LAO Contact

January 18, 2017

A Historical Review of Proposition 98

- Introduction

- Formulas

- True Ups

- Revenue and Program Shifts

- Major Controversies

- Impact on School Funding

- Lessons Learned

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Voters Approved Proposition 98 in 1988. Proposition 98, a measure on the November 1988 ballot, was intended to increase state funding for schools. The proponents of Proposition 98 argued that school funding at the time was too low and associated state budget decisions too political. Approved by 51 percent of voters, Proposition 98 added certain constitutional provisions setting forth rules for calculating a minimum annual funding level for K–14 education. The state commonly refers to this level as the minimum guarantee. Our report provides a historical review of the state’s more–than–quarter–century experience with Proposition 98.

A Tale of Complexity

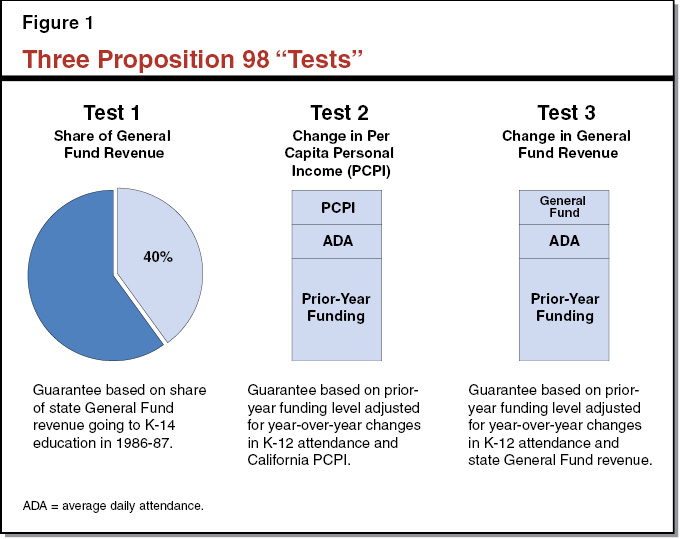

A Plethora of Tests and Rules Govern the Minimum Guarantee. Proposition 98 added two formulas or tests (Test 1 and Test 2) to the State Constitution. Test 1 links the minimum guarantee to a share of state General Fund revenue (about 40 percent), whereas Test 2 adjusts prior–year Proposition 98 funding for changes in student attendance and California per capita personal income. Under Proposition 98, the minimum guarantee is to be the higher of the Test 1 or Test 2 funding levels. In 1990, the state entered a recession and found the two original Proposition 98 formulas difficult to implement. In response, the Legislature placed Proposition 111 on the ballot. Approved by 52 percent of voters, Proposition 111 added various new school funding formulas to the Constitution. Most notably, Proposition 111 added Test 3, which allows the state to provide a lower level of funding than the Test 2 level when state revenue growth is relatively weak. Proposition 111 also added a formula known as “maintenance factor,” which requires the state to accelerate school funding in strong revenue years to compensate for the lower funding provided when Test 3 applies. Other formulas affecting the guarantee are intended to ensure that school funding is not reduced more quickly than the rest of the state budget during tight economic times or increased to unsustainably high levels during unusually strong economic times. Altogether, the minimum guarantee is now governed by eight interacting formulas and nearly a dozen different inputs.

State Has Made Myriad Adjustments to the Proposition 98 Calculations. Since 1988, barely a year has passed when the state has not adjusted the Proposition 98 calculations in some way. Twenty four times the state has taken revenue–related actions affecting the Proposition 98 calculations. These adjustments have involved excluding certain sales tax revenue that would otherwise affect the minimum guarantee, shifting property tax revenue to schools and community colleges to provide more state General Fund for the rest of the budget, shifting property tax revenue away from schools and community colleges to backfill local governments for the loss of other revenue streams, and counting certain Proposition 98 funds as loans. In addition to these adjustments, the state has shifted various programs into and out of the minimum guarantee. In some of these cases, the state adjusted the minimum guarantee up or down accordingly. In other cases, the program shift crowded out school funding (when shifted into the guarantee) or crowded out other state funding (when shifted out of the guarantee).

A Tale of Controversy

Proposition 98 Has Been Associated With Sundry Poison Pills, Lawsuits, Rulings, and Settlements. In certain cases, the state realized that some of the adjustments it was making to the Proposition 98 calculations might be challenged. In some of these cases, it adopted “poison pills” that set forth seemingly dire repercussions (including suspending the guarantee) if the state’s actions were challenged. In other instances, the state took no specific action to address potential challenges. In some cases, state actions ultimately were challenged, with the state sued five times over Proposition 98 issues. Four of these cases resulted in published court decisions, with the state prevailing in two of the four cases. In the other case, the parties reached a settlement prior to the superior court ruling.

Ongoing Debates Linger Over Still Unresolved Proposition 98 Issues. Despite the lawsuits and court rulings, some key Proposition 98 issues remain unresolved. Debates continue to exist regarding both when the state is to create new maintenance factor obligations and how the state is to make maintenance factor payments. Ongoing debates also exist regarding which programs should count toward the guarantee. Many examples exist of the state supporting certain programs with Proposition 98 funds but very similar programs with non–Proposition 98 funds. In some cases, programs have been funded from one source some years and the other source in other years. No court ruling has definitively settled or clarified these issues.

A Tale of Caution

No Evidence School Funding Is Higher as a Result of the Formulas. Although no one knows for certain how much funding the state would have provided schools in the absence of Proposition 98, we use various methods to assess how schools fared over the 1988–89 through 2014–15 period. One method compares actual Proposition 98 funding each year with a simulated level that takes the 1988–89 school funding level and increases it each year for student attendance and inflation. We also compare growth in Proposition 98 funding with growth in the rest of the state General Fund budget, as well as growth in the entire state budget (General Fund and special funds combined). Lastly, we compare K–12 spending per pupil in California with the rest of the country. The results are similar across the four methods. School funding grows neither notably more nor less than the comparison levels.

State’s Experience Suggests Serious Caution in Adopting More Budget Formulas. In reviewing the state’s experience with Proposition 98, we think the formulas repeatedly have shown that they are unable to address real world developments. So many adjustments to the formulas, undertaken so frequently, suggests that even a complex set of eight interacting formulas could not foresee or respond well to the salient budget issues of the day. The formulas also have muddled the budget process, requiring legislators to dedicate considerable time to understanding a plethora of formulas and rules, while leaving less time for legislators to focus on the education system’s overall effectiveness and efficiency. Perhaps most notably, the state has no clear evidence that school funding is higher today or school funding decisions are less political today than they would have been absent the formulas. All these factors suggest the state should be extremely cautious about adopting new budget formulas in the future.

Introduction

Since 1988, Proposition 98 has been constitutionally governing the amount of funding provided to public schools and community colleges in California. This report uses data from 1988 through 2015 to review and analyze the impact of Proposition 98. The report has six parts. The first part describes the formulas the state uses to calculate the annual Proposition 98 funding requirement. The second part explains how the state “trues up” when the annual Proposition 98 funding requirement rises or falls during the year. The third part traces the many revenue and program shifts the state has made over the years affecting Proposition 98 calculations. The fourth part covers key controversies surrounding these calculations. The fifth part analyzes the impact of Proposition 98 on K–12 funding, and the final part gleans some lessons from the state’s more–than–quarter–century experience with Proposition 98.

Back to the TopFormulas

Below, we provide background on the ballot measures that established constitutional funding formulas for K–14 education, the rules used for determining the minimum funding requirement, and related constitutional and statutory funding provisions.

Three Ballot Measures

Proposition 98 Created the “Minimum Guarantee.” Approved by 51 percent of voters in November 1988, Proposition 98 amended Section 8 of Article XVI of the California Constitution. Specifically, Proposition 98 added constitutional provisions setting forth rules for calculating a minimum annual funding level for K–14 education. The state commonly refers to this calculated funding level as the minimum guarantee. The state meets the guarantee using both state General Fund and local property tax revenue. The Legislature can suspend the minimum guarantee for one year at a time with a two–thirds vote of each house. The box below summarizes the original arguments for and against Proposition 98.

Original Arguments For and Against Proposition 98

The November 1988 voter guide contained arguments for and against Proposition 98. Whereas the proponents argued that school funding was too low and associated state budget decisions too political, the opponents argued that school funding was sufficient and associated decision making appropriately political.

