LAO Contact

January 12, 2017

Improving the State’s Approach to Park User Fees

Executive Summary

User Fees Important Revenue Source for State Parks. The state park system, managed by the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), contains nearly 280 parks and serves about 70 million visitors each year. The parks cost over $400 million a year to operate. These costs are mainly supported by the state General Fund and revenue generated by the parks, including roughly $100 million in fees paid by park users for day use, camping, and special events.

Lack of Statewide Policy Framework for Setting Fees Leads to Disparities. Statute authorizes DPR to collect user fees for the benefit of state parks and allows the department to determine the level of fees it charges. Relying on user fees to help fund park operations makes sense because park users receive direct benefits from visiting parks—such as recreational opportunities—and providing these benefits drives a significant portion of state operational costs. However, department headquarters and the State Parks and Recreation Commission provide park managers with only limited guidance on both the policies and process districts should use when setting user fees. This includes limited guidance on what specific factors to consider when setting fees, how to weigh different park goals (such as public access and resource preservation), and how frequently to reevaluate fee levels. Consequently, there is a wide range of fees throughout the park system even for parks within the same classification and same region.

These inconsistencies are problematic for a few reasons. First, since these inconsistencies can result in some park users being charged more than others in different areas of the state for similar experiences, it places a greater financial burden on the park visitors that pay more without any clear policy rationale for doing so. Second, the state probably does not collect the optimal amount of revenue since fee collection is concentrated among a smaller group of visitors rather than distributed across all visitors. Third, the variations in park fees can be confusing for the public if the reasons for differences are unclear or if park visitors do not know what to expect at different parks. Fourth, the absence of a standardized process for updating fees means that fee revenue might not keep up with cost increases, and opportunities for public input are inconsistent throughout the state.

LAO Recommendations. We make several recommendations to improve how state parks fees are determined and collected.

- Establish Legislative Fee Policy. In our view, a key decision for the Legislature to make is to broadly determine how it prioritizes the different goals of the state park system and, based on that assessment, establish what share of statewide park operational costs should be borne by users versus the General Fund (or alternative funding sources). On the one hand, the Legislature might view state parks primarily as a public benefit that all Californians should be able to easily access at low or no cost. This approach would imply lower fee levels and greater reliance on funding parks through the General Fund. On the other hand, it might decide to treat state parks more like an enterprise that should be more self–sufficient and funded by the visitors that benefit directly. This approach would imply that a relatively high share of park operations be funded by user fees. Historically, the Legislature has, in effect, viewed state parks as somewhere in the middle, with the parks receiving a mix of public funds and user fees. Ultimately, the share of costs that should be borne by park users is a policy decision about the state's priorities for the park system.

- Create Standardized Statewide Fee Guidelines. We recommend that the Legislature direct the commission to develop and regularly update fee guidelines to be implemented by state park districts in order to provide greater consistency throughout the state. In our view, these guidelines would need to be based on legislative direction related to the share of operations costs that should be borne by park users, as well as other legislative priorities. Specifically, we recommend that the fee guidelines (1) provide acceptable ranges for fees by park classification and include guidance for how districts should set their fees for individual parks within those classification ranges, (2) be required to direct park districts to consider the most cost–effective ways to collect fees in their parks, (3) take into consideration legislative direction on how to ensure public access, (4) allow for variable pricing fee structures, and (5) require the department to recover all costs related to special events in state parks.

- Design a More Uniform and Transparent Fee–Setting Process. We recommend that the Legislature specify a fee–setting process for parks that would be consistent statewide and provide greater opportunities for public input. Required changes should include (1) regular review of fees at each park, (2) a consistent process that provides opportunities for public participation, and (3) public reporting of fee schedules and changes.

Introduction

The state park system, managed by the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), contains nearly 280 parks and serves about 70 million visitors a year. These parks cost over $400 million a year to operate. These costs are mainly supported by the General Fund and revenue generated by the parks, including roughly $100 million in fees paid by park users for day use, camping, and special events.

As we discuss in this report, state parks do not have clear and specific statewide policies or processes for setting and collecting user fees. Instead, fees generally are determined independently by each park district (geographic cluster of parks that share resources), resulting in variation throughout the state. This variation has implications for meeting the state's goals for the park system, including generating revenue to support park activities, ensuring that the public has access to the state's natural and historic resources throughout the state, and preserving those resources for the future.

It is also likely that DPR's budget will be reshaped over the next few years, perhaps significantly. The department is currently undergoing a major reorganization, and a "transformation team" is updating many DPR policies. In addition, the department's main special fund, the State Parks and Recreation Fund (SPRF), is depleted due to several years of spending more from the fund than the amount of revenues being collected. Therefore, some changes to DPR's budget are likely to be necessary for the upcoming fiscal years.

In this report, we provide an overview of California's state park system—including its organization, budget, historical funding, and how it currently sets fees. Then, we discuss some of our findings related to how state parks set and collect fees from park users, and we discuss some of the inherent policy trade–offs with different choices involving fees, as well as limitations of the current process. Finally, we offer recommendations aimed at improving consistency, transparency, and oversight of state park user fees.

In preparing this report, we reviewed reports from DPR and outside sources, analyzed DPR statistical and budget data, toured several state parks, met with DPR staff and other stakeholders, and spoke with representatives and researchers from other states.

Back to the TopBackground

California Has One of the Largest State Park Systems

California's state park system consists of nearly 280 state parks that totaled more than 1.6 million acres of property in 2014-15. In terms of acreage, it is the second largest state park system in the U.S. (Alaska's state park system has 3.3 million acres.) California state parks receive more annual visitors than any other system. The number of people who visit the state parks each year has remained relatively stable, averaging about 70 million visitors over the past 25 years.

State Park System Is Diverse

Many Types of Parks and Services. As shown in Figure 1, the state park system is quite diverse and includes beaches, museums, historical and memorial sites, forests, grass fields, rivers and lakes, and rare ecological reserves. The size of each of park also varies, ranging from 0.11 acres at Watts Towers of Simon Rodia State Historic Park to 600,000 acres at Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. In addition, parks offer a wide range of amenities including campsites, golf courses, ski runs, visitor information centers, tours, trails, fishing and boating opportunities, restaurants, and stores. Parks also vary in the types of infrastructure they maintain, including buildings, roads, power generation facilities, and water and wastewater systems.

