LAO Contact

March 16, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Analysis of Child Care and Preschool Proposals

- Introduction

- Child Care and Preschool in Context

- Overview of Governor’s Budget Proposals

- Analysis of Preschool Proposals

- Quality Improvement Activities

- Alternative Payment Agencies

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Governor’s Budget Includes $3.8 Billion for Child Care and Preschool Programs. The Governor’s budget augments child care and preschool programs by a total of $76 million (2 percent) from the revised 2016‑17 level. This augmentation primarily supports the full‑year cost of the Regional Market Rate and State Preschool slot increases initiated last year pursuant to a multiyear budget agreement. Though the Governor proposes to fund these parts of the multiyear agreement, he does not fund other parts. The Governor also makes caseload changes for CalWORKs and non‑CalWORKs child care programs and increases Transitional Kindergarten funding. Under the Governor’s budget, proposed funding would support an estimated 437,000 child care and preschool slots.

Preschool

Governor Proposes Changing Certain Requirements for Certain Preschool Providers. The Governor also proposes several preschool‑related policy changes. Specifically, the Governor proposes to allow part‑day State Preschool programs to serve children with special needs from families above the income threshold as long as all eligible and interested children are served first. The Governor also makes several proposals intended to more closely align State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten by modifying certain licensing, staffing, and program duration requirements.

Concerns With Preschool Proposals. We are concerned that allowing State Preschool programs to serve children above the income threshold would displace low‑income children who are currently eligible but unserved. Additionally, we are concerned that the Governor’s other preschool proposals make an already complicated system more complicated, without creating much alignment between programs.

Recommend Different, More Holistic Approach. We recommend the Legislature ensure already eligible children are served before expanding preschool eligibility. We also recommend the Legislature reject most of the preschool alignment proposals and take a more holistic approach. Under such an approach, the Legislature would consider how best to serve four‑year olds, including what eligibility criteria, program standards, and funding levels it desired for these children. Making these decisions in tandem would promote greater coherence.

Quality Improvement Activities

California Department of Education (CDE) Recently Submitted Revised Quality Improvement Expenditure Plan. The federal government requires California to spend a certain amount each year on activities to improve the quality of child care and preschool. In 2016‑17, the state spent $78 million (ongoing) to support about 30 quality improvement programs—some of which are run at the county level and others at the state level. As required by the 2016‑17 Budget Act, CDE submitted a revised quality improvement expenditure plan in February 2017. The revised plan leaves virtually all existing programs in place but eliminates one program and shifts a small portion of funding away from eight programs to create a $5.4 million Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) block grant for child care providers serving infants and toddlers. Block grant funds would be used to rate the quality of child care providers and support providers in achieving and maintaining high ratings.

Current System Has Several Serious Shortcomings. The state’s current quality improvement plan has several major shortcomings: existing county‑level activities can lack coordination and funding can be difficult to target to the highest priorities, little information is available on the effectiveness or efficiency of existing state‑level programs, and funding disproportionately serves providers that already meet higher standards. The department’s revised plan addresses a few of these issues by giving county‑level entities somewhat more flexibility in the activities they undertake and allowing them to serve some providers that do not meet higher standards. The proposal, however, restricts support to a small share of providers statewide (only those participating in QRIS) and does nothing to address the other shortcomings.

Recommend Shifting More Funding Into a New County Block Grant and Reassessing Most State‑Level Programs Over Next Several Years. We recommend repackaging $21 million from seven county‑level programs into a new county block grant that would allow county‑level agencies to support any provider serving subsidized children. We recommend funding the remaining state‑level programs as budgeted but hiring an independent evaluator to assess the cost‑effectiveness of these programs over the next several years. The Legislature could revisit funding levels for these programs in the future based on the results of the evaluations.

Alternative Payment (AP) Agencies

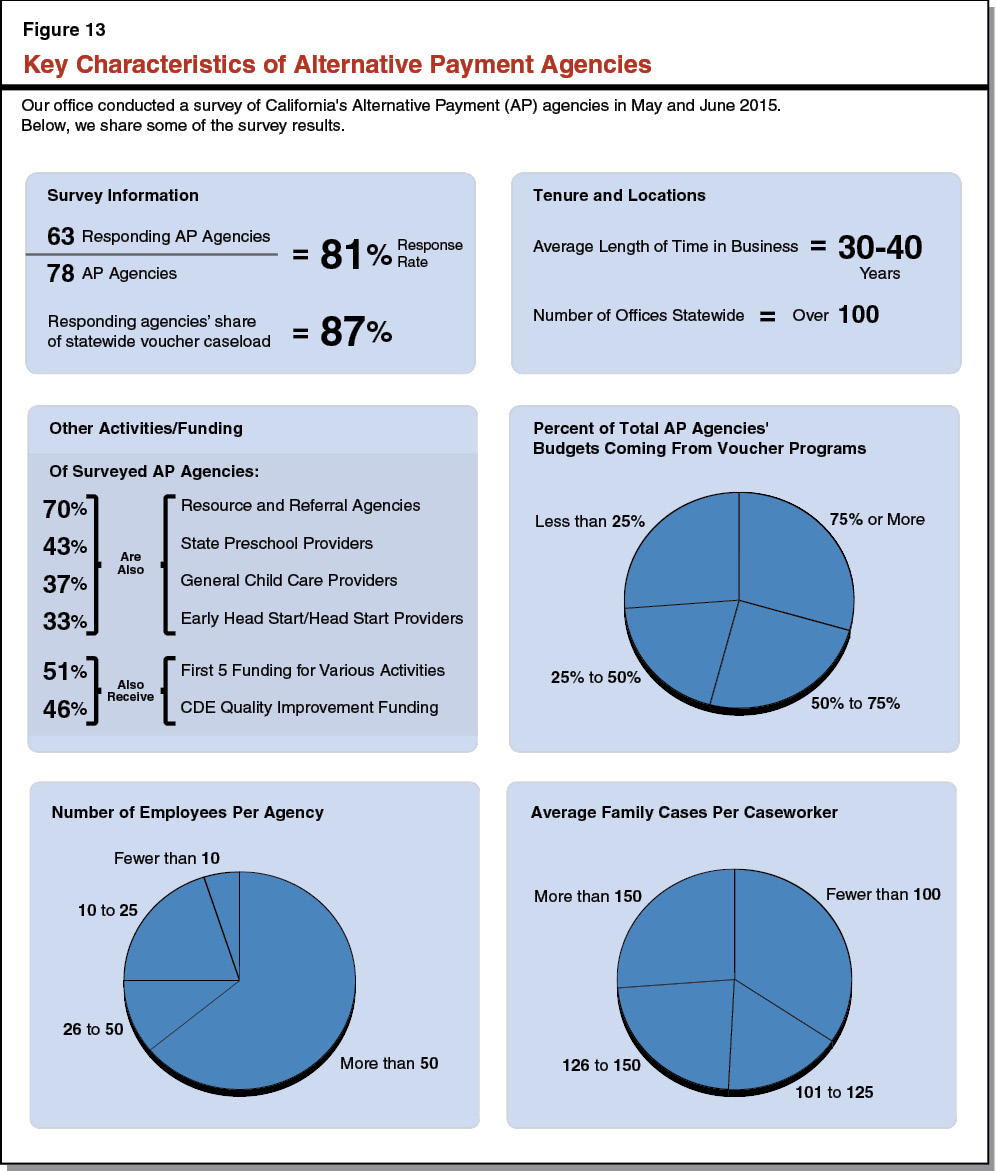

State Funds AP Agencies to Administer Most Voucher‑Based Programs. The state allocates AP agencies operational funding equal to 21 percent of the voucher payments they make to child care and preschool providers. The AP agencies’ primary activities involve determining family eligibility and paying providers.

Current Funding Model Not Tightly Linked With Underlying Cost Drivers. AP agencies’ costs are driven primarily by their caseload and the wages they offer their staff. Although the current funding model has some connection to these underlying cost drivers, some components of the model are not tightly linked to costs. Most notably, an AP agency working with providers that serve a larger share of infants and toddlers receives more operational funding than an agency working with providers serving older children, even though the amount of associated AP workload is the same. Agencies’ funding levels also fluctuate when provider rates change, despite no changes in associated AP workload.

