Correction 3/6/17: Removed reference to Alpine County as having only one participating insurer.

February 17, 2017

The Uncertain Affordable Care Act Landscape:

What It Means for California

- Introduction

- Major Provisions of the ACA

- ACA Fundamentally Altered the Health Care Landscape in California

- The ACA’s Uncertain Future—What Changes to the ACA Could Mean for California

- Common Themes of Republican ACA Replacement Plans

- Legislative Considerations Given the ACA’s Uncertain Future

Executive Summary

Major Provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA was signed into law in March of 2010. The ACA made substantial changes to how health care services and health insurance coverage are provided nationwide. Major provisions of the ACA include: (1) insurance market changes, (2) subsidized coverage for qualifying individuals through federal and state Health Benefit Exchanges, (3) federal funding for an expansion of program eligibility in state Medicaid programs, (4) additional federal financial participation in other health care programs and services, and (5) new federal revenues.

The ACA Fundamentally Altered California’s Health Care Landscape. California’s health care landscape looks very different from before the full implementation of the ACA. Some of the major impacts that the ACA has had on the state, in addition to the insurance market changes, include:

- One in three state residents is now enrolled in the state’s Medi‑Cal program, reflecting the state’s adoption of the ACA optional Medicaid expansion.

- A significant reduction in the number of uninsured state residents—from 6 million in 2013 to 3 million in 2015.

- More than $20 billion in additional federal funding each year for health care coverage, through enhanced federal funding for the ACA optional expansion and federal subsidies for coverage purchased on the state’s Health Benefit Exchange—Covered California.

Significant Federal Uncertainty About the Future of the ACA. The new presidential administration and congressional majority leaders have stated an intent to repeal (or at least make major changes to) the ACA and have taken procedural steps to begin doing so. However, there is substantial uncertainty as to (1) whether and which components of the ACA might be repealed, (2) when any repealed components of the ACA would become inoperative, and (3) what policies could replace those in the ACA.

The ACA Provisions Most at Risk for Repeal . . . Congressional Republicans have initiated the first steps of the federal “budget reconciliation process” to facilitate the potential repeal of certain major components of the ACA. Some of the components potentially subject to repeal through use of this process include federal funding for the ACA optional expansion, federal funding for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through Health Benefit Exchanges, enhanced federal funding for other health care programs and services in Medicaid, and the individual and employer mandate tax penalties.

. . . Would Have Significant Consequences for California. Changes in the ACA components most at risk for repeal—absent replacement policies—would have significant consequences for California. These include the potential loss of substantial annual federal health care funding, the uncertain survival of Covered California, a potentially considerable increase in the number of uninsured Californians, and a possible disruption of the commercial health insurance market.

Common Themes of Republican Replacement Proposals. Congressional Republicans have offered several replacement proposals that build off of the repeal of some or all components of the ACA. Some of the broad common themes from several of the Republican ACA replacement plans include: (1) continuing to use the tax system to make health coverage available, (2) aiming to increase competition and choice while reducing costs, (3) promoting flexibility for state Medicaid programs, and (4) reducing growth in federal health care expenditures.

Common Federal Health Care Policy Changes in Republican Replacement Proposals. To achieve the common themes of their proposals, Republican replacement plans often contain a number of common policy proposals, each with significant fiscal and/or policy implications for the state. These include:

- Replacing ACA premium tax credits and cost‑sharing reductions with an alternative health care tax credit structure.

- Encouraging the use of health savings accounts.

- Limiting the tax excludability of employer‑sponsored health benefits.

- Requiring continuous health insurance coverage.

- Removing ACA requirements on essential health benefits.

- Facilitating the use of catastrophic health insurance coverage.

- Facilitating the interstate sale of health insurance plans.

- Converting Medicaid into a block grant or per capita allotment program.

- Reconstituting high‑risk pools.

Legislative Considerations Given the ACA’s Uncertain Future. Given the uncertainty around the future of the ACA and the substantial federal funding that is potentially at risk, we recommend the Legislature maintain fiscal prudence in preparation for changes at the federal level, and consider how changes to the ACA could require a reevaluation of the state‑local health care financing relationship.

Introduction

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has significantly transformed California’s health care landscape—imposing new, far‑reaching rules governing the state’s health insurance markets and providing considerable new federal funding to help Californians obtain health care coverage. The result has been a marked shift in how—and how many—Californians access health care coverage.

Before the ACA, the accessibility of health care coverage was limited for certain populations and could vary depending on where in California an individual or family lived. Since 1966, Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program and largest publicly funded health care program, has provided health care coverage to the state’s low‑income residents. Before the ACA, however, eligibility for Medi‑Cal was generally limited to families with children, seniors, and persons with disabilities. Low‑income childless adults, for example, were generally ineligible for Medi‑Cal, often resulting in members of this population being without health care coverage. Other state and county publicly funded health care programs existed to serve populations with limited access to alternative forms of health care coverage, including county‑run indigent health care programs and state‑administered programs for individuals with high health care needs. Nevertheless, gaps in health care coverage existed in California. Since the full implementation of the ACA in 2014, the state has made considerable progress in improving the accessibility of health care coverage, as evidenced by a reduction in the uninsured rate of approximately 50 percent.

The ACA’s future, however, is highly uncertain. With the transition to a new presidential administration, there is now a movement to undo portions of the ACA and pass legislation that would again make far‑reaching changes to health care policy.

This report summarizes the major impacts that the ACA has had in California, explores what the ACA’s repeal could mean for the state, and assesses a collection of policy alternatives to the ACA that the new federal administration and Congress are currently considering. At the time of this publication, however, no ACA repeal or replacement legislation has been passed by either house of the current Congress. Thus, there is significant uncertainty as to (1) whether and which components of the ACA might be repealed, (2) when any repealed components of the ACA would become inoperative, and (3) what policies could replace those in the ACA. As a result, this report is a snapshot of where federal policymaking stands at the time of its publication, and might be used to begin considering how changes to the ACA could impact California and how the state might respond to best align the state’s health care policies with its priorities.

Back to the TopMajor Provisions of the ACA

This section outlines the major provisions of the ACA, including (1) insurance market changes, (2) subsidized health coverage through federal or state Health Benefit Exchanges, (3) federal funding for an expansion of program eligibility in state Medicaid programs, (4) additional federal financial participation in other health care programs and services, and (5) new federal revenues. Figure 1 summarizes the effective dates for major provisions of the ACA, ordered chronologically and into topical categories.

Figure 1

Effective Dates of Major Provisions of the ACA

|

Category |

Provision |

Effective Date |

|

Insurance Market Changes |

Dependent coverage until age 26 |

September 2010 |

|

No lifetime coverage limits |

||

|

Guaranteed availability and renewability of coverage |

January 2014 |

|

|

Individual mandate |

||

|

No preexisting condition exclusions for all enrolleesa |

||

|

No unreasonable annual coverage limits |

||

|

Restrictions on factors by which premiums may vary |

||

|

Employer mandate |

January 2015 (delayed from January 2014) |

|

|

Creation of Health Benefit Exchanges |

Essential health benefits |

January 2014 |

|

Subsidized and unsubsidized health insurance coverage through Health Benefit Exchangesb |

||

|

Medicaid Optional Expansion |

Enhanced federal funding for Medicaid optional expansion population |

January 2014 |

|

Other Augmented Federal Funding Under the ACAc |

Prevention and Public Health Fund |

June 2010 (first allocation) |

|

Community First Choice Option |

October 2011 |

|

|

Children’s Health Insurance Program |

October 2015 |

|

|

New Federal Revenues Under the ACA |

Additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on high‑income taxpayers |

January 2013 |

|

3.8 percent surtax on high‑income taxpayers’ investment income |

||

|

Medical device excise taxd |

||

|

Health insurer provider feee |

January 2014 |

|

|

“Cadillac” tax |

January 2020 (delayed from January 2018) |

|

|

aPreexisting condition exclusion ban for dependents under age 19 effective September 2010. bFederal and state Health Benefit Exchanges required to be operational October 2013. cAugmented federal funding for Medicaid Health Homes and preventive services effective January 2011 and January 2013, respectively. dU.S. Congress enacted two‑year moratorium on the medical device excise tax starting January 2016. eCollection of the health insurance provider fee was suspended in 2017. ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

||

ACA Expected to Reduce Overall Federal Spending. Over the long run, the ACA was projected to reduce the federal budget deficit. For federal fiscal year (FFY) 2017‑18, ACA‑related spending was projected by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 2015 to be a little over $100 billion nationwide, while ACA‑related revenues, if fully implemented, were projected to be $100 billion. (The FFY runs from October 1 through September 30.) A combination of declining ongoing ACA spending and higher ongoing ACA‑related revenues were expected to start generating annual federal savings beginning in FFY 2018‑19.