Figure 1

The State Parks System Is Diverse

|

Park Classifications |

|

|

State Park |

88 |

|

State Beach |

62 |

|

State Historic Park |

52 |

|

State Recreation Area |

33 |

|

State Nature Reserve |

16 |

|

State Vehicular Recreation Area |

9 |

|

Other |

19 |

|

Total Units |

279 |

|

Assets |

|

|

Acreage |

1.6 million |

|

Campsites |

14,472 |

|

Miles of coastline |

343 |

|

Miles of lake and river frontage |

984 |

|

Miles of trails |

6,276 |

|

Recorded historic buildings |

3,000 |

|

Archeological sites |

10,000 |

|

Archeological specimens |

2 million |

|

Museum objects |

1 million |

Diversity Reflected in Department's Mission and Organization. Under existing state law, DPR is required to administer, protect, and develop the state park system, as well as ensure that the parks provide recreation and education to the people of California. The department is also required to help preserve the state's extraordinary biological diversity and its most valued natural and cultural resources. These statutory requirements reflect the goals of ensuring broad public access to parks for current residents and the preservation of state resources for future generations. To those ends, as we discuss in more detail below, DPR and the Legislature have sought opportunities for parks to generate revenue where appropriate in order to provide funding for a higher level of service than would be possible with only public funds. The department has a wide range of staff to support its multifaceted mission—including rangers, lifeguards, interpreters, environmental scientists, pest control specialists, foresters, historians, architects, engineers, archeologists, restoration specialists, curators, photographers, and administrative support staff.

The system is divided into 22 districts, which are further divided into 68 sectors. Districts vary in size. The smallest district by total operating costs is the Twin Cities District, which spent $5.6 million in 2014-15. The largest district is the Orange Coast District with operating costs that were roughly four times that amount ($22 million). Each district is led by a district superintendent who is overseen by department headquarters based in Sacramento. Department headquarters also determines district budget allocations and provides certain statewide services such as marketing, local assistance grants, facilities management, and planning.

The State Parks and Recreation Commission establishes general policies for the guidance of the department. The commission consists of nine voting commissioners appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate, as well as two nonvoting ex-officio members appointed by the Speaker of the Assembly and the Senate Rules Committee.

Commission Classifies Parks Based on Goals and Features. To help manage the park system's diverse assets, parks are classified based on their mission and features. Each classification has different rules governing park management and development. The major classifications are:

- State Parks. State parks (the most general classification that includes the largest number of parks) are relatively spacious scenic areas that oftentimes contain significant historical, archaeological, ecological, or geological features. The purpose of state parks is to preserve these elements and provide access to the most significant examples of the various ecological regions of California, such as the Sierra Nevada, coast, redwoods, foothills, and desert. The department may undertake improvements at state parks to provide for recreational activities—including camping, picnicking, sightseeing, hiking, and horseback riding—so long as those improvements do not involve any major modification of land, forests, or waters.

- State Recreation Areas. State recreation areas are developed and operated to provide outdoor recreational opportunities. Of all the park classifications, they allow the broadest range of recreational activities. In addition to the activities provided at state parks, state recreation areas can also be developed for swimming, bicycling, boating, waterskiing, diving, winter sports, fishing, and hunting. State recreation areas may be established in inland areas of the state.

- State Beaches. State beaches are very similar to state recreation areas except that they are located in coastal areas. They are developed for the same recreational opportunities.

- State Historic Parks. State historic parks are established primarily to preserve objects of historical, archaeological, and scientific importance. Any development at state historic parks must be necessary for the safety or enjoyment of visitors, such as to provide access, parking, water, sanitation, education, or picnicking.

- State Nature Reserves. State nature reserves are selected and managed for the purpose of preserving their ecology, unique habitat, geological features, and natural scenery. Development is kept minimal and is allowed only to provide visitor access and education.

- State Vehicular Recreation Areas (SVRAs). SVRAs provide off-highway vehicular trails and recreation. They are operated by the Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation Division, which has its own funding sources that are separate from funding for other state parks.

Campsites Also Classified by Features and Amenities. There are almost 15,000 campsites within the state park system. Similar to park units, campsites have different classifications. However, these classifications are typically applied to a specific campsite rather than an entire campground or park unit. Campsite classifications generally reflect the level of amenities offered and the features of a site. For example, so-called "primitive" sites might be more remote and provide little more than a clearing for your tent. "Developed" campsites have more amenities that can include vehicle access, fire pits or fire rings, showers, and a water supply. "Camper hook-up" sites often include electrical and water hook ups for campers or motor homes as well as dump stations to dispose of sewage. "Premium" sites often include a unique feature, such as ocean views.

Parks Operations Supported by Multiple Funding Sources

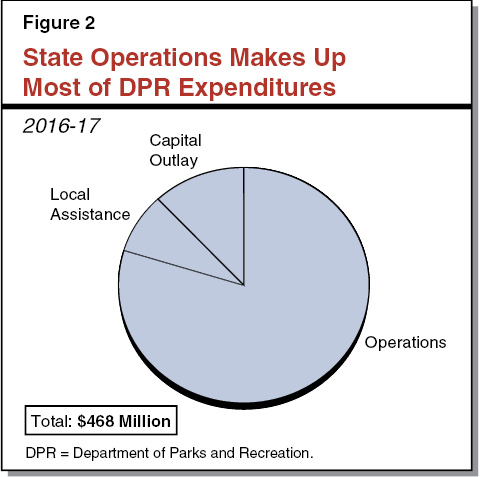

Operational Funding Supports Ongoing Park Activities. The 2016-17 budget provides a total of $468 million for state parks, including $374 million for state operations. (For the purposes of this report, figures do not include the divisions of Boating and Waterways and Off-Highway Vehicles within DPR because they are funded differently than the rest of the department.) Park operations are ongoing activities necessary to run the park system, including staffing, management, maintenance, fee collection, and administration. Other activities performed by DPR, such as capital outlay projects and grants provided to local governments, are not considered part of park operations. As shown in Figure 2, most DPR spending in 2016-17 is to support state operations.