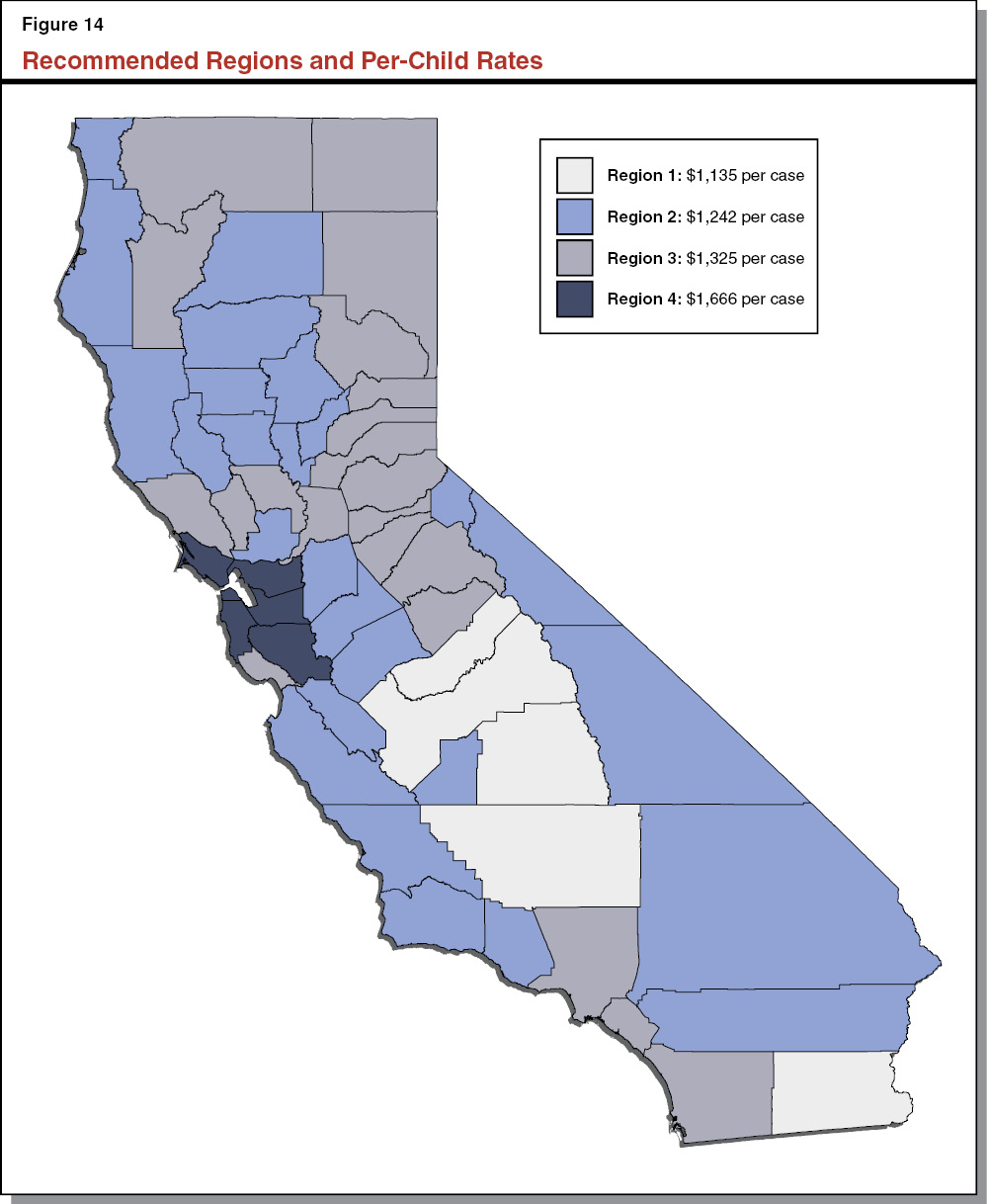

Recommend Adopting a Regionally Adjusted Per‑Child Funding Model. We recommend the state provide operational funding to AP agencies based on the number of children served. We recommend the state adjust these rates based on regional wage data and phase in the new system over several years.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s child care and preschool proposals. The report has six main sections. In the first section, we provide background on child care and preschool programs in California. In the second section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s child care and preschool proposals. In the third section, we analyze the Governor’s preschool proposals and make associated recommendations. In the following two sections, we provide in‑depth analyses of (1) the state’s various quality improvement activities and (2) Alternative Payment agencies, which administer certain child care programs. The final section consists of a summary of the recommendations we make throughout the report.

Child Care and Preschool in Context

In this section, we provide a high‑level overview of the child care and preschool system in California and then discuss eligibility and access, settings and standards, funding, and trends over the last decade.

Overview

Three‑Fifths of Children Under 13 in California Live in Families Where Parents Work or Are in School. According to 2015 American Community Survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau, 6.6 million children in California are under the age of 13. Of these children, about 60 percent live in families where all parents or guardians work or are in school. As a result, many families must find child care arrangements for their children. Children may be cared for in settings licensed by the state or in non‑licensed settings, such as the home of another family member, friend, or neighbor.

California Subsidizes Child Care and Preschool for Some Families. In 2016‑17, California allocated nearly $3.7 billion to provide 434,000 children with subsidized child care and preschool. Of these children, 12 percent are birth through age 2, 59 percent are ages 3 and 4, and 29 percent are age 5 or older. The funding primarily benefits children from low‑income, working families. As Figure 1 shows, the funds are spread across nine state programs. Three programs relate to California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), focusing on families engaged in or transitioning out of welfare‑to‑work activities. The remaining programs are designed for other low‑income, working families. In addition to the programs that directly provide subsidized child care and preschool, California provides two tax benefits. The Child Care and Dependent Tax Credit supports about 180,000 tax filers who pay for child care or preschool with an annual tax credit of up to $516 per filer. The Employee Child and Dependent Care Benefit Exclusion allows taxpayers to exclude up to $5,000 of income per year from tax calculations if their employer offers a payroll deduction program for child care expenses. These provisions primarily benefit families with incomes over $50,000.

Figure 1

State’s Child Care and Preschool Programs

|

Program |

Description |

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

|

|

Stage 1 |

Child care becomes available when a participant enters the CalWORKs program. |

|

Stage 2 |

Families transition to Stage 2 child care when the county welfare department deems them stable. |

|

Stage 3 |

Families transition to Stage 3 child care two years after they stop receiving cash aid. Families remain in Stage 3 until the child ages out (at 13 years old) or they exceed the income eligibility cap. |

|

Non‑CalWORKs Child Care |

|

|

General Child Care |

Program for low‑income, working families that subsidizes care provided in licensed settings. |

|

Alternative Payment |

Program for low‑income, working families that subsidizes care provided in licensed and non‑licensed settings. |

|

Migrant Child Care |

Program for migrant children from low‑income, working families. |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

Program for children with severe disabilities living in the Bay Area. |

|

Preschool |

|

|

State Preschool |

Part‑day, part‑year program for low‑income families. Full‑day, full‑year program for low‑income, working families. |

|

Transitional Kindergarten |

Part‑year program for four‑year olds with birthdays between September 2 and December 2. May run part day or full day. |

Federal Government and Local Agencies Also Subsidize Programs. The federal government subsidizes child care and preschool through Early Head Start (serving children birth through 2) and Head Start (serving children ages 3 through 5). In 2015‑16, the federal government allocated roughly $1 billion to providers in California that served 109,000 children through these programs. The federal government also has a child care tax credit, which provides about 670,000 Californians with an annual credit of up to $6,000. Finally, some school districts support preschool programs using federal Title I funds, special education funding, or local funds.

Eligibility and Access

Below, we discuss eligibility criteria and access to the state’s various child care and preschool programs.

Eligibility Criteria

For Most Programs, Eligibility Based on Income and Working Status. To be eligible for subsidized child care, children must be under the age of 13 and from a family with an income below 70 percent of state median income (SMI) as calculated in 2007 ($42,216 for a family of three). Parents also must demonstrate a “need” for care during the hours that the state subsidizes—for example, they must be working, looking for work, in school, or unable to care for their child for medical reasons. Homeless children and children identified as being (or at risk of being) abused or neglected also are eligible for child care, regardless of parent income and work status.

Additional Eligibility Criteria for Migrant Child Care and Care for Children With Severe Disabilities. For Migrant Child Care, families must meet all the criteria for the state’s child care programs as well as earn at least 50 percent of their gross income through agricultural work. To be eligible for subsidies through the Care for Children With Severe Disabilities (CCSD) program, a child must have a physical, mental, or emotional handicap of such severity that he or she cannot be served appropriately in another child care program (as determined by the individualized education program designed by a special education team). Children participating in CCSD may remain in the program until they reach 21 years of age. The CCSD program is available only in the Bay Area.

Special Rules for State’s Preschool Programs. State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten each has its own set of rules regarding the age of children served, family income, and work requirements.

- Age. State Preschool providers primarily serve four‑year olds but may enroll three‑year olds if all eligible and interested four‑year olds have been served. School districts are required to provide Transitional Kindergarten to all children who turn five between September 2 and December 2. (Districts also can choose to serve children with birthdays between December 2 and the end of the school year, but only receive funding for these children after their fifth birthday.)

- Income. Whereas State Preschool shares the same income threshold as state child care programs, it allows up to 10 percent of children to be from families with incomes up to 15 percent above the income threshold if all eligible and interested children have been served. Transitional Kindergarten has no income‑eligibility requirements.

- Work Status. To enroll their children in full‑day State Preschool, families must demonstrate they have a need for care during the hours the program operates. Part‑day State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten, however, do not require families to demonstrate that they have need for care (that is, they do not need to be working or in school for their children to participate in the programs).

California’s Eligibility Criteria Relatively Generous Compared to Other States. A National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) survey of states from February 2016 shows that California’s income‑eligibility threshold results in a higher percentage of families being eligible for child care than in 41 other states. In addition to having a higher income threshold, California has fewer other eligibility restrictions than many states. For example, 22 states require parents to work a minimum number of hours per week to receive care, while 20 states cap the number of hours parents can receive child care. California imposes neither of these restrictions.