Arguments in Support of Measure. Those in favor of Proposition 98 claimed that classes were overcrowded, insufficient attention was being given to core subjects, schools had too few counselors, and local and state funding for schools was on the decline. Proponents pointed to disagreement among state politicians as an obstacle to addressing these problems. Proponents argued that Proposition 98 would take “school financing out of politics by ensuring a minimum funding level for schools which the Legislature and Governor must honor except in fiscal emergencies.”

Arguments in Opposition to Measure. Those opposed to the measure claimed that education already was California’s top budget priority, school funding had increased significantly in recent years, and average teacher salaries were among the highest in the nation. Opponents further argued that Proposition 98 was an attempt to guarantee a certain level of state funding for schools and community colleges “regardless of whether they are going a good job in spending those funds” and “regardless of any other vital state and local needs.”

Two Years Later, Proposition 111 Made Substantial Changes to Calculation of Minimum Guarantee. In June 1990—facing an economic recession and having difficulty meeting the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee—the Legislature placed Proposition 111 on the ballot. Approved by 52 percent of voters, Proposition 111 further amended Section 8 of Article XVI of the Constitution. Specifically, Proposition 111 allowed for a lower minimum guarantee when state General Fund revenue was relatively weak but then required future growth in K–14 funding to be accelerated when General Fund revenue improved.

Proposition 2 Created Reserve Inside Minimum Guarantee. Approved by 69 percent of voters in November 2014, Proposition 2 added Section 21 to Article XVI of the Constitution. This new section created the Public School System Stabilization Account (School Stabilization Account) and set forth rules governing the account. Generally, the rules are intended to require the state to make deposits when growth in state General Fund revenue is strong and make withdrawals when needed to ensure prior–year school funding can grow for changes in student enrollment and inflation. The measure does not change the calculation of the minimum guarantee, but it can result in a portion of funding that counts toward the guarantee sometimes being reserved for spending in a future year.

Rules for Determining Minimum Guarantee

Minimum Guarantee Determined by One of Three “Tests.” Under the provisions of the Constitution, the minimum guarantee is determined by one of three formulas or tests. Figure 1 describes these tests. Proposition 98 created two tests, commonly referred to as “Test 1” and “Test 2,” and specified that the guarantee was to be the higher of the two test levels. Proposition 111 modified one aspect of Test 2 and added another test, commonly called “Test 3.” Under Proposition 111, the Test 2 and Test 3 levels are to be compared, with the lower test level prevailing. The rationale for this comparison is to allow the state to provide less K–14 funding when state General Fund revenue is weak relative to per capita personal income. Below, we discuss various aspects of the tests in detail.

Test 1 Factor Linked to Share of General Fund Revenue. Test 1 links K–14 funding to the percentage of General Fund revenue the state provided to K–14 education in 1986–87. In that year, K–14 funding was 41 percent of the General Fund. Since that year, the Test 1 share has ranged from 35 percent to 41 percent. It has varied as a result of statutorily authorized recalibrations or “rebenchings” (discussed later in this report). In Test 1 years, schools and community colleges receive local property tax revenue on top of whatever state General Fund revenue they receive.

Test 2 and Test 3 Based on Prior–Year Proposition 98 Funding. Whereas Test 1 earmarks a minimum portion of state revenue for K–14 education, Test 2 and Test 3 are based on prior–year Proposition 98 funding adjusted for key factors. Both tests adjust for the change in student enrollment, as measured by K–12 average daily attendance (ADA). Test 2 further adjusts for the change in inflation. Proposition 98 defined inflation as the lower of the United States Consumer Price Index and California per capita personal income. Proposition 111 modified the definition—linking inflation solely with the change in California per capita personal income. Instead of adjusting for inflation, Test 3 adjusts for the change in state General Fund revenue. (Technically, Test 3 is based on the change in state General Fund revenue plus 0.5 percent.) In both Test 2 and Test 3 years, the state’s Proposition 98 General Fund obligation is the minimum guarantee less local property tax revenue provided for K–14 education.

Test 2 Operative More Frequently Than Other Tests. Figure 2 shows the operative test used to determine the minimum guarantee each year since 1988–89. Test 2 has been most common over the entire period—operative more than half the time. Test 1 was the least common test during the first 22 years of the period, being operative only once. More recently, Test 1 has become much more common, operative four of the last five years. The Legislature has overridden the operative test and unconditionally suspended Proposition 98 twice (in 2004–05 and 2010–11). In three other years (1989–90, 1992–93, and 1993–94), the state adopted “poison pills” that suspended Proposition 98 if certain conditions subsequently were met. In none of these three cases did the conditions triggering suspension materialize. (We discuss poison pills in detail later in the report.)

Figure 2

Operative Proposition 98 Test

|

Operative Test |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

1988–89 |

X |

||

|

1989–90 |

Xa |

||

|

1990–91 |

X |

||

|

1991–92 |

X |

||

|

1992–93 |

Xa |

||

| 1993–94 |

Xa |

||

|

1994–95 |

X |

||

|

1995–96 |

X |

||

|

1996–97 |

X |

||

| 1997–98 |

X |

||

|

1998–99 |

X |

||

|

1999–00 |

X |

||

|

2000–01 |

X |

||

|

2001–02 |

X |

||

|

2002–03 |

X |

||

|

2003–04 |

X |

||

|

2004–05 |

Xb |

||

|

2005–06 |

X |

||

|

2006–07 |

X |

||

|

2007–08 |

X |

||

|

2008–09 |

X |

||

|

2009–10 |

X |

||

|

2010–11 |

Xb |

||

|

2011–12 |

X |

||

|

2012–13 |

X |

||

|

2013–14 |

X |

||

|

2014–15 |

X |

||

|

Totals |

5 |

15 |

7 |

|

aIn these years, the state adopted “poison pills” that suspended Proposition 98 under certain conditions. bIn these years, the state suspended Proposition 98 and funded at a legislatively determined level rather than the formulaically derived level. |

|||

Test 3 Supplemental Appropriation

Test 3 Linked With Statutory Supplemental Appropriation. In 1990, the state adopted legislation creating an additional K–14 funding formula. Calculated when Test 3 is operative, the formula is intended to ensure that Proposition 98 funding still grows at least as much as the non–Proposition 98 side of the budget. Given its intent, the formula is commonly known as the “equal pain/equal gain” formula. Technically, the formula links the rate of change in Proposition 98 funding per K–14 pupil to the rate of change in non–Proposition 98 General Fund revenue per capita. The state provides any resulting amount as a supplemental appropriation on top of the minimum guarantee otherwise calculated for that year.

Most Test 3 Years Require Supplemental Appropriations. Figure 3 shows every Test 3 supplemental appropriation the state has made to date. Of the seven years that Test 3 has been operative, a supplemental appropriation has been made six times. The size of these appropriations has ranged from $68 million in 1990–91 to $1.4 billion in 2001–02. The only Test 3 year the state did not make a supplemental appropriation was in 1993–94. That year the state shifted more local property tax revenue to schools and community colleges to free up General Fund support for the rest of the budget. Under the equal pain/equal gain provision, the freed–up General Fund for the rest of the budget would have triggered a supplemental school payment of nearly $900 million, negating a significant portion of the desired state benefit. In response, the 1993–94 budget plan excluded the shift from the equal pain/equal gain calculation. Under this approach, the state did not owe a supplemental appropriation.

Figure 3

Supplemental Appropriations

In Test 3 Years

(In Millions)

|

Amount |

|

|

1990–91 |

$68 |

|

1992–93 |

639 |

|

1993–94 |

— |

|

2001–02 |

1,367 |

|

2006–07 |

93 |

|

2007–08 |

403 |

|

2008–09 |

687 |

Maintenance Factor

A “Maintenance Factor” Is Created in Two Situations. In addition to its other changes, Proposition 111 added constitutional provisions creating a maintenance factor under certain conditions. Specifically, the state creates a maintenance factor when Test 3 is operative or the minimum guarantee is suspended. These two situations tend to arise either when the state is experiencing an economic downturn or a structural budget imbalance. The maintenance factor reflects the difference between the actual level of funding appropriated that year and the Test 1 or Test 2 level (whichever is higher). Until paid off, the outstanding maintenance factor obligation grows each year moving forward for changes in student enrollment and per capita personal income.

