LAO Contacts

March 3, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Governor's Criminal Fine and Fee Proposals

- Introduction

- Background

- Governor’s Budget Proposes Various Changes

- Proposed Changes to SPF

- Proposed Increase in Resources for FTB Court‑Ordered Debt Program

- Proposed Repeal of Driver’s License Holds and Suspensions for FTP

- Appendix

Executive Summary

California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System

Individuals convicted of criminal offenses, including traffic violations, are often required to pay various fines and fees. Collection programs operated by counties and trial courts are responsible for collecting payments and are able to make use of various collection tools and sanctions to do so. The collected revenues are then deposited into a number of state and local funds, such as the State Penalty Fund (SPF), to support various programs and services. In recent years, various funds that receive such revenue have faced operational shortfalls or fund insolvency.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget includes three proposals related to the state’s criminal fine and fee system. Specifically, the budget proposes to:

- Change How Fines and Fees Are Distributed From SPF. Fine and revenue deposited into the SPF is distributed among nine other state funds, with each receiving a certain percentage under state law. The Governor proposes an alternative allocation plan that reflects the projected reduction in SPF revenues and the expiration of various one‑time offsets that were provided in the current year. Specifically, the Governor proposes to eliminate the statutory formulas dictating how SPF revenues are distributed and, instead, appropriate revenues directly to certain programs based on his priorities. Under the plan, some programs would no longer receive SPF support, while others would be reduced differently than under existing law.

- Increase Resources for Franchise Tax Board (FTB) Court‑Ordered Debt Program. Currently, collection programs can contract with FTB’s Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Program to collect court‑ordered debt. The Governor’s budget proposes a $1.1 million augmentation from the Court Collection Account for the program to maintain existing service levels and to eliminate a backlog of work.

- Repeal Driver’s License Holds and Suspensions for Failure to Pay Fines and Fees (FTP). Under existing law, courts can place a hold on an individual’s driver’s license for FTP or notify the Department of Motor Vehicles to suspend the license immediately for FTP. The Governor proposes to eliminate the ability to use driver’s license holds and suspensions as a sanction for an individual’s FTP.

LAO Recommendations

Modify Governor’s SPF Proposal to Reflect Legislative Priorities. The Governor’s proposed SPF approach is a step in the right direction in increasing state control over SPF revenue, but it is likely that the Legislature has different funding priorities. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature modify the Governor’s proposal to reflect its funding priorities by directing programs to take specific actions to implement reductions in SPF support. Alternatively, the Legislature could take a much broader approach to changing the overall distribution of fine and fee revenue by eliminating all statutory distribution formulas and depositing nearly all fine and fee revenue into the state General Fund for subsequent appropriation in the annual budget act. This would allow the Legislature to maximize its control over fine and fee revenue and ensure that annual funding for programs is based on workload and legislative priorities.

Approve Governor’s FTB Proposal. We recommend the Legislature approve the additional resources proposed for FTB’s Court‑Ordered Debt Program, as they would help maintain, and potentially, increase collections annually. We also continue to recommend the Legislature take steps to improve the overall collection process, such as by (1) implementing a new incentive structure for collections, (2) requiring improved reporting on collections, and (3) conducting an analysis to determine the collectability of outstanding fines and fees.

Weigh Trade‑Offs of Potential Changes to Driver’s License Sanction and Consider Alternatives. In considering the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature will want to weigh the relative trade‑offs in repealing the driver’s license hold and suspension sanction for FTP. While such a repeal would provide relief to such individuals, it would also negatively impact the ability of collection programs to enforce court‑ordered fines and fees. The Legislature could also consider alternatives to the Governor’s proposal in balancing these trade‑offs. In addition, we continue to recommend the Legislature require a comprehensive evaluation of collection practices and sanctions, as well as reevaluate the overall structure of the criminal fine and fee system.

Introduction

Individuals convicted of criminal offenses, including traffic violations, are often required to pay various fines and fees as part of their punishment. The revenue from these payments are deposited in a number of state and local funds to support various programs and services. As a result, the state has an interest in ensuring that these criminal fines and fees are collected in a cost‑effective manner that maximizes the amount of revenue available to support these programs. This is particularly important given that a number of the funds that receive fine and fee revenue have faced operational shortfalls in recent years.

The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget includes three specific proposals related to the state’s criminal fine and fee system. In this report, we provide a general overview of the fine and fee system and then discuss each of the Governor’s proposals. In particular, we assess the impact that each proposal would have on the system and make recommendations for legislative consideration.

Back to the TopBackground

During court proceedings, trial courts typically levy fines and fees upon individuals convicted of criminal offenses (including traffic violations). Collectively, these various criminal fines and fees are often referred to as court‑ordered debt. (Parking violations are not considered court‑ordered debt as state trial courts do not administer such violations.) As we discuss below, the state’s fine and fee system essentially consists of three distinct phases—the assessment of fines and fees, the collection of fines and fees, and the distribution of fine and fee revenue to various state and local funds.

Assessment of Fines and Fees

Trial courts are responsible for determining the total amount of fines and fees owed by individuals upon their conviction of a criminal offense. This calculation begins with a base fine that is set in state law for each criminal offense. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the base fine for the infraction of a stop sign violation is $35, while the base fine for the misdemeanor of driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs is $390. State law then requires the court to add certain charges to the base fine (such as other fines, fees, forfeitures, penalty surcharges, assessments, and restitution orders), which can significantly increase the total amount owed. State law also authorizes counties and courts to levy additional charges depending on the specific violation and other factors. Finally, statute gives judges some discretion to reduce the total amount owed by waiving or reducing certain charges. As shown in the figure, the total payment owed by an individual can be many times greater than the base fine.

Figure 1

Various Fines and Fees Substantially Add to Base Fines

As of January 1, 2017

|

How Charge Is Calculated |

Stop Sign Violation (Infraction) |

DUI of Alcohol/Drugs (Misdemeanor) |

|

|

Standard Fines and Fees |

|||

|

Base Fine |

Depends on violation |

$35 |

$390 |

|

State Penalty Assessment |

$10 for every $10 of a base finea |

40 |

390 |

|

County Penalty Assessment |

$7 for every $10 of a base finea |

28 |

273 |

|

Court Construction Penalty Assessment |

$5 for every $10 of a base finea |

20 |

195 |

|

Proposition 69 DNA Penalty Assessment |

$1 for every $10 of a base finea |

4 |

39 |

|

DNA Identification Fund Penalty Assessment |

$4 for every $10 of a base finea |

16 |

156 |

|

EMS Penalty Assessment |

$2 for every $10 of a base finea |

8 |

78 |

|

EMAT Penalty Assessment |

$4 per conviction |

4 |

4 |

|

State Surcharge |

20% of base fine |

7 |

78 |

|

Court Operations Assessment |

$40 per conviction |

40 |

40 |

|

Conviction Assessment Fee |

$35 per infraction conviction and $30 per felony or misdemeanor conviction |

35 |

30 |

|

Night Court Fee |

$1 per fine and fee imposed |

1 |

1 |

|

Restitution Fine |

$150 minimum per misdemeanor conviction and $300 minimum per felony conviction |

— |

150 |

|

Subtotals |

($238) |

($1,824) |

|

|

Examples of Additional Fines and Fees That Could Apply |

|||

|

DUI Lab Test Penalty Assessment |

Actual costs up to $50 for specific violations |

— |

$50 |

|

Alcohol Education Penalty Assessment |

Up to $50 |

— |

50 |

|

County Alcohol and Drug Program Penalty Assessment |

Up to $100 |

— |

100 |

|

Subtotals |

(—) |

($200) |

|

|

Totals |

$238 |

$2,024 |

|

|

aThe base fine is rounded up to the nearest $10 to calculate these additional charges. For example, the $35 base fine for a failure to stop would be rounded up to $40. DUI = driving under the influence; EMS = Emergency Medical Services; and EMAT = Emergency Medical Air Transportation. |

|||

Collection of Fines and Fees

Counties are statutorily responsible for collecting fine and fee payments. However, some collection duties are often delegated back to the courts. As a result, collection programs may be operated by both courts and counties. Collection programs can collect the debt themselves as well as contract with private collection vendors or the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Program. We note, however, FTB will only accept cases that meet specific parameters. For example, payment must be at least 90 days late. Currently, 54 of the state’s 58 collection programs participate in FTB’s program in some way.