Access

CalWORKs and Transitional Kindergarten Families Guaranteed Services. By statute, the state guarantees child care subsidies for CalWORKs families from their initial participation until two years after they stop receiving cash aid (known as CalWORKs Stage 1 and Stage 2 child care). Families off cash aid for more than two years are not statutorily guaranteed child care subsidies, but the Legislature typically has funded all eligible families (through CalWORKs Stage 3 child care). California is relatively generous to its welfare‑to‑work population in this regard. Only 20 other states guarantee child care for welfare‑to‑work recipients and only 17 other states guarantee child care for families transitioning off welfare‑to‑work. All children eligible for Transitional Kindergarten also are statutorily guaranteed a spot in their local school district program.

All Other Families Are Prioritized Based on Income. Given state funding historically has been insufficient to serve all families eligible for non‑CalWORKs child care and State Preschool programs, the state requires providers to prioritize children based on a number of factors. Providers must give first priority to children who are receiving child protective services or at‑risk of abuse or neglect. Once all such children are served, providers must serve children from families with the lowest incomes. To that end, providers place interested families into income brackets and must first offer child care to all families in the lower income brackets before offering to families in higher brackets. Within each income bracket, the state requires providers to prioritize children with special needs. A family who does not immediately receive a subsidized slot may request to be placed on a provider’s waiting list. In some areas, providers may work together to develop centralized eligibility lists so that a family can put its name on one list and be alerted if any slot in the area becomes available. (Every county had a centralized eligibility list between 2005 and 2010, when the state provided direct funding for the development and maintenance of these lists.)

School‑Aged Children Also Can Participate in After School Programs. Families with school‑aged children have access both to the child care system and various after school programs that may be funded by the state, the federal government, their school, or other organizations in their community. Families may use both after school programs and child care. For example, a family could enroll their child in an after school program during the school year and use child care during the summer and winter breaks. The box below describes the two major after school programs currently available to families.

Two Major After School Programs

After School Education and Safety (ASES) Program. In 2002, voters passed Proposition 49, which created the ASES program. Funded beginning in 2006‑07, ASES provides $550 million annually to support after school programming for children at schools with high concentrations of low‑income students. In 2016‑17, ASES served about 400,000 children in kindergarten through ninth grade at 4,201 schools. The average program operates in schools where four‑fifths of students are eligible for free or reduced price meals. (This threshold equates to about $37,000 per year for a family of three.) Programs must operate a minimum of 15 hours per week and must include an educational component (such as tutoring) and an enrichment component (such as art, music, physical activity, career awareness, or community service).

21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st CCLC). California also receives about $130 million for after school programs through the federal 21st CCLC program. In 2016‑17, the program served about 70,000 students at 684 schools. (About 55 percent of these schools also received funding through ASES.) The average 21st CCLC program operates in schools with similar shares of low‑income students as ASES. The 21st CCLC’s program requirements also are very similar to ASES, with each program operating a minimum of 15 hours per week and including both educational and enrichment components. Unlike ASES, however, 21st CCLC funds can be used to run programs for high school students.

Settings and Standards

Below, we discuss child care settings and standards.

Settings

Children Receive Care in a Variety of Settings. Child care and preschool are provided in four types of settings: licensed centers, licensed family child care homes (FCCHs), license‑exempt homes, and classrooms. Centers typically are run by community‑based organizations or local education agencies and serve an average of about 50 children. Run by interested individuals out of their own homes (modified in certain ways to meet licensing standards), FCCHs may each serve up to 14 children. License‑exempt care is typically provided by a family’s relative, friend, or neighbor in the provider’s private home. These providers can provide care only for one family at a time. Transitional Kindergarten programs are run by school districts in a classroom setting similar to kindergarten. These programs are not subject to licensing requirements. In 2015‑16, the average kindergarten classroom had 23 students.

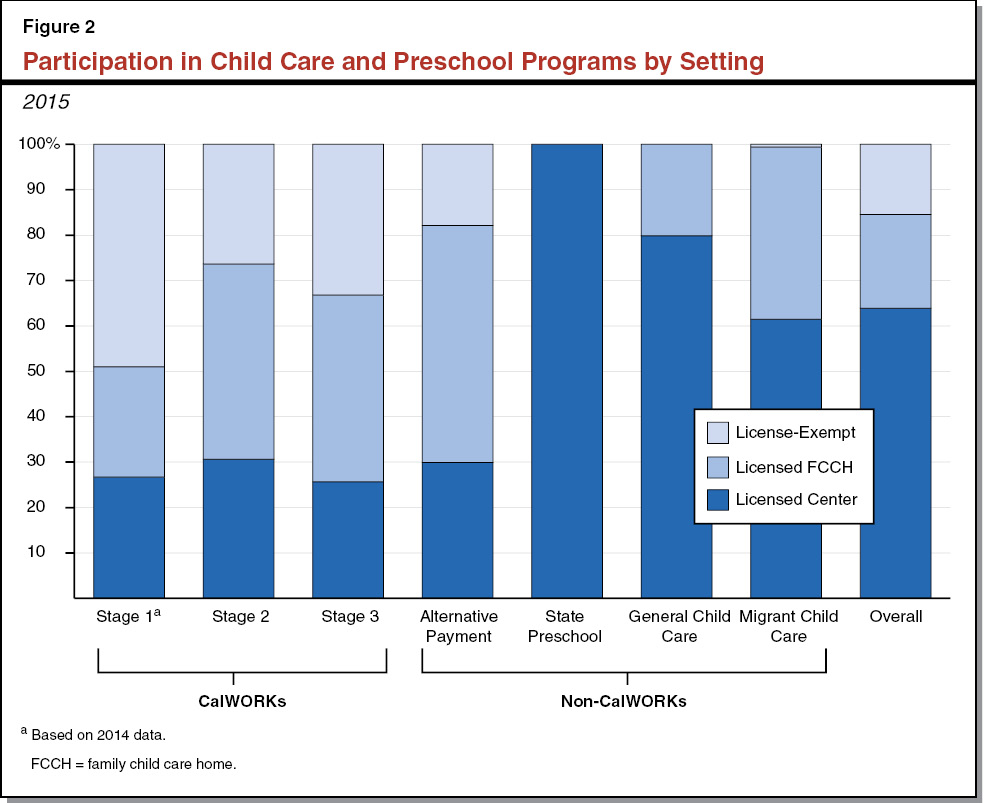

Use of Particular Settings Varies Across Programs. Figure 2 shows the types of settings in which subsidized children are served by the various child care and preschool programs, excluding Transitional Kindergarten. As the figure shows, 85 percent of children were served in licensed settings in 2015—64 percent in centers and 21 percent in FCCHs. Although a relatively small share of children are served in license‑exempt settings, the amount varies substantially by program. In CalWORKs Stage 1, for example, almost half of families use license‑exempt care, whereas in the Alternative Payment program, 18 percent of children use license‑exempt care. The State Preschool and General Child Care programs do not allow for license‑exempt care.

Use of Particular Settings Also Varies Across Counties. The percentage of subsidized children in centers ranges from 5 percent in Mariposa County to 85 percent in El Dorado County. The percentage of subsidized children in FCCHs ranges from 10 percent in Fresno County to 80 percent in Mariposa County. Variation in use of license‑exempt care is lower, ranging from less than 1 percent in Sierra County to 24 percent in San Bernardino County.

California Relies More on License‑Exempt Care Than Other States. Based on preliminary federal Health and Human Services (HHS) data from 2015 (the most recent data available), California ranks 11th among the 50 states in terms of having a relatively high percentage of subsidized children in license‑exempt child care. California has a relatively high percentage of children in license‑exempt settings receiving care offered by relatives (such as a grandparent), ranking 10th in the nation.

Standards

Standards Vary Across Programs and Settings. As Figure 3 shows, all licensed providers, at a minimum, must meet health and safety standards. Licensed providers serving children in the CalWORKs and Alternative Payment programs (or other children not subsidized by the state) also must meet certain staff qualifications and staffing ratios, with more stringent requirements for centers than FCCHs. Compared to the CalWORKs and Alternative Payment programs, the General Child Care and State Preschool programs require somewhat higher staff qualifications and staffing ratios.