Insurance Market Changes

The ACA reformed small group and individual health insurance markets by setting new requirements affecting access to health insurance coverage. While large group plans are exempt from several of these new requirements, the ACA did impose some requirements, such as a prohibition on annual or lifetime limits on coverage expenses on these plans. “Grandfathered” plans, defined as plans available in March 2010 that did not reduce benefits or increase costs for their beneficiaries, are also exempt from certain ACA requirements such as rating restrictions, which we describe below. The ACA phased in the insurance market requirements, and the individual and employer mandates, over time as shown in Figure 1.

No Preexisting Condition Exclusions. Preexisting medical conditions are health conditions that existed prior to an individual’s enrollment in a health insurance plan. The ACA prohibits health insurers from imposing preexisting condition exclusions. These exclusions include denying health insurance coverage, charging more for that coverage, and limiting or refusing to cover benefits associated with an individual’s preexisting condition.

No Annual or Lifetime Coverage Limits. The ACA bars all health insurance plans from setting lifetime limits on the dollar value of health insurance coverage that individuals receive under their plan. With the exception of grandfathered plans, all other plans are also barred from setting annual limits on coverage expenses.

Rating Restrictions. The ACA restricts how much and by what factors small group and individual health insurance premiums can vary (except grandfathered plans) across covered beneficiaries. Plans can only charge varying premiums based on (1) whether coverage is for an individual or family, (2) age, (3) tobacco use, or (4) geographical area.

Guaranteed Availability and Renewability of Coverage. A health insurer must accept all employers and individuals that apply for health insurance coverage, and permit annual and special enrollment periods for those with qualifying lifetime events (such as marriage or the birth of a child). Once an enrollee is covered by a health insurance plan, the ACA requires the plan to guarantee renewal of that coverage regardless of the enrollee’s health status, service use, or other related factors.

Dependent Coverage Until Age 26. Health insurers that choose to provide dependent health insurance coverage for children under a parent or guardian’s health insurance plan must continue to make coverage available to the child until he or she turns 26 years of age.

Individual Mandate. Individuals must be enrolled in health insurance coverage that meets certain minimum quality standards under the ACA or pay a tax penalty. Individuals can file for an exemption from the mandate if, for example, they have a financial hardship or they have religious objections to coverage. Those who can afford coverage, but decide not to obtain it or to file for an exemption from the mandate, must pay a tax penalty. The 2016 penalty is calculated either as a flat amount—$695 per adult and $347.50 per child under 18—or as 2.5 percent of household income, whichever amount is greater up to certain maximums. The intent of the individual mandate is to provide a disincentive for individuals to avoid coverage, especially younger and healthier people (who balance the health insurance risk pool).

Employer Mandate. Employers with at least 50 full‑time equivalent employees during the preceding calendar year face tax penalties: (1) if they do not offer health insurance coverage to at least 95 percent of their full‑time equivalent employees plus their dependent children, or (2) if they offer coverage the ACA does not consider affordable or of minimum value. Employer coverage is considered to be affordable under the ACA if employees pay no more than about 9.5 percent of their household income towards coverage, and of minimum value if the insurer pays for at least 60 percent of covered health care expenses for a standard population. Employer tax penalties vary based on the number of employees and whether they are offered coverage. If employees are offered coverage, the coverage must also be affordable and of minimum value to avoid tax penalties. The employer mandate is intended to discourage employers from reducing or not offering coverage knowing that subsidized coverage is available through the Health Benefit Exchanges and individuals are required to have coverage.

Creation of Health Benefit Exchanges

Online Marketplace for Individuals to Purchase Commercial Health Insurance. The ACA established online marketplaces, known as Health Benefit Exchanges, where individuals (and small businesses of 50 employees or less) can shop for commercial insurance coverage, be referred for Medicaid coverage, and receive federal financial assistance to help pay for commercial insurance coverage. The ACA gave states the option to either administer their own Health Benefit Exchanges or use the federal platform, Healthcare.gov. The majority of states opted to use the federal platform.

Open Enrollment Period Limited to Certain Months of the Year. In the absence of a qualifying life event such as marriage or the loss of alternative health coverage, individuals may only enroll in a Health Benefit Exchange health plan during certain months of the year, typically November through January. This limitation on open enrollment was established to prevent individuals from obtaining coverage only in the case of a medical event. Individuals who experience a qualifying life event may enroll in a health plan through the Health Benefit Exchanges at any time during the year.

ACA Standards on Essential Health Benefits (EHB) and the Comparability of Health Plans. As shown in Figure 2, the ACA requires that all health plans offered through the Health Benefit Exchanges (as well as all individual and small group insurance plans regardless of where they are sold) provide a common set of benefits, known as EHB. In addition, all health plans sold through the Health Benefit Exchanges are grouped into four standard tiers according to the percentage of medical expenses the insurance plan is expected to cover. Health plans in the highest tier pay the highest percentage of an individual’s expected medical costs (90 percent) and have higher premiums and lower copays and deductibles. Health plans in the lowest tier pay the lowest allowable percentage of medical expenses (60 percent) and have lower premiums and higher copays and deductibles.

Figure 2

ACA’s Ten Essential Health Benefits on Plans Sold Through

Health Benefit Exchanges

|

✓ |

Outpatient Medical Care |

✓ |

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services |

|

✓ |

Emergency Services |

✓ |

Rehabilitative Services and Devices |

|

✓ |

Hospitalization |

✓ |

Laboratory Services |

|

✓ |

Prescription Drugs |

✓ |

Preventive Services and Chronic Disease Management |

|

✓ |

Maternity and Newborn Care |

✓ |

Pediatric Services (Including Vision and Dental) |

|

ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

|||

Premium Tax Credits and Cost‑Sharing Reductions Available Through Health Benefit Exchanges. Citizens and legal residents with incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and for whom alternative forms of affordable health insurance coverage are not available are eligible for federal tax credits and cost‑sharing reductions to help pay for health coverage through the Health Benefit Exchanges. The amount of federal financial assistance available to an individual is higher for households with lower incomes. Accordingly, eligible individuals with the lowest incomes receive tax credits that reduce their monthly premiums to between 2 percent and 4 percent of monthly income, while eligible individuals with the highest incomes receive tax credits that reduce their monthly premiums to between 8 percent and 10 percent of monthly income. Additional federal financial assistance, known as cost‑sharing reductions, is available to the lowest‑income individuals who receive subsidized coverage to help them pay for out‑of‑pocket medical expenses such as deductibles and copays.

Medicaid Optional Expansion

Before the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was generally restricted to families and seniors and persons with disabilities with incomes below 108 percent of FPL. Therefore, childless adults under 65 were ineligible for Medicaid regardless of income. The ACA originally required all states to expand eligibility for their Medicaid programs to individuals under age 65 (children, parents, and childless adults) with household incomes at or below 138 percent of FPL by January 2014. If a state did not expand Medicaid eligibility, Congress could direct the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to withhold the state’s Medicaid allotment until it complied. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that this condition on a state’s Medicaid allotment was unconstitutional, and that states should have the option either to expand or to not expand eligibility for their Medicaid programs. The population that became eligible for Medicaid under the ACA is now commonly referred to as the ACA optional expansion population.

Enhanced Federal Funding for the ACA Optional Expansion. States that opt to expand eligibility for their Medicaid programs receive enhanced federal funding for the ACA optional expansion population. A state’s federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) is the federally designated portion of a state’s incurred Medicaid costs paid for by the federal government. For the non‑ACA optional expansion population, state FMAPs vary from a low of 50 percent (California) to a high of 75 percent (Mississippi). As shown in Figure 3, with the implementation of the ACA, the federal government paid an FMAP of 100 percent from 2014 to 2016 for the costs of covering the ACA optional expansion population. Starting this year, states that participate in the ACA optional expansion—including California—are responsible for 5 percent of the costs. In 2020 and thereafter, participating states must pay 10 percent of costs for the ACA optional expansion.

Figure 3

Federal Share of Costs for ACA Optional Expansion Population

|

Calendar Year |

Federal Medical Assistance Percentagea |

|

2014 |

100% |

|

2015 |

100 |

|

2016 |

100 |

|

2017 |

95 |

|

2018 |

94 |

|

2019 |

93 |

|

2020 and thereafter |

90 |

|

aDetermines federal share of costs for covered services in state Medicaid programs. ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

|

Other Augmented Federal Funding Under the ACA

The ACA increases federal financial participation for other health care programs and services in a state’s Medicaid program in addition to the enhanced federal funding for the ACA optional expansion population. For each program or service, the federal government provides an enhancement to the state’s existing FMAP. While some enhancements under the ACA are temporary, others are permanent. States can also apply for grants authorized by the ACA. The ACA phased in these augmentations and grants over time as referenced below.

