We reviewed the proposed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) between the state and 13 bargaining units (Bargaining Units 1, 3, 4, 11 through 15, and 17 through 21). These employees are represented by Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1000, the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE) Locals 3, 39, and 501 (both Craft and Maintenance workers and Stationary Engineers), the California Association of Psychiatric Technicians (CAPT), and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME, Local 2620). This review is pursuant to Section 19829.5 of the Government Code.

(Corrected 1/19/17: Changed parenthetical about retiree health benefits for SEIU Local 1000.)

(Corrected 1/17/17: Changed Figure 3 to reflect 2015-16 normal costs and pay. Added text to refer to figure.)

(Updated 1/13/17: Added parenthetical about retiree health benefits for SEIU Local 1000.)

(Corrected 1/11/17: Removed reference to PEPRA employees being required to pay one-half of normal cost under PEPRA.)

LAO Contact

January 10, 2017

MOU Fiscal Analysis:

Bargaining Units 1, 3, 4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, and 21

In December 2016, the administration submitted proposed agreements between the state and 13 of the state’s 21 employee bargaining units. These employees and their managers collectively represent more than 60 percent of state government’s non-university employees. Following our quick review of thousands of pages of agreements and supporting documents, this analysis fulfills our requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code for the agreements between the state and the 13 bargaining units, which are represented by Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1000, the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE) Locals 3, 39, and 501 (both Craft and Maintenance workers and Stationary Engineers), the California Association of Psychiatric Technicians (CAPT), and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME, Local 2620). More information about each of the affected bargaining units (1, 3, 4, 11 through 15, and 17 through 21) is available at our website. The administration has posted these agreements and summaries of the agreements and the administration’s fiscal estimates on its website. In addition, the unions have posted summaries on their respective websites, linked above.

The state’s cost to provide employee compensation is one of the larger components of the state’s General Fund budget. In 2015‑16, about 12 percent (more than $13 billion) of the state’s $115 billion of General Fund expenditures paid for state employee salaries and benefits. If approved by the Legislature and affected employees, the agreements now before the Legislature would direct state employee compensation policies and costs for years to come. The timing of these agreements gives the Legislature the opportunity to consider the administration’s employee compensation proposals for a majority of the state workforce.

The 13 proposed agreements include changes to the state’s retiree health benefits that largely are similar to the plans the Governor proposed in six agreements the Legislature has ratified since 2015 (affecting Bargaining Units 2, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12). (The Unit 12 agreement that the Legislature ratified last year subsequently was rejected by affected employees. The administration has submitted to the Legislature a new Unit 12 agreement that is included in this analysis.) If the proposed agreements are ratified by the Legislature and affected employees, the state will have adopted a plan to address its large unfunded retiree health liabilities over the next few decades—through prefunding and reducing benefits for future employees—for much of the state workforce. These actions would lower state retiree health costs significantly over the long term. In order to reach these agreements, however, the Governor agreed to propose various pay and benefit increases for affected employees in the near term. These proposed pay and benefit increases—along with the state contributions to match employee payments to a retiree health funding account—would be a significant new budgetary commitment for the state with both near- and long-term effects on state obligations.

