In This Report

LAO Contact: Natasha Collins

August 18, 2016

Improving Workforce Education and Training Data in California

Executive Summary

Background

State Has Extensive Array of Workforce Programs. In 2016–17, eight state agencies received a total of more than $6 billion in state and federal funding to administer almost 30 workforce education and training programs. Community colleges and schools are the major providers of workforce education and training, relying primarily on state funds to support these programs. The Department of Social Services and the Employment Development Department (EDD) also receive a notable amount of funding to support workforce programs, primarily from federal funds. Other agencies also administer various workforce programs, though these programs tend to be smaller. The state tasks the California Workforce Development Board (CWDB), an appointed body with broad stakeholder representation, with developing an overarching strategic workforce plan every four years. This plan is intended to serve as a framework for the development of policy, spending, and operation of all workforce programs in the state.

Programs Typically Report on Participants and Outcomes. Most workforce education and training programs require service providers to report information about their program participants, including demographic information. Many programs also require information about participants’ near–term outcomes, such as the share of students completing training programs or earning certificates. Increasingly, programs also require information about longer–term outcomes, such as subsequent employment and earnings.

State Agencies Must Link Some of Their Workforce Data to Meet Current Reporting Requirements. To collect information about program participants’ longer–term outcomes, state agencies often must share and link data with one another. For example, CCC must link data on students completing workforce education programs with EDD data to determine whether those students successfully transition into the workforce. California’s agencies currently link their data using agency–to–agency agreements. Agencies in other states link their data using different methods, with some states relying upon a central repository of data managed by a central agency and other states using a federated data system in which agencies maintain their data in–house but permit other agencies access to some of that data through a shared interface.

Assessment

Outcome Measures Historically Have Not Been Standardized. Historically, state and federal laws have required service providers to report different types of outcome information even for similar workforce programs with comparable goals. Such differences frustrate efforts by providers, state agencies, and the Legislature to aggregate data across different programs, compare program outcomes, and assess the overall system’s performance. Such differences also increase providers’ and state agencies’ administrative burdens.

Some Recent Progress Using Common Outcome Measures, but Work Remains. To address these concerns, the federal government standardized outcome measures for all programs funded through the recently reauthorized Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). The state’s workforce plan indicates that it eventually intends for state–funded workforce programs to align their outcome measures with the new federal WIOA measures. Though somewhat different from the WIOA measures, the California Community Colleges (CCC) recently standardized outcome measures for most of its career technical education programs. Despite these developments, many state workforce programs still require providers to track different performance measures.

Current Efforts to Link Data Inefficient and Burdensome. A further problem is that the state’s current data–sharing model, the agency–to–agency model, is fragmented and time consuming for state agencies to navigate. It also is not comprehensive, as not all relevant agencies link with all other agencies serving the same participants. Compared to the agency–to–agency model, both the central repository and federated models have notable advantages, including greater accuracy, efficiency, and comprehensiveness.

Recommendations

Recommend Requiring Development and Use of Common Measures for All Programs. We recommend the Legislature convene a task force to adopt common workforce participation and outcome measures. We recommend including the standardized WIOA measures, with a few additional state–specific measures. After adopting common measures, we recommend the Legislature require all of the state’s workforce programs to collect and report data for those measures. We recommend streamlining all existing data and reporting requirements accordingly, amending statute as necessary.

Recommend Improving Data Linkages Using Systemwide Model. We recommend the Legislature direct the CWDB to study and report on potential approaches for replacing existing agency–to–agency agreements with a statewide, streamlined data–linking system for all workforce programs in the state. After reviewing this report, the Legislature could authorize a preferred data–linking system in statute. Once the new system is in place, we recommend the Legislature require state agencies and workforce providers to participate in it, contributing specified data.

Recommend Using the Resulting Data to Inform Budget and Policy Decisions. In concert with adopting common measures and creating a streamlined data–linking system, we recommend the Legislature direct the CWDB to develop a small number of standardized reports designed to communicate results clearly to policy makers, service providers, current and prospective program participants, and the public. We recommend the Legislature annually review these reports as part of its budget and policy processes, taking program results into consideration when adjusting budgets and refining state laws. We also recommend directing state workforce agencies to develop and adopt a uniform protocol by which researchers could gain access to the data. Such a protocol should contain appropriate safeguards for participant privacy and confidentiality. By conducting third–party analysis of workforce data, researchers could help inform state policy and fiscal decisions, thereby increasing the value of the data collected.

Introduction

Workforce education and training programs provide job–specific training, basic skills education, and related support services to help individuals participate in civic life and the labor market. We estimate that over three million people access services funded by the state’s almost 30 workforce education and training programs annually. Though the state’s workforce system is extensive, policy makers currently cannot answer basic questions about it. For example, even getting an exact count of the people who use the state’s workforce programs is difficult. With programs administered by so many agencies and providers, data housed in so many places, data requirements varying by program, and key data elements linked only in limited situations, policy makers routinely struggle to assess whether individual workforce programs and the system overall is effective. Though the state’s workforce system has had these shortcomings for many years, recent changes in federal law and some recent state actions are requiring workforce programs to collect more standardized data in a more coordinated way. These changes signal an opportunity for the state to reconsider its approach to workforce data.

We begin this report by providing background about the state’s workforce programs and their data reporting requirements. We then provide information about standardizing performance measures and linking data across entities. Next, we evaluate how well current data collection practices provide information about programs. We conclude by making recommendations regarding the next steps the Legislature could take to improve the usefulness of workforce data in California.

California’s Workforce Programs

Eight State Agencies Administer Workforce Programs. The California Community Colleges (CCC) Chancellor’s Office and the California Department of Education (CDE) are the main state–level administrators of workforce education and training programs. The California Department of Social Services (DSS), the California Employment Development Department (EDD), and the California Department of Rehabilitation (DOR) also administer large workforce programs. Three other state agencies—the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), the California Conservation Corps, and the California Prison Industry Authority—administer relatively smaller workforce programs targeted to more select populations.