Enhanced Federal Funding for Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). CHIP is a joint federal‑state program that provides health insurance coverage to children in low‑income families, but with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. Historically, states received higher FMAPs for CHIP coverage than for other Medicaid‑covered children. FMAPs for CHIP ranged from a low of 65 percent to a high of 82 percent. The ACA enhanced FMAPs for CHIP starting October 2015, ranging from a low of 88 percent to a high of 100 percent. Increased federal financial participation in CHIP is authorized by the ACA until FFY 2018‑19 but funding is only appropriated through FFY 2016‑17.

Enhanced Federal Funding for Community First Choice Option (CFCO). The CFCO is an option available to states within their Medicaid programs to provide home‑ and community‑based attendant services and supports to seniors and persons with disabilities. The ACA created the CFCO and provided states with an FMAP enhancement of 6 percentage points for services provided through the CFCO starting October 2011. Increased federal financial participation in the CFCO is ongoing.

Other Enhanced Federal Funding for Medicaid. There is also increased federal financial participation in Medicaid under the ACA for Medicaid Health Homes (enhanced FMAP of 90 percent for the first two years of implementation) and preventive services (1 percentage point FMAP enhancement).

Prevention and Public Health Fund. The Prevention and Public Health Fund supports grant programs administered by several federal agencies that promote state prevention, public health, and wellness activities. The ACA appropriated $7 billion in funding for all states from FFY 2009‑10 to FFY 2014‑15, with $2 billion ongoing after FFY 2014‑15. Since the ACA appropriated this funding, the former federal presidential administration and Congress agreed to several cuts to the Prevention and Public Health Fund. As of FFY 2016‑17, $931 million is available ongoing annually.

New Federal Revenues Under the ACA

The ACA established new sources of federal revenue to help pay for the additional federal costs associated with the ACA. For FFY 2017‑18, ACA revenues, if collected in full, were projected by the CBO in 2015 to be approximately $100 billion. Below, we summarize the major new revenues established under the ACA:

- New Taxes on High‑Income Earners. The ACA imposed two new taxes on high‑income earners: (1) an additional 0.9 percent Medicare Tax on personal incomes over $200,000 for single taxpayers and $250,000 for married taxpayers and (2) a 3.8 percent surtax on the portion of high‑income taxpayers’ investment income above $200,000 for single taxpayers and $250,000 for married taxpayers. For FFY 2017‑18, the ACA’s high‑income earner federal tax revenues are projected to exceed $30 billion annually.

- Individual and Employer Mandate Tax Penalties. As previously discussed, the ACA imposed a mandate on individuals to obtain health care coverage and on large employers to make affordable health insurance coverage available to their employees. Tax penalties are imposed on individuals and employers that do not comply with the ACA’s individual and employer health coverage mandates. For FFY 2017‑18, total federal revenue from the ACA’s mandate tax penalties is projected to be between $15 billion and $20 billion annually.

- Health Care‑Related Taxes. The ACA established an assortment of other health care‑related taxes, such as the Health Insurance Provider Fee, a fee on health insurers that raises a statutorily determined total amount of revenue each year; the “Cadillac tax,” an excise tax on high‑cost employer‑sponsored health plans that has not yet been implemented; and the Medical Device Excise Tax, for which there is currently a moratorium. For FFY 2017‑18, the ACA’s health care‑related taxes were expected to raise almost $20 billion in annual revenue for the federal government were they all in effect.

ACA Fundamentally Altered the Health Care Landscape in California

The ACA was far‑reaching legislation that made significant changes to health coverage and delivery in California. New standards govern the insurance products sold in the state, billions of dollars in additional federal funding for health coverage flow into California, the Medi‑Cal program has grown to include over one in three state residents, acquiring health coverage through the individual insurance market has become relatively more common, and the number of uninsured state residents has been dramatically reduced. This section highlights several of the major impacts that the ACA has had on the state.

ACA Insurance Market Reforms Took Effect in California Between 2010 and 2014. Between 2010 and 2014, California came into compliance with the ACA’s requirements on commercial health insurance products sold in the state. As a result, Californians can no longer be denied insurance coverage on the basis of having preexisting medical conditions, be charged higher premiums for having certain medical conditions, or face lifetime or unreasonable annual limits on the dollar value of benefits paid for by their insurer.

California Opted for Medi‑Cal Expansion. California opted to participate in the ACA’s optional Medicaid expansion, thereby expanding Medi‑Cal coverage to individuals with incomes up to 138 percent of the FPL, now including childless adults. California’s ACA optional expansion population receives health care coverage through the same Medi‑Cal fee‑for‑service or managed care delivery systems utilized by all other Medi‑Cal enrollees.

Medi‑Cal Mandatory Expansion. In addition to the expansion of eligibility in Medi‑Cal through the ACA optional expansion, several other ACA‑related factors—such as the individual mandate, enrollment simplification, and outreach—were intended to increase Medi‑Cal enrollment among individuals who were previously eligible, but not enrolled. This so‑called “woodwork effect” is often referred to as the ACA mandatory expansion.

California Established a State Health Benefit Exchange. In 2010, the state enacted legislation establishing the California Health Benefit Exchange, also known as Covered California. Through Covered California, individuals and employees of participating small businesses are able to enroll in subsidized and unsubsidized health coverage. Because California opted for the ACA optional expansion, subsidized health coverage through Covered California is available to individuals with incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of the FPL. (Individuals with incomes between 100 percent and 138 percent of the FPL are ineligible for subsidized health coverage through Covered California because they are generally eligible for Medi‑Cal under the ACA optional expansion.)

In addition to administering the state’s online health insurance marketplace, Covered California screens and makes referrals for Medi‑Cal and certifies health insurance plans’ compliance with ACA requirements—for example, EHB, certain access standards, and marketing and noticing practices.

ACA Significantly Augmented Federal Funding for Health Care Coverage in California

California receives more federal funding under the ACA than any other state. Figure 4 shows that California will receive an estimated $24 billion in federal funds for programs and services authorized by the ACA in 2017‑18.

Figure 4

ACA Federal Funding to California

(In Millions)

|

Payments to the State Government—2017‑18 |

|

|

Medi‑Cal optional expansion funding |

$17,335 |

|

Other enhanced federal financial participation in Medi‑Cal |

918 |

|

Prevention and Public Health Fund grants |

60 |

|

Subtotal |

($18,313) |

|

Payments for Insured Individuals—Calendar Year 2017 |

|

|

Covered California premium subsidies |

$4,600 |

|

Subtotal |

($4,600) |

|

Payments to Insurers—Calendar Year 2017 |

|

|

Covered California cost‑sharing reductions |

$800 |

|

Subtotal |

($800) |

|

Grand Total |

$23,713 |

|

ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

|

Medi‑Cal Receives Significant Enhanced Federal Funding for ACA Optional Expansion. Nearly three‑quarters of the federal funding that California is expected to receive under the ACA in 2017‑18 ($17 billion) pays for the bulk of the costs of covering Medi‑Cal’s ACA optional expansion population. The amount of federal funding for the ACA optional expansion is as high as it is because the federal government pays 95 percent of the ACA optional expansion population’s Medi‑Cal costs in 2017.

Federal Government Provides Billions of Dollars to Help Californians Obtain Insurance Coverage Through Covered California. Much of the remaining federal funding that California is expected to receive under the ACA in 2017 ($4.6 billion) will pay for premium subsidies provided to most low‑income Californians to purchase health insurance coverage through Covered California. Health insurers in California also receive $800 million in federal funding as cost‑sharing reductions for eligible individuals with the lowest incomes.

CHIP. California’s base‑level FMAP for CHIP is 65 percent. With the ACA’s 23 percentage‑point enhancement that started in FFY 2015‑16, California’s CHIP FMAP is currently 88 percent. This enhanced CHIP rate will generate an estimated $600 million in additional federal funding for Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18.

CFCO. Most in‑home supportive services provided to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries shifted into the CFCO effective December 2011. The FMAP enhancement of 6 percentage points over the base FMAP of 50 percent for services provided through the CFCO will generate an estimated $300 million in additional federal funding for Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18.

Prevention and Public Health Fund. Though federal grant amounts vary year to year, grants to the California Department of Public Health and other state agencies from the Prevention and Public Health Fund are projected to total $60 million in 2017‑18.

