In this web post, we provide an overview of the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) and the level of funding proposed for the department in the Governor's 2017-18 budget. We also assess and make recommendations on four specific DSH budget proposals: (1) a $250 million shift in inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, (2) a $10.5 million proposal to activate 60 beds for Incompetent to Stand Trial patients in the Kern County Jail, (3) an $8 million dollar funding increase to staff units designed specifically for violent patients, and (4) a $6.2 million General Fund loan for DSH-Napa earthquake repairs.

LAO Contact

February 22, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Department of State Hospitals (DSH)

Overview

Department Provides Inpatient and Outpatient Mental Health Services. DSH provides inpatient mental health services at five state hospitals (Atascadero, Coalinga, Metropolitan, Napa, and Patton) and at three inpatient psychiatric programs located on the grounds of California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) prisons (Vacaville, Soledad, and Stockton). In addition, DSH provides outpatient treatment services to patients in the community. Overall, the department is currently budgeted to treat approximately 7,400 patients in its facilities and another 700 in the community. Patients at the state hospitals fall into one of two categories: civil commitments or forensic commitments. Civil commitments are generally referred to the state hospitals for treatment by counties. Forensic commitments are typically committed by the criminal justice system and include individuals classified as Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST), Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity, Mentally Disordered Offenders, or Sexually Violent Predators. In addition, three colocated DSH inpatient psychiatric programs treat inmates referred by CDCR. Currently, over 90 percent of the patient population is forensic in nature and there has been a steady increase in waitlists for forensic commitments. As of January 16, 2017, the department had more than 850 patients awaiting placement, including about 600 IST patients.

Spending Proposed to Decline by $278 Million in 2017-18. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $1.6 billion ($1.4 billion from the General Fund) for DSH operations in 2017-18, which is a decrease of $278 million (15 percent) from the 2016-17 level. This reduction is primarily due to a proposed shift of responsibility for the colocated inpatient psychiatric programs to CDCR, which we discuss in more detail below.

Inpatient Psychiatric Program Shift

LAO Bottom Line. While the Governor’s proposed shift in the responsibility of inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to CDCR is well intended, there is significant uncertainty regarding the extent to which the shift will actually achieve the desired outcomes. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and instead shift a limited number of beds on a pilot basis.

Background

Overview of Inmate Mental Health Programs. About one-third of CDCR inmates participate in an in-prison mental health program. The care given to these inmates is subject to the oversight of a special master appointed as part of the Coleman v. Brown case. (For more information on the Coleman case, please see the nearby box.) Typically, these inmates can be treated in an outpatient setting, meaning they live in a prison housing unit and receive regular mental health treatment but do not require 24-hour care. However, under certain circumstances, some inmates may require more intensive inpatient treatment. For example, if inmates are suffering from severe symptoms of a serious mental health disorder that cannot be managed by an outpatient program, they are generally sent to Mental Health Crisis Beds (MHCBs), which provide short-term housing and 24-hour care for inmates. If the inmate’s condition is stabilized in an MHCB, the inmate is generally sent back to his or her prison housing unit. If the inmate’s condition requires a more intensive level of treatment, the inmate may be admitted to an inpatient psychiatric program. Inpatient psychiatric programs provide intensive 24-hour care with the goal of preparing the inmate to return to an outpatient program. Below, we discuss inpatient psychiatric programs in greater detail.

Coleman v. Brown

In 1995, a federal court ruled in the case now referred to as Coleman v. Brown that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) was not providing constitutionally adequate mental health care to its inmates. As a result, the court appointed a Special Master to monitor and report on CDCR’s progress towards providing an adequate level of mental health care. The Special Master has identified various areas of concern, including whether inmates have access to appropriate levels of mental health treatment, such as inpatient psychiatric care.

Inpatient Psychiatric Programs. Inpatient psychiatric programs are operated in both state prisons and state hospitals. There are a total of 1,547 inpatient psychiatric beds. There are two levels of inpatient psychiatric programs:

- Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs). ICFs provide longer-term treatment for inmates who require treatment beyond what is provided in CDCR outpatient programs. Inmates with lower-security concerns are placed in low-custody ICFs, which are in dorms, while inmates with higher-security concerns are placed in high-custody ICFs, which are in cells. There are 784 ICF beds, 700 of which are high-custody ICF beds, in state prisons. In addition, there are 306 low-custody ICF beds in state hospitals.