Programs Employ Various Collection Tools. Individuals who choose not to contest a violation, plead guilty, or are convicted of a criminal offense must either provide full payment immediately or set up installment payments with the collection programs. Collection programs employ various tools to help individuals make timely payments. For example, some programs send monthly billing slips to individuals on installment plans or use payment kiosks.

Various Sanctions Available to Collect Debt. If an individual does not pay on time, the debt becomes delinquent. Under state law, after a minimum of a 20 calendar day notification of delinquency, collection programs can utilize sanctions against an individual who either fails to pay their fines and fees (FTP) or fails to appear in court without good cause (FTA). Typically, collection programs progressively add sanctions to gradually increase pressure on debtors to make payment. While the same sanctions are available to all collection programs, each program can vary in how it uses these sanctions and when it leverages these sanctions. Common sanctions include:

- Civil Assessment. Current law authorizes collection programs to impose a civil assessment of up to $300 for FTA or FTP.

- Wage Garnishments and Bank Levies. Collection programs may impose wage garnishments or bank levies to collect monies to address delinquent debt. For example, the FTB Court‑Ordered Debt Program identifies a debtor’s assets through automated searches of wage, employment, and financial records in order to administratively issue wage garnishments or bank levies.

- Driver’s License Holds. Under current law, courts can notify the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) to place a hold on a driver’s license for FTA or FTP. A driver’s license hold generally only prevents an individual from obtaining or renewing a license until the individual appears in court or pays the owed debt. A hold placed for FTA may be added and removed at the court’s discretion. Thus, courts use a hold for FTA as a tool to encourage individuals to contact the court. In contrast, a hold for FTP for a specific debt may only be placed once for that debt—thereby resulting in most courts leaving the hold in place until an individual pays off the debt in full. Additional holds for FTA or FTP for other criminal offenses can then result in the suspension of the license, which we discuss in more detail below. Holds will be removed by the court once an individual appears in court or makes payment to address his or her debt.

- Driver’s License Suspensions. As required under current law, DMV will suspend an individual’s license (1) if there are two or more holds or (2) if notification is received to suspend the license immediately. Individuals whose driver’s license will be subject to suspension receive notice from the DMV that their license will be suspended by a specified date if they do not address all specified holds. Individuals whose driver’s licenses are suspended are no longer legally allowed to drive. Once all holds are removed, the suspension is lifted. Individuals must then pay a fee to have their license reissued or returned.

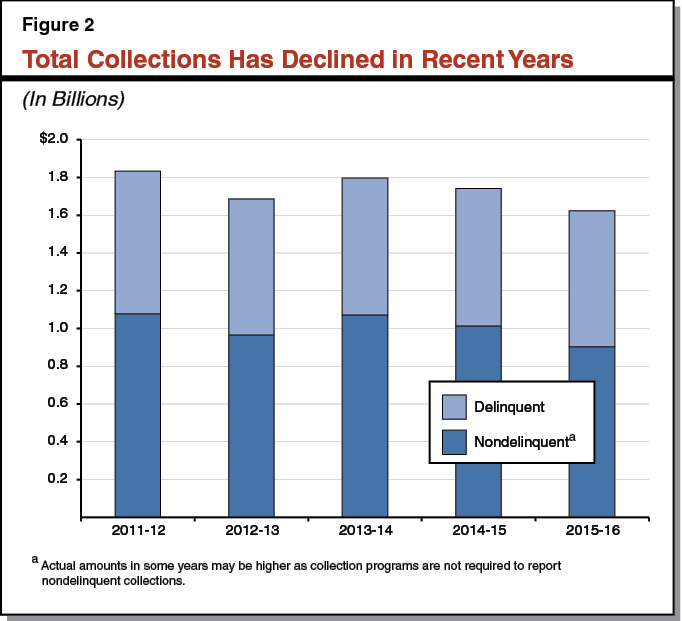

Amount Collected. Based on available data in Judicial Council reports, the total amount of criminal fines and fees collected has declined annually since 2013‑14. As shown in Figure 2, total collections decreased by nearly $200 million—from $1.8 billion in 2013‑14 to $1.6 billion in 2015‑16. The $1.6 billion consists of about $905 million (56 percent) in debt that was not delinquent and $720 million (44 percent) in delinquent debt.

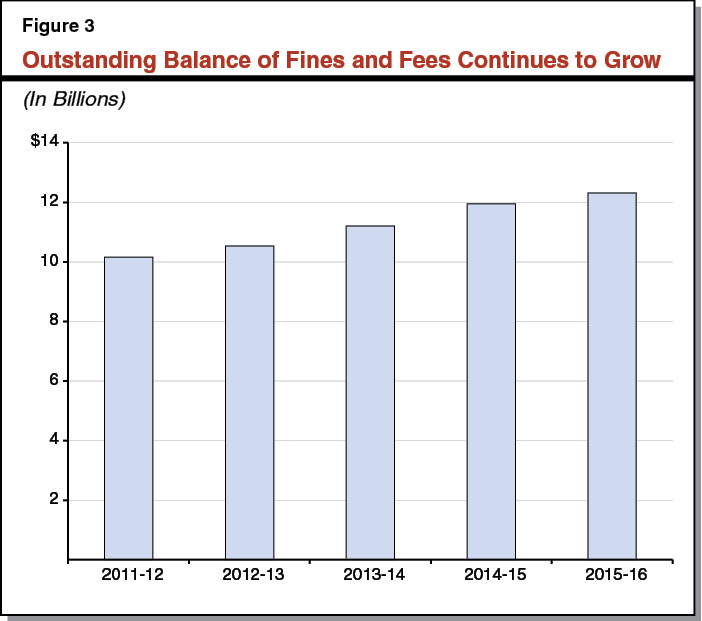

Balance of Outstanding Debt. Every year, the courts estimate the total outstanding balance of debt owed by individuals. This balance may decrease when individuals make payments or debt is resolved in an alternative manner, such as when a portion of debt is dismissed because the individual performs community service in lieu of payment. However, this amount generally grows each year as some amount of newly imposed fines and fees goes unpaid and is added to the amount of unresolved debt from prior years. As shown in Figure 3, an estimated $12.3 billion in fines and fees remained outstanding at the end of 2015‑16. We would note, however, that a large portion of this balance may not be collectable as the costs of collection could outweigh the amount that would actually be collected.

Distribution of Fines and Fees

Distribution Among Numerous State and Local Funds. State law (and county board of supervisor resolutions for certain local charges) dictates a very complex process for the distribution of fine and fee revenue to numerous state and local funds. State law requires that a portion of fines and fees be allocated to specific purposes prior to distributing revenue to various state and local funds, such as to support most collection program operational costs related to collecting delinquent debt. Additionally, state law includes some distributions that vary by criminal offense and authorizes local governments to determine how certain fines or fees are to be distributed among various local funds. Finally, as we discuss below, state law includes formulas for distributions of certain fines and fees. (For more information about how criminal fine and fee revenue is distributed, please see our January 2016 report, Improving California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System.)

