LAO Contact

March 14, 2017

Savings Plus Program

An Optional Retirement Benefit for State Employees

Executive Summary

In addition to retirement benefits that are at least partially paid by the state—including pension, retiree health, Social Security, and Medicare benefits—the Savings Plus Program (SPP) provides state employees a low‑cost investment vehicle to save money on their own for their retirement. This report reviews SPP and is organized into three broad sections.

Background on the SPP Program and Employee Participation. We find that although nearly three‑fifths of eligible state employees have an SPP account, only about one‑third of state employees regularly make contributions to their SPP account and that most regular contributions are low. In addition, we find that certain factors affect employees’ contributions—including age (younger employees are less likely to participate), income (higher‑paid employees are more likely to participate and to save a higher percentage of their pay), and economic conditions (employees reduced their contributions during recent difficult economic periods). As a result of low participation and low regular contributions, the typical account balance is low, with most account balances being lower than $50,000.

Role That State Retirement Benefits—Including SPP—Play in Retirement Security. Although everyone can benefit from saving money for their retirement during their career, we conclude that long‑term state employees likely could retire without relying heavily on savings because of the financial security provided by state‑funded benefits. However, we identify three groups of employees who could benefit most from putting aside money: shorter‑term employees, who work less than a full career with the state; lower‑paid employees, who might need money in addition to their pension to cover essential costs in retirement; and future employees, who will earn less generous retiree health and pension benefits. In addition, we discuss the benefit of investing over long periods of time to use the power of compounding interest—something younger employees can benefit from most.

Comments About SPP and Options for the Legislature to Consider. We think that SPP is an important benefit the state offers employees as part of its employee compensation package. That being said, many employees who would benefit from using the program are not participating or are not contributing a meaningful amount of money to their accounts. When reviewing ways to improve participation, we recommend that the Legislature review policies other employers have adopted to improve participation in their retirement savings plans—including auto‑enrollment, auto‑escalation, and employer matches. We recommend that the Legislature take its time to consider its options and understand the possible effects of making changes to the current benefit.

Introduction

This report examines the state’s optional deferred compensation program available to state employees—known as the Savings Plus Program (SPP). The report is organized into three broad sections. First, we provide background on SPP—including the program design and options available to employees—and present our findings related to employee participation in the program. Second, we discuss the role that state retirement benefits—including SPP—play in providing retirement security to retired state employees. Third, we provide overall comments on the program and discuss legislative options to improve participation in the program. Throughout the report, we discuss a variety of topics intended to help the reader understand the program’s role in state employee compensation and retirement planning.

Savings Plus Program

Optional Employee‑Funded Retirement Savings Benefit. Most state employees earn retirement benefits that are at least partially funded by the state, including a pension, retiree healthcare benefits, Social Security, and Medicare. In addition, an optional deferred compensation program—known today as the Savings Plus Plan—has existed since 1974 in order to encourage retirement savings and increase savings options available to state employees. The program is managed by the California Department of Human Resources and allows most state employees—about 250,000 employees, generally all state employees except those who work for the University of California—to set aside money they earn during their state career to save for retirement. The SPP is a self‑funded program supported by administrative fees and operating expenses charged to participants’ accounts. The state currently does not contribute money to employees’ SPP accounts—either in the form of a match or otherwise. Employees who choose to participate in the program determine (1) how much money to save, (2) how to invest the money they have saved, and (3) how to use these funds in retirement.

In addition to the optional deferred compensation program available to most state employees, SPP also administers two deferred compensation programs designed for specific types of employees—the Alternate Retirement Program (ARP) and the Part‑Time, Seasonal, and Temporary (PST) Employees Retirement Program. The ARP is a program that provided new employees who were hired between August 2004 and June 2013 up to two years of retirement savings in lieu of traditional pension benefits. Employees who are not covered by Social Security and are excluded from earning state pension benefits are enrolled automatically in the PST retirement savings plan—SPP reports there are more than 14,000 active participants in PST. The ARP and PST are not included in this report’s analysis of SPP.

Four Account Types Available to Participating Employees. The types of retirement savings plans available to state employees through SPP include 401(k) and 457(b) retirement savings plans. The names of these plans refer to the section of federal tax law that authorizes each plan. The law treats these plans differently in some respects, including the amount of money employees may contribute later in life above the normal contribution limits established under federal law (referred to as “catch up” contributions) and the circumstances under which a participant may withdraw money before retirement. Beginning in 2013, state employees have two account options within each plan—“traditional” or “Roth”—that affect when they pay taxes on the money that is invested in either their 401(k) or 457(b) plans.

Variety of Investment Options. People choose how to invest their retirement savings based on personal investment goals, the amount of time before they expect to draw down savings, how involved they want to be in managing their investments, the level of risk that they want to take, and their willingness to pay fees. The investment funds SPP offers range from conservative (with virtually no risk that investors lose money on their investment) to aggressive (with much higher probability of losing money in any given year). A fund with higher risk is expected to achieve higher returns on the investment over time (conversely, investments in lower‑risk funds are expected to have lower average returns). A common retirement saving strategy directs investors to adjust their investments over time so that they expose their assets to lower levels of risk as they approach retirement. Participants can choose to have their asset allocation professionally managed or to make these decisions themselves by investing their money in any mix of the funds offered by SPP, including:

- Managed Funds. Managed funds are “actively managed funds,” meaning fund managers make informed decisions to trade with the goal of earning higher investment returns than the market average.

- Index Funds. Index funds are “passively managed.” Fund managers make trade decisions with the intent of matching the average performance of a group of stocks. Index funds typically have less overhead than actively managed funds, resulting in lower operating expenses and fees.

- Target Date Funds. With the two types of fund options discussed above, participants must implement and monitor their investment strategy over time. Participants who want to “set and forget” their investment strategy can choose to invest their money in a target date fund. Target date funds offered by SPP are constructed using the core investment funds discussed above. Participants select a target date fund based on the year in which they expect to begin drawing money from the account. Over time, fund managers change the mix of these funds so that investments in the target date fund are exposed to lower levels of risk as the target date approaches.

Optional Self‑Directed Brokerage Account. Although participants have choices among the three types of funds described above, they do not have discretion as to what investment decisions are made within each fund. Participants who want a more direct role in selecting specific stocks or mutual funds included in their investment portfolio may choose to manage their savings in SPP through a self‑directed brokerage account—currently provided by Charles Schwab.

Annuity Products Not Available. Despite the fact that current law requires SPP to offer an annuity product, SPP has not included this type of product among its investment options for more than three years. In a nearby box, we discuss the challenges SPP has identified in offering annuity products and why the Legislature should consider removing the requirement in current law.