Back to the TopCommon Provisions of Proposed Agreements

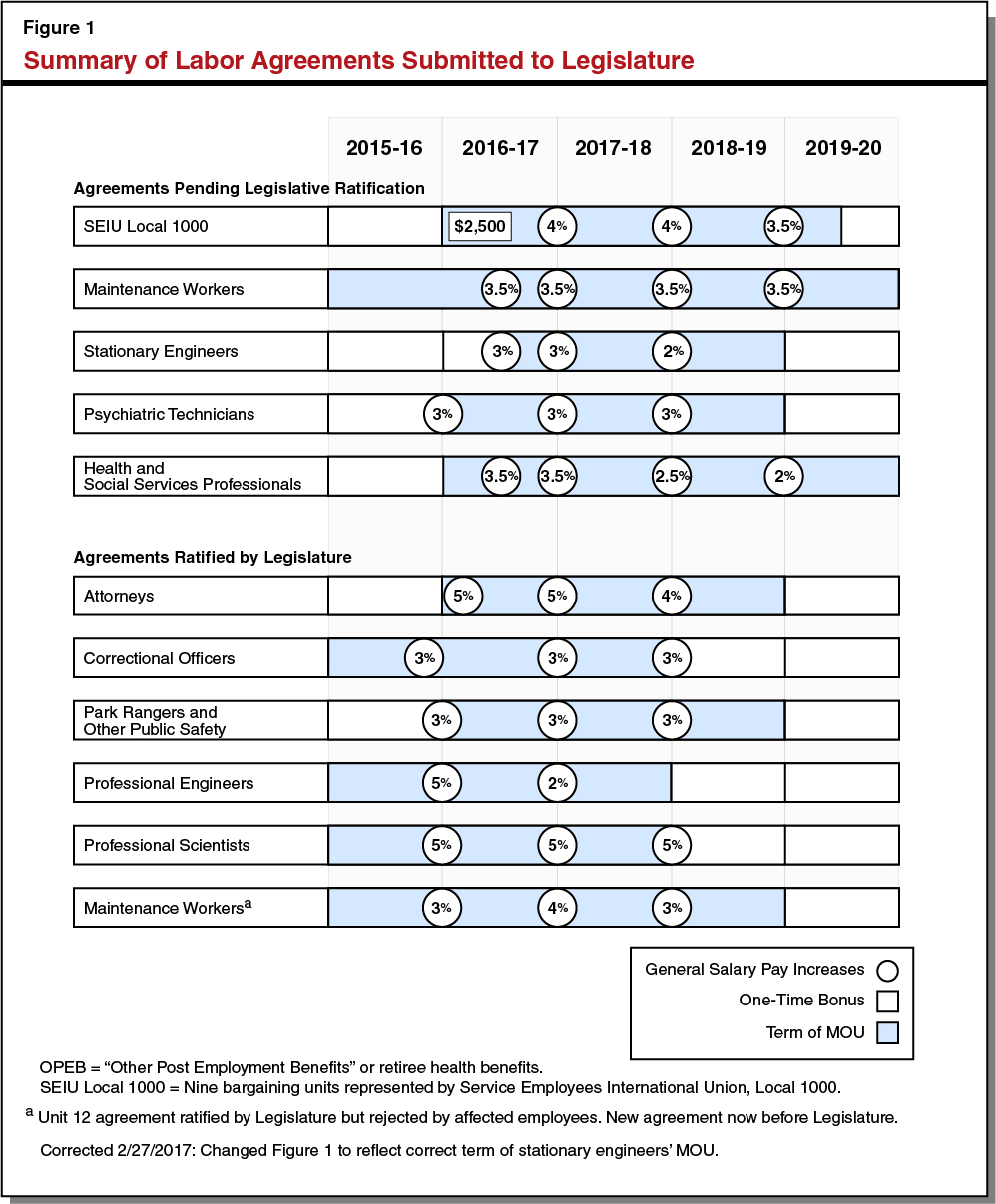

Long Duration. Since we started analyzing proposed labor agreements about a decade ago, most of the agreements the Legislature has ratified have had terms of about two years. (In general, these agreements were consistent with our 2007 recommendation to the Legislature not to approve any proposed labor agreements with a term of more than two years.) The proposed agreements have notably longer terms—ranging from between three years and five years in duration. The 13 proposed agreements tend to end about one year later than the agreements the Legislature has ratified since 2015. These differences can be seen in Figure 1.

Pay

Large Salary Increases for All Employees. Each agreement provides a number of General Salary Increases (GSIs) to all employees in the respective bargaining unit. These pay increases also increase the state’s costs for salary-driven benefits like pensions, Social Security, and Medicare. As Figure 1 shows, the size and frequency of these pay increases vary by bargaining unit. Over the course of the agreements, most employees in these bargaining units would receive a total compounded pay increase of about 12 percent. These agreements provide larger compounded GSIs over the course of the agreements than the average 10 percent provided by the agreements already ratified by the Legislature. (The largest group of employees with an existing agreement—correctional officers—received GSIs totaling about 9 percent over their agreement period.) In addition to compounded pay increases of 12 percent from GSIs over the course of the agreements, the SEIU agreements provide its members a sizeable one-time bonus of $2,500 upon ratification of the agreements. This bonus is subject to Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes but does not affect state costs towards employee pension benefits. For the average SEIU Local 1000 member, this bonus constitutes about 4 percent of pay. However, because SEIU represents a diverse group of state employees, the relative value of this bonus varies significantly across SEIU bargaining units such that it constitutes more than 8 percent of pay for the lowest-paid workers in these units but less than 2.5 percent for the highest-paid workers.

Additional Salary Increases for Many Employees. The agreements provide “special salary adjustments” (SSAs) to specified classifications that affect more than 20 percent of the employees covered by the 13 agreements. These SSAs increase affected employees’ pay by between 2 percent and 15 percent on top of what is provided by the GSIs. Using a weighted average, the agreements provide employees who receive SSAs a total compounded pay increase of about 17 percent over the course of the agreements—about 5 percent more than those employees not receiving SSAs. Figure 2 shows the weighted average pay increases—GSIs and SSAs—provided in the 13 proposed agreements and the agreements the Legislature has already ratified.

Figure 2

Compounded Pay Increases Vary by Bargaining Unit

Weighted Average Pay Increases After Accounting for Special Salary Adjustments and General Salary Increases

|

Unit |

Average Base Pay |

Compounded Pay Increase |

|

Agreements Pending Legislative Ratification |

||

|

1 |

$62,000 |

13.0% |

|

3 |

84,000 |

13.5 |

|

4 |

39,000 |

12.3 |

|

11 |

56,000 |

12.4 |

|

12 |

50,000 |

16.5 |

|

13 |

66,000 |

14.6 |

|

14 |

52,000 |

11.9 |

|

15 |

33,000 |

13.5 |

|

17 |

97,000 |

12.0 |

|

18 |

58,000 |

9.6 |

|

19 |

83,000 |

12.5 |

|

20 |

48,000 |

17.5 |

|

21 |

82,000 |

12.2 |

|

Agreements Ratified by Legislature |

||

|

2 |

108,000 |

14.7 |

|

6 |

76,000 |

9.3 |

|

7 |

60,000 |

10.0 |

|

9 |

99,000 |

7.1 |

|

10 |

69,000 |

15.8 |

|

12b |

50,000 |

11.4 |

|

Statewide Weighted Averagea |

60,000 |

12.1 |

|

aExcludes Units 5, 8, and 16. bUnit 12 agreement rejected by employees. |

||

Additional Pay Increases for Some That Do Not Affect Pension Benefits. The proposed agreements provide some employees pay increases through specified payments intended to compensate employees for specific job-related skills, activities, work conditions, certifications, clothing, or other job-specific criteria. Unlike GSIs or SSAs, these pay increases are not considered part of an employee’s base pay and do not increase state pension costs. However, in most cases, the state and affected employees pay Social Security and Medicare taxes on these payments.