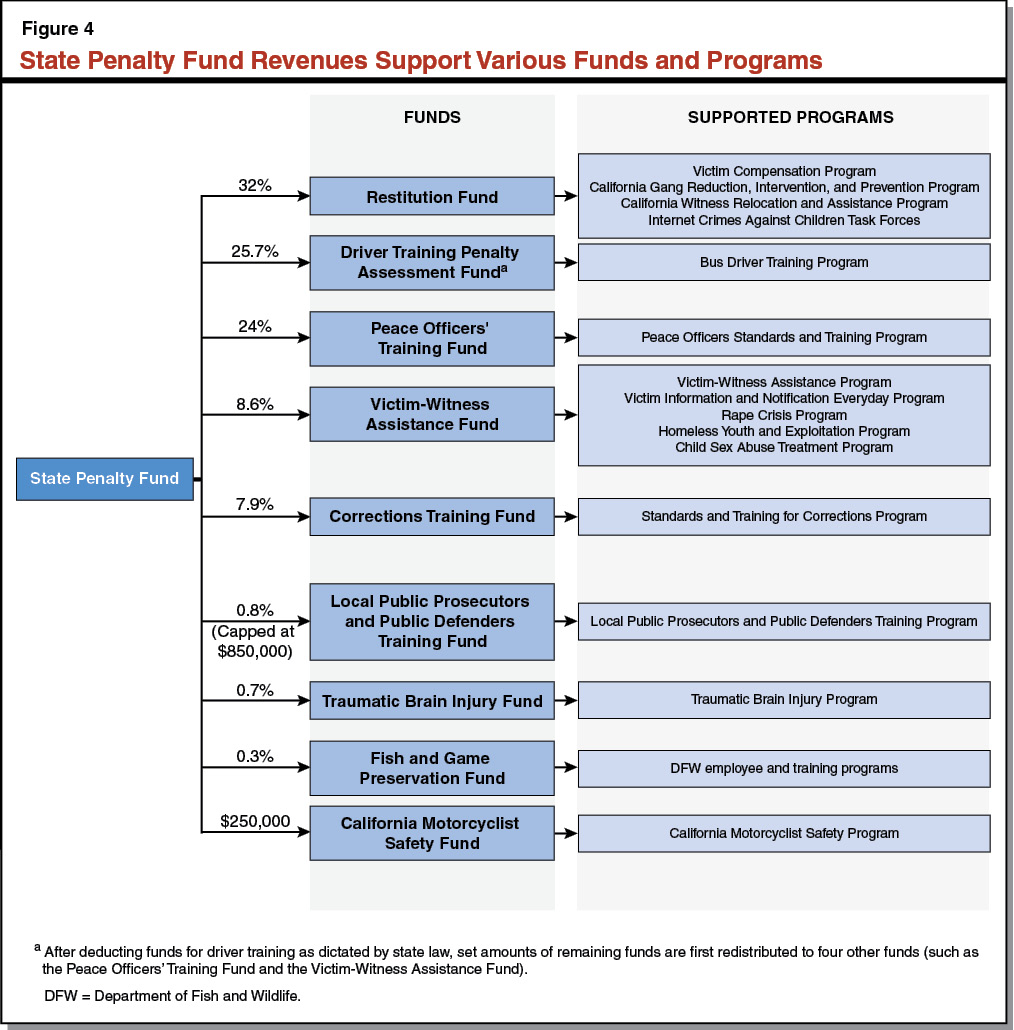

State Penalty Fund (SPF). One of the major state funds that receives criminal fine and fee revenue is the SPF. Specifically, state law requires that a $10 penalty assessment be added for every $10 of the base fine, with 70 percent of the revenue deposited into the SPF. (The remaining 30 percent is deposited into county general funds.) As shown in Figure 4, the amount deposited into the SPF is then split among nine other state funds with each receiving a certain percentage under state law. These funds, which can also receive funds from other sources, then support various state and local programs—including the state’s victim compensation program (Restitution Fund) and programs for state and local law enforcement (Peace Officers’ Training Fund and Corrections Training Fund). As shown in the figure, each of these funds primarily supports one specific program. We note that SPF revenues deposited into the Driver Training Penalty Assessment Fund are first used to support the Bus Driver Training Program, with any remaining funds reallocated to specified other SPF‑supported funds (such as the Peace Officers’ Training Fund). Figure 5 describes each of the programs that receive SPF support.

Figure 5

Programs Supported by the State Penalty Fund

|

Program |

Department |

Description |

|

Victim Compensation |

VCB |

Provides compensation to victims of violent crimes and eligible family members for various crime‑related expenses (such as medical treatment, funeral expenses, and crime scene cleanup). |

|

Victim‑Witness Assistance |

OES |

Provides grants to fund victim witness centers in each county. Centers provide multiple services such as assisting victims to navigate the criminal justice system and access other services. |

|

Victim Information and Notification Everyday |

OES |

Provides immediate, automated telephone notification on the change in custody or case status of incarcerated offenders. |

|

Rape Crisis |

OES |

Provides comprehensive services to victims of sexual assault to combat trauma and to navigate the criminal justice system. |

|

Homeless Youth and Exploitation |

OES |

Provides services to homeless youth and youth involved in sexually exploitive activities. Services include food, shelter, counseling, and referrals to other services. |

|

Child Sex Abuse Treatment |

OES |

Provides services to children who are victims of sexual abuse and appropriate family members to assist in the child’s recovery. |

|

Peace Officers Standards and Training |

POST |

Sets minimum selection and training standards for California law enforcement, develops and runs training programs, and reimburses local law enforcement for training. |

|

Standards and Training for Corrections |

BSCC |

Develops minimum standards for local correctional officer selection and training, certifies training courses for correctional staff, and reimburses local correctional agencies for some training. |

|

CalGRIP |

BSCC |

Provides grant funds to cities that engage in collaborative approaches to reducing gang and youth violence. In 2015‑16, 19 cities received grants. |

|

CalWRAP |

DOJ |

Provides reimbursements to California district attorney offices for various services required by relocated witnesses and family members (such as temporary lodging). |

|

Motorcyclist Safety |

CHP |

Funds contracts for projects that increase motorcyclist safety. |

|

Employee education and training |

DFW |

Supports employee education and training programs for the department. |

|

Bus Driver Training |

CDE |

Certifies all school bus driver instructors and all instructors of bus drivers who transport farm laborers. Awards certification to drivers who complete a three‑week classroom and driving course as well as other bus‑related activities. |