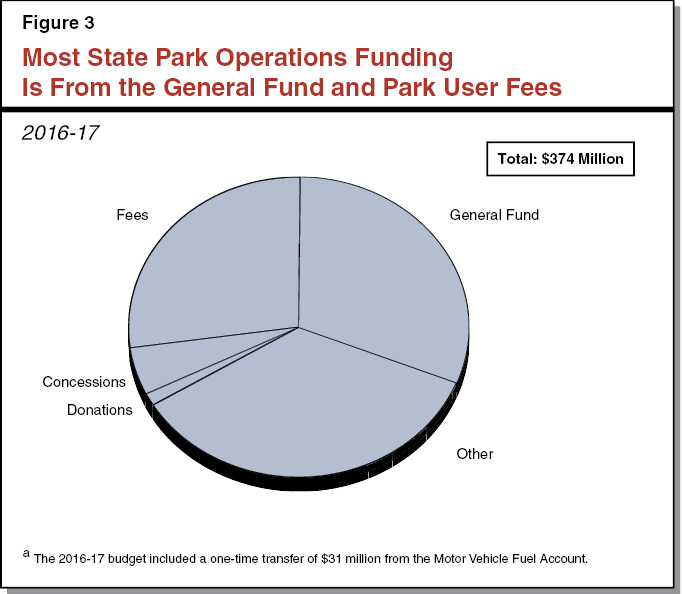

General Fund and Fees Are Main Funding Sources for Park Operations. Park operations is funded from several sources. As shown in Figure 3, about one third is funded from the General Fund, and one quarter comes from park user fees. Other funding sources for state park operations include revenue from fuel taxes, federal highway dollars for trails, the cigarette surtax, and various special funds designated for natural resource habitat protection.

Revenue Generated by Parks Deposited Into Parks Special Fund. Individual parks generate revenue primarily from park user fees and concession agreements. Park users pay fees to enter state parks, as well as for parking and specific recreational activities, such as the use of overnight campsites. Parks also receive revenue from contracts with state park concessionaires that provide certain services at state parks, such as restaurants, rentals, or gift shops. Revenues from park user fees and concession agreements are deposited into SPRF, which is administered by DPR. In general, about two-thirds of revenue and transfers to SPRF is from park user fees. The other third is mostly revenue from concessionaire agreements and motor vehicle fuel tax revenue.

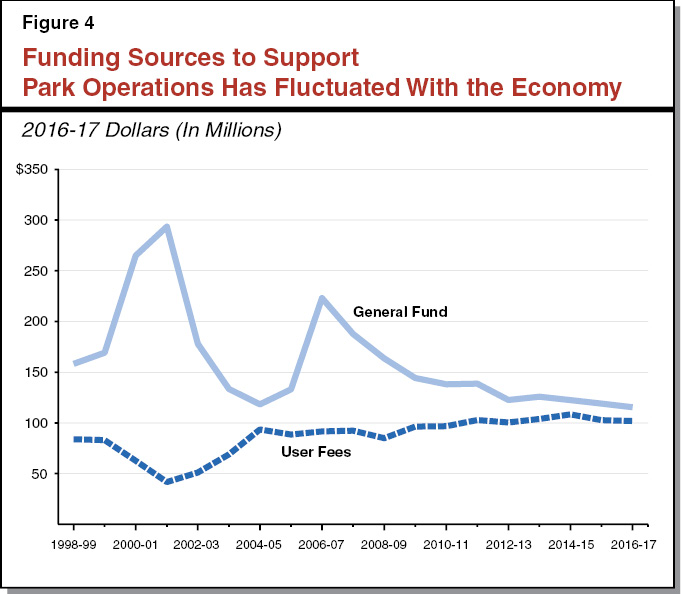

Funding Has Fluctuated With Economy Over Past 20 Years. Historically, the mix of funding sources used for state parks has fluctuated significantly, in large part depending on the state's overall General Fund situation. As shown in Figure 4, General Fund support for parks increased by 80 percent in 2000-01 when California experienced a large budget surplus. In response, DPR reduced day use and camping fees by half, and overall fee revenues declined by about a third. A few years later when state finances were not as strong, General Fund support for parks was reduced and user fees were increased close to their prior levels. Then, in 2005-06, when the economy had recovered, the Legislature increased the department's General Fund appropriation, including for ongoing activities as well as a one-time allocation to address deferred maintenance. However, following the beginning of a recession in 2007-08, General Fund support was reduced several times. Moderate increases in fee revenue since 2007-08 have partially offset this General Fund reduction. As shown in Figure 4, the current level of General Fund support for state park operations is lower and fee revenues are higher than they were 20 years ago when adjusted for inflation.

Bond Funding Frequently Used to Build Park System. In addition to funding for park operations, the state has provided support for capital outlay in order to acquire and develop park lands. The expansion and development of California's state park system has generally been financed with bond funding and General Fund dollars. About $1.2 billion in bond funding for parks has been approved since 2000. The state General Fund typically pays for general obligation bond debt service—including for both the principal and interest costs—over a couple decades.

How User Fees Are Established and Collected

Different Types of User Fees. State parks collect fees from park users for various activities. The most common type of fee is a "day use" fee, which is charged for entering the park or parking in lots owned by state parks. Only about half of state parks charge a day use fee. The department also offers visitors the option of purchasing annual passes to enter certain state parks. The second most common type of fee is for camping or other overnight accommodations. Parks also charge entities fees for holding special events on park property, such as fund-raisers or weddings.

DPR Has Authority to Implement and Set User Fees. Statute authorizes DPR to collect user fees for the benefit of state parks and allows the department to determine the level of fees it charges. While DPR headquarters provides some general guidance and ultimately must approve fee schedules, most decisions on fees and fee levels are determined at the park district level. Consequently, fee levels vary across the state. For example, when determining fees for special events, headquarters has directed districts to "recover costs." However, each district determines which costs are attributable to an event and how to charge for them. Since districts interpret "cost recovery" in different ways, there are varying special event fee levels throughout the state.