California Spends More Than $6 Billion Annually on Almost 30 Workforce Programs. Figure 1 lists 29 publicly funded workforce programs currently operating in California. The Appendix contains descriptions of each of these programs. The funding amounts shown understate spending on workforce education and training because they do not include any portion of the unrestricted funding that high schools receive through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Under this formula, high schools receive a per–pupil funding rate intended to recognize the higher costs of career technical education (CTE). The state’s accounting system, however, currently does not have the capability to track LCFF spending specifically on CTE. Statewide, districts likely spend between hundreds of millions of dollars and billions of dollars on CTE. The large range is due to varying definitions of what to count as CTE instruction and support.

Figure 1

Funding for Workforce Education and Training Programs in California

2016–17 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Agency |

State General Fund |

Other Fund Sourcesa |

Total Funding |

|

Apportionments for workforce education and training |

CCC |

$2,122b |

— |

$2,122 |

|

Adult Education Block Grant |

CDE/CCC |

505c |

— |

505 |

|

Career Technical Education Incentive Grants |

CDE |

300d |

— |

300 |

|

CalWORKs employment and training services |

DSS |

233 |

$1,094 |

1,327 |

|

Strong Workforce Program |

CCC |

200 |

— |

200 |

|

Office of Correctional Education programs |

CDCR |

199 |

— |

199 |

|

Office of Offender Services workforce programs |

CDCR |

114 |

43 |

156e |

|

Vocational Rehabilitation |

DOR |

59 |

364 |

423 |

|

Apprenticeships |

CDE/CCC |

54 |

— |

54 |

|

Career Technical Education Pathways Program |

CDE/CCC |

48f |

— |

48 |

|

Project Workability for students in special education |

CDE |

40 |

— |

40 |

|

CCC Student Services for CalWORKs Recipients |

CCC |

44 |

— |

44 |

|

Core Training Program |

Corps |

42 |

48 |

91 |

|

Economic and Workforce Development Program |

CCC |

23 |

— |

23 |

|

California Partnership Academies |

CDE |

21 |

— |

21 |

|

Adults in Correctional Facilities |

CDE |

15 |

— |

15 |

|

Nursing program support |

CCC |

13 |

— |

13 |

|

Specialized Secondary Programs |

CDE |

5 |

— |

5 |

|

Agriculture Incentive Grants |

CDE |

4 |

— |

4 |

|

Adult, Youth, and Dislocated Worker Services (WIOA Title I) |

EDD |

— |

418 |

418 |

|

Wagner–Peyser Employment Services (WIOA Title III) |

EDD |

— |

127 |

127 |

|

Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act Program |

CDE/CCC |

— |

123 |

123 |

|

Adult Education and Family Literacy Program (WIOA Title II) |

CDE/CCC |

— |

85 |

85 |

|

Employment Training Panel |

EDD |

— |

73 |

73 |

|

CalFresh Employment and Training Program |

DSS |

— |

63 |

63 |

|

Jobs for Veterans State Grant |

EDD |

— |

20 |

20 |

|

CDE Student Services for CalWORKs Recipients |

CDE |

— |

10 |

10 |

|

Proposition 39 pre–apprenticeships |

EDD |

— |

3 |

3 |

|

Offender Development programs |

CalPIA |

3g |

2h |

5 |

|

Totals |

$4,044 |

$2,473 |

$6,517 |

|

|

aLargely federal funds with some special funds. bExtrapolated from best available data. Assumes community colleges spend one–third of apportionment funding on core adult education areas. c$5 million is one–time funding for technical assistance to regional consortia. dReflects second–year funding for three–year, $900 million grant program. eReflects funding for wraparound services, which include workforce education and training. fEnacted legislation sunsets program July 1, 2017 and folds funding into Strong Workforce Program. gTransfer from CDCR. hFunded through sale of CalPIA goods. Assumes program will sell the same value of goods as in 2015–16. |

||||

|

CCC = California Community Colleges; CDE = California Department of Education; DSS = California Department of Social Services; CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; DOR = California Department of Rehabilitation; Corps = California Conservation Corps; WIOA = Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act; EDD = California Employment Development Department; and CalPIA = California Prison Industry Authority. |

||||

State and Federal Governments Provide Significant Workforce Funding. Of the $6.5 billion identified in Figure 1, 62 percent ($4 billion) is state funding. State funding primarily supports workforce education and training programs provided through CCC and CDE. The remainder of the funding is mostly federal, with a small amount from state special funds (such as the Clean Energy Job Creation Fund). Federal funding primarily supports workforce programs provided through DSS, EDD, and DOR. The largest federal workforce programs are the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) employment and training services program, supported with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families funding, and the various programs funded by the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). Some workforce programs, including CalWORKs, Offender Services, and Vocational Rehabilitation, receive funding from both the state and federal governments.

State Workforce Plan Provides Overarching Vision. The WIOA has particular importance for state workforce policy because it requires each state to prepare an overarching strategic workforce plan every four years. Federal law requires that the plan lay out a vision and goals for preparing a skilled workforce and meeting employers’ needs. The state also is required to set specific growth targets for WIOA–funded programs related to WIOA’s performance accountability measures (discussed further below). The state negotiates these targets with the federal government. Upon its development, the plan is intended to serve as California’s framework for all workforce–related policy and program decisions as well as federal and state spending decisions.

California Workforce Development Board (CWDB) Tasked With Developing the Plan. The CWDB is the state’s designated coordinating body for workforce issues and consists of 53 members appointed by the Governor. The board consists of a broad group of stakeholders, including representatives of the Legislature, business, labor, education, and corrections. The U.S. Department of Labor required states to submit their workforce plans for the 2016 through 2020 period by April 1, 2016. States were to begin transitioning to the new plans beginning July 1, 2016 and are required to fully implement the plans by July 1, 2017.

State Plan Outlines Primary Goals and Identifies Policy Strategies to Meet Goals. California’s workforce plan revolves around a few key goals. Most notably, the plan sets a goal of producing a million “middle–skill,” industry–recognized, postsecondary credentials in areas with labor market value by 2027. (The plan defines these credentials as associate degrees, certificates, and professional certifications and licenses that do not require a baccalaureate degree.) The state plan also sets a goal of doubling the number of people enrolled in apprenticeship programs. To meet these goals, the plan identifies various policy strategies, such as increasing support services to participants in workforce programs, increasing the number of “earn and learn” opportunities (including apprenticeships), and building data capacity across agencies administering workforce programs.