Figure 3

Standards by Program and Setting

Infant Children (Through 24 Months Olda)

|

CalWORKs, |

General Child Care, CCSD, and Certain Migrant Child Care Programs |

||||

|

License‑Exempt |

FCCHs |

Centers |

Centersb |

||

|

Health and Safety Standards |

Criminal background check. Self‑certification of certain health and safety standards. |

Staff and volunteers are finger printed. Subject to health and safety standards. |

Same as shown for FCCHs. |

Same as shown for FCCHs. |

|

|

Staff Qualifications |

None. |

15 hours of health and safety training. |

Child Development Associate Credential or 12 units in ECE/CD.c |

Child Development Teacher Permit (24 units of ECE/CD plus 16 general education units).d |

|

|

Staffing Ratios |

May serve children from only one family at a time. |

1:4 adult‑to‑child ratio.e |

1:12 teacher‑to‑child ratio and 1:4 adult‑to‑child ratio. |

1:18 teacher‑to‑child ratio and 1:3 adult‑to‑child ratio. |

|

|

Developmental Standards |

None. |

None. |

None. |

Requires developmentally appropriate activities. |

|

|

Oversight |

None. |

Unannounced visits by CCL every three years or more frequently under special circumstances. |

Same as shown for FCCHs. |

Same as shown for FCCHs, but also onsite reviews by CDE every three years (or as resources allow) and annual self‑assessments. |

|

|

aStandards for children of other ages similar to those displayed here. For General Child Care, CCSD, and certain Migrant Child Care programs, standards apply to children through 18 months old. bSame standards generally apply to FCCHs serving children in General Child Care and certain Migrant Child Care programs. cThe Child Development Associate Credential is issued by the National Credentialing Program of the Council for Professional Recognition. dThe Child Development Teacher Permit is issued by California’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing. eRatio applies when all children in home are infants. When mix of ages in home, can have up to 1:8 adult‑to‑child ratio. CCSD = Care for Children With Severe Disabilities; CCL= Community Care Licensing; CDE = California Department of Education; ECE/CD = Early Childhood Education/Child Development; and FCCHs = family child care homes. |

|||||

Some Programs Also Required to Include Developmental Component to Care. In addition to being subject to health, safety, and staffing standards, the General Child Care and State Preschool programs must provide children with developmentally appropriate activities. This developmental component often is referred to as “learning foundations” after the frameworks developed by the California Department of Education (CDE) for the programs. The learning foundations describe the skills that children of different ages should be able to exhibit.

Program Monitoring Varies by Provider Type. Community Care Licensing (CCL), which is part of the Department of Social Services (DSS), processes applications for child care licenses and periodically monitors all licensed entities to ensure compliance. These reviews relate to all health, safety, and staff standards. The General Child Care and State Preschool programs are subject to these CCL reviews as well as CDE reviews. The CDE reviews check that providers meet the higher staff standards and offer developmentally appropriate activities.

Transitional Kindergarten Has Different Standards and Monitoring System. Transitional Kindergarten is subject to the standards that apply to kindergarten. Specifically, Transitional Kindergarten teachers must have a multiple subject Teaching Credential. Teachers hired after July 1, 2015 also must demonstrate knowledge in early childhood education (through coursework or previous work experience). Class sizes cannot exceed 33 students, with no requirements for additional instructional aides to support teachers. As with all other school buildings, school districts are required to keep Transitional Kindergarten facilities in good repair but are not required to meet CCL health and safety standards. Regarding program standards, Transitional Kindergarten classrooms are required to use a modified kindergarten curriculum that is age and developmentally appropriate. Transitional Kindergarten class sizes—as well as class sizes for all other grades—are reviewed as part of a school district’s annual independent audit.

Federal Law Requires State to Spend a Certain Amount Each Year on Quality Improvement Activities. In 2016‑17, the federal government required the state to spend $78 million on quality improvement activities. The state allocated almost half of these resources to training and professional development activities, including stipends for early educators to take more classes and direct funding for various trainings and resources. The rest of the funds supported activities such as resource and referral services for parents seeking child care, licensing enforcement, and coordination among local child care agencies.

State Also Supports Local Quality Rating Improvement Systems (QRIS). In 2012‑13, California received a $75 million four‑year grant from the federal government to develop and fund QRIS. A portion of the funds went to create a common matrix that rates child care and preschool providers based on a certain set of indicators, including staff qualifications, ratios, and environment. The remaining funds went to 17 local QRIS consortia to rate programs and help those programs achieve and maintain high ratings. Subsequent state and local funding has expanded QRIS to 48 consortia serving the entire state. Each consortium is responsible for rating participating programs according to the common matrix and deciding how to assist providers. Support services vary by consortium, but typically include stipends to allow teachers to take more early education classes, coaching for staff, grants to help providers improve their classroom environment, and additional funding for highly rated sites. California is 1 of 42 states with a QRIS. Unlike most other states, however, California’s QRIS is locally run, with QRIS consortia in each county conducting the ratings and deciding what kind of support will be the most beneficial to participating providers.

Funding

Below, we discuss funding sources and allocations, reimbursement rates, and family fees.

Funding Sources and Allocations

Child Care and Preschool Supported With Mix of State and Federal Funding. In 2016‑17, state funding (Proposition 98 and non‑Proposition 98 General Fund combined) comprised approximately 70 percent of total funding, with federal funding comprising the remainder. Federal support is provided through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Whereas TANF supports CalWORKs child care, CCDF is blended with state funding to support the state’s child care and preschool programs generally. The federal law governing CCDF was recently reauthorized. The box below highlights substantial changes in the new act.

Federal Government Recently Reauthorized CCDBG Act With New Rules

The federal government reauthorized the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) Act in 2014 and made substantial changes to the rules at that time. Many of these changes would require both changes in state law and additional funding. The more substantial changes include: (1) requiring states to reimburse providers based on the most recent Regional Market Rate survey, (2) requiring states to allow subsidized families to continue to receive child care until their incomes reach 85 percent of the most recent State Median Income, (3) allowing families to remain eligible for child care if changes in income and work status are minor or likely temporary, (4) requiring annual inspections of licensed and license‑exempt providers who serve subsidized children, and (5) increasing the amount the state is required to spend on quality improvement activities. The state has been granted until September 30, 2018 to comply with the new rules. The consequences for failing to comply with the new requirements after that time are unclear.

State Subsidizes Programs in Four Ways. The DSS provides funding for CalWORKs Stage 1 child care to county welfare departments via a “single allocation,” which can be used for any combination of Stage 1 child care and welfare‑to‑work services. County welfare departments then use this funding to determine eligibility and issue voucher payments to the child care provider of the family’s choice. For CalWORKs Stage 2, Stage 3, and the Alternative Payment program, CDE provides funds directly to Alternative Payment agencies to make child care voucher payments (with a specified share set aside to cover agencies’ operational costs). For the General Child Care, State Preschool, and CCSD programs, the state directly contracts with providers to serve a specified number of eligible children. For the Migrant Child Care program, the state subsidizes care using both vouchers and direct contracts. Finally, the state provides grants to school districts for Transitional Kindergarten through the state’s K‑12 funding formula.

Reimbursement Rates

State Generally Funds Contract‑Based Providers Using Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR). Providers running the General Child Care, State Preschool, contract‑based Migrant Child Care, and CCSD programs generally are paid using the SRR. The SRR is higher for centers than FCCHs and is adjusted to account for length of care and various characteristics of the child served—including age, limited English proficiency, or having a disability. Over the years, the state periodically has updated the SRR to reflect increasing program costs.

State Funds Voucher Providers Using Regional Market Rate (RMR). Reimbursement rates for voucher providers and certain General Child Care providers vary based on the county in which the child is served. These reimbursement rates are referred to as the RMR and are based on regional market surveys of private providers. Like the SRR, the RMR rates vary based on the age of the child, setting, and length of care. The state also applies an adjustment factor to the RMR rates for children with disabilities. Unlike the SRR, variation in RMR rates is based on the results of the regional market survey. The RMR sets the maximum amount the state is willing to pay for a certain type of care. If a provider charges less than the maximum amount, the state reimburses the actual charge. (The state currently reimburses license‑exempt providers at 70 percent of each county’s maximum RMR for FCCHs.) The state often sets the RMR at a certain percentile of the survey. This percentile effectively reflects the purchasing power and amount of choice associated with a voucher. Currently, the state links the RMR to the 75th percentile of the 2014 survey, ensuring that all children have access to at least 75 percent of their local child care providers.

Most States Base RMRs on Outdated Market Information. Federal law requires states to conduct regional market rate surveys every three years, but it has not always required states to base child care rates on the most recent surveys. As a result, many states (including California) have not always updated their actual RMR ceilings to reflect the most recent survey results. For example, the state used the 85th percentile of the 2005 survey as the basis for setting rates for five years, even though more up‑to‑date surveys were available during this period. A February 2016 NWLC survey shows that one‑third of states were using RMRs based off of market information more than five years old. Of the states that were using more recent market information, most states set the rates at or below the 75th percentile.

California Relies More on Contracts Than Other States. Preliminary federal HHS data from 2015 shows that California is 1 of 12 states that directly contracts with child care and preschool providers. Among these states, California had the fourth‑highest share of child care and preschool slots funded via direct contracts. Most states rely primarily on vouchers to provide subsidized child care. In 2015, 30 states reimbursed providers using exclusively vouchers, whereas another 17 states reimbursed them using vouchers in conjunction with other payment methods, such as direct contracts. Five states provide cash directly to families either as the only funding mechanism or in combination with vouchers for providers or direct contracts.

State Funds Transitional Kindergarten Through Primary K‑12 Funding Formula. Funding for Transitional Kindergarten is provided through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), the state’s primary school funding formula. The LCFF provides schools with base per‑student funding, adjusted by four grade spans, with additional funding generated for students who are low income, English learners, or foster youth. The LCFF provides the same funding rate for students in Kindergarten (including Transitional Kindergarten) through third grade. As with Kindergarten, schools are required to offer only part‑day Transitional Kindergarten. They receive the same amount of funding per student whether they run part day or full day.