Most Park Visitors Do Not Pay Day Use Fees. The department estimates that of the 68 million park visitors in 2014-15 (not including campers), about two-thirds did not pay day use fees. (We note that there is some uncertainty with this estimate because of data challenges.) The large number of unpaid park visitors is due to several reasons. First, as indicated above, about half of the parks do not charge a day use fee at all. In some cases, this is due to difficulties collecting fees because of the park's physical set up. For example, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park is an urban park with many entry points where visitors can walk onto the grounds. Second, many parks charge only for parking, so visitors that walk, bike, or take public transportation into a park do not pay fees. For many parks, there is public parking available on nearby streets that park visitors can utilize and walk into the park for free. Third, some groups—such as veterans, the elderly, and school groups—can get fee exemptions. Many visitors to Sutter's Fort State Historic Park, for example, are school groups, contributing to more than half of their visitors paying no day use fees.

Legislature Created Revenue Generation Program

State parks have historically relied on park-generated revenue to help support operations. In recent years, the Legislature has directed DPR to improve its revenue generation. Specifically, Chapter 39 of 2012 (SB 1018, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) directed DPR to maximize revenue generation activities (consistent with the mission of the department).

A major component of Chapter 39 is the District Incentive Program. This program sets annual revenue targets for each district based on how much revenue that district earned in the previous three years. If both the state as a whole and an individual district exceed revenue targets, half of the district's revenue earned above its target is allocated back to that district. The remainder stays in SPRF—in the Revenue Incentive Subaccount—to be used for specified purposes, including new fee collection equipment and projects to improve the experiences of visitors. A district that does not exceed its target does not receive an allocation under the program. In 2014-15 (the most recent data available), most districts exceeded their targets—only five fell short. However, it is unclear whether increased revenue for these districts was due to the revenue generation program or other factors (such as an improving economy—resulting in greater attendance and fee revenue). The average amount retained by each successful district was $333,000, which is roughly 3 percent of the average district's operating budget. Chapter 39 also created and transferred bond funds to the State Park Enterprise Fund to be used for infrastructure and facility improvement projects designed to increase revenue.

Back to the TopIssues With the Parks' Fee-Setting Policy

In reviewing state park user fees, we identify several issues that merit legislative consideration. Specifically, we find that (1) charging fees to park users is appropriate, (2) setting these fees requires consideration of trade-offs with other park goals, (3) the lack of a statewide fee policy framework can lead to disparities throughout the state, and (4) there is not currently a standard process to set or adjust fees. We describe each of these findings in more detail below.

Charging Fees to Park Users Is Appropriate

State parks often serve a variety of purposes. Some of these purposes directly benefit users while others benefit the general public. Most, however, provide a mix of benefits to both park visitors and the state.

Users Derive Direct Benefits and Drive Some Costs. Historically, the Legislature has recognized that park user fees are one appropriate source of funding to support state parks. User fees have traditionally played a significant role in supporting the park system, though the amount of park operations expenditures covered by fees has fluctuated over time. Relying on user fees to fund park operations makes sense. Park users receive direct benefits from visiting parks, such as recreational opportunities (like hiking and swimming). Moreover, providing these benefits drives a significant portion of state operational costs. For example, the provision of well-maintained trails, educational exhibits near points of interest, and restrooms at trailheads directly benefit park visitors. In addition, consumers typically pay for recreational activities and other services that provide direct benefits when offered by the private market.

Parks Also Provide Broader Public Benefits. Many valuable public resources—such as unique natural features, scenic landscapes, historical monuments, and wildlife habitat—are located in state parks. For example, Natural Bridges State Beach features a naturally occurring mudstone bridge that was formed over a million years ago and was carved by the Pacific Ocean over time. The park also provides habitat for nearly 150,000 monarch butterflies that migrate as far as 2,000 miles to the park. Another park, Hearst San Simeon State Historical Monument, contains publisher William Randolph Hearst's 115-room "Hearst Castle," designed by California architect Julia Morgan. These resources are an important part of California's cultural identity and history, and it is reasonable for some of the costs associated with preserving and maintaining these resources to be supported by a broader segment of Californians through public funding sources, such as the General Fund.

Most Park Services Benefit Both Individual Park Users and the Public. The majority of activities performed by state parks provide a mix of both individual and public benefits. For example, rangers patrolling the parks can provide assistance to park visitors but they also protect park resources from vandalism, theft, or other harm. It makes sense to pay for these activities with a combination of user fees and public funds.

User Fee Decisions Involve Trade-Offs With Other Park Goals

Fee Policies Affect the Balance of Revenue, Access, and Preservation Goals. The amount of funding that comes from visitors versus public funds depends on how the Legislature prioritizes the goals of (1) revenue generation to support park activities, (2) broad public access, and (3) the preservation of natural and historic resources. While these goals are sometimes complimentary, they can also sometimes conflict, resulting in trade-offs among them.

On the one hand, generating fee revenue helps to support the state park system and fund a wide range of activities and personnel that benefit visitors and the public. Fees can also influence which parks people visit and when they go. For example, charging lower fees during weekdays or the off-season can encourage users to visit parks when they are less crowded. Therefore, fee levels can provide superintendents with a tool to better distribute park demand in order to reduce overcrowding at popular parks during peak times and encourage visitorship at less visited parks or during slower periods. This can help support resource preservation goals at parks where high visitorship can strain natural habitat or infrastructure. It can also help improve public access by providing lower-cost opportunities to visit parks that are less popular or during off-peak times.

On the other hand, there are inherent trade-offs with park user fees. If fees reach a certain level, they can potentially reduce access to state parks, particularly for lower-income individuals and families. Moreover, the state has an interest in Californians visiting their natural and cultural resources, learning about their state's history, and having opportunities for outdoor recreation and associated health benefits. Keeping fees low encourages people of all income levels to visit state parks.

Amount of Revenue to Come From Visitors Is a Policy Choice. The share of costs that should be borne by park users is a policy decision about the state's priorities for the park system. There is not necessarily a "right" level of fees or share of costs that park users should pay. Instead, the Legislature must weigh revenue, access, and preservation goals to determine what fee levels best balance all three in order to further its priorities for the state park system.