- Acute Psychiatric Programs (APPs). APPs provide shorter-term, intensive treatment for inmates who show signs of a major mental illness or higher-level symptoms of a chronic mental illness. Currently, there are 372 APP beds, all of which are in state prisons.

In addition to these beds, there are 85 beds for women and condemned inmates in state prisons that can be operated as either ICF or APP beds, as we discuss below. As of January 2017, there was a waitlist of over 120 inmates for ICF and APP beds.

DSH Inpatient Psychiatric Programs. Almost all inpatient psychiatric programs are operated by DSH. Specifically, DSH operates a total of 1,462 beds in both state prisons and state hospitals—all but the 85 beds for women and condemned inmates. The first inpatient psychiatric program in a state prison opened at the California Medical Facility (CMF) in Vacaville in 1988. At the time, the state hospitals, rather than CDCR, were given the greater responsibility to provide treatment services to inmates because of their experience operating inpatient psychiatric hospitals. DSH currently operates inpatient psychiatric programs at three state prisons—CMF, California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton, and Salinas Valley State Prison in Soledad. In these prisons, DSH operates 1,156 ICF and APP beds at an annual cost of around $216,000 per bed. In state hospitals, DSH operates 306 ICF beds for low-custody inmates (256 beds at DSH-Atascadero and 50 beds at DSH-Coalinga). We estimate that the annual cost to operate a low-custody ICF bed in a state hospital to be about $218,000.

CDCR Inpatient Psychiatric Programs. In 2012, CDCR began providing inpatient psychiatric programs for certain inmates with the operation of a 45-bed facility for women at the California Institution for Women in Corona. In 2014, CDCR began operating a 40-bed inpatient program for condemned inmates at San Quentin State Prison in Marin County. These programs provide both ICF and APP treatment to inmates housed in cells. In addition to being operated by CDCR instead of DSH, these programs are also different in that they serve specific inmate groups (women and condemned inmates), which could significantly affect program operations and costs. The annual cost for a bed in a CDCR-operated, inpatient psychiatric program is around $301,000.

Inpatient Psychiatric Program Referral Process. When CDCR seeks to place an inmate in a DSH inpatient psychiatric bed, DSH staff must agree with CDCR’s assessment that the inmate needs inpatient care. In addition, both CDCR and DSH must agree on the location the inmate should be served in. Once both departments agree on the placement, the inmate is supposed to be transferred within 72 hours. Under the current referral process, ICF referrals take 15 business days to complete while APP referrals take 6 business days to complete. However, if there are disagreements between the departments, the placement can take longer.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes to shift responsibility for the three inpatient psychiatric programs DSH operates in state prisons to CDCR beginning in 2017-18. Accordingly, the budget proposes a transfer of $250 million (General Fund) and 1,978 positions from DSH to CDCR effective July 1, 2017. Almost 90 percent of these positions are for treatment staff, including 495 psychiatric technicians and 374 registered nurses. The remaining 10 percent are administrative positions. According to the administration, having CDCR operate these inpatient psychiatric programs would reduce the amount of time it takes for an inmate to be transferred to a program as only CDCR staff would need to approve referrals for the beds. Specifically, the administration expects that the time needed to process an ICF referral will decline from 15 business days to 9 business days and from 6 business days to 3 business days for APP referrals. (We note that the Governor has a separate proposal in CDCR’s budget to convert 74 existing outpatient mental health beds into ICF beds at CMF which would be operated by CDCR.)

CDCR plans to operate the three inpatient psychiatric programs in the same manner as DSH for two years. For example, CDCR plans to use identical staffing packages and classifications to provide care and security. The department indicates that it will assess the current staffing model during these two years and determine whether changes to these programs are necessary. We note that the Governor does not propose shifting responsibility for the 306 beds in DSH-Atascadero and DSH-Coalinga that serve low-custody ICF inmates. According to the administration, CDCR does not currently have sufficient capacity to accommodate the inmates who are housed in these beds. However, the administration indicates that the long-term plan is to shift these inmates to CDCR when capacity becomes available.