New Maintenance Factor Obligations Created Eight Times Since Proposition 111 Approved. The first column of Figure 4 shows the eight years that the state has had new maintenance factor obligations. To date, the largest maintenance factor obligation created in a single year was $9.9 billion in 2008–09. A new maintenance factor obligation does not necessarily imply that the minimum guarantee has fallen from the prior year. In five of the eight years in which the state created new maintenance factor, Proposition 98 funding increased from the prior year. The three exceptions (1993–94, 2008–09, and 2010–11) occurred following the onset of deep recessions.

Figure 4

Maintenance Factor Obligations

(In Billions)

|

New |

Paid |

Outstandinga |

|

|

1990–91 |

$1.6 |

— |

$1.6 |

|

1991–92 |

— |

$0.8 |

0.9 |

|

1992–93b |

— |

— |

1.0 |

|

1993–94 |

1.2 |

— |

2.2 |

|

1994–95 |

— |

1.2 |

1.0 |

|

1995–96 |

— |

0.8 |

0.3 |

|

1996–97 |

— |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

1997–98 |

— |

0.2 |

— |

|

1998–99 |

— |

— |

— |

|

1999–00 |

— |

— |

— |

|

2000–01 |

— |

— |

— |

|

2001–02 |

3.8 |

— |

3.8 |

|

2002–03 |

— |

0.7 |

3.1 |

|

2003–04 |

— |

1.3 |

1.9 |

|

2004–05 |

—c |

— |

2.0 |

|

2005–06 |

— |

2.1 |

— |

|

2006–07 |

0.2 |

— |

0.2 |

|

2007–08 |

1.1 |

— |

1.3 |

|

2008–09 |

9.9 |

— |

11.2 |

|

2009–10 |

— |

2.1 |

9.2 |

|

2010–11 |

1.4 |

— |

10.4 |

|

2011–12 |

— |

— |

10.6 |

|

2012–13 |

— |

5.2 |

5.9 |

|

2013–14 |

— |

— |

6.2 |

|

2014–15 |

— |

5.7 |

0.5 |

|

aOutstanding maintenance factor is adjusted annually for the change in student attendance and California per capita personal income. bThough Test 3 was operative, the state created no new maintenance factor because it made a supplemental appropriation resulting in the total amount of Proposition 98 funding equaling the Test 2 level. cTest 2 was operative but the state retained roughly the same level of outstanding maintenance factor due to the suspension of the minimum guarantee. |

|||

Maintenance Factor Payments Derived by Formula. The second column of Figure 4 shows maintenance factor payments. The state is to make a maintenance factor payment when state revenue is strong relative to per capita personal income. The size of the required maintenance factor payment depends on the difference between the growth in General Fund revenue and per capita personal income, with larger payments required when General Fund growth is significantly outpacing growth in personal income. To date, the state has been required to make maintenance factor payments 11 times. The largest payment made to date was $5.7 billion in 2014–15.

State Typically Carrying Outstanding Maintenance Factor. The third column of Figure 4 tracks the state’s total outstanding maintenance factor obligation. The state typically is carrying some amount of outstanding maintenance factor, with an outstanding obligation existing 20 of the past 25 years. The largest outstanding maintenance factor the state has ever carried was $11.2 billion at the end of 2008–09. The only prolonged period without any outstanding maintenance factor obligation was the four–year period extending from 1997–98 through 2000–01, a period of sustained economic prosperity for California.

Other Key Provisions

Constitution Includes a Formula to Address Revenue Spikes. In addition to creating Test 3 and maintenance factor, Proposition 111 created a constitutional formula commonly referred to as “spike protection.” The formula is intended to estimate the portion of school funding associated with one–time revenue spikes and exclude that funding from future Proposition 98 calculations. Specifically, if Test 1 is operative and exceeds the Test 2 level by more than 1.5 percent of General Fund revenue, then any amount in excess of the 1.5 percent threshold does not count for purposes of calculating the minimum guarantee the following year. To date, this provision has been operative twice. In 2012–13, the spike protection provision had the effect of lowering the 2013–14 minimum guarantee by $2.2 billion from what it otherwise would have been, and in 2014–15, the provision had the effect of lowering the 2015–16 minimum guarantee by $1 billion.

Constitution Includes Rules for Deposits Into and Withdrawals From School Stabilization Account. Proposition 2 set forth a complex set of rules governing the timing and size of the state’s deposits into and withdrawals from the School Stabilization Account. The state is to make a deposit if all of the following conditions are met: Test 1 is operative, the state has not suspended the minimum guarantee, the state has retired all maintenance factor existing prior to 2014–15, and the state has first funded the prior–year funding level adjusted for changes in ADA and the higher of two inflationary measures—the change in per capita personal income or the state and local government price index. In addition to these conditions, tax revenue related to capital gains must exceed 8 percent of total General Fund revenue. The Legislature can suspend or reduce an otherwise required deposit if the Governor declares a fiscal emergency. If the state is to make a deposit, the size of the deposit is capped at the difference between the Test 1 and Test 2 levels that year. The cumulative amount in the School Stabilization Account is capped at 10 percent of total Proposition 98 funding provided that year. The measure requires the state to make withdrawals whenever the account has a positive balance and Proposition 98 funding is insufficient to support the prior–year funding level adjusted for ADA and the higher of the two inflationary measures. To date, the state has not made any deposits into the account.

Back to the TopTrue Ups

The formulas governing Proposition 98 depend upon many inputs that can change after the adoption of the state budget. The state revises its estimates and trues up the guarantee for these changes. Below, we describe how the state trues up the guarantee; track how the state has addressed resulting increases and decreases in the guarantee; highlight some of the unexpected results of true ups; and explain “certification,” the statutory mechanism the state created to finalize its Proposition 98 calculations.

True Up Process

State Updates Proposition 98 Inputs and Correspondingly Revises Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee. At the time of initial budget enactment, the state typically funds at the minimum guarantee. Over subsequent months, the state updates most of the Proposition 98 inputs, including estimates of student attendance and General Fund revenue. The state does not lock down most Proposition 98 inputs until after the end of a fiscal year. Particularly in the case of General Fund revenue, revisions can be made over many months and changes between initial and final budget estimates can be notable. When estimates of Proposition 98 inputs are revised, the state recalculates the minimum guarantee. The state then typically adjusts Proposition 98 funding to align it with the final estimate of the minimum guarantee.

Often Big Differences Between Initial and Final Proposition 98 Funding Levels. For each year since 1988–89, Figure 5 compares initial and final Proposition 98 funding levels. Over the past 27 years, the final Proposition 98 funding level has been higher than the original budget act level 15 years and lower 12 years. Differences have been as large as $6.3 billion on the upside (in 2014–15, reflecting a 10 percent increase from the original budget act level) and as large as $8.9 billion on the downside (in 2008–09, reflecting a 15 percent drop from the original budget act level).

Figure 5

Initial and Final Proposition 98 Funding Levels

(Dollars in Billions)

|

Original Budget Act Funding Level |

Final Funding Levela |

Difference |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

1988–89 |

$18.9 |

$19.4 |

$0.4 |

2.3% |

|

1989–90 |

20.8 |

21.1 |

0.3 |

1.2 |

|

1990–91 |

22.7 |

21.2 |

–1.5 |

–6.7 |

|

1991–92 |

24.6 |

23.6 |

–1.0 |

–4.1 |

|

1992–93 |

24.6 |

23.8 |

–0.8 |

–3.1 |

|

1993–94 |

24.5 |

23.5 |

–1.0 |

–4.0 |

|

1994–95 |

24.9 |

25.2 |

0.4 |

1.5 |

|

1995–96 |

26.3 |

27.9 |

1.6 |

6.0 |

|

1996–97 |

29.1 |

30.3 |

1.2 |

4.1 |

|

1997–98 |

32.5 |

32.8 |

0.3 |

1.1 |

|

1998–99 |

35.2 |

35.6 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

|

1999–00 |

37.8 |

39.8 |

1.9 |

5.1 |

|

2000–01 |

42.8 |

42.9 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

2001–02 |

45.4 |

43.4 |

–2.0 |

–4.5 |

|

2002–03 |

46.5 |

44.3 |

–2.2 |

–4.8 |

|

2003–04 |

45.7 |

47.0 |

1.3 |

2.8 |

|

2004–05 |

49.3 |

48.7 |

–0.6 |

–1.2 |

|

2005–06 |

49.2 |

53.3 |

4.1 |

8.3 |

|

2006–07 |

55.1 |

54.8 |

–0.3 |

–0.5 |

|

2007–08 |

57.1 |

56.6 |

–0.5 |

–1.0 |

|

2008–09 |

58.1 |

49.2 |

–8.9 |

–15.3 |

|

2009–10 |

50.4 |

51.6 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

|

2010–11 |

49.7 |

49.6 |

–0.0 |

–0.0 |

|

2011–12 |

49.7 |

47.3 |

–2.4 |

–4.9 |

|

2012–13 |

53.5 |

58.0 |

4.4 |

8.3 |

|

2013–14 |

55.3 |

58.9 |

3.6 |

6.6 |

|

2014–15 |

60.9 |

67.1 |

6.3 |

10.3 |

|

aReflects higher of actual appropriation or minimum guarantee including settle–up obligation. |

||||

Upward and Downward Revisions

State “Settles Up” When the Guarantee Exceeds Initial Budget Estimate. When the final minimum guarantee is higher than the initial estimate, the state is required to settle up—making an additional appropriation to meet the higher guarantee.