Rates for Similar‑Aged Children Vary by Rate System. As Figure 4 shows, annual reimbursement rates can vary substantially within the same age group and setting. For example, the RMR for centers that provide full‑time, full‑year care to a preschooler averages about $13,000—almost $3,000 higher than the equivalent SRR rate. Rates also differ notably for part‑time, preschool‑aged children in centers. The SRR rate, which funds the part‑day State Preschool program to operate for 175 days a year and at least four hours per day, is less than half the rate provided for Transitional Kindergarten, a program with similar school year and school day requirements (180 days per year, 3 hours per day). The RMR for part‑time, preschool‑aged children in centers is $559 higher than the Transitional Kindergarten Rate, although voucher‑based providers receive this level of funding based on about 250 days of care per year.

Figure 4

Comparing Reimbursement Rates for Centers

Annual Reimbursement Rates for Select Ages, 2016‑17a

|

Full‑Time Care |

Part‑Time Careb |

|

|

Infants (Birth to 18 Months) |

||

|

SRR |

$17,087 |

$12,815 |

|

RMR averagesc |

16,973 |

11,903 |

|

Toddlers (18 to 24 Months) |

||

|

SRR |

$14,072 |

$10,554 |

|

RMR averagesc |

16,973 |

11,903 |

|

Preschool (Ages 3‑4) |

||

|

SRRd |

$10,114 |

$4,386 |

|

RMR averagesc |

13,008 |

9,369 |

|

LCFFe |

N/A |

8,810 |

|

School‑Age (Ages 6‑12) |

||

|

SRR |

$10,051 |

$7,538 |

|

RMR averages |

9,408 |

5,993 |

|

aAll rates reflect cost of full‑year program, except for part‑time preschool SRR and LCFF rates. These rates reflect 175‑day and 180‑day programs, respectively. bSRR part‑time care rates based on 4 to 6.5 hours of care per day. cRMR average costs are weighted by the number of subsidized children receiving child care in each setting and county. Estimates assume half of children reimbursed at weekly rate and half at monthly rate. dDisplays State Preschool rates. eOperated by school districts, rather than licensed centers. SRR = Standard Reimbursement Rate; RMR = Regional Market Rate; and LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

||

Family Fees

State Charges Fees to Some Families. In all programs except part‑day State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten, families making above 40 percent of the SMI as calculated in 2007 (about $24,000 per year for a family of three) pay a family fee. These fees range from $21 to $373 per month, depending on family size, income, and whether children are in part‑ or full‑time care. In 2015‑16, the state collected $59 million in family fees. The use of family fee revenue varies by program. For the CalWORKs programs, where the state subsidizes all eligible families, parent fee revenue offsets state General Fund spending. For all other programs, where the state does not serve all eligible children, state practice is for fee revenue to serve additional children.

Family Fees in California Lower Than in Many Other States. According to the NWLC, in February 2016, the average state charged $206 per month to a family of three earning about $30,000 with one child in full‑time care. Such a family paid $128 per month in California, a lower monthly fee than in 40 other states. California also is one of three states that did not charge any fees to a family of three earning about $20,000 a year with one child in full‑time care. The average state charged a family of this size and income level $84 a month.

Trends Over Last Decade

Funding Cut During Recession, Increased During Recovery. Figure 5 shows funding for child care and preschool programs between 2007‑08 and 2016‑17. Funding for child care and preschool programs decreased by roughly $1 billion between 2007‑08 and 2013‑14. Since that time, funding for child care and preschool programs has increased by $871 million. We discuss these decreases and subsequent increases in more detail below.

Figure 5

Child Care and Preschool Funding Over Timea

(In Millions)

|

2007‑08 |

2010‑11 |

2013‑14 |

2016‑17 |

|

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

$1,442 |

$1,108 |

$862 |

$1,150 |

|

Non‑CalWORKs Child Care and Preschool |

1,711 |

1,608 |

1,251 |

1,834 |

|

Totals |

$3,153 |

$2,716 |

$2,113 |

$2,984 |

|

aDoes not include Transitional Kindergarten funding. Makes no inflationary adjustments. |

||||

Rates Mostly Flat During Recession, Increased in Recent Years. While most child care rates were held flat during the recession, the state reduced license‑exempt rates (from 90 percent to 60 percent of the FCCH rate). The state also reduced the rates for Alternative Payment agencies’ operational expenses by 8 percent. Starting in 2014‑15, the state provided three consecutive rate increases, with spending on rates in 2016‑17 $397 million higher than in 2013‑14. The state augmented the SRR by 17 percent over these three years ($198 million). The state also increased the RMR three times, most recently updating to the 75th percentile of the 2014 survey ($162 million). In addition, the state increased license‑exempt rates to 70 percent of the FCCH rates ($37 million).

Slots Decreased During Recession, Increased During Recovery. Between 2007‑08 and 2013‑14, CalWORKs slots decreased significantly, with 65,000 (35 percent) fewer slots in 2013‑14 than in 2007‑08. The reduction in slots was due to state actions that changed the number of CalWORKs families using child care. Most notably, beginning in 2009‑10, the state exempted certain CalWORKs parents with young children from the work requirement and allowed them to stay home while continuing to receive cash aid. Since 2013‑14, CalWORKs slots have increased by 6,148 (5 percent) due to the net effect of the state reengaging these families in the workforce and an offsetting decrease in the CalWORKs caseload due to an improving economy. Non‑CalWORKs slots also decreased notably between 2007‑08 and 2013‑14 with 44,000 (17 percent) fewer slots in 2013‑14 than in 2007‑08. This reduction was due to various across‑the‑board reductions to all non‑CalWORKs programs. Since 2013‑14, state augmentations resulted in non‑CalWORKs slots increasing with slots in 2016‑17 about 25,000 (12 percent) higher than in 2013‑14.

Some Changes in Quality Improvement Funding Activities. The state reduced its spending on a variety of quality improvement and support activities by $28 million (27 percent) between 2007‑08 and 2013‑14. Since 2013‑14, the Legislature has increased funding for quality and support activities by $65 million (87 percent). In addition to ongoing increases, the Legislature has provided $59 million in one‑time funding. The ongoing augmentation primarily has supported the State Preschool QRIS block grant, while the one‑time funding has supported preschool teacher training, QRIS for infants and toddlers, and loans for acquiring portable preschool facilities.

Overview of Governor’s Budget Proposals

In this section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s child care and preschool budget, then describe his major spending and policy proposals.

Governor Proposes $3.8 Billion for Child Care and Preschool Programs in 2017‑18. Of this amount, about half is for child care programs and half for preschool programs. As Figure 6 shows, the Governor’s budget augments these programs by a total of $76 million (2 percent) from the revised 2016‑17 level. Proposition 98 General Fund accounts for $30 million of this increase, with the remainder covered by federal funds ($28 million) and non‑Proposition 98 General Fund ($18 million). Under the Governor’s budget, proposed funding would support 437,000 child care and preschool slots (a 1 percent increase from 2016‑17).

Figure 6

Child Care and Preschool Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

Change From 2016‑17 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Expenditures |

|||||

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

Stage 1 |

$334 |

$418 |

$386 |

‑$32 |

‑8% |

|

Stage 2b |

419 |

445 |

505 |

60 |

13 |

|

Stage 3 |

257 |

287 |

303 |

15 |

5 |

|

Subtotals |

($1,010) |

($1,150) |

($1,193) |

($43) |

(4%) |

|

Non‑CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

General Child Carec |

$305 |

$321 |

$319 |

‑$1 |

—d |

|

Alternative Payment Program |

251 |

267 |

279 |

12 |

4% |

|

Migrant Child Care |

29 |

31 |

31 |

—d |

—d |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

2 |

2 |

2 |

—d |

—d |

|

Infant and Toddler QRIS Grant (one time) |

24 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($611) |

($620) |

($630) |

($10) |

(2%) |

|

Preschool Programse |

|||||

|

State Preschool—part dayf |

$425 |

$447 |

445 |

‑$2 |

—d |

|

State Preschool—full day |

555 |

627 |

648 |

21 |

3% |

|

Transitional Kindergarteng |

665 |

704 |

714 |

10 |

1 |

|

Preschool QRIS Grant |

50 |

50 |

50 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($1,695) |

($1,828) |

($1,857) |

($29) |

(2%) |

|

Support Programs |

$76 |

$89 |

$82 |

‑$7 |

‑8% |

|

Totals |

$3,392 |

$3,688 |

$3,763 |

$76 |

2% |

|

Funding |

|||||

|

Proposition 98 General Fund |

$1,550 |

$1,679 |

$1,709 |

$30 |

2% |

|

Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund |

885 |

984 |

1,002 |

18 |

2 |

|

Federal CCDF |

573 |

639 |

606 |

‑32 |

‑5 |

|

Federal TANF |

385 |

385 |

446 |

61 |

16 |

|

aReflects Department of Social Services’ revised Stage 1 estimates. Reflects budget act appropriation for all other programs. bDoes not include $9.2 million provided to community colleges for certain child care services. cGeneral Child Care funding for State Preschool wraparound care shown in State Preschool—full day. dLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. eSome CalWORKs and non‑CalWORKs child care providers also use their funding to offer preschool. fIncludes $1.6 million each year used for a family literacy program at certain State Preschool programs. gReflects preliminary LAO estimates. Transitional Kindergarten enrollment data not yet available for any year of the period. QRIS = Quality Rating and Improvement System; CCDF=Child Care and Development Fund; and TANF=Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. |

