February 6, 2017

Re-Envisioning County Offices of Education:

A Study of Their Mission and Funding

Executive Summary

Mission

State Constitution Establishes Role of County in Schools. The State Constitution establishes county superintendents of schools. Today, each of the state’s 58 counties currently has its own superintendent. County superintendents and their staff commonly are referred to as county offices of education (COEs).

State Law Tasks COEs With Some Specific Responsibilities. The state gives COEs a role in alternative education (designed for students who require or could benefit from a nontraditional school setting). Specifically, state law requires COEs to ensure that students incarcerated at county jails receive an education. To this end, most COEs receive state funding to operate juvenile “court schools.” The state also funds COEs to serve students who are on probation, referred by probation departments, or mandatorily expelled. COEs commonly serve these students at “county community schools.” Other types of at‑risk students (such as those who are nonmandatorily expelled) are served by school districts. In addition to assigning them a role in alternative education, the state tasks COEs with two core district oversight activities—review of districts’ budgets and academic plans.

COEs Vary Greatly in the Optional Services They Provide. COEs offer various other services not required by law, such as business and legal services for districts, teacher training, and regional career technical education programs for students. The type and amount of optional services COEs provide depends on the size of districts in the county, their historic funding levels, and their superintendents’ priorities.

Funding

Recent Reforms Increased Funding, Reduced Responsibilities. In 2013‑14, the state adopted a new funding formula for COEs known as the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The new formula increased overall state funding for COEs and eliminated many of the responsibilities they formerly had under state categorical programs.

COE LCFF Is Composed of Three Elements. The COE LCFF provides funding directly to COEs for (1) students they serve at juvenile court schools and county community schools (totaling 30 percent of LCFF funding) and (2) services they provide to their districts (totaling 45 percent of LCFF funding). The remaining 25 percent of COE LCFF comes from “hold harmless” provisions that are based on the amount of funding COEs received for categorical programs before LCFF. The total funding provided through the LCFF is about $1 billion per year. COEs may use their resulting allocation under the formula for any purpose.

COEs Spend Less Than LCFF Provides on State‑Required Activities. In 2014‑15, LCFF provided COEs a total of $140 million statewide to serve juvenile court school students, but COEs reported spending about $100 million. LCFF provided COEs a total of $183 million statewide to serve students at county community schools. Though data limitations prevented us from determining what COEs spent on these schools, we found large variation in their size, with smaller schools spending substantially more per student than larger schools. For required district fiscal and academic oversight, we estimate COEs spent about $40 million.

COEs Use Remainder of LCFF to Provide Optional Services. After paying for alternative education (an estimated $283 million) and their primary required district services (an estimated $40 million), COEs spent the rest of their LCFF allocations (roughly $650 million) on optional services.

Assessment and Recommendations

Allocate Alternative Education Funding to School Districts and Allow Them to Develop Local Arrangements With COEs. Providing funding directly to COEs for the alternative students they serve detaches these students from their home districts and creates limited incentives for districts to oversee the quality of education provided. To address these concerns, we recommend funding districts directly for all alternative students, including incarcerated students. For court schools, however, we recommend setting COEs as the default educational provider and setting a statutory reimbursement rate. This approach allows districts to select the court school provider that offers the most effective and efficient program, while still preserving the longstanding, productive relationships that many COEs have with county jails and probation departments. For their other alternative students, districts would select the most appropriate placement, much as they do now. These placements could be in district‑ or county‑run programs. To further encourage high‑quality service, we recommend assigning outcome data from COEs back to each alternative student’s home district.

Recommend Funding COEs Directly for Core Oversight Activities. Given there are more than 900 districts in California, we think COEs can perform district oversight more effectively and efficiently than a state entity. Accordingly, we recommend COEs receive funding directly for these state required activities.

Recommend Shifting Other Funding to Districts and Allowing Them to Purchase Services. COEs receive the same amount of LCFF funding regardless of how well they address district priorities. To address this concern, we recommend the Legislature shift the LCFF funding that COEs use to provide optional services to school districts. Our recommendation would allow districts to purchase services that best serve their students, whether from COEs or other providers.

Recommendations Would Clarify Mission and Funding for COEs. Taken together, our recommendations would help clarify what services all COEs should provide and align state funding to those activities. Because our recommendations entail major changes in the way the state funds COEs, we recommend the Legislature phase them in over several years.

Introduction

Despite assigning key tasks to county offices of education (COE) and providing a majority of their funding, the state has not undertaken a review of COEs for many years. Such a review is even more warranted today given the recent implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) for COEs. Implemented in 2013‑14, LCFF removed the strings associated with most COE funding while simultaneously increasing overall COE funding. It also expanded the role of COEs in overseeing districts’ academic programs. This report analyzes COEs’ changing responsibilities under LCFF and assesses how well state funding is aligned with these responsibilities. The report has four main sections. The first section provides background on COEs’ governance and mission. The second section focuses on COE funding and includes an analysis of how COEs are using their LCFF funds. The third section assesses COEs’ roles in the LCFF era, and the final section contains our recommendations for re‑envisioning COEs moving forward.

Background

In this section, we provide background on COE governance, give an overview of COEs’ mission, and describe the activities the state requires COEs to perform.