Workforce Data

Historical State and Federal Data Reporting Requirements

State and Federal Programs Require Data on Participants and Outcomes. Most workforce education and training providers are required to submit information about the number of participants in their programs, typically including some associated demographic data, such as the participants’ age, gender, and ethnicity. In some cases, providers must collect data on whether participants have financial need and qualify for grant or loan assistance. In addition, programs often must report certain outcomes. Both state and federal programs typically require providers to report on participants’ near–term outcomes, such as program completion, test scores, and certificates or diplomas awarded. Increasingly, data requirements also include participants’ longer–term outcomes, such as subsequent employment, earnings, and enrollment in further education or training. Federal workforce programs require data on participants’ longer–term outcomes more commonly than state programs.

State Often Asks for Different Sets of Data Across State Programs. Some workforce programs with very similar goals require providers to collect somewhat different performance data. For example, CCC and CDE jointly administer the CTE Pathways Program and the Career Pathways Trust program. (Career Pathways Trust grants were awarded in 2013–14 and 2014–15 and schools can spend the funding through 2016–17.) Both programs provide funding to schools and colleges to create career pathways from high school into postsecondary education and the workforce, yet state law requires that each program report different information. State law requires CTE Pathways Program grantees to report on the wages of program graduates, whereas Career Pathways Trust grantees must report on students’ transitions related to employment, apprenticeships, and job training. Similarly, CDE administers both the California Partnership Academies (CPA) and the Specialized Secondary Programs (SSP). Each of these programs provides high schools with funding to create programs that focus on a career theme. For the CPA, the state requires grantees to annually report attendance, credits earned, test scores, grade point averages, graduation rates, and postsecondary plans. For the SSP, grantees have more flexibility in what data they annually report to the state. For example, grant recipients may choose to report either improvement in participants’ grade point averages or “other appropriate standards of achievement.”

Even for Same Types of Outcomes, Measures Can Differ. Even when programs share the same goals and require providers to track the same types of outcomes, specific outcome measures can vary. For example, programs often are required to report on their participants’ subsequent employment and wages. These measures, however, differ among programs in timing, with some measures focusing on outcomes within three or six months of program completion and others looking out three or five years. In addition, some measures consider only employment in a job related to the training a participant received, while others include any employment or wage gains. Such differences frustrate efforts to aggregate data across different programs, compare outcomes among programs, and assess the overall system’s performance. Such differences also increase administrative burdens for agencies and providers, which may need to track outcomes differently for various funders and programs.

Recent Moves Toward Common Measures

In recent years, efforts at various levels of government have sought to address the problem of collecting different outcomes for similar workforce programs. We describe these efforts below.

Federal Government Expanded the Use of Common Measures for Its Workforce Programs. Although some federal workforce programs used common data measures in the past, WIOA updated and expanded the use of common measures to all workforce programs funded under its provisions. As shown in Figure 2, these measures include skill gains, employment, and earnings.

Figure 2

WIOA Common Performance Measuresa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aApplies to Adult, Youth, and Dislocated Worker (WIOA Title I), Adult Education and Family Literacy (WIOA Title II), Wagner–Peyser (WIOA Title III), and some of the Rehabilitation Act programs. bThe U.S. Department of Labor is in the process of developing measure. WIOA = Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. |

State Working Toward Common Measures. The CWDB has committed in the state workforce plan to assist state programs in aligning their outcome measures with the WIOA measures. Separately, Chapter 13 of 2015 (AB 104, Committee on Budget) requires CDE and the CCC Chancellor’s Office to develop common measures of effectiveness for adult education programs. In a November 2015 report, the two agencies identified a minimum set of enrollment and outcome information aligned with WIOA requirements that all adult education providers must report and recommended that the state create a centralized clearinghouse to track student outcomes.

Community Colleges Using Common Measures for Workforce Programs. The Chancellor’s Office developed its own set of common measures for most CCC workforce education and training programs and implemented them beginning in 2014–15. The Chancellor’s Office recently aligned several of these measures with the WIOA common performance measures and is in the process of modifying more of its measures to align with WIOA measures.

California’s Workforce Data Collection and Reporting Systems

Each Agency Typically Has One Major Data System. State agencies that operate workforce programs each have one primary data system to which providers report information about program participants. For example, at CDE, the majority of student data is collected in the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS). Similarly, CCC’s primary data system is the Chancellor’s Office Management Information System (COMIS), DOR’s primary data system is Accessible Web–based Activity Reporting Environment (AWARE), and CDCR’s primary data system is the Strategic Offender Management System (SOMS). Each of these systems compiles data from numerous local service providers into a statewide database.

In Addition, Ad Hoc Data Systems Proliferate. Rather than adding new data elements to their primary systems, which can be costly and time consuming, agencies sometimes create ad hoc data systems to fulfill new reporting requirements as they implement new programs. This practice is especially common for programs with unique data requirements, limited–term programs, and programs with tight reporting deadlines. For example, for the 12 workforce education and training programs CDE administers either alone or jointly, it uses at least six separate internal data systems to collect and store performance data. Moreover, in 2015–16, the first year of the Adult Education Block Grant, the CCC and CDE used a temporary data system to collect performance information from adult education providers in order to comply with their annual reporting requirement to the Legislature and administration.

Some Agencies Display Selected Data Publicly. Agencies sometime provide aggregate information about their program participants to the public. For example, the CCC Chancellor’s Office makes publicly available some aggregate information on students, course taking, and student outcomes through its online Data Mart, Student Success Scorecard, Salary Surfer, and Wage Tracker tools. Likewise, CDE makes publicly available some aggregate information about students, course taking, and short–term outcomes on its online DataQuest and Ed–data.org tools.

Data Linking

The Value of Linked Data

Data Linking Enables Providers and Policy Makers to Track Participation Across Programs. Data linking refers to matching participant records from two or more programs or agencies and using those linked records to track participation and outcomes. In the workforce area, this process is essential for illuminating which programs are working well. For example, linked data can show if students who complete high school–equivalency programs at adult schools successfully transition to community colleges or other training programs. Linked data also can show if students who begin a program in one agency complete a similar program in another agency (perhaps due to relocating). Data linking also can identify gaps and duplication of services.