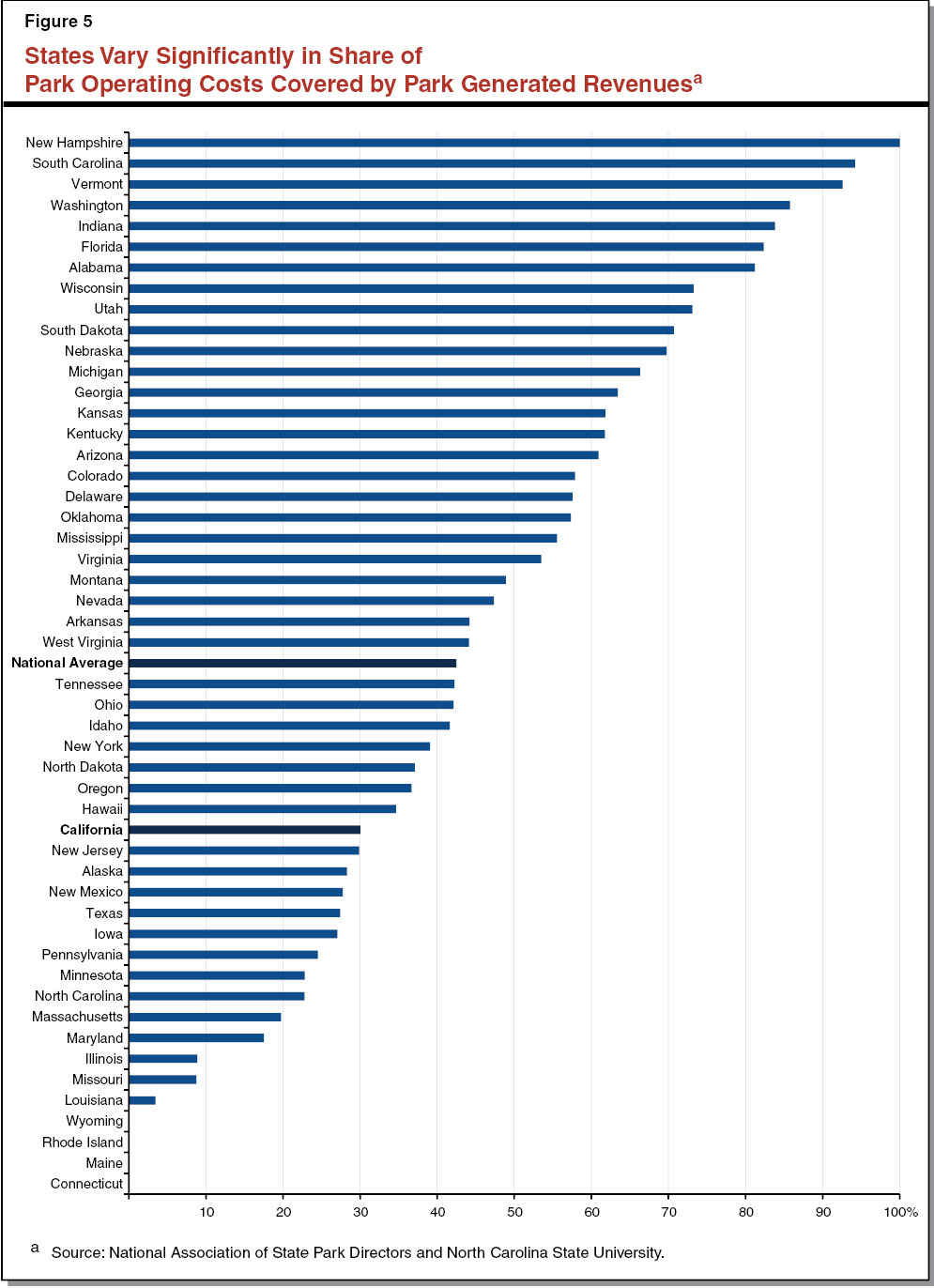

Most State Park Systems Are More Reliant on park-generated Revenue Than California. States have taken various approaches to the policy decisions inherent in determining the portion of operating costs that should be covered by park-generated revenue—including fees, as well as certain other revenue sources like payments from concessionaires. In one state—New Hampshire— park-generated revenue covers all of park operational costs. Other states—such as Iowa, Tennessee, and Kentucky—have no day use fees at all (although they do charge camping fees). However, most states fall somewhere in between, charging park users some amount of fees but not enough to completely cover all operational costs. In California, the share of operating costs covered by park-generated revenue has been about 30 percent in recent years. As shown in Figure 5, this was below the national average of 42 percent in 2014-15, ranking California 30th out of all the states.

Lack of Statewide Policy Framework Can Lead to Disparities

Currently No Clear Policy Framework. Department headquarters and the State Parks and Recreation Commission provide districts with only limited guidance on both the policies and process districts should use when setting user fees. This includes limited guidance on what specific factors to consider when setting fees, how to weigh different goals, and how frequently to reevaluate fee levels. Most department and commission policies are high-level and broad, leaving a lot of room for interpretation. Additionally, many policies are not binding, several years old, and often come in the form of memos. For example, the Parks and Recreation Commission's official statement of policy on fees is less than half a page long and has not been amended since 1994. Moreover, the majority of the commission's policies are optional, stating that the department may establish fees, fees may be adjusted annually, and that fees may be waived or reduced for certain groups or under certain circumstances. The department might provide park administrators some additional guidance in its Department Operations Manual (DOM), but at the time of publication we were not able to obtain a copy to review. However, based on our conversations, it did not seem like many administrators referred to the DOM when determining fees. This lack of clear guidance can result in variation on how individual parks and districts implement fees across the state.

Differing Approaches Have Resulted in Inconsistencies. Based on our conversations with various district and park administrators, the lack of updated and specific fee policies has resulted in different interpretations of how park fees should be set and adjusted. They reported taking different factors into account when making fee-setting decisions, including visitorship, costs to collect fees, fee levels at nearby parks, and potential local opposition to new or increased fees. Some parks also give major consideration to local permitting requirements and historical fee levels. For example, some state beaches have had difficulty implementing new fees or fee increases due to local resistance and challenges in getting approval from the Coastal Commission. How park administrators weigh these different factors can significantly affect final fee decisions. For example, districts that prioritize public access and high visitorship would be more reluctant to increase fees. Other districts prioritize wanting to help support the park system financially and do not think fees have a significant impact on their visitorship. Consequently, they are more willing to increase fees or implement new fee structures such as hourly rates.

