions to other ongoing programs. The Legislature could consider dedicating a larger share of 2016–17 funding for one–time activities to minimize the likelihood of such future reductions.

Proposals to Extend Proposition 30 Income Taxes Would Increase Minimum Guarantee. Proposition 30, approved by the voters in November 2012, temporarily increased personal income taxes for very high–income Californians. Though these taxes are scheduled to expire at the end of December 2018, a proposal is being circulated to extend them. We estimate that an extension would raise between $5 billion and $11 billion annually in the initial years of implementation, with the increase in 2018–19 around half of this amount, as half of the associated revenue raised in 2019 would be accrued to 2018–19. The large range in the estimate is due to the income volatility of high–income Californians. These individuals receive a large portion of their incomes from investments in the stock market and other sources that can vary notably from year to year. The additional revenue would increase the minimum guarantee, with the exact effect depending upon which Proposition 98 test were operative and how much maintenance factor were outstanding in 2018–19 and 2019–20. Under most of the economic scenarios we examined, the increase in the guarantee was roughly 50 cents for each dollar of revenue, though the exact effect ranged from as low as 20 cents to as high as 60 cents. For planning purposes, we think the Legislature could assume schools and community colleges would receive roughly half of any revenue increase associated with an income tax extension. For example, if the measure raised $4 billion in 2018–19 and an additional $4 billion in 2019–20 ($8 billion on an annual basis), the state might plan for the guarantee to increase by $2 billion in 2018–19 and an additional $2 billion in 2019–20 ($4 billion on an annual basis).

Deposits in State School Reserve Remain Unlikely in Near Term. A state law approved in 2014 imposes a cap on school district reserves in the year after the state makes a deposit into the state school reserve. Deposits are predicated on several conditions. Though we anticipate one condition will be satisfied in 2015–16 (having paid off all maintenance factor created before 2014–15), we do not anticipate the state will meet the other conditions within the next few years. For example, a deposit requires the minimum guarantee to be growing more quickly than per capita personal income. Under the projections released by our office in November and by the administration in January, this condition will not be met in 2016–17 or any of the following three years. To meet all of the conditions for a deposit, the state very likely would need to experience a year–to–year revenue surge of at least several billion dollars relative to these projections. Though an extension of the Proposition 30 income taxes would tend to increase state revenue, our projections indicate that this increase alone would not be large enough to meet all of the conditions for a deposit into the state school reserve in 2018–19 or 2019–20. Absent a larger surge, a deposit would not occur and the local reserve cap would not be triggered.

Recent Growth in School Funding Has Far Exceeded Initial Growth in Districts’ Retirement Contributions. School and community college districts are affected by both CalSTRS and CalPERS employer contribution rates. (CalSTRS administers the pension system for teachers and other certificated employees, whereas CalPERS administers the pension system for classified employees.) The 2014–15 budget package included a plan to fully fund the CalSTRS pension system over the next roughly 30 years. In the first few years of implementation, districts’ CalSTRS contribution rates increased from 8.25 percent of payroll in 2013–14 (before the start of the rate increases), to 8.88 percent in 2014–15, and to 10.73 percent in 2015–16. In addition to CalSTRS rate increases, the CalPERS board recently began increasing CalPERS contribution rates to move that system closer to full funding. Over this initial period of rate increases, district costs for these two pension systems have grown by more than $800 million (about 80 percent of which is related to CalSTRS increases). Over the same period, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee has increased by more than $10 billion.

Retirement Contributions Scheduled to Continue Rising While Growth in School Funding Projected to Slow. District retirement contributions are scheduled to continue increasing each year for the next five years. Under the statutorily established schedule, districts’ CalSTRS contribution rates are to reach 19.1 percent of payroll in 2020–21. CalPERS contribution rates, though not fixed in statute, also are expected to increase over this period. Compared to 2013–14 levels, districts’ CalSTRS and CalPERS costs are anticipated to be roughly $5 billion higher annually by 2020–21 due to the scheduled rate increases (with about three–quarters due to CalSTRS rate increases). Under various multi–year economic simulations, we found districts’ retirement cost increases accounted for between roughly one–quarter and half of the projected increases in school funding over the period.

Pension Rate Increases, Coupled With LCFF Implementation, Pose Certain Challenges for Certain Types of Districts. As the state implements LCFF, some districts, typically those with historically low per–pupil funding rates and/or high levels of poverty, are receiving larger annual funding increases than other districts. On the one hand, these districts may face somewhat less challenge in accommodating the pension rate increases. On the other hand, the state is requiring these districts to increase or improve their services for EL/LI students. These districts likely are experiencing tension in deciding how best to balance these two priorities (covering the pension rate increases and improving EL/LI services), along with all other priorities. Despite this tension, these districts still likely face somewhat less difficult choices than those districts with historically high per–pupil rates and/or low levels of poverty that are experiencing pension rate increases at the same time their annual allocations are growing slowly.

Back to the TopLocal Control Funding Formula

The largest proposal in the Governor’s budget is a $2.8 billion augmentation for implementation of LCFF. Below, we discuss the enactment of LCFF and the main components of the formula. We then describe and assess the Governor’s proposal.