Leave Cash Outs. To the extent authorized by department directors, the proposed agreements allow all affected employees to cash out up to 80 hours of vacation or annual leave each year. This is an increase in the amount of leave employees may cash out for all affected bargaining units. Specifically, under current agreements, Units 18, 19, and SEIU members may not cash out any leave but members of Units 12 and 13 may cash out up to 20 hours of leave each year. These leave cash outs are subject to Medicare and Social Security payroll taxes but do not affect employees’ pension benefits. The administration assumes that departments will not receive additional budgetary resources to pay for these cash outs.

Travel and Business Reimbursements. State employees are reimbursed for specified costs incurred while traveling and doing business for the state. In the past, these reimbursement rates typically have been established in memoranda of understanding (MOUs) for rank-and-file employees. The administration has indicated that it wants to remove reimbursement rates from future MOUs and establish a consistent statewide reimbursement policy through policy memos (see PML 2006‑021 and PML 2016‑010). While all of the agreements provide reimbursement rates that appear consistent with existing policy memos, most of the agreements do not defer to the policy memos to establish the rates—only the Unit 13 and 18 agreements defer to the two memos.

Health Benefits

End Dependent Vesting Period. The current MOUs require new employees to work with the state for two years before receiving the state’s full contribution towards health coverage for the employees’ enrolled dependents. Specifically, the share of the state’s contribution to dependent health coverage increases over time so that the state pays (1) 50 percent of this benefit in the first year, (2) 75 percent of this benefit in the second year, and (3) the full benefit after the employee has worked two years with the state. The proposed agreements eliminate this vesting period so that the state pays the full contribution towards health coverage of new hires’ enrolled dependents. The administration assumes that departments will not receive augmentations to their budgets to pay for these increased costs.

Retiree Health Benefits and Prefunding

Current Benefits and Funding. Until recently, like most governments in the U.S., California did not fund health and dental benefits for its retirees during their working careers in state government. This has resulted in large unfunded state liabilities for the benefits. The state now pays for retiree health and dental benefits on an expensive “pay-as-you-go” basis. This means that later generations pay for benefits of past public employees.

After most current employees retire, the maximum state contribution to their health benefits covers 100 percent of an average of CalPERS premium costs plus 90 percent of average CalPERS premium costs for enrolled family members. This maximum contribution is sometimes referred to as the “100/90 formula.” In 2017, the 100/90 formula entitles retirees to a maximum state contribution towards their health care of $707 per month for single coverage. Most state employees receive 50 percent of the maximum contribution from the state if they retire with 10 years of service, with this amount growing each year until it reaches 100 percent of the maximum contribution if they retire after 20 or more years. The state contribution for the typical retiree who is enrolled in Medicare is sufficient to pay the monthly CalPERS Medicare health plan premium and Medicare Part B premium costs—$134 per month for the typical Medicare enrollee.

Proposed Retiree Benefit Changes. The proposed agreements change future retiree health benefits for employees first hired in 2017 and thereafter. (In the case of SEIU Local 1000, the agreements themselves do not reduce the benefit; however, the administration informed us that it expected the benefit to be reduced through the ratifying legislation.) Unlike the benefit received by current retirees, retired future employees will receive a significantly smaller amount of money from the state to pay for healthcare. Specifically, (1) the maximum benefit available to retirees not eligible for Medicare will be up to 80 percent of the weighted average premium cost of CalPERS health plans available to active employees and (2) the maximum benefit available to employees eligible for Medicare will be up to 80 percent of the weighted average premium cost of CalPERS Medicare plans and retirees will be responsible for paying the full Medicare Part B premium. Using current premiums for comparison, whereas a typical current retiree enrolled in Medicare has no premium costs, a retired future employee enrolled in Medicare would be responsible for paying about $1,800 per year to pay Medicare Part B premiums and CalPERS Medicare plan premiums. This is more than 5 percent of the average pension received by retired state employees in 2014‑15.

Proposed Funding Changes. The agreements institute a new arrangement to begin to address unfunded retiree health benefits for employees. While the administration’s plan seems to be to keep making pay-as-you-go benefit payments for many years, the new arrangement would begin to fund “normal costs” each year for the future retiree health benefits earned by today’s workers. The agreements establish a “goal” that employees and the state each regularly contribute half of the normal costs by a specified date. (This date typically is at the end of the term of the agreement; however, in the case of SEIU, the date at which this occurs is July 1, 2020—six months after the proposed agreement expires.) The agreements deposit these payments in dedicated accounts in an invested trust fund managed by CalPERS. In the case of Units 12, 13, 18, and 19, each bargaining unit has a unique account; however, SEIU’s agreements establish a single account for all nine bargaining units to share. These accounts would generate earnings and gradually reduce unfunded liabilities over the next three decades or so.