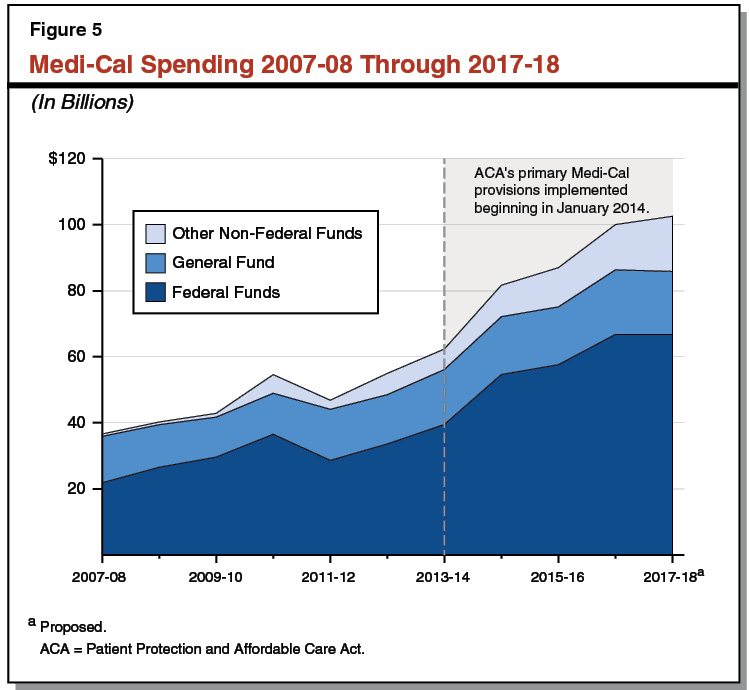

ACA‑Related Federal Funding Responsible for Much of the Growth in Medi‑Cal Spending. Figure 5 shows the increase in Medi‑Cal spending from 2007‑08 to its proposed level in 2017‑18. Since 2007‑08, federal funding for Medi‑Cal has grown from $22 billion to a proposed $67 billion in 2017‑18. About one‑third of the increase in federal funding occurred after January 2014, when much of the ACA was fully implemented. Total state spending for Medi‑Cal has grown from $15 billion in 2007‑08 to a proposed $36 billion in 2017‑18.

Changes in Health Coverage in California Under the ACA

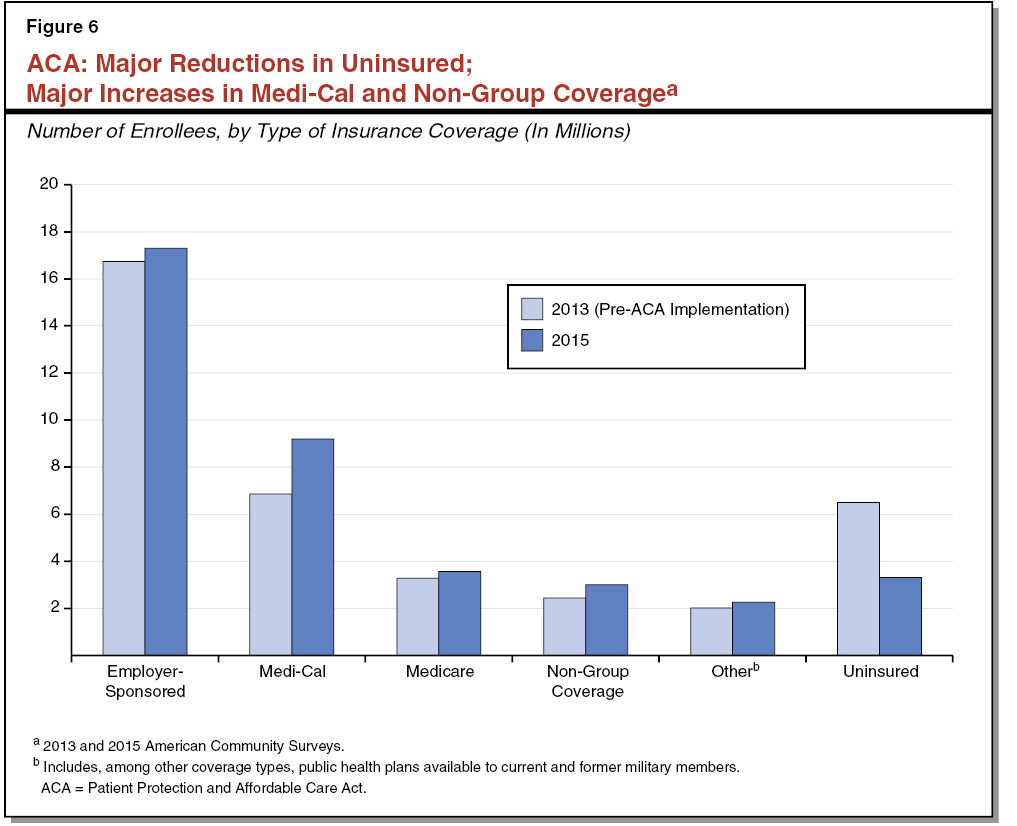

California’s Uninsured Population Has Fallen Substantially Under the ACA. Under the ACA, California has reduced the number of individuals without health insurance by the largest amount of any state. Over 6 million Californians (17 percent of the population) were uninsured in 2013, prior to the full implementation of the ACA beginning in 2014. By 2015, around 3 million Californians (just over 8 percent of the population) lacked health insurance coverage, a decrease of 50 percent from 2013. The ACA optional expansion and subsidized coverage through Covered California, in conjunction with the individual mandate and streamlined enrollment and outreach efforts, were the primary drivers of California’s significant gains in coverage. Figure 6 shows shifts in health insurance coverage types from 2013 to 2015, as well as the decrease in California’s uninsured population.

ACA Optional Expansion Led to Millions of Californians Gaining Medi‑Cal Coverage. As of June 2016, over 3 million Californians obtained health insurance coverage through the Medi‑Cal optional expansion. (In addition, Medi‑Cal enrollment among individuals who were previously eligible, but not enrolled, also likely increased.) The state’s ACA optional expansion caseload continues to grow. By June 2018, Medi‑Cal’s ACA optional expansion caseload is projected to be approximately 4 million enrollees.

Additional Gains in Insurance Coverage Due to Covered California. As of June 2016, more than 1 million Californians were enrolled in health insurance coverage through Covered California. Of those, nearly 90 percent received premium subsidies from the federal government. Health insurers also received cost‑sharing reductions for over half of Covered California’s plan enrollees. Total enrollment in health plans offered through Covered California is expected to remain roughly steady in 2017. We provide additional information on California consumers’ experience with health plan options and premiums under Covered California in the box below.

The State’s Experience Under Covered California

Nationwide, there are concerns that the number of health insurers participating in Health Benefit Exchanges has been decreasing, reducing consumers’ available health plan options as a result. For example, some states have only one health insurer offering a few plans in their state, and premiums in those and certain other states have increased substantially.

Covered California—the state’s Health Benefit Exchange—has been relatively successful at offering several different health plan options to consumers in almost all counties. A total of 11 health insurers are currently participating in Covered California, which is the third highest number of insurers participating in any Health Benefit Exchange. A consumer shopping for health plans through Covered California can typically choose from four different health plan options in any given region of the state.

Similar to the experiences of Health Benefit Exchanges nationwide, Covered California is also experiencing health insurance premium increases. The premium tax credits available under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) have only covered a small portion of the increased costs. For example, between June 2015 and June 2016, average total monthly premiums rose by $17 (from $594 to $611). Meanwhile, the average premium tax credits available to Covered California plan enrollees only increased by $3 (from $437 to $440) during this time period, which, together with the total premium increases, resulted in at least some customers paying higher out‑of‑pocket premiums. We would note that the amount of the ACA’s premium tax credits is a function of Covered California customers’ incomes and the costs of their health insurance premiums. Since customers are paying a large portion of the increased costs of their premiums, increases in their incomes are likely covering their health insurance premiums’ higher costs.