Data Linking Provides Information About Longer–Term Impacts of Programs. In addition to facilitating tracking across programs, data linking enables policy makers to track participant outcomes over time. As noted earlier, state and federal programs increasingly require information about program participants’ eventual employment, wage gains, and enrollment in further education. Linking data across state agencies over certain periods of time can provide this information. For example, to learn how many students continued their education and training and/or went to work in a particular industry, a high school CTE program could link its student information with CCC and EDD data for periods ranging from one semester to several years after high school graduation.

Federal Workforce Act Requires Data Linking Across Some State Agencies. As part of WIOA implementation, the federal government is requiring states to establish an integrated data system to which WIOA–funded programs would contribute participant and outcome data. The purpose of the requirement is to improve state agencies’ ability to (1) coordinate service delivery across programs and (2) record outcomes across programs in a single report.

Examples of Data Linking

Various entities already are linking data across workforce education and training providers to track program participation and outcomes.

Some National, Regional, and State–Level Data Linking. At the national level, the U.S. Department of Education has developed the College Scorecard, which links data from colleges and universities with federal student financial aid and tax data. For a given college, the Scorecard provides information about admissions, student demographics, completions, costs (by family income), student aid (including student loan repayment rates), and the average earnings of students after attending the college. At the regional level, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education is piloting the Multistate Longitudinal Data Exchange, which links several western states’ higher education and employment data to provide information about student outcomes across state lines. At the state level, several states routinely link K–12 education, postsecondary education, and employment and wage data through longitudinal systems to provide information about students’ progression through the educational system and post–graduation outcomes. Florida, Texas, and Virginia have among the most comprehensive of these systems.

Linked Data in California. Although WIOA requires states to develop a comprehensive approach to linking data, California does not have a linked education or workforce data system. Various entities, however, have made efforts to link information to track program participation and outcomes over time. These efforts include Cal–PASS Plus, created and funded through the CCC Chancellor’s Office, which links data for some K–12 and higher education agencies with each other and with workforce outcome data. In addition, the state tasked the CWDB in 2014 to produce a tool known as the Workforce Metrics Dashboard, which shows wage and employment outcomes for certain workforce programs. (The Dashboard likely will be available in late 2016.) Some state agencies also are linking data. For example, the CCC Chancellor’s Office has developed the state–level CCC Salary Surfer and the college–level College Wage Tracker, both of which use linked CCC and EDD data to make information on median wages by program of study publicly available. At the provider level, the Bay Area Community College Consortium, consisting of 28 community colleges in the region, is exploring the development of a data system that would link information about students enrolled in the region’s community colleges and adult education programs.

Three Models for Linking Data

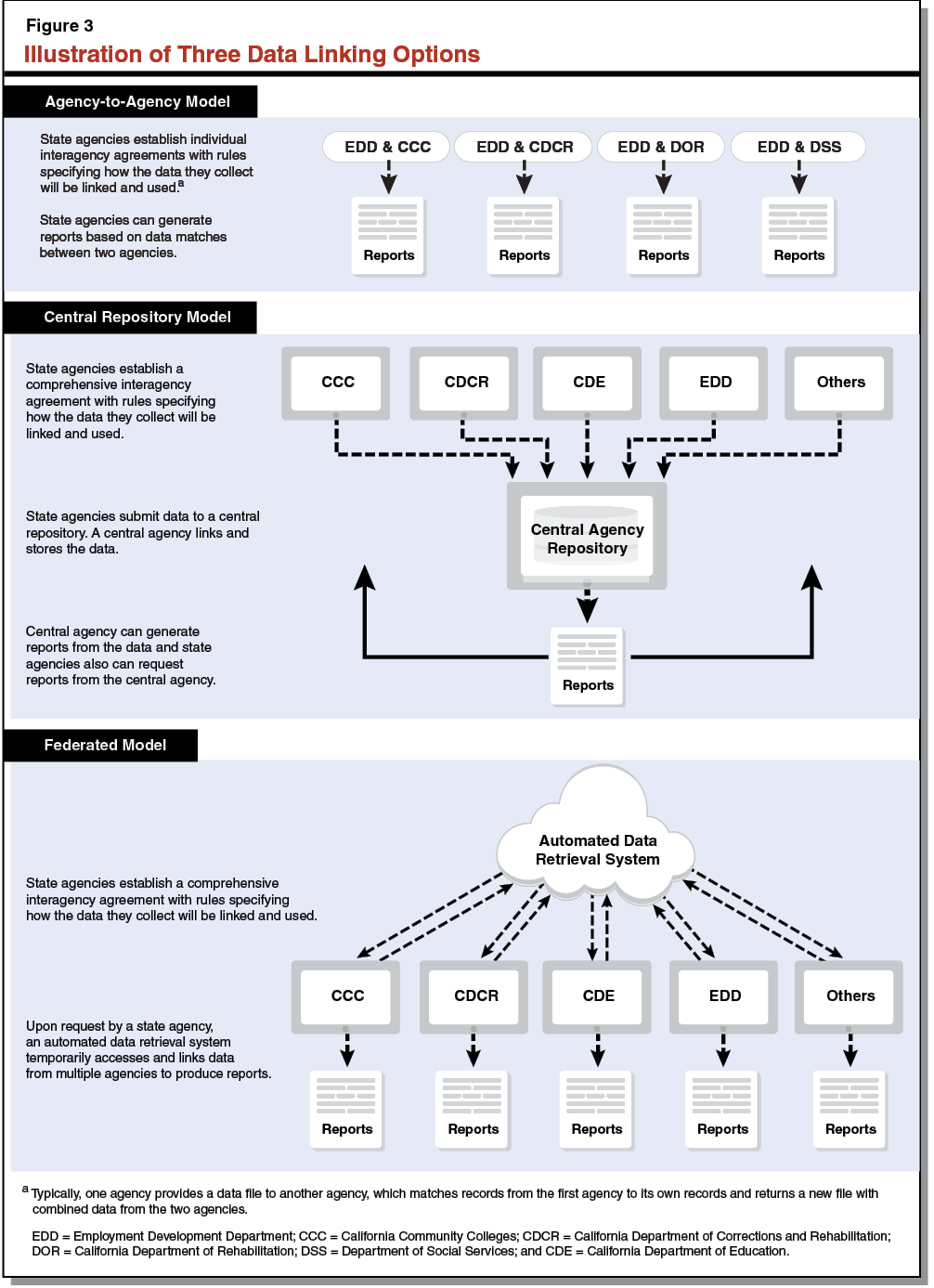

Entities typically link participant data to measure longer–term outcomes using one of three models. Figure 3 shows these models.

