February 24, 2016

The 2016-17 Budget

Analysis of Child Care and Preschool Proposals

Executive Summary

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Governor’s Budget Includes $3.6 Billion for Child Care and Preschool Programs. The Governor’s budget augments existing child care and preschool programs by a total of $95 million (3 percent) from the revised 2015–16 level. The increase is due to various factors, including raising Transitional Kindergarten (TK) funding rates, annualizing the cost of preschool slots initiated last year, adding new slots for demographic growth, and applying cost–of–living adjustments to reimbursement rates. Under the Governor’s budget, proposed funding would support an estimated 455,000 child care and preschool slots. As part of his budget package, the Governor has two major restructuring proposals involving preschool and child care.

Preschool Restructuring

Governor Proposes to Restructure Preschool Programs. The Governor proposes to consolidate three existing preschool programs into a new $1.6 billion early education block grant intended to benefit low–income and at–risk preschoolers. Specifically, the proposal would redirect $845 million from the California State Preschool Program (CSPP), $726 million from TK, and $50 million from the CSPP Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) grant. Funds from the proposed block grant would be given to local education agencies and potentially other entities based on historical funding allocations and local need. Providers would set low–income eligibility criteria locally. The administration plans to develop the remaining aspects of the program—such as allowable providers, program standards, and funding rules—over the next few months.

While Governor’s Approach Targets Resources More Effectively, Funding Model Problematic. California currently has several programs serving preschool–aged children. These existing programs have different eligibility criteria and standards. Many preschool slots (those provided through TK) are not currently targeted to benefit low–income and at–risk children. This is a problem as low–income families are both less likely than higher–income families to be able to afford preschool and more likely to benefit from it (according to most research). At–risk children who have had adverse early childhood experiences also are likely to be able to benefit from supportive preschool environments. For these reasons, we think the Governor’s proposal to consolidate preschool funding into one program prioritized for low–income and at–risk children is an improvement over the current system. We are concerned, however, that allowing income eligibility to be defined locally and basing funding on historical allocations would create inequities among school districts in terms of who is served and how much funding districts have for each child. For example, school districts that previously operated similarly sized TK programs would have the same amount of resources to serve potentially different numbers of low–income and at–risk children.

Recommend a Preschool Restructuring Approach That Links Funding to Children. We recommend the Legislature create a single, coherent preschool program designed to provide access to all low–income and at–risk children (as defined by the Legislature) and offer a full–day option for working families. We also recommend the Legislature provide a uniform per–child funding rate and distribute funds based on the number of eligible children participating in the program. Additionally, we recommend providing substantial local flexibility on program implementation but requiring all programs to include developmentally appropriate activities, meet minimum state staffing requirements, and report some key information to the state.

Child Care Restructuring

Governor Initiates Five–Year Plan for Transitioning All Subsidized Child Care to Voucher System. Currently, the state offers child care through a mix of direct contracts with providers and vouchers that families can use for various child care arrangements. The Governor has proposed trailer bill language that would require the California Department of Education (CDE) to develop a plan to transition most contracted funding for child care programs to vouchers over the next five years. The Governor’s proposal also would redirect some quality funds currently supporting contract–based providers into the expanded voucher system.

Converting to Vouchers an Improvement Over Current System. In the current system, families receiving vouchers can choose from a variety of providers—selecting care that best fits their needs. Other similar families, however, can only access child care at specific locations with specific providers that contract directly with CDE. By converting contracted slots to voucher slots, the Governor’s proposal would allow all families to have the same level of choice in selecting child care providers.

Governor’s Proposal Does Not Address Other Design Flaws in Current System. Beyond constraining choice, the current system has several other design flaws. First, existing child care slots are not currently distributed equitably across the state, and children in different counties have differing levels of access. Secondly, voucher–based slots are not required to include developmental components, so a shift away from contract–based child care could mean that young children who are not in school would not receive developmentally appropriate care. Thirdly, the current rate structure for vouchers is unnecessarily complicated and removed from the market rates for child care.

Recommend Converting to Vouchers Over Five Years, Addressing Other Design Flaws as Part of Restructuring. We recommend the Legislature pursue the Governor’s proposal to unify the existing child care system into one voucher–based program. In doing so, we recommend the Legislature require all child care programs accepting vouchers to include developmentally appropriate activities for children birth through age three. We also recommend the Legislature take steps to equalize service levels across counties, replace the current funding model for vouchers with a simplified and market–driven model, and establish regional monitoring systems to oversee certain components of local programs.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s child care and preschool proposals. In the first section, we provide a high–level overview of these proposals. In the second section, we provide background on California’s preschool programs and assess the Governor’s preschool restructuring proposal. In the final section, we provide background on California’s child care programs and assess the Governor’s child care restructuring proposal.

Overview of Governor’s Budget Proposals

Governor Proposes $3.6 Billion for Child Care and Preschool Programs in 2016–17. Of this amount, $1.9 billion is for child care programs and $1.7 billion is for preschool programs. As shown in Figure 1, the Governor’s budget augments these programs by a total of $95 million (3 percent) from the revised 2015–16 level. Proposition 98 General Fund covers the bulk of this increase ($83 million), with a relatively small increase in non–Proposition 98 General Fund. These increases in state funds are partially offset by a small net decrease in federal funds. Under the Governor’s budget, proposed funding would support an estimated 455,000 child care and preschool slots.

Figure 1

Child Care and Preschool Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 Revised |

2015–16 Reviseda |

2016–17 Proposed |

Change From 2015–16 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

Stage 1 |

$330 |

$410 |

$394 |

–$17 |

–4% |

|

Stage 2b |

364 |

414 |

422 |

8 |

2 |

|

Stage 3 |

223 |

278 |

316 |

38 |

14 |

|

Subtotals |

($917) |

($1,103) |

($1,132) |

($29) |

(3%) |

|

Non–CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

General Child Carec |

$531 |

$450 |

$450 |

—d |

—d |

|

Alternative Payment |

182 |

251 |

255 |

$4 |

2% |

|

Migrant child care |

28 |

29 |

29 |

—d |

—d |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

2 |

2 |

2 |

—d |

—d |

|

Infant and Toddler QRIS Grant (one time) |

— |

24 |

— |

–24 |

–100 |

|

Subtotals |

($742) |

($756) |

($736) |

(–$20) |

(–3%) |

|

Preschool Programse |

|||||

|

State Preschool |

$604 |

$835 |

— |

–$835 |

–100% |

|

Transitional Kindergarten |

604f |

686f |

— |

–686 |

–100 |

|

Preschool QRIS Grant |

50 |

50 |

— |

–50 |

–100 |

|

Targeted Play and Learning Block Grant |

— |

— |

$1,654g |

1,654 |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($1,258) |

($1,571) |

($1,654) |

($83) |

(5%) |

|

Support Programs |

$73 |

$76 |

$79 |

$3 |

3% |

|

Totals |

$2,991 |

$3,506 |

$3,600 |

$95 |

3% |

|

Proposition 98 General Fund |

$1,258 |

$1,571 |

$1,654 |

$83 |

5% |

|

Non–Proposition 98 General Fund |

809 |

977 |

998 |

21 |

2 |

|

Federal CCDF |

570 |

573 |

583 |

10 |

2 |

|

Federal TANF |

353 |

385 |

365 |

–20 |

–5 |

|

aReflects Department of Social Services’ revised Stage 1 estimates for cost of care and caseload. Reflects budget act appropriation for all other programs. bDoes not include $9.2 million provided to community colleges for certain child care services. cIn 2014–15, includes funding for all State Preschool wrap slots. Beginning in 2015–16, includes funding for State Preschool wrap slots provided only by non–LEAs. dLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. eSome CalWORKs and non–CalWORKs child care providers use their funding to offer preschool. fLAO estimate based on average daily attendance in Transitional Kindergarten, as reported by CDE. gConsists of $878 million shifted from State Preschool, $726 million shifted from Transitional Kindergarten, and $50 million shifted from the Preschool QRIS Grant. QRIS = Quality Rating and Improvement System; CCDF = Child Care and Development Fund; TANF=Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; CDE = California Department of Education; and LEA = local education agency. |

|||||

Higher Spending Due to Various Adjustments. Figure 2 shows proposed 2016–17 changes. The largest change is an $80 million increase to preschool programs (discussed further below), followed by $18 million for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) child care. The budget includes a total of $14 million for annualizing rate increases to the Regional Market Rate and license–exempt rate that were initiated on October 1, 2015. The budget also makes various other adjustments, such as providing statutory growth and cost–of–living adjustments (COLA) for non–CalWORKs programs.