State Sometimes Has Settled Up Immediately. Sometimes the state has settled up as a fiscal year is ending. For example, in 2014–15, an upward revision to the estimate of state General Fund revenue increased the minimum guarantee by $5.4 billion, and the state provided the corresponding Proposition 98 augmentation as part of its June 2015 budget package. Sometimes the state has been required to settle up again due to further upward revisions to the minimum guarantee. For example, when the 2014–15 minimum guarantee later increased by an additional $843 million due to even higher revenue estimates, the state provided the corresponding augmentation as part of its June 2016 budget package. The state has settled up while the fiscal year is ending or shortly thereafter several times, including in 2003–04, 2005–06, 2012–13, and 2013–14.

At Other Times, State Has Settled Up Several Years Later. In other cases, the state has not settled up immediately. In some of these instances, the state has created out–year payment plans. For example, in 2004, the state estimated it had a total outstanding settle–up obligation of $1.4 billion associated with increases in the minimum guarantees for 1995–96, 1996–97, 2002–03, and 2003–04. Chapter 216 of 2004 (SB 1108, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) appropriated $150 million annually beginning in 2006–07 for the purpose of paying off this outstanding obligation. (The state later superseded this payment schedule with one–time payments of $300 million in 2006–07 and $1.1 billion in 2008–09.) In other instances, the state has recorded an obligation but scheduled the payment far in the future. For example, in July 2009 the state identified a $212 million obligation related to meeting the 2006–07 minimum guarantee and scheduled the payment for 2014–15 (later changed to 2015–16). In some cases, the state has recorded an obligation without adopting a complete payment schedule. For example, in October 2010, the state recorded a $1.8 billion settle–up obligation for 2009–10. At that time, the state made an initial payment of $300 million but adopted no specific plan for paying the remainder of the obligation. (The state nonetheless made partial settle–up payments for 2009–10 in 2015–16 and 2016–17.)

State Has Designated Settle–Up Funding for Various Proposition 98 Initiatives and Programs. When the state provides additional funding to meet a higher minimum guarantee, it may designate that additional funding for any Proposition 98 purpose. In strong economic times, the state has designated settle–up funding for a wide range of one–time purposes, from paying down the education mandates backlog to creating or temporarily expanding discretionary school district and school site block grants; art, music, and physical education block grants; school and staff performance awards; teacher recruitment initiatives; staff development; programs for English learners; adult education; school safety and community policing; instructional materials; computers and other education technology; deferred maintenance; emergency facility repairs; child care facilities; new facilities to support class size reduction; and career technical education equipment. During the most recent economic recovery, the state also used settle–up funding for eliminating education payment deferrals initiated in previous years. In weaker economic times, the state has used settle–up payments as one–time backfills for ongoing programs. For example, in 2008–09 the state dedicated $1.1 billion in settle–up funding toward K–12 revenue limits.

State Has $1 Billion Outstanding Settle–Up Obligation. As of July 2016, the state has retired the settle–up obligations for all years prior to 2009–10. It has a total outstanding settle–up obligation of $1 billion, consisting of $903 million for 2009–10, $98 million for 2011–12, and $13 million for 2013–14. To date, the state has not established an associated payment plan.

State Has Taken Various Actions When the Guarantee Has Dropped. Eleven of the 12 times that the minimum guarantee has dropped after initial budget enactment, the state has taken action to reduce Proposition 98 funding to the updated estimate of the guarantee. (The exception is 2010–11, when spending adjusted downward automatically due to a decline in student attendance.) Specific state actions to reduce Proposition 98 spending have included (1) deferring some program payments until the next fiscal year, (2) swapping ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund monies with special fund monies and unspent Proposition 98 monies from prior years, (3) reclassifying spending as paying outstanding settle–up obligations, (4) no longer forward funding certain programs, (5) postponing first–year funding for certain programs, and (6) making various midyear cuts to education programs. Regarding programmatic cuts, the state typically has reduced funding in targeted ways, for example, making cuts to teacher professional development and facility maintenance programs. In a few cases, the state has applied across–the–board reductions to Proposition 98 programs.

Unexpected Results of True Ups

Some Changes in Inputs Can Lead to Unexpected Results. Sometimes updating the Proposition 98 inputs has changed the minimum guarantee in ways that legislators and others have not expected. The most common surprises have involved how changes in state revenue, per capita personal income, and state population estimates affect the guarantee. Legislators and others also sometimes have been surprised that the minimum guarantee has moved in one direction while the Proposition 98 General Fund share of the guarantee has moved in the opposite direction. These latter surprises are connected to changes in property tax revenue estimates. We describe each of these counterintuitive situations in detail below.

Guarantee Can Increase When State Revenue Drops. When General Fund revenue estimates for the current year and the budget year fall, the budget–year minimum guarantee can increase. This happened, for example, when the state was building the 2012–13 budget. At the time of the 2012–13 May Revision, General Fund revenue estimates dropped below January estimates by $2.1 billion in 2011–12 and $300 million in 2012–13. Because the drop in 2011–12 was greater than the drop in 2012–13, the year–over–year growth rate in per capita General Fund revenue increased (from 7.5 percent to 10.1 percent). The higher growth rate required the state to make a larger maintenance factor payment, which in turn increased the 2012–13 minimum guarantee by $1.2 billion over the January level. In a few cases, revisions to other Proposition 98 inputs have resulted in higher minimum guarantees despite declines in state revenue. One notable instance occurred during the development of the 2002–03 budget. At the time of the 2002–03 May Revision, General Fund revenue estimates for 2001–02 and 2002–03 had fallen a total of $9.5 billion from January levels, yet the estimate of the 2002–03 minimum guarantee increased by $1.2 billion. This increase largely was attributable to an upward revision in per capita personal income (from –3 percent to –1.3 percent), the key Proposition 98 growth factor that year.

Guarantee Can Increase When State Population Drops. Estimates of the state’s civilian population affect both per capita personal income and per capita General Fund revenue. When the state revises its estimate of the civilian population, these two key Proposition 98 inputs in turn change. Drops in the civilian population increase per capita amounts. For example, as part of the 1997–98 May Revision, the Department of Finance reduced its 1996 estimate of the state’s population, which increased per capita General Fund revenue growth. In turn, the minimum guarantees for 1995–96, 1996–97, and 1997–98 increased (by almost $600 million combined over the three years, largely as a result of higher required maintenance factor payments). Later, as part of the 2000–01 May Revision, the minimum guarantees for these three years were increased again (by more than $500 million) as a result of new census data reflecting even less population growth.

Guarantee Can Fall While Proposition 98 General Fund Cost Rises. This dynamic occurs when estimates of local property tax revenue fall more than estimates of the guarantee. In this situation, the General Fund backfills for the loss of local property tax revenue, thereby increasing the Proposition 98 General Fund share. Factors unfolded in this way, for example, in 2007–08. Between July 2007 and July 2009, estimates of the 2007–08 minimum guarantee fell by about $550 million, but the General Fund share of the guarantee increased by $540 million. The increase in the General Fund share was due to a more than $1 billion drop in projected local property tax revenue.