Agency–to–Agency Model. Under this model, two agencies enter into a memorandum of understanding to share selected data for specified purposes on a one–time or recurring basis. Participating agencies determine the terms and conditions, as well as the mechanics, for linking their data. Additionally, the memorandum of understanding specifies who can access the data and for what purposes it will be used. In California, data linking for workforce education and training programs occurs only through agency–to–agency agreements. As the top of Figure 3 shows, CCC, CDCR, DOR, and DSS each have entered into separate agency–to–agency data sharing agreements with EDD to collect information about their participants’ wage gains. Notably, CDE has not linked its data with EDD records. In California, many other agency–to–agency agreements relate to the sharing of many other elements of workforce data.

Central Repository Model. Under a central repository model, agencies send their data to a central agency, such as a higher education coordinating board, which maintains a data repository or “warehouse.” As the middle section of Figure 3 shows, once an agency submits its data, the central agency links it to other data in the warehouse. The central agency (and sometimes other authorized agencies) can then query and use the data. In 1999, the Legislature directed the California Postsecondary Education Commission to develop a central repository that linked data across state education institutions. This repository, which included some data going back to the late 1980s, operated until 2011. Many other states—including Florida, Texas, and Washington—currently use this model to link their education and workforce data.

Federated Model. Under a federated model, sometimes called an “integrated data system,” agencies maintain their data in–house and permit other agencies access to some of that data through a shared interface (see the bottom section of Figure 3). Using automated processes, the shared interface can link data from multiple agencies upon the request of one or more agencies and with the approval of all affected agencies. While this model is newer and (to date) less common than the central repository model, several states, including Virginia and Illinois, use it to link their data.

Other Considerations When Linking Data

Regardless of the data–linking model entities use, issues arise about how to identify participants and protect their privacy. We describe these considerations in more detail below.

Common Identifiers Facilitate Data Linking. A key step in linking data is identifying individuals who appear in two or more data sets. This requires a common individual identifier that agencies can use to match the records. For example, CCC and EDD both document Social Security numbers in their records and can use these numbers to identify individuals who both (1) attended a community college program and (2) earned reportable income following completion of the program. Use of Social Security numbers is not universal. State law does not allow schools to collect these numbers for K–12 pupils, complicating CDE’s ability to link records with CCC and EDD. Similar issues arise for programs that serve undocumented immigrants.

Workarounds Used When Common Identifiers Are Not Available. Agencies have developed two workarounds for reporting employment outcomes in the absence of a common identifier. One method is to survey former participants about their longer–term outcomes. This survey data tends to yield information that is less reliable than official wage data and typically is used by agencies that do not link data through any of the three models described above. The other workaround is to use “fuzzy matching.” Fuzzy matching uses several personal characteristics, such as name, date of birth, gender, and address to link information about an individual across separate data systems. As the name implies, fuzzy matching is not as precise as a common identifier, but it commonly is understood to be the next best option, providing a reasonably valid and reliable way for linking data. Agencies that use any of the data–linking models described above often use this method to identify participants when common identifiers are not available.

Agencies Must Address Privacy and Security Concerns When Sharing Data. State and federal laws allow sharing of education data across agencies for legitimate educational and research purposes. These laws also require agencies to safeguard participant privacy. To comply with legal requirements, agencies sharing data with each other typically develop formal data sharing agreements to establish (1) rules about how and to whom data can be disclosed and (2) steps agencies will take to prevent unauthorized access to the data. We discuss these issues in more detail in the nearby box.

Data Privacy and Security

State and Federal Privacy Laws Permit Data Sharing for Legitimate Educational and Research Purposes. The federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the California Information Practices Act, portions of the California Education Code, and several other federal and state laws govern the privacy and confidentiality of student records. These laws generally prohibit schools from disclosing personally identifiable student information to a third party (someone other than the student and his or her educational institution) without a student’s or parent’s permission. The laws, however, make several exceptions. Under FERPA, for example, a school may disclose personally identifiable information in connection with a student transferring schools or qualifying for financial aid. A school also may disclose records to researchers conducting studies on behalf of the school, and to federal or state agencies evaluating publicly funded education programs. State laws largely align with the protections outlined by FERPA yet further require that any third party receiving personally identifiable student information for research purposes be approved by an institutional review board.

Agencies Are Responsible for Data Security. Specifically, federal and state agencies are required to adopt administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to protect personal information from potential threats to its confidentiality and security. Agencies have employed various methods to safeguard data, including encrypting data, removing personal identifiers after linking two data sets but before sharing the results with a third party, and omitting results that have only a few observations (such as data on members of a very small group within a school). Agencies are responsible for providing adequate personnel training and oversight to ensure these data–security systems work.

Assessment

Despite having made some progress, the state still lacks data measures that are applied systemwide and it still does not have a coordinated data–linking approach. These two key shortcomings hinder policy makers’ ability to examine performance across California’s workforce education and training system. We discuss these issues in more detail below.

Recent Progress Toward Common Measures, but Work Remains

Some Programs Use Common Measures . . . When fully implemented, the federal requirement that common measures be applied to all WIOA–funded workforce programs will improve the usefulness of the state’s workforce data, allowing policy makers to examine participation and outcome data consistently across those programs. Efforts to establish common measures for certain state–funded programs will further enhance the usefulness of California’s workforce data. Similarly, recent efforts to use common adult education outcome measures across all providers is resulting in more useful data.

. . . But State Still Does Not Apply Common Measures to All Programs. The state’s WIOA–funded programs, CalWORKs employment and training program, CCC workforce programs, and various other state programs (such as the CTE Pathways Program and the Career Pathways Trust) still do not all share a set of common measures.