Figure 2

2016–17 Child Care and Preschool Changes

(In Millions)

|

Change |

Proposition 98 General Fund |

Non–Proposition 98 General Fund |

Federal Funds |

Total |

|

Preschool Programs |

||||

|

Creates new early education block grant |

$1,654 |

— |

— |

$1,654 |

|

Moves part–day State Preschool and full–day wrap run by LEAs into proposed early education block grant |

–878 |

— |

— |

–878 |

|

Moves Transitional Kindergarten into proposed early education block grant |

–726 |

— |

— |

–726 |

|

Moves Preschool QRIS Grant into early education block grant |

–50 |

— |

— |

–50 |

|

Adjusts Transitional Kindergarten for increases in LCFF before moving into block grant |

40 |

— |

— |

40 |

|

Adjusts State Preschool for annualization of slots initiated in 2015–16 and statutory growth and COLA before moving into block granta |

36 |

$3b |

40 |

|

|

Subtotals |

($76) |

($3) |

(—) |

($80) |

|

Child Care Programs |

||||

|

Makes CalWORKs caseload and average cost of care adjustments |

— |

$38 |

–$20 |

$18 |

|

Annualizes funding for Regional Market Rate ceiling increase initiated in 2015–16 |

— |

10 |

–1 |

9 |

|

Adjusts non–CalWORKs child care programs for statutory growth and COLAa |

— |

4 |

— |

4 |

|

Annualizes funding for 5 percent license–exempt rate increase initiated in 2015–16 |

— |

4 |

1 |

5 |

|

Removes one–time Infant and Toddler QRIS Grant funds |

— |

–24 |

— |

–24 |

|

Subtotals |

(—) |

($32) |

(–$19) |

($12) |

|

Other Technical Adjustments |

$7 |

–$14 |

$10 |

$3 |

|

Totals |

$83 |

$21 |

–$9 |

$95 |

|

aReflects 0.13 percent growth in the birth–through–four population and 0.47 percent COLA. bAnnualizes the cost of the 1,200 non–LEA, full–day State Preschool wrap slots initiated January 1, 2015. COLA = cost–of–living adjustment; LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; LEA = local education agency; and QRIS = Quality Rating and Improvement System. |

||||

Governor Proposes Major Restructuring of California’s Child Care and Preschool Programs. Specifically, the Governor proposes to consolidate funding streams for various existing preschool programs into a new block grant to serve low–income and at–risk children. The Governor also proposes tasking the California Department of Education (CDE) with creating a five–year plan to transition all child care subsidies to vouchers.

Governor’s Budget Adjusts Transitional Kindergarten and State Preschool Amounts Before Shifting Into New Block Grant. The fund shift from Transitional Kindergarten and State Preschool into the new block grant reflects the Proposition 98 funds that those programs would have otherwise received in 2016–17. The Transitional Kindergarten fund shift includes a $40 million augmentation, which reflects higher projected funding rates under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The State Preschool fund shift includes a $36 million Proposition 98 augmentation, which reflects annualizing the cost of certain slots, 0.13 percent statutory growth, and a 0.47 percent COLA. (Rather than shifting into the block grant, the Governor proposes leaving $3 million in related non–Proposition 98 growth in the General Child Care program.)

Governor’s Budget Does Not Move All Full–Day State Preschool Wrap Into New Block Grant. Currently, State Preschool wrap is provided by local education agencies (LEAs) and non–LEAs. The Governor does not move $143 million supporting the wrap provided by non–LEAs into the proposed block grant. This wrap component is currently funded out of General Child Care (non–Proposition 98). As a result of not moving these existing preschool wrap funds into the block grant, General Child Care slots increase by about 13,000 in 2016–17 under the Governor’s display.

Back to the TopPreschool Restructuring

In this section, we provide background on California’s major preschool programs; describe the Governor’s proposal for preschool restructuring; provide an assessment of the Governor’s proposal; and offer a framework for developing a single, coherent preschool program.

Background

California Has Several Major Preschool Programs. Figure 3 highlights key features of California’s four largest preschool programs: center–based voucher programs, the California State Preschool Program (CSPP), Transitional Kindergarten (TK), and federal Head Start. As shown in the figure, the programs are similar in some ways and different in other ways. For example, three of the four programs determine eligibility based on family income whereas one determines eligibility by a child’s birthday. Two of the programs require low–income families to be working to receive full–day preschool whereas the other two programs do not have a work requirement. The programs operate out of school districts, subsidized preschool centers, or both places. The state funds each of the three state programs using a different funding method (family vouchers, direct state contracts, and school district LCFF payments). Though not shown in the figure, in 2014–15 the state also began providing $50 million annually for Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS) designed to promote improvement among some CSPP providers in some areas of the state. In addition to the programs already mentioned, some preschool in California is funded with federal Title I funds, local First 5 funds, and special education funding. Some children may benefit from multiple preschool programs. For example, some children are enrolled in both CSPP and Head Start.

Figure 3

Major Preschool Programs in California

|

Center–Based Voucher Programsa |

California State Preschoolb |

Transitional Kindergartenc |

Head Startd |

|

|

Eligibility |

||||

|

Family income eligibility cap |

70 percent of 2007 state median income |

70 percent of 2007 state median income |

None |

100 percent of federal poverty level |

|

Annual income cap for family of three |

$42,216 |

$42,216 |

N/A |

$20,090 |

|

Work requirement |

Yes |

Yes for full–day program |

No |

No |

|

Age eligibility criteria |

Two– through five–year olds |

Three– and four–year olds |

Four–year olds with birthdays between September 2 and December 2 |

Three– and four–year olds |

|

Four–year olds servede |

5,400 |

138,400 |

83,000 |

46,400 |

|

Program |

||||

|

Provider(s) |

Subsidized centers |

LEAs and subsidized centers |

LEAs |

LEAs and subsidized centers |

|

Duration |

Varies based on parents’ work schedules |

At least 6.5 hours per day, 250 days per year for full–day program; at least 3 hours per day, 175 days per year for part–day program |

Must operate no fewer than 180 days per year, hours per day determined by district |