Certification

State Created Certification Process to Finalize Proposition 98 Calculations. Proposition 98 did not contain any specific mechanism to finalize the calculation of the minimum guarantee. Implementing legislation adopted in 1989 assigned this responsibility to the Director of Finance, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges. Under state law, these individuals are to agree upon and certify a final calculation of the minimum guarantee within nine months following the end of the fiscal year.

Certification Has Happened a Few Times. Though the law is designed such that certification is to occur annually, the state agencies responsible for certification rarely have agreed on all aspects of the Proposition 98 calculations. Disagreements about which programs should be funded through Proposition 98 delayed certification of the 1988–89 guarantee until 1992. Disagreements primarily about the amount of property tax revenue to count toward the guarantee delayed certification for the 1990–91 through 1994–95 years until 1996. Further disagreements resulted in no additional certifications until 2006—at which time the 1995–96 through 2003–04 years were certified. As of this writing, 2007–08 is the last year for which the state has certified the guarantee. (In 2008–09, the state adopted legislation specifying the final minimum guarantee for that year, but it did not explicitly certify it.) When the state certifies the minimum guarantee for a particular year, any amount exceeding the previous estimate of that guarantee becomes a settle–up obligation.

Back to the TopRevenue and Program Shifts

Whereas the earlier parts of this report focus on basic funding formulas and routine true ups, this section tracks the various ways the state has adjusted the formulas. Below, we first identify revenue shifts affecting the Proposition 98 calculations. We then track programs shifted into or out of the minimum guarantee.

Revenue Shifts

Twenty Four Revenue Shifts Affecting Proposition 98 Calculations. As evident in Figure 6, few years have passed since 1988 without the state making at least one revenue shift affecting the Proposition 98 formulas. The state has authorized most of these shifts via statute, typically as part of a budget package, though the state has placed a few of the shifts before voters via ballot measure. Shifts have been most common during times when the state has struggled to balance its budget. The only prolonged period when the state did not make any revenue shifts was from 1995–96 through 2001–02—a period throughout most of which state revenue grew rapidly.

Figure 6

Major Revenue–Related Actions Affecting Proposition 98 Calculations

|

State Action |

Fiscal Effecta |

||

|

1989–90 |

Loma Prieta Earthquake Disaster Relief. State excluded revenue generated by a temporary quarter–cent sales tax increase from the Proposition 98 calculations. State dedicated revenues to disaster relief. |

Raised a total of $800 million in state revenue over 1989–90 and 1990–91, with no associated increase in the minimum guarantee. |

|

|

1991–92 |

1991 Realignment. State provided revenue from a new ongoing half–cent sales tax increase to local governments as part of realigning certain health and human services programs. State excluded revenue from Proposition 98 calculations. |

Raised $1.4 billion in state revenue, with no associated increase in the minimum guarantee. |

|

|

1992–93 |

Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF) Shift. State required cities, counties, and special districts to shift property tax revenue on an ongoing basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $1.1 billion. |

|

|

Redevelopment Agencies (RDAs) Shift. State required RDAs to shift revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $205 million. |

||

|

Vehicle License Fee (VLF) Roundabout. State required cities and counties to shift property tax revenue on a one–time basis to schools. Cities and counties were backfilled with VLF revenue. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $100 million. |

||

|

1993–94 |

ERAF Shift. State required cities, counties, and special districts to shift additional property tax revenue on an ongoing basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $2.6 billion. |

|

|

RDA Shift. State required RDAs to shift revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $65 million. |

||

|

1994–95 |

RDA Shift. State required RDAs to shift revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $65 million. |

|

|

2002–03 |

RDA Shift. State required RDAs to shift revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $75 million. |

|

|

2003–04 |

RDA Shift. State required RDAs to shift revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $135 million. |

|

|

2004–05 |

VLF Swap. State required school and community college districts to shift property tax revenue on an ongoing basis to cities and counties to backfill for reduced VLF revenue. |

Increased Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $4.1 billion. |

|

|

ERAF Shift. State required cities, counties, special districts, and RDAs to shift property tax revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $1.3 billion. |

||

|

Triple Flip. State shifted property tax revenue from school and community college districts to cities and counties to backfill for redirected local sales tax revenue used to retire state Economic Recovery Bonds (ERBs). |

Increased Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $1.1 billion per year until ERBs retired. |

||

|

2005–06 |

ERAF Shift. State required cities, counties, special districts, and RDAs to shift property tax revenue on a one–time basis to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $1.3 billion. |

|

|

2008–09 |

RDA Shift. State required RDAs on a one–time basis to shift $350 million into ERAF. A superior court invalidated the action in April 2009 and the state subsequently retracted it. |

Would have reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $350 million. |

|

|

2009–10 |

Supplemental Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (SERAF) and Supplemental Revenue Augmentation Fund (SRAF) Shifts. In a complicated financing mechanism, RDAs deposited revenue into SERAF, which triggered a reduction in certain school districts’ base property tax allocations, with the base revenue in turn shifted to SRAF. SRAF first paid for various state costs within counties, with the remainder transferred to ERAF and used to reduce Proposition 98 General Fund costs. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $850 million. |

|

|

2010–11 |

SERAF and SRAF. State continued using SERAF, SRAF, and ERAF to reduce Proposition 98 General Fund costs. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $350 million. |

|

|

2011–12 |

2011 Realignment. State redirected a portion of its existing sales tax rate (1.0625 cent) on an ongoing basis to various local public safety programs. Statute excluded associated revenue from Proposition 98 calculations as long as voters approved a ballot measure before November 17, 2012 that (1) authorized the exclusion and (2) provided an equal amount of Proposition 98 funding. Voters approved Proposition 30, which met these conditions. |

Stopped counting $5.1 billion in state General Fund toward the Proposition 98 calculations, dropping the guarantee by $2.1 billion. |

|

|

RDA Dissolution and Remittance Payments. State dissolved RDAs but allowed them to retain some power by making remittance payments to schools, fire protection districts, and transit districts. The California Supreme Court upheld RDA dissolution but deemed the remittance payments unconstitutional, negating the General Fund benefit. |

Would have reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $1.7 billion. |

||

|

Gas Tax Swap. State eliminated its sales tax on gasoline, which had counted toward the guarantee, and replaced it with an excise tax that otherwise would not count toward the guarantee. The state initially held schools and community colleges harmless by assuming the gas sales tax revenue still existed for the purposes of Proposition 98 calculations. |

Increased minimum guarantee and Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $578 million. |

||

|

2012–13 |

Revenue From Former RDAs. State required former RDAs to shift all their existing revenue and assets, less debt, to cities, counties, schools, and community colleges. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $3.2 billion. |

|

|

Gas Tax Swap. The state retracted its earlier decision and decided not to hold schools and community colleges harmless for the elimination of the sales tax on gasoline. |

Reduced 2011–12 minimum guarantee and Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $609 million. |

||

|

2013–14 |

Revenue From Former RDAs. For Test 1 years, state stopped reducing Proposition 98 General Fund costs for the increase in former RDA revenue shifted to school and community college districts, meaning districts receive greater total funding these years. |

Upon completion of revenue shift, potential benefit to school and community college districts of up to $1 billion, but no benefit provided in Test 2 and Test 3 years. |

|

|

2015–16 |

Triple Flip. State paid off a portion of the ERBs in 2015–16, with the remainder retired in 2016–17. The end of the triple flip shifted property tax revenue back to school and community college districts. |

Reduced Proposition 98 General Fund cost by $1.2 billion in 2015–16 and $1.7 billion on an ongoing basis. |

|

|

aReflects estimate for that year at the time of initial enactment. In several cases, final amounts for that year varied significantly from initial budget estimates. |

|||

Most Revenue Adjustments Have Entailed Local Property Tax Shifts. Of the 24 revenue–related actions with Proposition 98 implications, 19 involved property tax shifts. The vast majority of the property tax shifts (17 of the 19) involved shifting local property tax revenue from other local governments (cities, counties, special districts, or redevelopment agencies) to school districts and community colleges. In these cases, the shifts helped the state balance its budget by reducing the General Fund share of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. To ensure the state obtained both initial and ongoing General Fund benefit, the state rebenched the Test 1 factor for these shifts. Specifically, the state lowered the share of the General Fund used for Test 1 to account for the additional property tax revenue directed to schools and community colleges. (If Test 1 was not operative the year a shift occurred, the state still rebenched to ensure out–year General Fund benefit.) In the other two shifts—the vehicle license fee swap and the triple flip—property tax revenue was shifted away from schools and colleges. In these two cases, the state also rebenched the General Fund Test 1 factor, but the factor was increased to account for the reduced property tax revenue directed to schools and community colleges.