Annuity Products and Savings Plus Program (SPP)

Current Law Requires SPP Provide Annuity Product. An annuity is an insurance product that commonly is used to provide an income stream in retirement. While there are different types of annuities, the basic structure of an annuity is that a person invests money with an insurance provider in exchange for regular payments from the provider in the future. State law—Section 19993.05 of the Government Code and Section 599.942 of the California Code of Regulations—requires SPP to offer an annuity product among its menu of investment options available to participants.

Should Legislature Consider Removing Requirement? SPP has found it challenging to offer an annuity product among its investment options. For more than three years now, no vendor has submitted bids to SPP’s Request For Proposal for an annuity product. As a result, SPP currently does not offer an annuity product as an investment option to participants. SPP staff have identified two fundamental challenges with offering this type of product among the program’s investment options:

- Incongruous Contract Periods. Annuity products provide participants income streams over long periods of time, requiring them to have relationships with the same annuity provider over many years. This arrangement is awkward for SPP as it contracts with providers typically for periods of only five or seven years. When a contract expires, SPP is required to seek competitive bids from the vendor community—the most competitive bid might not be from the old provider.

- Fiduciary Role to Minimize Costs. SPP serves a fiduciary role over the money participants invest in the program. SPP interprets this role to mean that it must provide participants investment options that will help participants reach their investment goals at the lowest possible cost. Compared with investment options with similar returns, annuity products tend to have relatively high fees and other costs.

Given the challenges SPP has identified in offering an annuity product, we think it is reasonable for the Legislature to hear from SPP and annuity providers to determine whether or not state law should continue to require SPP to offer an annuity product. Regardless of whether or not SPP provides an annuity option, participants can—upon separating from state service—use their assets in SPP to purchase an annuity in the private market.

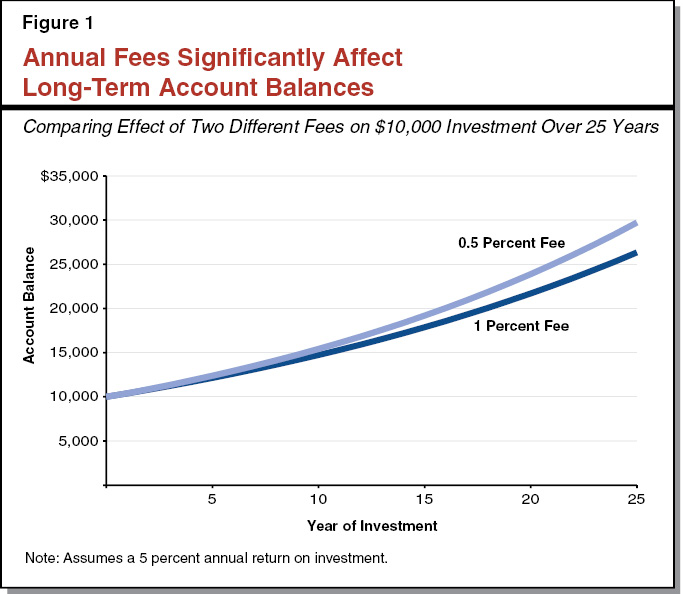

Low Administrative and Investment Fees. Participants pay two types of ongoing fees to invest their money with SPP: (1) administrative fees and (2) operating expenses of investment funds. The SPP monthly charges a flat dollar administrative fee of $1.50 to participants of each plan in order to pay for staff and other operating expenses of the state program. Investment fund operating expenses are charged by the investment manager as a percent of the fund’s balance, reducing any gains from the fund. The operating expenses vary by the type of investment chosen by the participant and range from 0.13 percent and 0.77 percent (0.05 percent of these expenses go towards SPP administration costs). It is difficult to compare fees charged by retirement savings plans offered by different employers; however, it appears that SPP fees are low compared with national averages.

Fees can have a significant effect on the growth of funds over a period of time. To illustrate how different expense ratios can affect a person’s savings, Figure 1 illustrates the effect of $10,000 invested to earn an average return of 5 percent each year over 25 years with (1) an annual operating expense of 1 percent compared with (2) an annual operating expense of 0.5 percent. At the end of the 25‑year period, the perhaps seemingly small difference of 0.5 percent in operating expenses results in the account with higher fees being more than 10 percent ($3,000) less than the account with lower fees.

Accessing Money Before Retirement. Before retiring, eligible participants can access the funds they have invested with SPP through either a withdrawal or a loan. Money that is withdrawn—permanently taken out of their account—before retirement may be subject to income and penalty taxes. In the case of a loan, participants borrow money from their account and pay the money back—with interest—over time. (We discuss loans in greater detail later in this report.) While accessing this money before retirement can help participants address immediate cash needs, it also can significantly reduce their account’s growth potential and, ultimately, the amount of money available to them in retirement.

Employee Participation

Nearly Three‑Fifths of Employees Have SPP Account, but Few Make Regular Contributions. Of the nearly 250,000 employees eligible to participate in SPP, the program reports that—as of May 2016—about 144,000 employees have an account with SPP. This means that fewer than 60 percent of eligible state employees are saving for retirement using SPP. This level of participation is lower than the national average of 70 percent of people eligible to participate in a 401(k) through their employer. There are a number of reasons why participation might be lower among state employees. For example, employees might (1) not see a need to save because of the state‑funded retirement benefits provided in the state’s compensation package, (2) find it financially difficult to participate because of other competing priorities in their personal budgets, (3) choose to invest retirement savings in another type of account, or (4) not be aware of SPP. In 2014‑15, 93,600 employees made contributions to their SPP accounts—about two‑thirds of employees with an SPP account. This low level of regular participation in the program seems relatively consistent over the past 15 years. (Participation among California State University employees appears to be particularly low, with only about 10 percent regularly participating in SPP.)

Some Types of Employees More Likely to Participate. Some employees are more likely to use an SPP account than others. These employees include:

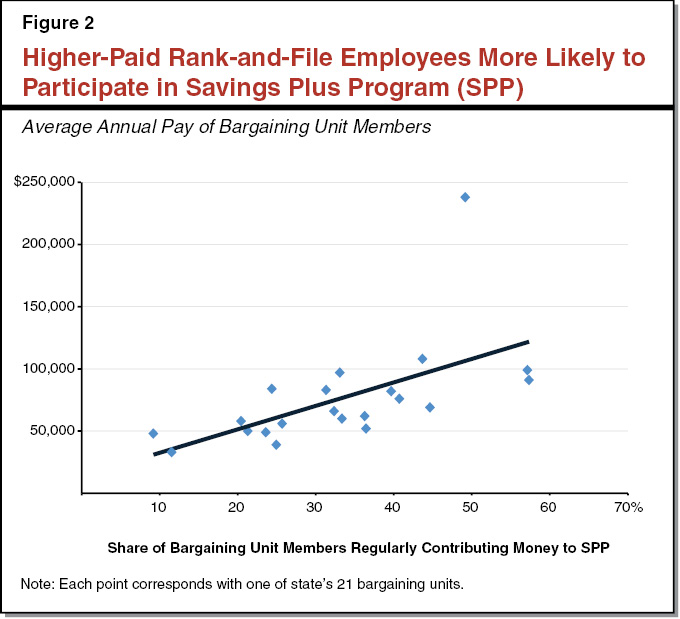

- Higher‑Paid Employees. There is significant variation in participation across the state’s 21 bargaining units. Historically—as shown in Figure 2—bargaining units that are paid more have had higher participation rates. Higher‑paid managers and supervisors also are more likely to make regular contributions.