|||||

Governor Proposes Suspending Much of Multiyear Budget Agreement. As part of the 2016‑17 budget package, the Legislature and the Governor agreed on a four‑year plan to increase ongoing child care and preschool funding by roughly $500 million (roughly $200 million in Proposition 98 General Fund and $300 million in non‑Proposition 98 General Fund). In 2016‑17, the state provided $145 million for the first year of implementation ($137.5 million for rates and $7.8 million for 2,959 additional State Preschool slots). Though not formalized in statute, the agreement for 2017‑18 assumed (1) annualization of the increases initiated the prior year, (2) 2,959 additional State Preschool slots, and (3) $86 million in non‑Proposition 98 General Fund rate increases. The Governor’s budget proposes annualizing some of the rate and slot increases initiated in 2016‑17 but suspending the rest of the agreement for 2017‑18. Given the one‑year hiatus, the Governor proposes extending implementation of the plan through 2020‑21.

Governor Proposes Mix of Spending and Policy Changes. Figure 7 shows proposed 2017‑18 funding changes. As described in more detail below, spending changes are primarily associated with implementing elements of the budget agreement and making caseload changes for CalWORKs and non‑CalWORKs child care programs. The budget plan also contains a notable federal fund swap. In addition to these changes, the Governor proposes several policy changes, primarily to give more flexibility to the state’s two preschool programs. These proposed policy changes have no associated spending changes.

Figure 7

2017‑18 Child Care and Preschool Changes

(In Millions)

|

Change |

Proposition 98 |

Non‑Proposition 98 |

Federal Funds |

Total |

|

Annualization of Changes Initiated in 2016‑17 |

||||

|

Annualizes Regional Market Rate increasea |

— |

$45 |

$12 |

$57 |

|

Annualizes State Preschool slot increase |

$24 |

— |

— |

24 |

|

Annualizes 5 percent license‑exempt rate increase |

— |

9 |

2 |

11 |

|

Subtotals |

($24) |

($54) |

($13) |

($91) |

|

Caseload Changes |

||||

|

Decreases non‑CalWORKs slots for statutory growth adjustmentb |

‑$4 |

‑$3 |

— |

‑$7 |

|

Makes CalWORKs caseload and average cost of care adjustments |

— |

61 |

‑$73 |

‑11 |

|

Subtotals |

(‑$4) |

($58) |

(‑$73) |

(‑$18) |

|

Other Adjustments |

||||

|

Adjusts Transitional Kindergarten for increases in LCFF |

$10 |

— |

— |

$10 |

|

Replaces state funds with federal funds |

— |

‑$93 |

$93 |

— |

|

Removes one‑time funding |

— |

‑1 |

‑6 |

‑7 |

|

Subtotals |

($10) |

(‑$95) |

($88) |

($3) |

|

Totals |

$30 |

$18 |

$28 |

$76 |

|

aIncludes a hold harmless provision so that no provider receives less than it received in 2015‑16. This provision will expire at the end of 2017‑18. bReflects 0.4 percent decrease in the birth‑through‑four population. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

||||

Spending Changes

Annualizes Funding for RMR Increases Initiated in 2016‑17. The 2016‑17 Budget Act initiated two voucher rate increases beginning January 1, 2017. Specifically, the budget increased the RMR to the 75th percentile of the 2014 survey—reflecting an average RMR increase of 5 percent over the former rates. The budget also increased the rate for license‑exempt providers from 65 percent to 70 percent of the RMR for family child care home providers. These rate increases affected providers participating in the Alternative Payment Program and all three CalWORKs child care stages. The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget includes $68 million to annualize these rate increases ($57 million for the RMR increase and $11 million for the license‑exempt rate increase).

Annualizes Funding for Full‑Day State Preschool Slots Initiated in 2016‑17. The 2016‑17 budget included $8 million for 2,959 full‑day State Preschool slots at local education agencies (LEAs)beginning April 1, 2017. The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget includes an additional $24 million for the full‑year cost of these slots.

Does Not Complete SRR Increase Initiated in 2016‑17. The 2016‑17 Budget Act included a 10 percent increase to the SRR that was scheduled to begin January 1, 2017. Because CDE has difficulty implementing a mid‑year SRR increase, CDE instead gave a 5 percent increase to all providers at the start of the fiscal year. The Governor’s budget does not provide funds to annualize the 10 percent increase—effectively maintaining the 5 percent increase implemented last year.

Makes Adjustments for Changes in CalWORKs Child Care Caseload and Average Cost of Care. The Governor’s budget includes a year‑to‑year decrease of $11 million to reflect changes in CalWORKs child care caseload and the types of care families select. (Changes in types of care used affect the average cost of care, independent from the rate increases described above.) This decrease is comprised of a $49 million decrease in Stage 1, offset by a $36 million increase in Stage 2 and a $2 million increase in Stage 3.

Applies Statutory Growth, but Not Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA), to Non‑CalWORKs Child Care Programs. The budget decreases non‑CalWORKs child care and preschool funding by $7 million to account for a 0.4 percent decrease in the birth‑through‑four population in California. The budget does not include a COLA (estimated to be 1.48 percent) for non‑CalWORKs child care and State Preschool programs. The Governor’s budget, however, does include a $10 million increase for Transitional Kindergarten associated with the Governor’s overall proposed augmentation for LCFF.

Swaps State With Federal Funds. The Governor’s budget allocates an additional $93 million in federal funds to offset state General Fund expenditures. This increase in available federal funds is the net result of a $120 million increase in federal TANF funds for the CalWORKs Stage 2 program offset by a $27 million reduction in available federal CCDF funds. The additional TANF funds are due to lower overall CalWORKs costs coupled with more realignment‑related funding for CalWORKs. Both factors work to free up TANF funds for CalWORKs Stage 2 costs.

Policy Changes

Allows More Flexibility for State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten Programs. The Governor’s budget includes four proposals to provide more flexibility for State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten providers. For State Preschool, the Governor proposes to: (1) exempt programs run by school districts from licensing requirements, (2) give all programs more flexibility in meeting minimum requirements for staffing ratios and teacher qualifications, and (3) allow part‑day programs to enroll children with special needs whose families do not meet income eligibility criteria (so long as all eligible and interested children are served first). For Transitional Kindergarten, the Governor proposes to allow school districts more flexibility in determining the number of hours they operate per day. We discuss these specific proposals in the next section.

Aligns the State Definition of Homelessness With the Federal Definition. Currently, children can be deemed eligible for subsidized care if they are homeless and a parent needs to access child care while looking for permanent housing. The state currently considers children to be homeless for the purposes of child care eligibility if they are sleeping in a shelter, transitional housing, or places not designed for use as sleeping accommodations. The Governor proposes to expand the state’s definition of homelessness so that it is the same as the definition used for the federal McKinney‑Vento Homeless Assistance Act. The definition used for federal purposes also classifies children as homeless if they are temporarily staying with other people due to the loss of housing. This slightly expanded definition of homelessness likely would increase the number of children eligible for child care. We have no concerns with this proposal.

Allows Providers to Accept Electronic Applications for Child Care. Currently, providers are required to collect paper applications with handwritten signatures from families applying for subsidized child care or State Preschool programs. The Governor proposes to allow providers to accept electronic applications and signatures from families applying for subsidized child care or State Preschool. We have no concerns with this proposal.

Analysis of Preschool Proposals

In this section, we provide an overview of California’s preschool programs, then discuss key issues relating to preschool slots and preschool program alignment.

Overview

State Has Two Main Preschool Programs. In 2016‑17, California spent $1.8 billion on two main preschool programs: State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten. Of this amount, $1.1 billion supported 164,000 State Preschool slots and $700 million supported nearly 80,000 Transitional Kindergarten slots. As Figure 8 shows, these programs have different eligibility criteria, program length, staffing requirements, and funding rates. Transitional Kindergarten is run exclusively by LEAs. By comparison, about half of State Preschool providers are LEAs (accounting for two‑thirds of slots) and half are non‑LEAs (accounting for one‑third of slots). In addition to these state programs, the federal government runs the Head Start preschool program. Of all subsidized preschool slots for four‑year olds in California in 2014‑15, 52 percent were in State Preschool, 31 percent in Transitional Kindergarten, and 18 percent in Head Start.