Unlike pension benefits, the state’s retiree health benefit is unrelated to a person’s income either during his or her career or in retirement. Because the state’s retiree health benefit is the same for an employee earning $30,000 as it is for an employee earning $100,000, the amount of money needed to prefund the benefit represents a larger share of a lower-income worker’s salary. Figure 3 shows what one-half of the normal costs attributable to each bargaining unit represents as a percent of pay for each bargaining unit based on data from the most recent state actuarial valuation for “other post-employment benefits” (also known as OPEB). The figure refers to this as the “actuarially determined” employee share of normal costs. While we understand that CalPERS soon will reconsider the 7.3 percent investment return (discount) rate used in this valuation, the data in Figure 3 does, as far as we can tell, represent the normal costs known to the administration as it started bargaining. The “bargained” employee share of normal costs reflects the contribution rates to prefund retiree health benefits established by the agreements. The figure illustrates that—by sharing retiree health liabilities across the nine bargaining units—the SEIU agreements require higher paid employees (like registered nurses in Unit 17) to pay more than half of actuarially determined normal costs and lower paid employees (like office workers in Unit 4) to pay less than half of actuarially determined normal costs. Depending on actuarial assumptions and payroll growth in the future, the actuarially required contributions in 2018-19 and beyond to fully fund these benefits may be different than reflected in the figure.

Figure 3

SEIU Local 1000 Agreements Pool OPEB Normal Costs

|

Unit |

Average Base Pay |

Employee Share of Normal Costs |

|

|

Actuarially Determineda |

Bargainedb |

||

|

Units Represented by SEIU Local 1000 |

|||

|

17 |

$97,000 |

2.8% |

3.5% |

|

3 |

84,000 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

|

21 |

82,000 |

2.6 |

3.5 |

|

1 |

62,000 |

2.9 |

3.5 |

|

11 |

56,000 |

3.7 |

3.5 |

|

14 |

52,000 |

3.9 |

3.5 |

|

20 |

48,000 |

5.6 |

3.5 |

|

4 |

39,000 |

5.4 |

3.5 |

|

15 |

33,000 |

7.0 |

3.5 |

|

Other Units |

|||

|

2 |

108,000 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

9 |

99,000 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

19 |

83,000 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

6 |

76,000 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

10 |

69,000 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

|

13 |

66,000 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

|

7 |

60,000 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

18 |

58,000 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

12c |

50,000 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

|

Statewide Weighted Averaged |

60,000 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

|

a"Actuarially determined" contribution reflects one-half of 2015-16 normal costs as a percent of 2015-16 pay. Normal costs based on "full funding policy" scenario reported in state OPEB valuation, assuming a 7.3 percent investment return discount rate. Pay estimated by LAO applying general salary increases to 2014-15 pensionable compensation reported by administration. The normal costs as a percent of pay actuarially required in 2018-19 and beyond to fully fund these benefits may be different than reflected in this figure depending on actuarial assumptions and payroll growth. bEmployee contributions to prefund retiree health benefits established in proposed and ratified agreements. cProposed Unit 12 agreement. dExcludes Units 5, 8, and 16. OPEB = “Other Post Employment Benefits” or retiree health benefits. |

|||

Unit-Specific Issues

Units 3, 12, 13, and 18: Health Benefits

Increase State Contribution to Health Premiums. The state contributes a flat dollar amount to health benefits for workers in Units 3, 12, 13, and 18. (The state pays a specified percentage of premium costs for the other bargaining units, thereby allowing the state’s contributions to change automatically as premiums change.) This flat dollar contribution amount was last adjusted in 2015 for Unit 12 members and 2016 for Units 3, 13, and 18 members. The proposed agreements adjust the amount of money the state pays towards these benefits each January for the duration of each agreement. For the term of the agreements, the state’s contribution would be adjusted so that the state pays up to 80 percent of an average of CalPERS premium costs plus up to 80 percent of average CalPERS premium costs for enrolled family members—referred to as the “80/80 formula.” The state’s contributions would not be increased after the agreements expire unless provided in a future agreement.

Unit 12: Rejected Agreement vs. Proposed Agreement

Last year, the Legislature ratified a tentative agreement between the state and Unit 12. This agreement did not go into effect, however, because it subsequently was rejected by Unit 12 members. Our analysis of the rejected agreement is posted on our website.

Proposed Agreement Is Longer, Provides More Pay Increases. As Figure 1 shows for maintenance workers, relative to the agreement ratified by the Legislature last year, the proposed agreement would (1) be in effect for an additional year, through 2019‑20 and (2) provide more pay increases to all Unit 12 members, providing a 14.8 percent compounded pay increase over the term of the contract. Also, in addition to the SSAs for about 13 percent of Unit 12 members established under the rejected agreement, the proposed agreement includes additional SSAs for about 5 percent of Unit 12 members. Specifically, the agreement would provide tree maintenance workers, steel painters, plumbers, and locksmiths a 2 percent pay increase on July 1, 2017, a 2 percent pay increase on July 1, 2018, and a 1 percent pay increase on July 1, 2019. In addition to these pay increases, the proposed agreement specifies that the state will maintain its share of employee health premiums to account for any changes in premium costs through 2020—one year longer than agreed to in the rejected agreement.