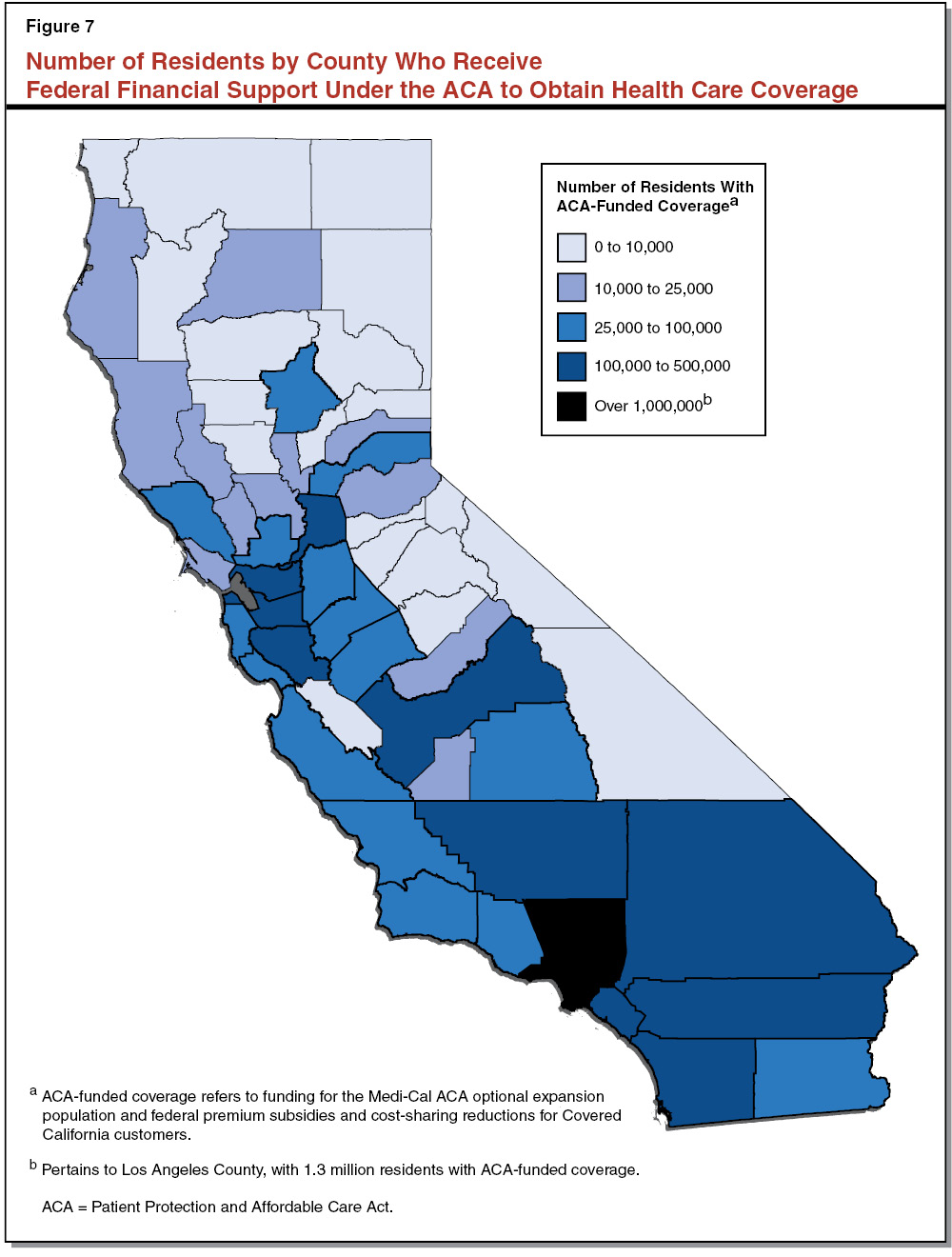

ACA Impact on Health Care Coverage Varies by County. While the overall impact of the ACA on health care coverage has been a marked increase in the number of California residents with publicly supported health care coverage, California counties have experienced varying impacts under the ACA. As of fall 2016, 4.6 million residents (12 percent) statewide had obtained ACA‑funded coverage, which we define as coverage obtained either through the ACA optional expansion or through a subsidized plan from Covered California. The state’s smaller and more rural counties, on average, have experienced the highest proportional increases in the number of individuals who receive ACA‑funded health care coverage. Despite low total numbers, Trinity, Mendocino, and Humboldt Counties have the highest percentage of residents with ACA‑funded coverage—each with 17 percent or more of their populations. Among the larger counties that have experienced particularly significant shifts in coverage under the ACA, around 13 percent of Fresno, San Bernardino, and Los Angeles Counties’ residents are enrolled in ACA‑funded health care coverage. Figure 7 shows the variation by county in the number of residents with ACA‑funded health care coverage.

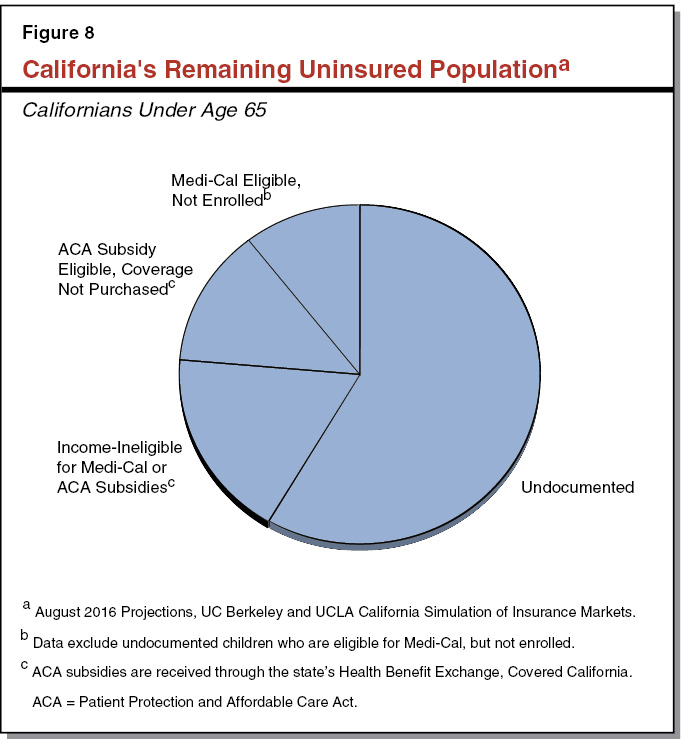

About 3 Million Californians Remain Uninsured Under the ACA. Figure 8 identifies the remaining 3 million uninsured individuals in California by their immigration status and income eligibility for different types of health insurance coverage. In 2017, 1.8 million (58 percent) of the remaining 3 million uninsured statewide under age 65 are projected to be undocumented adults. Undocumented children under the age of 19 became eligible for full‑scope Medi‑Cal in 2016 under a new state‑only program authorized by the Legislature. The remaining 1.2 million uninsured state residents generally represent those who have not been induced by the ACA’s various reforms, including the individual mandate and expanded eligibility for publicly funded coverage, to obtain health care coverage.

ACA Shifted What Types of Health Care Coverage Californians Obtain. In addition to reducing the number of uninsured Californians, the ACA has caused a significant shift in the types of health care coverage that state residents obtain. While the number of uninsured individuals in the state has declined from 17 percent to around 8 percent of the population from 2013 to 2015, during this same period the percent of the population enrolled in Medi‑Cal has increased from under 20 percent to almost 25 percent. Further significant growth in Medi‑Cal enrollment is expected through 2017, at which time over one‑third of the state’s total population is estimated to be enrolled. California’s individual and small group health insurance market, which includes Covered California, has also expanded. In 2015, around 8 percent of state residents had non‑group health care coverage purchased through the individual and small group health insurance market, up from around 6 percent of Californians in 2013. Other forms of health care coverage, most notably employer‑sponsored insurance and Medicare coverage, have not experienced as high of proportional gains in enrollment as Medi‑Cal and the individual and small group insurance market. Thus, there has been a downward shift in the proportion of Californians with employer‑sponsored health insurance and an upward shift in the proportion of Californians with health care coverage that is directly supported by federal funding under the ACA.

State Assumed Greater Role in Paying for Health Care Coverage Under the ACA

Prior to the ACA, local governments—primarily counties—shared the responsibility of providing health care services to low‑income individuals, including childless adults previously ineligible for Medi‑Cal. To help counties pay for these services the state gave counties a dedicated funding stream—referred to as realignment revenues—comprising a portion of state sales tax and vehicle license fee revenues.

Some Costs of Providing Indigent Health Coverage Shifted From Counties to the State. Many formerly uninsured, low‑income state residents obtained health care coverage through the ACA optional expansion, the ACA mandatory expansion, or through subsidized health insurance available through Covered California. This caused counties to experience a reduction in the number of uninsured Californians who rely on county indigent health care programs, reducing counties’ costs of serving the indigent population. At the same time, state health care costs have increased significantly, reflecting (1) the state’s share of cost for the ACA optional expansion population and (2) higher Medi‑Cal enrollment due to the ACA’s individual mandate and the streamlining of Medi‑Cal eligibility and enrollment processes.

As a Result, State Redirected Some County Indigent Health Care Funding to the State. In anticipation of these reduced county health care expenditures, the state enacted Chapter 24 of 2013 (AB 85, Committee on Budget), which redirects a portion of the revenues previously dedicated to county indigent health programs to offset other annual General Fund costs.

Counties Maintain Indigent Health Programs for Remaining Uninsured. As required under current law, counties continue to administer indigent health care programs to serve a portion of the remaining uninsured, numbering approximately 3 million residents statewide. Adults whose immigration status makes them ineligible for comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage are likely among the primary populations that continue to utilize county indigent health care services.

ACA’s Impact on the State Economy and Workforce

In addition to the many changes to state health insurance markets, to how the state pays for health care, and to how Californians access health care, the ACA has had a varied impact on the state’s economy and workforce.