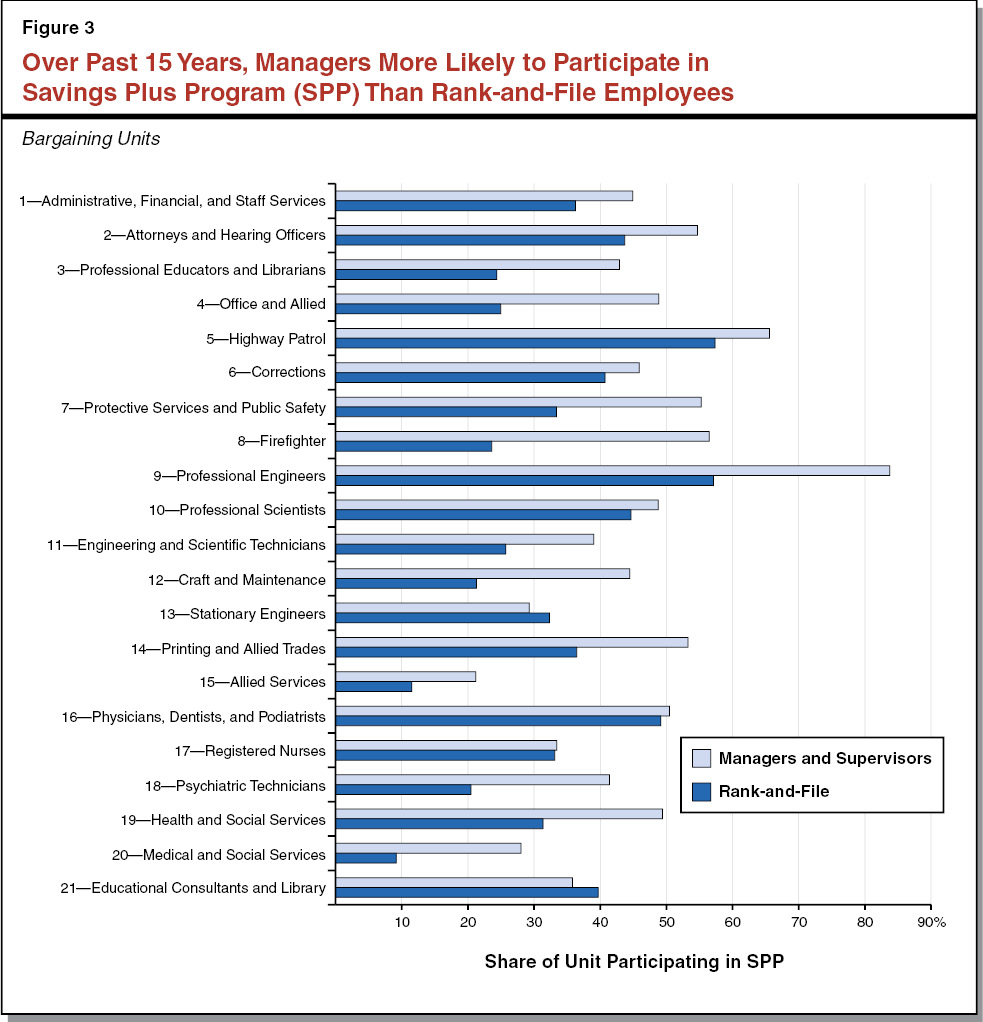

- Managers and Supervisors. About half of managers and supervisors make regular contributions to SPP accounts. As Figure 3 shows, managerial or supervisorial professional engineers, physicians, highway patrol officers, attorneys, correctional officers, and professional scientists all have participation rates exceeding 50 percent. Managers and supervisors typically are long‑term state employees who have worked with the state for more than 15 years.

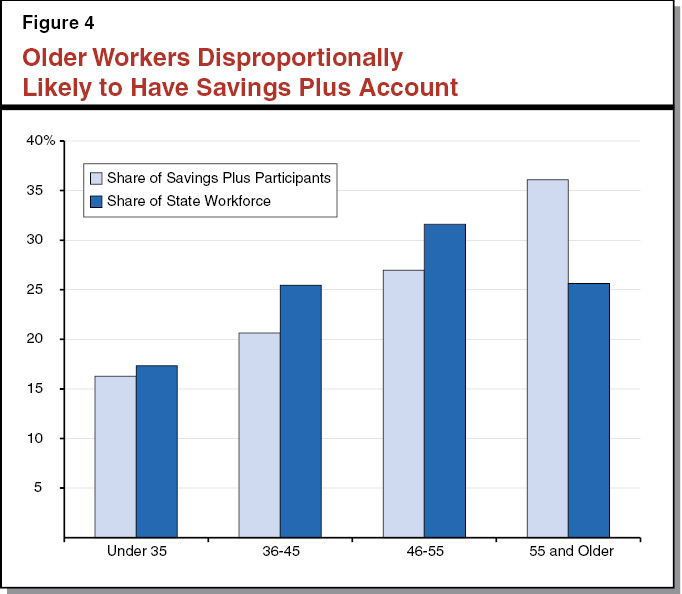

- Older Employees. A disproportionate share of older employees participate in SPP. As Figure 4 shows, employees who are older than 55 years represent about one‑quarter of state employees but represent more than 35 percent of SPP participants.

Relatively Few Employees Have Both 401(k) and 457(b) Plans. Depending on a person’s financial goals, it can make sense to invest money in both plans offered by the state under SPP. The largest benefit of investing in both plans is that it allows participants to contribute up to the maximum amount of money authorized for each plan. (A person can contribute to both plans without contributing the maximum amount to either plan.) About 20 percent of the participants making regular contributions to SPP in 2014‑15—more than 18,350 participants—regularly contributed money to accounts in both plans. Bargaining units with higher‑paid members tend to have a higher share of employees who contribute money to both accounts.