Governance

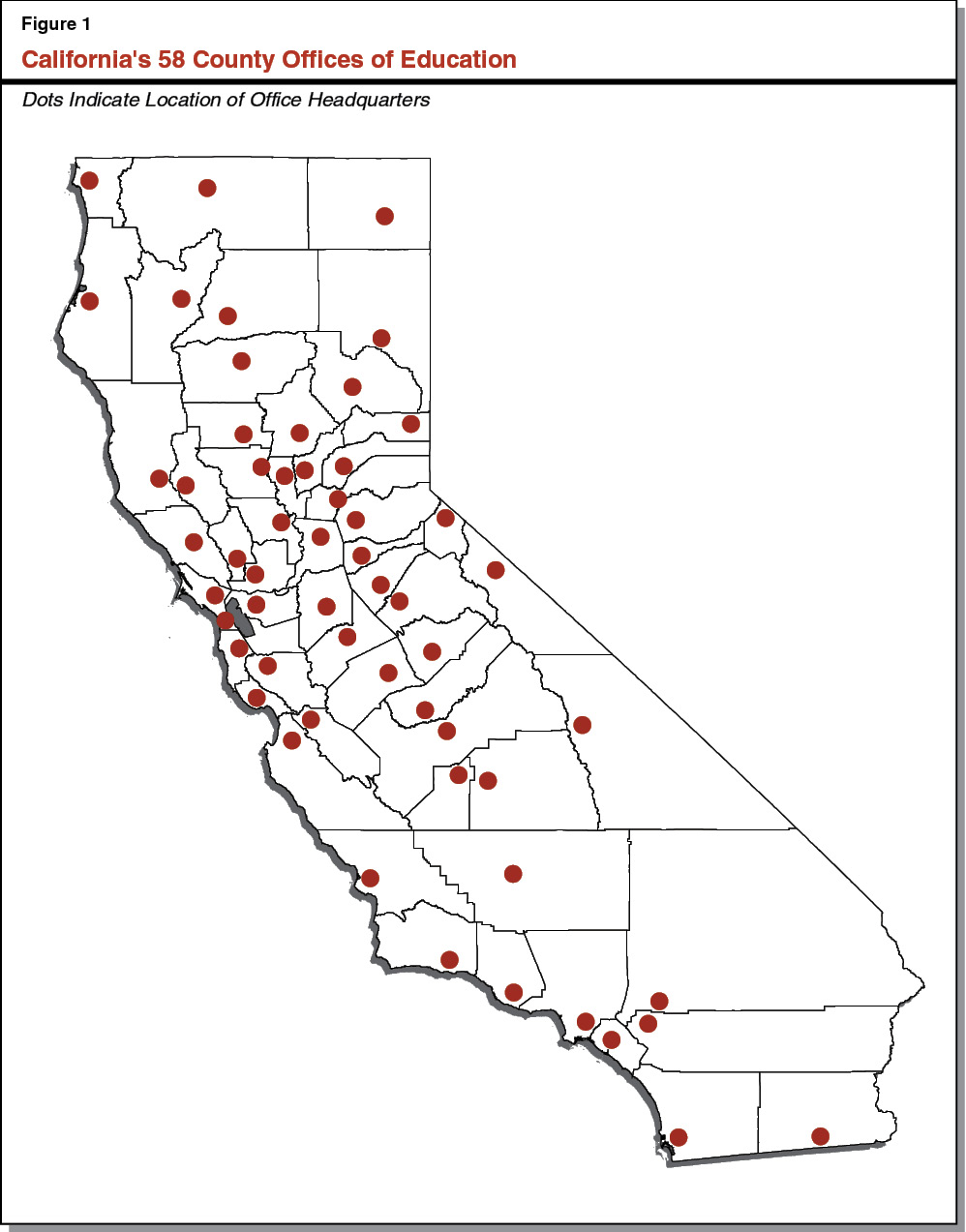

State Constitution Establishes Role of County in Schools. The State Constitution establishes county superintendents of schools. Though the Constitution allows two or more counties to unite for the purposes of selecting a superintendent, each of the state’s 58 counties currently has its own superintendent. The Constitution allows county superintendents either to be elected by voters in their counties or appointed by their county’s board of education. The Constitution authorizes voters to elect these county boards of education. State law requires these boards to consist of five or seven members representing different areas of the county. Currently, all but five county superintendents are elected rather than appointed by the boards. County superintendents and their staff are commonly referred to as county offices of education (COE). Figure 1 shows the central office for each COE in California. County superintendents manage the daily operations of these COEs.

Overview of Mission

County Boards of Education Have Certain Constitutional and Statutory Responsibilities. The Constitution gives county boards of education authority to set their county superintendent’s salary and state law tasks them with approving annual COE operating budgets. State law further tasks county boards of education with approving certain academic plans developed by the COE. County boards of education also effectively serve as an appellant body, hearing disputes among local groups that have been unable to be resolved at the district level. For example, a group can appeal to the county board of education if a district denies its application to open a charter school. Similarly, parents can appeal to the county board if their home district has expelled their child and they would like the decision overturned.

State Law Makes COEs Responsible for Some Alternative Education. State law gives COEs a role in alternative education, which refers to any nontraditional academic program designed for students who require or could benefit from an alternative placement. State law specifically makes COEs responsible for ensuring students incarcerated at the county level are provided with an educational program. State law also allows COEs to receive direct funding for educating students who are on probation, referred by probation departments, or mandatorily expelled. (State law requires students to be expelled if they commit certain violent or drug‑related offenses.) All other at‑risk students, including nonmandatorily expelled students, students referred by school attendance review boards, students with significant behavior issues, and students with serious academic deficiencies, are funded through school districts.

State Law Also Requires COEs to Serve and Oversee Districts in Specified Ways. The second column of Figure 2 shows all the services COEs are required to provide to districts within their jurisdictions. Most notably, state law requires COEs to review school districts’ academic and budget plans. It also requires them to support county boards of education in hearing appeal issues. Additionally, state law requires COEs to support districts in various other ways, including assisting them on certain pension and insurance‑related issues.

Figure 2

State‑Required and Optional Activities

|

Required |

Optional |

|||

|

Alternative Education |

District Services |

Common District Services |

Common Direct Instruction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aThese schools are unique in that COEs are not required to run them, but they receive direct funding for certain students (such as those on probation) if they do run them, and COEs are held accountable through the same LCAP process used for juvenile court schools. bCOEs are required to review the condition of facilities, availability of textbooks, and teacher assignments in designated low‑performing schools. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula and LCAP = Local Control and Accountability Plan. |

||||

COEs Historically Have Fulfilled Other Functions Voluntarily. As the next two columns of Figure 2 shows, COEs do many things not required by state law. Virtually all COEs provide one or more optional services to districts. Optional services they commonly provide include staff development, data support, and legal and business support. Many COEs also historically have applied for various state grants to provide direct student instruction. Most commonly, COEs have provided career technical education, child care and preschool programs, migrant education programs, and adult education. Many school districts historically have participated in the same state grant programs and also offered these forms of direct student instruction. As discussed in the nearby box, COEs also have a role in special education.

State Law Gives COEs Role in Special Education

In California, county offices of education (COEs) and school districts coordinate special education services through consortia known as Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs). All COEs are members of one or more SELPAs. At a minimum, this means COEs must attend SELPA meetings to discuss how to serve students with disabilities residing within their jurisdictions. Some COEs also provide direct services to students with disabilities. Others serve as their SELPA’s lead fiscal agent. In this capacity, COEs accept funding for all SELPA members, typically passing through a portion of this funding to other SELPA members while keeping some to provide services themselves. We do not cover special education in this report, as it was not consolidated into the Local Control Funding Formula for COEs and we believe any significant change to California’s system of special education should be part of a unified restructuring effort. Changing COEs’ roles in special education likely would have significant ramifications for the rest of the special education system.