Current Method of Linking Data Falls Short

Current Efforts to Link Data Inefficient and Burdensome. The state’s current linking model, the agency–to–agency model, is a fragmented and time–consuming method to link data across agencies. It also is not comprehensive, as not all relevant agencies link with all other agencies serving the same participants. Moreover, the model is inefficient both administratively and technically. It requires that each agency’s legal counsel negotiate individual agreements with every other participating agency. In addition, the model often requires an agency to develop a unique technical approach for working with every other participating agency because data are stored in different formats. Similarly, the surveys some agencies have developed to report outcomes in the absence of linked data are relatively burdensome and unreliable. In some cases, programs do not report any outcome data, despite reporting requirements. The nearby box provides an example of a longstanding program that has been unable to report longer–term outcomes due to lack of linked data.

Longstanding Program Demonstrates Fundamental Flaws in Existing System

Career Technical Education Pathways Program Has Certain Data Requirements. Chapter 433 of 2012 (SB 1070, Steinberg) reauthorized the Career Technical Education (CTE) Pathways Program, originally created by Chapter 352 of 2005 (SB 70, Scott). The program provides grants to consortia that include community colleges and high school districts. The primary goal of the program is to help regions develop sustainable policies to improve CTE pathways among schools, colleges, and industry organizations. The state has provided $586 million to date for the program. State law requires grantees to submit outcome data annually on (1) transitions from high school to postsecondary education and training and (2) wages of program participants. State law requires the California Community Colleges (CCC) Chancellor’s Office, in turn, to submit annual reports on the program to the Legislature and Governor.

Lack of Systematic Data Sharing Results in Data Requirements Not Being Met. The CCC Chancellor’s Office repeatedly has reported that evaluators cannot reliably assess longer–term outcomes of the program because grantees generally do not submit the required information. This is because no systematic way exists to link individual high school student data with longer–term outcomes such as postsecondary enrollment and wages. The 2014 CTE Pathways Program Annual Report noted, “few K–12 districts and colleges tracked student–level information for the Initiative, and in some cases when data were tracked, the information gathered was insufficient to follow students from one segment of the education system to the next or from school to employment.”

Systematically Linked Data Could Improve Decision Making. Policy makers often must rely on anecdotal evidence to make decisions because programs are limited in the outcomes they can reliably report without linked data. By contrast, the availability of systematically linked data could provide information about the types and volume of workforce education services currently provided across the state; the number of distinct individuals receiving these services; patterns of movement for participants across these services; short–term and long–term outcomes of programs, including participants’ employment and wage gains at various intervals following service delivery; and alignment of workforce education services with regional economic needs. Common and linked data also could permit service providers to compare participants’ outcomes across programs and examine factors that contribute to program success.

Other Linking Models Offer Notable Advantages Over Current Method

Both Central Repository and Federated Models Better Than Agency–to–Agency Model. Both the central repository and federated models would be more efficient than the agency–to–agency model because data sharing would be governed by a comprehensive master agreement rather than the numerous separate agreements that each agency otherwise would have to negotiate. Moreover, both the central repository and federated models would provide more accurate and complete information about participant outcomes because data linking would be much more systematic than under the agency–to–agency model.

Central Repository Model Has Certain Advantages Over Federated Model . . . On the one hand, the central repository model has been used by many states for many years and uses proven technology. It also may yield more reliable data than the federated model because the central agency typically reviews and validates the data submitted by participating agencies to the repository. In addition, data queries under this model tend to be conducted more quickly, as responding to them does not involve pulling new data from several agencies.

. . . But Federated Model Might Be More Suitable Today, and in California Context. On the other hand, the federated model has become more common in recent years due to certain advances in technology and information science. Largely as a result of these advances, the federated model improves data security by avoiding creation of a separate, large, linked, continuously maintained data repository for which security breaches are particularly serious. In the states currently using the federated model, the model also appears to have cultivated greater acceptance by participating agencies due to avoiding conflicts regarding control and stewardship of data. This is because data are not stored centrally or long term under the federated model. In California, an additional advantage of this model could be greater acceptance by policy makers who might be reluctant to create a state agency to oversee a central, longitudinal education data repository.

Recommendations

To help policy makers, providers, current and prospective participants, and the public gain access to linked, longitudinal data that would help them make better decisions regarding workforce education and training programs, we recommend (1) finalizing and applying common performance measures for all of the state’s workforce education programs; (2) establishing a statewide structure for linking data across agencies to determine programs’ longer–term outcomes; and (3) improving how data are used by communicating results, incorporating information into policy and budget processes, and facilitating policy research. We discuss each of these recommendations in more detail below.

Develop and Use Common Measures

Convene Group to Establish Common Performance Measures. We recommend the Legislature direct the CWDB, which includes representation from all major workforce providers, to lead a task force that would resolve remaining inconsistencies among performance measures for the state’s workforce programs. We anticipate that the resulting measures would include the new federal WIOA measures plus a small number of additional common measures that reflect other state priorities. The task force’s work should include the development of detailed data definitions, reporting schedules, and other specifications needed to ensure that agencies collect and report data to state and federal authorities in a consistent and efficient way. To ensure broad stakeholder input and buy–in, we recommend the Legislature direct the group to consult with workforce and economic development officials, employers, and other agencies that administer workforce programs as well as provide a public comment period.

Require Programs to Use the Measures. Following identification of statewide, common performance measures for workforce education programs, we recommend the Legislature amend state law, as needed, to align data reporting requirements with the common measures. Legislation also could clarify to which programs the common measures will apply by offering a clear definition of workforce education and training programs.

Streamline Data Linking Among Agencies

Replace Agency–to–Agency Agreements With a Systemwide Model. We recommend the Legislature direct the CWDB to study and report on potential solutions to developing a statewide, streamlined data–linking approach for all workforce programs. The CWDB already has begun working with various agencies to explore such a system, so we believe the task force could report back to the Legislature by July 2017. At that point, the Legislature could weigh the trade–offs of potential solutions. Regardless of the preferred solution, the system could be developed through collaboration among the participating agencies. We recommend the Legislature require workforce education and training programs, as a condition of receiving state funding, to participate in the new system, as applicable, to provide specified performance data.

Use Data to Inform State Budget and Policy Decisions

Once the state implements common measures and a streamlined data–linking model, the Legislature can start using the resulting information to inform its workforce funding and policy decisions.