Growth in California’s Health Care Sector. The ACA resulted in a greater amount of federal and state funding to help Californians obtain health care coverage, likely leading to increases in the state’s health care workforce and a relative increase in the size of the state’s health care sector compared to other areas of the state’s economy. Between 2010 and 2015, when the health care sector was preparing for and beginning implementation of major components of the ACA, the number of Californians employed in health care‑related jobs increased by approximately 150,000, a faster rate of growth than for employment across all sectors in the state. Similarly, the size of the health care sector grew at a faster rate than the California economy as a whole during this same time period. However, it is difficult to determine what changes in California’s economy and workforce are uniquely attributable to the ACA.

Possible Reduction in Total Worker Hours Due to the ACA. The CBO has estimated that the ACA would have the effect of reducing the total amount of hours worked nationwide. These projections of reduced total hours relate, for example, to the phasing down of federal financial support for health care coverage as individuals’ earnings increase as well as the ACA components that make it easier for individuals to obtain health insurance through avenues other than employment. Based on CBO’s nationwide estimates, we estimate that by 2025 the ACA, if it remains largely unchanged, might result in fewer full‑time equivalent jobs numbering in the low hundreds of thousands in California than would exist in 2025 absent the ACA. We would note that this estimate is uncertain.

Back to the TopThe ACA’s Uncertain Future—What Changes to the ACA Could Mean for California

New Federal Administration and Congressional Majority Support Changes to ACA

The new federal presidential administration and congressional majority leaders have stated an intent to repeal (or at least make major changes to) the ACA and have taken procedural steps to begin doing so. However, there remains substantial uncertainty as to which, if any, of the components of the ACA will ultimately be repealed or changed and what, if any, “repair” or replacement plan will ultimately be enacted. In this section, we summarize what actions the executive and legislative branches have already taken related to changing the ACA, how procedures to repeal major components of the law differ in process and difficulty, and what repeal and/or replacement of the major ACA components most at risk for change could mean for California.

Use of President’s Executive Authority to Impact ACA Implementation

Federal Administration Has Some Discretion in the Enforcement of Federal Laws. Among its many other powers and responsibilities, the federal administration has significant discretion when it comes to enforcing and implementing federal laws. For example, the administration may temporarily refrain from enforcing a new law in order to ensure that the transition to the new law does not result in undue hardship. Selective enforcement of federal law by the administration is generally limited, however, given the executive branch’s duty under the U.S. Constitution to ensure that the laws be faithfully executed.

Uncertainty Regarding What Parts of the ACA Could Be Undone Through Executive Action. The new administration issued an executive order authorizing all federal departments and agencies to waive, delay, grant exemptions from, or delay the implementation of ACA requirements that pose a burden on U.S. states or residents. It is uncertain at this time, however, which parts of the ACA might be impacted by the executive order and how much discretion would be afforded by the courts to the presidential administration to refrain from enforcing portions of the ACA.

Use of Budget Reconciliation Process to Make Changes to the ACA

General Congressional Procedures. According to established legislative practice, a bill that passes both houses of Congress by a simple majority of votes (50 percent plus one) in each house and is approved by the President becomes federal law. The U.S. Constitution affords each house the power to establish its own procedural rules. Under current Senate rules, 60 votes are generally required to end debate and proceed to a vote on a bill. In effect, this procedural rule has resulted in 60 votes being needed for certain bills to pass the Senate.

Budget Reconciliation Process Allows Certain Bills to Move Through Senate by Simple Majority Vote to End Debate. Although Senate rules practically require 60 votes, current Senate rules also allow for what is called the budget reconciliation process, which allows the Senate to bypass the 60‑vote rule to end debate and approve legislation that has significant budget implications with a simple majority vote. Restrictions exist for what may be included in a budget reconciliation bill, restrictions that are collectively known as the Byrd Rule. Among other restrictions, the Byrd Rule requires that every provision in a budget reconciliation bill directly affect federal revenue or spending and that the overall budget reconciliation bill not increase the federal deficit in the long term. Finally, the Byrd Rule allows provisions that do not meet the budget reconciliation process’s requirements to be removed individually, rather than blocking the entire bill. Recent examples of congressional use of budget reconciliation to pass significant legislation include the enactment of certain final provisions of the ACA and the reforms that converted the former federal welfare entitlement program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), into the federal block grant program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Use of the Budget Reconciliation Process to Make Changes to the ACA. The budget reconciliation process allows a simple Senate majority to limit debate and pass legislation that repeals those provisions of the ACA that have a direct impact on the federal budget. Full repeal of the ACA would not be permitted under the budget reconciliation process because (1) provisions without a direct impact on the budget could not be included in the bill and (2) doing so would increase the long‑term deficit. As of February 2017, congressional Republicans initiated the first steps of the budget reconciliation process, paving the way for possible changes to the ACA. It is uncertain at this time, however, what changes to the ACA could ultimately be included in a budget reconciliation bill if one is enacted by Congress.

Nonetheless, the case of last year’s budget reconciliation bill, known as H.R. 3762, is instructive. H.R. 3762, or the Restoring Americans’ Healthcare Freedom Reconciliation Act, would have repealed major provisions of the ACA but was vetoed by the former president. Figure 9 summarizes several of the major ACA provisions that were either included in or explicitly excluded from H.R. 3762, indicating which major ACA provisions are likely eligible and ineligible for repeal through a budget reconciliation bill.

Figure 9

Which Major ACA Provisions Could Potentially Be Changed Using Budget Reconciliation Process?

|

Provisions |

Can Be Changed Using Budget Reconciliation Process? |

|

Medicaid optional expansion under the ACA |

Yes |

|

Health insurance premium subsidy tax credits and cost‑sharing reductions through the Health Benefit Exchanges |

Yes |

|

ACA taxes, including the individual and employer mandate tax penalties |

Yes |

|

Prohibition against denying health coverage to individuals with preexisting conditions |

No |

|

Ability to remain on parents’ insurance plans through age 26 |

No |

|

Requirements on which benefits must be included in a health insurance plan |

No |

|

ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

|

Potential Impact of Changes to Major Components of the ACA on California

ACA Provisions Most at Risk for Repeal—Setting the Stage for What Is “At Stake” . . . Significant uncertainty surrounds the possible repeal and replacement of, or the making of major changes to, the ACA, including the potential impact on California of changes to the ACA. Congressional procedures such as the budget reconciliation process, for example, could facilitate the repeal of certain major components of the ACA. Some of the components potentially subject to repeal—as evidenced by H.R. 3762—include federal funding for the ACA optional expansion, federal funding for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through Health Benefit Exchanges, enhanced federal funding for other health care programs and services in Medicaid, and the individual and employer mandate tax penalties. Changes to these ACA components—absent replacement policies—would have significant consequences for California including, but not limited to:

- The potential loss of as much as $18 billion in annual federal funding for Medi‑Cal.

- The uncertain survival of Covered California absent premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions of $5.4 billion annually.

- A potentially considerable increase in the number of uninsured Californians. The costs of providing health care to this population could shift back to the state and counties.

- A possible disruption of the commercial health insurance market, particularly if insurance market reforms such as the prohibition on preexisting condition exclusions were maintained absent the ACA’s individual and employer mandates.

- A potentially significant loss in overall state economic activity and employment, especially in the short term, and potentially long‑term losses in employment in the health care sector.

. . . But Ultimate Impact of ACA Changes to California Is Highly Uncertain. Though some of the proposed changes to major components of the ACA would have significant consequences for California, it remains unclear which (if any) of the ACA’s provisions will be repealed and at what time the repealed provisions would become inoperative. Congressional Republicans have offered several replacement proposals that build off of the repeal of some or all of the ACA. Whether any of those proposals are enacted, and on what timeline, is unknown. Given the substantial uncertainty around a possible ACA repeal and/or replacement, any proposed changes to the law will need to be evaluated in their entirety to best determine how they will affect California. To inform a later evaluation of any changes to the ACA, we identify common themes from several of the Republican ACA replacement plans and provide preliminary assessments of their potential state impacts.

Back to the TopCommon Themes of Republican ACA Replacement Plans

Over the past several years, Republican congressional members have proposed a number of plans to replace (or change) components of the ACA. Many of the plans have common themes:

- Continue Use of the Tax System to Make Health Coverage Available. Republican health reform proposals generally continue to use the tax system to try to make insurance more affordable for consumers. Under consideration are health care tax credits that would continue to cover a portion of individuals’ health insurance costs, but differ in structure and generosity from those available under the ACA.

- Aim to Increase Competition and Choice While Reducing Costs. In concept, many of the proposed health care reforms aim to increase competition and remove or reduce certain regulations that govern health insurance markets and products. The intent is that health care policy reforms, such as facilitating the interstate sale of health insurance and removing regulations that limit the availability of low‑premium, high‑cost‑sharing plans, would lead to greater consumer choice and reduced costs. Such market‑based changes could have a significant effect on health insurance markets in California. Individuals with higher levels of risk tolerance could more easily obtain low‑premium, high‑cost‑sharing health insurance coverage. This added consumer choice could have implications for the health insurance prices paid by other groups of people with different risk preferences and health care needs.