As a result, there is a wide range of fees throughout the park system even for parks within the same classification and same region. For example, day use fees can range from free entry to $15 for Southern California beaches. Similarly, camping fees range from $5 to $35 per night for primitive campsites (those with limited amenities) and from $25 to $75 for camper hook-ups. Figure 6 displays the range of fees for different categories of parks and camp sites.

Figure 6

Wide Range of Fees Within

Park Classificationsa

|

Lowest Fee |

Highest Fee |

|

|

Day Use Fees |

||

|

State Park |

$0 |

$15 |

|

State Recreation Area |

0 |

12 |

|

State Beach |

0 |

15 |

|

State Historic Park |

0 |

12 |

|

State Nature Reserve |

0 |

15 |

|

Museum |

0 |

8 |

|

Camping Fees |

||

|

Primitive |

5 |

35 |

|

Primitive (boat-in) |

20 |

75 |

|

Developed |

10 |

45 |

|

Premium |

35 |

60 |

|

Camper hook-up |

25 |

75 |

|

Cabin |

56 |

225 |

|

aDoes not include some parks or facilities operated by state park partners. |

||

Variation Can Affect Achievement of Statewide Goals. Since these differences can result in some park users being charged more than others in different areas of the state for similar experiences, it places a greater financial burden on the park visitors that pay more without any clear policy rationale for doing so. This can potentially reduce public access to more expensive parks for some users. Moreover, the state probably does not collect the optimal amount of revenue since fee collection is concentrated among a smaller group of visitors rather than distributed across all visitors. When fees are charged throughout the system more broadly, the state can collect the same amount of revenue while charging individual visitors lower fees since more people pay. The variations in park fees can also be confusing for the public if the reasons for differences are unclear or if park visitors do not know what to expect at different parks.

Lack of Standard Process to Set or Adjust Fees

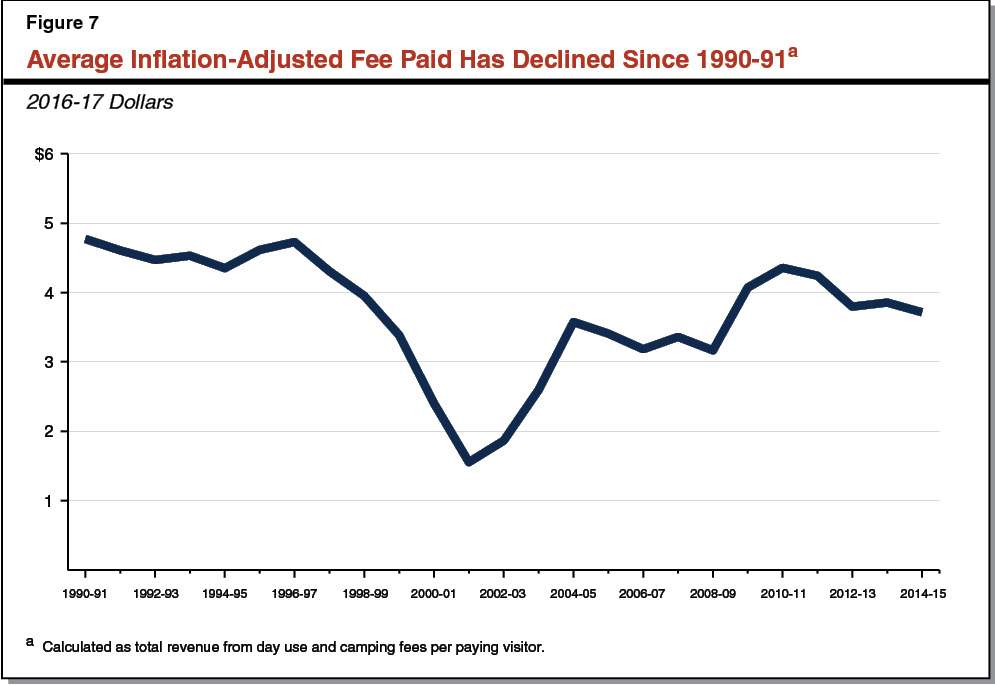

No Regular Review of Fees Required. As described above, while the commission's policy is that the department may adjust fees annually, there is no requirement for a regular review or adjustment of fees. Based on our review of past fee schedules, it appears that the vast majority of parks have not updated their fee levels in at least five years. This has resulted in fees not keeping up with inflation and other cost increases. As shown in Figure 7, there has been significant variation in fee revenue—such as the above-mentioned reduction in fee levels in 2000-01—but the average fee for paying visitors has declined by 22 percent since 1990-91 when adjusted for inflation. Over time, this has eroded the total level of resources available to support state parks since expenses have risen with inflation.

Public Process Not Always Included. There is also variation in the process by which parks adjust fees when they choose to do so. Most importantly, public input is not always sought. For example, some districts reported that they have formal hearings to solicit public input while others do not. Consequently, the public and Legislature might not be aware of potential changes in fees that are being considered until after the decision is made by the department. This reduces transparency and limits opportunities for public and legislative input. In addition, a less public process limits the opportunity of a park to provide the public with a clear rationale for a fee change, which could affect public support for proposed fee changes.

Back to the TopLAO Recommendations

Based on our above findings, we make several recommendations below to improve how state parks fees are determined and collected. First, we recommend that the Legislature establish a clear fee policy that would include a determination about how much of state operational costs should be borne by park users. A more explicit policy would provide clear direction about how the different goals of state parks should be balanced. Second, we recommend that the Legislature direct the commission to create more standardized statewide guidelines for districts to use when determining fee amounts. This would provide the department with a framework that can be applied to achieve more consistent fee decisions statewide. Third, we recommend designing a more uniform and transparent fee setting process for DPR headquarters and park districts. This can help ensure that similar steps are taken to determine fees across the state.