COEs Vary Greatly in Terms of the Number of School Districts They Serve. In California, COEs have an average of 16 school districts within their jurisdictions, but the range is large. Los Angeles County has the most school districts (80). In contrast, seven counties (Alpine, Amador, Del Norte, Mariposa, Plumas, San Francisco, and Sierra) have a single district within their jurisdictions. Though each of these counties still has a county superintendent of schools and a county board of education, its COE typically functions more like an extension of the school district office. In recognition of these especially tight district‑county relationships, the California Department of Education (rather than the COEs) undertakes required oversight activities on behalf of the seven districts.

COEs’ Activities Vary Greatly Depending on the Size of Their School Districts . . . COEs serving many small districts historically have tended to be more involved in running regional academic programs (such as career technical education), covering basic business services (such as payroll and procurement), and providing support in various other administrative areas (such as data management and reporting). In contrast, COEs with many large districts within their jurisdiction have tended to focus more on supplemental and enrichment services, such as specialized professional development. For example, some COEs offer training to district staff on how best to incorporate digital learning into their classrooms.

. . . And Their Historical Funding Levels . . . Another particularly important factor affecting the type and extent of COEs’ activities relates to historical funding levels, with funding levels provided decades ago continuing to influence COEs’ activities. Most notably, higher‑funded COEs tend to provide a broader swath of optional district services.

. . . And Their Superintendents’ Priorities. COEs’ activities also vary according to their county superintendents’ priorities. Whereas some county superintendents traditionally have had an interventionist educational philosophy, with their COEs applying for many state grants and offering many optional services, other county superintendents’ traditionally have seen their mission more narrowly and limited their efforts to statutorily required activities.

Alternative Education

Many COEs Operate Juvenile “Court Schools.” COEs are required by state law to ensure students incarcerated or awaiting trial at county jails are educated. To this end, COEs may directly educate students at juvenile court schools or arrange for another provider to educate the students. In 2014‑15, 47 COEs (and one school district) operated court schools. Of these COEs, 39 operated one court school, 5 operated two court schools, and 3 operated more than two courts schools. Altogether, these schools served an average of 8,116 students per day (as measured by average daily attendance, or ADA). On average, each court school served 103 students per day. The cumulative number of students served in court schools throughout the year is much higher, as students often stay at these schools for short periods of time while they await trial.

COEs Also Typically Operate “County Community Schools.” State law designates COEs as a provider of education for students who are on probation, referred by a probation department, or mandatorily expelled from their school. COEs receive direct funding for these students, who typically are served at county‑run county community schools. (In cases where COEs do not operate county community schools, students receive another placement, such as a district‑run alternative school.) The state also allows COEs to enroll other at‑risk students in their county community schools. For these other students, COEs must develop local agreements under which the students’ home districts reimburse them for associated education costs. In 2014‑15, 51 COEs operated 76 county community schools serving an average of 18,335 students per day (ADA). Like juvenile court schools, the cumulative enrollment of students at these schools is higher. COEs received direct funding for 11,490 of these students, with funding for the remaining 6,844 students negotiated through local agreements with districts. County community schools served an average of 241 students (ADA), though the range was large, with several small county community schools averaging fewer than 10 students per day and the largest county community schools serving more than 1,000 students per day.

COEs Must Develop Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs) for Their Alternative Schools. The LCAP is a three‑year plan that outlines each COE’s strategy to improve outcomes for students enrolled at its alternative schools. The California Department of Education reviews and approves these plans. The plans are intended to hold COEs accountable for serving these students and provide information to the public about the services students receive. In addition, students attending alternative schools participate in the state’s standardized testing system. Students who have been enrolled in a county program for fewer than 90 days have their test scores attributed to their home district. Once a student has been enrolled at a COE alternative school for more than 90 days, or enters a COE alternative school after dropping out, the COE rather than the home district is responsible for that student’s outcomes.

Required District Services

State Tasks All COEs With Two Main District Oversight Activities. State law tasks COEs with both fiscal and academic oversight of districts within their jurisdiction. Chapter 1213 of 1991 (AB 1200, Eastin) established the current fiscal oversight process, whereby COEs regularly monitor district solvency. Specific associated responsibilities include the review and approval of school district budgets, the review of interim financial reports during the year, additional monitoring and technical assistance for districts identified as being at‑risk for fiscal insolvency, and more extensive intervention when districts are in severe fiscal distress. Chapter 47 of 2013 (SB 859, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) established the current academic oversight process, whereby COEs regularly monitor districts’ academic goals and performance. The associated responsibilities consist primarily of reviewing and approving district LCAPs. As part of this process, state law requires COEs to verify that district LCAP documents use the state‑approved format, align with districts’ adopted budgets, and appropriately direct funds to disadvantaged students. If district LCAPs meet these requirements, COEs must approve them. If a COE rejects an LCAP, it must provide the district with technical assistance in refining the plan.

State Tasks COEs With Various Other Compliance Activities. For the most part, these activities relate to ensuring districts are following various state laws and have submitted accurate data to the state. COEs generally report that these activities tend to be less time‑intensive than reviewing district LCAPs and providing fiscal oversight.

COE Support Role in Midst of Transition. When the state designed its new funding and accountability system for school districts beginning in 2013‑14, it gave COEs a role in supporting certain types of districts. Specifically, COEs must provide technical assistance to districts that do not meet performance benchmarks in two or more of eight specified state priority areas (which include student achievement and student engagement) for one or more student subgroups. Upon identifying a district as underperforming, COEs must do at least one of the following: (1) review the district’s strengths and weakness and identify effective programs that could help the district improve, (2) assign an academic expert to help the school district improve outcomes, or (3) request the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (the Collaborative) provide assistance to the district. (The state created the Collaborative to advise and assist local education agencies in reaching their LCAP goals.) The exact roles of COEs under the state’s new accountability system are still being worked out. (As discussed in the nearby box, some COEs historically have served in district support capacities.)