LAO Assessment

Proposed Shift Could Achieve Notable Outcomes . . . Shifting the inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to CDCR could reduce wait times and, as a result, allow inmates to be admitted to appropriate treatment programs sooner than otherwise. This could help improve the quality of care these inmates receive. In addition, the shift could generate state savings by reducing the number of days that inmates spend in MHCBs, which are more costly than inpatient psychiatric beds. The proposal could also achieve economies of scale by having only one department oversee inmate mental health beds. For example, it would reduce the need to maintain two administrative and supervisory structures and eliminate the need for staff involved in transferring inmates between CDCR and DSH.

. . . But Uncertain if Notable Outcomes Will Actually Be Achieved. While the Governor’s proposed shift in responsibility is well intended, there is significant uncertainty regarding the extent to which the shift will actually achieve the desired outcomes. Specifically, it is uncertain:

- What Will Happen to Program Costs? While the initial costs of operating inpatient psychiatric programs would not change once they are transferred to CDCR, it is uncertain how such costs might change in the long run. On the one hand, as discussed above, the proposal could reduce operational costs. On the other hand, there are reasons why it could increase costs. For example, DSH uses Medical Technical Assistants (MTAs) that combine nursing and custody responsibilities, which prevent the need for hiring two separate staff members for these functions. According to CDCR, it does not plan to use MTA positions in the long run, which would increase costs. Moreover, the cost per bed of the units currently operated by CDCR is $301,000 per year—well above the $216,000 cost per bed for the in-prison programs operated by DSH. This difference could be driven by various factors including (1) the populations served by CDCR are very different from those served by DSH and (2) there could be economies of scale achieved by DSH by operating larger programs. Despite these notable differences, the much greater cost per bed raises concern.

- How Will Quality of Care Be Affected? Given that the administration has not provided information regarding how these programs will be operated in the long term, it is unclear whether the programs will be as effective as the current programs operated by DSH. The department has indicated that it plans to operate the programs differently after two years, such as by no longer using MTA positions, but it is uncertain what other changes might occur and how those changes would affect the level of service provided.

LAO Recommendation

Reject Complete Shift and Instead Pilot Proposed Shift. Given the significant uncertainty on whether the proposed shift in responsibility would result in more cost-effective care being delivered, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and instead shift a limited number of beds over a three-year period. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature implement a pilot program in which CDCR would provide inpatient psychiatric care to a portion of inmates who would otherwise get their care from DSH. Such a pilot would allow the Legislature to determine (1) whether wait times for these programs decrease as expected, (2) what particular staffing changes need to be made and the cost of making those changes, and (3) the effectiveness of the treatment provided. We recommend that the pilot include both ICF and APP units and be operated at more than one facility. For example, CDCR could have responsibility for an APP unit at CHCF and an ICF unit at CMF. This would ensure that the pilot can test CDCR’s ability to operate multiple levels of care at multiple facilities. In addition, we recommend that the pilot include one unit that is currently being operated by DSH, and one new unit that would be operated by CDCR.

In order to ensure that the Legislature has adequate information after the completion of the pilot to determine the extent to which inpatient psychiatric program responsibilities should be shifted to CDCR, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to contract with independent research experts, such as a university, to measure key outcomes and provide an evaluation of the pilot to the Legislature by January 10, 2019. These key outcomes would include how successfully CDCR was able to return inmates to the general population without additional MHCB or inpatient psychiatric program admissions, whether wait times decreased, and the cost of the care provided. We estimate the cost of this evaluation to be around a few hundred thousand dollars.

Admission, Evaluation, and Stabilization (AES) Center

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to provide resources to treat IST patients at the Kern County Jail. In addition, we recommend the Legislature revise proposed budget trailer legislation to allow DSH to admit patients directly to any Jail-Based Competency Treatment (JBCT) program.

Background

Services for IST Patients. Under state and federal law, all individuals who face criminal charges must be mentally competent to help in their defense. By definition, an individual who is identified by the court as IST lacks the mental competency required to participate in legal proceedings. Individuals who are IST and face a felony charge are typically referred to a DSH facility to receive restoration services.

Some patients, however, are referred to JBCT programs. Under these programs, DSH contracts with counties to provide restoration treatment in county jails. JBCT programs are designed for patients who do not require the intensive level of inpatient treatment provided in state hospitals. Accordingly, patients are assessed to determine their placement status. If they do not require intensive treatment, they may be transferred to a JBCT program. If patients require such treatment, they are transferred to a state hospital. Treating patients in a JBCT program is much less costly than treating them in a state hospital. Specifically, JBCT beds cost an average of $125,000 annually while state hospital beds cost an average of $215,000 annually.