Establish Legislative Fee Policy

Determine Policy View of State Parks: How to Balance Public Benefit Versus Enterprise. In our view, a key decision for the Legislature to make is to broadly determine how it prioritizes the different goals of the state park system. This decision would then guide subsequent fee policy decisions. On the one hand, the Legislature might view state parks primarily as a public benefit that all Californians should be able to easily access at low or no cost. This approach would imply lower fee levels and greater reliance on funding parks through the General Fund (or alternative funding sources). On the other hand, it might decide to treat state parks more like an enterprise that should be more self-sufficient and funded by the visitors that benefit directly. This approach would imply that a relatively high share of park operations be funded by user fees. Historically, the Legislature has, in effect, viewed state parks as somewhere in the middle, with the parks receiving a mix of public funds and user fees.

Weigh Public Funding for Parks Against Other Budgetary Priorities. In addition to considering its goals for state parks, the Legislature will want to consider the implications of different park fee levels for its other priorities in the state budget. Since DPR's main sources of funding are park-generated revenue and the General Fund, subsidizing park fees and service levels must be weighed against other General Fund priorities. Even if public access to parks is a high priority, it can cost the General Fund and therefore must be weighed against other demands like education, criminal justice, and health care.

Determine Share of Costs to Be Covered by Fees. We recommend the Legislature adopt a policy that designates what share of parks operations costs should be covered by user fees. This should be informed by the Legislature's broader consideration of the extent to which it views parks as a public benefit versus enterprise. (We have recommended a similar method in the past for determining fee levels in the state's university system.) We find that this approach would have a couple of advantages over current practice. First, it would give the park system as a whole clear policy direction about what amount of fee revenue should be the goal for the department each fiscal year. Second, a share of cost approach could better ensure that the Legislature's desired funding mix for parks is maintained over time. As operations costs rise due to inflation and increases in wages, the amount of revenue parks must earn in order to maintain the target funding makeup would also increase. This can serve as a clear signal to the department when fees need to be reevaluated. It would also be clear how much General Fund support needed to be adjusted each year. Third, our recommended approach would require DPR and stakeholders to consider the potential impact on fees and the General Fund when considering program expansions or other activities that would result in increased expenditures for operations.

Consider How Best to Transition to Share of Cost Approach. There are a couple of important considerations for the Legislature should it choose to transition to the share of cost approach that we recommend. First, the Legislature would want to be clear in its policy whether the share of operational costs to be borne by users is the share of (1) direct visitor-driven costs or (2) all operational costs. Importantly, the costs that are driven directly by park visitors is not currently reported by DPR. The department might need to reach out to districts and staff in the field in order to come up with a reliable estimate of these costs. We would note that the department is currently undertaking an effort to improve its accounting of operational costs that might help such an effort.

Second, the Legislature would want to consider how quickly it wants to transition the parks budget to a share of cost approach. It would also be important to allow sufficient time for guidelines to be developed and for individual parks to review and adjust their fees accordingly, as discussed in more detail below. In addition, if park-generated revenue needs to increase substantially in order to cover the desired portion of costs, the Legislature might want to consider strategies to lessen the immediate impacts on park users and visitorship. This could include, for example, phasing in fee increases over time. Conversely, if park-generated revenue needs to decrease because it covers more than the desired portion of costs, the Legislature would need to determine other funding sources to backfill the reductions in fee revenue.

Provide Incentives for Districts That Align With Legislative Goals. The Legislature can design an incentive structure that helps support its goals. This would be particularly important if the Legislature decides that an increased share of costs should be covered by fees. We find that the current incentive for park managers to generate revenue is relatively weak because individual parks do not retain much of their revenue locally under the current revenue generation program. While park districts are able to retain some revenue under the program, the amount retained is often small relative to their operating budgets and is uncertain since it depends on both districts and the overall park system meeting its set targets. Moreover, there is frequently local opposition to increasing fees, and doing so could potentially decrease visitorship to the park in the short term. Accordingly, if the Legislature still wants to pursue the revenue generation goals in statute, we recommend that it consider modifying the current revenue generation incentive program to allow park districts to retain a specified share of locally generated park revenue. Better fiscal incentives could encourage more creativity at the district level for increasing revenues. Some examples seen in Southern California include permitting new special events like concerts and running races, establishing hourly parking, and developing innovative amenities and concessions such as a wine bar on the beach. Allowing districts to retain a share of the revenue they earn can also increase public support for fees since the link between the fees paid by visitors and the improvements to the park is clearer.

However, the percentage retained would be based on how strongly the Legislature wants to incentivize districts to generate revenue. If the Legislature wants state parks to be more self-sufficient and increase revenues, the stronger fiscal incentive provided by a higher percentage would make sense. If the Legislature views state parks as more of a public benefit and prefers to support them with public funds rather than user fees, then a weaker incentive and lower percentage would be more appropriate. In the long run, the Legislature could adjust the percent of local revenues retained by each district higher or lower to the extent that park revenues were falling below or exceeding the statewide share of cost target. For comparison purposes, under federal policy, national parks generally retain 80 percent of their locally generated revenues.

We note that allowing districts to retain more of the revenue earned within their district would have trade-offs. It would reduce the department's flexibility to direct funds around the park system to its highest priorities, and it would leave less revenue available to direct to those parks that have less ability to earn revenue. We find, though, that if implemented effectively, this approach could generate more funding for the parks system overall, including for those other priorities and lower-revenue parks.

Create Standardized Statewide Fee Guidelines

We recommend that the Legislature direct the commission to develop and regularly update detailed fee guidelines to be implemented by state park districts in order to provide greater consistency throughout the state. In our view, these guidelines would need to be based on legislative direction related to the share of operations costs that should be borne by park users, as well as other legislative priorities. We discuss issues the Legislature might wish to consider related to these guidelines in greater detail below.

What Fee Amount Should Be Charged for Each Type of Park? We recommend that the fee guidelines (1) provide acceptable ranges for fees by park classification and (2) then include guidance for how districts should set their fees for individual parks within those classification ranges. Parks classifications that focus on recreational activities, have high levels of development, and offer a lot of amenities (such as state recreation areas and state beaches) should generally charge higher user fees since they provide more benefits directly to visitors and visitors' activities can drive more of their costs. Conversely, historic parks or nature preserves that focus on resource preservation should have lower fees since most of their activities provide benefits to the broader public.