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

DOR |

Provides vocational rehabilitation and independent living services to individuals who suffer traumatic brain injuries at seven locations across California. Also provides referrals to other available services. |

|

Internet Crimes Against Children |

OES |

Provides grant funds to expand the activities (such as investigations) of five existing Internet Crimes Against Children Task Forces that respond to offenders who use the Internet or other technology to sexually exploit children. |

|

Local Public Prosecutors and Public Defenders Training |

OES |

Provides grant funds for the California District Attorneys Association and the California Public Defenders Association to provide their attorneys with statewide training, education, and research. |

|

VCB = Victim Compensation Board; OES = Office of Emergency Services; POST = Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training; BSCC = Board of State and Community Corrections; CalGRIP = California Gang Reduction, Intervention, and Prevention Program; CalWRAP = California Witness Relocation and Assistance Program; DOJ = Department of Justice; CHP = California Highway Patrol; DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife; CDE = California Department of Education; and DOR = Department of Rehabilitation. |

||

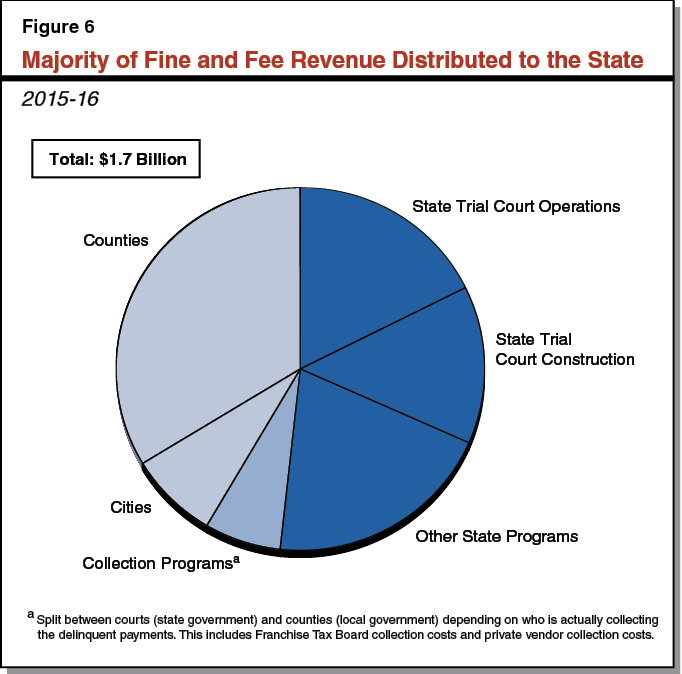

State Receives Majority of Fine and Fee Revenue. According to available data compiled by the State Controller’s Office and the judicial branch, a total of $1.7 billion in fine and fee revenue was distributed to state and local governments in 2015‑16. As shown in Figure 6, the state received $881 million (or roughly half) of all revenue distributed in 2015‑16. Of this amount, roughly 60 percent went to support trial court operations and construction.

We estimate that local governments received $707 million (or 42 percent) of the total amount of fine and fee revenue distributed in 2015‑16. The remaining $114 million (or 7 percent) went to collection programs to cover their operational costs related to the collection of delinquent debt. (A more detailed breakdown of deposits into specific state and local funds can be found in the Appendix).

Back to the TopGovernor’s Budget Proposes Various Changes

The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget includes three specific proposals related to the state’s criminal fine and fee system. Specifically, the budget proposes: (1) changing how fine and fee revenues are distributed from the SPF, (2) increasing the level of resources for the FTB Court‑Ordered Debt Program, and (3) repealing driver’s license holds and suspensions as sanctions for FTP.

Proposed Changes to SPF

Impact of Decline in SPF Revenue on Program Expenditures

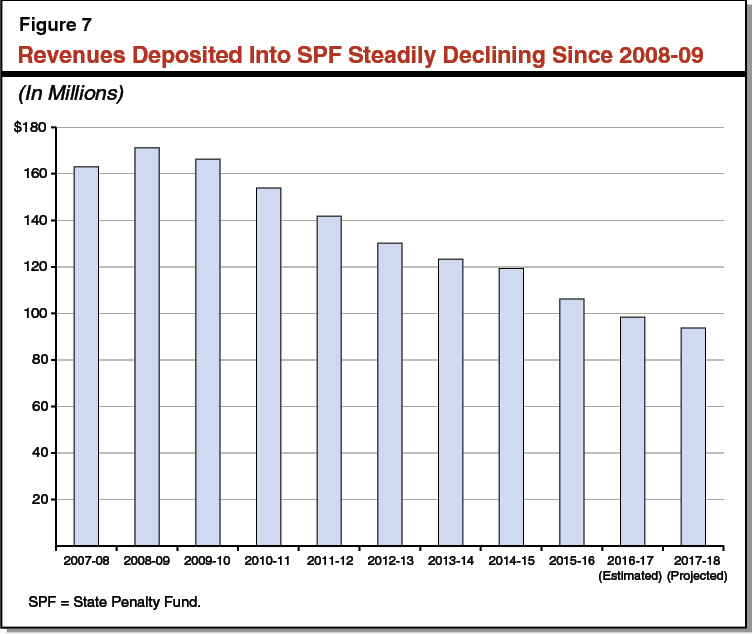

Decline in SPF Revenues. As discussed earlier, fine and fee revenue deposited into the SPF is allocated to nine different state special funds, which then support various state and local programs (such as local law enforcement). As shown in Figure 7, the amount of revenue deposited into the SPF peaked in 2008‑09 at about $170 million and has steadily declined since. (As we discuss below, in adopting the 2016‑17 budget, the Legislature appropriated on a one‑time basis General Fund monies to specific programs supported by SPF revenue to essentially backfill the projected decline in fine and fee revenue.) Total revenue deposited into the SPF in 2017‑18 is expected to be about $94 million—a decline of about 45 percent since 2008‑09.

Current‑Year SPF Program Expenditures. For 2016‑17, the administration estimates that a total of $97 million from the SPF will be spent on specific programs. It is also estimated that $209 million from other funds sources (such as other state funds and federal funds) will be spent on these programs, for a total of $306 million in current‑year expenditures (as shown in Figure 8). We note that the amount of other funds includes $19.6 million from the General Fund that was provided in 2016‑17 on a one‑time basis to backfill a projected reduction in SPF revenues—$16.5 million to the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) and $3.1 million to the Standards and Training for Corrections Program. Similarly, the 2016‑17 budget also provided $4.2 million from the Restitution Fund on a one‑time basis to backfill SPF support for various victim programs administered by the Office of Emergency Service (OES).

Figure 8

Estimated State Penalty Fund (SPF) Program Expenditures

For 2016‑17 and 2017‑18 Under Current Distribution Systema

(In Thousands)

|

Program |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

Change From 2016‑17 |

||||||

|

SPF |

Other Fundsb |

Total |

SPF |

Other Funds |

Total |

Total |

|||

|

Victim Compensation |

$15,114 |

$105,120 |

$120,234 |

$13,027 |

$107,283 |

$120,310 |

$76 |

||

|

Various OES Victim Programsc |

12,494 |

63,403 |

75,897 |

11,884 |

57,929 |

69,813 |

‑6,084 |

||

|

Peace Officers Standards and Training |

32,132 |

30,734 |

62,866 |

28,784 |

3,787 |

32,571 |

‑30,295 |

||

|

Standards and Training for Corrections |

17,418 |

3,706 |

21,124 |

16,880 |

100 |

16,980 |

‑4,144 |

||

|

CalGRIP |

9,519 |

— |

9,519 |

9,519 |

— |

9,519 |

— |

||

|

CalWRAP |

5,217 |

— |

5,217 |

5,217 |

— |

5,217 |

— |

||

|

Motorcyclist Safety |

250 |

2,941 |

3,191 |

250 |

2,941 |

3,191 |

— |

||

|

DFW employee education and training |

450 |

2,477 |

2,927 |

450 |

2,194 |

2,644 |

‑283 |

||

|

Bus Driver Training |

1,364 |

219 |

1,583 |

1,583 |

— |

1,583 |

— |

||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

998 |

64 |

1,062 |

953 |

161 |

1,114 |

52 |

||

|

Internet Crimes Against Children |

1,008 |

— |

1,008 |

1,008 |

— |

1,008 |

— |

||

|

Local Public Prosecutors and Public Defenders Training |

850 |

31 |

881 |

850 |

31 |

881 |

— |

||

|

Totals |

$96,814 |

$208,696 |

$305,510 |

$90,405 |

$174,427 |

$264,832 |

‑$40,678 |

||

|

aEstimated expenditures based on current law, historical budgeting practices, and best available data. bIncludes one‑time funding to backfill reduction in SPF revenues—$19.6 million from the General Fund and $4.2 million from the Restitution Fund. cIncludes Victim‑Witness Assistance Program, Victim Information and Notification Everyday Program, Rape Crisis Program, Homeless Youth and Exploitation Program, and Child Sex Abuse Treatment Program. OES = Office of Emergency Services; CalGRIP = California Gang Reduction, Intervention, and Prevention Program; CalWRAP = California Witness Relocation and Assistance Program; and DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