Remaining Actions Involved Sales Tax Revenue. Since 1988, the state has taken five sales tax–related actions that have had significant Proposition 98 implications. Two of the five actions involved the devolution of certain programs from the state to the local level. For both the 1991–92 and 2011–12 realignments, the state designated sales tax revenue for the program realignments and permanently excluded the associated revenue from the Proposition 98 calculations. Two other cases involved gasoline. In 2010–11, the state replaced the sales tax on gasoline, which had counted toward the Proposition 98 calculations, with an excise tax on gasoline, which otherwise would not count. To hold schools and community colleges harmless from the change, the state estimated the amount generated if the sales tax on gasoline had remained in effect and counted that amount toward the Proposition 98 calculations. In 2011–12, the state retracted this hold harmless provision. The other action occurred in 1989–90 when the state levied a temporary sales tax increase and used all proceeds for disaster relief in response to the Loma Prieta earthquake, excluding the revenue from the Proposition 98 calculations.

Program Shifts

Proposition 98 Implementing Legislation Specified What to Include and Exclude From Minimum Guarantee. Proposition 98 specified that its funding formulas and rules were “to be applied by the State for the support of school districts and community college districts.” In 1989, the state enacted implementing legislation specifying certain programs that were and were not to count toward the minimum guarantee. The implementing legislation specified that “any appropriation not made for allocation to a school district…or to a community college district” be excluded from the guarantee. The same legislation, however, specified that all subsidized child care and preschool programs (some of which were not operated by districts) be included in the minimum guarantee. Additionally, the implementing legislation specifically excluded state appropriations for the Teachers’ Retirement Fund and the Public Employees’ Retirement Fund, as well as state appropriations made to service any public debt approved by California voters. In 1996, the state enacted related legislation specifying that appropriations not made for allocation to school districts or community college districts could count toward the minimum guarantee only if provided “statutory authorization independent of the annual Budget Act.”

Several Programmatic Shifts Linked With Rebenchings of Minimum Guarantee. On several occasions, the state has shifted programs between the Proposition 98 and non–Proposition 98 sides of the budget. When the state has made these shifts, it has continued to support the program but replaced Proposition 98 funds with non–Proposition 98 funds or vice versa. Figure 7 lists the instances when the state shifted programs and correspondingly rebenched the guarantee. Rebenching entailed increasing the minimum guarantee for programs shifted into Proposition 98 and decreasing the guarantee for programs shifted out of Proposition 98. For programs shifted into Proposition 98, rebenching avoided crowding out other school spending. For programs shifted out of Proposition 98, rebenching avoided crowding out other state spending.

Figure 7

Program Shifts Affecting Minimum Guarantee

|

Program(s) |

Shifted In or Out? |

Description of Action and Fiscal Effect |

|

|

1995–96 |

15 programs (Subject Matter Projects; Bilingual Teacher Recruitment; Math, Engineering, and Science Achievement; California School Leadership Academies; Advancement Via Individual Determination; International Studies; School Crime Report; Interstate Collaboratives; Exploratorium; Interactive Television; Intersegmental Committee; School Law Enforcement Project; Student Vocational Education Programs; Intergenerational Program; Geography Education Alliances) |

Out |

State shifted $22 million for these programs out of Proposition 98, lowering the minimum guarantee dollar for dollar. State began supporting the programs with non–Proposition 98 General Fund. |

|

2011–12 |

Child care programs and preschool wraparound care |

Out |

The state shifted $1.1 billion for child care programs and preschool wraparound care out of Proposition 98, lowering the minimum guarantee dollar for dollar. State began supporting programs with non–Proposition 98 General Fund. |

|

Student Mental Health Services |

In |

State shifted program into Proposition 98 and provided $222 million (about $70 million more than estimated prior–year program costs), increasing the minimum guarantee dollar for dollar. |

|

|

2012–13 |

Student Mental Health Services |

In |

State provided $99 million Proposition 98 funds to backfill for the loss of one–time Proposition 63 funds, increasing the minimum guarantee dollar for dollar. |

|

State general obligation bond debt service for school facilities |

In |

State created a trigger that would have begun paying these costs with Proposition 98 funds. Under the trigger, the state would have increased the minimum guarantee by $190 million, while increasing Proposition 98 costs by $2.5 billion. Voters approved Proposition 30, so the change did not go into effect. |

Various Methods Used to Rebench for Program Shifts. Though rebenching the minimum guarantee occurred for all the programs shown in Figure 7, the specific method the state used to rebench varied. In some of the instances shown on Figure 7, such as the shift of child care programs out of the minimum guarantee in 2011–12, the state rebenched the guarantee downward dollar for dollar based on the value of the programs in the prior year. By comparison, for the shift of student mental health services into the guarantee in 2011–12, the state first augmented funding for the services and then rebenched the guarantee. For the shift of debt service proposed in 2011–12, the state took yet another approach, rebenching the minimum guarantee based on the ratio of debt–service payments to total K–14 spending in 1986–87, when debt–service costs were much lower.

Several Programmatic Shifts Made Without Rebenching Minimum Guarantee. In several cases, the state has undertaken program shifts without rebenching the guarantee. Programs shifted into the guarantee without a corresponding increase in the guarantee include the University of California (UC) Professional Development Institutes (2002–03), the K–12 High Speed Network (2004–05), and preschool wraparound care provided by local educational agencies (2015–16). In a few cases, programs were shifted out and back again in quick succession. Most notably, in 2008–09, the state replaced Proposition 98 funding for the Home–to–School Transportation program with $593 million from the Public Transportation Account, without a corresponding reduction in the minimum guarantee. The next year, the state switched back to funding the program with Proposition 98 funds, without increasing the guarantee.

Two Authorized Shifts Linked With Triggers, One With, One Without Rebenching. In 2012–13, the state authorized two shifts but made them conditional on a ballot measure (Proposition 30) not passing. One of these shifts, involving school facility debt service, was to entail rebenching (as mentioned above), whereas the other shift, involving the Early Start program, was not to involve rebenching. As voters approved the measure, neither of these two programs ultimately were shifted into the guarantee.

Back to the TopMajor Controversies

In certain cases, the state has realized that the adjustments it was making to the Proposition 98 calculations might be challenged. In some of these cases, the state adopted poison pills that set forth seemingly dire repercussions if the state’s actions were challenged. In other instances, the state took no specific action to address potential challenges. On several occasions, the state was sued over its actions. Below, we discuss Proposition 98–related poison pills, litigation, court rulings, and settlements. We then discuss longstanding debates surrounding the payment and creation of maintenance factor in Test 1 years. We conclude this part of the report by discussing longstanding debates regarding which programs should be funded within the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

Poison Pills, Litigation, and Settlements

Four Poison Pills. In the period immediately following enactment of Proposition 98, the state adopted four Proposition 98–related poison pills. Three of the four poison pills involved a conditional suspension of Proposition 98, meaning if state actions were challenged, the state would suspend the guarantee. The fourth poison pill halted a tax increase if the state’s exclusion of the associated revenue from the Proposition 98 calculations were challenged. Each poison pill is described briefly in Figure 8. None of the consequences set forth in the poison pill provisions ultimately occured.