Units 17, 18, and 20: Mandatory Overtime

Goal to Reduce—or Even Eliminate—Use of Mandatory Overtime. Medical professionals—including nurses, vocational nurses, and psychiatric technicians—who work at state institutions often are required to work overtime. An April 2016 report from the Little Hoover Commission found that the high use of overtime among these staff creates recruitment and retention issues and raises concerns about the quality of care provided to patients from staff who work multiple shifts. In the past, the Legislature has passed at least two measures related to the issue of reducing the use of mandatory overtime among state medical professionals. In his veto message for these past measures, the Governor indicated that it is an issue that should be resolved through the collective bargaining process. The agreements with Units 17, 18, and 20 include language to establish task forces and develop plans to eliminate or at least reduce the use of mandatory overtime by 2018 (in the case of Unit 18) or 2019 (in the case of Units 17 and 20). In the case of the Unit 18 agreement, the state and CAPT agree to “the fact that mandatory overtime is not an effective staffing tool.”

Units 1, 4, 12, 13, 14, 15, 18, and 20: Overtime Meal Allowances

More Money to Purchase Meals. The agreements increase the amount of money that certain employees receive to purchase meals when working overtime by between $0.50 and $2.00 to an $8.00 meal allowance. All Unit 18 employees would be eligible to receive the allowance during overtime work. For the other seven units, only employees who work overtime at California Departments of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and Transportation (Caltrans) would be eligible to receive the allowance. In the case of Units 12, 13, and 18, the administration assumes that the overtime meal allowance will increase CDCR costs by about $1,400 each year and will increase Caltrans’ costs by more than $9,000 each year. The administration believes that the departments can pay for these costs using existing budget resources. In the case of the units represented by SEIU, the administration estimates that CDCR costs will increase by about $36,000 and that the department needs additional funds to pay for this cost.

SEIU: Overtime

Change How Overtime Is Calculated. Chapter 4 of the 2009‑10 Third Extraordinary Session (SBX3 8, Ducheny) specifies that any paid or unpaid leave “shall not be considered as time worked by the employee for the purpose of computing cash compensation for overtime or compensating time off for overtime.” The law specifies that any labor agreement ratified after February 1, 2009 that is in conflict with this provision will be the controlling policy without the need to change statute. The proposed SEIU agreement would alter the administration of this law by allowing time off from work for jury leave, military training leave, and subpoenaed witness leave to count as “time worked” for purposes of calculating overtime pay in a week. The administration estimates that this will increase annual state costs by about $800,000. The Legislature has ratified other agreements that establish exceptions to the statewide rule of calculating overtime, including the Bargaining Unit 6 agreement that the Legislature ratified in 2016 and the current Unit 18 agreement (provisions that are retained in the proposed Unit 18 agreement that allow leave time to be counted as time worked in weeks when employees are required to work mandatory overtime).

Back to the TopFiscal Effects

Significant New Budgetary Commitment. As Figure 4 shows, the administration estimates that these 13 agreements would increase annual state costs by nearly $2 billion by 2020‑21. About one-half of these costs would be paid from the state’s General Fund. We think the actual annual costs of these agreements will be higher than the administration estimates. In particular, the administration’s estimates do not take into consideration the effect that the increases to employee base pay will have on overtime payments. Some of the employees in these bargaining units work significant overtime. The higher salary levels provided by these agreements could increase annual state overtime costs by tens of millions of dollars—likely not more than $50 million—by 2020‑21. In addition, for reasons we discuss below, we think the pay increases provided by the agreements could lead to additional direct cost increases—perhaps tens of millions of dollars or more annually by 2020‑21—related to rising pension costs. In total, we think it is possible that actual annual state costs by 2020‑21 could be more than $100 million above what the administration estimates.

Figure 4

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates of Proposed Labor Agreementsa

(In Millions)

|

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

2019-20 |

2020-21 |

||||||||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|||||

|

Pay increases |

$146 |

$310 |

$287 |

$573 |

$476 |

$983 |

$630 |

$1,339 |

$630 |

$1,345 |

||||

|

Leave cash outb |

139 |

290 |

145 |

301 |

150 |

313 |

155 |

323 |

155 |

323 |

||||

|

Prefunding retiree health benefits |

— |

— |

11 |

17 |

49 |

98 |

87 |

178 |

118 |

251 |

||||

|

Health benefits |

2 |

6 |

10 |

25 |

18 |

37 |

22 |

47 |

24 |

50 |

||||

|

Overtime-meal allowance and other costsb |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

||||

|

Travel and Business Reimbursementsb |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

||||

|

Totals |

$288 |

$607 |

$453 |

$917 |

$693 |

$1,431 |

$894 |

$1,887 |

$927 |

$1,969 |

||||

|

aEstimated full-year effects of proposed labor agreements between the state and Bargaining Units 1, 3, 4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, and 21. bThe administration assumes some or all of these costs will be paid with existing departmental resources. Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding. Less than $50,000 costs appear as “0.” |