|||||||||

2017‑18 SPF Program Expenditures Expected to Decline Under Current System. As mentioned above, a total of $94 million is estimated to be deposited into the SPF in 2017‑18. Of this amount, the administration estimates that $90.4 million will be available to support various programs. (After accounting for a few other relatively minor expenditures, the SPF is expected to retain a fund balance at the end of 2017‑18 of $1.6 million.) When combined with an estimated $174 million in funding from other sources, we estimate that total expenditures on SPF‑supported programs will be almost $265 million in the budget year under the state’s current distribution system for SPF revenues. This is a decline of about $41 million (or 13 percent) from the estimated 2016‑17 level. While part of this reduction reflects a decline in revenues to SPF, a majority of it is due to the expiration of the above one‑time backfills that were provided in the current year. Figure 8 compares total program expenditures for 2016‑17 and 2017‑18 under the current distribution system. As shown in the figure, some of the programs would experience spending reductions. For example, POST expenditures would be reduced by a total of about $30 million. Under current law, programs would generally have the flexibility to take whatever steps they deem appropriate to implement expenditure reductions, such as laying off staff or halting certain activities.

Governor’s Proposal

Proposes Alternative Expenditure Plan. The Governor proposes an alternative 2017‑18 expenditure plan for programs supported by the SPF that reflects both the projected reduction in SPF revenues and the expiration of the various one‑time offsets that were provided in the current year. However, the Governor proposes to allocate SPF revenues in a manner different than required under current law, which, as we discuss below, results in different levels of reductions for certain programs. Specifically, the Governor proposes to eliminate existing statutory provisions that require the transfer of specified amounts of SPF revenue to the nine other state funds. Instead, the Governor’s budget proposes to appropriate specific dollar amounts from the SPF directly to certain programs based on the administration’s priorities.

Figure 9 summarizes the Governor’s proposed expenditure plan for 2017‑18, as compared to estimated 2016‑17 expenditures. As shown in the figure, the Governor proposes about $269 million in total expenditures for programs supported by the SPF—$90.4 million from the SPF and $178.8 million from other funds. Programs would need to reduce total expenditures by $36 million (or 12 percent) compared to the 2016‑17 level. (The estimated total level of spending from other funds in 2017‑18 under the Governor’s proposal is $4.4 million higher than estimated under the current distribution system. This is primarily because the Governor proposes a larger reduction in SPF resources for the Victim Compensation Program, which will likely be offset by an increase in expenditures from other funding sources.)

Figure 9

State Penalty Fund (SPF) Program Expenditures

For 2016‑17 and 2017‑18—Governor’s Proposal

(In Thousands)

|

Program |

2016‑17a |

2017‑18 |

Change |

||||||

|

SPF |

Other Fundsb |

Total |

SPF |

Other Funds |

Total |

Total |

|||

|

Victim Compensation |

$15,114 |

$105,120 |

$120,234 |

$9,082 |

$111,228 |

$120,310 |

$76 |

||

|

Various OES Victim Programsc |

12,494 |

63,403 |

75,897 |

12,053 |

57,929 |

69,982 |

‑5,915 |

||

|

Peace Officers Standards and Training |

32,132 |

30,734 |

62,866 |

46,496 |

3,787 |

50,283 |

‑12,583 |

||

|

Standards and Training for Corrections |

17,418 |

3,706 |

21,124 |

17,209 |

100 |

17,309 |

‑3,815 |

||

|

CalGRIP |

9,519 |

— |

9,519 |

— |

— |

— |

‑9,519 |

||

|

CalWRAP |

5,217 |

— |

5,217 |

3,277 |

— |

3,277 |

‑1,940 |

||

|

Motorcyclist Safety |

250 |

2,941 |

3,191 |

— |

3,191 |

3,191 |

— |

||

|

DFW employee education and training |

450 |

2,477 |

2,927 |

450 |

2,194 |

2,644 |

‑283 |

||

|

Bus Driver Training |

1,364 |

219 |

1,583 |

1,038 |

100 |

1,138 |

‑445 |

||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

998 |

64 |

1,062 |

800 |

314 |

1,114 |

52 |

||

|

Internet Crimes Against Children |

1,008 |

— |

1,008 |

— |

— |

— |

‑1,008 |

||

|

Local Public Prosecutors and Public Defenders Training |

850 |

31 |

881 |

— |

— |

— |

‑881 |

||

|

Totals |

$96,814 |

$208,696 |

$305,510 |

$90,405 |

$178,844 |

$269,249 |

‑$36,261 |

||

|

aEstimated expenditures based on current law, historical budgeting practices, and best available data. bIncludes one‑time funding to backfill reduction in SPF revenues—$19.6 million from the General Fund and $4.2 million from the Restitution Fund. cIncludes Victim‑Witness Assistance Program, Victim Information and Notification Everyday Program, Rape Crisis Program, Homeless Youth and Exploitation Program, and Child Sex Abuse Treatment Program. |

|||||||||

|

OES = Office of Emergency Services; CalGRIP = California Gang Reduction, Intervention, and Prevention Program; CalWRAP = California Witness Relocation and Assistance Program; and DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

|||||||||

Some Programs Eliminated, Others Reduced Differently Than Under Current System. Under the Governor’s proposal, funding for certain programs would be eliminated. Specifically, the Governor proposes to eliminate SPF funding for the (1) California Gang Reduction, Intervention, and Prevention Program; (2) Internet Crimes Against Children Taskforces; (3) Local Public Prosecutors and Public Defenders Training Program; and (4) Motorcyclist Safety Program. The Governor proposes to maintain SPF funding for the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s employee education and training programs at its current level. For the remaining programs, those that are prioritized by the administration (such as training for state and local law enforcement) would be required to address smaller expenditure reductions than they otherwise would have been required to under existing law. We also estimate that some of these programs will increase expenditures from other funds.

LAO Assessment

Helps Increase State Control Over Use of Fine and Fee Revenue . . . Our January 2016 report, Improving California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System, identified a number of key problems with the state’s existing fine and fee system. One key weakness was that it is difficult for the Legislature to control the use of fine and fee revenue due to the various statutory formulas dictating how such revenue must be allocated. The Governor’s proposal to eliminate the statutory formulas allocating SPF revenue is a step in the right direction towards helping address this weakness by increasing state control over the use of SPF revenue. Eliminating the formulas allows the state to more easily reprioritize the use of funding to those programs that are deemed to be of higher priority. For example, state and local law enforcement training programs would have been required to reduce expenditures the most under existing state law. However, the Governor’s proposal prioritizes these programs and ensures expenditure reductions are minimized—such as by eliminating support for four other programs entirely and distributing reductions across more programs. Taking this targeted approach is particularly important as the amount of fine and fee revenue deposited into the SPF can fluctuate depending on factors outside of the Legislature’s control—such as the number of citations issued by law enforcement, individual’s willingness to make payments, and the amount collected by collection programs.