Not All Clinically Appropriate Patients Are Referred to JBCT Programs. According to DSH, not all patients that are clinically appropriate for JBCT are admitted to these programs. This is because trial court judges, rather than DSH, have final authority over whether patients are sent to JBCT programs. Accordingly, trial court judges sometimes decline to send patients to JBCT programs despite DSH’s clinical recommendation that such a placement would be appropriate for the patient. This could be, for example, because the judge believes the patient requires a higher level of care or because the public defender raised objections to the JBCT placement. When clinically appropriate patients are not placed in JBCT programs, they can end up waiting longer in jail for a bed in a DSH facility to be become available—resulting in them not receiving the necessary treatment in a timely manner and increasing the cost of the treatment they ultimately receive.

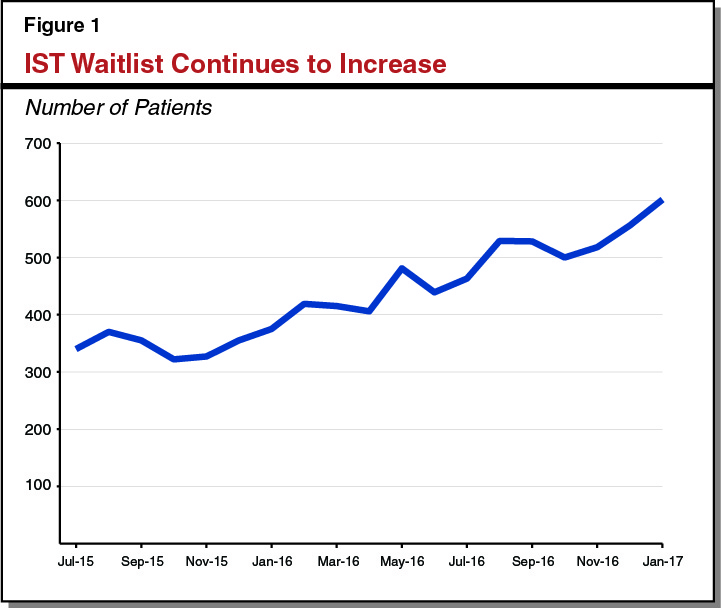

Due to Increased Referrals, IST Waitlist Growing. Over the past few years, DSH has seen an increase in IST patient referrals. However, due to limited capacity to treat all IST patient referrals, the department has not been able to treat, in a timely manner, all individuals in need of restoration services. While the number of available IST beds at DSH has increased somewhat in recent years, the number of patients awaiting treatment continues to grow. As can be seen in Figure 1, the IST waitlist has increased significantly since July 2015. As of January 2017, 601 IST patients were on the waitlist for a state hospital bed.

Patients on the waitlist are typically housed in county jails while they await placement in a DSH facility, which is problematic for two reasons. First, due to limited access to mental health treatment in some jails, these patients’ condition can worsen (“decompensate”) while they are in jail, potentially making eventual restoration of competency more difficult. Second, long waitlists can result in increased court costs and higher risk of DSH being found in contempt of court orders to admit patients. This is because DSH is required to admit patients within certain time frames and can be ordered to appear in court or be held in contempt when it fails to do so.

Governor’s Proposal

Creates New AES Center. The Governor’s budget for 2017-18 proposes to establish an AES Center, which would be located in the Kern County Jail. Specifically, the budget proposes a $10.5 million General Fund augmentation and two positions for DSH to activate 60 beds in the Kern County Jail in Bakersfield to provide restoration services for IST patients. This works out to a cost of $175,000 per bed. According to the administration, the AES Center would be used to screen jail inmates in Kern County, as well as some other Southern California counties, found to be IST and determine whether they require the intensive inpatient treatment offered at state hospitals. If a patient does not require state hospital treatment, they would be treated at the AES Center. DSH would contract with Kern County to provide custody and treatment services to patients in the center.

Budget Trailer Legislation to Admit Any Patient to the AES Center. The administration is proposing budget trailer legislation to give DSH the authority to send any patient committed to DSH to the AES Center, even if that patient is not specifically committed to the AES Center by a judge. DSH indicates that this would generally allow the department, rather than trial court judges, to determine who is appropriate for the AES Center.