- Promote Flexibility for State Medicaid Programs. Republican congressional leaders seek to promote greater flexibility for states to modify their Medicaid programs. By converting Medicaid into a block grant or per capita allotment structure, states could be afforded additional discretion to, for example, enact work requirements or, alternatively, keep their existing Medicaid rules largely intact. We discuss this in greater detail below.

- Reduce Growth in Federal Health Care Expenditures. It is our initial assessment that most Republican reform proposals support some amount of reduction in federal funding for health care coverage, at least in the long term. Proposals such as limits on the excludability of employer‑sponsored insurance in employees’ taxable income, less generous health care tax credits, and the conversion of Medicaid into a block grant or per capita allotment program all serve the intent of reduced federal spending on health care coverage.

Below, we discuss the changes to federal health care policy that appear frequently in Republican health care reform proposals. In some cases, we provide a preliminary assessment of how these reforms could affect California state government and residents. Figure 10 summarizes some of the primary elements of Republican ACA replacement plans. We organize these elements into three categories: changes to tax treatment of health insurance coverage, changes to rules governing health insurance, and changes to publicly funded health care programs. Finally, we note that while we have separated out the various elements of a possible health care reform package, all the individual reforms discussed below would affect and, in turn, be affected by each of the other individual reforms. As such, understanding the full potential impacts on California is a challenge without a complete reform proposal.

Figure 10

Summary of Common Elements From Republican ACA Replacement Plans

|

Changes to Tax Treatment of Health Care Coverage |

|

|

|

|

Changes to Rules Governing Health Insurance |

|

|

|

|

|

Changes to Publicly Funded Health Care Programs |

|

|

|

ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

Replace ACA Premium Tax Credits and Cost‑Sharing Reductions With Alternative Health Care Tax Credit Structure

Tax Credits for Health Insurance Coverage. A common feature among Republican health policy reform proposals is the establishment of an alternative health care tax credit for individuals who do not receive employer‑sponsored health insurance that would replace the premium tax credits and cost‑sharing reductions established by the ACA. These alternative health care tax credits could be used to pay for health insurance premiums as well as other out‑of‑pocket medical expenses. Under certain Republican proposals, and similar to the ACA’s premium tax credits, the health care tax credits would be advanceable—so taxpayers would receive the benefit of the tax credit prior to filing their taxes—and refundable—so individuals could receive the tax credit even if they had no federally taxable income or their income was less than the amount of the credit.

Health Care Tax Credits Would Not Necessarily Vary According to Costs of Premiums. The proposed health care tax credits generally differ from those in the ACA in one major respect. As previously discussed, the ACA’s premium tax credits are designed to equal an amount that the ensures that an eligible individual’s out‑of‑pocket health insurance premiums do not exceed certain percentages of her or his income. This results in the size of the tax credit being adjusted both by income and the premium costs of a qualifying health insurance plan. Under Republicans’ existing tax credit proposals, the amount of the tax credit might vary by such factors as income and age, but would not vary according to the cost of available health insurance premiums.

LAO Preliminary Assessment

There currently is no consensus among Republican policymakers around the design of an alternative health care tax credit. As such, it is difficult to assess the impact of converting to an alternative health care tax credit structure without a specific proposal detailing such factors as (1) who will be eligible for the tax credit; (2) how much the tax credit will be; (3) what the tax credit’s allowable uses are; and (4) how the tax credit will vary according to such factors as income, age, and family size.

Amount of Health Care Tax Credit Could Be Lower Than ACA Premium Subsidies and Cost‑Sharing Reductions. Previous Republican health care reform proposals generally set lower health care tax credit amounts than what is available in federal financial support for commercial health coverage through the ACA. For example, the proposed federal Empowering Patients First Act of 2015, supported by the new Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, set the health care tax credit at between $900 and $3,000 per year depending on the recipient’s age. In contrast, the average Covered California customer’s premium tax credit in 2016 was around $3,700, which does not include the additional cost‑sharing reductions available through Covered California. Ultimately, the amount of the health care tax credit would determine how much of an individual’s premiums and out‑of‑pocket medical costs would be financed by the federal government.

Alternative Health Care Tax Credit Could Restrain Growth in Health Insurance Costs. By not increasing the amount of the tax credits in accordance with increases in the costs of premiums, the alternative health care tax credits could reduce growth in federal health care expenditures. As a consequence, in the future the alternative health care tax credits could cover a relatively smaller portion of individuals’ health insurance premiums while also inducing others to switch to lower premium plans.

Encourage the Use of Health Savings Accounts (HSAs)

Individuals Can Use HSAs to Save for Medical Expenses, Insurance Deductibles, and Other Health Care‑Related Costs. Under current federal law, individuals or employers can deposit funds (pre‑tax income of the employee) into and take distributions from HSAs for qualifying medical expenses without additional tax liability. HSA contributions and “catch‑up” payments—increased contributions once an individual reaches a certain age—are subject to annual limits. Accrued interest and earnings in an HSA are also tax‑free under current federal law. Current state law differs from federal law in that HSA contributions, interest, and earnings (but not distributions) are subject to the state income tax. Federal law requires that consumers use HSAs in accompaniment with high‑deductible health insurance plans, which offer individuals lower monthly premium costs. Republican replacement proposals suggest HSAs encourage individuals to compare prices for procedures at different facilities in order to reduce their own expenses paid through their HSAs.

Replacement Proposals Differ in How They Encourage Use of HSAs. To encourage the use of HSAs, some Republican replacement proposals offer tax credits to individuals for contributions into an HSA. (The tax credit could either be some portion of the alternative health care tax credit discussed above or a separate tax credit.) Others propose to increase contribution limits and limits on catch‑up payments for older individuals or spouses. Many expand permissible uses of HSAs—for example, to include the payment of insurance premiums. A few suggest that government program beneficiaries such as Medicare‑ or Medicaid‑eligible individuals pay monthly premiums that would be deposited into HSAs for the beneficiary’s use.

LAO Preliminary Assessment

Changes in HSA Financing Arrangements and Rules Could Determine Which Individuals Benefit and by How Much. How HSAs are structured, and what current HSA rules are changed, would determine which individuals benefit from HSAs and by what amount. If the HSA structure (and funding for it) remain substantially similar to today—a defined purpose, tax‑advantaged savings account—individuals who have money to save for qualifying health expenses are more able to benefit than those who do not. Increasing contribution limits and allowing catch‑up payments could further benefit those who have money to save in HSAs.

Contributions to HSAs could also be federally funded. For example, individuals could receive refundable tax credits to purchase health insurance coverage. If individuals do not use the entire tax credit to purchase coverage, the remaining tax credit could be deposited into an HSA. Individuals would then use HSAs to pay deductibles and other costs. How much individuals benefit from HSAs would then depend on the amount of the tax credit. The larger the tax credit, the greater potential remaining tax credit in the HSA. (Alternatively, individuals could purchase more comprehensive coverage with lower deductibles and other costs.) How federal changes to HSAs affected individuals would depend on who qualifies for an HSA and the amount of federal funding deposited into accounts. (Given differences in federal and state tax treatment of HSAs, the Legislature might consider conforming changes in state law should federal changes to HSAs be proposed.)

Limit the Tax Excludability of Employer‑Sponsored Health Benefits

Limits on the Tax Exclusion of Employer‑Sponsored Health Benefits Designed to Replace ACA’s Cadillac Tax. Current federal law excludes employer‑sponsored health insurance contributions from workers’ taxable income. Multiple Republican health care reform proposals have included caps on the dollar amount of these employer contributions that can be excluded, though there currently is no consensus on the dollar amount of the cap.

Limits on the excludability of employer‑sponsored coverage would serve the same purpose as the ACA’s Cadillac tax, which, once implemented under current law, would place a 40 percent excise tax on employer‑sponsored health insurance plans that cost over $10,200 for individuals and $27,500 for families. Both limited excludability and the Cadillac tax would remove the incentive to increase, past a certain threshold, the portion of workers’ total compensation that is paid in the form of employer‑sponsored health insurance contributions as opposed to wages or other benefits. The primary distinction between the two approaches would be that under the tax exclusion, the tax on health insurance contributions that exceed the statutory limit would depend on the income of the individual, whereas the Cadillac tax applies a standard 40 percent tax on the total cost of the health insurance benefit over the statutory limit.