. . . But Unclear What Impact Proposed Reductions Will Have. The administration’s proposal, however, does not specify how the programs would accommodate the proposed funding reductions. Rather, the budget reflects unallocated reductions to specific programs and gives the programs maximum flexibility to take whatever steps they deem appropriate to implement the reductions, which may or may not be aligned with legislative priorities. For example, it is unclear the extent to which law enforcement officers may no longer be in full compliance with training requirements due to reduced revenues to POST or the Standards and Training for Corrections program. Accordingly, the programmatic impact of the proposed reduction is unknown.

Proposal Does Not Include Plan if SPF Revenues Are Lower Than Estimated. The Governor’s budget includes an expenditure plan to allocate $90.4 million from the SPF, leaving a $1.6 million fund balance. As mentioned previously, revenue deposited into the SPF can fluctuate significantly from year to year. To the extent revenues are lower than expected in a given year, existing state law dictates how the reductions will be allocated among programs. In contrast, the Governor’s proposal does not include a plan on how a decline in estimated SPF revenue of more than $1.6 million would be accommodated. Without such a plan, the Legislature could be in a position to have to make midyear funding adjustments.

Legislature May Have Different Priorities. While the Governor’s proposal reflects the administration’s funding priorities, it is likely that the Legislature has different priorities. The Legislature could decide that different programs should be eliminated or that programs should implement different levels of expenditure reductions. For example, the Legislature could decide that victim programs are of greatest priority and should then implement fewer expenditure reductions than proposed by the Governor. In addition, the Legislature may be concerned that choices made by departments to reduce expenditures may not be consistent with its priorities. For example, the Legislature may want to ensure that departments maintain expenditures on prioritized activities, like certain types of law enforcement training.

LAO Recommendations

Modify Governor’s Proposal to Reflect Legislative Priorities. As discussed above, the Governor’s proposal to increase legislative oversight over SPF revenue is a step in the right direction. However, to address our concerns with the Governor’s proposal, we recommend the Legislature modify the Governor’s proposal to reflect its priorities. For example, the Legislature may want to target reductions at specific programs in a manner different than proposed by the Governor. Additionally, we recommend the Legislature direct programs to take specific actions in implementing the expenditure reductions—rather than giving departments complete discretion—in order to ensure that legislative priorities are maintained. For example, with respect to the California Department of Education (CDE) Bus Driver Training Program, the Legislature could direct the department to reduce specific expenditures (such as no longer providing lodging for program participants) or to operate the program more cost‑effectively (such as by increasing class size). Alternatively, the Legislature could direct programs to look for alternative funding sources to maintain expenditures. For example, CDE currently charges a $1,000 fee for its training program (as well as fees for various other services) that generates roughly $100,000 annually. This fee has not changed since 2008 and could potentially be increased to generate additional revenue to offset the proposed reduction. Finally, the Legislature could specify a plan to the extent SPF revenues are lower in 2017‑18 than projected. For example, the Legislature could approve an expenditure plan that ranks programs in priority order. To the extent revenues are lower than expected, lower priority programs would be required to implement additional expenditure reductions.

To assist the Legislature in determining its SPF funding priorities, we recommend directing each administering department to report in budget hearings on how it would implement expenditure reductions and what impact such reductions would have upon program operations under the current distribution system, as well as under the Governor’s proposal. Such information would help the Legislature determine the appropriate funding level for each program and ensure that each department plans to implement any expenditure reductions in a manner that is consistent with legislative priorities. Additionally, we recommend that the Legislature direct departments to assess whether alternative fund sources are available to support program operations. For example, OES received a substantial increase in federal funds to support crime victim assistance programs beginning in 2015, with millions of dollars of these funds subsequently allocated to the Victim‑Witness Assistance Program and the Rape Crisis Program. With an expected increase in such federal funding in the coming year, it is possible that these programs require less SPF revenues—thereby increasing the amount available to support other programs.

Alternatively, Deposit Most Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue in State General Fund. While the Governor’s proposal to change the allocation of SPF revenues would be a step in the right direction in improving the state’s fine and fee system, we continue to believe that taking a much broader approach to changing the overall distribution of fine and fee revenue would be preferable. As discussed in our January 2016 report, we find that eliminating all statutory formulas related to fines and fees would give the state maximum control over fine and fee revenue. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature require that nearly all fine and fee revenue, excluding those subject to certain legal restrictions (such as monies collected for violations of state law protecting fish and game), be deposited into the General Fund for subsequent appropriation by the Legislature in the annual state budget. Depositing all fine and fee revenue in the General Fund would allow the Legislature to maximize its control over the use of these monies and to ensure that annual funding for state and local programs is based on workload and legislative priorities. Moreover, an annual review of programmatic funding levels would facilitate periodic reviews of programs to help ensure that they are operating effectively and efficiently. In addition, any fluctuations in the collection of fine and fee revenue would no longer disproportionately impact programs supported by fines and fees. Instead, fluctuations in revenue would be addressed at a statewide level across other state programs—ensuring that adjustments in funding levels were based on statewide legislative priorities.

Depositing all fine and fee revenue into the General Fund would eliminate the need for the Legislature to continuously identify and implement short‑term solutions to address problems with various special funds currently facing or nearing structural shortfalls or insolvency. These funds include the Trial Court Trust Fund, the Improvement and Modernization Fund, the State Court Facilities Construction Account, the Restitution Fund, and the DNA Identification Fund. (In the nearby box, we provide an example of one fund—the DNA Identification Fund—that faces potential insolvency.) In addition, other funds could be in a similar situation in the future if collections of criminal fine and fee revenue continue to decline. Instead, the Legislature could focus on ensuring that programs provide legislatively desired service levels. However, because these programs would now be supported by the General Fund, decisions about General Fund expenditures would be more difficult as the Legislature would need to weigh funding for these programs against all other programs currently supported by the General Fund.

DNA Identification Fund Facing Solvency Concerns

The DNA Identification Fund, which primarily supports the Department of Justice (DOJ) Bureau of Forensic Services, has been structurally imbalanced since 2010‑11 and would likely be facing insolvency in the current year absent planned expenditure reductions. In 2015‑16, DOJ spent $70 million from the fund to support forensic activities. The 2016‑17 budget anticipated similar levels of expenditures. However, the administration currently estimates that the fund will only be able to support $62 million in expenditures in 2016‑17. The 2017‑18 budget estimates a further decline to $59 million in 2017‑18. This will require DOJ to immediately absorb at least $11 million in reductions in the current and budget year. Such a significant reduction will likely impact DOJ’s ability to process evidence in a timely manner, potentially resulting in significant backlogs.

Proposed Increase in Resources for FTB Court‑Ordered Debt Program

Governor’s Proposal

As discussed previously, collection programs can contract with the FTB’s Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Program. State law authorizes FTB to retain up to 15 percent of the collection revenue to cover administrative costs for operating the program, with such revenue being deposited in the Court Collection Account. The Governor’s budget for 2017‑18 proposes a $1.1 million augmentation from the Court Collection Account for the FTB’s Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Program. In prior years, FTB hired seven temporary positions to address an increase in workload. A portion of this funding would be used to support the conversion of these seven existing temporary positions to permanent positions to maintain the program’s existing service levels. (In 2015‑16, the program collected nearly $109 million and spent $11.4 million to support 40 positions.) The remainder of this funding would be provided on a three year, limited term basis to support 11 positions to eliminate a one‑time backlog that accumulated before the seven temporary positions were hired. FTB estimates that the requested limited‑term positions would generate an additional $20 million over three years.