||||||||||||||

Likely Indirect Costs to Prevent Future Compaction. When rank-and-file pay increases faster than managerial pay, “salary compaction” can result. Salary compaction can be a problem when the differential between management and rank-and-file is too small to create an incentive for employees to accept the additional responsibilities of being a manager. Consequently, the administration often provides compensation increases to managerial employees that are similar to those received by rank-and-file employees. While the administration has significant authority to establish compensation levels for employees excluded from the collective bargaining process, these compensation levels are subject to legislative review. In 2016‑17, the administration provided all managers and supervisors a 3 percent GSI, including those who supervise rank-and-file employees represented by these 13 units who did not receive a GSI in 2016‑17. To prevent any compaction issues in 2017‑18 and beyond, the administration likely will propose pay increases for excluded employees that are comparable to the pay increases received by rank-and-file employees under these agreements, increasing annual state costs by more than $200 million by 2020‑21.

Agreements Could Be in Effect During Next Economic Downturn. The state has a revenue structure that depends on many volatile and unpredictable economic conditions, including fluctuations in the stock market. The U.S. economy currently is in one of the longest periods of economic expansion in the country’s history. It is difficult to predict with any level of certainty the timing, duration, or severity of the next economic downturn. However, it is reasonable to suggest that the next downturn could occur within the next few years. These agreements provide pay increases and other provisions that increase state costs through 2020‑21. Employees will expect to receive the pay increases provided by the agreements, regardless of the condition of state revenues during the terms of the agreements. While the Legislature has the authority to set employee compensation to any level in any budget year, these agreements will make any action in response to fiscal constraints to reduce employee compensation below what is provided by the agreements very difficult.

Salary-Driven Benefits

Pay Raises Increase Other State Costs. The state pays for employee pension, Social Security, and Medicare benefits as a percentage of pay. Accordingly, any pay increases also increase the state’s costs for these benefits. The costs resulting from the proposed pay increases that are displayed in Figure 4 reflect the costs of the salary and any increased pension, Social Security, or Medicare costs associated with the salary increases. The estimated pension costs are based on current assumptions. In 2016‑17, the state pays 26.7 percent of pay towards pension benefits and 7.65 percent towards Social Security and Medicare for most of the employees affected by these agreements. This means that for every $1 salary increase for state employees, the state’s costs increase by $1.34.

Agreements Fund Retiree Health Benefits as a Salary-Driven Benefit. Although retiree health benefits historically have had no bearing on pay, the agreements establish the state’s costs to prefund retiree health benefits as a percentage of pay. This will increase state costs of future $1 salary increases by between $0.03 and $0.05.

Pension Benefits

New CalPERS Discount Rate Will Increase Pension Contributions . . . CalPERS pensions are funded from three sources: investment gains, employer contributions, and employee contributions. CalPERS reports that about two-thirds of benefit payments are paid from past investment gains. CalPERS expects investment returns over the next decade to be lower than past returns. At its December 2016 meeting, the CalPERS board voted to change a key assumption used in calculating how much money employers and employees must contribute to the pension system each year. Specifically, the board voted to lower the discount rate from 7.5 percent to 7.0 percent over the next three years. This lower discount rate means that CalPERS calculations of plan assets and liabilities will assume investments will have lower returns. By assuming less money comes into the system through investment gains, the state will be required to contribute more money to pay for higher normal costs and a larger unfunded liability.

. . . Making Proposed Pay Increases More Costly . . . Based on risk analyses reported in the 2015 State Actuarial Valuation, the lower discount rate could result in the state’s contribution to CalPERS rising by more than 5 percent of pay for the bulk of these employees once the new discount rate is fully implemented. Because the administration’s fiscal estimates do not take into account this rate increase, the cost to provide the proposed pay increases could be tens of millions of dollars more than what is presented in the figure.

. . . And Creating Pressure for Even Higher Salaries in Future. The Pension Reform Act of 2013 (PEPRA) created a standard that all state employees pay one-half of normal costs for their pension benefits. Today, the contributions paid by most state employees meet this standard. Contribution levels for state employees are established in labor agreements and statute. The lower discount rate will increase the normal costs for CalPERS pensions. If the proposed agreements are ratified, the increased normal costs likely will be an issue of collective bargaining after these agreements expire in a few years. Historically, when the state requires employees to contribute additional money to prefund retirement benefits—either pension or retiree health benefits—the state has agreed to provide pay increases to offset the increased employee contributions. To the extent that the lower discount rate increases pension normal costs to the point that employees must contribute more money in order to maintain the standard established by PEPRA, the state will face pressure to increase salaries above what might otherwise have been the case. Any salary increases also will increase salary-driven benefit costs, including the amount of money the state and employees contribute to prefund retiree health benefits under the proposal.