Employee Contributions

Contributions Limited by Minimum and Maximum Requirements. Participating employees choose whether they want to regularly contribute money to their SPP accounts and how much money they contribute. However, these contributions are limited by state and federal policy. Specifically, (1) SPP requires a minimum regular contribution of $50 per month and (2) federal tax law establishes the maximum amount of money that participants may contribute each year towards their 401(k) and 457(b) plans. In most cases, the limit for each plan in 2017 is $18,000.

Regular Contributions Are Low. Some employees contribute significant amounts of money to their SPP accounts. (For example, in 2011, more than 300 state employees contributed more than $30,000 to their SPP accounts.) However, many of these large contributions are not regular contributions, but rather are one‑time contributions made at the end of a person’s career (discussed in greater detail below). Regular ongoing contributions to SPP appear to be low. In particular, in 2011, (1) more than one‑half of participants contributed less than $2,000 in the year and (2) nearly 30 percent of participants contributed less than $1,000 in the year. Considering the minimum regular contribution requires participants to contribute at least $600 each year, it seems that many participants contribute about the minimum amount.

Leave Cash Outs Result in Large One‑Time Contributions Upon Retirement. Employees who are retiring often have significant balances of unused leave. Employees can receive payment for certain types of unused leave when they separate from state service as (1) income subject to income taxes or (2) a pre‑ or post‑tax deposit to SPP. Many employees choose to deposit a large portion of this payment into their SPP account. As a result, there are large spikes in contributions to SPP in years when more people retire with large leave balances. (Within a given year, there often are spikes in contributions in months with high rates of retirement.)

Higher‑Paid Employees Regularly Contribute Larger Share of Pay. Not only are higher‑paid employees more likely to participate in SPP, but those who participate in the program regularly tend to contribute a higher percentage of their pay than participating lower‑paid employees.

Older Employees Contribute Larger Share of Pay. The percentage of pay that participating employees contribute to SPP depends greatly on their age. Participating employees who are the farthest away from retiring contribute the smallest portion of their pay to SPP while employees closest to retirement contribute the largest portion of their pay. The larger contributions from older employees likely are due to a combination of large one‑time leave cash outs upon retirement and catch‑up contributions.

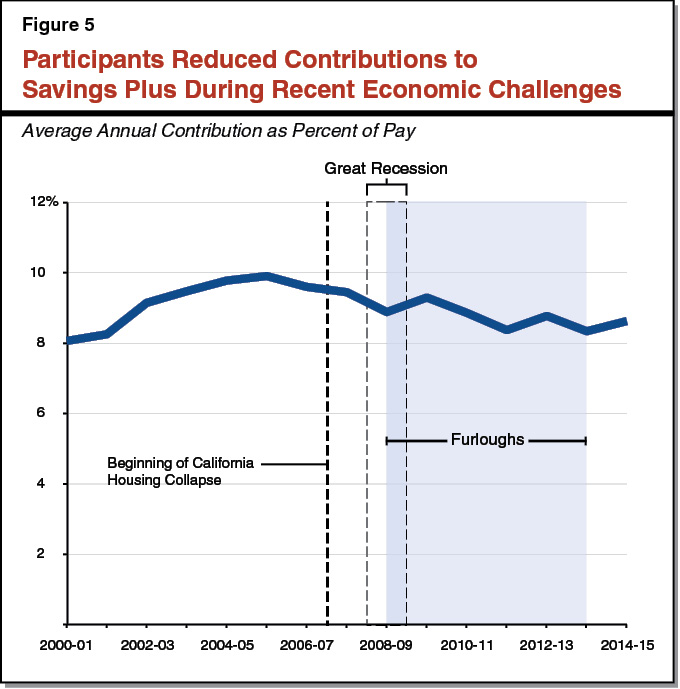

Employees Reduced Contributions During Periods of Economic Stress. Parts of the past 15 years have been difficult economic times. Many Californians—including state employees—were faced with personal financial challenges as a result of the end of the housing bubble in the mid‑2000s and the recession that followed. In particular, state employees saw significant cuts in their pay—between about 5 percent and 14 percent—during up to 49 months of furloughs between 2009 and 2013 (see our March 2013 report, After Furloughs: State Workers’ Leave Balances, for more information on the furlough program). Employees participating in SPP seem to have reduced how much money they contributed to their SPP accounts in response to these economic challenges. As Figure 5 shows, the average contribution to SPP—as a percent of pay—over the past 15 years peaked in 2005‑06 at nearly 10 percent of pay and declined during years of furloughs. The figure includes money participants contributed after cashing out leave upon retirement and captures a period of time of increased retirements after 2009‑10. As a result, participating state employees likely reduced their regular contributions during furloughs by more than what is reflected in the figure.

Account Balances

Low Account Balances. We would expect state employees to need less savings than employees in the private sector. That being said, account balances in SPP are much lower than national averages. According to January 26, 2016 testimony to a U.S. Senate committee by the Center for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College, the median 401(k) balance for employees aged between 55 years and 64 years who earn between $61,000 and $90,999—the pay range in which the average state employee falls—was about $100,000 in 2013. Although some SPP participants have large account balances—1,300 participants have account balances exceeding $500,000—the vast majority of participants have very low account balances. More than 70 percent of SPP participants have account balances of less than $50,000. The median 401(k) account balance of SPP participants between the ages of 56 years and 65 years is $25,000—one‑quarter of the amount reported nationally. (The median 457[b] account balance for this same cohort of participants is slightly higher at $28,000.)

Loans

As mentioned earlier, participants can borrow money from their retirement savings in SPP. Specifically, participants can have up to two open loans from each plan—401(k) and 457(b)—at any one time. The minimum amount of money that participants can borrow for each loan is $2,500 and the maximum amount is $50,000. There are two types of loans available to participants: (1) general purpose loans that can be used for any purpose and (2) primary residence loans that can be used to help employees purchase a primary residence. For each type of loan, the interest charged to the principal—as of September 2016—is 4.5 percent. (Under current policy, the interest rate is determined as 1 percentage point higher than the prime interest rate reported by The Wall Street Journal in the quarter during which the loan is initiated.) Participants who take out a loan must repay the loan back to their own accounts within (1) five years in the case of a general purpose loan and (2) 15 years in the case of a primary residence loan.

Policy Change and Furloughs Increased Borrowing From Retirement Savings. In order to initiate a loan, SPP requires participants to have a minimum account balance of $5,000. This threshold was established in June 2009 when SPP reduced the minimum account balance from $10,000. This policy change was intended to make it easier for state employees to access cash during the state’s furlough program. When comparing data from the years between 2006 and 2009 (the period immediately before furloughs and before the lower threshold was established) with the years between 2010 and 2015 (the period during and immediately after furloughs), the number of general purpose loans doubled. However, the value of the average general purpose loan decreased from about $12,900 to about $10,400. This suggests that more state employees took smaller loans against their retirement savings in order to deal with personal financial difficulties arising from the pay cuts during furloughs.