LAO Assessment

Proposed AES Center Appears Virtually Identical to Existing JBCT Program. The proposed AES Center is virtually identical to a JBCT program. Like a JBCT program, the AES center would screen IST patients and treat those it finds clinically appropriate in a jail setting, at a lower cost than a state hospital. We note that, DSH indicates that the AES Center beds would cost more than average JBCT beds because the contract with Kern County would allow DSH to send some higher-security inmates to the center. However, there is no reason similar agreements could not be reached with existing or future JBCT programs.

The only meaningful difference is the proposed budget trailer legislation that would generally allow DSH to determine who would be admitted to the center. However, the language does not expand DSH’s authority to refer patients to existing JBCT programs.

LAO Recommendations

In light of the IST waitlist and the lower cost of providing treatment through the contract with Kern County, we recommend that the Legislature approve the funding and positions requested by the department. We also recommend the Legislature revise the proposed budget trailer legislation to give DSH the authority to determine who is admitted to JBCT programs as well. Such a change would help achieve the intended goals of the proposed AES Center, but in a much broader way that maximizes the number of patients that receive treatment without waiting for a bed in a state hospital and reduces future state costs.

Enhanced Treatment Program (ETP) Unit Staffing

LAO Bottom Line. Given that the pilot ETP units are authorized in statute to operate for a limited time, we recommend the Legislature approve the requested positions and funding to staff the first two pilot units on a limited-term basis, rather than on a permanent basis as proposed by the Governor. In addition, we recommend the Legislature adopt budget trailer legislation to require DSH, as part of its annual evaluation reports on ETP units, to provide information on specific key outcomes (such as whether ETP patients are able to return to the general population without additional violent incidents), in order to ensure their usefulness in determining whether ETP units should be continued and expanded in the future.

Background

Almost a quarter of DSH patients are classified as violent patients, and the department has struggled in recent years to reduce the number of violent incidents in its facilities. In order to provide a more secure housing environment for patients who have high rates of violence, Chapter 718 of 2014 (AB 1340, Achadjian) authorized DSH to pilot ETP units. Under the pilot program, the department is renovating existing beds and providing additional staff to provide more intensive and secure treatment. Each ETP unit is to operate for about four years (from the day the unit is activated to January 1 of the fifth calendar year following its activation). The goal of the pilot is to test whether more intensive care in a higher security setting for patients with a high risk of violence is an effective way to reduce violence. Chapter 718 also specified referral and staffing requirements and required the department to submit an annual evaluation report to the Legislature during the course of the pilot program. The evaluation reports are required to include specific data outlined in statute, such as information on program staffing and training, the length of time patients spend in the program and if they return after discharge, the use of restraints and seclusion, and the number of injuries to staff and patients.

A total of $13.6 million from the General Fund has been provided to DSH in prior years to construct four pilot ETP units—three units at DSH-Atascadero and one unit at DSH-Patton. DSH expects to complete construction of the first ETP unit at DSH-Atascadero in April 2018 and the second unit in August 2018. The other two units are scheduled to be activated in December 2018.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes a General Fund augmentation of $8 million and 45 additional positions in 2017-18 to staff two of the four pilot ETP units beginning in February 2018. This augmentation would increase to $15 million and 115 positions beginning in 2018-19 to reflect the full-year costs of staffing the first two pilot ETP units. It plans to activate these units immediately after construction is completed. The department reports that additional staffing requests for the other two units will be made as part of the 2018-19 budget process.

LAO Assessment

Permanent Positions and Funding Not Necessary Given Pilot Is Only for Four Years. As indicated above, the administration is requesting ongoing funding and positions to operate ETP units. However, Chapter 718 only authorizes each ETP unit to operate for four years. To the extent that the required evaluation of each ETP unit finds that the program is effective, the Legislature could consider providing ongoing funding to operate the units as part of its budget deliberations in future years. Thus, we find that it is premature at this time to provide the department permanent funding and positions for ETP units.