Figure 8

Comparing California’s Two Major Preschool Programs

|

State Preschool |

Transitional Kindergarten |

|

|

Eligibility criteria |

Four‑year olds from families with incomes at or below 70 percent of state median income as calculated in 2007.a Children in full‑day program must have parents working or in school. |

Four‑year olds with birthdays between September 2 and December 2.b |

|

Providers |

Local education agencies and subsidized centers. |

Local education agencies. |

|

Program length |

At least 3 hours per day, 175 days per year for part‑day program. At least 6.5 hours per day, 250 days per year for full‑day program. |

At least 3 hours per day, 180 days per year. |

|

Teacher qualifications |

Child Development Teacher Permit (24 units of ECE/CD plus 16 general education units).c |

Bachelor’s degree, Multiple Subject Teaching Credential, and a Child Development Teacher Permit or at least 24 units of ECE/CD or comparable experience.c,d |

|

Staffing ratios |

1:24 teacher‑to‑child ratio and 1:8 adult‑to‑child ratio. |

1:33 teacher‑to‑child ratio. |

|

Annual funding per childe |

$4,386 (part‑day) and $10,114 (full‑day). |

Average of $8,810. |

|

aPrograms may serve three‑year olds from income‑eligible families if all eligible and interested four‑year olds have been served first. bSchools may serve younger four‑year olds with birthdays before the end of the school year but those children do not generate state funding until they turn five. cReferenced permit and credential are issued by California’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing. dThe requirements shown apply to teachers hired after July 1, 2015. eFunding rates are 2016‑17 estimates. ECE/CD = Early Childhood Education/Child Development. |

||

State Authorized Districts to Create “Expanded” Transitional Kindergarten in 2015‑16. As part of the 2015‑16 budget plan, the Legislature enacted trailer legislation that allows school districts and charter schools to enroll four‑year old children in Transitional Kindergarten if their fifth birthday falls between December 2 and the end of the school year. These children generate attendance‑based funding when they turn five. A child with a birthday in the middle of January, for example, would generate funding for roughly half of the school year. The state does not collect data on the number of children enrolled as a result of these expanded Transitional Kindergarten provisions. Several large school districts, however, indicate they have expanded their Transitional Kindergarten programs under the new provisions. In 2015‑16, for example, the Los Angeles Unified School District indicated it served 2,900 children through the expanded Transitional Kindergarten provisions.

State Has Complicated Way of Funding Preschool Programs. For State Preschool, CDE contracts with individual providers using the SRR for every child served. The funding source is primarily Proposition 98 General Fund, though full‑day programs run by non‑LEAs receive non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for the wraparound portion of their program. The state funds Transitional Kindergarten through LCFF, which is funded with Proposition 98 General Fund and local property tax revenue.

Preschool Slots

Below, we provide background on recent increases in preschool slots, describe the Governor’s slot‑related proposals, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Added Total of Almost 10,000 Full‑Day State Preschool Slots Over Last Two Years. In 2015‑16, the Legislature added 7,030 full‑day State Preschool slots, scheduled to begin January 1, 2016. Of these slots, the budget act earmarked 5,830 for LEAs and 1,200 for non‑LEAs. In 2016‑17, the Legislature added another 2,959 full‑day State Preschool slots, all for LEAs, scheduled to begin April 1, 2017.

LEAs Have Not Shown Sufficient Interest in New Full‑Day Slots. To allocate new slots across the state, CDE requests applications from interested entities and awards contracts to those that demonstrate they can meet the minimum program requirements. In 2015‑16, due to a lack of applicants, CDE issued only 1,646 of the 5,830 full‑day State Preschool slots for LEAs. With the remaining funding, the department issued 3,700 part‑day slots for LEAs, 851 part‑day slots for non‑LEAs, and 1,490 full‑day slots for non‑LEAs (above the 1,200 already earmarked in the budget). In 2016‑17, LEAs to date have applied for only 519 of the 2,959 full‑day State Preschool slots available. The CDE is currently in the process of issuing a second request for applications. If CDE is still unable to find enough LEAs interested in offering the full‑day slots, it will make funding available for part‑day slots.

Some State Preschool Providers Report Challenges Earning Their Contracts. Each State Preschool provider contracts with the state for a specified amount of funding. If it does not spend its full contract amount, the associated funds return to the state. If this occurs for multiple years, CDE can reduce the contract in future years. In 2014‑15, the most recent year of data available, $101 million in State Preschool funding allocated to providers was “unearned.” This represents 12 percent of all State Preschool funding and is almost double the unearned rate for other contract‑based child care programs (7 percent). This amount also is 77 percent higher than the amount unearned for the program in 2013‑14. Several factors might contribute to the increased difficulty in filling slots, including: providers being unable to expand or open new sites quickly enough to accommodate the rapid and significant increase in slots since 2014‑15; increased enrollment in other large competing programs for four‑year olds, such as Transitional Kindergarten and Head Start; and the state’s outdated income eligibility threshold, which is based on state median income as calculated in 2007.

Multiyear Budget Agreement Assumes Total of Almost 9,000 Additional Slots Over Four‑Year Period. While not formalized in statute, the multiyear budget agreement for preschool included 8,877 additional full‑day State Preschool slots for LEAs. These slots were to be implemented in three equal batches on April 1 of 2017, 2018, and 2019. The first batch was funded through the 2016‑17 Budget Act, with future batches intended for inclusion in the 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 budgets respectively.

Governor’s Proposal

Does Not Include Funding for Additional Slots in 2017‑18. While the Governor’s budget includes funding to annualize the cost of the slots implemented mid‑year in 2016‑17, it does not include funding for the second batch of additional slots in 2017‑18. (These slots would cost $7.5 million under the rates proposed in the Governor’s budget.)

Allows Part‑Day State Preschool Programs More Flexibility to Serve Children With Special Needs. To allow providers more flexibility to serve as many children as their contract allows, the Governor proposes to allow part‑day State Preschool programs to serve children with special needs who do not meet the income‑eligibility criteria as long as all eligible and interested children are served first. (Current law allows part‑day State Preschool programs to fill up to 10 percent of their slots with children from families with incomes up to 15 percent over the income‑eligibility limit if all eligible and interested children are served first. Under the Governor’s proposal, over‑income children with special needs would not count toward this cap.)

Assessment

School Districts Do Not Have Strong Incentives to Apply for Full‑Day State Preschool Slots. The lack of interest among LEAs in new full‑day State Preschool slots may be due to their strong fiscal and programmatic incentives to serve children using expanded Transitional Kindergarten. Districts receive substantially more funding per day for Transitional Kindergarten than they receive for State Preschool. On a per‑day basis, Transitional Kindergarten funding is 21 percent higher than the average full‑day State Preschool rate and nearly twice the average part‑day State Preschool rate. Despite receiving higher levels of funding, Transitional Kindergarten programs operate for a shorter length of time and have fewer programmatic restrictions. They do not, for instance, have to determine income eligibility, conduct child assessments, or set up their classrooms according to specific state standards. Because of higher funding rates and fewer restrictions, we think many LEAs might be choosing to serve additional four‑year olds using expanded Transitional Kindergarten rather than through full‑day State Preschool.

Not All Eligible Children Are Being Served. Although some providers have difficulty earning their State Preschool contracts, we estimate a substantial portion of eligible children remain unserved. Specifically, we estimate that at least 1 in 5 income‑eligible four‑year olds in California are not receiving subsidized preschool through a state or federal preschool program. (If other similar programs are indicative, some families with eligible children might not be interested in participating in a preschool program, but other unserved families might desire it yet be unable to access it.)

Recommendations

Allow All Types of Providers to Apply for New Full‑Day Slots. If the Legislature is interested in supporting more full‑day State Preschool slots over the next few years, we recommend it make funds available to all providers, not only LEAs. LEAs currently do not seem to have sufficient interest in offering more full‑day slots and have strong fiscal incentives to serve children through expanded Transitional Kindergarten rather than State Preschool. If the Legislature wants more LEAs to operate State Preschool programs over the longer term, it could address funding disparities between State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten or change eligibility requirements so that each program serves a distinct group of students.

Focus on Unserved Eligible Children Before Expanding Eligibility. Given many children eligible for State Preschool currently are unserved, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to expand State Preschool eligibility to higher‑income children with special needs. Though the Governor’s proposal to serve more children with special needs seems well intended, it has the effect of displacing low‑income children who otherwise would be able to access the program. Moreover, LEAs are responsible for ensuring all four‑year old children with special needs receive service according to their individualized education program. As a result, this proposal effectively shuffles children with special needs from one program to another while bumping out low‑income children who have no other program option.

Preschool Program Alignment

Below, we provide additional background on State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten, describe the Governor’s proposals to better align the two programs, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten Have Different Health and Safety Requirements. State Preschool programs must be licensed and follow CCL health and safety standards. (The CCL is a division within DSS.) These licensing standards include requirements that classrooms be clean and sanitary, children be constantly supervised, teachers be trained in first aid, and medication and cleaning supplies be stored out of reach of children. Members of the public can submit complaints to CCL regarding possible licensing violations. The CCL is then required to visit the facility within 10 days. State Preschool programs also must follow standards set by CDE regarding classroom environment, which include a mix of health, safety, and programmatic requirements. These CDE rules include requirements that furniture and toys be clean and well‑maintained and classrooms be set up with multiple stations to support different types of learning (for example, classrooms could have a science area and an art area). Both CCL and CDE visit sites once every three years to monitor compliance with regulations. By contrast, Transitional Kindergarten programs are not licensed or inspected. Instead, they must operate in buildings with the same safety specifications as other K‑12 buildings. For example, these facilities must be built to minimize the risk of damage in an earthquake.