Require Continuous Health Insurance Coverage

ACA Requires Guaranteed Availability and Renewability of Coverage Without Exclusions. All health insurers are required by the ACA to accept all employers and individuals that apply for health insurance coverage; to guarantee renewal of that coverage regardless of an enrollee’s health status, service use, or other related factors; and to provide coverage irrespective of an enrollee’s preexisting health conditions. (Grandfathered plans are exempt from the preexisting condition exclusion ban.) Consumers who switch from one source of coverage to another are not precluded from obtaining coverage or from any of the consumer protections under the ACA.

Some Replacement Proposals Require Continuous Health Insurance Coverage to Avoid Certain Underwriting Practices. Several Republican replacement proposals permit the use of preexisting condition exclusions and other medical underwriting practices should an individual fail to maintain continuous health insurance coverage. If an individual changes employment and experiences a lapse in coverage, for example, health insurers could then evaluate the individual’s health history and potentially charge higher premiums. For those who could not afford the higher premiums, some replacement plans propose increased federal funding for state high‑risk pools to provide coverage to individuals with preexisting conditions. As an alternative to strict continuous coverage requirements, one replacement proposal provides an open enrollment period in which individuals could obtain coverage regardless of their health status. Individuals would then be required to maintain continuous coverage outside of the open enrollment period to avoid medical underwriting.

Continuous Health Insurance Coverage Rules Could Encourage Individuals to Stay Insured. Individuals with preexisting conditions who might have otherwise decided not to maintain coverage may do so to avoid preexisting condition exclusions. For this reason, several replacement proposals see continuous health insurance coverage as one alternative to the ACA’s individual mandate.

LAO Preliminary Assessment

Continuous Coverage Requirements Could Lead to Higher Premiums for Affected Individuals. Individuals with preexisting medical conditions who do not maintain coverage—for example, because of a loss of employment and a delay in enrollment—could face higher premiums. If they cannot afford the higher premiums, individuals could purchase other coverage with fewer benefits, apply for coverage through a state’s high‑risk pool (if available), or go uninsured. If individuals seek coverage through a state’s high‑risk pool, public funding for high‑risk pools would likely be required to reduce premiums and avoid some individuals being place on waiting lists. How continuous coverage requirements are applied could affect the insurance markets in different ways. For example, insurance regulations could include a grace period for short lapses in coverage, which could preclude insurers from considering preexisting conditions before offering coverage.

Remove ACA Requirements on EHB

Current EHB Requirements Attempt to Standardize Insurance Products. The ACA requires small group and individual health insurance plans (including those offering coverage on the Health Benefit Exchanges) to cover ten categories of EHB. This requirement helps standardize benefits across plans.

Replacement Proposals Eliminate EHB Requirements With Intent to Offer Health Insurance Products With Lower Monthly Premiums. Many Republican replacement plans propose to eliminate EHB requirements and to provide health insurers with discretion to develop health insurance plans with the same or fewer categories of benefits. Proponents of eliminating EHB requirements argue plans with fewer benefits would reduce monthly premiums for individuals who do not need one or more EHB.

LAO Preliminary Assessment

Fewer EHB Would Create More Variation in Insurance Products. Eliminating EHB requirements and allowing health insurers to develop insurance products with different categories of benefits would lead to greater variation in both the number of and the comprehensiveness of insurance products. Consumers might have more difficulty understanding what benefits are included in the insurance products that are offered, reflecting the lack of standardization requirements for insurance products. However, there could be opportunities for additional monthly savings from lower premium costs. One important consideration is how employers and individuals select from available insurance products. A 2016 analysis of how consumers selected different health plans offered through Covered California showed that individuals responded to small increases in plan purchase prices and premiums by shifting to lower‑cost plans. Consumers were often unfamiliar with annual deductibles, available benefits, or cost‑sharing arrangements in different insurance products, and made decisions often based primarily on premiums. While most of the individuals who enroll in coverage through Covered California are low‑income, individuals in the commercial insurance market have also been shown to choose insurance products primarily based on price. Removing EHB from insurance products could lead individuals to choose lower‑cost coverage without understanding that their old and new plans offer different benefit packages.

Facilitate the Use of Catastrophic Health Insurance Coverage

ACA Limits Availability of Catastrophic Coverage. Catastrophic health insurance plans pay less of an individual’s routine health care costs, but protect against the costs of serious health events. As a result, such plans reduce monthly premiums and increase deductibles and out‑of‑pocket costs. (The availability of HSAs is often linked with catastrophic plans as a mechanism to help with these higher costs.) The ACA currently allows catastrophic coverage in a limited set of circumstances—individuals must be under age 30 and qualify for a hardship exemption. Catastrophic coverage under the ACA, however, is required to provide the same EHB but sets a higher annual deductible.

Replacement Proposals Eliminate Restrictions on Catastrophic Coverage. Republican replacement proposals generally allow health insurers to provide catastrophic coverage to individuals without age, benefit, or exemption restrictions. The intent of catastrophic coverage is to offer individuals with higher levels of risk tolerance another health insurance option with lower monthly premiums. (Some replacement proposals also propose to automatically enroll all individuals without health insurance in a catastrophic coverage plan as a means of providing basic universal coverage.)

LAO Preliminary Assessment

Availability of Catastrophic Coverage Would Lead to Higher Costs for Comprehensive Coverage. Healthier and younger individuals could purchase catastrophic coverage—instead of more comprehensive coverage currently offered under the ACA—at a lower monthly cost. If fewer healthy, young individuals purchase comprehensive coverage, the cost of comprehensive coverage would increase for other individuals. This increased cost would reflect the difference in available health care services and the higher utilization of these services between the healthier and younger individuals and those who require more comprehensive coverage.

Facilitate Interstate Sale of Health Insurance Plans

Current Health Care Choice Compacts Allow Interstate Sale of Health Insurance Plans Under the ACA. Health insurance plans can sell their insurance products to individuals and small businesses in more than one state through “health care choice compacts” authorized by the ACA. Health care choice compacts are interstate agreements through which health insurers can offer policies in all participating states. As of January 2017, five states—Georgia, Kentucky, Maine, Rhode Island, and Wyoming—had enacted laws permitting health insurance plans approved for issuance in other states to be sold in their state. Some states such as Kentucky and Maine identify which states can sell plans in their state. Other states such as Georgia and Wyoming allow plans approved for issuance in any state to be sold in their state. None of the five states, however, entered into a health care choice compact.

Plans Sold Through ACA Health Care Choice Compacts Must Comply With Federal and State Regulations on Health Insurance Coverage. One reason why states with laws permitting health insurance plans approved for issuance in other states to be sold in their state may not have entered into health care choice compacts is that the ACA requires health insurers who sell through these compacts to comply with federal and state regulations on health insurance coverage and be licensed to sell in each state. In addition, all ACA coverage reforms—EHB, prohibitions on preexisting condition exclusions, and guaranteed availability and renewability of coverage—still apply.

Republican Replacement Proposals Facilitate the Interstate Sale of Health Insurance Plans. Many Republican replacement proposals are designed to facilitate the interstate sale of health insurance plans. In addition to eliminating federal EHB requirements and other insurance market reforms, some of the proposals also reduce state regulation of health insurance coverage and products. Unlike under health care choice compacts, states would not be required to enter into interstate agreements to sell plans and instead could operate under the regulatory framework of the state where they are headquartered. Health insurers headquartered in states with fewer regulations on—for example, benefits and provider networks—could sell health insurance products in other states with stricter regulations. The intent of these proposals is to increase competition and lower monthly premium costs for consumers.

LAO Preliminary Assessment

Increased Facilitation of Interstate Sale of Health Insurance Plans Could Increase Competition, but Limit State Control. Allowing states to sell health insurance plans across state lines based on the regulations of the state where they are headquartered would have a number of potential ramifications. While potentially increasing competition among health insurers, there are potential trade‑offs. One such potential trade‑off is state control over health insurers and the plans they offer—including benefits, consumer protections, and financing arrangements—would be much more limited. Moreover, like with EHB and catastrophic coverage, another trade‑off could be greater variation in insurance products and higher costs for comprehensive coverage.

Convert Medicaid Into a Block Grant or Per Capita Allotment Program

Congressional Republican leaders have stated an intent to revisit the federal rules around how Medicaid is funded and operated. In particular, congressional leaders have proposed converting Medicaid into a block grant or per capita allotment program. As we noted earlier, the former federal welfare entitlement program AFDC, was converted into the federal block grant program, TANF, through the budget reconciliation process. Because of programmatic differences between Medicaid and AFDC/TANF, it is unclear whether the Medicaid program also could be converted into a block grant or per capita allotment program through the budget reconciliation process.

Potential Changes to Medi‑Cal Funding and Administration

Currently, the Federal Government Pays a Share of Medi‑Cal Costs. As previously discussed, the costs of administering Medi‑Cal, including the provision of medical services, are shared by the federal government and the state according to the state’s FMAP, which in California is 50 percent (though the federal government pays a higher percentage of the ACA optional expansion’s Medi‑Cal costs).