Some COEs Historically Have Had a Role in “Turnaround” Efforts

Some county offices of education (COEs) historically have provided comprehensive academic or turnaround support to low‑performing schools and districts. Some COEs, for example, have received state approval to be a School Assistance and Intervention Team, a District Assistance and Intervention Team, and/or a hub under the Statewide System of School Support. In these capacities, COEs have helped low‑performing schools and districts review their academic practices, identify their shortcomings, develop strategies for overcoming them, and implement those strategies—typically through a mix of resource reallocation, coaching, and other best practices. Much of COEs’ support and intervention has centered around helping schools and districts that have failed to meet federal performance standards, but some of it has focused on helping schools and districts failing to meet state performance standards. For example, under the Quality Education and Investment Act, COEs reviewed the professional development plans submitted by schools with low scores on state tests.

Funding

In this section, we provide an overview of total funding for COEs. We then explain how the state funded COEs before LCFF and describe how it funds them under LCFF. Next, we use available expenditure data to analyze how COEs are using their LCFF funds.

Overview

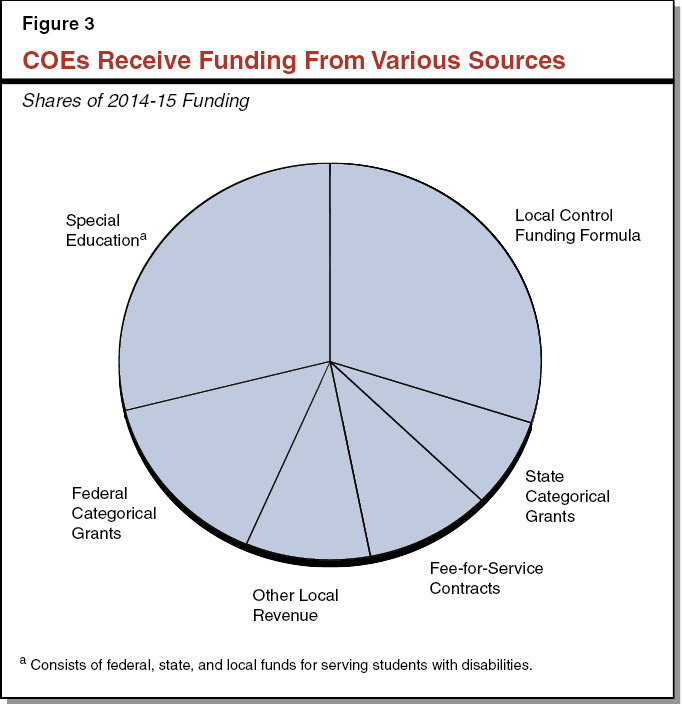

COEs Receive Funding From Various Sources. In 2014‑15, COEs received a total of $3.4 billion. As Figure 3 shows, this funding came from various sources. The LCFF, the primary source of state funding for COEs, accounts for just over one‑quarter of all COE funding. As described in detail later in this report, every COE receives LCFF funding. The amount they receive varies according to county size and characteristics. COEs may use this funding for any purpose. The state also allows COEs to apply for some categorical funding. For example, in 2015‑16, about half of COEs received funding for the Career Technical Education Incentive Grant. Another significant source of funding relates to special education. COEs receive this funding from various federal, state and local sources. Other notable sources of funding include federal categorical grants for specific activities (such as operating Head Start preschool programs) and revenue generated locally through fee‑for‑service contracts. For example, some COEs have contractual agreements to provide payroll or accounting services to their districts. (Other COEs provide these services at no charge as part of their palette of optional services.)

State Funding

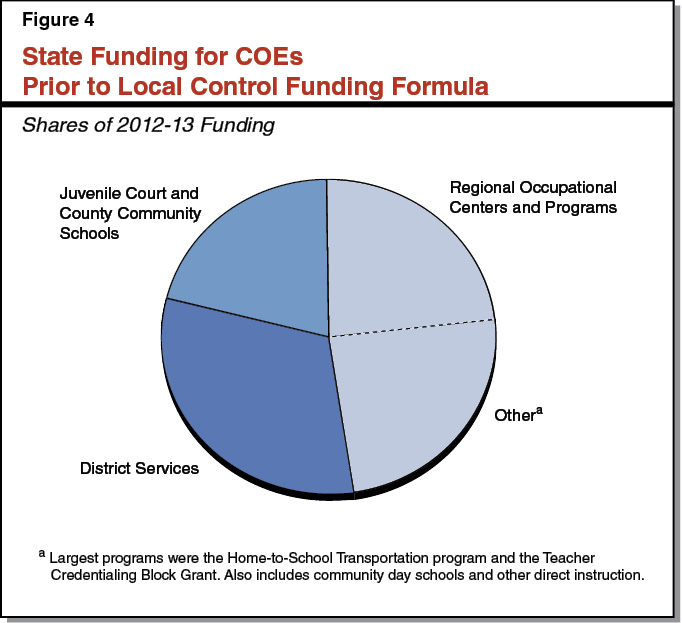

Prior to LCFF, State’s System of Funding COEs Was Particularly Complicated. Even setting aside the complexity of special education funding, COEs prior to LCFF could receive funding from many different programs, with funds allocated based upon many factors, some of which were rooted in COEs’ behavior decades earlier. As Figure 4 shows, about 20 percent of COEs’ state funding (excluding special education) was for court schools and county community schools. This funding was formulaic, based on the number of students served in these schools. COEs had to use this pot of funding on these students. COEs received about 30 percent of their state funding for district services. This allocation was based on the number of students served by districts in the county, historical funding rates (which varied widely across COEs), and various add‑ons (such as funding for increases in unemployment insurance costs). This funding was unrestricted. Though COEs had discretion, they commonly used the funding to provide various optional services to districts, including business support, professional development, and technology services. The remaining half of COEs’ state funding came from various state categorical programs. Most notably, many COEs received funding to provide career technical education through Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROCP)—alone accounting for about 20 percent of COE funding statewide. ROCP, like other categorical programs, had its own rules for applying, receiving, and spending associated funding. COE participation in these categorical programs varied widely, with some COEs operating many large programs, and some operating no programs.

State Now Allocates Bulk of Funding Through LCFF. In crafting LCFF, the state consolidated most state funding for COEs and replaced most of the former funding formulas with a new, two‑part formula. As Figure 5 shows, the two‑part formula reflects two core COE activities: (1) alternative education and (2) district services. Each COE’s target funding level is the sum of the two parts. Like the school district LCFF, the COE LCFF is funded by a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue, with the proportion of each fund source varying by county. COEs have flexibility to use all LCFF funds (from either part of the formula) for any purpose.