LAO Assessment

Governor’s Proposal Merits Consideration . . . The Governor’s proposal for converting temporary positions to permanent positions merits consideration. These temporary staff were first hired to help FTB process workload from more courts and counties choosing to participate in the Court‑Ordered Debt Program. This additional workload still exists. Additionally, the department reports that the temporary nature of these positions has resulted in a high attrition rate. This is problematic because new staff require a significant amount of time to train before they become proficient at collecting. Accordingly, by making the positions permanent, the program would be able to maintain or increase collections. The proposal for limited‑term positions also merits consideration. Addressing the backlog would likely result in the collection of more revenue as well as help insure individuals comply with the court’s order to pay a specified amount as punishment for violating state law.

. . . However, Does Not Address Overall Weaknesses in the Existing Collection System. The Governor’s proposal focuses solely on improving FTB collection efforts. However, as discussed previously, FTB plays a small part in the overall debt collection process. As a result, the Governor’s proposal does not address more fundamental weaknesses in the existing collection system. We identified a number of such weaknesses in our November 2014 report, Restructuring the Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Process. Such weaknesses include:

- Lack of Clear Fiscal Incentives for Cost‑Effective Collections. Currently, there is little fiscal incentive for courts and counties to collect debt in a cost‑effective manner or to maximize the amount collected. For example, collection programs are allowed to recover their operational costs related to delinquent collections regardless of how high those costs are or how much debt is actually collected. This provides little incentive to operate efficiently. Additionally, programs have little incentive to collect debt before it has become delinquent, when it is cheaper to collect, because the programs are only permitted to recover their costs related to pursuing delinquent debt. It is much more difficult and expensive to collect the debt after it becomes delinquent.

- Difficult to Comprehensively Evaluate Performance of Collection Programs. It is difficult to comprehensively evaluate the performance of collection programs due to incomplete and inconsistent reporting of total collections and distributions. For example, collection programs are not required to report on collection activities of debt that has not become delinquent, resulting in a lack statewide information on such activities. This information is important because these activities can directly affect the cost and success of collecting delinquent debt. Thus, this information is needed to evaluate the overall success of collection programs. Additionally, there is a lack of performance measures to evaluate how cost‑effectively collection programs pursue debt.

- Lack of Data on Collectability of Outstanding Debt. Currently, there is a lack of data on the collectability of outstanding debt. Limited analysis has been conducted to determine what portion of the outstanding debt is collectable in a cost‑effective manner. Without such an analysis, it is unknown what portion of the total balance collection programs should actively pursue.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Governor’s Proposal. We recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to provide $1.1 million to support the conversion of 7 temporary positions to permanent positions and to support 11 three‑year, limited‑term positions for FTB’s Court‑Ordered Debt Program. The requested positions would help maintain, and potentially improve, the ability of the program to collect criminal fines and fees in a cost‑effective manner. It would also help ensure that court orders to pay fines and fees are adequately enforced.

Make Improvements to Overall Collection Process. We made a number of recommendations in our November 2014 report, Restructuring the Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Process, to comprehensively improve the existing collection process, including:

- Implementing New Incentive Structure for Collections. We recommend the Legislature implement a new incentive structure that provides collection programs with greater flexibility in how and when they collect debt and rewards them for collecting cost‑effectively or increasing the total amount collected. Specifically, each program would be able to retain their actual costs of collecting—up to the amount they received for collecting delinquent debt in a fixed base year. Once a program collects the same amount of total debt (both delinquent and debt that has not become delinquent), the program would be able to retain a set percentage of the amount of new revenue it collected for its own purposes. Because of the current lack of data on collections, we propose a three‑year pilot program to test the new incentive model prior to implementing it statewide.

- Requiring Improved Reporting on Collections. We recommend the Legislature make Judicial Council responsible for complete reporting on collections, including reporting on collections of debt before it becomes delinquent. We also recommend Judicial Council implement performance measures that allow for the accurate assessment of each collection program’s effectiveness. This would enable the comparison of the performance of collection programs across the state.

- Conducting a Collectability Analysis. We recommend Judicial Council work with collection programs to conduct an analysis to determine the collectability of outstanding fines and fees. This analysis could provide a more accurate understanding of how much of this outstanding balance could potentially be collected and at what cost.

Proposed Repeal of Driver’s License Holds and Suspensions for FTP

Governor’s Proposal

As discussed earlier, courts can place a hold on an individual’s driver’s license for FTA or FTP or notify DMV to suspend the license immediately for FTA or FTP. The Governor proposes budget trailer legislation to eliminate collection programs’ ability to use driver’s license holds and suspensions as a sanction for an individual’s FTP. Driver’s license holds and suspensions would still be available for FTA.

LAO Assessment

Repeal Could Provide Relief to Individuals Who Fail to Pay. Eliminating the ability of courts to use driver’s license holds and suspensions as a collection sanction would provide relief to individuals who fail to pay. For many individuals, driving is a basic necessity as it allows individuals to commute to work, pick up children from school, and conduct other daily business. Thus, many continue to drive even if they lack a valid driver’s license. This can result in additional fines and fees being assessed—significantly increasing the total amount owed by an individual. For example, individuals who cannot afford to pay their debt in full to lift a suspension could be subject to: a misdemeanor violation for driving on a suspended license, the impounding of their vehicle, and an increase in their insurance rate. This can make it very difficult for an individual with modest means to fully address their debt. Under the Governor’s proposal, individuals with FTP would no longer be subject to such additional penalties as their license would no longer be held or suspended.

Repeal Could Negatively Impact Collections. While the repeal would provide relief to individuals who fail to pay, it could negatively impact the ability of collection programs to collect fines and fees. This is of concern because this debt was levied by the courts as punishment for violating criminal offenses. Thus, collection programs effectively enforce court orders through their collection activities. The proposed repeal would likely make collection programs less effective as agencies would have one less tool at their disposal. While no data has been collected that would allow a precise estimate of the magnitude of the impact, collection entities report that they routinely interact with individuals seeking to make payments in order to have their driver’s license reinstated. Additionally, while a comprehensive statewide evaluation of the effectiveness of driver’s license holds and suspensions has not been conducted, the experiences of specific collection programs suggests that the repeal could potentially reduce total statewide collections by the tens of millions of dollars annually. For example, several trial courts that recently stopped using driver’s license holds each reported a decline in revenue in the millions of dollars.

Raises Larger Questions About Appropriate Sanctions for FTP. The Governor’s proposal implies that driver’s license holds and suspensions are inappropriate consequences or sanctions for failing to pay fines and fees. On the one hand, this may be true for certain individuals—such as those who are generally careful drivers who simply lack sufficient means to pay their debt or whose offense has no connection to driving. For these individuals, the suspension may be inappropriate as it is too severe of a consequence for a minor infraction or has no relation to whether or not they should be allowed to drive. However, this may not be true in all FTP cases. For example, holds and suspensions could be appropriate consequences for individuals who deliberately choose not to pay their debt even though they have sufficient means or for individuals who frequently violate traffic laws. Thus, the Governor’s proposal raises larger questions about what consequences are appropriate punishments for failing to pay fines and fees imposed by the state as punishment for violating law.

LAO Recommendations

Weigh Trade‑Offs of Potential Changes to Driver’s License Sanctions. In considering the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature will want to weigh the relative trade‑offs in repealing the driver’s license hold and suspension sanction for FTP. Such a repeal would provide relief to individuals who fail to pay as they would no longer face the consequences for driving on a suspended license (such as having their vehicle impounded). However, the repeal would also negatively impact the ability of collection programs to collect fines and fees, which in turn would increase the magnitude of structural shortfalls or insolvencies faced by various state funds receiving such revenue absent any changes in how criminal fine and fee revenue is distributed.