State Employee Retirement Security

A person’s financial security depends largely on their income and the costs they incur to maintain a certain standard of living. It is difficult to generalize how much money a person needs at any stage in life because a person’s financial security depends on a number of personal choices, circumstances, and assumptions regarding the future. This is particularly true regarding a person’s retirement security. That is, how do you determine whether a person will have enough money in the future to pay all expenses incurred from the date he or she exits the workforce until he or she dies? In this section, we discuss the retirement security provided by state‑funded retirement income and healthcare benefits and how the level of security provided by these benefits will change for retired future employees.

Retirement Income

Measuring Retirement Security. One common metric among financial planners and economists for assessing a person’s retirement security is known as the income replacement ratio. This ratio attempts to determine how much annual income a person needs to sustain a certain standard of living in retirement. This ratio is a person’s expected retirement income expressed as a percentage of the income the person earned before retirement. If a person’s replacement ratio exceeds a given target, he or she is more likely to have enough income to maintain his or her preretirement standard of living. There is no one‑size‑fits‑all replacement ratio. A 2005 CRR publication found: “Overall, the range of studies that have examined [the] issue consistently finds that middle class people need between 65 percent and 75 percent of their preretirement earnings to maintain their lifestyle when they stop working.” Similar to the 2005 study, a 2010 U.S. Census Bureau paper found that the replacement ratio for the median individual—as of 2004—was between 66 percent and 75 percent of preretirement income. In general, lower‑income workers may need a higher replacement ratio because they are expected to spend a higher proportion of their income on housing, transportation, food, healthcare, clothing, and other essentials.

A “Three‑Legged Stool.” During the 20th Century, retirement security in the United States evolved into what is referred to as the three‑legged stool of retirement security whereby a typical retired worker is expected to receive income in retirement from a combination of three sources: Social Security, employer‑sponsored retirement plans, and personal financial assets. The retirement benefits offered to state employees largely are based on the structure of the three‑legged stool of retirement security. Specifically, most state employees participate in Social Security, receive a pension from the state, and have the option to deduct money from their pay to save money on their own for retirement in SPP. As we discuss below, the level of retirement security these benefits provide retired state employees depends a great deal on how long the employee worked for the state, when the employee was hired by the state, and the level of pay the employee earned during his or her career with the state. Our discussion below looks only at the level of retirement security provided by state‑funded benefits. We cannot generalize state employees’ overall retirement security as we do not know employees’ or retirees’ alternate sources of income or personal assets held outside of SPP.

Social Security. Most state employees participate in Social Security. The largest groups of state employees who are excluded from Social Security are peace officers (like correctional officers) and firefighters. During the career of employees in Social Security, both the employer and employee pay taxes on earnings. In 2017, both the employee and the state pay 6.2 percent of the employee’s pay. Payroll taxes are not applied to earnings above a wage limit—$127,200 in 2017. When a worker retires, he or she receives monthly Social Security benefit payments based on how old they are when they begin receiving Social Security benefits and how much money they earned during their career (up to the wage limit mentioned above). California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) estimates that Social Security replaces between 15 percent and 30 percent of a typical eligible retired state employee’s final salary. Any changes in federal policy that affects Social Security could affect state and state employee costs to fund the benefit and could reduce the retirement security provided by the benefit.

Defined Benefit Pension. The vast majority of full‑time state employees earn a defined benefit pension as part of their compensation. When an employee retires, he or she receives a lifetime pension that is determined using a mathematical formula that takes into account the number of years of service credited to the employee multiplied by a rate of accrual (determined by the employee’s job, date of hire, and age at the time of retirement) and multiplied by the employee’s final salary level. Retirees typically receive a cost‑of‑living adjustment of up to 2 percent each year to at least partially offset erosions in purchasing power resulting from inflation in the broader economy. In the event that inflation exceeds 2 percent, the state guarantees that a retiree’s pension will maintain at least 75 percent of its original purchasing power.

The state’s pension benefits are funded through three main sources of funding: investment returns, state contributions, and employee contributions. CalPERS reports that about two‑thirds of every dollar paid to its retirees is paid from investment returns. Revenues from investment returns vary significantly year‑to‑year depending on market performance. CalPERS makes assumptions about investment returns when determining how much money must be contributed each year to fund the system. The state’s contributions towards these benefits are greatly affected by the extent to which investment returns vary from these actuarial assumptions. CalPERS staff expect investment returns over the next ten years to be lower than past average returns and lower than current assumptions. At its December 2016 meeting, the CalPERS board voted to reduce its assumed rate of return over the next few years to reflect these lower expected returns. This assumption change will increase the amount of money that must be contributed to the system each year. This will result in the state paying more to fund pension benefits for all employees. In addition, employees will need to contribute a larger percentage of pay in order to maintain the standard established under the Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act of 2013 (PEPRA) that employees pay one‑half of “normal costs” of pension benefits. To the extent that the state shifts higher pension costs onto state employees, employees likely will save less money in SPP.

Certain Factors Affect Employee Retirement Security Provided by Pension. A number of factors affect how much of final salary is replaced by the state’s defined benefit pension to retired state employees. Specifically, this replacement ratio depends on employees’:

- Type of State Job. Peace officers and firefighters who do not participate in Social Security receive pensions that are designed to replace a larger share of their salary at younger ages than other state employees.

- Date of Hire. Periodically, the state has modified the pension benefits received by future state employees. Most recently, employees hired after January 1, 2013—when PEPRA went into effect—are subject to a somewhat less generous benefit than employees hired before that date.

- Length of Service. Pension benefits are designed so that employees receive a specified percentage of their final salary for each year of service. Accordingly, the pension benefit increases with every year of service.

- Age at Retirement. The percentage of final salary received by state employees for each year of service depends on an employee’s age at retirement. Generally, employees receive a larger pension if they retire later in life.

State employees who were hired after 2013—“PEPRA employees”—will need to work longer to receive a pension that replaces the same portion of their working salary compared with employees earning pension benefits established before the state reduced pension benefits—often referred to as “classic employees.” In addition, high earning employees subject to PEPRA receive no benefit for earnings above a certain threshold, meaning that the state pension benefit replaces a somewhat smaller portion of these employees’ salary.

Substantial Share of Salary Replaced for Long‑Term Employees. In total, pension and Social Security benefits (after eligible retired state employees choose to begin receiving Social Security payments) replace between 70 percent and 90 percent of a typical long‑tenured state employee’s salary in retirement. Assuming they work a few extra years, this level of financial security also is available to long‑serving PEPRA employees.