Figure 5

Two‑Part Local Control Funding Formula for COEs

2016‑17 Rates

|

Alternative Education |

|

|

Eligible student population |

Students who are (1) under the authority of the juvenile justice system, (2) probation referred, (3) on probation, or (4) mandatorily expelled |

|

Base funding |

$11,429 per studenta |

|

Supplemental funding for EL/LI and foster youth students |

35 percent of base rateb |

|

Concentration funding |

Additional 35 percent of base rate for EL/LI and foster youth students above 50 percent of enrollmentb |

|

District Services |

|

|

Base funding of $668,242 per COE |

|

|

Plus $111,734 per school district in the county (corrected 2/17/17) |

|

|

Plus $41 to $71 per student in county (less populous counties receive higher per‑student rates)a |

|

|

aAs measured by average daily attendance. bAssumes 100 percent of students at juvenile court schools are English learner and low income (EL/LI). |

|

COE LCFF Has Two “Hold Harmless” Provisions. Implementing legislation included two provisions intended to hold harmless COEs that otherwise would have received less funding under the new formula. The first provision guarantees that each COE will continue to receive at least as much total funding as it received from revenue limits and categorical programs in 2012‑13. The activities formerly associated with this funding, however, are no longer required. In 2014‑15, less than half of COEs were funded at the levels specified by their LCFF targets and the rest were funded at their higher 2012‑13 funding levels. The second provision, known as minimum state aid, ensures that each COE will continue to receive at least as much state General Fund as it received in 2012‑13 for categorical programs. The amount of minimum state aid to which each COE is entitled varies based on historical participation in categorical programs, with those that ran more and/or larger programs receiving larger amounts of state aid. Similar to the first hold‑harmless provision, COEs are not required to provide the services that originally generated the minimum state aid allotment. Almost two‑thirds of COEs receive funding from one or both hold harmless provisions. This funding can be used for any purpose.

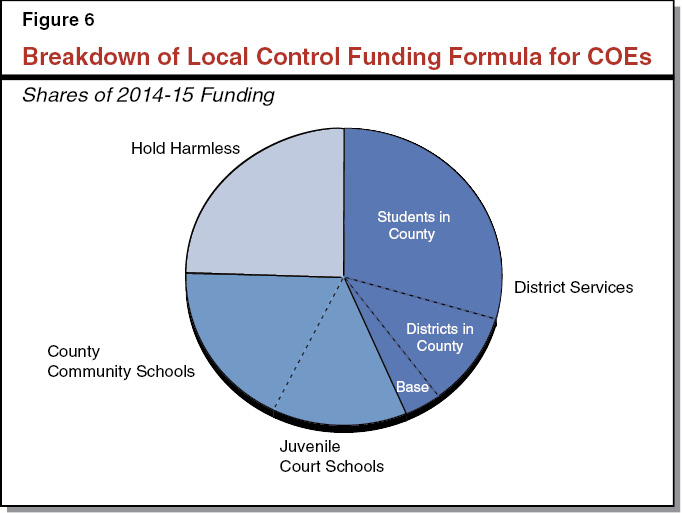

District Services Is Largest Component of LCFF for COEs. As Figure 6 shows, of the $1 billion generated by LCFF in 2014‑15, the juvenile court and county community schools portion generated about 30 percent, the district services component generated about 45 percent, and the two hold harmless provisions generated a combined 25 percent. The share associated with the hold harmless provisions reflects the amount provided on top of the funding the COEs would have otherwise received under the new system.

State Also Annually Funds COEs Through Mandates Block Grant. Prior to LCFF, the state funded COEs for certain required activities, such as teacher credential monitoring, through either the K‑12 mandates block grant or the mandate reimbursement process. COEs chose how they wanted to receive mandate funding. Post‑LCFF enactment, the state continues to use this approach to funding mandated activities. Under the K‑12 mandates block grant, COEs currently receive $1 for every student in their county, $28.42 for every student they educate in a county‑run school in grades K‑8, and $56 for every student they educate in a county‑run school in grades 9‑12. Under the mandate reimbursement process, COEs file reimbursement claims for each mandate. In 2016‑17, 95 percent of COEs were participating in the K‑12 mandates block grant. The remainder filed claims for individual mandates.

COEs Also Can Receive Grant Funding. Though the state eliminated many state categorical programs as part of the new LCFF system, many COEs continue to receive funding from various remaining (and new) state and federal grant programs. For example, since the enactment of LCFF, the state has created a new program—Career Technical Education Incentive Grants—and many COEs receive associated funding. Many COEs also receive federal grants on behalf of students who are neglected, delinquent, or at risk. Certain COEs also receive special grants from the state to perform specified statewide functions. For example, the Imperial COE currently receives a grant to manage Internet service on behalf of COEs.

State Recently Provided One‑Time Funding for New Oversight Activities. The 2015‑16 budget plan provided $40 million in one‑time Proposition 98 funding to COEs. Though the funding was unrestricted, it was intended for COEs to use on their newest oversight activity—review and approval of district LCAPs. The funding was distributed to COEs based on the number of school districts in the county and ADA at those schools.

Analysis of How COEs Use Their LCFF Funding

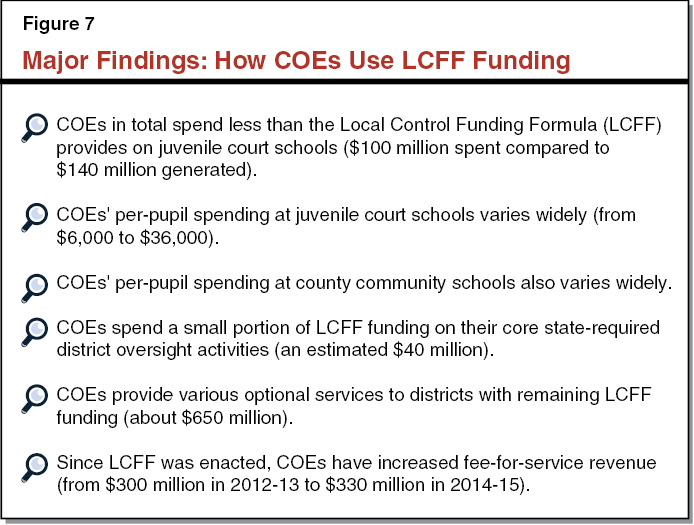

To understand better how COEs are functioning in the LCFF era, we examined how much LCFF funding they were spending on alternative education, required district oversight services, and optional district services. Our analysis uses 2014‑15 data, which was the first year of full LCFF implementation for COEs and is the most recent expenditure data available. Figure 7 summarizes our key findings.