Determined by local provider |

|

Funding |

||||

|

Method of payment |

State provides funds to providers on behalf of families |

State directly contracts with providers |

State provides funds through LCFF |

5–year federal grant directly to providers |

|

Total funding for four–year oldse |

$60 million |

$740 million |

$690 million |

$420 million |

|

Annual funding per childe |

Average of $10,600 for full–time program |

$4,200 (part–day) and $9,600 (full–day) |

Average of $8,500 |

Average of $9,100 |

|

a Includes the CalWORKs child care and Alternative Payment programs. Programs are offered to children birth through 12 years of age, with certain funding rates and program requirements for children two through five–years old. Number of four–year olds served is estimate of four–year olds receiving care in a center. Overall, 19,100 four–year olds received vouchers for care in a variety of settings. Full–time rate assumes reimbursement on a monthly basis. bUp to 15 percent of children in program may come from families with incomes above cap. Program gives priority to serving four–year olds. cDistricts may choose to serve other four–year olds, but those children do not generate state funding until they turn five. dUp to 10 percent of children in program may come from families with incomes above cap. Some programs also provide home visits and wraparound services such as health check–ups. Number of four–year olds served is based on 2014–15 enrollment. eNumber of four year–olds served, total funding, and per–child funding are 2015–16 estimates. LEA = local education agency and LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

||||

For Some Programs, Available Slots Insufficient to Serve All Eligible Children. Some voucher programs, CSPP, and Head Start are unable to serve all eligible children. The number of available slots for these programs is determined by annual budget appropriations and priority is given to certain children. Voucher programs and CSPP must give priority to children receiving child protective services, children at risk of being abused or neglected, and children from families with the lowest incomes. Head Start providers are required to develop their own priority ranking based on the needs of the local community, but they too generally limit eligibility to children from low–income families. For TK, all four–year olds with September 2 to December 2 birthdays, regardless of family income, are guaranteed slots. School districts receive TK funding for these children automatically as part of their LCFF allotments.

Some Children From Low–Income Families Not Currently Served. Based on participation data from the four programs, we estimate between 60 percent and 80 percent of four–year olds from families that earn below 185 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are served by subsidized preschool centers and school districts. This range is large because we do not have data on the number of children enrolled in multiple programs. (The 185 percent threshold is used as an eligibility criterion for various K–12 education programs, including a major child nutrition program. In 2015–16, the 185 percent threshold equated to about $37,000 a year for a family of three.) Eligible children may not be participating for a variety of reasons. Some families may not be aware of subsidized programs, may choose not to enroll their children, or may be unable to find slots in nearby programs.

Many Children With Disabilities Not Currently Served in Mainstream Programs. Federal law requires that LEAs provide appropriate services, in many cases including preschool, to children with disabilities. Federal law also requires that students with disabilities be served in the least restrictive environment. For most three and four–year olds with disabilities, this means a program where they are served along with their mainstream peers, such as in CSPP. Because federal law does not require school districts to create a mainstream preschool program if they do not already have one, some children with special needs may not have a mainstreaming option available. In 2013–14, 41 percent of three and four–year olds with special needs were served in mainstream programs, 34 percent were served in specialized programs, and 25 percent did not receive any form of early education.

Programs Have Different Standards and Oversight. Figure 4 describes the standards that apply to the four preschool programs. Each program has a unique set of requirements related to teacher qualifications, staffing ratios, health and safety standards, developmental standards, and oversight. As shown in the figure, all programs are required to meet some minimum health and safety standards, although specific standards vary by program. Three of the programs must include developmental standards, but these specific standards also vary somewhat across the programs. Center–based voucher programs are not required to include developmental standards, but some may provide services similar to CSPP.

Figure 4

Standards for Major Preschool Programs

|

Center–Based Voucher Programs |

California State Preschool |

Transitional Kindergarten |

Head Start |

|

|

Teacher Qualifications |

Child Development Associate Credential (12 units in ECE/CD).a |

Child Development Teacher Permit (24 units of ECE/CD plus 16 general education units).b |

Bachelor’s degree and multiple subject Teaching Credential and a Child Development Teacher Permit or at least 24 units of ECE/CD or comparable experience.c |

Half of teachers must have a bachelor’s degree in ECE/CD or a bachelor’s degree with ECE/CD experience. Rest of teachers must have associate’s degree in ECE/CD (typically between 24 and 40 credits) or associate degree with ECE experience. |

|

Staffing Ratios |

1:12 teacher–child ratio or 1 teacher and 1 aide per 15–18 children. |

1:24 teacher–child ratio and 1:8 adult–child ratio. |

1:33 maximum teacher–child ratio. |

1:20 teacher–child ratio and 1:10 adult to child ratio. |

|

Health and Safety Standards |

Staff and volunteers are fingerprinted. Subject to health and safety standards. |

Staff and volunteers are fingerprinted. Subject to health and safety standards. |

Staff are fingerprinted. Subject to K–12 education health and safety standards. |

Staff and volunteers are fingerprinted. Subject to health and safety standards. |

|

Developmental Standards |

None. |

Developmentally appropriate activities designed to facilitate transition to kindergarten. |

Locally developed, modified kindergarten curriculum. |

The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework. |

|

Oversight |

Unannounced visits by CCL every three years or more frequently under special circumstances. |

Unannounced visits by CCL every three years or more frequently under special circumstances. Onsite reviews by CDE every three years (or as resources allow) and annual self–assessments. |

Teacher–child ratios subject to annual audit. Some school facilities inspected by county offices of education. |

Unannounced visits by CCL every three years or more frequently under special circumstances. Onsite reviews by the Federal Office of Head Start every three years. |

|

aThe Child Development Associate Credential is issued by the National Credentialing Program of the Council for Professional Recognition. bThe Child Development Teacher Permit is issued by California’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing. cEffective for new TK teachers hired after July 1, 2015. CCL= Community Care Licensing; CDE = California Department of Education; and ECE/CD = Early Childhood Education/Child Development. |

||||

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Proposes Consolidating Three Existing Funding Streams Into New Block Grant. The Governor proposes to consolidate three existing preschool programs into a new $1.6 billion Early Education Block Grant. Specifically, the proposal would redirect funding from CSPP ($845 million), TK ($726 million), and the QRIS Block Grant for CSPP ($50 million). Funds from the new block grant would be given to LEAs and potentially other entities that currently offer CSPP to operate a developmentally appropriate preschool program. The providers also would be required to conduct some support activities, including family engagement, screening for developmental disabilities, and referral to supportive health and social services, if appropriate. The Governor’s proposal does not shift $33 million in CSPP funds that support preschool programs at 55 community colleges. (These programs serve the dual purpose of providing preschool for children of community college students and serving as a lab school for students training to become preschool teachers.)

Low–Income and At–Risk Children to Receive Priority. The Governor’s proposal requires block grant recipients to prioritize services to children from low–income families (as defined locally), homeless children, foster children, children with disabilities, children at–risk of abuse and neglect, and English learners. Although the proposal specifies which students should receive priority, the proposal does not require providers to serve any specific group of students.

Hold Harmless Provision for LEAs. The Governor’s proposal includes a hold harmless provision that ensures LEAs receive the same amount from the new block grant as they otherwise would have received from TK and CSPP contracts. The state would distribute any remaining block grant funds based on local need. (At the time of this writing, the administration’s proposed trailer legislation had no specific definition of “local need.”)

Administration Plans to Submit Additional Details of New Program as Part of May Revision. The Governor’s January proposal contains few details about the restructured preschool program. The proposal, for example, does not set forth specific eligibility criteria, the role of private providers, program standards, or clear funding rules. The administration intends to solicit feedback from stakeholders on these issues and release a more detailed proposal in May.