Figure 8

Proposition 98–Related Poison Pills

|

Poison Pill |

Legislation |

|

|

1989–90 |

State adopted language suspending Proposition 98 “to the extent that its provisions conflict” with the state’s treatment of sales tax revenue for disaster relief. |

Chapter 14 of 1989–90 First Extraordinary Session (SBX1 33, Mello) |

|

1991–92 |

State adopted language ceasing a new sales tax rate increase if a court ruled that the revenues counted toward the minimum guarantee. (Associated revenues were designated for various locally realigned programs.) |

Chapter 85 of 1991 (AB 2181, Vasconcellos) |

|

1992–93 |

State adopted language suspending Proposition 98 if an appellate court deemed “unconstitutional, unenforceable, or otherwise invalid” either the calculation of the Test 1 factor due to certain shifts of local property tax revenue or the designation of certain Proposition 98 funding as an “emergency loan.” |

Chapter 703 of 1992 (SB 766, no named author) |

|

1993–94 |

State adopted language suspending Proposition 98 “to the extent that its provisions conflict” with the state’s treatment of a sales tax rate increase for public safety realignment. |

Chapter 73 of 1993 (SB 509, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) |

Five Lawsuits, One Appellate Ruling, and Two Settlements. The state has been sued five times over its Proposition 98–related actions. In three of these suits, the California Teachers Association (CTA) led the suit against the state and, in the other two suits, the California School Boards Association led the suits. Four of these cases resulted in published court decisions, with the state prevailing in two of the four cases. One of these four cases (CTA v. Hayes) had an appellate court ruling, thereby providing legal precedent for future Proposition 98 cases. In CTA v. Schwarzenegger, the parties reached a settlement prior to the superior court ruling. The state also reached a settlement in the CTA v. Gould lawsuit after a superior court ruled against the state. These agreements were codified in state law. Figure 9 summarizes the challenge and outcome of each of the five lawsuits.

Figure 9

Proposition 98–Related Lawsuits and Settlements

|

Challenge |

Outcome |

|

|

1992 |

CTA v. Hayes. CTA challenged the state’s action to count child care and development funding toward the minimum guarantee. CTA argued that funding could be counted toward the guarantee only when allocated directly to local educational agencies. |

Appellate court ruled the Legislature had not been “arbitrary and unreasonable in its determination that the Child Care and Development Services Act furthers the purposes of public education,” and therefore could be funded within the minimum guarantee. Appellate court also affirmed that “under our Constitution the Legislature is given broad discretion in determining the types of programs and services which further the purposes of education.” |

|

1996 |

CTA v. Gould. CTA challenged the state’s actions in 1992–93 and 1993–94 to count certain Proposition 98 appropriations as loans. The loans were intended to avoid significant midyear cuts or year–over–year drops in per–pupil funding while allowing the state to count the funds toward meeting the guarantee the subsequent year(s). |

Superior court ruled the loans invalid. Parties subsequently reached a settlement agreement in April 1996. Chapter 78 of 1996 (SB 1330, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) codified the agreement. Chapter 78 repealed certain actions taken in 1992–93 and 1993–94, scheduled certain loan repayments from 1996–97 through 2001–02, increased the state’s outstanding maintenance factor obligation, and declared that such loan mechanisms were not to be used in the future. |

|

2006 |

CTA v. Schwarzenegger. CTA challenged the state’s Proposition 98 appropriation levels for 2004–05 and 2005–06. CTA argued the state intended to suspend the 2004–05 minimum guarantee by $2 billion, and the appropriation level for that year (and the next year) ended up being lower than intended. CTA sought $2.7 billion in additional Proposition 98 funding ($1.6 billion for 2004–05 and $1.1 billion for 2005–06). |

Settlement achieved prior to superior court ruling. Chapter 751 of 2006 (SB 1133, Torlakson) recognized additional Proposition 98 obligations for 2004–05 and 2005–06 and scheduled a total of $2.7 billion in associated payments over the subsequent seven–year period (2007–08 through 2013–14). |

|

2012 |

CSBA v. California. CSBA challenged the state’s decision to exclude certain sales tax revenue from the calculation of the 2011–12 minimum guarantee. Specifically, CSBA argued that when the state shifted revenue from the General Fund to local governments, it had to rebench the Test 1 factor upward to provide schools a higher share of the remaining General Fund. |

Superior court ruled that Proposition 98 did not prohibit the state from shifting revenue out of the General Fund or create an obligation to rebench the guarantee. CSBA appealed, but voters subsequently approved Proposition 30, which ratified the state’s action. |

|

2016 |

CSBA v. Cohen. CSBA challenged the state’s decision to pay preschool wraparound costs using Proposition 98 funds without a corresponding upward rebenching of the minimum guarantee. (The state previously had covered the costs using non–Proposition 98 funds.) |

Superior court ruled that “rebenching is constitutionally required to achieve the purposes of the minimum funding guarantee” and ordered the state to either rebench the guarantee or discontinue using Proposition 98 to fund wraparound costs. The state has appealed the decision. |

|

CTA = California Teachers Association and CSBA = California School Boards Association. |

||

Maintenance Factor Debates

Debate Over Payment of Maintenance Factor. Only a few years after the passage of Proposition 111, disputes began arising over how the Proposition 98 and Proposition 111 formulas were to interact in Test 1 years. One of the most significant disputes centered around how the state was to make a $1.2 billion maintenance factor payment in 1994–95. The administration contended that the state should calculate the minimum guarantee by adding the maintenance factor payment to the Test 2 funding level, comparing the resulting total to the Test 1 funding level, and providing schools and community colleges the higher of the two amounts. This approach would have increased school funding to the level needed to keep pace with growth in per capita personal income since 1988–89. The CTA believed that the state should calculate the minimum guarantee by first comparing the Test 1 and Test 2 funding levels and then adding the maintenance factor payment on top of the higher test. This approach would have increased school funding beyond the level required to keep pace with per capita personal income. The 1996 CTA v. Gould settlement acknowledged this dispute but did not resolve it. Instead, the parties to the lawsuit agreed that they would use the administration’s calculation for 1994–95 but not consider it precedent for any future litigation involving Proposition 98.

Debate Over Creation of Maintenance Factor. In addition to the dispute involving the payment of maintenance factor in Test 1 years, a dispute arose concerning whether a maintenance factor was created in Test 1 years. This dispute came to a head in 2008–09. In February 2009, initial Proposition 98 projections showed that the state could end up in an anomalous position—though General Fund revenue was expected to grow less quickly than per capita personal income, Test 1 rather than Test 3 was expected to be operative. As with the 1994–95 dispute, groups took differing positions based upon their conceptual understanding of the purpose of maintenance factor as well as the resulting implication for school funding. In response to the 2008–09 dispute, the Legislature placed Proposition 1B on the May 2009 ballot. Proposition 1B required the state to create a supplemental obligation in lieu of maintenance factor, to be paid over a period of several years. Proposition 1B was intended to ensure schools benefited regardless of which test ultimately became operative, but the measure offered no lasting resolution to the dispute. In July 2009, after voters rejected the measure, the Legislature and Governor agreed to finalize the Proposition 98 calculations based upon an updated revenue estimate showing that Test 3 had become operative and a maintenance factor obligation was created. As with Proposition 1B, this agreement did not address the underlying dispute about the formulas.

Maintenance Factor Debate Continues. Decisions about how to pay and whether to create maintenance factor in Test 1 years were key factors affecting the calculations of the 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2014–15 minimum guarantees (all Test 1 years). Regarding payments, the state decided to pay maintenance factor on top of the Test 1 level in 2012–13 and 2014–15, a reversal of its 1994–95 approach. Regarding the creation of new obligations, the state decided not to create any new maintenance factor in 2011–12, a reversal of its 2008–09 approach. The state has not been sued over these actions.

Program Debates

Many Debates Regarding Which Programs to Fund Within Minimum Guarantee. Since 1988, debates involving what programs to fund within the minimum guarantee have emerged almost every year. These debates have arisen primarily because Proposition 98 does not include specific principles that might guide legislators in determining what programs qualify for Proposition 98 funding. To date, many examples exist of the state supporting certain programs with Proposition 98 funds but very similar programs with non–Proposition 98 funds. Such inconsistencies have tended to kindle the ongoing debate as to what to fund within the guarantee. Below, we highlight several notable program inconsistencies.

Inconsistent Practice for Funding Statewide Functions. Several examples exist of the state using Proposition 98 funds to support some statewide functions but non–Proposition 98 funds to support other such functions. For example, the state has used Proposition 98 funds for helping districts in fiscal distress (through the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Teams administered by the Kern County Office of Education), supporting districts with academic performance issues (through the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence administered by the Riverside County Office of Education), and aiding districts in accessing and paying for Internet services (through the High Speed Network administered by the Imperial County Office of Education). It has used non–Proposition 98 funds to fulfill other statewide functions, including supporting districts’ career technical education, adult education, preschool, special education, and alternative education programs. In these cases, the California Department of Education has supported districts directly.