Healthcare

Healthcare costs are largely nondiscretionary. For most retired Americans, healthcare is one of the highest costs incurred in retirement—especially as the retiree ages. For the past two decades, health premiums across the country have consistently increased at rates faster than inflation in the broader economy. Health premiums are expected to continue growing faster than the economy for the foreseeable future. To the extent that healthcare costs consume a growing share of a retired person’s income, his or her financial security can be significantly weakened.

Low Retiree Healthcare Costs for Long‑Term Employees. Employees with long careers with the state receive substantial state contributions to pay for their health premium costs. We describe this benefit for current employees and its interaction with Medicare in the box below. The state’s retiree health benefit largely has shielded retired state employees from rising premium costs by paying most—if not all—retiree health premium costs. With the state paying a substantial portion of healthcare costs for state employees who retire after working a long career with the state, retired state employees can use larger portions of their retirement income on other costs.

Interaction of Medicare and CalPERS Health Benefits for Current Retirees

Four Parts to Medicare. Medicare is the federal program that provides health care coverage to people over the age of 65 years. The program is funded by a combination of payroll taxes levied on active employees and their employers, premiums paid by people enrolled in Medicare, and money from the federal budget. The four parts of Medicare are discussed below. People participating in Medicare must be enrolled in Part A and Part B—referred to as “Original Medicare”—but can choose whether or not they want to participate in Part C or Part D.

- Part A (Hospital Insurance). People who paid Medicare payroll taxes for at least ten years do not pay a monthly premium for this coverage in retirement.

- Part B (Medical Insurance). To receive this benefit, people pay a monthly premium that is determined based on their income. The standard premium in 2017 paid by an individual making less than $85,000 each year is $134 each month ($1,608 for the year).

- Part C (Medicare Advantage Plans). Federal law allows people to purchase health insurance offered by a private company that contracts with Medicare to provide benefits covered by Part A and Part B. People enrolled in a Medicare Advantage Plan pay the monthly Part B premium in addition to whatever premium is established for the Medicare Advantage Plan.

- Part D (Outpatient Prescription Drug Insurance). People in either Original Medicare or a Medicare Advantage Plan can choose to pay an additional monthly premium to purchase Medicare‑approved prescription drug insurance under Part D.

State Contributions for Most Retired State Employees Cover Medicare Costs. Retired state employees receive money from the state to pay for health care costs. The amount of money the state pays is based on a weighted average of the premiums for the four health plans with the highest enrollment of state employees. Since 1978, the maximum contribution available to retired state employees has been what is referred to as the “100/90” formula, whereby the state pays an amount up to 100 percent of the average premium cost for the retiree and 90 percent of the average additional costs for his or her dependents. Retired state employees generally are eligible to receive this full contribution after 20 years of state service. (Retired employees with ten years of state service receive 50 percent of this amount, increasing 5 percent annually until the 100 percent level is earned.) Most state retirees are eligible to receive the full 100/90 contribution from the state.

Before being eligible for Medicare, retired state employees are enrolled in the same health plans available to active state employees. Once eligible for Medicare, retired state employees enroll in a Medicare Advantage Plan (Medicare Part C) administered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). The CalPERS Medicare plans include the coverage and costs for prescription drug coverage under Medicare Part D. Because Medicare is supported by money employees pay through payroll taxes and federal funding, the remaining premium costs for these CalPERS Medicare plans are much lower than the premiums for the health plans available to active state employees. In 2017, the premiums for these CalPERS Medicare plans range from $325 to $464 per month for single coverage—much lower than the state’s maximum 100/90 contribution to retirees of $707. State law allows the remainder of the available 100/90 contribution to reimburse retirees for their costs to pay premiums for Medicare Part B. In most cases, the state’s contribution fully offsets the retiree’s costs towards premiums.

Benefit Changing for Future Employees. As part of his 2015‑16 budget proposal, the Governor proposed significant changes to the state’s health benefits provided to retired state employees and how the state pays for these benefits. This policy is being implemented for most of the state workforce through either collective bargaining or state law. We describe the major elements of this policy in the box below. For a more detailed discussion of the plan, please refer to our March 2015 report, The 2015‑16 Budget: Health Benefits for Retired State Employees, or our analyses of recently proposed labor agreements.

Major Changes to Retiree Health Benefit

The state is implementing the Governor’s plan to reduce the state’s costs to provide health benefits to retired state employees. We summarize the major provisions of the changes being implemented below.

Significantly Lower Maximum State Contribution for Future Employees. Unlike the benefit received by current retirees, retired future employees will receive a significantly smaller amount of money from the state to pay for health premiums. Specifically, (1) the maximum benefit available to employees not eligible for Medicare will be up to 80 percent of the weighted average premium cost of CalPERS health plans available to active employees and (2) the maximum benefit available to employees eligible for Medicare will be up to 80 percent of the weighted average premium cost of CalPERS Medicare plans and retirees will be responsible for paying the full Medicare Part B premium.

Benefit Prefunded With Equal State and Employee Contributions. The state and employees each contribute the same percent of pay to prefund the state retiree health care benefit. These contributions will be deposited into a trust fund that is invested. At some point in the future, the benefit will be paid with a combination of money from the state, the employee (paid during the course of his or her career), and investment gains.

No Benefit for Future Employees Who Work Fewer Than 15 years. Future state employees must work with the state for 15 years to receive 50 percent of the maximum contribution. Retired state employees with fewer than 15 years of service will receive no benefit. In order to receive 100 percent of the maximum contribution, future employees must work with the state for 25 years.

Current and Future Employees Pay Same Contribution as Percent of Pay. The retiree health benefits earned by future employees provide significantly less money towards their health care in retirement compared with the benefit earned by current employees. Labor agreements implementing the Governor’s plan require all employees in a bargaining unit to contribute the same percentage of pay—between 2 percent and more than 4 percent of pay—regardless of (1) what benefit they are eligible to receive in retirement or (2) their pay level relative to other employees in the bargaining unit.

No Refund of Employee Contributions. An employee who separates from state service with fewer than 15 years of service will receive no retiree health benefit. In addition, these employees have no rights to the money they contributed to the retiree health trust fund over the course of their state career—potentially tens of thousands of dollars—or any of the earnings gained on these contributions.

Higher Health Costs for Future Employees When They Retire. Future retired state employees will experience significantly higher health costs than current state retirees by paying a larger portion of CalPERS Medicare plan premiums and the full Medicare Part B premium. Future retired state employees’ health costs likely will rise faster than the cost‑of‑living adjustment provided for their pension. Because pension and Social Security benefits are based on the salary employees earned during their career, these increased costs will disproportionately affect lower‑paid state employees in retirement. Future employees who work fewer than 15 years with the state will receive no money from the state to pay for these costs.