Assessment

Consolidating Funding and Prioritizing Based on Need Are Improvements Over Current Approach. The Governor’s proposal to consolidate three preschool funding streams into one program would help simplify and streamline the state’s existing labyrinth of preschool programs while improving transparency and coherence. Prioritizing funds for low–income children would ensure that the state’s available resources are directed to those most likely to benefit. Low–income families are both less likely than higher–income families to be able to afford preschool and more likely to benefit from access to preschool (according to most research). Prioritizing at–risk students would provide children who have had adverse early childhood experiences access to supportive environments. Finally, prioritizing children with disabilities as part of a larger mainstream program creates more opportunities for them to be served alongside their peers.

Allowing Income Eligibility to Be Locally Determined Likely to Result in Similar Children Receiving Different Levels of Service. We are concerned about the Governor’s proposal to let income eligibility criteria be locally determined. Allowing this core eligibility criterion to be set locally very likely would result in notable differences across the state in services and funding per child. This could result in similar children being treated very differently based on where they live. Neighboring school districts with similar levels of funding, for example, could target their program to a different set of students and provide significantly different levels of service.

Hold Harmless Provision Limits Ability to Allocate Funding Based on Need. We also are concerned about the Governor’s proposal to lock in districts’ funding allocations permanently. Because TK eligibility is based on birth month and not tied to need, school districts with relatively low and relatively high shares of low–income students currently may be operating TK programs that are similar in size. Thus, the Governor’s proposed hold harmless provision would result in some districts permanently receiving a disproportionate amount of funding relative to their numbers of low–income and at–risk children. These districts would be able to expand eligibility to serve a much larger share of their children or provide a much more expensive program for low–income or at–risk children in their areas. By contrast, some school districts with relatively high proportions of low–income and at–risk children would receive proportionately fewer resources. As a result, these districts would have to narrow eligibility or operate with notably less funding per child.

Recommendations

Key Features of Any Restructured Preschool Program. As discussed below, we believe certain features are important to include as part of any restructured preschool program.

One Consolidated Funding Stream. We recommend the Legislature consolidate all existing Proposition 98 funding for preschool into one new program. Under this approach, the state would consolidate nearly $1.7 billion in funding from CSPP, TK, and QRIS, as well as the set–aside for community college lab schools, into one program.

Specific Eligibility Criteria. To ensure similar children are treated similarly across the state, we recommend the Legislature set specific criteria for which students are eligible for the new preschool program. We think a reasonable approach would be to provide preschool to all four–year olds from families with incomes below 185 percent of FPL, and all four–year olds who are receiving child protective services, are at–risk of being abused or neglected, are homeless, or have disabilities. Providers under such an approach might choose to offer preschool to children above 185 percent of FPL, but they would need to do so using other resources.

Funding Linked to Children. To ensure that additional funding directly results in additional children being served, we recommend the Legislature allocate funding to providers based on the number of eligible children who participate in the program. This approach is similar to the current funding approach for CSPP and TK. (As discussed in the nearby box, setting a per–child funding rate is likely to be among the Legislature’s most difficult program decisions.) If the Legislature were to adopt a hold harmless provision for current providers, we recommend the provision only take effect during the transition to the new system, as this would better ensure funding upon full implementation is linked to children.

Illustration of One Possible Funding Rate for New Preschool Program

One of the most difficult decisions the Legislature likely would face as part of restructuring is setting the specific per–child funding rate. Ideally, the funding rate would be based on the cost of the service being sought. For illustrative purposes, if the Legislature required new preschool programs to operate 180 days per year (the same as the school year), it might offer a part–day rate of $5,200 and a full–day rate of $7,800 (part–day rate plus a $2,600 wraparound rate). This part–day rate is 20 percent higher than the current California State Preschool Program (CSPP) part–day rate. This wraparound rate is the same as the current CSPP wrap rate, adjusted for 180 days. These rates are roughly comparable to the current market–based, full–time, monthly voucher preschool rates, adjusted for 180 days. At these rates, we estimate the state could serve all children who meet our recommended eligibility criteria within existing resources.

Convenience for Families. The Legislature could take a couple of steps to make participation easier for families. We recommend the state require providers to offer full–day preschool programs for children from low–income, working families. Without a full–day option, some families would otherwise be unable work or opt to place their children in less formal environments that have no specific learning expectations. We also recommend the Legislature create a streamlined eligibility verification process that reviews eligibility only once per year (at the beginning of the school year). Under such an approach, a child would remain eligible for the entire school year, regardless of changes in family circumstances.

Developmentally Appropriate Activities. We also recommend providers be required to include developmentally appropriate activities in their preschool programs. This could include using California’s Preschool Learning Foundations or an alternative framework, such as the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework, that includes age–appropriate activities. Foundations such as these typically focus on helping children learn self–awareness and self–regulation, how to interact with peers and teachers, language and basic literacy, and basic numeracy. Because these types of frameworks are not overly prescriptive, providers still would retain a great deal of flexibility to develop a specific curriculum tailored to the needs and interests of their children.

Minimum Staffing Requirements. We recommend the Legislature set some minimum standards to ensure a baseline of services for all eligible children. At a minimum, we recommend the state require teachers to have some education in child development (for example, a Child Development Permit, as is required in CSPP) and set a maximum teacher–child ratio.

Basic Reporting Requirements. We recommend the Legislature also require basic information from providers. We recommend requiring providers to collect basic student demographic information, such as race, gender, family income, and disability status. This data would allow educators and policymakers to monitor program participation. The Legislature also could require CDE to report preschool participation rates by county. This would help the state identify geographical areas that consistently enroll relatively few eligible children, thereby allowing the state to make targeted efforts to increase preschool enrollment in those areas. To foster transparency, we also recommend the state require providers to create plans that would be available online. Such plans could include information on key elements of a program, such as the length of the program (hours per day and days per year), curriculum, process for measuring the program’s added value to the child, and family engagement activities.

Other Key Restructuring Decisions

Various Trade–Offs to Consider When Designing Remaining Features of Program. In addition to the above issues, the Legislature faces other important restructuring decisions. These decisions entail selecting providers, developing a method for disbursing funding, and figuring out how best to oversee the new program. Below, we discuss some trade–offs the Legislature faces in making each of these decisions.

Providers. One key decision the Legislature would face in restructuring preschool is identifying which entities should be responsible for providing the program. On the one hand, school districts and charter schools offer greater opportunity to ensure preschool is aligned with kindergarten and the rest of the K–12 school system. Additionally, because school districts already have specific district boundaries and are required to serve all school–aged children within those boundaries, they are well–positioned to ensure that all eligible children living within their catchment area have access to a new preschool program. (Smaller school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education also are familiar with forming joint powers agencies to help them coordinate program services within their vicinities.) Currently, no similar catchment system exists for non–LEA providers. On the other hand, many non–LEA providers have a long history and considerable expertise serving preschool–aged children. In many cases, these providers also provide wraparound services, such as infant or toddler child care and after school care. Furthermore, non–LEA providers may provide certain types of preschool options that have greater appeal to some families and may be more conveniently located for some families than their LEA options.

A Method for Disbursing Funds. Another important decision the Legislature would face in restructuring preschool is deciding how to disburse funds to providers. Disbursing funds to LEAs through the LCFF system is straightforward and requires no special administrative structure. Were both LEAs and non–LEAs to provide preschool programs, however, the state likely would need another funding disbursement mechanism. For example, it might continue issuing direct contracts with providers. Though direct contracts are somewhat more administratively burdensome than LCFF allocations, they still can keep funding linked with children served and track slots allotted to each provider.

Oversight and Accountability. Finally, if it pursues preschool restructuring, the Legislature will need to decide how to oversee program providers. On the one hand, having a robust state oversight system could result in greater consistency among programs statewide. On the other hand, a local oversight system could take into account local priorities and challenges while also providing more tailored feedback to local providers on improving their programs.