High Level of Pay Increases Could Increase State Pension Costs Even More. In addition to the discount rate, CalPERS includes many other actuarial assumptions in its calculations to determine the state’s costs, including assumptions about how quickly payroll grows. Payroll is affected by (1) the number of people employed by the state and (2) the amount of money these employees earn. CalPERS assumes that payroll will grow each year by 3 percent. When payroll grows faster than 3 percent, the state’s pension unfunded liabilities grow, resulting in higher annual costs for the state to pay off a larger unfunded liability. To the extent that the pay increases provided by these agreements result in payroll growing faster than 3 percent each year, the state likely will be required to contribute more money to CalPERS than is assumed in Figure 3 within a few years. For example, of the estimated $602 million increase CalPERS estimated for state contributions in 2016‑17, $109 million was attributed to payroll growing faster than assumed in 2014‑15. CalPERS found that payroll had increased by 6 percent due to an increase in the number of state employees participating in CalPERS and individual salary increases.

Insisting on Employee OPEB Contributions May Increase State Costs. In a 2015 report, we noted that the Governor’s approach of requiring employee—rather than just employer—contributions to fund retiree health benefits would create pressure for the state to provide offsetting pay increases. It is now clear that this pressure affected the recent round of state employee negotiations. Employee pay increases now proposed likely are larger than they would be if the administration had not insisted on employee contributions to retiree health benefits. We also noted in 2015 that higher pay increases of this type drive up state pension costs. As such, it will probably end up costing the state more—including pay and pension costs—to share retiree health costs with employees than it would have costed to pay for retiree health with just an employer contribution.

Pay

Agreements Propose Large Number of Classification-Specific Pay Increases. Salaries for state employees are determined by their classification. A GSI provides pay increases to employees in every classification represented by a particular bargaining unit. An SSA is provided to specified classifications. Typically, SSAs are intended to address a recruitment and retention issue that management or labor has identified whereas GSIs are more akin to a cost-of-living-adjustment. It is common for bargaining agreements to include SSAs for a few of the classifications represented by the bargaining unit. These agreements seems to include a high number of SSAs.

Some Proposed Classification-Specific Pay Increases Supported by CalHR Market Analysis . . . CalHR periodically conducts salary surveys to compare—to the extent possible—state employee compensation with compensation earned by workers in similar occupations employed by the private sector and federal and local government. This report is an imperfect tool in comparing compensation because (1) some government jobs do not have clear private sector equivalents and (2) the data are point in time and provide no indication of potential future changes in compensation across employers. Accordingly, this report serves as one of many tools—including vacancy reports, management feedback, and joint management-labor committees—CalHR uses to determine recruitment and retention needs in state government as it prepares for collective bargaining. CalHR reviewed classifications represented by (1) Units 13, 18, 19, and SEIU as part of the 2014 California State Employee Total Compensation Report and (2) Unit 12 as part of the 2013 California State Employee Total Compensation Report. Figure 5 lists the occupations that include at least one classification proposed to receive an SSA under the proposed agreements that were identified by CalHR as being compensated “below market” levels. In all of the cases shown in the figure, the total pay increase provided by the agreements—through SSAs and GSIs—exceed the pay gap between the state and other employers identified by CalHR. It is important to note, however, that this does not necessarily mean that the pay gap would be closed by the end of the agreements. Without knowing the likelihood of other employers providing pay increases to employees in similar occupations over the next few years, it is difficult to predict what effect the pay increases provided by these agreements would have on the state’s ability to recruit and retain qualified employees for these jobs.

Figure 5

Agreements Provide SSAs to Some Classifications in Occupations With Compensation Below Market Averages

Occupations Listed Include at Least One Classification Proposed to Receive an SSA

|

Occupation |

State |

Percent Below |

Proposed Pay Increases |

|

|

Compounded SSA |

Compounded Total |

|||

|

Management Analysts |

1 |

-24.6% |

15.0% |

28.7% |

|

Tax Examiners and Collectors, and Revenue Agents |

1 |

-9.3 |

5.0 |

17.5 |

|

Medical and Clinical Laboratory Technicians |

11 |

-11.2 |

5.0 |

17.5 |

|

Stationary Engineers and Boiler Operators |

13 |

-8.4 |

6.1 |

14.8 |

|

Dietitians and Nutritionists |

19 |

-5 |

5.0 |

17.6 |

|

SSA = Special Salary Adjustment proposed by agreement. Note: Calculations performed and reported by Department of Human Resources in California State Employee Total Compensation Report. Occupations listed include at least one state classification that would receive an SSA under proposed agreements. |

||||

. . . Other Pay Increases Are Not Supported by CalHR Market Analysis. The CalHR compensation reports indicate that there are a number of state classifications that are compensated above the average compensation of other employees in similar occupations. Figure 6 lists the occupation groups that include at least one classification proposed to receive an SSA under the proposed agreements that were identified as being compensated above market levels. The administration explains that these SSAs are justified for recruitment and retention purposes. We highlight two of these examples below.

Custodians. In the case of custodians, CalHR indicates that the Department of General Services (DGS) has found it difficult to find candidates who can clear the background check required for state custodians. The administration hopes that the SSA would make the classification more appealing to qualified individuals.

Psychiatric Technicians and Licensed Vocational Nurses. Psychiatric technicians and licensed vocational nurses have similar jobs—sometimes at the same facility—with similar education and licensing requirements. However, licensed vocational nurse classifications tend to be paid less than psychiatric technician classifications. The SSAs for licensed vocational nurses are meant to bring them closer to the level of pay received by psychiatric technicians. The SSA provided to psychiatric technicians only applies to senior and instructor psychiatric technicians (about 10 percent of the occupation) and is intended to create incentive for employees to take on the greater responsibility associated with these classifications.