Consider Alternatives to Governor’s Proposal. The Legislature could consider alternatives to the Governor’s proposal. For example, the Legislature could consider modifying the Governor’s proposal to provide some relief to individuals who fail to pay, while still preserving driver’s license holds and suspensions as a collection sanction. Such a modification could take many forms. One option is to change state law to allow for FTP holds to be removed and applied at the court’s discretion similar to FTA holds. This would encourage collection programs to remove the hold before the individual pays the debt in full. Similar to FTA, the hold would then become a tool to encourage individuals to contact the court. Other options include permitting holds but not suspensions or increasing the number of holds that must be placed before a license can be suspended.

Direct Judicial Council to Conduct a Comprehensive Evaluation of Collection Best Practices and Sanctions. While state law and the Judicial Council specify a series of collection best practices and sanctions (which includes the use of driver’s license holds and suspensions), there has generally been a lack of evaluation to determine whether these best practices and sanctions are cost‑effective. In addition, collection programs have flexibility in deciding which best practices they choose to implement and how they implement any of the practices they adopt. Without an evaluation of these practices, it is difficult to determine whether the specific ways in which individual collection programs operate are cost‑effective. Finally, a number of collection programs have also identified and implemented additional local best practices and sanctions. Without an evaluation, it is difficult to determine whether these practices or sanctions are cost‑effective and should be implemented—or at least encouraged—statewide.

In view of the above, we recommend the Legislature direct Judicial Council to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of collection best practices and sanctions—including driver’s license holds and suspensions—currently used across the state, as well as those utilized by specific programs locally. The results of such an evaluation would help determine which currently employed best practices, methods of implementation, or sanctions are most cost‑effective, as well as under what circumstance such practices would be cost‑effective. Such information would help the Legislature as it considers future changes to collection best practices and sanctions.

Reevaluate Structure of Criminal Fine and Fee System. As discussed above, the Governor’s proposal raises larger questions about appropriate sanctions for failing to pay fines and fees. However, this issue is only one piece of the overall criminal fine and fee system. The state’s current system has evolved from statutes passed over the course of numerous years. In order to ensure that the system effectively meets current legislative goals and priorities, we recommend that the Legislature reevaluate the overall structure of the criminal fine and fee system. As part of this evaluation, we recommend the Legislature consider four key questions—including the question of appropriate sanctions—to guide any subsequent changes to the state’s fine and fee system. (Please see our January 2016 report, Improving California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System, for more detail on these questions.)

- What Should Be the Goals of the Criminal Fine and Fee System? A fine and fee system can serve various purposes, such as deterring behavior or mitigating the negative effects of crime. Some goals are not mutually exclusive, while others cannot be fully accomplished together. As such, the Legislature may need to determine which of its goals it values most when assessing the state’s fine and fee system. Ultimately, the Legislature should set fines and fees to reflect these goals.

- Should Ability to Pay Be Incorporated? To the extent the Legislature is interested in incorporating ability to pay into the criminal fine and fee system, there are various ways to do so. One way is to calculate fines and fees based on an individual’s ability to pay. Another option is to levy the same level of fines and fees on all offenders who commit the same violation, but implement alternative methods for addressing the debt (such as through community service).

- What Should Be the Consequences for Failing to Pay? The Legislature will want to consider what consequence individuals should face when they fail to pay their fines and fees. The Legislature could also take action to help prevent individuals from becoming delinquent—such as by authorizing programs to offer a discount if offenders pay their debt in full. The comprehensive evaluation on collection best practices and sanctions recommended above could be helpful in answering this question.

- Should Fines and Fees Be Adjusted? Once the Legislature sets the appropriate fine level for criminal offenses, the Legislature will want to decide whether and how such fines are adjusted in the future. For example, the levels could be regularly reevaluated or automatically adjusted (such as by using a statewide economic indicator).

APPENDIX

Summary of Fine and Fee Revenue Deposits in State and Local Fundsa

(In Millions)

|

2011‑12 |

2012‑13 |

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

|

|

State Administered Funds (Non‑Judicial Branch) |

|||||

|

State Penalty Fundb |

$138.4 |

$130.5 |

$124.4 |

$120.9 |

$105.7 |

|

General Fund |

75.0 |

69.1 |

73.0 |

65.5 |

60.3 |

|

DNA Identification Fund |

53.9 |

62.8 |

67.9 |

68.2 |

59.7 |

|

Motor Vehicle Account |

42.3 |

48.3 |

53.5 |

57.0 |

68.3 |

|

Restitution Fund |

56.4 |

54.9 |

52.7 |

56.8 |

38.6 |

|

EMAT Act Fund |

11.7 |

10.2 |

10.2 |

8.5 |

7.7 |

|

Fish and Game Preservation Fund |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

|

Other Funds |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

1.2 |

|

Totals |

$379.3 |

$377.4 |

$383.3 |

$378.9 |

$342.1 |

|

State Administered Funds (Judicial Branch) |

|||||

|

Trial Court Trust Fund |

$310.6 |

$302.2 |

$302.1 |

$302.6 |

$259.1 |

|

Immediate and Critical Needs Account |

241.5 |

224.4 |

217.5 |

207.6 |

177.5 |

|

State Court Facilities Construction Fund |

84.3 |

76.5 |

74.0 |

71.5 |

61.4 |

|

Trial Court Improvement and Modernization Fund |

61.8 |

58.3 |

48.2 |

41.1 |

38.7 |

|

Court Facilities Trust Fund |

1.7 |

5.7 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

|

Totals |

$700.1 |

$667.2 |

$644.1 |

$625.0 |

$538.6 |

|

Local Government Administered Funds (County) |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$431.7 |

$415.5 |

$415.9 |

$394.0 |

$367.2 |

|

Maddy EMS Fund |

85.0 |

81.0 |

86.1 |

84.2 |

72.1 |

|

Criminal Justice Facilities Fund |

71.7 |

65.3 |

52.1 |

49.5 |

43.8 |

|

Courthouse Construction Fund |

43.1 |

40.5 |

39.0 |

37.9 |

33.9 |

|

DNA Identification Fund |

28.9 |

28.0 |

27.5 |

26.5 |

22.6 |

|

Alcohol and Drug Related Special Funds (various) |

12.6 |

12.2 |

11.3 |

11.0 |

10.4 |

|

Automated Fingerprint Identification Fund and Digital Image Photographic Suspect Identification Fund |

9.3 |

8.3 |

8.1 |

7.7 |

6.4 |

|

Laboratory Special Funds (various) |

7.5 |

7.2 |

6.8 |

7.0 |

7.1 |

|

Other Funds |

10.2 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

10.1 |

10.2 |

|

Totals |

$700.0 |

$668.0 |

$656.8 |

$627.9 |

$573.6 |

|

Local Government Administered Funds (City) |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$178.1 |

$170.7 |

$165.4 |

$153.4 |

$133.1 |

|

Totals |

$178.1 |

$170.7 |

$165.4 |

$153.4 |

$133.1 |

|

Collection Programs |

|||||

|

Operating Costs |

$120.2 |

$114.5 |

$113.6 |

$116.2 |

$114.2 |

|

Totals |

$120.2 |

$114.5 |

$113.6 |

$116.2 |

$114.2 |

|

Total Amount Distributed |

$2,077.6 |

$1,997.8 |

$1,963.2 |

$1,901.4 |

$1,701.5 |

|

aDue to certain data limitations, these numbers reflect our best estimates of the amount of fine and fee revenue distributed to state and local funds. Actual amounts could be higher or lower. bState Penalty Fund revenues are allocated to nine other state funds (such as the Peace Officers’ Training Fund and the Restitution Fund) with each receiving a certain percentage specified in state law. EMAT = Emergency Medical Air Transportation and EMS = Emergency Medical Services. |

|||||