Some Program Components Fit Together Better Than Others. Some combinations of decisions seem to fit together better than other combinations. In particular, certain combinations of eligibility, provider, funding, and oversight decisions seem to go together. For example, if the Legislature were to decide to serve all low–income children, then relying on school districts becomes a relatively natural fit, as districts could be required to serve all children showing up for the program. If LEAs were selected as providers, then disbursing funds through LCFF and using local governing boards as oversight agents become more natural downstream decisions. Alternatively, were the Legislature to decide to select both LEAs and non–LEAs as providers, then disbursing funds through direct state contracts and using state agencies to perform some oversight activities become more natural downstream decisions.

Transition

Multiyear Phase In. Any effort to restructure California’s preschool programs into a single, coherent program will involve many decisions and take some time. By gradually introducing new eligibility, program, funding, and administrative requirements over a number of years, the state could minimize disruption to children, families, and providers while ensuring steady progress towards a better system. Given families typically make enrollment decisions and providers typically make staffing and budget decisions several months in advance, we recommend the Legislature allow plenty of time to notify them of any program changes.

Transition Plan. As part of restructuring, we recommend the Legislature create a transition plan that sets forth when certain changes would take place. For example, in the first year of a transition plan, the state could continue CSPP and TK under existing rules. In the second year, the state could replace CSPP and TK rules with new eligibility rules and begin changing funding allocations to match children served. In the third year, the state could fully transition to the new funding formula and begin to ramp up program oversight.

Back to the TopChild Care Restructuring

In this section, we provide background on California’s major child care programs, describe the Governor’s proposal for child care restructuring, assess the current system, and set forth a package of recommendations for improving the system.

Background

California Has Several Child Care Programs Designed to Serve Low–Income, Working Families. Figure 5 highlights key features of California’s four main subsidized child care programs: CalWORKs child care, the Alternative Payment (AP) Program, General Child Care, and Migrant Child Care. All four of these programs generally are designed to serve low–income, working families during the hours that parents work or are participating in an education or training program. In addition to these programs, California funds the Care for Children with Severe Disabilities program, which provides child care to about 150 children birth to 21 in the San Francisco Bay Area. (The nearby box provides additional detail on the stages of CalWORKs child care.)

Figure 5

Major Child Care Programs in California

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

Alternative Payment Program |

General Child Care |

Migrant Child Care |

|

|

Family income eligibility |

70 percent of 2007 state median income ($42,216 per year for a family of three) |

70 percent of 2007 state median income ($42,216 per year for a family of three) |

70 percent of 2007 state median income ($42,216 per year for a family of three) |

70 percent of 2007 state median income ($42,216 per year for a family of three), half of gross income must be from agricultural work |

|

Age eligiblity |

Birth through age 12 |

Birth through age 12 |

Birth through age 12 |

Birth through age 12 |

|

Access |

Guaranteed for current and former CalWORKs families until no longer income– or age–eligible for programa |

Subject to available slots |

Subject to available slots |

Subject to available slots |

|

Priority (if access limited) |

— |

1. Children receiving child protective services or at–risk of abuse and neglect 2. Children from families with the lowest incomesb |

1. Children receiving child protective services or at–risk of abuse and neglect 2. Children from families with the lowest incomesb |

1. Family moves from place to place 2. Family meets 1st criteria within past five years 3. Family lives in rural area and is dependent upon seasonal agricultural work |

|

Number of children servedc |

130,970 |

32,852 |

28,738 |

3,060 |

|

Settings |

Licensed center, FCCH, license–exempt |

Licensed center, FCCH, license–exempt |

Licensed center, FCCH |

Licensed center, FCCH, license–exempt |

|

Administrative mechanism |

Vouchers |

Vouchers |

Contracts |

Mix of vouchers and contracts |

|

Total funding (in millions)c |

$1,103 |

$251 |

$450d |

$29 |

|

aCalWORKs Stage 1 and 2 Child Care are statutory entitlements. The Legislature traditionally has funded Stage 3 Child Care as an entitlement. bWithin income bracket, these programs prioritize children with exceptional needs. cNumber of children served and total funding are 2015–16 estimates. dIncludes $145 million for full–day State Preschool wrap provided by non–local education agencies. FCCH = family child care homes. |

||||

CalWORKs Child Care Consists of Three “Stages”

Families participating in welfare–to–work activities through California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) are statutorily guaranteed child care subsidies during “Stage 1” and “Stage 2” of the program. Families are considered to be in Stage 1 when they first enter CalWORKs and connect to services at county welfare departments. Once CalWORKs families become stable (as defined by the county), they move into Stage 2. Families move into “Stage 3” two years after they stop receiving cash aid. Families in CalWORKs Stage 3 are not statutorily guaranteed child care subsidies, but the Legislature has in practice funded all eligible families. Families remain in Stage 3 until their income exceeds 70 percent of state median income or their child ages out of the program.

State Subsidizes Through Vouchers and Direct Contracts. The state provides subsidized child care in two ways. Families participating in the CalWORKs and AP programs receive vouchers that they may use to access care with different types of child care providers. The state subsidizes other families via direct contracts with certain licensed child care providers. Migrant Child Care provides services to children of migrant parents through both vouchers and direct contacts with licensed providers.

Voucher– and Contract–Based Care Provided in a Variety of Settings. Families receiving child care vouchers can choose from three types of child care settings: licensed centers, licensed family child care homes (FCCHs) and license–exempt care. Families in contract–based programs may access licensed centers and FCCHs. For both the voucher– and contract–based programs, centers typically are run by community–based organizations or LEAs and often serve more children than other types of providers. The FCCHs operate from providers’ homes, with each home typically serving 6 to 12 children. License–exempt care is provided by an individual of the family’s choosing—typically a relative, friend, or neighbor who provides care in a private home.

Some Standards Vary Across Voucher– and Contract–Based Programs. As shown in Figure 6, the state sets standards for each type of child care provider. All licensed providers must meet Community Care Licensing (CCL) health and safety standards. Licensed voucher–based providers also must meet certain CCL staff qualifications and staffing ratios. Collectively, these health, safety, and staff standards are commonly referred to Title 22 standards. Contract–based providers must meet Title 22 health and safety standards but have somewhat different staffing ratios. Contract–based providers also require teachers to have more training than teachers in voucher–based programs.

Figure 6

Standards for Child Care Providers

Infant Children, Aged Birth Through 24 Monthsa

|

Providers Accepting Vouchers |

Direct Contracts |

||||

|

License–Exempt |

FCCHs |

Centers |

Centersb |

||

|

Staff qualifications |

None. |

15 hours of health and safety training. |

Child Development Associate Credential or 12 units in ECE/CD.c |

|

Child Development Teacher Permit (24 units of ECE/CD plus 16 general education units).d |

|

Staffing ratios |

May not serve children from multiple families at any given time. |

1:6 adult–child ratio.e |

1:12 teacher–child ratio and 1:4 adult–child ratio. |

1:18 teacher–child ratio and 1:3 adult–child ratio. |

|

|

Health and safety standards |

Criminal background check. Self–certification of certain health and safety standards. |

Staff and volunteers are finger printed. Subject to health and safety standards. |

Same as voucher–based FCCHs. |

Same as voucher–based FCCHs. |

|

|

Developmental standards |

None. |

None. |

None. |

Requires developmentally appropriate activities. |

|

|

Oversight |

None. |

Unannounced visits by CCL every three years or more frequently under special circumstances. |