Once ranges are determined for each classification, we further recommend that the guidelines provide instruction for how parks set their fees within their classification ranges. In particular, we expect districts to set fees at individual parks based on the level of amenities provided and operational costs at those parks relative to other parks in the same classification. For example, a state beach with only a parking lot and small access trail might have a day use fee at the low end of the range, and one with rentals, restaurants, modern restrooms, and other accommodations would be at the higher end. Likewise, it makes sense for camping fees to be higher at highly developed types of campsites and lower for the types of sites with fewer amenities.

We find that this approach would provide for more consistency across the parks system, be fairer to visitors of similar parks, and spread costs borne by visitors more evenly across the state. At the same time, this approach would provide flexibility in acknowledgment that parks do have significant diversity even within the same classifications and would allow them to take other factors into account such as what visitor amenities are provided and comparisons to what fees are charged at nearby state, local, and regional parks.

How Should Users Be Charged Day Use Fees? We recommend that the guidelines direct park districts to consider the most cost-effective ways to collect fees in their parks. In particular, some parks could benefit from instituting per-user day use fees in place of or in addition to relying on parking fees. As discussed above, about two-thirds of park visitors do not pay any day use fees. In part, this is because many parks charge day use fees by vehicle, and visitors can often avoid payment by simply parking elsewhere and then walking into the park. However, visitors that walk in for free generate many of the same costs and receive many of the same benefits as visitors who drive into the park. Therefore, charging a per-user fee instead could better ensure that all visitors pay their fair share of fees. Additionally, increasing the number of visitors that pay fees can lower fee levels for everyone while providing the same amount of revenue. Lower fees also could help improve public accessibility. However, collecting a per-user fee is not always possible or efficient. For example, it could be difficult at parks that have several entrances. It could also be difficult where stakeholders are not supportive of a per-user fee, resulting in low payment compliance unless there is adequate enforcement.

One park that has implemented per-user fees fairly successfully is China Camp State Historic Park in San Rafael. In our discussions with staff at the park, they reported they believed their compliance was relatively high and that most users paid the fees. Importantly, they felt that their high compliance rate was partially due to public education campaigns and buy-in from users that want to support their local state park. Without visitor support, collecting per-user fees could be much more challenging and costly. Where collecting per-user and vehicle fees is not as feasible, other revenue-generating options could include increasing collections through concessionaires or charges for services. The commission's fee policy should allow flexibility for varying collection methods based on local constraints and opportunities, as well as the costs of collection.

Should All Users Pay the Same Fees? To the extent that the Legislature wants to ensure that certain user groups have affordable access to state parks, it could consider directing the commission to incorporate reduced fees and fee exceptions into the guidelines. For example, in the past the Legislature has determined that student groups should generally not be required to pay day use fees. The Legislature could also direct the department to offer more park-specific annual passes (as opposed to just the system-wide and few regional passes available currently), which are generally cheaper for local users that visit the same park frequently. However, it is important to note that fee exceptions and discounts have trade-offs and should probably be used selectively. They result in reduced fee revenue, meaning either less money for parks, increased fees on other visitors, or the necessity for more General Fund support to sustain the same level of operations.

When Should Different Fees Be Charged? We recommend that the guidelines allow for variable pricing fee structures. For example, the department should be encouraged to implement peak demand pricing and hourly parking rates where feasible. Hourly fee rates make sense at parks where visitors only want to spend a few hours, such as local residents visiting nearby parks. Peak demand pricing makes sense at parks that are busy during a peak season or on weekends but have lower visitation during off times.

Allowing such variations in fees is currently utilized in a few places in the state park system, and its expansion could have several advantages. First, variable pricing can potentially improve access by helping reduce overcrowding and providing lower-cost opportunities to visit parks during off-peak times. Second, it can help increase visitorship and improve the visitor experience by better distributing demand from times when the park is crowded to times that have historically been less busy. Third, it can increase revenue if more people visit the park than otherwise would or pay to park in a lot during an off time that might be full during peak times.

It is worth noting, however, that variable pricing has trade-offs. It can be unpredictable for visitors who might end up facing unexpectedly high prices if, for example, they arrive on a high-demand day. Also, variable pricing might require special equipment to collect, which can drive additional costs. Therefore, it would be important for park administrators to assess the likely long-term effects on revenue and costs at their individual parks before investing in new equipment.

How Much Should Be Charged for Special Events? We recommend that the guidelines require the department to recover all costs—including indirect and facility-related costs-related to special events in state parks. Special events—such as corporate events, weddings, and fund-raisers—are not as related to broad public access to the state's cultural and natural resources as day use and camping. Therefore, in our view, it generally does not make sense for the state to subsidize them through the General Fund.

Design a More Uniform and Transparent Fee-Setting Process

We recommend that the Legislature specify a fee-setting process for park districts and DPR headquarters that would be consistent statewide and provide the public with notification and opportunities for input.

Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature require that parks take the following steps to adjust fee levels. First, parks should be required to review and consider fee changes on a regular cycle, perhaps once every three years. This would ensure better consistency and that fee levels keep up with inflation and other cost pressures. It would also allow any changes in legislative direction or fee guidelines to be incorporated in a timely manner. Second, public participation could be enhanced by requirements for public notification and public hearings when fee changes are being considered. Third, we recommend that headquarters continue to be required to approve final fee schedules to ensure compliance with any enacted guidelines and policies. Fourth, transparency could be enhanced by requirements that (1) information on fee schedules and changes to those schedules be posted on the department's web page for each park and (2) the department report on enacted fee changes as part of its annual statistical report.

Back to the TopConclusion

In this report, we make several recommendations to help ensure that park fees reflect statewide priorities for the park system. Specifically, we recommend (1) establishing a legislative fee policy, (2) creating standardized statewide guidelines for determining fee amounts, and (3) requiring a consistent and more transparent fee-setting process. We find that implementing these recommendations would provide for more transparency, better reflect legislative priorities, and increase consistency across the parks system. If implemented well, these improvements would better ensure that sufficient revenues are generated to maintain and improve the natural and historic resources of the state parks system for all Californians now and in the future.