Alternative Schools

COEs Spend Less Than LCFF Provides on Juvenile Court Schools. In 2014‑15, LCFF provided COEs with $17,300 for each student attending a court school, totaling about $140 million statewide. Based on financial data COEs submit to the state, we estimate that in 2014‑15 COEs spent an average of about $12,500 per student—about $100 million statewide. That is, COEs statewide spent about 70 percent of the funding generated by their court school students on programs and services designated for those students. (Given that 2014‑15 was the first year of full LCFF implementation, some COEs might not yet have fully enhanced their alternative education programs, with plans to make further enhancements and increase spending per student in the coming years.)

Per‑Student Court School Spending Varies Widely Across Counties. We found that some COEs spent as little as $6,000 per student (ADA), whereas others spent as much as $36,000 per student. Per‑student spending might vary because of class size, with smaller classes having higher per‑student costs. In addition, COEs have different cost‑sharing agreements with county jails and county sheriff departments. County jails typically cover all or a portion of the cost of facilities for juvenile court schools as well some additional costs, such as security and counseling, with the exact arrangements negotiated locally.

Estimating County Community School Funding and Spending Complicated by Reporting Rules. In 2014‑15, LCFF provided COEs with an average of $15,900 per county community student (those who were on probation, referred by a probation department, or mandatorily expelled), totaling $183 million statewide. In addition, COEs received funding through district reimbursements for other types of students served in these schools. The state, however, does not track these funding transfers. Moreover, reported expenditure data do not delineate clearly whether COEs include spending on all students or only direct COE‑funded students.

Small County Community Schools Have Higher Per‑Student Costs Than Large Schools. Despite the complications noted above, the data suggest that COEs serving a small number of students at their county community schools typically spend much more per student than larger county community schools. Operating small county community schools is relatively expensive because these schools tend to have higher instructional and security costs due smaller class sizes as well as higher transportation costs due to special routes being required.

Required District Services

COEs Spend Small Portion of LCFF Dollars on Required District Oversight Activities. According to COEs, oversight of district budgets and LCAPs are their most costly required oversight activities. COE financial reports, however, do not include much detailed information about the cost of these activities. To estimate these costs, we took the following approach. For fiscal oversight activities, we reviewed the amount of categorical funding COEs received before LCFF for performing those activities and spoke with some COEs about their current costs. Based on these data and conversations, we estimate that COEs could be spending up to $20 million per year statewide on their required fiscal oversight activities. To estimate the costs of LCAP oversight, we relied on information provided by COEs to the California County Superintendents Educational Services Association. Based on this information, the organization estimated that COEs annually spend roughly $20 million in total on LCAP activities. Combining spending for fiscal and LCAP oversight, we estimate COEs statewide are spending roughly $40 million annually.

Optional Services

COEs Spend Remainder of LCFF Funds on Optional Activities. After covering the costs associated with alternative education (an estimated $283 million) and required district services (an estimated $40 million), COEs spend the rest of their district services and hold harmless allocations (roughly $650 million) on optional services. COE financial reports include only limited information about how COEs spend this $650 million. Moreover, COEs are not required to develop an LCAP for the portion of LCFF funding they use to provide optional services.

COEs Provide Various Optional Services to Districts. Based on our conversations with COEs and our review of available financial reports, COEs are most commonly providing optional services that resemble the categorical programs (most notably, ROCP) they ran before LCFF. In addition, some COEs indicated that they were providing more LCAP support to their districts than statute requires. The types and levels of extra support, however, vary greatly. COEs providing the most support offer help year round as well as conduct trainings on developing LCAPs. One COE we spoke with had assigned a project manager to each school district to guide them through the LCAP process. Lastly, COEs we spoke with indicated that they offer services consistent with county superintendent priorities. For example, one COE we spoke with used LCFF funding to purchase computers for districts in their county. Another COE indicated that they offered enrichment programs like outdoor education and art. In addition, some COEs sponsor special initiatives in their counties, such as truancy reduction efforts.

COEs Supplementing LCFF With Fee‑for‑Service Revenue. Fee revenue at COEs has increased over the last three years, from $300 million in 2012‑13 to $330 million in 2014‑15. In 2014‑15, 90 percent of COEs charged their districts fees for services, although the fee‑based services and fee amounts varied across the state. Many COEs indicate that they now commonly charge fees or are moving to a fee‑for‑service model for career technical education programs and teacher induction programs. While COEs often charge fees to districts for the optional services they provide, many continue to offer services to districts at no charge or at a subsidized rate. Additional LCAP support and payroll services were noted as common examples of no‑charge or reduced‑charge services.

Back to the TopAssessment

In this section, we assess COEs’ roles in the LCFF era. We first assess their role in alternative education, then turn to required district oversight services, and finally to optional district services.

Alternative Schools

Providing COEs With Direct Funding for Court Schools Has Shortcomings. Funding COEs directly for serving incarcerated students has shortcomings in that it detaches these students from their districts of residence and creates limited incentives for school districts to oversee the quality of students’ education while incarcerated. Additionally, COEs are not the only groups that could work with county jails and probation departments to provide educational services to incarcerated youth. Though many COEs currently have a longstanding role serving these students and over time have established relationships and cost‑sharing agreements with county jails and probation departments, other groups, particularly large school districts, could develop similar expertise, relationships, and agreements. Moreover, allowing districts to have some influence on the educational provider of court schools might over time improve program quality and reduce program cost.

Even Greater Concerns Regarding Direct Funding for County Community Schools. The state’s current approach to alternative education also assumes that COEs are best positioned to serve students who are on probation, referred by a probation department, or mandatorily expelled. Presumably, the theory is that COEs will achieve economies of scale (larger, better, less costly programs) by pulling all these students together on a single site. Our review, however, finds that county community schools often are small and difficult to hold accountable for student outcomes. Regarding size, we found that at least 20 percent of county community schools serve 20 or fewer students. Schools serving very few students often report costs per student that are two to three times greater than the average amount spent to educate students in district alternative education settings. Additionally, regarding academic opportunities and outcomes, we found no clear, compelling evidence that county community schools necessarily offer students better educational opportunities or have better student results than district‑run alternative schools serving similar students.