Inconsistent Practice for Funding Nonprofit Agencies. A plethora of examples exist of the state using Proposition 98 funds to support some nonprofit educational agencies but non–Proposition 98 funds to support other nonprofit educational agencies. For example, the state has funded the Institute for Computer Technology, Center for Civic Education, California College Guidance Initiative, and the Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California with Proposition 98 funds. It has funded other nonprofit organizations, such as the Exploratorium, California Association of Student Councils, and Advancement Via Individual Determination with non–Proposition 98 funds. In a few cases, the state has funded the same agency using different fund sources at different points in time. For example, the state began funding the Exploratorium with Proposition 98 funds in 2016–17.

Inconsistent Practices for Many Other Programs. Examples include:

- Teacher Preparation Programs. The state has funded district–run teacher internship programs and teacher training programs with Proposition 98 funds but funded university–run teacher preparation programs with non–Proposition 98 funds.

- Financial Aid for Teachers and Aides. The state has funded some financial aid, such as stipends for teachers and instructional aides, with Proposition 98 funds but funded other forms of financial aid, such as the Cal Grant T program and the Assumption Program of Loans for Education, with non–Proposition 98 funds.

- Financial Aid for Community College Students. The state has funded supplemental Cal Grant access awards for full–time community college students using Proposition 98 funds but funded their base Cal Grant access awards using non–Proposition 98 funds.

- College Outreach Activities. The state has funded college outreach and preparation programs administered by the California Department of Education and school districts with Proposition 98 funds but funded very similar college outreach and preparation programs administered by UC and the California State University with non–Proposition 98 funds.

- Facilities and Maintenance. The state has funded debt service on community college lease revenue bonds with Proposition 98 funds but paid debt service on school and community college general obligation bonds using non–Proposition 98 funds. The state also has used Proposition 98 funds for deferred maintenance, emergency facility repairs, and charter school facility grants.

Impact on School Funding

Although no one knows for certain how much funding the state would have provided since 1988–89 in the absence of Proposition 98, we use several methods to assess how schools fared during this time. We first compare actual Proposition 98 K–12 funding with the 1988–89 school funding level grown for the K–12 student population and inflation. We then compare growth in Proposition 98 and non–Proposition 98 funding over the period. Lastly, we compare school spending per student in California with the rest of the country. Below, we describe the results of these comparisons.

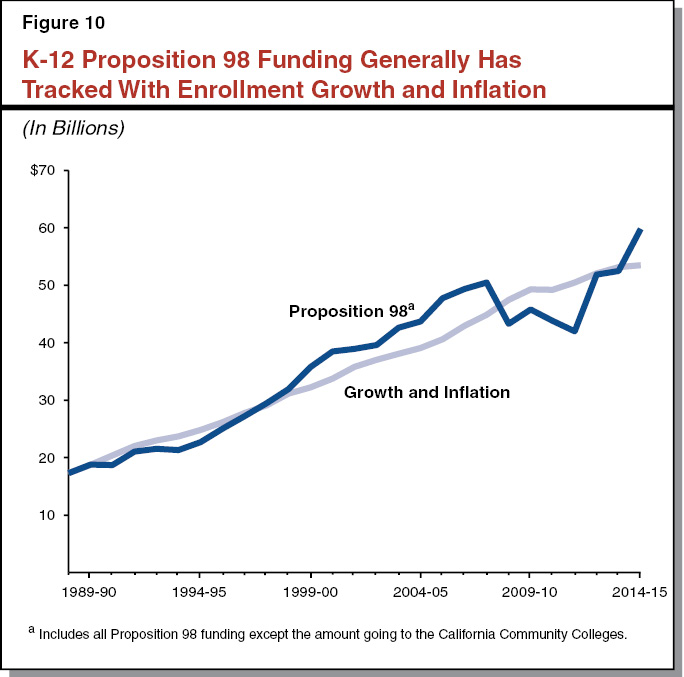

Proposition 98 Funding Over Period Generally Has Tracked With Enrollment Growth and Inflation. Figure 10 compares actual Proposition 98 funding for K–12 schools with the 1988–89 funding level adjusted for changes in enrollment and inflation, as measured by the state and local government price index. The state uses this “workload” approach to budget for many programs, including most of the educational programs funded through Proposition 98. Over the past 26 years, actual school funding has been higher than the workload–based simulation 13 years and lower the other 13 years. Over the long term, schools have not received notably more or less than they would have received under this traditional budgeting approach.

Proposition 98 Funding Has Grown at Roughly the Same Pace as the Non–Proposition 98 General Fund Budget. Another way to assess the impact of the Proposition 98 formulas is to compare growth in K–12 Proposition 98 funding with growth in the rest of the state General Fund budget. From 1988–89 through 2014–15, Proposition 98 school funding generally tracked with the rest of the state General Fund budget. Over that 26–year period, school funding grew more quickly half the time and less quickly half the time. On a cumulative basis (growth from 1988–89), school funding was sometimes lower and sometimes higher. For example, through 2011–12, growth in school funding was lower—having grown by about 240 percent compared to 250 percent for the rest of the state General Fund budget. By comparison, through 2014–15, school funding had grown over the entire period by about 350 percent compared to about 300 percent for the rest of the state General Fund budget. These comparisons tend to favor schools during economic expansions—when the constitutional formulas require schools to receive large funding increases—but are less favorable to schools during economic downturns—when constitutional formulas result in lower school funding guarantees.

Proposition 98 Funding Has Grown Somewhat Slower Than Total Non–Proposition 98 Funding. We also compared K–12 Proposition 98 funding with growth in non–Proposition 98 funding from both the General Fund and special funds. Including special funds has the advantage of taking into account certain significant General Fund–related actions, such as the 1991 realignment (in which sales tax revenue that otherwise would have been treated as General Fund was deposited into a special fund). From 1988–89 through 2014–15, Proposition 98 school funding generally has grown somewhat slower than the rest of the budget. Specifically, school funding had grown about 350 percent over the entire period compared with non–Proposition 98 General Fund and special fund growth of about 380 percent.

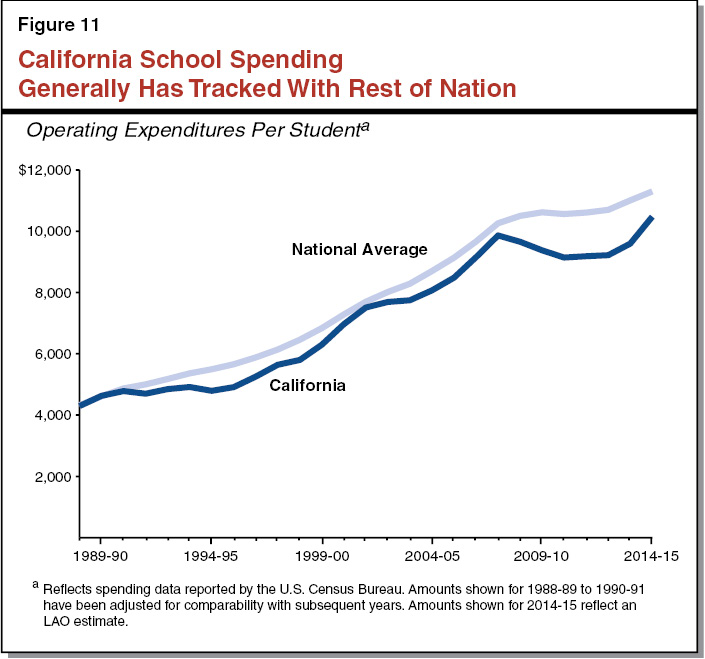

School District Spending in California Generally Has Tracked With Rest of Nation. We also examined how K–12 per–student spending in California has grown compared with the rest of the nation. For this analysis, we relied upon operating expenditures per pupil, a measure that reflects spending on salaries, supplies, and other program expenses but excludes capital outlay. This measure is collected consistently across the states. As shown in Figure 11, California school spending was very close to the national average when voters approved Proposition 98. Since that time, school spending in California has grown at about the same pace as the rest of the country. In 2014–15, we estimate that California schools spent about $10,500 per student. This level is about $800 (7 percent) less than the national average of $11,300 per student. Given a large increase in state funding in 2015–16 and 2016–17, we expect per–student spending in California has gotten closer to the national average during the past two years. (National data for these two years was not available prior to release of this report.)

Lessons Learned

We believe the state can glean three important lessons from its historical experience with Proposition 98. Below, we discuss each of these lessons.