Require Transparent, Periodic Performance Reporting. Regardless of the model the state adopts to link workforce data, we recommend tasking the CWDB with creating a small number of standardized reports that will communicate results clearly to policy makers, providers, participants, and the general public. Several states, for example, have implemented online performance dashboards to help users find and explore performance data. Beyond state policy makers, local providers could use the data to better guide program development, and interested individuals could use the reports to choose workforce education and training programs that are suitable for them.

Incorporate Information Into Budget and Policy Process. We recommend the Legislature annually review statewide workforce education performance data as part of its budget and policy processes. Specifically, the relevant legislative committees could ask state agencies administering workforce programs to discuss their performance results in hearings. This would give committees the opportunity to ask agencies questions about their programs’ effectiveness and describe their plans for improvement.

Require Access to Data for Policy Research. We recommend directing workforce education agencies to develop and adopt a uniform protocol by which researchers could gain access to data. Such a protocol should contain appropriate safeguards for participant privacy and confidentiality. By conducting third–party analysis of workforce data, researchers could help inform state policy and fiscal decisions, thereby increasing the value of the data collected.

Conclusion

The state’s current hodgepodge of workforce data requirements is cumbersome for agencies to manage and not very useful for informing state policy. Our recommendations to implement common measures and a statewide approach to data linking would reduce the administrative burden for state agencies that often struggle to meet disparate reporting requirements for their programs, negotiate cumbersome data–sharing agreements, and use labor–intensive surveys and other data collection strategies to compensate for lack of outcome data that could be available from other agencies. Taken together, we believe that our recommendations for improving the alignment, integration, and accessibility of workforce data would provide more useful information to help guide state policy and funding decisions and ultimately result in better workforce education outcomes for participants and the state.

Appendix

Workforce Education and Training Programs in California

|

Agency |

Description |

|

California Community Colleges (CCC) |

|

|

Apportionments for workforce education and training |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funds allocated to community college districts for credit and noncredit courses in basic skills, English as a second language (ESL), and career technical education (CTE). Workforce education and training comprises about one–third of CCC apportionment funding. |

|

Strong Workforce Program |

Ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for community colleges to provide regionally focused CTE and workforce programs leading to certificates, degrees, and other credentials. Funds can be used for various purposes, including purchasing equipment, convening consortia, redesigning curriculum, and making other enhancements to CTE instruction. |

|

Student Services for CalWORKs Recipients |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding and federal funding for community colleges to provide child care, work study, and job placement services to students receiving CalWORKs assistance. (CalWORKs provides cash aid and services to low–income individuals and families.) The CCC Chancellor’s Office distributes funding to colleges based on enrolled CalWORKs recipients. |

|

Economic and Workforce Development Program |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding to help community colleges identify regional workforce education and training needs in collaboration with (1) employers; (2) two advisory committees representing colleges and industry; and (3) business, industry, and economic development partners. Funds can be used for hiring CCC industry liaisons, supporting collaboration among stakeholders, and providing technical help to regional consortia in using workforce data. |

|

Nursing program support |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding for community colleges to increase the number of nursing program graduates. The CCC Chancellor’s Office allocates a portion of funds as a per–student supplement to expand or maintain capacity, improve student readiness for courses, help students prepare for national licensing exam, and provide faculty professional development. The Chancellor’s Office allocates another portion as a fixed amount for student assessment and retention activities. |

|

California Conservation Corps |

|

|

Core Training Program |

Ongoing non–Proposition 98 General Fund to provide Corps members with education and training services, including high school diploma and General Educational Development (GED) test, technical skills, career guidance, and job search assistance. |

|

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) |

|

|

Office of Correctional Education programs |

Ongoing non–Proposition 98 General Fund to provide academic and CTE programs to incarcerated adults at adult state prisons. The overall objective is to reduce recidivism. Prisons offer basic skills, CTE, and high school diploma and equivalency programs. |

|

Office of Offender Services workforce programs |

Primarily ongoing non–Proposition 98 General Fund to support various programs that prepare offenders for release and provide employment preparation, transitional employment, and job placement assistance upon release. The in–prison Transitions Program provides a curriculum for offenders on how to get and retain a job as well as information about services offered at America’s Job Centers of California. Reentry programs include (1) the Caltrans Parolee Work Crew Program (overseen by CDCR and Caltrans) that hires parolees to clear litter from roadways, and (2) the Female Offender Treatment and Employment Program that provides CTE training and employment services to female offenders. |

|

California Department of Education (CDE) |

|

|

Adults in Correctional Facilities |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding to county offices of education (COEs) and school districts that provide educational programs to inmates at county jail facilities. Coursework varies and the state does not track participation by subject area. Providers create memoranda of understanding with jails and apply to CDE to receive funding based on average daily attendance. |

|

Agriculture Incentive Grants |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding for high schools to support nonsalary agricultural education costs. Funds are commonly used to purchase equipment and pay for student field trips. Requires local match. |

|

California Partnership Academies |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding to high schools to operate small learning communities that integrate a career theme into academic classes in grades 10 through 12. Conditions of funding include a private sector match, an internship or work experience for students, and a common planning period for academy teachers. |

|

Student Services for CalWORKs Recipients |

Ongoing Proposition 98 and federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) funding for adult education programs and Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROCP) to provide adult education and training that leads to employment for students receiving CalWORKs assistance. CDE distributes funding to providers based on enrolled CalWORKs recipients. |

|

CTE Incentive Grants |

Proposition 98 funding for a three–year competitive grant program to support CTE. School districts, COEs, charter schools, and joint powers agencies (JPAs) may apply. Applicants that do not currently operate CTE programs, regions with high dropout rates, and rural areas receive funding priority. Requires a local match and ongoing commitment to fund programs after grant ends. |

|

Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding for a 2.6 percent LCFF add–on to the base rate for high school students. Some combination of base and add–on funds is intended to support the costs of offering CTE instruction. The add–on originally was calculated to reflect ROCP funding. (Districts also have discretion to use LCFF funds to support adult education.) |

|

Project Workability |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding for pre–employment training and employment placement for high school students in special education. Students are placed in employment and the program fully subsidizes their wages until they complete high school or turn 22 years old. |