Due to the limitations of the compensation report and limited time of our review, we cannot independently confirm that the pay increases for the occupations listed in the figure would resolve any possible recruitment and retention issues that exist today. The extent to which the compensation gap between the state and other employers widens as a result of these pay increases depends on future decisions made by other employers to provide pay increases to their employees.

Figure 6

Agreements Provide SSAs to Some Classifications in Occupations With Compensation Above Market Average

Occupations Listed Include at Least One Classification Proposed to Receive an SSA

|

Occupation |

State |

Percent Above |

Proposed Pay Increases |

|

|

Compounded SSA |

Compounded Total |

|||

|

Accountants and Auditors |

1 |

0.5% |

5% |

17.5% |

|

Claims Adjusters, Examiners, and Investigators |

1 |

2.9 |

5 |

17.5 |

|

Office Clerks, General |

4 |

16.0 |

2 |

14.2 |

|

Water and Wastewater Treatment Plant and Systems Operators |

13 |

15.0 |

6 |

14.8 |

|

Janitors and Cleaners, Except Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners |

15 |

14.8 |

3 |

15.3 |

|

Registered Nurses |

17 |

11.8 |

5 |

17.5 |

|

Psychiatric Technicians |

18 |

35.6 |

3 |

9.6 |

|

Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses |

20 |

17.2 |

11 |

24.5 |

|

Note: Calculations performed and reported by Department of Human Resources in California State Employee Total Compensation Report. Occupations listed include at least one state classification that would receive an SSA under proposed agreements. SSA = Special Salary Adjustment proposed by agreement. |

||||

Certain Classifications Identified as Paid Below Market Not Proposed to Receive Pay Increases. SEIU represents most of the state’s information technology (IT) professionals, including computer programmers. The state historically has had difficulties recruiting and retaining IT professionals. This has contributed to difficulties in managing state IT projects. Past studies—including the 2014 CalHR compensation report—have supported the notion that the largest hurdles to recruiting and retaining these types of employees is the structure of the classifications and below market compensation. The agreements do not provide SSAs for any of the IT professional classifications. It is our understanding that this omission was intentional because the state currently is reviewing IT classifications as part of its ongoing Civil Service Improvement Project.

Retiree Health Benefits

Timing Creates Legal Uncertainty. All of the 13 bargaining units’ current agreements have expired. State law specifies that the terms of an expired labor agreement generally live on until a subsequent agreement is ratified by both the Legislature and affected employees. The expired agreements provide employees more generous retiree health benefits than are provided by the proposed agreements. The proposed agreements specify that employees hired on or after January 1, 2017 are subject to the less generous retiree health benefits. SEIU is scheduled to conclude its ratification vote on January 17, 2017. (We are not sure when the other unions will conclude their votes.) Assuming the Legislature were to ratify the agreements before this date, an employee hired between January 1 and January 17 would be hired with the current contract being the law of the land. One issue that we think should be considered is what—if any—legal rights an employee hired on January 3, 2017 has to the current retiree health benefit. The administration has provided no detailed analysis of any of the many complex legal issues that the proposed retiree health plan would bring. However, the administration indicates that it does not think there would be any legal issues and that the new employees would be subject to the new benefit.

Contribution Rates Likely Will Need to Be Changed in Future. The agreements establish state (employer) and employee contributions to prefund retiree health benefits as a percent of pay. The normal costs to prefund retiree health benefits grow each year to account for growing health costs. Health costs historically have grown at a rate faster than the rate of inflation in the broader economy and faster than state employee salaries historically have grown. In addition, CalPERS’ expectation that investment returns over the next ten years will be less than in prior years suggests that the discount rate of 7.3 percent used to calculate normal costs under a “full funding” scenario might need to be lowered, thereby increasing normal costs. In order to maintain the state’s policy to set aside the full normal costs, the state and employees likely will need to revisit—on a regular basis—the percent of pay specified in the agreements. Increases in the employee contribution likely will create pressure for future salary increases, resulting in higher pension and other salary-driven costs.

Mandatory Overtime

Potential Data Limitations Under Current Systems. The State Controller’s Office (SCO) maintains records of overtime usage across state government; however, SCO records do not distinguish between mandatory and voluntary overtime. These data—if maintained—are maintained at the departmental level. Often, the data are maintained at the facility (prison, state hospital, or veterans home) where an employee works. The agreements require specified departments to monitor and record mandatory overtime use at state facilities. Based on our past experience of requesting data of mandatory overtime use at state facilities, some institutions have better systems to track mandatory overtime usage than others.

Budgetary Implications of Ending Mandatory Overtime Not Clear. Significantly reducing or eliminating the use of mandatory overtime likely will require the state to hire additional staff. Once fully implemented, this likely would increase state costs by millions of dollars each year. In addition, it seems possible—based on our past experience of requesting data—that some facilities would need to upgrade their information technology to monitor and record the use of mandatory overtime. The potential high costs, combined with past legislative interest on the issue, makes this an issue that the Legislature likely will want to monitor closely.