Background

State Enacts New School Funding Formula in 2013–14. Legislation enacted as part of the 2013–14 budget package made major changes to the way the state allocates funding to school districts and charter schools. Previously, the state distributed school funding through revenue limits (general purpose grants) and more than 40 state categorical programs. Categorical programs had long constrained districts by requiring them to spend fixed amounts on prescribed activities. The state replaced the historical revenue limit and categorical funding system with a new system designed to be more flexible, student–oriented, and cost–driven.

New Formula Based on Student and District Characteristics. The LCFF has three primary components: base funding rates tied to four grade spans; supplemental funding for English learner, low–income, and foster youth (EL/LI) students; and concentration funding for districts with relatively high proportions of EL/LI students (more than 55 percent of their enrollment). As displayed in Figure 14, the base rates generally increase for higher grades in recognition of their higher costs—for example, providing career technical education in high school. (The K–3 rate is an exception to this rule. It is higher than the rates for grades 4–8, as it is intended to support smaller class sizes in the early grades.)

Figure 14

LCFF Target Funding Rates

Target Rates as Calculated in 2015–16a

|

Grade Spans |

Base Rates |

Supplemental Fundingb |

Concentration Fundingc |

|

K–3 |

$7,820 |

$1,564 |

$3,910 |

|

4–6 |

7,189 |

1,438 |

3,595 |

|

7–8 |

7,403 |

1,481 |

3,702 |

|

9–12 |

8,800 |

1,760 |

4,400 |

|

aDoes not reflect actual funding levels. State funded 90 percent of the target rates in 2015–16. bEquals 20 percent of the base rate. Generated for each district student who is a foster youth, an English learner, or low income (EL/LI). cEquals 50 percent of the base rate. When EL/LI students comprise more than 55 percent of total district enrollment, generated for each EL/LI student above that threshold. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

|||

An Illustration of Two Districts’ LCFF Calculations. Figure 15 shows the LCFF target calculation for two equally sized elementary school districts. Both districts generate the same amount of base funding given they serve the same number of students in the K–3 and 4–6 grade spans. Though they have the same attendance by grade span, District A has a notably higher share of EL/LI students compared to District B. As a result, District A generates more supplemental funding than the other district. Unlike District B, District A also generates concentration funding given its share of EL/LI students exceeds the 55 percent threshold. Given the difference in student demographics, District A receives a total of $430,000 more than the other district.

Figure 15

Illustration of LCFF Calculation for Two Elementary School Districtsa

|

District A |

District B |

Difference |

|

|

Attendance |

|||

|

K–3 |

100 students |

100 students |

— |

|

4–6 |

120 students |

120 students |

— |

|

EL/LI percentageb |

91% |

50% |

41% |

|

Grade span funding |

$1,645,000 |

$1,645,000 |

— |

|

Supplemental funding |

299,000 |

165,000 |

$134,000 |

|

Concentration funding |

296,000 |

— |

296,000 |

|

Totals |

$2,240,000 |

$1,810,000 |

$430,000 |

|

aReflects target rates as calculated in 2015–16. Rounded to nearest thousand. bEL/LI students as a share of total enrollment. LCFF=Local Control Funding Formula and EL/LI=English Learner/low–income. |

|||

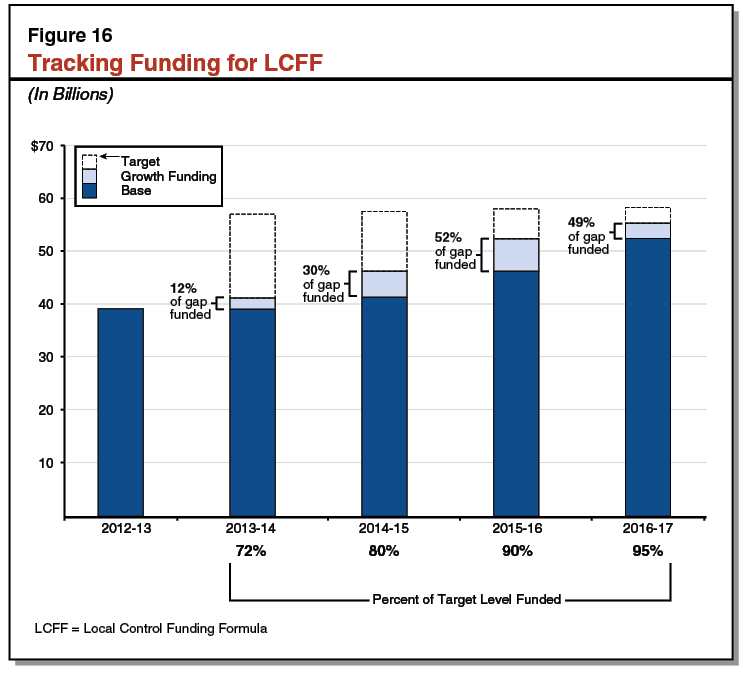

Implementation Expected to Take a Number of Years. When it enacted the new formula, the state set target per–pupil rates that were much higher than under the former system. Over the course of implementation, districts and charter schools will receive new funding based on the difference (or gap) between their prior–year funding level and their target LCFF funding level. Based on projections of growth in Proposition 98 funding, the administration estimated that the state would reach full implementation in 2020–21. Over the past three years, the state has provided $12.8 billion towards implementing the formula. As shown in Figure 16, the LCFF target level was 72 percent funded in 2013–14 and is 90 percent funded in 2015–16.