|

Regional Occupational Centers and Programs |

Education agencies may choose to use their general purpose Proposition 98 funding for regionally focused CTE at high schools and regional centers. (Prior to 2013–14, the state funded ROCP through a categorical program.) Primarily serves high school students ages 16 through 18. |

|

Specialized Secondary Programs |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding for short–term competitive grants for school districts to pilot programs that prepare students for college and career. Ongoing Proposition 98 funding also supports two high schools specializing in math, science, and the arts. |

|

CDE and CCC Joint Programs |

|

|

Adult Education Block Grant |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding allocated by the CCC Chancellor’s Office to regional consortia of community colleges, schools districts, COEs, and JPAs. Consortia may offer adult education in seven areas of instruction: basic skills, CTE, ESL and citizenship, programs for adults with disabilities, workforce programs for older adults, certain caregiving programs for older adults, and pre–apprenticeship programs. Funding is based on consortia’s prior–year funding, performance, and regional need. |

|

Adult Education and Family Literacy Program |

Ongoing federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Title II funding allocated by CDE to numerous adult education providers, including adult schools, community colleges, libraries, and community–based organizations. CDE distributes funding based on student learning gains and other outcomes. |

|

Apprenticeships |

Ongoing Proposition 98 funding allocated by the CCC Chancellor’s Office to schools and community colleges to help support the classroom instruction component of apprenticeship training. Apprenticeships are paid, educational work programs that pair students with skilled workers for supervised, hands–on learning, typically in the skilled trades. Apprenticeships last from two to six years and commonly are sponsored by businesses or labor unions that help design and support the programs and recruit apprentices. |

|

Career Pathways Trust |

One–time Proposition 98 funding for two rounds of competitive grants administered by CDE in 2013–14 and 2014–15. Grants fund regional consortia of schools and community colleges partnering with local businesses to improve linkages between CTE programs and local workforce needs. Authorizes several types of activities, such as creating new CTE pathways, articulation agreements, and curriculum. Requires local match. Grantees have three years to spend the funding. |

|

Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act Program |

Ongoing federal funding allocated by CDE to schools, community colleges, and correctional facilities. May be used for a number of CTE purposes, including curriculum and professional development and the purchase of equipment and supplies for the classroom. Of these monies, 85 percent directly funds local CTE programs and the other 15 percent supports statewide administration and leadership activities, such as support for CTE student organizations. |

|

CTE Pathways Program |

Limited–term Proposition 98 funding (partly from the Quality Education Investment Act) administered by the CCC Chancellor’s Office to improve linkages among CTE programs at schools, community colleges, universities, and local businesses. Program has funded various activities, including developing CTE courses that meet college acceptance requirements, supporting CTE student organizations, and supplementing some related CTE programs, including the California Partnership Academies. Funding renewed annually since 2005. Scheduled to sunset June 30, 2017. |

|

California Department of Rehabilitation |

|

|

Vocational Rehabilitation |

Ongoing federal WIOA Title IV funding (and some state General Fund) to provide vocational rehabilitation services for adults and youth with disabilities, including employment, education, and job placement assistance. Funds career assessment and counseling, job search and interview skills training, career training, and assistive technology such as hearing aids. |

|

California Department of Social Services |

|

|

CalFresh Employment and Training Program |

Ongoing federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funding, with a county match, to operate employment and training programs for CalFresh recipients in select counties. (CalFresh provides federally funded food assistance to low–income individuals and families.) Services are generally similar to CalWORKs services. Locally administered by county human services departments. |

|

CalWORKs employment and training services |

Ongoing federal TANF funding, state funding, and county funding for employment services for very low–income families with children on CalWORKs. Services include job search assistance, mental health and substance abuse treatment, referrals to education and training, and on–the–job training. Locally administered by county human services departments. |

|

California Employment Development Department (EDD) |

|

|

Adult, Youth, and Dislocated Worker Services |

Ongoing federal WIOA Title I funding for America’s Job Centers of California (formerly known as OneStops). These centers provide workforce information, resources, and employment services to adults, youth, and dislocated workers. Services include job search assistance, career assessment, career counseling, on–the–job training, and adult education and training. Funds also support education and job programs, including YouthBuild and Job Corps, for youth ages 16–24 who are not in school or employed. |

|

Employment Training Panel |

Reimbursements from the state Employment Training Tax to support retraining programs for current employees and companies facing out–of–state competition, training programs for recipients of unemployment benefits, and training programs for employers that meet certain criteria, such as those that are located in regions of the state where the unemployment rate is significantly higher than the state average. |

|

Proposition 39 pre–apprenticeship support, training, and placement |

Special funds from the Clean Energy Job Creation Fund for competitive grants to regional workforce partners to implement and support “green” pre–apprenticeships that lead to industry–valued credentials, entry into apprenticeship, or direct employment in the energy–efficiency workforce. Funds may be used to provide training, support services, and job placement assistance. |

|

Regional Workforce Accelerator Program |

Discretionary federal WIOA Title I funds the state has chosen to use for providing competitive grants to regional workforce partners that use innovative strategies to address gaps in education and workforce, with the goal of replicating and applying the strategies to other regions of the state. |

|

SlingShot |

Discretionary federal WIOA Title I funds the state has chosen to use for providing competitive grants to regional workforce partners to support alignment of job seekers and market demand. Grantees must submit a plan that identifies a workforce challenge in the region and a strategy to address it. Requires local match. |

|

Jobs for Veterans State Grant |

Ongoing federal WIOA Title I funding to provide workforce services to veterans at America’s Job Centers of California. Services include assessments of education, skills, and abilities; career planning; and work–readiness skills training. Funding distributed based on the number of veterans seeking employment. |

|

Wagner–Peyser Employment Services |

Ongoing federal WIOA Title III funding to provide services to connect job seekers with available positions in the labor market. EDD works with employers to list job openings on an open online database known as CalJOBS. |

|

California Prison Industry Authority (CalPIA) |

|

|

Offender Development programs |

Funds collected through the sale of CalPIA inmate–produced goods support inmate CTE and employability programs. CalPIA partners with trade unions to provide CTE to inmates and operates the Inmate Employability Program, which requires CalPIA factory supervisors to help inmates develop work habits and job application materials, such as portfolios. |