Same as voucher–based FCCHs. |

Same as voucher–based FCCHs, but also onsite reviews by CDE every three years (or as resources allow) and annual self–assessments. |

|

|

Applicable programs |

CalWORKs, AP Program, Migrant Vouchers |

CalWORKs, AP Program, Migrant Vouchers |

CalWORKs, AP Program, Migrant Vouchers |

General Child Care, Migrant Centers, Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

|

|

aStandards for children of other ages similar to those displayed here. Infants in Title 5 Centers are aged birth through 18 months. bSame standards generally apply to FCCHs serving children in General Child Care program. cThe Child Development Associate Credential is issued by the National Credentialing Program of the Council for Professional Recognition. dThe Child Development Teacher Permit is issued by California’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing. eNo more than four infants may be served by any one adult. AP = Alternative Payment; CCL = Community Care Licensing; CDE = California Department of Education; ECE/CD = Early Childhood Education/Child Development; and FCCHs = family child care homes. |

|||||

Contract–Based Programs Required to Include Developmental Component to Care. This requirement is a key difference from voucher–based programs, which have no explicit requirement to provide developmentally appropriate activities. Often the developmental component of contract–based programs is referred to as the “learning foundations” after the frameworks developed by CDE for the programs. The learning foundations describe the skills that children of different ages should be able to exhibit. Programs required to use the foundations focus their activities around supporting the development of these skills. Together, the health, safety, staffing, and developmental requirements that apply to contract–based child care providers are commonly referred to as Title 5 standards.

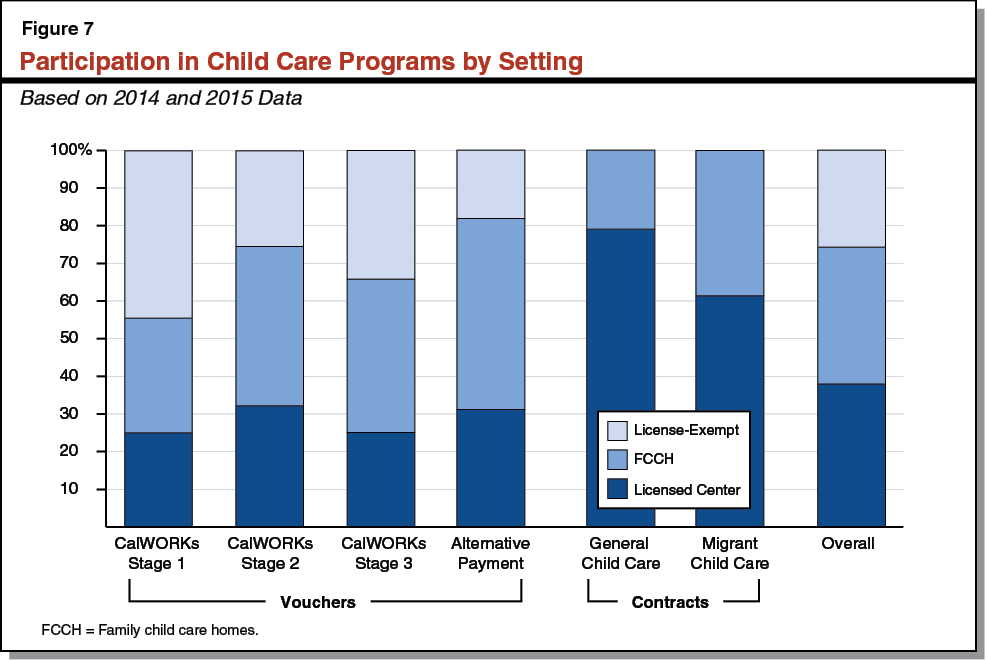

Reliance on Particular Child Care Settings Differs Between Contracts and Vouchers. Three–fourths of subsidized children are served in licensed settings. Based on the most recently available data, 38 percent of children are served in centers and 36 percent are served in FCCHs (see Figure 7). About one–third of children receiving vouchers rely on license–exempt care. License–exempt care is most common among CalWORKs families. More than one–third of CalWORKs children receive license–exempt care, whereas about one–fifth of non–CalWORKs AP children receive this type of care. (The General Child Care and Care for Children with Severe Disabilities programs do not allow for license–exempt care.)

Reimbursement Rate Structures Vary for Contracts and Vouchers. Providers running General Child Care, contract–based Migrant Child Care, and Care for Children with Severe Disabilities programs generally are paid a Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR). The SRR is higher for centers than FCCHs. The SRR is adjusted to account for various characteristics of the child served—including age, limited English proficiency, or having a disability. In contrast, reimbursements for voucher providers and certain General Child Care FCCHs vary based on the county in which the child is served. These reimbursement rates are referred to as Regional Market Rates (RMRs) and are based on regional market surveys of private providers, conducted every two years as required by federal regulations. Like the SRR, the RMR is adjusted based on the age of the child and if the child has a disability. Unlike the SRR, the RMR sets rate “ceilings” for the maximum amount the state is willing to pay for a certain type of care. If a provider charges less than the ceiling, the state reimburses the actual child care charge. (The state currently reimburses license–exempt providers at 65 percent of each county’s maximum RMR for FCCHs.)

Rates Based on Historical Decisions. The SRR generally is based on rates dating back to the 1940s. Over the years, the state has updated the SRR to reflect increasing program costs. These adjustments, however, have not occurred every year. For the RMR, the state historically set the ceilings at the 85th percentile of the most recent market survey. (The percentile at which the state sets the RMR effectively reflects the purchasing power and amount of choice associated with a voucher. At the 50th percentile, for example, a voucher would allow a low–income family to select among the less–expensive half of all providers.) Over the past few years, the state has adjusted the RMR in various ways to reflect the increasing cost of child care. Today, the state sets the RMR at the greater of 104.5 percent of (1) the 85th percentile of the 2005 regional market survey or (2) the 85th percentile of the 2009 regional market survey, deficited by 10.11 percent.

Recent Rate Changes Have Resulted in Greater Differences Across Counties. Most notably, the deficit factor applied to the 2009 survey has resulted in inequities in access across the state. In counties where most child care providers charge at or about the same rates, a 10 percent cut in the value of the vouchers means that families do not have access to as much of the market as families living in counties with wide variation in provider rates.

State Has Higher Reimbursement Rate for Lower Standard of Care. While the RMR is below the SRR in some counties, most RMR rates are higher on average than the SRR rate, as shown in Figure 8. Since most providers that accept the RMR are not required to include developmental components in their care, this means that in many cases the state pays more for a lower standard of care.

Figure 8

Comparing Reimbursement Rates for Vouchers and Contracted Slotsa

Average Annual Reimbursement Rate for Center–Based Programs

|

Infant (Birth to 24 months) |

Preschool–Aged (Ages 2–5) |

School–Age (Ages 6–12) |

||||||

|

RMR |

SRRb |

RMR |

SRRc |

RMR |

SRR |

|||

|

Full–time care |

$18,372 |

$16,273 |

$12,730 |

$9,633 |

$9,116 |

$9,573 |

||

|

Part–time cared |

11,695 |

12,205 |

9,315 |

7,224 |

5,850 |

7,179 |

||

|

aRMR average costs are weighted by the number of subsidized children receiving child care in centers in each county. Estimates assume 250 days of operation, with half of children reimbursed at weekly rate and half at monthly rate. bRepresents the SRR infant rate. The SRR defines infants as birth through 18 months and toddlers as 18 months through 36 months. The toddler rate is $13,403 for full–time care. cRepresents the SRR preschool rate. The SRR defines preschool–aged children as children age 3 up to kindergarten. Because the part–time care rate shown is based on 250 days of operation, it is higher than the part–day rate for State Preschool ($4,177), which is based on 175 days. dReflects rate for between 4 and 6.5 hours of care per day. RMR = Regional Market Rate and SRR = Standard Reimbursement Rate. |

||||||||

To Help Administer Voucher Programs, State Contracts With AP Agencies. For CalWORKs Stages 2 and 3 and the AP program, the state contracts with AP agencies that determine eligibility for care and process payments to providers. (For CalWORKs Stage 1, the state funds county welfare departments that either issue payments to providers directly or subcontract this work out to AP agencies.) For Migrant vouchers, the state contracts with Migrant AP agencies to undertake similar functions.