Many State Preschool Programs Participate in Local QRIS. The state provides $50 million for State Preschool QRIS each year, with funding allocated in 2016‑17 to 37 local consortia serving 49 counties. These consortia use the funds to evaluate the quality of State Preschool providers and offer additional resources to help providers improve or maintain program quality. Local consortia assess providers based on a five‑tier matrix, which awards points for different levels of staffing ratios and qualifications, the quality of child‑teacher interactions, and the implementation of certain child assessments, among other program aspects. The minimum State Preschool requirements are roughly equivalent to a Tier 3 rating.

Schools Required to Operate Transitional Kindergarten Same Length of Day as Kindergarten. Under state law, Transitional Kindergarten is the first year of a two‑year Kindergarten program. If a school district runs Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten programs on the same site, the two programs at that site must be run for the same length of the day. Districts that want to operate a full‑day Kindergarten and a part‑day Transitional Kindergarten program on the same site must obtain a waiver from the State Board of Education. (Districts can operate programs of differing lengths on separate school sites.)

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Interested in Better Aligning State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten. The Governor’s budget includes several proposals to more closely align these two programs. Most of the proposals are designed to make State Preschool programs more similar to those of Transitional Kindergarten but one proposal is designed to make Transitional Kindergarten more similar to State Preschool.

Exempts State Preschool Programs Run by School Districts From Licensing Requirements. The Governor proposes to exempt State Preschool programs from CCL requirements if they operate in facilities constructed according to the state’s K‑12 building standards. Programs still would be required to follow CDE’s requirements for staffing and environment.

Includes Two Flexibility Proposals for Meeting State Preschool Staffing Requirements. The Governor proposes to exempt State Preschool providers with QRIS Tier 4 or higher ratings from the State Preschool staffing ratio requirements. These providers, however, still would need to meet licensing requirements (that is, have an adult‑to‑child ratio of 1:12). Similarly, for State Preschool programs with lower QRIS ratings or no rating, the Governor proposes to allow classrooms taught by a teacher with a Multiple Subject Teaching Credential to operate with an adult‑to‑child ratio of 1:12 (rather than the 1:8 ratio currently required).

Allows Districts to Run Part‑Day Transitional Kindergarten and Full‑Day Kindergarten on Same Site. The Governor proposes to allow school districts to run their Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten programs on the same site for different lengths of time without a waiver.

Assessment

Better Alignment of State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten Programs Worthy Goal. The state currently lacks a systematic approach to providing early learning to four‑year olds, which results in wide disparities in eligibility, funding, and the types of services provided. Given this lack of coherence and unnecessary complexity, we think better alignment of the state’s two largest preschool programs is a very worthy goal.

Proposals Make Complicated System More Complicated. Although the administration intends to better align State Preschool and Transitional Kindergarten, many elements of his proposals add greater complexity to the existing system. For example, exempting only certain State Preschool programs from licensing requirements would create different requirements for State Preschool programs at LEAs and non‑LEAs. Similarly, while State Preschools run by LEAs would be exempt from licensing requirements (and more similar to Transitional Kindergarten in that respect), they still would have to follow CDE’s regulations about classroom environment (which do not apply to Transitional Kindergarten). By creating new staffing ratio standards for State Preschool teachers with a teaching credential, the staffing flexibility proposals also add complexity without allowing for complete alignment. A State Preschool classroom with a credentialed teacher still would be required to have an adult‑to‑child ratio (1:12) almost three times lower than that of Transitional Kindergarten (1:33).

Additional Concerns With Minimum Staffing Requirement Proposals. In addition to our concerns about making the system more complicated, we also have specific concerns with the proposal to allow higher staffing ratios for credentialed teachers. Specifically, we are concerned that a teacher with a Multiple Subject Teaching credential and no early education training requirements might not be better prepared than a teacher with early education training to serve more children with less adult support.

Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten Funding Not Aligned With Program Length. Given the state currently allows school districts to choose the length of day for their Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten programs at different school sites, we see no reason to restrict their ability to offer programs of different length on the same school site. We are concerned, however, that Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten programs receive the same amount of funding per student regardless of program length. This lack of alignment results in a funding structure that has little connection to districts’ underlying program costs.

Recommendations

Reject Preschool Proposals, Pursue Alignment More Holistically. Rather than make marginal changes to existing preschool programs to get them to operate somewhat more similarly, we recommend the Legislature take a more holistic approach. Under such an approach, the Legislature would consider how best to serve four‑year olds, particularly those from low‑income families. To this end, it would consider what eligibility criteria, program standards, and funding levels it desired for these children. Making all these decisions in tandem would provide for better alignment and coherence.

Adopt Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten Flexibility in Tandem With Differential Rates. If the Legislature does not pursue holistic reform of programs serving four‑year olds, we recommend it adopt the Governor’s proposal regarding Transitional Kindergarten and Kindergarten flexibility and also establish differential funding rates for full‑day and part‑day programs. Such an approach would better align school district funding to actual program costs and reduce funding disparities between part‑day State Preschool and part‑day Transitional Kindergarten programs.

Quality Improvement Activities

In this section, we provide background on a federal requirement that states spend a certain amount each year on improving the quality of their child care and preschool programs. We then describe a recently revised quality expenditure plan submitted by CDE, provide an assessment of the state’s existing quality improvement programs as well as CDE’s expenditure plan, and make several associated recommendations.

Background

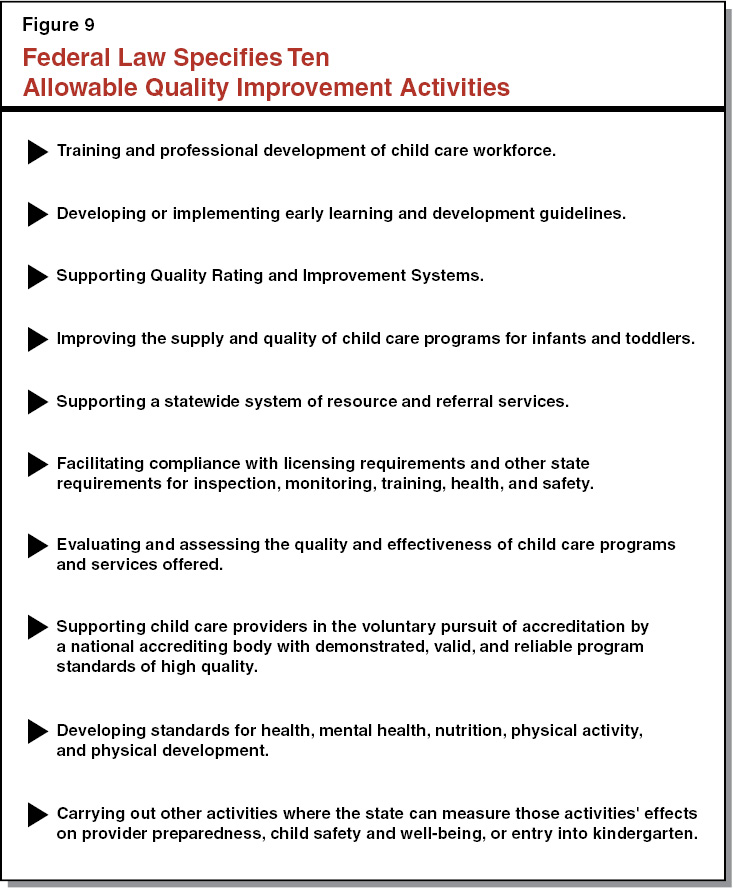

Federal Law Requires States to Spend a Certain Amount Each Year on Improving Quality of Child Care and Preschool. California receives roughly $600 million each year from the federal government through CCDF. As a condition of receiving the funds, the state is required to spend an additional $200 million each year in state funds to meet a matching requirement. Of this combined $800 million, the federal government requires the state to spend a certain percentage on quality improvement. In 2016‑17, the state was required to spend 10 percent ($78 million) on quality improvement activities, with 3 percent ($22 million) required for activities benefitting infants and toddlers and the remaining 7 percent ($56 million) not restricted to any particular age group. In addition, the state reappropriated $6 million in unspent prior‑year quality funds, bringing total quality spending to $84 million in 2016‑17. California is required to submit an associated expenditure plan to the federal government every three years. The state’s most recent plan was approved in June 2016 and extends through September 30, 2018.

Federal Requirement for Quality Spending Set to Increase Through 2020‑21. Due to a recent reauthorization of the federal act governing the CCDF, the federal requirement for quality improvement spending will increase gradually over the next few years, reaching 12 percent by 2020‑21. The percentage of funds for infant and toddler quality improvement activities will remain at 3 percent, with the percentage not restricted to any particular age group growing to 9 percent by the end of the period. Assuming federal CCDF funding remains flat, the state would be required to spend $95 million on quality improvement activities in 2020‑21.