Districts Could Be Better Positioned to Serve This Student Population. The state currently funds districts to serve most types of at‑risk students. Thus, all but the smallest districts are likely to have 20 or more students districtwide that need (due to mandatory expulsion) or could benefit (due to behavior or academic issues) from alternative placements. As a result, COEs do not appear to have a comparative advantage over districts in serving a certain, small subset of alternative education students. Using COEs in this area also has serious disadvantages. Most notably, districts lose the incentive to ensure these students stay in school, have access to high‑quality academic programs, receive wraparound supports, and can attend school sites within closer proximity of their homes.

Required District Services

COEs Well Positioned to Continue Providing Fiscal Oversight. California has more than 900 school districts, such that a single entity at the state level likely would have difficulty providing effective fiscal oversight of all school districts. Compared to a state‑level entity, COEs tend to be more familiar with the local fiscal circumstances facing districts in their counties. In addition, school district fiscal health has improved since the state created a new fiscal review system and assigned new fiscal oversight duties to COEs. Since 1991, only eight school districts have required emergency loans from the state to avoid fiscal insolvency. By contrast, nearly 30 districts required emergency loans from 1981 to 1991. Though the improvement likely is due to the new review process itself, COEs appear to have performed their role effectively—helping provide more direct, routine oversight of district budgets.

COEs Well Positioned to Review and Approve LCAPs. We believe the large number of districts in the state also provides a compelling rationale for COEs to review and approve districts LCAPs. Compared with a single state entity, COEs tend to be more familiar with the academic performance issues in their districts and better able to assess whether the LCAPs appropriately address these issues. In addition, the law requires LCAPs to align with district budgets, which COEs already are required to approve.

COEs Well Positioned to Do Other Compliance Monitoring. Many other compliance reviews performed by COEs likely would be less effective or more costly if undertaken by a state entity. For example, COEs hear appeals when a district expels a student or denies an interdistrict transfer. These hearings would be difficult for parents and students to attend if conducted outside the county where they occurred. COEs also conduct reviews to ensure that schools have sufficient textbooks and instructional materials to serve all of their students. Since these reviews require a physical inspection, they would be more costly to perform if assigned to an entity located farther from the schools than the COE.

Optional Services

Directly Funding COE Optional Services Provides No Benefit From State Perspective . . . Directly funding COEs to provide optional services to districts provides little obvious benefit either to the state or districts. From the state’s perspective, it now does not track what optional district services COEs provide, if districts want those services, or if those services are being provided cost‑effectively. Providing funding directly to COEs also is counter to the state’s overarching LCFF philosophy, whereby districts receive funding with few strings to promote more coherent fiscal and academic planning.

. . . Or District Perspective. From a district perspective, districts also presumably would prefer receiving funding directly and identifying for themselves the services they cannot or do not want to provide in house, rather than being offered subsidized COE services they might not want. Under the current funding system, COEs receive the same amount of LCFF funding regardless of how well they address the priorities of their districts. As a result, COEs do not have much incentive to add or discontinue services in response to changing district priorities. It also provides districts with little recourse if they are dissatisfied with the quality of services they are receiving. In line with these concerns, we found that COEs rarely have a formal process to obtain feedback about the types of services they are providing to districts. Districts and COEs indicated that they sometimes have informal discussions about what services would benefit districts most, but this feedback often depends on relationships with a few individual districts rather than a systemic effort to identify priorities for districts across the entire county.

Back to the TopRecommendations

In this section, we make a series of recommendations that if taken together would reshape how the state funds COEs. Figure 8 summarizes our recommendations. We first make recommendations relating to alternative education, then provide recommendations relating to required district services and optional district services. We conclude by outlining steps the state could take during the transition period.

Figure 8

Summary of Recommendations

|

|

|

|

Alternative Education

Fund Districts Directly for Their Incarcerated Students. We recommend the state provide education funding for incarcerated students to their districts of residence and require all associated accountability data be attributed to those districts. Providing funding to districts for these students and tying the students’ progress to district accountability reports would ensure that districts (1) oversee the services their students receive while incarcerated and (2) monitor the quality and costs of those services.

Set COE as Default Court School Provider but Allow Districts Collaboratively to Select Alternative Provider. Under this approach, state law would establish COEs as the standard court school provider. State law also would set forth a default per‑student reimbursement rate for incarcerated students. Under these provisions, COEs likely would continue operating court schools in all or virtually all areas of the state, with districts passing through the set (or negotiated) reimbursement rate for each of their incarcerated students. We recommend, however, that state law allow districts voluntarily and collaboratively to select an alternative court school provider. Under this alternative arrangement, districts could negotiate any per‑student fee rate.

Likely Little Immediate Impact but Over Time Could Promote Improvement. Because COEs have experience running court schools and longstanding relationships with county jails and probation departments, we believe such changes in state law likely would not lead to immediate or dramatic changes in the court school landscape. Nonetheless, it would give large districts more choice in how best to run nearby court schools. It also would give other districts at least an opportunity to come together to pursue alternatives if they are dissatisfied with their COE‑run court schools. With enough deliberation and negotiation, districts within a county might be able to agree to an alternative provider (such as the largest district among them, a nonprofit organization, or a nearby COE). Over the next few years, the Legislature could track whether districts were able to navigate such arrangements. Depending upon what it learned, the Legislature could consider statutory modifications to address any significant barriers to such collaboration.

Various Options for Shifting Funding and Setting Rates. The Legislature would have various options for shifting funding initially from COEs to districts and setting the statutory maximum COE per‑pupil court school reimbursement rate. The most seamless approach would be to set the new district funding rate at the high school LCFF rate, which is intended to reflect the average cost of serving high school students. As incarcerated students comprise a tiny share of districts’ student populations, districts still likely could cover the statutory maximum COE reimbursement charge for those students within their entire district budgets. Another approach would be to set both the direct district funding rate and statutory maximum COE reimbursement rate at the amount COEs currently spend on incarcerated students. Though a higher‑cost and more complicated approach (as it effectively would entail an LCFF “add‑on” for districts), it likely would enable districts to adjust more easily to the new system in the near term. A third approach would be to set the direct district funding rate and statutory maximum COE reimbursement rate at the current court school funding rate under the COE LCFF. Though court schools on average now spend less than the current funding rate, the Legislature might want to enhance court school programs. Under this approach, the Legislature likely would want to add specific spending requirements ensuring funding was used for the intended purposes.