State Continues to Make Efforts to Improve Quality of Care. The state makes efforts every year to improve the quality of voucher– and contract–based child care. On a longstanding basis, the federal government has required the state to spend a certain amount annually to improve the quality of care. In 2015–16, the state allocated about $70 million for this purpose. More recently, the state has worked with local consortia to establish local Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS) in some areas of the state, using a mix of federal, state, and local resources. These QRIS typically evaluate and monitor programs based on various metrics, including teacher qualifications, curriculum, and environment. Associated funding covers these evaluation and monitoring costs as well as supports staff development for providers. While federal and state spending (approximately $200 million since 2012) for these QRIS is set to sunset in 2015–16, First 5 California—a commission established to use tobacco tax revenues to benefit children birth through five—has recently announced that it plans to spend $190 million between 2015–16 and 2019–20 to expand and enhance QRIS.

Counties Serve Very Different Proportions of Low–Income Children. We estimate that counties in the Central Valley serve the lowest proportions of low–income children. The highest share of children served is in San Francisco County. Despite this variation among counties, almost all counties in California serve a relatively small proportion of low–income children, with most counties serving less than 20 percent. These estimates are based on our comparison of the number of low–income children by county with the total number of subsidized child care slots by county (excluding CSPP). (Because data on the share of low–income children with working parents is not available, we cannot know how many children actually are eligible for subsidized child care. Additionally, the state does not currently track the demand for child care among eligible families. Between 2005 and 2010, the state funded all counties to maintain centralized eligibility lists [CELs] that consolidated the waiting lists for all non–CalWORKs programs and allowed the state to track the demand for child care among eligible families.)

Governor’s Proposal

Initiates Five–Year Plan for Transitioning All Subsidized Child Care to Voucher System. The Governor has proposed trailer bill language that would require CDE to develop a plan to transition contracted funding (General Child Care and Migrant Child Care) to vouchers over the next five years. Under the plan, all contracted funding except for funds supporting the Care for Children With Severe Disabilities program would be converted to vouchers. The Governor’s proposal also would require CDE to make recommendations for redirecting quality funds from activities now benefiting only contract–based providers to activities that would benefit the expanded voucher system.

Assessment

Converting to Vouchers Would Offer Families More Flexibility in Selecting Providers. The Governor’s proposal to convert contracted slots to vouchers would give some families greater choice than they now have in selecting the child care providers that best meet their needs. Moreover, in an all–voucher system, every family would have the same level of choice in selecting providers that meets their needs. We believe this would be a significant improvement over the current system, as similar families currently receive different levels of choice.

Converting to Vouchers Could Result in Some Children Not Receiving Developmentally Appropriate Care. In 2015–16, about 35,000 birth through three–year olds received contract–based child care (including three–year olds in CSPP), thereby receiving care with a developmental component. Since child care providers that accept vouchers are not required to include development components, converting these 35,000 slots into vouchers could result in a corresponding loss of developmentally appropriate care. (Children older than three years of age could receive developmentally appropriate learning opportunities through preschool and school.)

Converting to Vouchers Likely Would Entail Additional Cost. Given the RMR ceilings are higher than the SRR in most cases, transitioning all slots to vouchers likely would entail some cost. Assuming all families previously receiving care in centers continued to choose center care when given the voucher option, converting SRR slots into vouchers would cost roughly $70 million. If families instead made similar decisions to families currently in the AP program and relied more heavily on FCCHs and license–exempt care, converting SRR slots into vouchers would cost roughly $25 million.

Converting to Vouchers Over Five–Year Period Minimizes Disruption, Allows for Better Planning and Implementation. A change to vouchers could cause substantial disruption to providers and families if not done gradually over time. At a minimum, the state would need to phase out contracts, adjust reimbursement rates, and determine what standards would apply to subsidized providers.

Recommendations

Below, we set forth a package of recommendations for building a more coherent child care system.

Create One Voucher–Based System. We recommend the Legislature pursue the Governor’s proposal to unify the existing child care system into one voucher–based program. Toward this end, we recommend converting General Child Care and all Migrant Child Care slots into vouchers. Converting to all vouchers would result in a simpler, more rational, and more transparent system that would be easier for families to use and easier for the state to administer. Under an all–voucher system, families now using contract–based care would be given greater choice in selecting convenient care providers. The change to an all–voucher system would affect roughly 300 subsidized providers that currently contract directly with CDE. Under our recommendation, we believe many of these providers would shift to accepting voucher clients. Though accepting vouchers is a somewhat less predictable business model for them than direct contracting, Title 22 centers and homes have been operating under a voucher–based business model for decades.

Special Considerations for Migrant Program. When converting all Migrant Child Care slots into vouchers, the Legislature would need to consider whether it wanted to continue giving migrant children priority access. If the Legislature wishes to prioritize these children, it could do so within a single voucher program or it could retain a stand–alone voucher program reserved only for migrant children. Both approaches have benefits and drawbacks. Prioritizing migrant children within a single voucher program would create a more unified system. This approach, however, could result in other low–income children receiving less access if slots are limited and migrant children end up receiving a greater number of slots under the integrated program. Continuing to rely on a separate voucher program for migrant children would result in a more fragmented system but allow the Legislature to target funds to a certain number of migrant children in certain areas of the state.

Require Programs Serving Children Birth Through Age Three to Include Developmentally Appropriate Activities. We recommend the Legislature require all centers and FCCHs serving subsidized children birth through age three to include a developmental component to their care. (Under our preschool recommendations, four–year olds would receive developmentally appropriate care through preschool.) Under the current system, only a small share of children in subsidized child care birth through age three can access programs that are required to include such a component. We recommend the Legislature direct CDE to develop standards for children birth through age three that are similar to current Title 5 standards but modified to reduce programmatic and administrative burden. Requiring a developmental component in programs for these children likely would require some existing Title 22 providers to obtain additional training. This training could be supported with one–time funds provided during a transition period or redirected quality dollars.

Provide Similar Levels of Access Across the State. Given the variation in the proportion of eligible families served across the state, we recommend the Legislature equalize access across counties. The Legislature could consider addressing the differences across counties in various ways, including:

- Serve Same Share of Families in Each County. Under this option, the Legislature could adjust funding levels to serve the same share of eligible families in each county.

- Serve Families Based on Statewide Income Cut–Off. Under this option, the Legislature could adjust funding levels to serve all families under a certain percentage of state median income (SMI).

The first option accounts for regional differences in family income and cost of care. Under this option, higher–cost counties might serve eligible families with incomes closer to the cap. For example, families whose incomes were 60 percent of SMI might receive child care in high–cost counties whereas families with similar incomes in low–cost counties may not receive child care because all available slots are taken by families with lower incomes. By comparison, the second option treats all families across the state similarly regardless of regional cost differences. Under the second option, those counties with a greater share of families at the bottom of the income distribution would see more families served than those counties with relatively higher–income families. We believe either option would be an improvement over the existing ad hoc service levels across counties.