Employee Contributions to Prefund Benefit Discourage Savings . . . The standard established by the state’s current plan to prefund retiree health benefits is that the state and employees each will agree to pay one‑half of normal costs to prefund the benefit. In the agreements ratified by the Legislature to date, these contributions are established as a percentage of pay. The state and employee contributions to prefund the benefit likely will need to be revisited in future rounds of collective bargaining. To the extent that employees are required to pay larger shares of their pay to prefund retiree health benefits in the future, employees probably will save less for their retirement.

. . . Especially for Some Lower‑Paid Employees. Unlike pension benefits, the state’s retiree health benefit is not based on a person’s income either during his or her career or in retirement. The state’s retiree health benefit is the same for an employee earning $30,000 as it is for an employee earning $100,000. The agreements with the nine bargaining units represented by Service Employees International Union Local 1000 share the total cost to prefund retiree health benefits across the units so that all affected employees pay the same percentage of pay. For other units, labor agreements implementing the state’s shared cost prefunding standard require employees in lower‑paid bargaining units to pay a higher percentage of pay than employees in higher‑paid bargaining units. For example, the agreement with Bargaining Unit 2 (Attorneys)—a unit with an average base pay of more than $100,000—requires employees to pay 2 percent of pay each year to prefund the benefit, whereas the agreement with Bargaining Unit 12 (Craft and Maintenance)—a unit with an average base pay of less than $50,000—requires employees to pay 4.6 percent of their pay to prefund the same benefit. As a result, lower‑paid employees are less likely to save for retirement on their own under the state’s retiree health prefunding policy.

. . . And Shorter‑Term Employees. Under the state’s plan, new employees are eligible to receive retiree health benefits from the state only if they have worked with the state for at least 15 years. However, the plan requires all employees to contribute money to prefund the benefit. Under no circumstance would an employee who leaves state service before reaching the 15‑year mark—or his or her beneficiary—be eligible to receive a refund of the contributions he or she has made to prefund the benefit. In the case of the Unit 12 agreement, a future employee who separates with 14 years of service will receive no benefit in retirement even though the employee will have contributed nearly 5 percent of his or her pay to a state trust fund each year. Under the plan, the employee’s contributions over the course of the 14 years—on average totaling more than $30,000 for a Unit 12 employee—will do nothing to improve the employee’s retirement security but will reduce the cost to prefund retiree health benefits earned by other employees who work longer than 15 years. If, instead of prefunding coworkers’ retiree health benefits, the future shorter‑term employee had been able to deposit these contributions into an SPP account and invest the money into a conservative fund consisting of bonds and earning an average annual return of only 4 percent, the employee could have more than $50,000 in an SPP account at the end of the 14‑year period. Even a modest account balance of $50,000 could substantially improve the retirement security of this employee.

Saving Improves Financial Security Most for Certain Employees

Although everyone can benefit from saving money for their retirement during their career, retired long‑term state employees likely could retire without relying heavily on savings because of the level of financial security provided by state‑funded benefits. However, there are many state employees who could significantly improve their financial security in retirement by saving more money on their own during their working career. In particular, we think the employees who could benefit most from putting aside money include:

- Shorter‑Term Employees. People who work less than a full career with the state.

- Lower‑Paid Employees. People who might need money in addition to their pension to cover essential costs in retirement.

- Future Employees. People who will earn less generous retiree health and pension benefits.

As we discuss below, SPP provides these employees with an important opportunity to save money for their retirement and improve their financial security in retirement. However, data suggest that these employees may be less likely to save money in SPP.

Shorter‑Term Employees. The average retired state employee retires after working more than 20 years. However, many people do not work this long with the state. Employees who work fewer than a couple of decades with the state or who do not retire immediately after their state career receive far less financial security in retirement than long‑term employees who retire from state service. This is especially true in the case of future employees (1) whose pensions are based on PEPRA formulas that require them to work additional years to receive a benefit comparable to the benefit received by classic employees and (2) who must work with the state for at least 15 years to receive any state retiree health benefit. Similarly, employees with large gaps between the date they last worked for the state (or another government employer) and the date they begin collecting a pension from CalPERS can improve their retirement security through a retirement savings account. This is because CalPERS pension benefits are calculated based on an employee’s final compensation with no adjustment to the final compensation to account for any inflation in the economy that may have occurred since the date the final compensation was received.

Lower‑Paid Employees. Many expenses in retirement are not discretionary. These basic costs of living include housing, transportation, food, healthcare, and clothing. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average person aged between 65 years and 74 years spent about $38,000 on these categories of expenditures in 2014. A retired state employee who worked a long career with the state likely would have somewhat lower basic costs of living as the state’s contributions would pay for a large portion of the retiree’s healthcare. Although the state’s pension benefit replaces a significant portion of a person’s final salary, there are many state classifications that are paid a low enough salary that employees retiring from these classifications with long careers could be at risk of not being able to pay for basic costs of living. Without other sources of income in retirement, retired lower‑paid state employees are (1) more likely to take Social Security payments earlier in life, resulting in a smaller benefit and (2) at a greater risk of receiving government‑funded benefits for lower‑income individuals. Although lower‑paid employees would benefit from having assets in a retirement savings account, it likely is financially difficult for many of these employees to contribute money to an account during their career.

Future Employees. All retired future state employees will face higher healthcare costs than current retirees under the state’s planned changes to retiree health benefits. This especially is true for retired future employees who work fewer than 15 years with the state and receive no state contribution towards their healthcare. Retired future state employees would benefit from the ability to use assets in a retirement savings account to pay for these higher and rapidly growing costs in retirement. In addition, because PEPRA pensions are calculated based on an employee’s salary up to a limit established in statute ($117,020 in 2016), higher‑paid PEPRA state employees have a great incentive to use a retirement savings account. This is because they will receive a lower replacement ratio from their state pension than lower‑paid employees.

Saving Creates Great Opportunity for Younger Employees

Members of the Millennial Generation—people born between the early 1980s and the early 2000s—are expected to become a majority of the state workforce within the next ten years as state employees who were born before the mid‑1960s (currently about 40 percent of the state workforce) exit the workforce. At least in the beginning of their careers, these younger people are more likely to be in the three groups discussed above whose retirement security can benefit most from saving in SPP. Regardless of whether these future employees are lower‑paid or shorter‑term employees, younger employees have the greatest opportunity to maximize returns on their investment through the power of compounding interest.