Required Evaluations Will Allow Legislature to Assess Whether Pilot Units Should Continue After Four Years. The statutorily required evaluations should allow the Legislature to assess the effectiveness of the ETP pilot units and the extent to which such units should continue and be expanded on an ongoing basis. While DSH is required to provide various data in the evaluation reports (such as the length of time patients spend in the program), the department is not specifically required to provide some of the key outcomes that are necessary to measure whether ETP units are effective at reducing violence in state hospitals. These key outcomes are (1) whether ETP patients are able to return to the general population without additional violent incidents, (2) the effect of ETP units on overall rates of patient violence, and (3) whether the ETP pilot units could be modified in order to improve these outcomes.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Funding and Positions on Limited-Term Basis. In view of the above, we recommend the Legislature approve the funding and associated positions for each of the first two ETP units on a limited-term basis as envisioned in Chapter 718, rather than on an ongoing basis as proposed by the Governor.

Adopt Budget Trailer Legislation to Provide Additional Detail on Required Evaluations. We recommend that the Legislature adopt budget trailer legislation to require DSH, as part of its annual evaluation reports on ETP units, to provide information on the following key outcomes: (1) whether ETP patients are able to return to the general population without additional violent incidents, (2) the effect of ETP units on overall rates of patient violence, and (3) whether ETP units could be modified to improve these outcomes.

DSH-Napa Earthquake Repairs

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal for the first two phases of the DSH-Napa repair project until DSH submits a complete cost estimate and project schedule for all three phases of the project. In addition, we recommend the Legislature direct the Department of Finance (DOF) to report on how it plans to fix an error in the budgeting for this project.

Background

Federal Grant to Cover Three-Fourths of Project Costs. DSH-Napa suffered damage as part of the 2014 South Napa Earthquake. After the earthquake, DSH requested federal funding to make repairs to buildings damaged in the earthquake. In 2015, DSH secured a grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to cover up to 75 percent of project costs once portions of the project are completed. In adopting the 2015-16 Budget Act, the Legislature approved one-time funding of $5.7 million from the General Fund to cover the state’s 25 percent share of the estimated $22.9 million project, as well as $17.2 million in reimbursement authority to allow the department to use the federal funding it expects to receive for the project. After DSH submitted a description of the project to the federal government in 2015, FEMA decided that the project could not be approved without more detailed drawings and specifications on how project repairs of historical buildings would be completed. In order to complete this additional design work, DSH spent $1 million of the $5.7 million provided in 2015-16, with the remaining $4.7 million going unspent in 2015-16. This design work is scheduled to be completed by July 2017.

Project Consists of Three Phases. DSH has divided the project into three phases. The first phase will repair three buildings identified as historically significant. The department estimates the cost of the first phase will be $6 million and be completed by July 2019. The second phase of the project will be to repair 21 buildings located outside the Secure Treatment Area (STA), which is the area where patients accused of crimes are housed. The department estimates the cost of the second phase will be $2.3 million and also be completed by July 2019. The third phase of the project will be to repair 15 buildings located within the STA. At this time, the department has not provided the cost estimate or project schedule for the third phase.

Governor’s Proposal

Funding for Construction of First Two Phases of Project. The administration is requesting a $6.2 million General Fund loan that would be repaid with federal reimbursements as phases of the project are constructed. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget also includes $6.2 million in federal reimbursement authority. The administration anticipates this funding will be sufficient to complete the first two phases of the project.

LAO Assessment

Necessary Information About Third Phase of Project Not Included. While DSH provides cost estimates and project schedules for the first two phases of the project, this same information has not been submitted for the third phase of the project. It is important for the Legislature to know how much the entire project is expected to cost and when it is scheduled to be completed before allocating funds for the construction of the first two phases.

Assumes Funding Provided in 2015-16 Remains Available for Project. As previously indicated, the Legislature appropriated $5.7 million on a one-time basis for the DSH-Napa project. However, the Governor’s budget assumes that $2.1 million from this one-time appropriation remains available to fund the state’s share of the cost for the first two phases of the project. Based on our conversations with the administration, it appears that when the 2015-16 budget was adopted, DOF erroneously entered the funding as an ongoing appropriation in its fiscal data system.

LAO Recommendation

Withhold Action Until New Funding Plan and Complete Cost Estimates and Project Schedule Are Available. Given that DSH has not submitted complete information on the third phase of the project, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action until the department submits a complete cost estimate and project schedule for all three phases of the project.

Direct DOF to Report How It Plans to Fix Error. We also recommend that the Legislature direct DOF to report at spring budget hearings on how it plans to correct the error that it acknowledges was made in reflecting the $5.7 million that was appropriated in 2015-16 as an ongoing adjustment to DSH’s base budget (rather than as a one-time appropriation as approved by the Legislature).