Update Eligibility Criteria to Be More Transparent. To create more transparency in terms of who is being served, we recommend the state link the income eligibility cap with recent SMI data. For the past several years, the state has linked the income cap to 70 percent of the 2007 SMI. This cap equates to about 60 percent of the 2014 SMI, the most recent year for which we have data. Updating the income cap to this level imposes no additional program cost. For purposes of establishing voucher eligibility, we recommend the state update the SMI annually based on the most recent data available (for example, using the 2015 SMI when preparing the 2017–18 budget).

Create Simpler, More Transparent Reimbursement Rate Structure. As part of a new voucher–based system, we recommend the Legislature eliminate the current reimbursement rate structures and replace with one simplified, market–driven structure. Looking at the most recent RMR survey indicates that the differences across counties generally cluster into three groups. Urban and coastal counties tend to be the highest–cost counties, with monthly school–age rates varying less than 4 percent. The medium–cost counties (including San Bernardino and Sacramento) also have monthly rates that vary less than 4 percent. The low–cost counties (which tend to be the rural northern counties) have somewhat more variation, 7 percent on average. Given these groupings, we recommend the state create a system with three reimbursement rates (tiers 1, 2, and 3) to reflect basic cost differences among counties. This system would replace the state’s existing RMR structure which provides unique rates to every county. Understanding the new system therefore would be much easier yet the rates still would remain connected to the child care market and accurately reflect notable cost differences among counties.

To Start, Set Reimbursements at the 65th Percentile of Most Recent Survey. As a first step in moving toward a new rate structure, we recommend the Legislature link the rates to a specified percentile of the 2014 RMR survey based on available funding. We estimate that setting the initial reimbursement rates at about the 65th percentile would allow the state to serve the same number of children without additional cost. (This estimate assumes $143 million now used for CSPP wrap at non–LEAs is available for vouchers and slots for three–year olds now funded by CSPP are converted to vouchers.) For each of the three groupings of counties, the 65th percentile of the applicable counties could be averaged to set the corresponding rate. Setting the initial rates using the most recently available data helps lay a more appropriate foundation for the new rate structure. (To the extent additional funds were available, the state could link rates to a higher percentile in future years.)

Reinstate CELs so State Can Track Demand for Subsidized Child Care. To help families access care, equalize service levels across the state, and make corresponding funding adjustments, we recommend the Legislature reestablish consolidated waiting lists. We estimate restarting CELs would cost between $5 million and $10 million annually. (The previous CEL contracts cost approximately $8 million annually.)

Establish Regional Monitoring System for Programs Serving Children Birth Through Age Three. We recommend the Legislature establish a regional monitoring system for programs serving children birth through age three. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature direct CDE to contract with regional nonprofit or public entities (such as AP agencies or county offices of education) to inspect and monitor centers and FCCHs to ensure they meet required standards. Based on funding provided for similar monitoring systems within California, we believe the cost of the regional system would be in the low tens of millions of dollars. These costs could be covered by redirecting remaining quality dollars, redirecting existing administrative funds, or augmenting funding for AP agencies or county offices of education. (Moving forward, the state also could consider whether CDE should play a role in ensuring consistency in the monitoring of providers.)

Transition

Main Elements of a Transition Plan. In the first year of the transition to a fully voucher–based system, we recommend the state create a new reimbursement rate structure, monitoring system, and program standards, as well as develop associated regulations. In year two, we recommend beginning to implement the changes by applying the new reimbursement rates to all existing voucher slots, beginning to convert contracted slots to vouchers, beginning to equalize service levels across counties, providing some one–time funds to help providers learn about and meet any higher program standards, and designating a small amount of ongoing funds for reinstating the CELs. In years three through five of the transition, we recommend the state complete the phase out of contracted slots and the equalizing of service levels across counties.

Task CDE With Working Through Certain Implementation Decisions. Many implementation decisions will arise if the Legislature pursues the Governor’s proposal to convert contracted slots to voucher–based slots. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s basic proposal to have CDE develop a transition plan but be more specific in what CDE is to address in the plan. Consistent with the elements laid out in the above paragraph, we recommend the Legislature task CDE with certain responsibilities, including developing regulations relating to modified program standards and a plan for converting contracted slots to vouchers.

After Initial Restructuring Plan Completed, Recommend State Examine Three Other Related Issues. After addressing the overarching issue of converting contracted slots to voucher slots, we recommend the Legislature consider three other areas for possible restructuring: (1) the CalWORKs stages of child care, (2) care for school–age children, and (3) the funding model for AP agencies. For CalWORKs care, the Legislature could explore ways to treat CalWORKs families more similarly to other low–income families. For school–age children, the state could consider alternative ways to coordinate and fund afterschool care and voucher–based care. For AP agencies, the state could consider funding models that might be more transparent and better linked to services provided.

Back to the TopConclusion

We commend the Governor for focusing attention on the state’s existing preschool and child care programs and putting forth proposals to improve them. As evident from earlier sections of this report, the state’s existing preschool and child care programs are fraught with inconsistencies in eligibility criteria, standards, funding rates, funding mechanisms, and oversight systems. Under these existing programs, otherwise similar children are treated differently for reasons such as their birth month or location. Given the breadth and depth of these existing problems, we encourage the Legislature to pursue restructuring of both subsidized preschool and child care. In both areas, our packages of recommendations are intended to help give the Legislature starting points. Should the Legislature wish to pursue restructuring, much work remains to be done. The Legislature would need to dedicate concerted attention over the next several months to develop plans for restructuring, then allow at least a few years for implementing those plans.

Preschool Restructuring

- Funding Streams. Consolidate $1.7 billion in Proposition 98 funding currently supporting the California State Preschool Program, Transitional Kindergarten, and preschool Quality Rating and Improvement Systems into one new preschool program.

- Eligibility and Access. Set specific, need–based eligibility criteria and offer program to all eligible children. (To be consistent with other programs for school–age children, Legislature could consider providing access to all children from families with incomes at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level.)

- Eligibility Verification. Require providers to determine eligibility only once per year and allow children to remain in program through the year regardless of changes in family circumstances.

- Convenience for Families. Require providers to offer full–day preschool programs for children from low–income, working families.

- Program. Require providers to create plans for their programs. Provide substantial local flexibility in developing these plans but require all programs to include developmentally appropriate activities. Also require providers to meet minimum staffing requirements in terms of teacher training and child–to–teacher ratio, as determined by the state.

- Funding Rules. Allocate funding to providers based on the number of eligible children who participate in the program. Have hold harmless provision only during transition to new system.

- Reporting. Require providers to post their preschool plans on their websites. Also require providers to collect basic demographic information on participating children and report that information to the state. Consider requiring the California Department of Education to report preschool participation rates by county.

Child Care Restructuring

- Move to Vouchers. Transition General Child Care and contract–based Migrant Child Care slots into voucher–based slots over five years.

- Eligibility and Access. Update income eligibility criteria to be based on most recent state median income data. Equalize service levels across the state. Reinstate centralized eligibility lists so the state can track demand for subsidized care.

- Program. Require programs serving children birth through age three to include developmental component in care.

- Funding. Replace existing reimbursement rate structure for vouchers with a simplified, market–driven structure that has three reimbursement tiers reflecting basic cost differences across counties. Initially set reimbursements at the 65th percentile of the 2014 survey (could be accomplished with existing resources).

- Oversight. Establish regional monitoring system for programs serving children birth through age three to ensure they meet required developmental standards.