Maximize Power of Compounding Interest. One of the most powerful factors that affect retirement savings is time. Long‑term investors gain returns on both their initial investment and past returns on that investment—a phenomenon referred to as compounding interest. The result of compounding interest is that the growth of the retirement savings account accelerates over time, allowing investors to reach long‑term savings goals with a smaller principal investment. For example, $10,000 invested with an average annual return of 5 percent will grow to (1) about $16,300 after 10 years but (2) more than $43,000 after 30 years. Although older people can take advantage of compounding interest by delaying when they begin to drawdown funds from their retirement savings, younger people benefit the most. Having a long time horizon also allows younger people to invest their money in portfolios of stocks and bonds with higher expected average returns for longer periods of time.

LAO Comments

SPP Benefits Employees and the State. The SPP program is an important benefit the state offers employees as part of its employee compensation package. Compared with deferred compensation programs offered by other employers, the state’s program offers participants low fees and the ability to contribute up to the maximum contribution to two retirement savings plans. The relatively high regular participation among higher‑paid state employees indicates that SPP currently is an attractive investment vehicle for them. An important benefit of the program is that it assists lower‑paid state employees by providing supplemental income in retirement. This additional income can significantly improve a retired employee’s financial security—especially in the years between retiring from the state and collecting Social Security. Improving the retirement security of lower‑paid state employees also benefits the state by reducing the risk that the state will incur future costs to provide these people benefits via programs that assist low‑income Californians.

Key Groups of Employees Not Participating in Program. While participation among some groups—notably older and more highly paid state employees—is encouraging, groups that could benefit most from using the program are much less likely to participate. Employees who receive less retirement security from the state‑funded retirement benefits—shorter‑term, lower‑paid, and future employees—could see the greatest improvement in their retirement security by participating in the program. In addition, SPP provides younger employees—who are more likely to be one of these three groups and who have a long time before they will retire—the opportunity to improve their retirement security with a smaller initial investment than would otherwise be required. The state currently creates little incentive for these employees to participate in the program during their state careers.

Legislative Options to Improve Participation

Changing a retirement benefit is a significant policy decision that can have very long‑term effects on the state’s finances, the financial security of state employees, and the state’s ability to recruit and retain employees. Accordingly, changes in retirement benefits should involve careful legislative deliberation and input to the Legislature from employees, the administration, experts inside and outside of state government, and the public.

Review Policies Other Employers Have Adopted to Improve Participation. Many employers who sponsor deferred compensation plans have adopted policies aimed at increasing participation among their employees. (Soliciting input from public and private employers with these policies could be valuable.) These policies seem to have improved participation nationally. That being said, there still are many people who are eligible to participate in a deferred compensation plan who choose not to participate. The Legislature could consider adopting similar policies to improve participation in SPP. The most common policies that employers have adopted to improve participation include:

- Auto‑Enrollment and Auto‑Escalation. Through auto‑enrollment, an employer automatically enrolls new employees into the deferred compensation plan with a default contribution amount and investment option. Through auto‑escalation, the employer automatically increases the contributions that employees make to the plan over a period of time. Employees can choose to (1) make contributions or choose investment options other than the default options or (2) opt out of the plan entirely. Auto‑enrollment and auto‑escalation features can boost overall participation in savings programs and have become more common in recent years. If implemented without an employer match, these policies would have no direct cost for the state.

- Employer Match. Employer matches come in different forms but the basic concept is that the employer makes contributions to the plan if the employee makes contributions. This creates an incentive for employees to make sufficient contributions to at least receive the full employer match so they are not “leaving compensation on the table.” Offering an employer match for employee contributions to SPP would not necessarily cost the state more money. It is possible for the Legislature to create an option to offer an employer match that is cost‑neutral relative to current policy—for example, by moderating growth of other types of compensation. One thing to consider before offering a match is that some employees are more likely than others to participate. For example, based on past experience, higher‑paid state workers may be more likely to contribute to a plan and thus benefit from an employer match. Consequently, some employees will receive higher levels of compensation than others based on their decisions of whether or not to participate.

Take Time to Understand Effects of Policy Changes. If the Legislature wants to change SPP to improve participation, it should hold hearings to determine what action—if any—is necessary and take its time to develop the right path forward. Among the topics discussed during these hearings, the Legislature could consider the following questions:

- What Is the Purpose of SPP in a Compensation Package That Includes Pension Benefits? The state is known for offering a generous pension to employees who work with the state for many years. That being said, SPP can greatly improve the retirement security of many state employees—especially employees who work fewer than 15 years with the state, have many years before retirement, or could benefit from supplementing their pension benefits with other sources of income.

- How Could Changes to SPP Affect Other Elements of Compensation? As the recent labor agreements implementing the Governor’s retiree health prefunding plan have demonstrated—changes in retirement benefits can have significant effects on other elements of compensation. It is possible that some approaches to improving participation in SPP could create pressure to make changes elsewhere in employee compensation at the bargaining table.

- How Could Changes to SPP Affect Employee Recruitment or Retention? There always exists a tension between providing valuable benefits that attract and retain qualified employees and minimizing costs to the state. Changing SPP could involve additional state costs. But what benefit would the state see in terms of recruiting and retaining quality employees? Opinions might vary and the Legislature would want to solicit feedback on this issue before making changes to SPP.

- Is the State Willing to Incur Cost to Increase Participation? The state already is paying significant sums of money to fund the current structure of state employee retirement benefits. Under current policy and assumptions, these costs will grow for the foreseeable future. Any discussion of offering an employer match should be considered in the broader context of the state budget.

- Can SPP Improve Account Balances Without Legislative Action? SPP could take a number of actions to improve account balances without any formal legislative action. In particular, increasing minimum contribution requirements to a meaningful contribution amount or creating stricter requirements for participants to initiate loans could significantly increase the amount of money participants have in their accounts upon retirement. (It is our understanding that SPP plans to implement stricter requirements for participants to initiate loans effective April 1, 2017.) The program would need to weigh the benefit of increasing regular contributions against the potential cost of a higher minimum contribution discouraging employees from participating. In addition, the Legislature could consider whether the existing law requiring SPP to offer an annuity product (discussed in the box below) could be changed to make that goal more realistic.

Conclusion

Employee compensation policies are complex and have long‑term effects on the state’s finances and the wellbeing of state employees. The SPP program is one facet of the state’s employee compensation package. SPP offers employees a low‑cost retirement savings option; however, many state employees whose retirement security would benefit most from the program do not regularly use the program to save money for their retirement. Recent changes that reduce other retirement benefits in the state’s compensation package create an opportunity for the state to consider SPP’s role in recruiting and retaining employees and enhancing retirement security for state employees. That being said, any change to the program should not be made without careful deliberation.