Fund Other Alternative School Students Through Their Districts and Provide Flexibility Over Placements. With regard to students who are probation‑referred, on probation, or mandatorily expelled, we recommend the Legislature also discontinue direct funding to COEs and instead fund all students through their districts of residence. Districts receiving this funding would be responsible for appropriately placing these students into education programs. These placements could include district‑run programs, programs run by a consortium of small‑ or mid‑sized districts, specialized charter schools, or an alternative school operated by a COE. In the latter case, districts would reimburse the COE for the costs of serving these students. We think this approach could result in better placement decisions for students, primarily because a district of residence is likely to be more familiar with students’ educational history than the COE and would have the flexibility to choose from multiple placement options. In addition, this approach would align with the way the state refers all other at‑risk students, including students who are habitually truant or expelled for nonmandatory reasons. Moreover, many COEs and districts already have developed local arrangements under which the districts refer some of their students to COE‑operated schools and reimburse the COEs for the cost of educating those students. Under our approach, districts could expand upon these partnerships or develop other programs better suited to the needs of their students. As with setting the funding rate for incarcerated students, the Legislature would have various options for setting the rate for other alternative education students, including setting it at the high school LCFF rate or keeping the current rate.

Hold Districts Accountable for Student Outcomes. In tandem with the above changes, we recommend the state hold school districts accountable for all their alternative education students, including those they decide to serve in their own district programs or in selected COE programs. Regardless of the students’ placement, we recommend assigning test scores and other outcome data to each student’s district of residence. Students referred to a COE county community school, for example, would continue to have their test scores assigned to the districts that referred them. In the case of county community schools, this arrangement would encourage districts to choose high‑quality placements where the performance of these students would reflect positively on those districts. In the case of juvenile court schools, it similarly likely would encourage districts to work with the court school provider to foster high‑quality programs.

Required District Services

Fund COEs Directly for Core Oversight Activities. We believe fiscal and academic oversight is likely to be more effective when it is performed at a county (or regional) level than at the state level. We recommend the state fund COEs for conducting these activities using a formula that reflects expected underlying costs. As the workload associated with these activities tends to vary according to the number of districts in each county and the size of those districts, we recommend using these two factors to establish the new formula. For example, the state could classify school districts as being large, medium, or small and provide each COE an allotment based upon the number of districts in the county that fall into each category. (As part of the new formula, the state could consider increasing the rates to account for base COE costs, including the county superintendent’s salary and office overhead.)

Continue to Fund COEs Through Mandates Block Grant for Other Required Activities. For the other required COE compliance activities, costs tend to vary according to the number of students within the county. As the current mandates block grant for COEs is based on the number of students within the county, we recommend the state continue funding these other required activities through the block grant.

In the Future, Revisit COE Funding for Providing Support to Districts Not Meeting Performance Benchmarks. Once the state more clearly defines the respective roles of COEs, the Collaborative, and other academic experts in providing support to districts not meeting performance benchmarks, the Legislature at that time could consider how best to provide associated funding.

Optional Services

Shift Funding to Districts and Allow Them to Purchase Services They Find Valuable. We recommend the Legislature phase out the portion of the LCFF that COEs use to provide optional services, in tandem increasing district funding by a like amount. In lieu of direct state funding, COEs would provide optional services to districts on a fee‑for‑service basis. Districts, in turn, could continue to receive services by paying their COE or could pursue other options, like contracting with another district or hiring additional staff to perform the services internally. This approach would provide a strong incentive for COEs to offer helpful, high‑quality services that are responsive to district needs. It also would encourage more COEs to develop expertise in specific areas and make their services available to districts outside of their county. For example, a COE that developed a successful teacher training program could offer this service on a fee basis to districts throughout the state. In addition, the fee‑for‑service approach would build upon an arrangement that is already widespread among districts and COEs.

Next Steps

New System Entails Significant Changes. Our recommendations signify major changes in the way the state funds COEs. The fiscal impact on COEs would be significant, with the bulk of COEs’ LCFF funding shifting to school districts. Through local fee‑for‑service arrangements, however, a large portion of this amount could go back to COEs that operate successful programs for their districts.

Recommend Multiyear Transition Plan. We recommend the Legislature phase in the new funding model over the course of the next few years. The first year could be devoted to preparing for the new system, with no immediate changes to COE funding. In the subsequent few years, the state gradually could phase out the portion of COE funding now spent on optional activities, in tandem increasing district funding, while retaining direct COE funding for fiscal and academic oversight. Over this same period, the state also could increase school district funding for alternative education students. A gradual transition would limit disruption to both COEs and districts. In addition, a multiyear transition period would provide an opportunity for COEs and districts to communicate about what services districts want their COEs to provide and allow time to negotiate fee‑for‑service arrangements.

Back to the TopConclusion

Core COE Mission Not Well Defined. Though the State Constitution establishes county superintendents of schools and county boards of education, the core mission of COEs is not entirely clear. COEs traditionally have provided some district oversight, some district support, and some direct classroom instruction. Although the state has required COEs to perform certain functions over the years, these activities account for a relatively small share of most COE budgets. COEs spend the bulk of their funding on optional services. The nature of these services varies widely across the state and tends to reflect the priorities and educational philosophy of the elected county superintendents and historical practice.

Role of COEs Even Less Clear Today. Though LCFF somewhat simplified funding for COEs, it did not clarify COEs’ mission. Arguably, it made COEs’ mission even more nebulous, as it removed many COE spending restrictions designed to further specific state purposes while increasing overall COE funding. Compared with the previous system of school finance, COEs now receive a much larger share of their funding in the form of unrestricted grants. Although the lack of a clear mission for COEs is not a new issue, we think the recent funding reform makes the issue an even more pressing concern for the state.

Strategic Approach to COEs’ Mission and Funding Could Reinforce Broader Reform Efforts. In this report, we recommend the Legislature take a more strategic approach to COEs. The first step in such an approach is to define clearly the core mission of COEs and the activities the Legislature believes all COEs should perform. The second step is to align funding with those required activities. In this report, we suggest making fiscal and academic oversight the core mission of COEs and providing state funding to perform this oversight. We suggest shifting other COE funding to districts so that districts can pay for the services they find valuable. We think this approach would provide a stronger incentive for COEs to offer helpful, high‑quality services that are responsive to district needs. It also would align with the broader state objective of increasing local decision making power while strengthening accountability for student outcomes. Although the transition likely would take a few years, we think the end result would be a more straightforward, transparent system with a more clearly defined role for COEs.